Simon Ings's Blog, page 39

January 20, 2018

Music and art stop dementia from stealing everything we cherish

According to Greek legend, 49 of King Danaus’s 50 daughters were mariticidal, and condemned to fill a leaky bath in hell, and their lot is an apt metaphor for the human condition. However much we fill our lives, our lives still dribble away. We experience, we learn – but we also forget.

A choir and a De Kooning show inspired this piece for New Scientist, 4 January 2018

December 20, 2017

Just experience it

According to the curators, these exquisite allegorical frescoes by 18th-century artist Johann Wenzel Bergl are “recognizable as strategies of absolutist picture propaganda”. And Mark Dion’s installation capturing “the lifestyle and self-image of the prototypical ethnographer of colonial times”, isn’t even that, but alludes “to our own imagination of that ethnographer”. I left feeling rather as Lewis Carroll’s Alice might have felt if, instead of freely stepping through the mirror, she had been shoved through it from behind by a gang of goonish anthropologists.

Visiting mumok, Vienna’s museum of contemporary art, for New Scientist, 23 December 2017

Technology vs observation

Things break down when the press turns up – you might even say it’s a rule. Still, given their ubiquity, I’m beginning to wonder whether gallery-based VR malfunctions are not a kind of mischievous artwork in their own right. In place of a virtual sketch, a message in an over-friendly font asks: “Have you checked your internet connection?” At least Swiss artist Jean Tinguely’s wild mobiles of the 1960s had the decency to catch fire.

Losing my rag at the Royal Academy for New Scientist, 13 December 2017

It’s coming at you!

Outside Dimension Studios in Wimbledon, south London, is one of those tiny wood-framed snack bars that served commercial travellers in the days before motorways. The hut is guarded by old shop dummies dressed in fishnet tights and pirate hats. If the UK made its own dilapidated version of Westworld, the cyborg rebellion would surely begin here.

Playing with volumetric video for New Scientist, 16 December 2017

November 29, 2017

Future by design

Carpo’s future has us return to a tradition of orality and gesture, where these forms of communication will need no reduction or compression. Our machines will be able to record, notate, transmit, process and search them, making all earlier cultural technologies developed to handle these tasks (schools, libraries, written language itself) “equally unnecessary”. This will be neither advance nor regression. Evolution, remember, is maddeningly valueless.

The sooner we pave over this lot, the better

Nods to some ingenious medicine aside, this show seems hell-bent on convincing visitors that “nature” is a state of perpetual, terrible and gruesome conflict, and that – if your environmental competitors have their way – your whole lived experience is going to be filled with excruciating pain.

The boring beasts that changed the world

Some animals are so familiar, we barely see them. If we think of them at all, we categorise them according to their role in our lives: as pests or food; as unthinking labourers or toy versions of ourselves. If we looked at them as animals – non-human companions riding with us on our single Earth – what would we make of them? Have we raised loyal subjects, or hapless victims, or monsters?

Visiting the Museum of Ordinary Animals exhibition for New Scientist, 4 November 2017

November 3, 2017

Bloody marvellous

Some of the best pieces here are the most direct. In a riposte to the usual cock-and-balls graffiti found in public toilets, the Hotham Street Ladies have decorated the walls of the gallery’s gents with menstruating uteruses made of icing sugar and sweets.

Visiting the exhibition Blood: Life Uncut for New Scientist, 20 October 2017

The genius of making a little go a long way

One can taste the boosterism in the air at Illuminating India. Someone next to me used the word “Commonwealth” without irony. Would there have been such a spirit without Brexit? Probably not: this is a show about the genius of another country that very much wants to project Britain’s own global aspirations…

Visiting London’s Science Museum for New Scientist, 10 October 2017

October 15, 2017

Stalin’s meteorologist

I reviewed Olivier Rolin’s new book for The Daily Telegraph

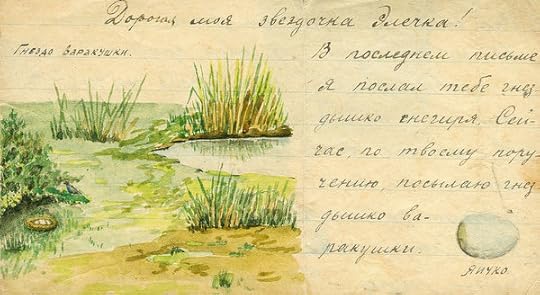

750,000 shot. This figure is exact; the Soviet secret police, the NKVD, kept meticulous records relating to their activities during Stalin’s Great Purge. How is anyone to encompass in words this horror, barely 80 years old? Some writers find the one to stand for the all: an Everyman to focus the reader’s horror and pity. Olivier Rolin found his when he was shown drawings and watercolours made by Alexey Wangenheim, an inmate of the Solovki prison camp in Russia’s Arctic north. He made them for his daughter, and they are reproduced as touching miniatures in this slim, devastating book, part travelogue, part transliteration of Wangenheim’s few letters home.

While many undesirables were labelled by national or racial identity, a huge number were betrayed by their accomplishments. Before he was denounced by a jealous colleague, Wangenheim ran a pan-Soviet weather service. He was not an exceptional scientist: more an efficient bureaucrat. He cannot even be relied on “to give colourful descriptions of the glories of nature” before setting sail, with over a thousand others, for a secret destination, not far outside the town of Medvezhegorsk. There, some time around October 1937, a single NKVD officer dispatched the lot of them, though he had help with the cudgelling, the transport, the grave-digging. While he went to work with his Nagant pistol, others were washing blood and brains off the trucks and tarpaulins.

Right to the bitter end, Wangenheim is a boring correspondent, always banging on about the Party. “My faith in the Soviet authorities has in no way been shaken” he says. “Has Comrade Stalin received my letter?” And again: “I have battled in my heart not to allow myself to think ill of the Soviet authorities or of the leaders”. Rolin makes gold of such monotony, exploiting the degree to which French lends itself to lists and repeated figures, and his translator Ros Schwartz has rendered these into English that is not just palatable, but often thrilling and always freighted with dread.

When Wangenheim is not reassuring his wife about the Bolshevik project, he is making mosaics out of stone chippings and brick dust: meticulous little portraits of — of all people — Stalin. Rolin openly struggles to understand his subject’s motivation: “In any case, blinkeredness or pathetic cunning, there is something sinister about seeing this man, this scholar, making of his own volition the portrait of the man in whose name he is being crucified.”

That Rolin finds a mystery here is of a piece with his awkward nostalgia for the promise of the Bolshevik revolution. Hovering like a miasma over some pages (though Rolin is too smart to succumb utterly) is that hoary old meme, “the revolution betrayed”. So let us be clear: the revolution was not betrayed. The revolution panned out exactly the way it was always going to pan out, whether Stalin was at the helm or not. It is also exactly the way the French revolution panned out, and for exactly the same reason.

Both French and Socialist revolutions sought to reinvent politics to reflect the imminent unification of all branches of human knowledge, and consequently, their radical simplification. By Marx’s day this idea, under the label “scientism”, had become yawningly conventional: also wrong.

Certainly by the time of the Bolshevik revolution, scientists better than Wangenheim — physicists, most famously — knew that the universe would not brook such simplification, neither under Marx nor under any other totalising system. Rationality remains a superb tool with which to investigate the world. But as a working model of the world, guiding political action, it leads only to terror.

To understand Wangenheim’s mosaic-making, we have to look past his work, diligently centralising and simplifying his own meteorological science to the point where a jealous colleague, deprived of his sinecure, denounced him. We need to look at the human consequences of this attempt at scientific government, and particularly at what radical simplification does to the human psyche. To order and simplify life is to bureaucratise it, and to bureaucratise human beings is make them behave like machines. Rolin says Wangenheim clung to the party for the sake of his own sanity. I don’t doubt it. But to cling to any human institution, or to any such removed and fortressed individual, is the act, not of a suffering human being but of a malfunctioning machine.

At the end of his 1940 film The Great Dictator Charles Chaplin, dressed in Adolf Hitler’s motley, broke the fourth wall to declare war on the “machine men with machine minds” that were then marching roughshod across his world. Regardless of Hitler’s defeat, this was a war we assuredly lost. To be sure the bureaucratic infection, like all infections, has adapted to ensure its own survival, and it is not so virulent as it was. The pleasures of bureaucracy are more evident now; its damages, though still very real, are less evident. “Disruption” has replaced the Purge. The Twitter user has replaced the police informant.

But let us be explicit here, where Rolin has been admirably artful and quietly insidious: the pleasures of bureaucracy in both eras are exactly the same. Wangenheim’s murderers lived in a world that had been made radically simple for them. In Utopia, all you have to do is your job (though if you don’t, Utopia falls apart). These men weren’t deprived of humanity: they were relieved of it. They experienced exactly what you or I feel when the burden of life’s ambiguities is lifted of a sudden from our shoulders: contentment, bordering on joy.

Simon Ings's Blog

- Simon Ings's profile

- 147 followers