Michael Roberts's Blog, page 39

March 3, 2021

UK budget: coming out of COVID

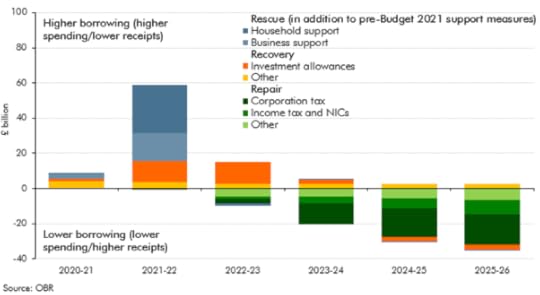

The UK economy was the hardest hit of the top G7 economies in the year of the COVID. Real GDP fell 9.9%, which the multi-millionaire and richest man in the British parliament, Conservative Chancellor, Rishi Sunak admitted was the worst contraction in national income in 300 years!

The UK government also failed to protect the people from COVID-19. Following a resurgence of infections over the winter, around 1 in 5 people in Britain have so far contracted the virus, 1 in 150 have been hospitalised, and 1 in 550 have died, the fourth highest mortality rate in the world. While output partially recovered in the second half of 2020, the latest lockdown and temporary disruption to EU-UK trade at the turn of the year will deliver yet another fall in GDP in Q1 2021.

This has forced the government to extend its COVID support packages in Sunak’s government budget for 2021-22 announced today. They have all been pushed on to end-September in the hope that the fast vaccination rollout will enable the economy to open up by then and avoid a sharp rise in unemployment and small business bankruptcies by the end of this year.

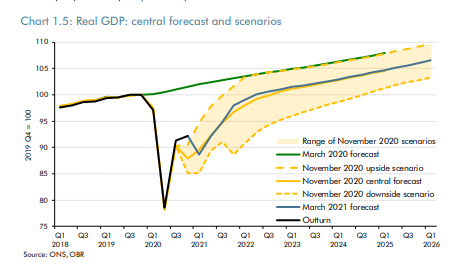

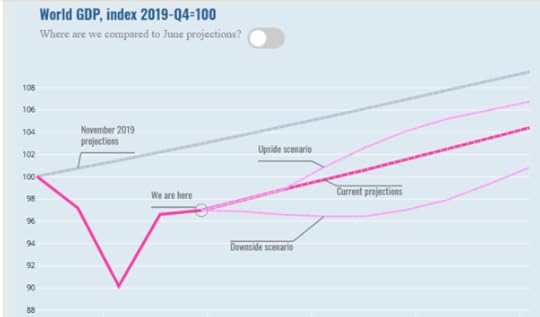

The optimistic government forecast is that the UK economy will bounce back by about 4% this year and eventually GDP will regain its pre-pandemic level in the second quarter of 2022, or some two and half years since the pandemic broke. Even if that is possible, unemployment is set to rise by another half a million to 2.5m, or 6.5%. But that assumes all the 4.7m workers currently furloughed will retain their jobs next September. Indeed, even if these growth forecasts are met, the UK economy will still be short by 3% from the pre-pandemic growth rate, which was already weak. This is clearly not a V-shaped recovery by a reverse square root.

Source: OBR

Longer term, the official forecast for average real GDP growth is just 1.7% a year, or some one-third below pre-2019 growth rates. That suggests a significant impact from ‘scarring’ to employment and investment capacity from COVID and from the loss of trade from Brexit.

Source; OBR

What are Sunak and the Conservatives proposing as a recovery plan for the UK economy? It boils down to trying to boost investment in the capitalist sector of the economy with massive tax breaks, new ‘freeports’ where large businesses can avoid tax and regulations; and through cheap guaranteed loans for businesses.

But there is no help for public services and public sector workers. A public sector wage freeze will continue – and this is after the longest squeeze in average real wages (some 18 years) since the end of Napoleonic Wars in 1822! There is no planned boost in funding for public services apart from limited increases in the health sector, where ‘stealth’ privatisation of NHS resources will be stepped up. And there is little help for hard-pressed local councils to meet their obligations, so that most are being forced to raise local taxes this year just to stop going bust. At the same time, the government did not opt to tax the huge ‘windfall’ profits made by hedge funds and financial institutions racked up from speculating in the booming stock markets of the world while millions were relying on COVID welfare. One former hedge fund manager, employer and friend of Sunak paid himself $343m in dividends from speculation in 2020!

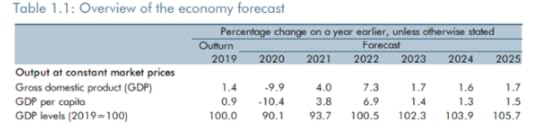

The government announced the setting up of a National Infrastructure Investment Bank to be centred in the north of England with a piecemeal funding of £12bn. Public investment to GDP will rise to over 2.5% for the first time in decades, but in a capitalist economy, it is business investment that drives incomes, employment and productivity – and on this marker, the UK economy is operating abysmally. The forecast for business investment growth, despite the government’s talk, looks dismal.

My calculations from the official forecast suggests that business investment will rise to about 7.8% of total national spending by 2025 from the COVID slump of 7.1%. But even in 2025, that investment rate will be below 2016 levels and only 5% above 2007 – after 18 years!

Source: OBR, my calcs

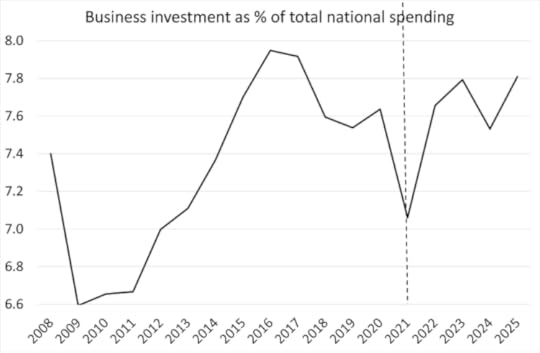

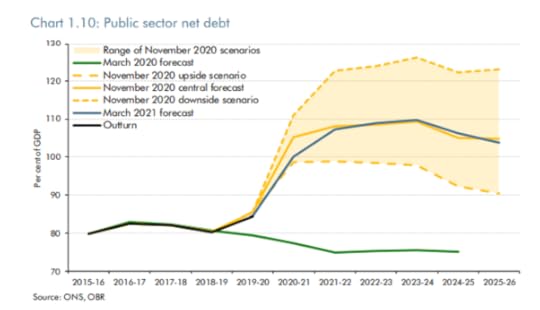

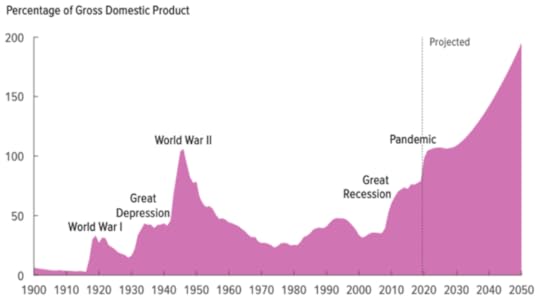

The COVID pandemic forced the government to spend unprecedented amounts for rescue support to households, businesses and public services to a total cost £344 billion. Huge budget deficits will emerge right through this parliament and public sector debt will go over 100% of GDP and remain above that level throughout to 2025.

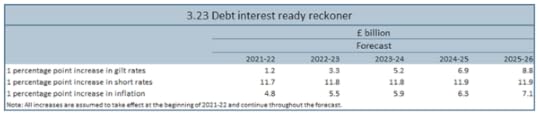

Sunak talked strongly about putting public finances in order. There is much debate about whether it matters or not if public sector debt is so high when interest rates on debt are so low. Indeed, the interest cost on this debt is expected to fall to a historic low of just 2.4 per cent of total revenues.

Sunak still thinks it matters and plans to raise revenues to reduce the annual budget deficits to 2025. There is a plan to hike corporation profits tax from 19% of GDP to 25% for larger firms, but it won’t be applied until 2023 and even then the rate will be no more than the OECD average. Sunak will freeze income tax thresholds, so that people will start paying tax at lower real incomes than before. And it’s not true that the government is avoiding austerity. Apart from not reversing the huge cuts to local and public services over the last ten years, the Sunak government will cut government spending by another £4bn a year from hereon. Indeed, the total tax burden for British people will rise to its highest level since the early 1960s!

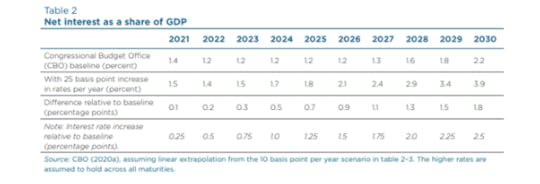

And can the public debt burden be controlled? It all depends on growth. The simple formula for containing the debt to GDP ratio is if the real GDP growth rate (g) is faster than the rise in the interest costs of the debt (r). But if real GDP growth (g) is only likely to average 1.7% a year, then it won’t take much of a rise in r to see debt to GDP rising.

According to the OBR, “the 30 basis point increase in interest rates that has happened since we closed our forecast on 5 February would already add £6.3 billion to the interest bill in 2025-26 published in this document. All else equal, that would be enough to put underlying debt back on a rising path relative to GDP in every year of the forecast.”

Supporters of Modern Monetary Theory argue that the public debt level does not matter anyway because the Bank of England can just print money to cover the debt increase. Indeed, it has done just that during the year of the COVID. So the government could order the Bank of England to continue printing money and fund asset purchases at just 0.1%, regardless of economic and financial conditions and whatever happens to inflation.

But if the size of the debt rises, it will increase the amount of debt servicing costs, if government bonds are used to increase and service the debt. That will eat into available funds for government to spend on services over time. If interest rates are held down and the Bank of England ‘’monetises’’ the debt, then foreign investors will start to take their money out of sterling and the pound will slide, driving up inflation. There is no ‘free lunch’ in debt and no country is an island, including the British Isles.

It all depends on whether the UK economy can ‘’grow out’’ of its debt burden as it did after the second world war through a combination of high public investment and rising inflation (that eventually forced the devaluation of the pound). Given that the profitability of capital in the UK is at an all-time low and the business investment rate worse than in any other major economy, the prospects of achieving that are small. Before this parliamentary term ends, the UK economy could be facing a new economic crisis.

February 20, 2021

Mission impossible

Italian-American economist, Mariana Mazzucato, who works and resides in London, has become a big name in what we might call ‘centre-left’ or even in mainstream economic and political circles. She has a new book out, Mission Economy: a moonshot guide to changing capitalism.

Mazzucato was briefly an economic adviser to the UK Labour Party under Corbyn and McDonnell; she apparently “has the ear” of radical Congress representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez; she advised Democratic presidential hopeful, Senator Elizabeth Warren and also Scottish Nationalist leader Nicola Sturgeon. She was even accorded the title of “the world’s scariest economist” because her ideas were apparently really shaking up things among the great and good. According to the London Times newspaper, “admired by Bill Gates, consulted by governments, Mariana Mazzucato is the expert others argue with at their peril”.

However, whereas she appeared to start out as adviser to the left of the political spectrum, more recently she has become available to all. She quickly dropped her role as adviser to Corbyn. According to one reviewer of her new book, “Mazzucato quickly recognised that there was no real role as a Corbyn adviser and resigned after two months.” She said: “The actual people pulling the strings were Seumas Milne and others. I felt like well, if you want to do your own thing, do it. But don’t do it in my name,’ she told the Daily Mail. The Mail commented: “After this brief flirtation with the wrong sort of politician, she is keen to point out that she has worked closely with the Tories, advising Greg Clark, among others, on his industrial strategy when he occupied the constantly changing role of Business Secretary.”.

Mazzucato now advises governments and institutions internationally (Policy Papers : Mariana Mazzucato) and appears on various headline forums and seminars. The World Health Organization appointed her chief of its Council on the Economics of Health for All in 2020. Indeed, she recently praised the appointment of (unelected) former ECB chief and central banker, Mario Draghi, as Italy’s prime minister, presumably because he is going to save Italy’s economy. Not so scary after all, then.

I have reviewed Mazzucato’s previous (much weightier) books, The Entrepreneurial State and the Value of Everything in other posts. In this latest book, she continues her main argument that she made in those other books that the public sector should lead the way in modern economies. “Instead of acting as investors of first resort, far too many governments have become passive lenders of last resort, addressing problems only after they arise. But as we should have learned during the post-2008 Great Recession, it costs far more to bail out national economies during a crisis than it does to maintain a proactive approach to public investment.” Rightly, she points out that “the more we subscribe to the myth of private-sector superiority, the worse off we will be in the face of future crises.” The role of public funded innovation and publicly owned research and development has been deliberately downplayed by the mainstream. And yet it has been publicly funded research that has led to the speedy rollout of vaccines for the COVID pandemic and it’s been the publicly owned and run health services that have provided the best response in reducing deaths from the pandemic.

Mazzucato rightly wants to restore and proclaim the “narrative of government as a source of value creation.” (although as I argue in my review of her last book, government does not create value (as profit for capital), but use values (for society) – a distinction that Mazzucato does not recognise, but capitalists do). She notes, for example, that an Obama administration loan was crucial to the success of Tesla, and that a 1980s BBC computer literacy program led to the founding of a leading software development firm and the creation of a low-cost computer used in classrooms around the world.

But above all, in this book, she aims to promote the model of the Apollo space mission to the moon as the way forward to develop innovations and diffuse them across the economy; what she calls a ‘mission-oriented’ approach.

As she puts it: “The Apollo program demonstrated how a clearly defined outcome can drive organizational change at all levels, through multi-sector public-private collaboration, mission-oriented procurement contracts, and state-driven innovation and risk taking. Moreover, such ventures tend to create spillovers – software, camera phones, baby formula – that have far-reaching benefits.” And what this model shows, she claims, is that “landing a man on the moon required both an extremely capable public sector and a purpose-driven partnership with the private sector.”

So what modern capitalism needs is a ‘purpose-driven’ partnership between the public and private sectors: “moonshots must be understood not as siloed big endeavours, perhaps the pet project of a minister, but rather as bold societal goals which can be achieved by collaboration on a large scale between public and private entities.” Apparently, we need “a bold portfolio approach, a redesigning of tools like procurement and a proper economic theory to confront the directionality of growth head on” – whatever “confronting the directionality of growth” means.

Mazzucato recognises that so-called public-private partnerships in the past have often not turned out in the public interest. We must “not repeat the failures associated with today’s digital economy, which emerged in its current form after the state provided the technological foundation and then neglected to regulate what was built on it. As a result, a few dominant Big Tech firms have ushered in a new age of algorithmic value extraction, benefiting the few at the expense of the many.” Instead, we must “capture a common vision across civil society, business, and public institutions.”

She argues that public–private partnerships have focused on de-risking investment through guarantees, subsidies and assistance. Instead, they should emphasize sharing both risks and rewards. So governments and capitalist companies are to share the risks and then share out the rewards. That idea shows the difficulty inherent in the mission approach. The mission for overcoming the COVID pandemic has already shown which sector has taken the risks and which will gain the rewards- as did the Apollo mission.

Mazzucato reckons that a fundamental reappraisal of the role of the public sector is required that goes beyond the traditional ‘market failure’ framework derived from neoclassical welfare economics to a ‘market co-creating’ and ‘market-shaping’ role. “It is not about fixing markets but creating markets”.

But should the mission of government be to ‘create markets’ or ‘shape markets’? Is it really possible that the public sector will be allowed to take the lead in investment for social purpose over investment for profit under capitalism? Is it really possible that a ‘common vision’ can be ‘captured’ between big business in its drive for profits for its shareholders and governments which may have different objectives? Can climate change and global warming be reversed while the fossil fuel industry remains untouched by governments? Can rising inequality be reversed through some public-private ‘common vision’? Can technological unemployment be avoided when the big tech companies apply robots and AI to replace human labour? Can a mission ‘moonshot’ approach based on partnership with big business and ‘creating markets’ really succeed, given the social structure of modern capitalism? When you pose these questions, I think the answer becomes clear.

Indeed, some of the mission-approach schemes that Mazzucato cites in her book have been just as unsuccessful as previous ‘public-private ‘partnerships. She advised Germany’s Energiewende (energy transition to renewables), which has failed to deliver any better than others in reducing carbon emissions. She advised the Scottish Nationalists on launching its Scottish National Investment Bank. Within two months, the SNP government cut its funding from £241m to £205m, a pathetic amount to start with. When Labour under Corbyn first proposed such a SNIB, it was to be capitalised with £20bn! And as for UK PM Johnson’s ‘Operation Moonshot’ for mass test and tracing, say no more.

And how are these missions to be democratically controlled to achieve ‘a common vision’? Mazzucato says it will need “involving citizens in solving societal challenges and creating wide civic excitement about the power of collective innovation”. Wading through this jargon, she seems to be saying that policy makers, researchers (like herself) and businesses will get together and listen to ‘citizens’ somehow and out of this will come a widely approved set of ‘missions’ for innovation.

Mazzucato sums it up: “Mission Economy offers a path to rejuvenate the state and thereby mend capitalism, rather than end it.” In my view, that is a mission impossible.

February 14, 2021

Deflation, inflation or stagflation?

During the year of the COVID, global consumer and producer prices dropped fell. In some manufacturing-based economies, there was even a fall in price levels (deflation) eg the Euro area, Japan and China).

US inflation rate (annual %)

“Effective demand” as Keynesians like to call it, plummeted, with business investment and household consumption dropping sharply. Savings rates rose to high levels (both corporate savings relative to investment and household savings).

Household savings rates (% of income) – OECD

Country20132014201520162017201820192020United Kingdom3.13.64.92.20.06.16.519.4United States6.67.67.97.07.27.87.516.1Euro area (16 countries)5.65.75.75.75.66.46.714.3Many companies went bust and many lower income households either lost their jobs or faced reductions in wages. Higher income households maintained their wage levels, but they were unable to travel or spend on leisure and entertainment.

But now, as the rollout of vaccines accelerates across the advanced economies and governments and central banks continue to inject credit money and direct funding for business and households, the wide expectation is that the major economies will make a fast recovery in investment, spending and employment – at least by the second half of 2021.

Now the concern is that, instead of a continued slump, there is a risk of ‘overheating’ in the major economies, causing an inflation of prices generated by ‘too much’ government spending and continued ‘loose’ monetary policy.

The UK’s Financial Times echoed the voices of leading mainstream American Keynesian economists that “a strong recovery and sizeable stimulus raise the possibility of the US ‘overheating’”. Former treasury secretary Larry Summers and former IMF chief economist Oliver Blanchard both warned that the passing by the US Congress of the proposed $1.9tn spending package, on top of last year’s $900bn stimulus, risked inflation.

Summers argued that the size of the spending package, about 9 per cent of pre-pandemic national income, would be much larger than the estimate of the shortfall in economic output from its ‘potential’ by the Congressional Budget Office (CBO). That, combined with loose monetary policy, the accumulated savings of consumers who have been unable to spend and already-falling unemployment could contribute to mounting inflationary pressure. ‘Pent-up demand’ would explode, leading to 1970s-type inflation. “There is a chance that macroeconomic stimulus on a scale closer to World War II levels than normal recession levels will set off inflationary pressures of a kind we have not seen in a generation,” said Summers.

Summers’ view must be taken with the proverbial pinch of salt, considering that in April last year, he argued that the COVID pandemic would be merely a short sharp decline, somewhat like tourist areas (Cape Cod in his case) closing down for the winter, and the US economy would come roaring back in the summer. Two things blew that forecast out of the Atlantic: first, the winter wave of COVID (actually in the case of the US, because of lax lockdowns etc, the spring wave just continued); and second, hundreds of thousands of small businesses (and some larger ones) went bust and so business was not able to return to normal after the ‘winter break’.

Summers’ argument is also based on some very dubious economic categories. He measured the fiscal and monetary stimulus being applied by Congress and the Fed in 2021 against the “potential output” of the economy. This is a supposed measure of the maximum capacity of investment and spending that an economy could achieve with ‘full employment’ without inflation. The category is so full of holes, that economists come up with different measures of ‘potential output’, which anyway seems to be a moveable feast depending on productivity and employment growth and likely investment in new capacity.

Larry Summers reckons the Biden relief package will inject around $150 billion per month, while CBO says the monthly gap between actual and potential GDP is now around $50 billion and will decline to $20 billion a month by year-end (because the CBO assumes the COVID-19 virus and all its variants will be under control).

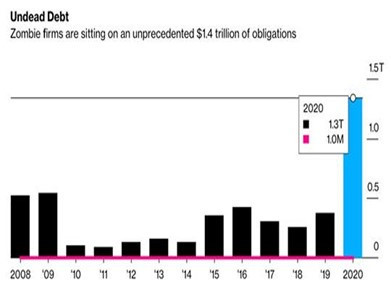

Former New York Fed President Bill Dudley backed up Summers in arguing that Four More Reasons to Worry About US Inflation. First, economic slumps brought on by pandemics tend to end faster than those caused by financial crises. This is Summers’ Cape Cod argument revived. And second, “thanks to rescue packages and a strong stock market, household finances are in far better shape now than they were after the 2008 crisis.” You might ask whether a rocketing stock market benefits the 93% of Americans who have no stock investments (or large pension funds). And while the better-paid may have increased savings to spend, that is not the case for lower to middle income earners. Dudley also claimed that companies have “plenty of cash to spend and access to more at low interest rates”. Again, he seems to concentrate on the large techs and finance firms that are hoovering up government money and stock market gains. Meanwhile there are hundreds of thousands of smaller companies which are on their knees and in no position to launch a big investment plan even if they can get loans at low rates. The number of these zombie companies are growing by the day.

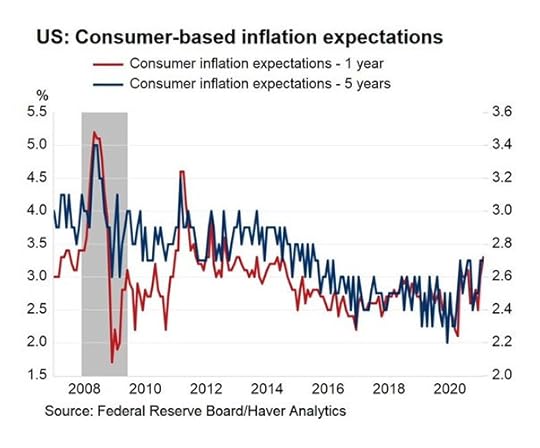

It’s true as Dudley says that ‘inflation expectations’ are rising and that can be a good indicator of future inflation – if households think prices are going to rise, they tend to start spending in advance and so stimulate price rises – and vice versa. And it’s also true that, given the sharp fall in price inflation at the start of the pandemic lockdowns last year, any recovery in prices now will show up as a statistical year on year rise. But as you can see from this graph below inflation expectations are hardly at a level of “of a kind we have not seen in a generation” (Summers).

The other worry of the ‘inflationists’ is that the US Fed will generate an inflationary spiral through its ‘lax’ monetary policies. The Fed continues to plough humungous amounts of credit money into the banks and corporations and also has weakened its inflation target of 2% a year to a 2% average inflation over some undefined period. Thus, the Fed will not hike interest rates or cut back on ‘quantitative easing’ even if the annual inflation rate heads over 2%.

Fed chair Jay Powell made it clear in a recent speech to the Economic Club of New York (business people and economists) that the Fed had no intention of reining in its monetary easing. Powell even gave a date – no tightening of policy before 2023. This has upset the anti-inflation theorists. Gillian Tett in the FT put it: “the Fed has now taken this so-called “forward guidance” to a new level that seems dangerous. He should puncture assumptions that cheap money is here indefinitely, or that Fed policy is a one-way bet. Otherwise his attempts to ward off the ghosts of 2013 will eventually unleash a new monster in the form of a bigger market tantrum, far more damaging than last time — especially if investors have been lulled into thinking the Fed will never jump.”

The FT itself went on: “The Fed’s pledge to leave policy on hold until 2022, however, risks undermining its credibility: it cannot promise to be irresponsible. … it must watch out for any sign that inflation expectations are rising and respond to the data rather than tie itself to the mast.” Dudley echoed this view. “If the Fed does not tighten when inflation appears, it might have to reverse course quickly if it starts getting out of hand. That, in turn, could set off market fireworks.”

But are the inflationists’ warnings valid? First, they are really based on a quick and significant ‘Cape Cod’ economic recovery. But the pandemic is not over yet and the vaccines have not been rolled out to any level to suppress the virus sufficiently yet. What if the new variants that are beginning to circulate are resistant to existing vaccines so that a new ‘wave’ emerges? A summer recovery could be delayed indefinitely.

Moreover, these inflation forecasts are based on two important theoretical errors, in my view. The first is that the huge injections of credit money by the Fed and other central banks that we have seen since the global financial crash in 2008-9 have not led to an inflation of consumer prices in any major economy even during the period of recovery from 2010 onwards – on the contrary (see the US inflation graph above), US inflation rates have been no more than 2% a year and they have been even lower in the Eurozone and Japan, where credit injections have also been huge.

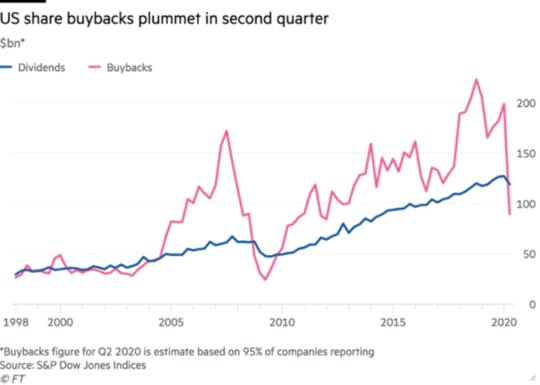

Instead, what has happened has been a surge in the prices of financial assets. Banks and financial institutions, flooded with the generosity of the Fed and other central banks, have not lent these funds onwards (either because the big companies did not need to borrow or the small ones were to risky to lend to). Instead, corporations and banks have speculated in the stock and bond markets, and even borrowed more (through corporate bond issuance) given low interest rates, paying out increased shareholder dividends and buying back their own shares to boost prices. And now with the expectation of economic recovery, investors poured a record $58bn into stock funds, slashing their cash holdings and also piled $13.1bn into global bond funds while pulling $10.6bn from their cash piles.

So Fed and central bank money has not caused in inflation in the ’real economy’ which continued to crawl along at 2% a year or lower in real GDP growth, while the ‘fictitious’ economy exploded. It is there that inflation has taken place.

This is where the ’Austrian school’ of economics comes in. They see this wild expansion of credit leading to ‘malinvestment’ in the real economy and eventually to a credit crunch that hits the productive sectors of the ‘pure’ market economy. This view is expressed by that bastion of conservative economics, the Wall Street Journal. So while the Keynesians worry about overheating and inflation in true 1970s style, the Austrians worry about a credit/debt implosion.

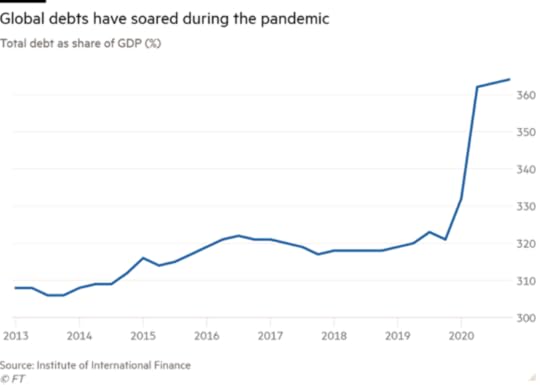

In contrast, the exponents of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) are quite happy about the Fed injections and the government stimulus programs. Modern Monetary Theory exponent Stephanie Kelton, author of The Deficit Myth, when asked whether she was worried about the stimulus bill causing inflation, said: “Do I think the proposed $1.9 trillion puts us at risk of demand-pull inflation? No. But at least we are centering inflation risk and not talking about running out of money. The terms of the debate have shifted.”

But neither the Keynesians, the Austrians nor the MMT exponents have it right theoretically, in my view. Yes, the Austrians are right that the expansions of credit money are driving up debt levels to proportions that threaten disaster if they should collapse. Yes, the MMT exponents are right that government spending per se, even if financed by central bank ‘printing’ of money will not cause inflation, per se. But what both schools ignore is what is happening to the productive sectors of the economy. If they do not recover then, fiscal stimulus won’t work and monetary stimulus will be ineffective too.

Take the proposed $1.9 trillion stimulus package. Even assuming the whole package is passed by Congress (increasingly unlikely) and then implemented, the stimulus is spread over years not months. Moreover, the paychecks to households will more likely end up being used to pay down debt, bump up savings and cover rent arrears and health care bills. There won’t be much left to go travelling, eat in restaurants and buy ‘discretionary’ items.

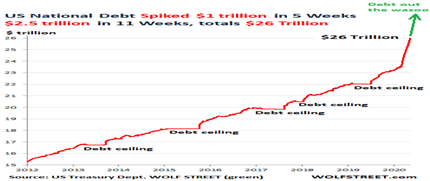

Moreover, as I have argued in many previous posts, the Keynesian view that government spending delivers a strong ‘multiplier’ effect on economic growth and employment is just not borne out by the evidence. Sure, government handouts to households and investment in infrastructure may generate a short boost to the economy. But raising government investment from 3% of GDP to 4% of GDP over five years or so cannot be decisive if business sector investment (about 15-20% of GDP) continues to stagnate. Indeed, as government debt grows to new highs (in the case of the US, to over 110% of GDP) even if interest rates stay low, interest costs to GDP for governments will rise and eat into funds available for productive spending. And with corporate debt also at record highs, there is no room for debt heavy corporations to cope with any reversal in low interest rates.

The problem is not inflationary ‘overheating’; it is whether the US economy can ever recover sufficiently to get close to ‘full employment’. The official US unemployment rate may be ‘only’ 6.7% but even the statistical authorities and the Fed admit that it’s probably more like 11-12% and even worse if you include the 2% of the labour force that has left the labour market altogether.

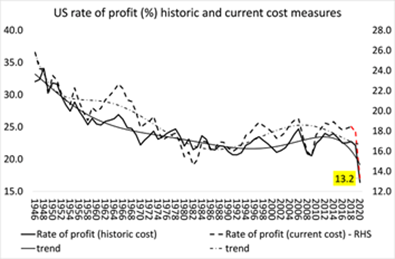

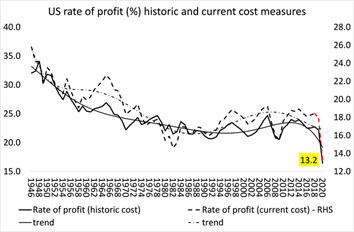

The problem is the profitability of the capitalist sector of the US economy. If that does not rise back to pre-pandemic levels at least (and that was near an all-time low), then investment will not return sufficiently to restore jobs, wages and spending levels.

Last year, G Carchedi and I developed a new Marxist approach to inflation. We have yet to publish our full analysis with evidence. But the gist of our theory is that inflation in modern capitalist economies has a tendency to fall because wages decline as a share of total value-added; and profits are squeezed by a rising organic composition of capital (ie more investment in machinery and technology relative to employees). This tendency can be countered by the monetary authorities boosting money supply so that money price of goods and services rise even though there is a tendency for the growth in the value of goods and services to fall.

During the year of the COVID, corporate profitability and profits fell sharply (excluding government bailouts and with the exception of big tech, big finance and now big pharma). Wage bills also fell (or to be more exact, wages paid to the many fell while some saw wages rise). These results were deflationary. But the central banks pumped in the money. US M2 money supply was up 40% in 2020. So US inflation, after dropping nearly to zero in the first half of 2020, moved back up to 1.5% by year end. Now if we assume that both profits and wages will improve by 5-10% this year and Fed injections continue to rise, then our model suggests that US inflation of goods and services will rise, perhaps to about 3% by end 2021 – pretty much where consumer expectations are going (see graph above).

That’s hardly ‘generation high’ inflation. And the view of Jay Powell and new Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen is “I can tell you we have the tools to deal with that (inflation) risk if it materializes.” Well, the US monetary and fiscal authorities may think they can control inflation (although the evidence is clear that they did not in the 1970s and have not controlled ‘disinflation’ in the last ten years). But they can do little to get the US economy onto a sustained strong pace of growth in GDP, investment and employment. So the US economy over the next few years is more likely to suffer from stagflation, than from inflationary ‘overheating’.

February 8, 2021

Ecuador: reversing the pandemic slump?

The leftist candidate Andrés Arauz took the lead in the first round of the presidential elections in Ecuador. Arauz won 31.5 per cent of the vote, putting him about 11 percentage points clear of his nearest rivals. It was unclear who Arauz would face in the run-off. Indigenous leader Yaku Pérez and Guillermo Lasso, a wealthy ex-banker, were in a technical tie for second place, with Perez on 20.04 per cent to Lasso’s 19.97 per cent. The second run-off round will be in April but if Arauz runs against the pro-business Lasso, he is likely to win; it’s less sure against Perez.

Ecuador is a small South American state with just 17m people right on the equator. Ecuador’s main industries are petroleum, food processing, textiles, wood products and chemicals. The oil sector accounts for about 50 percent of the country’s export earnings and about one-third of all tax revenues. The main oil company is the majority state-owned Petroecuador, which is still 37% owned by Texaco. Indeed, state-owned companies account for more than 80% of Ecuador’s oil production; the rest is produced by the multi-nationals: Repsol (Spain), Eni (Italy), Tecpetrol (Argentina’s state-owned company) and Andes Petroleum, which is a consortium of the China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC, 55% share) and the China Petrochemical Corporation (Sinopec, 45% share). Ecuador is also the world’s largest exporter of bananas and a major exporter of shrimp

The first round result is an important blow against the machinations of imperialism in the region. It is likely to end the rule of the last four years of pro-business policies adopted by President Lenin Moreno, deputy to former leftist President Rafael Correa. Moreno reneged on Correa’s polices on taking office and instead locked up Correa supporters and imposed fiscal austerity, privatisations and other pro-business measures.

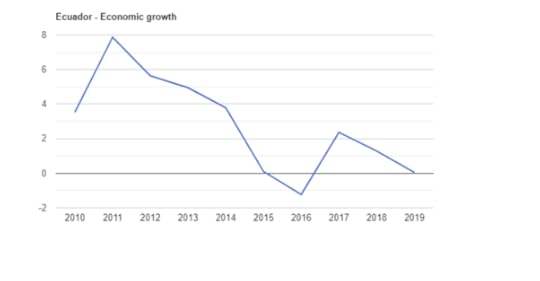

Between 2006 and 2014, under Correa, GDP growth had averaged 4.3%, driven by high oil prices and foreign investment. So Correa was able to raise minimum wages and social security benefits significantly, partly financed by higher taxes on the rich. But from 2015, GDP growth averaged just 0.6%.

As the Ecuador economy deteriorated, Moreno took an IMF loan accompanied by stringent austerity measures. The IMF had done the same thing as it did with the right-wing administration in Argentina, offering money in exchange for austerity and pro-business measures. This provoked a massive protest movement in 2019 that eventually forced Moreno rescind some of the terms of the IMF package. Moreno’s popularity plummeted and he decided not to stand in these elections.

Then came the COVID pandemic which hit Ecuador especially hard. The Moreno administration’s callous incompetence, the weak, privatised and underfunded health system and the desperate need of many ‘informal’ workers to keep their jobs, led to disaster. Ecuador is near the top of deaths per million globally. Indeed, Congress is impeaching health minister Juan Zavallos for mismanaging the COVID-19 vaccination program. The pandemic has paralyzed 70% of businesses and left 600,000 unemployed.

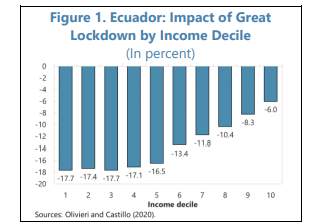

As elsewhere, the economic crisis due to the COVID-19 pandemic has disproportionally affected low income families, increased the poverty headcount and exacerbated income inequality. According to the World Bank, families in the bottom decile of the income distribution lost about 18 percent of their market income,while families in the top decile lost only a third of that.

Moreno’s solution to the slump was to take yet another IMF loan ($6.5bn), in return for the deregulation of the central bank and a hike in gasoline and diesel to world market prices. He also took a bilateral loan of $3.5bn from the Trump administration in return for privatising a major oil refinery and parts of the country’s electrical grid and to exclude China from its telecommunications development. Moreno also responded with ‘emergency’ $4bn spending cuts included liquidating the national airline and closing embassies.

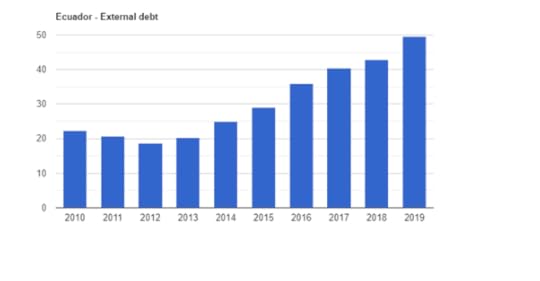

If Arauz wins in April, he will take over with foreign debt hitting $52bn.

Even after $7 billion in multilateral loans last year, Ecuador will need another $7.6 billion in new financing in 2021, according to an IMF report from December. And this assumes the country will agree to slash its government budget deficit to a target of $2.8 billion this year from $7.2 billion in 2020. Let me quote directly from the IMF on its conditions: “Discretionary spending cuts which would include wage restraint (0.6 ppts of GDP) and moderation of capital spending (0.7 ppts of GDP). Together with savings from the ongoing fuel subsidy reform and the roll-back of pandemic-related spending when the crisis subsides” And, “continued commitment to reducing deficits is needed to ensure sustainable public finances over the medium-term and lower the debt burden on future generations. Anchoring the medium-term path on the 57 percent of GDP debt limit in COPLAFIP entails a reduction of the NOPBS deficit by 5.5 ppt of GDP between 2019-2025, and of the overall NFPS balance by 5.3 ppt. Achieving these ambitious, yet realistic, goals requires a combination of a progressive tax reform— with permanent revenue yield of 2½ percent of GDP from 2022—and sustained expenditure rationalization.”

To achieve these targets, the IMF wants VAT hiked and measures to make the labour market ‘more flexible’ ie “maintaining the flexibility provided by those measures, such as shorter work weeks, more flexible shift and remote work arrangements, could support the labour market and the recovery.”

But Arauz says that he will not carry out the terms of the IMF package negotiated by Moreno. Instead, he wants to boost growth with a big rise in public spending, higher taxes and capital controls to stop money leaving the country. Arauz reckons Ecuador can ‘grow’ its way out the crisis rather than adopt austerity which he reckons “is absolutely counter-productive for Ecuador’s growth and development needs”. Rather than reduce the government budget deficit with a fiscal adjustment of 3% of GDP, Arauz aims to raise public spending by up to 1.5% of GDP with a major public works programme and put an end to privatisation.

How will this be done? First, Arauz proposes a wealth tax. And second, he has suggested raising the tax on taking currency out of the country to as high as 27%. Already wealthy Ecuadorians have spirited $30bn outside the country. In contrast, the pro-business Lasso wants to phase out the levy, which currently stands at 5%. And third, Arauz proposes central bank financing of government spending – in other words, ‘printing money’ – MMT-style.

Will these policies work? The new president will have to address an economy that has contracted between 10-12%, a debt that is equivalent to about 60% of GDP (high by emerging economy standards) and a poverty rate of around 35%. Income and wealth inequality remains very high:10% of the richest population has 42.5% of income, while 10% of the poor has only 0.6% of income.

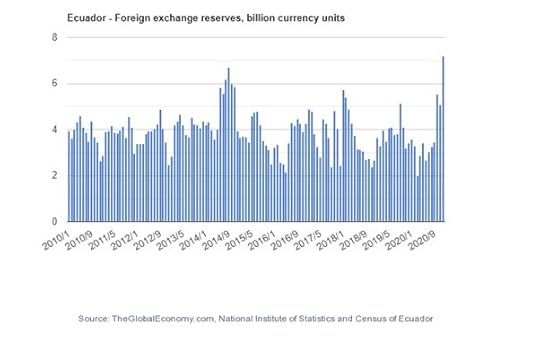

And there are big obstacles to recovery. The government cannot devalue the currency to make exports cheaper because Ecuador has no national currency. It is a dollar economy. That means if the central bank is to fund government spending by buying government bonds or crediting government accounts, because the government does not control the unit of account, dollar reserves will have to be run down, although there is some room here as FX reserves are at a record high as the dollar has weakened. And Arauz plans to obtain loans from China to replace IMF funding.

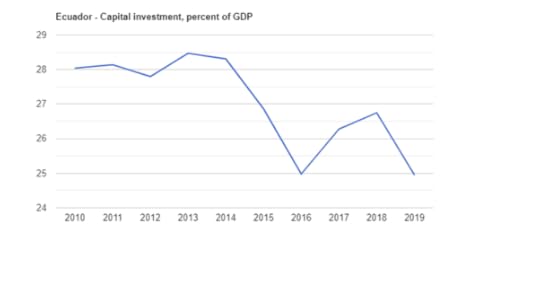

The major obstacle will be the multi-nationals and the business sector in Ecuador. Basically they have stopped investing since 2014.

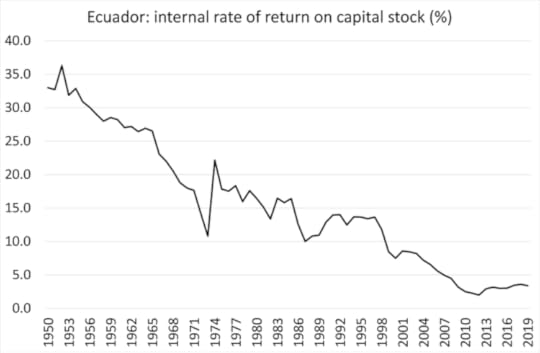

That’s partly because of the drop in energy prices but also because it seems that investing for profit in Ecuador is not promising. Energy and resources industries are highly capital-intensive, so in Marxist terms, the organic composition of capital rises significantly over time. This drives down the profitability of future investment, which has especially been the case in Ecuador since the so-called emerging market crisis of 1998. Only slowing down investment since 2014 has stopped profitability falling further.

So there is no incentive for the business sector to invest, particularly if oil prices stay low. And over the longer term, the global fossil fuel industry faces serious decline.

Unless energy prices make a sharp recovery and/or the world economy leaps back in the next year or so, Arauz’s measures may well fall short of restoring growth and reversing the hit to working class incomes from Moreno’s policies and the pandemic.

February 2, 2021

The mainstream: meeting the historic challenges?

Recently, newly confirmed US Treasury secretary and former Fed chief, Janet Yellen, spelt out the challenges facing US capitalism in a letter to her new staff. She said: “the current crisis is very different from 2008. But the scale is as big, if not bigger. The pandemic has wrought wholesale devastation on the economy. Entire industries have paused their work. Sixteen million Americans are still relying on unemployment insurance. Food bank shelves are going empty.” That’s now; but ahead, Yellen says that there were “four historic crises: COVID-19 is one. But in addition to the pandemic, the country is also facing a climate crisis, a crisis of systemic racism, and an economic crisis that has been building for fifty years. “

She did not spell out what this 50-year crisis was. But she was confident that mainstream economics can find the solutions to these crises. “Economics isn’t just something you find in textbook. Nor is it simply a collection of theories. Indeed, the reason I went from academia to government is because I believe economic policy can be a potent tool to improve society. We can – and should – use it to address inequality, racism, and climate change. I still try to see my science – the science of economics – the way my father saw his: as a means to help people.”

These are fine words. But is mainstream economics really designed to ‘help people’ improve their lives and livelihoods? Indeed, is mainstream economics really offering a scientific analysis of modern economies that can lead to policies that can solve the ‘four historic challenges’ that Yellen outlines?

The failure of mainstream economics to forecast, explain or deal with the global financial crash and the ensuing Great Recession of 2008-9 is well documented – indeed see my paper here. That hardly backs up Yellen’s claims.

Mainstream economics cannot deliver even on its own terms because it makes two basic assumptions that are not based on reality; one in so-called ‘microeconomics’ and one in so-called ‘macroeconomics’. As a result, mainstream falls down as a scientific analysis of modern (capitalist) economies.

First, there is utility theory and marginalism – and the resultant adoption of general equilibrium theory. Where does ‘wealth’ come from in society and how do we measure it? The classical economists, Adam Smith, David Ricardo etc recognised that there was only one reliable and universal measure of value: the amount of labour (hours) that is expended to produce goods and services. But this labour theory of value was replaced in the mid-19th century by utility theory, or more precisely, marginal utility theory.

This became the dominant explanation for value. As Engels remarked: “The fashionable theory just now here is that of Stanley Jevons, according to which value is determined by utility and on the other hand by the limit of supply (i.e. the cost of production), which is merely a confused and circuitous way of saying that value is determined by supply and demand. Vulgar Economy everywhere”. But marginal utility theory quickly became untenable even in mainstream circles because subjective value (ie every individual values something differently according to their inclination or circumstance) cannot be measured and aggregated, so the psychological foundation of marginal utility was soon given up. For more on the fallacious assumptions of mainstream value theory, see Steve Keen’s excellent book, Debunking economics, or more recently, Ben Fine’s critique of both micro and macroeconomics.

Engels called mainstream economics ‘vulgar’ because it was no longer an objective scientific analysis of economies but had become an ideological justification for capitalism. As Fred Moseley has explained, “marginal productivity theory provides crucial ideological support for capitalism, in that it justifies the profit of capitalists, by arguing that profit is produced by the capital goods owned by capitalists. All is fair in capitalism. There is no exploitation of workers. In general, everyone receives an income that is equal to their contribution to production.” In contrast, “The main alternative theory of profit is Marx’s theory and the conclusions of Marx’s theory (exploitation of workers, fundamental conflicts between workers and capitalists, recurring depressions, etc.) are too subversive to be acceptable by the mainstream. But these are ideological reasons, not scientific reasons. If the choice between Marx’s theory and marginal productivity theory were made strictly on the basis of the standard scientific criteria of logical consistency and empirical explanatory power, Marx’s theory would win hands down.”

The ultimate logical result of this vulgar economics is general equilibrium theory, where it is argued that modern economies tend towards equilibrium and harmony. The founder of general equilibrium theory, Leon Walras, characterised a market economy as like a giant pool of water. Sometimes a rock would be thrown into the pool, causing ripples across it. But eventually, the ripples would die out and the pool would be tranquil again. Supply might exceed demand in a market through some shock, but eventually the market would adjust to bring supply and demand into equilibrium.

Walras was well aware that his theory was an ideological defence of capitalism. As his father wrote to him in 1859, when Marx was preparing Capital, “I totally approve of your plan of work to stay within the least offensive limits as regard property owners. It is necessary to do political economy as one would do acoustics or mechanics.” More recently, Nobel prize winner Esther Duflo gave a speech in 2017 to the American Economics Association in which she reckoned economists should give up on the big ideas and instead just solve problems like plumbers “lay the pipes and fix the leaks”.

But do economies and markets really tend to equilibrium, if occasionally disrupted by ‘shocks’? We only have to look at the gyrations in the stock markets of the world this week to doubt that. Actually, modern economies are more like oceans with rolling waves (booms and slumps), with tides pulled by the gravity (profit) of the moon and storms (crashes) from the forces of the weather. There is no tranquility or equilibrium but continual, turbulent movement. Marxist economics aims to examine the dynamic ‘laws of motion’ over time in modern capitalism; in contrast to mainstream economics where time stands still and any ‘disturbances’ are caused by ‘shocks’ external to ‘free’ markets.

Of course, some mainstream economists admit that marginal utility and general equilibrium theory is nonsense. And occasionally some physicists of the ‘natural sciences’ attack the assumptions of mainstream economics. The latest critic is a British physicist Ole Peters who claims the Everything We’ve Learned About Modern Economic Theory Is Wrong. What’s wrong is that mainstream economic models assume something called “ergodicity.” That is the average of all possible outcomes of a given situation informs how any one person might experience it.

Peters takes aim at mainstream utility theory, which argues that when we make decisions, we conduct a cost-benefit analysis and try to choose the option that maximizes our wealth. The problem, Peters says, is this fails to predict how humans actually behave because the math is flawed. Expected utility is calculated as an average of all possible outcomes for a given event. What this misses is how a single outlier can, in effect, skew perceptions. Or put another way, what you might expect on average has little resemblance to what most people experience. His solution is to borrow math commonly used in thermodynamics to model outcomes using the ‘correct average’.

Peters is saying that reality operates more often like ‘power laws’, where far from markets, wealth, employment etc tending towards the average, or towards the equilibrium, Walras-style; instead, inequality can increase to extremes, unemployment can rise not fall etc. Outliers in the statistics can become decisive in their impact.

But it does not take us very far just to recognise uncertainty and chance and feed that into some mathematical model. We need to base economic ‘models’ on the reality of capitalist production, namely the exploitation of labour for profit and the resultant regular and recurring crises in production and investment ie the laws of motion of capitalism. Marxist economist of the early 20th century, Henryk Grossman perceptively exposed the failure of mainstream theories which are based on static analysis. Capitalism is not gradually moving on (with occasional shocks) in a generally harmonious way towards superabundance and a leisure society where toil ceases – on the contrary it is increasingly driven by crises, inequality and destruction of the planet.

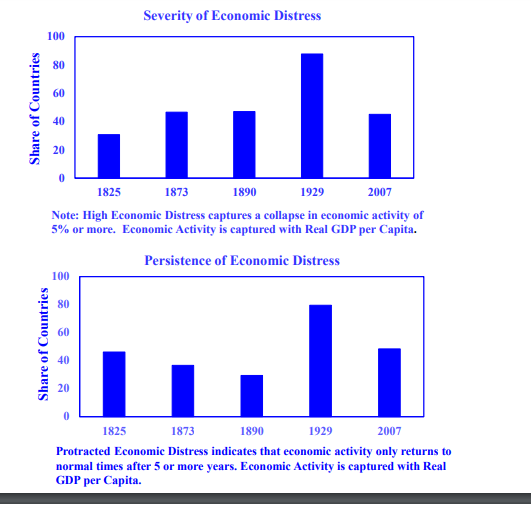

Instead, mainstream economics just invents possible exogenous causes or ‘shocks’ to explain crises because it does not want to admit that crises could be endogenous. The Great Recession of 2008-9 was ‘a chance in a million’or an ‘unexpected shock’, or a ‘black swan, the unknown unknown, that perhaps requires a new mathematical model to account for these shocks. Similarly, the COVID-19 pandemic is apparently an unforeseen exogenous ‘shock’, not a well forecast consequence of capitalism’s drive for profits from expansion into remote areas of the world where these dangerous pathogens reside. But the mainstream does not require or want a theory of endogenous causes of crises.

At the level of macroeconomics, modern Keynesian theory has also been found wanting. Modern Keynesianism (or ‘bastard Keynesianism’ as Joan Robinson called it) bases its analysis of crises in capitalism on ‘shocks’ to the equilibrium and uses Dynamic Stochastic General Equilibrium (DGSE) models to analyse the impact of these ‘shocks’.

Among others, Keynesian economic journalist Martin Sandbu has been running a little campaign against the DSGE approach. There is “little doubt that mainstream macroeconomics is in deep need of reform.” He says: “the question is how, and whether the standard approach, DSGE modelling, can be sufficiently improved or should be jettisoned altogether.” As Sandbu says, “DSGE macroeconomics does not really allow for the large-scale financial panic we saw in 2008, nor for some of the main contending explanations for the slow recovery and a level of economic activity that remains far below the pre-crisis trend.” Sandbu wants to plough on with “a more expansive and liberal form of DSGE”.

Recently he has praised the idea of so-called multiple equilibria as a standard feature of their core mainstream macro model ie “allowing that there are several different self-reinforcing states the economy can fall into, not just a single equilibrium around which it fluctuates. But with multiple equilibria, there is no single central tendency. If anything, there are several, and while one can give probability distributions around the precise outcome in each equilibrium, predicting in which equilibrium the economy will find itself is a different beast altogether.” Sanbu puts up this multiple equilibria approach as a method of getting better results from economics: “it becomes clear that by far the most important policy question is equilibrium selection: how to get the economy out of a self-reinforcing bad state, or prevent disruptions that tip it out of a good state.” But that sounds little different from general equilibrium models. And even worse, if there really are ‘multiple equilibria’ in modern economies then, says Sandbu, it “is something economists are not well-equipped to advise on.”

If that is so, then we cannot expect mainstream economics to meet the four historic challenges that Janet Yellen reckons capitalism faces. What were they again? Dealing with future pandemics; solving the climate crisis; ending inequality and racism; and the undefined 50-year crisis of capitalism (which is presumably the regular and recurring turbulence in capitalist production for profit).

We can only hope that Janet Yellen’s speeches to financial institutions in Wall Street, which has earned her over $7m in the last few years, provided these bastions of capital the solutions to those historic challenges. But don’t hold your breath.

January 28, 2021

Stop the game – I want to get off!

‘Hedging’ used to be a way reducing the risk of selling or buying. Farmers waiting for their harvest to come in are uncertain about what price per bushel they will get at the market: will they get a price that makes them a profit and a living for next year or will they be made destitute? To reduce that risk, hedge companies offer to buy the harvest in advance at a fixed price. The farmer is guaranteed a price and income whatever the price per bushel at the time of going to market. The hedge fund takes the risk that it can make a profit by buying the harvest at a price below the eventual market price. In this way, ‘hedging’ can smooth out the volatility in prices, often very high in agricultural and mineral sectors.

But in financial markets, hedging and hedge funds take on a whole new function. It has become a game, with billions of other people’s money at stake, turning the market for goods and services into a casino for financial betting. In my previous post, I explained how what Marx and Engels called ‘fictitious capital’ (stocks and bonds) and their supposed value bore little relation to the real value of underlying earnings and assets of companies.

Financial hedging takes this one step even further away from real values, as hedge funds do not just buy or sell stocks rather than invest in productive capital. Now they bet on which way the price of any stock will go. In ‘short selling’, a hedge fund borrows shares in a company from other investors (for a fee) and sells the shares on the market at, for example, $10 each. Then it waits until they fall to $5 and then buys them back. The borrowed shares are returned to the original owner and the hedge fund pockets a profit.

Far from smoothing price changes, by betting on prices falling or rising, the hedge funds actually thrive on increased volatility. ‘Going long’ to drive up the price and ‘going short’ to drive down the price is the name of the game. And in doing so, ‘short sellers’ can actually drive companies into bankruptcy, with the loss of jobs and incomes for thousands.

In the year of COVID, while the ‘real economy’ collapsed, those with cash to spare and looking for a return (banks, pension funds, rich individuals) invested heavily in the stock market, often using borrowed money (at near zero rates of interest). And these big investors put much of their money into hedge funds and look to these so-called ‘smart people’ to make them a buck. And they have been doing so, big time.

But also in the year of the COVID, there were millions of people who have been working at home or have been furloughed sitting on savings that they cannot spend because of lockdowns and no travel. So many have linked up through social networks like Reddit to bet on the stock market.

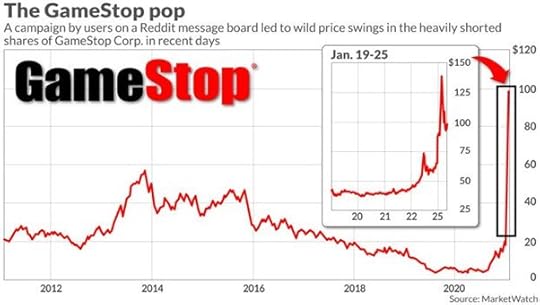

These small investors have recently started to combine and build up some firepower and to take on the big institutions in their gambling dens. Since the beginning of the year, a group of amateur traders, organised on Reddit, have been playing the market against major hedge funds, who had shorted shares for GameStop: a US-based video game retailer. This company had suffered badly during the year of the COVID and was expected to go bust. Hedge funds piled in to ‘short’ the stock.

But the small traders did the opposite and used their firepower to drive up the stock price, forcing the hedge funds, backed by the big banks and institutions, to buy back the shares at higher prices as the time ran out for their ‘short’ bets (they are fixed time contracts). As a result, several ‘shorting’ hedge funds took a huge loss ($13bn) and one fund had to be bailed out by its investors to the tune of $2.75 billion.

Wall Street is furious. The small investors have ‘rigged’ the market, they cry, threatening the value of your pension funds and putting banks in jeopardy. This is nonsense, of course. What it actually shows is that financial markets are ‘rigged’ by the big boys and it’s small investors who are usually the ones that get ‘shafted’ and swindled in this gambling den. As Marx said, the financial system “develops the motive of capitalist production”, namely “enrichment by exploitation of others’ labour, into the purest and most colossal system of gambling and swindling and restricts even more the already small number of exploiters of social wealth” (Marx 1981: 572).

Of course, in the current battle, the small investor will lose out in the end. Massachusetts state regulator William Galvin has already called on the New York Stock Exchange to suspend GameStop for 30 days to allow a cooling-off period. “This isn’t investing, this is gambling,” he said. No sweat! And already, small investors are seeing a hike in the charges and limits on their trades by brokers and market makers (the casino owners) to deter them from trading. And there is talk at the top of ‘regulating’ the market to stop investors ‘ganging up’ on the ‘legitimate’ institutions of Wall Street. The price of GameStop is now falling back.

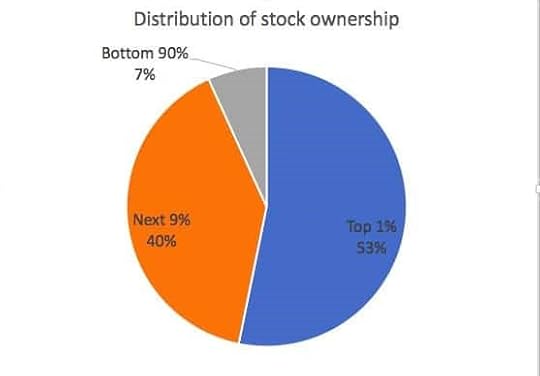

For working people all these shenanigans may appear irrelevant. After all, most working households have little or no shares at all. The top 1% of households owned 53% of US stock market wealth, with the top 10% owning 93%. The bottom 90% own only 7%. However, workers’ pensions and retirement accounts (if workers have them) are invested by private pension fund managers into financial assets (after deducting very nice commissions). So what savings working households do have are vulnerable to the gambling activities of the swindlers in the financial casino – as the global financial crash of 2007-8 showed.

What this little story of GameStop shows is that company and personal pension funds run by the ‘smart people’ are really a rip-off for working people. What is needed are state funded pensions not subject to the volatility of the financial game. The big hedge funds have been burnt in this latest skirmish by some small investors and they want to get these minions out of the game. What working people should want is to stop this game altogether.

January 25, 2021

Covid and fictitious capital

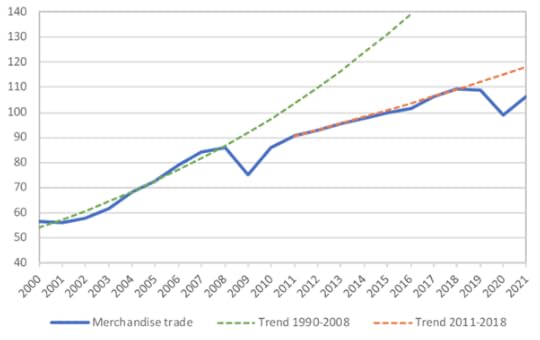

During the year of the COVID, output, investment and employment in nearly all the economies of the world plummeted, as lockdowns, social isolation and collapsing international trade contracted output and spending. And yet the opposite was the case for the stock and bond markets of the major economies. The US stock market indexes (along with others) ended 2020 at all-time highs. After the initial shock of the COVID pandemic and the ensuing lockdowns, when the US stock market indexes plunged by 40%, markets then made a dramatic recovery, eventually surpassing pre-pandemic levels.

It is clear why this happened. It was the injection of credit money into economies. The Federal Reserve and other major banks injected huge quantities of cash/credit into the banking system and even directly into corporations through the purchase of government bonds from the banks and corporate bonds; as well as through direct government-backed COVID loans to businesses. Interest rates on this credit fell towards zero and, with so-called ‘safe assets’ like government bonds, interest rates even went negative. Bond purchasers were paying governments interest in order to buy their paper!

Much of this credit largesse was not used to keep staff in pay and employment or to sustain corporate operations. Instead, the loans have been used as very cheap or near zero-cost borrowing to speculate in financial assets. What is called ‘margin debt’ measures how much of stock market purchases have been made by borrowing. The latest margin debt level is up 7.7% month-over-month and is at a record high.

Marx called financial assets, stocks and bonds, ‘fictitious capital’. Engels first composed this term in his early economic work, the Umrisse; and Marx developed it further in Capital Volume 3 (Chapters 25 and 29), where he defined it as the accumulated claims or legal titles, to future earnings in capitalist production; in other words, claims on ‘real’ capital, ie capital actually invested in physical means of production and workers; or money capital, cash funds being held. A company raises funds for investment etc by issuing stocks and/or bonds. The owners of the shares or bonds then have a claim on the future earnings of the company. There is a ‘secondary’ market for these claims, ie buying and selling these existing shares or bonds; a market for the circulation of these property rights.

Stocks and bonds do not function as real capital; they are merely a claim on future profits, so “the capital-value of such paper is…wholly illusory… The paper serves as title of ownership which represents this capital.” As Marx put it: “While the stocks of railways, mines, navigation companies, and the like, represent actual capital, namely, the capital invested and functioning in such enterprises, or the amount of money advanced by the stockholders for the purpose of being used as capital in such enterprises…; this capital does not exist twice, once as the capital-value of titles of ownership (stocks) on the one hand and on the other hand as the actual capital invested, or to be invested, in those enterprises.” The capital “exists only in the latter form“, while the stock or share “is merely a title of ownership to a corresponding portion of the surplus-value to be realised by it”.

Investors (speculators) in financial markets buy and sell these financial assets, driving prices up and down. If cash (liquidity) is flush, share and bond prices can rocket, while banks and financial institutions invent ever new financial ‘instruments’ to invest in. As Marx put it: “With the development of interest-bearing capital and the credit system, all capital seems to double itself, and sometimes treble itself, by the various modes in which the same capital, or perhaps even the same claim on a debt, appears in different forms in different hands. The greater portion of this ‘money-capital’ is purely fictitious.”

The central banks become key drivers of any financial asset boom Again, as Marx put it some 150 years ago, “Inasmuch as the Bank issues notes that are not backed by the metal reserve in its vaults, it creates tokens of value that are not only means of circulation, but also forms additional – even if fictitious – capital for it to the nominal value of these fiduciary notes, and this extra capital yields it an extra profit.” The creation or ‘printing’ of money by central banks provides the liquidity for speculation in the stock and bond markets – as we have seen in the year of the COVID.

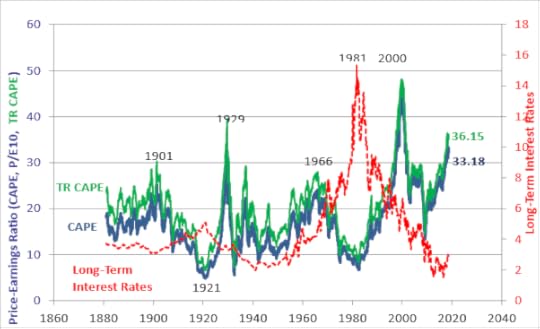

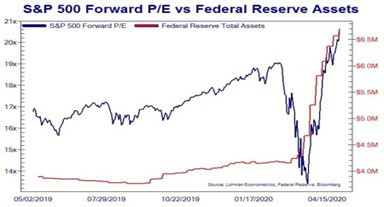

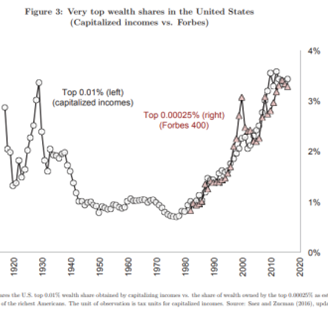

Marx reckoned that what drives stock market prices is the difference between interest rates and the overall rate of profit. As profitability fel in 2020, what kept stock market prices rising was the very low level of long-term interest rates, deliberately engendered by central banks like the Federal Reserve around the world. ‘Quantitative easing’ (buying financial assets with credit injections), has doubled and tripled in this year of the COVID. So the gap between returns on investing in the stock market and the cost of borrowing has been maintained.

But here is the rub. The share price of a company must eventually bear some relation to the profits made or the profits likely to be made over a period of time. Investors measure the value of a company by the share price divided by annual profits. If you add up all the shares issued by a company and multiply it by the share price, you get the ‘market capitalisation’ of the company — in other words what the market thinks the company is worth. This ‘market cap’ can be ten, 20, 30 or even more times annual earnings. If a company’s market cap is 20 times earnings and you bought its shares, you assume that you would have to wait to reap 20 years of profits in dividends to match the price of your investment.

You can see from this (CAPE Shiller) graph below that, as long term interest rates have fallen, the market cap price of corporate shares relative to profits (earnings) has risen. Currently, it is at levels only surpassed in 1929 and during the dot.com boom of 2000.

If profits drive the share prices of companies, then we would expect that, when the rate of profit in capitalism rises or falls, so would stock prices. To measure that, we can get a sort of average price of all the company shares on a stock market by using a basket of share prices from a range of companies and index it. That gives us a stock market index.

So does the stock market price index move up and down with the rate of profit under capitalism? The answer is that it does, over the longer term — namely over the length of the profit cycle, but that can be as long as 15-20 years. In the shorter term, the stock market cycle does not necessarily coincide with the profit cycle. Indeed, financial markets can reach extreme price levels relative to the underlying profits being engendered in an economy.

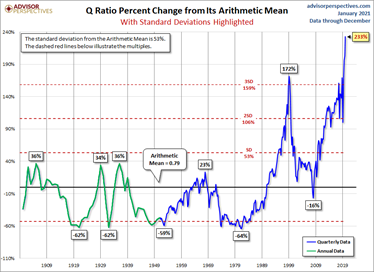

The most popular way of gauging how far the stock market is out of line with the real economy and profits in productive investment is by measuring the market capitalisation of companies against the accumulated real assets that companies have. This measure is called Tobin’s Q named after the leftist economist, James Tobin. It takes the ‘market capitalisation’ of the companies in the stock market (say, of the top 500 companies in what is called the S&P-500 index) and divides that by the replacement value of tangible assets accumulated by those companies. The replacement value is the price that companies would have to pay to replace all the tangible (and ‘intangible’?) assets that they own (plant, equipment, software etc).

For the last 100 years or so, the average mean Q Ratio is about 0.78. The Q ratio high was at a peak of the tech bubble in 2000 reaching 2.17 — or 174% above the historic average. The lows were in the slumps of 1921, 1932 and 1982 at around 0.28, or 62% below average. But in this year of the COVID, Tobin’s Q has reached 233% above the mean – a new record.

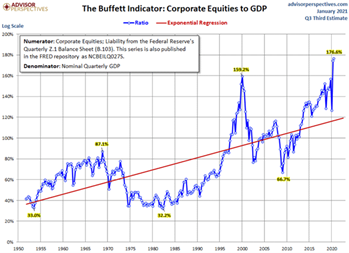

Another useful measure of the value of the stock market relative to the real economy is the Buffett index. Named after famed billionaire financial investor who uses this index as his guide, it measures the money value of all stocks and shares against the current national output in the real economy (GDP). Again, this shows that in the year of the COVID, the stock market has reached record high relative to the ‘real economy’.

Indeed, financial speculators remain in total ‘euphoria’ as they continue to expect central banks to plough yet more loans and cash into the banks and institutions, along with a likely subsidence of the COVID pandemic in 2021 as vaccinations are distributed. The belief is that corporate earnings will recover sharply to justify the current record highs in stock prices.

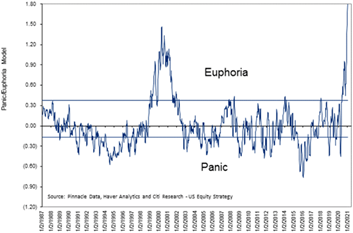

Citi Research has a “Euphoria/Panic” index that combines a bunch of market mood indicators. Since 1987, the market has typically topped out when this index approached the Euphoria line. The two exceptions were in the turn-of-the-century technology boom, when it spent about three years in the euphoric zone, and right now.

This ‘euphoria’ index complements the views of the world’s most powerful investment bank, Goldman Sachs. Their experts forecast another 15% rise in the US stock market in 2021.

But as Marx explained, eventually investment in financial assets will have to come into line with earnings in the real economy. In the year of the COVID, profits in most corporations plunged by 25-30%.

Goldmans and other investor speculators seem convinced that profits will bounce back this year, to make sure that the price of fictitious capital does not turn out to be fictitious. But that seems unlikely. COVID-19 is not yet over and the vaccination distribution will take well into this year to reach levels of necessary so-called ‘herd immunity’, and that assumes the vaccines can also deal with the new COVID variants.

Moreover, the stock market boom of 2020 was really confined to just a few companies. In the year of the COVID, the S&P 500 index rose 18.4%, but the portfolio of FAAAM (Facebook, Alphabet, Amazon, Apple, Microsoft) plus Netflix rose 55%. The contribution of that latter group to the S&P 500’s growth was 14.35%. So the rest of the S&P companies gained only 4.05%.

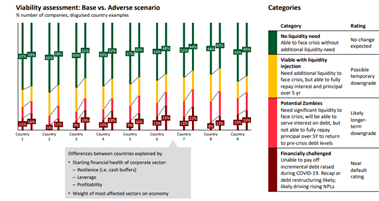

Most companies lost money in 2020. And there is a swathe of businesses, mostly outside the top 500, but not entirely, which are in deep trouble. Earnings are low or negative and even with the cost of borrowing near zero, these ‘zombie’ companies are not earning enough to cover even the interest on existing and new loans. These ‘financially challenged’ zombies constitute about 20% of companies in most economies.

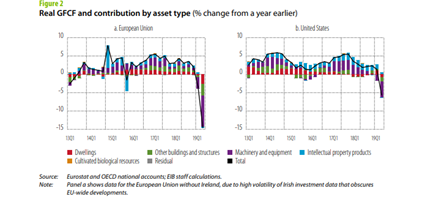

Even before the pandemic, the zombie companies were contributing to a significant slowdown in corporate investment levels. With so many companies in trouble, there is little prospect of a huge jump back in investment and earnings this year.

Central banks will go on providing yet more ‘liquidity’ for banks and corporations to speculate in financial markets. So fictitious capital will continue to expand – after all, as Engels first said, speculating in financial markets is a major counteracting factor to falling profitability in the ‘real economy’.

But all good things must come to an end. Probably in the second half of 2021, governments will attempt to rein in their fiscal spending and central banks will slow the pace of their largesse. Then the extreme levels of stock and bond prices relative to earnings and tangible capital are likely to reverse, like a yo-yo does when the string is pulled back to the reality of being fixed to a holder (real capital).

January 20, 2021

Biden’s four years

It’s inauguration day. There is a new president in the US, the most powerful capitalist economy and state in the world. Joe Biden’s four-year term begins today, as Donald Trump slinks off to his Florida estate and golf course, after saying that his “movement is just beginning”.

What is the state of the United States as Biden takes over? The COVID-19 pandemic has reaped huge damage on the lives and livelihoods of millions of Americans. Its impact has been far worse than it might have been for several reasons. First, the US government, just like the other governments, had done nothing to prepare for the COVID-19 pandemic. As previous posts have explained, governments had been warned that pathogens dangerous to human life for which there was no immunity were becoming more prevalent, leading to a wave of epidemics before COVID-19. But most governments did not spend on prevention (research into vaccinations) or on protection (robust health resources and testing and trace systems). On the contrary, governments had been cutting back on health spending, privatising and outsourcing it, and in the case of the US, operating a private health insurance system that left a sizeable minority of Americans with no protection at all, and the rest paying out huge premiums for health cover.

And in the US and other countries, like the UK, Sweden and Brazil, there was an open refusal of governments to recognise the deadly nature of the virus and to take action to save lives. For these governments, keeping businesses going, particularly big business, was more important. This attitude led to late lockdowns and social isolation measures, then ‘light’ lockdowns that did not suppress the spread of the virus ;and then too early relaxations, leading to a revival of the pandemic.

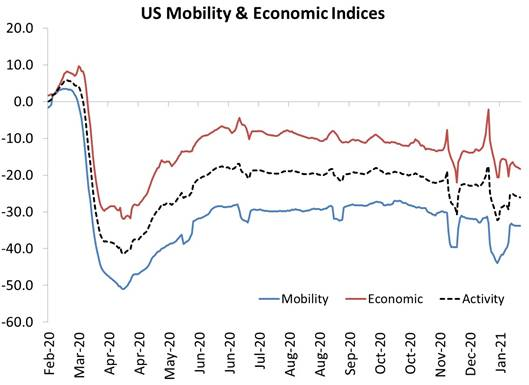

So as Biden takes his oath at the inauguration ceremony, Americans are still faced with near record levels of COVID cases and deaths. At the same time, economic activity and people mobility remains well below pre-pandemic levels. According to the latest Google mobility report, US economic activity is still some 20-25% below where it was this time last year.

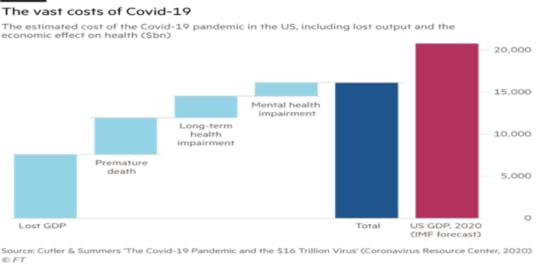

Indeed, the economic cost of the pandemic during 2020 has been equivalent to 80% of US 2020 real GDP output, if you take into account the lost GDP, premature deaths, long-term health impairment and mental health.

So the outgoing US government (like many others) failed to save lives and also failed to save livelihoods. And this is particularly the case for the lowest paid, often unable to work from home, forced to work in dangerous conditions or being laid off; and that mainly means, black and other ethnic minorities, women and young people.

Overall, the US economy has shrunk by about 4-5% in 2020. That is the largest contraction since the early 1930s – or 90 years ago! Employment has fallen by over 25m, with millions now on emergency benefits, unemployment benefits or given up. Swathes of American businesses, mainly in the services sector but not just there, have been closed and will not return as the economy recovers (once the vaccinations reach enough Americans).

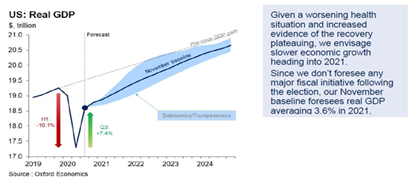

All the evidence suggests that there has been permanent ‘scarring’ to the economy in employment, investment and incomes. Most studies suggest that the US economy in GDP terms will not return to the levels of 2019 before the end of 2022 at the earliest, and certainly not to the levels that GDP would have reached if there had been no pandemic slump.

So there will be no V-shaped recovery as was hoped – indeed of the major economies globally, only China is achieving that. Instead, there is what I have called a ‘reverse square root’ recovery where output falls but then does not recover to the same trajectory of economic growth that was there before. That output is lost forever, as the forecast for the US from Oxford Economics below shows.

But what about the economic policy actions adopted during the pandemic slump under the Trump administration and those that are planned by Biden during 2021 and beyond? Will they not restore the US economy to ‘business as usual’?

In the last year, there has been the biggest injection in history of credit into the monetary system through Federal Reserve Bank purchases of government and corporate debt and loans to businesses. The Fed’s balance sheet has nearly doubled in one year, to reach nearly 40% of US GDP and is set to rise further this year. Has it saved businesses from bankruptcy? Well, yes to some extent, but mainly the large travel, auto and fossil fuel industries, while many small businesses are going bust.

With interest rates more or less at zero and the Fed pumping yet more credit into the coffers of banks and businesses, will this largesse help to get the US economy going at a fast pace in 2021? Well, the evidence is against it. The history of what is called ‘quantitative easing’ (where it is the quantity of credit money that is injected, not reducing cost of this money in interest, that matters) has proved that it fails to restore the productive sectors of the capitalist economy. As empirical study concluded: “output and inflation, in contrast with some previous studies, show an insignificant impact providing evidence of the limitations of the central bank’s programmes” and “the reason for the negligible economic stimulus of QE is that the money injected funded financial asset price growth more than consumption and investments.” balatti17.pdf (free.fr)

Indeed, what has happened to all these credit injections is that they have been used by banks and big businesses to speculate in the stock and bond markets rather than to pay wages, preserve jobs or raise investment. After the initial panic of the pandemic in March, the US stock market has gone on an unparalleled binge.

It is now at all-time highs and, relative to earnings and productive assets, is at extreme levels. Yet with more Fed support to come, financial markets may well go rolling on up for a while longer. So all monetary policy has done is to keep businesses on life support, while boosting the wealth of the very rich.

The ineffectiveness of monetary policy to restore the US economy has meant that mainstream economists are “all Keynesians now”. The merits of increased government spending while running ‘emergency’ budget deficits are proclaimed by the IMF, the World Bank, the OECD and of course, the incoming Biden administration. Janet Yellen, the former Federal Reserve chief under Obama, is taking over as Treasury Secretary under Biden. Yellen made it clear in her testimony to US Congress where she stood. “We need to act big” because “economists don’t always agree, but I think there is a consensus now: without further action, we risk a longer, more painful recession now – and long-term scarring of the economy later.”

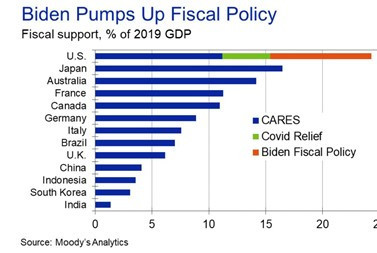

Thus we have Biden’s new fiscal stimulus package to come in 2021. The main elements of Biden’s stimulus plan include payments to individuals of up to $1,400 each; more aid to state and local governments; the extension of emergency jobless benefits of $400 per week; funds to help schools and universities to reopen; financing of vaccinations, testing and tracing; more child tax credit; and raising the minimum wage.

At first sight this looks big, to use Yellen’s words, taking the total fiscal injection up to 25% of GDP. However, it is not really. First, many of these measures may not get through the US Congress despite the narrow majority that the Democrats now hold. Also, even this level of fiscal support is way short of what is needed keep 25m Americans from destitution or for local governments not to be forced into jobs and spending cuts to ‘balance their books’. Moreover, raising the minimum wage to $15 an hour would still mean that those on the minimum would be well behind average median wage. And Biden is not intending to implement this rise immediately but spread it over time.