Roland Kelts's Blog, page 44

November 8, 2013

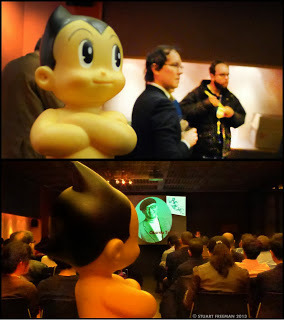

Last night in NYC -- Astro on the scene

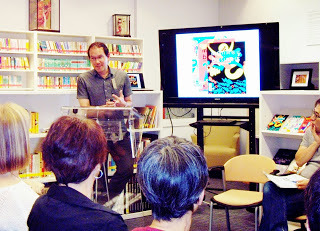

Photographer and friend Stuart Freeman found that Astro Boy/Tetsuwan Atomu was keeping a close eye on me as I talked about his creator, Osamu Tezuka, last night at The Japan Society in New York City. I was and remain humbled by their presence.

Published on November 08, 2013 16:57

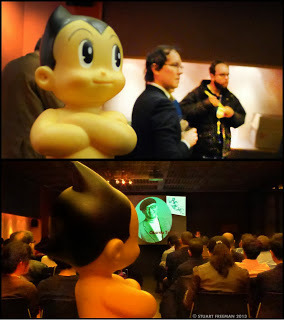

Last night in NYC -- Astro on the scene

Photographer and friend Stuart Freeman found that Astro Boy/Tetsuwan Atomu was keeping a close eye on me as I talked about his creator, Osamu Tezuka, last night at The Japan Society in New York City. I was and remain humbled by their presence.

Published on November 08, 2013 16:57

November 3, 2013

Talkin' Osamu Tezuka at The Japan Society of New York this Thursday, 11/7

Join me and NYC-based comic artist Katie Skelly for "The Life & Works of Osamu Tezuka" this Thursday, Nov. 7, at The Japan Society of New York. Next year marks the 25th Anniversary of Tezuka's death. Learn why he is still the consecrated "God of manga and anime."

Wine and Japanese hors d'oeuvres will be served. Copies of my dear friend Helen McCarthy's The Art of Osamu Tezuka, Ryan Holmberg's The Mysterious Underground Men (by Tezuka), Skelly's Nurse Nurse, and Japanamerica will be raffled off. Copies of Japanamerica will also be on sale, and a book-signing will follow.

Published on November 03, 2013 16:28

November 2, 2013

Koji & Junichi-- the 2013 Boston Red Sox

Published on November 02, 2013 21:08

October 27, 2013

Japanamerica meets the BBC on sex, men, anime, manga

Published on October 27, 2013 16:03

Japanamerica meets the BBC on sex, men, anime, manga

Published on October 27, 2013 16:03

October 8, 2013

Japan's right-wing backlash against Hayao Miyazaki for The Japan Times

Backlash against Miyazaki is generational

BY ROLAND KELTS

OCT, 2013

If you haven’t lived in Japan, it’s hard to appreciate just how beloved are anime maestro Hayao Miyazaki and his creative hub, Studio Ghibli.

Annual surveys of Japanese consumers often find that Ghibli is their favorite domestic brand, ahead of stalwarts such as Toyota and Sony. Miyazaki’s animated epics regularly top the domestic theatrical market. “Kaze Tachinu” (“The Wind Rises”), his latest film — loosely based on the life of engineer Jiro Horikoshi, designer of Japan’s wartime Zero fighter plane — soared above its box office rivals for seven consecutive weeks after its July release. Meanwhile, his Oscar-winning “Spirited Away” (2001) remains the top-grossing film in Japanese history, knocking aside Hollywood live-action contenders such as “Titanic” and the “Harry Potter” films.

In August, during a Japanese TV rebroadcast of Ghibli’s first full-length feature film, 1986′s “Laputa: Castle in the Sky,” viewers set a new Twitter world record for the number of tweets per second — easily surpassing the pre-existing tally set by fans of Beyoncé and her pregnancy announcement.

But the rest of the world has been catching up. Miyazaki’s retirement announcement last month reverberated globally. Over three decades, beginning with 1979′s “Castle of Cagliostro,” he has emerged as the greatest animator of his era, and some would say of all time. Audiences and journalists at the Venice Film Festival, where “The Wind Rises” received its worldwide premiere, were reportedly stunned into silence when Koji Hoshino, the president of Studio Ghibli, first revealed the news at a press conference. One prominent American critic likened the announcement to “an unexpected death notice.”

All of which makes this summer’s nationalistic backlash in Japan against Miyazaki and his colleagues’ remarks on Japan’s political and historical conundrums that much more startling — and revealing.

The July issue of Neppu, Ghibli’s free self-published monthly booklet, featured a special section on Prime Minister Shinzo Abe and his administration’s campaign to revise Japan’s pacifist Constitution. Miyazaki declared his unequivocal opposition to revising the war-renouncing Article 9. He also said that Japan should apologize for the so-called comfort women, the Imperial army’s corps of wartime sex slaves that remains a highly sensitive matter, especially between Japan and South Korea. And he argued that some sort of compromise must be sought over Japan’s escalating territorial disputes with China and South Korea, either by dividing the territories by mutual consent or administering joint control over them.

Anyone who has paid even passing attention to Miyazaki’s history of leftist postwar positions — and his willingness to speak out or act on them — might have anticipated this. After the earthquake, tsunami and meltdown disaster of 2011, Ghibli hung a banner from its rooftop announcing that it would “make movies with electricity that did not come from nuclear power.” And back in 1963, one year into his first job at Japanese animation giant Toei, Miyazaki got involved in a labor dispute and soon became chief secretary of Toei’s labor union.

But the reaction to Ghibli’s anti-war, anti-revisionist essays was ferocious, especially among Japan’s so-called netto uyoku, or right-wing Internet users. Japan’s most famous, popular and revered visual artist was called “dim-witted,” “a traitor” and “anti-Japanese.” Some said they would never see another Ghibli film. Others were sarcastic, with one commentator wondering if Miyazaki would pay for comfort women from the profits of his film.

There are deep generational tremors afoot. At 72, some of Miyazaki’s first memories were formed during wartime, and the extreme poverty and suffering of the aftermath. Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, 58, and his peers are better acquainted with a more recent (albeit far less violent and destructive) national trauma: the collapse of Japan’s bubble economy of the 1980s and the nation’s slow slide since then into financial and global irrelevance. The need to feel a resurgent national pride may be exacerbated by the double-whammy of a rising Asia and decline of Japan’s main ally, the United States.

“I can’t help thinking that this is a watershed time for Japan, and that the election of Abe has stirred up a lot of painful emotions,” says Susan J. Napier, professor of Japanese studies at Tufts University in Massachusetts and author of a forthcoming book on Miyazaki. “A lot of Japanese are mainly concerned about the economy, and Abe at least gives the impression of finally trying to make some radical changes. I think people are both hopeful and scared to hope.”

Anime, and its print cousin and forebear, manga, are primarily products of postwar Japan. The medium’s first superhero, “Astro Boy,” was created partly out of artist Osamu Tezuka’s desire to see nuclear technology used for peaceful purposes after the devastation of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Its first giant robot, “Tetsujin 28-go” (“Gigantor” in the West), was often depicted in original versions stomping through the New York City skyline. “Battleship Yamato,” one of the original series broadcast on American television, reimagined Japan’s sunken naval vessel as a retrofitted high-tech spaceship.

Ironically, “The Wind Rises” examines the complex and self-contradictory life of the engineer who created one of Japan’s most fearsome weapons — reflecting Miyazaki’s own contradictions. His father worked at Miyazaki Airplane, which made parts for Zero fighter planes, and Miyazaki has long been enamored of the mechanics of flight and aircraft.

At the film’s premiere screening at the New York Film Festival two weeks ago, I was struck by the story’s sustaining narrative tension. Every moment of Jiro’s dreamlike bliss about beauty is bombed to Earth with a brutal thud. Images of flight and transcendence, the artist’s reveries, are followed by scenes of wreckage and death, the artist’s nightmare. Jiro remains a cipher throughout — so devoted to his visions of possibility that he can’t see the horror burning at the periphery. At the moment of his greatest achievement, he loses the love of his life.

Author and translator Frederik L. Schodt, who has translated Miyazaki’s interviews and essays, believes that Miyazaki’s role is critical in uniting Japanese generations amid the country’s current identity crisis.

“At his age," Schodt says, "and with his status among youth, (Miyazaki) can be an important bridge between younger generations, whose historical knowledge of World War II is limited, and an older, fading generation, for whom it remains a searing and real memory."

“Kaze Tachinu” (“The Wind Rises”) is now showing in cinemas nationwide. Roland Kelts is the author of “Japanamerica: How Japanese Pop Culture has Invaded the U.S.” He is a visiting scholar at Keio University in Tokyo.

BY ROLAND KELTS

OCT, 2013

If you haven’t lived in Japan, it’s hard to appreciate just how beloved are anime maestro Hayao Miyazaki and his creative hub, Studio Ghibli.

Annual surveys of Japanese consumers often find that Ghibli is their favorite domestic brand, ahead of stalwarts such as Toyota and Sony. Miyazaki’s animated epics regularly top the domestic theatrical market. “Kaze Tachinu” (“The Wind Rises”), his latest film — loosely based on the life of engineer Jiro Horikoshi, designer of Japan’s wartime Zero fighter plane — soared above its box office rivals for seven consecutive weeks after its July release. Meanwhile, his Oscar-winning “Spirited Away” (2001) remains the top-grossing film in Japanese history, knocking aside Hollywood live-action contenders such as “Titanic” and the “Harry Potter” films.

In August, during a Japanese TV rebroadcast of Ghibli’s first full-length feature film, 1986′s “Laputa: Castle in the Sky,” viewers set a new Twitter world record for the number of tweets per second — easily surpassing the pre-existing tally set by fans of Beyoncé and her pregnancy announcement.

But the rest of the world has been catching up. Miyazaki’s retirement announcement last month reverberated globally. Over three decades, beginning with 1979′s “Castle of Cagliostro,” he has emerged as the greatest animator of his era, and some would say of all time. Audiences and journalists at the Venice Film Festival, where “The Wind Rises” received its worldwide premiere, were reportedly stunned into silence when Koji Hoshino, the president of Studio Ghibli, first revealed the news at a press conference. One prominent American critic likened the announcement to “an unexpected death notice.”

All of which makes this summer’s nationalistic backlash in Japan against Miyazaki and his colleagues’ remarks on Japan’s political and historical conundrums that much more startling — and revealing.

The July issue of Neppu, Ghibli’s free self-published monthly booklet, featured a special section on Prime Minister Shinzo Abe and his administration’s campaign to revise Japan’s pacifist Constitution. Miyazaki declared his unequivocal opposition to revising the war-renouncing Article 9. He also said that Japan should apologize for the so-called comfort women, the Imperial army’s corps of wartime sex slaves that remains a highly sensitive matter, especially between Japan and South Korea. And he argued that some sort of compromise must be sought over Japan’s escalating territorial disputes with China and South Korea, either by dividing the territories by mutual consent or administering joint control over them.

Anyone who has paid even passing attention to Miyazaki’s history of leftist postwar positions — and his willingness to speak out or act on them — might have anticipated this. After the earthquake, tsunami and meltdown disaster of 2011, Ghibli hung a banner from its rooftop announcing that it would “make movies with electricity that did not come from nuclear power.” And back in 1963, one year into his first job at Japanese animation giant Toei, Miyazaki got involved in a labor dispute and soon became chief secretary of Toei’s labor union.

But the reaction to Ghibli’s anti-war, anti-revisionist essays was ferocious, especially among Japan’s so-called netto uyoku, or right-wing Internet users. Japan’s most famous, popular and revered visual artist was called “dim-witted,” “a traitor” and “anti-Japanese.” Some said they would never see another Ghibli film. Others were sarcastic, with one commentator wondering if Miyazaki would pay for comfort women from the profits of his film.

There are deep generational tremors afoot. At 72, some of Miyazaki’s first memories were formed during wartime, and the extreme poverty and suffering of the aftermath. Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, 58, and his peers are better acquainted with a more recent (albeit far less violent and destructive) national trauma: the collapse of Japan’s bubble economy of the 1980s and the nation’s slow slide since then into financial and global irrelevance. The need to feel a resurgent national pride may be exacerbated by the double-whammy of a rising Asia and decline of Japan’s main ally, the United States.

“I can’t help thinking that this is a watershed time for Japan, and that the election of Abe has stirred up a lot of painful emotions,” says Susan J. Napier, professor of Japanese studies at Tufts University in Massachusetts and author of a forthcoming book on Miyazaki. “A lot of Japanese are mainly concerned about the economy, and Abe at least gives the impression of finally trying to make some radical changes. I think people are both hopeful and scared to hope.”

Anime, and its print cousin and forebear, manga, are primarily products of postwar Japan. The medium’s first superhero, “Astro Boy,” was created partly out of artist Osamu Tezuka’s desire to see nuclear technology used for peaceful purposes after the devastation of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Its first giant robot, “Tetsujin 28-go” (“Gigantor” in the West), was often depicted in original versions stomping through the New York City skyline. “Battleship Yamato,” one of the original series broadcast on American television, reimagined Japan’s sunken naval vessel as a retrofitted high-tech spaceship.

Ironically, “The Wind Rises” examines the complex and self-contradictory life of the engineer who created one of Japan’s most fearsome weapons — reflecting Miyazaki’s own contradictions. His father worked at Miyazaki Airplane, which made parts for Zero fighter planes, and Miyazaki has long been enamored of the mechanics of flight and aircraft.

At the film’s premiere screening at the New York Film Festival two weeks ago, I was struck by the story’s sustaining narrative tension. Every moment of Jiro’s dreamlike bliss about beauty is bombed to Earth with a brutal thud. Images of flight and transcendence, the artist’s reveries, are followed by scenes of wreckage and death, the artist’s nightmare. Jiro remains a cipher throughout — so devoted to his visions of possibility that he can’t see the horror burning at the periphery. At the moment of his greatest achievement, he loses the love of his life.

Author and translator Frederik L. Schodt, who has translated Miyazaki’s interviews and essays, believes that Miyazaki’s role is critical in uniting Japanese generations amid the country’s current identity crisis.

“At his age," Schodt says, "and with his status among youth, (Miyazaki) can be an important bridge between younger generations, whose historical knowledge of World War II is limited, and an older, fading generation, for whom it remains a searing and real memory."

“Kaze Tachinu” (“The Wind Rises”) is now showing in cinemas nationwide. Roland Kelts is the author of “Japanamerica: How Japanese Pop Culture has Invaded the U.S.” He is a visiting scholar at Keio University in Tokyo.

Published on October 08, 2013 14:11

October 3, 2013

Meet 281_Anti Nuke, Japan's street artist of dissent, for The New Yorker

The stickers went up a few months after Japan’s triple disaster in 2011—an earthquake and tsunami that took twenty thousand lives, and an ongoing nuclear crisis that threatens more. They first appeared along the shabby backstreets of Shibuya, in downtown Tokyo, a place that offers some of the very few canvasses for graffiti in a city not given to celebrating street art. The British expat photographer and filmmaker Adrian Storey couldn’t ignore them. “Being a foreigner, there was a sort of brief period after 3/11 when there was this sense of community in Tokyo that I haven’t felt before,” Storey says. “Then it kind of went away, and people just went back to shopping. I was drawn to the stickers because I realized it was a Japanese person behind them, and they actually cared about what was happening. I started photographing every sticker I found.”

The stickers went up a few months after Japan’s triple disaster in 2011—an earthquake and tsunami that took twenty thousand lives, and an ongoing nuclear crisis that threatens more. They first appeared along the shabby backstreets of Shibuya, in downtown Tokyo, a place that offers some of the very few canvasses for graffiti in a city not given to celebrating street art. The British expat photographer and filmmaker Adrian Storey couldn’t ignore them. “Being a foreigner, there was a sort of brief period after 3/11 when there was this sense of community in Tokyo that I haven’t felt before,” Storey says. “Then it kind of went away, and people just went back to shopping. I was drawn to the stickers because I realized it was a Japanese person behind them, and they actually cared about what was happening. I started photographing every sticker I found.”Some stickers are small, eight inches or so in height. Others are the size of a stunted adult or a large child. In fact, children are featured in many of them, especially the motif of a young girl in a raincoat above the caption “I hate rain,” with the trefoil symbol for radiation stamped between “hate” and “rain.” On other stickers, silhouettes of the bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki are suspended in white space beside the logo for the Tokyo Electric Power Company, the government-allied conglomerate responsible for the operation and maintenance of the severely damaged Fukushima nuclear power plants. Sometimes the stark black lines and blotches resemble Rorschach tests. You look and see nothing, then look again and see Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s face, his mouth suffocated by an American flag.

The artist behind them calls himself 281_Anti Nuke, and he has become a cult phenomenon among Tokyo locals. The numerals refer to an athletic jersey he wore in high school. “It’s just nostalgia,” he says. “Memories of my happier times.” Tagged as the “Japanese Banksy,” he is an unlikely manifestation of Japan’s shredded identity: a contemporary artist of dissent in a country that rarely tolerates protest and barely supports modern art. His real name is Kenta Matsuyama, though few Japanese know that, since it appears only in the fine print on his manager’s English-language Web site. He is a fortysomething father born and raised near Fukushima, the site of Japan’s most pressing nuclear disaster. We meet in the heart of Shibuya, in a second-story café overlooking the most famous intersection in Japan—a crowded network of diagonal crosswalks that is featured in nearly every film set in Tokyo.

We are hiding in plain sight. “These people,” he says, gesturing toward the window and the masses below, “they only vote for the winner; they only think about the winner. They have no concept of real strength. They feel satisfied just knowing that the party they voted for won.” (That party, the archconservative, U.S.-friendly, and pro-nuclear Liberal Democratic Party, crows about a mandate after sweeping recent elections.) He is wearing a tight-fitting gray hoodie, pitch-black jeans and sunglasses, and a white surgical mask. It’s not always easy to hear him through the mask, so he tugs it down a bit when his speech quickens in anger. “Maybe it’s true that there’s no political party you can count on, but it’s more than that. It’s fear. It’s Japanese people never doubting their leaders. Looking out at Shibuya, I’m sure that nobody out there remembers the idea of radiation anymore. People abroad know more about the crisis in Fukushima than the Japanese. The Japanese are trying to forget. I want to make them remember.”

Anti Nuke is an active Twitter user, but when he first started posting his art, he received death threats so virulent that last year he temporarily took down his Twitter and Facebook accounts and started hiding all of his personal information. Even now, his Web site is often hacked. In public, when he is not cloaked by hoodie, sunglasses, and mask, he wears a full-body hazmat suit. As for his method: “Stickers are better than graffiti,” he says, “because they are faster to apply. You just stick them on and run off. And I use very simple English to be direct, without nuances. Like, ‘I hate rain.’ In Japanese, it’s ‘Watashi wa ame ga kirai.’ So in Japanese, you really need to talk about who hates rain, and why, and in what context. But in English it’s more iconic. There’s more room for the imagination, and that’s powerful.”

Anti Nuke is an active Twitter user, but when he first started posting his art, he received death threats so virulent that last year he temporarily took down his Twitter and Facebook accounts and started hiding all of his personal information. Even now, his Web site is often hacked. In public, when he is not cloaked by hoodie, sunglasses, and mask, he wears a full-body hazmat suit. As for his method: “Stickers are better than graffiti,” he says, “because they are faster to apply. You just stick them on and run off. And I use very simple English to be direct, without nuances. Like, ‘I hate rain.’ In Japanese, it’s ‘Watashi wa ame ga kirai.’ So in Japanese, you really need to talk about who hates rain, and why, and in what context. But in English it’s more iconic. There’s more room for the imagination, and that’s powerful.”281_Anti Nuke’s work is about to reach more people via exhibitions in the New York and Los Angeles, and a documentary film about his art directed by Storey will début in festivals next year. “His mission is personal,” says Storey. “He wants people to think about the same things he’s thinking about, but, like he said to me many times, it’s about the future of his children. It’s the future of everybody’s children in Japan. He doesn’t want to make a name for himself.”

Perhaps. But donning hoodies, shades, and surgical masks, not to mention the occasional hazmat suit, is an odd strategy for anonymity. “It’s fine if I become famous if it helps communicate this huge problem,” Anti Nuke concedes. “There are bigger problems in Fukushima than we know now. I’m sure of that. I’ve communicated with people there. I have family there. The Japanese government will not save them, and since the survivors cannot escape, Fukushima people hate Tokyo people for the electricity they use and cannot conserve.”

He insists that he is not anti-American, just pro-truth. “I love the American people, but I want them to help save Japan. This time, it’s the Japanese people who are to blame. We’re not aware, and we are actively trying to forget. We need foreigners to save us from ourselves.”

Roland Kelts is the author of “

Art by 281_Anti Nuke, courtesy of Roth Management. Photograph by Bellamy Hunt, courtesy of Roth Management.

More @ The New Yorker

Published on October 03, 2013 08:24

September 26, 2013

Hello, Toronto!

York University, 9-9-2013

The Japanese Canadian Cultural Centre, 9-10-2013

The Japan Foundation, 9-11-2013

Hockley Valley, Ontario, 9-12-2013

Published on September 26, 2013 19:12

September 19, 2013

On South Africa and safari: travel column for Paper Sky magazine

Published on September 19, 2013 16:22