Simon Ings's Blog, page 40

October 2, 2017

A kind of “symbol knitting”

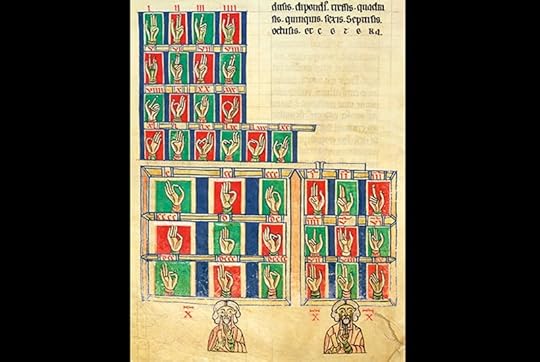

Mathematics began when practical thinkers like Archimedes decided to ignore naysayers like Zeno (whose paradoxes were meant to bury mathematics, not to praise it) and deal with nonsenses like pi and the square root of 1. How do such monstrosities yield such sensible results? Because mathematics is magical. Deal with it.

Reviewing new books by Paul Lockhart and Ian Stewart for The Spectator

September 21, 2017

This way lies madness

Hellblade is more than a journey through a hallucinatory landscape (and hallucinatory it is, passing from flaming killing fields through sun-kissed meadows to a corridor of withered arms). It’s about a rational hero desperately trying to make sense of her world. “Most of us are pretty bad at that,” Fletcher points out.

Playing Hellblade for New Scientist, 29 August 2017

September 16, 2017

Death comes to Lithuania

On Saturday 30 September 2017 I’ll be heading to Vilnius to join Vernor Vinge and Yoon-Ha Lee as guest of honour at Lituanicon, the Lithuanian science fiction and fantasy fan convention.

This will be my first opportunity to trot out some of my recent research into ageing and death. There may also be sightseeing.

August 17, 2017

I know why the caged bird sings, so nuts to you

Prince Hamlet of Denmark is out to revenge his father – at least, that’s the idea. But William Shakespeare has saddled him with a girlfriend, Ophelia, and her father Polonius, an interfering old fool. A Pantalone, in other words: a man (by tradition, but the gender’s immaterial) who is losing his grip on affairs of which he was once the master. With age, the Pantalone’s sphere of action and influence becomes comically reduced. What was once a voice of authority has become a bark of comic impotence.

I’m at the Harold Pinter Theatre in London. Andrew Scott (Moriarty in Steven Moffat’s Sherlock) is playing the prince, but it’s Polonius has me fascinated. The British character actor Peter Wight isn’t playing him for a fool, but as someone suffering from mid-stage Alzheimer’s. His mood swings wildly about, his silences are painful, his recollections pathetic victories snatched against the coming dark.

Wight’s portrayal is meticulous, sincere, and timely. Old age may not be a disease but it’s certainly a genetic condition, and one by one, elements of that condition are succumbing to medical research. This has had the disconcerting effect of curing all the easy diseases in order that we may bankrupt ourselves treating the recalcitrant ones. Rates of terminal cancer have plummeted, only to expose us to Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s.

It looks like we’re all going to live to 100 before we drop dead. This pleases me, because I want to become the character described by the Athenian lawyer Solon 2,600 years ago: “so wise that he no longer wastes time on useless things, and this enables him to formulate his profoundest insights most succinctly.”

The trouble is that only a couple of hundred years after Solon, Aristotle came up with this charming formula: the old, he said, live by memory rather than by hope. Sure they have a lot of experience, but this means they are sure about nothing and under-do everything. They are small-minded because they have been humbled by life. As a result, they are driven too much by the useful and not enough by the noble. They are cynical and distrustful and neither love warmly nor hate bitterly. They are not shy. On the contrary, they’re shameless, feeling only contempt for people’s opinion of them.

Aristotle knew what a pantalone was, and he knew that being a pantalone was nothing to do with disease or infirmity. It was, and is, to do with the passing of time.

By the time I’m a hale and hearty 100, what kind of monster will I have become? Always voting the way I’ve voted; always writing the same kind of novel about the same kind of people using the same kind of dialogue; always dating the same kinds of people and always messing them up in the same sorts of ways; bringing up the same kinds of children and saddling them with the same hang-ups.

Would I want to live for ever? Probably. I just wouldn’t want to remain human forever. I don’t want to be “better than human” or “superhuman” or any of that rubbish (what does that even mean?) What I want is simple and, thanks to the passage of time, quite impossible. I want to be not bored. I want to be not burdened by experience. I want to be unfazed by life.

I realise now that I don’t know nearly enough about how other animals think. I need to read more Sy Montgomery. I need to read Marc Bekoff and John Bradshaw. I need to know what my options are, just in case the triumphant effort to healthify old age tips suddenly towards affording us everlasting life.

My best bet right now is the cockatoo. If you treat a cockatoo properly, it’ll stay a three-year-old child forever – and that’s a long time: cockatoos live into their sixties.

Don’t let me be a pompous ass, a fussy, fond old fool. Don’t make me a gull, a mark, a slippered pantalone. Let me become something else, something less than human if needs be, but better adapted to forever.

Who’s a pretty boy then?

I am

July 7, 2017

Listening to DX17

Here and there, two beams intersect, and through your headphones, two audio samples blend. As you step away from a light source, the voice in your headphones – an airman’s memoir, instructions to ground staff, a loved one’s letter, a child’s recollections – slowly fade.

It wasn’t until they were testing their system that Malikides came across the pre-history of this “li-fi” tech. Alexander Graham Bell invented it, using sunlight and a deformable mirror to send sound information across space.

Visiting IWM Duxford for New Scientist, 5 July 2017. The artist Nick Ryan showed me round his new sound sculpture, DX17.

July 3, 2017

Skin-shuddering intimacy

The rule used to be that if you wanted to study something you went out and shot it: the rifle was as much part of your kit as your magnifying glass. The Maoris of Polynesia, aware of the value Western visitors put on souvenirs, used to catch people, tattoo their faces, decapitate them and sell their heads to collectors. The draughtsman aboard Charles Darwin’s ship the Beagle had a travel box lined with the tattooed skin of dead Maori warriors.

Visiting Tattoo: British Tattoo Art Revealed, National Maritime Museum, Falmouth for New Scientist, 1 July 2017

June 20, 2017

The physics of dance

“Something about your grip here is stopping her moving,” frets the choreographer. “Can we get his hips to go the other way?”

Visiting a rehearsal of 8 Minutes, Alexander Whitley’s Sadler’s Wells main-stage debut, for New Scientist, 17 June 2017

June 10, 2017

Hello, Robot

Above the exhibits in the first room of Hello, Robot, a large sign asks: “Have you ever met a robot?” Easy enough. But the questions keep on coming, and by the end of the exhibition, we’re definitely not in Kansas any more: “Do you believe in the death and rebirth of things?”; “Do you want to become better than nature intended?”

Visiting a stand-out touring exhibition for New Scientist , 6 June 2017

The dreams our stuff is made of

Science fiction enters clad in the motley of costume drama: polished, chromed, complete, not infrequently camp. But there’s always a twist, a tear, a weak seam. This genre takes finery from the prop shop and turns it into something vital – a god, a golem, a puzzle, a prison. In science fiction, it matters where you are and how you dress, what you walk on and even what you breathe. All this stuff is contingent, you see. It slips about. It bites.

To introduce a New Scientist speaking event at London’s Barbican centre on 29 June, I took a moment to wonder why the present looks so futuristic.

At London’s Excel: post-truth science

At 1.30pm on Thursday 28 September, I’ll be bringing Stalin and his scientists to New Scientist Live at the Excel in London. Further details here.

Simon Ings's Blog

- Simon Ings's profile

- 147 followers