Michael Roberts's Blog, page 14

April 1, 2024

Bitcoin 24

Last week, Sam Bankman-Fried was sentenced to 25 years in prison. He ran the highly successful FTX bitcoin hedge fund that supposedly made millions for his clients. But Friedman was exposed and convicted of stealing $8 billion from his FTX customers. He was found to have siphoned billions in customer funds into FTX’s sister hedge fund, Alameda Research, to keep it solvent and line his pockets with his clients’ money.

Friedman lived the good life, spending more than $200m in Bahamas real estate and in speculative investments. “Sam Bankman-Fried perpetrated one of the biggest financial frauds in American history – a multibillion-dollar scheme designed to make him the king of crypto – but while the cryptocurrency industry might be new and the players like Sam Bankman-Fried might be new, this kind of corruption is as old as time,” the Manhattan US attorney Damian Williams said after the conviction. “This case has always been about lying, cheating and stealing and we have no patience for it.”

Currently bitcoin and other crypto currencies have been experiencing a massive rise in price. Supposedly, cryptocurrencies have now escaped their image of involving fraudsters, scams and wild speculation to join the ‘respectable part’ of the financial world. The Friedman case has shown that to be a joke – along with a succession of other such ‘Friedmans’ over the last decade of the rise of crypto.

I wrote on blockchain technology and the crypto craze several years ago. I argued then that although bitcoin supposedly aims at reducing transaction costs in internet payments and completely eliminating the need for financial intermediaries like banks, I doubted that such digital currencies could replace existing fiat currencies and become widely used in daily transactions – as their proponents forecast.

Money in modern capitalism is no longer just a commodity like gold but instead is a ‘fiat currency’, either in coins or notes, or now mostly in credits in banks. Such fiat currencies are accepted because they are issued by ‘fiat’ by governments and central banks and subject to regulation. In contrast, bitcoin, conceived by an anonymous and mysterious programmer Satoshi Nakamoto just over a decade ago, is not localized to a particular region or country, nor is it intended for use in a particular virtual economy. Because of its decentralized nature, its circulation is largely beyond the reach of direct regulation or monetary policy and oversight that has traditionally been enforced in some manner with localized private monies and e-money.

Now for technology enthusiasts (and also for those who want to build a world out of the control of state machines and regulatory authorities) this all sounded exciting. Maybe communities and people could make transactions without the diktats of corrupt governments and control their incomes and wealth away from the authorities – it might even be the embryo of a post-capitalist world without states.

Such futurist hopes have been dashed. Bitcoin’s value is not backed by any government guarantees, by definition. It is backed just by ‘code’ and the consensus that exists among its key ‘miners’ and holders. As with fiat currencies, where there is no physical commodity that has intrinsic value in the labour time to produce it, the crypto currency depends on the trust of the users. And that trust varies with its price relative to a state-controlled fiat currency like the dollar. Its price is measured in dollars or in what is called a ‘stable coin’ tied to the dollar. Indeed, while the cryptocraze has exploded, the US dollar has entrenched itself ever more firmly as the world’s premier currency (67% of all settlements, followed by the other fiat currencies, the euro, the yen and yuan).

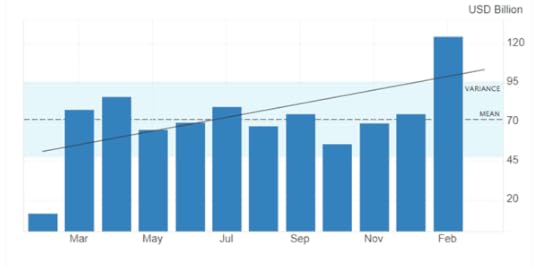

The price of bitcoin measured in fiat currencies like the dollar has violently fluctuated, but more recently has rocketed to stratospheric heights as financial assets shoot up to record highs in the expectation of falling interest rates and economic recovery. Indeed, for that very reason, cryptocurrencies are no closer to achieving acceptance as an everyday means of exchange.

So far, its main use has been for speculation. It has become yet another form of what Marx called ‘fictitious capital’ – a financial fiction for real value. The Friedman case shows that nothing has changed from when Marx wrote about “a new financial aristocracy, a new variety of parasites in the shape of promoters, speculators and simply nominal directors; a whole system of swindling and cheating by means of corporation promotion, stock issuance, and stock speculation.” With the rise of fictitious capital: “All standards of measurement, all excuses more or less still justified under capitalist production, disappear.” …. since property here exists in the form of stock, its movement and transfer become purely a result of gambling on the stock exchange, where the little fish are swallowed by the sharks and the lambs by the stock-exchange wolves.”

The nature of cryptocurrency culture was summed up by a firm led by Lord Hammond, a former UK finance minister, sponsoring a party to promote crypto where guests were served sushi off two scantily clad models.

Finance capital is ever-ingenious in inventing new ways of speculation and swindles. In the last 20 years, ‘financial fictions’ have been increasingly digitalized (SPACS, NFTs). High frequency financial transactions have been superseded by digital coding. But these technological developments have mainly been used to increase speculation in the financial casino, leaving regulators behind in the wash.

Rather than protecting investors from these predatory crypto schemes, financial regulators and enforcers have only stepped when “it was time to pick up the pieces and comb through the rubble of millions of people’s shattered investments”. Politicians, funded by crypto companies have helped to block regulation. The US Congress has been deadlocked on bill after bill as industry interests pressure them to codify the current state of lax regulation with carve-outs and loopholes. “The crypto industry argues this will allow for continued “innovation” – despite little innovation to date from the sector, aside from finding new and inventive ways to scam people out of their money.”

Yet again, regulation has failed to stop financial speculation, crashes and swindles. “Regulators and lawmakers have failed to make any changes to proactively protect the public, while allowing crypto firms to advertise and recruit new customers who seem far more likely to wind up as victims of yet another collapse as they are to become the next crypto-millionaires. How many people will have to lose how much money before we stop believing the lies from an industry that has preyed on people’s trust and hopes for financial miracles, only to dash them on the ground in failure after failure?”

Back to Marx here. “The two characteristics immanent in the credit system are, on the one hand, to develop the incentive of capitalist production, from enrichment through exploitation of the labour of others, to the purest and most colossal form of gambling and swindling.” So the finance sector carries on just as before, engaging in speculation and regulators cannot and do not stop them.

The answer is not regulation (before or after the event), but the banning of fictitious capital investment. Close down hedge funds, bitcoin exchanges and exchange trade funding. Instead, banking should be a public service for households and small companies in order to take deposits and make loans – not funding for a massive financial casino where criminals and swindlers gamble away our livelihoods.

March 28, 2024

The state of capitalism

The book, The State of Capitalism, is an ambitious work. Written by the NAMe Collective with the lead from Professor Costas Lapavitsas from SOAS University, London, it seeks to analyse all aspects of capitalism in the 21st century from a Marxist perspective. It has been widely praised by the likes of Yanis Varoufakis and Grace Blakeley, leading rock stars of leftist economics.

According to the authors, the book “is the outcome of collective writing that combines different types of knowledge and experience, while still finding a common voice. For several years, the European Research Network on Social and Economic Policy (EReNSEP) has sustained itself through the voluntary efforts of its members…. the outcome of collective writing that combines different types of knowledge and experience, while still finding a common voice.”

In this review, I cannot possibly cover all parts of the book’s analysis of modern capitalism. So I shall concentrate on where I agree or disagree with what I shall call ‘the Collective’ and its analysis and conclusions.

The book starts with an overview of capitalism in this century. The Collective argues that capitalism is much weaker than in the 20th century. And the roots of this weakness lie in a slower accumulation of capital, particularly since the ‘interregnum’ of the Great Recession of 2007-9. “Core economies across the world are marked by weak production and predatory finance. Financialisation is entrenched, and finance remains the chief beneficiary of government policies as well as the source of fabulous wealth for an oligarchic sliver of society. At the historic sites of advanced capitalism, growth is feeble, employment is precarious and poverty endemic, while income differentials continue to widen, creating vast social fractures. Neoliberal financialised capitalism, dominant for more than four decades, is showing signs of exhaustion.”

Immediately, we can see that the Collective designates the main (new) feature of modern capitalism: financialisation. This is a dominant theme throughout the book. For the Collective, the main cause of the growing weakness in capitalist development in this century can be found in financialisation: “At the root of this lay the weakness of capitalist accumulation in core countries, exacerbated by the advance of financialisation for several decades; the writing had been on the wall since the Great Crisis of 2007–09.”

Now as regular readers of this blog will know, I find the term ‘financialisation’ either too generalised and/or problematic. In particular, see the excellent paper by Stavros Mavroudeas. As the Collective admits: “The vast literature on financialisation in the social sciences has not produced an agreed meaning for the term.” The authors define it as “a historical transformation of mature capitalism reflecting, first, the extraordinary growth of the financial sector relative to the rest of the economy and, second, the spread of financial practices and concerns amid non-financial enterprises and other fundamental agents of capitalist accumulation.”

If by this, the Collective means that the financial sector in capitalist economies has grown in size and in influence over the productive sectors and as such there has been a rise in the share of total profits going towards financial activities as opposed to productive activities, then this is undoubtedly true. But I think the Collective means more than that. Now in modern capitalism: “Wealth accrual took advantage of proliferating financial expropriation, a characteristic feature of predatory financialised capitalism.” And in particular, the gigantic shock of the 2008-9 Great Recession “sprang out of the aggressive financialisation of core countries during the preceding two decades.” So the crisis in capitalism in the 21st century is mainly due to the “unravelling of financialised capitalism that began in the late 2000s.” It is not primarily due to any deterioration in the accumulation of productive capital.

Indeed, the Collective reject Marx’s law of declining profitability as being relevant to the crises of modern capitalism. Their rejection is shrouded in a contradictory and confusing analysis of the law and its impact on capital accumulation. First, we get an electic view: “The anaemic performance of accumulation in the 2010s was partly due to the suppression of aggregate demand as core states implemented austerity policies, but even more significant (my emphasis) was the underlying weakness on the side of production.” So it’s both.

According to this eclectic view, in considering aggregate demand and supply, for Marxist political economy, “the two sides cannot be strictly separated”. But the process of capitalist accumulation is presented as one where production takes place “by forming expectations of demand and produce output based on costs deriving heavily from real wages and technology. Enterprise plans help determine aggregate demand in the form of both investment and consumption, but if expected demand does not materialise, production is curtailed. Moreover, the drive to innovate and adopt new technologies is negatively affected when demand is weak over a long period of time.” In this analysis, there is no mention of the possibility that a decline in supply, investment or profit might cause a decline in aggregate demand. And yet, the Collective goes on to say that “capitalist economies rest primarily on production, where value and surplus value are generated. The side of production is ultimately the determining factor in the overall performance of capitalist accumulation”(again my emphasis). Confusing.

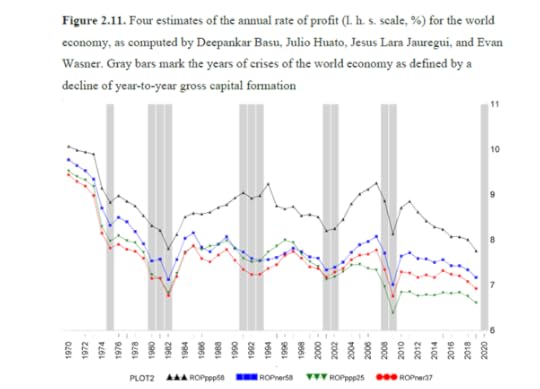

The Collective then tackles Marx’s law of the tendency of the rate of profit to fall and its relevance to crises of accumulation and production in modern capitalism. On the one hand, they say that “the variable that most usefully sums up the underlying condition of aggregate supply is the average rate of profit, particularly that of non-financial enterprises. The point of departure for the analysis of accumulation weakness in the 2010s is the conduct of profitability before and after the Great Crisis of 2007–09.”

But then the Collective tells us that Marx’s law analysing the rate of profit is actually “ambiguous”. You see, “the rise in the rate of exploitation would boost the rate of profit, and the impact might be even bigger if the value composition fell. If, on the other hand, the value composition rose, it would give a downward push to the rate of profit that could potentially exceed the boost from the rising rate of exploitation, thus bringing the rate of profit down. Once again, however, within reasonable assumptions about magnitudes, a rise in productivity would probably raise the average rate of profit.” So the Collective accepts the usual theoretical dismissal of Marx’s law that it is ‘indeterminate’.

Again, those of you who are regular readers of this blog, know that this is nonsense. Simply put, Marx argues that over time capitalist accumulation takes the form of a rising organic composition of capital (ie rising investment in means of production relative to investment in employing labour). If that is right, then there will be a tendency for the average rate of profit to fall. Yes, there are counteracting factors like a rising rate of exploitation of workers, or possibly falling costs of the means of production; and in the national context, better profitability from trade and investment abroad or from the financial sector speculation (what Marx called fictitious capital). BUT these counteracting factors are not sufficient over time to reverse the downward pressure on the rate of profit. This is all well explained by Marx in Capital Volume 3, Chapters 13-15 and developed by many Marxist authors since.

Indeed, if you accept that the law is ‘ambiguous’ or ‘indeterminate’, then Marx’s law is useless as a tool for analysing capitalist accumulation and crises of production. That’s why, in essence, the Collective resorts to alternative theories. First, they argue that the rate of profit only falls because of rising wages (this is the classic neo-Ricardian view); and second, it only falls when the growth in productivity of labour slows or falls.

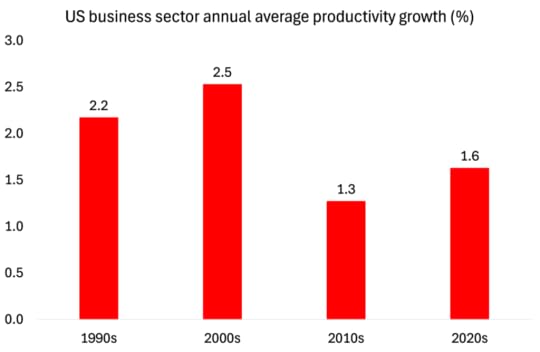

And here we get yet another confused position by the Collective. They argue that “labour productivity is the driving engine of capitalism, the means through which profits rise and enterprises win the battle of competition in the medium to long run.” Really? Is not the driving engine of capitalism profits, not productivity? The Collective’s analysis has reversed Marx. Marx’s theory of accumulation and crises reckons that the profitability of capital ultimately decides the rate of accumulation in the means of production and employment, and the rate of accumulation (or investment) then drives the productivity of labour. The key contradiction for Marx is that the drive for higher profitability through mechanization may lead to higher productivity, but it also leads to falling profitability. So the accumulation process founders. For Collective, it’s the other way round: “the trajectory of the average rate of profit, which reflects (my emphasis again) the underlying strength of accumulation” and “could be usefully analysed through the movement of real wages and the productivity of labour.” So profit and profitability depend on the productivity of labour, not vice versa as in Marx.

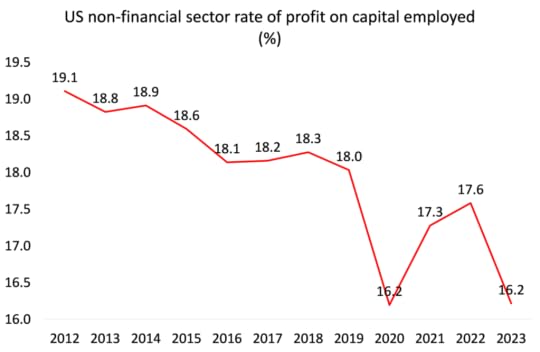

This leads the Collective to argue that while the growth in capital accumulation (investment in means of production) has slowed over the last four decades, this has not been due to any fall in profitability, a la Marx. Indeed, they claim that there has been a ‘rather level trend’ in profitability “– perhaps rising gently – while following a cyclical path, broadly in line with the overall fluctuations of the economy.” So Marx’s law is both faulty theoretically and disproven empirically.

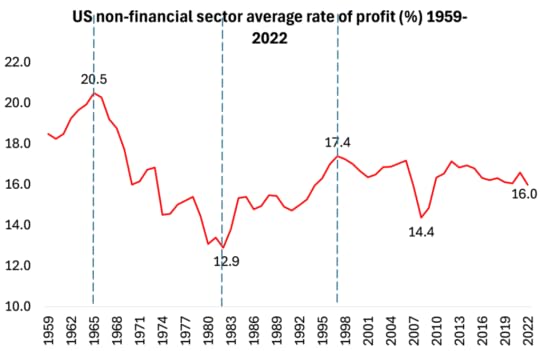

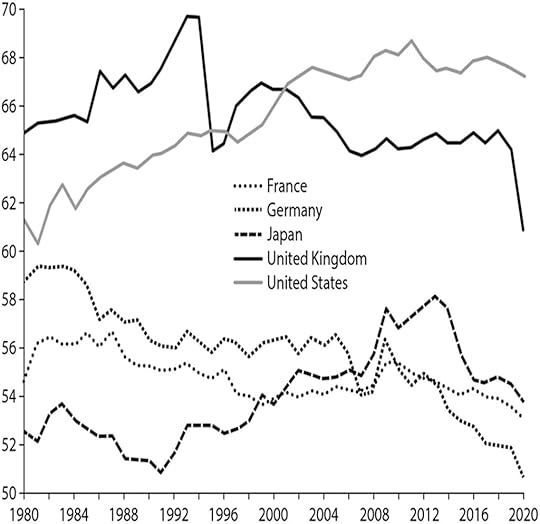

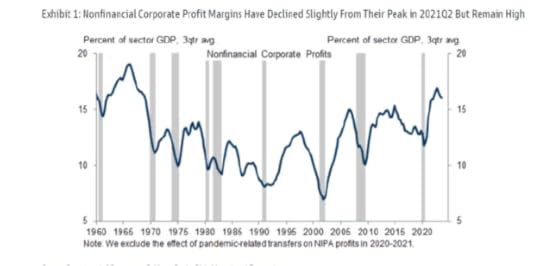

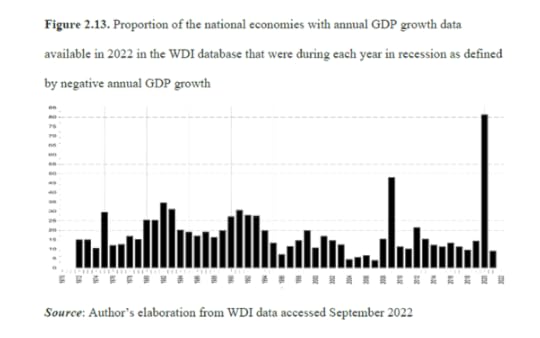

I could spend some time arguing that this is wrong. But consider the Collective’s graph above in the book on the profitability of the US non-financial sector. It starts in 1980, thus leaving out the huge drop in profitability from the mid 1960s to the early 1980s. It’s not quite clear what method and sources have been used but even so, the graph does show a peak in profitability in 2006 before the Great Recession and a downward trend since. But if we extend the data further back, using the US Federal Reserve’s own measure of non-financial profitability, they tell a clearer story.

For more on useful measures on profitablity, see https://fredaccount.stlouisfed.org/public/dashboard/53250 and also see the work of Basu-Wasner on the rate of profit. https://dbasu.shinyapps.io/Profitability/

Having rejected (reversed) Marx’s law of profitability, the Collective resumes its argument that it was low productivity not low profitability that was the key to the weakness of capitalism in the 21st century. “During the decades of financialisation, flimsy productivity growth attenuated the ‘internal mechanism’ in core countries.” Swinging away from profitability, the Collective focuses on aggregate demand as being the problem. “Aggregate demand in core countries was persistently weak throughout the 2010s as the private sector registered poor results in both investment and consumption, and as several governments pursued policies of fiscal austerity.” This is classic Keynesianism.

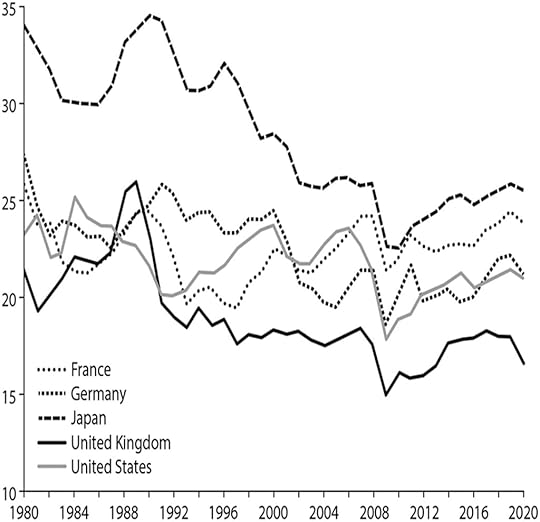

Aggregate demand is composed of both investment and consumption demand. The Collective argues that the perceived weakness of aggregate demand is shown in the fall in investment as a percentage of gross domestic product (GDP) .

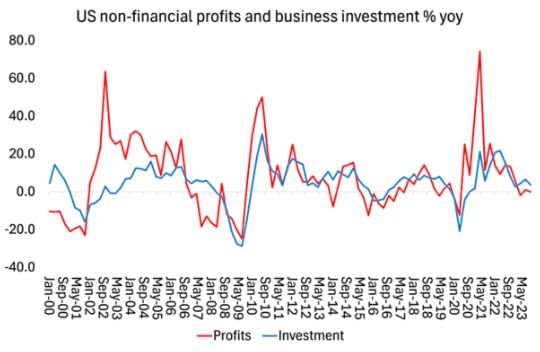

But was this decline in investment to GDP and for that matter, slowing investment growth over the last four decades due to inadequate demand and/or slowing productivity growth, or was it due to weakening profitability, particularly since the late 1990s and particularly in productive sectors? – as the Fed’s graph above shows. The evidence from many Marxist scholars would argue that it is profitability that was key. Note in the graph below how close the correlation is between movements in the rate of profit and movements in business investment.

The Collective goes on to argue that “the deficiency of private aggregate demand was also visible in consumption as a proportion of GDP”. But look at the chart they provide for this.

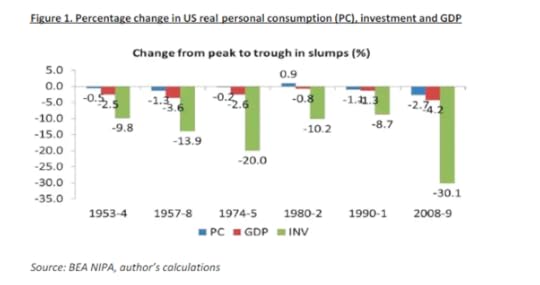

In the chart, there is no significant fall in consumer demand from the 1980s, unlike in investment. US consumption to GDP rises throughout, and all the other countries (except Germany) have a steady ratio until the Great Recession. And I have shown that in every crisis of capitalism since 1945, it is investment that collapses first, not consumption, which generally stays flat. So ‘inadequate demand’ comes from investment, not consumption, in the capitalist business cycle; and investment is driven by profitability (previous and expected).

For the Collective, the recent weakness of capitalism is to be explained mainly by “the relative retreat of financialisation in the 2010s.” But again, the chart of non-financial sector debt to GDP offered as evidence does not confirm this feature.

Over the period 2002-2020, US NFC debt to GDP rises. Germany and Japan’s ratio in 2020 is the same as in 2002. France’s rockets. Only the UK shows a significant decline. The Collective says that “Financial speculation involving the working class of the USA – often its poorest metropolitan layers – and pivoting on shadow finance, was the prime culprit of the huge bubble that led to the collapse of 2007–09 and the ensuing global crisis. The uniqueness of this development in the history of capitalism cannot be overstressed.” Well, just maybe it is being overstressed.

In my view, the Collective’s claim that the current weakness of capitalist accumulation and economic growth; and the recent major crises are the result of low productivity growth, inadequate aggregate demand and the collapse of financialisation is superficial at best, confusing and just wrong (at least in Marxist terms).

The Collective devotes a lot of space and chapters to exploring the rise of the financial sector, ‘shadow finance’, state-backed fiat money (QE), and the propping up of overindebted ‘zombie companies’ with yet more debt. This is a valuable account. But the question for me remains: why have these components of ‘financialisation’ expanded so much in the last four decades? For me, the answer lies in the growing weakness of productive investment as driven by the long-term decline in profitability. This has forced the monetary authorities and the state to intervene to try and prop up capitalist accumulation and ameliorate the impact of slumps in production by ‘printing’ money and increasing credit/debt.

On this question, the Collective heavily criticises Modern Monetary Theory, correctly in my view, for arguing that the expansion of money and credit by the state will not be harmful to the capitalist economy. “First, MMT underestimates the risk of financial asset speculation inherent to expansionary monetary policy.” And “most significant, MMT largely ignores the importance of transformative interventions by governments on the side of aggregate supply and focuses primarily on aggregate demand (!). MMT proposals aim at changing the distribution of income without fundamentally changing the structure of production.” Indeed. And yet, the implication of the Collective’s own analysis that crises in modern capitalism are mainly a result of weakness in aggregate demand would also suggest that fiscal spending and printing money to boost aggregate demand could avoid or solve crises under capitalism.

The Collective’s analysis also leads to a confused explanation of the post-pandemic inflationary spike. The Collective starts by saying that “the return of inflation was clearly due to the support of aggregate demand delivered by core states in 2020–21.” But then adds “At a deeper level, however, it reflected the underlying weakness of the supply side and the entrenched malaise of accumulation discussed in previous chapters.” Which is it? The Collective eventually makes a choice. “Rising inflation indicated that the poor performance of capitalist accumulation in core countries after the Great Crisis of 2007–09 was not simply due to persistent austerity compressing aggregate demand. The problem had to do with the underlying weakness of aggregate supply – it was structural and deep.” Indeed, but how does that square with the earlier argument that it was a lack of aggregate demand that was the underlying cause of capitalist crises and not any problem with the supply side?

The Collective concludes (correctly) that “The real issue, however, was the inability of aggregate supply to respond commensurately, and in this regard the Quantity Theory of Money has little to offer.” But then the Collective swings back: “Inflation in the 2020s was spurred by the boost to aggregate demand, particularly as the expansionary policies of core states were compounded by the lifting of Covid-19 restrictions in 2021, which facilitated the recovery of private expenditure.” But hold your horses; actually it was not that so much. Instead, “Rising inflation primarily reflected the inability of aggregate supply adequately to respond to recovering demand. In part, this was due to the disturbance of production networks across the world.” And guess what? “It was also due to the deep – and related – malaise of the production side in core countries manifested in poor profitability, low productivity growth, and the prevalence of zombie firms, as was discussed.” Indeed. But just in case readers do not remember the ultimate factor, “the inability of supply to respond was due to the underlying malaise of financialised capitalism.” Thus, we reach full circle, with no indication of where to start.

The question of imperialism and its nature in the 21st century is essential to understand. The Collective tackles this task vigorously. “The distinguishing feature of the classical Marxist theory of imperialism is that it connects the form and content of imperialism to the underlying economic interests of capital.” In analysing imperialism, the Collective revises its earlier view of financialisation. “The conduct of monopolistic non-financial enterprises is a pillar of contemporary financialization, but must be approached with caution. It is misleading, for instance, to think of the giant monopolies as constantly choosing between the sphere of production and the sphere of finance while seeking profits. There is no systematic evidence that the profits of non-financial enterprises are significantly skewed toward financial activities, even if financial skills and activities have grown among industrial and commercial enterprises.” Exactly. The evidence elsewhere shows that non-financial multi-nationals do not make most of their profits from financial activities but from traditional productive investment and the exploitation of their labour forces, at home and aboard.

In my view, the Collective is correct to reject the old notion of a ‘labour aristocracy’ in the core countries as it “has little persuasiveness in a world of rampant neoliberalism, with precarious employment and tremendous inequality within core countries.” But in turn, the Collective is dismissive of structuralist or ‘dependency’ theories to explain how the exploitation of the people in the peripheral economies by the multi-national of the imperialist countries is being accomplished. I have my own criticisms of those theories of imperialist exploitation.

But the Collective goes further. Marx’s theory of unequal exchange as applied to international trade is rejected as explaining the exploitation of the rich over the poor economies. “It is deeply problematic to attempt to analyse foreign trade and investment by deploying Marx’s schema of domestic profit-rate equalisation.” Apparently, “Dependency theorists struggled to provide a theoretically and empirically coherent explanation of the economic mechanisms through which resources are drained from the periphery. Perhaps the most popular accounts were ‘unequal exchange’ and the ‘super-exploitation of the labour power’, but neither is theoretically persuasive.” This rejection is not explained and yet there is plenty of recent work to show the relevance of Marx’s theory.

The Collective reckons that those old classical Marxist theories are out of date. There have been “significant changes in the development of capitalism since the time when Marx produced his theoretical work. In particular, the links between the circuits of industrial and financial enterprises were closely analysed by classical Marxists, for whom bank capital was even capable of dominating industrial capital, thus creating the novel form of ‘finance capital’. Financialisation again.

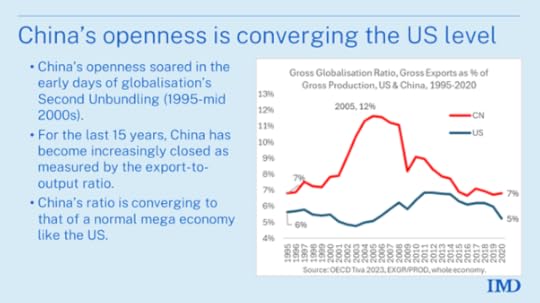

“During this period, which also witnessed the expansion of financialisation globally, the world economy was permeated by worldwide production networks or, as they are widely referred to in the literature, ‘global value chains’ or ‘global production networks’.” Yes, global value chains within companies have been an important route for transferring value or profit from the poor countries to the rich. But it is still the case that the bulk (two-thirds according to UNCTAD) of profit transference is through international trade and profit repatriation from FDI and portfolio investment, not through value chains within multi-nationals.

The Collective’s analysis of the rise of China is distinctly refreshing compared to the views of mainstream economics and compared to the majority of Marxist views. They argue that China is just another rising capitalist power with no distinctive features. I have critiqued these arguments about China ad nauseam in posts on this blog, so I won’t go over the points again here. But the Collective delivers an interesting angle on the nature of China: “both the mode and the extent of state intervention in China are profoundly different from those adopted by the USA. The US state provides support to financialised capitalism by drawing chiefly on command over fiat money, while also mobilising its intimate links with private corporations. The Chinese state has certainly catalysed the meteoric rise of China during the last four decades, but its interventions are based on direct ownership and command over both productive resources and finance. The difference is of great importance for the emerging hegemonic contest.”

Indeed, as I have argued, China’s economic success is not the product of capitalist accumulation for profit through markets, but of state-led investment for growth and social needs. Capitalists do not rule the development process in China: “There is no independent private capitalist class in China capable of directly challenging the command of the state over the core of the Chinese economy.” The Collective identifies where China is now. “For the time being, the Chinese ruling bloc appears to have decided to continue with public control over strategic productive forces, marshalled by the Communist Party. However, the pressure to move toward private ownership and control has far from disappeared. … If privatisation somehow prevailed within the ranks of the ruling bloc and a profit-driven bourgeois class emerged at the helm, it is hard to see how the Chinese challenge to US hegemony would be sustained.”

The Collective sees the profitability of capital in China as a key indicator – surprising given its rejection of profitability as relevant for the major capitalist economies. “An important factor is the changed outlook of non-financial enterprises, including the leading SOEs, in the period since the Great Crisis of 2007–09. The supply side of the Chinese economy has begun to exhibit symptoms of weakness, which are reflected in low profitability.” However, the Collective says this falling profitability is again due to slowing growth in labour productivity, not vice versa.

To conclude, the Collective reminds the reader of the aim of the book: to develop a clear analysis of capitalism today in order to see the way towards replacing it with socialism. What do they advocate? Democratic planning “with the state and the broader public sector taking a commanding role in production, consumption, and distribution. The balance of power in economic decision making must be altered accordingly, creating social foundations to confront the ecological crisis in a coherent and socially aware way, something that private capital is incapable of doing.”

The State of Capitalism is an exercise in hard analysis and there is much to learn and debate. In that sense, the book is a must read, even if I have disagreements on the Collective’s view on the causes of crises in capitalism, the nature of imperialist exploitation and the role of finance.

March 22, 2024

The IMF, Georgieva and Keynes

Current IMF chief Kristalina Georgieva is seeking a second five-year term as IMF managing director after being nominated by a string of European countries to lead the institution. In doing so, she recently delivered a number of speeches outlining what she sees the IMF will be trying to achieve over the rest of this decade.

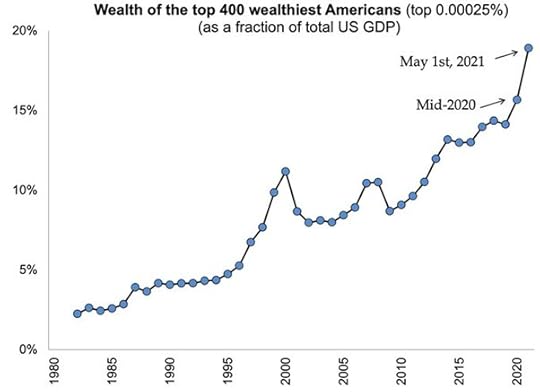

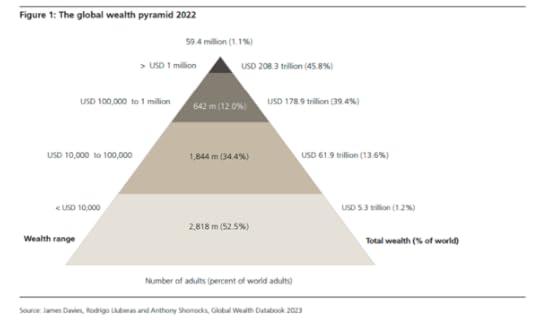

She said the major economies are experiencing slowing and low real GDP growth and, according to her, the reason for this is soaring inequality of wealth and income. “We have an obligation to correct what has been most seriously wrong over the last 100 years – the persistence of high economic inequality. IMF research shows that lower income inequality can be associated with higher and more durable growth,” she said.

It’s a new argument. Until recently, the IMF reckoned faster growth depended on higher productivity, free flows of capital, globalization of international trade and ‘liberalisation’ of markets, including labour markets (meaning weakening labour rights and unions). Inequality did not come into it. This was the neo-liberal formula for economic growth. But the experience of the Great Recession on 2008-9 and pandemic slump of 2020 seems to have delivered a sobering lesson to the IMF’s economic hierarchy.

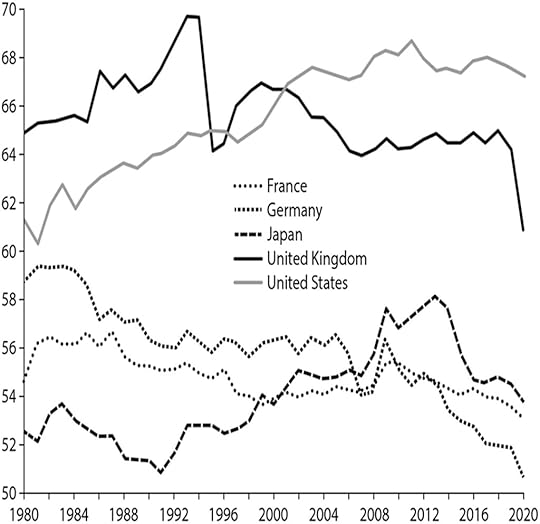

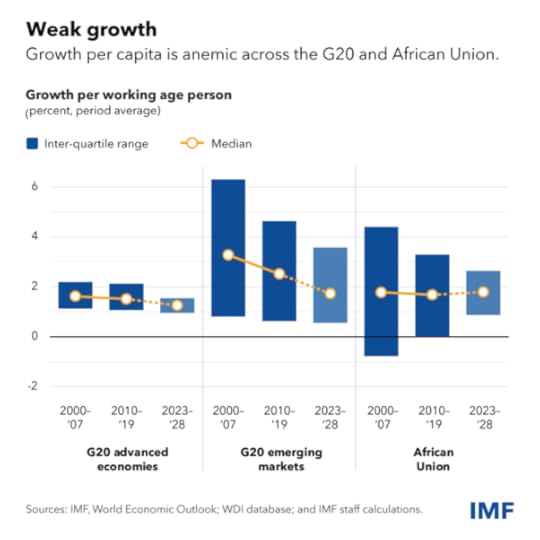

Now the world economy is suffering from “anemic growth”.

And globalisation is fragmenting along geopolitical lines—around 3,000 trade-restricting measures were imposed in 2023, nearly three times the number in 2019. Georgieva is worried: “Geoeconomic fragmentation is deepening as countries shift trade and capital flows. Climate risks are increasing and already affecting economic performance, from agricultural productivity to the reliability of transportation and the availability and cost of insurance. These risks may hold back regions with the most demographic potential, such as sub-Saharan Africa.”

Meanwhile, higher interest rates and debt-servicing costs are straining government budgets—leaving less room for countries to provide essential services and invest in people and infrastructure.

So Georgieva wants a new approach for her next five-year term. “With recent improvement to the global-near term outlook, G20 policymakers have an opportunity to rebuild policy momentum, setting their sights on a more equitable, prosperous, sustainable and cooperative future.” The previous neoliberal model for growth and prosperity must be replaced with ‘inclusive growth’ that aims to reduce inequalities and not just boost real GDP. The key issues now should “inclusion, sustainability, and global governance, with a welcome emphasis on eradicating poverty and hunger.”

The talk about ‘inclusive growth’ is not new, but it is from the IMF. How is this to be done? Here Georgieva refers us to the supposed solutions apparently provided by John Maynard Keynes during the Great Depression of the 1930s, in particular Keynes’ seminal essay Economic Possibilities for Our Grandchildren.

Let me remind readers that Keynes’ essay was originally based on a speech he made to students at King’s College, Cambridge in the depth of the 1930s depression. Keynes was very worried that his students were being attracted towards Marxist alternatives to the capitalist crisis. He saw the need to stop that by showing the capitalism would get out of its current mess and eventually deliver prosperity for all.

Georgieva argued that Keynes had been right to predict that technology gains would deliver an eightfold increase in living standards in 100 years’ time from 1931. Georgieva took this up and said the target for the IMF (over the next 100 years!) was to do the same ie. achieve an average nine-fold increase in living standards for 8bn plus people on the planet. But, says Georgieva, it can’t be done “unless we foster a fairer global economy.”

On the Keynes’ prediction for growth since the 1930s, Georgieva was not entirely accurate. Global per capita real GDP was $1958 in 1940 and reached $7614 in 2008. Given recent slow growth, average global per capita GDP could reach $11770 in 2030. But that’s a rise of only six times from the 1930s.

In her speech Georgieva admitted that “He [Keynes] was also too optimistic about how the benefits of growth would be shared. Economic inequality remains too high, within and across countries”. You don’t say! It was not that Keynes was too optimistic. He ignored completely the issue of inequality that Georgieva now wants to take up. He assumed that the major capitalist economies were equivalent to the world economy. And he made no distinction between the imperialist core and the poor periphery or between rich and poor inside a country. He did not refer to inequality at all – for him (mean) average growth was enough.

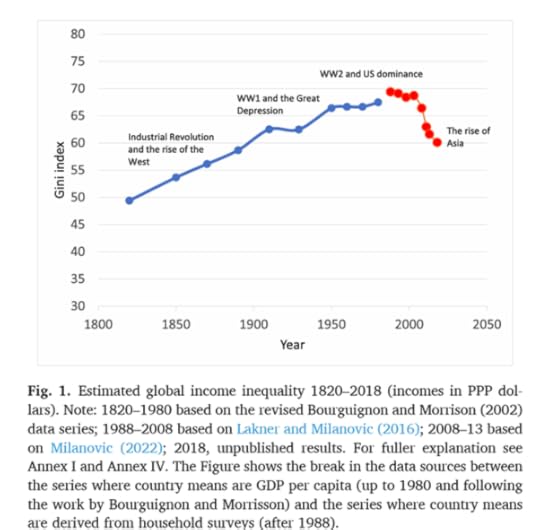

And what has happened to the inequality of global incomes since Keynes’ address? Just look at the latest analysis by global inequality expert, Branco Milanovic, in a new paper.

The global inequality index (Gini) has risen from around 50 in the early 19th century to about 66 in the 1930s, then hitting near 70 by the end of the 20th century. It has only fallen back since because of the rise of China, where over 900m Chinese have been taken out of World Bank defined poverty levels. The World Inequality Report (WIR) 2022 shows that after three decades of trade and financial globalisation, global inequalities remain extremely pronounced… “about as great today as they were at the peak of Western imperialism in the early 20th century.” ,(when Keynes did his address). Georgieva is arguing that prosperity and better living standards are only possible now by reducing inequality. But it appears that Keynes does not offer Georgieva any guidance on this at all.

So what do the IMF economists and Georgieva say needs to be done to reduce inequality? They do not propose a wealth tax on billionaires; they do not propose any effective measures to end tax havens for the super-rich and big corporations. Their only measure, it seems to me, is to back the recent vague agreement made to have a minimum corporate profits tax globally (with many attending loopholes). And they suggest higher tax rates at the top of the income distribution, the introduction of a universal basic income, and increased public spending on education and health.

As I mentioned in a previous post, leading inequality economist, Gabriel Zucman was invited to address the G20 finance ministers meeting in Brazil and asked to come up with detailed measures to tax the super-rich. Zucman admitted that “it may take years to get there for the super-rich” What is the likelihood that the G20 governments will agree to any measures against billionaires or tax havens?

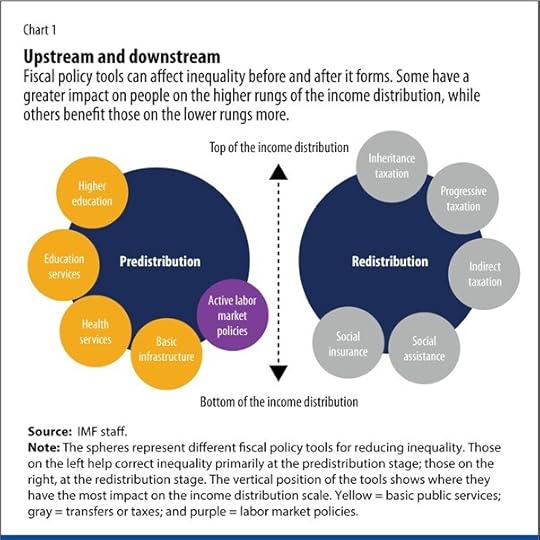

And anyway, as I argued in that post, all these tax measures are redistributive; ie they do not deal with the causes of inequality in the first place; they just aim at some redistribution afterwards. It’s like taking medicine that may take away some of your headache, but does nothing to stop the causes of the flu that keeps infecting you.

The IMF’s economists have recognised the distinction between pre-distributive measures to reduce inequality (of income only) and redistributive. But their suggested pre-distributive policies refer only to incomes and fail to address the economic structure of wealth inequality that in the past I have argued is key. Moreover, can they really expect education, health and infrastructure spending to be ramped up across a world economy as it currently operates?

Indeed, the leading inequality economists, Piketty, Saez and Zucman, recently concluded that “Given the massive changes in the pre-tax distribution of national income since 1980, there are clear limits to what redistributive policies can achieve.” That’s why these days, Piketty advocates going ‘beyond capitalism’ to break the back of inequality of income and wealth which, in my opinion is endemic to a social system where a small group of people own all the means of production and through banks and companies squeeze every last cent they can out of the rest of us.

Georgieva concludes that “In the years ahead, global cooperation will be essential to manage geoeconomic fragmentation and reinvigorate trade, maximize the potential of AI without widening inequality, prevent bottlenecks on debt, and respond to climate change.” Global cooperation? We are in a world where rivalry between the major economic powers is intensifying, with the US imposing trade tariffs, technology bans, and military measures against China , while Europe conducts a proxy war with Russia.

Highlighting Keynes’s maxim that “in the long run, we are all dead” in her speech, she said “He meant the following: instead of waiting for market forces to fix things over the long run, policymakers should try to resolve problems in the short run,” she said. “And it’s a call to which I for one am determined to respond – to do my part for my grandchildren’s better future. Because, as Keynes put it in 1942: ‘In the long run almost anything is possible.’” Well, yes, in the long run, ‘almost anything is possible’ but not necessarily for the betterment of humanity or the planet.

March 18, 2024

Profits: margins and rates

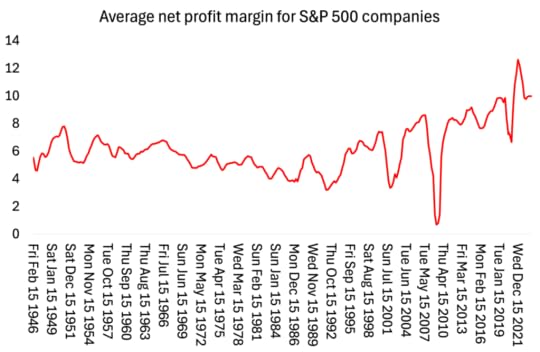

US corporate profit margins are at record highs, despite slowing price inflation and rising wage increases. Looking at the whole US economy, non-financial sector profit margins are at their highest level in the 21st century (over 16%) and not far short of the record levels of the ‘golden age’ of capitalist growth in the mid-1960s.

And just looking at the net profit margins (that’s after deducting all unit costs of production) for the top 500 companies in the US, it’s the same story.

Source: CSI

The evidence is overwhelming that the post-COVID inflationary spiral enabled many companies to hike the prices of their products considerably so that profit margins rose sharply because wage rises did not match price increases. Inflation bit into the living standards of most American households, but not into the profit margins of the US multi-nationals and mega firms.

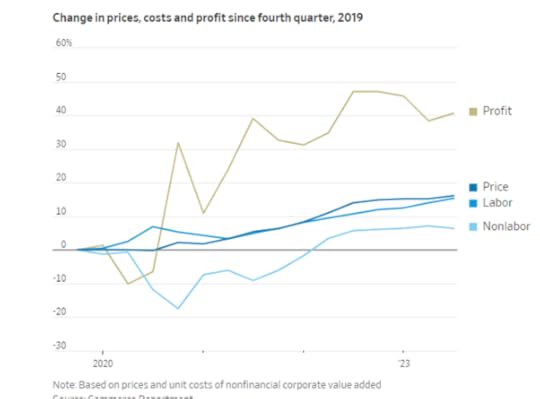

Since the end of 2019, prices in the US are up 17%, outpacing both labour and nonlabour costs. The result: profits grew by 41%. If profits had grown at the same slower rate as costs, that would have translated to a cumulative price increase of only 12.5%, and an average annual inflation rate roughly 1 percentage point lower.

But recent research has confirmed that the rise in corporate profit margins “appears mostly driven by a subset of high-markup firms.” The now well-known Weber-Wasner thesis on profit-driven inflation suggests that supply chain bottlenecks crimped competition by leaving some firms unable to service demand. And that enabled some firms to hike margins and prices. A Bank of England study found that yes, profits rose a lot in nominal terms. But so did costs. The study concluded that, other than in oil, gas and mining, profit margins up to 2022 behaved pretty normally. Another study by the IMF studying the eurozone concluded that “limited available data do not point to a widespread increase in mark-ups”. Profit-driven inflation seems to have been highly concentrated in a small number of firms and a small number of ‘systemic’ sectors, including extractive industries, manufacturing, IT & finance.

Nevertheless, Goldman Sachs economists are ecstatic at the prospect of profit margins staying up. They reckon that, although average wages are now rising faster than price rises, that will not hit profit margins because as inflation slows, so will interest rates (eventually) and thus the cost of servicing debt will fall to compensate for any squeezing of profits by wages.

Indeed, FactSet, a company that monitors the earnings of the top 500 US companies, reckons that the net profit margin for Q1 2024 will be 11.5%, which is above the previous quarter’s net profit margin of 11.2% and equal to the five-year average of 11.5%, with seven sectors expected to report net profit margins in Q1 2024 that are above their five-year averages, led by the Information Technology (25.1% vs. 23.3%) sector.

Goldman Sachs concludes that the US economy is set fair for 2024 as margins will continue to hold up, generating more investment and sustaining employment. But while the tech sector with its high margins and profits holds up the stock market and gives the impression of a widespread leap forward in profits, the rest of the US corporate sector is in the doldrums. In most sectors, margins are tight.

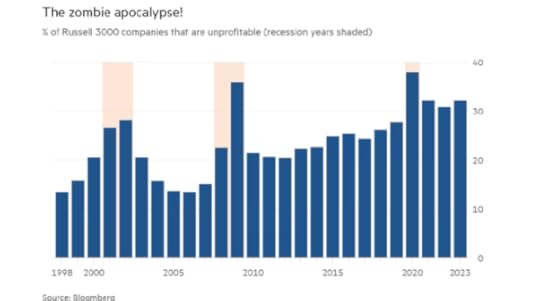

And most important, there is an issue of definition here. Profit margins are not the same as profits. Profit margins are the difference per unit of output between the price per unit sold and the cost per unit. But the profitability of capital should be measured by total profits against the total costs of fixed assets invested (plant, machinery, technology), raw materials and the wage bill. On that measure, outside of the ‘magnificent seven’ of US mega tech and social media corporations and energy companies, the rest of the US corporations are experiencing low profitability on their capital. Indeed, it has been estimated that 50% of quoted US firms are unprofitable.

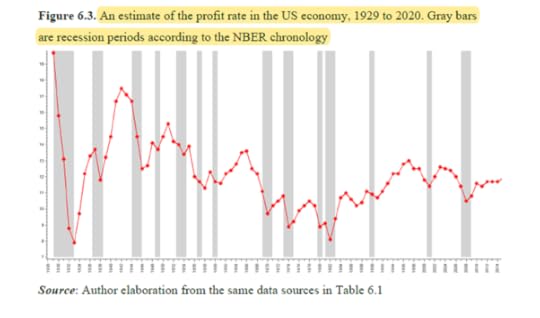

And if we calculate the average rate of profit on US non-financial sector capital, we find that there has been a general decline since 2012 (2023 is my estimate).

Source: FRED, author’s calculations (on request)

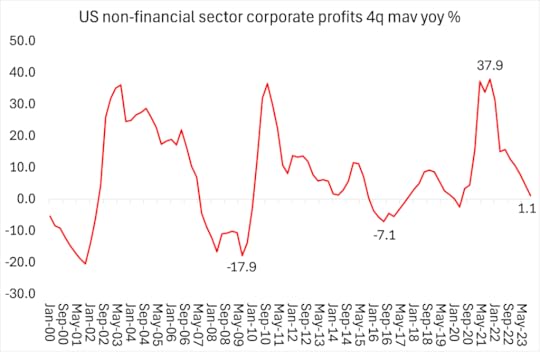

Profit margins may be high but total US non-financial sector corporate profits fell in the last quarter of 2023 and over last year, total profit growth has slowed almost to a stop.

Source: FRED, author calculations on request

And on another measure, total earnings (not margins) growth for the top 500 US companies is also slowing. FactSet forecast earnings in Q1 2024 to rise just 3.3%, down from near 6% in 2023.

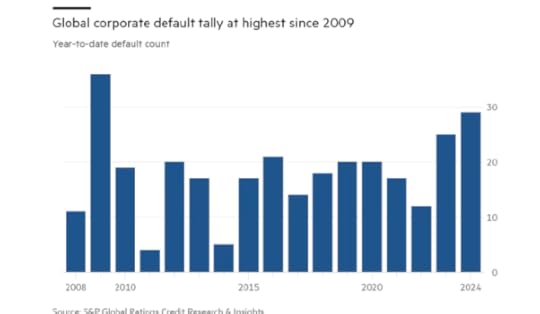

That explains why more companies have defaulted on their debt in 2024 than in any start to the year since the global financial crisis as inflationary pressures and high interest rates continue to weigh on the world’s riskiest borrowers, according to S&P Global Ratings. This year’s global tally of corporate defaults stands at 29, the highest year-to-date count since the 36 recorded during the same period in 2009, according to the rating agency.

Goldmans remains confident that an improving macroeconomic outlook and hopes that interest rates will decline in the second half of the year will see default rates stabilize. The credit rating agency, Moody’s, is not so confident. It expects the global speculative-grade default rate to continue to increase in 2024 well above the historic average.

And don’t forget the ‘zombies’, companies that are already failing to cover their debt servicing costs from profits and so cannot invest or expand but just carry on like the living dead. They have multiplied and survive so far by borrowing more – so are vulnerable to high borrowing rates..

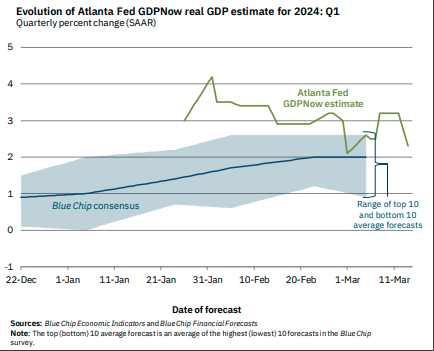

Looking ahead, US real GDP, by nearly all forecasts, is expected to slow from its 2.5% rise last year (and that measure is still dubious when we compare real GDP with real domestic gross income (GDI).

The New York Fed Nowcast forecast is for 1.78% annualized in this first quarter of 2024 just ending. And the Atlanta Fed GDP Now forecast is around 2.2%. Consensus forecasts are for 2%. That suggests that corporate revenue growth could slow further, leading to a fall in profits in Q1.

And remember, it is now well established that profits lead investment and then employment in a capitalist economy. Where profits lead, investment and employment follow with a lag.

Source: FRED, author calculations on request

Profitability has been falling from pre-pandemic levels and total profit growth has also stopped rising. Already that is having an effect on investment growth and employment. Rising margins do not show this.

March 15, 2024

Russians vote for Putin

Today Russians are set to head to the polls for their country’s presidential election over three days – with only one expected outcome. Incumbent President Vladimir Putin will win comfortably. The Russian president is elected by direct popular vote. If no candidate receives over 50% of the vote, then a second round is held between the two most popular candidates three weeks later. It’s the first time that multi-day voting has been used in a Russian presidential election, as well as the first allowing voters to cast ballots online.

There is no serious opposition candidate that can win. In the 2018 presidential vote, the Communist party runner-up Pavel Grudinin secured 11.8% of the vote, compared to Putin’s 76.7%. This time Nikolai Kharitonov of the Communist Party, Leonid Slutsky of the nationalist Liberal Democratic Party, and Vladislav Davankov of the New People Party are on the ballot paper. But all these candidates broadly support Putin’s policies, including the invasion of Ukraine. The vast majority of independent Russian media outlets have been banned and anyone found guilty of spreading what the government deems to be “deliberately false information” can be imprisoned for up to 15 years.

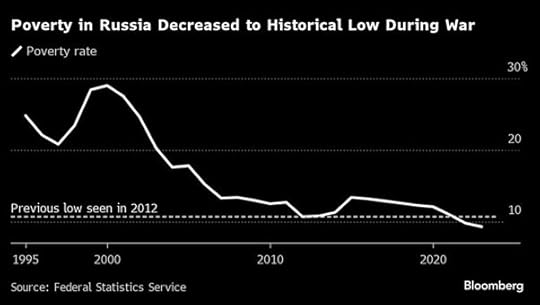

Putin is going to win not just because he has decimated any serious opposition forces, but because Russia’s invasion of Ukraine seems to have at least resigned support among Russian people, even if Russian lives are being lost. The main reason for that is because, contrary to the hopes and expectations of Western analysts, the Russian economy has not collapsed and Russian forces now seem to have the upper hand inside Ukraine.

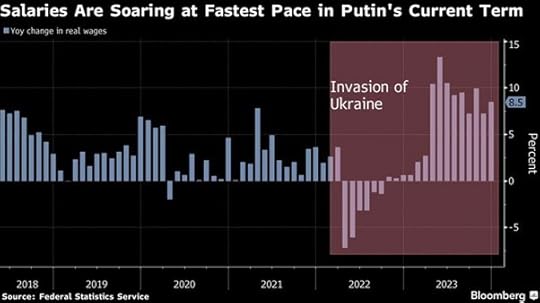

Russia’s war economy is holding up. Wages have soared by double digits, the rouble is relatively stable and poverty and unemployment are at record lows. For the country’s lowest earners, salaries over the last three quarters have risen faster than for any other segment of society, clocking an annual growth rate of about 20%.

The government is spending massively on social support for families, pension increases, mortgage subsidies and compensation for the relatives of those serving in the military.

The war in Ukraine has intensified an acute labour shortage as military recruitment draws workers out of the market and with half a million Russians fleeing the country. Putin said last month that employers had a deficit of 2.5 million people. That has benefited those Russian workers not in the armed forces with security of employment as managers are reluctant to let anyone go. The unemployment rate remains at a historic low and hiring expectations have soared to a record level.

However, inflation has picked up; accelerating in February to 7.7% yoy. It’s just that wages are rising faster. Average monthly wages in 2023 reached more than 74,000 rubles ($814), about 30% higher than two years ago. Before last year, Russia had not seen an increase in real disposable income of more than 5% for many years.

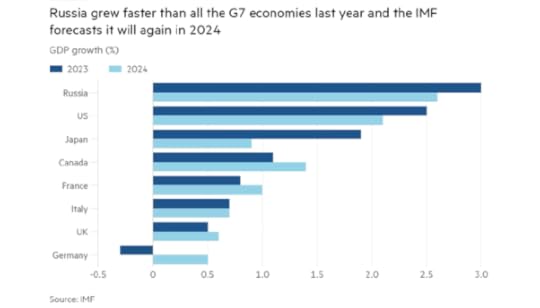

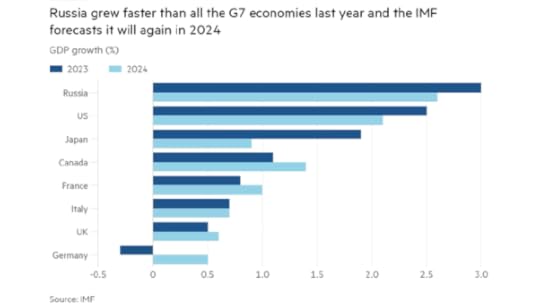

And Russia’s war economy is not plunging, but growing. The IMF forecasts real GDP growth in 2024 of 2.6%, outpacing the G7.

Over the past two years of war, Russia has managed to steer through sanctions, while investing nearly a third of its budget in defence spending. It’s also been able to increase trade with China and sell its oil to new markets, in part by using a shadow fleet of tankers to skirt the price cap that Western countries had hoped would reduce the country’s war chest. Half of its oil and petroleum was exported to China in 2023. And it became China’s top oil supplier in 2023, according to Chinese customs data. Chinese imports into Russia have jumped more than 60% since the start of war, as the country has been able to supply Russia with a steady stream of goods including cars and electronic devices, filling the gap of lost Western goods imports. Trade between Russia and China hit $240 billion in 2023, an increase of over 64% since 2021, before the war.

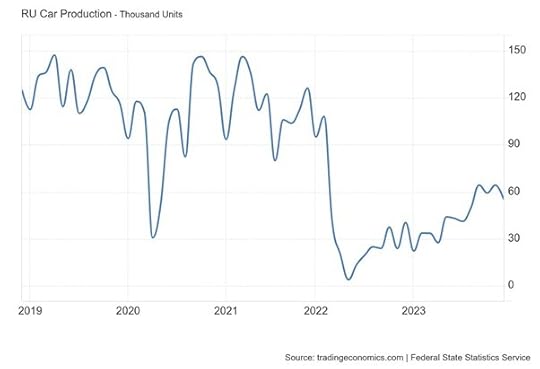

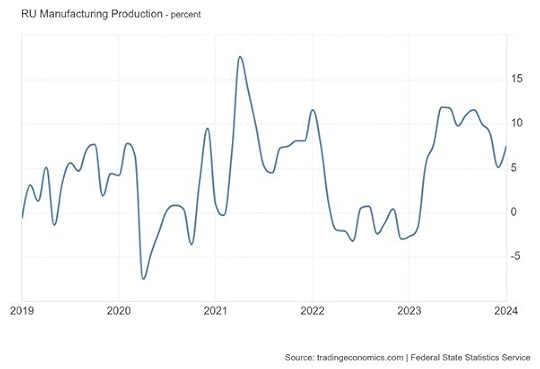

Contrary to Western forecasts, Russian industry has grown due to war-related production, while demand for domestic manufactures has also increased due to a fall in imports because of sanctions. The automobile industry – which was hit hard initially, as Western and Japanese car manufacturers left Russia en-masse – has been recovering strongly month by month, as Chinese companies have stepped in.

The level of capacity utilisation in the Russian economy has been generally rising and, according to various surveys, now stands at historically very high levels.

A war economy means that the state intervenes and even overrides the decision-making of the capitalist sector for the national war effort. State investment replaces private investment. Ironically, in Russia’s case this has been accelerated by Western companies’ withdrawal from Russian markets and by the sanctions. The Russian state has taken over foreign entities and/or resold them to Russian capitalists committed to the war effort.

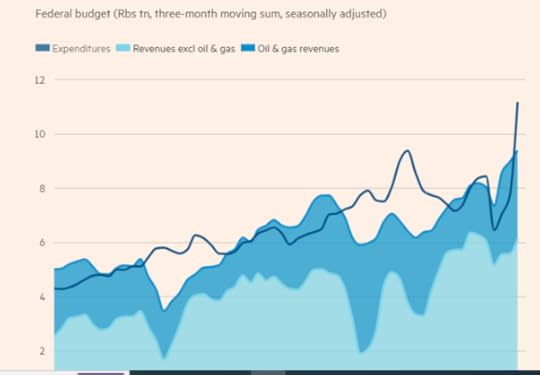

But Russia’s war economy will revert to capitalist accumulation when the war ends. The Russian finance ministry estimates that war-related fiscal stimulus in 2022-23 was equivalent to around 10 per cent of GDP. In that same period, war-related industrial output has risen 35%, while civilian production remained flat (until recently), according to research published by the Bank of Finland Institute for Emerging Economies.

Elevated social and war spending has also resulted in a yawning budget gap. The federal budget gap was 1.5 trillion rubles by the end of February, while the Finance Ministry has planned for a deficit of 1.6 trillion rubles for the whole of 2024 and Russia’s available wealth fund reserves have been already halved. After the election, Russian people can expect higher taxes, at least for higher earners.

And the Russian economy remains fundamentally natural resource linked. It relies on extraction rather than manufacturing. Mining accounted for around 26% of gross industrial production in July 2023, and three industries – extraction of crude petroleum and natural gas, coke and refined petroleum products manufacturing and basic metals manufacturing – made up more than 40% of the total. “The regime is resilient because it sits on an oil rig,” says Elina Ribakova, a non-resident senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics. “The Russian economy now is like a gas station that has started producing tanks.”

War production is basically unproductive for capital accumulation over the long run. And Russia’s potential real GDP growth is probably no more than 1.5% a year as growth is restricted by an ageing and shrinking population and low investment and productivity rates. The profitability of Russian productive capital before the war was very low.

The Russian war economy is well placed to continue the war for several years ahead if necessary, but when the war is over, Putin may face a significant slump in production and employment.

March 13, 2024

US economy: saved by immigrants

In 2023, US real GDP grew by 2.5% after inflation – much better than expected. This has been heralded by the media and mainstream economists as refuting the doomsayers that the US economy was heading into a slump. Now in 2024, the pundits claim that we can expect more of the same – reasonable real GDP growth but this time with a return to lower inflation and thus falling interest rates. Corporate bankruptcies will be avoided and the growing impact of new technologies and AI will raise the rate of growth in labour productivity, setting the scene for a strong period of improved living standards. Perfect.

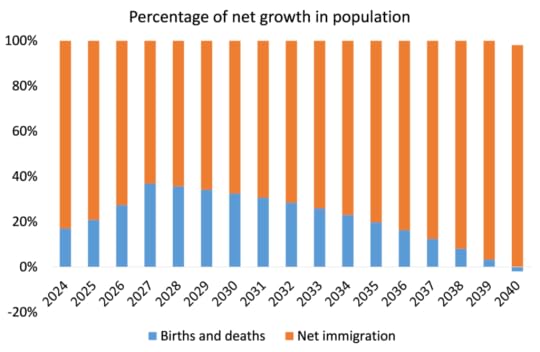

A key factor that has gone mostly unnoticed is that the pickup in US growth last year came from a sharp rise in net immigration. In simple terms, more workers generate more goods and services. A larger number of people earning paychecks means more consumer spending. And more people paying income tax on earnings boosts tax revenues. Last year, the US population rose by 0.9% in 2023, much faster than the US Census Bureau forecast of 0.5%. And the prime-age workforce participation rate—ie 25- to 54-year-olds—reached 83.5% in February, matching highs that hadn’t been seen since the early 2000s. Much of this is due to immigration. The US economy is outperforming in GDP terms mainly because of net immigration, twice as fast as in the Eurozone and three times as fast as Japan.

US population growth is set to slow over the next 30 years; in the US from 0.6% per year between 2024 and 2034 to just 0.2% between 2045 and 2054. So net immigration is going to be the only way that the US population will rise, particularly after 2040 when US fertility rates will fall below the rate that would be required for a generation to replace itself in the absence of immigration.

Unless net immigration continues to be strong, the only way economic growth in the major capitalist economies will be sustained will be through increased productivity of labour. But productivity growth in all the major economies has been slowing. And so for example, if the US workforce grows by say 0.5% a year and labour productivity rises by say 1.5%, then US real GDP growth will average 2% over the next decade. But more than likely, both the workforce and productivity growth will be less, so real GDP growth will be much less, especially if immigration is curbed. Moreover, this assumes no major slump in the economy during the rest of the 2020s.

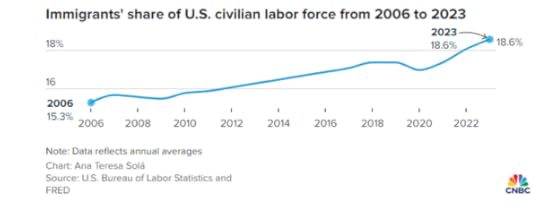

The US is home to more immigrants than any other country – more than 45 million people. Foreign-born workers now make up 18.6% of the civilian labour force in 2023, up from 15.3% in 2006. Without foreign-born labour, the US labour force would shrink because of lower birth rates and an aging workforce.

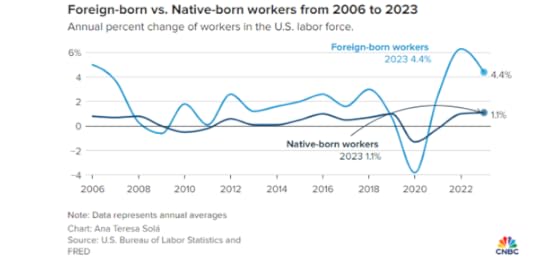

The growth rate of foreign-born workers was 4.4% in 2023 compared to native born workers of just 1.1%.

This net immigration is not by ‘illegals’. In 2021, only 4.6% of US workers were ‘unauthorised’, a share that’s pretty much unchanged since 2005. The Pew Research Center’s latest estimates indicate about 10.5 million undocumented immigrants live in the United States. That means the vast majority of foreign-born people living in the United States (77%) are here legally.

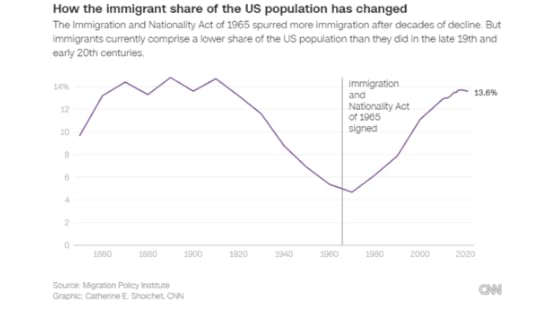

For decades, a national original quota system, passed by Congress in 1924, favoured migrants from northern and western Europe and excluded Asians. In 1965, the Immigration and Nationality Act created a new system that prioritised highly skilled immigrants and those who already had family living in the country. That paved the way for millions of non-European immigrants to come to the United States. In 1965, 9.6 million immigrants living in the US comprised just 5% of the population, according to the Migration Policy Institute. Now more than 45 million immigrants make up nearly 14% of the country. And most of these are skilled workers and their families.

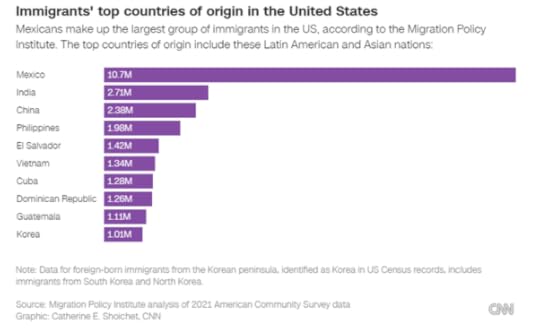

That 13.6% of the US population is about the same as it was a century ago. But over the years, that has been a significant shift in where immigrants to the US come from. Mexicans still represent the largest group of immigrants living in the United States. And the Mexico-US route is the largest migration corridor in the world. But the total number of Mexican immigrants living in the US has been on the decline for more than a decade. An estimated 10.7 million Mexican immigrants lived in the US in 2021, roughly 1 million fewer than the number a decade earlier.

Meanwhile, immigration from other countries, including India and China, has been on the rise.

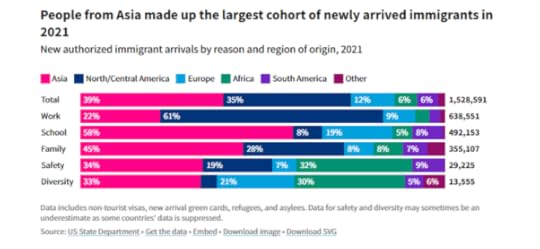

About 42% of all immigrants, or 638,551 people, came for work. And 39% of all immigrants were from Asia.

There has been a burst in immigration since the end of the pandemic which has helped sustain US GDP growth. “Reopening of borders in 2022 and easing of immigration policies brought a sizable immigration rebound, which in turn helped alleviate the shortage of workers relative to job vacancies,” Evgeniya Duzhak, regional policy economist at the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, wrote in a 2023 paper. About 50 percent of the US labour market’s extraordinary recent growth came from foreign-born workers, according to an Economic Policy Institute analysis of federal data. And even before that, by the middle of 2022, the foreign-born labour force had grown so fast that it closed the labor force gap created by the pandemic, according to research from the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco.

The influx of immigrants to work and to study is helping the US economy – it’s keeping a high supply of labour available for employers particularly in the areas of heavy demand for labour: healthcare, retail and leisure, also sectors of relatively low pay.

Net immigration is becoming vital to US capitalism. According to the Congressional Budget Office, the U.S. labour force will have grown by 5.2 million people by 2033, thanks mainly to net immigration and the economy is projected to grow by $7 trillion more over the next decade than it would have without new influx of immigrants.

But here is the rub. Americans now cite immigration as the country’s top problem, surpassing inflation, the economy and other issues with government. All the talk is of ‘illegals’ and Republican candidate for the 2024 election, former president Trump talks of deporting millions if re-elected as president – even though the ‘undocumented’ foreign-born population has been falling while legal immigrants have risen.

The usual (non-racist) argument against immigration is that wage levels of US workers will be reduced as native-born workers compete for jobs with foreign-born workers. But so far, all the evidence suggests not. A 2017 meta analysis of economic research on immigration conducted by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine suggests the impact of immigration on the overall U.S.-born wage “may be small and close to zero,” particularly when measured over a period of 10 years or more. There are much more significant hits to labour’s share of value-added in the economy, namely globalisation, weaker unions and a stagnant federal minimum wage. And there are other reasons why labour force participation may have declined long-term: automation and technology reducing the demand for low-skilled labour; and the shift away from manufacturing and toward service-oriented jobs, which often require higher educational attainment.

For now, contrary to the Trumpist talk, immigration for US capitalism is good news. That could change if the US economy drops into a recession where jobs become scarce.

March 10, 2024

Portugal: swinging right?

Portugal has a general election today, only two years from the last one. It’s taking place early because the Socialist prime minister Costa was forced to call it after a serious of corruption scandals concerning government ministers. Also a Lisbon court recently decided that a former Socialist prime minister should stand trial for corruption. Prosecutors allege that José Sócrates, prime minister between 2005-2011, pocketed around 34 million euros ($36.7 million) during his time in power from graft, fraud and money laundering.

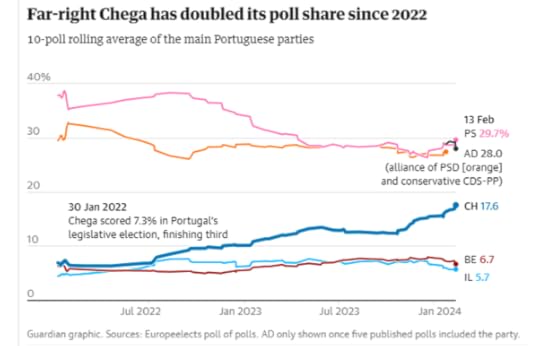

Just under 11m Portuguese are eligible to vote and the opinion polls suggest that the anti-immigrant, neo-fascist Chega (Enough!) could make the biggest gains and hold the balance of power in parliament between the currently governing centre-left Socialists and the centre-right Social Democrats.

The main opposition to the current government, the Social Democratic Party (PSD), has formed an alliance with the Popular Party (CDS-PP) and the Monarchist Popular Party (PPM), to form what they call the Democratic Alliance (AD) to be led by Luís Montenegro, the PSD leader. But the PSD too is tainted by corruption allegations. A graft investigation in Portugal’s Madeira Islands triggered the resignation of two prominent PSD officials.

The incumbent Socialists now have Pedro Santos as their leader. The party is offering a few minimal reforms: it intends to return 50% of VAT to those who buy hybrid or electric cars, create an entity that monitors the rental of properties and guarantee public bank financing for those who buy a house, up to the age of 40 – housing is a big issue.

The new AD centre-right alliance purports to defend ‘liberal conservatism’, ‘Christian democracy’ and ‘economic liberalism’. AD states that it wants to implement a maximum tax rate of 15% for people up to 35 years of age, as well 100% mortgages for first-time home buyers.

The anti-immigrant neo-fascist Chega led by Andre Ventura wants to defend ‘national values’ and to curb ‘Islamic fundmentalism’. Chega intends to equate the minimum pension to the National Minimum Wage and provide one year of paternity and maternity leave, shared between the child’s parents.

There are also various small left-wing parties that could poll about 5% between them.

The pandemic was a disaster for an already weak Portuguese economy. And since then the post-COVID economic recovery has been fuelled by deregulation and a series of schemes designed to lure foreign investment. This has distorted the housing market beyond all recognition in a place where the monthly minimum wage is €760 and where 50% of people earn less than €1,000 a month. The liberalisation of the rental market, the issuing of “golden visas” that confer residence permits in exchange for buying properties worth €500,000 or more, the introduction of tax-saving “non-habitual residency scheme” for foreigners, and, most recently, the creation of a digital nomad visa to allow well-off foreigners to work remotely and pay a tax rate of just 20% have all played a part. So too – perhaps most obviously – has the snapping up of flats to be converted into lucrative short-term rentals. Now there are 48,000 homes standing empty in Lisbon alone and 750,000 across Portugal as a whole. Portuguese citizens have been driven out of the housing market and there are few state schemes for rental housing. The reality is that successive governments have done nothing about the housing crisis, persistent low pay levels and unreliable public health services.

Average pay is just 1,300 euros (1,466 US dollars) a month. Among all OECD countries, Portugal has the sixth-lowest average salary but has seen the highest rise in house prices. In 2022, the take-home pay of an average single worker, after tax and benefits, was 71.9% of their gross wage, compared with the OECD average of 75.4%. An average married worker with two children in Portugal had a take-home pay, after tax and family benefits, of 84.6% of their gross wage, compared to 85.9% for the OECD average.

Inequality of incomes and wealth and levels of poverty in Portugal are among the highest in Europe. According to the World Inequality Database, the premier research body for measuring the inequality of incomes and wealth in a country, in Portugal in 2022, the top 10% of adults had 36% of total personal income in the country (before tax and benefits) while the bottom 50% of adults had to share just 19%. The very top 1% have 10% of all personal income. These ratios have worsened under successive governments in the 21st century.

It’s even more unequal when it comes to personal wealth ie property, savings and financial assets like shares and bonds. In 2022, the top 10% of adults had 60% of all personal wealth in Portugal, while the bottom 50% had only 3.6% between them! In other words, they own very little or nothing. The very top 1% had 25% of all personal wealth. And these ratios have worsened in the last 25 years under successive governments.

The Costa government came to power pledged to reverse the post 2008 slump austerity policies imposed by the Eurozone. But like other governments in southern Europe in the last decade, it made little progress on growth, productivity and investment, even if it avoided even worse austerity measures. Productivity has been flat for the last eight years.

Productivity level (index = 100)

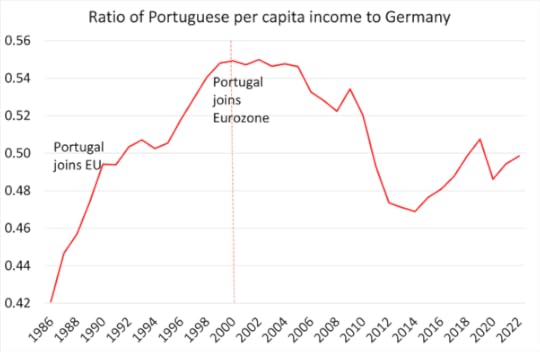

Portugal’s economy has been falling behind the rest of the EU since 2000. The European Union supposedly aimed to ‘level up’ the weaker capitalist economies with the richer core. The opening of trade and investment after Portugal became a member in 1986 appeared to work, as it did for other weaker EU countries. But the introduction of the euro changed all that. Whereas before the weaker EU countries could let their currencies depreciate against the deutschemark to try and remain competitive. That was no longer an option in the Eurozone. Without higher investment and productivity, the weaker capitalist members could not compete. Convergence turned into divergence. Portugal like other weaker members was reliant on FDI from Germany and France. External debt rose sharply and the Euro debt crisis in 2012 in the wake of the global financial crash pushed the country into penury and austerity. Portugal’s GDP per person remains less than half that of Germany.

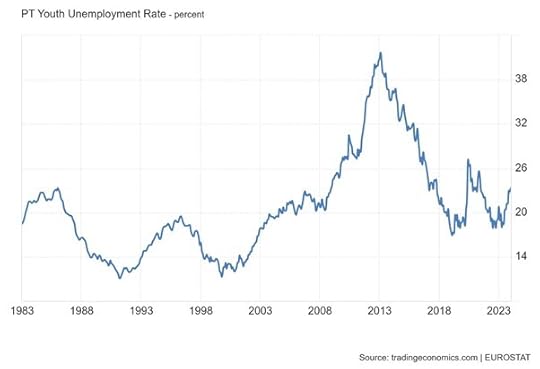

Meanwhile low wages and high unemployment have spurred emigration. Over the past decade – a period that includes governments run by both the Socialists and the ‘centre-right’ Social Democrats – some 20,000 Portuguese nurses have gone to work abroad, in an unprecedented drain of medical talent. The youth unemployment rate is still near 25%.

Youth unemployment rate (%)

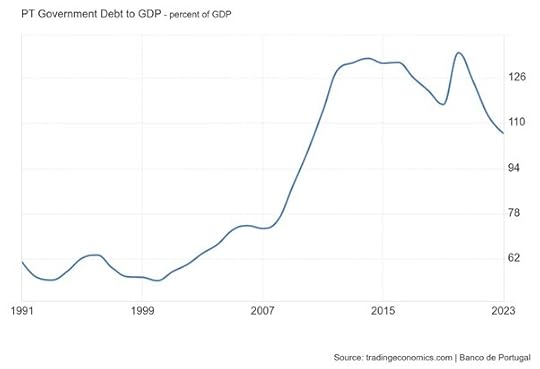

The main parties are putting all their hopes in the EU’s Recovery and Resilience Plan, which pools funds from the richer members to help out the weaker economies – the first time such a fiscal package has been employed across the EU. But the EU money has still not been disbursed. And it comes with strings: namely that the government is supposed to maintain a tight fiscal policy and keep budget deficits down and above all start to reduce its huge public debt ratio.

Public debt to GDP (%)

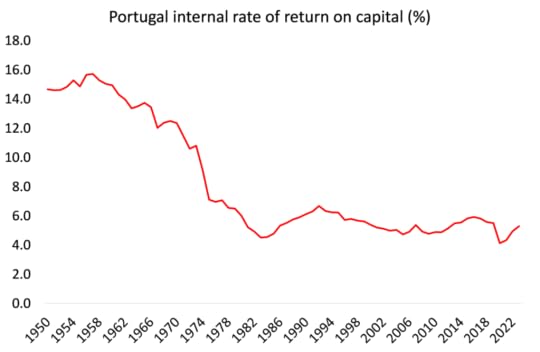

Even though the next government will be getting these funds from the EU to spend on infrastructure and services, it is likely to do little to get a very weak capitalist sector to invest, expand employment and raise wages. That’s because the profitability of capital in Portugal is miserable. It has been flat and low for 40 years. The EU has done nothing for Portuguese capital up to now.

Penn World Tables 10.0 IRR series

Whoever triumphs in today’s election has no real plan to change the dismal fortunes of Portuguese households. Desperation could see the rise of the neo-fascist right.

March 8, 2024

China’s next decade

The annual meeting of China’s National People’s Congress (NPC) is underway right now. The NPC is officially China’s highest deliberative body, ostensibly deciding economic and social policies each year. In reality, those policies have been drawn up by the Chinese Communist Party leaders in advance and then presented to the NPC to vote on (unanimously). Nevertheless, the NPC meeting offers the CP leaders an opportunity to spell out their policy answers to deal with the current economic and social problems of the country.

As is usual, it was the job of China’s premier to present this to the NPC. This year, there is a new premier, Li Qiang. But Li’s speech was very much in line with last year’s by the previous premier Li Keqiang. As last year, Li Qiang set a target for real GDP growth in 2024 of “around 5%” and said that China would be looking to “transform” China’s economic growth model.

The NPC will also be considering the annual budget. Defence spending is expected to rise by 7.2%, while public security spending is slated to rise by 1.4%, no doubt necessary given the military surrounding of China by the Western powers. Central government expenditures are expected to rise by 8.6% to reduce the burden somewhat on the highly indebted local governments. Other targets announced by Li include the creation of 12m new urban jobs and increasing consumer prices by about 3% (apparently to avoid deflation – see below). Li said these targets would “not be easy” but that “high quality development” remained the priority.

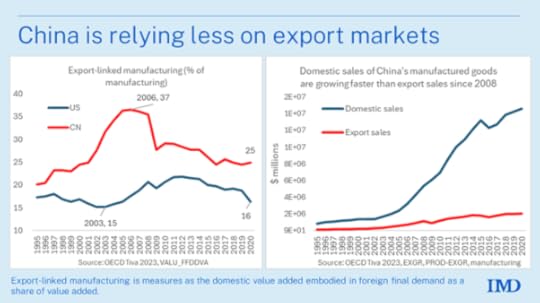

All this is pretty much in line with the targets set in China’s last five-year plan. The 14th plan agreed in 2021 was a comprehensive document covering all aspects of the Chinese economy in detail. But it had some key targets. In particular, China aimed at becoming a “moderately developed” economy by 2035 and to reduce inequality between urban and rural areas. The plan was based on the dual circulation model, where expanding manufacturing exports – the past key to China’s miracle growth -is combined with developing the domestic economy and reducing reliance on foreign imports and investment. The objective is that China can continue to grow and increase living standards despite attempts by Western governments to curb or strangle such growth.

Can China succeed in achieving both its growth target for this year and reach the longer-term objectives over the next ten years or so, taking nearly 1.4bn people up to living standards only enjoyed by a small group of nations in Europe, North America and East Asia?

If you were to read the Western press and their economists, you would conclude that the chances of China doing that are no better than a snowball surviving on being thrown into the sun. It is the almost unanimous cry of Western economists, particularly the ‘China experts’, that the China ‘miracle’ is over, and worse, China is heading into a debt deflation spiral that will mean growth targets will not be met at best, and more likely there will be a major slump. This is despite the fact that in 2023 China had an official growth rate of 5.2%, more than double that of the ‘booming’ US economy, and five times the rate of growth in the rest of top capitalist economies of the G7. (Don’t get me into the argument that China’s growth figure is fake and growth is much lower. Those that argue this have little supporting evidence.)

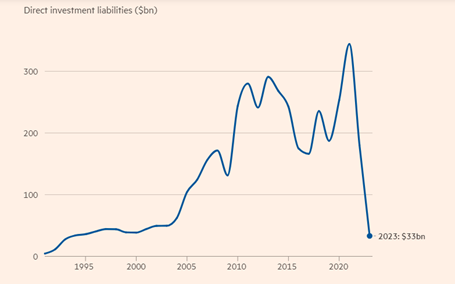

Ah, but you see, manufacturing is in recession (as measured by official surveys), consumption is weak (still below pre-pandemic levels) and foreign investment, seen as the life-blood for the Chinese economy has dried up.

And even worse, prices of goods and services are falling. Readers may be surprised to hear that Western economists, who spend much of their time demanding that inflation rates in their countries be reduced to no more than 2% a year after the post-COVID inflationary spiral of the last three years, see no merit in the lack of any rising prices (and therefore rising real wages) in the Chinese economy: it’s ‘inflation bad for the US; but no inflation bad for China’.

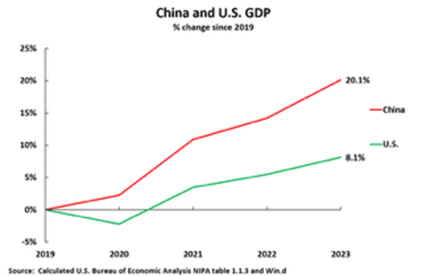

In a recent article, John Ross has shown that to achieve China’s Plan GDP target for 2025 ie a doubling GDP from 2021, it would require an average annual growth of 4.7% a year. So far, China is ahead of this goal with annual average growth in 2020-2023 of about 5%. Indeed, since the beginning of the pandemic, China’s economy has grown by 20.1% and the U.S. by 8.1%—that is China’s total GDP growth since the beginning of the pandemic has been two and half times greater than the US.

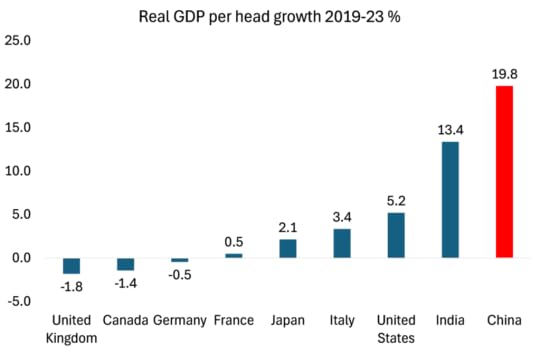

Yes, China’s annual growth rates have slowed from the breakneck pace of the 1990s onwards and the Chinese workforce is declining. But just look the increase in GDP per person that China has achieved compared to the G7 economies since 2019, some of which have even contracted (IMF data). The rise on per capita basis is even higher against the US (nearly four times).

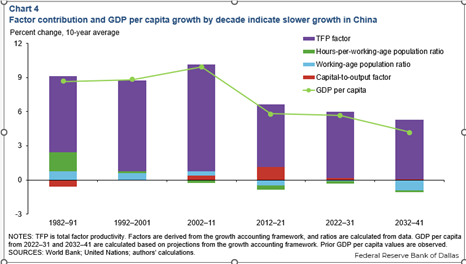

Yes, increasingly China cannot rely on an expansion of a cheap workforce from rural areas to achieve more output, but instead must raise the productivity of the existing labour force, especially through investment in technical innovation. And it is doing so. The Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas shows that ‘total factor productivity’ (which is a crude measure of innovation) is growing at 6% a year, while it has been falling in the US.

Despite this evidence, every year the Western ‘China’ experts (and even many in China itself) predict stagnation, given the huge debt levels in all sectors. China is going to stagnate like Japan has done in the last three decades. The only way to avoid ‘Japanification’, say these experts, is to ‘rebalance’ the economy from ‘over-investment’, ‘excessive savings’ and exports to a domestic consumer-led economy as in the West and reduce the state control of the economy so that the private sector can flourish.

This year on the occasion of the NPC, Martin Wolf, the Keynesian guru of the Financial Times, returned to this theme, echoing the arguments of other Keynesian China experts like Michael Pettis. According to Wolf, China’s growth will now slow to a trickle as in Japan because it overloaded with excessive debt and because it has not rebalanced the economy towards “the consumer”. China needs to get its consumption share up to Western levels or it will not be able to grow and so stay locked in a ‘middle income’ trap.

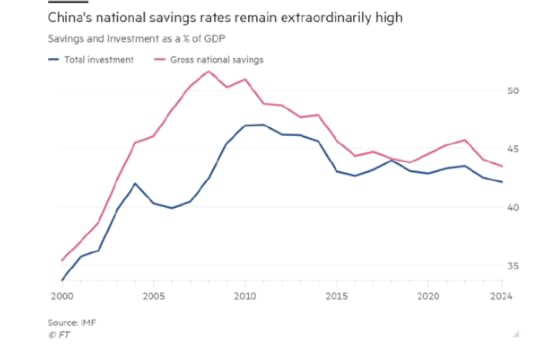

China generated 28 per cent of total global savings in 2023. This is only a little less than the 33 per cent share of the US and EU combined. This is all wrong, say Wolf and Pettis. What is needed is a shift from ‘excessive savings’ to consumption. There is over-investment in property and infrastructure, instead of handouts to households. China will only grow from here if consumption leads, not investment.

If you want to read more of this nonsense about consumption being the leader of growth, see my review of Pettis’ theories here.

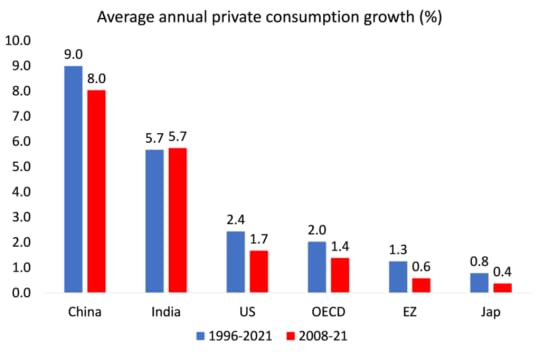

But how can anybody claim that the mature ‘consumer-led’ economies of the G7 have been successful in achieving steady and fast economic growth, or that real wages and consumption growth have been stronger there? Indeed, in the G7, consumption has failed to drive economic growth and wages have stagnated in real terms over the last ten years, while real wages in China have shot up. Moreover, these consumer-led economies have been hit by regular and recurring slumps in production that have lost trillions in output and income for their populations. The irony is that China’s consumption growth rate is way higher than in the G7 economies.

China has not had a contraction in national income in any year since 1976, while the consumer-led G7 economies have had slumps in 1980-2, 1991, 2001, 2008-9 and 2020. Much has been made of China’s ‘disastrous’ zero COVID policy. But apart from saving millions of lives, China still did not enter a slump in 2020, unlike all the G7 economies in 2020.