Roland Kelts's Blog, page 55

July 29, 2012

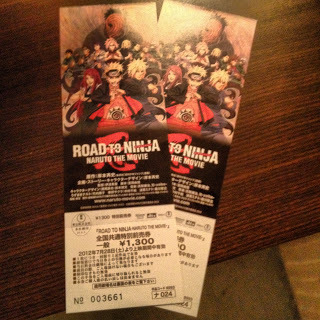

Latest NARUTO film triples previous opening numbers

The latest Naruto feature film, "Road to Ninja," has reportedly tripled opening weekend attendance records set by the last release in Japan, according to studio sources. [Opening tix above courtesy of Nunokawa-san & Pierrot.]

Published on July 29, 2012 23:25

July 19, 2012

Slide down Ayanami Rei in Tokyo this summer ...

Published on July 19, 2012 06:20

July 18, 2012

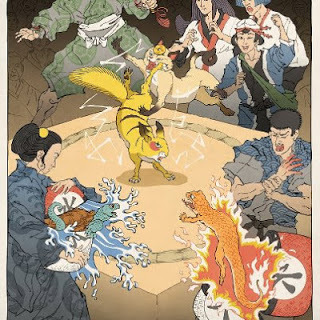

Pokemon, Ukiyo-e style

Published on July 18, 2012 09:05

July 16, 2012

Monkey Business gets ink in Japan

Published on July 16, 2012 09:15

July 13, 2012

PUNCH, coming soon; my latest included

Punch Launches Third iPad Issue

By ERIK MAZA

COMMENTS 0

A- A A+

MOST RECENT ARTICLES ON MEMO PAD

Challenges Releases List of France's Top 500 Fortunes

Mila Kunis Appears in Second Dior Campaign

Lord & Taylor Sponsoring 'Project Runway'

MORE ARTICLES BY

Erik Maza

In June, Punch, an iPad magazine — appazine, if we must — uploaded a video to its app and YouTube simultaneously.

Called “32 and Pregnant,” it was a parody of MTV’s “16 and Pregnant” and also Brooklynites’ parenting anxieties — the plight of too-small closets, insurance plans that won’t cover home births, the frightening prospect of not getting your kid into a solid pre-K program.

“I give up,” says an exasperated mother, tears streaming down her face. “Look at me,” her husband screams at her. “It’s TV, then satellite, then you can change the channel.” The video got picked up by a couple of blogs, and it became, surprisingly, Punch’s most popular video since its launch in April, with nearly 120,000 page views.

It was an unexpected hit because the video came during the iPad start-up’s mitochondrial stage. Jim Windolf, the Vanity Fair contributing editor and former New York Observer veteran, had just joined as editor in chief and was beginning to cobble together ideas.

With his second issue, which went up earlier this week, the magazine’s plans are finally coming into focus. Windolf says they’ll now be uploading new material every other Tuesday. And he’s locked down several regular contributors — humorist and former “Late Show With David Letterman” head writer Merrill Markoe and former Observer columnist George Gurley, among them.

Punch is one of several publishers trying to break through on tablets, where there’s been only mild success. The Daily, News Corp.’s heavily-funded iPad newspaper, signed up 80,000 paying subscribers through last October — its publisher Greg Clayman told Ad Age — a number that’s not enough to keep it from bleeding buckets of cash, anywhere from $30 million to $60 million, according to several estimates. Recently, there’s been speculation that its future is uncertain. Daily editor Jesse Angelo did not respond to requests for comment.

The Huffington Post also has skin in the game, having recently launched Huffington magazine. But it’s not saying how the new app is faring. “We don’t publicize our download numbers,” said a spokesman.

The stakes for Punch are much smaller. It’s coming up now on 10,000 downloads, Windolf says, and the free app makes its money through advertising.

Windolf joined Punch in April, after the start-up had already been in development for over a year. It was conceived by former Radar editor Maer Roshan and David Bennahum between spitballing sessions for an iPad-only magazine covering pop and political culture, the founders told Capital New York earlier this year. Bennahum, who is now Punch chief executive officer, is a new media kibitzer — he was involved in the launches of Mediabistro and the Daily Candy newsletter — and he was able to raise $2.25 million in investor capital to get Punch off the ground.

For the first issue, released April 12, the founders put up several pieces, but after that, “the bank was empty,” Windolf says. He came on board after Roshan had moved on to concentrate on The Fix, the Web site he founded to cover the addiction and recovery industry that he has since left, he says, to write a book. Windolf’s first task was to scout up-and-coming writers and comics, and assign pieces to get the app ready for a regular publication schedule, a lengthy process that didn’t bear fruit until June.

That’s when “32 and Pregnant,” by filmmaker Chioke Nassor, went up, along with what Windolf calls an “unhinged essay” on Mitt Romney’s Mormonism and a new quiz. Now, Windolf says the pieces are in place to keep up with weekly updates following a similar template — typically a text-heavy piece, a video short and a handful of games.

Markoe will be doing a monthly video, and Nassor will be doing two a month. Besides Gurley, who has a piece coming in August, “Japanamerica” author Roland Kelts and humorist Mike Sacks are working on material. Drew Friedman, an illustrator whose work has appeared in the Observer and the New Yorker, is also working on a piece.

Windolf’s Punch is partly influenced by Spy. There are quizzes and many imperceptible details in bigger pieces, two Spy hallmarks. In the most recent issue, “Tiny Pundits,” a send-up of political talk shows acted out by a group of girls, has a running news scroll in small caps: “Thomas Pynchon to appear on ‘The View,’” “Mayor Bloomberg glances askance at coffee.”

In Spy, you’d have “investigative journalism that was also funny” and so Punch has a history of early, pre-Internet viral culture.

But there’s also material that might appear on Funny or Die and Comedy Central — like a fake North Korea campaign commercial, and a supercut of guests who tried to leave “The Daily Show” too early.

The videos have resonated with those sites, and some have recently partnered with Punch to cross-publish pieces. The Awl carried “Viral Culture,” and Politico and Comedy Central’s Indecision site picked up “Tiny Pundits.”

“We’re trying to get the word out because nobody’s heard of us,” Windolf says.

Those partnerships have resulted in Punch’s biggest hits, but, encouragingly, some of the longer pieces, like the Mormonism essay, have overperformed, too, Windolf says.

“It shows people can come to the iPad, and also, it seems, have the patience to read an article,” he says. “We’re creating this atmosphere that people can go into and lose themselves in.”

Published on July 13, 2012 09:45

July 7, 2012

Sailor Moon?

Redux: http://www.animenewsnetwork.com/news/2012-07-06/sailor-moon-manga-gets-new-anime-in-summer-2013

Published on July 07, 2012 07:11

July 6, 2012

'Who's here'--latest travel column for Paper Sky

The digital audio file is 18 minutes and 11 seconds long. My parents are talking to a surgeon in Boston about my father’s upcoming heart surgery. The surgeon is frank, his voice high-pitched but firm. He uses words like “death,” “failure,” and “serious stuff.” My parents splutter a bit at first, tentatively asking questions that amount to one unspoken plea: Is there any way out of this?

Four percent chance of death with surgery, is the answer. Much higher without it.

My father’s aortic aneurysm was discovered two years ago, when he passed out on a sofa after breakfast. He was rushed to the hospital, had an MRI and CAT scan, and was back home after a week. His aorta had swelled, but not yet to critical levels.

The critical came this year, when his aneurysm swelled from 5.3 inches to 5.6. “It’s the line in the sand,” said the surgeon through my laptop speakers. “We’ve just crossed it.”

I liked how he said the word ‘we,’ though I didn’t yet trust him. I didn’t trust anyone with my father’s body, his life.

The audio file arrived courtesy of my younger sister, who had purchased a digital recorder and had it sent to our parents via Amazon prior to the appointment so that the two of us, she in New York and I in Tokyo, could keep tabs on the stranger who would cut our father open.

We both listened to it in our respective cities and conferred via telephone. One night, one of us (probably me) went watery with emotion. We have been blessed by a father who sacrificed so much to raise us, and now he might die in a sterile room encased in brick.

Everyone deals with this, my close friends said. Your parents die. You can’t prepare.

But you do try, however numbly, to wrestle the unacceptable into a reality.

There are calls, emails, taps on the shoulder we all dread. For me, my mother’s email announcing my father’s appointment for surgery this spring slid into that queasy domain. Boston’s Mass General is a big hospital in the US and one of the most famous in the world. Appointments are made arbitrarily, helicopters airlift accident victims in urgent need. The near-dead are sometimes quelled and revived amid skewed schedules.

My mother’s email was last-minute, but reasonable compared to what the hospital manages on a daily basis. Still, I had only five days to book a flight from Tokyo to Boston, and no idea when I could, should or would be able book a return.

The email arrived late on a Saturday night in Tokyo; I began phoning airlines on Sunday morning.

By Friday, I was back in the tunnel of trans-Pacific travel, typing empty words onto my tablet screens, rising to piss, stretch and stare at the wall, and pondering my arrival in Boston—not for a talk, book-signing or holiday, but to see if my father might survive.

The English word, ‘travel,’ conjures romantic notions—journey, pilgrimage, leisure and escape. But traveling from Tokyo to Boston and back when you don’t want to, didn’t plan to do so, and are not being paid for the duress, is as flat and rough as sandpaper. It looks plain, and it hurts.

I have flown from Tokyo to the US so many times that the experience has become a shade less than mundane. Boarding a bus offers more possibilities. My unconscious rituals of behavior—vitamin-rich drinks I choose at specific intervals en route, sleep postures and stretch schedules—would bore even a seasoned tourist.

But this time, I strayed. I couldn’t focus on work, reading, movies, TV shows, flight attendants or even a friend who serendipitously greeted me near the toilets. I heard but couldn’t listen to what he said. I wasn’t thinking about my father, really, or the arrival at Logan in Boston, or the following weeks of anxiety and vulnerability. I wasn’t thinking at all, and so when I saw Alaska expand in deep whites below the wing porthole, I felt a sense of comfort.

Snow. Ah. I was raised in it.

A connecting flight was inevitable in my last-minute itinerary. My flight out of Detroit was delayed by two hours. A pilot from the same airline sat next to me and regaled me with critiques of his own employer. He asked me why I was making the trip.

“My father is dying,” I said.

“Aren’t we all.”

My weeks in Boston this spring were as troubling as I knew they would be, but I still can’t find a way I could have prepared for them. Dad didn’t die; he’s recovering as I write now, and I caught my return flight to Tokyo, only to fly back to NYC for work a couple of weeks later.

Blessed. I was in Kyoto last week; I will be in New York next week, and in China thereafter for work. My father is alive, limping along, and his sagging face cupped in my hands is a luxury now.

Still, the worries remain, the odd anxieties over being so close and so far at once, and the utter finality of enormous death. I did what I had to do, and no one has chastised me.

Flying around the world on a dime once sounded cool, didn’t it?

Our sense of travel evolves as we do, and its evolution is shaped by our needs, values and fears. I think I’m most afraid of learning what many in Japan learned last year—that an entire population can be destroyed in one instant, and that one of them might be among your beloved.

The digital recording of my parents querying their surgeon is a kind of found poetry to me now, a simple litany of lines about what will happen, what must happen, and what might occur.

The dying tell us to value life. So simple.

On a plane, I am always in between. I land somewhere and am here, in Tokyo, in New York, in Los Angeles, London or Boston.

But what matters now is this: Who is here with me?

Four percent chance of death with surgery, is the answer. Much higher without it.

My father’s aortic aneurysm was discovered two years ago, when he passed out on a sofa after breakfast. He was rushed to the hospital, had an MRI and CAT scan, and was back home after a week. His aorta had swelled, but not yet to critical levels.

The critical came this year, when his aneurysm swelled from 5.3 inches to 5.6. “It’s the line in the sand,” said the surgeon through my laptop speakers. “We’ve just crossed it.”

I liked how he said the word ‘we,’ though I didn’t yet trust him. I didn’t trust anyone with my father’s body, his life.

The audio file arrived courtesy of my younger sister, who had purchased a digital recorder and had it sent to our parents via Amazon prior to the appointment so that the two of us, she in New York and I in Tokyo, could keep tabs on the stranger who would cut our father open.

We both listened to it in our respective cities and conferred via telephone. One night, one of us (probably me) went watery with emotion. We have been blessed by a father who sacrificed so much to raise us, and now he might die in a sterile room encased in brick.

Everyone deals with this, my close friends said. Your parents die. You can’t prepare.

But you do try, however numbly, to wrestle the unacceptable into a reality.

There are calls, emails, taps on the shoulder we all dread. For me, my mother’s email announcing my father’s appointment for surgery this spring slid into that queasy domain. Boston’s Mass General is a big hospital in the US and one of the most famous in the world. Appointments are made arbitrarily, helicopters airlift accident victims in urgent need. The near-dead are sometimes quelled and revived amid skewed schedules.

My mother’s email was last-minute, but reasonable compared to what the hospital manages on a daily basis. Still, I had only five days to book a flight from Tokyo to Boston, and no idea when I could, should or would be able book a return.

The email arrived late on a Saturday night in Tokyo; I began phoning airlines on Sunday morning.

By Friday, I was back in the tunnel of trans-Pacific travel, typing empty words onto my tablet screens, rising to piss, stretch and stare at the wall, and pondering my arrival in Boston—not for a talk, book-signing or holiday, but to see if my father might survive.

The English word, ‘travel,’ conjures romantic notions—journey, pilgrimage, leisure and escape. But traveling from Tokyo to Boston and back when you don’t want to, didn’t plan to do so, and are not being paid for the duress, is as flat and rough as sandpaper. It looks plain, and it hurts.

I have flown from Tokyo to the US so many times that the experience has become a shade less than mundane. Boarding a bus offers more possibilities. My unconscious rituals of behavior—vitamin-rich drinks I choose at specific intervals en route, sleep postures and stretch schedules—would bore even a seasoned tourist.

But this time, I strayed. I couldn’t focus on work, reading, movies, TV shows, flight attendants or even a friend who serendipitously greeted me near the toilets. I heard but couldn’t listen to what he said. I wasn’t thinking about my father, really, or the arrival at Logan in Boston, or the following weeks of anxiety and vulnerability. I wasn’t thinking at all, and so when I saw Alaska expand in deep whites below the wing porthole, I felt a sense of comfort.

Snow. Ah. I was raised in it.

A connecting flight was inevitable in my last-minute itinerary. My flight out of Detroit was delayed by two hours. A pilot from the same airline sat next to me and regaled me with critiques of his own employer. He asked me why I was making the trip.

“My father is dying,” I said.

“Aren’t we all.”

My weeks in Boston this spring were as troubling as I knew they would be, but I still can’t find a way I could have prepared for them. Dad didn’t die; he’s recovering as I write now, and I caught my return flight to Tokyo, only to fly back to NYC for work a couple of weeks later.

Blessed. I was in Kyoto last week; I will be in New York next week, and in China thereafter for work. My father is alive, limping along, and his sagging face cupped in my hands is a luxury now.

Still, the worries remain, the odd anxieties over being so close and so far at once, and the utter finality of enormous death. I did what I had to do, and no one has chastised me.

Flying around the world on a dime once sounded cool, didn’t it?

Our sense of travel evolves as we do, and its evolution is shaped by our needs, values and fears. I think I’m most afraid of learning what many in Japan learned last year—that an entire population can be destroyed in one instant, and that one of them might be among your beloved.

The digital recording of my parents querying their surgeon is a kind of found poetry to me now, a simple litany of lines about what will happen, what must happen, and what might occur.

The dying tell us to value life. So simple.

On a plane, I am always in between. I land somewhere and am here, in Tokyo, in New York, in Los Angeles, London or Boston.

But what matters now is this: Who is here with me?

Published on July 06, 2012 06:46

Who's Here--latest column for Paper Sky

The digital audio file is 18 minutes and 11 seconds long. My parents are talking to a surgeon in Boston about my father’s upcoming heart surgery. The surgeon is frank, his voice high-pitched but firm. He uses words like “death,” “failure,” and “serious stuff.” My parents splutter a bit at first, tentatively asking questions that amount to one unspoken plea: Is there any way out of this?

Four percent chance of death with surgery, is the answer. Much higher without it.

My father’s aortic aneurysm was discovered two years ago, when he passed out on a sofa after breakfast. He was rushed to the hospital, had an MRI and CAT scan, and was back home after a week. His aorta had swelled, but not yet to critical levels.

The critical came this year, when the aneurysm swelled from 5.3 inches to 5.6. “It’s the line in the sand,” said the surgeon through my laptop speakers. “We’ve just crossed it.”

I liked how he said the word ‘we,’ though I didn’t yet trust him. I didn’t trust anyone with my father’s body, his life.

The audio file arrived courtesy of my younger sister, who had a digital recorder sent to our parents via Amazon prior to the appointment so that the two of us, she in New York and I in Tokyo, could keep tabs on the stranger who might cut our father open.

We both listened to it in our respective cities and conferred via telephone. One night, one of us (probably me) went watery with emotion. We have been blessed by a father who sacrificed so much to raise us, and now he might die in a sterile room encased in brick.

Everyone deals with this, my close friends said. Your parents die. You can’t prepare.

But you do try, however numbly, to wrestle the unacceptable into a reality.

There are calls, emails, taps on the shoulder we all dread. For me, my mother’s email announcing my father’s appointment for surgery this spring slid into that queasy domain. Boston’s Mass General is a big hospital in the US and one of the most famous in the world. Appointments are made arbitrarily, helicopters airlift accident victims in urgent need. The near-dead are sometimes quelled and revived amid skewed schedules.

My mother’s email was last-minute, but reasonable compared to what the hospital manages on a daily basis. Still, I had only five days to book a flight from Tokyo to Boston, and no idea when I could, should or would be able book a return. The email arrived late on a Saturday night in Tokyo; I began phoning airlines on Sunday morning.

By Friday, I was back in the tunnel of trans-Pacific travel, typing empty words onto my tablet screens, rising to piss, stretch and stare at the wall, and pondering my arrival in Boston—not for an appearance or book signing, but to see if my father might survive.

The English word, ‘travel,’ conjures romantic notions—journey, pilgrimage, leisure and escape. But traveling from Tokyo to Boston and back when you don’t want to, didn’t plan to do so, and are not being paid for the duress, is as flat and rough as sandpaper. It looks plain, and it hurts.

I have flown from Tokyo to the US so many times that the experience has become a shade less than mundane. Boarding a bus offers more possibilities. My unconscious rituals of behavior—vitamin-rich drinks I choose at specific intervals en route, sleep postures and stretch schedules—would bore even a seasoned tourist.

But this time, I strayed. I couldn’t focus on work, movies, TV shows, flight attendants or even a friend who serendipitously greeted me near the toilets. I heard but couldn’t listen to what he said. I wasn’t thinking about my father, really, or the arrival at Logan in Boston, or the following weeks of anxiety and vulnerability. I wasn’t thinking at all, and so when I saw Alaska expand in deep whites below the wing porthole, I felt a sense of relief.

Snow. Ah. I was raised in snowy norths.

A connecting flight was inevitable in my last-minute itineraries. My flight out of Detroit was delayed by two hours. A pilot from the same airline sat next to me and regaled me with critiques of his own employer. He asked me why I was making the trip.

“My father is dying,” I said.

“Aren’t we all.”

My weeks in Boston this spring were as troubling as I knew they would be, but I still can’t find a way I could have prepared for them. Dad didn’t die; he’s recovering as I write now, and I caught my return flight to Tokyo, only to fly back to NYC for work a couple of weeks later.

Blessed. I was in Kyoto last week; I will be in New York next week, and in China thereafter for work. My father is alive, limping along, and his sagging face cupped in my hands is a now a luxury.

Still, the worries remain, the odd anxieties over being so close and so far at once, and the utter finality of enormous death. I did what I had to do, and no one has chastised me.

Flying around the world on a dime once sounded cool, didn’t it?

Our sense of travel evolves as we do, and its evolution is shaped by our needs, values and fears. I think I’m most afraid of learning what many in Japan learned last year—that an entire population can be destroyed in one instant, and that one of them might be among your beloved.

The digital recording of my parents querying their surgeon is a kind of poetry to me now, a simple account of lines about what will happen, what must happen, and what might occur.

The dying tell us to value life. So simple. On a plane, I am always in between. I am here, in Tokyo, in New York, in Los Angeles, London or Boston.

But what matters now is this: Who is here with me?

Four percent chance of death with surgery, is the answer. Much higher without it.

My father’s aortic aneurysm was discovered two years ago, when he passed out on a sofa after breakfast. He was rushed to the hospital, had an MRI and CAT scan, and was back home after a week. His aorta had swelled, but not yet to critical levels.

The critical came this year, when the aneurysm swelled from 5.3 inches to 5.6. “It’s the line in the sand,” said the surgeon through my laptop speakers. “We’ve just crossed it.”

I liked how he said the word ‘we,’ though I didn’t yet trust him. I didn’t trust anyone with my father’s body, his life.

The audio file arrived courtesy of my younger sister, who had a digital recorder sent to our parents via Amazon prior to the appointment so that the two of us, she in New York and I in Tokyo, could keep tabs on the stranger who might cut our father open.

We both listened to it in our respective cities and conferred via telephone. One night, one of us (probably me) went watery with emotion. We have been blessed by a father who sacrificed so much to raise us, and now he might die in a sterile room encased in brick.

Everyone deals with this, my close friends said. Your parents die. You can’t prepare.

But you do try, however numbly, to wrestle the unacceptable into a reality.

There are calls, emails, taps on the shoulder we all dread. For me, my mother’s email announcing my father’s appointment for surgery this spring slid into that queasy domain. Boston’s Mass General is a big hospital in the US and one of the most famous in the world. Appointments are made arbitrarily, helicopters airlift accident victims in urgent need. The near-dead are sometimes quelled and revived amid skewed schedules.

My mother’s email was last-minute, but reasonable compared to what the hospital manages on a daily basis. Still, I had only five days to book a flight from Tokyo to Boston, and no idea when I could, should or would be able book a return. The email arrived late on a Saturday night in Tokyo; I began phoning airlines on Sunday morning.

By Friday, I was back in the tunnel of trans-Pacific travel, typing empty words onto my tablet screens, rising to piss, stretch and stare at the wall, and pondering my arrival in Boston—not for an appearance or book signing, but to see if my father might survive.

The English word, ‘travel,’ conjures romantic notions—journey, pilgrimage, leisure and escape. But traveling from Tokyo to Boston and back when you don’t want to, didn’t plan to do so, and are not being paid for the duress, is as flat and rough as sandpaper. It looks plain, and it hurts.

I have flown from Tokyo to the US so many times that the experience has become a shade less than mundane. Boarding a bus offers more possibilities. My unconscious rituals of behavior—vitamin-rich drinks I choose at specific intervals en route, sleep postures and stretch schedules—would bore even a seasoned tourist.

But this time, I strayed. I couldn’t focus on work, movies, TV shows, flight attendants or even a friend who serendipitously greeted me near the toilets. I heard but couldn’t listen to what he said. I wasn’t thinking about my father, really, or the arrival at Logan in Boston, or the following weeks of anxiety and vulnerability. I wasn’t thinking at all, and so when I saw Alaska expand in deep whites below the wing porthole, I felt a sense of relief.

Snow. Ah. I was raised in snowy norths.

A connecting flight was inevitable in my last-minute itineraries. My flight out of Detroit was delayed by two hours. A pilot from the same airline sat next to me and regaled me with critiques of his own employer. He asked me why I was making the trip.

“My father is dying,” I said.

“Aren’t we all.”

My weeks in Boston this spring were as troubling as I knew they would be, but I still can’t find a way I could have prepared for them. Dad didn’t die; he’s recovering as I write now, and I caught my return flight to Tokyo, only to fly back to NYC for work a couple of weeks later.

Blessed. I was in Kyoto last week; I will be in New York next week, and in China thereafter for work. My father is alive, limping along, and his sagging face cupped in my hands is a now a luxury.

Still, the worries remain, the odd anxieties over being so close and so far at once, and the utter finality of enormous death. I did what I had to do, and no one has chastised me.

Flying around the world on a dime once sounded cool, didn’t it?

Our sense of travel evolves as we do, and its evolution is shaped by our needs, values and fears. I think I’m most afraid of learning what many in Japan learned last year—that an entire population can be destroyed in one instant, and that one of them might be among your beloved.

The digital recording of my parents querying their surgeon is a kind of poetry to me now, a simple account of lines about what will happen, what must happen, and what might occur.

The dying tell us to value life. So simple. On a plane, I am always in between. I am here, in Tokyo, in New York, in Los Angeles, London or Boston.

But what matters now is this: Who is here with me?

Published on July 06, 2012 06:46

July 3, 2012

My past is past

Published on July 03, 2012 10:00