Clayton M. Christensen's Blog, page 11

April 14, 2016

When Innovators Fail: Frustration, Wishful Thinking, and the Building of an Innovation Engine

If an athletic department at a large university made a decision to develop a world class rowing program, but the university administrators banned all water sports as too risky, we could hardly expect much in terms of rowing greatness. However, all too often large corporations do the equivalent when they decide to pursue non-core innovation efforts. They set business boundaries so tightly that it is impossible to discover new growth platforms.

Innovation is often cited as a top three strategic priority for many corporate leaders, and if there is one topic that gets their attention, it’s building innovation capabilities within their organizations. The prospect of having a crack team of internal innovators churn out new growth businesses is certainly attractive.

Setting the right boundaries

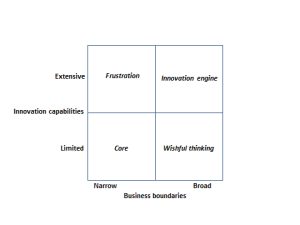

Yet, before companies start to tackle the many challenges of getting the innovation engine humming, they need to address two key questions; namely “why do we need an innovation team” and “where and how will we deploy the team.” We encounter all too often companies that are determined to develop strategic innovation capabilities, but have defined very narrow business boundaries within which those capabilities will be deployed. Sometimes we see broad and well defined business boundaries, without any credible plan to build the requisite innovation capabilities. The first results in frustration, other second is simply wishful thinking.

Yet, before companies start to tackle the many challenges of getting the innovation engine humming, they need to address two key questions; namely “why do we need an innovation team” and “where and how will we deploy the team.” We encounter all too often companies that are determined to develop strategic innovation capabilities, but have defined very narrow business boundaries within which those capabilities will be deployed. Sometimes we see broad and well defined business boundaries, without any credible plan to build the requisite innovation capabilities. The first results in frustration, other second is simply wishful thinking.

You can map out the simple options in a simple two by two (see chart).

In the first scenario (the one that leads to frustration), companies build innovation capabilities, but define the business boundaries so narrowly that it’s impossible, even for a crack innovation team, to find meaningful new growth opportunities. If the business boundaries are so close to the core business, typically all the opportunities therein have either been investigated by the established business units and are actively pursued or have been discarded as unattractive. In either circumstance, there is little for the innovation team to do except to catalogue and categorize the opportunities.

Learning from a dead end

An episode at a large conglomerate we advised exemplifies the challenge. The company wanted to build innovation capabilities in all of its business units (BUs). The problem was that some of those BUs had very tight business boundaries and actually it made little strategic sense to expand them. Despite long discussions about the dangers of applying a ‘one size fits all’ model to building innovation capabilities, the company ultimately decided to develop identical innovation capabilities across the BUs. The warning signs were quickly manifested: The teams sensed that they had been given an impossible task and voiced their frustrations.

The good news is that the company learned from going down that dead end. A few years later, after the teams were disbanded, the BUs focused all their efforts on the core, exactly as they should have done from the beginning. But meanwhile, in the other BUs that had more expansive boundaries, the innovation teams were able to identify and launch several new business models that grew into real businesses.

The lesson here is clear. Don’t build extensive non-core innovation capabilities without first expanding the business boundaries. Doing so will lead only to frustration; indeed, the better trained the team members are, the more frustrated they will become.

When innovation is just a wish

The ‘limited capabilities, broad business boundaries’ quadrant has the opposite problem. Here companies define expansive boundaries for non-core innovation without investing in the corresponding innovation capabilities. The challenge with this approach is that without the resources, systems, processes, skills and capabilities needed to pursue new opportunities, the frontier that the leadership has defined cannot be effectively explored or developed.

We recently saw an example where a large financial institution had defined several new strategic growth areas. However, they decided to pursue those opportunities with an inexperienced team that had never done anything material in the area of business model innovation. Even worse, the teams were small, part time, junior, and had little leadership support. Topping it all off, the half a dozen strategic opportunity areas that had been identified were complex, competitive and expansive.

The mismatch between the public announcements and the actual resources committed to achieving the goals could not have been starker. Here the outcomes of the innovation efforts are highly predictable. Without systematic investment in and development of innovation capabilities, it’s impossible to discovered and launch profitable and scalable business models. Simply put, it’s wishful thinking.

Rules for launching an innovation engine

To avoid the frustration and wishful thinking and to build a real innovation engine, companies must address innovation capabilities and business boundaries as two sides of the same coin. There are five simple rules that help companies navigate this space.

Ensure innovation capabilities and business boundaries are aligned.

The business boundaries should be defined by the size of the growth gap and the strategic capabilities & assets of the company.

The investments in innovation capabilities should be defined by the growth gap and the business boundaries.

A long term plan with requisite investments should be put in place and top talent must be assigned to the team.

The leadership must remain closely engaged with the innovation initiatives.

If companies can’t align business boundaries and innovation capabilities, it’s better to focus only on the core business, because the outcomes of misaligned innovation efforts are highly predictable. One will result in frustration and the other is simply wishful thinking. For the innovation engine to hum, the innovation capabilities and business boundaries must be aligned.

Pontus Siren is a partner at Innosight based in Singapore.

March 21, 2016

The Food Waste Opportunity: How Experiments Can Open New Growth Markets

The country of France recently passed a law outlawing supermarkets from destroying or throwing away unsold food. By specifying steep fines for failing to donate discarded food to charities, France is reacting to an out-of-control problem in wealthy countries: roughly a third of all produced food ends up in the trash-an environmental catastrophe that persists even as millions of people go hungry or undernourished every day.

The country of France recently passed a law outlawing supermarkets from destroying or throwing away unsold food. By specifying steep fines for failing to donate discarded food to charities, France is reacting to an out-of-control problem in wealthy countries: roughly a third of all produced food ends up in the trash-an environmental catastrophe that persists even as millions of people go hungry or undernourished every day.

A better approach than a blanket law, however, is a framework of incentives that encourage experiments and entrepreneurship. Instead of viewing food waste as a crime, why not look at it as a market? In this case, it’s a matter of sparking enough demand to meet supply.

After all, there is plenty of wasted food out there–a staggering 133 billion pounds annually in the U.S. alone. That is more than a pound of wasted food a day per person, and nearly $900 a year in wasted food per household . Food waste is now the major component in landfills. The question is: what can we do with it?

A Cinderella transformation

At Disney World in Orlando, a different approach to food waste is going on behind the scenes. For decades, Disney has tolerated the problem of leftovers being tossed by the ton into garbage bins by restaurant workers and park goers.

But in 2014, the Magic Kingdom signed on to be the first customer for an “anaerobic digestion” plant built by Waltham, Mass. company Harvest Power. As food breaks down, anaerobic digestion captures the biogas that’s naturally emitted and converts it to energy. The facility near the theme park processes 100 tons of wasted food from Disney a day and each month produces enough electricity to power 36,000 homes in Florida. Leftover residue from the process is made into fertilizer sold to area farms.

This Cinderella transformation of discarded food is just one example of how marketplace experiments can help spur new growth markets. Venture capitalists are believers: Harvest Power has raised more than $350 million, making it one of the best-funded startups in New England.

The pilot project in Orlando is moving ahead just as a U.S. policy framework is starting to take hold. In September of 2015, the USDA and EPA announced the first national goal for reducing food waste. The target: cut America’s food waste in half by 2030. Following those guidelines, three New England states and three major cities have already set restrictions on food waste, some placing limits and some banning food waste in landfills entirely. For example, Massachusetts limits food business such as restaurant chains and supermarkets to one ton of landfill waste per week.

Because food is an organic compound and readily biodegradable, one might assume that all this waste is not a major problem. However, consider this. Food takes resources to produce-water, land, fertilizer, energy. It’s heavy and expensive to transport. As food lies in a landfill, it decomposes and emits methane – a gas 25 times worse for climate change than carbon dioxide. Lastly and certainly not least, there is a high social cost. Amidst the waste, 17.4 million U.S. households struggle to have an adequate amount of nutritious food.

Moving from stick to carrot

Food waste policy is hardly the only market to harness public policy for innovation and growth. In the last four years, federal and state incentive programs have propelled the U.S. solar energy to record installations. Accountable Care Organizations have proliferated in the wake of the Affordable Care Act to slow the rise of healthcare costs.

The challenge is to look past regulation as a stick to force compliance and instead identify the carrot of opportunity that is often hidden in the regulations. For Harvest Power, success is coming by taking advantage of a regulatory environment that incentivizes food waste recycling and breaks the “chicken and egg” gridlock.

Harvest Power is just one of dozens of companies and nonprofits operating today to reduce, reuse, and recycle food waste-and in the process creating growth and profit. All told, six billion pounds of food a year never even gets a chance to be purchased. That’s the total weight of “ugly” fruits and vegetables thrown away every year because of aesthetics.

Reducing, reusing, and recycling

Other startups working with large enterprises include Fruitcycle and Misfit Juicery. These Washington DC-based ventures have created products such as dried fruit snacks and smoothies made from ugly fruit. Others, like Hungry Harvest and Farm to Family, specialize in picking up imperfect produce from farms and delivering it for free or at a discount to people in need. There is even #uglyfruit and #imperfection hashtags now on Instagram as part of the rebranding effort.

On the consumer end, technology solutions are enabling an online marketplace, making an excellent medium for uniting those with unwanted food to those who need it. Spoiler Alert, Food Cowboy, and Foodloop are three such companies whose app platforms are enabling B2B and B2C transfers of unwanted food.

Also addressing the conundrum of surplus food is Doug Rauch, the former president of Trader Joe’s. His startup Daily Table is a nonprofit grocery store that sells surplus food donated from wholesalers and major supermarket chains. Along with providing low cost food, the store also prepares and sells fresh meals on site. Launched last summer in Boston, he has hopes to scale to other cities around the country.

Others are following Disney’s example and taking food waste recycling into their own hands, which is spawning the creation of new food waste ecosystems that are also new growth markets.

The supermarket chain Stop&Shop opened its first on-site anaerobic digester at a distribution center in Freetown, Mass. The company plans to produce its own energy by using food not suitable for sale or donation. Biogas is not the only product recycled from food waste. Harvest Power also sells compost, mulch, and fertilizer. Other companies, like Ecoscraps, focuses only on the landscape products, selling all-organic compost, soil, fertilizer, and other gardening products made exclusively from food waste.

Principles for pivoting from stick to carrot

By looking closely at how new growth emerges from these kinds of untapped market needs, we can distill five principles for how to evaluate opportunities in new markets and new regulations:

Evaluate the incentives in the new public policy regulation. As in the food waste market, innovators need to study rules and goal for both stated and hidden incentives that can lead to new products and services.

Consider customer needs at each part of the value chain. Some players in the value chain may want reduce costs, other may want to find new revenue streams, while others may feel that improving a customer experience or reducing environmental impact is a worthy goal. For example, a utility company could become the system integrator across energy/water usage and waste management.

Brainstorm the business models that could answer those customer needs. There are many places a new solution can plug into a value chain, leading to a variety of potential business models. Harvest Power, for instance, had to consider the many options for converting waste to energy, while Misfit Juicery had to decide the best way to reach its health-conscious customers.

Match those business models that line up with your existing capabilities, technology partners, and strategic goals.What does your company do best, and what new capabilities are you willing to build? How can those capabilities execute your growth strategy and deliver revenue growth?

Launch a pilot project to test & learn about your chosen business model. That is how many food waste startups began. Harvest Power, for instance, tested its technology as a pilot before launching into capital-intensive expansion.

This method of pivoting from stick to carrot enables you to perceive how new opportunities and regulations could lead to new capabilities, products, or business models. The food waste case shows that growth can come from unexpected places. Organizations that identify the right opportunities are the ones that can tap into an unexpected source of new growth.

Sarah Barbo is an associate at Innosight.

The post The Food Waste Opportunity: How Experiments Can Open New Growth Markets appeared first on Innosight.

March 15, 2016

How CFOs Can Take the Long-Term View in a Short-Term Economy

Investors are increasingly seeking firms with long-term growth strategies, rather than ones focused on managing short-term earnings to boost the stock price. This, in turn, is triggering a shift in the perceived role of the CFO — from bean counters to planters of seed corn.

No one has done more to spotlight the contrast than Laurence Fink, the CEO of BlackRock. As head of the world’s largest asset manager, with $4.6 trillion in holdings, Fink in February sent a letter to the CEOs of all S&P 500 companies that essentially cut the Gordian knot of short-termism. Companies have been paying sharply higher dividends and buying back their shares much more aggressively, he says, in order to please people like him. Fink is essentially saying: Stop it! Invest more of that capital in growing the company. Do away with the game of quarterly earnings guidance, and instead articulate to investors your “strategic framework for long-term value creation.”

Backing this up is another group of asset managers who have committed $2 billion to invest in a newly created S&P Long-Term Value Index, a subset of companies doing things right. “We are trying to use the index to change corporate behavior,” said Mark Wiseman, chief executive of the Canada Pension Plan Investment Board, the lead investor in the initiative. Wiseman has helped start Focusing Capital on the Long Term, a new institute that also counts Barclays and Unilever as founding members.

Redefining the CFO role

For CEOs, creating and communicating long-term growth strategy is easier said than done. After all, it’s the CFO who typically sets expectations about growth to investors and then allocates resources to ensure their organizations deliver. CFOs know exactly the role that their company plays in their investors’ portfolios. So if the organization is going to invest in longer-term growth, this could increase the stock’s beta — both in downside risk and upside reward.

That’s why the CFO needs to take charge of telling that growth story to investors while clearly communicating the higher beta. Knowing how to frame and tell this story is critical for a CFO wishing to manage the natural tension between inspiring and scaring investors.

Some leadership teams have served as guiding examples of how to overturn short-termism and reorient their enterprise. In 2010, when Mark Bertolini, CEO of Aetna, began articulating a strategy to invest billions to transform from a health insurance company to a health care company, analysts grumbled. “If you don’t like our strategy,” he told them. “Then get out of our stock.” Many did. But the shareholders who left were replaced by ones who believed in the long-term strategy.

March 3, 2016

Where Zombie Projects Come From – And Why Killing Them Needs to Be Systematized

I was recently in a meeting with an innovation manager at a large company who told me about all the projects he was overseeing. When I asked who was actually working on these efforts, he mentioned there were some part-time internal people and some external contractors. I told him politely that it was highly unlikely that any of these efforts would yield any tangible business outcomes. We finished our coffee, and I’m sure that when we chat next, there will be yet more “zombie” innovation projects—walking dead efforts wondering the corridors of the company.

They say that in real estate there are only three things that matter: location, location, location. One might paraphrase and say that in innovation only three things that m atter: focus, focus, focus. While it’s true there are many other things that matter in innovation, there’s no doubt that focus is hugely important.

atter: focus, focus, focus. While it’s true there are many other things that matter in innovation, there’s no doubt that focus is hugely important.

As I took the taxi back to the office, I started to think about why innovation zombies are so prolific and where they come from. I came up with five culprits:

1. Lack of strategic direction related to innovation

2. Well intentioned ideation sessions and workshops

3. Illusionary safety sought from large number of innovation projects

4. Ease of starting projects compared to finishing projects

5. Difficulty of killing zombie projects

The first and most important factor behind the emergence of zombie projects is the lack of clarity on the role of innovation, especially non-core innovation, in an organization. Innovation is such an imperative in most companies that leaders feel compelled to do something. Building a portfolio of innovation projects is both concrete and actionable.

However, often there is no clear innovation strategy and organizations don’t have clarity on the objectives or boundaries of innovation. This lack of strategic direction allows for all types of efforts to proliferate, because when you don’t know where you are going, any road will take you there.

How good ideas become zombie projects

The second is a seemingly innocent source of zombie projects, namely workshops and ideation sessions. These sessions are conducted with the best of intentions such as energizing the organization, capturing the best ideas within the company, and exploring new opportunities and often that’s exactly what is achieved. Smart and experienced people can be expected to come up with good ideas and that’s exactly the problem. A good idea becomes a zombie project when it is made into a formal project, but one without strategic purpose, proper resources, leadership oversight and support or the structures and processes needed for innovation. The projects exist and they have enough life in them to be a drain on the organizations resources, but they never have any real possibility of becoming a driver of profit and growth.

The third reason for the proliferation of innovation zombies is that innovation teams believe that there is safety in number of projects they manage. There isn’t, but the confusion is easy to understand. Innovation teams face tremendous challenges in driving the innovation agenda within an organization. Often these teams are small and under resourced and they lack the strategic direction and leadership mentoring that is essential for innovation.

To compensate, teams sometimes seek to build a large portfolio of innovation projects, a kind of “Potemkin village” portfolio of non-serious projects. The motivations vary, but sometimes it’s done to show the leadership that real progress is being made, at others it’s simple done to keep the team busy. Whatever the reasons, innovation teams are often the unintentional authors of zombie projects.

Fourth, it’s much easier to start a project than to progress a project. The primary reason for this is that the resource requirements increase as the project matures. The development and de-risking costs are much higher in version 15 than they are in a first paper model. Thus, projects are started with a small budget and no one, not even the finance department, pays much attention. However, as the project advances, the resource requirements become much more substantial in terms of human and other resources. Those resources have to come from the core business that is usually less than eager to share scarce resources with the innovation team. If resources can’t be marshaled, but the project can’t be killed, it becomes a zombie. After one zombie has been created, the innovation team can be tempted to start a new project because they know they can get resources for an early stage effort which is actually just another zombie in the making

Killing off zombies systematically

Finally, as my colleagues have often noted, it’s extremely difficult to kill an innovation zombie. There are good reasons for this, but the two primary ones are that organizations are not good at dealing with mistakes and that they have no processes to deal with them. Killing a zombie implies having a frank discussion about the lessons of the effort, something that can be hugely valuable for any organization. However, few organizations have deliberate systems in place to allow this to happen. In their absence, people rather choose to let the projects live on without pushing to formally end them.

This reminds me of an old tale where a courtier who, having displeased the king, is threatened with death. To avoid his imminent demise, the courtier promises that he will make the kings horse fly in one year and his life is spared. His perplexed friends point out the enormity of the task, but the crafty courtier notes that in one year the horse might be dead, or the king might be dead or the horse might even fly.

Zombie innovation projects come from many sources, but innovation leaders must aggressively and humanly put them down so the organization can focus on those opportunities that can drive real business impact. As you pursue innovation efforts in your organization, make sure you understand where zombies come from so that you can stop their rise.

Pontus Siren is a partner for the growth strategy consulting firm Innosight.

March 1, 2016

What Do You Really Mean by Business “Transformation”?

Today’s corporate watchword word is transformation, and for good reason. One study suggests that 75% of the S&P 500 will turn over in the next 15 years. Another says that one in three companies will delist in the next five years. A third shows that the “topple rate” of industry leaders falling from their perch has doubled in a generation. Software is eating the world. Unicorns are prancing unabated. Executives at large companies rightly recognize that they need to respond in turn.

And yet.

When executives say transformation what do they really mean? Often, the word confuses three fundamentally different categories of effort.

The first is operational, or doing what you are currently doing, better, faster, or cheaper. Many companies that are “going digital” fit in this category — they are using new technologies to solve old problems. A big operational change can be jarring and drive real business impact, but it doesn’t fit dictionary definitions of transformation, such as “a marked change in form, nature, or appearance” or “to change (something) completely and usually in a good way.” Sure, costs will be lower, customer satisfaction might go up, but the essence of the company isn’t changing in any material way. And, in a quickly changing world playing an old game better is simply insufficient.

The next category of usage focuses on the operational model. Also called core transformation, this involves doing what you are currently doing in a fundamentally different way. Netflix is an excellent example of this type of effort. Over the last five years Netflix has shifted from sending DVDs through the mail to streaming video content through the Web. It also has shifted from simply distributing other people’s content to investing heavily in the creation of its own content, using its substantial knowledge of customer preferences to maximize the chances that content will connect with an audience. Customers still turn to Netflix to be entertained and to discover new content, but the fundamental way Netflix is solving that problem has changed almost completely.

The final usage, and the one that has the most promise and peril, is strategic. This is transformation with a capital “T” because it involves changing the very essence of a company. Liquid to gas, lead to gold, Apple from computers to consumer gadgets, Google from advertising to driverless cars, Amazon.com from retail to cloud computing, Walgreens from pharmacy retailing to treating chronic illnesses, and so on.

February 2, 2016

Changing the Story of Innovation: How to Create Happier Outcomes for New Ventures

The workshop at a large global consumer products company ended in an unfortunate place. After an engaged discussion and the review of the first three years of a product launch, the group concluded that an entire product line should be shut down.

What mattered, though, wasn’t the outcome so much as its meaning. Someone mentioned that the past three years had been an all-too-expensive experiment; another participant opined that it hadn’t even been an experiment. The reasons for closing down the product line were obvious enough: powerful competitors with a better product, little product differentiation, premium pricing and a host of others. So why did this sophisticated and successful company launch the product range in the first place?

The group was puzzled. The obvious answers like poor management were clearly wrong. The same people were running a highly successful core business and obviously ran a tight ship. Yet, the cascade of events that led to our workshop is both typical and insidious, and it goes to the heart of decision making in large companies.

Seeing innovation as a three act play

The story usually starts the same way. The first act sees senior leaders discussing an exciting new strategic opportunity area (SOA). The opportunity is sizable and the company has the right capabilities and assets. The senior leaders quickly commission some additional studies and become even more convinced of the opportunity. The decision to move forward seems like a sensible one.

In act two, the leaders instruct the business units to start developing solutions. However, no dedicated resources are assigned and the part-time team has little experience in discovering and blueprinting new business models. The team members are still responsible for the core business and their key performance indicators (KPIs) remain unchanged. Predictably, little happens and by the end of act two, the senior leaders become increasingly frustrated by the lack of progress.

Towards the end of act two, the leaders become more directive and tell the business units to launch something. The business unit heads then decide that it’s politically more prudent to launch something rather than try to prove that there is no business opportunity in the SOA. After all, simply because they have not found a good business model does not mean that one does not exist. The product team is then directed to select the most plausible model but the team is very aware of the shortcomings of all the opportunities that they have identified.

The start of act three see a worried project team launching a new product range that they don’t believe in. We find senior leaders who are delighted by the new launch, business unit heads who are happy about maintaining their ‘can-do’ reputation, a project team that is relieved to focus on something else and a product range that is struggling.

As we head toward the climax of the story, the business units treat the new launch like another core business making additional investments into marketing, sales, production and the supply chain. The project continues to be managed by part time by those who have many other responsibilities and unrelated KPIs. The story ends up in a workshop where an open discussion quickly reveals that the product range has few chances of success and should be discontinued.

It’s revealing that at each stage of the process, the project team understood the shortcomings of the new business model and could accurately analyze why it struggled and ultimately failed. The challenge was not one of understanding, but rather one of the political dynamics around decision making and communication in a large corporate setting.

It’s these political dynamics that senior leaders have to address to re-write the play.

Working towards a happier outcome

There are five actions that could have led to a better place.

1. Follow a disciplined innovation process that mitigates the risks and uncertainties of business model innovation.

2. Dedicate experienced full time resources to the project. These resources can be internal or external, but they should have right skill sets and resumes. They should be supported by engaged senior leaders.

3. Align the motivations and priorities of the business unit leaders and project team. This usually means adjusting the KPIs, even on a temporary basis.

4. Insist on absolute candor in the project review meetings. Here it often helps to involve outsiders who can look at the opportunity dispassionately and objectively. Leaders must make clear that if the right innovation discipline is followed, there are no penalties in discontinuing a project.

5. Senior leaders must set learning rather than launching as the primary objective of the effort. The operative question must be: ‘what have we learned’ rather than ‘when will we launch’?

All these steps are no doubt different from how the core business operates. Different process, different resourcing, different KPIs, and different strategic objectives. It’s a form of leadership that requires flexibility and very deliberate decision making. However, these five steps are intuitive and simple and will significantly increase your chances of innovation success. Good luck!

Pontus Siren is a partner at Innosight based at its Asia-Pacific headquarters in Singapore.

December 18, 2015

How to Tell If a Company Is Good at Innovating or Just Good at PR

The video was beautiful. Obviously professionally produced, it highlighted the space the company had set up for innovation. Drone footage showed an open space replete with sticky notes. A 3D printer whirred in the background. A foosball table was involved. Clearly, money was being spent.

But further investigation showed that the video was nothing more than a beautiful piece of “innoganda” — innovation propaganda describing an effort that had little hope of driving any material impact.

In many organization, innovation has gone from fringe to buzzword to a must-have. There are a variety of legitimate reasons for companies to bolster their innovation capabilities, ranging from fighting against current and emerging competitors to raising morale and attracting younger employees.

There are companies that pursue innovation with rigor. Some are well-publicized innovation poster children like Alphabet (Google), Amazon.com, Disney Pixar, 3M, and Philips. Some are still under the radar screen, like Globe Telecom in the Philippines, Tata Sons in India, or DSM in the Netherlands.

These rigorous innovators direct innovation strategically, with innovation efforts integrated into strategic planning and resource allocation systems. They pursue innovation rigorously, with a disciplined process and supporting tools to help spot, shape, and seize opportunities to innovate. They resource innovation intensively, dedicating top talent to pursuing ideas rather than hoping that miracles will happen in free-thinking Fridays, special-purpose Sundays, or other constrained efforts. They monitor innovation methodically, making sure that the most-promising ideas are identified and accelerated, and the least-promising ideas are shut down before they turn into capacity-draining zombies. Finally, they nurture it carefully, recognizing that organizations are wired to operate today’s business more efficiently, not to experiment and discover tomorrow’s business.

Companies running innoganda campaigns, on the other hand, approach the problem in a piecemeal fashion. Maybe they hire a chief innovation officer but don’t give him or her any budget or staff. Perhaps, like the company in the video, they build a gleaming innovation lab that sits empty except for when the media, customers, or tax-break-providing government officials are around.

November 19, 2015

How Understanding Disruption Helps Strategists

Through the past 15 years my colleagues and I have wrestled with disruption in many contexts. That’s no surprise, since Clayton Christensen co-founded our company in 2000, five years after his Harvard Business Review article with Joseph L. Bower “Disruptive Technologies: Catching the Wave” introduced the idea of disruption to the mainstream market.

Christensen and two co-authors revisit where disruption theory stands today in a new HBR article, “What Is Disruptive Innovation?” And my company’s experience over the past 15 years – consulting with global giants, working alongside mid-sized companies in emerging markets, investing in wide-eyed entrepreneurs, and advising government officials – highlights four reasons why disruptive innovation theory should be a key component of any good strategist’s toolkit.

First, disruption directs you to look in places you might otherwise ignore. Christensen’s research shows that disruption often starts at a market’s edges. Sometimes that is in relatively undemanding market tiers, such as how mini mill manufacturers started in the rebar market. Disruption also takes root with customers that historically were locked out of a market because they lacked specialized skills or sufficient financial resources to consume existing solutions. Sometimes the place to look is in physical locations where consumption was historically difficult if not impossible. Finally, fringe markets like hackers or students can put up with the limitations that often characterize early versions of disruptive ideas.

As Ted Levitt pointed out 55 years ago, companies develop significant myopia over time, only seeing things that are squarely in the mainstream of their market. Disruptive innovation theory expands your view, increasing the odds that you spot important trends early.

Of course, the more places you look, the more things you see. No company has the capacity to respond to every trend they identify. That’s the second advantage that comes from using disruptive innovation theory: it helps you to separate the early-stage developments that have the highest potential to drive change from those that are likely to fizzle.

Does the upstart have a unique way that makes it easier and more affordable for target customers to get the innovation job done? Are they following a business model that looks unattractive to market leaders? One yes bears watching; two yeses is a standup moment. For example, in the late 1990s Netflix introduced its subscription model, which let consumers rent DVDs without worrying about late fees. Market leaders such as Blockbuster earned substantial profits from late fees, and used those fees as a way to drive customers to return hot movies quickly and therefore guarantee their availability. The rest, of course, is history.

September 3, 2015

Leading a Digital Transformation? Learn to Code

Leaders ascend to their positions by mastering today’s (or even yesterday’s) business. Almost by definition, they don’t have first-hand experience with a disruptive shift in their market when they encounter it. A lack of intuition around the new and different can at best slow progress and at worst lead to serious strategic missteps.

What should a leader do? Dave Gledhill decided to learn to code.

Gledhill is Group Executive and Head of Group Technology & Operations at DBS Bank, a leading Asian bank with more than $300 billion of assets and a market capitalization of about $35 billion. Over the past few years, its CEO, Piyush Gupta, has been pushing an aggressive transformation agenda, with a specific focus on embracing digital technologies.

The smartphone is obviously an important emerging area for any bank going digital, and DBS has aggressively explored mobile-only banking offerings in markets like India. While Gledhill is a “fourth-generation” engineer with a degree in computing and electronics, his formal education was decades ago, well before the rise of smartphones and related apps.

“My coding days were 20 years ago, and none of this stuff existed then,” Gledhill said. “I was struggling to understand at a deep level what was happening inside the phone, which made it hard to function as a leader of technology.”

So Gledhill committed himself to develop an app. An evening event provided the inspiration. In Singapore, every car is required to have a reader with a smartcard that interacts with the city-state’s smart toll system and almost every parking garage. One time Gledhill found himself at an event where the host provided complimentary parking. Unfortunately, Gledhill forgot to remove his smartcard from his car, so the complimentary parking was rendered moot.

What if, Gledhill wondered, he could create an app that provided location-based alerts, which reminded you to do a certain thing only when you were in a certain location?

Read the rest at Harvard Business Review.

Scott D. Anthony is the managing partner of Innosight.

August 18, 2015

Five Trends of the Future Consumer

Last week I had the pleasure of attending Copenhagen Institute for Future Studies’ Summer University, “The Future Consumer and Marketplace[1].” CIFS is an international, apolitical, and not-for-profit organization that is one of Scandinavia’s largest Future Studies think tanks. Founded in 1970 by Thorkil Kristensen, a former OECD Secretary-General and Danish Finance Minister, the Institute is now an international and interdisciplinary organization that seeks to create change, progress, and innovation informed by research.

The opportunity presented a pleasant change from standard (at least for me) US-centric views of the future and, coupled with a small group setting (5 people!), produced an experience that was eye-opening. Following are five of the more thought-provoking topics discussed:

From a Hierarchy of Needs to an Array: Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs has stood the test of time. Until now. In the Western world, consumers are able to settle all levels of Maslow’s hierarchy to some basic degree, freeing them up to choose the level(s), or need(s), against which to focus their energies and resources to achieve a higher degree of fulfillment. For businesses, this results in a consumer landscape that appears more fragmented than ever as some people search for solutions to fulfill their social Jobs-to-be-done (problems or goals related to Belonging and Esteem/Respect) while others actively seek solutions to their emotional Jobs-to-be-done (problems or goals related to Self-Actualization and Transcendence).

Multi-Hyphenate Identities are the Final Nail in the Coffin of Segmentation: Despite a plethora of approaches – demographic, psychographic, lifestyle – no segmentation scheme has ever been perfect and companies are usually forced to settle for an approach that is actionable but inaccurate. But as demographics shift, the definition of “family” expands, and hybrid lifestyles become more common, we increasingly adopt “multi-hyphenate” identities that put us in segments that were once considered mutually exclusive (e.g. a divorced father with shared custody is a single man some weeks and a single father other weeks). For business, this creates a world where traditional segmentation ceases to be effective and increases the risk that messaging crosses into stereotypes that alienate the very consumers they are trying to reach.

Innovation should Focus on Jobs-based Solutions: As demands for the pace and magnitude of business growth increases, companies face greater pressure to drive awareness and adoption of their solutions. With the elimination of a key tool (segmentation) to drive the business, it is essential that companies design and deliver solutions that are so laser-focused in their purpose that they draw customers to them and sell themselves. At Innosight, we call these Jobs-based solutions – products or services that help customers solve a problem or achieve a goal so well that they are an obvious choice versus competing solutions.

60 is 30 with Money: In 1950 people experienced three phases of life – childhood, adulthood, and old age[2]. As time went on and more people began going to college, waiting to marry and start families, and living longer, three phases became six – dependent children (minors living at home), dependent adults (people 18+ who remain partly or completely financially dependent on their parents), freedom 1 (financially independent adults), parents, freedom 2 (empty nesters) and old age (80+). Most interesting, and important for businesses, is the emergence of the Freedom 2 life stage which mirrors Freedom 1 in terms of spending levels and focus. For example, Danish couples 60+ years old spend more on wine, travel (e.g., tours, hotels, campsites), and experiences (e.g. restaurants, theater, concerts, museums) than any other household type, including Freedom 1 households.

Time is the New Luxury: Western consumers are richer in terms of money and material resources than ever before and, enabled by technology, able to do more with less. Yet most feel busier than ever and the quest to juggle work and family leaves less and less room for “time off” (e.g. vacations, relaxation, hobbies). This shift – from material objects as scarce resources from which pleasure or indulgence is derived to “time off” as a scarce resource – is making free time the ultimate luxury good. This is evident by the overall increase in consumer focus on immaterial features and solutions like design, stories, values, and experiences which require time to be enjoyed and a decrease in the demand to own and collect things once considered luxury items like cars, designer goods, and even homes.

[1.] The Future Consumer and Marketplace – 2015 Summer University

Clayton M. Christensen's Blog

- Clayton M. Christensen's profile

- 2168 followers