Roland Kelts's Blog, page 41

February 27, 2014

Monkey 4!

take me to bed...

Monkey Business International

is the in-translation offspring of the Tokyo-based magazine Monkey Business, which was founded in 2008 by Motoyuki Shibata, one of Japan’s most highly regarded men of letters.

Monkey Business International

is the in-translation offspring of the Tokyo-based magazine Monkey Business, which was founded in 2008 by Motoyuki Shibata, one of Japan’s most highly regarded men of letters.MBI aims to translate and present a wide array of established and emerging authors, showcasing the best of contemporary Japanese literature.

With the generous support of the Nippon Foundation, A Public Space is the publisher and partner of Monkey Business International. MB and APS first conceived of MBI when Shibata curated a portfolio of Japanese literature in the debut issue of APS.

Issue 4 opens with a new contributor, Craft Ebbing Co., a designer duo who tells the story of a mysterious box alongside color pictures of their exquisite craftsmanship. Richard Powers brainfully unpacks the most-talked-about living Japanese author, Haruki Murakami, and Kodansha Prize-winning translator Roger Pulvers unveils “The Restaurant of Many Orders,” one of the most popular stories by beloved Japanese giant, Kenji Miyazaki. Sci Fi wiz Toh Enjoe joins Monkey stalwarts Gen’ichiro Takashi, Hiromi Kawakami, Hideo Furukawa and Sachiko Kishimoto — plus debuts of new writers you must meet in our hungry pages.

Published on February 27, 2014 08:05

February 19, 2014

On tour in Toronto, 2/24 - 28

Official page here.

a pop culture lecture series withRoland Keltsauthor of Japanamerica: How Japanese Pop Culture Has Invaded the U.S.

a pop culture lecture series withRoland Keltsauthor of Japanamerica: How Japanese Pop Culture Has Invaded the U.S.

The Japan Foundation, Toronto is delighted to announce another special guest during our pop culture-focused month! Roland Kelts, author of the bestseller Japanamerica: How Japanese Culture Has Invaded the U.S., will share his insights on Japan's greatest manga artist, Osamu Tezuka, and the mutual influence of Anime and Hollywood. He will also join our manga artist-in-residence, Nao Yazawa, for a dialogue on the state of pop culture in Japan.

The Life and Works of the God of Manga, Osamu Tezuka

Monday, February 24, 7 pm (doors 6:30 pm)

Anime and Hollywood (the dance of rivals seeking to embrace)

Tuesday, February 25, 6:30 pm (doors 6 pm)

Roland Kelts in Conversation with Nao Yazawa

Thursday, February 27, 6:30 pm (doors 6 pm)

Location: All events will take place at The Japan Foundation, Toronto

Address: 131 Bloor St. W., 2nd Floor of the Colonnade Building

Admission: FREE

RSVP: www.jftor.org/whatson/rsvp.php

The Life and Works of the God of Manga, Osamu Tezuka

Monday, February 24, 7 pm (doors 6:30 pm)

In this intimate lecture, Roland Kelts, author of Japanamerica and contributing writer for The New Yorker, introduces the tremendously influential and genre-defining works of manga master Osamu Tezuka, best known for his works Astro Boy and Black Jack. Expert Kelts engages with longtime fans and novices to answer questions and explore the manga master’s legendary works in a fresh new context. The trauma of World War II, Japan's postwar faith in science and reinvention, and today's ambivalence toward atomic power drive Kelts's fresh analysis. There will also be a book sale and signing at the event.

Language: English

RSVP: www.jftor.org/whatson/rsvp.php

Anime and Hollywood

(the dance of rivals seeking to embrace)

Tuesday, February 25, 6:30 pm (doors 6 pm)

Roland Kelts talks about modern Anime, its influences on Hollywood, and vice-versa. An in-depth examination of how Japanese and American entertainment businesses are influencing each other in an infinite loop. Just as Japanese artists like Osamu Tezuka, Hayao Miyazaki and Katsuhiro Otomo were fascinated by classic and sci-fi American movies, George Lucas, The Wachowskis, Guillermo del Toro and other directors were influenced by Japanese anime classics like Gatchaman, Speed Racer, Spirited Away, Akira and Ghost in the Shell.

In his presentation, Kelts will explore why Hollywood is fascinated with Japanese pop culture and is trying to remake popular Japanese anime titles to appeal to a whole new generation of viewers. Death Note, Naruto, Cowboy Bebop and the attempts to make feature films out of stalwarts like Dragon Ball Z and Grave of the Fireflies will be addressed with passion. Anime vs. Hollywood: Who wins? A close look at the challenges and potential missteps along the way.

Language: English

RSVP: www.jftor.org/whatson/rsvp.php

In Conversation with Manga Artist Nao Yazawa

Thursday, February 27, 6:30 pm (doors 6 pm)

We will begin to wrap up our month of pop culture events with a conversation between our two special guests! Scholar Roland Kelts and manga artist Nao Yazawa will sit down for a discussion on the current state of pop culture in Japan. Shojo and shonen manga, anime, film, fashion, Akihabara- join us for a lively talk between two pop culture experts.

Language: English and Japanese with English interpretation

RSVP: www.jftor.org/whatson/rsvp.php

a pop culture lecture series withRoland Keltsauthor of Japanamerica: How Japanese Pop Culture Has Invaded the U.S.

a pop culture lecture series withRoland Keltsauthor of Japanamerica: How Japanese Pop Culture Has Invaded the U.S.The Japan Foundation, Toronto is delighted to announce another special guest during our pop culture-focused month! Roland Kelts, author of the bestseller Japanamerica: How Japanese Culture Has Invaded the U.S., will share his insights on Japan's greatest manga artist, Osamu Tezuka, and the mutual influence of Anime and Hollywood. He will also join our manga artist-in-residence, Nao Yazawa, for a dialogue on the state of pop culture in Japan.

The Life and Works of the God of Manga, Osamu Tezuka

Monday, February 24, 7 pm (doors 6:30 pm)

Anime and Hollywood (the dance of rivals seeking to embrace)

Tuesday, February 25, 6:30 pm (doors 6 pm)

Roland Kelts in Conversation with Nao Yazawa

Thursday, February 27, 6:30 pm (doors 6 pm)

Location: All events will take place at The Japan Foundation, Toronto

Address: 131 Bloor St. W., 2nd Floor of the Colonnade Building

Admission: FREE

RSVP: www.jftor.org/whatson/rsvp.php

The Life and Works of the God of Manga, Osamu Tezuka

Monday, February 24, 7 pm (doors 6:30 pm)

In this intimate lecture, Roland Kelts, author of Japanamerica and contributing writer for The New Yorker, introduces the tremendously influential and genre-defining works of manga master Osamu Tezuka, best known for his works Astro Boy and Black Jack. Expert Kelts engages with longtime fans and novices to answer questions and explore the manga master’s legendary works in a fresh new context. The trauma of World War II, Japan's postwar faith in science and reinvention, and today's ambivalence toward atomic power drive Kelts's fresh analysis. There will also be a book sale and signing at the event.

Language: English

RSVP: www.jftor.org/whatson/rsvp.php

Anime and Hollywood

(the dance of rivals seeking to embrace)

Tuesday, February 25, 6:30 pm (doors 6 pm)

Roland Kelts talks about modern Anime, its influences on Hollywood, and vice-versa. An in-depth examination of how Japanese and American entertainment businesses are influencing each other in an infinite loop. Just as Japanese artists like Osamu Tezuka, Hayao Miyazaki and Katsuhiro Otomo were fascinated by classic and sci-fi American movies, George Lucas, The Wachowskis, Guillermo del Toro and other directors were influenced by Japanese anime classics like Gatchaman, Speed Racer, Spirited Away, Akira and Ghost in the Shell.

In his presentation, Kelts will explore why Hollywood is fascinated with Japanese pop culture and is trying to remake popular Japanese anime titles to appeal to a whole new generation of viewers. Death Note, Naruto, Cowboy Bebop and the attempts to make feature films out of stalwarts like Dragon Ball Z and Grave of the Fireflies will be addressed with passion. Anime vs. Hollywood: Who wins? A close look at the challenges and potential missteps along the way.

Language: English

RSVP: www.jftor.org/whatson/rsvp.php

In Conversation with Manga Artist Nao Yazawa

Thursday, February 27, 6:30 pm (doors 6 pm)

We will begin to wrap up our month of pop culture events with a conversation between our two special guests! Scholar Roland Kelts and manga artist Nao Yazawa will sit down for a discussion on the current state of pop culture in Japan. Shojo and shonen manga, anime, film, fashion, Akihabara- join us for a lively talk between two pop culture experts.

Language: English and Japanese with English interpretation

RSVP: www.jftor.org/whatson/rsvp.php

Published on February 19, 2014 06:12

February 17, 2014

Behind the "Japan Beethoven" fraud for NPR

Published on February 17, 2014 05:00

February 14, 2014

Anime, games & retro "Wonder Momo" -- latest column for The Japan Times

CULTURE| CULTURE SMASH

The symbiotic relationship between anime and games

BY ROLAND KELTS

Japan excels at making you play. From its flower arrangements to tea ceremonies to karaoke, nothing much happens until you get into the game, and a big part of Japan’s appeal to non-natives is its invitation to engage.

Tourists and expats gleefully bear floats on their shoulders during Japanese festivals, don kimono for photo shoots and pound rice cakes for the New Year’s holidays. The otaku (obsessives) who gather for AKB48 shows in Akihabara pay to touch their idols’ hands, reenact choreographed dance moves and snap photos of the girls. At anime conventions in North America, Europe and Asia, attendees hand-make costumes to inhabit the roles of their favorite anime characters, performing skits tailored to the series they love.

Making you play is at the heart of many of Japan’s most successful pop-cultural anime and game properties to date, “Pokémon” chief among them. As anthropologist Anne Allison notes in “Millennial Monsters,” her brilliant study of toys, economics and culture, “Pokémon” was an anime series built around a game at its center. The “exchange and battle” of the game made the anime story lines that much more intimate and urgent. A global generation was raised on the premise that you had to see the show to get a leg up on the game, and you had to collect the cards to play the game to keep up with the show. You couldn’t just watch and amass models à la “Star Wars”; you had to act.

Recent years have seen both the anime and game industries undergoing rapid transformation — consolidation, downsizing and outsourcing — to meet the challenge of cross-platform digital media and the proliferation of low-priced content or outright freebies and piracy. The global economic downturn of 2008 and the collapse of the Nintendo Wii’s market of casual users didn’t help. Industry-watchers and fans complain that the quality of the content has taken a downturn, too.

Anime-game tie-ups, mash-ups and co-releases give creators a shot at maximizing the value of popular characters and titles. Last year, Luffy from “One Piece” and Goku from “Dragonball Z” appeared in the same TV episode. Gaming giant Sega just announced that the forthcoming release of its new game “Hero Bank,” which already has a manga tie-in, will be followed by an anime series later this spring. RPG developer Level 5′s soccer-battle game, “Inazuma Eleven,” and spirit-hunting “Yokai Watch” feature manga and anime series — the latter of which launched last month on TV Tokyo amid rumors of an imminent overseas release, after Level 5 reportedly trademarked the title in the United States.

Another way around the content quandary is to follow Hollywood’s approach to classic comic-book heroes: Revive and update properties to reach audiences both new and old. At a private presentation two weeks ago, Bandai Namco unveiled plans for its forthcoming game and anime series, “Wonder Momo,” a revived property that first saw life as an arcade game — in 1987.

Bandai Namco’s Rob Pereyda, editor in chief and producer of ShiftyLook, the company’s Web-comic site and incubation platform, says that he wants to awaken “sleeping intellectual properties” from the company’s decades-long history, which includes an estimated 10,000 characters. The Internet provides for borderless interactivity: a platform for contributions from overseas artists and instant access to fans of Bandai Namco’s titles. The “Wonder Momo” comic series, already under way on ShiftyLook.com, is created by three artists in Canada, while the game is being developed and designed by WayForward Technologies, a studio in Los Angeles.

Pereyda chose “Wonder Momo,” featuring a wannabe idol with battle-ready superpowers and an extremely powerful kick, for its narrative potential. “Twenty-seven years ago, games didn’t have much of a story line,” he says. “But this character was so good, so interesting. Momo has appeared in other games, too, like ‘Namco × Capcom.’ So while she has only had one game of her own, she has a great fan base in Japan. And I think audiences overseas will see it as a sexy, cool action anime.”

The potential for cross-generational appeal is embodied in the game’s director, WayForward’s James Montagna, who was born the year the original “Wonder Momo” debuted in arcades. But Montagna grew up on a steady diet of anime, from “Pokémon,” “Sailor Moon” and “Dragonball Z” to titles that were then less well-known in America, such as “Ranma ½.” He points out that “Pokémon” originated as a game, a title created by Satoshi Tajiri for Nintendo’s Game Boy device. ” ‘Wonder Momo’ and ‘Pokémon’ have that in common,” he says. “They both started as games and were later turned into anime.”

“Wonder Momo” will push its retro appeal hard. The game features an old-school token-earning system, Montagna explains, that will enable players to collect enough to continue playing after they lose. “Arcade gamers will find it nostalgic,” he says, “but it will be a new style for gamers who may have only played touch games, like ‘Angry Birds.’ “

Plus ça change, perhaps. But amid the mash-ups, revivals and tie-ups, you start to wonder: Is anyone creating anything genuinely new, a property that is strong enough to stand on its own?

Roland Kelts is the author of

The symbiotic relationship between anime and games

BY ROLAND KELTS

Japan excels at making you play. From its flower arrangements to tea ceremonies to karaoke, nothing much happens until you get into the game, and a big part of Japan’s appeal to non-natives is its invitation to engage.

Tourists and expats gleefully bear floats on their shoulders during Japanese festivals, don kimono for photo shoots and pound rice cakes for the New Year’s holidays. The otaku (obsessives) who gather for AKB48 shows in Akihabara pay to touch their idols’ hands, reenact choreographed dance moves and snap photos of the girls. At anime conventions in North America, Europe and Asia, attendees hand-make costumes to inhabit the roles of their favorite anime characters, performing skits tailored to the series they love.

Making you play is at the heart of many of Japan’s most successful pop-cultural anime and game properties to date, “Pokémon” chief among them. As anthropologist Anne Allison notes in “Millennial Monsters,” her brilliant study of toys, economics and culture, “Pokémon” was an anime series built around a game at its center. The “exchange and battle” of the game made the anime story lines that much more intimate and urgent. A global generation was raised on the premise that you had to see the show to get a leg up on the game, and you had to collect the cards to play the game to keep up with the show. You couldn’t just watch and amass models à la “Star Wars”; you had to act.

Recent years have seen both the anime and game industries undergoing rapid transformation — consolidation, downsizing and outsourcing — to meet the challenge of cross-platform digital media and the proliferation of low-priced content or outright freebies and piracy. The global economic downturn of 2008 and the collapse of the Nintendo Wii’s market of casual users didn’t help. Industry-watchers and fans complain that the quality of the content has taken a downturn, too.

Anime-game tie-ups, mash-ups and co-releases give creators a shot at maximizing the value of popular characters and titles. Last year, Luffy from “One Piece” and Goku from “Dragonball Z” appeared in the same TV episode. Gaming giant Sega just announced that the forthcoming release of its new game “Hero Bank,” which already has a manga tie-in, will be followed by an anime series later this spring. RPG developer Level 5′s soccer-battle game, “Inazuma Eleven,” and spirit-hunting “Yokai Watch” feature manga and anime series — the latter of which launched last month on TV Tokyo amid rumors of an imminent overseas release, after Level 5 reportedly trademarked the title in the United States.

Another way around the content quandary is to follow Hollywood’s approach to classic comic-book heroes: Revive and update properties to reach audiences both new and old. At a private presentation two weeks ago, Bandai Namco unveiled plans for its forthcoming game and anime series, “Wonder Momo,” a revived property that first saw life as an arcade game — in 1987.

Bandai Namco’s Rob Pereyda, editor in chief and producer of ShiftyLook, the company’s Web-comic site and incubation platform, says that he wants to awaken “sleeping intellectual properties” from the company’s decades-long history, which includes an estimated 10,000 characters. The Internet provides for borderless interactivity: a platform for contributions from overseas artists and instant access to fans of Bandai Namco’s titles. The “Wonder Momo” comic series, already under way on ShiftyLook.com, is created by three artists in Canada, while the game is being developed and designed by WayForward Technologies, a studio in Los Angeles.

Pereyda chose “Wonder Momo,” featuring a wannabe idol with battle-ready superpowers and an extremely powerful kick, for its narrative potential. “Twenty-seven years ago, games didn’t have much of a story line,” he says. “But this character was so good, so interesting. Momo has appeared in other games, too, like ‘Namco × Capcom.’ So while she has only had one game of her own, she has a great fan base in Japan. And I think audiences overseas will see it as a sexy, cool action anime.”

The potential for cross-generational appeal is embodied in the game’s director, WayForward’s James Montagna, who was born the year the original “Wonder Momo” debuted in arcades. But Montagna grew up on a steady diet of anime, from “Pokémon,” “Sailor Moon” and “Dragonball Z” to titles that were then less well-known in America, such as “Ranma ½.” He points out that “Pokémon” originated as a game, a title created by Satoshi Tajiri for Nintendo’s Game Boy device. ” ‘Wonder Momo’ and ‘Pokémon’ have that in common,” he says. “They both started as games and were later turned into anime.”

“Wonder Momo” will push its retro appeal hard. The game features an old-school token-earning system, Montagna explains, that will enable players to collect enough to continue playing after they lose. “Arcade gamers will find it nostalgic,” he says, “but it will be a new style for gamers who may have only played touch games, like ‘Angry Birds.’ “

Plus ça change, perhaps. But amid the mash-ups, revivals and tie-ups, you start to wonder: Is anyone creating anything genuinely new, a property that is strong enough to stand on its own?

Roland Kelts is the author of

Published on February 14, 2014 06:40

February 10, 2014

Solomon & Otomo

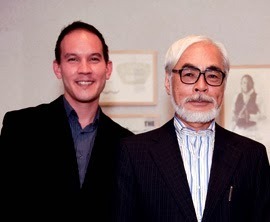

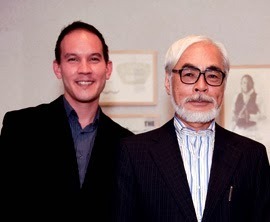

Our dear friend, animation critic, author, scholar and Disney historian Charles Solomon presented the Winsor McCay Career Achievement Award to "Akira" creator Katsuhiro Otomo at the 41st Annie Awards in Los Angeles earlier this month. And all we got was this not-so-lousy pic:

Solomon meets Otomo in LA.

Solomon meets Otomo in LA.

Solomon meets Otomo in LA.

Solomon meets Otomo in LA.

Published on February 10, 2014 05:22

January 31, 2014

Anime giant Otomo in LA 2/1 for Annie Awards

Katsuhiro Otomo (AKIRA) will be in Los Angeles today (Sat., Feb. 1) to receive the Winsor McCay award for career achievement at the Annie Awards. My good friend Charles Solomon, who wrote the story below, will present the trophy. (from The Los Angeles Times)

Annie Awards to honor animator Katsuhiro Otomo for career achievement

The cyberpunk “Akira” in 1988 brought global acclaim to artist Katsuhiro Otomo. (FUNimation Entertainment )

By Charles Solomon

Legendary Japanese animator Katsuhiro Otomo is known around the world for his work, particularly his groundbreaking cyberpunk action feature "Akira." But Otomo doesn't spend time watching his own films.

"The truth is, I don't read or watch my own creations," Otomo says. "When I'm creating something, I'm 100% immersed in that universe, so when I'm finished, I'm ready to journey to a different world. Once a work is completed, it belongs to the readers and viewers."

One of the most influential artists working in animation today, Otomo will receive the Winsor McCay Award for career achievement at the Annie Awards on Saturday. Frank Gladstone, president of the Assn. Internationale du Film d'Animation, or ASIFA, said that "for the board, it was an easy decision to present Mr. Otomo with the McCay Award: His influence and achievements have been consistent and unparalleled."

Best known as the director of the 1988 manga classic "Akira," Otomo, 59, talked about his work via email from Tokyo last week. The McCay trophy follows the prestigious Medal with Purple Ribbon he received from the Japanese government last year; in 2005, the French government conferred the title of Knight of the Order of Arts and Letters.

"I'm honored to receive such a fabulous award," Otomo said about the McCay honor. "But I don't think about awards when I'm working."

Otomo was fascinated by movies as a teenager, sometimes traveling three hours by train to see films that didn't play in his rural home town. "When I was in high school, I had a vague idea of wanting to become a manga artist or a movie director," he recalled. "Having grown up in the countryside, I had no idea how to enter such an occupation. But I knew that to begin, I had to move to Tokyo."

Otomo arrived in Tokyo after graduating high school in 1973, and he quickly established himself as a writer, manga artist and animation-character designer. In 1983, he began "Akira," a dark, sprawling epic that ran as a serial for eight years.

In 1988, Otomo directed and co-wrote the animated feature of "Akira," the film credited with creating a mass audience for Japanese animation in America. "Akira" is set in 2019, 31 years after Tokyo was destroyed during World War III. The glittering skyscrapers of Neo-Tokyo loom over a grimy under-city, where brutal military officers subject Tetsuo, the weakest member of a teen-age biker gang, to biomedical experiments that go terribly wrong.

Roland Kelts, the author of "Japanamerica: How Japanese Pop Culture Has Invaded the U.S.," said that "Otomo completely transformed my awareness of animation as an art form. I first saw 'Akira' when I was in college. I remember talking about it for hours with three other friends who were similarly shaken by Otomo's vision and techniques, and by his seamless blend of spiritual psychosis and institutional corruption. He is one of a handful of Japan's, and the world's, greatest living animators, and his art continues to expand the boundaries of visual expression."

Although he's identified with the brooding "Akira," Otomo's work encompasses a wide spectrum of moods, graphic looks and subjects. He drew and wrote the charming manga "SOS! Tokyo Metro Explorers," about a group of schoolboys searching for lost treasure under the modern city. He wrote and directed the lavish Victorian Steampunk adventure "Steamboy," and wrote the screenplay for the action-comedy "Roujin Z," in which a group of feisty senior citizens hijack a military robot.

"I don't try to make my viewers or readers like something," Otomo said. "I think my works that receive praise show exactly that. They're pieces I thought were intriguing — I was fully alive in those worlds. I don't know exactly what the Japanese audience — or another country's audience — is feeling, but I don't believe that everyone who goes to movies goes to see a happy ending every time. If everyone was happy, movies and entertainment would be unnecessary."

Last year, Otomo completed "Short Peace," an animated anthology that includes four segments by different directors. His segment, "Combustible," a tale of Edo-period star-crossed lovers in the 18th century, styled after antique woodblock prints, made the short list for the Oscar for Animated Short Film last year. Shuhei Morita's segment, "Possessions," in which a samurai faces the angry spirits of umbrellas and other objects that resent being abandoned by humans after years of faithful service, is nominated in the same category this year.

Otomo declines to comment on the prospect of a live-action remake of "Akira," a project that's been kicking around Hollywood for more than a decade: "I illustrated the manga then directed the animated film: I will not be involved a third time." But he's directed one live-action movie, an adaptation of Yuki Urushibara's supernatural manga "Mushishi," and would like to do more,

"I would love to make live-action films, but have not had many opportunities. I'd have to start by finding trustworthy staff, which is very difficult. But I will do it. I'm thinking of making a live-action film next."

Annie Awards to honor animator Katsuhiro Otomo for career achievement

The cyberpunk “Akira” in 1988 brought global acclaim to artist Katsuhiro Otomo. (FUNimation Entertainment )

By Charles Solomon

Legendary Japanese animator Katsuhiro Otomo is known around the world for his work, particularly his groundbreaking cyberpunk action feature "Akira." But Otomo doesn't spend time watching his own films.

"The truth is, I don't read or watch my own creations," Otomo says. "When I'm creating something, I'm 100% immersed in that universe, so when I'm finished, I'm ready to journey to a different world. Once a work is completed, it belongs to the readers and viewers."

One of the most influential artists working in animation today, Otomo will receive the Winsor McCay Award for career achievement at the Annie Awards on Saturday. Frank Gladstone, president of the Assn. Internationale du Film d'Animation, or ASIFA, said that "for the board, it was an easy decision to present Mr. Otomo with the McCay Award: His influence and achievements have been consistent and unparalleled."

Best known as the director of the 1988 manga classic "Akira," Otomo, 59, talked about his work via email from Tokyo last week. The McCay trophy follows the prestigious Medal with Purple Ribbon he received from the Japanese government last year; in 2005, the French government conferred the title of Knight of the Order of Arts and Letters.

"I'm honored to receive such a fabulous award," Otomo said about the McCay honor. "But I don't think about awards when I'm working."

Otomo was fascinated by movies as a teenager, sometimes traveling three hours by train to see films that didn't play in his rural home town. "When I was in high school, I had a vague idea of wanting to become a manga artist or a movie director," he recalled. "Having grown up in the countryside, I had no idea how to enter such an occupation. But I knew that to begin, I had to move to Tokyo."

Otomo arrived in Tokyo after graduating high school in 1973, and he quickly established himself as a writer, manga artist and animation-character designer. In 1983, he began "Akira," a dark, sprawling epic that ran as a serial for eight years.

In 1988, Otomo directed and co-wrote the animated feature of "Akira," the film credited with creating a mass audience for Japanese animation in America. "Akira" is set in 2019, 31 years after Tokyo was destroyed during World War III. The glittering skyscrapers of Neo-Tokyo loom over a grimy under-city, where brutal military officers subject Tetsuo, the weakest member of a teen-age biker gang, to biomedical experiments that go terribly wrong.

Roland Kelts, the author of "Japanamerica: How Japanese Pop Culture Has Invaded the U.S.," said that "Otomo completely transformed my awareness of animation as an art form. I first saw 'Akira' when I was in college. I remember talking about it for hours with three other friends who were similarly shaken by Otomo's vision and techniques, and by his seamless blend of spiritual psychosis and institutional corruption. He is one of a handful of Japan's, and the world's, greatest living animators, and his art continues to expand the boundaries of visual expression."

Although he's identified with the brooding "Akira," Otomo's work encompasses a wide spectrum of moods, graphic looks and subjects. He drew and wrote the charming manga "SOS! Tokyo Metro Explorers," about a group of schoolboys searching for lost treasure under the modern city. He wrote and directed the lavish Victorian Steampunk adventure "Steamboy," and wrote the screenplay for the action-comedy "Roujin Z," in which a group of feisty senior citizens hijack a military robot.

"I don't try to make my viewers or readers like something," Otomo said. "I think my works that receive praise show exactly that. They're pieces I thought were intriguing — I was fully alive in those worlds. I don't know exactly what the Japanese audience — or another country's audience — is feeling, but I don't believe that everyone who goes to movies goes to see a happy ending every time. If everyone was happy, movies and entertainment would be unnecessary."

Last year, Otomo completed "Short Peace," an animated anthology that includes four segments by different directors. His segment, "Combustible," a tale of Edo-period star-crossed lovers in the 18th century, styled after antique woodblock prints, made the short list for the Oscar for Animated Short Film last year. Shuhei Morita's segment, "Possessions," in which a samurai faces the angry spirits of umbrellas and other objects that resent being abandoned by humans after years of faithful service, is nominated in the same category this year.

Otomo declines to comment on the prospect of a live-action remake of "Akira," a project that's been kicking around Hollywood for more than a decade: "I illustrated the manga then directed the animated film: I will not be involved a third time." But he's directed one live-action movie, an adaptation of Yuki Urushibara's supernatural manga "Mushishi," and would like to do more,

"I would love to make live-action films, but have not had many opportunities. I'd have to start by finding trustworthy staff, which is very difficult. But I will do it. I'm thinking of making a live-action film next."

Published on January 31, 2014 21:26

January 30, 2014

January 28, 2014

Otakon redux

Published on January 28, 2014 01:10

January 24, 2014

'The Wind Rises': the beauty and controversy of Miyazaki'...

'The Wind Rises': the beauty and controversy of Miyazaki's final filmThe World War II biopic sparks an animated debateBy Sam Byford

Hayao Miyazaki's The Wind Rises is a lot of things. It's the final feature-length film from one of the all-time greats of Japanese animation. It's a gorgeous, Oscar-nominated work that brings prewar Japan to life in ways that have never been seen before. It's Miyazaki's most pointedly adult movie, with a slow-burning tragedy replacing the magical realism and cute characters that have made Studio Ghibli's films appeal across generations. And it's the most controversial animated movie in recent memory.

That's because The Wind Rises is a sympathetic biography of a man whose work contributed to Japan's brutal campaign of imperialist aggression during World War II. Jiro Horikoshi designed the Mitsubishi A6M Zero fighter plane that Japan used in Pearl Harbor and countless other assaults; the Zero was feared for the unparalleled range and maneuverability bestowed by Horikoshi's considerable engineering skills. Although its subject matter is linked to a violent past, The Wind Rises follows in the tradition of Japanese works that eulogize artisanal passion and dedication to one's craft — it could almost have been called Jiro Dreams of Fighter Planes.

Why would Miyazaki choose to end his career on such a contentious note? He told a magazine in 2011 that he was drawn to Horikoshi's alleged statement that "All I wanted to do was to make something beautiful." The aircraft designer "also embodies many of Miyazaki's own contradictions," says Roland Kelts, author of Japanamerica, who has interviewed the director. "[Miyazaki is] a pacifist whose father earned his income during the war working for a fighter plane parts manufacturer, and a committed artist who also tried to appreciate the realities of life, including a family he feels he often neglected. At times, Jiro seems inured to the suffering, corruption, and the needs of those around him as he pursues the realization of his dream. The results, of course, make for a great tragic drama."

Miyazaki, for his part, is one of the most prominent Japanese public figures to speak out against the country's imperialist past. He has been branded a "traitor" by Japanese nationalists for arguing against reforming the country's constitutionally enshrined pacifism — currently being pushed by right-wing prime minister Shinzo Abe — and saying that reparations should be paid to wartime sex slaves from Korea and China, euphemistically referred to as "comfort women." These issues, along with a series of territorial disputes, continue to be a source of tension between Japan and its Far Eastern neighbors.

"Including myself, a generation of Japanese men who grew up during a certain period have very complex feelings about World War II, and the Zero symbolizes our collective psyche," said Miyazaki in an interview with the Asahi Shimbun. "Japan went to war out of foolish arrogance, caused trouble throughout the entire East Asia, and ultimately brought destruction upon itself... but for all this humiliating history, the Zero represented one of the few things that we Japanese could be proud of." Despite the Zero's status as a fearsome war machine, Miyazaki was more concerned with the inspired mind behind its design. "It was the extraordinary genius of Jiro Horikoshi, the Zero's designer, that made it the finest state-of-the-art fighter plane of the time... Horikoshi intuitively understood the mystery of aerodynamics that nobody could explain in words."

Miyazaki's feelings for Horikoshi make more sense when you look at the director's filmography, which is filled with fantastical depictions of the magic of human flight. Movies such as Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind, Laputa: Castle in the Sky, and Kiki's Delivery Service see characters take to the skies with such joy and beauty that they could only have come from the mind of an artist so enamored with the concept. But those movies were set in fantasy worlds, with little to no historical context in the minds of the audience. The Wind Rises is different, bestowing the same sense of bewitchment and wonder on notorious war machines without spelling out what they were designed for. Given the setting, did Miyazaki have a responsibility to address Japan's wartime exploits more explicitly?

"The point is that the film still accommodates Japanese society's willful amnesia about World War II," Kang tells The Verge. "My problem is the 'pussyfooting' around war crimes I refer to in my piece. It's possible to make great, moral art out of problematic subjects." Kang notes that "no Japanese pilot is ever seen shooting at an enemy" in The Wind Rises, while the film's allusions to war see Chinese fighters and Japan's shaky alliance with Nazi Germany contributing to a creeping sense of dread.

Kelts, on the other hand, finds "the mini-brouhaha" around The Wind Rises "specious and self-serving," arguing that Miyazaki has no obligation to preach about the past. "If the film were about a pilot or general or army grunt, references to Japan's brutal colonization of Asia might be apt. But Jiro is working on the home front, designing what he believes will be a thing of beauty." And even if the movie touches a nerve among some viewers, it's clear that the director intended quite the opposite. "Miyazaki the man is open about his disgust at any hint of militarism in Japan and his abhorrence of politicians who ignorantly stoke its embers today," says Kelts. "Critics who focus their understandable anger over Japan's disposition 70-plus years ago on an artist whose every fibre agrees with them are wasting their words."

Moreover, the absence of bloody, consequential violence arguably supports the anti-war message that Miyazaki meant to send. At its core, The Wind Rises is about what happens when people forsake what really matters when pursuing their goals. "Jiro dreams of flight, and his dreams are often dragged to the ground by the corruption of real life," says Kelts. "It's as if Miyazaki wants to drive home the harsh difference between the two; the tragic near-impossibility of combining dreams and reality, and of living in both. If you choose one, you sacrifice the other." Jiro appears to sweep the ugly reality of his work into the far-off corners of his mind, concentrating on the nuts and bolts of aircraft design at the tragic expense of his partner, Naoko. This can be read as Miyazaki's indictment of the powers that turned Japan to brutality in its quest for global significance.

Whatever your take on The Wind Rises, there's nothing quite like it. "A film about a complex personal and national past that [Miyazaki] has long reflected upon, a meditation upon the joys and demands of art and craftsmanship, and a heartbreaking love story," summarizes Kelts. And even if some take issue with the way Miyazaki has handled its themes, the movie is an undeniable tour de force of animation — its rendering of the 1923 Great Kanto Earthquake in particular must be seen to be believed. "Just aesthetically speaking, I thought it was a beautiful film with some severe pacing issues," says Kang. American audiences will no doubt have a multitude of reactions when The Wind Rises sees wide release next month, but they shouldn't miss it. Hayao Miyazaki's final film is a provocative, wondrous work of art that won't soon be forgotten.

The Wind Rises will be in US theaters on February 21st.

Hayao Miyazaki's The Wind Rises is a lot of things. It's the final feature-length film from one of the all-time greats of Japanese animation. It's a gorgeous, Oscar-nominated work that brings prewar Japan to life in ways that have never been seen before. It's Miyazaki's most pointedly adult movie, with a slow-burning tragedy replacing the magical realism and cute characters that have made Studio Ghibli's films appeal across generations. And it's the most controversial animated movie in recent memory.

That's because The Wind Rises is a sympathetic biography of a man whose work contributed to Japan's brutal campaign of imperialist aggression during World War II. Jiro Horikoshi designed the Mitsubishi A6M Zero fighter plane that Japan used in Pearl Harbor and countless other assaults; the Zero was feared for the unparalleled range and maneuverability bestowed by Horikoshi's considerable engineering skills. Although its subject matter is linked to a violent past, The Wind Rises follows in the tradition of Japanese works that eulogize artisanal passion and dedication to one's craft — it could almost have been called Jiro Dreams of Fighter Planes.

Why would Miyazaki choose to end his career on such a contentious note? He told a magazine in 2011 that he was drawn to Horikoshi's alleged statement that "All I wanted to do was to make something beautiful." The aircraft designer "also embodies many of Miyazaki's own contradictions," says Roland Kelts, author of Japanamerica, who has interviewed the director. "[Miyazaki is] a pacifist whose father earned his income during the war working for a fighter plane parts manufacturer, and a committed artist who also tried to appreciate the realities of life, including a family he feels he often neglected. At times, Jiro seems inured to the suffering, corruption, and the needs of those around him as he pursues the realization of his dream. The results, of course, make for a great tragic drama."

Miyazaki, for his part, is one of the most prominent Japanese public figures to speak out against the country's imperialist past. He has been branded a "traitor" by Japanese nationalists for arguing against reforming the country's constitutionally enshrined pacifism — currently being pushed by right-wing prime minister Shinzo Abe — and saying that reparations should be paid to wartime sex slaves from Korea and China, euphemistically referred to as "comfort women." These issues, along with a series of territorial disputes, continue to be a source of tension between Japan and its Far Eastern neighbors.

"Including myself, a generation of Japanese men who grew up during a certain period have very complex feelings about World War II, and the Zero symbolizes our collective psyche," said Miyazaki in an interview with the Asahi Shimbun. "Japan went to war out of foolish arrogance, caused trouble throughout the entire East Asia, and ultimately brought destruction upon itself... but for all this humiliating history, the Zero represented one of the few things that we Japanese could be proud of." Despite the Zero's status as a fearsome war machine, Miyazaki was more concerned with the inspired mind behind its design. "It was the extraordinary genius of Jiro Horikoshi, the Zero's designer, that made it the finest state-of-the-art fighter plane of the time... Horikoshi intuitively understood the mystery of aerodynamics that nobody could explain in words."

Miyazaki's feelings for Horikoshi make more sense when you look at the director's filmography, which is filled with fantastical depictions of the magic of human flight. Movies such as Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind, Laputa: Castle in the Sky, and Kiki's Delivery Service see characters take to the skies with such joy and beauty that they could only have come from the mind of an artist so enamored with the concept. But those movies were set in fantasy worlds, with little to no historical context in the minds of the audience. The Wind Rises is different, bestowing the same sense of bewitchment and wonder on notorious war machines without spelling out what they were designed for. Given the setting, did Miyazaki have a responsibility to address Japan's wartime exploits more explicitly?

"The point is that the film still accommodates Japanese society's willful amnesia about World War II," Kang tells The Verge. "My problem is the 'pussyfooting' around war crimes I refer to in my piece. It's possible to make great, moral art out of problematic subjects." Kang notes that "no Japanese pilot is ever seen shooting at an enemy" in The Wind Rises, while the film's allusions to war see Chinese fighters and Japan's shaky alliance with Nazi Germany contributing to a creeping sense of dread.

Kelts, on the other hand, finds "the mini-brouhaha" around The Wind Rises "specious and self-serving," arguing that Miyazaki has no obligation to preach about the past. "If the film were about a pilot or general or army grunt, references to Japan's brutal colonization of Asia might be apt. But Jiro is working on the home front, designing what he believes will be a thing of beauty." And even if the movie touches a nerve among some viewers, it's clear that the director intended quite the opposite. "Miyazaki the man is open about his disgust at any hint of militarism in Japan and his abhorrence of politicians who ignorantly stoke its embers today," says Kelts. "Critics who focus their understandable anger over Japan's disposition 70-plus years ago on an artist whose every fibre agrees with them are wasting their words."

Moreover, the absence of bloody, consequential violence arguably supports the anti-war message that Miyazaki meant to send. At its core, The Wind Rises is about what happens when people forsake what really matters when pursuing their goals. "Jiro dreams of flight, and his dreams are often dragged to the ground by the corruption of real life," says Kelts. "It's as if Miyazaki wants to drive home the harsh difference between the two; the tragic near-impossibility of combining dreams and reality, and of living in both. If you choose one, you sacrifice the other." Jiro appears to sweep the ugly reality of his work into the far-off corners of his mind, concentrating on the nuts and bolts of aircraft design at the tragic expense of his partner, Naoko. This can be read as Miyazaki's indictment of the powers that turned Japan to brutality in its quest for global significance.

Whatever your take on The Wind Rises, there's nothing quite like it. "A film about a complex personal and national past that [Miyazaki] has long reflected upon, a meditation upon the joys and demands of art and craftsmanship, and a heartbreaking love story," summarizes Kelts. And even if some take issue with the way Miyazaki has handled its themes, the movie is an undeniable tour de force of animation — its rendering of the 1923 Great Kanto Earthquake in particular must be seen to be believed. "Just aesthetically speaking, I thought it was a beautiful film with some severe pacing issues," says Kang. American audiences will no doubt have a multitude of reactions when The Wind Rises sees wide release next month, but they shouldn't miss it. Hayao Miyazaki's final film is a provocative, wondrous work of art that won't soon be forgotten.

The Wind Rises will be in US theaters on February 21st.

Published on January 24, 2014 02:40