Roland Kelts's Blog, page 40

April 10, 2014

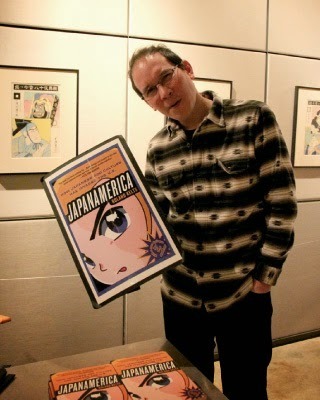

Tilted on tour in Toronto for Japanamerica

Toronto Japanamerica tour interview, via

『Japanamerica』著者、Roland Kelts氏に訊く日本と北米のマンガ・アニメ産業

Roland Keltsさん

Roland Kelts

日本のポップ・カルチャーがアメリカに及ぼした影響、そして互いに切磋琢磨しながら変革するマンガ・アニメ業界を鋭い視線で分析した『Japanamerica』の著者。他にもThe New YorkerやThe Wall Street Journalをはじめとする数多くの新聞・雑誌に記事、エッセイなどを寄稿。

東京大学や上智大学などの客員講師を務め、東京とニューヨークを行き来する生活を送る。スタジオジブリの宮崎駿監督や、作家の村上春樹など、日本の作家へのインタビューも多く行っている。

日本マンガとの出会い

私が初めて日本に行ったのは幼稚園の時。母方の祖父母が住んでいる盛岡を初めて訪れた時でした。テレビを点けるとウルトラマンや仮面ライダーなど、いわゆる特撮ものがやっていて、それを夢中で観ていました。さらに祖父母の家にはマンガもあって、少しだけですけど、パラパラとめくって読んでいました。それが初めてのマンガとの出会いです。中学・高校生の時も、夏休みなどで日本に行くと、電車の中によく置き去りにされている読み終わったマンガ雑誌を集めては読んでいて、友人に見せようとアメリカの自宅にも持って帰ったりしていました(笑)アメコミのスパイダーマンなどと比べても、日本のマンガは格段におもしろいと感じ、友人に見せては、みんなで「すごい!」と興奮したものです。日本のマンガにはアクションシーンもたくさんあるし、セクシーな女の人も出てきて。それらの描写方法やデザインが、とても興味深かったのです。アメコミはどちらかというと絵柄が大きくて、ダイナミックなのに対し、日本のマンガは細かい絵が多く、フレーム使いも面白い。マンガに本格的に興味を持ち始めたのは、この頃だと思います。さらに今度は、川端康成に谷崎潤一郎、そして大学の時には村上春樹といった日本文学も読むようになりました。日本文学は私にとってとても新鮮なものでした。そうして、日本の物語というものにも興味を持ち始めたのです。後に、(映画監督の)フランシス・フォード・コッポラの会社にライターとして雇われ、日本の文化やライフスタイルを書くことになり、数年間大阪に住みました。この出来事が私の視野をより広げ、日本文化に関わり始めた出発点となりました。

日本と北米の違い ― 日本の持つ、独特の視覚文化

日本のマンガはヨーロッパのものに近いと思います。ストーリーも入り組んでいて、登場人物も、完璧な人間だけでなく、欠点などネガティブな一面を持つキャラクターもいる。ヨーロッパでも特にフランス、オランダ、ドイツのコミックは日本のスタイルに近いですね。一方、アメコミは、そのほとんどが子供向けか、スーパーヒーローもので、その中間がないのです。日本のように、これほど多くの種類のマンガを作っている国はないですよ。子供向けから、ティーン、主婦層向け、またシェフやワイン通といった特定層に受けるようなものまで、あらゆるライフスタイルを見出すことが日本のマンガではできます。また、日本では何かを教える手段としてもマンガが使われますよね。たとえば税金の仕組みを教えるものや、災害時の避難方法、または料理のレシピなど、さまざまな場面でマンガをみかけます。これは一種の視覚文化なのだと思います。子供の時、祖父母が日本からプレゼントで当時最新のソニーのウォークマンを贈ってくれたことがありました。もちろん取扱説明書は日本語で、僕には読めませんでした。ところが、日本のそういった説明書には、必ず挿絵がついてますよね。「お風呂にウォークマンを持ち込まないで!」などのメッセージも、大げさなくらいの表情の挿絵であらわされていたりする。だから、たとえ日本語が読めなくても、その挿絵で理解できる。また、日本に住んでいた時、広告などのジャンクメールがよく届いたのですが、どれもこれもアニメのキャラクターや各地のゆるキャラが使われているものばかりでした。その時、日本文化というものは視覚を大事にしていて、視覚が言語を超えたコミュニケーション手段であることに気付いたのです。これは日本の持つとても独特な文化だと思います。マンガがアメリカで出回り始めた当初も、日本語がわからない多くのアメリカ人読者は絵を楽しみ、その絵からストーリーを掴んでいました。絵によって、文化の壁すら超えることができたのです。

北米での広がり

海外での『NARUTO』や『ONE PIECE』などの少年マンガの人気は圧倒的ですが、『美少女戦士セーラームーン』の登場によって、新たに少女マンガのカテゴリーも確立されました。それ以前は、コミックといえば男の子のものという概念が強く、女性が主人公の『ワンダーウーマン』というアメコミもありましたが、これもあくまで男の子向けのアクションものでした。海外での少女マンガのカテゴリーはまだ発展途上ではありますが、ファンは確実についています。

日本のマンガ・アニメは若い世代を中心に、海外でもメインストリームとしてますます成長を見せています。北米では毎週のようにコンベンションが開催され、オハイオやネブラスカのような片田舎ですら、そういった催しが珍しくありません。

日本マンガ・アニメのこれから

世界に拡大する人気とは裏腹に、マンガ・アニメの商業利益は衰退しています。インターネットで簡単にフリーの動画が手に入るので、DVDの売上もどんどんと落ちてきているのが現状です。アニメ人気が拡大しながらも、売上に繋がっていないことに、日本のアニメ制作会社も嘆いていて、現在業界自体がある種の転換期を迎えているのです。オンライン配信するなど、今の新しい時代に順応させていくことで、なんとかして収益化を図る必要性があるのです。しかし、日本の企業の多くは年長者が力を持っていて、最新のデジタルメディアなどに親しみがある若い世代が活躍しにくいという環境が大きな問題です。上の世代はいまだDVDなどの物質的な媒体に捉われてしまっているのですが、それらから転換する時期が来ているということに気がつかなければいけません。

また、長年の間、アニメ産業のターゲットは日本国内だけで、海外に目を向ける必要はありませんでした。しかし近年、日本の少子化の影響で日本の制作会社も海外マーケットを視野に入れるようになりました。、しかしこれは非常に大きな挑戦でもあります。というのは、日本で人気のあるマンガでも、北米ではそれほどでもないというケースは往々にあり、その逆もあります。つまり、日本と海外で求められるテイストに違いがあるため、海外顧客の嗜好のリサーチも重要になってくるわけです。

最近では、韓国のマンガや中国のアニメも人気が出てきていますが、日本のマンガには60年近くの長い歴史があります。この間、ストーリーや作家たちの才能は着実に洗練されてきました。大友克洋、押井守、井上雄彦など、作家の世代の幅も広がり、この他にも浦沢直樹や松本大洋など多くの素晴らしい作家がいます。韓国や中国が今の日本と同じレベルのものを作れるようになるのは、おそらく10年、20年後になるでしょう。それだけ日本のマンガには歴史があり、時間をかけて熟成され、今に至っているのです。日本のマンガ・アニメの人気は落ちることなく、むしろこれからも拡大し続けるでしょう。

akahane-tsukasa-canpacificTranslator: Tsukasa Akahane (赤羽司)

津田塾大学を卒業後、日本にある翻訳会社でコーディネーターとして2年間勤務。その後、翻訳の学校に通い、昨年ワーキングホリデーでトロントに来加。CanPacific Collegeにて翻訳・通訳コースを受講終了。

『Japanamerica』著者、Roland Kelts氏に訊く日本と北米のマンガ・アニメ産業

Roland Keltsさん

Roland Kelts

日本のポップ・カルチャーがアメリカに及ぼした影響、そして互いに切磋琢磨しながら変革するマンガ・アニメ業界を鋭い視線で分析した『Japanamerica』の著者。他にもThe New YorkerやThe Wall Street Journalをはじめとする数多くの新聞・雑誌に記事、エッセイなどを寄稿。

東京大学や上智大学などの客員講師を務め、東京とニューヨークを行き来する生活を送る。スタジオジブリの宮崎駿監督や、作家の村上春樹など、日本の作家へのインタビューも多く行っている。

日本マンガとの出会い

私が初めて日本に行ったのは幼稚園の時。母方の祖父母が住んでいる盛岡を初めて訪れた時でした。テレビを点けるとウルトラマンや仮面ライダーなど、いわゆる特撮ものがやっていて、それを夢中で観ていました。さらに祖父母の家にはマンガもあって、少しだけですけど、パラパラとめくって読んでいました。それが初めてのマンガとの出会いです。中学・高校生の時も、夏休みなどで日本に行くと、電車の中によく置き去りにされている読み終わったマンガ雑誌を集めては読んでいて、友人に見せようとアメリカの自宅にも持って帰ったりしていました(笑)アメコミのスパイダーマンなどと比べても、日本のマンガは格段におもしろいと感じ、友人に見せては、みんなで「すごい!」と興奮したものです。日本のマンガにはアクションシーンもたくさんあるし、セクシーな女の人も出てきて。それらの描写方法やデザインが、とても興味深かったのです。アメコミはどちらかというと絵柄が大きくて、ダイナミックなのに対し、日本のマンガは細かい絵が多く、フレーム使いも面白い。マンガに本格的に興味を持ち始めたのは、この頃だと思います。さらに今度は、川端康成に谷崎潤一郎、そして大学の時には村上春樹といった日本文学も読むようになりました。日本文学は私にとってとても新鮮なものでした。そうして、日本の物語というものにも興味を持ち始めたのです。後に、(映画監督の)フランシス・フォード・コッポラの会社にライターとして雇われ、日本の文化やライフスタイルを書くことになり、数年間大阪に住みました。この出来事が私の視野をより広げ、日本文化に関わり始めた出発点となりました。

日本と北米の違い ― 日本の持つ、独特の視覚文化

日本のマンガはヨーロッパのものに近いと思います。ストーリーも入り組んでいて、登場人物も、完璧な人間だけでなく、欠点などネガティブな一面を持つキャラクターもいる。ヨーロッパでも特にフランス、オランダ、ドイツのコミックは日本のスタイルに近いですね。一方、アメコミは、そのほとんどが子供向けか、スーパーヒーローもので、その中間がないのです。日本のように、これほど多くの種類のマンガを作っている国はないですよ。子供向けから、ティーン、主婦層向け、またシェフやワイン通といった特定層に受けるようなものまで、あらゆるライフスタイルを見出すことが日本のマンガではできます。また、日本では何かを教える手段としてもマンガが使われますよね。たとえば税金の仕組みを教えるものや、災害時の避難方法、または料理のレシピなど、さまざまな場面でマンガをみかけます。これは一種の視覚文化なのだと思います。子供の時、祖父母が日本からプレゼントで当時最新のソニーのウォークマンを贈ってくれたことがありました。もちろん取扱説明書は日本語で、僕には読めませんでした。ところが、日本のそういった説明書には、必ず挿絵がついてますよね。「お風呂にウォークマンを持ち込まないで!」などのメッセージも、大げさなくらいの表情の挿絵であらわされていたりする。だから、たとえ日本語が読めなくても、その挿絵で理解できる。また、日本に住んでいた時、広告などのジャンクメールがよく届いたのですが、どれもこれもアニメのキャラクターや各地のゆるキャラが使われているものばかりでした。その時、日本文化というものは視覚を大事にしていて、視覚が言語を超えたコミュニケーション手段であることに気付いたのです。これは日本の持つとても独特な文化だと思います。マンガがアメリカで出回り始めた当初も、日本語がわからない多くのアメリカ人読者は絵を楽しみ、その絵からストーリーを掴んでいました。絵によって、文化の壁すら超えることができたのです。

北米での広がり

海外での『NARUTO』や『ONE PIECE』などの少年マンガの人気は圧倒的ですが、『美少女戦士セーラームーン』の登場によって、新たに少女マンガのカテゴリーも確立されました。それ以前は、コミックといえば男の子のものという概念が強く、女性が主人公の『ワンダーウーマン』というアメコミもありましたが、これもあくまで男の子向けのアクションものでした。海外での少女マンガのカテゴリーはまだ発展途上ではありますが、ファンは確実についています。

日本のマンガ・アニメは若い世代を中心に、海外でもメインストリームとしてますます成長を見せています。北米では毎週のようにコンベンションが開催され、オハイオやネブラスカのような片田舎ですら、そういった催しが珍しくありません。

日本マンガ・アニメのこれから

世界に拡大する人気とは裏腹に、マンガ・アニメの商業利益は衰退しています。インターネットで簡単にフリーの動画が手に入るので、DVDの売上もどんどんと落ちてきているのが現状です。アニメ人気が拡大しながらも、売上に繋がっていないことに、日本のアニメ制作会社も嘆いていて、現在業界自体がある種の転換期を迎えているのです。オンライン配信するなど、今の新しい時代に順応させていくことで、なんとかして収益化を図る必要性があるのです。しかし、日本の企業の多くは年長者が力を持っていて、最新のデジタルメディアなどに親しみがある若い世代が活躍しにくいという環境が大きな問題です。上の世代はいまだDVDなどの物質的な媒体に捉われてしまっているのですが、それらから転換する時期が来ているということに気がつかなければいけません。

また、長年の間、アニメ産業のターゲットは日本国内だけで、海外に目を向ける必要はありませんでした。しかし近年、日本の少子化の影響で日本の制作会社も海外マーケットを視野に入れるようになりました。、しかしこれは非常に大きな挑戦でもあります。というのは、日本で人気のあるマンガでも、北米ではそれほどでもないというケースは往々にあり、その逆もあります。つまり、日本と海外で求められるテイストに違いがあるため、海外顧客の嗜好のリサーチも重要になってくるわけです。

最近では、韓国のマンガや中国のアニメも人気が出てきていますが、日本のマンガには60年近くの長い歴史があります。この間、ストーリーや作家たちの才能は着実に洗練されてきました。大友克洋、押井守、井上雄彦など、作家の世代の幅も広がり、この他にも浦沢直樹や松本大洋など多くの素晴らしい作家がいます。韓国や中国が今の日本と同じレベルのものを作れるようになるのは、おそらく10年、20年後になるでしょう。それだけ日本のマンガには歴史があり、時間をかけて熟成され、今に至っているのです。日本のマンガ・アニメの人気は落ちることなく、むしろこれからも拡大し続けるでしょう。

akahane-tsukasa-canpacificTranslator: Tsukasa Akahane (赤羽司)

津田塾大学を卒業後、日本にある翻訳会社でコーディネーターとして2年間勤務。その後、翻訳の学校に通い、昨年ワーキングホリデーでトロントに来加。CanPacific Collegeにて翻訳・通訳コースを受講終了。

Published on April 10, 2014 01:57

April 3, 2014

Haruki Murakami tells me about American literature

>an excerpt from my interview w/Haruki for

A Public Space

.

Haruki Murakami’s translations include: Raymond Carver’s short stories, Truman Capote’s short stories; F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby, Mikal Gilmore’s Shot in the Heart, John Irving’s Setting Free the Bears, Tim O’Brien’s The Nuclear Age, Grace Paley’s Enormous Changes at the Last Minute, J. D. Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye; and Mark Strand’s Mr. and Mrs. Baby and Other Stories.

ROLAND KELTS You and I once discussed how difficult it is to be an individual in Japan, how lonely.

HARUKI MURAKAMI It’s still very difficult, but things have changed drastically in Japan over the last ten years. You know, when I was young, we were supposed to join a company, join the office or the academy. It was a very tight society. You had to belong to someplace. I didn’t want to do that, so I became independent as soon as I left college. And it was lonely.

But not these days. People graduate and immediately become freelancers. There’s a good and bad side, but I look at the good side. It’s a chance to be free.

RK Do people need to look to America today-—or can they stay at home?

HM These days, young Japanese are also looking to Asia and Europe. America isn’t the only one any more. When I was in my teens in the sixties, America was so big—everything was shiny and bright. When I was fifteen years old, I went to see Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers, in Kobe. That was my first encounter with jazz; I was so impressed. Those were very good days for American culture.

RK So other people in Japan were attracted to American culture then?

HM It was overwhelming! No one could stop it. I think before 1962 or 1963, no one in Japan knew what a grapefruit was. The other day I was reading an old translation of American fiction and there was a footnote explaining what one is. And there was no pizza then, no hamburger. When I was at university, around 1970, McDonald’s came to Japan and we went to try what kind of thing a hamburger is.

RK Were those positive experiences?

HM Of course. We are not French. They were very exciting experiences for us. I remember going to see Stanley Kubrick’s 2001 in 1970. That was quite an experience. I think that’s the peak of American culture.

RK But the image has changed, hasn’t it?

HM Well, in those days, America had two sides: the strong side, and the youthful, countercultural side. We criticized the Vietnam war, but we were still listening to Jimi Hendrix and the Doors. America had a sense of balance in those days that we admired.

RK And now?

HM I feel like that balance was lost somehow. I think most Japanese feel that way. You know, people don’t drink Coca-Cola anymore. In fact, the most popular drink in Japan these days is ocha [traditional Japanese barley tea].

RK Are Japanese taking more pride in Japan?

HM I don’t know if the Japanese are proud of Japan, but they don’t admire American imports. Most American rock is boring these days—too commercial, too dull. Just like Hollywood movies. Young people are starting to get interested in Japanese films, just like they’re listening to J-Pop [Japanese pop music].

Personally, I think most of J-Pop is garbage, just like anime. But some of it is good, and if it’s good, I feel closer to it because it’s Japanese.

RK What about American fiction?

HM Oh, it’s popular now. It’s strange. I think American writers have been very good over the past twenty years or so. When I was in my twenties, we had two camps—Barthelme and other postmodern writers; and the realists, like Updike. But starting in the eighties, we had a third stream—writers like John Irving, Raymond Carver, Tim O’Brien. When I read Carver’s stories, I was stunned.

RK What stunned you about Carver?

HM Nobody wrote stories like those. They went beyond common sense. He always chose a simple vocabulary. He wrote straightforward stories, with a sense of humor, a crispness, and an unpredictable story line and very bleak endings. His stories are about everyday life. I learned something from Raymond Carver about writing short stories.

RK What do you think you learned from Carver?

HM What he was saying with his short stories is that you have to be intellectual when you write, but the subject matter doesn’t have to be intellectual.

RK What about the other authors you’ve translated. Irving, for example. What did you learn from him?

HM I learned something from John Irving about writing novels—that kind of powerful storytelling voice. When I say I learn something from translation, it’s not a small, practical thing. It’s a big thing. The author’s breathing, his perspective, his sensations. I can feel those things when I translate.

You know, in the old days, people would trace the writing in good books. Japanese people used to trace the pages of The Tale of Genji, for example. You can learn so many things from tracing. It’s just like putting your feet into other people’s shoes. Translation is the same thing.

RK Do you learn from other translators, too? Do you read Shibata’s translations?

HM Oh yes. I love his translations. But we have different tastes. Paul Auster, Steve Erickson, Stuart Dybek, and Steven Millhauser—they’re great writers, but I wouldn’t translate their work. Which is good, because we have no conflicts.

I think Shibata likes more balanced fiction. It’s not easy to explain. But whenever I read his translations, I find a very well-balanced literary world—symmetrical. Auster is a good example: It’s like the music of J. S. Bach. It’s kind of mathematical. You could say the same thing about Erickson or Millhauser. Those are wonderful worlds they’re producing, but they are very rational. Sometimes things get crazy and chaotic, but seen from a distance, everything is rational and even stoic. I’m saying that in a complimentary way.

But with Carver and O’Brien, things get irrational sometimes. I guess I feel more comfortable when things are messy. I prefer that kind of world. But you know, when I translated The Nuclear Age by Tim O’Brien, every American I met said that’s his worst book. But I just loved it. I told O’Brien when I met him, and he was so suspicious. He said: “You did? You really did?”

RK As if you were the only one.

HM That’s right. But in Japan, many readers loved it. Sometimes I think American readers are missing something.

RK With Nuclear Age, what specifically do you think Americans missed?

HM You know, it’s not a profitable book. It doesn’t have balance. It’s very rambling, and it’s incomplete. But still, it has something very important to tell you. People don’t appreciate those incomplete books, I guess. But I could feel the heat in that book.

RK Do you think Americans are more conservative in their expectations?

HM I think American readers are sometimes too much, you know, New York Times Book Review.

RK Are there any younger authors you’re interested in translating?

HM You know, after those writers I mentioned—Carver, O’Brien, Irving —I haven’t found a good new book I want to translate. I’m wondering if it’s because I got old. I’m not a professional translator; I’m a writer, and I want to learn something from the work of translation. When you reach a certain point, it gets harder to learn from reading other writers’ work. I’d rather learn from the classics these days, books like The Great Gatsby or The Catcher in the Rye.

RK When you first talked to me about translating The Catcher in the Rye, one of the things you mentioned was a tension in the book, between an open world—democratic and free and pluralistic—and a closed world, controlled and manipulated and oppressive.

HM Yes. And these days, the closed worlds are getting stronger in many places. You have fundamentalists, cults, and militaries. But you can’t destroy closed worlds with arms. Their systems will still survive. For example, you could kill all the al Qaeda soldiers, but the closed system itself, the ideas, would survive. They’ll just move it somewhere else.

The best thing you can do is just show and tell: Show the good side of the open world. It takes a long time, but in the long term, those open circuits of the open world will outlast the closed worlds.

RK Why do you think closed worlds are acquiring strength now?

HM That’s very easy to answer. The world is very chaotic today. You have to think about so many things—your stock options, the it industry, which computer you should buy. You have fifty-four channels on dtv. You can know anything you want on the Internet. It’s all very complicated, and you can get lost.

But if you enter a small, closed world, you don’t have to think about anything. The guru or dictator will tell you what to do and think. It’s so simple and easy and seductive. Even to intelligent people, like the ones who entered Aum Shinrikyo [the cult that poisoned the Tokyo subways in 1995]. But it’s a trick. Once you enter the closed world, you can’t escape. The door is closed.

RK You’ve said elsewhere that the tension between those two worlds was part of what drove you to translate The Catcher in the Rye.

HM That’s right. The last time I read that book was in high school, thirty-nine years ago. I almost forgot the actual story, but when I translated it, I realized that it’s really about a disease of the mind, a kind of diseased American psyche. America’s social maladies. It’s a very short odyssey through the mind of the author; but it’s not just about him.

You know, his book has inspired some assassins—the man who killed John Lennon, and the man who tried to kill Ronald Reagan. His book has some connection to the darkness in people’s minds, and that’s very important. It’s a great book, but Salinger was very close to that closed world in himself. He’s in the open world as a novelist, of course, but I think his mind was getting closer to the closed world, and the book is ultimately ambivalent about the two worlds. Most people, in Japan and elsewhere, think the book is about a child against society. But it’s not that simple. He’s really judging the very values of life, weighing them in his right and left hands. And his judgment changes all the time. That’s what makes the book so thrilling.

RK After translating the novel, do you still feel that way?

HM Yes. Salinger was going down to the bottom of a dark obsession.

RK Like a well?

HM Yes. When I translated that book, I had to go down into the darkness with him. And sometimes it was kind of suffocating. But now I think it was a good experience for me.

RK What about translating Gatsby? What did you learn from Fitzgerald?

HM You know, I waited for twenty-five years to do this. In the early eighties. Hemingway was so popular in Japan, but very few people read Fitzgerald. I thought it wasn’t fair. I just wanted to translate this book, but I felt I wasn’t qualified yet to do it.

RK How do you feel about the book today?

HM Before I started translating it, I had felt that The Great Gatsby was a perfect novel. As I worked on it line by line, though, I began to feel that the magic of this novel lay in fact in its imperfection: long sentences without much consistency, certain excesses in setting, occasional lack of consistency in the way characters conduct themselves. The beauty this novel possesses is supported by the accumulation of all these imperfections. I might go so far as to say that it is a special kind of beauty which could only have been expressed by being imperfect. This is probably something I would never have realized if I hadn’t actually translated it into Japanese.

RK A few years ago, you compared your decision to return to Japan in 1995—after the Kobe earthquake and the Tokyo subway poisonings—to Fitzgerald’s decision to return to the U.S. from Paris in 1930.

HM I think Japan’s bubble economy can be compared to the 1920s in America. In that sense I believe that Japan’s “lost decade”—from 1995 to 2005—was a crucial period for the country. We have yet to see what significance the period had for us, but I personally feel that in that decade I did my best as a Japanese novelist. My great theme during those ten years—and probably our theme—was to lay the groundwork for a way to coexist with everyday chaos. Now it’s time to see how good I was—to put my attempt to the test.

Haruki Murakami’s translations include: Raymond Carver’s short stories, Truman Capote’s short stories; F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby, Mikal Gilmore’s Shot in the Heart, John Irving’s Setting Free the Bears, Tim O’Brien’s The Nuclear Age, Grace Paley’s Enormous Changes at the Last Minute, J. D. Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye; and Mark Strand’s Mr. and Mrs. Baby and Other Stories.

ROLAND KELTS You and I once discussed how difficult it is to be an individual in Japan, how lonely.

HARUKI MURAKAMI It’s still very difficult, but things have changed drastically in Japan over the last ten years. You know, when I was young, we were supposed to join a company, join the office or the academy. It was a very tight society. You had to belong to someplace. I didn’t want to do that, so I became independent as soon as I left college. And it was lonely.

But not these days. People graduate and immediately become freelancers. There’s a good and bad side, but I look at the good side. It’s a chance to be free.

RK Do people need to look to America today-—or can they stay at home?

HM These days, young Japanese are also looking to Asia and Europe. America isn’t the only one any more. When I was in my teens in the sixties, America was so big—everything was shiny and bright. When I was fifteen years old, I went to see Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers, in Kobe. That was my first encounter with jazz; I was so impressed. Those were very good days for American culture.

RK So other people in Japan were attracted to American culture then?

HM It was overwhelming! No one could stop it. I think before 1962 or 1963, no one in Japan knew what a grapefruit was. The other day I was reading an old translation of American fiction and there was a footnote explaining what one is. And there was no pizza then, no hamburger. When I was at university, around 1970, McDonald’s came to Japan and we went to try what kind of thing a hamburger is.

RK Were those positive experiences?

HM Of course. We are not French. They were very exciting experiences for us. I remember going to see Stanley Kubrick’s 2001 in 1970. That was quite an experience. I think that’s the peak of American culture.

RK But the image has changed, hasn’t it?

HM Well, in those days, America had two sides: the strong side, and the youthful, countercultural side. We criticized the Vietnam war, but we were still listening to Jimi Hendrix and the Doors. America had a sense of balance in those days that we admired.

RK And now?

HM I feel like that balance was lost somehow. I think most Japanese feel that way. You know, people don’t drink Coca-Cola anymore. In fact, the most popular drink in Japan these days is ocha [traditional Japanese barley tea].

RK Are Japanese taking more pride in Japan?

HM I don’t know if the Japanese are proud of Japan, but they don’t admire American imports. Most American rock is boring these days—too commercial, too dull. Just like Hollywood movies. Young people are starting to get interested in Japanese films, just like they’re listening to J-Pop [Japanese pop music].

Personally, I think most of J-Pop is garbage, just like anime. But some of it is good, and if it’s good, I feel closer to it because it’s Japanese.

RK What about American fiction?

HM Oh, it’s popular now. It’s strange. I think American writers have been very good over the past twenty years or so. When I was in my twenties, we had two camps—Barthelme and other postmodern writers; and the realists, like Updike. But starting in the eighties, we had a third stream—writers like John Irving, Raymond Carver, Tim O’Brien. When I read Carver’s stories, I was stunned.

RK What stunned you about Carver?

HM Nobody wrote stories like those. They went beyond common sense. He always chose a simple vocabulary. He wrote straightforward stories, with a sense of humor, a crispness, and an unpredictable story line and very bleak endings. His stories are about everyday life. I learned something from Raymond Carver about writing short stories.

RK What do you think you learned from Carver?

HM What he was saying with his short stories is that you have to be intellectual when you write, but the subject matter doesn’t have to be intellectual.

RK What about the other authors you’ve translated. Irving, for example. What did you learn from him?

HM I learned something from John Irving about writing novels—that kind of powerful storytelling voice. When I say I learn something from translation, it’s not a small, practical thing. It’s a big thing. The author’s breathing, his perspective, his sensations. I can feel those things when I translate.

You know, in the old days, people would trace the writing in good books. Japanese people used to trace the pages of The Tale of Genji, for example. You can learn so many things from tracing. It’s just like putting your feet into other people’s shoes. Translation is the same thing.

RK Do you learn from other translators, too? Do you read Shibata’s translations?

HM Oh yes. I love his translations. But we have different tastes. Paul Auster, Steve Erickson, Stuart Dybek, and Steven Millhauser—they’re great writers, but I wouldn’t translate their work. Which is good, because we have no conflicts.

I think Shibata likes more balanced fiction. It’s not easy to explain. But whenever I read his translations, I find a very well-balanced literary world—symmetrical. Auster is a good example: It’s like the music of J. S. Bach. It’s kind of mathematical. You could say the same thing about Erickson or Millhauser. Those are wonderful worlds they’re producing, but they are very rational. Sometimes things get crazy and chaotic, but seen from a distance, everything is rational and even stoic. I’m saying that in a complimentary way.

But with Carver and O’Brien, things get irrational sometimes. I guess I feel more comfortable when things are messy. I prefer that kind of world. But you know, when I translated The Nuclear Age by Tim O’Brien, every American I met said that’s his worst book. But I just loved it. I told O’Brien when I met him, and he was so suspicious. He said: “You did? You really did?”

RK As if you were the only one.

HM That’s right. But in Japan, many readers loved it. Sometimes I think American readers are missing something.

RK With Nuclear Age, what specifically do you think Americans missed?

HM You know, it’s not a profitable book. It doesn’t have balance. It’s very rambling, and it’s incomplete. But still, it has something very important to tell you. People don’t appreciate those incomplete books, I guess. But I could feel the heat in that book.

RK Do you think Americans are more conservative in their expectations?

HM I think American readers are sometimes too much, you know, New York Times Book Review.

RK Are there any younger authors you’re interested in translating?

HM You know, after those writers I mentioned—Carver, O’Brien, Irving —I haven’t found a good new book I want to translate. I’m wondering if it’s because I got old. I’m not a professional translator; I’m a writer, and I want to learn something from the work of translation. When you reach a certain point, it gets harder to learn from reading other writers’ work. I’d rather learn from the classics these days, books like The Great Gatsby or The Catcher in the Rye.

RK When you first talked to me about translating The Catcher in the Rye, one of the things you mentioned was a tension in the book, between an open world—democratic and free and pluralistic—and a closed world, controlled and manipulated and oppressive.

HM Yes. And these days, the closed worlds are getting stronger in many places. You have fundamentalists, cults, and militaries. But you can’t destroy closed worlds with arms. Their systems will still survive. For example, you could kill all the al Qaeda soldiers, but the closed system itself, the ideas, would survive. They’ll just move it somewhere else.

The best thing you can do is just show and tell: Show the good side of the open world. It takes a long time, but in the long term, those open circuits of the open world will outlast the closed worlds.

RK Why do you think closed worlds are acquiring strength now?

HM That’s very easy to answer. The world is very chaotic today. You have to think about so many things—your stock options, the it industry, which computer you should buy. You have fifty-four channels on dtv. You can know anything you want on the Internet. It’s all very complicated, and you can get lost.

But if you enter a small, closed world, you don’t have to think about anything. The guru or dictator will tell you what to do and think. It’s so simple and easy and seductive. Even to intelligent people, like the ones who entered Aum Shinrikyo [the cult that poisoned the Tokyo subways in 1995]. But it’s a trick. Once you enter the closed world, you can’t escape. The door is closed.

RK You’ve said elsewhere that the tension between those two worlds was part of what drove you to translate The Catcher in the Rye.

HM That’s right. The last time I read that book was in high school, thirty-nine years ago. I almost forgot the actual story, but when I translated it, I realized that it’s really about a disease of the mind, a kind of diseased American psyche. America’s social maladies. It’s a very short odyssey through the mind of the author; but it’s not just about him.

You know, his book has inspired some assassins—the man who killed John Lennon, and the man who tried to kill Ronald Reagan. His book has some connection to the darkness in people’s minds, and that’s very important. It’s a great book, but Salinger was very close to that closed world in himself. He’s in the open world as a novelist, of course, but I think his mind was getting closer to the closed world, and the book is ultimately ambivalent about the two worlds. Most people, in Japan and elsewhere, think the book is about a child against society. But it’s not that simple. He’s really judging the very values of life, weighing them in his right and left hands. And his judgment changes all the time. That’s what makes the book so thrilling.

RK After translating the novel, do you still feel that way?

HM Yes. Salinger was going down to the bottom of a dark obsession.

RK Like a well?

HM Yes. When I translated that book, I had to go down into the darkness with him. And sometimes it was kind of suffocating. But now I think it was a good experience for me.

RK What about translating Gatsby? What did you learn from Fitzgerald?

HM You know, I waited for twenty-five years to do this. In the early eighties. Hemingway was so popular in Japan, but very few people read Fitzgerald. I thought it wasn’t fair. I just wanted to translate this book, but I felt I wasn’t qualified yet to do it.

RK How do you feel about the book today?

HM Before I started translating it, I had felt that The Great Gatsby was a perfect novel. As I worked on it line by line, though, I began to feel that the magic of this novel lay in fact in its imperfection: long sentences without much consistency, certain excesses in setting, occasional lack of consistency in the way characters conduct themselves. The beauty this novel possesses is supported by the accumulation of all these imperfections. I might go so far as to say that it is a special kind of beauty which could only have been expressed by being imperfect. This is probably something I would never have realized if I hadn’t actually translated it into Japanese.

RK A few years ago, you compared your decision to return to Japan in 1995—after the Kobe earthquake and the Tokyo subway poisonings—to Fitzgerald’s decision to return to the U.S. from Paris in 1930.

HM I think Japan’s bubble economy can be compared to the 1920s in America. In that sense I believe that Japan’s “lost decade”—from 1995 to 2005—was a crucial period for the country. We have yet to see what significance the period had for us, but I personally feel that in that decade I did my best as a Japanese novelist. My great theme during those ten years—and probably our theme—was to lay the groundwork for a way to coexist with everyday chaos. Now it’s time to see how good I was—to put my attempt to the test.

Published on April 03, 2014 03:38

April 1, 2014

Toronto & silence

I spend most of my time in cities – big ones. Mostly New York and Tokyo, the most populous in their respective countries, but also Los Angeles, San Francisco and Boston, where my parents have a home. I have visited cities throughout Europe and Asia, and in Australia and South Africa. I have lived in London, San Francisco and Anchorage, Alaska.

In the 21st century, most cities have several common elements: taxi and public transit systems, vast and anonymous airports, traffic jams, tall buildings, hotels, tony restaurants and cheap eateries. I often tell friends that there is less culture shock to be had in flying between megalopolises like Tokyo and New York, London, Singapore or Shanghai, then there is in driving from any of those cities several hundred miles into rural environs.

My life didn’t start with cities. Though I was born in one, I was raised in small towns in upstate New York and New England. When I first lived in Japan as a six year-old, I stayed with my grandparents in Iwate, on the outskirts of the relatively small northern city of Morioka. My childhood memories are of countryside exploits – catching insects in summer fields and yards, ice-skating on ponds and rivers, fishing still lakes, hearing animals scurry beneath porches at night, June bugs and moths fluttering into screen doors, crickets, loons, and silence.

Earlier this year, I was invited to Toronto, Canada to give a weeklong series of lectures and readings at The Japan Foundation and York University. When I departed Tokyo, the weather had been flirting with an increasingly milder dampness, signaling winter’s retreat. But Toronto was in the deep freeze, as was much of the North American East Coast. As soon as I hit my hotel room, my wardrobe went from sweaters to layers of long underwear beneath sweaters, scarves, hats and gloves, and a much heavier overcoat.

Toronto is Canada’s most populous city, and it’s growing fast. As I was told several times by residents – Toronto has more condominiums in development than New York, Chicago and Los Angeles combined. Looking south toward Lake Ontario, you can see the scaffold hulks puncturing an otherwise low-slung skyline. They look self-important and vulgar, like exclamation points in a haiku poem.

Toronto’s residents are multi-ethnic and, superficially at least, placid. Walking the streets, I felt at ease even as I sidestepped patches of ice and snow, burrowing forward in a headlong crouch into frigid winds. (When I noticed that some of the locals – called ‘Torontonians,” I learned – were turning around to walk backward into the gusts, I quickly copied them.) People’s faces bore the calm, unhurried expressions I’m more accustomed to in warmer climes. The city’s café culture easily rivals that of San Francisco, for example, filled at midday with relaxed, slightly rumpled bohemians and laptop noodlers, but in temperatures a good 20C or more colder.

Compared with its equally winter-plagued US neighbors down the coast, Boston and New York, whose insistent competitive airs and status-conscious playmaking can make daily grinds feel like grudge matches, Toronto seemed downright civilized. Brutally cold, yes, but not coldly brutal.

But Toronto has its internal strains. Its now-notorious crack-smoking mayor, Rob Ford, whose Falstaffian outbursts and misdeeds have garnered international infamy, is supported by suburban enclaves to the north, many of whom are immigrants and feel left out of downtown’s burgeoning wealth and perceived bohemian intellectualism (yet another paradox of our benighted times). Ford promised them lower taxes and speaks their ‘language’ with his unapologetically uneducated frat-boy discourse; they prefer his pragmatism and populism, whatever his personal faults, or perhaps because of them. He’s like us.

You go to another city, read its magazines and newspapers, and become briefly embroiled in its local politics. Then you leave.

After my first three talks in Toronto, my good friend, Ted Goossen, translator of Japanese literature and professor at York University, drove me north to his country home in Hockley Valley. It was another blustery morning; I stepped in and out of the lobby several times awaiting his arrival. But the drive was liberating. In an hour or so the road expanded on either side into broad snow-covered plains and sloping hills, trees that tilted gently in the wind. Ted pointed out old lodges and diners along the way. We stopped at one for a burger and a gravy pork pot pie.

We arrived at the house, an elegant blue two-story colonial. Ted and I grabbed kindling, paper and then logs of wood to fire up the woodstove in the basement. We lit another in the fireplace and settled in for an afternoon of reading. The sunlight reflecting against the snow cast a lucid white glow. It was so easy to read.

It was so easy to read. It was quiet, aside from the whip-snap of the fire, and the wind, but that is not noise. That is an adjunct to quiet, its natural partner. I started reading one of my manuscripts, then I switched to James Salter’s latest novel. The writing in both works felt connected to me in ways I haven’t felt for a long time. I read in Tokyo, New York, Boston, and on airplanes, of course. But I don’t often feel that the writing is speaking to me.

Later in the afternoon, Ted said we should go for a walk. My city shoes were insufficient. He handed me some bent rubber boots, big gloves, and a woolen coat that looked like several blankets sewn together.

We trudged through snow till we hit the main road, which was plowed smooth. The sun on the snow was magnificent – holy light. Trees sawed against one another, making an aching cello moan. We saw an eagle. The wind bit so fierce we got chapped red cheeks and feared worse.

We turned back after ten minutes. When we got to Ted’s house, we poured cups of sake. We smiled and sipped. Just ten minutes in that world felt like a reunion with quiet.

Published on April 01, 2014 08:43

March 27, 2014

Anime Japan 2014

The Tokyo International Anime Fair (TAF) and the Anime Contents Expo (ACE) finally reunited this past weekend in Odaiba. It was called Anime Japan 2014, and it worked.

Published on March 27, 2014 07:00

March 21, 2014

Fukushima and distrust

Don’t blame it all on the tsunami

The fallout from the Fukushima disaster is more than a matter of dealing with the results of the devastation caused by the tsunami, the explosion in reactor number 4 and the resulting meltdown and radioactive contamination. Amid the widespread destruction and disruption to life in the affected areas, the need to maintain economic viability has resulted in, among other emergency measures,

In 2011, immediately after the disaster, Prime Minister Naoto Kan was quoted as saying that "Japan was facing the possibility of collapse." This was perhaps one of the more honest assessments at the time, showing how the government really viewed the tsunami and its aftermath. On the evening of that first day, he declared a nuclear emergency and ordered the evacuation of all people within three kilometers of the power station. Then came the denials, with government spokesman Yukio Edano issuing such uncompromisingly positive statements as: "There is no radiation leak, nor will there be a leak." Contributing to the climate of confusion, the Tokyo Electric Power Company (TEPCO) put a ban on employees speaking on the matter in public. What did they all have to hide? It seems clear that mismanagement, bad practice and cover-ups of a series of problems within the plant made some sort of disaster inevitable. Nature only hastened its arrival. A poll taken in May of that year showed that 80% of the Japanese people did not believe what the government was telling them about the crisis.

In 2011, immediately after the disaster, Prime Minister Naoto Kan was quoted as saying that "Japan was facing the possibility of collapse." This was perhaps one of the more honest assessments at the time, showing how the government really viewed the tsunami and its aftermath. On the evening of that first day, he declared a nuclear emergency and ordered the evacuation of all people within three kilometers of the power station. Then came the denials, with government spokesman Yukio Edano issuing such uncompromisingly positive statements as: "There is no radiation leak, nor will there be a leak." Contributing to the climate of confusion, the Tokyo Electric Power Company (TEPCO) put a ban on employees speaking on the matter in public. What did they all have to hide? It seems clear that mismanagement, bad practice and cover-ups of a series of problems within the plant made some sort of disaster inevitable. Nature only hastened its arrival. A poll taken in May of that year showed that 80% of the Japanese people did not believe what the government was telling them about the crisis.A healthy tourism industry

Jump to 2014 and the devastation within the 25 mile exclusion limit around the plant is set to become a new tourist attraction, despite dangerous radiation levels. Plans for a new village to be built on the edge of the exclusion zone include specially constructed hotels that will protect guests from higher than normal radiation that may persist in some outlying areas. The village will create job opportunities for residents of the destroyed town of Fukushima, many of whom are still unable to return to their old homes: it may take up to 30 years to completely decontaminate the area and decommission the nuclear reactors. The hotels, museum and souvenir shops are seen as a vital aid to supporting the local population and restoring the economy. Meanwhile, tourists will wear protective suits and respirators.

The idea for the tourism plan came from similar disaster sites such as Hiroshima, Nagasaki, New York’s Ground Zero and the Killing Fields of Cambodia, where the response has been not so much one of ghoulish ‘dark tourism’ as the provision of a place where people can mourn the victims and learn from the disaster. Such a significant event in the country’s history has inevitably ingrained itself into the minds of any tourist traveling to Japan, where the native history and culture is such a powerful draw. The good news is that most of Japan’s popular tourism areas were either unaffected by the disaster or have recovered from it. There is no radiation hazard outside the exclusion zone around Fukushima, and the US government lifted its travel alert back in April, 2012.

The latest tourism statistics for Japan give a healthy picture of increasing numbers arriving from most parts of the world, with the year on year figure for North America showing a rise of 14.8%. This is a country full of beautiful landscapes and a fascinating culture that mixes a reverence for its ancient traditions and long history with a love of modern cutting edge technological innovation. For any visitor, Japan is a constant and vibrant assault on the senses. An ocean cruise is one of the best ways to experience Japan in all its variety, from Hokkaido, the most northerly island – itself an island of contrasts, with its lavender fields and cherry blossom in the spring, and the snow clad volcanic ski slopes of Niseko Mountain in the winter - to the ultra modern cities of Tokyo and Osaka, and the rugged coastline and traditional gardens of Kyushu and Kagoshima on Kumamoto island in the far south of the archipelago.

On the front line

In 2012 the government declared the mass evacuation of Fukushimaa success, and applauded the workers in the plant for averting catastrophe. Recent concerns that Fukushima has not seen the last of the tsunami’s destructive wake - namely the risk of long term effects of radiation on those in the immediate vicinity of the explosion – have been only partially allayed by the authorities’ assurances that so far there have been no deaths. Naturally, the whispers about conspiracy and cover-up have grown louder, fueled by the results of testing more than 130,000 of Fukushima’s children, more than 40% of whom have shown early signs of developing thyroid cancer. Most people were evacuated within a few days of the disaster, but this may have been too late for those living near the nuclear power station, and many living within the area that forms the current exclusion zone were not evacuated until six weeks later.

In December 2012, the United Nations Special Rapporteur on the right to health, Anand Grover, published a report that accused Japan of adopting ‘overly optimistic views of radiation risks’ and that it had conducted only limited heath checks on the population in the contaminated area; also that it ‘hasn’t done enough to protect the health of residents and workers.’ The Japanese government countered this by describing the complications of government guidelines and their application to workers on short-term contracts or employed by sub-contractors. However, Human Rights Watch and Greenpeace have leveled similar charges at the Japanese government, adding that regular and consistently accurate information was not being given to the people. The government has seemed more concerned with erecting a shield against economic damage and legal liability by underplaying the magnitude of the likely long term effects.

The government and TEPCO have also been quick to counter accusations that cooling water still being used on the destroyed reactors is getting into the ocean. A report published in the journal Science in 2012 claimed that 40% of fish caught off the Japanese north east were contaminated with high levels of radioactive cesium. Again, the response was inconsistent. The federal fisheries ministry did not deny that cesium had been released into the ocean, but were quick to offer assurances that it was sinking into the seabed and there was no danger of it entering the food chain; however, TEPCO claimed that no contaminated water had ever been leaked.

While it is clear that the government is doing everything it can to recover from the disaster and lessen its continuing effects on the environment, public heath and the economy, with a great deal of success - and it is true that there is no danger to travelers - a reluctance to release negative information, and inconsistencies in the information that is released, only creates distrust among the population.

Published on March 21, 2014 02:52

March 20, 2014

Katana collectors in the USA

The Japanese sword is unique in the world for its creation, durability and aesthetics. There is no sharper sword in existence, but they are not simply weapons: their detail and craftsmanship also make them works of art. While the sword is a significant cultural icon in Japan, interest in it is also alive and well in America.

Each year hundreds of people travel to America’s main Japanese sword shows in Chicago, San Francisco and Tampa. This past year the Chicago show, known as Midwest Token Kai (“Sword Group” or “Sword Club”) was put on by Mark Jones and Marc Porpora. Roughly 70 vendors were there selling swords, sword fittings, and various pieces of Japanese artwork.

Japanese swords came to America after World War II as spoils of war. Many swords were eventually returned to Japan, but an American interest in Japanese blades had started. Looking over the crowds at Token Kai, less than 10 percent of the vendors or guests were Japanese or of Japanese descent. Many people there were interested in other forms of Japanese culture, from the language to movies. A past that involved war has moved aside to an appreciation for the Japanese swords themselves.

Japanese swords came to America after World War II as spoils of war. Many swords were eventually returned to Japan, but an American interest in Japanese blades had started. Looking over the crowds at Token Kai, less than 10 percent of the vendors or guests were Japanese or of Japanese descent. Many people there were interested in other forms of Japanese culture, from the language to movies. A past that involved war has moved aside to an appreciation for the Japanese swords themselves.Many people who aren’t interested in Japanese swords view shows like Token Kai as being about weapons, but Porpora said that couldn’t be further from the truth. “We think of them [the swords] as art,” he said. “Other people think of them as weapons.” Some swordmakers in Japan have reached international fame, so buying a sword made by Muramasa would be akin to, say, buying a Rembrandt.

Besides the artistic value, there is historical value. Porpora, for instance, owns a blade that was made in Japan in 1275. Token Kai had swords from the Heian Period all the way up to contemporary blades.

When speaking to different people at the show about how they first got interested in Japanese swords, there were two predominant explanations. Nearly everyone had started out in an interest in martial arts or an interest in Japanese culture. These things eventually led to an interest in the swords.

Mark Jones, who put on the show with Porpora, said that he had inherited a Japanese sword through his family. This led to learning more about Japanese swords in general, which in turn led to a fascination with them. Fred Weissberg, who has led the sword show in San Francisco for 20 years, was also in attendance, and listed such things as an interest in samurai movies or Japanese culture as a pathway to Japanese swords. For his own story, he started studying judo in high school, which led to an interest in Japanese culture, which led to studying the language.

Mike Yamasaki, an expert on Japanese swords who trained in Japan under Tanobe-sensei, the chief research judge of the Japanese Sword Museum in Tokyo, said he has loved swords since he was ten. He’s done consulting work on Japanese swords for the History Channel, A&E, and Travel Channel. Looking over the vendor’s room after giving a lecture on how to spot fakes, he remarked, “Rich people, poor people, people from all walks of life become friends over swords. Culture to me is something that has lasted, and from culture we have roots, and from roots we have foundation. We do what we do because we love it. I do more of what I do because I want young people to learn about Japanese swords."

Published on March 20, 2014 02:28

March 17, 2014

On Hayao Miyazaki & Haruki Murakami for Japan Spotlight

Published on March 17, 2014 23:44

March 13, 2014

On the "King of Kawaii," Sebastian Masuda, in NYC, for my Japan Times column

Masuda’s mission to take Harajuku art global

BY ROLAND KELTS

New York is not a city one automatically associates with the Japanese concept of kawaii — lovably, irresistibly, dependably cute. But if Sebastian Masuda, the so-called “king of kawaii,” has his way, the mean streets of “Goodfellas” may one day emanate a candy-colored glow.

Or at least his street will. Best known for founding the iconic Harajuku fashion shop-cum-global brand 6%Dokidoki in 1995, Masuda wears many hats, both career-wise and atop his head. Before becoming a fashion guru, he was an actor in Tokyo’s avant-garde theater scene, which is where he picked up the Western moniker for his persona, “Sebastian” (he keeps his Japanese birth name unpublished). In 2009, he led a tour to promote kawaii fashion in cities across Europe and the United States, hosting workshops, seminars and events to explain what he calls its “uniquely Japanese aesthetic appeal.” And since 2011, he has been the artistic and conceptual director for global pop star Kyary Pamyu Pamyu, helping create the mega-hit YouTube video for her single “Ponponpon” (nearly 62 million views as I write).

Now he is debuting as an artist — albeit one who dresses like a diminutive Willy Wonka and sports an array of furry multicolored top hats. His first-ever solo show, “Colorful Rebellion — Seventh Nightmare,” opened at the end of February at Kianga Ellis Projects gallery in Chelsea, the epicenter of Manhattan’s art world, and runs through March 29. When we met last week in the gallery’s reception space, Masuda underlined his current commitment to being an artist first. (His hat was a modest light gray, but still furry.)

“My goal now is to expand Harajuku appeal into the global art market,” he said. “Not just as fashion, but as a conceptual art form. And if that means I have to move to New York to make it happen, I will.”

“Colorful Rebellion” features a homey white bed positioned sideways in a single soft-lit room, whose walls and ceiling are festooned with luridly bright stuffed animal toys, feathers and other fluffy things. An enormous teddy bear or cat (I wasn’t sure which) with one eye missing and covered in a patchwork of colors sits on the floor, propped up against the foot of the bed. An assortment of old children’s storybooks is piled beside the pillow.

I was treated to the performance component of the exhibition, in which a Japanese actress with dyed auburn hair enters the room wearing a wispy nightgown. Masuda crouched next to me, DJing via his MacBook Air. A series of melancholic old torch songs, recorded from scratchy vinyl, accompany the actress as she sweeps through the room, pausing to look longingly at the walls and ceiling or to run her fingers through her hair. She takes her position on the bed, leafing through the books, stretching out and disrobing beneath the sheets. Eventually she rises again, clothed and looking refreshed, petting the single-eyed stuffed creature before she exits.

The mood is a mixture of forlorn loneliness and childlike desire, and Masuda explained afterward that it represents his artistic working process — with the colorless white bed signaling his own difficulties in rising from sleep to engage in the creative act, and the multicolored toy-story environs of the kawaii world he wishes to inhabit.

“Kawaii is not just ‘cute,’ ” he said, dismissing the commonly used English translation. “The meaning of cute is just superficial, about the appearance of surfaces. I would say its deeper meaning is more about the process of personality, about personal becoming and transformation. I spend so much time and work so hard on my colorless bed trying to create a kawaii world and bring it into being. It’s a struggle, and this exhibition is meant to draw the curtain back and show what’s behind the scenes of kawaii.”

One of the questions I’m often asked about kawaii at readings and lectures is: Why Japan? What is it in Japanese culture that produces a world of cute so intense and, for some at least, enticing that they want to possess and embody it in their clothing, cosplay or other forms of consumption?

“Maybe Japanese people are more depressed,” Masuda told me, “and so they needed the kawaii concept more. The colors of kawaii represent the power and joys of youth. They make people happier. You know, I created (works within) kawaii culture before the (March 11, 2011) disasters, but the interest in it really increased in Japan after they happened.”

Beyond Japan, Masuda counts pop stars Nicki Minaj, Katie Perry and “Harajuku Girls” singer Gwen Stefani among fans of his work. And he’s keenly aware that he wouldn’t be the first contemporary Japanese artist to use kawaii as a root concept and base himself in New York. “Takashi Murakami,” Masuda said, his eyes lighting up. “Yes, he is like a senpai (mentor) to me. He came here and found a way to spread his work to the world.”

Roland Kelts is the author of “Japanamerica: How Japanese Pop Culture has Invaded the U.S.” He is a visiting scholar at Keio University in Tokyo.

BY ROLAND KELTS

New York is not a city one automatically associates with the Japanese concept of kawaii — lovably, irresistibly, dependably cute. But if Sebastian Masuda, the so-called “king of kawaii,” has his way, the mean streets of “Goodfellas” may one day emanate a candy-colored glow.

Or at least his street will. Best known for founding the iconic Harajuku fashion shop-cum-global brand 6%Dokidoki in 1995, Masuda wears many hats, both career-wise and atop his head. Before becoming a fashion guru, he was an actor in Tokyo’s avant-garde theater scene, which is where he picked up the Western moniker for his persona, “Sebastian” (he keeps his Japanese birth name unpublished). In 2009, he led a tour to promote kawaii fashion in cities across Europe and the United States, hosting workshops, seminars and events to explain what he calls its “uniquely Japanese aesthetic appeal.” And since 2011, he has been the artistic and conceptual director for global pop star Kyary Pamyu Pamyu, helping create the mega-hit YouTube video for her single “Ponponpon” (nearly 62 million views as I write).

Now he is debuting as an artist — albeit one who dresses like a diminutive Willy Wonka and sports an array of furry multicolored top hats. His first-ever solo show, “Colorful Rebellion — Seventh Nightmare,” opened at the end of February at Kianga Ellis Projects gallery in Chelsea, the epicenter of Manhattan’s art world, and runs through March 29. When we met last week in the gallery’s reception space, Masuda underlined his current commitment to being an artist first. (His hat was a modest light gray, but still furry.)

“My goal now is to expand Harajuku appeal into the global art market,” he said. “Not just as fashion, but as a conceptual art form. And if that means I have to move to New York to make it happen, I will.”

“Colorful Rebellion” features a homey white bed positioned sideways in a single soft-lit room, whose walls and ceiling are festooned with luridly bright stuffed animal toys, feathers and other fluffy things. An enormous teddy bear or cat (I wasn’t sure which) with one eye missing and covered in a patchwork of colors sits on the floor, propped up against the foot of the bed. An assortment of old children’s storybooks is piled beside the pillow.

I was treated to the performance component of the exhibition, in which a Japanese actress with dyed auburn hair enters the room wearing a wispy nightgown. Masuda crouched next to me, DJing via his MacBook Air. A series of melancholic old torch songs, recorded from scratchy vinyl, accompany the actress as she sweeps through the room, pausing to look longingly at the walls and ceiling or to run her fingers through her hair. She takes her position on the bed, leafing through the books, stretching out and disrobing beneath the sheets. Eventually she rises again, clothed and looking refreshed, petting the single-eyed stuffed creature before she exits.

The mood is a mixture of forlorn loneliness and childlike desire, and Masuda explained afterward that it represents his artistic working process — with the colorless white bed signaling his own difficulties in rising from sleep to engage in the creative act, and the multicolored toy-story environs of the kawaii world he wishes to inhabit.

“Kawaii is not just ‘cute,’ ” he said, dismissing the commonly used English translation. “The meaning of cute is just superficial, about the appearance of surfaces. I would say its deeper meaning is more about the process of personality, about personal becoming and transformation. I spend so much time and work so hard on my colorless bed trying to create a kawaii world and bring it into being. It’s a struggle, and this exhibition is meant to draw the curtain back and show what’s behind the scenes of kawaii.”

One of the questions I’m often asked about kawaii at readings and lectures is: Why Japan? What is it in Japanese culture that produces a world of cute so intense and, for some at least, enticing that they want to possess and embody it in their clothing, cosplay or other forms of consumption?

“Maybe Japanese people are more depressed,” Masuda told me, “and so they needed the kawaii concept more. The colors of kawaii represent the power and joys of youth. They make people happier. You know, I created (works within) kawaii culture before the (March 11, 2011) disasters, but the interest in it really increased in Japan after they happened.”

Beyond Japan, Masuda counts pop stars Nicki Minaj, Katie Perry and “Harajuku Girls” singer Gwen Stefani among fans of his work. And he’s keenly aware that he wouldn’t be the first contemporary Japanese artist to use kawaii as a root concept and base himself in New York. “Takashi Murakami,” Masuda said, his eyes lighting up. “Yes, he is like a senpai (mentor) to me. He came here and found a way to spread his work to the world.”

Roland Kelts is the author of “Japanamerica: How Japanese Pop Culture has Invaded the U.S.” He is a visiting scholar at Keio University in Tokyo.

Published on March 13, 2014 07:50

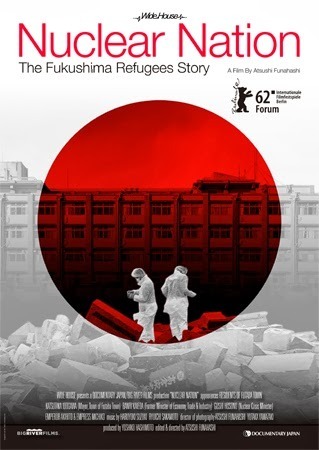

On Fukushima, 3/11 & "Nuclear Nation" for NPR

Published on March 13, 2014 02:33

March 12, 2014

On the 3rd anniversary of Japan's 3/11 disasters for The New Yorker

JAPAN’S RADIOACTIVE NIGHTMARE

by

I first saw “Nuclear Nation,” a haunting documentary about the Fukushima meltdown, at its New York première, late last year. It felt very Japanese to me. Instead of looping the most sensational footage—frothy waves demolishing harbors and main streets, exasperated talking heads—“Nuclear Nation” chronicles, through three seasons, the post-disaster struggles faced by so-called nuclear refugees from the tiny town of Futaba, one of several officially condemned and abandoned communities near the site of the disaster.

The opening sequence of the movie is eerily similar to that of “Akira,” Katsuhiro Otomo’s award-winning animated sci-fi epic from 1988. In both films, a howling wind sounds in the middle distance as the camera focusses on and fetishizes elaborate industrial infrastructure. When the wind suddenly fades to silence, catastrophe ensues: in “Akira,” we see the nuclear cratering of eighties-era Tokyo urban sprawl; in “Nuclear Nation,” it’s the implosion of the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant and the subsequent poisoning of farmlands, fisheries, and rural homes. One is a harrowing fiction echoing Japan’s historical nightmares at Hiroshima and Nagasaki; the other is a somber document of an ongoing and very present horror in and around Fukushima, one whose third anniversary is being marked today in Japan with moments of silence and prayer, official memorials, and televised updates on the most current statistics and predictions.

Approximately eighteen thousand people died or were lost in the wake of the March 11, 2011, earthquake, tsunami, and nuclear meltdown, and tens of thousands remain displaced, unable to return to their homes for now, and perhaps forever. The earthquake and tsunami completely erased entire towns from the Google Maps of northern Japan, but the manmade nuclear crisis has unleashed corrosive fallout, literal and otherwise, that is arguably more persistent and bracing. You might lose your home, livelihood, and loved ones to a natural disaster, but it’s hard to strike back at abstract targets like nature and the gods. When an energy conglomerate, government policy, and corruption cause death and displacement, and disfigure your future, you might get motivated.

“I made this film out of anger and guilt,” Atsushi Funahashi, the director of “Nuclear Nation,” told me last month at a café near Union Square. “The gap between the foreign and domestic media and government statements was huge. When the overseas media was calling Fukushima a ‘meltdown,’ the Japanese government and media waited two months before admitting it.”

Funahashi lived in New York for a decade, from 1997 to 2007, during which he earned a degree from the School of Visual Arts and directed feature films. He had no interest in creating documentaries until he confronted what he calls the “ethical dilemma” of the people of Futaba. “There’s something unfair going on,” he said. “I didn’t know until the disasters that the people who are suffering most from the nuclear meltdown were producing my electricity. The electricity from the Fukushima power plant powered people like me in Tokyo. It puts the rural people at risk for my luxury. And now they have lost their homes over it. It’s not enough to feel sorry for them. I’m on the side of the perpetrators, using electricity that is risking other people’s lives.”

“My friends in Tokyo say, ‘No, it’s not you. It’s the politicians in Tokyo and at the Tokyo Power Company who are wrong,’ ” Funahashi went on. “But I say to them, ‘But we use the electricity and vote for the politicians, don’t we?’ ” The most striking passages in “Nuclear Nation” occur when Funahashi takes his camera along to accompany the refugees on monthly two-hour visits to their contaminated homes. Allotted by the government, and based on Geiger readings, the visits are meant to be opportunities for the refugees to reclaim bits of their blasted lives, pasted together in rushed acts of human pathos.

The refugees wear hazmat gear and board a bus in the early morning. In one scene, a married couple tries to collect DVDs of the “Mad Max” film series for their grandparents, hovering over personal photographs tossed by the earthquake onto a heap on the floor. Their eyes widen as they argue over what should be worth packing and taking with them amid the permanent loss of their domesticity.

In another, a husband, who lost his wife to the tsunami and nuclear aftermath, and his son try to perform a proper burial in their visit. But the coastal winds and slashing rains conspire against their most earnest hopes. Their bouquets are flayed by gusts. They keep checking their watches, knowing they have to return to the buses before the clock ticks down. The very peace they seek for themselves and their lost matron is chewed up and spat out by indifferent natural forces. When the weather becomes too hard to bear even for the audience, the son explodes at his father, who is losing control amid the wind and delicacy and humility of the task. “Hurry up!” the son shouts, as his father fumbles with their disintegrating flowers. When the father tries to collect the petals from the surrounding pools, the son shouts, “No, no! Don’t touch the water! Don’t touch it! It’s poison!”

What passes for the main character in “Nuclear Nation,” and in the plight of the unfinishable story of Fukushima, is Futaba’s former mayor, Katsutaka Idogawa. His story anchors the narrative, and it is brutally banal. Humiliated by Tokyo politicians, disappointing his constituency, his final admission is that he trusted others too much, and will never overcome the loss. Idogawa was ousted earlier this year, replaced by a more Tokyo-friendly mayor, Funahashi told me. If you can’t go home again, then “Nuclear Nation,” he promises, is just the first of many installments about a story of human disaster that may never end.

Roland Kelts is the author of

by

I first saw “Nuclear Nation,” a haunting documentary about the Fukushima meltdown, at its New York première, late last year. It felt very Japanese to me. Instead of looping the most sensational footage—frothy waves demolishing harbors and main streets, exasperated talking heads—“Nuclear Nation” chronicles, through three seasons, the post-disaster struggles faced by so-called nuclear refugees from the tiny town of Futaba, one of several officially condemned and abandoned communities near the site of the disaster.

The opening sequence of the movie is eerily similar to that of “Akira,” Katsuhiro Otomo’s award-winning animated sci-fi epic from 1988. In both films, a howling wind sounds in the middle distance as the camera focusses on and fetishizes elaborate industrial infrastructure. When the wind suddenly fades to silence, catastrophe ensues: in “Akira,” we see the nuclear cratering of eighties-era Tokyo urban sprawl; in “Nuclear Nation,” it’s the implosion of the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant and the subsequent poisoning of farmlands, fisheries, and rural homes. One is a harrowing fiction echoing Japan’s historical nightmares at Hiroshima and Nagasaki; the other is a somber document of an ongoing and very present horror in and around Fukushima, one whose third anniversary is being marked today in Japan with moments of silence and prayer, official memorials, and televised updates on the most current statistics and predictions.

Approximately eighteen thousand people died or were lost in the wake of the March 11, 2011, earthquake, tsunami, and nuclear meltdown, and tens of thousands remain displaced, unable to return to their homes for now, and perhaps forever. The earthquake and tsunami completely erased entire towns from the Google Maps of northern Japan, but the manmade nuclear crisis has unleashed corrosive fallout, literal and otherwise, that is arguably more persistent and bracing. You might lose your home, livelihood, and loved ones to a natural disaster, but it’s hard to strike back at abstract targets like nature and the gods. When an energy conglomerate, government policy, and corruption cause death and displacement, and disfigure your future, you might get motivated.

“I made this film out of anger and guilt,” Atsushi Funahashi, the director of “Nuclear Nation,” told me last month at a café near Union Square. “The gap between the foreign and domestic media and government statements was huge. When the overseas media was calling Fukushima a ‘meltdown,’ the Japanese government and media waited two months before admitting it.”

Funahashi lived in New York for a decade, from 1997 to 2007, during which he earned a degree from the School of Visual Arts and directed feature films. He had no interest in creating documentaries until he confronted what he calls the “ethical dilemma” of the people of Futaba. “There’s something unfair going on,” he said. “I didn’t know until the disasters that the people who are suffering most from the nuclear meltdown were producing my electricity. The electricity from the Fukushima power plant powered people like me in Tokyo. It puts the rural people at risk for my luxury. And now they have lost their homes over it. It’s not enough to feel sorry for them. I’m on the side of the perpetrators, using electricity that is risking other people’s lives.”

“My friends in Tokyo say, ‘No, it’s not you. It’s the politicians in Tokyo and at the Tokyo Power Company who are wrong,’ ” Funahashi went on. “But I say to them, ‘But we use the electricity and vote for the politicians, don’t we?’ ” The most striking passages in “Nuclear Nation” occur when Funahashi takes his camera along to accompany the refugees on monthly two-hour visits to their contaminated homes. Allotted by the government, and based on Geiger readings, the visits are meant to be opportunities for the refugees to reclaim bits of their blasted lives, pasted together in rushed acts of human pathos.

The refugees wear hazmat gear and board a bus in the early morning. In one scene, a married couple tries to collect DVDs of the “Mad Max” film series for their grandparents, hovering over personal photographs tossed by the earthquake onto a heap on the floor. Their eyes widen as they argue over what should be worth packing and taking with them amid the permanent loss of their domesticity.

In another, a husband, who lost his wife to the tsunami and nuclear aftermath, and his son try to perform a proper burial in their visit. But the coastal winds and slashing rains conspire against their most earnest hopes. Their bouquets are flayed by gusts. They keep checking their watches, knowing they have to return to the buses before the clock ticks down. The very peace they seek for themselves and their lost matron is chewed up and spat out by indifferent natural forces. When the weather becomes too hard to bear even for the audience, the son explodes at his father, who is losing control amid the wind and delicacy and humility of the task. “Hurry up!” the son shouts, as his father fumbles with their disintegrating flowers. When the father tries to collect the petals from the surrounding pools, the son shouts, “No, no! Don’t touch the water! Don’t touch it! It’s poison!”

What passes for the main character in “Nuclear Nation,” and in the plight of the unfinishable story of Fukushima, is Futaba’s former mayor, Katsutaka Idogawa. His story anchors the narrative, and it is brutally banal. Humiliated by Tokyo politicians, disappointing his constituency, his final admission is that he trusted others too much, and will never overcome the loss. Idogawa was ousted earlier this year, replaced by a more Tokyo-friendly mayor, Funahashi told me. If you can’t go home again, then “Nuclear Nation,” he promises, is just the first of many installments about a story of human disaster that may never end.

Roland Kelts is the author of

Published on March 12, 2014 07:46