Roland Kelts's Blog, page 47

June 4, 2013

Japanese ghosts haunt Prime Minister Abe

Published on June 04, 2013 04:07

May 31, 2013

On Japan's identity crisis and nationalism for Time magazine

The Identity Crisis That Lurks Behind Japan’s Right-Wing Rhetoric

from Time magazine

By Roland Kelts May 31, 2013

Chung Sung-Jun / Getty Images

South

Korean hold placards carrying the images of Japanese Prime Minister

Shinzo Abe and Osaka Mayor Toru Hashimoto during a rally on May 23, 2013

in Seoul, South Korea. Recent remarks by the mayor of Osaka on the

historic perception of 'comfort women', conscripted by Japanese military

brothels during World War II, have recieved intense criticism from

neigbouring countries and the U.S.

When anti-Japan protests, the fiercest in years, erupted in China

over territorial disputes last September, I was attending a conference

in Tianjin, roughly 80 miles south of Beijing. Footage from the capital

was chilling: smashed Japanese department stores and automobiles, flags

on fire, protesters hurling eggs and debris at the Japanese embassy with

chants of “F*** Japan.” Someone tried to crash into a Japanese diplomat’s car on a Beijing highway.

By comparison, the Tokyo I returned to a week later felt downright

placid. Most Japanese peered down their noses at the violence in

Beijing, finding the scenes embarrassing and barbaric. One Japanese

government official I spoke to privately blamed then Prime Minister

Yoshihiko Noda and his administration for bungling the whole affair

through diplomatic incompetence. “They should have kept quiet about [the

purchase of the disputed islands],” he said. “None of this would have

happened.”

A few months later, Noda was gone, replaced by Shinzo Abe and his

conservative Liberal Democratic Party (infamously neither liberal nor

democratic), high on a nationalist-leaning platform. Suddenly, the yen

tanked, aiding Japanese exporters, and right-wing rhetoric and behavior

spiked. High-profile politicians, including Deputy Prime Minister and

former PM Taro Aso, visited Tokyo’s controversial Yasukuni Shrine, a

memorial to Japan’s war dead and criminals that whitewashes the nation’s

imperialist massacres in Asia. Abe floated revisions to Japan’s 1995

war apology and its pacifist constitution, Article 9 of which forbids

Japan from having a standing army. He dressed up in army fatigues and posed in a fighter jet emblazoned with the numerals 731, the number of the most notorious Japanese chemical and biological warfare unit in World War II.

Toru Hashimoto, mayor of Japan’s so-called second city, Osaka, also dropped a couple of stink bombs. He said the sexual enslavement of Asian women

to satisfy the Japanese military in World War II was par for the

course, and doubted that it was state-sanctioned. Then he advised male

U.S. military personnel in Okinawa and elsewhere to make use of the

Japanese sex industry to reduce crimes of sexual assault.

Hashimoto’s gaffes would be uninteresting except for this: he apologized to Americans for the second, but had no words of remorse for his Asian brethren. Why should that be so?

Japan’s national identity (the story it tells itself in order to be

itself) has been disrupted twice. In 1853, American Commodore Matthew

Perry blasted open the isolated Tokugawa regime for trade. In 1945,

American General Douglas MacArthur tore open an isolated military

government for trade, military expediencies and intelligence. In both

cases, the Americans, icons of the West, focused Japan on modernization

— and away from Asia. Japan complied and became the second richest

economy in the world, if not the first, in the late 20th century.

Japan thrived following a simple path: Learn from the West. Forget Asia.

Its apparent swerve toward nationalism in 2013 may be the result of a

desperate identity crisis. Japan has not been “Japanese” since Perry’s

intrusion 160 years ago, and MacArthur’s occupation 70 years ago. Yet it

was never colonized like its Asian neighbors in Korea, China and

Southeast Asia. In a sense, Japan is the proverbial black sheep of Asia,

neither Western nor Eastern, claimed or lost.

Recent geopolitical repositionings slip Japan between rocks and

harder rocks. Europe is an economic sinkhole. The U.S. is distracted by

two wars and domestic failure. The only power is in Asia, a region Japan

has long abandoned, and in the failed friend of Japan that is the U.S.

I asked Pankaj Mishra, author of From the Ruins of Empire, a study of Asia’s intellectual traditions, if and how Japan could resuscitate its value in Asia.

“It seems that Japan can only be taken seriously by its Asian

neighbors, especially rising China, and become a normal nation-state if

it emerges from under the American security umbrella,” he says. “[It

needs] to revise MacArthur’s constitution and become a nuclear-armed

military power.”

But Japan cannot renounce its pacifistic constitution without raising

anxieties in Asia — and elsewhere. It’s hard to imagine another

well-meaning nation with such bad options. If Japan renounces its

U.S.-made constitution, it risks belligerent response. If it doesn’t, it

has no sovereign identity.

Mishra adds: “I can’t think of another nation with such terrible historical choices.”

One night in Manhattan, a friend of mine said: “Can you imagine

taking the Long Island Rail Road for an hour, and finding a Japanese air

base, replete with shiny fighter jets with Japanese flags performing

formations? That’s what Japanese see one hour out of Tokyo.”

Hiroki Azuma, one of Japan’s leading young academics, notes that

images of traditional Japan in its popular culture invariably refer to

the Edo era — Japan before the arrival of the Americans. Yet they still

contain anachronistic icons — zippo lighters, cell phones, fast-food

emporiums.

Japan is a country whose identity has been bowdlerized, hollowed out

by a dream of Western dominance that no longer exists. It may make sense

to see its recent surge in nationalism as a dumbed-down version of

Japanese adolescence. This is a country spun around by its own

single-minded pursuit of progress, and it has no idea who it’s supposed

to be today.

Read more: http://world.time.com/2013/05/31/the-identity-crisis-that-lurks-behind-japans-right-wing-rhetoric/#ixzz2Uva1vujm

from Time magazine

By Roland Kelts May 31, 2013

Chung Sung-Jun / Getty Images

South

Korean hold placards carrying the images of Japanese Prime Minister

Shinzo Abe and Osaka Mayor Toru Hashimoto during a rally on May 23, 2013

in Seoul, South Korea. Recent remarks by the mayor of Osaka on the

historic perception of 'comfort women', conscripted by Japanese military

brothels during World War II, have recieved intense criticism from

neigbouring countries and the U.S.

When anti-Japan protests, the fiercest in years, erupted in China

over territorial disputes last September, I was attending a conference

in Tianjin, roughly 80 miles south of Beijing. Footage from the capital

was chilling: smashed Japanese department stores and automobiles, flags

on fire, protesters hurling eggs and debris at the Japanese embassy with

chants of “F*** Japan.” Someone tried to crash into a Japanese diplomat’s car on a Beijing highway.

By comparison, the Tokyo I returned to a week later felt downright

placid. Most Japanese peered down their noses at the violence in

Beijing, finding the scenes embarrassing and barbaric. One Japanese

government official I spoke to privately blamed then Prime Minister

Yoshihiko Noda and his administration for bungling the whole affair

through diplomatic incompetence. “They should have kept quiet about [the

purchase of the disputed islands],” he said. “None of this would have

happened.”

A few months later, Noda was gone, replaced by Shinzo Abe and his

conservative Liberal Democratic Party (infamously neither liberal nor

democratic), high on a nationalist-leaning platform. Suddenly, the yen

tanked, aiding Japanese exporters, and right-wing rhetoric and behavior

spiked. High-profile politicians, including Deputy Prime Minister and

former PM Taro Aso, visited Tokyo’s controversial Yasukuni Shrine, a

memorial to Japan’s war dead and criminals that whitewashes the nation’s

imperialist massacres in Asia. Abe floated revisions to Japan’s 1995

war apology and its pacifist constitution, Article 9 of which forbids

Japan from having a standing army. He dressed up in army fatigues and posed in a fighter jet emblazoned with the numerals 731, the number of the most notorious Japanese chemical and biological warfare unit in World War II.

Toru Hashimoto, mayor of Japan’s so-called second city, Osaka, also dropped a couple of stink bombs. He said the sexual enslavement of Asian women

to satisfy the Japanese military in World War II was par for the

course, and doubted that it was state-sanctioned. Then he advised male

U.S. military personnel in Okinawa and elsewhere to make use of the

Japanese sex industry to reduce crimes of sexual assault.

Hashimoto’s gaffes would be uninteresting except for this: he apologized to Americans for the second, but had no words of remorse for his Asian brethren. Why should that be so?

Japan’s national identity (the story it tells itself in order to be

itself) has been disrupted twice. In 1853, American Commodore Matthew

Perry blasted open the isolated Tokugawa regime for trade. In 1945,

American General Douglas MacArthur tore open an isolated military

government for trade, military expediencies and intelligence. In both

cases, the Americans, icons of the West, focused Japan on modernization

— and away from Asia. Japan complied and became the second richest

economy in the world, if not the first, in the late 20th century.

Japan thrived following a simple path: Learn from the West. Forget Asia.

Its apparent swerve toward nationalism in 2013 may be the result of a

desperate identity crisis. Japan has not been “Japanese” since Perry’s

intrusion 160 years ago, and MacArthur’s occupation 70 years ago. Yet it

was never colonized like its Asian neighbors in Korea, China and

Southeast Asia. In a sense, Japan is the proverbial black sheep of Asia,

neither Western nor Eastern, claimed or lost.

Recent geopolitical repositionings slip Japan between rocks and

harder rocks. Europe is an economic sinkhole. The U.S. is distracted by

two wars and domestic failure. The only power is in Asia, a region Japan

has long abandoned, and in the failed friend of Japan that is the U.S.

I asked Pankaj Mishra, author of From the Ruins of Empire, a study of Asia’s intellectual traditions, if and how Japan could resuscitate its value in Asia.

“It seems that Japan can only be taken seriously by its Asian

neighbors, especially rising China, and become a normal nation-state if

it emerges from under the American security umbrella,” he says. “[It

needs] to revise MacArthur’s constitution and become a nuclear-armed

military power.”

But Japan cannot renounce its pacifistic constitution without raising

anxieties in Asia — and elsewhere. It’s hard to imagine another

well-meaning nation with such bad options. If Japan renounces its

U.S.-made constitution, it risks belligerent response. If it doesn’t, it

has no sovereign identity.

Mishra adds: “I can’t think of another nation with such terrible historical choices.”

One night in Manhattan, a friend of mine said: “Can you imagine

taking the Long Island Rail Road for an hour, and finding a Japanese air

base, replete with shiny fighter jets with Japanese flags performing

formations? That’s what Japanese see one hour out of Tokyo.”

Hiroki Azuma, one of Japan’s leading young academics, notes that

images of traditional Japan in its popular culture invariably refer to

the Edo era — Japan before the arrival of the Americans. Yet they still

contain anachronistic icons — zippo lighters, cell phones, fast-food

emporiums.

Japan is a country whose identity has been bowdlerized, hollowed out

by a dream of Western dominance that no longer exists. It may make sense

to see its recent surge in nationalism as a dumbed-down version of

Japanese adolescence. This is a country spun around by its own

single-minded pursuit of progress, and it has no idea who it’s supposed

to be today.

Read more: http://world.time.com/2013/05/31/the-identity-crisis-that-lurks-behind-japans-right-wing-rhetoric/#ixzz2Uva1vujm

Published on May 31, 2013 19:34

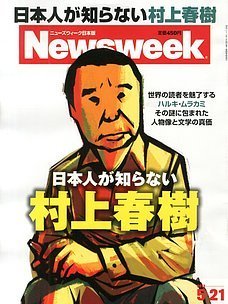

May 21, 2013

My Murakami feature story in Newsweek Japan

I wrote the lead story for

Newsweek Japan

's new feature on Haruki Murakami, and it's available in digital format here.

Published on May 21, 2013 14:19

May 20, 2013

On Haruki Murakami, Monkey Business & the art of literary translation for The New Yorker

Lost in Translation?

Posted by

Last month, Haruki Murakami published a new novel in Japan. Before anyone could read it, the novel broke the country’s Internet pre-order sales record, its publisher announced an advance print run of half a million copies, and Tokyo bookstores opened at midnight to welcome lines of customers, some of whom read the book slumped in corners of nearby cafés straight after purchase. But this time, the mania was déjà vu in Japan—a near-replica of the reception that greeted Murakami’s last novel, “1Q84,” three years ago. The response was news to nearly no one. Except, maybe, Haruki Murakami.

“The fact that I have been able to become a professional working novelist is, even now, a great surprise to me,” Murakami wrote in an e-mail three days before the release of “Colorless Tsukuru Tazaki and His Years of Pilgrimage.” He added: “In fact, each and every thing that has happened over the past 34 years has been a sequence of utter surprise.” The real surprise, perhaps, is that Murakami’s novels now incite a similar degree of anticipation and hunger outside of Japan, even though they are written in a language spoken and read by a relatively small population on a distant and parochial archipelago in the North Pacific.

Murakami is a writer not only found in translation (in forty-plus languages, at the moment) but one who found himself in translation. He wrote the opening pages of his first novel, “Hear the Wind Sing,” in English, then translated those pages into Japanese, he said, “just to hear how they sounded.” And he has translated several other American writers into Japanese, most notably Raymond Carver, John Irving, J. D. Salinger, and F. Scott Fitzgerald, whose “The Great Gatsby” Murakami credits as the inspiration behind his entire career.

Motoyuki Shibata, a translator, scholar, and professor at Tokyo University, told me that American fiction becomes an entirely different creature in an alien habitat when presented to Japanese readers. “In the Meiji era, most Japanese read Americans for moral instruction,” he said. “They wanted to learn about concepts of autonomy and individualism and Christianity. They were not seeking entertainment.” American literature arrived in nineteenth-century Japan on the heels of its military—forcing open an isolated nation with modern ideas and technology. Early translators and readers, Shibata said, approached life and literature with a rigid racial hierarchy, with the Caucasians at the top, the Japanese in the middle, and the remaining ethnicities and colors at the bottom. Anything written by whites from the West was deemed inherently superior, just because Japanese looked up to them.

After the Second World War, novels like “The Old Man and the Sea,” “The Call of the Wild,” and “Moby-Dick” entranced Japanese readers yearning for a future of heroism, naturalism, and reason in the wake of the chaotic militarism and destruction they’d endured. Instruction was still a part of the appeal, but heroism and identity moved to the forefront. The transformation to a more purely literary engagement with American fiction, with readers appreciating and actually enjoying American prose over what it could teach them, occurred in 1975. That’s when Kurt Vonnegut and Richard Brautigan were translated into Japanese and introduced a sense of humor, absurdity, and social criticism voiced in vernacular prose.

Kazuko Fujimoto’s translation of Brautigan’s best-known work, “Trout Fishing in America,” was a revelation to Japanese readers like Shibata and Murakami. “That was the first time,” said Shibata, “instead of looking up to the author and the characters, I looked level at them. I felt characters finally began to talk like real human beings, though of course with their own oddities and eccentricities.” He continued: “Ms. Fujimoto’s Japanese was often quirky and zany, but that quirkiness and zaniness was in accord with the feel of the originals. She broke the rules of everyday Japanese, but the way she did it was more fun, and she made the Japanese language richer, instead of torturing the poor thing as some older translators did.”

Brautigan and Vonnegut are far more famous and well-read in Japan today than American stalwarts like John Updike, Philip Roth, and Toni Morrison. Readers are more likely to buy books based on entertaining storytelling and plots, the quality and sound of the Japanese prose, and the reputation of the translator. “I sometimes don’t think I understand American readers,” Murakami told me in Boston several years ago when trying to parse why a novel that he loved, Tim O’Brien’s “The Nuclear Age,” was widely panned in the States. “I sometimes think they’re missing something.”

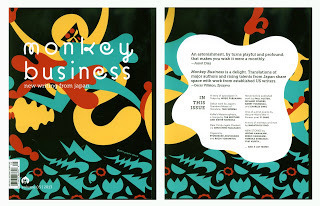

To fill that gap of understanding, Shibata and his friend Ted Goossen, a translator of Japanese literature and professor at Toronto’s York University, have for three years been publishing an annual English-language literary magazine called Monkey Business International: New Writing from Japan. (I am a contributing editor.) The project was born out of frustration: Why was Haruki Murakami the only contemporary Japanese writer anybody outside of Japan knew? Goossen urged Shibata to cull material from his own Japanese-language literary quarterly, the original Monkey Business. Murakami is a contributor, of course, but his writing takes on new colors alongside stories and poems by his Japanese contemporaries (younger and older), classic Japanese literature, and even Japanese manga.

Still, I can’t help but wonder if the translation of literature, where the strengths and even personality of the original are embedded in the language, is futile, however heroic. “When you read Haruki Murakami, you’re reading me, at least ninety-five per cent of the time,” Jay Rubin, one of Murakami’s longtime translators, told me in Tokyo last month, explaining what he says to American readers, most of whom prefer to believe otherwise. “Murakami wrote the names and locations, but the English words are mine.” Murakami once told me that he never reads his books in translation because he doesn’t need to. While he can speak and read English with great sensitivity, reading his own work in another language could be disappointing—or worse. “My books exist in their original Japanese. That’s what’s most important, because that’s how I wrote them.”

But he clearly pays attention during the process of translation. Rubin said that the first time he translated a Murakami novel, “The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle,” he phoned the author several times one day to nail word choices and correct inconsistencies. “In one scene, a character had black-framed glasses. In another, the frames were brown. I asked him: Which one is it?” I found Rubin’s anecdote revealing. The Japanese language acquires much of its beauty and strength from indirectness—or what English-speakers call vagueness, obscurity, or implied meaning. Subjects are often left unmentioned in Japanese sentences, and onomatopoeia, with vernacular sounds suggesting meaning, is a virtue often difficult if not impossible to replicate in English.

Alternatively, English is often lauded for its specificity. Henry James advised novelists to find the figure in the carpet, implying that details and accuracy were tantamount to literary expression. Is it possible that Japanese and English are two languages so far apart that translators can only reinvent their voices by creating entirely new works? Last week, Shibata, Goossen, and a lineup of Japanese and American writers were in New York to host a series of events to introduce the third and latest English version of Monkey Business, as part of the PEN World Voices Festival. At their Asia Society dialogue, Goossen quoted Charles Simic’s take on the magical absurdity of translating poetry: “It’s that pigheaded effort to convey in words of another language not only the literal meaning of a poem but an alien way of seeing things … To translate is not only to experience what makes each language distinct, but to draw close to the mystery of the relationship between word and thing, letter and spirit, self and world.”

Murakami would likely agree. In a recently published essay on his decision to render “The Great Gatsby” in Japanese, the sixty-four-year-old author reveals that it became something of a lifelong mission. He told others about his ambition in his thirties, and believed then that he’d be ready to undertake the challenge when he reached sixty. But he couldn’t wait. Like an overeager child unwrapping his presents, he translated “Gatsby” three years ahead of schedule. Translation, he writes, is similar to language and our relationship with our world. It, too, needs to be refreshed:

"Translation is a matter of linguistic technique… which naturally ages as the particulars of a language change. While there are undying works, on principle there can be no undying translations. It is therefore imperative that new versions appear periodically in the same way that computer programs are updated. At the very least this provides a broader spectrum of choices, which can only benefit readers."

Roland Kelts is the author of “Japanamerica: How Japanese Pop Culture Has Invaded the United States.” He divides his time between New York and Tokyo.

Photograph: Kevin Trageser/Redux

Read more: http://www.newyorker.com/online/blogs...

Published on May 20, 2013 12:17

May 8, 2013

Japan Times column on pop and tourism in Japan

Pop tourism gains traction

BY ROLAND KELTS

Pre-flight shopping at Narita airport a couple of weeks ago, I passed a mannequin sporting a light-blue necktie and a turquoise wig with pig tails dangling down to its mini skirt. The vision spoke volumes: It was Hatsune Miku, of course, Japan’s holographic, animated virtual pop star, beloved fashion icon and model for pop culture fans and cosplayers worldwide. But why was she suddenly manning the plaza concourse of Japan’s busiest tourist portal, standing tall beside Uniqlo and Shu Uemura?

It turns out Miku is part of an expansive display in the new airport outlet of Cospa Akihabara, a shop devoted to Japanese pop culture products for global otaku (geeks)and cosplayers. The Narita venue opened in February and had a lively crowd of consumers at its counters when I stalled next to Miku last month, gingerly fingering my wallet.

Tourism has long been a fiscal conundrum for Japan, the country’s potential cash cow stifled by its resistance to foreigners and xenophobic anxieties, and hampered by a reputation for overblown prices — a crude hangover from the bubble years of the 1980s. The 3/11 disasters and ongoing plight of Fukushima only exacerbate the problem.

Worse, the nation’s soft-power selling point often seems stuck in centuries past. Those of us who live, work and travel here know well the virtues contemporary Japan boasts. But for years, Japan has promoted itself overseas as a bastion of bygone traditions — demure kimono-clad girls and stoic samurai boys cowering beneath a volcano called Fuji, with raw seafood and grass mats for comfort.

In the face of its 21st-century reality, this hoary image of Japan wears thin fast. The “Pokemon” and “Naruto” generations might dig the temples of Nara once they get there, but they need a reason to get there first.

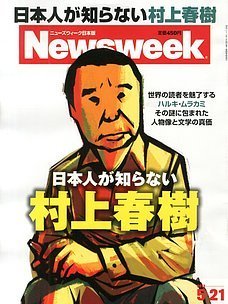

Seiji Horibuchi, founder of Viz Media, a veteran U.S. distributor of Japanese entertainment, has long understood the appeal of what the government still labels Cool Japan. In 2009, Horibuchi opened New People, a three-story bricks-and-mortar retail outlet in San Francisco’s Japan Town, tailored to the tastes of young Americans and tourists with an interest in contemporary Japanese culture. The complex features fashion boutiques, an art gallery and an HD cinema with a THX sound-system for the screening of first-run Japanese feature films and anime titles.

New People’s latest venture, launched in January, is an online magazine called New People Travel, an attempt to connect anime fans with their heroes, veteran artists in the industry who have earned rock-star status, while introducing Japan as an attractive and accessible 21st-century tourist destination.

I asked the company about the magazine last week via email from my hotel in South Africa, where the market for Japanese pop culture has recently spiked.

“Our ultimate goal is to interest more people in traveling to and in Japan,” said New People Executive Director Manami Iiboshi. “This has been a similar goal for the New People building since it opened. The site is available in both Japanese and English because we wanted to share this vision with people both inside and outside of Japan. Sometimes even Japanese people need to see themselves from an outside standpoint in order to appreciate their culture and its beauty.”

The site’s current incarnation is a gift for anime fans and other aficionados of Japanese art. “Ghost in the Shell” maestro Mamoru Oshii weighs in on the soulless nature of modern Tokyo and its susceptibility to military attack; “Final Fantasy” artist Yoshitaka Amano discusses longing for his childhood in Shizuoka Prefecture and drawing on the beauty of the Kumano region in Wakayama and Mie prefectures; and Mamoru Hosoda explains why he set the family home in “Summer Wars” in his wife’s rural hometown of Ueda in Nagano Prefecture.

New People Travel grew out of a collaboration with Japan’s Aisin Aw Co., Ltd. (a developer of car navigation systems), and its latest issue introduces a broad range of travel destinations in Japan such as the Noto Peninsula, Kyoto and the Hakata district in Fukuoka, alongside interviews with film director Katushito Ishii and Pixar artist Dice Tsutsumi.

“We picked a very diverse group of visionaries to showcase on the site,” added Iiboshi, “to provide readers with a new and colorful vision of Japan shown through the eyes of Japanese artists that have broad recognition worldwide.”

This summer New People will host their fifth J-Pop Summit Festival, its annual San Francisco-based celebration of Japanese culture, entertainment and fashion featuring live performances, exhibitions, and for the first time, a gourmet food truck festival. Last year’s event drew 65,000 attendees. New People will expand the festival venues in 2013 to include Union Square in the heart of the city, and they anticipate a record-breaking 70,000 visitors.

On the U.S. East Coast, summer will also see the 20th anniversary of Otakon, the region’s most popular anime convention, whose organizers announced earlier this year that they would host a second Japanese pop culture convention in Las Vegas in January 2014. And next month, a series of launch events will be held in New York City for the latest issue of Monkey Business International, the English-language edition of the contemporary Japanese literary magazine, to which (full disclosure) I am a contributing editor. The weeklong sessions will bring together Japanese literati Genichiro Takahashi, Mina Ishikawa and Motoyuki Shibata with Americans Paul Auster, Charles Simic and Kevin Brockmeier, among others, and will be hosted by the PEN World Voices Festival.

On April 4, the United Nations World Tourism Organization announced that Chinese travelers have overtaken Germans and Americans as the world’s biggest spenders. Whether political tensions will keep them from booking flights to Japan remains to be seen. But with Japan’s domestic stimulus taps now turned fully on, thanks to so-called Abenomics and Bank of Japan governor Haruhiko Kuroda, it’s high time the nation marshaled its cultural capital abroad to line the coffers at home.

Roland Kelts is the author of “Japanamerica: How Japanese Pop Culture has Invaded the U.S.” He is a Visiting Scholar at the University of Tokyo.

Published on May 08, 2013 21:53

May 3, 2013

Thanks -- and Monkey Finale in NYC

Thanks for the tremendous support of

Monkey Business

this week in NYC.

Our final event takes place tomorrow, May 4, at The Asia Society of New York, once again hosted by The PEN World Voices Festival. Paul Auster & Charles Simic will join Genichiro Takahashi & Mina Ishikawa for a

Copies of all three issues of Monkey Business will be on sale at a special on-site only price. Tix & info here.

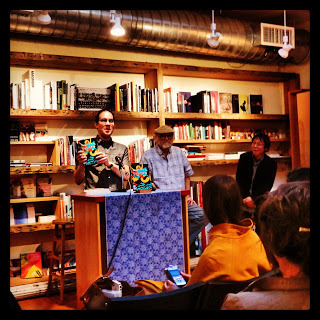

Joe's Pub, 5/1

BookCourt, 5/2

Our final event takes place tomorrow, May 4, at The Asia Society of New York, once again hosted by The PEN World Voices Festival. Paul Auster & Charles Simic will join Genichiro Takahashi & Mina Ishikawa for a

Copies of all three issues of Monkey Business will be on sale at a special on-site only price. Tix & info here.

Joe's Pub, 5/1

BookCourt, 5/2

Published on May 03, 2013 12:46

May 1, 2013

On traveling to Cape Town, South Africa ...

... before I even went. Latest travel column about anticipating and imagining a voyage to virgin territory. For

Paper Sky

magazine.

[click to enlarge]

(photos courtesy of Sevgin Adaliev)

[click to enlarge]

(photos courtesy of Sevgin Adaliev)

Published on May 01, 2013 10:47

April 30, 2013

Monkey Business launch party, tomorrow, May 1, in NYC

Check out the bands for MONKEY's launch tomorrow night

We’re thrilled to have two brilliant Japanese bands performing at tomorrow night’s opening party for Monkey Business, Issue 3 . It will be an evening not to be missed.

*Check out NEO BLUES MAKI here .

*And then hang with Japanese female indie rockers THE SUZAN here .

**Catch them both live tomorrow night, May 1st … right here.

Published on April 30, 2013 16:01

April 25, 2013

Chinese translation rights to Japanamerica ....

...now sold. And it's all legal!

My thanks to the book's US/UK publisher, Macmillan, and to Chinese publisher Beijing Yanziyue Culture & Art Studio for their faith and largesse.

Looking forward to the new cover, and to the end of wasteful and hoary disputes among three great countries.

Published on April 25, 2013 16:38

April 22, 2013

Monkey Business 3 Launch in NYC next week

Here's the initial rundown, as of right now.

[EVENT 1] Wednesday, May 1st 2013, 7-8:30pm

Joe’s

Pub, 425 Lafayette Street, New York

Monkey

Business : A Cabaret with A

Public Space

East

meets West Meets Uptown meets Downtown

Readings by Gen’ichiro Takahashi, Mina

Ishikawa, Kevin Brockmeier, Ted Goossen and Motoyuki Shibata

Music by Neo Blues Maki and The Suzan

Hosted by Roland Kelts

[PEN info]

PEN World Voices joins with Asia Society, A Public Space,

and Monkey

Business International—the acclaimed

English-language anthology of newly translated Japanese

writing—for a cabaret-style night of readings,

conversation,

and music. Hosted by Japanamerica author Roland Kelts.

Tickets: $15/$12 PEN Members and students with valid ID

$12 food minimum or two drink minimum per person

212-967-7555 or www.publictheater.org, or visit The

Public

Theater Box Office at 425 Lafayette Street. Box Office Hours:

Sun-Mon 1-6 p.m., Tue-Sat 1-7:30 p.m.

EVERYONE WITH A TICKET GETS A FREE COPY OF

ISSUE 3 OF MONKEY BUSINESS

Presented in association with The Public Theater, a

center

for culture, arts, and ideas, and co-sponsored by Asia

Society,

Monkey

Business, and A Public Space.

----------------------------------------------------------------

[EVENT 2] Thursday,

May 2nd 2013, 4 p.m. to 5:30 p.m Baruch

College, 55 Lexington Ave. at 24th St., New York

Resonances:

Contemporary Writers on the Classics

Participants: Nadeem

Aslam, Eduardo Halfon, James Kelman, and Gen’ichiro Takahasi

Moderated by: Eva S. Chou

[PEN Info]

Before the flame, a spark.

Each year, a group of Festival authors are invited by Baruch

College’s Great Works program to comment on a classic

work of literature or author that influenced their own work.

Panelists speak about the great works that affected them,

read from their own work or their chosen classic text to

illustrate the impact, then engage in discussion with the

audience.

Free and open to the public.

Co-sponsored by The Great Works Program, Weissman

School of Arts and Sciences—Baruch College, Asia Society,

Monkey Business, and A Public Space.

----------------------------------------------------------------

[EVENT 3] Dialogue between Kevin Brockmeier

and Mina Ishikawa

Roland

Kelts introduces Monkey Business , and Goossen and Shibata say hello to the audience

Thursday, May 2,

7pm

BookCourt, 163 Court Street, Brooklyn

----------------------------------------------------------------

Asia Society, 725 Park Avenue at 70th

Street, New York

Monkey Business-- Japan/America: Writers’ Dialogue

Dialogues

between Paul Auster and Gen’ichiro Takahashi, and between Charles Simic and

Mina Ishikawa

[PEN info]

Paul Auster and Charles Simic join Gen’ichiro

Takahashi,

one of Japan’s

leading novelists and critics, and Mina Ishikawa,

a fresh new voice in tanka poetry, for an intriguing

cross-cultural

encounter. The conversation will be facilitated by

eminent translators

Motoyuki Shibata and Ted Goossen, the editors of the

acclaimed

English-language anthology of newly translated Japanese

writing,

Monkey

Business International.

Tickets: $15/$10 Asia

Society and PEN Members; $12

students and seniors

Co-sponsored by Asia

Society, A Public Space, and Monkey

Business.

Shibata will be

giving a talk at Baruch College at 1pm, on May 2

Shibata is also giving a keynote speech for a symposium “The Politics of Polyglossia,” at Baruch College, 1:30pm, May 6:

Published on April 22, 2013 04:04