Simon Ings's Blog, page 33

October 31, 2018

Liquid Crystal Display: Snap judgements

Visiting Liquid Crystal Display at SITE Gallery, Sheffield, for New Scientist, 31 October 2018

Untitled Gallery was founded in Sheffield in 1979. It specialised in photography. In 1996 it was renamed Site Gallery and steadily expanded its remit to cover the intersection between science and art. Nearly 30 years and a £1.7million refit later, Site Gallery is the new poster child of Sheffield’s Cultural Industries Quarter, with an exhibition, Liquid Crystal Display, that cleverly salutes its photographic past.

Most shows about art value the results over the ingredients. The picture matters more than the paint. The statue matters more than the stone. Exhibitions about photography give rather more space to process because photography’s ingredients are so involved and fascinating.

Liquid Crystal Display follows this photographic logic to its end. This is a show about the beauty, weight and messiness of materials we notice only when they’ve stopped working. It’s about the beauty created by a broken smartphone screen, a corroded battery, a cracked lens.

Site Gallery’s new exhibition – a cabinet of curiosities if ever there was one – collides science and art, the natural and the manufactured, the old and the new. It puts the exquisite sketches of 19th-century Scottish chemist and photographer Mungo Ponton (detailing his observations of how crystals polarise light), next to their nearest contemporary equivalent: microscopic studies (pictured) of liquid crystals caught in the process of self-organisation by Waad AlBawardi, a Saudi molecular biologist who’s currently in Edinburgh, researching the structure of DNA organisation inside cells.

This provocative pairing of the relatively simple and the manifestly complex is repeated several times. Near a selection of crystals from John Ruskin’s mineral collection sit the buckets, burners and batteries of Jonathan Kemp, Martin Howse and Ryan Jordan’s The Crystal World project, a tabletop installation recording their hot, smelly, borderline-hazardous effort to extract the original minerals from bits of scavenged computers. Curated by Laura Sillars, assisted by Site Gallery’s own Angelica Sule, Liquid Crystal Display reveals the material, mineral reality behind our oh-so-weightless holographic world of digital imagery. “Liquid crystals polarise light, produce colour and yet, as a material form, recede into the background of technology,” Sillars wrote in the catalogue to this show.

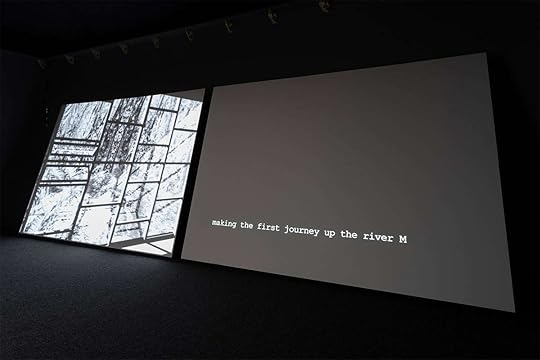

This awareness is not new, of course. In the 1960s, liquid crystals were being burned on overhead projectors to create psychedelic light shows. J G Ballard’s novel The Crystal World (1966) concocted a paranoid vision of a world and a civilisation returned (literally) to its mineral roots. That story receives a handsome homage here from the scifi-obsessed Norwegian artist Anne Lislegaard, whose stark monochrome animation (above) turns the sharp shadows and silhouettes cast by contemporary domestic furniture into insidious crystalline growths.

Arrayed within Anna Barham’s peculiar hexagonal cabinetwork, a gigantic piece of display furniture that is itself an artwork, the pictures, objects, films and devices in Liquid Crystal Display speak to pressing topical worries – resource depletion, environmental degradation, the creeping uncanny of digital experience – while at the same time evoking a peculiar nostalgia for our photochemical past.

The exhibition lacks one large signature object against which visitors can take selfies. A peculiar omission in a show that’s relaunching a gallery. And a bit of a shame for an exhibition that, in its left-field way, has handsomely captured the philosophical essence of photography.

October 30, 2018

Shobana Jeyasingh: Shaping Contagion

Discussing Jeyasingh’s 14-18 NOW dance commission for New Scientist, 11 October 2018

It still sounds mad – 14-18 NOW, the UK’s arts programme for the First World War centenary, commissioned a dance piece about the global flu pandemic. Why did you take this tragedy on – and how on earth did you shape it?

Shobana Jeyasingh I began by looking at the smallest element of the story, H1N1, the virus responsible for the Spanish flu. The mechanics of virology appealed to me from the moment I began my reading and research. I spoke to two experts at length: Wendy Barclay, at Imperial College, and John Oxford at Queen Mary College, both in London.

All the strategies the flu virus has for penetrating the cell fascinated me. How it battles past the cilia on the cell’s wall is only the beginning. Once inside the cell it has to find the nucleus, and because it has no motive power of its own, it must hitch rides on transport proteins which themselves are unidirectional, so the virus must leap from one protein to another in search of its target like someone leaping on and off trams.

It’s a strange and amazing narrative, even before the virus starts harnessing the cell’s machinery to churn out copies of itself, which is surely the strangest twist of all.

This is an incredibly dark subject to tackle

That’s what I said to John Oxford, who was part of the team that researched the shape of the H1N1 virus. But his work had made him feel very differently. He’d embarked on this huge archaeological project, looking for the best-preserved tissue that might be infected with the virus. Tissue from people buried in lead coffins, or in Alaskan permafrost.

And he found the families of these victims still recalling how their dying had been cared for. People knew they were in danger, if they nursed somebody with the flu. But, regardless, people gave that care to their family, their spouse, their child. And their everyday heroism was being remembered, even now. It’s a dark story, yes, but Oxford showed me that story in an incredible, wonderful light.

The way your dancers personify the virus is frankly terrifying. They’re not “robotic” but at one time they move like nightmare quadripeds – columns of flesh armed with four extrusions of equal power and length, like RNA strands

At this point, they’re not portraying living things. A virus is a sinister code more than a lifeform in its own right. It’s a strategy, playing itself out in opposition to the body, by recruiting the body’s own forces. It’s not “attacking” anything. It’s far more subtle, far more insidious than that. What killed you, once you were infected with H1N1, was not the virus itself, but the violence of your own immune response. Just the drama of it was fascinating for me.

The medical profession doesn’t get much of a look-in here?

Doctors recognised what kind of disease the Spanish Flu was from its symptoms, but they had no idea that viruses even existed. How could they? Viruses are so small, without an electron microscope you can’t even see them. Several suspected, rightly, that the disease was airborne, but of course filters that can screen out bacteria are no defence against viruses.

So the work of helping people fell, not on the medical profession, who were powerless against what they couldn’t understand, but onto the women – nurses, mothers, wives, carers – who risked their own lives to look after the sick. The last section of the work, “Everyday Heroes”, is about nursing: the irony that while men were either winning or losing on the battlefield, women at home were fighting what was mostly a losing battle against a far more serious threat.

Why was this threat not properly recognised at the time?

Nobody knew what caused the flu, or why the youngest and the fittest seemed most prone to die. The onset was so sudden and dramatic, people would fall sick and die within a few hours. Someone perfectly healthy at lunchtime might be dead at teatime.

In Manchester, the man who was in charge of public health, James Niven, woke up quite early to the fact that flu transmission shot up when people were gathered together. He tried to ban the Armistice Day celebrations in his city, but of course he was overruled. There was a huge spike in flu cases soon after. There are so many fascinating stories, but in 20 minutes, there’s a limit to what we can explore.

Contagion is not a long piece, but you’ve split it into distinct acts. Why?

It seemed the only way to contain such a complex story. The first section is called “Falling Like Flies”, which was the expression one Indian man used to describe how he lost his entire family in the blink of an eye: his little daughter, his wife, his brother, his nephews. This section is simply about the enormity of death. The second, “Viral Moves”, explores the dynamics of the virus. The third section, “Cold Delirium”, is about, well, exactly that.

What is “cold delirium”?

It’s a name that’s sometimes given to the virus’s neurological effects. One of the things we’ve begun to appreciate more and more – and this is why the official death count for the 1918 pandemic has risen recently – is that Spanish flu packs a huge psychological punch.

A lot of people who committed suicide in this period were most likely suffering the neurological effects of the virus. It triggered huge mental problems: screaming, fits, anxiety, episodes of aimless wandering.

And this wasn’t fully recognised then?

People noticed. But there was no means of reporting these cases to give people an idea of the shape and scale of the problem. Flu was not a reportable illness, like typhoid or plague. At the turn of the 20th century in Mumbai they had a plague that was fully documented and shaped the provision of public health. But in the case of flu, milder forms were so familiar, people didn’t really take much notice until the sheer numbers of the dead became unignorable.

And remember, in 1918 communication was not so effective. In Alaska, 90 per cent of a village community died, but there wasn’t any way to connect this episode to 20 million deaths in India. The connected global map that we carry around in our heads simply did not exist.

Contagion ‘s set is a series of white boxes, arranged neatly at one end, and at the other end rising up into the air chaotically. Do they represent blood cells or grave markers?

You’re on the right track, though the idea first came from looking at pictures of hospital beds. Hospital beds tend to be ordered and in lines, and then this huge event comes along to disrupt everything, and sweep everything before it.

York Mediale 2018: Playing with shadows

Visiting York Mediale 2018 for New Scientist, 19 October 2018

The dancers performing Strange Stranger at this year’s inaugural York Mediale (tagline: “Art, Meet the Future”) weren’t just moving about in the shadows. They were leaving shadows behind them, thanks to wrist-worn tracking devices and a complex, computer-driven LED-lit set. And over the course of the festival, which ran from 27 September to 6 October this year, visitors were able to explore the set and leave their own shadows in the air.

Alexander Whitley and his dance company have caught our eye before with 8 Minutes, a visceral and surprisingly true-to-fact dance about the internal processes of the sun. Their new piece is a play on the concept of the “data shadow” – a digital profile formed from all the information we unintentionally leave behind through our routine use of technology. That Whitley has turned to the dark for Strange Stranger says something about the eeriness that’s been slipping into contemporary art for some while.

It’s a mordant piece, and perhaps technically not quite there yet, because the dancers aren’t just leaving shadows; they’re actually getting lost in shadows. The net effect of all this energetic movement, then, is a sense of creeping powerlessness.

The same mood – part melancholy, part anxious – also marks Strata Rock Dust Stars, the flagship exhibition at this new media arts festival, which, it’s just been announced, is due to return in 2020.

Curated by Mike Stubbs, director of Liverpool’s FACT gallery, the exhibition runs until 25 November. Melancholy notes are struck by David Jacques, whose installation Oil is the Devil’s Excrement (2017) reveals by degrees that we have never been in control of the oil that powers our civilisation: it’s oil that has been in control of us. (You don’t have to take his word for it, either: the title of the piece is actually a quote Juan Pablo Perez Alfonzo, the founder of OPEC.)

Isaac Julien’s Stones Against Diamonds is another powerful hymn to our fatal misreading of our own values. Shot in a remote region of south-east Iceland in 2015, it juxtaposes luxury goods with jewel-like icescapes and ice blocks and advertisement-shiny waterfalls. Ice, it transpires, is the ultimate luxury good being celebrated (or mourned) among these multiple video panels, by a glamorous isolated figure (Vanessa Myrie) who, we can only suppose, has consumed everything else there is to consume.

Like every other living thing on this planet, humans are destined to expand to exploit all resources available to them, at which point they’ll plunge off a demographic cliff. There’s no tragedy in this. The tragedy is that we know it’s happening. We know the destruction we’re causing. We know what the consequences will be.

Strata Rock Dust Stars offers the visitor various coping mechanisms by which we might deal with this realisation. Liz Orton’s The Longest and Darkest of Recollections (2016) fuses geology, photography and memoir in a museum-like display that captures perfectly our poignant struggle to assign meaning to a world far older and bigger and dumber than ourselves. Agnes Meyer-Brandis’s on-going obsession with moon-dwelling geese (the conceit of the 17th-century bishop and proto-sf author Francis Godwin) offers fancy and absurdity as a palliative for our tragic condition. In a delicious parody of all those Anthropocene maunderings, her latest venture, Moon Core (2018), asks whether the droppings and egg-shells of moon geese might not have entered the lunar geological record.

When fancy and imagination collide with the real world, however, the result is not always charming. Worlds in the Making, an early video work by Ruth Jarman and Joe Gerhardt, who make work under the name Semiconductor, creates, if you can picture such a thing, a sort of paranoid geology, perfectly false and perfectly believable, and a dreadful reminder of how much we rely on trust for our understanding of the world.

Another way of coping with the tragedy of the human condition is to laugh at it. Away from the flagship exhibition, I stumbled across a new work by Rodrigo Lebrun, a young Brazilian-born artist who has very little patience with the seriousness of much contemporary art. “It’s just another way of ostracising the public,” he told me, as he unlocked the shipping container where his barely finished video installation, Green (Screen) Dreams, advertises the apocalyptic charm of Sunthorpe — think grim Humber Valley Scunthorpe rebranded as a tropical holiday destination minutes before a collapsed ice shelf-triggered tsunami arrives, coincident with the entire planet bursting into flame.

Hijacking the hyperbolic visuals of television advertising, Lebrun has created an advertisement for the future: a world in which the vagiaries of environmental collapse afford us little pockets of tremendous commercial opportunity in the seconds before Armageddon, and where all the difficult questions about population and pollution, environmental integrity and resource depletion, are breezily crammed into an eyeblink-fast on-screen reminder that “Terms and Conditions Apply”.

“Instead of creating solutions, we’ve been creating these weird alternate realities,” Lebrun says, “CGI-driven entertainments to numb the senses.” His installation blows the gaffe on this confidence trick. It’s frightening, and funny, and above all it’s energising. Commissioned by Invisible Dust, an environmental arts charity we last encountered driving a gigantic mobile cinema around the Scottish coast, Green (Screen) Dreams gets its next outing At North Lincolnshire Museum from 19 January next year. But that’s surely only the beginning for the piece and for Lebrun himself, whose combination of wit and savagery seems as rare, these days, as a moon-goose’s teeth.

Microphotography

Covering the Nikon Small World competition for New Scientist,11 October 2018

Microphotography has come along way since Nikon staged the first Nikon Small World competition in 1974. Finalists in 2018 harnessed a dizzying array of photographic techniques to achieve the spectacular results displayed here. A full-colour calendar of the winners is in the works, and people in the US can look forward to a national tour of the top images.

Yousef Al Habshi from the United Arab Emirates won first prize with the image above of the compound eyes and surrounding greenish scales of a weevil, Metapocyrtus subquadrulifer. It was made by stacking together 129 micrographs — photographs taken through a microscope. “I feel like I’m photographing a collection of jewelry,” said Al Habshi of his work with these beautiful Philippine beetles, which are more usually considered agricultural nuisances and targets for pest control.

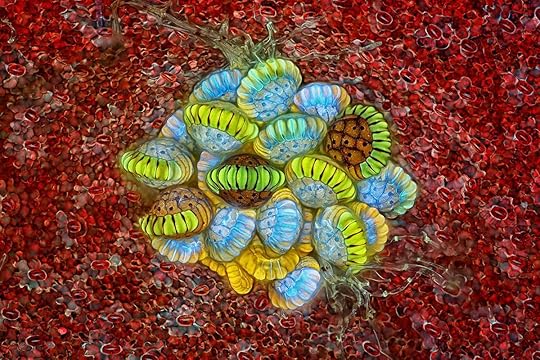

Rogelio Moreno from Panama won second prize for capturing the spore-containing structures of a fern (above). He used a technique called autoflorescence, in which ultraviolet light is used to pick out individual structures. Spores develop within a sporangium, and Moreno has successfully distinguished a group of these containers from the clustered structure called the sorus. Sporangiums at different stages of development show up in different colours.

Saulius Gugis from the USA photographed this spittle-bug in the process of making its “bubble-house”. The foamy structure helps the insect hide from predators, insulate itself and stay moist. The photograph won third prize.

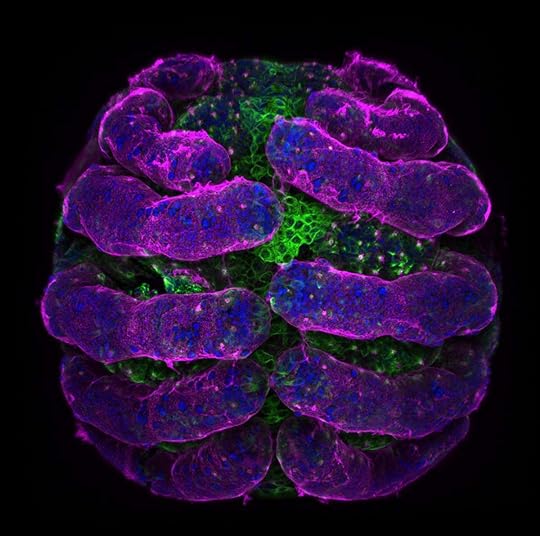

Other highlights from the prize include a portrayal of the first stirrings of arachnid life by Tessa Montague at Harvard University. The surface of this spider embryo (Parasteatoda tepidariorum) is picked out in pink. The cell nuclei are blue and other cell structures are green.

Looking for all the world like an extra from Luc Besson’s sci-fi film The Fifth Element, this magnificent mango seed weevil (Sternochetus mangiferae) earned Pia Scanlon, a researcher for the Government of Western Australia, a place among the finalists.

Yunchul Kim: Craft work

Visiting Dawns, Mine, Crystal by Yunchul Kim at the Korean Cultural Centre, London. For New Scientist, 27 October 2018.

NOSTALGIA was not the first word that sprung to mind when I visited a show at London’s Korean Cultural Centre by South Korean artist Yunchul Kim. At first glance, indeed, Kim’s art appears intimidatingly modern.

The new pieces exhibited were inspired by his residency last year at the CERN particle physics laboratory near Geneva, Switzerland. They centre around photonic crystals, colloids and particle detectors, and are placed in the context of earlier work, featuring eviscerated hard drives, pencil sketches of fluid flows and a “chemical synthesiser” turning the electrical current flowing through a droplet of seawater into a cloud of sound.

But for the scientists who are Kim’s most committed audience (and eager collaborators), there is something wonderfully old-fashioned about the way he works. Kim’s studio in Seoul is full of materials: homemade ferrofluids, gels, metals, all kinds of reagents, acids and oils. While labs (and not a few artists’ studios) grow more sterile and digital, his workspace remains stubbornly wedded to stuff. The artist’s wry description of his practice – “touching, staring, waiting for things to dry” – captures something of science’s lost materiality.

Kim’s latest work (see) shows a contraption in three parts that turns cosmic rays into bubbles suspended in space, a copper-aluminium sludge, stirred by hidden magnetic orreries, and a shattered gelatin rainbow. What are these but the results of a strange science that is the outcome of some spectacularly purposeless noodling?

The physicists at CERN loved it, and Kim soon found out why: “I make all my own machinery, and so do they,” he says. “Their love of craft is everywhere, from the colour for their cabling to the careful labelling of everything.”

Kim’s art is a reminder that science isn’t just there to be useful. It is also a craft. It’s something humans do, and something that, when presented this well, we are bound to enjoy.

October 19, 2018

When science becomes performance art

The great storehouses of our culture are now, for good and ill, in the cloud. Good: a museum can print an archival-grade sculpture or painting to inform an exhibition. Bad: no one can remember the password.

October 11, 2018

Edward Burtynsky: Fossil futures

The effects of mining, in particular, are irreversible. While animal burrows reach a few metres at most, humans carve out networks that can descend several kilometres, below the reach of erosion. They are likely to survive, at least in trace form, for millions or even billions of years.

An overview of The Anthropocene Project for New Scientist, 10 October 2018

Tomás Saraceno: Beneath an ocean of air

This is Saraceno’s answer to our global problems: he wants us to take to the air. That’s why he coined the term “Aerocene” for one of his projects. He wants people to think of climate change in terms of possibility, playfulness and, yes, escape. “We live beneath an ocean of air,” he once wrote, as he sketched his utopian vision of a city in the clouds. “But we’ve yet to find a way to inhabit it.”

Visiting Tomás Saraceno’s Berlin studio for New Scientist, 13 October 2018

October 5, 2018

Pierre Huyghe: Digital canvases and mind-reading machines

That UUmwelt turns out to be a show of great beauty; that the gallery-goer emerges from this most abstruse of high-tech shows with a re-invigorated appetite for the arch-traditional business of putting paint on canvas: that the gallery-goer does all the work, yet leaves feeling exhilarated, not exploited — all this is going to require some explanation…

Digital canvases and mind-reading machines

That UUmwelt turns out to be a show of great beauty; that the gallery-goer emerges from this most abstruse of high-tech shows with a re-invigorated appetite for the arch-traditional business of putting paint on canvas: that the gallery-goer does all the work, yet leaves feeling exhilarated, not exploited — all this is going to require some explanation…

Simon Ings's Blog

- Simon Ings's profile

- 147 followers