Simon Ings's Blog, page 13

August 31, 2022

A balloon bursts

Watching The Directors: five short films by Marcus Coates, for New Scientist, 31 August 2022

In a flat on the fifth floor of Chaucer House, a post-war social housing block in London’s Pimlico, artist Marcus Coates is being variously nudged, bullied and shocked out of his sense of what is real.

Controlling the process is Lucy, a teenager in recovery from psychosis. Through Coates’s earpiece, she prompt Coates in how to behave, when to sit and when to stand, what to touch, and what to avoid, what to look at, what to think about, what to feel. Sometimes Coates asks for guidance, but more often than not Lucy’s reply is drowned out by a second voice, chilling, over-loud, warning the artist not to ask so many questions.

A cardboard cut-out figure appears at the foot of Coates’s bed — a clown girl with bleeding feet. It’s a life-size blow-up of a sketch Coates himself was instructed to draw a moment before. Through his earpiece a balloon bursts, shockingly loud, nearly knocking him to the ground.

Commissioned and produced by the arts development company Artangel, The Directors is a series of five short films, each directed by someone in recovery from psychosis. In each film, the director guides Coates as he recreates, as best he can, specific aspects and recollections of their experience. These are not rehearsed performances; Coates receives instructions in real-time through an ear-piece. (That this evokes, with some precision the auditory hallucinations of psychosis, is a coincidence lost on no one.)

So: some questions. In the course of each tricky, disorientating and sometimes very frightening film, does Marcus Coates at any point experience psychosis? And does it matter?

Attempts to imagine our way into the experiences of other beings, human or non-human, have for a long while fallen under the shadow of an essay written in 1974 by American philosopher Thomas Nagel. “What Is It Like to Be a Bat?” wasn’t about bats so much as about the continuity of consciousness. I can imagine what it would be like for me to be a bat. But, says Nagel, that’s not the same as knowing what’s it’s like for a bat to be a bat.

Nagel’s lesson in gloomy solipsism is all very well in philosophy. Applied to natural history, though — where even a vague notion of what a bat feels like might help a naturalist towards a moment of insight — it merely sticks the perfect in the way of the good.

Coates’s work consistently champions the vexed, imperfect, utterly necessary business of imagining our way into other heads, human and non-human. 2013’s Dawn Chorus revealed common ground between human and bird vocalisation. He slowed recordings of bird song down twenty-fold, had people learn these slowed-down songs, filmed them in performance, then sped these films up twenty times. The result is a charming but very startling glimpse of what humans might look and sound like brought up to “bird speed”.

Three years before in 2010 The Trip, a collaboration with St. John’s Hospice in London, Coates enacted the unfulfilled dream of an anthropologist, Alex H. Journeying to the Amazon, he followed very precise instructions so that the dying man could conduct, by a sort of remote control, his unrealised last field trip.

The Directors is a work in that spirit. Inspired by a 2017 residency at the Maudsley psychiatric hospital in London, Coates effort to embody and express the breadth and complexity of psychotic experience is in part a learning experience. The project’s extensive advisory group includes Isabel Valli, a neuroscientist at King’s College London with a particular expertise in psychosis.

In the end, though, Coates is thrown back on his own resources, having to imagine his way into a condition which, in Lucy’s experience, robbed her of any certainty in the perceived world, leaving her emotions free to spiral into mistrust, fear and horror.

Lucy’s film is being screened in the tiny bedroom where her film was shot. The other films are screened in different nearby locations, including one in the Churchill Gardens Estate’s thirty-seater cinema. This film, arguably the most claustrophobic and frightening of the lot, finds Coates drenched in ice-water and toasted by electric bar heaters in an attempt to simulate the overwhelming tactile hallucinations that psychosis can trigger.

Asked by the producers at ArtAngel whether he had found the exercise in any way exploitative the director of this film, Marcus Gordon, replied: “Well, there’s no doubt I’ve exploited the artist.”

August 17, 2022

Dreams of a fresh crab supper

Reading David Peña-Guzmán’s When Animals Dream for New Scientist, 17 August 2022

Heidi the octopus is dreaming. As she sleeps, her skin changes from smooth and white to flashing yellow and orange, to deepest purple, to a series of light greys and yellows, criss-crossed by ridges and spiky horns. Heidi’s human carer David Scheel has seen this pattern before in waking octopuses: Heidi, he says, is dreaming of catching and eating a crab.

The story of Heidi’s dream, screened in 2019 in the documentary “Octopuses: Making Contact”, provides the starting point for When Animals Dream, an exploration of non-human imaginations by David Pena-Guzman, a philosopher at San Francisco State University.

The Roman philosopher-poet Lucretius thought animals dreamt. So did Charles Darwin. The idea only lost its respectability for about a century, roughly between 1880 to 1980, when the reflex was king and behaviourism ruled the psychology laboratory.

In the classical conditioning developed by Ivan Pavlov, it is possible to argue that your trained salivation to the sound of a bell is “just a reflex”. But later studies in this mould never really banished the interior, imaginative lives of animals. These later studies relied on a different kind of conditioning, called “operant conditioning”, in which you behave in a certain way before you receive a reward or avoid a punishment. The experimenter can claim all they want that the trained rat is “conditioned”; still, that rat running through its maze is acting for all the world as though it expects something.

In fact, there’s no “as though” about it. Pena-Guzman, in a book rich in laboratory and experimental detail, describes how rats, during their exploration of a maze, will dream up imaginary mazes, and imaginary rewards — all as revealed by distinctive activity in their hippocampuses.

Clinical proofs that animals have imaginations are intriguing enough, but what really dragged the study of animal dreaming back into the light was our better understanding of how humans dream.

From the 1950s to the 1970s we were constantly being assured that our dreams were mere random activity in the pons (the part of the brainstem that connects the medulla to the midbrain). But we’ve since learned that dreaming involves many more brain areas, including the parietal lobes (involved in the representation of physical spaces) and frontal lobes (responsible among other things for emotional regulation).

At this point, the sight of a dog dreaming of chasing a ball became altogether too provocative to discount. The dog’s movements while dreaming mirror its waking behaviours too closely for us to say that they lack any significance.

Which animals dream? Pena-Guzman’s list is too long to quote in its entirety. There are mice, dogs and platypuses, beluga whales and ostriches, penguins, chameleons and iguanas, cuttlefish and octopuses — “the jury is still out on crocodiles and turtles.”

The brain structures of these animals may be nothing like our own; nonetheless, studies of sleeping brains throw up startling commonalities, suggesting, perhaps, that dreaming is a talent to which many different branches of the evolutionary tree have converged.

Pena-Guzman poses big questions. When did dreaming first emerge and why? By what paths did it find its way into so many branches of the evolutionary tree? And — surely the biggest question of all — what are we do with this information?

Pena-Guzman says dreams are morally significant “because they reveal animals to be both carriers and sources of moral value, which is to say, beings who matter and for whom things matter.”

In short, dreams imply the existence of a self. And whether or not that self can think rationally, act voluntarily, or produce linguistic reports, just like a human, is neither here nor there. The fact is, animals that dream “have a phenomenally charged experience of the world… they sense, feel and perceive.”

Starting from the unlikely-sounding assertion that Heidi the octopus dreams of fresh crab suppers, Pena-Guzman assembles a short, powerful, closely argued and hugely well evidenced case for animal personhood. This book will change minds.

August 10, 2022

Some rude remarks about Aberdeen

Reading Sarah Chaney’s Am I Normal? for new Scientist, 10 August 2022

In the collections of University College London there is a pair of gloves belonging to the nineteenth-century polymath Francis Galton. Galton’s motto was “Whenever you can, count”. The left glove has a pin in the thumb and a pad of felt across the fingers. Placing a strip of paper over the felt, Galton could then, by touching different fingers with the pin, keep track of what he saw without anyone noticing. A beautiful female, passing him by, was registered on one finger: her plain companion was registered on another. With these tallies, Galton thought he might in time be able to assemble a beauty map of Great Britain. The project foundered, though not before Galton had committed to paper some rude remarks about Aberdeen.

Galton’s beauty map is easy to throw rocks at. Had he completed it, it would have been not so much a map of British physiognomic variation, as a record of his own tastes, prejudices and shifting predilections during a long journey.

But as Sarah Chaney’s book makes clear, when it comes to the human body, the human mind, and human society, there can be no such thing as an altogether objective study. There is no moral or existential “outside” from which to begin such a study. The effort to gain such a perspective is worthwhile, but the best studies will always need reinterpreting for new audiences and next generations.

Am I Normal? gives often very uncomfortable social and political context to the historical effort to identify norms of human physiology, behaviour and social interaction. Study after study is shown to be hopelessly tied to its historical moment. (The less said about “drapetomiania”, the putative mental illness discovered among runaway slaves, the better.)

And it would be the easiest job in the world, and the cheapest, to wield these horrors as blunt weapons to tear down both medicine and the social sciences. It is true that in some areas, measurement has elicited surprisingly little insight — witness the relative lack of progress made in the last century in the field of mental health. But while conditions like schizophrenia are real, and ruinous, do we really want to give up our effort at understanding?

It is certainly true, that we have paid not nearly enough attention, at least until recently, to where our data was coming from. Research has to begin somewhere, of course, but should we really still be basing so much of our medicine, our social policy and even our design decisions on data drawn (and sometimes a very long time ago) from people in Western, educated, industrialised, rich and democratic (WEIRD) societies?

Chaney shows how studies that sought human norms can just as easily detect diversity. All it needs is a little humility, a little imagination, and an underlying awareness that in these fields, the truth does not stay still.

August 3, 2022

Driven by ghosts

Watching Explorer by Matthew Dyas for New Scientit, 3 August 2022

Explorer is a documentary about Ranulph Feinnes, the first man to circumnavigate the earth from Pole to Pole without recourse to flight.

It is a film full of ghosts. Its subject emerges slowly from snatches of previous documentaries, interviews, snatches of home movies, headlines. The film touts Feinnes’ unknowability: a risky strategy for audiences new to the man and his achievements, though the intrigue pays off handsomely in time.

Feinnes is not a man driven by mysterious and delicate internal forces. This is a man driven, simply and directly, by ghosts. Four months before his birth, Feinnes’s father was killed by a German landmine in Italy. His grandfather also died in the service of his country. It was young Ranulph’s intention to follow in their footsteps. Brought up in a household of indomitable women, he wanted to live up to the dad he never knew.

It was Feinnes’s first wife and former childhood sweetheart Ginny who devised the expedition that would make Feinnes a household name and make her the first woman to be awarded the Polar Medal. Seven years in the planning, Feinnes’s three-year Tranglobal expedition, from 1979 to 1982 was, with hindsight, the last of the great hero-projects of western expedition-making. The advent of satellite photography and instantaneous satellite communication has made much human adventure redundant, and undermined our old notions of physical heroism. In an era of extinctions and climate change, the notion of a human “pitting themselves against nature” has acquired a slightly “off” flavour.

Prevented by a stretch of open water from reaching the North Pole in 1984, Feinnes has long been one of our most eloquent witnesses to global warming. Nay-sayers will say there is something rotten at the heart of a white man’s exploration of what to him are far-off places. Feinnes’s expeditions since 1984 all point to something that should agitate us far more; that all over the world, the ice itself is rotting. The man lost fingers after hauling a sled out of polar water that shouldn’t have been water. Far from losing his already tenuous relevance, Feinnes is for many the ravaged poster child of our most contemporary crisis.

People who complain about Feinnes are rather like people who complain about us “mucking about in outer space”; they wildly over-estimate the costs involved, while wildly underestimating the value generated. Take the example of Transglobal: the expedition was put together from favours, donations and sponsorship. Careers were established in countless fields, from oceanography to biology to engineering, and 650 companies reaped the rewards of their association with the adventure.

Feinnes and his wife were unable to have children. When the couple applied to adopt a child, they were turned down because they didn’t have a stable enough income. Feinnes still struggles with money. Now a widower in his late seventies, remarried and father of one, he relies on plying the lecture circuit, driving sometimes ten hours a day to get from venue to venue, and sleeping in his car to avoid expensive bed-and-breakfasts.

Stomping through winter-time surf to ease the symptoms of suspected Parkinson’s disease, this old man is, by his own admission, still struggling to live up to his father. Pushing himself to the limit of his declining powers, he comes into focus at last as a tragic figure. But what is tragedy, if not a way of giving shape and meaning to a life that, by definition, is bound to end in decline and death?

Explorer’s achievement is to reach the source of Ranulph Feinnes’ heroism. The explorations, while staggering achievements, are mere way-stations. The goal is a life that has wrought as much good out of the world as it can.

July 27, 2022

“The idea that life is absurd bothers him”

In 2013 the oldest known human DNA was discovered, in a complex of caves in the Sierra de Atapuerca in northern Spain. It belongs to an early hominid, Homo heidelbergensis, who lived 400,000 years ago, and to whom we owe the invention of the fireplace.

Arsuaga has built an illustrious career around excavations in Atapuerca, a site humans have occupied continuously for a million years, from the dawn of Homo sapiens to the bronze age. He knows a lot about how humans evolved, and he is an eloquent communicator. “As he talked,” the novelist Juan José Millás recalls, “I realised what a great sense of the theatrical Arsuaga had. He was a master of oral storytelling. He knew when he had his audience, and when he was running the risk of losing them. He endeared himself by combining intellectual precision with a kind of helplessness.”

It’s Aruaga’s eloquence that first persuaded Millás that the two of them should collaborate on a book — a Boswellian confection in which Millás (humble, curious, a klutz, and frequently brow-beaten) follows Arsuaga around with a dictaphone capturing the great man’s observations. “In Spain,” he remarks, early on, “there are two principal periods: the first runs from the Neolithic to 1958, at which point the social planning by the Opus Dei technocrats comes in. Until then, the countryside was a place full of people, full of voices, life here was not a sad thing, there were children running around. It would be like walking down the street. By 1970, the countryside was empty, there was nobody left.”

Millás casts Arsuaga as the representative of Homo sapiens: articulate, eclectic, self-aware and tragical. Millás casts himself as Homo neanderthalis, not quite as quick on the uptake as his more successful cousin. Neanderthals are a species not exactly lost to history (Sapiens and Neanderthals interbred, after all) but no longer active in it, either.

The idea is that Arsuaga the high-brow leads our beetle-browed narrator hither and thither across northern Spain, on foot or in his trusty Nissan Juke, up lost valleys (to understand the evolution of hunting) and through deserted playgrounds (to grasp the mechanics of bipedalism), past market stalls (to grasp the historical significance of diet) and into a sex shop (to discuss the relative size of primate testicles) and building, bit by bit, a dazzling picture of the continuities that exist between our ancient and contemporary selves.

For many, the devil will be in the detail. Take, for example, Millás’s Neanderthals. He is not exactly wrong in what he says about them, but he is writing, in the most general and allusive terms, into a field that is developing frighteningly fast. It‘s hard, then, for us to know how literally to take the author’s showier gestures. Millás says, about that famous interbreeding, that “The Sapiens, being the smart ones, did it out of vice, while the Neanderthals, who were more naïve, did it out of love.” With Neanderthal intelligence and sociality a topic of so much fierce debate, such statements as this may be met with more scepticism than appreciation.

This is as much a buddy story as it is a virtuosic work of popular science. In unpacking our evolutionary past, Millas also brings his human subject to light. Arsuaga holds to the tragic view of life espoused by the fin de siecle Spanish essayist Miguel de Unamuno. Millás, a more common-or-garden depressive, finds Arsuaga’s combination of high spirits and annoyance hard to read. Deposited on the outskirts of Madrid, and half suspecting he’s been actually thrown out of Arsuaga’s Nissan, Millás realises that the palaeontologist “experiences sudden bursts of sadness that he sometimes conceals beneath an ironic demeanour, and sometimes beneath passing bad moods. I think the idea that life is absurd bothers him.”

Aruaga’s tragic sense entends to the species. We are the self-domesticating species: “To the Neanderthal,” he says, “the Sapiens must have seemed like a teddy bear.” We have evolved social complexity by shedding the adult seriousness we observe in less social mammals. (“I’ve been to Rwanda, looking at old gorillas,” says Aruaga, “and I can assure you they don’t play at all, they don’t laugh at anything.”) Over evolutionary time, we have become more playful, more infantile, more docile, and we have done this by executing, imprisoning and marginalising those who exhibit an ever-expending list of what we consider anti-social traits. So inanity will one day conquer all.

I wish Millás was a less precious writer. Very early on the pair arrive at a waterfall. “What had we come here for?” Millás writes: “in principle, to see the waterfall, and perhaps so the waterfall could see us, too.” Such unredeemable LRBisms are, I suppose, a form of protective coloration, necessary for a novelist and poet of some reputation: an earnest of his devotion to propah lirtritchah.

It’s when Millás forgets himself, and erases the distance he meant to maintain between boffins and scribblers, that Life becomes a very special book indeed: a passionate, sympathetic portrait of one life scientist’s world view.

July 12, 2022

You wouldn’t stop here for gas

Worldwide, the illegal timber trade is worth around 157 billion dollars a year. According to oral historian Lyndsie Bourgon, thirty per cent of the world’s wood trade is illegal, and around 80 per cent of all Amazonian wood harvested today is “poached” (a strange term to apply to timber, which would struggle to fit into the largest poche or pocket — but evocative nonetheless). $1 billion worth of wood is poached yearly in North America.

Bourgon focuses her account on thefts from public lands and forest parks of the Pacific North-West. There are giants here, and Methuselahs. “Old-growth” trees, more than two hundred years old, are intagliated with each others’ root systems, with fungal hyphae and with other soil systems we’ve barely begun to understand. Entire ecosystems may stand or fall on the survival of a single 800-year-old red cedar — an organism so huge it may take weeks or months to saw up and remove from the forest, leaving a trail of sawdust, felling wedges and abandoned equipment.

That the trade in such timber was not sustainable has never been a secret, and to save some of the world’s oldest and biggest trees, the Redwood National Park was established in 1968.

But while the corporations received compensation for their lost profits, the promised direct government relief for workers never materialised. “Do you know what it’s like to work 20 years, then sleep in a pick-up truck?” asked Seattle’s archbishop Thomas Murphy, at a 1994 summit attended by the new president, Bill Clinton; “A way of life is dying.”

North America’s oldest timber companies were founded near the town of Orick, on the banks of the Redwood Creek in Humboldt County, California. Orick’s first commercial sawmill opened in 1908. Orick is now home to just under 400 people. You wouldn’t stop here for gas on your way to a luxury cabin on US Forest Service land, or a heated yurt by Park Canada.

To live in Orick is to feel the walls closing in: one woodsman turned poacher, Danny Garcia, likens the sensation “to having your car break down in the middle of nowhere — you’ve no cash to fix it and no way out.”

This, says Garcia, is where his “tree troubles” started, but he wasn’t the first to go sawing chunks out of giants. His partner in crime Chris Guffie says: “I’ve been at it for so doggone long. It’s like Yogi Bear and the park ranger.”

“To begin to understand the sadness and violence of poaching,” says Bourgon, “we need to consider how a tree became something that could be stolen in the first place.” Like it or not, conservation has patrician roots: in the 1890s, organisations like the New York Sportsmen’s Club lobbied to ensure access to game and fish for its members. Dedicated hunting and fishing seasons suited their sporting clientele, but as a letter to a Wyoming paper put it: “When you say to a ranchman, ‘You can’t eat game, except in season,’ you make him a poacher, because he is neither going hungry himself nor have his family do so…”

Remove land from a community, Bourgon argues, and you make poaching “a deed of necessity”. So why not buy the land and give it back to its people, along with the tools to protect and manage it. Going by the experiences of the 59 community forests that now dot the province of British Columbia, community forests create twice as many jobs as those run by independent industry.

Of necessity, however, Bourgon spends more pages explaining the workings of a solution more palatable to central authority: an ever-more interconnected system of police surveillance, involving cameras, magnetic plates, LIDAR and, most recently, genetic testing. Even as Bourgon wrote this book, a genetic map was being assembled to make wood products, at least in the Pacific North-West, traceable to their original growing locations. The brilliance of this effort, spearheaded by Rich Cronn at the Oregon State University at Corvallis, cannot hide the fact that it is facilitating an age-old mistake: substituting enforcement for engagement.

Bourgon gives a voice both to the rangers risking their lives to save some of the planet’s oldest trees, and to poachers like Danny Garcia whose original sin was his unwillingness to leave the home of his ancestors. Full of the most varied testimonies, and by no mean fudging the issue that timber poaching is a crime and an environmental violation, Tree Thieves nonetheless testifies to the love of the woodsman for the wood. Drive through Orick sometime, and you will discover that communities are an ecology, too, and one worthy of care.

July 6, 2022

“Does it all stop at the tree?”

Watching Brian and Charles, directed by Jim Archer, for New Scientist, 6 July 2022

Amateur inventor Brian Gittins has been having a bad time. He’s painfully shy, living alone, and has become a favourite target of the town bully Eddie Tomington (Jamie Michie).

He finds some consolation in his “inventions pantry” (“a cowshed, really”), from which emerges one ludicrously misconceived invention after another. His heart is in the right place; his tricycle-powered “flying cuckoo clock”, for instance, is meant as a service to the whole village. People would simply have to look up to tell the time.

Unfortunately, Brian’s invention is already on fire.

Picking through the leavings of fly-tippers one day, the ever-manic loner finds the head of a shop mannequin — and grows still. The next day he sets about building something just for himself: a robot to keep him company as he grows ever more graceless, ever more brittle, ever more alone.

Brian Gittins sprang to life on the stand-up and vlogging circuit trodden by his creator, comedian and actor David Earl. Earl’s best known for playing Kevin Twine in Ricky Gervais’s sit-com Derek, and for smaller roles in other Gervais projects including Extras and After Life. And never mind the eight-foot tall robot: Earl’s Brian Gittins dominates this gentle, fantastical film. His every grin to camera, whenever an invention fails or misbehaves or underwhelms, is a suppressed cry of pain. His every command to his miraculous robot (“Charles Petrescu” — the robot has named himself) drips with underconfidence and a conviction of future failure. Brian is a painfully, almost unwatchably weak man. But his fortunes are about to turn.

The robot Charles (mannequin head; washing machine torso; tweeds from a Kenneth Clark documentary) also saw first light on the comedy circuit. Around 2016 Rupert Majendie, a producer who likes to play around with voice-generating software, phoned up Earl’s internet radio show (best forgotten, according to Earl; “just awful”) and the pair started riffing in character: Brian, meet Charles.

Then there were three: Earl’s fellow stand-up Chris Hayward inhabited Charles’s cardboard body; Earl played Brian, Charles’s foil and straight-man; meanwhile Majendie sat at the back of the venue (pubs and msuic venues; also London’s Soho Theatre) with his laptop, providing Charles’s voice. This is Brian and Charles’s first full-length film outing, and it was a hit with the audience at this year’s Sundance Film Festival.

In this low-budget mockumentary, directed by Jim Archer, a thunderstorm brings Brian’s robot to life. Brian wants to keep his creation all to himself. In the end, though, his irrepressible robot attracts the attention of Tomington family, his brutish and malign neighbours, who seem to have the entire valley under their thumb. Charles passes at lightning speed through all the stages of childhood (“Does it all stop at the tree?” he wonders, staring over Brian’s wall at the rainswept valleys of north Wales) and is now determined to make his own way to Honolulu — a place he’s glimpsed on a travel programme, but can never pronounce. It’s a decision that draws him Charles out from under Brian’s protection and, ineluctably, into servitude on the Tomingtons’ farm.

But the experience of bringing up Charles has changed Brian, too. He no longer feels alone. He has a stake in something now. He has, quite unwittingly, become a father. The confrontation and crisis that follow are as satisfying and tear-jerking as they are predictable.

Any robot adaptable enough to offer a human worthwhile companionship must, by definition, be considered a person, and be treated us such, or we would be no better than slave-owners. Brian is a graceless and bullying creator at first, but the more his robot proves a worthy companion, the more Brian’s behaviour matures in response. This is Margery Williams’s 1922 children’s story The Velveteen Rabbit in reverse: here, it’s not the toy that needs to become real; it’s Brian, the toy’s human owner.

And this, I think, is the exciting thing about personal robots: not that they could make our lives easier, or more convenient, but that their existence would challenge us to become better people.

July 1, 2022

“Neigh-CHURE!”

The farming crisis; for the Telegraph, 19 June 2022

It’s time for the UK to transform agriculture: to achieve levels of food security not contemplated since the Second World War; to capture fast-developing far eastern markets in meat and dairy while reducing (for reasons that are medically unclear) the amount of meat and dairy eaten at home; to achieve carbon neutrality by 2050; and to reintroduce the lynx and the wolf. All of this at once, in a manner that won’t add a further spike to people’s already spiking grocery bills, and preferably before the grain shortages triggered by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine complicate matters still further by lowering the gluten content and hence the quality of a British loaf, not to mention triggering a famine across the whole of north Africa.

Were all things equal (and they very much aren’t) we would still have a crisis on our hands. You only have to look out the window. Ninety-seven per cent of British wildflower meadows are gone, and we’re 44 million individual birds poorer than we were fifty years ago. The UK’s flying insect population has declined by about 60 per cent in the last 20 years.

This particular crisis doesn’t feel nearly as urgent as it should, thanks to what fisheries scientist Daniel Pauly has dubbed “shifting baseline syndrome” — our tendency, when we ask what nature should look like, to reference a period no more distant than our own childhoods.

It takes considerable study and real writerly skill to convey what our land should (or at any rate, could) look like, which is why Isabella Tree’s four-year-old book Wilding: The Return of Nature to a British Farm is already a classic, with its talk of species-rich wildflower meadows in every parish and coppice woods teeming with butterflies. A mere four generations ago, she writes, we knew ”rivers swimming with burbot – now extinct in Britain – and eels, and… summer nights peppered with bats and moths and glow-worms.” In those days the muddy North Sea was clear as gin, she says, filtered by oyster beds as large as Wales. “Yet we live in denial of these catastrophic losses.”

Since the publication of Feral in 2013, campaigning journalist George Monbiot has led calls to rewild our desertified and sheep-scraped landscape. He says Britain is the most zoophobic nation in Europe, and he may have a point. While even a simple beaver release here can trigger a storm of protest, on the continent reintroduced animals are extending their ranges without trouble or controversy all over mainland Europe. Bear numbers have doubled. Herds of wisent roam Dutch nature reserves. There are wolves all across Europe (and no, they don’t eat people).

Our island hang-ups are historical, according to Isabella Tree. A great many of our national myths are bound up in the idea that human habitations were hewn out of dense wildwood in ages past — in other words, we had to make a choice between a productive working landscape, or nature, but we couldn’t have both. That just-so story might explain British land use, but it has little to do with the way nature and farming actually work. Tree and the regenerative farming community argue that traditional farming and forestry practices like haymaking, pollarding and coppicing create multiple habitats, supporting a much greater variety of wildlife than closed-canopy woodland ever could, or did. According to this lobby, what we need is not a return to nature, as such, but a return to actual farming.

What we have now is not farming so much as its massively instrumentalised cousin: “agricultural production”. The supermarkets like it because they can guarantee year-round supplies of entirely uniform food products. But the price of treating farming as just another financial and engineering challenge, rather than as a biological activity has been, on the one hand, despoliation and extinction, and on the other, exhausted soils and crippling fertiliser bills.

When barrister Sarah Langford left London and began regenerating 200 acres of Suffolk land — a story told in her new book Rooted: Stories of Life, Land and a Farming Revolution — she found that forty per cent of her income was going on artificial fertiliser and sprays, and most of the rest on machinery, diesel and labour. Her few thousand pounds of profit a year is typical for the industry.

Farmers really do live on government subsidies, because actually producing food loses more money than it makes. A third of the country’s farmers would be bankrupt without basic payments. What they have been asked to do since the end of the Second World War — overproduce food — is destroying the world, and they are the ones left carrying the can. Farming is bad for the soil, bad for the planet, bad for the climate, bad for our waistlines, bad for our health! Meanwhile farmers are going to the wall, abandoning the land, and choosing death as a way out of debt: more than one farm worker in the UK takes their own life each week.

In Sarah Langford’s book, her response to this dire state of things — to attempt not just to farm her land, but to regenerate it — sets her at loggerheads with her Uncle Charlie, an experienced Hampshire farmer. The irascible Charlie and his mates (“Nature!” they tease poor Sarah, “NEIGH-CHURE!”) form an entertaining and sceptical chorus to Langford’s efforts at sustainable farming — a career change she did not plan, but which was more or less forced on her by a temporary snag in the family finances followed by a whopping fire.

Langford’s book is full of telling detail, as when, while applying for a five-year Countryside Stewardship scheme, on a form 123 pages long, and referring to a manual 312 pages long, she discovers that she still has to fill in the Basic Payment form, which has completely different set of codes for each option. But Rooted is more than a memoir; Langford manages to contain and convey the whole scale of the coming agricultural revolution.

Our current food system evolved out of a dangerous assumption that all the world’s bounty lay a mere sea-voyage away. The Second World War put paid to that fond notion, and the experience of importing 20 million tons of food a year in the teeth of U-boat attacks inspired the 1947 Agriculture Act. Its framework of government subsidies and guaranteed prices may sound a bad idea now; back then there was an economic recovery to pay for and a food supply to secure.

The Act, and similarly intentioned legislation elsewhere in the world, worked a treat. Langford tells us that the first journal article to warn of growing levels of food waste was published in 1980, just 25 years after the abolition of rationing. Today the world produces 1.7 times as much food as it did in 1960, on about a third of the land. The only problem being, this is more food than we need — enough to feed three billion people who don’t exist yet. Globally, we throw away 2.5 billion tonnes of food every year, while eating just 40 per cent of all the food we produce. In the UK a full third of all fruits and vegetables bound for the supermarkets are rejected.

Those of us who live amidst relative plenty tend to prioritise the environmental issues this raises over the ones about distribution and equity. But heaven knows the environmental issues are serious enough, witness the major declines in over half our nation’s species since 2002. Whoever would have imagined that we would ever risk running out of dormice, or water voles, or hedgehogs?

The overwhelmingly urban lobby that would blame farming for these ills finds its champion in campaigning environmental journalist George Monbiot. For them, Monbiot’s latest, Regenesis, bears good tidings — nothing less than “the beginning of the end of most agriculture.”

Monbiot introduces us a soil bacterium studied by scientists working for NASA in the 1960s. He explains how, though fermentation, we can cultivate this bacterium. Once dried, it can be turned into a cheap protein-rich flour. This flour could feed the world, in a production process that consumes no more energy than any cash-strapped developing country could afford through solar power, and which requires 17,000 times less land than you’d need to produce the same amount of, say, soybean protein.

To the 98.5 per cent of us in this country who have no working connection to the land, Monbiot’s Rousseauist future sounds too good to be true. All things being equal, who wouldn’t want to see Britain smothered in wildwood stalked by beavers, bears and pine martens?

But history is not kind to “hero projects” of this sort, and Monbiot’s breathless conjurations of the future of the food that would emerge from farming’s demise are somewhat disconcerting. A morsel that tastes like seared steak but with the texture of scallops? A mousse that breaks on the tongue like panna cotta but has the flavour of jamon iberico? All whipped up in some lab, apparently, by “inventive chefs working with scientists”.

Actually, to swap breweries for barns wouldn’t be particularly science fictional: fermentation is a practice older than farming. But for Monbiot to mix an argument about largely untested technologies with a diatribe against Welsh sheep farming (yes, Monbiot is worrying the sheep again) smacks of bad faith.

In his superbly acerbic diary Land of Milk and Honey: Digressions of a Rural Dissident, columnist and cattle farmer Jamie Blackett is out to defend, not farming as it is (which he frankly considers a nightmare — there is less distance between Blackett and Monbiot than you might expect) but farming as it was practised in his father’s day. By yesterday’s pre-CAP logic, it makes sense to mix livestock and arable, and even to focus entirely on livestock and dairy in the UK where the climate dictates that grass is the best crop to grow (and sometimes the only one).

Blackett, citing the huge margins involved in turning cheap vegetable oils, sugars and carbohydrates into fake meats and fake milk, reckons veganism is the best thing that ever happened to the processed food industry since Cadbury’s stuck their Finger of Fudge up at the very concept of the balanced diet. He complains that “without the ability to grow meat and milk the only solution is to plant the land up with trees and go and do something else for thirty years while they grow” — which is, of course, precisely what Monbiot is advocating in Regenesis.

But need the debate about the future of farming be so polarised? The popular response to the Amazon Prime’s TV show Clarkson’s Farm — surely the unlikeliest of vehicles Jeremy Clarkson has ever ridden — suggests we might not be so short of goodwill, after all. And the legislative framework that’s being assembled post-Brexit at least holds out the possibility of real and positive change for the British countryside.

Anyone who thinks Brexit caught British agricultural thinking by surprise hasn’t been paying attention. The 2020 Agriculture Act is the largest shift in farm and rural policy since the UK joined the Common Agricultural Policy in 1973. In England, the old subsidy payments will be phased out by 2028, replaced by a new Environmental Land Management System which will reward farmers with public money for producing “public goods”. Conservation manager Jake Feinnes lists them in his book Land Healer: “clean, plentiful water, clean air, thriving plants and wildlife, a reduction in and prevention of environmental hazards, adaptation to and mitigation of climate change” and “‘beauty, heritage and engagement with the environment’.”

Can this act change, fast enough for it to matter, a governing culture that has spent three quarters of a century micromanaging British agriculture into its current, monstrous form? Having been encouraged (and not just encouraged — forced) to squeeze every last calorie they can from their ever-more blighted patrimony, are farmers likely to embrace the government’s green new deal?

Blackett is sceptical. “For the last twenty years,” he writes, “I have been receiving payments for hedges, ponds, rushy pasture, water margins, wild-flower meadows and winter stubbles. The payments have been miserly, never quite enough to compensate… The final straw came when I was made to keep a diary like a primary school child. I have come to the conclusion that it is better to farm for maximum profit and use any surplus for conservation on my land than to be a poorly paid serf of the Green State.”

For Blackett, whether or not Defra’s ideas are well-intentioned or not is beside the point. The road to Hell is paved with good intentions. He’d rather farmers were left alone to exercise their own judgement, and then “there will be more biodiversity, fewer wildfires and less greenhouse gas in consequence, for the benefit of us all.”

Oddly — in light of the specious battle lines George Monbiot draws between conservationists and working farmers — Blackett’s irascible anti-state-interference rhetoric finds a very close echo in Birds, Beasts and Bedlam, a wonderfully garrulous memoir by Derek Gow, an outspoken champion of rewilding, responsible for the reintroduction of beavers and white storks into the UK. At first glance, Gow comes across as a sort of anti-Blackett, and yet he has nothing but praise for British farmers, a “hearty culture where if you helped your neighbours, they helped you”. This, he reckons, is about as far as you can get “from the egotistical and odd world of nature conservation where big stories were talked and small deeds were done.”

Gow’s rewilding efforts are frustrated less by farmers (who are a curious bunch at heart, and can follow an argument) as by conversation charities themselves (“small, grey non-entities standing together on a dias”). “If you wish to bludgeon badgers,” Gow writes, “a way can be found. If you wish, on the other hand, to restore fading species for nature conservation purposes, then you have to fill in 90-page documents which will be thoroughly scrutinised eventually and returned to you with a further suite of impossibly complex questions.”

Independent spirits like Gow and Blackett desperately need a venue in which they can thrash out their opinions and share their knowledge. And it may be that a culture of regenerative farming will encourage that much-needed exchange.

On Great Farm in north Norfolk, Jake Fiennes has made some small changes that allow the land to remain in food production, but which also allow nature to thrive. His particular hobby horse is the soil, and all the ways he has found to enhance the relationship between his crops and the bacteria and fungi in his soil, so as to reduce the amount of manure and fertiliser he uses, even while increasing yields.

Fiennes’s brand of regenerative farming (and others — there are as many innovative farming techniques as there are innovative farmers) promises to restore crashing mammal, bird and insect populations, make the landscape better able to survive droughts and floods, lock away carbon as organic matter, and still produce high quality food. The soil science is new (and startling: it turns out that plant roots exude chemicals as nourishment for microbes, and up to 96 per cent of carbon a plant processes is used to feed soil and fungi). But the takeaway is as old as the hills: rotate your crops, keep the ground covered as much as you can, ensure a mixed environment and a healthy hedgerow so your predators cancel out your pests. The detail is fascinating, but at the sharp end of the business, “regenerative farming” is less about having ideas than about ignoring, as far as possible, the present market’s more perverse incentives.

Fiennes skewers such absurdities very well. For instance, under CAP farmers were paid to set aside ten per of their land to discourage overproduction. They just needed to keep their land in “agricultural condition”. Soon near-destitute farmers were filling in ponds, ripping out wide hedgerows, straightening the meanders of streams and chopping down woodland so as to turn ‘permanent ineligible features’ into set-aside.

For all the anxiety washing about the agriculture sector, there are signs — strong signs — of promise. We need a decent amount of food security, and we have it; though Britain currently produces less than 60 per cent of its own food, the Dimbleby report, the first independent survey of the British food system in 75 years, suggests that 74 per cent of our food could be sourced at home — a figure considered excellent for food security. We need a sensible tariff system to defend our agricultural sector during its transformation from CAP’s culture of over-production and set-aside, to the provision of public environmental goods. World Trade Organisation rules allow for exactly this. And, funnily enough, farmers know how to farm; at very worst, the next generation now has reason to remember and learn.

Novice farmer Sarah Langford, the novice regenerative farmer, bemoans her feeling “of muddling around in the half-light of knowledge”. She says she sees “how easy it is to think you’re doing the right thing while causing harm.”

Her point is that farming is hard to do. Hard — but not impossible. And it’s a task made immeasurably easier, once farmers are given the freedom to remember who they are.

June 29, 2022

Making waves

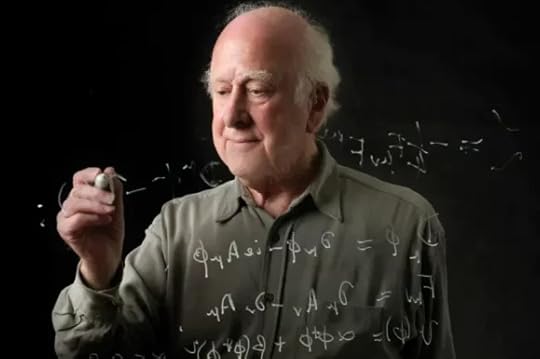

In Elusive, physicist Frank Close sets out to write about Peter Higgs, whose belief in the detectability of a very special particle that was to bear his name earned him a Nobel prize in 2013.

But Higgs’s life resists narrative. He has had a successful career. His colleagues enjoy his company. He didn’t over-publish, or get into pointless spats. Now in his mid-nineties, Higgs keeps his own counsel and doesn’t use email.

So that left Close with writing a biography, not of the man, but of “his” particle, the Higgs boson – and with answering some important questions. How do we explain fundamental forces so limited in their reach, they cannot reach outside the nucleus of an atom? Why is this explanation compelling enough that we entertained its outrageous implication: that there existed a fundamental field everywhere in the universe, a sort of aether, that we could not detect? Why did this idea occur to six thinkers, independently, in 1964? And how did it justify the cool €10 billion it took to hunt for the particle that this wholly conjectural field predicted?

To understand, let’s start with our universe. Forget solid matter for a moment. Think instead of fields. The universe is full of them, and when we put energy into these fields it’s as though we dropped a stone into a lake – we make waves. In this analogy, you are also in the lake: there is no shore, no “outside” from which you can see the whole wave. Instead, as the wave passes through a point in space, you will notice a change in some value at that point.

These changes show up as particles. Light, for example, is a wave in the electromagnetic field, yet when we observe the effect that wave has on a point in space, we detect a particle – a photon.

Some waves are easier to make than others, and travel farther. Photons travel outwards as fast as the universe allows. Gravitational waves are as fast, but decay sharply with distance.

The mathematics used to model such fields makes a kind of sense. But we also need a mathematics to explain why the other fields we know about are infinitesimally small, extending no farther than the dimensions of the atomic nucleus.

For the mathematics to work for such small fields, it requires another, more mysterious, infinite field: one that doesn’t decay with distance, and that always has a value greater than zero. This field interacts with everything bar light. If you are a photon, you get to zip along at the universal speed limit. But if you are anything else, this additional field slows you down.

We call the effect of this field mass. Photons are massless, so travel very quickly, while everything else has some amount of mass, and consequently travels more slowly. It is easy to set the electromagnetic field trembling – just light a match. To set off a wave in the mass-generating field, however, takes much more energy.

In 1998, CERN began work on its Large Hadron Collider (LHC), a 27-kilometre-long particle accelerator 100 metres under the French-Swiss border. On 4 July 2012, a particle collision in the LHC released such phenomenal energy that it set off a mass-generating wave. As this wave passed through the machine’s detectors a new particle was observed. In detecting this particle, physicists confirmed the existence of the mass-generating field – and our present model of how the universe works (the standard model of particle physics) was completed.

Both of Close’s subjects, Peter Higgs and his particle, prove elusive in the end. Newcomers should start their journey of discovery elsewhere – perhaps with Sean Carroll’s excellent webinars and books.

But Close, and this difficult, brilliant book, will be waiting, smiling, at the end of the road.

June 8, 2022

What the fuck was THAT?

Watching Joseph Kosinski’s Top Gun: Maverick, for New Scientist, 8 June 2022

Near the climax of Joseph Kosinski’s delirious sequel to 1986 hit Top Gun, a fifth-generation fighter engages Pete “Maverick” Mitchell’s F/A-18 in a dogfight around vertiginous snow-capped mountains. Suddenly this huge, hulking, superpowered wonderplane banks, stalls and turns, hanging over Mav (Tom Cruise, even more steely-eyed than usual) and his wingman Rooster (Miles Teller) as though it’s painted itself on the sky.

“What the ____ was THAT?” Rooster cries, though an actual graduate of TOPGUN (official name, the Navy Strike Fighter Tactics Instructor program) would probably know a Herbst manoeuvre when they saw one.

The Herbst (also known as a J-turn) is the kind of acrobatic manoeuvre you can pull only if you’re flying one of a handful of very expensive fighters designed and built since 2010. The Russian Sukhoi Su-57 is one such; China has the Chengdu J-20.

We’re not told which aircraft — or indeed, what well-provisioned rogue state — Mav is up against here, but he is in trouble: his F/A-18 multirole combat jet is no slouch, but, being a child of the 1990s, it is neither super-stealthy nor supermanoeuvrable.

“Fifth-gens” are not the only nemesis Mav must confront. He’s also holding out against progress, personified by a rear admiral nicknamed the Drone Ranger who (in a splendidly sour cameo by Ed Harris) declares that drones are the future, and that carrier-based fighter pilots like Mav are dinosaurs.

Most of the time, however, Maverick steers clear of ideas, and devotes itself wholly to 1980s nostalgia, as Tom Cruise’s Pete Mitchell (now a test pilot) sets about making his peace with the orphaned son of his old wingman Nick “Goose” Bradshaw. This is a well-told tale of misunderstanding and redemption, interspersed throughout with one-liners and easter eggs for fans of the earlier film. In one touching and funny scene, Mav gets to thank Ice (now, God help us all, commander of the U.S. Pacific fleet) for keeping him in fighter planes and out of promotion. Of Kelly McGillis’s Charlie, Mav’s love interest in the first movie, there is no mention — but not every storyline can look back, and in this film, Mav’s old flame Penny Benjamin (Jennifer Connelly) proves no pushover.

This is a peculiar project: part war film (as our heroes steal a plane from under the noses of the enemy), part techno-thriller (as Mav the test-pilot breaks all speed records and reaches an insane 3.5km a second), and part sports movie (as Mav welds his brilliant TOPGUN pupils into a world-peace-saving team; by that measure, mind you, you could argue that all Hollywood blockbusters are sports movies at heart).

Films can be good fun-fair rides quite as much as they can be good dramas, and it would be silly to criticise this thrilling display of real-world aeronautical stunt work for its lack of narrative realism. The presence of real planes and real pilots (and, after three months’ training, real airborne cast-members) makes this, in a profound sense, about as realistic a film as it is possible to get.

What we might look forward to eventually, though, is a film that looks for excitement, peril and heroism in a more contemporary theatre, featuring aerial combat that’s truly fifth-generation: super-stealthy, super-manoeuvreable, and drone-enhanced.

Until someone makes that imaginative leap (and, crucially, can take a huge global audience along for the ride), we can expect armed-forces movies to draw more and more on science fiction for their plots. Why is the pilot dog-fighting with Mav and Rooster dressed like an Imperial TIE-fighter pilot from Star Wars? Why is the illegal uranium enrichment plant that’s the target of Mav’s raid equipped with a two-metre wide exhaust vent lifted from Star Wars’s Death Star? Because this is what science fiction is, much of the time: a filler, a place-holder, a hoarding that reads, “Coming soon: the future”.

Simon Ings's Blog

- Simon Ings's profile

- 147 followers