Ora Smith's Blog, page 3

May 28, 2021

The Pulse of His Soul novel reviewed by the Historical Novel Society

The Historical Novel Society (HNS) is well known amongst historical fiction writers, but perhaps you’ve never heard of them. They are a great resource if you love historical fiction and want to read reviews for what’s out there before buying. I was recently blessed with a nice review from the HNS for my book The Pulse of His Soul.

St James Church in Egerton England

St James Church in Egerton EnglandReview by B. J. Sedlock

Genealogist Smith novelizes the life of John Lothropp, a Separatist minister who broke with the Anglican Church and became a forgotten Founding Father: he is the ancestor of six U.S. Presidents and dozens of major figures in American politics, religion, and the arts.

The novel covers Lothropp’s experiences in England before he emigrates. John is a perpetual curate in the Anglican Church when he marries Hannah Howse in 1610. Childhood trauma causes John to have trouble showing love, which creates conflict in their relationship. Hannah is a fervent Anglican, but John grows doubtful over the years that a church controlled by the government is the true path. John rebels against the king dictating what he can say in the pulpit, and in 1622 he renounces his Church of England’s orders, and they move the family to London. Hannah worries that Bishop Laud’s men will learn of John’s Separatist ways and imprison him; the congregation he now leads in Southwark must worship in each other’s homes and keep watch for Laud’s men. Eventually John is able to hide no longer, and he is caught, tortured and imprisoned, leaving Hannah with a large family of children to support.

Smith gives the reader a very impressive fifty-plus pages of supporting material, such as an extensive bibliography, a timeline, and a glossary. I applaud her scholarship; Lothropp deserves to be better known. Smith’s depiction of John and Hannah’s relationship is both contentious and touching. The religious content of the story is necessarily heavy. Even if theological discussions aren’t your cup of tea, Lothropp’s story will bring new insight to American readers who learned about the Pilgrims and Puritans in school but may not have really understood why they left England. Recommended to those interested in religious history, 17th– century England, and early American history.

March 5, 2021

Did Anyone Help You See Your Ancestors for Who They Were?

My grandmother, Marie Hardison Whitehurst, was not a typical grandma who baked cookies and pattered about. She didn’t even want to be called grandma. To us, she was Mimi. She kept a slim figure, wore fashionable clothes, and was a socialite who had memberships at San Diego and later San Francisco boating clubs. She attended community gatherings and went to fancy restaurants with her tall, handsome husband. She told me she couldn’t bear to not live near water after she’d spent her younger years along the Atlantic seaboard. Proud of attending college in the 1930s, she often spoke of her alma mater, the College of William and Mary in Virginia.

Mimi in her younger years, about 1927

Mimi in her younger years, about 1927Mimi bought herself a computer in the 1980s and was emailing before her grandchildren did, encouraging us to “get on” so she could send letters much faster and without stamps. She connected the extended family by telling us about each other. But mostly, she was a phenomenal storyteller, carrying the wisdom of generations.

I have many early memories of being nestled by her side, her arm around my shoulders while she talked on and on about those family members who went before me. I doubt many of her other eighteen grandchildren, or later fifty great-grandchildren, sat and listened for so long, but the colorful stories always kept me still. Through the years, the same stories were repeated, and I never tired of them. Perhaps they planted the seeds in me to become a writer.

Mimi helped me to see my ancestors as real people who lived full and important lives. When I visited at her home, she’d pull out heirlooms and tell me whatever stories she knew to go with them. She was a writer herself and left a legacy of poems, journals, and letters. I believe she kept every piece of family jewelry, furniture, household decor, photographs, and books she was ever given. In her later life, she gave the heirlooms as gifts to me and others who had an interest in family.

Her great-grandmother was Caroline, the woman my newest novel (to be released March 23!) is about. Mimi was ten when Caroline died, and Mimi too had sat at great-grandmother Caroline’s side listening to stories long past.

Mimi almost lived to her ninety-sixth birthday with her mind and memories intact. In the spring of 2009, she asked me to come visit, probably aware she was in her last weeks on earth. She wanted to go through heirlooms, mostly letters, and make sure I knew the stories. I wanted to do this too. It was a sad but special time to be alone with her.

She had me bring out the boxes under her bed that held love letters between her parents. The sweet words between them were genuine and heartwarming. There were also other letters in those boxes, sent between her siblings and cousins who lived across the American continent from one another. Even a letter from my great-great grandfather to his granddaughter Ora (my great-aunt) telling of the love of his life, our namesake, Ora Mattocks Hardison. My soon to be released novel, White Oak River, A Story of Slavery’s Secrets is the story of that first Ora’s parents. A love story too.

White Oak River: A Story of Slavery’s Secrets

After giving birth to a son with dominant African traits, a white Southern enslaver

must decide if she’ll hold onto her bigotry at the cost of her heart.

When Caroline Gibson marries the Reverend John Mattocks, she leaves behind her privileged life, which she finds easier than leaving behind her prejudices. While she’s content being served, John lives to serve others. Scorning his family’s wealth and long-held practice of owning slaves, he chooses to follow his conscience, becoming an abolitionist preacher. But after Caroline gives birth to a son of African heritage, they both must face their vastly different beliefs. Their marriage mirrors the Civil War’s failure to create a changed society, the turmoil not only leaving the nation in despair but their relationship as well. Can their love find deeper roots in forgiveness and acceptance?

This dramatic story of love, faith, family bonds, and discrimination is based on true events of the author’s great-great-great-grandparents in coastal North Carolina.

Prequel novella to White Oak River: A Story of Slavery’s Secrets

Will be offered on my website FREE for a limited time, starting March 23, 2021

White Oak Plantation: Slavery’s Deeper Roots

An enslaved young woman craves a family. Her mistress desires status in society.

Can an unlikely bond change their lives forever?

Most slaves long for freedom. Eighteen-year-old Spicey longs for a sister. As an orphaned house slave, she’s desperate to belong to a family—even her mistress Caroline’s family. But Caroline is more concerned with courting John, the local preacher, than noticing Spicey’s devotion or caring for her needs. Caroline doesn’t even think to look past Spicey’s skin color to see their relationship for what it is. But when the decision to protect a runaway slave causes them both to risk everything, will the chains of slavery keep them bound to a world of lies and prejudices or be the catalyst that sets them free?

November 11, 2020

What happened on November 11th 400 years ago?

After traveling on the Mayflower for 66 days, the Pilgrims arrived at Cape Cod on November 11, 1620—400 years ago today. A replica of the Mayflower (Mayflower II, a “living history” museum) was gifted to America by England in 1957, and recently went through renovations to be seaworthy, with hopes of it being part of the America 400 Celebration. As with many things this year, most of the celebrations did not and will not take place.

Mayflower II (replica)

The 102 passengers aboard the Mayflower hoped to start new lives in America. Not all of them were Separatists from the Church of England. Less than half didn’t come for religious purposes but hoped for land. There was also a full crew of sailors, some of whom had been to America and back on previous passages.

They encountered many fierce storms and a cracked main deck beam. During one bad storm, my husband’s ancestor, John Howland, was tossed overboard. Miraculously he was able to grab a topsail halyard (long rope) which happened to have broken loose and shouldn’t have been near him in the water. Sailors were able to pull him aboard by the halyard. Howland felt it a miracle.

A small merchant vessel, the Mayflower was 100 feet long with three masts and six sails. The passengers spent most of their time belowdecks where it was cramped, many fell sick, it smelled foul, and animals were kept in pens. One child was born during the crossing.

The Mayflower was supposed to land near the Hudson River, 200 miles south of Cape Cod, but storms and treacherously shallow waters kept it from doing so. I can only imagine how relieved they were to finally site land and drop anchor. In William Bradford’s words: “…they fell on their knees, and blessed the God of Heaven, who had brought them over the vast and furious ocean and delivered them from all the perils and miseries thereof.”

A month later, on December 11, the Pilgrims landed a shallop at the place they would call Plymouth. By the following spring, half of the colonists and sailors had perished. In October 1621, 53 Pilgrims and 90 Native Americans celebrated their abundant harvest by feasting for three days, now known as the First Thanksgiving.

First Thanksgiving

To discover more about the Mayflower II three year restoration, go to MayflowerSails2020.

September 8, 2020

Who is John Lothropp?

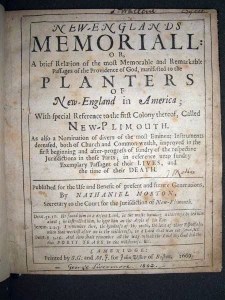

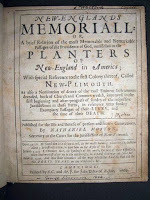

In the New England Memorial by Nathaniel Morton (1669), John Lothropp was considered to be one of the five most important ministers to arrive in New England during the Great Migration.

New England Memorial

Five United States presidents, as well as Princess Diana, descend from John Lothropp. So does a signer of the Declaration of Independence, also Oliver Wendell Holmes, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, John Pierpont Morgan, Lewis Comfort Tiffany, Walt Disney, Joseph Smith and dozens of other famous individuals who helped shape the country.

Thirty years ago, my father-in-law introduced me to his eighth great-grandfather, Reverend John Lothropp, through a booklet published by the Institute of Family Research called John Lathrop 1584-1653: Reformer, Sufferer, Pilgrim, Man of God (1979). Interested in history, genealogy, and religion, I was captivated by this courageous reformer with such immense zeal and humility. I was also curious as to why a man would risk so much for the right to pray and worship the way his conscience dictated, so similar to the plight of the American Pilgrims and other religious martyrs and reformers.

Against the backdrop of the seventeenth century Church of England’s religious suppression, my novel, The Pulse of His Soul: The Story of John Lothropp, a Forgotten Forefather, begins shortly after Reverend Lothropp takes his orders to become a perpetual curate in Egerton, England in 1610. I felt it was here we needed to start his journey and understand his character in order to follow him through his change of heart and separation from the Church of England to join with the Independent Church in London.

St James in Egerton

Hannah Howse—his wife and the daughter of a vicar—was a strong and loving woman who did not make the same choices as her husband. Because of this, the religious conflict and fervor of the kingdom entered their home, even though both believed in a powerful and individual relationship with God that could be mastered through faith and unification. The Pulse of His Soul unfolds through the eyes of both Reverend Lothropp and his wife. His personal decision to renounce his orders affected his whole family when he fell out of favor with the Church and lost his social standing.

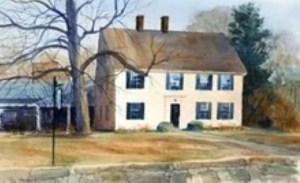

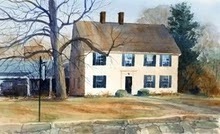

When the Reverend John Lothropp came as an exile to America in 1634, he settled with his congregants in Scituate, but by 1639 he founded Barnstable, Massachusetts, a coastal town on Cape Cod. Here he became known as the minister of the Congregational Church. (It survives in customs and worship to this day, now known as West Parish Church.) And just as his congregation had done in London, they covenanted together “to walk in all God’s ways as He had revealed or should make known to them.” The town prospered under the spiritual guidance of Lothropp and for seventy-eight years it was the only church in Barnstable. The home he constructed in 1644 still partially stands and is the original part of the Sturgis Library, which is the oldest Library building in the United States.

Lothropp home, now Sturgis Library

To learn more about John Lothropp

Check out The John Lothropp Foundation and also read about John Lothropp on Wikipedia, where it states: “Perhaps Lothropp’s principal claim to fame is that he was a strong proponent of the idea of the Separation of Church and State (also called “Freedom of Religion”). This idea was considered heretical in England during his time, but eventually became the mainstream view of people in the United States of America, because of the efforts of John Lothropp and others.”

September 7, 2020

It’s Been Exactly 400 Years Since the First American Pilgrims left England

Today, September 6th, is the anniversary of the Pilgrims leaving England in the Mayflower. Since July 1620 they had been trying to sail to America, but their second ship, the Speedwell, kept taking on water, sending them back to shore. Finally leaving in September, it would be another two months before they’d land on the shores of a new land at Plymouth Colony, and not at the area they’d intending on living.

Mayflower

Through research, I learned something new about the Pilgrims while writing my novel The Pulse of His Soul about Reverend John Lothropp, a man who was a Separatist and a contemporary of the Pilgrims. Most of those people who came to America in 1620 were Separatists, not Puritans. How many times have we seen paintings of the Pilgrims in Puritan clothing? When in reality they probably wore the colors of everyday people in England. All over the internet you can find learned people calling the Pilgrims Puritans. I’m wondering if I was taught this in school. How did the false information get into my brain?

Here’s a brief description of both groups of people

Separatist:

English Protestants who denied the Church of England altogether. They separated themselves from the perceived corruption of the Church and formed their own congregations. They felt true Christian believers should seek out other Christians and together form churches that could determine their own affairs without having to submit to the judgment of any higher human authority. (In the early 1600s it would have been the king and his archbishops/clergy.) Some believed the Church failed to promote faith because of lascivious living and greed of the hierarchy. Because Separatist congregations were illegal in the early 17th century, many of its adherents were persecuted by the High Commission Court. They were often labeled as traitors and many left England.

Puritan:

Held the belief that the Bible—and not traditions—should be the sole source of spiritual authority, holding that the pattern for organization of the church was laid down by the New Testament. They were also at the fore of the campaign for reform. The key ideas of the Reformation were a call to “purify” the Church of England from its Catholic practices—thus the believers called themselves “Puritans.” They insisted on significant changes in the Book of Common Prayer but were reasonably satisfied with the Church’s Calvinist teachings on predestination and the Eucharist as well as its hostility toward images. Although they didn’t leave the Church, they maintained that the Church of England was only partially reformed. They called for ethical and moral purity, believing true reformers should remain in the Church, working for this purification. They adopted a literal reading of the Sabbath commandment (Sabbatarianism) that called for both worship and rest on the seventh day of the week. They believed Paradise would occur on Earth prior to the final judgment (millennialism). Because their ministers made it their purpose to interpret scripture for the people, they became a central role in their society.

Pilgrims arrive at Plymouth

The biggest difference between the Separatists (Pilgrims falling into this group) and the Puritans is that the Puritans believed they did not need to abandon the larger Church of England. Their culture of thrift and industry fostered prosperity for themselves and their community. Puritans were known to wear simple clothing that was black or dark brown. They felt it ungodly to laugh or have fun. Puritan’s preferred to call themselves “the godly.” They developed a colony in America after the Separatist Pilgrims which they wanted to be a model to the world. In 1630 a famous Puritan, John Winthrop, wrote of settling the Massachusetts Bay Colony: “We shall be as a city upon a hill, the eyes of all people are upon us.”

In 2020, America had plans to celebrate the 400th Anniversary of the arrival of the Pilgrims and formation of the Plymouth Colony, but the coronavirus pandemic caused cancellations of all festivities.

Still, in commemoration of the Pilgrim’s landing in America 400 years ago, there will be some online events. The Plymouth 400 committee renewed their commitment to mark the 400th anniversary with new event plans and ongoing legacy projects. One will be the Illuminate Thanksgiving 2020, November 20-25. They will hold the annual tradition as a virtual event with the US, Netherlands, UK, and Wampanoag tribes.

In England, the commemoration focuses on the key towns and cities that make up the national Mayflower trail. On the Mayflower 400 website you can explore the sites, attractions and places on the trail using maps and destination links.

In Holland you can take a walking tour that makes it easy to imagine how life was in the 17th century. Guided visits to the Leiden American Pilgrim Museum, the Pieterskerk and the University will allow you to understand why the pilgrims ended up in Leiden, and why it was such a dynamic place to be back then.

The Plimouth Plantation Museum has posted on their online calendar that the Mayflower replica can be toured by ticket holders only, and they will be having “feasts” in November. I assume plans will be changed as necessary.

September 4, 2020

Have You Considered Learning About History Through Your Ancestors?

Using the medium of a novel, I’ve written stories of my ancestors based on true events, hoping to share their interesting lives with others. I’m calling my stories Heritage Fiction.

In my blog and newsletter, I’ll share published books in which Heritage Fiction is present. I’ll post interviews with authors and also book reviews. Check in often to find out what’s being discussed.

Here are some books you may have read or want to read that are based on the author’s ancestor in either a small or large way:

Where the Lost Wander by Amy Harmon

These Is My Words by Nancy E. Turner

Hotel on the Corner of Bitter and Sweet by Jamie Ford

Cold Sassy Tree by Olive Ann Burns

Sarah, Plain and Tall by Patricia MacLachlan

Galway Bay by Mary Pat Kelly

Hattie Big Sky by Kirby Larson

Condemn Me Not: Accused of Witchcraft by Heather B. Moore

A Pawn for a King by Sarah Hinze

Daughter of Anne-Hoeck by Carol Pratt Bradley

Cane River by Lalita Tademy

The Hummingbird’s Daughter by Luis Alberto Urrea

The Last Kingdom by Bernard Cornwell

The Glass-Blowers by Daphne du Maurier

East of Eden by John Steinbeck

To Kill a Mockingbird by Harper Lee

Little Women by Louisa May Alcott

David Copperfield by Charles Dickens

The Scarlet Letter by Nathaniel Hawthorne

The House of the Seven Gables by Nathaniel Hawthorne

Roots by Alex Haley

Wuthering Heights by Emily Brontë

On Gold Mountain by Lisa See

I think there are likely more qualities of living that we’ve inherited from our ancestors than we realize—some tangible and some intangible. Customs are not only passed on, but perhaps artistic expressions, talents, values, objects, places, and practices.

Why did these cultural heritage aspects prevail in your family to be carried to you?

Most likely they are tied to taught value systems, beliefs, aesthetic interpretations, environment (both natural and architectural), lifestyles, artifacts (heirlooms, pictures, documents), and traditions.

Learning about history isn’t in everyone’s wheel of interest, but have you considered learning about history through your ancestors?

I hold to a belief that if we learn from the past, we can make our future better.

The Heritage Cycle diagram below gives an idea of how we can make the past part of our future.

By understanding, people will value it. By valuing, people will want to care for it. By caring, it will help people enjoy it. From enjoying, comes a thirst to understand (and the cycle continues).

Making a Change

I’ve had a blog on blogspot for five years, but it wasn’t receiving much traffic, so I decided to switch my blog to www.orasmith.com. Come back often for Heritage Fiction chats, book reviews, author interviews, discussing topics like family identity, epigenetics, visits to ancestral villages, and just about anything related to family and history or family history (as in genealogy).

May 20, 2020

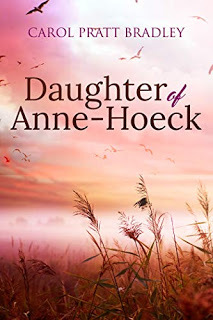

Interview with Carol Pratt Bradley about her historical novel "Daughter of Anne-Hoeck"

About six years ago, I went to a writing retreat in a small town near Park City, Utah. I met Carol Bradley, whom I learned was interested in writing historical fiction about an ancestor of hers. Of course, she had my full attention since this is my “thing.” Carol told me she descended from Susanna, the daughter of Anne Hutchinson, and was hoping to write a novel about Susanna’s experiences of being captured by Indians and then returned to the Puritans six years later. I told her I had plans to write about John Lothropp, someone in the same time period. Neither of us were published authors yet. In February 2020, Carol released

Daughter of Anne-Hoeck

, the novel about Susanna Hutchinson. Also in February 2020, I finished my manuscript about John Lothropp. Happily, Carol published three books before Susanna’s story. But it’s Susanna’s story that I’ve interviewed Carol about here. INTERVIEW

About six years ago, I went to a writing retreat in a small town near Park City, Utah. I met Carol Bradley, whom I learned was interested in writing historical fiction about an ancestor of hers. Of course, she had my full attention since this is my “thing.” Carol told me she descended from Susanna, the daughter of Anne Hutchinson, and was hoping to write a novel about Susanna’s experiences of being captured by Indians and then returned to the Puritans six years later. I told her I had plans to write about John Lothropp, someone in the same time period. Neither of us were published authors yet. In February 2020, Carol released

Daughter of Anne-Hoeck

, the novel about Susanna Hutchinson. Also in February 2020, I finished my manuscript about John Lothropp. Happily, Carol published three books before Susanna’s story. But it’s Susanna’s story that I’ve interviewed Carol about here. INTERVIEW

Hi Carol! Thanks for letting me interview you. Not only is Daughter of Anne-Hoeck an interesting piece of American history, it is also a great book. I was touched by your captivating writing and beautiful prose. A: Thank you, Ora! I’m so glad you liked the book.

Hi Carol! Thanks for letting me interview you. Not only is Daughter of Anne-Hoeck an interesting piece of American history, it is also a great book. I was touched by your captivating writing and beautiful prose. A: Thank you, Ora! I’m so glad you liked the book. Q: I’m curious, did you feel any connection to Susanna as you wrote about her? A: I did feel a connection but I’m not sure I have words to express it.

Q: I found Susanna to be a courageous survivor. When you first found out you were a descendant of hers, how did you feel? A: I thought I was familiar with my family history but I did not learn that I descended from Anne Hutchinson and her daughter Susanna until I ran across it on an internet search while doing research for my book about Anne Askew during my MFA. I contacted one of my sisters and she told me that we descend from that line through my father. I wondered why my aunt, the main family genealogist, had never mentioned it. I looked up Anne Hutchinson. When I mentioned it to my son, he said: “We come from all kinds of renegades, don’t we?” I guess we do. Our genealogical lines are full of people who left their homelands to begin again in undeveloped country. My life is different because of the choices they made long ago: where I was born, what religion I claim as my own. I wonder if I would make the same choices they did, show the same courage, if I shared their circumstances? Did some of their courage pass to me? I’m not sure. I have the same responsibility as they did to decide what legacy I want to leave behind for my descendants.

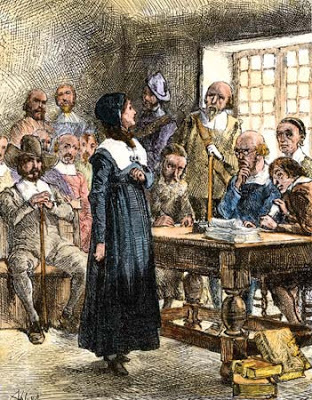

ANNE AND SUSANNA HUTCHINSONQ: Knowing you were writing about an ancestor, did you come at this story differently than your historical novels about the Biblical Daniel and the story of Anne Ayscough (Askew)? A: I don’t think I did. In the end, whatever story we choose to write, we must bring the same amount of empathy and connection to the characters. They all feel real to me, even the ones I made up. When I finally finish a book and see it sitting on my shelf, I feel joy and satisfaction, but I also mourn a bit that my time with that story is over. I miss the people I spent so much time with as I imagined their stories.

ANNE AND SUSANNA HUTCHINSONQ: Knowing you were writing about an ancestor, did you come at this story differently than your historical novels about the Biblical Daniel and the story of Anne Ayscough (Askew)? A: I don’t think I did. In the end, whatever story we choose to write, we must bring the same amount of empathy and connection to the characters. They all feel real to me, even the ones I made up. When I finally finish a book and see it sitting on my shelf, I feel joy and satisfaction, but I also mourn a bit that my time with that story is over. I miss the people I spent so much time with as I imagined their stories. Q: Do you know if Susanna was treated well by the Indians as you suggested in the novel? A: I found nothing in the records about Susanna’s time with the Indians. In his journal, John Winthrop recorded that Susanna had forgotten her native language and come away reluctantly from the Indians. Because of his prejudice toward the Hutchinson’s, I didn’t trust his slant on her story. I searched other accounts of capture, such as Mary Jemison, whose own account of her life was recorded by a minister and published in 1824. In my novel, Susanna’s experience with the Indians is my own interpretation.

Q: Why did you write Susanna in first person? A: When I first started writing, I wrote in third person, like I’d done with my other three books. Since I was writing about the things of the past, it felt more natural to write in past tense and third person. About five chapters in to this manuscript, though, I felt that I wasn’t fully connecting with the story or with Susanna’s voice. I went back and switched to first person and it felt right.

Q: I enjoyed the cadence of Susanna’s speech, which to me sounded authentic to a girl having lived in an Indian village for six years, and also her confusion and thought processes while trying to make sense of how the Indians taught her how to view the world through the metaphorical aspects of nature, whereas the harsh Puritans expected conformity to rigid views. Was it hard to write? A: Susanna’s voice was so difficult! I felt this novel needed to be written in first person, something I hadn’t done before. I nearly gave up on the novel because I couldn’t figure out a huge problem: Susanna supposedly lost her ability to speak English. This raised a huge question: How long would it take for a girl who lived with the Indians from the age of 9 until about 15 to regain her native language of English? How much would she have understood right after she returned? I set the manuscript aside for a couple of years, thinking I would not be able to write the story. But it would not leave me alone. Later, a search led me to language experts who said that children regain their native language very quickly. I figured that her comprehension of English would come much faster than reading and writing. It was a joy to write the sections where her niece taught Susanna her letters using a hornbook. I also felt that Susanna would not have lost the Lenape language. I found a Lenape website that I used for the Indian words.

Q: What would you like to share about the research? How much research did you do? How long did it take? A: I’m not sure how long it took for the research. I worked on the book off and on for seven years before it was published. I did a ton of research. I poured over books and articles about the time period, read John Winthrop’s journal, books on Anne Hutchinson, and the transcript of her trial in Boston. “American Jezebel,” by Eve LaPlante, another descendant of Anne Hutchinson, was particularly helpful. I studied the practice of midwifery.

ANNE HUTCHINSON I poured over photos of the places on the internet. A first draft was completed when my husband and I traveled to Boston and Rhode Island, retracing the family’s steps. That brought the Hutchinson’s story to life for me. I saw how narrow the streets were in Boston, how close John Winthrop’s house would have been to the Hutchinson’s. I could see the spot in Rhode Island where William Hutchinson built his house, between the Cove and the ocean. I saw the wildflowers growing along the banks and the curve of the sky above the water.

ANNE HUTCHINSON I poured over photos of the places on the internet. A first draft was completed when my husband and I traveled to Boston and Rhode Island, retracing the family’s steps. That brought the Hutchinson’s story to life for me. I saw how narrow the streets were in Boston, how close John Winthrop’s house would have been to the Hutchinson’s. I could see the spot in Rhode Island where William Hutchinson built his house, between the Cove and the ocean. I saw the wildflowers growing along the banks and the curve of the sky above the water. My research also led me to other people in the Boston area, who became characters in the book, such as the midwife Alice Tilley, whose own history is fascinating in itself. Since Alice was a friend and colleague of Anne’s, it seemed natural to me that she would be the person who taught Susanna to be a midwife. (It was a supposition on my part that Susanna would choose midwifery. Her mother and grandmother were both midwives, and bore many children, as Susanna did). It was a necessary but risky thing to be a midwife. If she offended the authorities or others, she could be accused of practicing witchcraft.

During Anne Hutchinson’s trial for heresy, insinuations were made that she could be a witch but it did not carry through. A few midwives were hung on Boston Common. During my research of Boston, I also discovered the missionary John Eliot, who translated the Bible into Algonquian and established Praying towns for Indians who converted to Christianity. Those praying towns were set strategically in a semi-circle around Boston, between the English settlers and the Indian tribes.

A warning about doing research: you can search and keep finding and never learn everything about a time and place. If you aren’t careful, you will never stop and write the story. I did a lot of research, and then began writing. But the research did not end there. As I wrote the story, I discovered many other things that I needed to know, so it grew into a combined process: write, research, write, research, write. That method works best for me.

Q: Was there anything you left out of the story because of word count constrictions or for some other reason? A: No. In fact, my editor sent back instructions to add more scenes and characters and add at least ten thousand more words. It was so much fun to write more!

Q: What is your take on Puritans and the Anne Hutchinson trials? A: I must admit that my opinion of the founders of the Boston area diminished. Men like John Winthrop and Thomas Dudley and the preacher John Cotton were no longer giants among men but human like everyone else, with weaknesses as well as strengths. Massachusetts was not tolerant of people who thought differently from the founders. It troubled me that the people who fled from England so they could believe according to their own consciences became like the very oppressors they had escaped from. Human nature is a complicated and troubling thing to me. As I read these men’s words and studied their actions, it seemed they acted often out of pride and the belief that their own beliefs and opinions were the only truth. Humans are certainly like that now. We haven’t changed at all. The founders of Boston did not approve of those who expressed their own beliefs publicly. People like Anne Hutchinson. I was outraged to read that the colony’s leaders disenfranchised any men who sided with Anne during the controversy, took away their weapons so they could not defend themselves if there were an Indian attack or such. That seemed like an egregious overreach of governmental power. Another example. When the Quakers came from England, they were not welcome in Boston. Mary Dyer, a close friend of Anne’s, converted to Quakerism. When she returned a third time to Boston, she was hung. Because she had a different religious belief. John Winthrop was dogged in his persecution of Anne Hutchinson. She was a strong-willed, charismatic woman, fearless, a threat to his authority. Even more infuriating, she was a woman. He called her a Jezebel and continued to try to hound her into submission even after she was driven from Massachusetts. When she was murdered by Indians in 1643, he rejoiced that the work of God was done to punish the wicked. I was gratified when I read an account that just before Winthrop’s death in 1649, Thomas Dudley came to him with yet another order to expel someone from the colony. Winthrop refused, saying that he had done too much of that work already. Did he come to regret his actions toward Anne Hutchinson? I hope he did. Another interesting character was the preacher John Cotton. He had known Anne Hutchinson in England, brought her in to his select group of parishioners, his “lilies among thorns.” Together, Anne worked to help Cotton nourish his parishioners. When Cotton was ousted from England, Anne and her family followed him to the new world. Many of Anne’s beliefs about God’s grace, etc. came from John Cotton. During Anne’s trial, Cotton was asked to speak. When he shrewdly noted that public opinion was solidly against her, he switched sides and condemned her. His betrayal must have been keenly felt by Anne. Was Anne outspoken? Yes. Was she wrong in her beliefs? I don’t think so. Was she wrong to express what she felt? No. In the minds of those who presided over her trial, she threatened their authority by daring to declare that the Holy Spirit had spoken directly to her. In the beliefs of that time, a person could only have access to God’s grace through a designated preacher. Her beliefs were declared to be heresy. They made her a public example, excommunicating her from the church and expelling her from the colony. The ironic thing was that by bringing her to trial, all of her words were recorded and preserved for future generations. If they had not, she might have disappeared from history. Instead, she is considered an icon of religious freedom. It is interesting to note that the freedoms upon which this country is built are not based on the government established in Massachusetts colony but on the charter of Rhode Island, where the Hutchinson’s and others founded a government where there was no established state church.

Q: If you could talk to Susanna face to face, what would you say? A: I’d want to thank her for her courage and the legacy of strength that she left for descendants like me. I’d like to ask her if I got her story right, but that would be too scary so I wouldn’t do it. I would ask her how her life really was, take out pencil and paper and write down all she said.

Q: Have you written any other novels based on ancestors? Would you do it again? A: I have not. I’ve mapped out a few. The story of Anne Hutchinson’s parents in England intrigues me. Maybe someday I’ll write it.

Q: Is there anything else you’d like to mention that might be helpful to someone who’s decided to write fiction about their ancestor? A: Even though Susanna’s time and experiences were different than the time I live in, I learned much about how to approach my own challenges. No matter what time period we live in, we all have much in common. An author must remember that within every time period people differ widely in their beliefs. We should not write from the narrow assumption that everyone who lived in the past is lumped into the same narrow space that we read about in history books written centuries later. Just like the present, there is so much variety in belief and lifestyle! I find that comforting. Strive to write the ancestor’s story within the historical context they lived in, remembering it is so much more than that. Write of their individual experience, of their own world within the bigger world of history.

Thank you, Carol, for taking the time to share your thoughts with my readers and myself. Daughter of Anne-Hoeck is a fantastic example of how to write fiction about ancestors.

To learn more about Carol Pratt Bradley's historical novel Daughter of Anne-Hoeck and other books, visit her website.

April 20, 2020

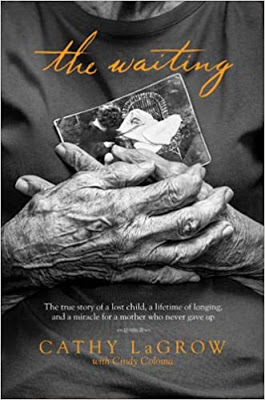

The Waiting: The True Story of a Lost Child, a Lifetime of Longing, and a Miracle for a Mother who Never Gave Up

I thought I’d share my thoughts on the book, The Waiting, that was published in 2014 because it’s a great example of how a family member can share a grandmother’s story. Professionally written and published by Tyndale House Publishers, the granddaughter, Cathy LaGrow, was co-authored by Cindy Coloma.

LaGrow tells in the back pages of the book how she researched and interviewed people. She lived in a different state than her grandmother and exchanged dozens of pages of Q&As and spent hours on audio interviews with her. She fact-checked her grandmother’s answers and found that her grandmother had an amazing memory for details.

The book begins with the story of her grandmother, Minka, as a child in South Dakota in 1928. At age sixteen, a very naive Minka was raped in the woods and became pregnant. (This part of the story was handled with great care, by the way.) Giving away her baby, the bulk of the book is about Minka’s yearning for her lost child and how she eventually raised a family, but never forgot her first daughter. Because Minka lives into her 90s, the story follows the Great Depression, WWII, and then the rapidly growing and changing America. The drama of true life carries the story forward and is always interesting.

For the book to read more as a story, LaGrow says she re-created conversations by making sure the characters conveyed only things that were factual and she kept the dialogue true to the personalities and views of the people conversing. “Wherever we attributed feelings, thoughts, or words to a person long deceased . . . we did so after carefully reviewing their letters and talking to Grandma,” LaGrow writes. Minka and family members read all the chapters for accuracy before publication.

Sometimes our family members’ life stories are worth writing about because they are dramatic, unbelievable, heartwarming, and many other powerful narrative considerations, but that could also mean that some family members wish to keep them private. LaGrow was careful to get everyone’s permission before sharing their part of the story. She not only made sure they were comfortable with what was said, but also that all details were accurate.

March 16, 2020

Who is John Lothropp?

In the New England Memorial by Nathaniel Morton (1669), John Lothropp was considered to be one of the five most important ministers to arrive in New England during the Great Migration.

Five United States presidents, as well as Princess Diana, descend from John Lothropp. So does a signer of the Declaration of Independence, Oliver Wendell Holmes, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, John Pierpont Morgan, Lewis Comfort Tiffany, Walt Disney, Joseph Smith and dozens of other famous individuals who helped shape the country.

Five United States presidents, as well as Princess Diana, descend from John Lothropp. So does a signer of the Declaration of Independence, Oliver Wendell Holmes, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, John Pierpont Morgan, Lewis Comfort Tiffany, Walt Disney, Joseph Smith and dozens of other famous individuals who helped shape the country.Thirty years ago, my father-in-law introduced me to his 8thgreat-grandfather, Reverend John Lothropp, through a booklet published by the Institute of Family Research called John Lathrop 1584-1653: Reformer, Sufferer, Pilgrim, Man of God (1979). Interested in history, genealogy, and religion, I was captivated by this courageous reformer with such immense zeal and humility. I was also curious as to why a man would risk so much for the right to pray and worship the way his conscience dictated, so similar to the plight of the American Pilgrims.

Against the backdrop of the 17th century Church of England’s religious suppression, my novel, The Pulse of His Soul: The Story of John Lothropp, a Forgotten Forefather, begins shortly after Reverend Lothropp takes his orders to become a perpetual curate in Egerton, England in 1610. I felt it was here we needed to start his journey and understand his character in order to follow him through his change of heart and separation from the Church of England to join with the Independent Church in London. Hannah Howse—his wife and the daughter of a vicar—was a strong and loving woman who did not make the same choices as her husband. Because of this, the religious conflict and fervor of the kingdom entered their home, even though both believed in a powerful and individual relationship with God that could be mastered through faith and unification. The Pulse of His Soul unfolds through the eyes of both Reverend Lothropp and his wife. His personal decision to renounce his orders affected his whole family when he fell out of favor with the Church and lost his social standing.

Saint James Church in Egerton, England

Saint James Church in Egerton, EnglandThe turbulence of living under King James forced John to fight for his deep-seated principles, his family, his life, and the truth of his convictions in a world filled with hypocrisy, tyranny, and betrayal. John was tortured and imprisoned, and then lost his home and country.

When the Reverend John Lothropp came as an exile to America in 1634, he settled with thirty-two of his congregants in Scituate, but by 1639 he founded Barnstable, Massachusetts, a coastal town on Cape Cod. Here he became known as the minister of the Congregational Church. (It survives in customs and worship to this day, now known as West Parish Church). And just as his congregation had done in London, they covenanted together “to walk in all God’s ways as He had revealed or should make known to them.” They believed that each church was to control its own affairs. The town prospered under the spiritual guidance of Lothropp and for seventy-eight years it was the only church in Barnstable.

Amos Otis was a historian who lived in Barnstable a hundred years after John. He studied the lives of Reverend Lothropp and his contemporaries. Otis wrote, “Mr. Lothrop was as distinguished for his worldly wisdom as for his piety. He was a good businessman, and so were all his sons. Where every one of the family pitched his tent, that spot became the center of business, and land in its vicinity appreciated in value. It is men that make a place, and to Mr. Lothrop in early times, Barnstable was more indebted than to any other family.”

John Lothropp home, now Sturgis Library

John Lothropp home, now Sturgis LibraryReverend Lothropp’s will left real property in Barnstable and money valued at 72 pounds 16 shillings and 5 pence. But that was not the true inheritance John left behind. He was a man who lived hardships most could not fathom. He journeyed through doubt, disbelief, impoverishment, death of his most beloved, torture, imprisonment, losing his home and country, and still through it all grew a testimony of Christ that could not be shaken. In America he found a place to rest and keep his commitment to walk in all of God’s ways.

Following are quotes extolling the Reverend John Lothropp:“He was a man of a humble and broke heart and spirit, lively in dispensation of the Word of God, studious of peace, furnished with godly contentment, willing to spend and be spent for the cause of the Church of Christ.” Nathaniel Morton, 1669.

He is described in Governor John Winthrop's journal as “rejoicing in having found for himself and his followers a church without a Bishop... and a state without a King.”

“[Lothropp] was an independent thinker. He received no doctrines on the faith of others, he examined for himself, decided for himself. Though bold and decided in his denunciations of the arbitrary acts of the bishops, he was as meek as the lamb in reproving the faults of his brethren, and the children of his church. Creeds and confessions of faith he rejected. The Bible was his creed . . . Whatever exceptions we may make to Mr. Lothrop’s theological opinions, all must admit that he was a good and true man, an independent thinker, and a man who held opinions in advance of his times.” Otis, Amos, historian.

“…he was endowed with a competent measure of gifts and earnestly endowed with a great measure of brokenness of heart and humility of spirit.” Walter R. Goehring, historian.

“Mr. Lathrop was a man of deep piety, great zeal and large ability.” Charles Henry Pope

“A man of a tender heart and a humble and meek spirit.” Burrage Champlin

possibly Lothropp or his son, John Lathrop At present, I’m shopping my manuscript to agents, and I plan to announce the release date here and on my website. I believe I descend from Hannah Lothropp’s brother, Samuel Howse, and hope to make that connection before the book’s release. My husband is the 9th great-grandson of Reverend Lothropp. If you’re a history buff, you might recognize some other characters in the novel, such as Samuel Hinckley, Nathaniel Tilden, and Robert Linnell. I also share how the Pilgrims played into Reverend Lothropp’s life. This may interest those celebrating the 400th anniversary of the Pilgrims’ arrival in America this year.

possibly Lothropp or his son, John Lathrop At present, I’m shopping my manuscript to agents, and I plan to announce the release date here and on my website. I believe I descend from Hannah Lothropp’s brother, Samuel Howse, and hope to make that connection before the book’s release. My husband is the 9th great-grandson of Reverend Lothropp. If you’re a history buff, you might recognize some other characters in the novel, such as Samuel Hinckley, Nathaniel Tilden, and Robert Linnell. I also share how the Pilgrims played into Reverend Lothropp’s life. This may interest those celebrating the 400th anniversary of the Pilgrims’ arrival in America this year.To learn more about John LothroppCheck out The John Lothropp Foundation (some of the website is under construction at present) and also read about John Lothropp on Wikipedia, where it states: “Perhaps Lothropp's principal claim to fame is that he was a strong proponent of the idea of the Separation of Church and State (also called "Freedom of Religion"). This idea was considered heretical in England during his time, but eventually became the mainstream view of people in the United States of America, because of the efforts of John Lothropp and others.”