Michael Roberts's Blog, page 15

February 22, 2024

Ukraine – two years on, no end in sight

After almost two full years of war, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has caused staggering losses to Ukraine’s people and economy. Ukraine’s GDP fell by 40% in 2022. There was a small recovery in 2023, but an additional 7.1 million Ukrainians now live in poverty.

There are various estimates of the number of Ukrainian civilians and military casualties after two years of war. The UN estimates about 10,400 civilian deaths with another 19,000 wounded. The military casualties are even more difficult to estimate – but probably about 70,000 soldiers killed and another 100,000 wounded. Russian military casualties are about the same. Millions have fled abroad and many more millions have been displaced from their homes within Ukraine.

When I reviewed the economic and social state of Ukraine and Russia one year into war in 2023, I concluded that both sides would be able to continue this war for years, if necessary. For Ukraine, that depended on getting aid (civil and military) from the West. For Russia, it meant continuing to obtain sufficient export revenues from its energy and resources commodities.

Russia could not rely on foreign financing to fund the war, but I reckoned that it could carry on in the face of economic sanctions from the West, as long as its energy revenues and its FX reserves were not depleted too much; or its domestic economy did not contract so much that it caused social unrest within Russia. And so it has proved. The Russian economy is stable, the war effort is being sustained and Putin will win a new presidential term next month (and would probably could have done so even without killing off all potential opponents).

Ukraine is still totally dependent on support from the West. This year it needs at least $40bn in order to sustain government services, support its population and maintain production. It is relying on the EU for such civil funding, while relying on the US for all its military funding – a straight ‘division of labour’.

In addition, the IMF and World Bank have offered monetary assistance but, in this case, Ukraine has to show it has ‘sustainability’, ie it is able at some point to pay back any loans. So if the bilateral loans from the US and EU countries (and it is mainly loans, not outright aid) do not materialise, then the IMF cannot extend its lending programme.

Moreover, Ukraine also needs to find a way to restructure about $20 billion in international debt this year with sovereign bondholders whose agreed two-year payment freeze made in August 2022 will be up soon.

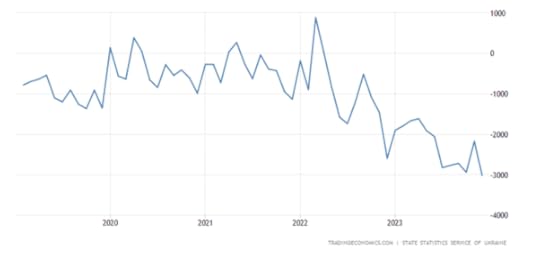

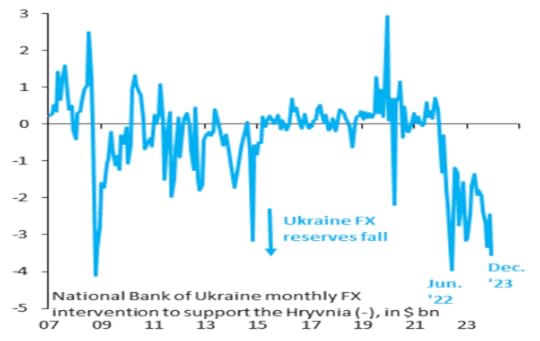

And it is a struggle. Despite some recovery in exports, Ukraine’s balance of trade deficit continues to worsen.

That means that the foreign exchange coffers to buy imports disappear nearly as fast as they are supplemented by Western aid.

Ukraine Finance Minister Serhiy Marchenko said the government hoped to secure foreign financing in full in 2024, but if the war lasted longer, he added ominously that “the scenario will include the need to adapt to new conditions.”

Presumably that would mean either cuts in services or getting Ukraine’s central bank to just ‘print’ money. The former would mean more poverty and a further contraction in living standards; the latter would mean a renewal of an inflationary spiral into double-digits (inflation had fallen back in 2023). It seems that the Ukrainian government expects either the loans to come through or the war to end in 2024. The former may happen, the latter is unlikely.

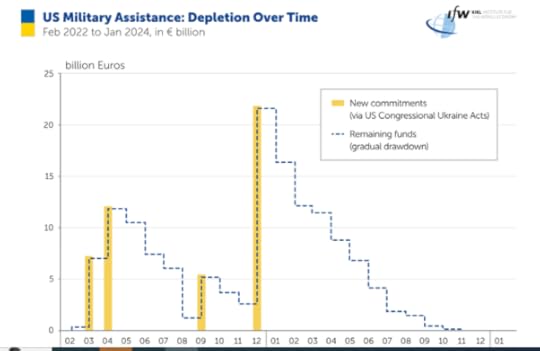

But will the aid to drip feed Ukraine’s economy in 2024 come through? Europe is delivering funds for civilian activities, but it’s up to the US to deliver funds for military activities. The last remaining funds for US military assistance were depleted by end-2023. In total the US has allocated around €43 billion in military aid since February 2022, which is about €2 billion per month.

US funding for the Ukraine military remains unclear as the US Congress is divided over providing further military aid. The upcoming presidential election, with the possibility of the return of Trump in 2025, poses the major uncertainty.

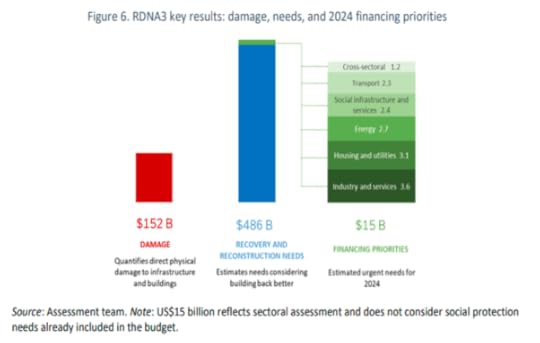

That brings us back to what will happen to Ukraine’s economy, if and when the war with Russia comes to an end. According to the latest estimate of the World Bank, Ukraine will need $486bn over the next ten years to recover and rebuild – assuming the war ends this year. That’s nearly three times its current GDP.

Direct damages from the war have now reached almost $152 billion, with about 2 million housing units – about 10% of the total housing stock of Ukraine – either damaged or destroyed, as well as 8,400 km (5,220 miles) of motorways, highways, and other national roads, and nearly 300 bridges. As of December 2023, about 5.9 million Ukrainians remained displaced outside of the country and internally displaced persons were around 3.7 million.

And as I explained in a previous post back in mid-2022, already what is left of Ukraine’s resources (those not annexed by Russia) are being sold off to Western companies. For example, the sale of land to foreigners was approved in 2021 under IMF pressure and now the food monopolies Cargill, Monsanto and Dupont own 40% of Ukraine’s arable land. GMA-Monsanto Corporation owns 78% of the land fund of Sumy region, 56% of Chernihiv, 59% of Kherson and 47% of Mykolaiv region.

Overall, 28% of Ukraine’s arable land is owned by a mixture of Ukrainian oligarchs, European and North American corporations, as well as the sovereign wealth fund of Saudi Arabia. Nestle has invested $46 million in a new facility in western Volyn region while German drugs-to-pesticides giant Bayer plans to invest 60 million euros in corn seed production in central Zhytomyr region.

MHP, Ukraine’s biggest poultry company, is owned by a former adviser to Ukrainian president Poroshenko. MHP has received more than one-fifth of all the lending from the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) in the past two years. MHP employs 28,000 people and controls about 360,000 hectares of land in Ukraine — an area bigger than EU member Luxembourg. It had $2.64bn in revenues in 2022.

The Ukrainian government is committed to a ‘free market’ solution for the post-war economy that would include further rounds of labour-market deregulation below even EU minimum labour standards i.e sweat shop conditions; and cuts in corporate and income taxes to the bone; along with full privatisation of remaining state assets. However, the pressures of a war economy have forced the government to put these policies on the back burner for now, with military demands dominating.

What about Russia? After two years since the invasion, it is clear that the sanctions introduced by Western governments to weaken Russia’s ability to continue the invasion have failed. Russia’s economy is growing, even if that growth is mainly based on production for the military sector. Energy prices and export revenues have remained strong with sales to third parties like China and India comfortably replacing export losses to Europe. According to official figures, 49 percent of European exports to Russia and 58 percent of Russian imports are under sanctions, but the Russian economy still grew 5% in 2023 and will grow further this year.

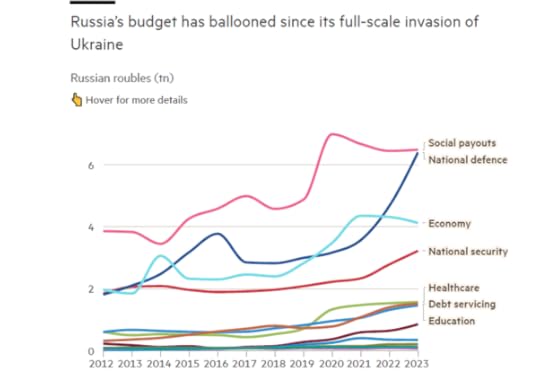

Yes, $330bn of Russia’s FX reserves have been seized by the West, but Russia’s FX coffers remain more than sufficient. The cost of pursuing the war remains huge, with 40% of the government budget, but funding is still sufficient without resorting to money printing or to cutting civilian services.

In many areas, Russia is self-sufficient in critical commodities like oil, natural gas, and wheat, which has helped it weather the years of sanctions. Russia can also supply itself with most of its defence needs, even for sophisticated weapons. So it can continue this war for many more years, even if that damages the long-term potential of the economy.

In contrast to Ukraine, the Putin regime aims for a more state-controlled economy, where the big companies work in close coordination with Putin’s cronies. But similar to Ukraine, corruption between oligarchs and government will continue. Meanwhile the war grinds on.

February 13, 2024

Indonesia: still in the shadow of Suharto

Indonesians will elect the country’s next president tomorrow (14 February). Indonesia is the world’s fourth-most-populous nation with over 280m people living in a myriad of archipeligo islands spanning Asia to Australia. More than 204 million people are eligible to cast ballots in the world’s largest direct presidential vote, the fifth since the Southeast Asian country began democratic reforms in 1998. More than half of those eligible to vote are aged between 17 and 40 and about a third are under 30.

The winner will succeed President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo, who is constitutionally barred from seeking a third term and will step down in October after ten years in office. Defence Minister Prabowo Subianto, 72, is the front-runner in the presidential race. Prabowo is a former general with the army’s special command and former son-in-law of the late Indonesian military dictator President Suharto.

Ganjar Pranowo, 55, is a former governor of Central Java and a senior politician with the ruling Indonesian Democratic Party of Struggle (PDI-P), to which Jokowi currently belongs. The other candidate, Anies Baswedan, 54, is the former governor of Jakarta. He is a former university rector and political scientist. During Jokowi’s first term he served as education minister. However, after being ousted in a cabinet reshuffle, he joined the opposition. Anies paints himself as an alternative to Prabowo and Ganjar as he seeks a break from Jokowi’s policies.

Final opinion polls by major pollsters show support for Prabowo exceeds 50%. So he is the most likely winner. If no candidate gets 50% in the first round, there will be a second round run-off between the top two. All three candidates demonstrate that Indonesia’s 21st century democracy is still dominated by the political, business and military leaders who built their fortunes during thirty-two years of Suharto’s authoritarian rule.

Indonesia gained independence from Dutch imperialism after a long hard fought war. The nationalist Sukarno became its president, leaning on the support of the independence fighters who were mainly led by the Communist party based in the countryside. In 1965, in the midst of an economic crisis, military chief Suharto came to power through a coup in that ousted Sukarno. Suharto’s takeover led to a bloodbath in which up to 1 million Communists and nationalists were killed and another 1.5 million imprisoned. The CIA described the purge as “one of the worst mass murders of the 20th century”. Suharto’s coup was even worse than Pinochet’s military coup over Chile’s President Allende nearly a decade later in 1973.

In 1975 Suharto also launched a bloody invasion of part of one of the archipelago islands, previously a Portuguese colony, East Timor, to crush its independence movement and annex it as Indonesia’s 27th province (the other half of the island, West Timor, was already part of Indonesia after independence from the Dutch). An estimated 200,000 local people died during the occupation that lasted until 1999, when finally, independence was achieved for East Timor when Suharto was removed from power.

Indonesia’s economy has rested on its oil and gas reserves and the produce of its land. In the early 1980s, the Suharto government responded to a fall in oil exports during the early 1980s oil crisis by trying to shift the basis of the economy to cheap labour-intensive manufacturing. Foreign investors came in to take advantage of Indonesia’s low wages.

It was under Suharto that the country’s modern oligarchs first emerged and his reign was littered with examples of close friends and family obtaining preferential access to loans, concessions, import licences and state bail-outs. Aafter over three decades of his dictatorship, the Asian debt crisis of 1998 brought down the Suharto regime. In the face of growing public protests against his authoritarian rule, Suharto’s own military and political allies forced him to resign. Free elections were held within a year.

The biggest winner then was the Indonesian Democratic Party of Struggle (PDIP), led by Megawati, daughter of Sukarno. But Suharto’s Golkar party, led by regime loyalists from business and military backgrounds, and the Muslim United Development Party had sufficient support to block Megawati. Since then, all so-called parties of the democratic era have been led by Suharto-era businessmen and retired military generals. As only parties with at least 20 percent of seats in the parliament can field a candidate, that has ensured the continued political control of this elite.

Current president Joko Widodo was the only outsider to breach this clique. In 2014, voters and Megawati’s party backed him to end the control of Suharto cliques. Widodo soundly defeated Prabowo Subianto. But soon Widodo fitted into the existing ruling elite by bringing the oligarchs and politicians into his administration. He appointed Subianto as his defence minister and Subianto’s party joined the governing coalition, while Jokowi closed down the anti-Corruption Commission that was investigating Suharto’s supporters.

Now in 2024, it is Subianto who looks set to become President at his fourth time of trying. He has lined up Widodo’s eldest son to be his vice presidential running mate, while Widodo himself is planning to take up the chairmanship of Subianto’s Gerindra party, shifting from Megawati. It‘s going to be a tight coalition of ‘business as usual’.

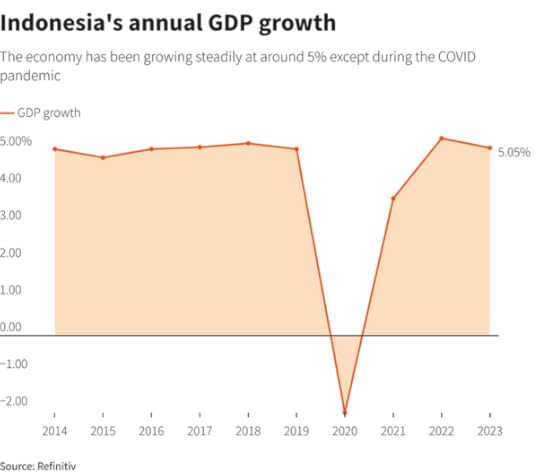

Jokowo’s eight years are regarded in the Western media and among mainstream economic circles as a great success, with average real GDP growth at around 5% a year. And he appears to remain very popular with the electorate.

But Indonesia’s apparent success is superficial. For a start, per capita income growth is much less, at under 4% a year.

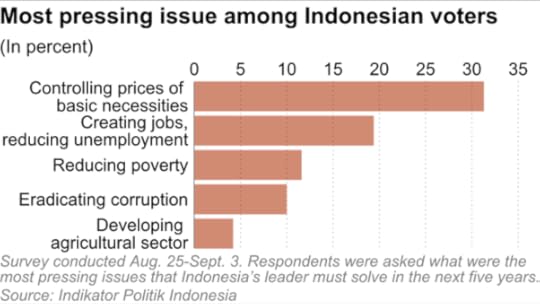

As always, what matters to Indonesians (outside the elite) are living standards and decent jobs.

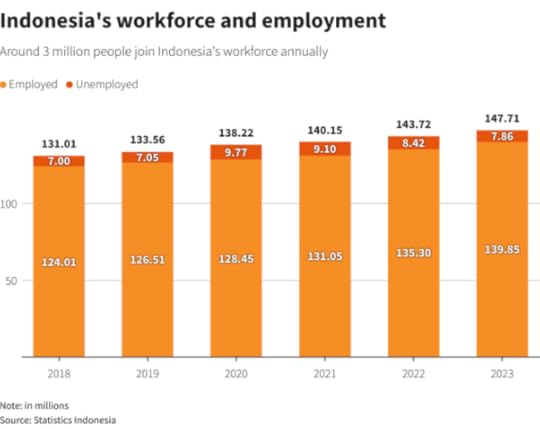

The elite claim that Indonesia can become a ‘high-income nation’ by 2045, when it celebrates 100 years of independence. And all the presidential candidates are promising upwards of 15 million new jobs in the next five years, in a country where about 3 million people enter the job market annually. But most estimates reckon that Indonesia needs 7% economic growth annually to churn out enough jobs for its young population and the growth forecast for the next two years is closer to 4% a year. Around 1,000 jobs were created for every trillion rupiah of investment in 2022, compared with 4,500 jobs in 2013.

These jobs are supposed to be generated by moving away from an economy based on mining, oil production and single crop agro exports (palm oil), which are mainly capital intensive to a more broad-based manufacturing and hi-tech economy like China or Vietnam. There is little sign of that. Instead, it is nickel mining for EV batteries that is the main investment. Investment in nickel mining and refining has created only a limited number of jobs and still relies heavily on skilled foreign labour, particularly from China.

As a result, job creation has plunged. Officially, Indonesia’s unemployment rate is 5.3%, but people are considered employed if they work just a few hours a week. Nearly 60% of workers are in the informal sector i.e. they are casual workers, with no rights, sick pay or even guaranteed wages. Young people aged 15 to 24 made up 55% of the 7.86 million officially unemployed in 2023, up from 45% in 2020.

The lack of jobs and the emphasis on capital-intensive industries owned and controlled by the Suharto oligarchs and foreign companies has widened the inequality of wealth and income – a trend in all peripheral economies. The top 1% of income earners take 18% of all personal income in Indonesia, more than the bottom 50% who take just 12% between them. It’s even more unequal with personal wealth, with the top 1% holding 41% of all personal wealth, the top 10% with 61% and the bottom 50% with just 12%.

In the past two decades, the gap between the richest and the rest in Indonesia has grown faster than in any other country in South-East Asia. It is now the sixth country of greatest wealth inequality in the world. As this election takes place, the four richest men in Indonesia have more wealth than the combined total of the poorest 100 million people. The vast majority of the land is owned by big corporations. At least 93 million (36 percent of the population) of Indonesians are below the World Bank minimum poverty level.

Inequality rose fast when Suharto switched from a development policy based on state fusion with the oligarchs to the neoclassical model of the 1980s onwards of deregulation, privatization and the abolition of subsidies on basic commodities, in order to boost the profitability of Indonesian capital that had taken a hit during the global profitability crisis of the 1970s.

But the Asian financial crisis of 1997-8 exposed this neoliberal development model and Indonesia fell back on IMF funding and its Structural Adjustment Program (SAP) that imposed austerity and more ‘flexibility’ in the labour market. Suharto was forced out, but his successors continued to accede to this ‘structural adjustment’.

Then came the commodity boom of the early 2000s. This time, expansion was based on less on minerals and oil and instead on palm oil exports. Indonesia is the world’s biggest producer of palm oil, a ubiquitous ingredient in a wide range of goods ranging from processed foods to cosmetics and biodiesel. Between 2000 and 2008, the ten largest palm oil companies controlled the industry and most of the ten richest men in Indonesia have palm oil in their portfolios.

But production of the commodity has long been associated with the wholesale clearing of tropical rainforests, burning of peatlands, destruction of endangered wildlife habitat, land conflicts with Indigenous and traditional communities, and labor rights abuses. According to one analysis, rainforests spanning an area half the size of California, or 21 million hectares (52 million acres), are at risk of being cleared.

There are still 3.1 million hectares (7.7 million acres) of plantations for which forests had been cleared for plantation. But they are not being developed because the commodity price boom is over, for now. As a result, the profitability of Indonesian capital had fallen back in the last 10 years, which is reducing investment growth and weakening economic growth.

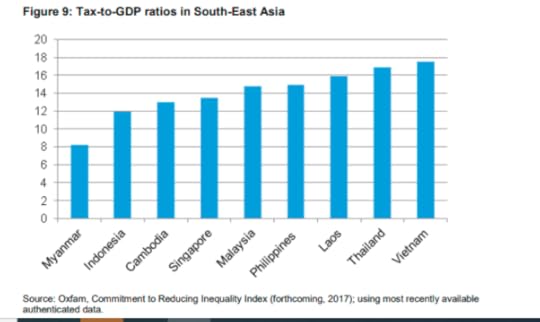

The Suharto elite and the Indonesian oligarchs remain firmly in control. The rich are not taxed properly. The OECD considers Indonesia to have the worst tax administration system of any South-East Asian country and it has the second lowest tax to-GDP ratio in South-East Asia. So the government consistently misses its already low tax revenue targets.

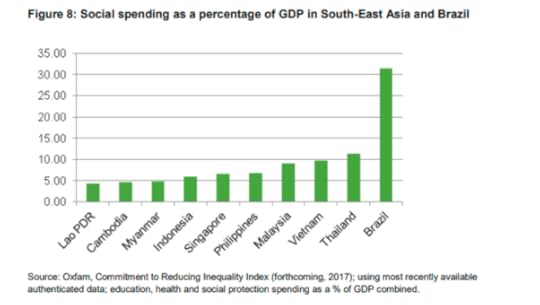

The IMF has calculated that the country has a potential tax take of 21.5 percent of GDP. If it were to reach this figure, it could increase the health budget nine times over.

Much is made of Indonesia’s supposed universal health coverage, but health spending is still equivalent to just 1 percent of GDP, which is very low by regional standards; for example, in Vietnam health spending is 1.6 percent of GDP and in Thailand 2.1 percent. And some 90–100 million Indonesians are still not covered after the health reforms, and the government has failed to reduce out-of-pocket payments (OOPs) for health services – the most regressive form of health financing. OOPs still constitute 47 percent of total health spending in Indonesia – the same level as 20 years ago. Informal workers must pay a regressive premium in order to benefit. So private hospitals proliferate and the privatization of facilities has meant that many Indonesians have been priced out of health services altogether. For example, in Kupang the privatization of Yohannes General Hospital has caused costs to skyrocket by up to 600 percent.

Likewise, the education system is underfunded; there are barriers to equal access and it does not provide Indonesians with the skills needed to enter the workforce, meaning that millions of workers are unable to access higher-skilled and higher-paid jobs. Despite an annual increase in spending on education in nominal terms, the education budget as a percentage of GDP is still only 3.4 percent – below UNESCO’s standard for education spending of 4–6 percent of GDP. The lack of government spending on education has led to a proliferation of private schools, which now account for 40 percent of all secondary school enrolments.

None of these issues are being addressed by the presidential candidates, most of whom are obsessed with Jokowo’s ambitous plan to shift the nation’s capital from the congested mess that is Jakarta to a new site in Borneo at exorbitant cost.

The Indonesian economy has yet to return to its pre-pandemic growth trajectory and it is unlikely to do so. This reflects the ‘scarring’ effects from the pandemic, including in labor markets and productivity growth. And Indonesia’s oil and gas reserves will be exhausted in the next ten years. So even the current inadequate growth rate is threatened.

Indonesia has got the classic formula for development in poor countries in the world of 21st century imperialism. Its economy is founded on basic commodity production that is highly capital intensive, severely damages the environment and does not provide many good jobs for the people, while the rich pay little tax and public services are limited. And the old Suharto elite remain in control.

February 11, 2024

Going the last mile

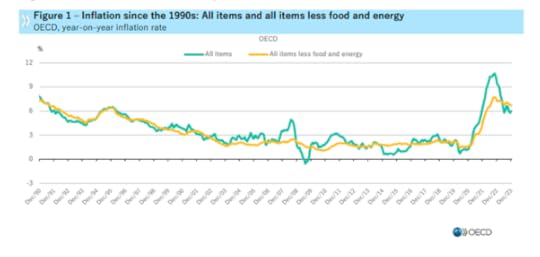

Headline inflation rates in the major economies have nearly halved since they peaked back in 2022. Average consumer price growth across the advanced capitalist economies has dropped from more than 7% in 2022 to 4.6% in 2023, according to the IMF.

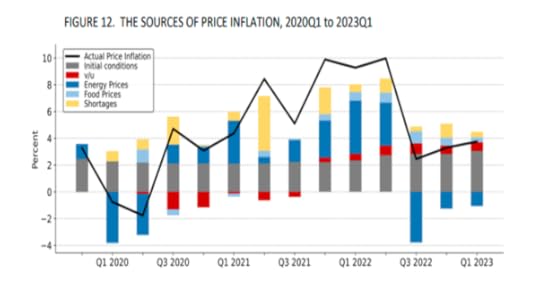

The reason for the acceleration of consumer price inflation from 2020-2022 has now been well established. It was caused by a sharp fall in the supply of basic commodities and intermediate products which drove up prices of these suddenly scarce goods. This was compounded by a breakdown in the global supply chain of goods transported and trade internationally.

The inflationary spiral from the end of the pandemic slump in 2020 to the peak in 2022 was not the result of ‘excessive demand’ caused by too much government spending or wage increases driving up costs for companies. Study after study has shown that it was supply issues not wage demands that generated the price rises (an average rise of 20% over two years). Indeed, if anything, it was excessive profit rises that contributed as companies with any ‘market power’ ie a monopolistic position took advantage of rising input costs to raise their ‘mark-ups’. This was particularly the case from the energy and food majors which control the pricing in those markets.

And yet, central bankers continue to insist that inflation rates well above their policy target of 2% a year were caused by ‘too much’ demand or ‘excessive’ wage rises. They have to say this because it is their raison d’etre. Central banks are here to manipulate interest rates and money supply, supposedly in order to ‘control’ inflation and the economy. They rest their policies on the monetarist theory that it is money supply growth and the cost of borrowing (interest rates) that control price inflation. But the experience of the post-pandemic inflationary ‘shock’ exposed (yet again) the nonsense of monetarism.

Do we need to control inflation? For workers, the answer is clearly, yes; because no inflation and even deflation means that their weekly or monthly pay checks are worth the same and any increase would mean better living standards. But that is not the same for companies. They like and want some ‘moderate’ inflation as it allows room to preserve profitability when costs of production rise or wage rises offer more demand. That’s why central banks do not have a target of zero inflation, but instead something like 2% a year.

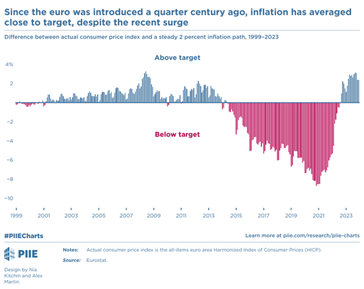

But setting a target of 2% a year is really admitting that central banks cannot control price inflation. Indeed, if we look at the history of monetary policy and its ability to achieve the (arbitrarily fixed) inflation target of 2% a year in the major advanced capitalist economies, it has been a total failure. Take the ECB’s record. In the 25 years of the existence of the euro, the ECB has only got close to achieving the 2% target once, in 2007. In every other year, inflation has been either well above 2% or well below.

Just by chance the 25-year average inflation rate is 2%, but as the chart below shows, there was a multi-year streak of undershooting the 2% from the end of 2013 (with an annual average inflation at just 0.7% to 2020, then the current overshoot (the annual average inflation since end-2020 has been 5.7%). And before 2013, the inflation rate was always well above target, despite hiking interest rates and keeping money supply growth down. In the 2010s, despite quantitative easing (monetary injections) and low and even zero interest rates, inflation did not reach 2% a year. Overall, the inflation rate had a standard deviation from the 2% annual target of 1.8 times.

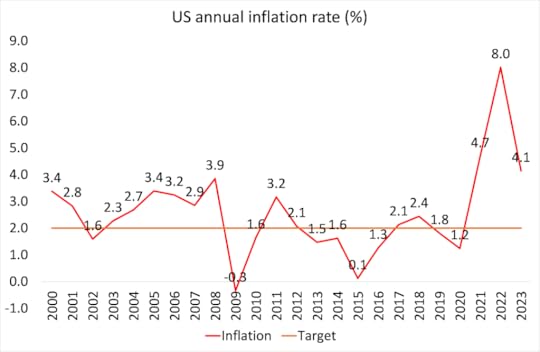

It is the same story with the US Fed. The Fed was close to its target in only two years out of the last 24, and with a standard deviation of 1.2 times. The Fed failed to keep inflation down to 2% in the 2000s and failed to get inflation up to 2% in the 2010s. Neither tight monetary policy worked in the 2000s, nor did ‘loose’ monetary policy work in the 2010s.

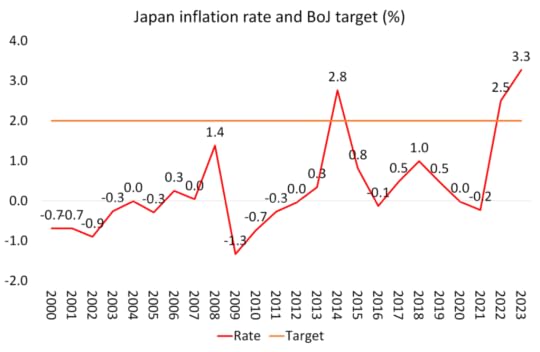

And when it comes to the Bank of Japan, it totally failed to get inflation up to 2% a year until the recent inflationary shock, despite zero interest rates and massive quantitative easing (bond purchases).

What the BoJ record confirms is that it is activity in the ‘real’ economy and the decisions of banks and companies regarding their profits (including whether to ‘hoard’ money) that decides inflation, not central bank monetary policy.

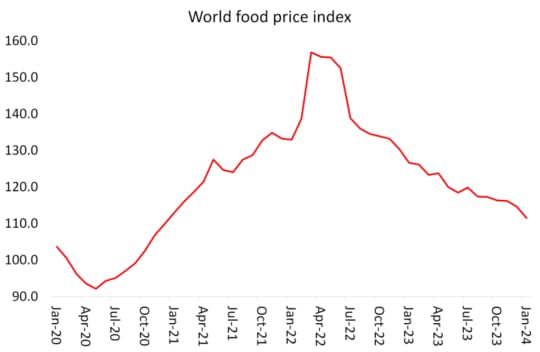

Despite the futility of their policies, central banks have ploughed on with trying to control inflation in the last two years by raising interest rates and tightening money supply. Now they are claiming their policies are why inflation rates have dropped in the last year and are still falling (for now). And yet it is clear that it is the sharp fallback in energy and food prices and prices for various intermediate products that has driven average inflation down.

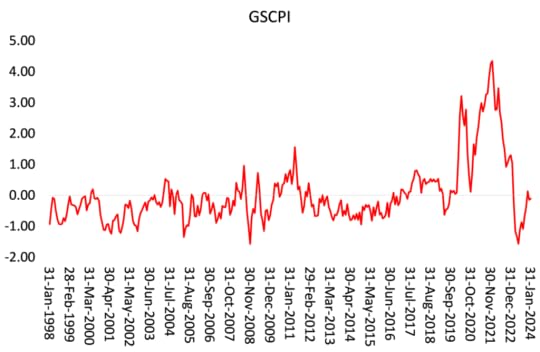

At the same time, global supply chain pressures have been reduced.

New York Fed global supply chain pressure index (GSCPI).

Central bank monetary policy has had little to do with any of this.

Isabel Schnabel is the most hawkish member of the ECB’s six-person executive board. The German economist has become one of the most influential voices on eurozone monetary policy. She continues to argue that monetary policy has been effective in controlling inflation. “Monetary policy was and remains essential to bring inflation down. If you look around, you see signs of monetary policy transmission everywhere. Just look at the tightening of financing conditions and the sharp deceleration of bank lending. Look at the decline of housing investments or at weak construction activity. And importantly, look at the broadly anchored inflation expectations in the wake of the largest inflation shock we have experienced in decades.”

Even Schnabel has to admit that, “It’s true, of course, that part of the decline in inflation reflects the reversal of supply-side shocks.” (only ‘part’?). But she continues, “monetary policy has been instrumental in slowing the pass-through of higher costs to consumer prices and in containing second-round effects.” By ‘second round effects’, she means inflation expectations.

But most of these signs are of tightening monetary policies with no causal connection to inflation. The claim that inflation was curbed by central banks ‘anchoring inflation expectations’ is really a psychological theory of inflation. Inflation expectations by consumers and companies only vary because of what is actually happening to prices. Inflation expectations have fallen because price inflation has slowed.

According to Schnabel, now the war against inflation was “at a critical phase where the calibration and transmission of monetary policy become especially important because it is all about containing the second-round effects.” This was what she has called “the last mile” in the battle to get inflation down to 2% a year.

And what is the difficulty here? Yet again, it is not supply issues or even profit mark-ups, but “the strong growth in nominal wages as employees are trying to catch up on their lost income.”. For Schnabel, it’s wage demands that are stopping inflation from falling further.

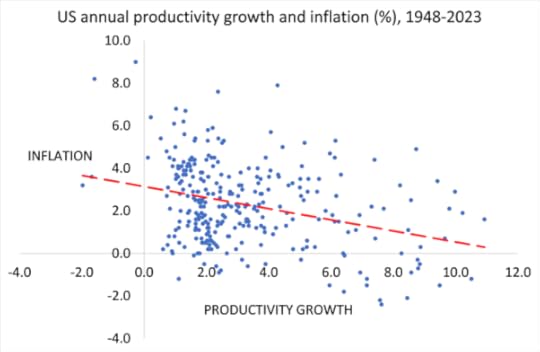

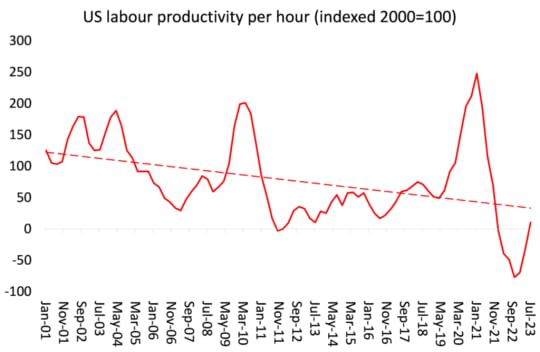

But Schnabel has to admit that if productivity growth (output per worker) were rising too, then wage costs per unit of output would not rise and profits would be secure. Unfortunately, for corporate profits, “we’ve seen a worrying decline in productivity” so “the combination of the strong rise in nominal wages and the drop in productivity has led to a historically high growth in unit labour costs.”

And indeed, there is a strong inverse correlation (0.45) between productivity growth and inflation rates over the last two decades.

Without sufficient productivity growth (more exploitation of labour), this could drive down profitability unless wage demands are curbed. “How are firms going to react? Will they be able to pass through higher unit labour costs to consumer prices?”, worries Schnabel. This is where central bank monetary policy comes in, namely to curb spending and investment by raising the cost of borrowing, she argues.

Schnabel is worried that the inflation beast has not been tamed yet and so high interest rates must be sustained. She refers to an IMF study that claims to show that when interest rates are kept high until the pips of the economic orange squeak, this not only stops inflation coming back, but also eventually gets the economy going quicker afterwards. This is the Volcker policy of the late 1970s in the US. Volcker was the Fed chief then and to ‘cure’ the economy from inflation he maintained high interest rates until the US economy dropped into a slump. Inflation then subsided but along with the economy and jobs. But this ‘cleansed’ the economy supposedly for faster growth later in the 1980s.

But the cleansing solution comes at a price (sic). The IMF report’s key finding is that the successful resolution of inflation shocks was associated with more substantial monetary policy tightening. “But those that resolved inflation with high interest rates experienced a larger decline in GDP growth than those that did not.” (IMF).

The problem with Schnabel’s monetarist theory is that it does not hold with the reality of capitalist production. Within this theory is the neoclassical concept of an ‘equilibrium rate of interest’ called R*, which is the interest rate level that supposedly keeps inflation to the set target, but also avoids unemployment and a slump. Schnabel: “The problem is it cannot be estimated with any confidence, which means that it is extremely hard to operationalize …. What we really care about is the short-run R-star, because it is relevant to determine whether our interest rates are restrictive or accommodative. The problem is we don’t know where it is precisely.” (!)

Indeed, as Minneapolis Fed President Neel Kashkari recently explained, “The concept of a neutral stance of monetary policy is critical to assessing where policy is now and what pressure it is having on the economy. While we cannot directly observe neutral, economists have models to estimate it, which are imperfect even under normal economic circumstances. Our various workhorse models for the economy have struggled to explain and forecast the pandemic and post-pandemic periods given the extraordinary changes and disruptions the economy has experienced. So I also look to measures of economic activity for signals to try to evaluate the stance of policy. In other words, the monetarist theory cannot be applied to reality and the reality is that economic activity drives inflation and money circulation, not vice versa.

Schnabel recognizes the past failure of monetarist policies. “One is the period after the launch of the ECB’s asset purchase programme in 2015. That was a time when a lot of central bank reserves — base money — were created. But we did not succeed in lifting the economy out of the low-inflation environment. Why was that?” The reason was that “the balance sheets of banks, firms, households and governments were relatively weak. You remember, after the global financial crisis and the euro area sovereign debt crisis, there was little willingness to grant loans and to invest. Inflation did not come back as much as the ECB would have hoped.” Exactly.

It was the state of the real economy, in particular profitability of capital and the low demand for credit to invest, not the price of money, not the mythical R*, that drove the economy. The ECB was ‘pushing on a string’, to use Keynes’ phrase, and getting nowhere in reaching its arbitrary 2% inflation target. Schnabel again: “the ECB’s asset purchases before the pandemic were not as successful in bringing inflation back to our target as we would have hoped, because their effectiveness depends on the economic environment.”

Indeed. The truth is that central banks have little or no influence over the investment decision of companies – it’s the profitability of investment that matters, and from that, flows how much inflation emerges in an economy. Given that profitability of capital currently remains low, investment growth is weak and productivity is not recovering much, this suggests that Schnabel’s ‘last mile’ is more like a horizon that she will never reach.

February 7, 2024

Pakistan’s misery continues

Pakistan has a general election today. It will decide on the next government of the world’s fifth-most populous nation and the governments of its four provinces — Punjab, Singh, Balochistan and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. Around 128 million people can vote to pick 266 representatives to form the 16th parliament in a first-past-the-post system. They will also vote to elect the legislatures of the country’s four provinces.

In a country of 241 million people, two-thirds are below the age of 30. A citizen becomes eligible to vote at the age of 18. But only a little more than half of Pakistan’s electorate voted last time in the 2018 elections. The previous winner of the 2018 election was former star cricketer turned politician Imran Khan. He was ousted from office in a no-confidence vote in parliament in April 2022. Since then, he has been shot and injured and then locked up for up to 20 years on various charges of corruption and sedition. Thousands of his party members have been arrested and he has been banned from standing. But polls suggest that he would win this election, if the election were ‘fair’.

No Pakistan Prime Minister has ever completed a full term. That’s because ever since the formation of the country, the military has been in control. It is the most powerful institution in the country with a huge 12.5% of the government budget going towards military spending. The military decide the needs of Pakistan’s elite.

Khan fell out with the military when the latter decided to switch sides from leaning on the support of China against its main perceived enemy, India and from relying on Chinese credit to survive. The military switched back to the side of the Americans with bribes of money from Saudi Arabia and the UAE and because of the desperate need to get funds from the IMF, which Khan was reluctant to take because of austere conditions attached. “From a Washington perspective, anyone would be better than Khan,” said Michael Kugelman, the director of the South Asia Institute at the Wilson Center in Washington. In contrast, the likely winner of the election and the candidate backed by the military is perceived as “business-friendly and pro-America.”

The military don’t want to run the country directly, but they are making sure that they get a government that follows their interests. And this is the party of Nawaz Sharif, three-time former Prime Minister, who was previously ousted for corruption in 2017 and sentenced to 10 years imprisonment. In 2022 he returned to Pakistan with his corruption conviction swiftly quashed and his lifetime ban from politics overturned. His party and the military then ensured the removal of Khan. Sharif’s government is now trying to meet the demands of the IMF and the military to run the economy around.

And Pakistan’s economy is in deep trouble and in recession. Major floods caused heavy damage to crops and livestock, and with 44% workers relying on agriculture, this has driven millions into deep poverty. Investment has collapsed. It has been estimated that Pakistan needs more than $16bn to recover from the disaster.

Pakistan’s per capita income and GDP growth are the lowest in the region, bar war-torn Afghanistan. Its unemployment and inflation rates are one of the highest in the region. The Human Development Index, which measures a country’s achievements through three basic dimensions – health, knowledge, and standards of living – placed Pakistan in the 161st position out of 185 countries in 2022. In other words, Pakistan is among the 25 countries with the lowest human development in the world.

Pakistan remains in the grip of a small group of landowners and business families. It is one of the most unequal countries in the world. Just 22 families control 66% of Pakistan’s industrial assets and the richest 20% consume seven times more than the poorest 20%. The top 1% of income earners have the same share of total personal income as the bottom 50% (15.7%) and the top 1% of wealth holders own 26% of all personal wealth while the bottom 50% of Pakistanis have just 4% (World Inequality Lab). Both the names Khan and Sharif mean ‘ruler’ or ‘noble’. Around 45% of all holders of office across Pakistan came from family ‘dynasties’, with their political direction decided by whom the military establishment selects. Most income held by the rich goes into real estate and financial assets (much of it spirited abroad).

Investment by the capitalist sector is just 11% of GDP. This compares with China at 45% or even most less developed countries at over 20%. Exports make up just 7.6% of the country’s GDP. That’s nearly 17 percentage points less than the average for middle-income countries overall. What the country does export tends to be low-value-added products, like textiles, cotton and rice. As a result, Pakistan relies on the flow of remittances from Pakistanis working abroad (and these have been falling) and outside funding.

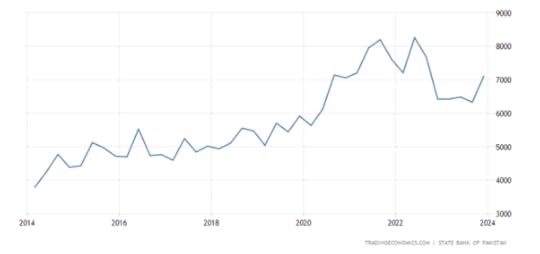

Remittances $bn

Pakistan depends heavily on imported oil. A constant decline in the value of the country’s currency has resulted in much higher energy costs. Pakistan’s real effective exchange rate, a broad measurement of the strength of a currency, declined from 88.0 in 2022 to 72.0 in 2023, and the Pakistan rupee is down 40% against the US dollar in the last year. The falling currency and rising living costs drove the inflation rate to near 40% (now around 30% a year). Interest rates are at a record high, crushing investment.

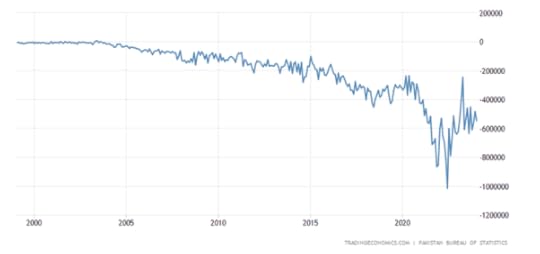

This decline in the value of Pakistan’s currency is because of the country’s export failure. Pakistan is essentially running on foreign loans. External debt accounted for 36% of the country’s nominal GDP in 2023, a noticeable increase from the previous year. The government debt-to-GDP ratio reached 89%. By June 2026, Pakistan will have to repay around $80 billion in foreign debt.

Balance of trade PKR m

Of Pakistan’s $126bn external debt and liabilities, 30% is owed to China. Under the Belt and Road Initiative, China has invested more than $60bn in the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), which began in 2015. This connects the Pakistani port of Gwadar in the Arabian sea to China’s north-western region of Xinjiang through a network of highways, railways and pipelines. So far, of the numerous projects agreed upon under CPEC, only a few have been completed. Chinese frustration over endless delays in project completion, halting of projects, and security threats to its nationals working in Pakistan has resulted in hesitation to invest in new projects.

The military wants to switch away from Chinese funding to that of the West and the Arab states. In July 2023, the IMF approved an emergency $3bn Stand-By Arrangement (SBA) to avert a complete collapse and debt default. But the IMF wants Pakistan to go further and completely ‘float’ (sink!) its exchange rate, ostensibly to boost exports. And for any further loans that Pakistan wants, the IMF is insisting on the government increasing electricity tariffs and cutting government spending.

The military is now looking to sell off state assets to attract foreign investment. It has established a military dominated body to manage major economic projects in the country — the Special Investment Facilitation Council (SIFC). Comprising the prime minister and army chief, the SIFC has greenlit 28 investment projects to pitch to the Gulf nations. The SIFC is also trying to sell off the Reko Diq mines, one of the world’s largest reserves of gold and copper, to Saudi Arabia. Other plans include outsourcing management of airports to the UAE, privatising the national airline on an accelerated timeline and expediting a free trade agreement with the UAE, referred to as the Comprehensive Economic Partnership Act. With this strategy, the government hopes to get the US to back a further IMF loan.

Meanwhile some 700,000 workers have lost their jobs following the closure of about 1,600, or about one-third, of the country’s textile factories, which contribute 60% of the country’s total export earnings. One textile working family explained how the escalating cost of living was affecting them and their five children. The couple work extra-long hours to feed their three daughters and two sons, none of whom go to school. “We used to somehow manage our daily expenses within 500 Pakistani rupees (£1.40; $1.75) a day. Now things have changed. To cook just one meal, we need 1,500 rupees,” Mr Maseeh said. His wife added: “Our earnings are not enough even to provide a good meal. How can we afford to send our children to school?”

Pakistan’s adults vote today but with no prospect of obtaining an end to the disaster that it is Pakistan capitalism and landlordism and its military rule.

January 30, 2024

Why did the US avoid a recession in 2023?

I have been considering why in 2023 the US economy grew by 2.5% in gross domestic product (GDP) in real terms (ie after the official inflation rate is deducted). This growth rate was not forecast by the consensus at the beginning of 2023 – indeed the majority forecast that a slump i.e. a contraction in national output, was more likely – including me.

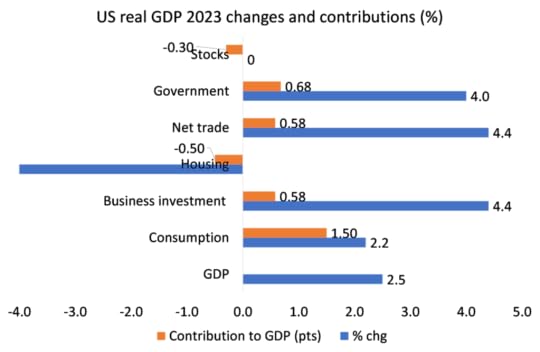

First, let’s remind ourselves that real GDP may have risen by 2.5%, but real domestic income (GDI) rose only 1.5%. GDP has been growing faster than GDI because there is more consumer borrowing (and running down of savings) and because there is more production without sales. So the GDI measure may well be more accurate about what is happening to the US economy than GDP. But we don’t have the final figure for GDI in 2023 yet, so let’s accept the GDP figure for now.

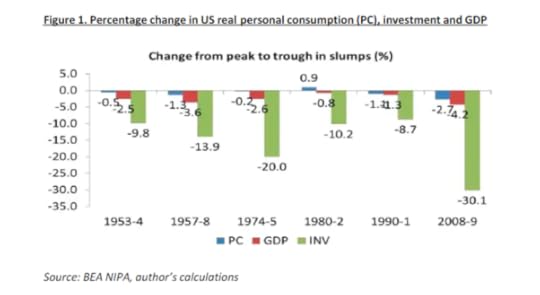

What happened to deliver this significant, if modest rise in real GDP? The mainstream economists and media go on about how consumption remained strong i.e. American households continued to spend more and it was this that delivered the faster growth than expected. But there are two things wrong with this explanation. First, in 2023 consumption growth was actually slower than in 2022, slowing from a 2.5% rise in 2022 to a 2.2% rise in 2023. Yet real GDP growth accelerated from 1.9% in 2022 to 2.5% in 2023. So this cannot be the main reason for the rise last year.

Second, theoretically, consumption is never the swing factor in economic growth, contrary to the views of ‘simplistic’ Keynesians. In all US economic recessions since 1945, it has been a contraction in investment that has led to a slump and vice versa. Investment leads consumption and is the swing factor.

Yes, consumption growth contributed 60% of the 2.5% real GDP rise in 2023, but that contribution was down from over 90% in 2022 and 2021. Also, the increase in household consumption was mainly confined to spending on healthcare and on leisure services. Most Americans were forced to increase spending on private health insurance and utilities. But spending on other basic items was up only a little. Indeed, inventories i.e. stocks of goods that could not be sold, did not fall in 2023, after a large rise in 2022. So companies still had a hangover of stock in 2023 from 2022.

It was business investment that saw the biggest swing to boost real GDP growth. The housing market continued to fall as mortgage rates rose, but investment in new structures and transport (factories, offices, roads etc) rose nearly 13% in 2023, having fallen in 2022. This contributed 0.5% pts (or 20%) of the 2.5% growth. It was in structures that increased business investment concentrated, because investment in equipment (computers,etc) did not rise at all.

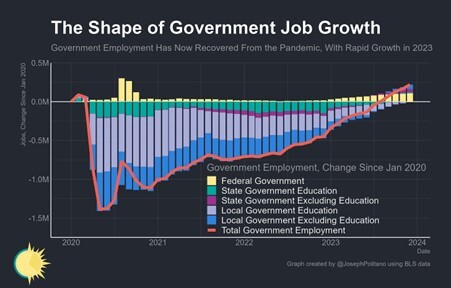

What was going on here? Government spending on consumption and investment rose considerably. Under GDP definitions, such spending is regarded as an addition to national output. Having declined 0.9% in 2022, spending rose 4% in in 2023 or a 4.9% pt swing from 2022. Spending both on defence and civil projects rose significantly.

It was the huge tax incentives and subsidies offered by the Federal government and distributed through the states to companies willing to build new plant and factories, particularly in strategic sectors like tech and semiconductors as part of the US administration’s ‘chip war’ against China. It also seems that the biggest spending boost came from the state governments, using unused COVID funds and unexpectedly higher tax revenues. This extra money went mostly on employing government staff in education.

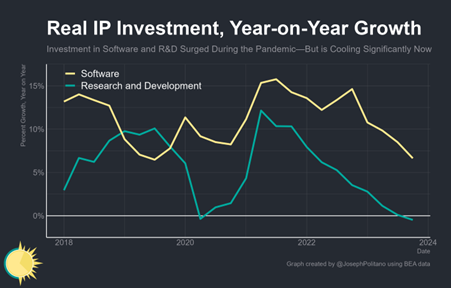

But there were no new tax incentives etc for business investment in equipment etc, so growth in that sector was stagnant. There was a substantial deceleration in the pace of real investments in ‘intellectual property’ as the tech industry slowed down and higher interest rates weighed on research and development decisions. Over the last year, software investments have grown at the slowest pace since late 2015, while real R&D output outside the software sector has shrunk for the first time since the early pandemic.

Another surprise booster to US economic growth was net trade. Net exports were up 4.4% in 2023 after contracting in the four previous years. Exports were boosted by sales of liquid natural gas and oil to Europe given the loss of Russian energy imports there and by financial services exports, but the main cause of the jump in net trade was a decline in imports as import prices in energy and food fell sharply after two years of sharp rises.

To sum up, the US economy grew modestly instead of going into recession in 2023 because of: stronger business investment funded by government spending; a positive trade balance as energy imports fell; and because of the continuance of a sizeable stock of unsold goods. If all these (mainly one-off) contributions to growth had not happened in 2023, US economic growth (in GDP) would have been just 1.5%, not 2.5%. i.e. lower growth than in 2022.

Also, average real incomes rose in 2023 as wage growth outstripped price inflation for the first time since the end of the pandemic. As has been argued in many previous posts, the acceleration in inflation was mainly due to ‘supply-side’ factors: supply chain blockages and stagnant manufacturing output and trade. It’s not been due to ‘excessive demand’ and so the interest rate hikes by the Fed have played little role in halving the inflation rate in 2023. It was the improvement in supply chains that did it.

But the Fed’s rate hikes did not induce a slump in 2023, so does that mean a ‘soft landing’ for the US economy after the ‘sugar rush’ recovery in 2021 has been achieved, or even better, no landing at all but just a strong economic boom ahead?

There are many things to suggest that the factors that delivered faster growth in 2023 will not be around this year. First, investment in manufacturing structures will cool significantly. And the sharply increased spending by state governments is probably a one-off. Also, the decline in software and R&D investment in 2023 is not a good sign for 2024.

Second, net trade is unlikely to contribute to growth in 2024 as import costs will rise again, given a weaker dollar in foreign exchange markets and hits to the global supply chain from disruptions in the Middle East.

Third, the cost of government spending is reaching record levels in debt servicing. Federal government interest payments on bonds have surpassed $1trn and are still rising. Unless the Fed gets interest rates down fast, that is going to eat into the funding of government services (outside defence, of course) as the Biden government aims to reduce spending from hereon.

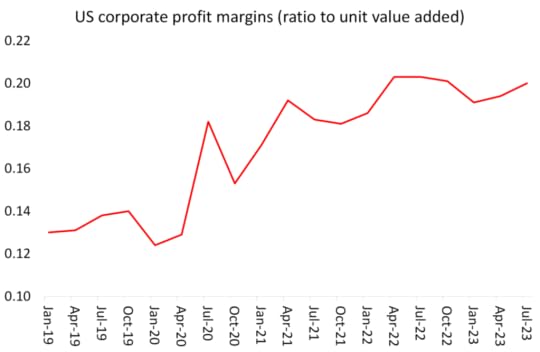

In 2024, much will depend on whether inflation continues to fall and whether the existing high level of nominal interest rates does not turn into a sharp rise in the real rate of interest (that’s after taking inflation into account). If it does, then corporate profits will begin to fall. Corporate profit margins (profit per unit of value added) have flattened out since 2022 and even fell a little in 2023. But they are still very high (if mainly due to high margins for tech and energy companies).

But wage rises are not being compensated for by increased productivity of labour (thus raising the rate of exploitation) and so margins will fall this year.

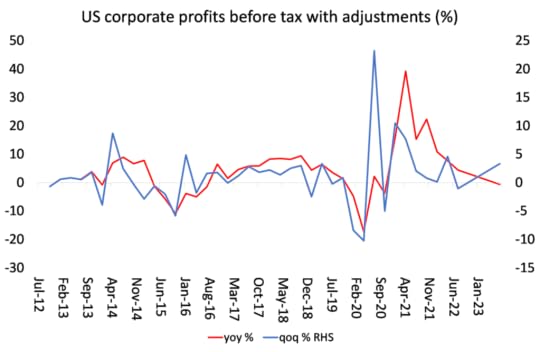

Corporate profits (that’s margins multiplied by sales) are already slipping towards negative territory.

And it is profits that lead investment that then leads to employment, incomes and consumption – not the other way round, as the Keynesians argue. So slowing or falling profits will reduce the incentive to invest more.

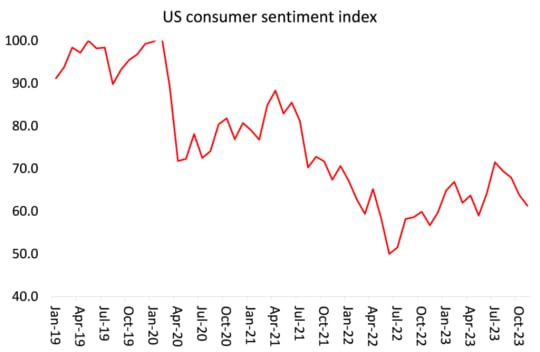

At the same time, the labour market is ‘cooling’. Unemployment is creeping up and the jobs available are mainly low-paid, part-time or temporary. American households are spending more by reducing savings and/or borrowing more (at very high interest rates). No wonder the average American consumer thinks the economy is in a recession, not in a boom. Consumer sentiment improved in 2023, but it’s still way below pre-pandemic levels.

If interest rates stay high and the Fed appears to have no intention of starting to cut rates before the summer, the impact will feed through this year into more corporate bankruptcies (already rising) and perhaps another banking crisis like last March.

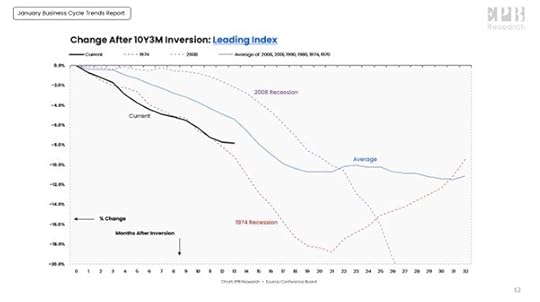

And let’s remind ourselves of what was considered to be a very reliable indicator of a recession: the inverted bond yield curve i.e. where short-term interest rates are higher than long-term bond yields. The inversion supposedly shows that investors want to hold ‘safe’ government bonds more than cash or investments, suggesting that they fear a slump ahead. History shows that if the curve remains inverted for long enough, then a recession arrives. The average length of inversion before a recession comes is about 18 months (as with the 1974 and 2008 slumps). The current inversion is about 13 months old.

And looking ahead, the US Conference Board has a leading economic index (LEI) made up of components in the US economy to measure future expansion or recession. This LEI continues to signal recession.

So far, these indicators have not proved right, but we shall see in 2024.

January 26, 2024

China versus the US

The US economy grew 2.5% in 2023 over 2022, according to the first estimate of real GDP for Q4 released this week. This was greeted with rapture by Western mainstream economists – the US is motoring and the ‘recession forecasters’ have been proved badly wrong. Earlier in the week, it was announced that the Chinese economy grew 5.2% in 2023. In contrast to the US, this was condemned by Western mainstream economists as a total failure (with China using probably faked data anyway) and demonstrated that China is in deep trouble. So China grows at double the rate of the US, the best performing G7 economy by a long way, but it is China that is ‘failing’, while the US is ‘booming’.

Western economists continue to argue that the Chinese economy is heading down the drain. I have rejected this familiar refrain on numerous occasions on my blog. This is not because I have unquestioning support for the so-called ‘Communist’ party regime – on the contrary. It is because the Western critique is not factually correct – and also because the aim of that critique is to trash the predominant role of China’s state sector and its ability to sustain investment and production. The critique aims to distract attention from the reality that the Western capitalist economies (apart from the US it seems) are floundering in stagnation and near slump.

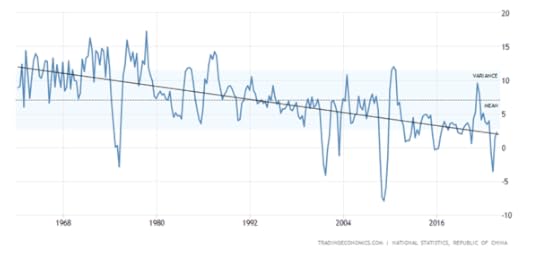

Take this as an example of the Western view of China: “the Chinese economic model has well and truly run out of juice and that a painful restructuring is required.” Actually, if we look at the growth rate of the US from 2020-23 and compare it with the average growth rate between 2010-19, even the US economy is underperforming. In the 2010s, the US average annual real GDP growth rate was 2.25%; in the 2020s so far, the average is 1.9% a year.

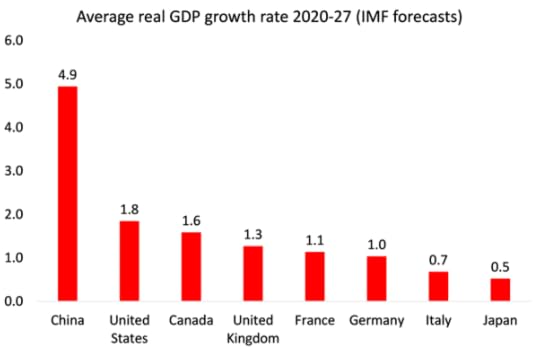

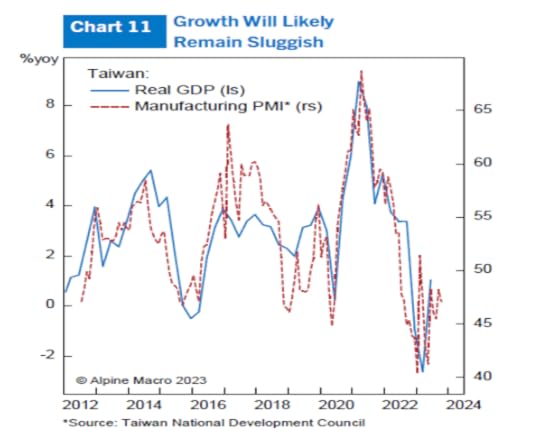

If we compare China’s 5.2% growth rate with the rest of the major economies, the gap is even greater than with the US. Japan grew 1.5% in 2023; France 0.6%, Canada 0.4%, the UK 0.3%, Italy 0.1%, and Germany fell -0.4%. Even compared to most of the large so-called emerging economies, China’s growth rate was much higher. Brazil’s growth rate is currently 2% yoy, Mexico 3.3%, Indonesia 4.9%, Taiwan 2.3% and Korea at 1.4%. Only India at 7.6% and the war economy of Russia at 5.5% is higher (of the large economies).

There is a continual attempt to trash the official statistics offered by the Chinese authorities, especially the growth figure. I have discussed the validity of this critique in posts before, but the current argument is that the Chinese GDP figures are faked and if you look at other ways of measuring economic activity like electricity or steel generation or traffic on the roads and ports, then we get a much lower growth figure. But even if you reduced the growth rate by say one-third, it would still mean a rate that is twice that of most advanced capitalist economies and above most others. And we are talking about an economic giant, not some tiny island like Hong Kong or Taiwan.

And India’s figures are to be disputed just as much as China’s are by Western economists. Back in 2015, India’s statistical office suddenly announced revised figures for GDP. That boosted GDP growth by over 2% pts a year overnight. Nominal growth in national output was being ‘deflated’ into real terms by a price deflator based on wholesale production prices and not on consumer prices in the shops, so that the real GDP figure rose by some way. Also the GDP figures were not ‘seasonally adjusted’ to take into account any changes in the number of days in a month or quarter or weather etc. Seasonal adjustment would have shown India’s real GDP growth well below the official figure. A better gauge of growth may be found in the industrial production data. And that is just 2.4% yoy in India, while China’s rate is 6.8%.

Indeed, the IMF reckons that China will grow by 4.6% this year, while the G7 capitalist economies will be lucky to manage 1.5%, with probably several going into outright recession. And if the IMF forecasts through to 2027 are accurate, the gap in growth will widen.

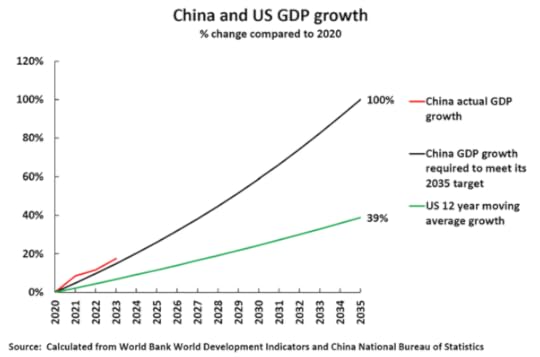

As John Ross has pointed out, if the Chinese economy continues to grow 4-5% a year over the next ten years, then it will double its GDP – and with a falling population, raise its GDP per person even more. “To achieve China’s target of doubling GDP between 2020 and 2035 it had to achieve a 4.7% annual average growth rate. So far since 2020 China has achieved an annual average 5.5% growth rate – with a per capita GDP annual average increase of 5.6%. To be on target for achieving its 2035 goal, China’s total GDP increase from 2020 had to be 15.5% and in fact it achieved 17.7%. The U.S. Congressional Budget Office, which makes the official economic projections for the U.S. government policy making, projects that the U.S. economy will grow at 1.8% a year until 2033 and 1.4% year from then onwards. Even if the higher rate of annual growth was achieved the U.S. economy would only grow by 39% between 2020 and 2035 whereas China would grow by 100%. That is China’s growth would be more than two and half times as fast as the US.”

But Western economists reckon that this target will not be met. First, they argue that China’s working population is falling fast and so there will not be enough cheap labour to boost output. But more output does not just depend on a rising labour force but even more on the increased productivity of that labour force. And as I have shown in previous posts, there is good reason to assume that China’s productivity of labour will rise enough to compensate for any decline in the number of workers.

Second, the Western consensus is that China is mired in huge debt, particularly in local governments and real estate developers. This will eventually lead to bankruptcies and a debt meltdown or, at best, force the central government to squeeze the savings of Chinese households to pay for these losses and thus destroy growth. A debt meltdown seems to be forecast every year by these economists, but there has been no systemic collapse in banking or in the non-financial sector.

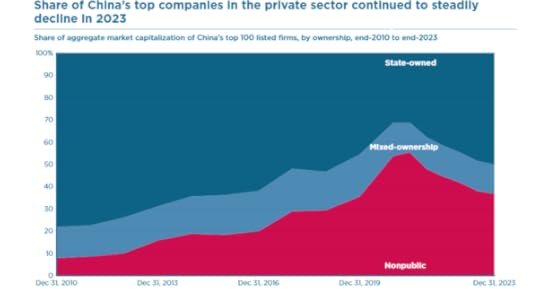

Instead, the state-owned sector has increased investment and the government has expanded infrastructure to compensate for any downturn in the over-indebted property market. Indeed, it is China’s capitalist sector (based mostly in unproductive areas) that is in trouble, while China’s massive state sector takes the lead in economic recovery.

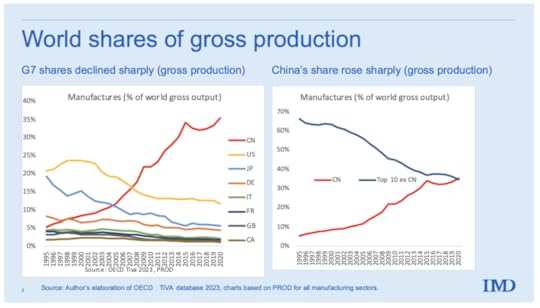

The reality is that China is continuing to lead the world’s productive sectors, like manufacturing. China is now the world’s sole manufacturing superpower. Its production exceeds that of the nine next largest manufacturers combined. It took the US the better part of a century to rise to the top; China took about 15 or 20 years.

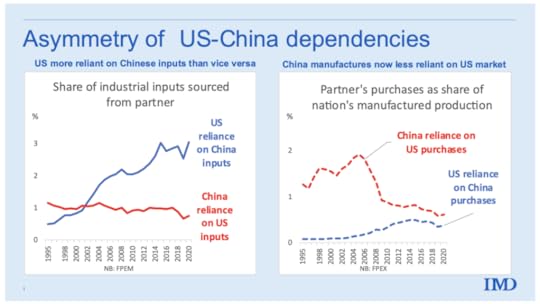

In 1995 China had just 3% of world manufacturing exports, By 2020, its share had risen to 20%. Far from China being forced into a corner by the US ‘decoupling’ its investment into and demand for Chinese goods, the US is more dependent on Chinese exports than vice versa.

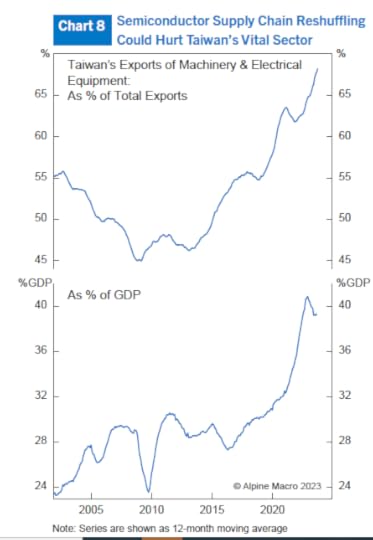

And China is closing the gap with the US in hi-tech products including semi-conductors and chips.

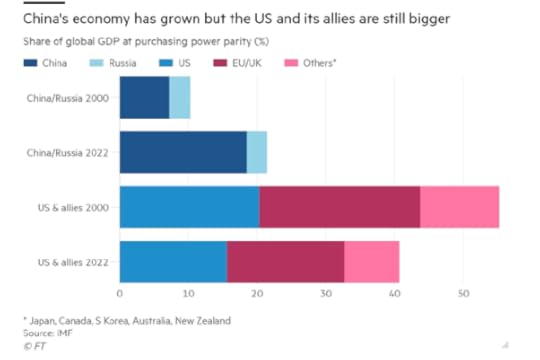

China has still some way to go to surpass the combined economic power of the imperialist economies, but it is closing the gap. This is what worries the US and its allies.

But you see, say the Western economists, China’s emphasis on manufacturing production and investment in infrastructure and technology over increasing household consumption is the wrong model for development. According to neoclassical (and Keynesian) theory, it’s consumption that leads growth, not investment. So China needs to break up its too large state sector, cut taxes for private enterprises and deregulate to allow the private sector to expand sales of consumer goods.

But has the large consumption share in the Western economies led to faster real GDP and productivity growth, or instead to real estate busts and banking crises? And is it not really the case that more productive investment boosts economic growth and employment, and thus wages and spending, not vice versa? That is the experience in China over the last 30 years, with high growth and investment delivering rising wages and consumer spending.

We shall see who is right about China during this year.

January 23, 2024

Marx’s law of profitability – yet more evidence

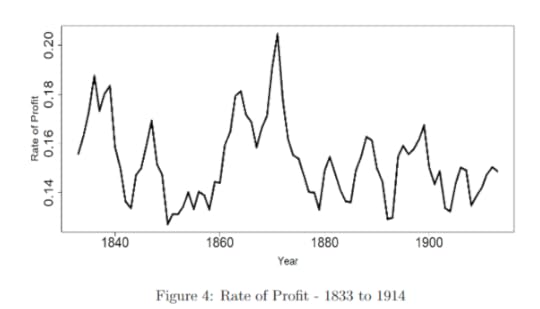

Marx’s law of the tendency of the rate of profit to fall (LTRPF) argues that, over time, the profitability of capital employed will fall. Marx reckoned this was “the most important law of political economy” because it posed an irreconcilable contradiction in the capitalist mode of production between the production of things and services that human society needs and profit for capital – and it would generate regular and recurring crises in investment and production.

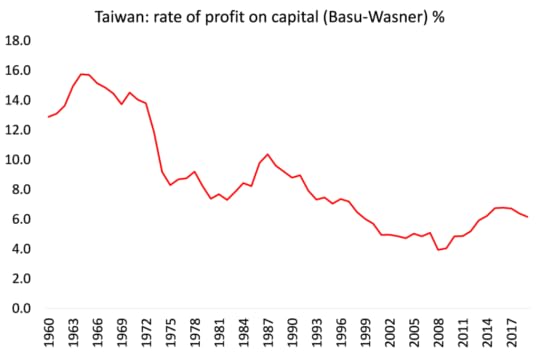

Marx’s law has been attacked theoretically as erroneous, illogical and indeterminate and it has been rejected as empirically disproven. However, various Marxist economists have provided a robust defence of the law’s logic. (Carchedi and Roberts, Kliman, Murray Smith.) And the body of empirical evidence supporting a long-term falling rate of profit on capital accumulated has mounted over the years.

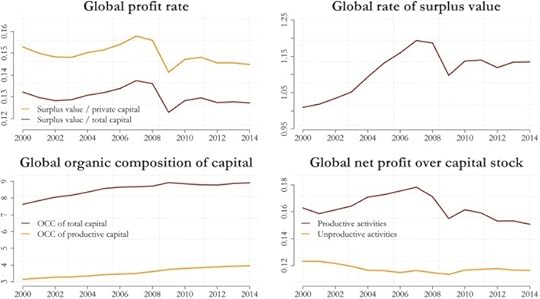

Now Tomas Rotta from Goldsmith University of London and Rishabh Kumar from the University of Massachusetts have made another important contribution to the empirical evidence supporting Marx’s law of the tendency of the rate of profit to fall. In their paper, Was Marx right? Development and exploitation in 43 countries, 2000–2014, R&K find that Marx’s law is right: capital intensity rises faster than the rate of exploitation and so the global profit rate declines.

They generate a new panel dataset of the key Marxist variables from 2000 to 2014 using the World Input Output Database (WIOD) covering 56 industries across 43 countries in the 2000-2014 period. “To the best of our knowledge, ours is the first ever attempt at producing a comprehensive global dataset of Marxist variables.”

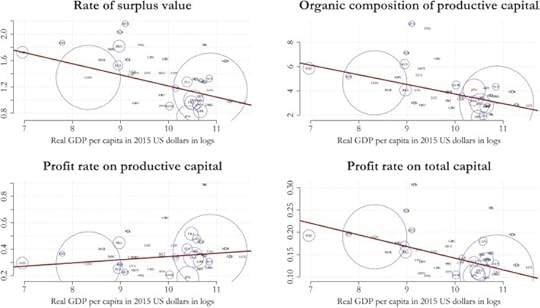

R&K find that the average profit rate declined at the world level from 2000 to 2014. They add that the rate of profit on total capital declined as per-capita GDP for a country rose owing to the greater share of unproductive capital in rich countries. Given that unproductive activities increase with economic development, “our finding adds a second mechanism to Marx’s original prediction about the falling rate of profit.”

The big advantage of the R&K’s study is that it can produce a rate of profit based on the productive sectors of economies. In Marxist theory, it is only these sectors that generate new value from capital investment and not just redistribute value already created. So it is the rate of profit in these productive sectors that best indicates the health and direction of the capitalist economy; as the rate of profit in the non-productive (financial, retail, commercial and property) sectors ultimately depends on the rate of profit in the value-creating productive sectors.

R&K point out that previous estimates of the rate of profit at a global level could not make this distinction (Basu et al. (2022) https://thenextrecession.wordpress.com/2020/07/25/a-world-rate-of-profit-a-new-approach/ ). But using industry-level data from the Socio-Economic Accounts (SEA) of the World Input-Output Database (WIOD) and country-level data from the Extended Penn World Tables (EPWT), R&K recalculate the value added of every industry using the decomposition between productive and unproductive activity.

They find that the global rate of profit on both total and private capital reached a peak at 13.7% just prior to the 2008 financial crisis, then plummeted and continued a gradual decline to 12.7% in 2014 (graph top left). This was accompanied by a rise in the organic composition of capital (the ratio of fixed assets and raw materials to wages of labour) – graph bottom left, which rose faster than the rate of surplus value (profits over wages) – graph top right – all in accordance with Marx’s law of profitability. And this overall fall was driven by a fall in the rate of profit in productive sectors (graph bottom right).

“The increase of 12.4% in the rate of surplus value suggests that the decline in the global rate of profit was driven by a larger increase in capital intensity. The productive capital-labor ratio rose 25.8% (from 314% to 395%) while the total capital-labor ratio rose 16.8% (from 763% to 892%) over 2000–2014. The decline in the world rate of profit was therefore driven by the faster growth of the global c/v compared to the growth in s/v, as Marx expected.”

Another advantage of R&K’s dataset is that it enables the decomposition of the Marxist variables for the rate of profit within countries and between countries. They find that “in just 15 years, China rapidly increased its weight in global value added from 5.3 to 19.3%. Concurrently, the weight of the United States in global value added fell from 30.1 to 22.3%, and Japan’s weight shrunk from 16.3 to 6.7% in the same period. Although the shares are smaller, there is also a rapid downward shift for Germany from 6.6 to 6.0%.”

China also became the country with the greatest share of the global capital stock in productive activity, rapidly increasing its weight from 6.0 to 23.6%. This compared to a fall of the United States’ weight from 24.8 to 17.4%, Japan from 21.2 to 8.8%, and Germany from 6.5 to 4.6%. Not surprisingly, the United States dominated the shares of global income and capital stock in unproductive activity i.e. finance, real estate and government services. The US and the UK are increasingly ‘rentier economies’, living off the new value created in China and other major productive economies.

According to R&K, following Marx, the advanced capitalist economies should exhibit higher rates of surplus value, higher organic composition of capital and lower average profit rates. And yet, they found that the rate of surplus value is higher in poor countries. Their answer is to this is that the level of wages is much higher in the rich countries compared to wages in the poor countries – a differential that is sufficient to make the rate of surplus value higher in the latter. “Wage rates per hour are an order of magnitude higher in rich countries: while the ratio of labor productivity between India and USA is 5%, the ratio of wages is only 2%. Thus, being a worker in India implies substantially lower wages than being a worker in France or Germany.”

This is similar to the explanation that Carchedi and I made in our paper on modern imperialism, where we also found a higher organic composition of capital in the imperialist economies, but also a higher rate of surplus value in the periphery. (see graph below, top left). However, R&K reckon this outcome provides empirical support to the super-exploitation thesis of Ruy Mauro Marini and others. But I don’t think this follows.

Low wages do not have the same meaning that Marx gave to ‘super-exploitation’. He defined that as when wage levels are below the value of labour power, which would be the amount of value necessary to reproduce the labour force. As argued at length in our book, Capitalism in the 21st century pp134-140, average wage levels in poor countries do not have to be below any value of labour power to lead to higher rates of surplus value in these countries.

R&K find that richer countries have lower profit rates which they argue is due to the greater stock of fixed capital tied up in unproductive activity in the rich countries (graph bottom right). This is because the data show a higher rate of profit on productive capital in rich countries (graph bottom left).

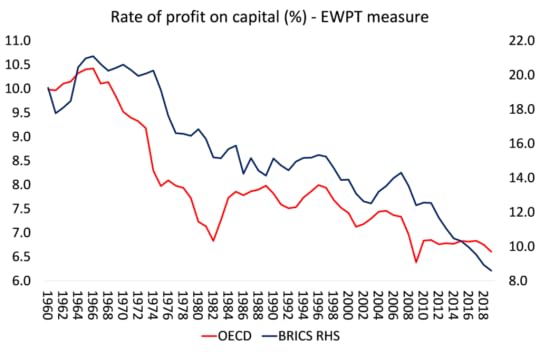

All these results are a valuable contribution to supporting Marx’s law of profitability. But R&K’s approach has limitations. As they point out, the time series using the WIOD is very short, just 15 years from 2000 to 2014. But more important, input-output tables have some theoretical disadvantages as they measure inputs and outputs (whether in money or labour terms) in the same year, like a snapshot. They do not measure production prices and profit rates dynamically. That’s where the Basu-Wasner data using the EWPT database (see above), although it cannot distinguish between productive and unproductive sectors, has an advantage in indicating changes and trends over time.

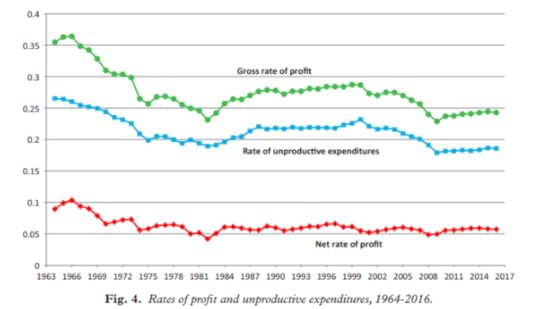

And there have been attempts to use national data to generate rates of profit for productive and unproductive sectors. Tsoulfidis and Paitaridis (T&P) did so here. Their results for the US show that, in the 1990s, there was a rise in the overall (gross) rate of profit in the neo-liberal period from the early 1980s to the end of the 20th century, but the rate of profit in the productive sectors (net profit rate) of the US economy did not rise and capitalist investment went more into unproductive sectors (finance and real estate).

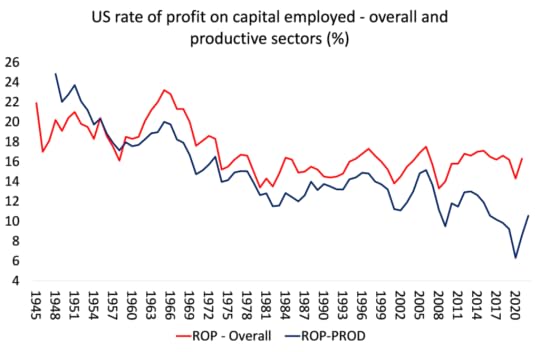

In a recent piece of (unpublished) work by me , which also breaks down the rate of profit between the productive sectors (using similar categories as R&K) and the overall US economy, I get a similar result to T&P. The gap between the ‘whole economy’ rate of profit and the rate of profit in the productive sectors widened from the early 1980s. The overall rate has been pretty static since 1997, but profitability in the productive sectors, after rising modestly in the 1990s, has fallen back sharply since about 2006. US capitalists are finding better profits in unproductive sectors. That damages productive investment.

But these results are for the US only. Only R&K have produced, as they say, the first set of Marxist variables that distinguishes the productive from the unproductive sectors for the world and thus throws more light on the health of capitalist production – an important step in the empirical work supporting Marx’s law.

January 16, 2024

Davos and the melting world economy

The annual jamboree of the rich global elite called the World Economic Forum (WEF) is under way again in the luxury ski resort of Davos, Switzerland. Thousands will attend and many of the ‘great and good’ of political and corporate leaders have arrived in their private jets with huge entourages. The speakers include China’s premier Li Qiang, the head of the EU, Ursula von de Leyen, Zelenskyy from Ukraine and many top business leaders.

The WEF aims to discuss the challenges facing humanity in 2024 and onwards. These challenges, however, are primarily seen from the point of view of global capital and any proposed policy solutions are driven by the aim to sustain the world capitalist order.

This is revealed in the WEF’s annual Global Risks Report which carries out a survey of Davos participants. The report “explores some of the most severe risks we may face over the next decade, against a backdrop of rapid technological change, economic uncertainty, a warming planet and conflict. As cooperation comes under pressure, weakened economies and societies may only require the smallest shock to edge past the tipping point of resilience.”

On the world economy, the report is worried. Entering the top ten ‘risks’ for for those surveyed in 2024 was the cost-of-living crisis and economic stagnation. The WEF report says: “Although a “softer landing” appears to be prevailing for now, the near-term outlook remains highly uncertain. There are multiple sources of continued supply-side price pressures looming over the next two years, from El Niño conditions to the potential escalation of live conflicts. And if interest rates remain relatively high for longer, small- and medium-sized enterprises and heavily indebted countries will be particularly exposed to debt distress.”

The report calls this situation ‘uncertain’, but what is certain is that the so-called ‘soft landing’ ie steady economic expansion without a slump is confined to the US economy, not elsewhere, at least among the major advanced capitalist economies.

Even the US economy’s prospects are nothing to write home about despite the optimistic talk from many American sources. “A recession in the year ahead seems less likely than it appeared at the start of 2023, since interest rates are trending lower, gas prices are down from last year, and incomes are growing faster than inflation,” said Bill Adams, chief economist at Comerica Bank. But he admitted that economists on average “expect the US economy to grow just 1% in 2024, about half its normal long-run rate, and a significant slowing from an estimated 2.6% in 2023.” So no recession at best, but virtual stagnation in 2024. “This is less a recession and more of a growth stop,” said Rajeev Dhawan, an economist at Georgia State University.

In the rest of the G7 economies, things look worse. The German economy declined 0.3% in 2023 and could well dive further this year, with Germany’s manufacturing industry contracting at a 6-7% yoy rate. Both the French and UK economies have turned negative in the last quarter of 2023. It’s the same for Canada and Japan, while Italy is stagnating. And there are several other advanced capitalist economies already in recession – Netherlands, Sweden, Austria and Norway. In the so-called emerging economies, many have slowed down considerably from any recovery burst in 2022 after the end of the pandemic slump of 2020.

Inflation rates are falling from their peaks in 2022 as supply blockages and weak manufacturing recover a little after the pandemic kept supply and international trade down. Food and energy prices have fallen sharply in 2023. But the damage has been done. On average, prices for most people in the advanced capitalist world have risen 20% since the end of the pandemic (and are still rising). It’s even worse for many poor countries and in many middle-income economies like Argentina (150%) and Turkey (50%). As a result, real incomes for average households have fallen since 2019, in effect, the biggest drop in living standards for decades. Moreover, inflation could start to rise again as the recent attacks on shipping in the Red Sea as Israel’s destruction of Gaza and its 2m people begins to spill over across the energy-rich Middle East.

The World Bank sums it up in its latest report. There may be no recession in the US, but “the global economy is on track for its worst half-decade of growth in 30 years”.

Behind this slowdown, the World Bank identifies the slowdown in productive investment by the major economies in value-creating jobs and incomes.

Marxists would add that behind that investment slowdown is the historic low level of profitability for global capital (excluding the tiny minority of tech and energy giants).

The World Bank expects GDP growth in the world economy to expand just 2.4 per cent in 2024— down from 2.6 per cent last year (and that includes India, China, Indonesia etc which will grow at 5-6%). This would mark the third year in a row where growth would prove weaker than the previous 12 months. “Without a major course correction, the 2020s will go down as a decade of wasted opportunity,” said Indermit Gill, the World Bank’s chief economist and senior vice president.

Global trade growth in 2024 was expected to be only half the average in the decade before the pandemic. Global goods trade contracted in 2023, marking the first annual decline outside of global recessions in the past 20 years. The recovery in global trade in 2021-24 is projected to be the weakest following a global recession in the past half century.

Advanced economies were expected to see growth of just 1.2 per cent, down from 1.5 per cent in 2023. Many developing economies remain hamstrung by “more than half a trillion dollars of debt overhang” and shrinking ‘fiscal space’ (ie ability of governments to spend on social needs). Food insecurity leapt in 2022 and remained high in 2023.

The WEF report notes the danger to capitalism of what it calls ‘societal polarisation’, in other words, growing divisions between rich and poor caused by economic stagnation that leads to loss of support for existing parties of capital and their political institutions.

The report does not mention the extent of social inequality in the world in 2024. But every year at Davos, Oxfam presents its ‘alternative’ report on the state of world inequality. It is a staggering condemnation of the failure of the capitalist order to meet the social needs of the vast majority of humanity. In its report this year, entitled Survival of the Richest,

Oxfam notes that extreme wealth and extreme poverty have increased simultaneously for the first time in 25 years. “While ordinary people are making daily sacrifices on essentials like food, the super-rich have outdone even their wildest dreams. Just two years in, this decade is shaping up to be the best yet for billionaires —a roaring ‘20s boom for the world’s richest,” said Gabriela Bucher, Executive Director of Oxfam International.

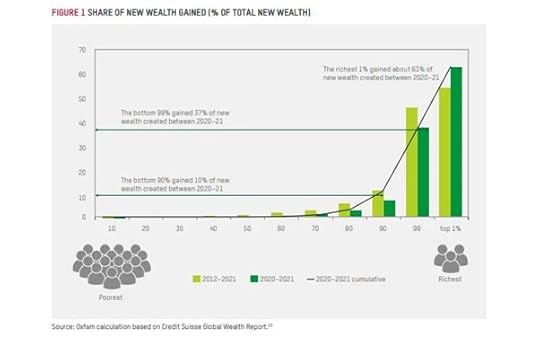

During the pandemic and cost-of-living crisis years since 2020, $26 trillion (63 percent) of all new wealth was captured by the richest 1 percent, while $16 trillion (37 percent) went to the rest of the world put together. A billionaire gained roughly $1.7 million for every $1 of new global wealth earned by a person in the bottom 90 percent.

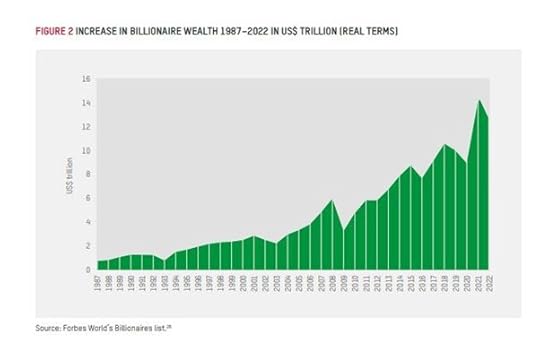

Billionaire fortunes have increased by $2.7 billion a day! This comes on top of a decade of historic gains —the number and wealth of billionaires having doubled over the last ten years.

At the same time, at least 1.7 billion workers now live in countries where inflation is outpacing wages, and over 820 million people —roughly one in ten people on Earth— are going hungry. Women and girls often eat least and last and make up nearly 60 percent of the world’s hungry population. Oxfam quotes the World Bank as saying, “we are likely seeing the biggest increase in global inequality and poverty since WW2.”

Entire countries are facing bankruptcy, with the poorest countries now spending four times more repaying debts to rich creditors than on healthcare. Three-quarters of the world’s governments are planning austerity-driven public sector spending cuts —including on healthcare and education— by $7.8 trillion over the next five years.

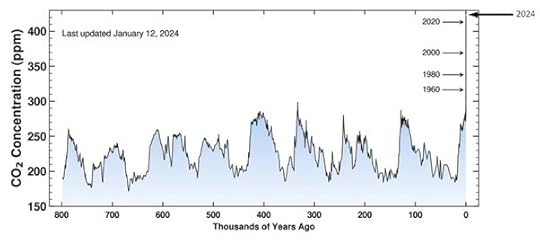

As usual, the WEF in its report offers no policy solutions to reverse or even curb this grotesque level of inequality – not even a wealth tax. Instead, the top risk issue for those surveyed by the WEF is ‘extreme weather’. The economic consequences of global warming and climate change are what worries the corporate and government leaders at Davos. It means damage to business and infrastructure – and having to deal with millions forced to leave their homes and migrate.