Jeffrey Miller's Blog: Jeffrey Miller Writes, page 4

May 11, 2017

Bureau 39: The Beginning

Many people have asked me how did I come up with the story for my latest novel, Bureau 39. The story of Frank Mitchum chasing down an old Army buddy in Korea while trying to cut-off North Korea’s funding for its WMDs started out as a story about a murder in Itaewon, which was based on an actual event that happened in 2002. The novel, Murder in the Moonlight, which was my first foray into the annual National Novel Writing Month (NaNoWriMo) in 2012, was the story about a woman found murdered in a hotel in Itaewon. The woman, the daughter of a former United States Forces Korea (USFK) general was in Korea visiting friends. When she ends up dead, her father contacts one of his former NCOs, Greg Sanders, who is a defense contractor in Seoul, to find out what happened. Sanders runs into his old nemesis in the CID who is convinced that the woman was murdered by her boyfriend. Later, Sanders finds out that the daughter got caught up in a drug smuggling conspiracy involving members of South Korea’s underworld and a North Korean defector. The closer Sanders gets to finding out who killed the girl, he becomes caught up in a web of deception and murder.

I wasn’t happy with the how I developed the story and shelved it to work on The Panama Affair.

And then in 2014, I heard about a former Army Ranger who was caught trying to smuggle 100 kilograms of methamphetamine into the United States.

The meth was from North Korea.

It was time to look at the story again.

What exactly is the infamous Bureau 39?This is what Wikipedia says:“Room 39 (officially Central Committee Bureau 39 of the Korean Workers’ Party, also referred to as Bureau 39, Division 39, or Office 39) is a secretive North Korean party organization that seeks ways to maintain the foreign currency slush fund for the country’s leaders, initially Kim Il-sung, then, in progression, Kim Jong-il and Kim Jong-un.

The organization is estimated to bring in between $500 million and $1 billion per year or more and may be involved in illegal activities, such as counterfeiting $100 bills (see Superdollar), producing controlled substances (including the synthesis of methamphetamine and the conversion of morphine-containing opium into pure opiates like heroin), and international insurance fraud.

Although the seclusion of the North Korean state makes it difficult to evaluate this kind of information, many claim that Room 39 is critical to Kim Jong-un’s continued power, enabling him to buy political support and help fund North Korea’s nuclear weapons program.

Room 39 is believed to be located inside a ruling Workers’ Party building in Pyongyang, not far from one of the North Korean leader’s residences.”

And, in the immortal words of that endearing radio personality, Paul Harvey, “and now you know the rest of the story.”

The post Bureau 39: The Beginning appeared first on Jeffrey Miller.

Bureau 39: The Beginning

Many people have asked me how did I come up with the story for my latest novel, Bureau 39. The story of Frank Mitchum chasing down an old Army buddy in Korea while trying to cut-off North Korea’s funding for its WMDs started out as a story about a murder in Itaewon, which was based on an actual event that happened in 2002. The novel, Murder in the Moonlight, which was my first foray into the annual National Novel Writing Month (NaNoWriMo) in 2012, was the story about a woman found murdered in a hotel in Itaewon. The woman, the daughter of a former United States Forces Korea (USFK) general was in Korea visiting friends. When she ends up dead, her father contacts one of his former NCOs, Greg Sanders, who is a defense contractor in Seoul, to find out what happened. Sanders runs into his old nemesis in the CID who is convinced that the woman was murdered by her boyfriend. Later, Sanders finds out that the daughter got caught up in a drug smuggling conspiracy involving members of South Korea’s underworld and a North Korean defector. The closer Sanders gets to finding out who killed the girl, he becomes caught up in a web of deception and murder.

Many people have asked me how did I come up with the story for my latest novel, Bureau 39. The story of Frank Mitchum chasing down an old Army buddy in Korea while trying to cut-off North Korea’s funding for its WMDs started out as a story about a murder in Itaewon, which was based on an actual event that happened in 2002. The novel, Murder in the Moonlight, which was my first foray into the annual National Novel Writing Month (NaNoWriMo) in 2012, was the story about a woman found murdered in a hotel in Itaewon. The woman, the daughter of a former United States Forces Korea (USFK) general was in Korea visiting friends. When she ends up dead, her father contacts one of his former NCOs, Greg Sanders, who is a defense contractor in Seoul, to find out what happened. Sanders runs into his old nemesis in the CID who is convinced that the woman was murdered by her boyfriend. Later, Sanders finds out that the daughter got caught up in a drug smuggling conspiracy involving members of South Korea’s underworld and a North Korean defector. The closer Sanders gets to finding out who killed the girl, he becomes caught up in a web of deception and murder.

I wasn’t happy with the how I developed the story and shelved it to work on The Panama Affair.

And then in 2014, I heard about a former Army Ranger who was caught trying to smuggle 100 kilograms of methamphetamine into the United States.

The meth was from North Korea.

It was time to look at the story again.

May 7, 2017

Bureau 39 — An Excerpt

WRAPPED IN LAYERS of threadbare rayon and vinylon, Kim Min-hee shivered on the shore of the frozen river and hoped she wouldn’t have to wait too long. After traveling for almost two days to get there, she had lain low for another day to watch for military patrols, and had been unable to light a fire for fear of being spotted. Hungry and cold, she spent the night huddled under an old blanket she had found tucked between rocks at the edge of the mighty Yalu.

WRAPPED IN LAYERS of threadbare rayon and vinylon, Kim Min-hee shivered on the shore of the frozen river and hoped she wouldn’t have to wait too long. After traveling for almost two days to get there, she had lain low for another day to watch for military patrols, and had been unable to light a fire for fear of being spotted. Hungry and cold, she spent the night huddled under an old blanket she had found tucked between rocks at the edge of the mighty Yalu.

She felt the small package under her clothes. Its weight and shape were both comforting and deadly. If things worked out, she would make contact with a Chinese buyer who would pay her well for the package. Bingdu—methamphetamine or crystal meth, was a valuable commodity, but if she was caught carrying the drugs, she would either be shot on the spot by one of the patrols, or worse, arrested and sent to one of the work camps where she would most assuredly die. The risk was extreme, but definitely worth it if Min-hee wanted to escape to the South.

Getting the drug was simple, since there was a man in her village who made it in his kitchen. He had once been a renowned chemist at a state-run laboratory, but when the country fell on hard times, he and other chemists who found themselves out of work turned to alternative means to support themselves. There were others who made the drug, but Min-hee’s villager was the most reliable. He had lost his wife the winter before, and no longer cared about life. The government threatened to crack down on the production and sale of bingdu, but the kitchen labs prospered, and the thriving black market along the border between North Korea and China was impossible to stop.

Min-hee had heard there was even a factory that was producing the drug on an industrial scale. Supposedly a Chinese businessman had built it and was manufacturing the drug using some of the same chemists who had been producing it in their homes. Min-hee feared it would only be a matter of time before chemists like the one in her village would be put out of work, or executed. The regime liked to keep the people scared, and mandatory attendance of public executions in the village square did that. Either way, if these rumors were true, she would have to come up with another way to fund her passage to the South.

Like many of the people in her village, Min-hee had sampled the drug she was carrying for the Chinese trader. Fellow villagers had told her how, in small quantities, bingdu suppressed the awful hunger they all felt. At first, she wanted nothing to do with it, but when she could no longer endure the gnawing emptiness in her stomach, she relented. The drug also had other supposed medicinal benefits. Some took it for headaches, to treat a common cold, or to seek relief from depression. She heard about soldiers who used it to stay alert when they were on duty or workers who took it to work longer hours in the country’s factories.

Everyone who tried it more than once found it extremely difficult to stop using.

Min-hee was not the only person in her village who sold the drug to Chinese traders. There were others who were willing to take risks, but not everyone was so lucky. There was one woman in her village whose son was arrested and thrown into jail for smuggling the drug into China. When the woman went to try to secure the release of her son, one of the guards told her that if she ever wanted to see her son alive, she had to bring him two grams of the drug. She did, and her son was freed. Another woman was caught and never heard from again.

It never crossed Min-hee’s mind that what she was doing was wrong. When she was younger, she had been mesmerized by her country’s charismatic leader. Once, while serving in the army, he visited her radar station on a mountain. She and the other women in her unit wept when he stopped to talk to them and pose for a photograph. It was one of the happiest days of her life. She believed in her country’s policy the Juche ideology or self-reliance. However, not everyone felt the same way. People grew tired of the food shortages and the empty slogans that told them to grow more mushrooms or annihilate the enemy to the last man. These slogans did not improve their lifestyle or put more food on the table. Soon, she dreamed of a better life.

February 3, 2017

Book Review: Bangkok Belle

Bangkok Belle is not your ordinary, run-of-the-mill hardboiled detective story. Indeed, what makes this novel fascinating and engaging is its exotic location and colorful characters. The author, Ron McMillan, who has knocked around Asia for a couple decades, offers much more than a “travel guide” story by dropping in a steady flow of Asian references, in this case, Bangkok, to showcase his expat expertise. On the contrary, in the grand literary hardboiled detective tradition of Dashiell Hammett and Raymond Chandler, McMillan is brilliant in the way that he uses the setting to propel his story along. Of course, the exotic location of Bangkok doesn’t hurt any, either.

Bangkok Belle is not your ordinary, run-of-the-mill hardboiled detective story. Indeed, what makes this novel fascinating and engaging is its exotic location and colorful characters. The author, Ron McMillan, who has knocked around Asia for a couple decades, offers much more than a “travel guide” story by dropping in a steady flow of Asian references, in this case, Bangkok, to showcase his expat expertise. On the contrary, in the grand literary hardboiled detective tradition of Dashiell Hammett and Raymond Chandler, McMillan is brilliant in the way that he uses the setting to propel his story along. Of course, the exotic location of Bangkok doesn’t hurt any, either.

As a fan of hardboiled detective stories, I enjoyed this one a lot. McMillan is a brilliant writer with a lion’s share of literary tricks to keep readers turning from one page to the next. I especially liked the way he played the two main characters Mason and Dixie off each other throughout the story as well as their attempts to solve a murder while protecting one of their friends who takes part in a beauty pageant in Bangkok.

McMillan delivers another hit with Bangkok Belle. Hammett and Chandler would be proud.

September 18, 2016

National Geographic — December 1979

One of my prized possessions is a 1979 issue of National Geographic that I bought on eBay to remind me of what it was like to come to Korea in 1990.

One of my prized possessions is a 1979 issue of National Geographic that I bought on eBay to remind me of what it was like to come to Korea in 1990.

It was late summer 1990. Iraq had invaded Kuwait, Die Hard 2 and Ghost were two of the summer’s hottest movies, and I had been working at a Del Monte canning factory in Mendota, Illinois since mid-August.

How I ended up at Del Monte, after having taught in Japan just nine months earlier, is not entirely another story, but part of my plan to return to Japan via Malaysia—you know, the shortest distance between two points is not always a straight line.

The day after I interviewed for a teaching position at a new language school opening in Malaysia, I was hired by Del Monte and promptly started working the night shift from six at night until six in the morning. If I were headed back to Asia, I was going to need some funds to tide me over until I left. As it turned out, I got to put some of my college skills to good use: my job was tell trucks where to dump their loads of sweet corn and to keep track how much corn had been delivered and processed. I also relieved the two tractor operators who pushed the ears of corn into the processing facility. Actually, it was one of the best jobs I ever had and I really enjoyed the people I worked with at the facility. Had I not been offered a job in Korea (I’m getting there) I had been offered a full-time job at that plant.

At the same time, one of my friends, who worked at a printing shop in LaSalle, told me that one of her clients was the manager of a Japanese plant which made auto parts. This client had a thirteen-year-old daughter going to Washington Grade School in Peru, Illinois. Problem was, the girl’s language skills were too low for her to do well in school. My friend suggested that because of my Japanese language skills, I would be a good tutor for her. In the end, I ended up teaching the girl, her younger brother, and mother before I left for Korea. I’m getting there!

Around this time, I was informed by the recruiter of the language school I had applied for that I didn’t get the job. Although I had done well on the interview (later, I would see the notes from that interview which included the comments, “He has that All-American look; he will sell well in Asia”), the school wanted more seasoned teachers. However, the recruiter told me that positions at two schools in Seoul were opening all the time.

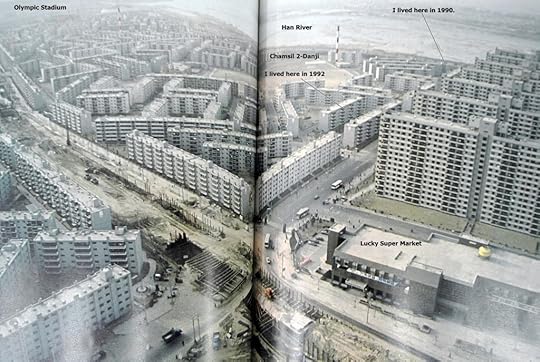

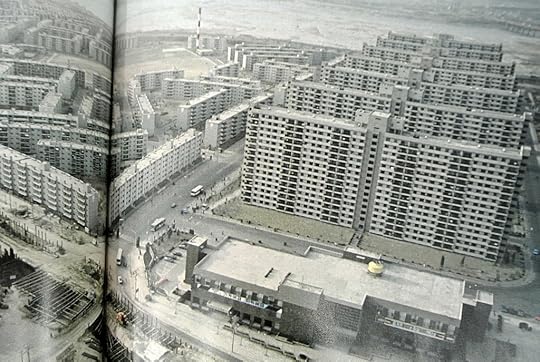

In the beginning, I taught the girl in the afternoon before I went to work at Del Monte. Most of the times, I got to the school early and waited for her in one of the classrooms while she finished her classes. One day, I happened to notice a stack of old National Geographic magazines in a bookcase. I picked a copy and started thumbing through it. Turned out it was one from 1979 that had a story about Seoul, South Korea. It was more of a coming-of-age story about Seoul and how the city had finally risen from the ashes of the Korean War. One photograph in particular of a housing project near Olympic Park stuck out more than the other ones of salarymen drinking and Andre Kim posing with two models. Maybe it was the stark, cold feeling that I got from the photo which showed the Number 2 subway line being built and the muddy tidal flats of the Han River in the distance which made me stare at it longer than other photographs.

Three months later, I would be living in that apartment complex when I started teaching at the ELS school near Kangnam Subway Station.

Had fate intervened that day which made choose that issue over other issues? I would like to think so. Not long after I started teaching at ELS, one of my colleagues and friends, Ken Celmer had that same issue and shared it with me. I still couldn’t get over how I had seen that same issue rightbefore I found out that I had been hired to teach at ELS.

Looking at it today, it’s 1990 all over for me.

That’s when I took the road less traveled again…and once again, it would make all the difference in the world.

August 10, 2016

Book Review: An Unknown Shore

One of the joys of discovering a new author is coming to the table without any expectations of the author’s previous work (if any). It’s all about what’s in front of you now and the literary journey the author will take you on. At the same time, it’s also, “Okay, buddy, I took a chance and bought your book. Now show me what you got and make it worth my while.”

One of the joys of discovering a new author is coming to the table without any expectations of the author’s previous work (if any). It’s all about what’s in front of you now and the literary journey the author will take you on. At the same time, it’s also, “Okay, buddy, I took a chance and bought your book. Now show me what you got and make it worth my while.”

That’s exactly what happened when I bought and started reading Jim Yeazel’s An Unknown Shore. However, it didn’t exactly happen the way I just described. I heard about Yeazel’s book in an interview with him in my hometown newspaper, the News Trib. Turns out that we both are from the same area. That’s all I needed to convince me to buy his book and see what he had to say. You, nothing better than supporting one of the folks back home.

Not a bad decision. I liked this book a lot. It’s a psychological thriller with plenty of twists and turns to keep you riveted from start to finish. It starts with a badly mutilated body found in a forest in a small Minnesotan town that soon has the community turned upside down as local authorities try to find those responsible. Things become more complicated and chilling when more bodies are discovered.

Although the book bogs down a little here and there, especially with some of the back story and the past relationships with some of the characters, Yeazel has got himself a good story here. It handles the genre well and never shows his cards, which keeps you reading to see what’s going to happen next.

August 9, 2016

Book Review: Dear Petrov

Early in Susan Tepper’s brilliant collection of short fiction, Dear Petrov, her unnamed narrator asks, “Dear Petrov. Can you not take in, just out of range, a lady of wistful yearning. Who, by her own submission, adores you out of reach.” And so begins a mesmerizing and poignant spiritual journey into the heart and soul of a woman whose world has been turned upside down by the man she’s enamored with. We’re not sure if she’s waiting for her lover to come home from war or perhaps if he’s ever coming back. However, that’s not important. Although we the reader are not sure who he is that doesn’t make any difference because Petrov represents all the want in this world; he becomes the embodiment of one’s hopes, fears, desires, loneliness, loves, successes, and failures.

Early in Susan Tepper’s brilliant collection of short fiction, Dear Petrov, her unnamed narrator asks, “Dear Petrov. Can you not take in, just out of range, a lady of wistful yearning. Who, by her own submission, adores you out of reach.” And so begins a mesmerizing and poignant spiritual journey into the heart and soul of a woman whose world has been turned upside down by the man she’s enamored with. We’re not sure if she’s waiting for her lover to come home from war or perhaps if he’s ever coming back. However, that’s not important. Although we the reader are not sure who he is that doesn’t make any difference because Petrov represents all the want in this world; he becomes the embodiment of one’s hopes, fears, desires, loneliness, loves, successes, and failures.

The language is rich and evocative. Open up the book and choose any story and you will be moved by Tepper’s use of language and emotions evoked by the imagery. “I have grown my fingers into claws, in order to shimmy up trees and watch for you,” she writes in “Shimmy” which exudes narrator’s deep-rooted longing for Petrov. “All day I watch for you. I hang by my nails dug into tree bark. The forest is summer tangle, while I’m this cawing bird.” This is brilliant writing. We, as the reader, get caught up in the gamut of emotions and imagery from one story to the next.

These are stories to savor and reflect upon over and over again. I haven’t been moved by a collection of stories like these in a very long time. There’s a reason for that. In the end, Dear Petrov speaks for us all.

August 8, 2016

Book Review: Dust

It’s been a long time that a book of poetry moved me as much as Brady Peterson’s Dust did. A lot had to do with the topics, which reminds me of many of the things I like to write about, and the reasons why I write. Reading Dust reminded me of the important role we writers have to document and comment about life around us in an attempt to better understand the world we inhabit. Every single moment we capture through the looking glass tells us something about ourselves and invariably, the world around us.

It’s been a long time that a book of poetry moved me as much as Brady Peterson’s Dust did. A lot had to do with the topics, which reminds me of many of the things I like to write about, and the reasons why I write. Reading Dust reminded me of the important role we writers have to document and comment about life around us in an attempt to better understand the world we inhabit. Every single moment we capture through the looking glass tells us something about ourselves and invariably, the world around us.

And what makes Dust unique is that the author is simply commenting about life in its lowest common denominator. In language that is accessible and visceral, Peterson reveals much about the world around us.

Take for example, “We Once Played” which will resonate strongly for anyone who grew up in the sixties:

“We once played baseball unsupervised/climbed trees, squatted in culverts between rains—played war/using sticks as guns, jumped out of swings.”

But then, the poem does a 360 and might remind one of the Jim Carroll song, “People Who Died:”

“A college friend of my oldest daughter fell from a cliff one afternoon—free climbing/A college friend of mine was killed in Nam when his jeep rolled over on a bomb/Another slammed head-on into a truck while driving home to see if his high school friend was pregnant.”

It is so gut-wrenching when you get to the part. It’s both a reminder of innocence lost and life’s tragic moments that we all must experience.

And as much as I love Ginsberg and “Howl”, I had to chuckle when I read, “Moloch”:

“Vonnegut, who despised City Lights and the beat writers, claimed everyone knew the best minds majored in engineering, not English.”

Ouch.

I also liked his “everyman” approach and commentary. That’s what makes this collection so approachable for readers who might not read a lot of poetry.

On the other hand, for the literary connoisseurs among us, I really enjoyed his references to many of my favorite literary works, especially T.S. Eliot’s “The Love Song of Alfred J. Prufrock” (one of my favorite 20th Century poems hands down; in fact, the book’s title echoes another one of Eliot’s works, “The Burial of the Dead”) as well as William Carlos Williams’ “The Red Wheelbarrow,” John Fowles’s The Collector, and Kurt Vonnegut’s Slaughter House Five.

This is a fine collection of poetry and another gem from Big Table Publishing.

August 7, 2016

Book Review: Blood Soaked Dresses

Gloria Mindock

Paperback: 72 pages

Publisher: Lulu.com (October 11, 2007)

ISBN-10: 1430310340

ISBN-13: 978-1430310341

13.50

If there were one thing that a poet must do when approaching their craft, it would most certainly be never avoiding topics which are too horrific or frightful. To be sure, it is a poet’s responsibility to do just that so we can benefit from one’s analysis and commentary. Whether it’s war, famine, genocide, civil rights, or death, the poets are the ones who shine through the darkness to help us better understand our world and give us all hope.

In Blood Soaked Dresses, Gloria Mindock journeys back in time to the late 1970s and the civil war in El Salvador (1979-1992). She exposes both the atrocities and the horror of this conflict, especially the way that women were affected by it. In hauntingly evocative verse that is brutal and honest, Mindock makes this civil war personal for the readers. These are not just nameless individuals who were killed (one figure places the death toll at over 75,000) or maimed by the conflict; instead, as only a poet can do, she resurrects them and the events of this terrible conflict so we won’t forget. Ultimately, she gives a voice to these tormented souls.

In “El Salvador Bird Watches” she writes about a person waiting to be executed:

“My heart beats so fast into this shallow air.

How can I be heard?

Orange rinds are shoved into my mouth

suffocating me with fragrance. Sadness engulfs me

to know my skin will be stripped and added to the heap.”

Aside from the juxtaposition of the sweet fragrance of orange rinds being stuffed into the person’s mouth to silence the screams, what’s most haunting about this poem is the fact that parakeets flock over the capitol city of San Salvador every day at five in the morning and in the evening and they bear witness to the atrocities happening below.

“The sky is blue, and it’s just another day.”

In that one line, Mindock is brilliant as she compares both the parakeet’s flight and the atrocities below as being a daily occurrence.

And in “Death March” Mindock wonders if the world will remember what happened here and if so, to make sure that those who perished here will never be forgotten:

“Who will be at my funeral?

Who out of this dying world?

A few friends, family, a pair of eyes that loved me

but never told me—

Let us sleep admired.”

These poems are a grim reminder of the evil that exists in our world. These could be poems about other places where hell was in session: Cambodia, Sudan, Rwandan, Syria, and Bosnia. It’s always the poets and the saints who get it right. We should heed their words and listen as if our very own survival depends on it.

August 6, 2016

Book Review: Peek

I’m a big fan of flash fiction or short fiction and I always marvel at how writers are able to take brief, fleeting slice of life moments and bring them to life in this literary form. These are writers who have a very keen eye for detail who capture these snapshots of life and then thrust us, the reader, into the middle of them—writers such as Stuart Dybek, Michael C. Keith, and Robert Vaughn who are masters at their craft. Paul Beckman is one such writer and his collection of short fiction, Peek, is a powerful and poignant journey into the heart of the human psyche—filled with drama, heartbreak, triumph, and failure.

I’m a big fan of flash fiction or short fiction and I always marvel at how writers are able to take brief, fleeting slice of life moments and bring them to life in this literary form. These are writers who have a very keen eye for detail who capture these snapshots of life and then thrust us, the reader, into the middle of them—writers such as Stuart Dybek, Michael C. Keith, and Robert Vaughn who are masters at their craft. Paul Beckman is one such writer and his collection of short fiction, Peek, is a powerful and poignant journey into the heart of the human psyche—filled with drama, heartbreak, triumph, and failure.

As the title suggests, the stories in this collection offer a “peek” into people’s lives and the dramas thrust upon them. Some of the stories in this brilliant collection of short fiction make you shudder; others make you chuckle. Like a doctor with a scalpel, Paul Beckman peels back the veneer of life to reveal the good, the bad, and the ugly. There are so many gems in this collection that it’s hard to choose one or two as favorites. Some of the stories that stood out and resonated strongly with me were “Kosher Soap” about a son and his domineering mother who still has a control on the son after she has died; “Who Knew?” which ties in the overall theme and title of this collection, but more poignantly, the frailties of the human condition when the voyeur becomes the subject of interest for another voyeur; “Wrinkles” which is pure brilliance in how things are not always what they seem; and finally, the continuing saga of Mirksy and Elaine, told in a series of stories which becomes a common thread in this collection, which reminded me of Hemingway’s Nick Adams’ stories.

If you are a fan of short fiction, you are in a treat with this collection. Beckman is a true master at short fiction and I eagerly await his next book.