Simon Ings's Blog, page 31

March 19, 2019

Teeth and feathers

Visiting T. rex: The ultimate predator at the American Museum of Natural History in New York, for New Scientist, 13 March 2019

PALAEONTOLOGY was never this easy. Reach into a bin and pick up a weightless fossil bone hardly smaller than you are. Fling it into the air, in roughly the direction indicated by the glowing orange light. It fixes in place above you with a satisfying click. Add more bones. You are recreating the head of the most fearsome predator known to natural history: Tyrannosaurus rex. Once it is complete, the skull you have made makes this point nicely – by coming after you.

The American Museum of Natural History is 150 years old this year. One of its collectors, Barnum Brown, discovered the first fossil remains of the predator in Montana in 1902. So the museum has made T. rex the subject of its first exhibition celebrating the big anniversary.

The game I was playing, T. rex: Skeleton crew, is also the museum’s first foray into virtual reality. It is a short, sweet, multiplayer game that, if it doesn’t convey much scientific detail, nonetheless gives the viewer a glimpse of the first great puzzle palaeontologists confront: how to put scattered remains together. It also gives a real sense of the beast’s size: a fully grown T. rex (and they could live into their late 20s) was more than 12 metres long and weighed 15 tonnes.

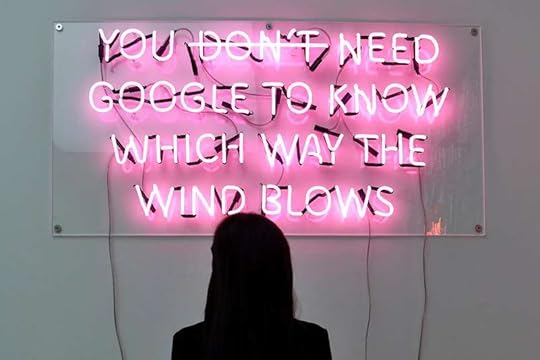

An extended version of this game, for home use, will feature a full virtual gallery tour. It has been put together by the Vive arm of tech firm HTC. Early on, in its project to establish a name in the cultural sector, the company decided not to compete with the digital realm’s top dog, Google Arts & Culture. Google, at least until recently, has tended to brand its efforts quite heavily because it brings a wealth of big data to its projects.

HTC Vive, by contrast, works behind the scenes with museums, cultural organisations and artists to realise relatively modest projects. By letting the client take the lead, it is learning faster than most what the VR medium can do. It cut its teeth on an explorable 3D rendering of Modigliani’s studio in the Tate Modern in London in 2017 and created an immersive exploration of Claude Monet’s approach to painting in The Water Lily Obsession, now a permanent feature at the Musée de l’Orangerie in Paris.

The trick, it seems, is to focus, to make immersion and physical sensation the point of each piece. Above all, the idea is to slow down. VR isn’t a traditional teaching aid. The Monet project in particular revealed how good VR is at conveying craft knowledge.

But if, instead, a VR installation delivers a brief, memorable, even magical experience, this, too, has value. Skeleton crew is a powerful prompt to the imagination. It isn’t, and isn’t meant to be, the star of this show. The models are the real draw here. Traditionally fashioned life-size renderings of tyrannosaurs big and small, scaled, tufted and sometimes fully feathered, their variety reflecting the explosion of palaeobiological research that has transformed our understanding of millions of years of Mesozoic fauna over the past 20 years. We can now track trace chemicals in the material surrounding a fossil so precisely that we even know the colour of some species’ eggs.

T. rex: The ultimate predator certainly delivers on its brash, child-friendly title. Terrifying facts abound. T. rex‘s jaws had a maximum bite force 10 times that of an alligator – enough not just to break bone, but to burst it into swallowable splinters.

But the really impressive thing about the show are the questions it uses to convey the sheer breadth of palaeontology. What did T. rex sound like? No one knows, but here are a mixing desk and some observations about how animals vocalise: go figure. Is this fossil a juvenile T. rex or a separate species? Here is a summary of the arguments: have a think.

Staged in a huge cavern-like hall, with shadow-puppet predators and prey battling for dear life, T. rex: The ultimate predator will wow families. Thankfully, it is also a show that credits their intelligence.

March 12, 2019

This God has taste

The Guardian spiked this one: a review of I am God by Giacomo Sartori, translated from the Italian by Frederika Randall (Restless Books)

This sweet, silly, not-so-shallow entertainment from 2016 ( Sono Dio, the first of Giacomo Sartori’s works to receive an English translation) takes an age before naming its young protagonist. For ages, she’s simply “the tall one”; sometimes, “the sodomatrix” (she inseminates cattle for a living).

Her name is Daphne, “a militant atheist who spends her nights trying to sabotage the Vatican website,” and she ekes out a precarious professional living in the edgeland laboratories of post-industrial Italy. The narrator sketches her relationship with her stoner dad and her love triangle with Lothario (or Apollo, or Randy — it doesn’t really matter) and his diminutive girlfriend. His eye is sharp: at one point we get to glimpse “the palm of [Daphne’s] hand moving over [Lothario’s] chest as if washing a window.” But the narrator keeps slipping off the point into a welter of self-absorbed footnotes. Daphne interests him — indeed, he’s besotted — but really he’s more interested in himself. And no wonder. As he never tires of repeating, with an ever more desperate compulsion: “I am God”.

This is a God with time on his hands. Not for him a purely functional creation with “trees of shapeless gelatin broth, made of a revolting goo like industrial waste. Neon lights that suddenly flick off, instead of sunsets.” This God has taste.

Why, then, does he find himself falling for such an emotionally careless mortal as Daphne? Could it be “that this gimpy human language hasn’t already contaminated me with some human germ…?” Sly comic business ensues as, with every word He utters, God paints Himself further into a corner it will take a miracle to escape.

The author Giacomo Sartori is a soil specialist turned novelist and one of the founders of Nazione Indiana, a blog and cultural project created to give voice to Italy’s literary eccentrics. Italy’s stultifying rural culture has been his main target up to now. Here, though, he’s taking shots at humanity in general: “They’re such hucksters,” he sighs, from behind the novel’s divine veil, “so reliably unpredictable, immoral and nuts that anyone observing them is soon transfixed.”

Of course, Sartori’s theological gags could be read just as easily as the humdrum concerns of a writer falling under the spell of their characters. But there’s much to relish in the way God comes to appreciate more deeply the lot of his favourite playthings, “telling a million stories, twisting the facts, philosophizing, drowning in their own words. All vain efforts; unhappy they are, unhappy they remain.”

Slightly fleshy, slightly scabby, cast adrift

The New York-based artist Matthew Day Jackson takes mixed media seriously. Behind the techniques and materials, the molten lead and the axe handles, the T-shirts and laser-etched Formica, Jackson’s aesthetic sees the world not as a continuum but as a mass of odd juxtapositions. Since his first big solo show in 2004, he has intertwined the grotesque and the beautiful. Every ten years, he paints a picture of himself as a corpse, but the majority of his work is mischievous, holding the autobiographical and the cerebral in an uneasy balance.

Hauser and Wirth, an international gallery with a strong educational remit, regularly brings its spikier artists to its property in Bruton, Somerset, to stay, work and reflect. The residencies come without strings, there are no prescribed outcomes, and one suspects there’s a certain mischief in who gets chosen. First to arrive, in 2014, was the (intermittently scary) video artist Pipilotti Rist. Seduced by her surroundings, she came up with sensuously observed close-ups of bodies and leaves in intimate proximity. Nothing wrong with that, of course. But it’s a risk for the gallery, and a challenge for the artists who stay here, that the landscape round about is so ridiculously seductive.

Showing next door to Matthew Day Jackson, Eve, an exhibition of paintings by the Somerset-based artist Catherine Goodman, is unashamedly paradisal. Even its edge of Freudian melancholy proves heartwarming in the end.

What on earth will Jackson, a cerebral city-dwelling proponent of an aesthetic he dubs the “horriful”, do with all this serried loveliness? He says that at first he found the landscape hard to read. “It’s more like urban space”, he says. “Everywhere you look, you can trace how humans have engaged with this place.” He can’t get over the time-worn depth of the lanes here. There’s no equivalent back home: “Maybe in Oregon and Wyoming, you can find tracks still rutted by wagon wheels”.

Predictably, for an artist who’s spent his career mapping the failures of American utopianism, Jackson has responded to the beauty around him by mourning its passing. His Solipsist collage-paintings of silk-screened Formica zoom out to encompass large swathes of the planet. Seen from various orbital viewpoints (the images are based on photographs taken by NASA astronauts) four elements emerge. Mine workings strip the Earth back to, well, its earth. The hopelessly polluted Ganges and the virtually vanished Ural Sea stand for water. Smoke plumes from forest fires give a shape to air. Yellowstone Lake inhabits a caldera that, if it erupted, would consume most life on Earth.

Each landscape, weirdly colourized (“Formica limits your colour palette”), laser etched with precise contours and subtle, uninterpretable boundary lines, resembles a computer-readable map. “Over” it (or, to be literal about this, embedded in it) is the flattened image of a satellite, made of cast lead.

The fact that the satellite observing the view is itself melted into the picture suggests a colossal foreshortening. There’s something suggestive of Jean Dubuffet, too, in the way the texture of the satellite is employed to convey a radical flatness. There’s no shade here, no occlusion, no hint of curvature. Human activity and human destiny are being measured and metricized to the point where even the planet has nowhere to turn.

Jackson’s flower paintings in the next room continue the theme: vases of hallucinatory Formica and fabric blooms, backlit by unearthly aurorae that may reference the tie-dye fad of the early 1970s but are more likely – given the way this show is going – something ghastly to do with nuclear testing.

The paintings work with the Astroturf floor and Jackson’s experimental, sculptural furniture to explore the idea that we only ever see things through their use. This isn’t a human foible: living things generally only sense what is relevant to their survival. So if Jackson is holding humanity to account here, it is a gentle and considered judgement. “What we most want is to feel that we exist”, he says, as we contemplate vanished seas and shredded mountain ranges. “We want not be lonely. Hence the appeal of metrics: they give us a sense of accomplishment.”

It can be a nuisance, having the artist around when you’re viewing a show. I was initially thinking about our greed and rapacity, and now, looking at these spoiled and garishly mapped earths, all I can see is our pathos: how we are polishing our rock down to the granite, just so we can glimpse ourselves in it.

Pathetic Fallacy is a well-chosen title for this show. John Ruskin coined the phrase to have a dig at the emotional falsity of poets who made clouds weep and trees groan. Jackson’s show is more in the spirit of Wordsworth’s defence of the practice, arguing that “objects . . . derive their influence not from properties inherent in them . . . but from such as are bestowed upon them by the minds of those who are conversant with or affected by these objects”.

In other words, we impose ourselves on the world because we feel we are the only meaning makers. On the way out, I pass more pictures: flattened lead satellites, cast in moulds made of corrugated cardboard, twine, sawdust, glue. This close, they appear slightly fleshy, slightly scabby, cast adrift, and travelling out into space.

A world that has run out of normal

As global temperatures rise, and the mean sea-level with them, I have been tracing the likely flood levels of the Thames Valley, to see which of my literary rivals will disappear beneath the waves first. I live on a hill, and what I’d like to say is: you’ll be stuck with me a while longer than most. But on the day I had set aside to consume David Wallace-Wells’s terrifying account of climate change and the future of our species (there isn’t one), the water supply to my block was unaccountably cut off. Failing to make a cup of tea reminded me, with some force, of what ought to be obvious: that my hill is a post-apocalyptic death-trap.

11 April 2019: Smart Robots, Mortal Engines

Come to Cinema 3 at London’s Barbican Centre, where I’ll be kicking off a season of Stanislaw Lem on film with the Brothers Quay, artists Andrzej Klimowski and Danusia Schejbal, and Dr Mark Bould, author of the BFI Classics monograph on Andrei Tarkovsky’s Solaris.

We’ve got some short films kick off the evening at 6.45pm on Thursday 11 April. More details here.

February 7, 2019

And so we wait

In the 1996 comedy film Swingers, Jon Favreau plays Mike, a young man in love with love, and at war with the answerphones of the world. “Hi,” says one young woman’s machine, “this is Nikki. Leave a message,” prompting Mike to work, flub after flub, through an entire, entirely fictitious, relationship with the absent Nikki. “This just isn’t working out,” he sighs, on about his 20th attempt to leave a message that is neither creepy nor incoherent. “I – I think you’re great, but, uh, I – I… Maybe we should just take some time off from each other. It’s not you, it’s me. It’s what I’m going through.”

Thinking about Delayed Response by Jason Farman (Yale) for the Telegraph, 6 February 2019.

February 5, 2019

Tonight the World

We could be in for a rather stilted, tech-heavy exploration of the artist’s fraught family’s history. But the way the gallery has been decked out suggests (rightly) that a warmer, more intimate, ultimately more disturbing game is afoot. Past the first screen, fellow gallery-goers bleed in and out of view round a series of curved wooden walls painted a warm terracotta. Is the colour a reference to interwar architecture? All I can think of is the porn set in David Cronenberg’s existentialist shocker Videodrome. There is something distinctly fleshy going on.

Visiting Tonight the World, Daria Martin’s new show at the Barbican, for the Financial Times, 5 February 2019

February 1, 2019

A place that exists only in moonlight

Paterson cares about measurement. Turner cared about witness. An honestly witnessed play of light against a cloud can be achieved through the right squiggle. An accurate measurement of the same phenomenon must be the collaborative work of meteorologists, atmospheric scientists, astronomers, colour scientists, and who knows how many other specialists, with Paterson riding everyone’s coat-tails as a sort of tourist.

January 27, 2019

Making abstract life

Talking to the design engineer Yamanaka Shunji for New Scientist, 23 January 2019

Five years ago, desktop 3D printers were poised to change the world. A couple of things got in the way. The print resolution wasn’t very good. Who wants to drink from a tessellated cup?

More important, it turned out that none of us could design our way out of a wet paper bag.

Japanese designer Yamanaka Shunji calls forth one-piece walking machines from vinyl-powder printers the way the virtuoso Phyllis Chen conjures concert programmes from toy pianos. There’s so much evident genius at work, you marvel that either has time for such silliness.

There’s method here, of course: Yamanaka’s X-Design programme at Keio University turns out objects bigger than the drums in which they’re sintered, by printing them in folded form. It’s a technique lifted from space-station design, though starry-eyed Western journalists, obsessed with Japanese design, tend to reach for origami metaphors.

Yamanaka’s international touring show, which is stopping off at Japan House in London until mid-March, knows which cultural buttons to press. The tables on which his machine prototypes are displayed are steel sheets, rolled to a curve and strung under tension between floor and ceiling, so visitors find themselves walking among what appear to be unfolded paper scrolls. If anything can seduce you into buying a £100 sake cup when you exit the gift shop, it’s this elegant, transfixing show.

“We often make robots for their own sake,” says Yamanaka, blithely, “but usefulness is also important for me. I’m always switching between these two ways of thinking as I work on a design.”

The beauty of his work is evident from the first. Its purpose, and its significance, take a little unpacking.

Rami, for example: it’s a below-the-knee running prosthesis developed for the athlete Takakura Saki, who represented Japan during the 2012 Paralympics. Working from right to left, one observes how a rather clunky running blade mutated into a generative, organic dream of a limb, before being reined back into a new and practical form. The engineering is rigorous, but the inspiration was aesthetic: “We hoped the harmony between human and object could be improved by re-designing the thing to be more physically attractive.”

Think about that a second. It’s an odd thing to say. It suggests that an artistic judgement can spur on and inform an engineering advance. And so, it does, in Yamanaka’s practice, again, and again.

Yamanaka, is an engineer who spent much of his time at university drawing manga, and cut his teeth on car design at Nissan. He wants to make something clear, though: “Engineering and art don’t flow into each other. The methodologies of art and science are very different, as different as objectivity and subjectivity. They are fundamental attitudes. The trick, in design, is to change your attitude, from moment to moment.” Under Yamanaka’s tutelage, you learn to switch gears, not grind them.

Eventually Yamanaka lost interest in giving structure and design to existing technology. “I felt if one could directly nurture technological seeds, more imaginative products could be created.” It was the first step on a path toward designing for robot-human interaction.

Yamanaka – so punctilious, so polite – begins to relax, as he contemplates the work of his peers: Engineers are always developing robots that are realistic, in a linear way that associates life with things, he says, adding that they are obsessed with being more and more “real”. Consequently, he adds, a lot of their work is “horrible. They’re making zombies!”

Artists have already established a much better approach, he explains: quite simply, artists know how to sketch. They know how to reduce, and abstract. “From ancient times, art has been about the right line, the right gesture. Abstraction gets at reality, not by mimicking it, but by purifying it. By spotting and exploring what’s essential.”

Yamanaka’s robots don’t copy particular animals or people, but emerge from close observation of how living things move and behave. He is fascinated by how even unliving objects sometimes seem to transmit the presence of life or intelligence. “We have a sensitivity for what’s living and what’s not,” he observes. “We’re always searching for an element of living behaviour. If it moves, and especially if it responds to touch, we immediately suspect it has some kind of intellect. As a designer I’m interested in the elements of that assumption.”

So it is, inevitably, that the most unassuming machine turns out to hold the key to the whole exhibition. Apostroph is the fruit of a collaboration with Manfred Hild, at Sony’s Computer Science Laboratories in Paris. It’s a hinged body made up of several curving frames, suggesting a gentle logarithmic spiral.

Each joint contains a motor which is programmed to resist external force. Leave it alone, and it will respond to gravity. It will try to stand. Sometimes it expands into a broad, bridge-like arch; at other times it slides one part of itself through another, curls up and rolls away.

As an engineer, you always follow a line of logic, says Yamanaka. You think in a linear way. It’s a valuable way of proceeding, but unsuited to exploration. Armed with fragile, good-enough 3D-printed prototypes, Yamanaka has found a way to do without blueprints, responding to the models he makes as an artist would.

In this, he’s both playing to his strengths as a frustrated manga illustrator, and preparing his students for a future in which the old industrial procedures no longer apply. “Blueprints are like messages which ensure the designer and manufacturer are on the same page,” he explains. “If, however, the final material could be manipulated in real time, then there would be no need to translate ideas into blueprints.”

It’s a seductive spiel but I can’t help but ask what all these elegant but mostly impractical forms are all, well, for.

Yamanaka’s answer is that they’re to make the future bearable. “I think the perception of subtle lifelike behaviour is key to communication in a future full of intelligent machines,” he says. “Right now we address robots directly, guiding their operations. But in the future, with so many intelligent objects in our life, we’ll not have the time or the patience or even the ability to be so precise. Body language and unconscious communication will be far more important. So designing a lifelike element into our machines is far more important than just tinkering with their shape.”

By now we’ve left the gallery and are standing before Flagella, a mechanical mobile made for Yamanaka’s 2009 exhibition Bones, held in Tokyo Midtown. Flagella is powered by a motor with three units that repeatedly rotate and counter-rotate, its movements supple and smooth like an anemone. It’s hard to believe the entire machine is made from hard materials.

There’s a child standing in front of it. His parents are presumably off somewhere agonising over sake cups, dinky tea pots, bowls that cost a month’s rent. As we watch, the boy begins to dance, riffing off the automaton’s moves, trying to find gestures to match the weavings of the machine.

“This one is of no practical purpose whatsoever,” Yamanaka smiles. But he doesn’t really think that. And now, neither do I.

January 4, 2019

Praying to the World Machine

Attending Belief in AI in Dubai for New Scientist, 4 January 2018

In late spring this year, the Barbican Centre in London will explore the promise and perils of artificial intelligence in a festival of films, workshops, concerts, talks and exhibitions. Even before the show opens, however, I have a bone to pick: what on earth induced the organisers to call their show AI: More than human?

More than human? What are we being sold here? What are we being asked to assume, about the technology and about ourselves?

Language is at the heart of the problem. In his 2007 book, The Emotion Machine, computer scientist Marvin Minsky deplored (although even he couldn’t altogether avoid) the use of “suitcase words”: his phrase for words conveying specialist technical detail through simple metaphors. Think what we are doing when we say metal alloys “remember” their shape, or that a search engine offers “intelligent” answers to a query.

Without metaphors and the human tendency to personify, we would never be able to converse, let alone explore technical subjects, but the price we pay for communication is a credulity when it comes to modelling how the world actually works. No wonder we are outraged when AI doesn’t behave intelligently. But it isn’t the program playing us false, rather the name we gave it.

Then there is the problem outlined by Benjamin Bratton, director of the Center for Design and Geopolitics at the University of California, San Diego, and author of cyber bible The Stack. Speaking at Dubai’s Belief in AI symposium last year, he said we use suitcase words from religion when we talk about AI, because we simply don’t know what AI is yet.

For how long, he asked, should we go along with the prevailing hype and indulge the idea that artificial intelligence resembles (never mind surpasses) human intelligence? Might this warp or spoil a promising technology?

The Dubai symposium, organised by Kenric McDowell and Ben Vickers, interrogated these questions well. McDowell leads the Artists and Machine Intelligence programme at Google Research, while Vickers has overseen experiments in neural-network art at the Serpentine Gallery in London. Conversations, talks and screenings explored what they called a “monumental shift in how societies construct the everyday”, as we increasingly hand over our decision-making to non-humans.

Some of this territory is familiar. Ramon Amaro, a design engineer at Goldsmith, University of London, drew the obvious moral from the story of researcher Joy Buolamwini, whose facial-recognition art project The Aspire Mirror refused to recognise her because of her black skin.

The point is not simple racism. The truth is even more disturbing: machines are nowhere near clever enough to handle the huge spread of normal distribution on which virtually all human characteristics and behaviours lie. The tendency to exclude is embedded in the mathematics of these machines, and no patching can fix it.

Yuk Hui, a philosopher who studied computer engineering and philosophy at the University of Hong Kong, broadened the lesson. Rational, disinterested thinking machines are simply impossible to build. The problem is not technical but formal, because thinking always has a purpose: without a goal, it is too expensive a process to arise spontaneously.

The more machines emulate real brains, argued Hui, the more they will evolve – from autonomic response to brute urge to emotion. The implication is clear. When we give these recursive neural networks access to the internet, we are setting wild animals loose.

Although the speakers were well-informed, Belief in AI was never intended to be a technical conference, and so ran the risk of all such speculative endeavours – drowning in hyperbole. Artists using neural networks in their practice are painfully aware of this. One artist absent from the conference, but cited by several speakers, was Turkish-born Memo Akten, based at Somerset House in London.

His neural networks make predictions on live webcam input, using previously seen images to make sense of new ones. In one experiment, a scene including a dishcloth is converted into a Turneresque animation by a recursive neural network trained on seascapes. The temptation to say this network is “interpreting” the view, and “creating” art from it, is well nigh irresistible. It drives Akten crazy. Earlier this year in a public forum he threatened to strangle a kitten whenever anyone in the audience personified AI, by talking about “the AI”, for instance.

It was left to novelist Rana Dasgupta to really put the frighteners on us as he coolly unpicked the state of automated late capitalism. Today, capital and rental income are the true indices of political participation, just as they were before the industrial revolution. Wage rises? Improved working conditions? Aspiration? All so last year. Automation has made their obliteration possible, by reducing to virtually nothing the costs of manufacture.

Dasgupta’s vision of lives spent in subjection to a World Machine – fertile, terrifying, inhuman, unethical, and not in the least interested in us – was also a suitcase of sorts, too, containing a lot of hype, and no small amount of theology. It was also impossible to dismiss.

Cultural institutions dabbling in the AI pond should note the obvious moral. When we design something we decide to call an artificial intelligence, we commit ourselves to a linguistic path we shouldn’t pursue. To put it more simply: we must be careful what we wish for.

Simon Ings's Blog

- Simon Ings's profile

- 147 followers