Roland Kelts's Blog, page 42

January 20, 2014

Hollywood invests in anime and Asian Pop Culture, for Nikkei Asian Review

Big investment means silver lining for Asian pop culture abroadROLAND KELTS, Contributing writer

NEW YORK -- 2013 went out with a bang for fans and creators of Asian pop culture, and the reverberations are being felt on both sides of the Pacific.

In December, the deep-pocketed Chernin Group, founded by veteran Hollywood mogul Peter Chernin, announced it had taken a majority stake in San Francisco-based Crunchyroll, the world’s leading anime and Asian pop culture streaming website.

Peter Chernin

Peter Chernin

Crunchyroll offers free and paid content from Japan and South Korea, including TV dramas, anime series and digital manga, alongside subscriber-only interactive features such as chat rooms, forums and daily discounts on pop-related merchandise.

With an investment estimated at just under $100 million, Chernin Group placed a meaty bet on what its president, Jesse Jacobs, calls "the future of television."

"The global demographic of Asian pop culture fans is young, early tech adopters who are super-passionate consumers of media," said Jacobs. "We’re huge fans of what (Crunchyroll is) doing."

Chernin Group seems keen to diversify the content, such as offering Chinese or Indian entertainment, for example. However, Crunchyroll co-founder and CEO Kun Gao insists that the central mission is to "bring the best of Japan to the world."

That is music to the ears of industry professionals in both the U.S. and Japan. Marc Perez, CEO of the California-based Society for the Promotion of Japanese Animation, said, "Chernin’s recent investment in Crunchyroll brings fresh attention to the industry, and everyone from content creators to distributors to anime conventions and consumers will benefit."

Peter Chernin is the former president and Chief Operating Officer of Rupert Murdoch’s News Corp. For 13 years he oversaw the rapid global expansion of Fox Television and the blockbuster successes of movie studio Twentieth Century Fox, with international megahits like "Titanic" and "Avatar."

Chernin resigned to pursue the world of startups in 2009 -- the very same year Crunchyroll transformed itself from piracy to legitimacy by legally licensing anime content.

Chernin Group has made a name for itself by investing in high-octane startups like Tumblr, Pandora and Flipboard. Last spring, it tried, unsuccessfully, to acquire U.S. streaming TV site Hulu.

"The Crunchyroll founders and senior management team have accomplished two incredible things," Chernin said in a Dec. 2 statement announcing the deal. “One, they have built one of the leading online video companies in the industry. And two, they have created the best and largest community for anime video in the world.

"We couldn't be more excited about the future,” he added. “Our plan is to continue to grow the anime vertical as well as launch new channels in different genres. Online video is growing faster than any other sector in media, and we feel that with Crunchyroll, we have a fantastic anchor platform."

Overcoming the odds

That platform was hard to build. Almost exactly five years ago, on New Year’s Day, Crunchyroll transformed itself from the most popular site for free anime downloads to a portal for legally licensed content -- literally overnight. Many felt the odds were insurmountable: Why would anyone pay for content that was free the night before?

At the time, Vu Nguyen, the site’s co-founder and vice president of business development and strategy, said: "The fans genuinely want to support creators and the industry. They just haven’t been educated on how the industry works. We’re doing our best to inform them."

Crunchyroll shrewdly opened an office in Tokyo and began negotiating with Japanese studios and television networks. A partnership with TV Tokyo, still the site’s core ally and now joined by Chernin Group, opened the floodgates to licenses for mass-appeal anime titles like "One Piece," “Naruto,” and the latest global hit, “Attack on Titan.”

Kun Gao

Kun Gao

A key element of Crunchyroll’s success has been community. It has created a space on the Internet where like-minded fans of Asian pop culture can communicate, exchange information and feel like they belong. The site features message boards, special deals and communal forums and chats that bring its users together in a common pursuit. While megasites like Netflix and Hulu feature some anime content, they are comparatively aimless vessels next to Crunchyroll’s sharply focused armada.

"Our thesis has been that we think that we can build a superior service if we super-serve our audience," said Crunchyroll’s Gao. "Start from content and deliver 100% of what they want, nothing more or less. Add to that community, e-commerce, extensions of the shows they’re watching, and then manga."

"We’re trying to build this over-the-top experience over this (very specific) content, and we’re able to do a better job than anyone else. Our hypothesis is that there are customers who love this so much they’re willing to subscribe. And that’s been proven true."

Three years into its current incarnation, Crunchyroll began accruing profit -- a solid track record for a startup -- and the licensing became easier in Japan as domestic anime producers started to trust the online model.

Power of community

Chernin Group’s Jacobs agrees that the community-focused approach is a cornerstone of the site’s appeal and potential.

"We spent time doing our due diligence," he said. "We went into the message boards and the forums, and they’re just amazing. You’ve got people posting profiles of themselves -- male, female, young and old. And they’re all super passionate. That’s what we like. Crunchyroll hadn’t spent a dime on marketing, and they’ve got this many subscribers and this much attention.”

Low overhead has been another hallmark of Crunchyroll’s unlikely success. The fledgling startup raised $5.5 million in 2007-2008 to prepare for its transition to legitimacy. It never looked back, keeping expenses to a minimum to serve a hungry and willing fanbase.

"We’re very nuts and bolts kind of guys," said Gao. "We try to be really frugal so we can pass on any savings to our users. We want only what we need to get the job done. Our partnerships in Japan are not something money can buy. You have to build trust and slowly build upwards. We’ve always asked ourselves if we could do more if we had more capital, and the answer was always no.”

Jacobs is happy with what the company has done: “These guys deserve a ton of credit," he said. "We look at a lot of early stage growth equity VC-backed startups, and these guys did an amazing thing. They raised money seven years ago and never did it again, which is unheard of in the world of startups. They built a business. There’s real value to the culture and brand they built."

Now, of course, the pressure is on for Crunchyroll to deliver a wider array of content to their global audience. Plans are well underway to expand the service globally. The site already hosts a mix of South Korean and Japanese live-action dramas alongside its anime and manga mainstays.

Yuji Nunokawa, founder of Studio Pierrot (“Naruto,” “Bleach”) and president of the Association of Japanese Animations, is hopeful about the future.

"Crunchyroll was a forerunner in the legal streaming business and gave the anime industry a silver lining when it was devastated by illegal streaming,” said Nunokawa. "It would be great if this investment helps Crunchyroll grow bigger and gives us an even brighter silver lining in the new year."

Roland Kelts writes for The New Yorker, Time, CNN, Newsweek Japan and other publications, and is a frequent contributor to NPR and the BBC. He is the author of "Japanamerica: How Japanese Pop Culture has Invaded the U.S.," and a visiting scholar at Tokyo's Keio University.

NEW YORK -- 2013 went out with a bang for fans and creators of Asian pop culture, and the reverberations are being felt on both sides of the Pacific.

In December, the deep-pocketed Chernin Group, founded by veteran Hollywood mogul Peter Chernin, announced it had taken a majority stake in San Francisco-based Crunchyroll, the world’s leading anime and Asian pop culture streaming website.

Peter Chernin

Peter CherninCrunchyroll offers free and paid content from Japan and South Korea, including TV dramas, anime series and digital manga, alongside subscriber-only interactive features such as chat rooms, forums and daily discounts on pop-related merchandise.

With an investment estimated at just under $100 million, Chernin Group placed a meaty bet on what its president, Jesse Jacobs, calls "the future of television."

"The global demographic of Asian pop culture fans is young, early tech adopters who are super-passionate consumers of media," said Jacobs. "We’re huge fans of what (Crunchyroll is) doing."

Chernin Group seems keen to diversify the content, such as offering Chinese or Indian entertainment, for example. However, Crunchyroll co-founder and CEO Kun Gao insists that the central mission is to "bring the best of Japan to the world."

That is music to the ears of industry professionals in both the U.S. and Japan. Marc Perez, CEO of the California-based Society for the Promotion of Japanese Animation, said, "Chernin’s recent investment in Crunchyroll brings fresh attention to the industry, and everyone from content creators to distributors to anime conventions and consumers will benefit."

Peter Chernin is the former president and Chief Operating Officer of Rupert Murdoch’s News Corp. For 13 years he oversaw the rapid global expansion of Fox Television and the blockbuster successes of movie studio Twentieth Century Fox, with international megahits like "Titanic" and "Avatar."

Chernin resigned to pursue the world of startups in 2009 -- the very same year Crunchyroll transformed itself from piracy to legitimacy by legally licensing anime content.

Chernin Group has made a name for itself by investing in high-octane startups like Tumblr, Pandora and Flipboard. Last spring, it tried, unsuccessfully, to acquire U.S. streaming TV site Hulu.

"The Crunchyroll founders and senior management team have accomplished two incredible things," Chernin said in a Dec. 2 statement announcing the deal. “One, they have built one of the leading online video companies in the industry. And two, they have created the best and largest community for anime video in the world.

"We couldn't be more excited about the future,” he added. “Our plan is to continue to grow the anime vertical as well as launch new channels in different genres. Online video is growing faster than any other sector in media, and we feel that with Crunchyroll, we have a fantastic anchor platform."

Overcoming the odds

That platform was hard to build. Almost exactly five years ago, on New Year’s Day, Crunchyroll transformed itself from the most popular site for free anime downloads to a portal for legally licensed content -- literally overnight. Many felt the odds were insurmountable: Why would anyone pay for content that was free the night before?

At the time, Vu Nguyen, the site’s co-founder and vice president of business development and strategy, said: "The fans genuinely want to support creators and the industry. They just haven’t been educated on how the industry works. We’re doing our best to inform them."

Crunchyroll shrewdly opened an office in Tokyo and began negotiating with Japanese studios and television networks. A partnership with TV Tokyo, still the site’s core ally and now joined by Chernin Group, opened the floodgates to licenses for mass-appeal anime titles like "One Piece," “Naruto,” and the latest global hit, “Attack on Titan.”

Kun Gao

Kun GaoA key element of Crunchyroll’s success has been community. It has created a space on the Internet where like-minded fans of Asian pop culture can communicate, exchange information and feel like they belong. The site features message boards, special deals and communal forums and chats that bring its users together in a common pursuit. While megasites like Netflix and Hulu feature some anime content, they are comparatively aimless vessels next to Crunchyroll’s sharply focused armada.

"Our thesis has been that we think that we can build a superior service if we super-serve our audience," said Crunchyroll’s Gao. "Start from content and deliver 100% of what they want, nothing more or less. Add to that community, e-commerce, extensions of the shows they’re watching, and then manga."

"We’re trying to build this over-the-top experience over this (very specific) content, and we’re able to do a better job than anyone else. Our hypothesis is that there are customers who love this so much they’re willing to subscribe. And that’s been proven true."

Three years into its current incarnation, Crunchyroll began accruing profit -- a solid track record for a startup -- and the licensing became easier in Japan as domestic anime producers started to trust the online model.

Power of community

Chernin Group’s Jacobs agrees that the community-focused approach is a cornerstone of the site’s appeal and potential.

"We spent time doing our due diligence," he said. "We went into the message boards and the forums, and they’re just amazing. You’ve got people posting profiles of themselves -- male, female, young and old. And they’re all super passionate. That’s what we like. Crunchyroll hadn’t spent a dime on marketing, and they’ve got this many subscribers and this much attention.”

Low overhead has been another hallmark of Crunchyroll’s unlikely success. The fledgling startup raised $5.5 million in 2007-2008 to prepare for its transition to legitimacy. It never looked back, keeping expenses to a minimum to serve a hungry and willing fanbase.

"We’re very nuts and bolts kind of guys," said Gao. "We try to be really frugal so we can pass on any savings to our users. We want only what we need to get the job done. Our partnerships in Japan are not something money can buy. You have to build trust and slowly build upwards. We’ve always asked ourselves if we could do more if we had more capital, and the answer was always no.”

Jacobs is happy with what the company has done: “These guys deserve a ton of credit," he said. "We look at a lot of early stage growth equity VC-backed startups, and these guys did an amazing thing. They raised money seven years ago and never did it again, which is unheard of in the world of startups. They built a business. There’s real value to the culture and brand they built."

Now, of course, the pressure is on for Crunchyroll to deliver a wider array of content to their global audience. Plans are well underway to expand the service globally. The site already hosts a mix of South Korean and Japanese live-action dramas alongside its anime and manga mainstays.

Yuji Nunokawa, founder of Studio Pierrot (“Naruto,” “Bleach”) and president of the Association of Japanese Animations, is hopeful about the future.

"Crunchyroll was a forerunner in the legal streaming business and gave the anime industry a silver lining when it was devastated by illegal streaming,” said Nunokawa. "It would be great if this investment helps Crunchyroll grow bigger and gives us an even brighter silver lining in the new year."

Roland Kelts writes for The New Yorker, Time, CNN, Newsweek Japan and other publications, and is a frequent contributor to NPR and the BBC. He is the author of "Japanamerica: How Japanese Pop Culture has Invaded the U.S.," and a visiting scholar at Tokyo's Keio University.

Published on January 20, 2014 05:30

January 17, 2014

Sushi breather

Published on January 17, 2014 02:19

January 14, 2014

What to sell; what to eat? On food from Fukushima for SmartPlanet / CBS

Scientists say Fukushima's food is safe. So why aren't the Japanese eating it?Since the nuclear meltdown, the region’s seafood and agriculture industries have suffered -- largely because of mistrust of the government.By Roland Kelts

TOKYO -- After Fukushima suffered the world’s worst nuclear meltdown since Chernobyl nearly three years ago, Japanese government officials say the region's food is safe to eat. Problem is, neither its producers nor consumers trust them anymore.

Irradiated "ton packs" roadside in Date. [photo by Nathalie-Kyoko Stucky]

Irradiated "ton packs" roadside in Date. [photo by Nathalie-Kyoko Stucky]

While not quite the proverbial breadbasket of Japan, Fukushima was, for a long time, home to the nation’s fourth-largest farming area and has long supported itself through the production of rice, fruits, vegetables, tobacco and silk, in addition to a hefty supply of fish and seafood fetched from its 100-mile coastline.

Since the meltdown, Fukushima has dropped from the nation’s fourth-largest rice producer to its seventh, with production reportedly slipping 17 percent, according to the agriculture ministry. Roughly 100,000 farmers have lost an estimated 105 billion yen ($1 billion). Livestock farming once thrived in Fukushima – until most of its farmers were forced to evacuate after the meltdown, and 5,000 cattle were ordered slaughtered. The rest were left to starve to death.

“We won’t eat it ourselves, but you tell us to sell it to others. Do you know how guilty this makes us feel? There is no pride or joy in our work anymore.”

Despite the gut instinct that food from Fukushima cannot be safe, prominent scientists back up the government, with some noting that early evacuations, land-restriction and decontamination efforts, together with Japan’s natural iodine-rich seafood diet, make Fukushima’s food today safer than an average CT scan.

The real culprit of Fukushima’s agricultural industry’s woes may be what most Japanese consider egregious government lies and obfuscation (most notably, waiting two months before even conceding the word ‘meltdown’), tight-lipped secrecy around its data and laughably low-tech decontamination strategies that don’t seem like a match for nuclear contamination. And compounding the problem is that some scientists agree the data isn’t good.

Nancy Foust, a U.S.-based researcher and technology and communications specialist with SimplyInfo.org, a multi-disciplinary U.S.-based research group monitoring the Fukushima decontamination efforts, says, “We have found efforts to decontaminate rice paddies, but hard data on things like before-and-after crops have been hard to come by. The decontamination techniques so far have involved either deep tilling to shove the top soil down deep, or mixing in potassium to try to prevent the plants from taking up cesium.”

And that’s the rub: Most of the techniques employed in Japan – ranging from soil scraping (skimming of the first three centimeters of soil and storing it in massive canvas bags called “ton packs”), to tilling, to power blasting the bark off fruit trees or water sweeping with Karchers (high-pressure, industrial strength cleaning machines) – are primitive at best, near-replicas of strategies used in Chernobyl nearly 28 years ago. Worse, the results of such efforts are often kept secret, or at least oblique, by the government officials overseeing them.

“All of our requests for disclosure have been rejected,” says Nobuyoshi Ito, a rice farmer in Iidate and former systems engineer who has emerged as a widely cited grassroots expert on decontamination. He has been conducting his own tests with Geiger counters and other equipment to compare results with government figures, sending them to a laboratory in Shizuoka prefecture for confirmation. (A technician at the lab said he was actually better informed than most Japanese government officials on the subject of contamination.) “Even the Ministry of the Environment, the ones who actually lead the decontamination work, are unclear, or at a loss to specifically quantify their assessments. When we ask them about the possible reduction of the rate of radiation, they answer, ‘We won't know until we try.’” According to Ito, the government keeps kicking the can down the road, refusing to publicly release its findings, claiming that they are still in progress.

Ton packs, Hirono. [Nathalie-Kyoko Stucky]

Ton packs, Hirono. [Nathalie-Kyoko Stucky]

If rice and produce are hard to assess, fish and seafood pose an even bigger challenge. Marine creatures are always on the move, following tides and currents. “Some fish in one area of the sea are contaminated, others aren't,” says Foust. “They're having better luck focusing on certain breeds of bottom feeders. The rock fish, for example, almost always show some level of contamination, though it’s usually low. They’re reliable, but they don’t show the extremes.”

The government botched this test as well, said Foust, displaying samples like octopi, which typically has low levels, to claim all seafood was safe. While natural iodine from some seafood helps cancel out the radioactive iodine in fast-moving fish, using octopi as a standard misrepresents localized risk. No one was fooled, further eroding trust.

So the fear of Fukushima's food persists. Geraldine Thomas, Professor of Molecular Pathology at the Imperial College in London, and the scientific director of the Chernobyl Tissue bank, was asked to assess likely health effects from Fukushima after her extensive work on thyroid cancer cases in Russia. Thomas finds the food fear in Japan baffling – a sign of modern and misbegotten hysteria.

“The most important thing to do immediately after the accident was to restrict the consumption of locally produced milk and green leafy vegetables, which are known to concentrate [radioactive] iodine,” she says, as opposed to the healthy, natural iodine found in some seafood. “This the Japanese government did very well – in contrast to the Soviet authorities following the Chernobyl accident. The Japanese continue to monitor foodstuffs, and [they] have imposed even stricter limits on radiation in foodstuffs from Fukushima prefecture than we have for our own produce in the U.K. and the U.S.”

Dr. Ian Fairlie, an independent consultant on radioactivity in the environment who is closely monitoring Fukushima says that Japanese should fear radiation – just not necessarily in the region’s food. “Contaminated food intakes are a relatively small part of the problem. People near Fukushima are more exposed via direct radiation (groundshine): smaller doses also come from water intakes, and from inhalation.”

Adds Professor Thomas: “Both the World Health Organization and the United Nations Scientific Committee on the Effects of Atomic Radiation agree that the biggest threat to health post Fukushima is the fear of radiation, not the radiation itself. Personally I would have no worries about consuming food from Fukushima – and in fact did so when I was in Tokyo last April.”

~Roland Kelts contributes to The New Yorker, Time, CNN, The Nikkei Asia Review, NPR and the BBC, among others. He is the author of

TOKYO -- After Fukushima suffered the world’s worst nuclear meltdown since Chernobyl nearly three years ago, Japanese government officials say the region's food is safe to eat. Problem is, neither its producers nor consumers trust them anymore.

Irradiated "ton packs" roadside in Date. [photo by Nathalie-Kyoko Stucky]

Irradiated "ton packs" roadside in Date. [photo by Nathalie-Kyoko Stucky]While not quite the proverbial breadbasket of Japan, Fukushima was, for a long time, home to the nation’s fourth-largest farming area and has long supported itself through the production of rice, fruits, vegetables, tobacco and silk, in addition to a hefty supply of fish and seafood fetched from its 100-mile coastline.

Since the meltdown, Fukushima has dropped from the nation’s fourth-largest rice producer to its seventh, with production reportedly slipping 17 percent, according to the agriculture ministry. Roughly 100,000 farmers have lost an estimated 105 billion yen ($1 billion). Livestock farming once thrived in Fukushima – until most of its farmers were forced to evacuate after the meltdown, and 5,000 cattle were ordered slaughtered. The rest were left to starve to death.

~“We won’t eat it ourselves, but you tell us to sell it to others. Do you know how guilty this makes us feel? There is no pride or joy in our work anymore.”~At a testy meeting last fall between government representatives and farmers from Sukagawa and Soma, two of Fukushima’s largest food-producing areas, one Sukagawa farmer noted that the government approves of shipments of food that test below 100 becquerels (units of radioactivity) per kilogram, lower than its original 500 Bq limit (and in line with global standards), selling it at below-market value. But he would not allow his own family to eat the food he is allowed to sell.

“We won’t eat it ourselves, but you tell us to sell it to others. Do you know how guilty this makes us feel? There is no pride or joy in our work anymore.”

Despite the gut instinct that food from Fukushima cannot be safe, prominent scientists back up the government, with some noting that early evacuations, land-restriction and decontamination efforts, together with Japan’s natural iodine-rich seafood diet, make Fukushima’s food today safer than an average CT scan.

The real culprit of Fukushima’s agricultural industry’s woes may be what most Japanese consider egregious government lies and obfuscation (most notably, waiting two months before even conceding the word ‘meltdown’), tight-lipped secrecy around its data and laughably low-tech decontamination strategies that don’t seem like a match for nuclear contamination. And compounding the problem is that some scientists agree the data isn’t good.

Nancy Foust, a U.S.-based researcher and technology and communications specialist with SimplyInfo.org, a multi-disciplinary U.S.-based research group monitoring the Fukushima decontamination efforts, says, “We have found efforts to decontaminate rice paddies, but hard data on things like before-and-after crops have been hard to come by. The decontamination techniques so far have involved either deep tilling to shove the top soil down deep, or mixing in potassium to try to prevent the plants from taking up cesium.”

And that’s the rub: Most of the techniques employed in Japan – ranging from soil scraping (skimming of the first three centimeters of soil and storing it in massive canvas bags called “ton packs”), to tilling, to power blasting the bark off fruit trees or water sweeping with Karchers (high-pressure, industrial strength cleaning machines) – are primitive at best, near-replicas of strategies used in Chernobyl nearly 28 years ago. Worse, the results of such efforts are often kept secret, or at least oblique, by the government officials overseeing them.

“All of our requests for disclosure have been rejected,” says Nobuyoshi Ito, a rice farmer in Iidate and former systems engineer who has emerged as a widely cited grassroots expert on decontamination. He has been conducting his own tests with Geiger counters and other equipment to compare results with government figures, sending them to a laboratory in Shizuoka prefecture for confirmation. (A technician at the lab said he was actually better informed than most Japanese government officials on the subject of contamination.) “Even the Ministry of the Environment, the ones who actually lead the decontamination work, are unclear, or at a loss to specifically quantify their assessments. When we ask them about the possible reduction of the rate of radiation, they answer, ‘We won't know until we try.’” According to Ito, the government keeps kicking the can down the road, refusing to publicly release its findings, claiming that they are still in progress.

Ton packs, Hirono. [Nathalie-Kyoko Stucky]

Ton packs, Hirono. [Nathalie-Kyoko Stucky]If rice and produce are hard to assess, fish and seafood pose an even bigger challenge. Marine creatures are always on the move, following tides and currents. “Some fish in one area of the sea are contaminated, others aren't,” says Foust. “They're having better luck focusing on certain breeds of bottom feeders. The rock fish, for example, almost always show some level of contamination, though it’s usually low. They’re reliable, but they don’t show the extremes.”

The government botched this test as well, said Foust, displaying samples like octopi, which typically has low levels, to claim all seafood was safe. While natural iodine from some seafood helps cancel out the radioactive iodine in fast-moving fish, using octopi as a standard misrepresents localized risk. No one was fooled, further eroding trust.

So the fear of Fukushima's food persists. Geraldine Thomas, Professor of Molecular Pathology at the Imperial College in London, and the scientific director of the Chernobyl Tissue bank, was asked to assess likely health effects from Fukushima after her extensive work on thyroid cancer cases in Russia. Thomas finds the food fear in Japan baffling – a sign of modern and misbegotten hysteria.

“The most important thing to do immediately after the accident was to restrict the consumption of locally produced milk and green leafy vegetables, which are known to concentrate [radioactive] iodine,” she says, as opposed to the healthy, natural iodine found in some seafood. “This the Japanese government did very well – in contrast to the Soviet authorities following the Chernobyl accident. The Japanese continue to monitor foodstuffs, and [they] have imposed even stricter limits on radiation in foodstuffs from Fukushima prefecture than we have for our own produce in the U.K. and the U.S.”

Dr. Ian Fairlie, an independent consultant on radioactivity in the environment who is closely monitoring Fukushima says that Japanese should fear radiation – just not necessarily in the region’s food. “Contaminated food intakes are a relatively small part of the problem. People near Fukushima are more exposed via direct radiation (groundshine): smaller doses also come from water intakes, and from inhalation.”

Adds Professor Thomas: “Both the World Health Organization and the United Nations Scientific Committee on the Effects of Atomic Radiation agree that the biggest threat to health post Fukushima is the fear of radiation, not the radiation itself. Personally I would have no worries about consuming food from Fukushima – and in fact did so when I was in Tokyo last April.”

~Roland Kelts contributes to The New Yorker, Time, CNN, The Nikkei Asia Review, NPR and the BBC, among others. He is the author of

Published on January 14, 2014 06:15

January 10, 2014

The year ahead in anime, manga and Japanese pop culture for The Japan Times

CULTURE | CULTURE SMASH

Anime/manga experts hopeful for year ahead

BY ROLAND KELTS

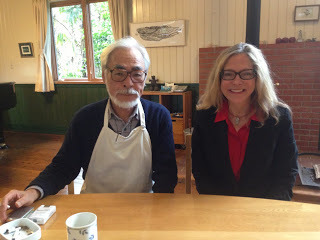

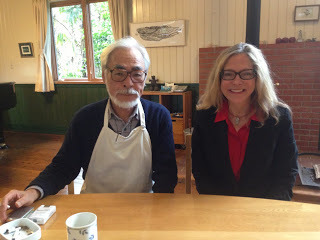

Aside from Hayao Miyazaki’s sudden departure from filmmaking in September, the anime world saw some potentially hopeful developments in 2013.

Hayao Miyazaki and Susan J. Napier at Studio Ghibli, Tokyo, January, 2014.

Hayao Miyazaki and Susan J. Napier at Studio Ghibli, Tokyo, January, 2014.

As I reported here, the government’s multibillion-yen Cool Japan Fund was launched last summer, after years of empty promises. Following the lead of Crunchyroll, the profitable San Francisco-based online anime and manga portal, domestic startups such as Daisuki began streaming anime series globally. Crunchyroll itself opened a digital manga site — and got a Christmas-time jolt of Hollywood cash from big-ticket investor The Chernin Group. A bold new apocalyptic anime series, “Shingeki no Kyojin (Attack on Titan),” earned raves and fans, as did the virtual reality adventure, "Sword Art Online," and the jazz-inflected new show “Kids on the Slope,” from veteran Shinichiro Watanabe (“Cowboy Bebop,” “Samurai Champloo”).

“In the United States, perhaps the worst (for anime) is in the rearview mirror now,” says author and translator Frederik L. Schodt.

“The market is probably half of what it was in 2007,” he admits, “but the fan base still seems dedicated and even growing. Rather than going to conventions to watch films and buy merchandise, which the Internet has rendered unnecessary, the conventions in the U.S. seem to be evolving into something different. They are more of a place to socialize, wear costumes and consort with like-minded fans. In a way, they may be becoming more decoupled from Japan, more autonomous, and even more uniquely American.”

"Sword Art Online," courtesy of Crunchyroll.com

"Sword Art Online," courtesy of Crunchyroll.com

The robust anime-convention industry is especially notable amid ongoing economic malaise. Both Anime Expo and Otakon, the U.S. West and East coasts’ largest conventions, respectively, reported sky-high tallies, with the latter opening its first satellite convention in Las Vegas at the start of this month. As Schodt notes, unlike the Tokyo International Anime Fair (TAF), which is more of a trade show to unveil industry offerings and announcements, conventions in the U.S. serve a communal, celebratory function. The fans come first.

Speaking of TAF, this year’s event, now renamed Anime Japan, will bring together the entire industry for the first time since 2011. That was when producers and publishers opposed to then Tokyo Gov. Shintaro Ishihara’s Bill 156, outlawing so-called “harmful” anime and manga, abandoned TAF (which Ishihara chaired) and created their own show, The Anime Contents Expo. While both were canceled in the wake of disaster in March 2011, they have since been held at similar times but separate locations — creating logistical headaches for attendees from Japan and overseas. The two will reunite this March, now that Ishihara is out of the picture.

Alas, his legislation isn’t. For criminal and commercial reasons, Tokyo-based translator and manga author Dan Kanemitsu sees dark days ahead. “My prediction is that the ruling Liberal Democratic Party will argue that the police can be trusted with more powers (to enforce Ishihara’s manga law),” he says, citing the increasingly conservative bent of the current administration and hysteria over the 2020 Olympics. “There will be a lot of noise from the opposition, but there won’t be as much heated protest as with the state secrets bill that just passed.”

Kanemitsu is also concerned about coming changes in Japanese copyright legislation that may accompany passage of the Trans-Pacific Partnership trade pact, for which the U.S. is pressing Prime Minister Shinzo Abe hard. “The TPP’s restrictive copyright regime is thought to be detrimental to Japan’s dōjin-shi (fan art) and online parody communities, since parody and fair use are not protected under Japanese copyright laws, and the chances that these provisions will be given protection is rather slim.

“If the TPP is passed per America’s demands, the police will no longer need permission from holders of copyright to go after violators. Any charge by a third party that a copyright violation is in progress will be enough for the police to arrest someone.”

He adds that criminal and commercial pressures combined will force some manga publishers to shutter this year, and that several artists have already told him they are thinking of quitting.

Coincidentally, after Miyazaki quit anime, he moved on to manga, and is reportedly drawing a series about samurai. “Studio Ghibli is the big story of 2014,” says professor and author Susan J. Napier, who is writing a book on Miyazaki. “The staff remain superb, and there is a rumor that ‘Evangelion’ director Hideaki Anno might film a sequel to Miyazaki’s early masterpiece, ‘Nausicaä.’ I’d pay double to see that combination realized!”

Animation critic and author Charles Solomon notes that U.S fans are looking forward to the imminent release of Anno’s “Evangelion: 3.0 You Can (Not) Redo,” and wonders if Miyazaki’s latest, “Kaze Tachinu (The Wind Rises),” will receive an Oscar nod next month, owing to its subject matter. “Will American viewers accept a film about the designer of the Zero fighter — especially the older members of the Academy, who may remember World War II?”

Viz Media President and CEO, Ken Sasaki

Viz Media President and CEO, Ken Sasaki

For the broader U.S. fan base, “Naruto,” “Bleach” and “One Piece” remain top sellers — but they were joined last year by the grisly “Attack on Titan,” about flesh-eating giants. In real-time video rankings on Crunchyroll, which streams the show worldwide, “Attack” periodically knocked “Naruto” out of the top perch, where it has been for five consecutive years, according to the site’s Japan general manager, Vince Shortino. “We have seen much better anime over the past two years,” he says. “Anime might finally be coming out of the moe (sexualized cuteness) rut.”

And over at Viz Media, the oldest U.S.-based distributor of Japanese pop culture, president and CEO Ken Sasaki tells me the focus is squarely on print. Viz plans to expand its manga catalog dramatically in 2014, spreading the English edition of “Weekly Shonen Jump,” Japan’s most popular manga magazine, into international markets beyond the U.S., Britain, Ireland, South Africa, Australia and New Zealand. He is also keen to see this summer’s blockbuster release “Edge of Tomorrow,” starring Tom Cruise and based on Hiroshi Sakurazaka’s novel, “All You Need is Kill,” published in English by Viz’s Haikasoru imprint.

Still, most anime experts and fans agree: For 2014, all roads lead back (or forward?) to Miyazaki and the future of his Studio Ghibli. British author Helen McCarthy, whose revised and updated “The Anime Encyclopedia” and new book, “A Brief History of Manga,” will be published later this year, is keeping an eye on Mamoru Hosoda (“Summer Wars,” “Okami Kodomo no Ame to Yuki [Wolf Children]“), whom she and others consider an artistic heir to Miyazaki. But she also holds out hope that Miyazaki might, in Solomon’s words, “rescind his retirement.”

McCarthy points me to a recent interview with Miyazaki’s longtime friend and artistic partner at Ghibli, Isao Takahata, whose latest film, “Kaguya-hime no Monogatari (The Tale of Princess Kaguya),” was released in Japan in late November. Takahata addresses his friend’s retirement with a shrug, effectively cautioning us to never say never.

“Although Hayao Miyazaki said he was retiring, I feel there is the possibility that could change,” he says. “I feel that way because I have worked with him for a very long time, (and) I don’t want people to be surprised if that is what happens.”

Roland Kelts is the author of “Japanamerica: How Japanese Pop Culture has Invaded the U.S.” He is a visiting scholar at Keio University in Tokyo.

Anime/manga experts hopeful for year ahead

BY ROLAND KELTS

Aside from Hayao Miyazaki’s sudden departure from filmmaking in September, the anime world saw some potentially hopeful developments in 2013.

Hayao Miyazaki and Susan J. Napier at Studio Ghibli, Tokyo, January, 2014.

Hayao Miyazaki and Susan J. Napier at Studio Ghibli, Tokyo, January, 2014.As I reported here, the government’s multibillion-yen Cool Japan Fund was launched last summer, after years of empty promises. Following the lead of Crunchyroll, the profitable San Francisco-based online anime and manga portal, domestic startups such as Daisuki began streaming anime series globally. Crunchyroll itself opened a digital manga site — and got a Christmas-time jolt of Hollywood cash from big-ticket investor The Chernin Group. A bold new apocalyptic anime series, “Shingeki no Kyojin (Attack on Titan),” earned raves and fans, as did the virtual reality adventure, "Sword Art Online," and the jazz-inflected new show “Kids on the Slope,” from veteran Shinichiro Watanabe (“Cowboy Bebop,” “Samurai Champloo”).

“In the United States, perhaps the worst (for anime) is in the rearview mirror now,” says author and translator Frederik L. Schodt.

“The market is probably half of what it was in 2007,” he admits, “but the fan base still seems dedicated and even growing. Rather than going to conventions to watch films and buy merchandise, which the Internet has rendered unnecessary, the conventions in the U.S. seem to be evolving into something different. They are more of a place to socialize, wear costumes and consort with like-minded fans. In a way, they may be becoming more decoupled from Japan, more autonomous, and even more uniquely American.”

"Sword Art Online," courtesy of Crunchyroll.com

"Sword Art Online," courtesy of Crunchyroll.comThe robust anime-convention industry is especially notable amid ongoing economic malaise. Both Anime Expo and Otakon, the U.S. West and East coasts’ largest conventions, respectively, reported sky-high tallies, with the latter opening its first satellite convention in Las Vegas at the start of this month. As Schodt notes, unlike the Tokyo International Anime Fair (TAF), which is more of a trade show to unveil industry offerings and announcements, conventions in the U.S. serve a communal, celebratory function. The fans come first.

Speaking of TAF, this year’s event, now renamed Anime Japan, will bring together the entire industry for the first time since 2011. That was when producers and publishers opposed to then Tokyo Gov. Shintaro Ishihara’s Bill 156, outlawing so-called “harmful” anime and manga, abandoned TAF (which Ishihara chaired) and created their own show, The Anime Contents Expo. While both were canceled in the wake of disaster in March 2011, they have since been held at similar times but separate locations — creating logistical headaches for attendees from Japan and overseas. The two will reunite this March, now that Ishihara is out of the picture.

Alas, his legislation isn’t. For criminal and commercial reasons, Tokyo-based translator and manga author Dan Kanemitsu sees dark days ahead. “My prediction is that the ruling Liberal Democratic Party will argue that the police can be trusted with more powers (to enforce Ishihara’s manga law),” he says, citing the increasingly conservative bent of the current administration and hysteria over the 2020 Olympics. “There will be a lot of noise from the opposition, but there won’t be as much heated protest as with the state secrets bill that just passed.”

Kanemitsu is also concerned about coming changes in Japanese copyright legislation that may accompany passage of the Trans-Pacific Partnership trade pact, for which the U.S. is pressing Prime Minister Shinzo Abe hard. “The TPP’s restrictive copyright regime is thought to be detrimental to Japan’s dōjin-shi (fan art) and online parody communities, since parody and fair use are not protected under Japanese copyright laws, and the chances that these provisions will be given protection is rather slim.

“If the TPP is passed per America’s demands, the police will no longer need permission from holders of copyright to go after violators. Any charge by a third party that a copyright violation is in progress will be enough for the police to arrest someone.”

He adds that criminal and commercial pressures combined will force some manga publishers to shutter this year, and that several artists have already told him they are thinking of quitting.

Coincidentally, after Miyazaki quit anime, he moved on to manga, and is reportedly drawing a series about samurai. “Studio Ghibli is the big story of 2014,” says professor and author Susan J. Napier, who is writing a book on Miyazaki. “The staff remain superb, and there is a rumor that ‘Evangelion’ director Hideaki Anno might film a sequel to Miyazaki’s early masterpiece, ‘Nausicaä.’ I’d pay double to see that combination realized!”

Animation critic and author Charles Solomon notes that U.S fans are looking forward to the imminent release of Anno’s “Evangelion: 3.0 You Can (Not) Redo,” and wonders if Miyazaki’s latest, “Kaze Tachinu (The Wind Rises),” will receive an Oscar nod next month, owing to its subject matter. “Will American viewers accept a film about the designer of the Zero fighter — especially the older members of the Academy, who may remember World War II?”

Viz Media President and CEO, Ken Sasaki

Viz Media President and CEO, Ken SasakiFor the broader U.S. fan base, “Naruto,” “Bleach” and “One Piece” remain top sellers — but they were joined last year by the grisly “Attack on Titan,” about flesh-eating giants. In real-time video rankings on Crunchyroll, which streams the show worldwide, “Attack” periodically knocked “Naruto” out of the top perch, where it has been for five consecutive years, according to the site’s Japan general manager, Vince Shortino. “We have seen much better anime over the past two years,” he says. “Anime might finally be coming out of the moe (sexualized cuteness) rut.”

And over at Viz Media, the oldest U.S.-based distributor of Japanese pop culture, president and CEO Ken Sasaki tells me the focus is squarely on print. Viz plans to expand its manga catalog dramatically in 2014, spreading the English edition of “Weekly Shonen Jump,” Japan’s most popular manga magazine, into international markets beyond the U.S., Britain, Ireland, South Africa, Australia and New Zealand. He is also keen to see this summer’s blockbuster release “Edge of Tomorrow,” starring Tom Cruise and based on Hiroshi Sakurazaka’s novel, “All You Need is Kill,” published in English by Viz’s Haikasoru imprint.

Still, most anime experts and fans agree: For 2014, all roads lead back (or forward?) to Miyazaki and the future of his Studio Ghibli. British author Helen McCarthy, whose revised and updated “The Anime Encyclopedia” and new book, “A Brief History of Manga,” will be published later this year, is keeping an eye on Mamoru Hosoda (“Summer Wars,” “Okami Kodomo no Ame to Yuki [Wolf Children]“), whom she and others consider an artistic heir to Miyazaki. But she also holds out hope that Miyazaki might, in Solomon’s words, “rescind his retirement.”

McCarthy points me to a recent interview with Miyazaki’s longtime friend and artistic partner at Ghibli, Isao Takahata, whose latest film, “Kaguya-hime no Monogatari (The Tale of Princess Kaguya),” was released in Japan in late November. Takahata addresses his friend’s retirement with a shrug, effectively cautioning us to never say never.

“Although Hayao Miyazaki said he was retiring, I feel there is the possibility that could change,” he says. “I feel that way because I have worked with him for a very long time, (and) I don’t want people to be surprised if that is what happens.”

Roland Kelts is the author of “Japanamerica: How Japanese Pop Culture has Invaded the U.S.” He is a visiting scholar at Keio University in Tokyo.

Published on January 10, 2014 05:39

January 2, 2014

The joys of Tomoko for The New Yorker

TOMOKO SUGIMOTO’S MONOZUKURI

BY ROLAND KELTS

[Tomoko Sugimoto photographed by Chris Mosier]

[Tomoko Sugimoto photographed by Chris Mosier]

The expatriate Japanese artist Tomoko Sugimoto’s first solo show in the United States, “Whirl and Swallow,” was held in Brooklyn on March 12, 2011, one day after Japan’s earthquake, tsunami, and nuclear meltdown. Sugimoto got word of the disasters in New York, where she has lived since 1996. She didn’t think anyone would show up. The gallery owner in Williamsburg and her close friends urged her to see it through, and she did, preparing for the exhibition with one eye on the increasingly grim television footage from her native land. “At first, I was so depressed,” she said. “We already knew what was happening and could see these crazy scenes, and the numbers of dead kept rising. We were very upset. But so many people came. I think everyone came to see each other and talk to each other. And people kept saying to me, ‘I feel a little better now just viewing your work. I feel a happy energy.’ ”

That happy energy filled two small rooms and a narrow corridor last month, at Sugimoto’s first solo show in Manhattan. Cast in soft, auburn-yellow light, Sugimoto’s work—a deceptively plain combination of cotton-thread embroidery on canvas and sparsely applied acrylic paints and watercolors—looked both joyous and comforting. Some viewers (including this one) appeared perplexed at first, seeking out the conceptual and/or cultural codes embedded in much twenty-first-century art from Japan, whose most commercially successful practitioner, Takashi Murakami, dazzles with fun-house-mirror distortions of Japanese pop-cultural imagery, and whose reigning doyenne, Yayoi Kusama, pummels with polka dots.

Instead, we were confronted by figurative portraits in gentle pastels of children at play, twirling about and dangling from a gymnastics pole, as in the show’s eponymous centerpiece triptych, “Turn Around and Around, Then Around.” Or dancing through space, kicking, and diving in “Jumping Into Jello” and “Popping Onto Pudding.” Flowers, raccoons, monkeys, deer, and insects punctuated a series based on the Japanese zodiac, most of the figures somehow aloft, relishing their physical freedom.

“At first, I thought my subjects were too common,” Sugimoto told me afterward, at a SoHo restaurant. “But maybe people need that now. Just being in the moment. One lady came up to me after the reception and said, ‘Thank you so much for your art. I see a lot of shows, but this was the first time I looked at art and said, Wow, I really want that! I want that energy inside me.’ ” Sugimoto added, “When I go to some art shows, I think, Yes, that’s really dark. But I also feel I don’t need any more of that right now.”

Sugimoto’s mother is an artist and art teacher in Japan, and she grew up surrounded by catalogues of works by European Impressionists, American modernists, Japanese scroll painters, manga artists—and even Charles M. Schulz’s “Peanuts,” which her mother adored. (“We were never rich enough to be collectors, so my mother collected catalogues.”) She recalls being a child in a tatami-mat room with plain paper pinned to the walls so she could draw whatever she wanted. She attended Musashino Art University, in Tokyo, and moved to New York when she was accepted into a program for artists from Asia at the School of Visual Arts. A year after her enrollment, she encountered the well-documented “outsider artist” Henry Darger’s work at an exhibition uptown. Darger’s illustrations echoed the “crazy human figures” she loved as a child in a catalogue of the Austrian artist and architect Friedensreich Hundertwasser. She decided to become an illustrator.

But she needed a job. Winter set in, and the rising global superstar Murakami was advertising in the help-wanted listings. It was mostly for the visa, Sugimoto says now, but she took a job at Murakami’s Brooklyn studio, later called KaiKai Kiki, which helped her learn about the international art scene and Japan’s place and reputation in it. “Honestly, the visa was the most important thing at the time,” she said. “My mother was always pushing me to do my own thing. ‘Why did you take that job with Takashi?’ she asked. But now that he’s famous, she’s really happy.”

Murakami’s anime- and manga-inspired paintings and sculptures started selling for millions, and his friendships and collaborations with Louis Vuitton and Kanye West placed him at the center of an art-world spotlight. Sugimoto became Murakami’s New York–based art director as he and his cadre of fellow pop-oriented artists rapidly defined what the world perceived as contemporary Japanese art. Andy Warhol–style, Murakami even coined a handy, if reductive, term for it: “Superflat,” 2-D imagery sans aesthetic hierarchies. Sugimoto and her colleagues were responsible for executing Murakami’s ideas with the materials available to them in New York. She can’t offer an objective opinion about his body of work, she tells me, because she was too close to the act of bringing it to life. “What I learned most from him was passion, the determination to be an artist no matter what happened.”

The American art critic Megan M. Garwood, who wrote the catalogue introduction for “Turn Around,” sees Sugimoto’s work as a triumph of craft over conceptualization, from a country where craft and art remain interchangeable—the Japanese notion of monozukuri, or “making things well,” can be found in its lacquerware, food, and electronics. “This is not happening in America,” Garwood said. “In America, the type of art that is coming from the same age group is so overly conceptual. There’s no being loose with it. It’s all about ‘me.’ Japanese artists seem to be identifying with a communal perspective. They’re not getting overindulgent in the process of trying to destroy what came before them; they’re using art to say something very intimate that we all need.”

Kohei Nawa, a contemporary of Sugimoto’s whose work includes so-called “pixcellized” deer—taxidermies covered with glass baubles—recently told the Times that the new generation of Japanese artists no longer feel the need to represent Japan with self-referential imagery, pop or otherwise. But Sugimoto is proud of her Japanese ancestry, and happy to celebrate and embody it in her work. “I’m a Japanese, yes, but I live in America,” she said. “Embroidery is a European and American craft, true, but I use it in a Japanese way, with rough industrial canvas to express organic textures, like tatami, and two-dimensional portraits of classical Japanese subjects in nature. Maybe Nawa feels differently because he’s living in Japan and needs to protect his space.” She paused, then added, “I’m free from all that.”

Roland Kelts is the author of

BY ROLAND KELTS

[Tomoko Sugimoto photographed by Chris Mosier]

[Tomoko Sugimoto photographed by Chris Mosier]

The expatriate Japanese artist Tomoko Sugimoto’s first solo show in the United States, “Whirl and Swallow,” was held in Brooklyn on March 12, 2011, one day after Japan’s earthquake, tsunami, and nuclear meltdown. Sugimoto got word of the disasters in New York, where she has lived since 1996. She didn’t think anyone would show up. The gallery owner in Williamsburg and her close friends urged her to see it through, and she did, preparing for the exhibition with one eye on the increasingly grim television footage from her native land. “At first, I was so depressed,” she said. “We already knew what was happening and could see these crazy scenes, and the numbers of dead kept rising. We were very upset. But so many people came. I think everyone came to see each other and talk to each other. And people kept saying to me, ‘I feel a little better now just viewing your work. I feel a happy energy.’ ”

That happy energy filled two small rooms and a narrow corridor last month, at Sugimoto’s first solo show in Manhattan. Cast in soft, auburn-yellow light, Sugimoto’s work—a deceptively plain combination of cotton-thread embroidery on canvas and sparsely applied acrylic paints and watercolors—looked both joyous and comforting. Some viewers (including this one) appeared perplexed at first, seeking out the conceptual and/or cultural codes embedded in much twenty-first-century art from Japan, whose most commercially successful practitioner, Takashi Murakami, dazzles with fun-house-mirror distortions of Japanese pop-cultural imagery, and whose reigning doyenne, Yayoi Kusama, pummels with polka dots.

Instead, we were confronted by figurative portraits in gentle pastels of children at play, twirling about and dangling from a gymnastics pole, as in the show’s eponymous centerpiece triptych, “Turn Around and Around, Then Around.” Or dancing through space, kicking, and diving in “Jumping Into Jello” and “Popping Onto Pudding.” Flowers, raccoons, monkeys, deer, and insects punctuated a series based on the Japanese zodiac, most of the figures somehow aloft, relishing their physical freedom.

“At first, I thought my subjects were too common,” Sugimoto told me afterward, at a SoHo restaurant. “But maybe people need that now. Just being in the moment. One lady came up to me after the reception and said, ‘Thank you so much for your art. I see a lot of shows, but this was the first time I looked at art and said, Wow, I really want that! I want that energy inside me.’ ” Sugimoto added, “When I go to some art shows, I think, Yes, that’s really dark. But I also feel I don’t need any more of that right now.”

Sugimoto’s mother is an artist and art teacher in Japan, and she grew up surrounded by catalogues of works by European Impressionists, American modernists, Japanese scroll painters, manga artists—and even Charles M. Schulz’s “Peanuts,” which her mother adored. (“We were never rich enough to be collectors, so my mother collected catalogues.”) She recalls being a child in a tatami-mat room with plain paper pinned to the walls so she could draw whatever she wanted. She attended Musashino Art University, in Tokyo, and moved to New York when she was accepted into a program for artists from Asia at the School of Visual Arts. A year after her enrollment, she encountered the well-documented “outsider artist” Henry Darger’s work at an exhibition uptown. Darger’s illustrations echoed the “crazy human figures” she loved as a child in a catalogue of the Austrian artist and architect Friedensreich Hundertwasser. She decided to become an illustrator.

But she needed a job. Winter set in, and the rising global superstar Murakami was advertising in the help-wanted listings. It was mostly for the visa, Sugimoto says now, but she took a job at Murakami’s Brooklyn studio, later called KaiKai Kiki, which helped her learn about the international art scene and Japan’s place and reputation in it. “Honestly, the visa was the most important thing at the time,” she said. “My mother was always pushing me to do my own thing. ‘Why did you take that job with Takashi?’ she asked. But now that he’s famous, she’s really happy.”

Murakami’s anime- and manga-inspired paintings and sculptures started selling for millions, and his friendships and collaborations with Louis Vuitton and Kanye West placed him at the center of an art-world spotlight. Sugimoto became Murakami’s New York–based art director as he and his cadre of fellow pop-oriented artists rapidly defined what the world perceived as contemporary Japanese art. Andy Warhol–style, Murakami even coined a handy, if reductive, term for it: “Superflat,” 2-D imagery sans aesthetic hierarchies. Sugimoto and her colleagues were responsible for executing Murakami’s ideas with the materials available to them in New York. She can’t offer an objective opinion about his body of work, she tells me, because she was too close to the act of bringing it to life. “What I learned most from him was passion, the determination to be an artist no matter what happened.”

The American art critic Megan M. Garwood, who wrote the catalogue introduction for “Turn Around,” sees Sugimoto’s work as a triumph of craft over conceptualization, from a country where craft and art remain interchangeable—the Japanese notion of monozukuri, or “making things well,” can be found in its lacquerware, food, and electronics. “This is not happening in America,” Garwood said. “In America, the type of art that is coming from the same age group is so overly conceptual. There’s no being loose with it. It’s all about ‘me.’ Japanese artists seem to be identifying with a communal perspective. They’re not getting overindulgent in the process of trying to destroy what came before them; they’re using art to say something very intimate that we all need.”

Kohei Nawa, a contemporary of Sugimoto’s whose work includes so-called “pixcellized” deer—taxidermies covered with glass baubles—recently told the Times that the new generation of Japanese artists no longer feel the need to represent Japan with self-referential imagery, pop or otherwise. But Sugimoto is proud of her Japanese ancestry, and happy to celebrate and embody it in her work. “I’m a Japanese, yes, but I live in America,” she said. “Embroidery is a European and American craft, true, but I use it in a Japanese way, with rough industrial canvas to express organic textures, like tatami, and two-dimensional portraits of classical Japanese subjects in nature. Maybe Nawa feels differently because he’s living in Japan and needs to protect his space.” She paused, then added, “I’m free from all that.”

Roland Kelts is the author of

Published on January 02, 2014 07:52

The joys of Tomoko -- my latest for The New Yorker

TOMOKO SUGIMOTO’S MONOZUKURI

BY ROLAND KELTS

[Tomoko Sugimoto photographed by Chris Mosier]

[Tomoko Sugimoto photographed by Chris Mosier]

The expatriate Japanese artist Tomoko Sugimoto’s first solo show in the United States, “Whirl and Swallow,” was held in Brooklyn on March 12, 2011, one day after Japan’s earthquake, tsunami, and nuclear meltdown. Sugimoto got word of the disasters in New York, where she has lived since 1996. She didn’t think anyone would show up. The gallery owner in Williamsburg and her close friends urged her to see it through, and she did, preparing for the exhibition with one eye on the increasingly grim television footage from her native land. “At first, I was so depressed,” she said. “We already knew what was happening and could see these crazy scenes, and the numbers of dead kept rising. We were very upset. But so many people came. I think everyone came to see each other and talk to each other. And people kept saying to me, ‘I feel a little better now just viewing your work. I feel a happy energy.’ ”

That happy energy filled two small rooms and a narrow corridor last month, at Sugimoto’s first solo show in Manhattan. Cast in soft, auburn-yellow light, Sugimoto’s work—a deceptively plain combination of cotton-thread embroidery on canvas and sparsely applied acrylic paints and watercolors—looked both joyous and comforting. Some viewers (including this one) appeared perplexed at first, seeking out the conceptual and/or cultural codes embedded in much twenty-first-century art from Japan, whose most commercially successful practitioner, Takashi Murakami, dazzles with fun-house-mirror distortions of Japanese pop-cultural imagery, and whose reigning doyenne, Yayoi Kusama, pummels with polka dots.

Instead, we were confronted by figurative portraits in gentle pastels of children at play, twirling about and dangling from a gymnastics pole, as in the show’s eponymous centerpiece triptych, “Turn Around and Around, Then Around.” Or dancing through space, kicking, and diving in “Jumping Into Jello” and “Popping Onto Pudding.” Flowers, raccoons, monkeys, deer, and insects punctuated a series based on the Japanese zodiac, most of the figures somehow aloft, relishing their physical freedom.

“At first, I thought my subjects were too common,” Sugimoto told me afterward, at a SoHo restaurant. “But maybe people need that now. Just being in the moment. One lady came up to me after the reception and said, ‘Thank you so much for your art. I see a lot of shows, but this was the first time I looked at art and said, Wow, I really want that! I want that energy inside me.’ ” Sugimoto added, “When I go to some art shows, I think, Yes, that’s really dark. But I also feel I don’t need any more of that right now.”

Sugimoto’s mother is an artist and art teacher in Japan, and she grew up surrounded by catalogues of works by European Impressionists, American modernists, Japanese scroll painters, manga artists—and even Charles M. Schulz’s “Peanuts,” which her mother adored. (“We were never rich enough to be collectors, so my mother collected catalogues.”) She recalls being a child in a tatami-mat room with plain paper pinned to the walls so she could draw whatever she wanted. She attended Musashino Art University, in Tokyo, and moved to New York when she was accepted into a program for artists from Asia at the School of Visual Arts. A year after her enrollment, she encountered the well-documented “outsider artist” Henry Darger’s work at an exhibition uptown. Darger’s illustrations echoed the “crazy human figures” she loved as a child in a catalogue of the Austrian artist and architect Friedensreich Hundertwasser. She decided to become an illustrator.

But she needed a job. Winter set in, and the rising global superstar Murakami was advertising in the help-wanted listings. It was mostly for the visa, Sugimoto says now, but she took a job at Murakami’s Brooklyn studio, later called KaiKai Kiki, which helped her learn about the international art scene and Japan’s place and reputation in it. “Honestly, the visa was the most important thing at the time,” she said. “My mother was always pushing me to do my own thing. ‘Why did you take that job with Takashi?’ she asked. But now that he’s famous, she’s really happy.”

Murakami’s anime- and manga-inspired paintings and sculptures started selling for millions, and his friendships and collaborations with Louis Vuitton and Kanye West placed him at the center of an art-world spotlight. Sugimoto became Murakami’s New York–based art director as he and his cadre of fellow pop-oriented artists rapidly defined what the world perceived as contemporary Japanese art. Andy Warhol–style, Murakami even coined a handy, if reductive, term for it: “Superflat,” 2-D imagery sans aesthetic hierarchies. Sugimoto and her colleagues were responsible for executing Murakami’s ideas with the materials available to them in New York. She can’t offer an objective opinion about his body of work, she tells me, because she was too close to the act of bringing it to life. “What I learned most from him was passion, the determination to be an artist no matter what happened.”

The American art critic Megan M. Garwood, who wrote the catalogue introduction for “Turn Around,” sees Sugimoto’s work as a triumph of craft over conceptualization, from a country where craft and art remain interchangeable—the Japanese notion of monozukuri, or “making things well,” can be found in its lacquerware, food, and electronics. “This is not happening in America,” Garwood said. “In America, the type of art that is coming from the same age group is so overly conceptual. There’s no being loose with it. It’s all about ‘me.’ Japanese artists seem to be identifying with a communal perspective. They’re not getting overindulgent in the process of trying to destroy what came before them; they’re using art to say something very intimate that we all need.”

Kohei Nawa, a contemporary of Sugimoto’s whose work includes so-called “pixcellized” deer—taxidermies covered with glass baubles—recently told the Times that the new generation of Japanese artists no longer feel the need to represent Japan with self-referential imagery, pop or otherwise. But Sugimoto is proud of her Japanese ancestry, and happy to celebrate and embody it in her work. “I’m a Japanese, yes, but I live in America,” she said. “Embroidery is a European and American craft, true, but I use it in a Japanese way, with rough industrial canvas to express organic textures, like tatami, and two-dimensional portraits of classical Japanese subjects in nature. Maybe Nawa feels differently because he’s living in Japan and needs to protect his space.” She paused, then added, “I’m free from all that.”

Roland Kelts is the author of

BY ROLAND KELTS

[Tomoko Sugimoto photographed by Chris Mosier]

[Tomoko Sugimoto photographed by Chris Mosier]

The expatriate Japanese artist Tomoko Sugimoto’s first solo show in the United States, “Whirl and Swallow,” was held in Brooklyn on March 12, 2011, one day after Japan’s earthquake, tsunami, and nuclear meltdown. Sugimoto got word of the disasters in New York, where she has lived since 1996. She didn’t think anyone would show up. The gallery owner in Williamsburg and her close friends urged her to see it through, and she did, preparing for the exhibition with one eye on the increasingly grim television footage from her native land. “At first, I was so depressed,” she said. “We already knew what was happening and could see these crazy scenes, and the numbers of dead kept rising. We were very upset. But so many people came. I think everyone came to see each other and talk to each other. And people kept saying to me, ‘I feel a little better now just viewing your work. I feel a happy energy.’ ”

That happy energy filled two small rooms and a narrow corridor last month, at Sugimoto’s first solo show in Manhattan. Cast in soft, auburn-yellow light, Sugimoto’s work—a deceptively plain combination of cotton-thread embroidery on canvas and sparsely applied acrylic paints and watercolors—looked both joyous and comforting. Some viewers (including this one) appeared perplexed at first, seeking out the conceptual and/or cultural codes embedded in much twenty-first-century art from Japan, whose most commercially successful practitioner, Takashi Murakami, dazzles with fun-house-mirror distortions of Japanese pop-cultural imagery, and whose reigning doyenne, Yayoi Kusama, pummels with polka dots.

Instead, we were confronted by figurative portraits in gentle pastels of children at play, twirling about and dangling from a gymnastics pole, as in the show’s eponymous centerpiece triptych, “Turn Around and Around, Then Around.” Or dancing through space, kicking, and diving in “Jumping Into Jello” and “Popping Onto Pudding.” Flowers, raccoons, monkeys, deer, and insects punctuated a series based on the Japanese zodiac, most of the figures somehow aloft, relishing their physical freedom.

“At first, I thought my subjects were too common,” Sugimoto told me afterward, at a SoHo restaurant. “But maybe people need that now. Just being in the moment. One lady came up to me after the reception and said, ‘Thank you so much for your art. I see a lot of shows, but this was the first time I looked at art and said, Wow, I really want that! I want that energy inside me.’ ” Sugimoto added, “When I go to some art shows, I think, Yes, that’s really dark. But I also feel I don’t need any more of that right now.”

Sugimoto’s mother is an artist and art teacher in Japan, and she grew up surrounded by catalogues of works by European Impressionists, American modernists, Japanese scroll painters, manga artists—and even Charles M. Schulz’s “Peanuts,” which her mother adored. (“We were never rich enough to be collectors, so my mother collected catalogues.”) She recalls being a child in a tatami-mat room with plain paper pinned to the walls so she could draw whatever she wanted. She attended Musashino Art University, in Tokyo, and moved to New York when she was accepted into a program for artists from Asia at the School of Visual Arts. A year after her enrollment, she encountered the well-documented “outsider artist” Henry Darger’s work at an exhibition uptown. Darger’s illustrations echoed the “crazy human figures” she loved as a child in a catalogue of the Austrian artist and architect Friedensreich Hundertwasser. She decided to become an illustrator.

But she needed a job. Winter set in, and the rising global superstar Murakami was advertising in the help-wanted listings. It was mostly for the visa, Sugimoto says now, but she took a job at Murakami’s Brooklyn studio, later called KaiKai Kiki, which helped her learn about the international art scene and Japan’s place and reputation in it. “Honestly, the visa was the most important thing at the time,” she said. “My mother was always pushing me to do my own thing. ‘Why did you take that job with Takashi?’ she asked. But now that he’s famous, she’s really happy.”

Murakami’s anime- and manga-inspired paintings and sculptures started selling for millions, and his friendships and collaborations with Louis Vuitton and Kanye West placed him at the center of an art-world spotlight. Sugimoto became Murakami’s New York–based art director as he and his cadre of fellow pop-oriented artists rapidly defined what the world perceived as contemporary Japanese art. Andy Warhol–style, Murakami even coined a handy, if reductive, term for it: “Superflat,” 2-D imagery sans aesthetic hierarchies. Sugimoto and her colleagues were responsible for executing Murakami’s ideas with the materials available to them in New York. She can’t offer an objective opinion about his body of work, she tells me, because she was too close to the act of bringing it to life. “What I learned most from him was passion, the determination to be an artist no matter what happened.”

The American art critic Megan M. Garwood, who wrote the catalogue introduction for “Turn Around,” sees Sugimoto’s work as a triumph of craft over conceptualization, from a country where craft and art remain interchangeable—the Japanese notion of monozukuri, or “making things well,” can be found in its lacquerware, food, and electronics. “This is not happening in America,” Garwood said. “In America, the type of art that is coming from the same age group is so overly conceptual. There’s no being loose with it. It’s all about ‘me.’ Japanese artists seem to be identifying with a communal perspective. They’re not getting overindulgent in the process of trying to destroy what came before them; they’re using art to say something very intimate that we all need.”

Kohei Nawa, a contemporary of Sugimoto’s whose work includes so-called “pixcellized” deer—taxidermies covered with glass baubles—recently told the Times that the new generation of Japanese artists no longer feel the need to represent Japan with self-referential imagery, pop or otherwise. But Sugimoto is proud of her Japanese ancestry, and happy to celebrate and embody it in her work. “I’m a Japanese, yes, but I live in America,” she said. “Embroidery is a European and American craft, true, but I use it in a Japanese way, with rough industrial canvas to express organic textures, like tatami, and two-dimensional portraits of classical Japanese subjects in nature. Maybe Nawa feels differently because he’s living in Japan and needs to protect his space.” She paused, then added, “I’m free from all that.”

Roland Kelts is the author of

Published on January 02, 2014 07:52

December 31, 2013

Akeome, Kotoyoro / Happy New Year

Published on December 31, 2013 09:57

Akemashite Omedetou / Happy New Year

Published on December 31, 2013 09:57

December 24, 2013

Hols exhausted

Published on December 24, 2013 22:31