Ora Smith's Blog, page 4

December 5, 2019

America 400

I learned something while writing my recent novel about John Lothropp. The Pilgrims who came to America in 1620 were Separatists, not Puritans. How many times have we seen paintings of the Pilgrims in Puritan clothing? When in reality they probably wore the colors of everyday-people in England. All over the internet you can find learned people calling the Pilgrims Puritans. I’m wondering if I was taught this in school. How did the false information get into my brain?

Here’s a brief description of both of these groups of people Separatist: English Protestants who denied the Church of England altogether. They separated themselves from the perceived corruption of the Church and formed their own congregations. They felt true Christian believers should seek out other Christians and together form churches that could determine their own affairs without having to submit to the judgment of any higher human authority. (In the early 1600s it would have been the king and his archbishops/clergy.) Some believed the Church failed to promote faith because of lascivious living and greed of the hierarchy. Because Separatist congregations were illegal in the early 17th Century, many of its adherents were persecuted by the High Commission. They were often labeled as traitors and many left England.

Here’s a brief description of both of these groups of people Separatist: English Protestants who denied the Church of England altogether. They separated themselves from the perceived corruption of the Church and formed their own congregations. They felt true Christian believers should seek out other Christians and together form churches that could determine their own affairs without having to submit to the judgment of any higher human authority. (In the early 1600s it would have been the king and his archbishops/clergy.) Some believed the Church failed to promote faith because of lascivious living and greed of the hierarchy. Because Separatist congregations were illegal in the early 17th Century, many of its adherents were persecuted by the High Commission. They were often labeled as traitors and many left England.Puritan:Held the belief that the Bible—and not traditions—should be the sole source of spiritual authority, holding that the pattern for organization of the church was laid down by the New Testament. They were also at the fore of the campaign for reform. The key ideas of the Reformation were a call to “purify” the Church of England from its Catholic practices—thus the believers called themselves “Puritans.” They insisted on significant changes in the Book of Common Prayer but were reasonably satisfied with the Church’s Calvinist teachings on predestination and the Eucharist as well as its hostility toward images. Although they didn’t leave the Church, they maintained that the Church of England was only partially reformed. They called for ethical and moral purity, believing true reformers should remain in the Church, working for this purification. They adopted a literal reading of the Sabbath commandment (Sabbatarianism) that called for both worship and rest on the seventh day of the week. They believed Paradise would occur on Earth prior to the final judgment (millennialism). Because their ministers made it their purpose to interpret scripture for the people, they became a central role in their society.The biggest difference between the Separatists (Pilgrims falling into this group) and the Puritans is that the Puritans believed they did not need to abandon the larger Church of England. Their culture of thrift and industry fostered prosperity for themselves and their community. Puritans were known to wear simple clothing that was black or dark brown. They felt it ungodly to laugh or have fun. Puritan’s preferred to call themselves "the godly." They developed a colony in America which they wanted to be a model to the world. In 1630 a famous Puritan, John Winthrop, wrote of settling the Massachusetts Bay Colony: “We shall be as a city upon a hill, the eyes of all people are upon us.”In 2020, America will be celebrating the 400th Anniversary of the arrival of the Pilgrims and formation of the Plymouth Colony.

In commemoration of the event, there will be many festivities in Massachusetts.

In commemoration of the event, there will be many festivities in Massachusetts.Visit the Plymouth 400 website to learn more about the many commemorations, including the Commemoration Opening Ceremony in Plymouth on April 24th; the Official Maritime Salute with regatta, lobster and military fanfare on June 27-28th; the August 1st Wampanoag Ancestors Walk; the Official Massachusetts State House Salute on September 14th; the Embarkation Festival on the 19-20th of September; the Indigenous History Conference and Powwow on October 29th; and finally, Illuminate Thanksgiving from November 20-25th.

Visit Plimoth Plantation Museumwhere they provide personal encounters with history and teach of the Mayflower’s arrival into Cape Cod.

To commemorate the 400th anniversary of the landing the Pilgrims Massachusetts Society of MayflowerDescendants will host a naturalization ceremony featuring Pilgrims escorting new citizens to their swearing-in ceremony! Because there were 102 passengers on the Mayflower, 102 Mayflower members in Pilgrim dress will walk arm in arm with 102 recent immigrants as they get ready to be sworn in as US citizens at a naturalization ceremony.

General Society of Mayflower Descendants events include the Mayflower II Anniversary Gala in Provincetown; a reenactment of the signing of the Mayflower Compact; a sure-to-be memorable Pilgrim Progress march through Boston, culminating in the official State House salute to the 400th anniversary; and the Mayflower Society’s 400th Anniversary Black Tie Gala, in addition to tours and other activities.

The New England HistoricGenealogical Society will commemorate the Mayflower’s 400th anniversary with Mayflower Heritage Tours—exclusive tours directed by NEHGS experts that explore the sites of the Mayflower's inception and journey. In June 2020 NEHGS will lead a tour to the United Kingdom for a visit to Plymouth, Southampton, and Dartmouth, England, with world-renowned NEHGS Great Migration scholar Robert Charles Anderson as our guide. The tour will focus on the events leading to the embarkation of the Mayflower in 1620—a journey that would change the world. “A New England Sojourn” in June 2020 and again in September 2020 will be two exclusive, three-day visits to historic sites in Massachusetts associated with the Pilgrims, including Plymouth, Provincetown, Duxbury, and elsewhere.

In England, the commemoration focuses on the key towns and cities that make up the national Mayflower trail. On the Mayflower 400 website you can explore the sites, attractions and places on the trail using maps and destination links.

Even in Holland you can take a walking tour that makes it easy to imagine how life was in the 17th century. Guidedvisits to the Leiden American Pilgrim Museum, the Pieterskerk and the University will allow you to understand why the pilgrims ended up in Leiden, and why it was such a dynamic place to be back then.

Published on December 05, 2019 14:45

April 1, 2019

April is National Poetry Month

Poetry scares me. When someone asks me to write a poem, my first thought is “I can’t do it,” and my mind closes down. Yet, I know if I were better at poetry, it would affect my writing style and storytelling. I desire to achieve lovely metaphors and thoughtful prose that make a reader stop in their tracks and savor the words.On the blog Stephanie Says So, one can learn a different style of poem writing every day for the month of April. Today, Stephanie posted instructions on how to write The 5 W’s Poem. I have followed her instruction and this is what I wrote:

Ancestors Helped form my identity With the way they lived their life When they had trials, made choices, allowed circumstance, finished achievements, and followed talents Because they too desired happiness and fought to survive

Published on April 01, 2019 18:56

March 3, 2019

Deuteronomy 32:7

Published on March 03, 2019 13:37

February 14, 2019

Using Ancestors’ Stories in Fiction

Just how far back into the past can you reach to find new ideas for writing? Family history (genealogy) is the second most popular hobby in America, making it easy to find information online. Have you ever considered using stories or unusual events that happened in your ancestors’ lives in your novel? As writers, we must always be willing to go looking for new and creative concepts. When writing fiction about ancestors, you can balance facts with imagination.

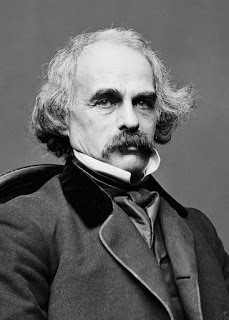

Just how far back into the past can you reach to find new ideas for writing? Family history (genealogy) is the second most popular hobby in America, making it easy to find information online. Have you ever considered using stories or unusual events that happened in your ancestors’ lives in your novel? As writers, we must always be willing to go looking for new and creative concepts. When writing fiction about ancestors, you can balance facts with imagination. Learning about your ancestors can be a treasure trove for character building, plotting, settings, and so much more. One of the most famous examples of an author using his ancestors in a novel would be Alex Haley when he wrote Roots. But did you know Nathaniel Hawthorne

loosely based The Scarlet Letter on his strict Puritan ancestors? Or that Emily Bronte in the gothic novel, Wuthering Heights, based the unusual and imbalanced character of Heathcliff from an ancestor?

loosely based The Scarlet Letter on his strict Puritan ancestors? Or that Emily Bronte in the gothic novel, Wuthering Heights, based the unusual and imbalanced character of Heathcliff from an ancestor? Our ancestors’ stories often hold potential for great plot lines. You don’t need to write their stories as historical fiction, but instead bring their experiences forward into contemporary times or even the future. It’s possible the struggles your ancestors experienced on the Oregon Trail or settling a new land may be the very same experiences a colony in space may come up against. If you’re an American, then its more than likely you have immigrant ancestors. Often their stories are full of learning, strife, hate, fear, and misunderstandings from both the country they left and the one they settled. Assimilation is usually not easy. Finding the motivation behind these issues might be where a story lies.

You can find ideas on how to create well-rounded and interesting characters from people in your family tree. Experiences, hardships, and relationships make us different from one another. Rarely are people all-good or all-evil. Create fully dimensional villains by thinking of the worst person in your family then round them out with at least one redeeming quality. People are always more complex than they seem, as your characters should be. From one of my ancestors I formed a character who steals from his mother, lies easily and without hesitation, has alcohol and drug abuse issues, and has spent time in prison for crimes you can’t speak of in polite society. Yet, he’s partially redeemed by his sensitivity and the memories of his family he holds close to his heart.

People’s life experiences shape them. Find out social, economic, religious, and political backgrounds. Did they grow up in a big family, or were they an only child? How high of an education did they receive and was it traditional? Were they illiterate? Did they love the earth and farm the land?

People’s life experiences shape them. Find out social, economic, religious, and political backgrounds. Did they grow up in a big family, or were they an only child? How high of an education did they receive and was it traditional? Were they illiterate? Did they love the earth and farm the land?

Did the family carry traits from their homeland brought to the country of immigration? Did their name spelling change? Did they have to learn a new language?

Did the family carry traits from their homeland brought to the country of immigration? Did their name spelling change? Did they have to learn a new language? Interviewing the oldest living relatives in your family is a good place to start. Ask what they remember about their parents and grandparents. Writing about family members means researching clues to figure out what kind of life they led, who they loved, how they loved, and what they did with their lives.

To find your ancestors, you could use family history websites such as ancestory.com, chroniclingamerica.com, cyndislist.com, and archives.com. Some of these websites can help you track down living descendants of your ancestor’s siblings. It’s a great way to find photos because people usually didn’t keep their own portraits, but gave them away to family members. A face is worth a thousand words—let your imagination go wild and write those thousand words from your ancestor’s likeness.

Old census records can be valuable information for how many were in a family and what their occupations were. And it’s amazing what can be found in a courthouse. They hold records of births, marriages, deaths, and so much more. Court records can help you find drama about relatives who were criminals, but also those who were victims. Land records could demonstrate an ancestor’s lifestyle and wealth. Perhaps they didn’t own land, but instead followed the migration to unchartered territories of the Wild West.

Researching and writing about your ancestors can help you come to respect them for who they were and the paths they chose. In knowing who your ancestors were and writing about them, you can help others by giving past experiences understanding. Transform them into characters that suit the needs of your story. You could even write yourself as a fictional character searching for his or her past and unlocking family secrets. Don’t forget to leave room for your imagination to take your readers to new and interesting places.

Published on February 14, 2019 11:03

February 2, 2019

Vote for Others to Win a Trip to Their Ancestral Homelands

On January 12 I posted "What Does Your Ancestral Homeland Mean to You?" and recently heard from a reader, Mira Daniels, who entered the RootsTech FilmFest '19 contest (that I had mentioned in the post). She is one of the semi-finalists! Here is a link if you want to see her video and vote to help her win a trip to her ancestral homeland. And here are all the videos if you'd like to vote for others. Good luck, Mira! Let me know if you win and I'll post it here.

On January 12 I posted "What Does Your Ancestral Homeland Mean to You?" and recently heard from a reader, Mira Daniels, who entered the RootsTech FilmFest '19 contest (that I had mentioned in the post). She is one of the semi-finalists! Here is a link if you want to see her video and vote to help her win a trip to her ancestral homeland. And here are all the videos if you'd like to vote for others. Good luck, Mira! Let me know if you win and I'll post it here.

Published on February 02, 2019 10:11

January 23, 2019

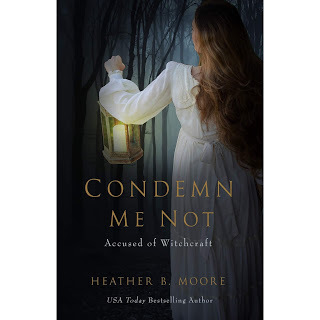

Interview with Heather B. Moore about her book "Condemn Me Not: Accused of Witchcraft"

Condemn Me Not:Accused of Witchcraft , is a fantastic book about the author’s ancestor.

Are you wondering what it would be like to write fiction about your ancestor? Heather B. Moore wrote about her ancestor in the book Condemn Me Not, largely about the Salem Witch Trials, but also detailing her ancestor’s early life when she met her husband.

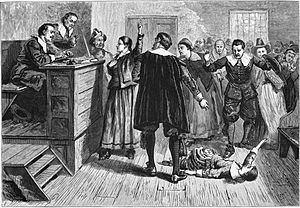

Ora: Heather, it’s so kind of you to do this interview! When reading your book, I was immediately appalled and fascinated as you described your 72-year-old, 10thgreat-grandmother, Susannah Nurse Martin, in a filthy prison awaiting trial for the infamous Salem Witch Trials. The year was 1692. I’m curious, did you feel any connection to her as you wrote? Did it feel any different than when you’ve written other stories not based on an ancestor?Heather: Thanks for the interview, Ora. Susannah is on my father’s side of the family, but my mother is who discovered the connection. When she first emailed me some information, I knew immediately that I wanted to write her story someday. That someday occurred several years later. I think feeling compelled to write her story was a connection that I couldn’t exactly explain. Her story is included in many historical texts, but I wanted to take a different approach.

Ora: Did you come at the story differently knowing you were writing about an ancestor and not a fictitious character?Heather: I’ve written a lot of historical novels, so this wasn’t different in that aspect. The difference was that I knew that many of my family members would likely be reading it, as a family history of sorts, so I wanted to make sure I did thorough research.

Ora: When you first found out you were a descendant of Susannah’s, how did you feel?Heather: I found out about 10 years ago, and started seriously thinking of when and how to write the book about 8 years ago. I was amazed and read through several things online that I could find.

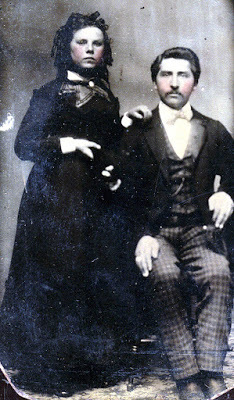

Ora: What was it like writing about the romance of your ancestors?Heather: Susannah was twenty-five when she married, which was considered a near-spinster. After reading through all that she and her husband had endured, and the many times he’d stood up for her, I knew there was a true love story in their relationship. Of course, I took some liberties with emotions and attractions, but I believe that I was at least basing them on emotions that transcend time for all of us.

Ora: Were you worried you wouldn’t get something right and displease Susannah or George Martin?Heather: There was enough conflicting information, that sometimes I had to take the best educated guess. I was also careful to include all of my sources at the end of the book. I’ve received an email or two from other descendants with corrections, and I’ve gone ahead and updated those files. The nice thing about historical “fiction” is that readers know there are some liberties taken, and I am sure that Susannah and George understand this as well.

Ora: Why did you write Susannah in first person?Heather: First person narrative is a very intimate point of view. I didn’t exactly “choose” to write in first person. The first paragraph came out that way. I wrote the first chapter about four years before I was able to continue in writing and research, so I stuck with my earliest impressions of how the story needed to be told. In the audio version, narrated by Nancy Peterson, I find that first person becomes a haunting and touching voice.

Ora: I enjoyed the structured of the story with going back and forth through time. Why did you write it this way?Heather: I decided to write the story as a dual timeline because I didn’t want to have to skip over years with each chapter as I wrote. I also didn’t want to regurgitate all of the books out there that focus on the trials. By writing Susannah as a younger woman, we get to see her early life, her romance, and delve into her community culture and norms. We learn about the foundation of the Salem and Salisbury community, so that when Susannah does meet her tragic end, we have a full view of this era in American history. The chapters of her as a young woman also give the reader a bit of relief from the chapters set in prison during her last few weeks of life.

Ora: What would you like to share about the research? How much research did you do? How long did it take?Heather: I dabbled on and off for about four years, and finally I decided to dedicate two months to research and writing. When I was finished, the book felt too short. So I added a couple of scenes “after” the marriage. Even when I’d finished it, I didn’t publish it for about another year. We also did a custom photo shoot with my daughter as the cover model.

Ora: That’s cool about your daughter being on the cover—one more connection to family. Was it hard to decide what to put in the story and what to leave out?Heather: I already knew that I didn’t want to focus on the trials and the accusers as much as other books had. It had already been done, and done well. So that gave me more focus on Susannah’s earlier life and her immediate family. And then I wanted to include the women she was hanged with. For the sake of the story, I have them all in the same jail cell, although they might not have been all together. That was another thing that was hard to discern through research. But they all received the same death sentence and were hanged at the same time and place.

Ora: What is your take on Puritans and the witch trials?Heather: There are plenty of theories as to the “why” that have been explored by other historians. I definitely believe in mass hysteria since I’ve seen it in my own community. Rumors lead to more rumors, and that only fuels the fear.

Ora: Have you written any other novels based on ancestors? Would you do it again?

Ora: Have you written any other novels based on ancestors? Would you do it again?Heather: I would be interested in doing it again if I found the right story that compelled me to invest the time needed. I’ve ghost-written the beginnings of other ancestor stories, but haven’t finished them because there was no contract offer.

Ora: Thank you for taking the time to share your thoughts with my readers and myself. Is there anything else you’d like to mention that may be helpful to someone who’s decided to write fiction about their ancestor?Heather: One piece of my advice from my mother is that she wanted me to “soften” some of the scenes I’d written, due to the advent of younger relatives reading my adult-audience books. I did soften a couple of the scenes. But those younger relatives eventually grow up, and I didn’t want to dilute the impact of the story. Another thing I did was a poll on the title of the book. I really struggled with what to call it, and finally landed on Condemn Me Not: Accused of Witchcraft, after reviewing several suggestions.

Ora: Not only is it a good title, it was a great book. Thanks so much for taking the time for this interview. Condemn Me Not is a valuable example of how to write fiction about ancestors.

Published on January 23, 2019 09:47

January 12, 2019

What Does Your Ancestral Homeland Mean to You?

If when you have your DNA tested for ethnicity and you find where your ancestors were from, does this make you want to travel there? Would you like to win a trip for two to your ancestral homeland? There’s a company called momondo (lowercase m) whose slogan is “Let’s Open Our World.” On their website it states: “momondo was founded on the belief that everybody should be able to travel the world. Travel opens our minds and the door to a world where our differences are a source of inspiration and development, not intolerance and prejudice.”

If when you have your DNA tested for ethnicity and you find where your ancestors were from, does this make you want to travel there? Would you like to win a trip for two to your ancestral homeland? There’s a company called momondo (lowercase m) whose slogan is “Let’s Open Our World.” On their website it states: “momondo was founded on the belief that everybody should be able to travel the world. Travel opens our minds and the door to a world where our differences are a source of inspiration and development, not intolerance and prejudice.” A couple of years ago, momondo recorded a serious of videos called, “The DNA Journey Feat.” It can be found on YouTube and is very entertaining to watch. I would suggest starting with the one about Ellaha from Iran and then the other videos in the segment should que up. There are a few that are short segments of some candidates in the study, but it is far more interesting to watch the full videos of each individual, such as the ones about Jay, Carlos, and Aurelie. Momondo tested 67 people, but there’s maybe only a dozen videos to be found on YouTube. With cameras capturing their every expression as they look at their DNA results for the first time, their initial reactions are fascinating to watch.

At the beginning of the study of these 67 young men and women of varying nationalities, they were one by one brought before a panel of two and asked questions like, “What ethnicity do you think your ancestors were,” or “How do you feel about taking a journey based on your DNA?”

It was interesting to hear the answers to who they thought they were ethnically. Most were sure of their ethnic heritage, but the DNA results told them differently. Many who stated what they hoped they were not, were actually from that ethnicity.

An Englishman who thought he was 100% English, said he didn't like the Germans due to the conflicts between the two countries and his ancestors serving and defending England. Through his DNA, he learned he was 5% German. Did the information soften his heart? His responsive expression seemed to say it did.

An Icelander said, “I am more important than a lot of people.” He said he was from the best country in the world and that he was stronger and better than any other ethnicity. When he opened his DNA results, he found his family was from Eastern Europe, Spain, Portugal, Italy, and Greece. He then said, “Iceland has definitely moved closer to Europe now.”

A French woman said all her ancestors were from France. When asked, “If you could be any other nationality, which would you pick?” She chose Italian and British. Her results showed she was in fact, 32% British and 31% Italian. No French ethnicity at all showed in her DNA. She said, “I’ve never really felt at home in my own country—in France.”

All candidates were asked if they wanted to travel to the places their ancestors were from, and they all answered in the affirmative.

The slogan of #letsopenourworld is: “An open world begins with an open mind.”

At the end of the study, a candidate commented (and I second the sentiment), “Who would be stupid enough to think there’s a pure race?”

Two years ago, I blogged about visiting my homeland in Ireland in a post called “Are Our Ancestors in Us?” I discussed that unusual phenomenon of feeling like you’ve come home when you travel in your ancestral homeland that you’ve never been to before. I’d like to update that post with an interesting piece of information. My initial ancestry.com autosomal DNA test stated that I was 7% Irish, which didn’t sit well with me. I “felt” more Irish. Well, as ancestry.com has accumulated a bigger database, their results have changed. I am recorded as 21% Irish and Scottish (the two are now grouped together). The results narrow it down further to pinpoint where in Ireland my ancestors were from, which is Southern Connemara and the Aran Islands of County Galway. A small area, maybe just 1/32nd of Ireland.

I wonder how much more our DNA will teach us in the coming years?

If you want to travel to learn about your ethnicity, you have the opportunity to win a trip for two to your ancestral homeland! RootsTech is looking for videos of people stating what connections with their ancestors mean the most to them. Your video will need a title and short description. Use your imagination—and good luck!

Published on January 12, 2019 17:36

Win a trip for two to your ancestral homeland!

RootTech is looking for videos of people stating what connections with their ancestors mean the most to them. Your video will need a title and short description. Use your imagination—and good luck!

Published on January 12, 2019 17:36

June 21, 2018

How Do We Know Our Ancestors Narratives are Accurate?

Can you trust your memories? Can you trust memories of family members who have left behind their stories?

I recently read the memoir, Educated, by Tara Westover. It was a grueling read and depressing to the end. I struggled through learning about Westover’s disturbing rural “survivalist” childhood of abuse and neglect. The stories were intense, emotional, and left me exhausted. But Westover’s alluring writing kept me reading. It was like staring at a bad car accident when you know you should look away. I will never forget the book yet can’t decide if I could recommend it to others.

Westover sometimes started a scene by explaining how she remembered the past, but then added that a sibling remembered it differently and told what those differences were. She would even occasionally ask herself if her memory was to be trusted, which then gave her the drive to find evidence of past experiences to back up her memories.

When I looked online at reviews and what people were saying about Educated, I realized the book has become controversial. Some of Westover’s siblings and family friends are claiming Educated to be all lies. Perhaps that is to be expected—and I am making no judgement here.

How do we deal with remembering the past differently than others who were part of that experience? If those others can’t accept our reality, they may try to change the past by denying it. As Westover put it, “reality becomes fluid.” Educated may be an extreme example, but most of us know memory can be fickle. In grad school, I learned that because memory is not reliable, you can only representan event. There are as many versions of an event as there are people who took part. We were also taught to approximate dialogue that we no longer remembered word for word.

Memories can be fragmentary and sometimes influenced by how we want things to have been. Mary Karr, the author of The Liar’s Club, said, “To minimize regrets and justify our behaviors, we sometimes convince ourselves of alternative explanations.”

But how else do we learn, but from our memories or the experiences of others? Even if our memories are not fully formed with all the facts, they often capture our motivations and desires. They may create an image that is consistent with what we felt an experience meant. There is much to be learned by examining our life. And when we write of emotional truth—no one else should argue.

There’s no need to analyze all writing coming from memory for accuracy, but it doesn’t hurt to understand how memory works. Stories are usually written in hindsight—understanding and reflecting on experiences. And there’s no question that by writing about our lives we become more aware and gain clarity and knowledge.

If we are writing about ancestors from stories that they handed down, how do we know their narratives are accurate? Is there a concern that we might be twisting the reality of the past? Like any good researcher, we need to look for the evidence. You may find that the dates don’t line up, or that the third-great-grandfather who didn’t believe in slavery did in fact own slaves. Interview relatives, read diaries, letters, documents, newspaper accounts, and check public records such as census, vital, court, taxes, municipal registry of deeds and land, or books on local history. If you can’t authenticate something, use attributions such as: I believe, or it stands to reason, or it’s possible that…

If we are writing about ancestors from stories that they handed down, how do we know their narratives are accurate? Is there a concern that we might be twisting the reality of the past? Like any good researcher, we need to look for the evidence. You may find that the dates don’t line up, or that the third-great-grandfather who didn’t believe in slavery did in fact own slaves. Interview relatives, read diaries, letters, documents, newspaper accounts, and check public records such as census, vital, court, taxes, municipal registry of deeds and land, or books on local history. If you can’t authenticate something, use attributions such as: I believe, or it stands to reason, or it’s possible that… My family holds hatred for a man who lived in the mid-1800s. It was said that he took land from my ancestor, a poor widow whose husband owed just one more mortgage payment when he died. Because the mortgage was not fully paid, the entire mortgage was forfeited and the house and land taken from the widow. When I did the research, I found there was no record of that “hated” gentleman ever owning the land to begin with.

Not everything is in a record. When oral history is passed down, details are lost or separate experiences are woven together. The telling may become distorted, amplified, and move further from the truth. Many have been guilty of romanticizing the past.

I’m convinced some of the best stories aren’t documented because they were meant to be kept secret. To tell a good story, we need the details that probably aren’t available. This is where the decision may be made to write the story as historical fiction rather than biography or creative nonfiction.

Nowadays we read memoirs of harsh realities and best sellers that often tell of dysfunctional families and squalid childhoods, but it wasn’t long ago that families kept these things secret at all costs. To keep quiet was a loyalty to the family or a way to keep the peace. Now it seems we are ready to arrive at a larger truth about families and all their defects. On social media many “tell all” and don’t seem to miss the loss of privacy. Even then, perhaps it’s not all truth.

Published on June 21, 2018 09:07

March 9, 2018

I guest posted on Almost An Author!

See my article: Using Ancestors’ Stories in Fiction

Almost An Author's mission is to provide quality instruction to help writers learn their craft and become published authors.

Published on March 09, 2018 11:58