Michelle Higgs's Blog, page 5

April 28, 2014

THE LOST STORY OF THE VICTORIAN TITANIC

Today, I'm very happy to be hosting a guest post from Gill Hoffs, author of The Sinking of RMS Tayleur: The Lost Story of the Victorian Titanic. Her fascinating book tells the tragic story of the passengers and crew who lost their lives when RMS Tayleur struck rocks off Ireland and sank. Here, she explains the controversy behind the tragedy:

<!--[if gte mso 9]>

<!--[if gte mso 9]>

Published on April 28, 2014 07:13

April 22, 2014

HISTORY CARNIVAL - 1 MAY

I'm hosting the next History Carnival on 1 May here at http://visitvictorianengland.blogspot.com

If you know of any interesting and insightful history blog posts that I could include, please nominate them here: http://historycarnival.org/form.html . I'm looking for lots of variety so all historical periods will be considered!

If you know of any interesting and insightful history blog posts that I could include, please nominate them here: http://historycarnival.org/form.html . I'm looking for lots of variety so all historical periods will be considered!

Published on April 22, 2014 03:08

April 8, 2014

VICTORIAN CHILDREN - STREET SWEEPERS AND SHOE-BLACKS

Today, I'm delighted to be hosting a guest post from Sue Wilkes. Her latest book, Tracing Your Ancestors' Childhood, delves into the experiences of childhood at home, school, work and in institutions, especially during Victorian times.

Sue has very kindly written a post about the child shoe-blacks who were on every busy street in Victorian cities, eager to shine shoes for a fee.

<!--[if gte mso 9]>

Sue has very kindly written a post about the child shoe-blacks who were on every busy street in Victorian cities, eager to shine shoes for a fee.

<!--[if gte mso 9]>

Published on April 08, 2014 02:11

April 1, 2014

THE VICTORIAN WORKHOUSE: THE LAST RESORT

I've been interested in workhouses since my university days so if I could take a trip to Victorian England, a workhouse would be on my list of places to visit. The visitors' books of these institutions show that they were regularly visited by people like journalists, local worthies, guardians from the Board and ladies connected with charities, as well as official inspectors.

There's a common misconception that all Victorian workhouses were dark, depressing places in which the poor were...

There's a common misconception that all Victorian workhouses were dark, depressing places in which the poor were...

Published on April 01, 2014 01:45

March 18, 2014

A VISITOR'S GUIDE TO VICTORIAN MANCHESTER

Today, I'm delighted to be hosting a guest post from Angela Buckley as part of her blog tour to promote her wonderful new book, The Real Sherlock Holmes: The Hidden Story of Jerome Caminada. It's selling like hot-cakes!

Caminada's groundbreaking detective work led to the unravelling of classic crime cases such as the Hackney Carriage Murder in 1889, secret government missions and a deadly confrontation with his arch-rival, a ruthless and violent thief. Angela has very kindly written a po...

Caminada's groundbreaking detective work led to the unravelling of classic crime cases such as the Hackney Carriage Murder in 1889, secret government missions and a deadly confrontation with his arch-rival, a ruthless and violent thief. Angela has very kindly written a po...

Published on March 18, 2014 02:31

March 4, 2014

VICTORIAN PUBLIC TRANSPORT - THE OMNIBUS

Typical photographs of Victorian street scenes feature a multitude of horse-drawn vehicles all mixed in together, but the preferred public transport of the middle classes to commute to work or to go shopping was the omnibus (or 'bus for short). This was cheaper than travelling by cab. In Saunterings In and About London (1853), Max Schlesinger observed that "among the middle classes of London, the omnibus stands immediately after air, tea and flannel in the list of necessaries of life".

'An Omn...

'An Omn...

'An Omn...

'An Omn...

Published on March 04, 2014 02:48

February 13, 2014

VICTORIAN PUBLIC TRANSPORT - THE HANSOM CAB

If I was able to visit Victorian England, I know that one of the aspects which would fascinate me the most is the public transport. Aside from steam trains and the later electric trams, it was all horse-drawn which, of course, is so different from today's motor-driven vehicles. Horses pulled the omnibuses, carts, and brewers' drays through to the broughams, clarences and Hansom cabs. The sounds of hooves clattering on cobbles was everywhere, as was the smell of steaming horse manure...

To get...

To get...

Published on February 13, 2014 03:21

February 4, 2014

VICTORIAN HOSPITALS: THE OUT-PATIENTS' DEPARTMENT

In the UK, we often take the NHS for granted. Everyone, regardless of background or income, can receive medical or surgical treatment if they need it without having to worry about whether they can afford it.

Imagine, then, how different it was if you lived in Victorian England. Back then, it was your social class which determined the type of healthcare you could get. The wealthy upper classes paid for private medical treatment at home or, later in the nineteenth century, in a practitioner’s co...

Imagine, then, how different it was if you lived in Victorian England. Back then, it was your social class which determined the type of healthcare you could get. The wealthy upper classes paid for private medical treatment at home or, later in the nineteenth century, in a practitioner’s co...

Published on February 04, 2014 06:22

January 9, 2014

MAKING ENDS MEET - THE ROLE OF VICTORIAN PAWNBROKERS

Many of us will be feeling the pinch after the expenses associated with Christmas, and some will buy more things on credit cards to tide them over. But spare a thought for the Victorian working classes, paid at best on a weekly basis, and at worst, by the day. For them, the only way to make ends meet was to pledge domestic items at the local pawnbrokers to raise some cash for the week ahead. The possessions pledged could be as diverse as clothing, shoes and jewellery through to flat irons and occupational tools.

The pawnbroker’s customers were not those in abject poverty who had nothing of value to pledge, but those living close to the bread-line who were in regular, yet poorly paid work. For the majority of the working classes, pawning was simply a way of life. When in employment, they used their clothing, especially their Sunday best, as capital on which to raise cash. Clothing was often pledged on a Monday and redeemed on a Saturday after the breadwinner of the family had been paid. It was worn to chapel or church on a Sunday, and pledged again the next day. This was the reason that Saturdays and Mondays were the pawnbrokers' busiest days.

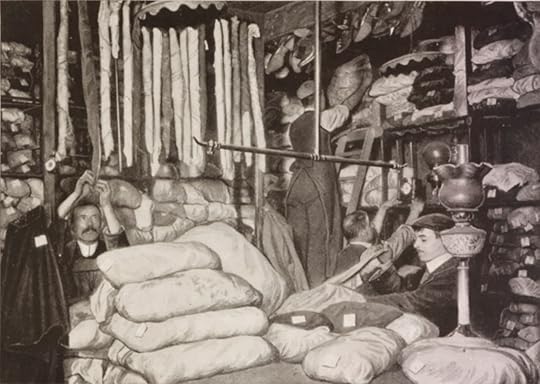

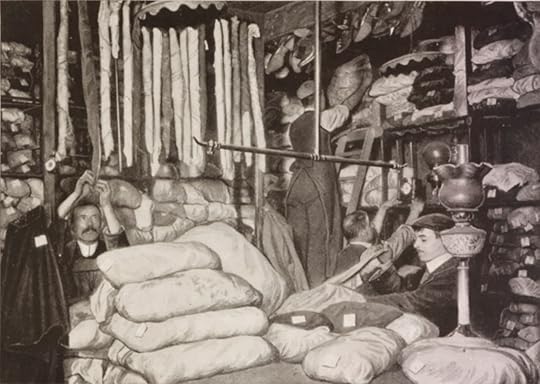

'The Weekly Pledge Room' from Living London (1901)

'The Weekly Pledge Room' from Living London (1901)

‘Uncle’, as the pawnbroker was colloquially known, could always be turned to in times of need. Pawnshops were an urban phenomenon, and with the rise in population throughout the Victorian period, the number of pawnbrokers increased dramatically. Some streets had more pawnbrokers than public houses.

Pawnbrokers did not benefit greatly when people could not afford to redeem their pledges. Their profit was made from the interest charged when regular customers pledged and redeemed their belongings. The pawnbroker was entitled to keep and sell unredeemed items pledged for less than ten shillings after the redemption period of one year and seven days. Unredeemed pledges of more than ten shillings did not automatically become his property; these items had to be sold at a public auction, although he could set a reserve to avoid making a loss.

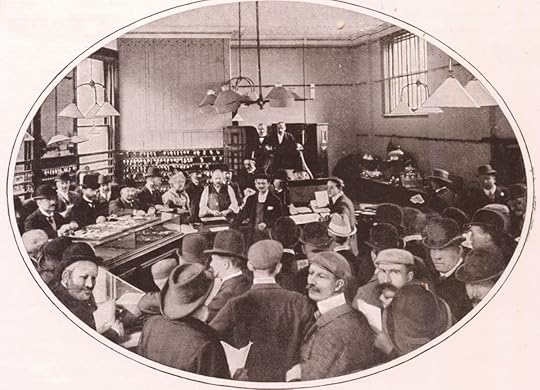

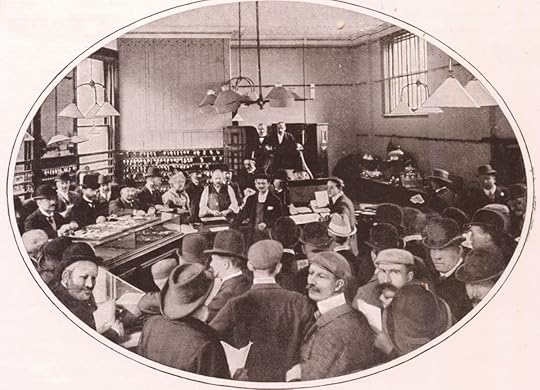

'Sale of Unredeemed Stock' from Living London (1901)

'Sale of Unredeemed Stock' from Living London (1901)

The entrance to a pawnbroker's shop was usually up a side street. Pledging could be done at an open counter or in separate compartments known as ‘boxes’, which offered some privacy to those ashamed of their predicament. The pawnbroker would carefully examine the item pledged, offer a sum and if accepted, he would give the pledger a pawn ticket. From 1872, for loans of ten shillings or less, the interest rate was one halfpenny per calendar month on each two shillings or part of two shillings lent. After the first calendar month, any time not exceeding fourteen days was to be reckoned as half a month only. The pawnbroker could also charge a halfpenny for the ticket, although for very small sums, he might waive this fee. Under the previous legislation, there was no charge for the ticket if the pledge was under five shillings.

On loans of between ten and forty shillings, a penny was charged for the ticket, and the interest was one halfpenny per two shillings per calendar month. Loans of more than forty shillings and less than ten pounds attracted interest of a halfpenny on every two and a half shillings per month, and a penny for the ticket. There was also an optional one penny fee for special storage, such as hanging boots and clothes to prevent creases.

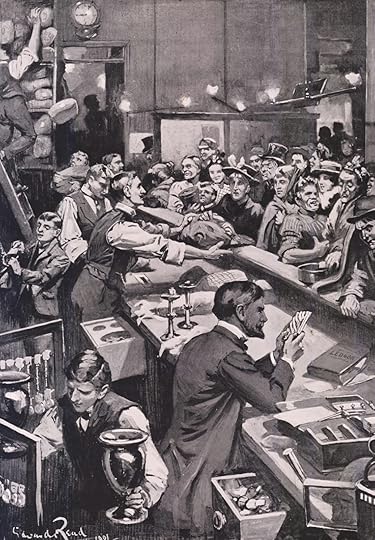

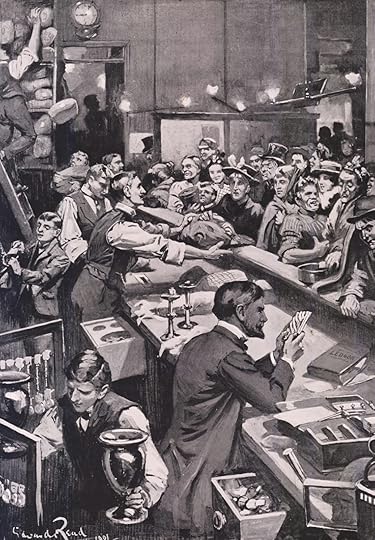

'Saturday Night at a Pawnbroker's' from Living London (1901)

'Saturday Night at a Pawnbroker's' from Living London (1901)

The atmosphere of pawnshops on redemption days, usually Saturdays, was extremely noisy with hundreds of people redeeming their belongings. ‘Pawnbroking London’ in Living London (1901) described one such day: “It is a strangely animated scene, with nearly all the characters played by women. It is a rarity to see a man among them… They betray no sense of shame if they feel it. They talk and gossip while waiting for their bundles, and are wonderfully polite to the perspiring assistants behind the counter.” An average of 2,000 bundles were redeemed each Saturday at this particular shop.

Despite the high interest rates, pawnbrokers offered a vital service to the working classes. The writer of the article in Living London pointed out: “They mean food for the wife and children when cupboard and pocket are empty – a little money to keep things going till next pay-day; they mean to thousands shelter, warmth, and something to eat; and although many consider the pawnbroker’s shop an encouragement to improvidence and unthriftiness, every philanthropist who would abolish it admits that he would have to substitute some municipal or charitable pawnshop in its place.”

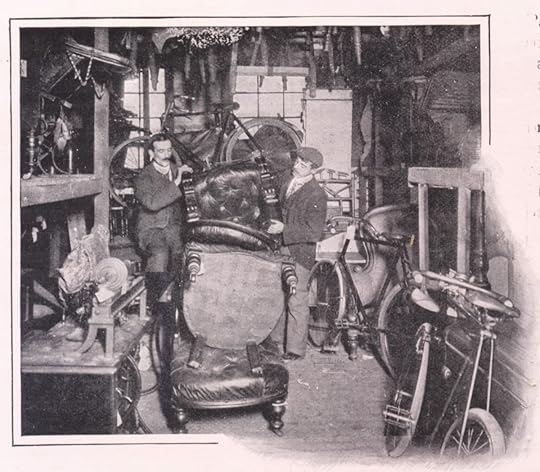

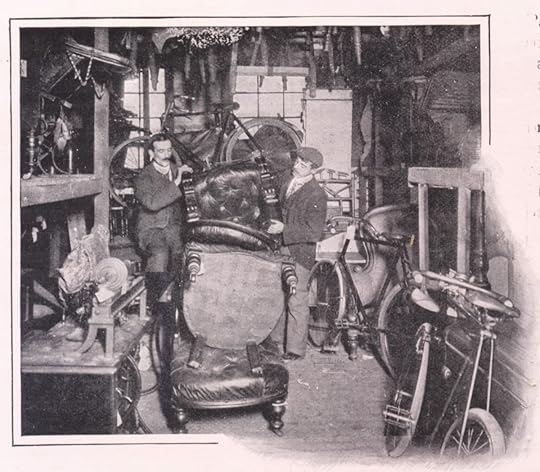

'Furniture in a Pawnbroker's Warehouse' from Living London (1901)

'Furniture in a Pawnbroker's Warehouse' from Living London (1901)

The pawnbroker’s customers were not those in abject poverty who had nothing of value to pledge, but those living close to the bread-line who were in regular, yet poorly paid work. For the majority of the working classes, pawning was simply a way of life. When in employment, they used their clothing, especially their Sunday best, as capital on which to raise cash. Clothing was often pledged on a Monday and redeemed on a Saturday after the breadwinner of the family had been paid. It was worn to chapel or church on a Sunday, and pledged again the next day. This was the reason that Saturdays and Mondays were the pawnbrokers' busiest days.

'The Weekly Pledge Room' from Living London (1901)

'The Weekly Pledge Room' from Living London (1901)‘Uncle’, as the pawnbroker was colloquially known, could always be turned to in times of need. Pawnshops were an urban phenomenon, and with the rise in population throughout the Victorian period, the number of pawnbrokers increased dramatically. Some streets had more pawnbrokers than public houses.

Pawnbrokers did not benefit greatly when people could not afford to redeem their pledges. Their profit was made from the interest charged when regular customers pledged and redeemed their belongings. The pawnbroker was entitled to keep and sell unredeemed items pledged for less than ten shillings after the redemption period of one year and seven days. Unredeemed pledges of more than ten shillings did not automatically become his property; these items had to be sold at a public auction, although he could set a reserve to avoid making a loss.

'Sale of Unredeemed Stock' from Living London (1901)

'Sale of Unredeemed Stock' from Living London (1901)The entrance to a pawnbroker's shop was usually up a side street. Pledging could be done at an open counter or in separate compartments known as ‘boxes’, which offered some privacy to those ashamed of their predicament. The pawnbroker would carefully examine the item pledged, offer a sum and if accepted, he would give the pledger a pawn ticket. From 1872, for loans of ten shillings or less, the interest rate was one halfpenny per calendar month on each two shillings or part of two shillings lent. After the first calendar month, any time not exceeding fourteen days was to be reckoned as half a month only. The pawnbroker could also charge a halfpenny for the ticket, although for very small sums, he might waive this fee. Under the previous legislation, there was no charge for the ticket if the pledge was under five shillings.

On loans of between ten and forty shillings, a penny was charged for the ticket, and the interest was one halfpenny per two shillings per calendar month. Loans of more than forty shillings and less than ten pounds attracted interest of a halfpenny on every two and a half shillings per month, and a penny for the ticket. There was also an optional one penny fee for special storage, such as hanging boots and clothes to prevent creases.

'Saturday Night at a Pawnbroker's' from Living London (1901)

'Saturday Night at a Pawnbroker's' from Living London (1901)The atmosphere of pawnshops on redemption days, usually Saturdays, was extremely noisy with hundreds of people redeeming their belongings. ‘Pawnbroking London’ in Living London (1901) described one such day: “It is a strangely animated scene, with nearly all the characters played by women. It is a rarity to see a man among them… They betray no sense of shame if they feel it. They talk and gossip while waiting for their bundles, and are wonderfully polite to the perspiring assistants behind the counter.” An average of 2,000 bundles were redeemed each Saturday at this particular shop.

Despite the high interest rates, pawnbrokers offered a vital service to the working classes. The writer of the article in Living London pointed out: “They mean food for the wife and children when cupboard and pocket are empty – a little money to keep things going till next pay-day; they mean to thousands shelter, warmth, and something to eat; and although many consider the pawnbroker’s shop an encouragement to improvidence and unthriftiness, every philanthropist who would abolish it admits that he would have to substitute some municipal or charitable pawnshop in its place.”

'Furniture in a Pawnbroker's Warehouse' from Living London (1901)

'Furniture in a Pawnbroker's Warehouse' from Living London (1901)

Published on January 09, 2014 03:23

December 20, 2013

VICTORIAN CHRISTMAS - ACCORDING TO PUNCH 1884

Here's a short and sweet post for Christmas. We all know that many of the Christmas traditions we keep today, such as the Christmas tree, pulling crackers and sending Christmas cards, originated in the Victorian era. But did you also know that even back in the 19th century, newspapers and magazines were stuffed full with unoriginal, hackneyed articles at this time of year?

Paper lace card, 1860s. Copyright Michelle Higgs

Paper lace card, 1860s. Copyright Michelle Higgs

In January 1884, Punch alluded to this in a piece entitled Unhackneyed Yule; Or, Yule-tide Gush. The writer devised a 'New Game for Journalists' to produce 'a novel and really readable column of printed matter for next Christmas'. The rules were:

"1. No allusions whatever to be made to DICKENS's Christmas Chimes, to WASHINGTON IRVING's Old Christmas, or to the Grave-digger who punched the little boy's head for whistling on Christmas Day.

2. Anybody who uses the words 'Yule-tide' or 'Yule-log' is immediately out of the game.

3. No references permitted to the Druids, or the Roman Saturnalia.

4. No paragraphs to begin with "A Merry Christmas! And why not a Merry Christmas? Is it not far better to be merry than to be &c. &c.?" or with "To-day the bells from many a tower and steeple ring in the season of Good-will, of Merriment, of, &c. &c."

5. Nobody to mention plum-pudding. Turkeys only to be used with a good deal of fresh stuffing.

6. Any words expressive of the slightest tolerance for "Waits" subject the Player to a heavy forfeit.

7. Players to take for granted that the public is already acquainted with the uses of Holly and Mistletoe as decorative agents, and these, therefore, are not to be mentioned at all.

8. No Scandinavian 'lore' about Mistletoe to be trotted out on any pretence.

9. Feelings of gushing benevolence to the poor (on paper) to be sternly repressed.

10. Articles to be as short as possible.

11. If possible, no articles at all to be written."

This is my last blog of the year so Yuletide greetings to one and all - oops, I'm out of the game! Happy Christmas everyone!

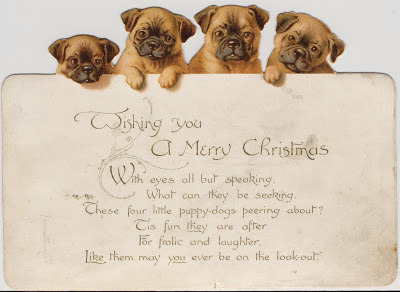

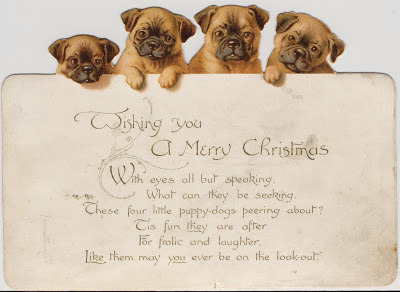

Pug dogs card, 1880s. Copyright Michelle Higgs

Pug dogs card, 1880s. Copyright Michelle Higgs

Paper lace card, 1860s. Copyright Michelle Higgs

Paper lace card, 1860s. Copyright Michelle HiggsIn January 1884, Punch alluded to this in a piece entitled Unhackneyed Yule; Or, Yule-tide Gush. The writer devised a 'New Game for Journalists' to produce 'a novel and really readable column of printed matter for next Christmas'. The rules were:

"1. No allusions whatever to be made to DICKENS's Christmas Chimes, to WASHINGTON IRVING's Old Christmas, or to the Grave-digger who punched the little boy's head for whistling on Christmas Day.

2. Anybody who uses the words 'Yule-tide' or 'Yule-log' is immediately out of the game.

3. No references permitted to the Druids, or the Roman Saturnalia.

4. No paragraphs to begin with "A Merry Christmas! And why not a Merry Christmas? Is it not far better to be merry than to be &c. &c.?" or with "To-day the bells from many a tower and steeple ring in the season of Good-will, of Merriment, of, &c. &c."

5. Nobody to mention plum-pudding. Turkeys only to be used with a good deal of fresh stuffing.

6. Any words expressive of the slightest tolerance for "Waits" subject the Player to a heavy forfeit.

7. Players to take for granted that the public is already acquainted with the uses of Holly and Mistletoe as decorative agents, and these, therefore, are not to be mentioned at all.

8. No Scandinavian 'lore' about Mistletoe to be trotted out on any pretence.

9. Feelings of gushing benevolence to the poor (on paper) to be sternly repressed.

10. Articles to be as short as possible.

11. If possible, no articles at all to be written."

This is my last blog of the year so Yuletide greetings to one and all - oops, I'm out of the game! Happy Christmas everyone!

Pug dogs card, 1880s. Copyright Michelle Higgs

Pug dogs card, 1880s. Copyright Michelle Higgs

Published on December 20, 2013 02:57