Simon Ings's Blog, page 50

May 25, 2012

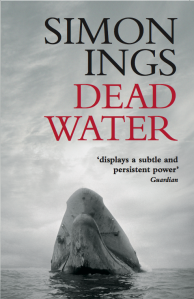

Launch day!

Please, for the love of Christ, buy it here.

And let’s hope it has better luck than the ship on the cover.

May 17, 2012

Dead Water paperback released 25 May

This is modern science fiction in full pomp: it has a multitude of ideas, a wide-ranging narrative, an almost unbelievably ambitious casting of its net, taking one narrative chance after another. It is also a beautifully written novel, full of colour and inventive image.

—Christopher Priest

http://tomscott.com

May 8, 2012

Healthify yourself!

Come along on Wednesday 16 May at 7pm to the last of my talks at Pushkin House; I'm exploring Russia's unsung sciences of the mind.

The way we teach and care for our children owes much to a handful of largely forgotten Russian pioneers. Years after their deaths, the psychoanalyst Sabina Spielrein, the psychologist Lev Vygotsky and the pioneering neuroscientist Alexander Luria have an unseen influence over our everyday thinking. In our factories and offices, too, Soviet psychology plays a role, fitting us to our tasks, ensuring our safety and our health. Our assumptions about health care and the role of the state all owe a huge debt to the Soviet example.

Tickets: £7, conc. £5 (Friends of Pushkin House, students and OAPs)

May 4, 2012

Healthify yourself!

Come along on Wednesday 16 May at 7pm to the last of my talks at Pushkin House; I’m exploring Russia’s unsung sciences of the mind.

[image error]

The way we teach and care for our children owes much to a handful of largely forgotten Russian pioneers. Years after their deaths, the psychoanalyst Sabina Spielrein, the psychologist Lev Vygotsky and the pioneering neuroscientist Alexander Luria have an unseen influence over our everyday thinking. In our factories and offices, too, Soviet psychology plays a role, fitting us to our tasks, ensuring our safety and our health. Our assumptions about health care and the role of the state all owe a huge debt to the Soviet example.

Tickets: £7, conc. £5 (Friends of Pushkin House, students and OAPs)

Start the Week explores the digital future

Listen on Monday morning to Radio 4: you’ll find the wild and wonderful writer Nick Harkaway, design guru Anab Jain, business expert Charles Arthur and myself discussing the digital future with Andrew Marr.

Arc, New Scientist’s new digital quarterly of futures and science fiction, regularly darkens the hand towels at Anab’s outfit Superflux as we prepare a year of events, interventions, pop-up surprises and generally making things up. Nick Harkaway, on the other hand – well, you’ll have to wait till Monday to find out what we’re up to with him. Even Charles Arthur is formerly of the New Scientist (and the Independent, during Andrew Marr’s stint there in the late 1990s).

I think some of this lack-of-separation set alarm bells ringing somewhere because the show’s producer rang us all beforehand telling us not to be nice to each other. (Face to face, it’s the obvious thing to do; on air, it’s an excruciating waste of the listener’s time.)

This got me thinking about how we behave on different media. Susan Greenfield’s belief that we’re all going to hell in a handcart because of our love of new media has become the stuff of parody and legend; still, she’s on to something. We learn to behave differently as we engage through different media; we develop new responses, new forms of interaction – even new ethical codes. Not all of these have to be pretty.

It’s a stalwart reader – or an obtuse one – who takes much comfort from Charles Arthur’s new book Digital Wars: Apple, Google, Microsoft and the Battle for the Internet. The pace at which the digital economy is deskilling the workforce is breathtaking: the very idea of “digital commerce” is being called into question as the number of serious players on the web falls toward single figures. The internet doesn’t like democracy. The internet doesn’t want to be free. The internet wants to be a vertical monopoly. It wants to be Hollywood, circa 1930. Or, just possibly, something worse.

Nick Harkaway thinks we can still harness this grinning Stalinist golem to our own humble, human needs. The Blind Giant: Being Human in a Digital World is his attempt to resuscitate the idea of the internet as a civic space. Myself, I think the tide is against him, but he makes a hell of a splash.

Anab is a designer, entrepreneur, TED Fellow and founder of Superflux, a multidisciplinary design company. (I guess you need a CV of that sort if you want to be profiled in both Popular Science and Marie Claire.) It’s Superflux’s job to realise ideas about the future in props, videos, stories and working models. Superflux designs everything from mechanical bees to prosthetic vision systems for the blind, seeing these concepts through from drawing board to real-world trials. Anab is upfront about the fact that her work is provocative. It might not be a great idea to let the world’s bee population go hang and rely instead on synthetic pollinators. “But the technology that could allow this is waiting to happen. If we don’t create these experience prototypes and stories, it’s difficult for us to fully interrogate the technology before it’s out in the world.”

I don’t think it’s any accident that, as we try to imagine our digital future, we reach, not just for stories, not just for opinions, but also for props, for things we can handle; for toys, basically. “Futurism” is a very serious-sounding idea; yet 99 per cent of the job is – has to be – play.

Start the Week explores the digital future

Listen on Monday morning to Radio 4: you’ll find the wild and wonderful writer Nick Harkaway, design guru Anab Jain, business expert Charles Arthur and myself discussing the digital future with Andrew Marr.

Arc, New Scientist's new digital quarterly of futures and science fiction, regularly darkens the hand towels at Anab’s outfit Superflux as we prepare a year of events, interventions, pop-up surprises and generally making things up. Nick Harkaway, on the other hand – well, you’ll have to wait till Monday to find out what we’re up to with him. Even Charles Arthur is formerly of the New Scientist (and the Independent, during Andrew Marr’s stint there in the late 1990s). I think some of this lack-of-separation set alarm bells ringing somewhere because the show’s producer rang us all beforehand telling us not to be nice to each other. (Face to face, it’s the obvious thing to do; on air, it’s an excruciating waste of the listener’s time.) This got me thinking about how we behave on different media. Susan Greenfield’s belief that we’re all going to hell in a handcart because of our love of new media has become the stuff of parody and legend; still, she’s on to something. We learn to behave differently as we engage through different media; we develop new responses, new forms of interaction – even new ethical codes. Not all of these have to be pretty.It’s a stalwart reader – or an obtuse one – who takes much comfort from Charles Arthur’s new book Digital Wars: Apple, Google, Microsoft and the Battle for the Internet. The pace at which the digital economy is deskilling the workforce is breathtaking: the very idea of “digital commerce” is being called into question as the number of serious players on the web falls toward single figures. The internet doesn’t like democracy. The internet doesn’t want to be free. The internet wants to be a vertical monopoly. It wants to be Hollywood, circa 1930. Or, just possibly, something worse.Nick Harkaway thinks we can still harness this grinning Stalinist golem to our own humble, human needs. The Blind Giant: Being Human in a Digital World is his attempt to resuscitate the idea of the internet as a civic space. Myself, I think the tide is against him, but he makes a hell of a splash.Anab is a designer, entrepreneur, TED Fellow and founder of Superflux, a multidisciplinary design company. (I guess you need a CV of that sort if you want to be profiled in both Popular Science and Marie Claire.) It’s Superflux’s job to realise ideas about the future in props, videos, stories and working models. Superflux designs everything from mechanical bees to prosthetic vision systems for the blind, seeing these concepts through from drawing board to real-world trials. Anab is upfront about the fact that her work is provocative. It might not be a great idea to let the world’s bee population go hang and rely instead on synthetic pollinators. “But the technology that could allow this is waiting to happen. If we don’t create these experience prototypes and stories, it’s difficult for us to fully interrogate the technology before it’s out in the world.”I don’t think it’s any accident that, as we try to imagine our digital future, we reach, not just for stories, not just for opinions, but also for props, for things we can handle; for toys, basically. “Futurism” is a very serious-sounding idea; yet 99 per cent of the job is – has to be – play.April 8, 2012

The Method by Juli Zeh

Illness is an obscenity, and failure to take all reasonable precautions against disease is a crime.

The joy of research

April 6, 2012

Phantom Menaces

written for the Arcfinity blog:

Google's swooshy new concept video for augmented reality goggles (or "spex", if you will) has certainly put the virtual cat among the digital pigeons. An attempt, perhaps, to leapfrog the iPad – if Google can persuade us that what we really want is headwear that will let us see things that aren't really there.I recently spent an entire evening doing just that. Aurasma, a start-up spun out of Autonomy (another search giant, incidentally), aims to bring AR to the masses;

that evening, its glamorous representatives pasted digital magic over a south London gallery's functional white-and-grey surfaces.

Rice packets came to life in our hands to show us how to cook rice. Books spilled their letters into our laps; they took wing and flocked about our heads like so many starlings. Avatars swung their swords blindly about the gallery.

AR is one of a handful of technologies that are likely to transform our lives in the very near future. And I don't use the 'T' word lightly. People talk about the great things AR can show you. Every wall becomes a picture! Every picture becomes a movie! Every object becomes something other, something better than itself – or seems to. Oddly nobody talks about AR's ability to hide things. And since I'd been invited along in the role of Ancient Mariner (stopping one of three with tales of future horror - I am a writer after all; this is my job) it was this ability to subtract from the visual richness of the real which interested me the most. Never mind the avatars and the rice-packets: these are distractions, no different in kind to movies, posters, fiercely rung handbells, and all the other manifold calls to our attention. Let's get back to basics here. What does it mean to look at the world through a screen?The granularity of the world is always going to be finer than the granularity of the medium through which we perceive it. No matter how photorealistic AR gets, it will always be taking information out of the picture plane. So AR has the potential to render the world down to a kind of tedious photographic grammar - the kind employed by commercial image libraries, whose job it is to reduce the world to a series of unambiguous stills illustrating stock ideas like 'busy at work' or 'looking after the children'. This is nothing new. Photography has the ability to do this, obviously. But photography cannot be stuck over (or in) your eyeballs twenty-four hours a day. AR has this potential, substituting the real with a simplified description for anyone wearing the funny glasses. Lacanian psychoanalysts have a word for this process of simplification: they call it repression. And if AR becomes truly ubiquitous, then we will no longer be able to trust our eyes, and will probably have to develop a neurotic relationship with this technology. Is AR a good thing, then, or a bad thing? This is the kind of question we're trying to avoid in Arc. Not because it is a hard question, but because it is a bad question. It assumes we have no agency, no wit, no common sense. It assumes we're at the mercy of our own technology.The problems thrown up by AR will not be new. They will be old. They will be fairytale-like problems. (Is that woman by the bar a fairy, a queen, or a crone? Is the wizard touting for trade in the shopping centre a wizard at all, or a mere trickster? Is our Prime Minister really wearing any clothes?) It may be that, in order to navigate this fairytale visual space, AR will give birth to an entirely new set of visual behaviours. It wouldn't be the first time. Look at reading. There is nothing 'natural' - certainly nothing evolved - about it. But we welcome its effects, and we build upon them, and we celebrate them. In some ways reading makes us less -it's been shooting human memory in the foot repeatedly since Plato's day. In other ways it makes us more: itallows us to share the knowledge and experiences of people we will never meet, of people who have ceased to exist, of people who never existed. AR will do the same.

Simon Ings's Blog

- Simon Ings's profile

- 147 followers