Tade Oyebode's Blog, page 3

April 2, 2022

Aye Daye Oyinbo By Isaac Delano

These days, some in my network love to argue that Christianity is the cause of all our problems in Nigeria. They want us to return back to our manner of connecting with God before Christianity. It is a fact that Christianity came with colonization to South West of Nigeria.

I am not a fan of colonialism because it is a system of domination that took our resources and treated us as inferiors in our own land. We have to be honest that our custom and way of life were not perfect before colonization. You can catch glimpse of what things used to by examining cultural artefacts. In my opinion, books written by those who had (or had access to those who had) first hand experience of what things were before colonisation are also a form of cultural artefacts.

I chose to translate “Aye Daye Oyinbo” as “Our World Has Changed Because of Colonialism”. There could be other variations but they won’t be radically different. The book lifted the curtain (at least from the perspective of the narrator) on how the way of life, manners and customs of the Yorubas changed due to the influence of colonialism. The focus of this article is the family life in a polygamous household and the plight of women.

Colonialism changed everything: governance, relationships between husband and wife, authority of kings over subjects, the status quo, how labour was organized, check and balances in society, worship and religion, and of course, the notion of freedom. Some of the changes were good others not so good.

The author of the book was Isaac Delano. There is a wiki providing a brief autobiography of his life: https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Isaac_Delano. A quote from his wiki caught my eye:

“As a political/social activist, he attempted to explain African societies and the position of women, destroying stereotypes of female submissiveness in Yoruba culture and instead advocated that women were respected equals in Yoruba society and government. He also brought attention to female Yoruba heroes like Moremi Ajasoro.”

As I will show later, regardless of Delano’s political/social activism, Aye Daye Oyinbo painted a completely different picture of the experiences of a Yoruba woman before colonialism arrived to what that paragraph implies.

The author was born in 1904. Delano classified the book as fiction, but we should never forget that many fictions are rooted in reality. I think he was writing about the experiences of somebody in the generation of his own grand parents , probably his grandmother, somebody who saw the change unfold in real time.

Chapter 1 is captioned “Ile Olobinrin Pupo” ( “In A Polygamous House”). Before colonialism, the Yorubas were generally polygamous. What does polygamy offer a woman and the offspring of a polygamous marriage? Isaac Delano’s account in Aye Daye Oyinbo was from a woman’s perspective, we can gain some insight.

The first sentence in the book looked back to the good old days when life was good and peaceful, food was available in abundance and “olukulu ngbe nipa titobi re” (translated “each person lived according to how large, big or great their power, authority, strength, ability or force was”).

Just in case you are not sure what that sentence meant, the narrator used the next sentence to illustrate. She said the powerful can cheat their less powerful neighbour without being challenged by anybody. In the third sentence, the narrator made sure we had no doubt about what she meant by telling us that a lucky person born into a honorable, wealthy, dignified or respectable family can enjoy life. Obviously, at the expense of the unlucky born into penury.

The narrator was born into wealth and respect: her father was the war chief for their town, he would return from war with slaves, some of whom he sold, others he killed and others he married. The impunity with which the powerful lived was laid bare and stark.

The picture of what Yorubaland was in her days was very Darwinian: the fittest, wealthiest and most powerful rule the roost.

The narrator then moved on to describe her mother, who appeared to be a woman of substance. She had her own business, a seller of valuable beads. She contrasted her mother with others in society, specifically “eru” (slaves) and “iwofa”. Iwofa was a person pawned in place of a debt. Just as today people who are short of cash can take their valuables and pawn them for a loan, in those days, a man could pawn his son until he was able to replay his debt. An Iwofa will continue to serve his master until the obligation is settled. People’s poverty exploited to perpetuate their lives in debt.

The narrator moved on to describe one of the banes of polygamous families: favoritism. The narrator’s father preferred her mother to the rest of the wives and therefore, he treated her and her children better than the rest and that led to discord (in the author’s words, rebellion, riot and fights).

When the author’s sister died, her father and mother were inconsolable and believed the other wives were responsible. Obviously, this increased enmity and distrust within that family.

How the narrator’s mother greeted her father was an eye opener. She knelt down. That is still how children greet their parents in Yoruba culture. Clearly, the status of the wife was not the same as that of the husband.

When the narrator described a typical evening among the Yorubas then, she again gave us a graphic illustration of the plights of women in her days. In those days, pounded yam was the typical meal in the evening (most likely pounded by the women). Just before you decide to start eating pounded yam every evening, note that the children go out to play after their meal; they don’t sit down like couch potatoes watching TV; they played in the moonlight and their play was varied and involved a lot of physical movement. The children had fun but what about the women? The narrator wrote:

“À fi àwon ìyá wa, lí àìjé eléhàá, lí àìjé erú ni kò jáde sí gbangba lálé. Isé ni wón se…Ìpín obìinrin lí ojó wonni kò dára tó rárá”.

Translation

“Despite the fact that our mothers were not slaves and were not in purdah, they didn’t come out at night because they were busy working. The lots (portion) of women was not good enough in those days”.

The narrator then went on to describe how her mother prepared her for marriage. This included how to look after her husband, her mother in law, the rest of the in-law: clearly it was the husband’s world!

Finally, she returned to the intense rivalry among all the wives, despite eating together and drinking together. She concluded that if she were a man, she would not marry more than one wife.

In conclusion, the first few pages of Aye Daye Oyinbo laid bare the plight of women before colonialism from the viewpoint of a woman who grew up in a polygamous family. It is hard to argue that women were treated as equals of men. First a man was allowed to marry several wives. They knelt down to greet their husbands and apparently, they worked all evening and a child of such a marriage concluded that the lines did not fall to women in a good place.

I personally believe that without colonization, the dynamics of the relationship between men and women would have nevertheless changed with time. Having said that, colonization accelerated the process of change because Christianity was part of the package.

I don’t want to go back to colonialism. Neither do I want to go back to how my great grandfather lived before then. Instead, We should learn what we can from our past and use that to inform how we organize our society for the future.

March 26, 2022

Magic/Magical Realism and/or Miracles?

Magic/Magical Realism (henceforth referred to as Magic Realism in this post) is considered to be a subset of literary fiction genre and is ludicrously credited to a 20th century German. It is defined as “what happens when a highly detailed realistic setting is invaded by something too strange to believe” (see source).

I wanted to write about Magic Realism in the African setting but opted first to look for definitions. I was puzzled that the provenance of Magic Realism was traced to Germany in the 1920s. I can accept that Europeans did not know Magic Realism existed before their contact with Africans. However, the moment that contact happened, they would have encountered Magic Realism. Germany itself had its share of African territory in East Africa and South West Africa (see source). It is more likely that what was claimed as the origin of Magic Realism in Germany was inspired by encounters with the African culture. Although I will use Magic Realism narratives in South West of Nigeria as the base for this article, my guess is parallels can be seen elsewhere on the continent.

Among the Yorubas and other people groups in Nigeria and the rest of Africa, Magic Realism is not just a literary genre. Instead, it is at the heart of day to day reality. Football matches, winning elections, gaining political power, overcoming sickness, becoming successful in life, conception and successful delivery, etc., are often framed in what would be considered to be Magic Realism. That thing that “is too strange to believe” by Europeans and those whose ontologies are very Western, is entrenched in our belief system. As these things are embedded in the belief system and part of narratives that are believed by the people everyday, it naturally flows into our poetry, fictions, films and theatre. Every foreign religion that landed in South West of Nigeria has had its reckoning with the local Magic Realism narratives. Out of the encounter comes something that is neither completely foreign nor local.

Before and until the age of nine, I read several novels written in Yoruba language. Most of those books were deeply immersed in Magic Realism. First and foremost are the books of D.O. Fagunwa (MBE). Ogboju Ode Ninu Igbo Irunmole, translated into English language by Wole Soyinka, the Nobel Laurate (get a copy here) is probably the most popular. As early as the third page of this book, we come across that example of a “highly detailed realistic setting” being “invaded by something too strange to believe”. In the account that started on the third page, a hunter went on a hunting trip. Eventually, he became tired and rested. After a while, he saw the ground literally open and smokes started coming out until the fog of the smokes became so thick and dark he no longer could see. As the hunter tried to escape, the smoke became a man bearing a big sword, trying to kill him. As he begged for his life, the sword bearer said he wanted to kill the man because he was married to a wicked witch. His life was spared but only on a promise that he would kill his wife as soon he gets home.

After the incident, the hunter headed back home. His route took him through his okra farm and he heard some footsteps, therefore, he climbed a tree to see the intruder. The culprit went into a secluded place, but out came a deer, which straightaway started helping itself to the crops. Angrily, the hunter loaded his gun and aimed a shot at the deer. To his surprise, the deer wept bitterly and exclaimed in Yoruba: mo gbe o! (I am finished!). The hunter then retired to a little hut on his farm to pass the night.

At daybreak, the hunter went to investigate what happened to the deer but there was nothing but blood. He then traced the blood until it led to the room of his wife in his own house. Opening the door, the hunter found a creature that was from head to shoulder his wife but the rest of her body was that of a deer! All these within the first five pages of the book. Fagunwa went ahead to write a few more books where everyday reality was invaded by the magical.

Fagunwa set the pace but several others followed. Amo Tutuola with his book the “Palm Wine Drinkard” did the same but he wrote in English Language. Tutuola’s book was about the search for his dead palm wine tapper, a trip that was full of the invasion of highly realistic settings by events too strange to believe. Another author who wrote in Yoruba was J.O Ogundele. Ibu Olokun (The Deeps Of Olokun) was the story of a man called Orogodoganyin (I won’t even dare translate that!) who was whisked way by iji (storm, tornado, hurricane) and was not seen again for seven years. When he eventually turned up, Orogodoganyin came with abundance of supernatural power. In, “Ejigbede Lona Isalu Orun” (Ejigbede On the Way To Heaven), Ogundele told the story of a man who literally walked to heaven.

“Eegun Alare” by Lawuyi Oguniran which I reviewed here tells the story of masquerade magicians who went around performing to entertain people and can turn into animals and turn back to humans. “Won Ro Pe Were Ni” (they thought she was mad) by Adebayo Faleti (reviewed here) told the story of a man who tried to offer his best friend’s daughter for a sacrifice that will restore his wealth, but the girl got lucky and escaped.

Magic Realism has crept into every sphere of life in the South West of Nigeria and it is more than fiction. Magic Realism is almost part of our reality. Our ontology, our metaphysics accommodates the magical and this is often abused. Take Christian doctrines preached in South Western Nigeria versus similar Churches in England or America. American will preach “deliverance” just as the British churches do. When these doctrines are preached in South Western Nigeria, there will be another edge to it. In South West of Nigeria, you would hear “testimonies” of people who would claim they used to be the second in command to Satan himself and knew the devil personally. How many second in command does Satan have? Lol! Some pastors will preach about how they prayed for somebody who spew out a live snake (but there will not be any documentary evidence). These Magic Realism narratives can be exploited by some wicked leaders to get away with murder.

When you watch those viral clips where spiritual leaders command their followers to eat grass or to do something stupid, the reason the followers consent is simply because of their belief in Magic Realism. In their minds, their spiritual leader is very powerful and speaks to God face to face. Therefore, if he commands them to eat grass in order to magically manufacture their breakthrough, so be it. And those ritualists who kill their relatives, friends, strangers or what have you in order to have magical wealth are acting out the extremes of the believes in Magic Realism.

The bible teaches about the miraculous but the miraculous has blended into Magic Realism and commercialized. “Freely you have received; freely give” (Matthew 10:5-8) is how the miraculous is dispensed in the bible. With Magic Realism, people are made to part with their money in exchange for the promise of a miracle. Magic Realism narratives about the miraculous things that the spiritual leader did for others are used to prepare the people for the extraction of their resources. Some of these leaders promise financial miracles but their own finances are sorted by extracting money from their followers.

And you don’t even have to go to a religious setting like a church to encounter Magic Realism. I once read an article in a Nigerian newspaper about a witch who was “flying” back as a bird from a coven meeting and fell on a bus: Fake news. There was a famous academic in Nigeria who died suddenly decades ago. A man claimed that early death was because of an academic covenant: death at an early age in exchange for a meteoric academic career, this is nothing but pure conjecture!

As enjoyable as Magic Realism is as fiction, when it becomes part of our reality, it is dangerous and deadly.

February 26, 2022

Adiitu Olodumare by D.O Fagunwa (MBE): Figures of Speech in Yoruba Language

Adiitu Olodumare (Mystery of God) was probably the last book written by DO Fagunwa. It was published in 1961, just two years before his tragic death, in Bida, Niger State.

In this post, I want to focus on how Fagunwa, an accomplished master of the language used figures of speech in the very first paragraph of Adiitu Olodumare. I set out to do a review, but that will have to wait. Elsewhere, I wrote about the unusual length of paragraphs in Fagunwa’s books (read here).

In the first paragraph of Adiitu Olodumare, Fagunwa described a journey he took on a day when it rained heavily. To describe how heavy the rain was, he wrote “…se ni ojo nlu ilu le wa lo ri” (the rain was so heavy it was as if it was drumming on our car). This is the deployment of personification. Anybody who has ever experience a heavy rain in the South West of Nigeria will know precisely what he meant here.

In the same sentence, Fagunwa continued “…o n dun winniwinni bi omele ilu dundun” (the rain sounded like a particular Yoruba drum). If you have ever heard the sound of this drum, this simile will help you to paint a graphic picture of the event. Immediately after this, Fagunwa wrote: “bi a gbo gbururururu lapa otun, igbati o ba se, a gbo gbururururu lapa osi”. Here, he was describing the sound of the heavy rain using how it sounded, this is onomatopoeia. Another pair of onomatopoeia followed immediately (giriririri).

The next sentence used simile to compare the colour of the sky to a deep blue dye (o dudu bi aro). This was followed by “afi bi igbati Olodumare se iyefun fadaka, ti o nda sile lati oju orun”. Translated, this means it was as if God was pouring down silver dust from heaven. This for me is a metaphor, though I am not very sure, whatever the case, it is beautiful use of language. Another personification immediately followed when Fagunwa said the wiper wiping rain water off the windscreen became exhausted and gave up.

Fagunwa used hyperbole to give his readers a sense of the quantity of rain water on the road by saying that a boat can easily sail on the road due to the rain.

These many figures of speech in a passage that I estimated to have just 121 words and there are a few others that I left out. This is the beauty of the Yoruba language illustrated by the thoughts of an accomplished expert like Fagunwa.

it is up to the Yorubas to ensure this language doesn’t die. Sadly, we seem to prefer English to it.

February 12, 2022

A Righteous Man Regardeth the Life of His Beast (Or The Things People Share on Social Media)

I find it inexplicable that a footballer felt that the abuse suffered by the family pet was something that should be recorded on video and shared. What an awful video! When I heard about this, a verse of the bible came to my mind:

A righteous man regardeth the life of his beast: but the tender mercies of the wicked are cruel. Prov 12:10

The beasts that the bible refers to here are not even pets, rather, animals raised for consumption or for sale. Yet, the righteous man still regards the life of those animals and treats them well. I think the people responsible for this act require psychiatric and psychological help. Why should it be fun to kick a small animal like a cat for fun? This is very disturbing. To make matters worse, a child witnessed the event. Who knows the conclusion it reached? Did the child now think “beating up a cat is fun” or was he traumatized about the senseless infliction of pain on a defenseless animal? I shudder at the implication any of these two have on the child’s moral and mental development.

This is not about being “woke”. I take my moral compass from the bible.

Some do not understand why such razor like focus on treatment of one cat should take so much of the airwaves, especially around the same time that a famous footballer publicly admitted to wearing metallic stud to the pitch to hurt one of the defenders in the other team. He didn’t stop at that but went on to tell us that the player he wanted to hurt left the pitch on crutches. To those people I will say two wrongs don’t make a right. Both acts should be condemned and punished according to existing law (please don’t make up new laws on the hoof for this and apply retrospectively).

The purpose of my comments is not about this animal abuse: enough has been said about that one already. Just as these footballers thought abusing a cat is funny to them, I have often found myself scratching my head when I receive some posts on WhatsApp wondering why somebody should considered those contents funny or worthy of sharing with others.

At the beginning of this month, we read about a WhatsApp group within the Metropolitan Police where people shared sexist, racist and homophobic messages, with “highly offensive language”. It is not enough for people to hold sexist, racist and homophobic views on their own, there seems to be the need to gather together with likeminded to talk about it. Ironically, there probably were people in those groups who deplored the bigotry but lacked courage to speak out because they wanted to fit in. If you belong to a group where people objectify women and exchange sexist, racist and homophobic content (whether borderline or full blown), you should consider leaving. Otherwise, when justice comes, you may find yourself paying along with other members.

These policemen had one identity within their Whatsapp group, a completely different identity outside it. In their WhatsApp group they do hate in words. Outside it, they are supposed to upload the law. Won’t that WhatsApp identity influence their conduct in the real world?

Humans are social animals: we want to share. When I see something funny on TV, I often pause it, call my wife to come and watch if she is free and nearby, and many times she forwards posts that she finds funny. And so do many of my friends. And in 99.9% of what my friends share with me, they are very funny and worthy of interest.

Yet, in the remaining 0.1%, I do scratch my head. Recently, I arrived back from work and just before tucking into my dinner, I checked a particular Whatsapp group. The first thing I saw was a post about politics that captivated me. I replied to that, the next one I opened made me literally nauseous. I had to pause for a while before I was able to face my dinner. Why is this funny? I wondered. And if the person who posted thought it was funny, why couldn’t he keep it to himself? It was the last straw that broke the camel’s back for me for that particular group. This is not the first time I would exit WhatsApp group due to content and I doubt it will be the last time.

I concluded that the things that we consider funny/interesting/worthy of sharing speak volumes about us. Yesterday, after watching a clip forwarded to me, I lamented that the content was depressing and the fact that there is no context to the content was disturbing. If people share content about miscarriage of justice, oppression, poverty, etc., and provided the context, and we can do something about it, our actions can ameliorate our depression. However, if people share human misery without context, what is the point when we are powerless to advocate or act? For all we know, it could be an event that happened twenty years ago.

Before you forward the next viral video/audio/comments/images, please pause to reflect: does it demean others? Would you be proud to be associated with such a post if it is shouted out on the roof top, outside, the safety and privacy of your WhatsApp group? Always note that the things you forward, even if you are not the author, even if you are sharing in private, speaks volumes about you.

February 5, 2022

The Palm Wine Drinkard by Amos Tutuola

This evening, I was blown away by the immensity of Amos Tutuola, the author. He had just six years of education and trained as a blacksmith, practicing that trade for the Royal Airforce during World War 2 (read more here). Other vocations he tried was selling bread and messenger. While working as a messenger, he probably started writing the book. Think about this: a man with only six years of formal education, who worked as blacksmith, bread seller and messenger decided to write a book in the 1940s, and he wrote that book in English! It takes some self belief and courage to attempt a feat like this.

The second thing that amazed me was the person who acquired this book for publication. It was TS Eliot, the celebrated poet. Eliot was the author of “The Journey of the Maggi” (read it here).

It was the comment of one of the great French philosophers, Jean Paul Sartre, father of Existentialism, about Amos Tutuola’s works that I found most amazing:

it is almost impossible for our poets to realign themselves with popular tradition. Ten centuries of erudite poetry separate them from it. And, further, the folkloric inspiration is dried up: at most we could merely contrive a sterile facsimile. The more Westernized African is placed in the same position. When he does introduce folklore into his writing it is more in the nature of a gloss; in Tutuola it is intrinsic.

For TS Eliot and JP Sartre to both consider the works of Tutuola valuable is a remarkable achievement. Furthermore, his books have been translated into several languages.

Of course, he had his fair share of criticism but in the process of time, Tutuola’s work was valued and considered unique in style, and Tutuola’s work was seen in the same light as that of the likes of James Joyce and Mark Twain. Two of Nigeria’s most accomplished authors, Wole Soyinka and Chinua Achebe both affirmed Tutuola’s contribution to literature.

January 29, 2022

Nigeria 2023 Elections: Any Reason To Be Excited?

A friend sent this clip again last week. It is over four years old and I have received it many times.

Every election year, as Nigerians, we are very excited. I remember the euphoria that accompanied President Buhari’s winning of the APC ticket in 2014. There were reasons for Nigerians to be excited, if you looked at the facts. Buhari remains one of the least corrupt to run for the highest office with a chance of winning. On a personal note, I wanted Buhari to be president rather than Jonathan Goodluck simply because I agreed with the Economist that Buhari was the “least awful choice” of the two. I wrote at the time that Buhari’s impact on Nigeria will be marginal. The reason I gave were the people around him, who were all working to enthrone him.

In my network, it was those who saw Buhari as our saviour, rather than the “least awful choice”, who are the most disappointed. Some of them have given up on Nigeria and are busy blaming the “Fulanis” for all our trouble. These days, you see them advancing various flavours of restructuring. At times, they also indulge in blaming Islam and Christianity for our problems, forgetting that Islam has not stopped United Arabs Emirates to progress while the largest economy in the world, America, sees itself as a Christian nation.

The salient point we miss is that in most of the democracies around the world, political networks win election. In the UK, it is either the Labour Party or the Conservative Party that will produce a Prime Minister. In the US, it is either the Democratic Party or the Republican Party. It is the nature and character of the political network at a point in time that determines how much change can come through a leader. Even a maverick leader like Trump was vastly limited in the changes he was able to make.

This is why the words of El-Rufai here are very revealing. While talking about youth involvement in politics he made the following points about how the youths can make progress in the existing political networks:

You have to fight for powerYou need to negotiateYou need the support of the leadership.

To El-Rufai, leadership is about power. staggering, but i can’t afford to be distracted into examining this.

These comments do not just apply to aspiring younger politicians, they equally apply to the man who would be president: he needs to negotiate with his political party in order to win their support. It is the nature and character of his political network that determine the compromises that the would be president would have to make in order to gain the support of his party. Those compromises would become constraints on what he would be able to do or not do in office.

My interpretation of El-Rufai’s comments is this: if you want to lead, come and submit yourself to our system. If you do and work hard, you might just get the opportunity to serve, but only on our terms. if you are only able to serve on their terms, what are your chances of bringing in the change we desperately seek?

This is why I am not excited about 2023. Is there another dimension to this that I am missing? I would like to be educated.

January 23, 2022

Justice in Plato’s Republic versus The Golden Rule

A throwaway statement by Cephalus, a rich Athenian, resulted in a long debate on Justice. That debate was recorded in a book titled “The Republic” written by Plato. Cephalus said the benefit of his wealth was the ability to do the right thing and pay one’s debt, one less thing to worry about as he approached the grave.

It is not always right and just to pay one’s debt, Socrates opined and provided an example of returning a weapon you borrowed to a man whom you know would use it to harm others. Polemarchus agreed and tried to redefine justice as benefiting one’s friend and harming one’s enemies. If your friend is evil, is it just to benefit him? Socrates queried. Polemarchus agreed that this will not be right and redefined justice as benefiting one’s friend if he is good and harming one’s enemy if he is evil.

Socrates found issues with this new definition. Our judgment about people is not always right and he argued also that it is never just to harm others. At this point, Thrasymachus came in with a rather controversial opinion: justice is what is in the interest of the stronger party. He pointed to how government made laws that are in its own interest, rather than what is in the interest of the subjects.

Arguing against this, view, Socrates used professionals such as medical doctors and sailors to show that stronger parties do their job because of their interest in the subject matter, rather than just to benefit themselves.

Thrasymachus disagreed, arguing that a shepherd does not look after his flock because of the welfare of the sheep, rather, there are other benefits that motivates them to discharge their duties. Furthermore, the just man who care about justice and tries to do the right thing always comes off worse than the unjust man in any business deal between the two. Socrates disagreed arguing that rulers do not rule because they wanted to benefit themselves, rather, they do so to avoid being governed by unjust men. Assuming that to be unjust requires one to work just towards only one’s own interest, Socrates said injustice is a source of weakness because two people collaborating together have to be fair to one another and will be stronger than somebody just pursuing his selfish interest.

The argument carried on between Glaucon, Adeimantus and Socrates. Glaucon argued that justice is a matter of convenience; the appearance of being just is more beneficial than being just. As humans always pursued their own interest, justice and morality arose in human societies to keep some order. Were we to remove sanctions, the just and unjust man would behave in identical manner. Adeimantus concurred, saying that people pursue justice just for the benefits: it pays better or because they want to avoid sanctions in the afterlife. Glaucon an Adeimantus challenged Socrates to show that justice is worth pursuing on its own rather than for the benefits and sanctions that go with it.

This is a brief summary of Part 1 of Plato’s Republic and just a tip of the iceberg of this discussion. Just as it was then, matters of justice and doing right remains a matter of controversy. No wonder we have a branch of philosophy called Situation Ethics, which suggests that what is moral depends on the circumstances. The UK government is currently embroiled in some controversies on actions of some within it during the lockdown. As it defends itself, it tries to use the “exceptional circumstances” of the period: this is a defense rooted in situational ethics.

By the way, I have only covered the first out of eleven parts of Plato’s Republic. Do we really need one of the greatest philosophers in Western tradition to grapple with doing the right thing? Aren’t there simpler approaches to working this out? For me, the Golden Rule is a more accessible approach

One day, the Pharisees came to Jesus and wanted to know which one is the greatest commandment. This was Jesus’s reply (Matthew 22: 37-40):

‘Love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your mind.’ his is the first and greatest commandment. And the second is like it: ‘Love your neighbor as yourself.’ All the Law and the Prophets hang on these two commandments.

When it comes to doing the right thing and justice, the Golden Rule is simpler. It is a matter of asking a simple question: how will I feel if I am on the receiving end of this? If we all weigh our actions in the light of how we would feel if it is us on the receiving end, we won’t need intense debate and discussions nor the thoughts of the large than life Plato on what it means to do the right thing.

January 20, 2022

Not Yet Time For Self Congratulations

The UK Government funds the Office of National Statistics (ONS). The ONS gathers all sorts of data about the United Kingdom. Those datasets are invaluable when we have to draw inference and describe various aspects of our lives – from health to economics.

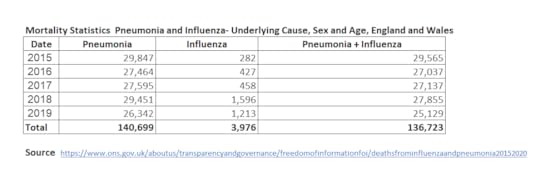

The Freedom of Information Act of Parliament dates back to 2000 (see it here). The act empowers citizens to request information held by public authority. Thanks to this act, sourcing the data needed to compare COVID19 and Influenza by mortality was easier than expected. On 30th of November 2020, somebody asked the ONS to provide the data it held on influenza mortality rate between 2015 and 2020. You can see the response from ONS here. The key outcome is this table, copied from the same location:

Over 5 years, there were 3,976 deaths due to influenza, an average of 796 deaths a year. When you add pneumonia which tends to occur with flu, the mortality rate goes up to 27,345 a year.

In the rest of this article, I have link to some of the datasets I used. If you don’t want to download those links to your device, please do not navigate to them. The data sources are reputable ones and only contain data in either Microsoft Excel or comma separated formats.

The ONS also gathers COVID19 data. The latest data published for 2022 is here. If you follow the link and you have an app that can read Microsoft Excel file, you can go to the tab captioned 5 to see the details of COVI9 records for January 2021 to January 2022. It will show a total of 73,759 deaths. The ONS has data for Jan 2020 to Jan 2021 and you can find it here. This showed that England and Wales recorded a total of 80,830 deaths between January 2020 and January 2021. We can deduce average yearly mortality rate due to COVID19 is 77,295. This means COVID19 is almost three times deadlier than Influenza and Pneumonia.

Of course the UK Government would naturally prefer not to use this metric to view the pandemic, probably preferring Deaths to Cases ratio, which can be used to justify a lower death rate. Comparing COVID19 to Influenza is a false equivalence because the former is almost three times deadlier than the latter.

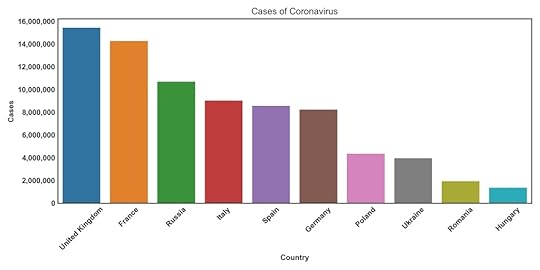

As our government here loves to tell us how wonderful we are doing compared to other countries in Europe in our COVID19 fight, let’s look at whether there is evidence to support this.

Below I show the top ten countries in Europe by cases of Coronavirus (data source) since the beginning. The United Kingdom tops this chart. We have close to twice what was recorded in Germany, Spain and Italy. Health professionals have highlighted the emergency of “Long COVID” in some COVID19 survivors. This means that there may be cost (health and otherwise) attached to a policy that supports huge number of COVID19 incidence as we currently do, in the long term.

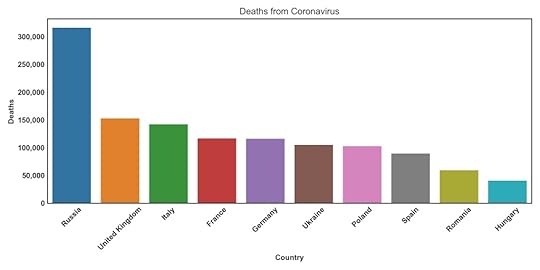

You can also see the top ten countries in Europe by mortality (data source):

Russia leads the way, followed by the United Kingdom. Whether you look at the number of cases or number of deaths, the United Kingdom is in the Top 2 in Europe. Not yet time for self congratulations.

The total number of deaths in in the United Kingdom was 527,234 in 2019 (source), 614,114 in 2020 (source) and 585,899 in 2021 (source). Compared to 2019, 2020 saw a rise of 16% in deaths, while 2021 saw a rise of 11%. Is it really time for self congratulations, rather than sober reflection? How can we be patting ourselves on the back faced with these horrendous statistics? Is it not too premature to compare COVID19 to Influenza when the latter represented only 4.9% of the deaths in 2019? Where is the evidence that we have weathered COVID better in the UK than the rest of Europe?

December 26, 2021

Mine Boy by Peter Abrahams – Review, Part 2

If you have not read the first part of this review, please follow this link.

In the first part of the review of Mine Boy, by Peter Abrahams, we followed the first few months of Xuma in the city. Xuma cultivated three relationships in those first months. The first one was a mother-son relationship between Xuma and Leah. The second relationship was an on and off love affair with Eliza. Lastly, Xuma became friends with Maisy, who loved him and believed Eliza’s relationship with Xuma would end in tears. Xuma, heartbroken by Eliza’s unwillingness to be all in, left Malay camp for three months.

One day, Xuma went on a walk and ran into his boss, Paddy (nicknamed “the red one”), and his “woman”, Di who was also white. They persuaded Xuma to come home and eat with them. Finally, he saw the things that white people had: electricity, radio, wine (without fear of arrest), etc. Xuma believed it was foolish for Eliza to think black people could have those things. Di noticed Xuma wanted to talk about something but he was reluctant to open up. When Di started smoking, a habit that Eliza also had, Xuma poured out his heart and said of Eliza:

She’s a teacher and wants to be like white people. She wants a place like this, place and clothes like yours and she wants to do the things you do. It is all foolishness for she is not white. But she cannot help herself and it makes her unhappy sometimes… It makes me unhappy too, for she wants me and she does not want me. But it is foolishness

This passage highlights the cruelty of apartheid or any system of discrimination: Eliza suffered depressive bout just for wanting the things that the group oppressing her wanted; good things that any right-thinking human should desire; she was laden with guilt because of this and could not give her heart to the man she loved. On the other hand, Xuma could not understand why black people should desire amenities and household goods that made life more enjoyable. Apartheid had messed up the thinking of both Eliza and Xuma.

Di then proceeded to educate Xuma (whom she calls Zuma) about human nature:

Listen Zuma. I am white and your girl is black, but inside we are the same. She wants the things I want and I want the things she wants. Eliza and I are the same inside, Truly Zuma… It is so Zuma, we are the same inside. A black girl and a white girl, but the same inside.

Xuma could not see it. Paddy turned up and the discussion ended. I have no doubt the voice that Di represented was that of Peter Abrahams, the author, at some point in his life. Abrahams, a mixed-race young man, became a Christian while being mentored and tutored by white tutors. At the time, he said

I was a full member now of the fellowship of the Christ who offered life, who taught: ‘Love thy neighbour as thyself’. Read more here

“Love thy neighbour as thyself” does not specify race, colour or creed. If radio and electricity are good for the whites, they should also be good for the blacks and mixed-race people. As time went by, Abrahams struggled to reconcile the violent racism he experienced with Christianity:

“What made it so very difficult for us was the fact that the equation did work out with the fathers but we had proof that the rest of the white Christians of our land were not like the fathers and the sisters. The equation did not work out. And in the harshness of our young idealism, we demanded that it work out as logically as a problem of mathematics. And it did not. Where was the error: in man or God?” Read more here

Like Abrahams, Xuma struggled to see the brotherhood of humanity, the fact that a white girl and a black girl can want the same time when the apartheid system that benefited the white people, oppressed black people violently. Xuma thought black and white must be inherently different.

Di and Paddy debated Xuma after he departed. Di thought Xuma was not human yet, simply because he did not think it right for his black girlfriend to want the same thing as a white girl. Eating, drinking and a sense of dignity and pride was not enough to be human because animals also have these. Di went on to accuse “progressives” of trying to create black people in their own image. Di felt that progressives are not progressive enough until they are ready to accept that not only can black people lead themselves but they can also lead white people. In other words, racism and progressive values are not compatible. We have this problem in multi-cultural societies today. Often, the “good immigrant” is the one who is happy to forget his culture and adopt the culture of his newly adopted country and immigrants are expected to be grateful for what they have and know their place.

Di said Eliza’s capacity to like the things that white people want and to resent her liking these things provides hope for her. Paddy on the other hand believed that Eliza was already a disaster. While I won’t go as far as agreeing with Paddy, to have such an unresolved tension is not psychologically healthy; it is something that guarantees a regular cycle of depression.

Things did not get better when Xuma found himself in the house of a black doctor and saw more of the white people’s things than what he saw in the house of Paddy and Di. Xuma was amazed and remarked: This is like the white people’s place! The doctor and his wife laughed and provided this reply:

Not like the white people’s place. Just a comfortable place. You are not copying the white man when you live like this. This is the sort of place a man should like because it is good for him. Whether he is white or black does not matter. A place like this is good for him. It is the other places that are the white people’s, the places that they make you live in.

In other words, when you reject and resent oppression, be very careful not to reject and resent with it those things that can improve your life.

Things began to unravel at Malay Camp. First, Daddy died, the chief mourners being Ma Plank, the woman who loved him, and Leah, the woman he brought up. Eliza’s on and off relationship with Xuma ended tragically when she ran away, leaving no address, still professing her love for Xuma but making it clear she would never return. Xuma entered a cycle of depression. The whole situation was very hard for Maisy, who was still in love with Xuma.

To make matter worse, the police finally cornered Leah and she was jailed for nine months on the charge of selling beers, the same beer that white people were free to have and keep in their homes. There is a link with Abrahams’ life here, who was forced to leave school when his aunt, Mattie, was arrested for selling homemade brew.

Those two events threw Xuma into a depressive cycle. He was showing up at work but he was no longer himself. It was another encounter with Paddy, his boss at the mines that woke him up. Paddy challenged him that first a man has to think like a man in order to understand both black and white men. Paddy said the reason blacks are oppressed in South Africa was because the whites were thinking as white people. This discussion changed Xuma’s outlook. Xuma came out of the cocoon into which racial injustice forced him. We can read about Xuma’s transformation in Abrahams’ words in Mine Boy:

Xuma got to his room and undressed without noticing it… And above all, this was man. Man, the individual, strong and free and happy, and without colour. Man alive. Pushing out his chest and being proud. Man in his grandeur

The passage above is very consistent with how Western Civilization perceives man. Man as an agent of change who is capable of exceptional acts (and may I add terrible ones too). This is not a universal viewpoint. Before colonization, Africa was community centred. Despite the ravages of colonization and neo-colonization, the importance of community/clan/extended family is still very visible in African culture. The same is true of China and several parts of Asia. India, with its arranged marriage system has a divorce rate of 1%, China has just 0.3% while the UK has 33.3%. The pandemic has also showed us the downsides of the focus on the individual and all his rights, but at times, at the expense of the community. People don’t want to be vaccinated because it is their human right to choose what goes into their bodies, but they don’t want to consider the impact of their choices on their neighbours that they should love as themselves.

Back to the transformed Xuma. The next day at the mine he heard that Johannes (JP Williamson) and Chris, his white boss sacrificed their lives to save other miners who were trapped in the mine. When the order was given for all the miners to go underground, Xuma led a revolt. Paddy sided with Xuma and the black miners. The police came, Paddy was arrested while Xuma ran away as Paddy implored him not to do so.

Xuma ran to Maisy and Ma Plank. When Ma Plank heard what happened, she beseeched Xuma to run away but he replied:

The Red One (Paddy) is in jail. I must go there too. It will be wrong if I do not go. I would not be a man then… The Red One is not a black man and he is going to jail for our people, how can I not go? And there are many things I want to say too. I want to tell them how I feel and how the black people feel...It is good that a black man should tell the white people how we feel. And also, a black man must tell the black people how they feel and what they want. These things I must do, then I will feel like a man

Despite Xuma’s impending stint in jail, the book ended on a very good note, with Xuma proposing his love to Maisy and Maisy promising she would wait for Xuma, however long it takes.

In the first page of Mine Boy, we were introduced to a young man who knew his place in life and was just focused on fighting for food, clothing and shelter in the oppressive environment created by apartheid. He saw the world in two separate boxes: black and white. He accepted the status quo: he had no rights and it was foolish for him as a black man to want the things of the white people. Through his experiences and pain, we parted from Xuma at the end of the book as a freedom fighter, who believed in something: the value of the life of a human being. By standing up to lead the strike of the miners, he put his own comfortable life on the line. Implicit in that confrontation was the acceptance that white and black people can aspire to have the same thing. He had the chance to run away but he didn’t because he felt that it was wrong for Paddy, the Red One to suffer for the cause of black people while he ran away.

The Mine Boy was thinking like a man, rather than a black person.

If you have not read the first part of this review, please follow this link.

December 18, 2021

Mine Boy by Peter Abrahams, Review – Part 1

The first time I read “Mine Boy” by Peter Abrahams, it was one of the English Literature texts at high school. My enduring memory was the love triangle between Xuma, Eliza and Maisy. Re-reading as an adult, there are other dimensions to the book that are fascinating. I start this review with an introduction to the main characters.

The Main Characters

Leah is the most significant character in the book. Our first encounter with her was in the very first page. She was the head of a very strange household at Malay Camp, a household that seemed not to believe in anything and without any kind of tie. Xuma, the Mine Boy, described Leah as “tall and big, with heavy hips and sharp eyes that can see through a man”. Those sharp eyes saw through Xuma, a complete stranger, and within minutes, assessed his character and judged him worthy of joining her household. The book revolved around Xuma, the mine boy. Xuma arrived at Leah’s house at 3.00am in the morning, “thirsty, hungry and exhausted”. Leah perceived a man with “deep and husky voice, big and strong”. He had travelled from the Northern part of South Africa to look for work. Leah welcomed him in, thereby setting up a trail of event that would change Xuma from a young man fighting for survival, into a man who championed the cause of other mine boys. The next big character in the book was Eliza, the teacher. Unlike Xuma and Leah, Eliza was well educated. Later in the book, Paddy who never met Eliza but heard about her from Xuma, described Eliza as a social animal. Xuma and Eliza fell in love but Xuma did not meet Eliza’s expectations. Eliza was Leah’s niece and she was known in Leah’s household as the one who “wants the things of the white people”. Eliza loved Xuma but there was a snag: he was not educated. She preferred a man who was educated, smoked, drove a car and wore suits everyday. In her own words: “inside me there is something wrong and it is because I want the things of the white people and go where they go and do the things they do and I am black. Inside I am not black and I do not want to be a black person”. Eliza knew her attitude to Xuma hurt him but she was helpless. She even asked Xuma to beat her and hate her but Xuma was filled with lover for her.In big contrast to Eliza is Maisy, a happy woman whose “laughter rang out loud and hoarse and friendly”, a woman who waved and smiled at strangers in the street. Maisy was the third person in the love triangle. She was in love with Xuma but Xuma was too obsessed with Eliza whom he described as a disease in his blood. It was Maisy who lifted up Xuma’s spirit each time Eliza fired a poisonous arrow into his heart of love. Even in the presence of Maisy, Xuma continued to wish his happiness was coming from Eliza.The Author, Peter Abrahams

It is always important to know more about the author as it helps to put the story in perspective. Abraham’s father was Ethiopian and his mother was mixed race. Abrahams was born in Vrededorp. The book is set in Malay Camp, Vrededorp. After his father passed away, Abrahams was sent to live in Elsburg, a rural town in Gauteng Province located in the northern part of South Africa. It is possible that Abrahams drew on his experiences in Elsburg to construct the character of Xuma and part of the plot.

The Book

Leah believed black people needed power and also that money is power. Her business was selling beer illegally to black and mixed race people in Malay Camp. To be able to evade arrest, she paid informers in the police. Xuma was perplexed that Leah, who was kind to a complete stranger like him, did not tell the other black people when the police came to raid. Yet, when they were arrested, she contributed money to help towards their legal cost. Leah, a pragmatist would reply that if the police came to raid and they didn’t catch anybody, they would know that there was a leak.

Xuma was also puzzled by the relationship between “Daddy”, one of the resident of Leah’s household who was always drunk, and Leah. Why did Leah, such a strong and purposeful person, respected such a man, he wondered. One day, another resident of the household, Ma Plank, who loved Daddy, explained that Daddy raised Leah and used to be a respected man in Malay Camp to whom everybody looked up to. Daddy in his present plight showed what that strange place called the “city” did to men, especially, when they realized that no matter how hard they worked, they are not making a difference. Many resorted to the bottle to cope with live under apartheid. A good illustration of this problem was JP Williamson, one of the “boss boys” in the mines of South Africa. It was Johannes who used his connections to secure a “boss boy” role for Xuma in the mines. At the weekend when Johannes was drunk, he shouted ” I am JP Williamson and I will crush any sonofab***h. On a weekday, he is subservient to his masters in the slums, and as meek as a mouse.

On his first day at the mines, Xuma cleared the heap of sand dug up from the mines. However the harder he worked, the higher the pile of sand grew. His heart sank. He was frightened by:

The seeing of nothing for a man’s work. The mocking of a man by the sand that was always wet and warm; by the mine dump that would not grow, by the hard eyes of the white man who told them to hurry up.

This captured the intolerable and inhuman condition of work in the South African mines; the harshness of the city where the indigenous people, having been dehumanized, were treated as if they were machines. It was a picture of life under apartheid and colonialism, where there was a colour bar and no matter how hard you work, certain things were unattainable.

How did the miners cope with this? Nana, an experienced miner described the process of adaptation:

It is hard when you are new, but it is not so bad. With a new one it is thus: First there is a great fear, fear for your work and there is nothing to see for it. And you look and you look and the more you look, the more there is nothing to see. This brings fear. But tomorrow, you think, well, there will be nothing to look for and you do not look so much. The fear is less then. And the day after you look even less, and after that, even less, and in the end you do not look at all. Then, all the fears go.

This is not only true of the mines but of the plight of majority of blacks and mixed race people in apartheid South Africa. To me, this is an imagery of somebody or a group of people seeing a bad situation and wanting to change it. However after toiling and toiling and not seeing any improvement, people resign themselves to the situation and adjust to the new normal. This problem exists in virtually every country today.

Eliza and Xuma represented two different reactions to apartheid. Xuma was conditioned to survive and accept that certain things were for the white people while others were for black people. He considered black and white as mutually exclusive sets. Xuma believed the desire of Eliza to have the things of the white people was futile. Eliza on the other hand, probably due to her education and exposure, wanted the “things of the white people”. Unfortunately, her desire felt like a betrayal of her own people (Leah, her aunt who brought her up, Xuma, the man who love her), therefore, she was laden with guilt. There is no doubt what she experienced were depression bouts.

Xuma resented white people because he felt they were the source of Eliza’s confusion. To avoid Eliza, he kept away from Malay Camp. He was thriving in the mines and was a “boss boy”. A boss boy was a black or mixed race man who led, motivated and supervised a cohort of miners. Xuma did the job well and his “white man” (his boss) had nothing to do, apart from sitting in the shade. Paddy (his boss), an Irishman, wanted to be friends with Xuma but Xuma did not believe it was possible for whites and blacks to be friends.

Look out for the concluding part of the review to see how the journey of Xuma ended.