Roland Kelts's Blog, page 46

August 21, 2013

@ Japan Expo USA this Sunday, August 25, 2 p.m.

Japan Society will have a booth at this year’s Japan Expo in Santa Clara! CALL FOR VOLUNTEERS: If interested in volunteering at the Japan Society booth on Saturday, August 24th or Sunday, August 25th, please e-mail kodonnell@usajapan.org.

Roland Kelts is speaking on behalf of the Japan Society of Northern California thanks to a generous grant from The Japan Foundation Center for Global Partnership. His lecture will be held at 2:00PM on Sunday, August 25th at the Hall Stage.

ANIME vs. HOLLYWOOD in JAPANAMERICA, with Roland Kelts

Roland Kelts, author of “

In his presentation, Kelts will explore why Hollywood is fascinated with Japanese pop culture and is trying to remake popular Japanese anime titles to appeal to a whole new generation of viewers. Death Note, Naruto, Cowboy Bebop—and the attempts to make feature films out of stalwarts like Dragon Ball Z and Grave of the Fireflies will be addressed with passion. Anime vs. Hollywood: Who wins? A close look at the challenges and potential missteps along the way.

Additionally, San Francisco Japantown’s own NEW PEOPLE has coordinated a great exhibit on traditional Japanese culture called “Wabi Sabi” for this year’s Japan Expo. Check it out!

Published on August 21, 2013 17:16

August 15, 2013

On 20 years of Otakon for my latest Japan Times column

Otakon celebrates 20 years of anime fandom in the U.S .

BY ROLAND KELTS

The American anime convention, Otakon (“Otaku Convention”), begins with a costume parade before it officially opens. Last week I had a bird’s-eye view of the spectacle from my 14th-floor hotel room in Baltimore, Maryland. An endless army of imaginary characters trudged across the elevated concourse and down adjacent sidewalks to the Baltimore Convention Center to register and obtain entry badges. Most were instantly recognizable from anime series old and new, brandishing swords or other weaponry fashioned out of homemade materials, or wearing massive multicolored wigs, capes or sewn-on tails — or very little at all.

For three days the colorful mob overtook Baltimore’s downtown and Inner Harbor neighborhoods, and until they returned to their hometowns in 42 different states, you couldn’t walk 20 meters without bumping into, overhearing and/or following them.

Roughly 35,000 fans of Japanese pop culture attended the event, according to Otakon’s director of press and publicity, Victor Albisharat. They skewed 53 percent female; 75 percent aged 19-34, and organizers say they keep getting younger.

“People go to Otakon for different things,” says Lance Heiskell, director of corporate strategy for Funimation Entertainment, one of the largest distributors of anime in the United States. “This year they had (Japanese anime soundtrack composer) Yoko Kanno. Some people came for the J-Pop of T.M. Revolution. Others just want to dress up and get together. And some people just come to dance at the nightly raves because, you know, they’re safe.”

This year also saw the celebration of Otakon’s 20th anniversary, a milestone for any kind of convention, let alone one devoted to a popular culture in a foreign language from a country thousands of miles away. Otakon retains a special place among fans and industry guests from both sides of the Pacific, artists, performers, panelists — and even its own mostly volunteer staff.

Otakon’s nonprofit status and its slogan — “by fans, for fans” — is a rarity in an entertainment convention business that often relies upon sponsorship deals and top-down decision-making. Nearly 850 volunteers staffed Otakon 2013.

“We’re a grass-roots-driven organization,” says Otakon Chair Terry Chu. “We have a different approach to things, a different template. The model is a family, not just figuratively, but literally. We now have volunteers who are the children of volunteers who met at the convention and got married.”

You hear the word “family” a lot when people talk about Otakon’s 20-year legacy. “We don’t make distinctions between the staff, the fans and the guests,” adds Jim Vowles, Otakon’s director of guest relations. “We try to treat all three with the same level of respect. I think that’s the difference (between us and others).”

Nonetheless, there have been some hiccups. A train accident in 2001 released chemicals that triggered pressures beneath the city’s streets, blowing open several manhole covers around the convention center. In 2010, the center’s fire alarms sounded by mistake, causing the evacuation of over 20,000 attendees during peak hours. Both events were handled with grace, and the convention has had no incidents of serious crime or assault.

“(During) the fire-alarm evacuation,” says Vowles, “our volunteer staff were praised by the professionals who were supposed to take care of it. The fans and guests evacuated calmly and things got back on track. We were very proud of them.”

Around 260 anime conventions take place in North America annually. “I don’t know what it is (about Otakon),” says Heiskell. “But everyone is cool and collected on staff here. It’s not cliqueish, and that makes everything move with well-oiled efficiency. I’ve been attending this con for 10 years, and I always say to people, ‘If I ever leave the anime industry, I want to join (the Otakon) staff.’

“The (type of) fans helps, too,” he adds. “Maybe anime fans are the softer, gentler geek. You have to have the cognitive reasoning to understand and appreciate most of these shows. We tend to try to get along.”

Convention highlights last weekend included a screening of anime maestro Mamoru Hosoda’s “Wolf Children,” dubbed in English by voice actors who were on hand to discuss their work, and a solo performance by revered pianist/composer Yoko Kanno.

Hosoda, a Ghibli alumnus, is a patient, literate auteur. His films do not feature giant robots, Naruto-like ninjas or Sailor Moon-esque pixies. Kanno is an accomplished jazz and classical pianist and composer. How would these American kids, exhibitionistic cosplayers and proud nerds react to art slightly more highbrow than “One Piece” and “Escaflowne”?

They didn’t just react; they engaged. At both events, Otakon fans were silent, quietly sobbing amid a scene, or singing in unison to a Kanno soundtrack. The Hosoda screening was sold out; no one left early, and amid a slowly unraveling tragedy, no one seemed restless. Kanno’s solo performance, also sold out, combined nightclub-styled blues and jazz riffs with an animated set that transformed her piano into a cat and a screen for quivering hearts.

“There’s a special atmosphere (at Otakon) that is about the vibrancy of the community,” says Christopher Macdonald, publisher of Anime News Network, the largest English-language portal for news about the anime industry. “People here can be themselves. Even the structure of the venue, with lots of outdoor space that is protected and safe, gives cosplayers a chance to pose and take photos without fear. It’s crowd-sourced fun.”

Of course, with fandom at the forefront, being a guest at an anime convention is a bit like being a performer on a cruise ship: Most are happy you’re there, and some will actually seek you out, but their first priority is to have a good time.

At the closing dinner, a private affair after the event had officially ended, staffers were thanked, guests were honored and glasses were raised. Though I had only been there for four days (landing one day early to prep before the chaos), I did feel like part of the community — a minor cast member, at least, who managed to play his role in a short scene of an epic drama.

Fittingly, the final announcement signaled a big step forward — to 2017, when Otakon will move into bigger, more modern venues in nearby Washington, D.C. And the closing toast was to Matt Pyson — the only Otakon volunteer who had served on staff for each and every one of its 20 years, from 1993.

“Cheers!” rose the voices, and before the glasses clinked, “Kampai!”

Roland Kelts is the author of

Published on August 15, 2013 21:27

August 8, 2013

On Caroline Kennedy as US Ambassador to Japan for TIME

Tokyo Doesn’t Care Who the U.S. Ambassador Is (but Caroline Kennedy Will Do Fine)

By Roland Kelts for Time

Caroline Kennedy

BRIAN SNYDER / REUTERS

Caroline Kennedy speaks at the 2013 John F. Kennedy Profile in Courage Award ceremony at the Kennedy Library in Boston on May 5, 2013

The Kennedys are the last big dynastic name in American politics. With no more Nixons to kick around and the Reagan offspring reduced to infighting, the Kennedys still have clout — which also makes them reliable targets for pundits. Not surprisingly, President Obama’s nomination last month of Caroline, the only surviving child of assassinated former President John F. Kennedy, as the next U.S. ambassador to Japan has raised both eyebrows and hackles.

I was in Boston when the news broke. Home of the hagiographic John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, the city, and its state Massachusetts, are liberal and intellectual bastions of Kennedy boosterism. The family long made Massachusetts its home base, literally, symbolically and politically, and John’s deceased younger brother, Caroline’s Uncle Ted, was its most famous and strident Senator.

Local media embraced Caroline Kennedy’s nomination. Boston University professor of international relations, Thomas Berger, cited three critical assets of a Kennedy ambassadorship to Japan: celebrity status, direct access to Obama and gender.

“Japanese women continue to look for role models who demonstrate that it is possible to be a woman and have a successful career in politics,” Berger told the Associated Press. “I expect that many in both the United States and in Japan will want to use her to send that message to the Japanese public.”

But Kennedy’s critics are less charitable, and sometimes brutal. “The argument that having a female ambassador will make a noticeable difference in the lives of Japanese women is insulting and off the mark,” says Tobias Harris, an expert in Japanese politics and author of the blog Observing Japan. “The problem for Japanese women is not the absence of role models — it’s structural forces that force women to choose between career ambitions and family life, and employers who view women as second-class workers responsible for fetching tea for the men no matter how high they rise. The gender of the U.S. ambassador will not change those things.”

Kennedy has no foreign policy experience, her critics add, and zero Japan expertise. She is a mere political appointee, offered an ambassadorship for merely being a high-profile supporter of the President during his 2008 campaign. The Kennedy nomination marks the first time in history, sniffs David Rothkopf, “that an individual has been nominated for a top ambassadorial post primarily for having written [a pro-Obama] opinion column.”

Yet that’s not how it looks on the other side of the Pacific. I was born and raised in the U.S., largely in New England, the region most possessive of, and devoted to, the Kennedy story. But my mother is Japanese, and I have lived in Japan for much of my adult life and a portion of my childhood.

The Japanese government issued a statement welcoming Kennedy’s nomination as a sign of the importance the U.S. government assigns to Japan — no small gesture amid ongoing insecurities over its rising neighbors, China and South Korea. (When former President Bill Clinton skipped Japan en route to China in 1998, the ominous phrase “Japan passing” emerged amid considerable hand-wringing in Tokyo diplomatic circles.)

And to Japanese of a certain generation, the Kennedy name resonates positively. John F. Kennedy sent his brother Robert to Japan on a goodwill tour in the early 1960s to shore up support for the U.S.-Japan security alliance, in place to this day, and dine on a little whale meat with the locals. President Kennedy’s own ambassador to Japan, Harvard professor Edwin O. Reischauer, was born and raised in the country, spoke the language, and with his Japanese wife, reached out to ordinary Japanese to forge an “equal partnership” between nations.

Today, with some 40,000 U.S. troops stationed in Japan, escalating territorial disputes with China and South Korea, and the North Korean nuclear threat, it’s doubtful the Japanese government would object to nearly any candidate Obama proposed — foreign policy wonk, big-pocket donor or best buddy. What’s more, the current U.S. Ambassador to Japan, the lawyer, Obama campaign supporter and presidential friend John Roos, has quietly performed his duties with spectacular results. With no foreign policy experience or Japan expertise, Roos became the first U.S. diplomat to attend the annual Hiroshima memorial in 2010 and was the face of U.S. relief efforts following Japan’s triple earthquake, tsunami and nuclear disasters in 2011.

“[Kennedy] has a hard act to follow,” says Jeff Kingston, director of Asian Studies at Temple University Japan in Tokyo. “Ambassador Roos has exceeded expectations and contributed greatly to strengthening bilateral ties. His actions in the wake of the tsunami gained the respect and admiration of the Japanese people.”

The real story here may be one of old-school American hubris — believing that it should even matter whether a U.S. ambassador would be a help or a hindrance. Japan has its own troubles to deal with; the identity of America’s new representative — male, female, diplomat or donor — in a long-standing, militarily dependent and deeply rooted alliance doesn’t matter that much overall in the world’s fastest growing region, and a potentially explosive one at that. One friend in Japan conceded that she didn’t even know there were any Kennedys left to serve.

“It’s true she doesn’t have the financial or political background that typically goes with the ambassadorship,” says Susan J. Napier, professor of Japanese Studies at Tufts University and author of several books about Japanese culture and art. “But she is very smart, cultured, and well-read — all things that are still extremely important to the Japanese elite, so I think she will fit in very well. She also has class — she will not be the kind of American bull in a china shop that is particularly unappealing to the Japanese.”

In an attempt to make them comprehensible to Western sensibilities, Asians have for centuries had their thoughts and utterances translated and transfigured by Western men, who have often handled them clumsily and shattered a few ornaments in the process. Perhaps a capable and diplomatic American woman with few preconceptions, whatever her surname, can help at last to keep the china intact.

Kelts is the author of

By Roland Kelts for Time

Caroline Kennedy

BRIAN SNYDER / REUTERS

Caroline Kennedy speaks at the 2013 John F. Kennedy Profile in Courage Award ceremony at the Kennedy Library in Boston on May 5, 2013

The Kennedys are the last big dynastic name in American politics. With no more Nixons to kick around and the Reagan offspring reduced to infighting, the Kennedys still have clout — which also makes them reliable targets for pundits. Not surprisingly, President Obama’s nomination last month of Caroline, the only surviving child of assassinated former President John F. Kennedy, as the next U.S. ambassador to Japan has raised both eyebrows and hackles.

I was in Boston when the news broke. Home of the hagiographic John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, the city, and its state Massachusetts, are liberal and intellectual bastions of Kennedy boosterism. The family long made Massachusetts its home base, literally, symbolically and politically, and John’s deceased younger brother, Caroline’s Uncle Ted, was its most famous and strident Senator.

Local media embraced Caroline Kennedy’s nomination. Boston University professor of international relations, Thomas Berger, cited three critical assets of a Kennedy ambassadorship to Japan: celebrity status, direct access to Obama and gender.

“Japanese women continue to look for role models who demonstrate that it is possible to be a woman and have a successful career in politics,” Berger told the Associated Press. “I expect that many in both the United States and in Japan will want to use her to send that message to the Japanese public.”

But Kennedy’s critics are less charitable, and sometimes brutal. “The argument that having a female ambassador will make a noticeable difference in the lives of Japanese women is insulting and off the mark,” says Tobias Harris, an expert in Japanese politics and author of the blog Observing Japan. “The problem for Japanese women is not the absence of role models — it’s structural forces that force women to choose between career ambitions and family life, and employers who view women as second-class workers responsible for fetching tea for the men no matter how high they rise. The gender of the U.S. ambassador will not change those things.”

Kennedy has no foreign policy experience, her critics add, and zero Japan expertise. She is a mere political appointee, offered an ambassadorship for merely being a high-profile supporter of the President during his 2008 campaign. The Kennedy nomination marks the first time in history, sniffs David Rothkopf, “that an individual has been nominated for a top ambassadorial post primarily for having written [a pro-Obama] opinion column.”

Yet that’s not how it looks on the other side of the Pacific. I was born and raised in the U.S., largely in New England, the region most possessive of, and devoted to, the Kennedy story. But my mother is Japanese, and I have lived in Japan for much of my adult life and a portion of my childhood.

The Japanese government issued a statement welcoming Kennedy’s nomination as a sign of the importance the U.S. government assigns to Japan — no small gesture amid ongoing insecurities over its rising neighbors, China and South Korea. (When former President Bill Clinton skipped Japan en route to China in 1998, the ominous phrase “Japan passing” emerged amid considerable hand-wringing in Tokyo diplomatic circles.)

And to Japanese of a certain generation, the Kennedy name resonates positively. John F. Kennedy sent his brother Robert to Japan on a goodwill tour in the early 1960s to shore up support for the U.S.-Japan security alliance, in place to this day, and dine on a little whale meat with the locals. President Kennedy’s own ambassador to Japan, Harvard professor Edwin O. Reischauer, was born and raised in the country, spoke the language, and with his Japanese wife, reached out to ordinary Japanese to forge an “equal partnership” between nations.

Today, with some 40,000 U.S. troops stationed in Japan, escalating territorial disputes with China and South Korea, and the North Korean nuclear threat, it’s doubtful the Japanese government would object to nearly any candidate Obama proposed — foreign policy wonk, big-pocket donor or best buddy. What’s more, the current U.S. Ambassador to Japan, the lawyer, Obama campaign supporter and presidential friend John Roos, has quietly performed his duties with spectacular results. With no foreign policy experience or Japan expertise, Roos became the first U.S. diplomat to attend the annual Hiroshima memorial in 2010 and was the face of U.S. relief efforts following Japan’s triple earthquake, tsunami and nuclear disasters in 2011.

“[Kennedy] has a hard act to follow,” says Jeff Kingston, director of Asian Studies at Temple University Japan in Tokyo. “Ambassador Roos has exceeded expectations and contributed greatly to strengthening bilateral ties. His actions in the wake of the tsunami gained the respect and admiration of the Japanese people.”

The real story here may be one of old-school American hubris — believing that it should even matter whether a U.S. ambassador would be a help or a hindrance. Japan has its own troubles to deal with; the identity of America’s new representative — male, female, diplomat or donor — in a long-standing, militarily dependent and deeply rooted alliance doesn’t matter that much overall in the world’s fastest growing region, and a potentially explosive one at that. One friend in Japan conceded that she didn’t even know there were any Kennedys left to serve.

“It’s true she doesn’t have the financial or political background that typically goes with the ambassadorship,” says Susan J. Napier, professor of Japanese Studies at Tufts University and author of several books about Japanese culture and art. “But she is very smart, cultured, and well-read — all things that are still extremely important to the Japanese elite, so I think she will fit in very well. She also has class — she will not be the kind of American bull in a china shop that is particularly unappealing to the Japanese.”

In an attempt to make them comprehensible to Western sensibilities, Asians have for centuries had their thoughts and utterances translated and transfigured by Western men, who have often handled them clumsily and shattered a few ornaments in the process. Perhaps a capable and diplomatic American woman with few preconceptions, whatever her surname, can help at last to keep the china intact.

Kelts is the author of

Published on August 08, 2013 15:35

August 6, 2013

On Hiroshima, 2013, for The New Yorker

Fragments of Hiroshima

By

for The New Yorker

The first time I visited the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, I carried a notebook and a sense of dread. The mood was as solemn as I expected, but the place was crowded and not very peaceful. Visitors were silently urged to go with the flow, move in step with others and not linger too long.

The first time I visited the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, I carried a notebook and a sense of dread. The mood was as solemn as I expected, but the place was crowded and not very peaceful. Visitors were silently urged to go with the flow, move in step with others and not linger too long.

The displays were impressively well kept—maybe too well kept. There were life-size dioramas of bloodied victims trudging barefoot through ashen sludge; massive models of the city as it was, pinpointing the exact location of ground zero; bent and crushed watches and clocks frozen to the moment—8:15 A.M., August 6, 1945.

That all the carefully curated and eye-catching exhibits felt like part of a Hiroshima theme park was probably unavoidable.

“A lot of people died instantly,” I wrote. Trying to soothe burning skin, some died in the river when fireballs swept up the oil-slicked water. Others died years later, stricken by cancer. Lots of letters were written by Hiroshima mayors, global politicians, and civilians, begging the world and the powers that be to not let it happen again.

I wanted to write that the bombing was unthinkable, or something equally righteous. But, of course, it was very thinkable. It had happened, not once but twice, and could easily happen again. The museum was there to make us think about that banality.

But one object pierced me. I kept circling back to it, leaving and rejoining the flow, nodding politely to the guards as I ducked past: a neatly folded Japanese schoolboy’s uniform—modeled, as they are today, on nineteenth-century European naval dress—had been blown out in quarter-sized patches from the inside, so that sharp spikes of its fabric reached up toward the glass and viewer.

Part of my fascination was personal. I’d been teaching at a few Japanese junior and senior high schools that year where the boys wore the very same jackets to class each day, with their formal high-necked collars and rigid lines projecting a sense of adolescent duty and conformity.

But it was also the one artifact that made me imagine being that specific boy on that specific morning, buttoning up that jacket and walking to school, and what it might feel like to have your body blown apart from within, as if the bomb had detonated inside your chest and bowels.

I was similarly mesmerized when watching the director Linda Hoaglund’s latest documentary film, “Things Left Behind,” which opened in Tokyo last month and in Hiroshima this weekend, to coincide with the sixty-eighth anniversary of the bombing. Ostensibly a chronicle of “ひろしま hiroshima,” an exhibition of forty-eight color prints by the photographer Miyako Ishiuchi, in Vancouver, in 2011 and 2012, the film is an urgent reminder of the role of contemplation in evoking feeling from history. Ishiuchi’s photographs of clothing and personal effects left behind by the dead are naturally lit and dreamlike, plucked from the unconscious, rendered against white backgrounds and fluttering through space and time.

Visitors to the museum confront the photographs as if hit by klieg lights. This is not the Hiroshima of bloodied sculptures, corpse-strewn black-and-white rubble-scapes, mushroom clouds, and denuded domes. It’s colorful and fashionable—but between the folds of disembodied silk blouses and dinner jackets, in the hollow eyes of an abandoned Ichimatsu doll, and between the sleeves of a child’s kimono, something is missing, absent, incomplete. We want to fill it in.

There is no voiceover; the photos are uncaptioned. “I wonder who wore this,” the voice of a visitor says, poring over a man’s jacket. Eyeing a scarred and beaten-up boot, a woman says, “Did it have laces, and what happened to them?”

The power of imagery can be subverted by proliferation and reach. The mushroom cloud and the skeletal Hiroshima dome are the two most recognizable pictures of Hiroshima, which remains a profound and endless human tragedy. But who really sees them?

In an oft-quoted passage from his 1985 novel, “White Noise,” Don DeLillo imagined “the most photographed barn in America.” “No one sees the barn,” he writes. “Once you’ve seen the signs about the barn, it becomes impossible to see the barn. We’re not here to capture an image, we’re here to maintain one.”

The Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum maintains the bomb’s signs, often admirably. But sixty-eight years later, the story of Hiroshima, its possible meanings and emotions, are fast becoming dead artifacts, especially in Japan, where the platitudes and memorials are broadcast live once every year, dominating the airwaves with about as much salient impact as the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade. It’s the most photographed A-bomb site in the world.

“I can’t photograph the past,” Ishiuchi tells a curator from Vancouver in the film. “Only the present. So it’s up to the viewers to bring their own memories to the images.”

“Things Left Behind” records more than just objects. It records stories as objects, all connected to Hiroshima: the disinvestment and relocation of Japanese living in Canada during the Second World War, none of whom have been compensated for their losses. The mining of uranium in northwest Canada by the Dene tribes, native to the region, who had no idea that they were supporting the Manhattan project, and whose contribution to the bomb inspired their apologetic missions to Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1998.

“I developed my approach by photographing my mother’s lingerie,” Ishiuchi tells me from Hiroshima, referring to her series, “Mother’s,” depicting personal artifacts from her deceased parent. “She left it behind after she passed away, [and I discovered] in that process that objects left behind by humans speak to me. Things left behind are eloquent. They speak to me and I hear them. Things are created for people to use, and things exist for humans. Once their user vanishes, the things should vanish, too. But these personal effects have outlived the persons who used them. The question is: Why?”

Hoaglund’s relationship to Hiroshima is both more transcultural and more intimate. Born and raised in Japan as the child of American missionaries, she was startled one day when her Japanese teacher addressed Hiroshima and the atomic bomb in the classroom. Her Japanese classmates stared her down—a tall fourth grader with blond hair—and she never wanted to visit Hiroshima.

“I wanted to dig a hole under my desk,” she says now. “Learning that you belong to a country that has blood on its hands. It disfigured my conscience.”

In 2010, Jon Michaud introduced John Hersey's classic, “Hiroshima,” which is available for subscribers to read.

Roland Kelts is the author of “

Credit: Miyako Ishiuchi.

Read more: http://www.newyorker.com/online/blogs/culture/2013/08/the-details-of-hiroshima.html?printable=true¤tPage=all#ixzz2bEUboNc5

By

for The New Yorker

The first time I visited the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, I carried a notebook and a sense of dread. The mood was as solemn as I expected, but the place was crowded and not very peaceful. Visitors were silently urged to go with the flow, move in step with others and not linger too long.

The first time I visited the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, I carried a notebook and a sense of dread. The mood was as solemn as I expected, but the place was crowded and not very peaceful. Visitors were silently urged to go with the flow, move in step with others and not linger too long. The displays were impressively well kept—maybe too well kept. There were life-size dioramas of bloodied victims trudging barefoot through ashen sludge; massive models of the city as it was, pinpointing the exact location of ground zero; bent and crushed watches and clocks frozen to the moment—8:15 A.M., August 6, 1945.

That all the carefully curated and eye-catching exhibits felt like part of a Hiroshima theme park was probably unavoidable.

“A lot of people died instantly,” I wrote. Trying to soothe burning skin, some died in the river when fireballs swept up the oil-slicked water. Others died years later, stricken by cancer. Lots of letters were written by Hiroshima mayors, global politicians, and civilians, begging the world and the powers that be to not let it happen again.

I wanted to write that the bombing was unthinkable, or something equally righteous. But, of course, it was very thinkable. It had happened, not once but twice, and could easily happen again. The museum was there to make us think about that banality.

But one object pierced me. I kept circling back to it, leaving and rejoining the flow, nodding politely to the guards as I ducked past: a neatly folded Japanese schoolboy’s uniform—modeled, as they are today, on nineteenth-century European naval dress—had been blown out in quarter-sized patches from the inside, so that sharp spikes of its fabric reached up toward the glass and viewer.

Part of my fascination was personal. I’d been teaching at a few Japanese junior and senior high schools that year where the boys wore the very same jackets to class each day, with their formal high-necked collars and rigid lines projecting a sense of adolescent duty and conformity.

But it was also the one artifact that made me imagine being that specific boy on that specific morning, buttoning up that jacket and walking to school, and what it might feel like to have your body blown apart from within, as if the bomb had detonated inside your chest and bowels.

I was similarly mesmerized when watching the director Linda Hoaglund’s latest documentary film, “Things Left Behind,” which opened in Tokyo last month and in Hiroshima this weekend, to coincide with the sixty-eighth anniversary of the bombing. Ostensibly a chronicle of “ひろしま hiroshima,” an exhibition of forty-eight color prints by the photographer Miyako Ishiuchi, in Vancouver, in 2011 and 2012, the film is an urgent reminder of the role of contemplation in evoking feeling from history. Ishiuchi’s photographs of clothing and personal effects left behind by the dead are naturally lit and dreamlike, plucked from the unconscious, rendered against white backgrounds and fluttering through space and time.

Visitors to the museum confront the photographs as if hit by klieg lights. This is not the Hiroshima of bloodied sculptures, corpse-strewn black-and-white rubble-scapes, mushroom clouds, and denuded domes. It’s colorful and fashionable—but between the folds of disembodied silk blouses and dinner jackets, in the hollow eyes of an abandoned Ichimatsu doll, and between the sleeves of a child’s kimono, something is missing, absent, incomplete. We want to fill it in.

There is no voiceover; the photos are uncaptioned. “I wonder who wore this,” the voice of a visitor says, poring over a man’s jacket. Eyeing a scarred and beaten-up boot, a woman says, “Did it have laces, and what happened to them?”

The power of imagery can be subverted by proliferation and reach. The mushroom cloud and the skeletal Hiroshima dome are the two most recognizable pictures of Hiroshima, which remains a profound and endless human tragedy. But who really sees them?

In an oft-quoted passage from his 1985 novel, “White Noise,” Don DeLillo imagined “the most photographed barn in America.” “No one sees the barn,” he writes. “Once you’ve seen the signs about the barn, it becomes impossible to see the barn. We’re not here to capture an image, we’re here to maintain one.”

The Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum maintains the bomb’s signs, often admirably. But sixty-eight years later, the story of Hiroshima, its possible meanings and emotions, are fast becoming dead artifacts, especially in Japan, where the platitudes and memorials are broadcast live once every year, dominating the airwaves with about as much salient impact as the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade. It’s the most photographed A-bomb site in the world.

“I can’t photograph the past,” Ishiuchi tells a curator from Vancouver in the film. “Only the present. So it’s up to the viewers to bring their own memories to the images.”

“Things Left Behind” records more than just objects. It records stories as objects, all connected to Hiroshima: the disinvestment and relocation of Japanese living in Canada during the Second World War, none of whom have been compensated for their losses. The mining of uranium in northwest Canada by the Dene tribes, native to the region, who had no idea that they were supporting the Manhattan project, and whose contribution to the bomb inspired their apologetic missions to Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1998.

“I developed my approach by photographing my mother’s lingerie,” Ishiuchi tells me from Hiroshima, referring to her series, “Mother’s,” depicting personal artifacts from her deceased parent. “She left it behind after she passed away, [and I discovered] in that process that objects left behind by humans speak to me. Things left behind are eloquent. They speak to me and I hear them. Things are created for people to use, and things exist for humans. Once their user vanishes, the things should vanish, too. But these personal effects have outlived the persons who used them. The question is: Why?”

Hoaglund’s relationship to Hiroshima is both more transcultural and more intimate. Born and raised in Japan as the child of American missionaries, she was startled one day when her Japanese teacher addressed Hiroshima and the atomic bomb in the classroom. Her Japanese classmates stared her down—a tall fourth grader with blond hair—and she never wanted to visit Hiroshima.

“I wanted to dig a hole under my desk,” she says now. “Learning that you belong to a country that has blood on its hands. It disfigured my conscience.”

In 2010, Jon Michaud introduced John Hersey's classic, “Hiroshima,” which is available for subscribers to read.

Roland Kelts is the author of “

Credit: Miyako Ishiuchi.

Read more: http://www.newyorker.com/online/blogs/culture/2013/08/the-details-of-hiroshima.html?printable=true¤tPage=all#ixzz2bEUboNc5

Published on August 06, 2013 16:02

August 5, 2013

OTAKON, Ole!

Date

Start

End

NameLocation

9-Aug-13

11:15 AM

12:15 PM

Anime vs Hollywood [G]Panel 4 (BCC 341-342)

9-Aug-13

12:30 PM

1:30 PMOpening CeremoniesPanel 2 (Ballroom II-III)

10-Aug-13

2:30 PM 3:30 PMAnime's Online Expansion [G]Panel 1 (BCC 314-315)

11-Aug-13

11:15 AM

12:15 PM

Anime After The Quake [G]Panel 5 (Hilton Holiday Ballroom 4-6)

Published on August 05, 2013 17:30

August 1, 2013

My feature story on Haruki Murakami for Newsweek Japan

Published on August 01, 2013 15:37

July 31, 2013

Japan throws cash at pop culture -- pop culture responds: my Japan Times column

latest column for

The Japan Times

:

Can METI’s ¥50 billion fund unfreeze ‘Cool Japan’?

BY ROLAND KELTS

Naysaying is almost always risk-free, especially if you do it online. If you’re a cynic, you’re usually right, and if you’re wrong, you can just delete those errant tweets and posts and join the party.

So last month, when Japan’s Upper House rubber-stamped a culture-promotion fund called Cool Japan, I expected little more than bemused shrugs from the anime industry and scorn from Internet otaku (fanboys).

Kyary Pamyu Pamyu

The government has been trumpeting its support of Japanese pop culture since at least 2002, when journalist Douglas McGray’s essay, “Japan’s Gross National Cool,” helped awaken politicians to a post-manufacturing path to global relevance. At the time, populist Prime Minister Junichiro Koizumi, an Elvis fan with a storm-trooper-like helmet of gray hair, announced that Japan would be King of content par excellence.

Here’s what happened: Doraemon, the blue cat character from the series of the same name, which has rarely aired in English-speaking countries, was chosen by the government as Japan’s “anime ambassador.” The following year, three girl-next-door models dressed as a Lolita, a Harajuku-girl and a schoolgirl posed for photographers at the Japan Expo in Paris. But they weren’t cosplaying; they were there as government-sponsored “kawaii (cute) ambassadors of Japan.”

In 2009, a British radio program interviewed me in Tokyo on the significance of then-Prime Minister Taro Aso’s proposed National Center for Media Arts — what the media called the Manga Museum. This would be the first major government-sanctioned repository for Japan’s popular arts post-1945, aimed at a new generation of tourists for whom Japanese pop culture was not merely cool, but worthy of curation and study.

Museum ground was never broken.

While Japan’s politicians came, went and fiddled — ordering overseas consulates to trim the ikebana lessons and polish their Pokémon — the nation’s content producers got burned. The economies of the United States and various other countries stalled, digitalization overtook media markets, and Japan’s population scrimped and shrank. The political will to organize and strategize support for Japanese content and its global appeal seemed to wilt.

Nothing looked promising, and in 2010 I wrote a

But in June of that same year, a young Stanford MBA graduate and employee of the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI) named Mika Takagi had gathered an eight-person staff to explore the potential of selling Japanese content abroad. Inspired by her encounters with IT creatives in Silicon Valley, she actually thought she could change Japan.

“I was talking about promoting design and content, and then there was this catchphrase floating around, ‘Cool Japan.’ And I thought — let’s use that to promote Japanese creativity and content and design, all in one package.”

When I met with Takagi at METI’s headquarters in Tokyo last month, she was ebullient, explaining that what had hamstrung past government efforts to promote Japanese pop culture was a philosophical block. “We were always stuck in the manufacturing side of things,” she said. “It’s our native concept of monozukuri (making physical items well). But what we needed to do was move the content industry division and the creative industry divisions into an IP (intellectual property) division — putting creativity first, then finding profit.”

Before you yawn, consider the numbers, and the commitment: ¥50 billion ($500 million) over 20 years, with a target of ¥60 billion ($600 million) via private investor partnerships. For Japan, this is National Cool on steroids — or at the very least, stimulus.

Fans and friends on both sides of the world have voiced skepticism, some of it aimed at the slogan alone, an easy echo of the United Kingdom’s successful “Cool Britannia” pop push of the 1990s.

American fashion director, and The Japan Times’ fashion columnist, Misha Janette, summarized the culture chasm: “In Japan, it’s normal to tell people that something is cool, while in the West, you have to make people believe that they think it’s cool,” she said. “It’s going to take some heavy-duty localization, collaboration and compromise on Japan’s part to really get this to stick.”

But anime industry veterans in Japan were equivocal — if still snarky. “Where have (our politicians) been?” asked Masakazu Kubo, executive producer of “Pokémon” and director of publishing house Shogakukan’s character-business center. “Koizumi declared his support for Japanese contents while political posturing in 2002. I guess it’s better if they support us, instead of just censoring us.”

Yuji Nunokawa, founder and CEO of Studio Pierrot (animators of “Naruto” and “Bleach”) and vice president of the Association of Japanese Animators (AJA) called the fund “a great leap for Japan, because the government have never supported us in the past. But will they be flexible? Will they accommodate our needs? The anime industry is stagnant right now. We’re not producing new hits, and our future is not bright.”

I first heard of the new METI fund at a February lunch with Shinichiro Ishikawa, founder and representative director of Gonzo, one of Japan’s most ambitious and globally-minded studios. Ishikawa is an adviser to the fund, but even he gently hedged.

“Implementation is the key,” he told me recently. “The projects they choose to fund will mean everything — and they need to choose the right people to run things.”

There is hope, especially overseas, that the new fund will be driven by Japan’s 21st-century market realities. A smaller and less wealthy consumer class means, as Takagi says, “there will be no domestic growth, period.”

Seiji Horibuchi, founder of Viz Media and CEO of New People, a Japanese shopping and entertainment complex in San Francisco, is hoping the METI fund can help him host more live events, like this year’s fifth annual J-Pop Summit on July 27 and 28 — a showcase for Japanese culture, featuring fashion, food, design, style, anime, manga and film. Among this month’s special guests is Kyary Pamyu Pamyu, the Japanese pop YouTube phenomenon who comes closest to rivaling South Korean Psy.

Horibuchi, while hardly jaded, is still no easy cheerleader. “I hope that the money will not sink into an abyss filled with only corporate or big players,” he said. “I’d really like to believe in the (government’s) seriousness in taking a risk to make a real difference this time.”

The most sanguine of insiders is Jim Vowles, director of guests and industry relations at Otakon, the largest anime convention on the U.S East Coast, and among the nation’s most respected. Otakon, held annually in Baltimore, Maryland, will celebrate its 20th anniversary early next month, and will next year launch a sister event in Las Vegas, Nevada.

“I see two basic things Japan can do to hold onto its cool factor,” Vowles tells me. “Make sure the industry as a whole can survive the evolution to digital; and keep fresh talent coming up to keep making cool stuff.

“We have very real evidence that this approach works — 20 years of evidence. Otakon has given rakugo performers and shamisen players some of their broadest and most appreciative audiences, while drawing anime and manga fans, cosplayers, aritsts and scholars. From a marketing standpoint, we’re hitting every demographic you could wish for.”

The opposite of naysaying is, what — Yaysaying? And who would want to be caught doing that? As long as Japan can keep making cool stuff, let someone else call it what it is.

Roland Kelts is the author of

Can METI’s ¥50 billion fund unfreeze ‘Cool Japan’?

BY ROLAND KELTS

Naysaying is almost always risk-free, especially if you do it online. If you’re a cynic, you’re usually right, and if you’re wrong, you can just delete those errant tweets and posts and join the party.

So last month, when Japan’s Upper House rubber-stamped a culture-promotion fund called Cool Japan, I expected little more than bemused shrugs from the anime industry and scorn from Internet otaku (fanboys).

Kyary Pamyu Pamyu

The government has been trumpeting its support of Japanese pop culture since at least 2002, when journalist Douglas McGray’s essay, “Japan’s Gross National Cool,” helped awaken politicians to a post-manufacturing path to global relevance. At the time, populist Prime Minister Junichiro Koizumi, an Elvis fan with a storm-trooper-like helmet of gray hair, announced that Japan would be King of content par excellence.

Here’s what happened: Doraemon, the blue cat character from the series of the same name, which has rarely aired in English-speaking countries, was chosen by the government as Japan’s “anime ambassador.” The following year, three girl-next-door models dressed as a Lolita, a Harajuku-girl and a schoolgirl posed for photographers at the Japan Expo in Paris. But they weren’t cosplaying; they were there as government-sponsored “kawaii (cute) ambassadors of Japan.”

In 2009, a British radio program interviewed me in Tokyo on the significance of then-Prime Minister Taro Aso’s proposed National Center for Media Arts — what the media called the Manga Museum. This would be the first major government-sanctioned repository for Japan’s popular arts post-1945, aimed at a new generation of tourists for whom Japanese pop culture was not merely cool, but worthy of curation and study.

Museum ground was never broken.

While Japan’s politicians came, went and fiddled — ordering overseas consulates to trim the ikebana lessons and polish their Pokémon — the nation’s content producers got burned. The economies of the United States and various other countries stalled, digitalization overtook media markets, and Japan’s population scrimped and shrank. The political will to organize and strategize support for Japanese content and its global appeal seemed to wilt.

Nothing looked promising, and in 2010 I wrote a

But in June of that same year, a young Stanford MBA graduate and employee of the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI) named Mika Takagi had gathered an eight-person staff to explore the potential of selling Japanese content abroad. Inspired by her encounters with IT creatives in Silicon Valley, she actually thought she could change Japan.

“I was talking about promoting design and content, and then there was this catchphrase floating around, ‘Cool Japan.’ And I thought — let’s use that to promote Japanese creativity and content and design, all in one package.”

When I met with Takagi at METI’s headquarters in Tokyo last month, she was ebullient, explaining that what had hamstrung past government efforts to promote Japanese pop culture was a philosophical block. “We were always stuck in the manufacturing side of things,” she said. “It’s our native concept of monozukuri (making physical items well). But what we needed to do was move the content industry division and the creative industry divisions into an IP (intellectual property) division — putting creativity first, then finding profit.”

Before you yawn, consider the numbers, and the commitment: ¥50 billion ($500 million) over 20 years, with a target of ¥60 billion ($600 million) via private investor partnerships. For Japan, this is National Cool on steroids — or at the very least, stimulus.

Fans and friends on both sides of the world have voiced skepticism, some of it aimed at the slogan alone, an easy echo of the United Kingdom’s successful “Cool Britannia” pop push of the 1990s.

American fashion director, and The Japan Times’ fashion columnist, Misha Janette, summarized the culture chasm: “In Japan, it’s normal to tell people that something is cool, while in the West, you have to make people believe that they think it’s cool,” she said. “It’s going to take some heavy-duty localization, collaboration and compromise on Japan’s part to really get this to stick.”

But anime industry veterans in Japan were equivocal — if still snarky. “Where have (our politicians) been?” asked Masakazu Kubo, executive producer of “Pokémon” and director of publishing house Shogakukan’s character-business center. “Koizumi declared his support for Japanese contents while political posturing in 2002. I guess it’s better if they support us, instead of just censoring us.”

Yuji Nunokawa, founder and CEO of Studio Pierrot (animators of “Naruto” and “Bleach”) and vice president of the Association of Japanese Animators (AJA) called the fund “a great leap for Japan, because the government have never supported us in the past. But will they be flexible? Will they accommodate our needs? The anime industry is stagnant right now. We’re not producing new hits, and our future is not bright.”

I first heard of the new METI fund at a February lunch with Shinichiro Ishikawa, founder and representative director of Gonzo, one of Japan’s most ambitious and globally-minded studios. Ishikawa is an adviser to the fund, but even he gently hedged.

“Implementation is the key,” he told me recently. “The projects they choose to fund will mean everything — and they need to choose the right people to run things.”

There is hope, especially overseas, that the new fund will be driven by Japan’s 21st-century market realities. A smaller and less wealthy consumer class means, as Takagi says, “there will be no domestic growth, period.”

Seiji Horibuchi, founder of Viz Media and CEO of New People, a Japanese shopping and entertainment complex in San Francisco, is hoping the METI fund can help him host more live events, like this year’s fifth annual J-Pop Summit on July 27 and 28 — a showcase for Japanese culture, featuring fashion, food, design, style, anime, manga and film. Among this month’s special guests is Kyary Pamyu Pamyu, the Japanese pop YouTube phenomenon who comes closest to rivaling South Korean Psy.

Horibuchi, while hardly jaded, is still no easy cheerleader. “I hope that the money will not sink into an abyss filled with only corporate or big players,” he said. “I’d really like to believe in the (government’s) seriousness in taking a risk to make a real difference this time.”

The most sanguine of insiders is Jim Vowles, director of guests and industry relations at Otakon, the largest anime convention on the U.S East Coast, and among the nation’s most respected. Otakon, held annually in Baltimore, Maryland, will celebrate its 20th anniversary early next month, and will next year launch a sister event in Las Vegas, Nevada.

“I see two basic things Japan can do to hold onto its cool factor,” Vowles tells me. “Make sure the industry as a whole can survive the evolution to digital; and keep fresh talent coming up to keep making cool stuff.

“We have very real evidence that this approach works — 20 years of evidence. Otakon has given rakugo performers and shamisen players some of their broadest and most appreciative audiences, while drawing anime and manga fans, cosplayers, aritsts and scholars. From a marketing standpoint, we’re hitting every demographic you could wish for.”

The opposite of naysaying is, what — Yaysaying? And who would want to be caught doing that? As long as Japan can keep making cool stuff, let someone else call it what it is.

Roland Kelts is the author of

Published on July 31, 2013 16:43

July 2, 2013

On the Japanese government's (METI's) new COOL JAPAN fund for Time magazine

Latest for TIME on METI's newly passed "Cool Japan" content fund and campaign.

Japan Spends Millions in Order to Be Cool

By Roland Kelts

Just as Washington shuts its stimulus chest, and with the economies of Europe tightening their purse strings in times of austerity, Tokyo’s wallet is suddenly very fat and visible. The object of its lavish spending this time is culture.

Japan’s upper house gave final approval on June 12 for a $500 million, 20-year fund to promote Japanese culture overseas. Called Cool Japan, the multidisciplinary campaign is designed to plug everything from anime and manga to Japanese movies, design, fashion, food and tourism. Overseen by the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI), the campaign will woo private investors later this year to hit an eventual target of $600 million. It’s unfortunate that the name of a campaign to showcase creative originality strongly echoes Cool Britannia, the pop-cultural flowering that took place in the U.K. in the 1990s, but it’s early days for Tokyo’s own soft-power push.

Naturally, there’s a bottom line. Creative content, says Mika Takagi of METI’s international-economic-affairs division, will “help sell goods.” One inspiration, she suggests, is South Korea. In 1998, according to METI, the South Korean government invested $500 million into a cultural-promotion fund. Fifteen years later, its artists dominate the pop-music charts in Asia, its television and movie titles are top sellers throughout the region, and the whole world knows a South Korean rapper named Psy. Even better, South Korean goods — think of Samsung phones or Hyundai cars — have become global successes, with an image that’s modern, young and fun.

“South Korea is keenly aware of the global reach of its entertainment content,” says Seiji Horibuchi, a pioneer in the business of marketing Japanese culture abroad who, in 1986, founded North America’s Viz Media, one of the first overseas distributors of Japanese manga, anime and popular culture. “They have created a successful model that Japan could emulate.”

Horibuchi’s latest venture is a bricks-and-mortar retail outlet: he is the CEO of New People, a Japanese pop-culture shopping mall located in San Francisco’s Japantown. “I hope [the METI fund] will bring a new Japanese star or hit property to the global market,” he adds, “but it takes time. It took us over 20 years to finally see anime and manga culture take root in the United States.”

Of course, many will ask why Tokyo should follow Seoul’s lead, given that Japanese design is internationally synonymous with chic, and such things as sushi, the films of Hayao Miyazaki and “cosplay” are already global phenomena. The answer, according to the Japan Times, is that Japan’s cultural exports have been of a random and piecemeal nature, and there has been no sustained attempt to exploit merchandising opportunities. This is because creative companies, in the main, tend to be small or medium-size and lack the resources to establish a global presence. Anime producers — responsible for one of the country’s best-known cultural exports — are struggling because of plummeting DVD sales, while the Asian regional market in content and electronics is dominated by South Korea and China.

Politically too, Japan is in an unenviable position. Its American ally won’t be the world’s only superpower for much longer. At the same time, Japan is both alien to and suspicious of its rising Asian neighbors. In this respect, the timing of Cool Japan makes sense. But the idea isn’t new. Since 2002, when a short essay by American journalist Douglas McGray titled “Japan’s Gross National Cool” was translated into Japanese and disseminated among politicians in Tokyo, the Japanese government has been hankering to promote its contemporary pop culture abroad, and there has been lot of chatter about Japan’s international “soft power” — the phrase coined in the late ’70s by former Harvard Professor Joseph S. Nye to denote the appeal of a culture’s sensibility and products, and the geopolitical influence that can accrue.

For years, however, official attempts to promote Japanese culture have been cringingly awkward. In 2008, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs chose an “anime ambassador,” a blue cartoon cat named Doraemon, whose domestically beloved television series has never aired in most English-speaking countries. One year later, it dubbed three young girl models in maid frills and short skirts the kawaii (supercute) ambassadors, sending them around the world as emissaries of Japanese fashion. Taro Aso, one of Japan’s many fly-by-night former PMs, announced with great fanfare in 2009 plans for the first national manga museum — which was abandoned shortly after he was.

Now, however, there is both political and economic impetus for getting it right. “This is more like a venture-capital fund,” says Chizuru Suga, deputy director of METI’s media-and-content-industry division and the current leader of the 50-employee Cool Japan fund. “In the past, support for Japanese content was relegated to old industrial divisions, manufacturers who didn’t really understand the meaning and value of intellectual property. Now we have a young staff, and we have vision and economic support, and we need to be responsible. We started researching this fund in 2010, and we think we have it right: use Japanese content to sell Japanese products.”

One veteran Japanese movie producer, who spoke to TIME on condition of anonymity, has a more cynical take. “The government money will be funneled into big Japanese corporations [and] advertising agencies like Dentsu and Hakuhodo,” he says, “and they will filter it away into their own accounts through paperwork. No real domestic artists will receive the money — and they are the ones who truly need it.”

Need is an understatement. As the author of a book about Japanese popular culture, I have been tracking the government’s actual commitment to it very closely. And while this new fund is unprecedented in size and hoopla, it does nothing to support Japanese artists domestically, many of whom labor in sweatshop conditions with unsustainable pay. Anime artists in their 20s, for example, make roughly $11,000 annually — living in one of the most expensive cities in the world.

“Those artists work for private companies,” counters Takagi. “If their companies are not successful, that’s not our fault.”

Maybe. But without domestic support, the content METI is counting on to drive its campaign may not be particularly inspired or forthcoming, and Cool Japan may meet with little more than a cool reception.

Kelts is the author of

>>for more, see

Published on July 02, 2013 01:28

June 11, 2013

On Japan's dying "tokusatsu" (SFX) tradition for my latest column in The Japan Times

CULTURE | CULTURE SMASH

Preserving a classic Japanese art form: tokusatsu magic

BY ROLAND KELTS

JUN 12, 2013

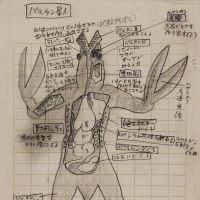

Our monster is scaly, spiky, reptilian — a cross between a dinosaur and an irradiated insect that shrieks like an angry bird. Our hero is lean, faintly muscular in a rubbery skintight suit with inscrutable praying-mantis eyes. They face one another, stomping left to right like sumo wrestlers, posing karate-style. The humans below clasp their hands in hope, their city fragile as cardboard.

When the battle begins, the urban landscape — a meticulously detailed scaled-down model — is in flames, its buildings easily smashed and tossed through the air. A few lasers and fireballs fly, but in short order monster and hero grapple, engaging in hand-to-hand combat, tumbling into one another, grabbing body parts and twisting, turning, punching. It’s mano-a-mano — and it’s thrilling.

Before anime and manga became Japan’s calling cards overseas, Japanese monster movies and TV shows were the face of its popular culture. I was a 6-year-old living with my Japanese grandparents in Morioka, Iwate Prefecture, when I got hooked on the “Ultraman” series. I usually watched it with my grandfather. They didn’t have an air conditioner at the time, so we both sat in our underwear on the tatami. After the monster and Ultraman grappled, we did, too.

Only later would I realize that the human physicality of the fights and the easily crushable model cities were essential to the appeal of the show, engaging my imagination actively in the fantasy. Tokusatsu, a Japanese term usually translated as “special effects” moviemaking, denotes the unique craft behind the Japanese monster movie and TV phenomenon. Other nations produced sci-fi epics and monster movies, of course, but no one did so with the style, élan and sometimes comic absurdity of Japan.

The original “Godzilla” movie, featuring special effects by Eiji Tsubaraya, is largely credited with establishing the tokusatsu look and style in 1954, distinguishing it from American science-fiction movies, which were dominant at the time. Now, nearly 60 years later, the tokusatsu tradition is dying.

Anno and his colleague, director Tomoo Haraguchi, released an urgent report late last month in connection with the government’s Agency for Cultural Affairs. Tokusatsu is not just special effects, they argue, it’s a cultural treasure.

As most fans now know, what is called “anime” outside of Japan is not just animation, and Japanese pop culture itself is not simply a mirror of Western entertainment. The former is a hybrid creation shaped by the sensibilities of a centuries-old nation. Enriched and emboldened by Western influences, yes, but still uniquely Japanese.

“Disney created the template for American animation,” says Ryusuke Hikawa, a critic and scholar of anime, manga and tokusatsu. “In the same way, (special-effects studio) Tsubaraya created the template for the Japanese movie business. It was their use of cheap but craftsman-like approaches to movie-making that made tokusatsu unique.”

The motivation behind Anno’s plea is obvious. A culture of creativity in Japan is being threatened by advances in digital production (specifically, CGI, which costs less in the long run and requires less labor, skill and craftsmanship), domestic diffidence (most Japanese have little appreciation of the global appeal of their homespun creativity) — and a declining birthrate. Anno and Haraguchi had a meeting last year during which they realized neither of them had kids, and no one is teaching, learning or inheriting the craft.

“A lot of the creative work on set design was outsourced to small mom-and-pop shops,” says manga translator and author Daniel Kanemitsu. “Those shop owners are dying now — they’re very old. And no one knows how to do what they did.”

Last year, three tokusatsu exhibitions were hosted around Tokyo, meant to inspire an appreciation of the aesthetic and craftsmanship behind Japanese monster and sci-fi films and shows. The centerpiece, director Anno’s “Tokusatsu — Special Effects Museum,” is now touring the country, and is currently at The Museum of Art, Ehime, in Matsuyama, Ehime Prefecture until June 23. On Nov. 8, it will open at Niigata Prefectural Musuem of Modern Art in Nagaoka, Niigata Prefecture.

The response to last summer’s Tokyo shows was overwhelming (I couldn’t get into one of them because of the crowds), but the inspiration behind them is dire.

“Just as Japan gave away its most valuable IP (intellectual property) in the form of ukiyo-e, anime and manga,” says Kanimitsu, “without appreciating their value at home, it is now killing tokusatsu without teaching a new generation the value of its own art.”

Hikawa believes that the tokusatsu industry has been hindered by two major movements in film — the international success of “Star Wars,” a sci-fi B movie that became an international sensation and created a new template for audience expectations, and the advent of CGI techniques, which supplanted monozukuri (handmade craftsmanship), with digital wizardy.

“But despite the success of CGI,” he tells me, “we’ve learned that children prefer the physicality of tokusatsu to digital imagery, especially when it comes to toys. CGI series are cheap to make and get lots of viewers, but they don’t sell toys. I think kids still want to buy toys that they can touch and feel.”

I asked my friend Matt Alt, author of several books on the relationship between Japanese pop and traditional culture, to define the essence of tokusatsu and explain why it should be saved in the 21st century.

“Japanese creators are more comfortable with abstraction,” he says. “Tokusatsu take a huge page from Japanese traditional arts like kabuki. Nobody would stand up and say in a kabuki performance, ‘This isn’t real.’ The entire (tokusatsu) concept of putting a guy in a suit has direct roots in kabuki theater, where giant monsters were actors in costumes.

“The situations in anime and tokusatsu couldn’t exist in real life. Just like woodblock prints utilize a 2-D portrayal of perspective that differs from the more ‘realistic’ forced perspective of Western art, yet are still considered masterpieces of illustration. It’s not about trying to compete with the realistic special effects in the West. It’s about feeling.”

To generations of artists and fans, losing that feeling and the creativity behind it to DVD box sets and YouTube clips would be a monstrosity.

Published on June 11, 2013 08:42

June 10, 2013

Social clubbing starts in Japan--my column for The Japan Times

CULTURE | CULTURE SMASH

Social clubbing takes off with iFlyer service

BY ROLAND KELTS

Clubbing in Japan is a kick. The country’s zeal for global pop trends and its prominent club scene draws big-name DJs and performers from the international circuit. Japan’s hodgepodge approach to urban planning means that clubs seem to blossom nearly anywhere — in the back alleys of unsung neighborhoods such as Tokyo’s Yoyogi, with its funky music haven, Zher the Zoo, or behind nondescript docks in the Hyogo Prefecture capital of Kobe. Despite recent crackdowns on after-hours dancing, Japan’s club scene continues to thrive past the midnight hour, buoyed by itinerant hipsters with wads of cash.

But knowing which clubs to go to, and how to get there, can be mystifying. If you’re like me, you stumble home in the wee hours clutching handfuls of flyers — brightly colored glossy paper rectangles luring you to the next night’s gig, sans context or reason. By breakfast, you won’t remember what they were supposed to mean or why you kept them.

The Internet has trimmed the paper chase a bit, but online adverts for nightlife still confuse. One person’s classifieds are another’s headache. Nice to know there’s lots to do — not so nice to not know what to do.

Malek Nasser, a British techie then based in Osaka, was one expat who wondered why the Japanese club scene was in such disarray, and thought he could do something about it. “In 2005-06, I was looking for something to do, and I moved to Tokyo. The scene in Osaka was more bar-based. But in Tokyo, I lived in Shibuya and I wandered around these streets, seeing big venues like Club Asia.”

Nasser noticed that each club ran its own website, but none of them were connected. Like their piles of glossy flyers, the clubs were promoting themselves in a chaotic shower of invites with great offerings, but little impact.

Nasser set out to make the greatest event website ever — and he used Tokyo and Osaka as his testing grounds. The result is iFlyer.tv, a user-generated Web portal with everything you need to know about nightlife in Tokyo and Osaka. And it’s now going global.

“When you actually have an event, it’s quite a complex machine,” Malek tells me in iFlyer’s Shibuya headquarters, a sleek and tidy third-floor media laboratory called the Music Technology Center.

“We have this kind of artists’ wiki, where artists and club owners input their details and profiles. We were worried at first that artists would try to deface others’ pages, but what happened was that the artists would input information and the clubs would correct them. It’s actually quite self-monitoring. They have their self-contained content-management systems.”

“The really important thing is getting the right people to the right venue,” adds Sach Jobb, Malek’s American partner in the iFlyer project. “We used some guerrilla tactics to get folks involved. We told people to mention iFlyer when they were going to clubs to get discounts. Even if they didn’t get discounts, the word got out.”

iFlyer is now a partner with Ticket Pia, Japan’s dominant ticketing agency, enabling them to work with the biggest names in the entertainment business. “We started explaining to them about iFlyer,” says Jobb, “and suddenly they said, ‘We already know about iFlyer, just tell us how we can work together.’ I was like, woah!”

“It was great,” adds Nasser, “a validation of what we’re doing. It was the transition from turning a hobby into a full-fledged company.”

iFlyer is a revelation for clubbers — Japan’s pop scene made accessible via its artists and promoters. Visit the site and use it in English or Japanese to find your personalized night of pleasure. And, like Facebook, Google and Twitter, it’s becoming more personalized. Nasser and Jobb have just launched myflyer — a personal page based on “likes” whose algorithms can shape a user’s nightlife plans according to their tastes and those of their friends.

“We were looking at the system and wondering how we list events and how we can do it better,” says Nasser. “We needed to try to make it relevant to everyone. How do we tailor it to specific users? We saw the writing on the wall — we needed to find a way to cut right to events you want to see. That’s where myflyer came from. And that’s where Star*d (a personalized recommendation system) emerged.

“Now we’re capitalizing on the recommendation side. It’s an algorithm that we program. It’s going to be learning more and more as time goes by. It’s similar to Amazon, but for events. And we’re going to include your social graph — which is what your friends like — as well.”

Nasser and Jobb are just getting started. iFlyer launched an English-only site for clubs and artists in London last month, and they have plans to do the same in Hong Kong, Singapore, Los Angeles and New York in the coming year. It’s an extraordinary example of how expat ventures that start in Japan can go global.

“We started iFlyer on Japanese mobile phones,” adds Jobb, “but now we’re shifting to all platforms.

“The fact is, this is a model that can be applied to all sorts of content — literature, anime, cosplay, whatever. We’re starting to incorporate theater events like ‘Lion King’ with Richie Hawtin at Club Womb. The possibilities are endless.”

Headed to Broadway, Roppongi or the West End? Ditch the paper. Click on iFlyer.tv and go.

Roland Kelts is the author of “Japanamerica: How Japanese Pop Culture has Invaded the U.S.” He is a Visiting Scholar at the University of Tokyo.

Published on June 10, 2013 09:03