Annabel Fielding's Blog, page 6

November 14, 2017

Book review: My Real Children, by Jo Walton

My Real Children by Jo Walton is a novel best known for its originality. Neither straightforward historical fiction nor a recognizable fantasy novel, it’s a book with a unique concept at its core.

Here’s what the official blurb says:

‘It is 2015 and Patricia Cowan is very old. ‘Confused today’ read the notes clipped to the end of her bed. Her childhood, her years at Oxford during the Second World War – those things are solid in her memory. Then that phone call and…her memory splits in two.

She was Trish, a housewife and mother of four.

She was Pat, a successful travel writer and mother of three.

She remembers living her life as both women, so very clearly. Which memory is real – or are both just tricks of time and light?’

Now, let’s start with the good things. First of all, I absolutely loved the premise, and I enjoyed reading about the two versions of Patricia’s life, which forked sharply depending on the answer she gave to one marriage proposal in her youth. Apart from her own fate, the world history in these two parallel realities also differs – while Trish the housewife experiences the twentieth century as we know it (politics-wise, at least), during the lifetime of Pat the writer the Cold War ultimately becomes a hot one.

Being a history geek myself, I also loved the author’s dedication to research, as well as her willingness to include a lot of decidedly unglamorous details of the 1950’s-1960’s: from the inability for an unmarried woman to get a mortgage to the ban on taking more than 25 pounds while travelling outside the UK.

The book was also interesting and easy to read, but, overall, it left me with a mixed feeling. I know there are readers who admire sparse, beige prose; it’s just that when it comes to the flourishes of writing, my tastes are closer to the Hilary Mantel end of the scale. Both tales were told in a kind of impersonal recitation I am more used to seeing in non-fiction biographies. I enjoyed the twists and turns of both of Patricia’s lives, but I wish it was written with more engagement.

The post Book review: My Real Children, by Jo Walton appeared first on History Geek in Town.

November 11, 2017

Book review: Children of Earth and Sky, by Guy Gavriel Kay

I would recommend this novel not just to historical fantasy lovers, but also to those who like regular historical fiction about the Renaissance.

Here’s what the official blurb says:

‘From the small coastal town of Senjan, notorious for its pirates , a young woman sets out to find vengeance for her lost family. That same spring, from the wealthy city-state of Seressa, famous for its canals and lagoon, come two very different people: a young artist traveling to the dangerous east to paint the Grand Khalif at his request-and possibly to do more-and a beautiful woman, posing as a doctor’s wife in her role of a spy.

The trading ship that carries them is commanded by the clever younger son of a m erchant family -with ambivalence about the life he’s been born to live. And farther east a boy trains to become a soldier in the elite infantry of the khalif-to win glory in the war everyone knows is coming.

erchant family -with ambivalence about the life he’s been born to live. And farther east a boy trains to become a soldier in the elite infantry of the khalif-to win glory in the war everyone knows is coming.

As these lives entwine, their fates-and those of many others-will hang in the balance, when the khalif sends out his massive army to take the great fortress that is the gateway to the western world…’

This book takes place in the same universe as Sarantine Mosaic and Lions of Al-Rassan. Just like the former was set in the fantasy version of the Byzantine Empire, and the latter dealt with the conquest of that world’s Muslim Spain, the plot of Children of Earth and Sky is played out in the Renaissance Mediterranean. The great powers in the game are the Republic of Seressa (Venice), the Holy Jaddite Empire (Holy Roman Empire), and their arch-adversaries, the Asharite/Muslim Osmanlis (no prizes for guessing who these guys are!).

While political fantasy tends to be fixated on the fates of great empires, this novel pays a lot of attention to the borderlands – to those located, metaphorically and literally, on the margins. There are smaller city-states who cannot boast the splendor of Venice, who have to trade with everyone and appease everyone in order to prevent themselves from being overrun by the powerful neighbours. There is the small, hardy, bitterly proud town of Senjan, whose inhabitants some call raiders and some call heroes. There are pale-eyed, flaxen-haired boys from Jaddite (Christian) villages, kidnapped in childhood and growing up to be high-ranking officers in the khalif’s army.

What I admire in Kay’s novels, among other things, is this great empathy. Here, there is no such thing as insignificant pain (or insignificant joy, for that matter), a natural byproduct of the games of thrones, something to be brushed aside. A lost brother finding his sister is as great a victory as the fate of an imperial fortress; perhaps, even more so.

As I’ve said, the novel takes place in the same universe as Sarantine Mosaic; moreover, it even covers the same geographical area. So, if you’ve read both novels (or, rather, the novel and the duology), be prepared to cry over the ruins of the Hippodrome where Taras of Megarium raced, and feel the shiver of recognition when a certain forest in Sauradia comes into view, and sob sometimes because ‘the maiden shall never walk the bright fields again, / Hair yellow as midsummer grain’.

‘At one point, for no reason he could understand, Pero felt a wave of sorrow pass through him. An old sorrow, not about himself or anyone here now, alive now, in the world. He stopped and looked around but saw nothing at all. He walked on and the sensation receded as he went’.

The post Book review: Children of Earth and Sky, by Guy Gavriel Kay appeared first on History Geek in Town.

October 29, 2017

Book Review: The Lions of Al-Rassan, by Guy Gavriel Kay

My love affair with historical fantasy novels continues, and here I will tell you about one particularly passionate fling.

Here’s the official blurb:

‘The ruling Asharites of Al-Rassan have come from the desert sands, but over centuries, seduced by the sensuous pleasures of their new land, their stern piety has eroded. The Asharite empire has splintered into decadent city-states led by warring petty kings. King Almalik of Cartada is on the ascendancy, aided always by his friend and advisor, the notorious Ammar ibn Khairan – poet, diplo mat, soldier – until a summer afternoon of savage brutality changes their relationship forever.

mat, soldier – until a summer afternoon of savage brutality changes their relationship forever.

Meanwhile, in the north, the conquered Jaddites’ most celebrated – and feared – military leader, Rodrigo Belmonte, driven into exile, leads his mercenary company south.

In the dangerous lands of Al-Rassan, these two men from different worlds meet and serve – for a time – the same master. Tangled in their interwoven fate – and divided by her feelings – is Jehane, the accomplished court physician, whose skills may not be enough to heal the coming pain as Al-Rassan is swept to the brink of holy war, and beyond’.

I’ve already reviewed the Sarantine Mosaic duology by the same author; and, just as Sarantium was thinly veiled Byzantium, Al-Rassan here is Al-Andalus (Muslim Spain) in its last period of flowering.

This novel creates a sweeping panorama of the dying, brilliant world. It shows an uneasy convivencia of the three faiths (Asharite/Muslim, Jaddite/Christian and Kindath/Jewish) in all its fragile beauty. While the corresponding period in our world tends to be either romanticized or vilified by actual historians, this work of fiction succeeded in creating a truly nuanced picture. The ruler of the beautiful Ragosa trusts his Kindath chancellor like no one else, but in some other cities (I will try to refrain from spoilers!) the Kindath live in a perpetual fear of pogroms. A learned Jaddite king of the north finishes building Moorish-style baths for his palace just as the High Clerics urge him towards a crusade against the infidels. The courtly culture of Al-Rassan is intricate, pretty secular, and extraordinarily beautiful, its ladies as sophisticated as the gentlemen – but their rulers tend to employ religious zealots from the desert tribes as their mercenaries.

This novel also contains one of the most beautiful, if understated, love plots I’ve ever seen in fantasy (or any other genre, for that matter).

In other words, I would urge you to read it if you enjoy unusual settings, captivating prose, deep social themes, frontier adventures, courtly intrigue, or any combination of the above.

The post Book Review: The Lions of Al-Rassan, by Guy Gavriel Kay appeared first on History Geek in Town.

October 20, 2017

Book Review: The Sarantine Mosaic, by Guy Gavriel Kay

I have deviated from straightforward historical fiction, enjoying my sudden and passionate affair with historical fantasy. I am not exactly a stranger to this genre – my journey into historical fantasy novels has started with Ellen Kushner several years ago, and took me through the genteel domains of Susanna Clarke and the decadent realm of Jacqueline Carey. But the Sarantine Mosaic duology is unlike anything I’ve ever read before.

Here’s what the official blurb says:

‘Rumored to be responsible for the ascension of the previous Emperor, his uncle, amid fire and blood, Valerius the Trakesian has himself now risen to the Golden Throne of the vast empire ruled by the fabled city, Sarantium.

amid fire and blood, Valerius the Trakesian has himself now risen to the Golden Throne of the vast empire ruled by the fabled city, Sarantium.

Valerius has a vision to match his ambition: a glittering dome that will proclaim his magnificence down through the ages. And so, in a ruined western city on the far distant edge of civilization, a not-so-humble artisan receives a call that will change his life forever.

Crispin is a mosaicist, a layer of bright tiles. Still grieving for the family he lost to the plague, he lives only for his arcane craft, and cares little for ambition, less for money, and for intrigue not at all. But an imperial summons to the most magnificent city in the world is a difficult call to resist.

In this world still half-wild and tangled with magic, no journey is simple; and a journey to Sarantium means a walk into destiny. Bearing with him a deadly secret, and a Queen’s seductive promise; guarded only by his own wits and a bird soul talisman from an alchemist’s treasury, Crispin sets out for the fabled city from which none return unaltered’.

First of all, I really admired the departure from the usual high fantasy theme of military glory. The protagonist is a gifted mosaicist; his craft is described lovingly and thoroughly. We can see the tesserae of different colours, set by his careful fingers so as to form together a torch of a falling god. We learn about the predecessors he admires, the old artworks he is awed by, the clerical regulations on religious images he has to contend with. For him, the great ambitions of great empires are, at best, a distant thing, and, at worst, a dangerous one. The imperial soldiers, when they do appear, are usually described with a wry detachment, while the golden, heroic Strategos of the Sarantine (Byzantine) army is a downright chilling figure.

On one hand, this is an easily recognizable historical landscape: Sarantium=Byzantium, Valerius and his queen=Justinian and Theodora, Varena=Ravenna (not that I object to that!). But, at the same time, the fantasy aspect of the novel lends the world new vividness and dynamism. The obscure rituals of Germanic tribes turn out to have some frightening material consequences. The mechanic birds, so similar to those intricate toys beloved by the Byzantine court, hide a dark secret of their creation. The Emperor’s ambitions in the West may yield a very different result from the one described in our history textbooks. And Yeats’ Flames that no faggot feeds, nor steel has lit,/Nor storm disturbs, flames begotten of flame really do at midnight on the Emperor’s pavement flit in this world.

Although the major plot is ruled by the grand political designs, the intricate tapestry (intricate mosaics?) of the world also leave some room for smaller lives and dreams. Really, I could talk about this book for pages and pages – about the charioteers hailed with monuments, about silent litters moving through the streets at night, about the domes of heartbreaking beauty and the deeds of heartbreaking horror (the deeds that forever refuse to sleep placidly in the cold ground). But, really, I would rather simply implore you to read it.

Buy Sailing to Sarantium on Amazon

Buy Lord of Emperors on Amazon

The post Book Review: The Sarantine Mosaic, by Guy Gavriel Kay appeared first on History Geek in Town.

September 9, 2017

Book review: Wolf Hall, by Hilary Mantel

This is one of the best historical novels of the last decade, the winner of the Booker prize; a bestseller adapted by the BBC. This is also the greatest panorama of the often-depicted Tudor age I’ve ever seen.

Of course, when it comes to praising Wolf Hall, I am horribly late to the party. I want to say in my defense, though, that when it first came out in 2009 I was still busy with my GCSEs. The writing is mesmerizingly beautiful and poetic, and the scale of historical detail is astounding. I’m not only talking about the standard historical fiction fare of Tudor feasting and court protocol, but also about the kind of supplies you would need for an Irish war, the kind of bags the messengers of German bankers would carry, and the kind of Italian treatises on accounting an ailing merchant might read in bed.

I confess, I was especially impressed by the emphasis on the economic and logistical part of the whole Reformation thing (as opposed to the more usual focus on the romantic part of Henry the 8th’s turbulent private life).

I know, a lot of people are angry about the book’s portrayal of Thomas More, as it is focusing on his persecution of heretics (harsh even by the standards of the time), rather than on his humanistic ideas. I’d argue, though, that, while Mantel’s depiction of the man might have been unusually harsh, it wasn’t by any stretch a one-dimensional one. Her More is sometimes repulsive, sometimes sympathetic, and, overall, incredibly human. I think, we would be hard-pressed to find a reader who didn’t cry at the scene of his trial. It’s not an accident that More’s execution in the end of the novel (it’s not much of a spoiler, is it?) comes to symbolize everything that’s wrong about the new regime.

Mantel’s version of Anne Boleyn has caused even more conflicts, and for the same reason – here, this usually romanticized figure is, at best, an anti-heroine. I loved her, though. Yes, the Anne of Wolf Hall is a calculating schemer, who shows very little sympathy for others (including her own sister). But, at the same time, she genuinely loves her daughter, she is enthusiastic about the reform, she is distressed about Henry’s ‘gallantry’ with other ladies (including the aforesaid sister); in short, she is a fallible human being, who certainly didn’t deserve a cruel death.

“They compete to tell stories of how she is not worthy. Or not human. How she is a snake. Or a swan. Una candida cerva. One single white doe, concealed in leaves of silver-grey; shivering, she hides in the trees, waiting for the lover who will turn her back from animal to goddess.”

When it comes to Cromwell himself – I know this is going to sound incredibly bizarre, but his story here reminded me of Hamilton. An under-explored historical figure became a compelling anti-hero who rose from humble origins thanks to hard work, enjoyed political success despite being resented for his lack of pedigree, shaped momentous historical events (including some morally questionable ones), and eventually fell spectacularly to his death. Plenty of Cromwell’s enemies here throw around accusations of a “bastard, orphan, son of a whore and a Scotsman” variety, while his propensity to write (laws) like tomorrow won’t arrive is commented upon by virtually everyone.

“‘Cromwell,’ Butts says, ‘I couldn’t kill you if I shot you through with cannon. The sea would refuse you. A shipwreck would wash you up.’”

If you’ve already read it and liked it, I’ll recommend you to try next.

The post Book review: Wolf Hall, by Hilary Mantel appeared first on History Geek in Town.

August 23, 2017

Book Review: Look Who’s Back, by Timur Vermes.

Reviewing one of the boldest works of fiction in the last decade.

From the official blurb:

‘Berlin, Summer 2011. Adolf Hitler wakes up on a patch of open ground, alive and well. Things have changed – no Eva Braun, no Nazi party, no war. Hitler barely recognises his beloved Fatherland, filled with immigrants and run by a woman.

People certainly recognise him, albeit as a flawless impersonator who refuses to break character. The unthinkable, the inevitable happens, and the ranting Hitler goes viral, becomes a YouTube star, gets his own T.V. show, and people begin to listen. But the Führer has another programme wit h even greater ambition – to set the country he finds a shambles back to rights.’

h even greater ambition – to set the country he finds a shambles back to rights.’

This novel has received a staggering amount of 1* reviews from people who haven’t read it. They confess as much themselves, and it’s probably the first time since high school when I encountered people being proud of NOT having read a book. They found the blurb to be offensive enough, and sprang into action.

Well, what can I say? They’ve basically cheated themselves, because the book’s message could not have been more clearly anti-Nazi. It basically says: “Don’t be fooled by a dictator’s sweet smiles – in his dreams, he’s already got the crematoriums going. Don’t ascribe anything he says to ‘risqué jokes’ and ‘provocation attempts’. Real monsters don’t strut around with claws and hooves, they can be charming and seemingly reasonable – and that is why they are so dangerous’.

Does that ring any bells?

Of course, I understand where all this bewilderment is coming from. Over the past decades, we have turned the Nazis into stock comic book villains, usually served with a garnish of occult experiments and evil laugh. An unfortunate result? People are now hesitant to recognize or condemn real Nazis, if they fall somewhat short of the Red Skull.

And, for all its humour, this novel is chillingly frightening precisely because its infamous protagonist seems so human, recognizable, relatable even (at least, when it comes to the comedic fish-out-of-the-water situations). It holds up a mirror to our world, poised to allow any poison past radar if it adopts the veneer of ‘provocation’ and ‘boldness’, and the reflection is not pretty.

All the faults I found in this book are of a purely literary variety. For instance, this reader often found herself stuck in the swamp of the narrator’s endless introspections – though the author has captured the inane, narcissistic style of the real Fuhrer well enough! The climax is also somewhat lacking; the film adaptation managed it better. However, this novel boasts the most chilling Christmassy epilogue you have read in a long time.

The post Book Review: Look Who’s Back, by Timur Vermes. appeared first on History Geek in Town.

August 8, 2017

Book Review: Golden Hill, by Francis Spufford.

An award-winning historical fiction, perfect for the lovers of the 18th century, American history, or simply beautiful writing.

From the official blurb:

“New York, a small town on the tip of Manhattan Island, 1746. One rainy evening, a charming and handsome young stranger fresh off the boat from England pitches up to a counti ng house on Golden Hill Street, with a suspicious yet compelling proposition — he has an order for a thousand pounds in his pocket that he wishes to cash. But can he be trusted? This is New York in its infancy, a place where a young man with a fast tongue can invent himself afresh, fall in love, and find a world of trouble . . .”

ng house on Golden Hill Street, with a suspicious yet compelling proposition — he has an order for a thousand pounds in his pocket that he wishes to cash. But can he be trusted? This is New York in its infancy, a place where a young man with a fast tongue can invent himself afresh, fall in love, and find a world of trouble . . .”

Now, I want to note here, that the novel isn’t quite as upbeat and Hamilton-esque as the blurb implies. This tale is smaller and darker; but then, its New York is smaller and darker, too.

I want to say outright, that I’ve absolutely loved this book. It really is the most 18th century novel about the 18th century I’ve ever read. The language, the slang, the literary conventions of the day are meticulously reconstructed, and then masterfully translated for the 21st century reader. The result is… well, I’d have called it a page-turner, if only I didn’t want to linger on each sentence a bit more.

There is a mystery to keep you guessing until the very last chapter; there are duels (…so, yes, it is a bit Hamilton-esque after all); there are sparring lovers whose witticisms are actually witty (a rare treat in any genre). But, looming the largest of all, there is the city itself.

Francis Spufford does for the 1746 New York what . The setting really comes alive under his pen. It’s full of twisty alleyways, and solid houses of the prosperous Dutch merchants, and austere Reformed churches; there is even one makeshift theatre. This last one is used to recreate the tragedy of the Roman Republic with all the silliness of the Georgian theatre, by the way. Oh, and there is a red-headed actress!

The post Book Review: Golden Hill, by Francis Spufford. appeared first on History Geek in Town.

July 17, 2017

Book review: The Years of Rice and Salt, by Kim S. Robinson

An epic world history novel, dealing with a world that could have been.

From the official blurb:

“It is the 14th century, and one of the most apocalyptic events in human history is set to occur – the coming of the Black Death. History teaches us that a third of Europe’s population was destroyed. But what if the plague had killed 99 percent of the population instead? How would the world have changed? This is a look at the history that could have been – a history that stretches across c enturies, a history that sees dynasties and nations rise and crumble, a history that spans horrible famine and magnificent innovation. These are the years of rice and salt.

enturies, a history that sees dynasties and nations rise and crumble, a history that spans horrible famine and magnificent innovation. These are the years of rice and salt.

This is a universe where the first ship to reach the New World travels across the Pacific Ocean from China and colonization spreads from west to east. This is a universe where the Industrial Revolution is triggered by the world’s greatest scientific minds – in India. This is a universe where Buddhism and Islam are the most influential and practiced religions, and Christianity is merely a historical footnote”.

Announcement: I have finally found an alternate history novel that I’ve a) managed to finish and b) actually loved. Most alternate history authors suffer from what one reviewer called a war-gaming focus on, well, wars, high politics and Great Men. This novel is completely different – Robinson eschewed this kind of approach in favor of showing centuries of change through the eyes of (usually) ordinary people caught up in the events. Moreover, these people tend to be poets, historians, scholars and philosophers – in other words, precisely the people whom most historical novels (alternate or not) tend to shove to the sidelines.

Robinson created an epic panorama of a different world, stretching from the 14th century to the year 2045. Interestingly, the cast of main characters stays the same, reincarnating over and over (and this novel features the most poetic and complex depiction of reincarnation I’ve ever seen). In the later novellas I found heartening shout-outs to the protagonists’ previous lives. Sometimes these are mystical (a resilient Chinese widow suffers from vivid dreams, where she is a young sultana leading her people to repopulate Al-Andalus), sometimes ordinary (a 20th century university professor talks about a unique anthology of women’s poetry composed by the aforesaid Chinese widow).

There are clashes of the empires all right, and the description of this world’s Great War is going to haunt you for days on end. But the author’s heart clearly lies with the social history and cultural change, and thank Eru for that. There are plenty of nerdy discussions of philosophy and religion, religion and science, science and art. There is also, to my great joy, a lot of attention paid to the status of women in any given society, and the characters who want to change things are never treated as a punchline.

The post Book review: The Years of Rice and Salt, by Kim S. Robinson appeared first on History Geek in Town.

July 1, 2017

Book review: The Silver Pigs, by Lindsey Davis

This is certainly a great historical fiction read, especially if the Roman Empire is your thing.

From the official blurb:

“THE SILVER PIGS sees Falco cynically eyeing up the new Roman emperor, Vespasian. Our hero, a private informer, rescues a young girl in trouble and is catapulted into a dangerous game involving stolen imperial ingots, a dark political plot and, most hazardous of all, a senator’s daughter connected to the traitors Falco has sworn to expose…”

I’ve already reviewed Crystal King’s upstairs-downstairs tale of the great est gourmand of antiquity and the multiple authors’ take on the tragedy of Pompeii. Now, continuing the Ancient Roman theme, I’m going get to the first novel in Lindsey Davis’ famous series.

est gourmand of antiquity and the multiple authors’ take on the tragedy of Pompeii. Now, continuing the Ancient Roman theme, I’m going get to the first novel in Lindsey Davis’ famous series.

I’m going to get the less-flattering point out first, so that I can then start the much-deserved praise with a clear conscience: when it comes to the actual mystery plot, Davis is no Agatha Christie. Perhaps, it’s the early book effect, and the mysteries will get more complicated as the series roll on – I’m definitely going to check that!

But the complexity (or lack of it) of the whodunit element isn’t even that important here (strange assertion for a mystery novel review, I know!). Falco series are to the Roman Empire what Kerry Greenwood’s Phryne Fisher novels are to the 1920s; you can read them solely for the pleasure of immersing yourself in the era.

It’s a refreshingly ironic portrayal of what is too often dubbed the greatest empire of antiquity. Falco lets us see it at its best (a glittering Roman triumph), worst (the horrors of slave-powered silver mines), funniest (Linnea the enterprising laundress is a larger-than-life figure on par with Wodehousean aunts) and most mundane. This latter category includes rapacious landlords, tangled family affairs (shown about as far from the usual portrayal of a stately paterfamilias as it can get) and dreary seaside resorts. The characters are instantly likeable, and you are bound to follow them even you don’t want to follow the latest conspiracy.

Buy on Amazon

The post Book review: The Silver Pigs, by Lindsey Davis appeared first on History Geek in Town.

June 16, 2017

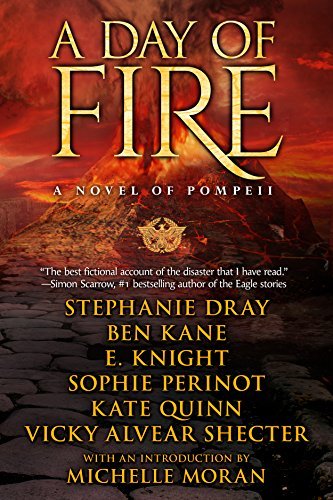

Book review: A Day of Fire by Stephanie Dray et al.

If you like historical fiction about the Roman Empire, A Day of Fire should really be on your TBR list.

From the official blurb:

“Pompeii was a lively resort flourishing in the shadow of Mount Vesuvius at the height of the Roman Empire. When Vesuvius erupted in an explosion of flame and ash, the entire town would be destroyed. Some of its citizens died in the chaos, some escaped the mountain’s wrath . . .

Six authors bring to life overlapping stories of patricians and slaves, warriors and politicians, villains and heroes who cross each others’ path during Pompeii’s fiery end. But who will escape, and who will be buried for eternity?”

Thanks to Crystal King’s debut novel, I’m now on an Ancient Roman kick; so, apart from adding the whole of Lindsey Davis to my wish list, I’ve bought this book – and I wasn’t disappointed. Among its other merits, such as the detailed historical surroundings and the poignant plots, it contains the kind of thing I like in particular – showing a momentous event of an era through (very) diverse and multiple viewpoints.

The book consist of six stories of vastly different characters, overlapping and intertwining in often unexpected ways. There is a spirited heiress, who watches with terror as the wedding murals bloom upon her villa’s walls, unsuspecting of the real terror to come. There is a gruff ex-legionnaire down on his luck, who stakes his future on a gladiatorial context; but the roar of the arena is drowned by the roar of Vesuvius. There is a crippled senator, tired of life and willing to stay in the doomed city, until an unexpected savior comes his way…

Most of all, I loved the multilayered nature of the tale. A conniving temptress of one character’s story might turn out to be a much-abused survivor of her own, and a stereotypical smug, corrupt official might show unexpected depths, when the world starts to burn.

The post Book review: A Day of Fire by Stephanie Dray et al. appeared first on History Geek in Town.