Annabel Fielding's Blog, page 8

July 3, 2016

Photo-essay: London between the wars

1920s and 1930s continue to provide endless inspiration for writers, re-enactors, swing dancers, vintage lovers and period drama directors alike. It was a difficult, bitter, glittering, glorious, complex time. The city awoke from its post-WW1 slumber and sprung into growth far and wide. New banks and theatres, cinemas (now showing “talkies”!) and gentlemen clubs grew, majestic and marble-clad, every year. The shipyards and ports, on the contrary, grew quieter and quieter – Britannia no longer ruled the waves – while the discontent grew louder and louder. Jazz music bedazzled socialites and factory girls alike. New celebrities scandalized the withering aristocratic families (and sometimes intermarried with them). Society hostesses held maginificent receptions. The Blackshirts held marches in the East End. London was growing taller, faster and slicker. London was moving towards the unspeakable catastrophe.

Here are the photos of some of the best places in London to see the architecture of the inter-war era.

[image error]

Rudolf Steiner House, 35 Park Road.

[image error]

Rudolf Steiner House, 35 Park Road.

[image error]

Brittanic House.

[image error]

Brittanic House.

[image error]

Brittanic House, Moorgate tube.

[image error]

Bank of England

Bank of England.

The post Photo-essay: London between the wars appeared first on History Geek in Town.

June 11, 2016

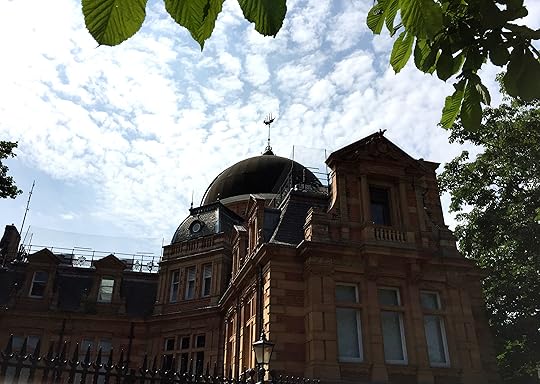

Royal Observatory: of stars and wars

This year has given us a new Star Wars film and renewed our (well, mine) longing for the galaxy far, far away. And, of all London sites, none are better suited for this situation, than Royal Observatory in Greenwich. Each year, it hosts a (free-entry) exhibition of Astronomy Photographers of the Year. There, you can see (as I’ve seen) infinite galaxies, blazing aurorae and impressive, if slightly menacing, shots of the Moon that look distinctively Death Star-y. There are also frozen skyscapes, that made me personally think about unwelcoming planes of Hoth.

Hoth… I mean, Eclipse Totality over Sassendalen.

For some additional experience, there are also breathtaking Planetarium shows and an opportunity to see one of the biggest telescopes in this galaxy (there is also an opportunity to look into it on select winter days). As I am not getting my own Millennium Falcon any time soon, this was really the next best thing.

Sumo Waggle Adventrure by Arild Heitmann

This futuristic flair is not accidental. The Royal Observatory was founded at the time, where the whole Europe buzzed with excitement at the perspective of exploring new worlds (and the New World). And, although Britannia didn’t really rule the waves back then, it didn’t want to be left behind. Long-term voyages of exploration were quite as perilous and uncertain, as the space missions are today, are navigation relied chiefly on celestial bodies. Therefore, in 1675 the Royal Observatory was founded under the patronage of Charles II (yes, the one with Nell Gwynn). The Observatory became the first state-funded scientific institution in Britain – before that, scientific societies tended to be self-funded grassroots groups of enthusiasts.

Royal Observatory now.

There’re plenty of expositions in Royal Observatory now, as well as in other Greenwich museums. They show, how the knowledge of distant stars influenced the life on Earth in myriad ways. We meet a rather diverse cast of characters: Muslim traders, European travellers, Christian missionaries, war heroes and Victorian scientists.

If your thirst for exploration is still unquenched, you can visit Cutty Sark, docked by Greenwich Pier. This well-preserved Victorian clipper has quite an extraordinary biography, which includes voyages to China, mutinies and a world war. If you are travelling with family, going to see Cutty Sark would be especially recommended – it has plenty of activities for kids aboard.

You can go to Greenwich via the DLR (Docklands Light Railway), by train from London Bridge station or, if you want to get in the mood, by boat from Tower Pier, London Bridge Pier or London Eye Pier.

Source:

Liza Picard, Restoration London: Everyday Life in the 1660s (US edition)

(US edition)

The post Royal Observatory: of stars and wars appeared first on History Geek in Town.

May 17, 2016

Ostia: Like Pompeii, but closer (Part 2)

Tonight we return to Ostia Antica. It is one of those places, where you should pay a visit during your weekend break in Rome, even if you have scarce time for anything else. Almost as well-preserved, as the famous victim of Vesuvius, it is not half as widely publicized, so you are unlikely to find yourself in a crowd of tourists.

Last week, we saw Ostia’s legacy as a city of many faiths (from Persian cults to early Christianity) and a melting pot of many ethnicities. We saw its fallen temples and splendid mosaics (that also functioned as ads for the local vendors). All that the Roman Empire had to offer, from Egyptian grain to exotic animals and Sri Lankan sapphires, passed through its famous port. However, this bustling hub had to be supported by unending, ant-like labour of thousands of people.

[image error]

The statue of Fortuna. Judging by the size of a villa she stood in, she bestowed on her worshiper quite a fortune indeed…

It is a natural temptation, of course, to look first at the elegant villas (or, rather, their ruins). There, we’d see remains of spacious rooms and household statues (the statue of Fortuna still stands proudly above the desolation). We’d conjure up the visions of small indoor pools, constructed to cool the rooms down during hot Italian summers; of elegant banquets, that took places in these halls; of bright mosaics, which adorned their walls (and some are still there to be seen). But these were domains of the prosperous few (only prosperous few, in fact, could afford to have their own baths and kitchens). Usually, powerful merchants, like long-gone owners of the villas, tend to dominate historical narratives, as they leave us much more material and written evidence of their lives. However, the miraculous conserving mud of Ostia somewhat evened the situation out and preserved the dwellings of the other 99% of the population just as well. It infused the archaeological site with a kind of eerie, post-mortem egalitarianism.

We can, then, see the many-floored insulae, the ancient condominiums. They never had glass windows – too costly – and simply opened their shutters during the days of oppressive summer heat. Now, however, the whole buildings – windows, rooms and staircases – are wide open to air and sunlight. Bu they still stand, and if you are brave enough, you can try to run up the remaining stairs. I really, really tried to bring myself up to it, but I couldn’t. Sorry.

These staircases weren’t really renowned for their stability even in the city’s heyday. Actually, they were part of the reason, why only the poorest of the poor rented the flats on top floors. The insulae were notoriously prone to conflagrations, and everyone understood, that, in the event of a fire, these staircases could very easily collapse. Therefore, the higher you lived, the higher chance you had to die in flames. A rather dear price to pay for a rent discount.

On the brighter side of things, living in the insulae, you always had an excuse for eating out. And this was an excuse no one can easily counter: you simply had no kitchen. Same was true for the majority of the population, except the villa owners we’ve already visited. As a result, snack bars abounded. Now they stand, surprisingly well-preserved, although half-conquered by the flowers. In fact, on the walls I could still discern drawings of fruits and small dishes – an ancient menu or merely a stimulating ornament?

Another facility, sadly absent from even relatively well-to-do insulae apartments, were bathrooms. Therefore, visits to the public baths were an everyday necessity. Speaking about Roman baths, we tend to imagine something ornamented and luxurious – and, in some cases, it really was so. In Ostia, you can see the remains of a spacious bath complex, targeted at more high-end customers. Marble floors, endless rooms, plenty of space for socializing – everything was there. However, there are also much humbler and smaller Baths of Neptune, used by dock workers in the end of their shifts. Keeping one of the busiest ports in the Empire alive is a sweaty job, after all. Not that the Baths of Neptune were entirely frugal: they contained a gymnasium for recreational sports, for example.

Another place of accessible entertainment, beloved by the coterie of either bathhouse, was the amphitheatre. Hoards of exotic animals from the African shores got transported to this Roman port for the sole purpose of being slaughtered in the combat on this famous arena. Now, the amphitheatre is used for less bloody spectacles. On warm summer evenings, you can attend a classical Greek play there, and sit where the elegant villa owners once sat. The restoration of Ostia amphitheatre was commenced under the patronage of Mussolini; now it continues thanks to the efforts of less controversial sponsors.

You can catch a train to Ostia Antica on Ostiense/Piramide metro station. The commute takes about 20 minutes; after that, it is a matter of a short walk. The site is opened daily.

Sources:

Alberto Angela, The Reach of Rome (UK edition)

The post Ostia: Like Pompeii, but closer (Part 2) appeared first on History Geek in Town.

May 5, 2016

Ostia: Like Pompeii, but closer (Part 1)

Like many travelers on their trips to Rome, I was at first tempted by a day-long excursion to Pompeii. However, at a closer look, I decided to swap the three-hour ride to a twenty-minute one, and visit the remains of Ostia Antica instead.

Ostia Antica doesn’t share Pompeii’s wide publicity – I cannot recall either a magnificent painting or a Hollywood blockbuster, dedicated to it. Among other things, it means, that during the visit you will not have to suffer among the crowds of tourists!

[image error]

Statue of Minerva.

Ostia emerged as a major mercantile town as early as 1st century BC, and soon became virtually a gateway to Rome for everyone arriving in the capital by sea. Despite being subsumed into the empire fairly early, the town fiercely guarded the signs of its independence, however illusionary. For example, above the gates I’d expect to read SPQR, the usual inscription, meaning “Senate and the People of Rome” (as well as the title of Mary Beard’s excellent book). However, instead I saw “SPQO” – that is, almost the same, but with O for the Latin name of the town, which is hailed instead of the imperial capital.

Ostia didn’t have Pompeii’s dubious fortune of being buried (and conserved) under volcanic ash. However, the properties of local mud helped to preserve most of the town for us to see. I could admire the remains of diverse and multicultural civilization, which flourished in Ostica over the centuries. As I’ve said, it was a mercantile city; people from all over the vast empire and far beyond worked and settled here.

A well-preserved cemetery just beyond the erstwhile city walls offers an amazing insight. One can look, for example, at a family mausoleum, including a statue of lars – minor god-protector. To ensure, that the family members will be well-cared about, their relatives would adorn the statue with flowers and offerings.

[image error]

Some ads, set in mosaic.

On the same cemetery, you can see a tomb of a priestess. Her name, Metilia Acte, is still legible on the sarcophagus. She didn’t worship at the altars of conventional Roman gods, the gods of the spreading empire. Instead, she served Cybele, the Great Mother of Phrygia. Her cult was widespread Ostia, where Asian population was very numerous. Ostia accommodated a great variety of faiths. There, you could find worshippers of Isis, the Egyptian goddess, whose cult predated the birth of the Roman Empire by thousands of years. You could meet the followers of Mithras, a tough warrior-god, who came to Rome from Persia (but later became very popular among soldiers, serving on the Scottish border). You could see what is now considered the oldest synagogue in Europe. Small museum, located on site, showcases original statues of various deities – some now entrenched in popular imagination and popular culture, some long-forgotten.

This colourful array of faiths is somewhat mirrored by no less colourful array of ethnicities. If you were to wander Ostia streets in its heyday, you would see people from what is now Germany and Spain, Greece and France, Syria and England, Algeria and Lebanon, Morocco and Tunisia. You’d see goods from all over the world unloaded in the port. Grain from Egypt, the breadbasket of the Empire, would be transported to this Empire’s giant, insatiable capital. Amber from the Baltic will be set into necklaces and adorn the necks of olive-skinned Roman girls. Elephants and tigers from the African shores will be slaughtered during the games, set in Ostia’s great amphitheatre. And, if you are new to the place, but want to buy something – from local fish to sapphires from Sri-Lanka – then these helpful ads, set in black mosaic, will tell you about the available goods and here to find the vendors.

The older post of Ostia, the port of Claudius, where goods-laden ships used to arrive, has been incorporated into the area of Da Vinci airport. Some of its features can be seen among the meadows, streets, parking lots, and office buildings. Here’s to the continuity of history…

At first, I intended to squeeze the wealth of Ostia’s heritage just in one blog post. However, in the end I decided to be merciful to my poor readers and cut it into two smaller articles.

So, to be continued! Next week, we will see visit the Roman baths and learn, why you WOULDN’T want to rent a penthouse in a Roman development…

Sources:

Alberto Angela, The Reach of Rome (UK edition)

The post Ostia: Like Pompeii, but closer (Part 1) appeared first on History Geek in Town.

April 22, 2016

Museum of the History of St. Petersburg

For thousands of travelers, Peter-and-Paul Fortress remains one of the main points of interest in St. Petersburg. However, blinded by the magnificent cathedrals (pictured) and glowing golden spires, they often overlook a little museum, tucked away in the Commandant’s House. So, I decided to remedy

[image error]

St. Peter-and-Paul’s Cathedral

this injustice and visit the Museum of the History of St. Petersburg myself.

The permanent display actually consists of two sections. The first one explores the ancient history of the Neva banks and the earliest decades of the city’s existence. When poets and local guides alike compare it to Venice, they usually mean the beauty of its palaces or proliferation of its theatres. But St. Petersburg shares another, less glamorous aspect with that famous Italian city: both were founded in swampy, marshy, very inhospitable environment. Both, in the end, managed to survive, prosper and develop bustling trade with half a world (…thus getting the funds to pay for the aforesaid palaces, beauty and theatres).

The second section of the permanent exhibition, then, deals with that period of flourishing, which dawned upon the city after Napoleonic Wars. The first rooms are less than inspiring: they constitute an unending hymn to the imperial glory. Troops on parade, palaces on display and a neat timeline on the wall (it includes the abolition of slavery in 1861). Later parts of the exhibition are much better: they allow us, finally, to catch a glimpse of the everyday life of people, who lived beyond the splendid classical buildings (that is, 99% of the population). The room, dedicated to the dawn of railway travel, is especially interesting. I know, I know – trains do not sound particularly exciting (if your name isn’t Sheldon Cooper, in which case I apologize). But this place allows you to sense the sheer extent of significance, which new railways bore in their time. For millenniums, since the first civilizations were born, travel by water was the safest and the fastest way to travel. And, if we are talking about transportation of large goods, it was practically the default way to travel. Access to sea was the factor, which allowed the greatest states in the world to prosper – from Ancient Greece to the already mentioned Venetian Republic. And now, with the onset of the railway, the tables were turned. The game was changed irrevocably – or, at least, it started to change. And nowhere was it felt as keen, as in Russian Empire, of which St. Petersburg was the capital. For the first time in history, these mind-warping expanses of land were made… if not exactly accessible, then, at least, theoretically traversable. (It will still take you at least two weeks to cross the country by train, by the way. Day trips are out of question).

Needless to say, travel became more affordable and more frequent. And, of course, the industries didn’t fail to take advantage of it. On display we can see all kinds of portable sets, sold to keen travelers – little cases for toiletries, writing sets, First Aid kits and even one miniature iron!

[image error]

Some 19th century adverts.

You can also read the original rules for the first train passengers. One, for example, explicitly forbids bringing wine with you (however, no other spirits are mentioned). Another rule prohibits travelling with any kind of dogs, cats, or birds. If any Harry Potter fans are reading this – do you have any theories on how did the Durmstrang students outmaneuver these regulations?…

Later rooms in the exhibition show us some 19th century fashions and examples from contemporary cookbooks. They also allow us to peek into the flats of fin-de-siècle residential development. This is all supremely interesting, and I say it without a trace of irony. However, this listing of achievements (new department stores, new commercial banks, first Women’s University, first Cycling Society…) still suffers from over-glossing. By the end of the exhibition one cannot help but ask: if everything was so flourishing, prosperous and great, then why did this story end as it had?…

Despite these disadvantages, I’d still recommend you to visit the Museum of the History of St. Petersburg, should you find yourself in the vicinity. The museum opens at 11 a.m. and closes at 18 p.m., so you wouldn’t have to set an alarm clock!

The post Museum of the History of St. Petersburg appeared first on History Geek in Town.

April 4, 2016

Mosaic Courtyard: colour and pacifism in St. Petersburg

When we look for things to do in St. Petersburg, we usually get a predictable column of tips. Visits to the Hermitage and strolls along Nevsky Prospect appear there with an almost tedious regularity. I wouldn’t want to dismiss those classical attractions, of course. However, there’re some lesser-known and younger treasures, that don’t get generally included into “highlights” itineraries.

One of those is the Mosaic Courtyard, hidden behind one of the houses of Ulitsa Tchaikovskogo (literally “Tchaikovsky Street”). Famous among many local dwellers, but largely unknown to tourists, this little gem is situated in one of the deep “wells-courtyards”, characteristic for old houses of St. Petersburg. There, you will find walls and pathways blooming with colourful mosaics. You will also be surrounded by sculptures of every sort, from miniature to monumental.

This unexpected explosion of colour seems almost natural; it’s as if the very stones of the city rebelled against the monotony of urban landscape. But, of course, these are actually results of meticulous work, carried out by the students of nearby Minor Academy of Arts.

[image error]

“Glorious are the bringers of truth and beauty!” is a rough translation.

The daring, unparalleled project was conceived by the founder of the Academy, esteemed Russian artist Vladimir Lubenko. In every work he strives to express his bold views, firmly anti-war and anti-prejudice. For example, one of the mosaic compositions here uses traditional font and style of militarist, patriotic, hail-our-heroes images. However, the text itself reads: “Glorious are the bringers of truth and beauty!”…

Lubenko himself was born during WW2 and grew up in a staunchly Communist family. And, while the reality of Communism didn’t meet his (or anyone’s, for that matter) expectations, he still holds true to one of its tenets: a bright idea of international community, free of ethnic squabbles. His idea of a perfect future, as the artist had stated, is one of tolerance and sustainability, where people of different nations and ethnicities will live in harmony with each other and with nature.

Well, this ideal still seems to be lying quite far in the future. However, Lubenko and his students use their own modest powers to bring some more peacefulness and beauty into the world, changing it one courtyard at a time.

Summer is probably the best time to visit the Mosaic Courtyard, when the works are surrounded by blooms and illuminated by sunlight. However, you can also use the visit to bring some colour into grey days of autumn. The place is located behind 2, Ulitsa Tchaikovskogo. Although, I must admit, you’d have to go deeper into the courtyard to see the works; these are not called “wells-courtyards” for nothing!

The post Mosaic Courtyard: colour and pacifism in St. Petersburg appeared first on History Geek in Town.

March 22, 2016

Barbarian treasures in Munich

Bavarian National Museum with its grand façade and vast collections remains one of the most popular Munich attractions. However, many visitors tend to skip seemingly plain collection of Early Medieval artifacts. Instead, they hurry to the upper floors, to more sophisticated centuries: to the gilded furniture and elegant portraits of Bavarian kings.

In doing so, they skip a rare glimpse into mostly forgotten eras. Years after the fall of Rome and before the first Crusade (or, in the case of Britain, before the Norman invasion) are often shrouded in darkness – at least, in the popular imagination. This long era lasted for more, than six centuries – the same amount of time, which separates us from geniuses of the Renaissance. Such a long period couldn’t have been filled with stagnation, hopelessness, general decay and perpetual hunger. And it wasn’t.

…Ivory reliefs, dotted through the exhibition, astound with their sublimity. Clear, intricate and radiant, they were forged in Rome long after the fall of the last emperor. This fact is not as surprising, as it may sound at first. Barbarian kings, who ruled Italy for centuries, weren’t as barbarian as we often think. In fact, they often went to great lengths to protect and spread the traditions of antiquity – including its art. On the more practical level, new aqueducts were built, new public baths opened. Roman Senate was still in existence, dutifully yawning through the sessions; bureaucratic officials continued to fill out the same forms and collect the same salaries. The tradition of public grain distribution, a sort of antique welfare, was abandoned by late emperors, but revived by Gothic rulers.

“Women at the tomb of Christ”, 5th century, Rome. Ivory.

No less impressive, as well as distinctly classical, is the art from Spain. This sunlit land was occupied by Romans for centuries, supplying the Empire with gold and oil. And the Empire itself, in turn, couldn’t help but put down deep roots there. Goths, who invaded Spain later and created a kingdom with a capital in Toledo, couldn’t destroy these traditions overnight – nor did they want too. In fact, they adopted these practices for themselves quite eagerly. The Goths wrote their laws down, just like the Romans did; they used Latin titles; they organized pompous triumphal processions after each major victory. Not that all Goths were overjoyed by this cultural mixing. Many fought fiercely to retain their own identity and, for example, continued to wear long hair and traditional heavy furs. Given the Spanish climate, this is quite an astounding sacrifice in the name of ethnic culture. But, as the years passed, impractical clothing was abandoned and anti-intermarriage law dispelled (not that it hadn’t become a dead letter long before official repealing). Later, the Goths even abandoned their native language, starting to use Latin instead. They forged coins with Roman symbols and slogans.

By the way, do you recall those countless quasi-medieval RPGs, that have monetary system with gold, silver and bronze/copper coins? This system is actually Roman through and through. Later medieval kingdoms had either forged only silver coins, or, as in Saxon England, abandoned their use altogether.

Unfortunately, Saxon England isn’t very well represented in the museum collection. This is understandable, of course. Unlike in the Southern lands, in England the decline of urban life and metropolitan culture was sharp and swift. The mercantile capital of Londinium turned into haunted ruins; classical villas in the countryside crumbled to dust. It took centuries for the Saxons to grow future London into a burgeoning port once more.

Casket of St. Kunigunde, circa 1,000.

But, on the other hand, you can see fabulous artifacts from another Northern civilization: the Vikings. This name inevitably conjures up the images of battles and pillage. However, these seafarers were also prosperous merchants, who created sophisticated trade networks. Their famous ships could be seen as far, as Baghdad. Silk and jewels, ivory and bright dyes flew through these routes into the Northern lands. As a result, local artisans produced such things of unparalleled beauty, as, for example, the Casket of St. Kunigunde. Intricate and mesmerizing, it is a creation of ivory and gild.

Like many other artifacts from the museum collection, the Casket allows us a glimpse into largely forgotten world. It gives us a chance to see vibrant trade now forgotten, mighty rulers long gone, cults now abandoned.

Bavarian National Museum is open every day of the week except Monday from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. It’s located on Prinzregentenstraße 3.

Sources:

P. Daileader, Early Middle Ages

The post Barbarian treasures in Munich appeared first on History Geek in Town.

March 14, 2016

Book Review: Exotic England

Exotic England: The Making of a Curious Nation is a book I would recommend to any English, Anglophile, history buff or traveller, planning a trip to London – or even to people, who are none of the above.

Yasmin Alibhai-Brown analyzes complex relationships between England and various Eastern civilizations over the ages. And, in doing so, she explores – and often explodes – much wider myths. One of those myths, for example, is secluded, monolingual, all-white state of UK before the 20th century.

Reality, as we could expect, is much more complex – and interesting. It resembles an intricately woven pattern, rather than a propaganda poster. From interracial marriages in 18th century London to contemporary Arabic productions of Shakespeare, Yasmin leaves no stone unturned. An Ugandian immigrant herself, she pays tribute to the open, porous, historically multicultural nature of the country, which welcomed her. However, Exotic England is no eulogy: she doesn’t shrink from exploring the horrors of colonialism or consequences of slave trade.

Yasmin also avoids the temptation to paint a period with one brush. She reminds us, that even in the most rigid, imperialist societies there always existed people, who questioned or subverted the order of things. Sometimes, it’s better to let these people speak for themselves, through letters and diaries. So, we meet an Sussex gentleman turned powerful Persian courtier; a freed slave turned famous London composer; an English noblewoman turned trusted military advisor of Egyptian pasha. If any of them was a film character, the movie would’ve been derided as silly and unrealistic. However, real history is much more diverse and colorful, than pretty period dramas and school textbooks would show us.

The book is structured not chronologically, as I have initially expected, but thematically. There’re chapters, dedicated to food, architecture, science, marriage, painting. For example, we learn, which medieval King was the first to try curry and why the first mosque in London was built by Victorians.

Despite the rigorous research behind Exotic England, it is surprisingly easy to read. Yasmin writes with mesmerizing, poetic language, reminding us once again, that non-fiction doesn’t have to be staid. For example, a section on trade resembles an adventure novel with extraordinary characters. A chapter on immigrants from the former colonies breathes with personal stories.

Travelers, planning to visit London, will find many interesting facts and ideas. It will tell you, where to go in London to visit a magnificent Hindu temple out of gleaming marble, which you will find in one unassuming suburb; how to look for Islamic designs in the architecture of Westminster and St. Paul’s; where seek out the pagoda in Kew Gardens.

The post Book Review: Exotic England appeared first on History Geek in Town.

March 3, 2016

Dennis Severs’ House: not your average London history museum

There are plenty of history museums in London – some grand and central, some quant and local. However, Dennis Severs’ House stands aside. In fact, its creator and mastermind, Dennis Severs himself, didn’t call it a history museum at all – he considered it to be a “still-life drama”, a unique journey. And many agree with him – Dennis Severs’ House is counted amongst the most unforgettable operatic experiences in the world.

On the surface, there’re reasons to call it a London history museum. After all, it is situated in one of the supremely well-preserved houses of Spitalfields, and tells the story of a family of Huguenot silkweavers called Jervis. This family has occupied the house for more, than a century. Their story gives us a window to glimpse at their turbulent times: riots and change of dynasty, trade and industry, fashion and hobbies.

However, you won’t see a single glass case there. The rooms, each representing a particular decade in the family’s fortunes, are left in such a state, as if the Jervises has just gone for a walk. Unread letters, unfinished tea, a wig, carelessly hung over the chair: each room is breathing with their unseen presence. No electricity is allowed there, either: the chambers are dimly glowing with candlelight.

The story of the family begins in the earliest years of the 18th century, represented in the first room: frugal kitchen, domain of a thrifty Huguenot housewife. This lady’s unyielding eyes will look at you from the small portrait. She has every reason to be unyielding: she had survived monstrous religious persecution in her native France, escaping to England by chance. She was far from being the only one. In fact, by the start of our journey there is already a solid Huguenot community in London. They worship at French Church on Threadneedle Street, set up soup kitchen for poor compatriots, help newly arrived refugees to find employment.

Drawing room

Next room on the ground floor, the eating parlour, is still dark and modest. But some hints of comfort may give us a clue of the flourishing industry, which will soon grow out of cottages like this. Indeed, a lot of booming businesses of the later centuries originated in the family enterprises set in candle-lit houses. For example, the Courtauld Textiles, gargantuan and multinational, started in a small shop of Huguenot widow Louise Courtauld (another French refugee).

As you go upstairs, the things get brighter. Quite literally – the hues are softer and brighter now, the elegant drawing room glowing with neoclassical harmony. Looks like the owners’ good eye for silk design and fashion allowed them to succeed in the industry. Of course, they always have to keep a hand on the pulse – fashion changes rapidly, and last year’s patterns have to be sold at much reduced prices. Meanwhile, foreign competition doesn’t sleep – fashionable Court ladies still prefer to wear silk, smuggled from Italy or France, no matter how much is costs or how much His Majesty disapproves. Although, paradoxically, this clandestine fashion allows some Spitalfields silkweavers to make extra money by branding their goods as smuggled and selling them with pretended caution. Did the Jervis family engage in such peculiar marketing? We simply don’t know.

Now, up and up again – the blooming rococo awaits you upstairs. To an extent, it is mirroring the creations of now-prosperous Jervises. Spitalfields silk was famous for light-hearted, delicate flowers, blooming in its patterns. And the vanity table of new Mrs. Jervis is now the epitome of delicacy – feathers and pearls, fans and laces. There is a little porcelain tea cup left after the breakfast, splendid gown hanging nearby. This is a far cry from the first mistress of the house, isn’t it?

Mrs. Jervis’ Boudoir

Not that everything in their life is sweetness and light, though. The length of London Season, when silkweaving and other luxury trades usually find employment, has shrunk dramatically. It used to be from November to June, but now the upper-classes stay in London only from March to July. Silkweaving business is also quite prone to force majeure, such as unexpected Court mourning. It virtually cancels a whole season of colourful silks and can put about 15, 000 people in the industry out of job.

So, the ghost of hunger and destitution always looms even over the elegant houses of master weavers. This atmosphere of constant risk created just as constant strife for self-improvement: for new skills, new knowledge, better education. Education is, indeed, held in great esteem by Huguenot silkweavers – including, we might presume, the master of this house. Like many of his colleagues, he might spend his free hours on the meetings of local scientific societies. Contrary to popular belief, these institutions were not created by benevolent royal patronage – they were initiated by groups of curious artisans. Monmouth Head tavern, for example, housed the meetings of Spitalfields Mathematical Society. The participants met every Saturday, and any member who failed to answer a question in mathematics asked by another member was fined twopence. May be, that’s where Mr. Jervis had gone? Let’s hope he revised well…

Let your eyes linger on this picture of enlightenment and prosperity, while it lasts, because upstairs a new century will greet you. The advent of power loom and cheap outsourcing to provinces have all but destroyed London silkweaving. Mr. Jervis’ contemporary and colleague, Stephen Wilson, wrote, that London had lost “all small fancy works”. Of course, silkweavers didn’t go down without a fight: there were marches and riots, pleas to the government to protect the ancient craft from the advent of industrial competition. But they could only postpone the inevitable. In 1824, an Act was passed which basically left them at the mercy of the free market. Poverty descended upon Spitalfields, and it could not be shaken off for another century and a half. Once-prosperous Jervises are now forced to take lodgers. We are, in fact, now in a small and shabby room, belonging to one of the tenants. The bell, tolling outside, hails the dawn of the new era. As we know now, it will be an age of unparalleled industrial success and imperial expansion; however, the Jervises would hardly be able to take part in it…

A visit to Dennis Severs’ House will be especially convenient, if you are visiting London for a weekend: it’s open on Sunday afternoon, 12–16 p.m. The house is located at 18, Folgate Street; the nearest Tube station will be Liverpool Street.

Sources:

Eavesdropping on Jane Austen’s England , Lesley and Roy Adkins. (UK version)

, Lesley and Roy Adkins. (UK version)

Dr. Johnson’s London: Everyday Life in London in the Mid 18th Century, Liza Picard. (UK version)

Georgian London: Into the Streets , Lucy Inglis (UK version)

, Lucy Inglis (UK version)

The post Dennis Severs’ House: not your average London history museum appeared first on History Geek in Town.