Michael Roberts's Blog, page 13

May 16, 2024

A new Spring for Labour?

This post was first published on May Day in the Lebanon journal, Project Zero, in Arabic. https://alsifr.org/new-era-labourer

May Day is traditionally celebrated as International Workers Day when people mobilise to support the strength and importance of labour in its perennial struggle against capital in society. Apart from participating in marches and demonstrations around the world, it is also an opportunity for us to consider how well the organisations of the working-class are faring in the 21st century.

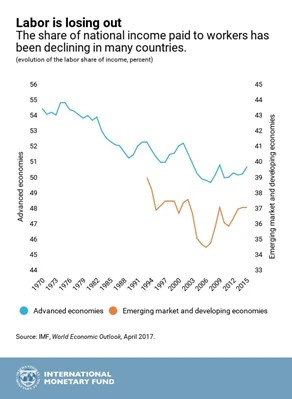

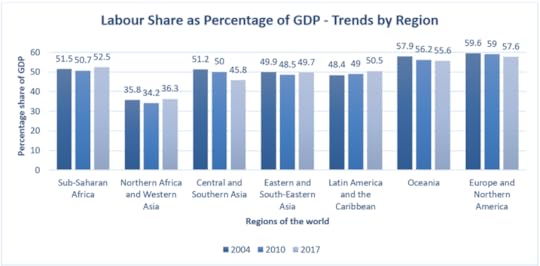

First, the bad news. From the 1980s, when the policies of neoliberalism were imposed by governments in all the major economies and often followed in the rest of the world, labour’s share of national income in most countries fell.

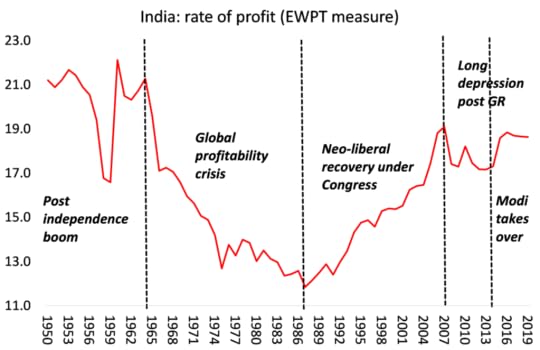

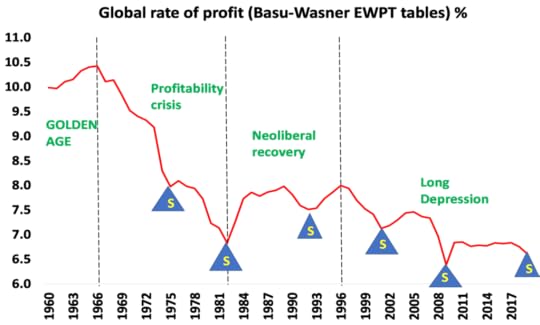

This was the result of several factors. In the 1960s and 1970s, the profitability of capital globally fell sharply. Capital could no longer afford to make concessions on wages, social benefits and public services. Now the order of the day was privatization, the weakening of trade unions and labour rights, cuts in taxes on the rich and the reduction of employment by transferring industry to the cheaper labour parts of the world.

There was increased exploitation of workers at work. And any increase in the productivity of labour through more intensity of work, the deregulation of workers’ rights and more automation went mostly into profits for the owners of enterprises. The fall in labour’s share was also powered by a series of slumps in capitalist production that weakened workers’ power in negotiations for wages and employment. Firms in the rich economies of North America, Europe and Japan shipped their manufacturing operations to the poor ‘Global South’ to increase profitability.

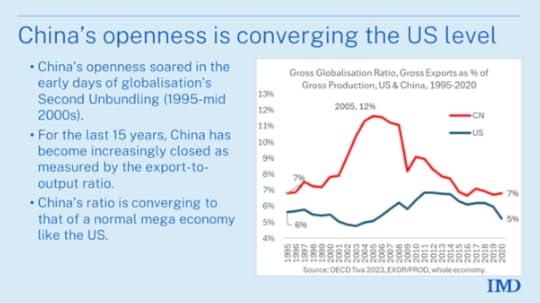

‘Globalisation’, as it was called, meant that wages and benefits in the major economies could not keep up with profits being made abroad; and in the poorer economies, workers’ wages were held down while foreign companies used the latest technology to boost production. Capitalist production in the major economies increasingly switched from traditional sectors like heavy engineering, steel, cars etc into commercial and financial sectors. Profitability rose globally and the share of income going to labour fell back.

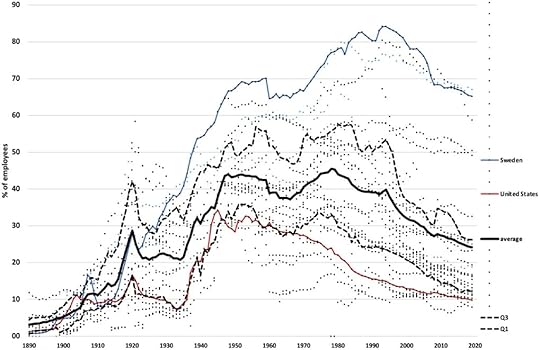

Another key factor in the decline of labour’s share of global income was the decline of trade union organisations. The number of union members as a proportion of employees has more than halved across developed economies from 33.9% in 1970 to just 13.2% in 2019, figures from the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) show.

If we look at the development of unionisation in 30 industrial countries over the last 130 years of capitalism, we can observe something like an inverted U-curve, with the peaks of maximum expansion of unionization between 1950 and 1980.

Unionization rates 1890–2019, 30 industrial countries

But if we look at the figures now, it seems that the days of trade unions as a force for labour are over. Large firms and manufacturing outlets, the basis for unionism in the past century, have closed or downsized by contracting out tasks and jobs. The growth of commercial services, with on average smaller establishments, has raised the challenge for unions to gain recognition as viable organizations.

Union density rates increase with firm size and this has been the case at least since the 1930s when, for example in the US, unions succeeded in organizing the big companies in steel, oil, cars, shipbuilding and related manufacturing. But the shift from manufacturing in the advanced capitalist economies to so-called ‘services’ has reduced the employment size of most companies. Across the OECD, 63% of all union members are employed in firms of 100+ employees, whereas only 7% work in small firms with 1–9 employees (data for 2015). Of the non-union members, 37% work in 100+ firms and 27% in small firms.

In 2019, 45% of all union members in the OECD worked in the public sector, a rise from 33% in 1980. But over those 40 years the share of public employment – public administration and security, social security, education, health and social assistance – in total employment barely increased, from 19% to 21%. So unionisation in the public sector cannot compensate for the loss of unions in the private sector.

In much of the ‘Global South’, most workers do not even have a permanent job. Globally, 58% of those employed are in what is called ‘informal employment’, amounting to around 2 billion workers in precarious jobs, lacking in any organized defence of their rights at work and their conditions by labour organisations. Increasingly, in many economies, young people experience a high degree of insecurity related to temporary contracts, unemployment and interrupted career paths. Unions appear to them as old and ineffective.

No surprise, then, that only about 2–3% of young workers under the age of 25 join a union. The average union density rate in the OECD of workers under the age of 25 has nearly halved in little more than a decade, from 11% in 2002 to 6% in 2014, continuing a process that began decades ago. In all countries, including high union density countries like Sweden and Denmark, there has been a significant fall in the share of young people joining a union.

Young people’s numbers in unions have correspondingly dwindled. The OECD average is 5.5%, down from an estimated 18% in 1990. Currently the age group of union members nearest to leaving the labour market, i.e. those over 55 years, is four times larger than the 15–24 age group entering the unions. So unions face an uphill battle to replace members who leave with workers who join.

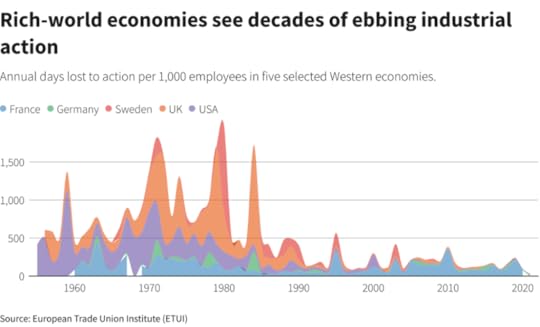

As a result of the weakening of collective labour organizations, workers’ ability to defend their rights at work and gain better wages and conditions has also fallen back. Industrial dispute levels have dropped sharply. Prior to the pandemic slump of 2020, annual days lost due to industrial disputes in the major ‘rich’ economies were near record lows.

In many parts of the Global South, trade unions and collective organisations are banned. According to the International Trade Union Confederation (ITUC), the Middle East is the worst region for suppressing trade unions. There are no rights in workplaces, independent unions are dismantled and trade union leaders locked up for leading strikes. The kafala system remains in place in several Gulf countries and migrant workers, who represented the overwhelming majority of the working population in the region, remained exposed to severe human rights abuses. In Tunisia, unions feared for democracy and civil liberties as President Kais Saied further consolidated his autocratic powers, while in Algeria and Egypt, independent trade unions still struggled to obtain their registration from hostile authorities and were therefore unable to operate properly. In Lebanon, it was common for employers to interfere in social elections, including by deleting names from the lists of candidates.

That’s all the bad news. But there is also good news coming out of the bad. Millions died unnecessarily in the COVID pandemic and millions more lost their livelihoods in the ensuing slump and the inflationary spiral afterwards. But the pandemic has also changed the balance of forces between labour and capital.

The Black Death and plagues of the 14th century so reduced the population of Europe that labour became so scarce that feudal landlords were forced to make concessions to their serfs, allowing them to earn wages, work less hours for the lord and even gain freedom to become independent farmers. Out of that terrible misery came a period of improved livelihoods.

It seems that a similar development is taking place in this post-pandemic decade of the 21st century. The years of fast-expanding labour markets globally, as in China and eastern Europe, that opened up to capital from the Global North, have come to an end as populations age and shrink. This demographic shift is resulting in a shift in the balance of power between labour and capital.

Amid tight labour markets and a rising cost of living, there has been a resurgence in labour militancy and the conditions for renewed union growth are much more favourable. Unions globally have become increasingly active in the last 12 months in either threatening or carrying out industrial action. For the first time in some 40 years, trade unions are spreading to new industries and sectors in the advanced economies and even into ‘informal’ employment world of the Global South.

In the US, workers have organised and taken to the picket lines in increased numbers to demand better pay and working conditions. Teachers, journalists and baristas are among tens of thousands of workers who have gone on strike in the last year. Indeed, it took an act in the US Congress to prevent 115,000 railroad employees from walking out as well. Workers at Starbucks, Amazon, Apple and dozens of other companies also filed over 2,000 petitions to form unions during the year – the most since 2015. Workers won 76% of the 1,363 elections that were held. There were 33 major work stoppages that began in 2023, the largest number this century.

Elsewhere in the world, we can see something similar. Last March 2023, in Sri Lanka, workers from 40 trade unions, representing sectors including health, energy, financial services and port operations, went on strike over the government’s spending plans in spite of the threat of employees losing their jobs by defying the presidential proclamation.

The South African National Education, Health and Allied Workers Union (NEHAWU) went on strike over pay despite a court order banning industrial action. In India, proposed changes to the country’s labour codes – including clauses requiring 14 days’ notice for strike action brought about strike action.

And even in the Middle East, there have been some successes. Workers at Egypt’s largest textile factory in Mahalla won a major victory for tens of thousands employed across Egypt’s state-owned enterprises by forcing the government to agree to raise the minimum wage to 6000 Egyptian pounds after thousands joined a strike which shut down the mill for nearly a week.

In the past, organized labour was driven by large, central trade unions that coordinated unionization drives, dictated member demands and distributed benefits. By contrast, this new wave of labour organizations are small grassroots unions in untouched sectors, often specific to one company like the Amazon Labor Union and Starbucks Workers United. Moreover, American support for unions has been rising. An August 2023 Gallup poll suggested that two out of three Americans supported unions.

And the battle to defend jobs and conditions against the impact of the new AI technologies has started. An example of this is the recently signed agreement by the Writers Guild of America in Hollywood around concerns of AI adoption by employers in the entertainment industry.

Union revitalization will happen when unions make themselves relevant for both highly-skilled employees and solo self-employed workers (often working from home) and expand their presence among the growing army of mostly young platform workers, migrants and employees with part-time and fixed-term contracts. It will require new methods of reconnecting with young people. More unions now experiment with interactive websites and social media and with a model of membership or participation that is easy and cheap, with low entry or exit costs.

So, in May 2024, we could be at the start of a paradigm shift in labour organization. But trade unions are not enough to change the balance of power between labour and capital. That also requires political action. In Europe, unions were formed by socialist parties in the late 19th century; in the UK, trade unions formed the Labour Party to represent workers in the political arena. The struggle in the workplace can only succeed in making gains when combined with the political struggle to change the whole system of power.

In the 19th century, the struggle for the eight-hour day was a key feature of the May Day marches in the US and Europe. It was only eventually achieved by a combination of union action and political legislation in the 20th century. In the 21st century, the struggle is going to be over AI automation which threatens up to 300m jobs globally in the next decade. The response of labour must be for a four-day week, social support and retraining for those unemployed by the new technology. That will require a combination of new strong unions and political parties dedicated to the struggle of labour over capital.

May 13, 2024

Joseph Stiglitz and ‘progressive capitalism’

The liberal leftist economist and Nobel (Riksbank) prize winner Joseph Stiglitz has another book out to proclaim the benefits of what he calls ‘progressive capitalism’. The Road to Freedom is a play on the title of Friedrich Hayek’s infamous book, The Road to Serfdom, published in 1944, which claimed that government intervention into the ‘freedom of markets’ would cause shortages and misallocations of resources and eventually to the end of democracy and freedom in a dictatorship a la Stalinist Soviet Union. John Maynard Keynes expressed his agreement with Hayek after reading his book. He wrote to Hayek that: “morally and philosophically I find myself in agreement with virtually the whole of it; and not only in agreement with it, but in a deeply moved agreement.”

But Stiglitz certainly does not. For him, Hayek’s claim that ‘free markets’ mean freedom for the individual really means ‘freedom for the wolves and death to the sheep’ (Isaiah Berlin). Free markets are designed to make profits not to meet the social needs of the many. “Externalities are everywhere,” Stiglitz writes. “The biggest and most famous negative externalities are air pollution and climate change, which derive from the freedom of businesses and individuals to take actions that create harmful emissions.” The argument for restricting this freedom, Stiglitz points out, is that doing so will “expand the freedom of people in later generations to exist on a livable planet without having to spend a huge amount of money to adapt to massive changes in climate and sea levels.”

For Stiglitz, the enemy of human freedom is not capitalism as such, but ‘neoliberalism’ which has bred soaring inequality, environmental degradation, the entrenchment of corporate monopolies, the 2008 financial crisis, and the rise of dangerous right-wing populists like Donald Trump. These baleful outcomes weren’t ordained by any laws of nature or laws of economics, he says. Rather, they were “a matter of choice, a result of the rules and regulations that had governed our economy. They had been shaped by decades of neoliberalism, and it was neoliberalism that was at fault.”

Stiglitz has argued before in previous books that it is not capitalism that is at fault but the decisions of governments and their corporate backers to ‘change the rules of the game’ that had existed in the post-war period of managed capitalism. The rules were changed to deregulate; to privatise; to crush labour unions etc. But Stiglitz never explains why the ruling elite felt it necessary to change the rules of the game. What happened to swing the post-war rules into the neoliberal ones?

Anyway, Stigliz reiterates his call for the creation of a “progressive capitalism”. Under the rules of this form of capitalism, the government would employ a full range of tax, spending, and regulatory policies to reduce inequality, rein in corporate power,and develop the sorts of capital for social needs not profits like ‘human capital’ (education), ‘social capital’ (cooperatives), and ‘natural capital’ (environmental resources).

Stiglitz does not want to get rid of capitalism but to regulate it, so it works for the many (sheep) over the few (wolves). “We need environmental regulations, traffic regulations, zoning regulation, financial regulations, we need regulations in all the constituents of our economy,” he writes. But Stiglitz is either naïve or applying sophistry here. The history of regulation is a history of failure in controlling capitalism or making banks and corporations apply policies and investment in the interests of people over profit.

How can anyone not see that, after the global financial crash of 2008, or the subsequent financial scandals galore; or the failure to stop or regulate fossil fuel production and finance? Regulation has not stopped regular and recurring crises of production under capitalism, whether in the imagined ‘progressive era’ of 1945-75 or in the neoliberal era since. Stiglitz has nothing to say on this.

Indeed, he almost recognizes that his policy proposals of taxing the rich, regulating finance and the environment and increasing public spending to achieve progressive capitalism are not likely to be adopted by governments and big business. But when asked that, maybe, the only real alternative to achieve human freedom is a revolutionary transformation of the economy and society, he replied at a LSE presentation of his book, that revolutions are violent and risky and so should be avoided in favour of gradualist change.

His answer reminds me of John Mann’s comment in his excellent book, In the Long Run We are all Dead, “the Left wants democracy without populism, it wants transformational politics without the risks of transformation; it wants revolution without revolutionaries”. (p21). Stiglitz really echoes Keynes who once said, “For the most part, I think that Capitalism, wisely managed, can probably be made more efficient for attaining economic ends than any alternative system yet in sight, but that in itself it is in many ways extremely objectionable. Our problem is to work out a social organisation which shall be as efficient as possible without offending our notions of a satisfactory way of life.”

How would regulation and more equality deal with the impending disaster that is global warming as capitalism accumulates rapaciously without any regard for the planet’s resources and viability? Programmes of redistribution will do little for this. And if an economy is made more equal, would it stop future slumps under capitalism or future Great Recessions? More equal economies in the past did not avoid these slumps. Progressive capitalism is an oxymoron in the 21st century. And even Stiglitz doubts that it is possible to achieve.

May 8, 2024

Vulture capitalism

Grace Blakeley is a media star of the radical left-wing of the British labour movement. She is a columnist for the left-wing journal, Tribune, and a regular panellist on political debates in broadcasting – often the only spokesperson on the left advocating socialist alternatives.

Her profile and popularity took her last book, Stolen, straight into the top 50 of all books on Amazon. Her new book, entitled Vulture Capitalism: Corporate Crimes, Backdoor Bailouts and the Death of Freedom (Bloomsbury 2024) has achieved even greater popularity, ‘long listed’ for the women’s non-fiction book of the year, and even making Glamour magazine as a book essential for young fashionistas to read.

Blakeley’s main theme in Vulture Capitalism is to debunk the longstanding concept of mainstream neo-classical economics that capitalism is a system of ‘free markets’ and competition. If capitalism ever did have ‘free markets’ and competition among companies in the struggle to obtain profits created by labour (and Blakeley doubts that it ever did), then it certainly does not now. Capitalism now, she argues, is really a planned economy, controlled by big monopolies and backed by the state. The monopolies plan strategy and investment in conjunction with governments; and small companies and workers must obey: “actually existing capitalist economies are hybrid systems, based on a careful balance between markets and planning. This is not a glitch resulting from the incomplete implementation of capitalism, or its corruption by an evil, all-powerful elite. It is simply the way capitalism works.” I take this to mean that the big monopolies, finance and the state now plan the world and avoid the impact of the ups and downs of markets (free or otherwise), which are now basically irrelevant.

As Blakeley explains, market forces do not operate within companies. Ronald Coase was the mainstream economist who first outlined how firms operate on internal planning. There are no markets or contracts between sections or workers and management within firms. Management plans and workers apply them. But Blakeley argues that this planning mechanism now applies to relations between firms, or at least large ‘monopoly’ firms. “Large firms are able, to a significant extent, to ignore the pressure exerted by the market and instead act to shape market conditions themselves.”

If anything goes wrong and there is a crisis, the big monopolies and the state work together to resolve, with little impact on themselves. “within actually existing capitalism—a hybrid of markets and central planning—the largest and most powerful institutions in the public and private sectors can work together to save their own skin. Rather than bearing the consequences of the crises they have created, these actors shift the costs of their greed to those with the least power—working people, particularly those in the poorest parts of the world….. And the monopolies combine with the state to resolve such crises. “Every recent crisis—from the financial crisis to the pandemic, to the cost-of-living crisis—has involved a key role for the state in solving capital’s collective action problems. And even though capitalists have often wailed about the pain inflicted on them at the time, they have always come out on top.”

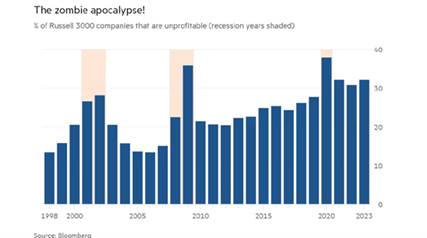

Blakeley argues that crises in capitalism are no longer resolved by what Joseph Schumpeter (and Marx for that matter) called ‘creative destruction’ . Crises in capitalism ie slumps that lead to the liquidation of companies; mass unemployment and financial crashes, have been increasingly overcome through ‘planning’ by the big monopolies and the state. “The evidence suggests that Schumpeter’s temporary monopolies are becoming increasingly permanent. So, not only are relationships within the firm based on authority rather than market exchange, but the authority of the boss is also relatively unconstrained by the discipline of the market. Bosses are increasingly able to act as powerful planners within their domain. And in doing so they are able to exercise significant power over society as a whole.”

For me, two doubts about this thesis arise here. First, while there may be no markets or competition within firms, are we really saying that there is no competition among firms over the share of profits exploited from the labour of working people; that markets (free or otherwise) exert no influence on capitalist accumulation?

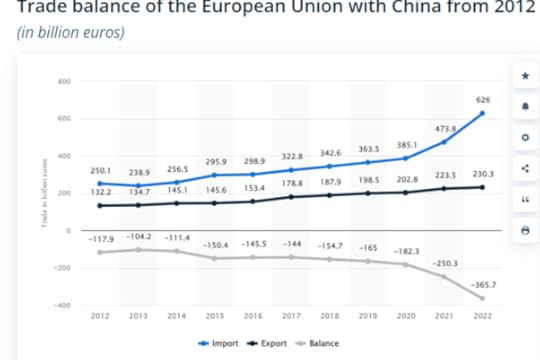

For a start, competition at an international level among multi-national companies is intense: cartels do not operate with any conviction in international trade and investment. The trade and investment war between the US and China is not a good example of global planning. Moreover, the drive for profits in capitalist production leads to an incessant search by companies for technological advantage over rivals. Companies that appear to have a ‘monopoly’ in a particular sector or market are always under threat of losing that hegemony – and that applies to the largest companies too. Indeed, technological competition has never been greater.

This applies to competition within the nation state as well as internationally. In 2020, the average lifespan of a company on Standard and Poor’s 500 Index was just over 21 years, compared with 32 years in 1965. There is a clear long-term trend of declining corporate longevity with regards to companies on the S&P 500 Index, with this expected to fall even further throughout the 2020s. Blakeley supports her argument with evidence of the growth of market power and monopoly concentration provided by recent studies. However, these studies are not convincing, in my view.

Second, if monopolies and the state can now plan and avoid the vicissitudes of the market, why are there still major crises in capitalist production at regular and recurring intervals. In the 21st century we have had the two largest crises in the history of capitalism in 2008 and 2020. Did capitalism avoid these through ‘planning’?

Blakeley dispenses with the ‘out of date’ Marxist explanation of crises that Marx argued for, between the profitability of capital and productivity of labour that leads to regular and recurring crises of investment and production. For Blakeley, capitalism can actually avoid or at least resolve such crises by ‘planning’ and by getting handouts from the state. Monopolies can avoid ‘creative destruction’ and can continue to motor on at the expense of small businesses and the rest of us.

For Blakeley, crises do occur but they are no longer the “natural results of either unrestrained free markets or greedy unionized workers” or it seems from any inherent economic contradiction in capitalist accumulation. Now crises result “from political choices made by states and corporations in response to shifts in power and wealth then underway in the world economy. Naturally, these choices tended to consolidate the status quo and benefit the powerful.” But if crises are now the result of bad political choices by those in power, then better decisions could work to keep capitalism not only free of markets but also free of crises. ‘Planned’ capitalism can work if there are no inherent faultlines in capitalist production any longer. Blakeley has basically resurrected the theory of ‘state monopoly capitalism’, an old Soviet/Stalinist/Maoist term which argues that crises in ‘competitive’ capitalism have been ended at the expense of stagnation. Democracy has been replaced by monopoly power (assuming that there was any real economic democracy ever).

Blakeley instructs us to realise that, under capitalism, workers are considered as just bees, doing the bidding of the Queen and her drones. But “what differentiates us from other animals is our capacity to reimagine and re-create the world around us. As Marx wrote, human beings are architects, not bees.” Apparently, there was a time when workers did have a say in planning. I quote Blakeley from a recent interview on her book: “So planning continued as it had before, throughout the history of capitalism, it’s just that rather than workers, bosses and politicians, the workers were pushed out and it was just bosses and politicians that ended up planning.” Really? Workers used to have a say in planning economies in some ‘pre-monopoly age’ and were not always bees? If Blakeley means that trade union used to be stronger before the neoliberal period and so could exercise some influence in monopoly planning or that German workers councils could do the same, those of us who lived through the 1960s and 1970s know that not to be the case.

Blakeley’s answer to this ‘death of freedom’ for workers is not planning to replace markets as we old socialists used to argue, but workers’ own local enterprises. And Blakeley presents us with a package of examples of when workers have developed their own cooperatives and self-managed activities that demonstrate that it is possible to organize society without markets, without the state (and without planning?).

Blakeley’s best example is the Lucas Plan of the 1970s, which saw workers develop proposals to transform a multinational arms manufacturer into a worker-owned social enterprise. “The Lucas Plan was an extraordinarily ambitious document that challenged the foundations of capitalism. In place of an institution designed to generate profits via the domination of labor by capital, the workers at Lucas Aerospace had developed an entirely new model for the firm—one based on the democratic production of socially useful commodities. It was almost as if the workers had never needed managing at all, as though they were creative architects rather than obedient bees.”

And then there was the ‘participatory budgeting movement’ in Brazil, “in which citizens have taken control of government spending with astonishing results”. Other examples are taken from Argentina and Chile. Blakeley concludes “the evidence is clear: when you give people real power, they use it to build socialism.” But the evidence is also clear that all these imaginative projects by workers at the local level have either eventually collapsed; or have been consumed by capital (Lucas); or continue without having any wider effect on the capitalist control of the economy – has ‘participatory budgeting’ in Brazil led to a socialist Brazil? Have the projects in Argentina stopped the horrendous series of economic crises in that country?

Blakeley is aware of this of course: “without reforms to the structure of capitalist societies, such innovations are bound to remain small. Unless we socialize and democratize the ownership of society’s most important resources—unless we dissolve the class divide between capital and labor itself—there can be no true democracy.”

Blakeley rightly calls for an end to trade union restrictions, a four-day working week and universal basic services. “A far better proposal would be to decommodify everything people need to survive by providing a program of universal basic services, whereby all essential services like health care, education (including higher education), social care, and even food, housing, and transport are provided for free or at subsidized prices. And ensuring that these services are governed democratically would also help build social solidarity at the local level—something that a UBI would be unlikely to achieve.” Indeed. But how can any of these necessary measures in the interests of working people be achieved without public ownership of the means of production? How can we decommodify essential services without public ownership of the energy companies, publicly owned health and education services, publicly owned transport and communications or of basic food production and distribution?

Here, Blakeley’s proposals seem very thin. Citing a programme for the UK, she wants ‘retail banks’ nationalised; and she wants to democratise the central bank. That’s finance. But I see no demands for nationalisation of the big monopolies that Blakeley says controls with impunity our society now. What about the big fossil fuel companies; big pharma (that profited from COVID) or the big food companies (that profited from the inflationary spiral)? What about the mega social media and tech companies that suck up trillions in profits? Should they not be publicly owned?

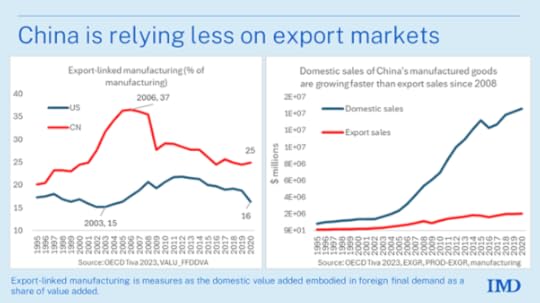

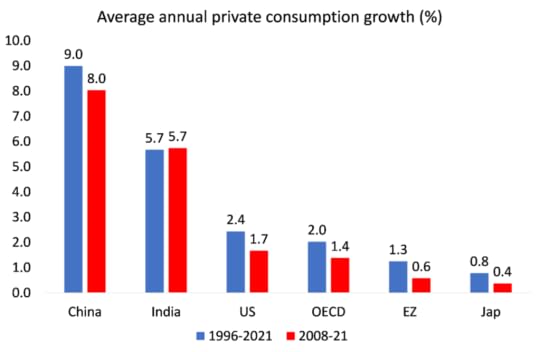

When it comes to the world economy and the Global South, Blakeley refers to what she calls the “developmentalist approach’ adopted by some countries where it is assumed “that the state can act as an autonomous force within society”. For her, China is an example where “the result has been the construction of an astonishingly successful model of development”. But this success, says Blakeley, was only achieved by the exploitation of Chinese workers just as happens in the rich world: “it was precisely the ability of Chinese planners to promote economic growth while suppressing the demands of workers that underpinned the Chinese “miracle.” So, for Blakeley, China is no different from the ‘developmentalist’ economies of Japan or Korea.

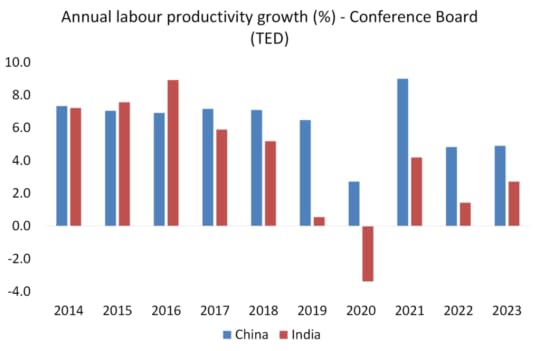

But is that right? In the West, ‘state monopoly planning’ has not avoided successive economic crises and delivers ever slower economic growth and investment, as in Japan and the rest of the G7. But ‘state monopoly planning’ in China has led to unprecedented growth without any slumps as experienced in the West or in other ‘emerging economies’ like India or Brazil. And contrary to Blakeley’s assertion, China has achieved the fastest growth in real wages among all the major economies. We can only explain this different result because there is a difference: China’s economy is based on state-led investment planning that dominates not capitalist firms and the market, unlike in the West.

And take the issue of climate change and global warming. Surely, it is abundantly clear that markets and pricing solutions cannot deal with the climate crisis. What is needed is global planning based on public ownership of the fossil fuel industry and public investment on a grand scale by states in cooperation. It cannot be solved by local workers enterprises.

Blakeley says that “expanding” public ownership of firms—whether at a local or national level—is “another key element in the democratization of the economy, because it challenges capital’s power over investment”. But ending capitalist power (monopolistic or not) through public ownership is not just ‘another key element’ but the key element. Without it, democratic planning and control by workers of their economy and society is impossible. Blakeley puts ‘democracy’ before public ownership and planning – the cart before the horse. To travel towards socialism, we need both the horse and the cart together.

Capitalism has not overcome international crises through state monopoly planning. Crises continue to occur at regular intervals, caused by the contradiction between the striving for more profit and the increasing difficulty of realizing that profit. Crises are still inherent to the capitalist accumulation process and not the result of ‘bad choices’ made by politicians doing the bidding of monopolies. Only the ending of private capital and the law of value through public ownership and planning can stop such crises.

Blakeley’s analysis of modern capitalism as one of ‘planned capitalism’ is confusing. Has the capitalist leopard that emerged as the globally dominant mode of production in the 19th century really changed its spots? Blakeley’s previous book, Stolen, had the subtitle “how to save the world from financialisation.” – note, not capitalism as such but finance capital.

And the title of this new book is also confusing. Our enemy this time is not ‘financialisation’ but ‘vulture capitalism’. But what is Vulture Capitalism? I searched through the book to find out. There is no explanation of this term in the book apart from referring briefly to vulture hedge funds pressuring poor country governments for debt repayments. The term vulture capitalism appears to have no relevance to the context of Blakeley’s theme in the book. I assume that it was just a smart marketing title dreamed up by the publishers. It’s worked in selling the book; but it does not work in explaining anything about capitalism in the 21st century.

May 5, 2024

Inflation and interest rates: the US experience

Once again the US Federal Reserve is in a quandary. Does it cut its policy interest rate soon in order to relieve pressure on debt servicing costs for consumers and businesses and perhaps avoid a stagflationary economy (ie low or no growth alongside higher inflation); or does it hold its current interest rate for borrowing in order to make sure inflation falls towards its target of 2% a year?

That’s what mainstream economists and investors in financial assets want an answer to. But it’s not really the important issue. What the Fed’s current quandary really shows is that yet again ‘monetary policy’ (ie central banks adjusting interest rates and money supply) has little effect on controlling inflation in the prices of goods and services that households and businesses must pay.

Central bankers and mainstream economists continue to argue that monetary policy does make a difference to inflation rates. But the evidence is to the contrary. Monetary policy supposedly manages ‘aggregate demand’ in an economy by making it more or less expensive to borrow to spend (whether as consumption or investment). But the experience of the recent inflationary spike since the end of the pandemic slump in 2020 is clear. Inflation went up because of weakened and blocked supply chains and the slow recovery in manufacturing production, not because of ‘excessive demand’ caused by either a government spending binge or ‘excessive’ wage rises or both. And inflation started to subside as soon as the energy and food shortages and prices ebbed, global supply chain blockages were reduced and production began to pick up.

I won’t go over the past evidence that inflation was supply-driven not demand-led, which is overwhelming. But this meant that central bank monetary policy could take little credit for reducing inflation. And here is the rub. Inflation rates are beginning to creep back up again, particularly in the US. US core inflation (which actually excludes food and energy prices) is now rising at over 4% a year on a 3m rolling average.

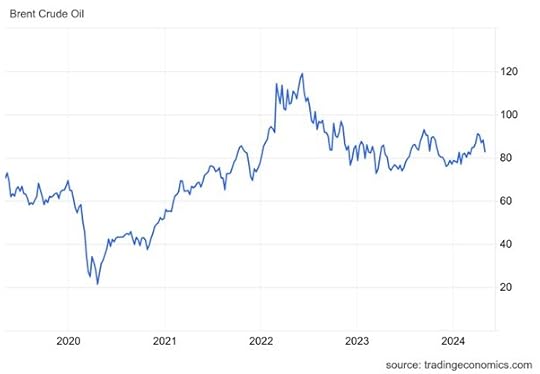

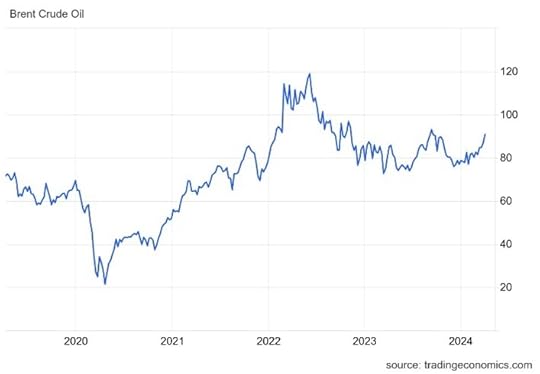

And the reasons are two-fold. First, food and energy prices have started to rise again. Oil prices have picked up as the Houthis attack shipping in the Red Sea and Israel extends the war in Gaza towards Iran.

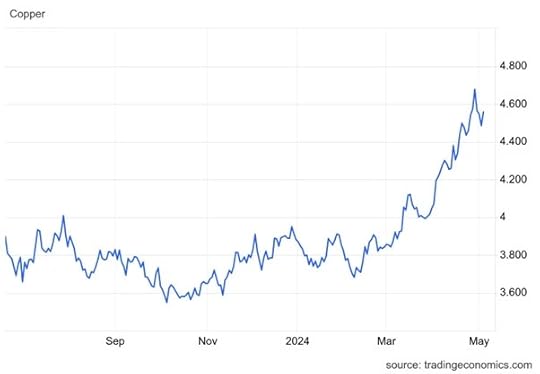

And a key raw material for industry, copper, is in short supply and now has a record price.

The Fed is in a quandary and mainstream economists have been forced again to reconsider the efficacy of monetarism, the theory that inflation is caused by excessive money supply growth over output. Central banks have been squeezing money supply growth supposedly to reduce inflation. But mainstream voices are showing uncertainty.

The FT published an article this week headed: The limits of what high interest rates can now achieve, commenting that “We need to be realistic about what monetary policy can and cannot do”. The article admits that “the effectiveness of monetary policy also depends on the structural economic drivers around it. After all, the era of benign inflation before the financial crisis was bolstered by elastic production and energy supplies. Looking ahead, using rates with unreliable lags to influence demand is a recipe for volatility, as supply shocks from regionalisation, geopolitics and less supportive demographics continue — unless there are offsetting productivity gains.” The article concludes that “Fiscal and supply-side policy must get greater emphasis in the price stability debate. After all, a faulty faucet is even more useless if the plumbing has gone awry.”

Nevertheless, the article continued to claim that monetary policy by the Fed and other central banks had helped to get inflation down. The article cited various papers for this claim, from the Bank for International Settlements and the Bank of England. But when you go to those sources, the evidence again is to the contrary. Take the BoE paper quoted: it concludes that “UK inflation in 2021 is explained by shortages and energy price shocks, and in 2022 and 2023 also by food price shocks and labour market tightness. Inflation expectations have been more well-anchored than predicted by the model. Conditional projections suggest UK inflation will fall sharply in 2023 from disinflationary energy and food price effects, but the decline will slow markedly thereafter.” So not much to do with ‘excessive demand’

Even at the home of monetarism, the Bank for International Settlements, is less than convincing in claiming that inflation was due to excessive money supply or even excessive demand. The BIS paper focuses its attention not on the initial causes of the inflationary spike but on the likelihood that inflation will be ‘sticky’ and not come down much because of the risk workers taking advantage of ‘tight’ labour markets to boost wages. The BIS is more worried about the hit to the profitability of companies than the fact that workers’ wages are still trying to catch up with a more than 20% rise in average prices since the end of the pandemic. “in tighter markets, there is a greater likelihood that bargaining power will shift in favour of workers and pass-through between wages and prices will gain strength.” Oh dear. But even the BIS admits that “adverse demographic trends and pandemic-related preference shifts on the supply side, can go a long way in explaining these dynamics.”

The final mainstream argument for inflation is inflation expectations. You see, households and even companies expect inflation to accelerate so households buy more and companies hike prices more, achieving even higher inflation. The expectations theory is no theory at all. It can only operate if inflation is already rising and so cannot explain the initial spike at all. Expectations theory has been debunked as an explanation for rising inflation. Now with falling inflation, the evidence for this ‘theory’ remains weak.

Allianz Research has disaggregated the 9 percentage point drop in America’s quarterly annualised inflation since the second quarter of 2022 using regression analysis. It found 5.5pp of the drop was driven by supply-chain snags simply unwinding. So that’s some 60% of the decline. But AR reckons that 2.7pp of the 9% fall “was due to the Federal Reserve’s signalling, which helped to re-anchor inflation expectations.” I leave you to believe what you make of the idea of ‘signalling’. Another 2.2pp came from the impact of higher rates squeezing demand, which was needed to counteract the inflationary impact of supportive fiscal policy and labour shortages. Even if you accept this analysis, it means that 60-80% of the decline in US inflation since the middle of 2022 was due to supply-side factors.

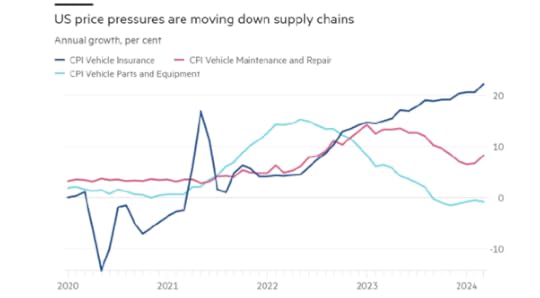

And that brings us to the ‘stickiness’ of inflation. Which components of the inflation index have not fallen despite central bank rate hikes? The answer is housing costs and motor car insurance, which have risen sharply. As the FT article admits: “Both are partly a product of pandemic supply shocks — reduced construction and a shortage of vehicle parts — that are still percolating through the supply chain. Indeed, dearer car insurance now is a product of past cost pressures in vehicles. Demand is not the central problem; there is little high rates can do.”

The FT article concludes that “Either way, monetary policy is a catchall tool. It cannot control demand in a quick, linear or targeted manner. Other measures need to pick up the slack. Estimates suggest supply factors — which rates have little influence over — are now contributing more to US core inflation than demand.” Well, actually throughout this inflation rise and fall, it has been supply that has been the main driver.

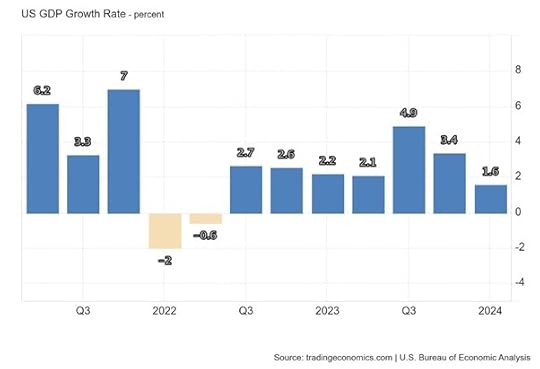

Where to now? The risk now is that the US economy could slow down towards stagnation in output while inflation stays ‘sticky’ because of a new rise in commodity prices. The US economy ended last year growing in real terms (ie after accounting for inflation) at an annual rate of 3.4%. This was greeted with euphoria by the mainstream and the financial media. “The U.S. economy is performing very well…We’re truly the envy of the world.” said one EconForecaster, James Smith. But then in the first quarter of 2024, that real GDP growth annual rate slowed to 1.6%, the slowest rate since the first half of 2022.

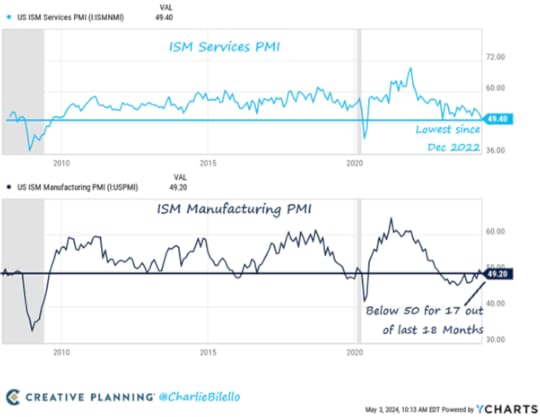

Moreover, the latest economic activity surveys, called PMIs, for the US make dismal reading. Any level below 50 indicates a contraction. In April, both the US manufacturing and services sector PMIs were below 50 for the first time together.

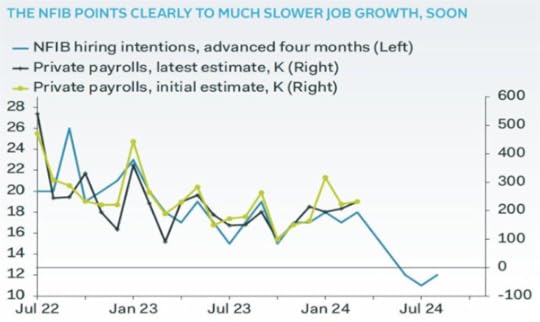

Also, the jobs market is beginning to look frailer. Sure, the official US unemployment rate is still below 4% (3.9%), but job hiring by US companies is dropping off, particularly among small firms as the National Federation of Independent Businesses survey of hiring intentions shows. And the NFIB survey seems a good forward indicator of jobs growth.

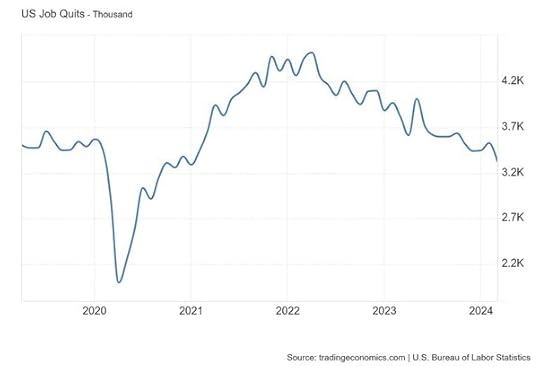

And employees are now more reluctant to switch jobs, in case they do not get another.

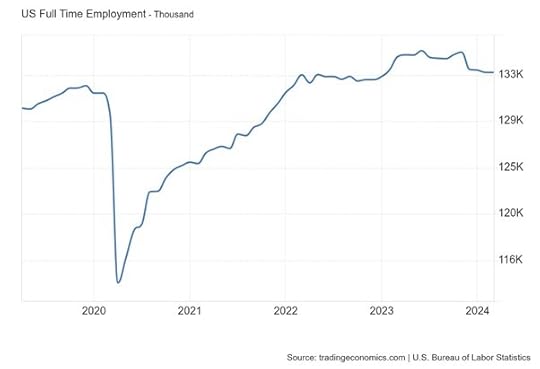

Indeed, over the past two years, most new jobs have been part time.

While full-time employment (that always pays better and with better conditions) has stagnated.

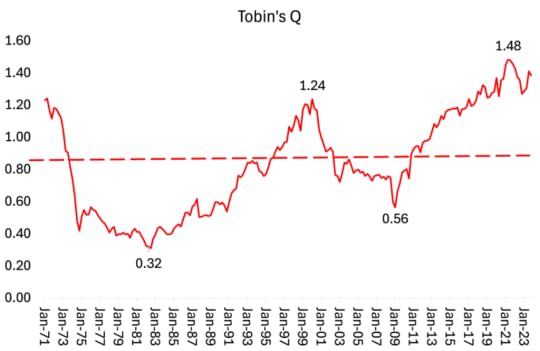

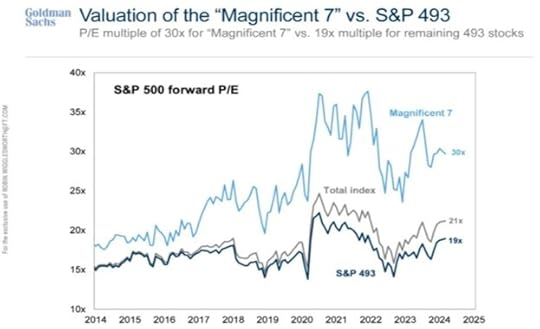

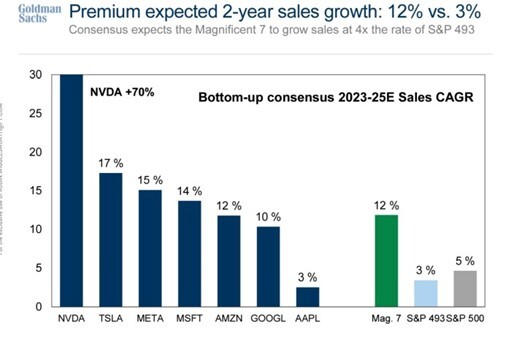

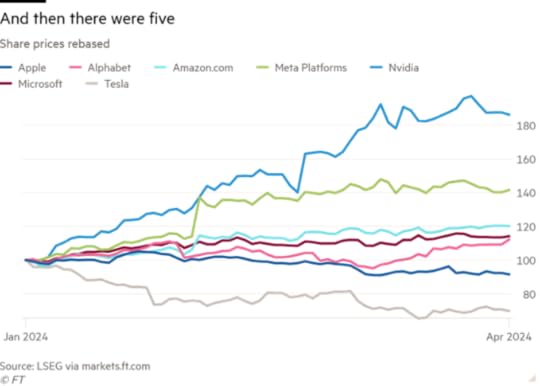

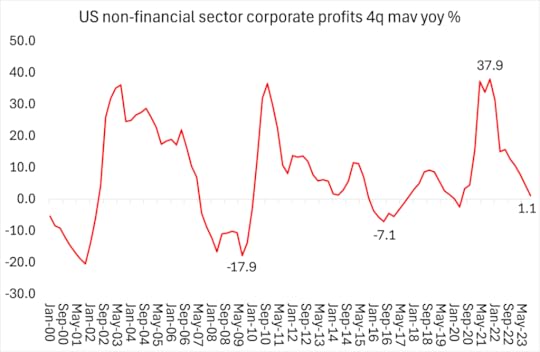

High interest rates as set by the Fed and other central banks are not controlling inflation. Instead, they are raising debt servicing costs for particularly small companies just as corporate revenue growth also slows. Profitability is thus being squeezed, except for the mega ‘Magnificent Seven’ companies.

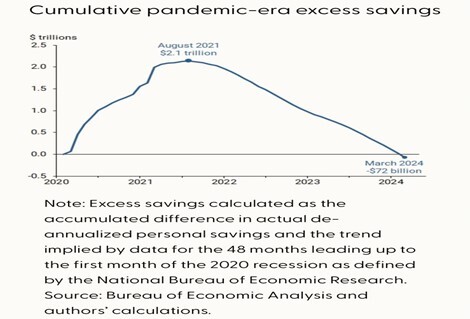

The ‘excess savings’ that households built up during the pandemic lockdowns appear to have been exhausted.

Confidence to spend among American households has fallen to its lowest level in almost two years as Americans become more pessimistic about future economic conditions.

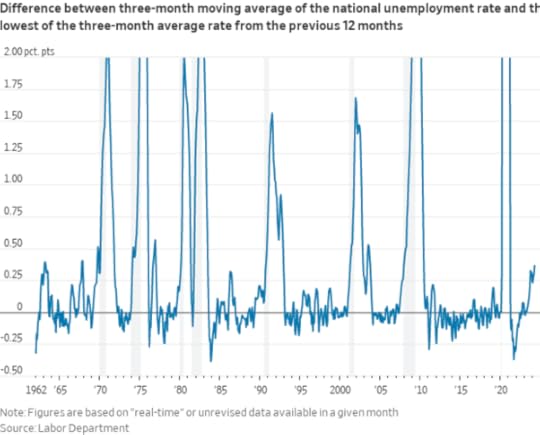

Back last November former NY Fed chief, William Dudley commented: “does the unemployment rate have to rise to 4.25-4.5 per cent for the Fed to achieve their “final mile” on getting inflation back down to 2 per cent? If you think it does, then a hard landing is highly likely.” Claudia Sahm, another former Fed economist reckons that if the unemployment rate runs some 0.5% pts above the bottom for three months, it is a very strong indicator of a recession in output. Currently, this Sahm indicator is now 0.36 pp above the lowest such reading for the previous 12 months. So not yet at the ‘recession’ threshold, but closing in.

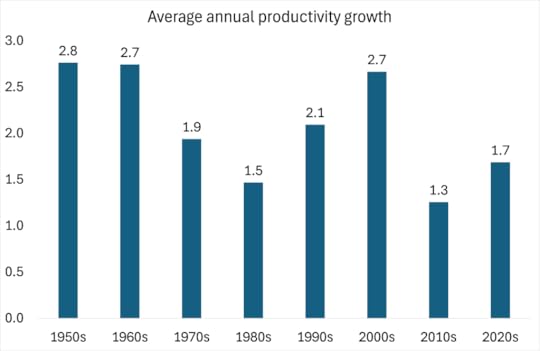

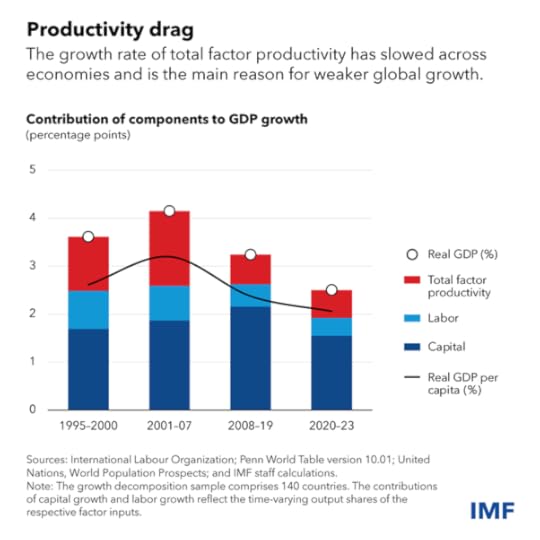

Much of the recent growth in the US economy has been achieved by large increases in immigration. But from here, if the US economy will only avoid stagnation if productivity growth picks up. Moreover, what will keep inflation down would be a rise in output per worker per hour, ie an increase in new value. Up to now, US productivity growth in the 2020s has remained relatively moderate.

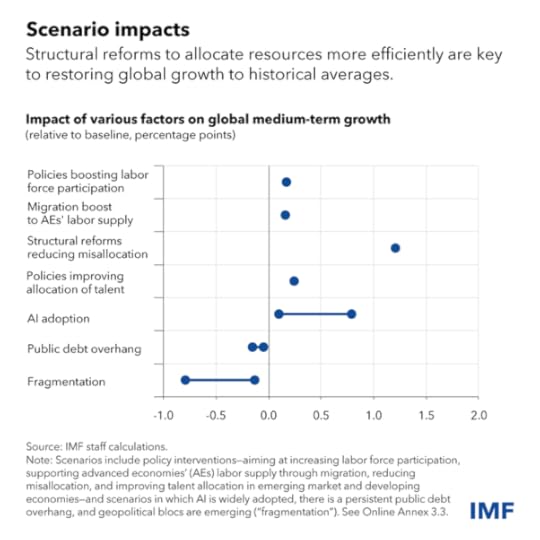

The hope is that AI will bring about a ‘productivity revolution’ setting the US economy on the road to a roaring 2020s where real GDP grows faster than the long-term average while inflation stays low. At the moment, the opposite looks more likely.

April 30, 2024

Inclusive economics and the IMF

The great and the good have just finished attending a special World Economic Forum in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. The theme of the conference for the over 1000 delegates from corporations, governments and international agencies was global cooperation and inclusive growth. In other words, how to reverse the growing international trade wars and rising inequality of income and wealth with policies of cooperation and inclusive economic measures.

There was a certain irony about all these attendees discussing ‘inclusive’ economic policies in Saudi Arabia, infamous for its discrimination and exclusion of women, gays and exploitation of its immigrant population that does most of the labour in the country. Nevertheless, the leaders of the IMF and the World Bank were there in force to promote their new tack of a ‘compact for inclusive growth’. The aim is to ‘reverse’ what they think is only a recent trend towards greater inequality of income and wealth globally.

IMF leader, Kristalina Georgieva was there to press for policies that will boost global collaboration and reduce economic inequality – seemingly a switch by the IMF from competition, labour ‘flexibility’ and fiscal ‘prudence’ which have been the watchwords of IMF economic policy for decades.

It would seem that the IMF is a changed body. Recently it even promoted an article by Nobel prize winner, Angus Deaton, who has been exposing the growing inequalities of income and social mobility in his books and papers. In a piece, called Rethinking my economics, Deaton gave us his mea culpa on the changes in his own views.

Deaton reckoned that mainstream economics (and by implication the IMF, the World Bank and the World Economic Forum) “are in some disarray. We did not collectively predict the financial crisis and, worse still, we may have contributed to it through an overenthusiastic belief in the efficacy of markets, especially financial markets whose structure and implications we understood less well than we thought.” So ‘free markets’ are not as efficacious as claimed and crises cannot be avoided.

Deaton admitted that “I have recently found myself changing my mind, a discomfiting process for someone who has been a practising economist for more than half a century.” You see, the “emphasis on the virtues of free, competitive markets and exogenous technical change can distract us from the importance of power in setting prices and wages, in choosing the direction of technical change, and in influencing politics to change the rules of the game.”

So Deaton has had an epiphany. He now finds that it is the power of capital and its attempt to exploit labour that is the driving force in economies, not technical efficiency or ‘free and fair’ markets. Apparently, at some point in time, not defined by him, “social justice became subservient to markets, and a concern with distribution was overruled by attention to the average, often nonsensically described as the “national interest’.”

More specifically, Deaton criticized what mainstream economics concentrates on rather than on the issues of power and distribution of wealth: “the currently approved methods, randomized controlled trials, differences in differences, or regression discontinuity designs, have the effect of focusing attention on local effects, and away from potentially important but slow-acting mechanisms that operate with long and variable lags.” Indeed, Deaton is right about that. It’s something many outside the mainstream have commented on. Nobel (Riksbank) prizes in economics are handed out for ‘nudging’, RCTs, etc but none for any analysis of inequality or crisis theory. Those issues are persona non grata.

Deaton then turns to the balance of power between capital and labour: “I long regarded unions as a nuisance that interfered with economic (and often personal) efficiency and welcomed their slow demise. But today large corporations have too much power over working conditions, wages, and decisions in Washington, where unions currently have little say compared with corporate lobbyists. unions need to be at the table for decisions about artificial intelligence.” Sounds better, but even if unions are “at the table”, would that really alter the balance of power of capital over labour?

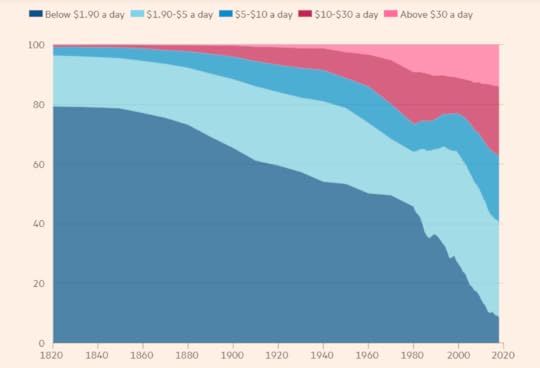

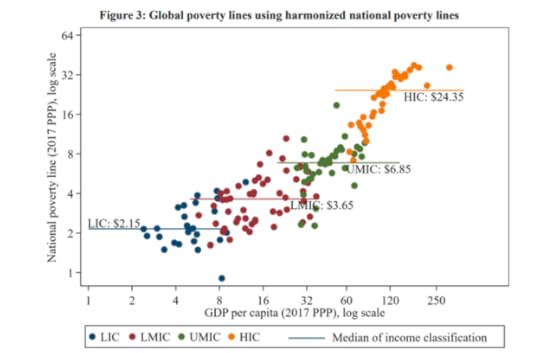

Deaton moved on to reject the idea that ‘globalisation’ has reduced global poverty in the last 30 years. Indeed, as this blog and a multitude of other research has shown, global poverty has not really been reduced at all, once you exclude China. FT columnist and liberal Keynesian economist Martin Wolf would probably disagree having once written a book exactly 20 years ago called Why globalisation works. But even he is worried about the end of global trade and investment growth and the move to protectionism.

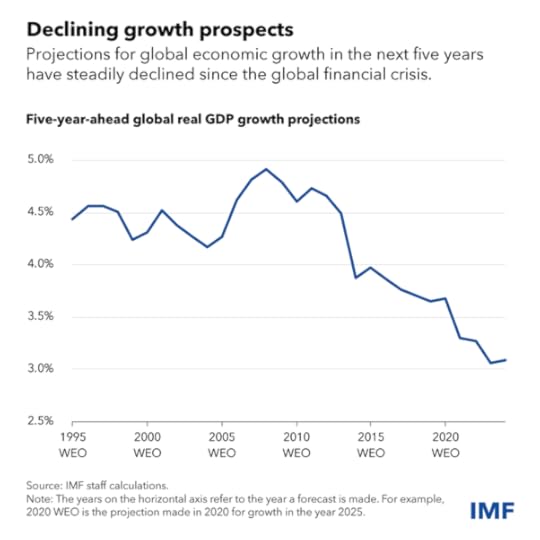

Wolf now claims that this is leading to the end of the elimination of extreme poverty from our planet, which apparently had been in sight. Now there is a risk of a ‘lost decade’ for the world’s poor. According to the World Bank paper presented at the Saudi Arabian jamboree, “The shock of the pandemic and subsequent overlapping crises has exacerbated the challenges facing these economies and led to a reversal in development: over 2020-24, per capita incomes in half of IDA countries—the largest share since the start of this century—have been growing more slowly than those of wealthy economies. One out of three IDA countries is poorer than it was on the eve of the pandemic. Poverty remains stubbornly high, hunger has surged, and, amid fiscal constraints and rising investment needs, the development outlook could take an even bleaker turn—especially if weak growth prospects persist.”

And what Wolf did not say is that he was talking about ‘extreme poverty’, which is currently measured by the World Bank at an adult earning less than $2.15 a day. That makes about 770m people – not small but only 10% of the global population. But as I have discussed many times before on this blog, this poverty threshold is ridiculously low. A poverty threshold of say $7 a day or about $2500 a year would envelope 4bn people. And remember that most of the fall in the official WB poverty rate is confined to China and parts of Asia.

Deaton is also arguing now that the leaders of rich countries must prioritise their own citizens over the world’s poorest people. Fellow ‘progressive’ mainstream economist, Joseph Stiglitz disagrees: “if the west is seen to prioritise its own people, it will fail to encourage global co-operation, for example, on climate change.” But just how much ‘cooperation’ is possible when both Democratic and Republican administrations seek to isolate and weaken China’s economic progress through protectionist and ‘cold war’ policies?

Deaton is not the only mainstream economist who has been striving to understand what he got wrong in the last 30 years. During the 2020 ASSA conference, the largest gathering of mainstream economics in the world, just before the pandemic struck, there was a big meeting organized by a new group calling themselves the Economics for Inclusive Prosperity (EfIP), run by some big mainstream names like Dani Rodrick or Gabriel Zucman. Their stated aim was to show that “the tools of mainstream economists not only lend themselves to, but are critical to, the development of a policy framework for what we call “inclusive prosperity.” While prosperity is the traditional concern of economists, the “inclusive” modifier demands both that we consider the interest of all people, not simply the average person, and that we consider prosperity broadly, including non-pecuniary sources of well-being, from health to climate change to political rights.”

Thus ‘inclusive economics’ is to be based on the assumption that markets and capitalism are still the best of all possible worlds, but they require ‘management and the involvement of people’, so that they can support the wonderful expertise of economists in solving social problems!

Some mainstream economists are attempting to revise the failed economic models of the past 30 years. One new model is called HANK, “Heterogeneous Agent New Keynesian”! Rather than boiling consumers down to an average “representative agent”, Hank models include a fuller distribution of people, whose spending might depend on whether they are underwater on their mortgage, how exposed they are to an inflation shock, the risk that they lose their job etc — and the interaction of all three. So some real problems in consuming goods and services on the market. So far, HANK does not seem to be working too well. As one Keynesian FT columnist put it: “Although it seems clear that accounting for inequality is important, it is not yet clear that economists have landed on exactly the right way to do it. Ultimately, tugging one part of simplified models closer to reality will be limited if other parts are wrong.”

This brings us back to the reality of IMF and World Bank policies against the rhetoric of inclusive economics. The IMF claims it now cares about the negative consequences of fiscal austerity, often citing how social spending should be protected from cuts through conditions that stipulate spending floors. Yet, an Oxfam analysis of seventeen recent IMF programs found that for every $1 the IMF encouraged these countries to spend on social protection, it told them to cut $4 through austerity measures. The analysis concluded that social spending floors were “deeply inadequate, inconsistent, opaque, and ultimately failing.”

But the IMF is worried. Climate change, rising inequality and increased geopolitical ‘fragmentation’ threaten the world economic order and the stability of the social fabric of capitalism. So something must be done. As I reported before, Georgieva argues that “In the years ahead, global cooperation will be essential to manage geoeconomic fragmentation and reinvigorate trade, maximize the potential of AI without widening inequality, prevent bottlenecks on debt, and respond to climate change.”

Global cooperation? We are in a world where rivalry between the major economic powers is intensifying, with the US imposing trade tariffs, technology bans, and military measures against China , while Europe conducts a proxy war with Russia. Corporations, banks and governments continue to subsidise fossil fuel production while avoiding significant cuts in greenhouse gas emissions; and the rich get richer and the poor cannot catch up. We are in a lost decade not just for the world’s poor, but also for reversing global warming and avoiding geopolitical conflict.

April 23, 2024

Further thoughts on the economics of imperialism

Back in 2021, Guglielmo Carchedi and I published a paper in Historical Materialism called The Economics of Modern Imperialism. The paper focused exclusively on the economic aspects of imperialism. We defined that as the persistent and long-term net appropriation of surplus value by the high-technology advanced capitalist countries transferred from the low-technology dominated countries. We identified four channels by which surplus value flows to the imperialist countries: currency seigniorage; income flows from capital investments; unequal exchange (UE) through trade; and changes in exchange rates.

We did not deny other aspects of imperialist domination of the majority of world i.e. in particular, military power and political control of international institutions (UN, IMF, World Bank etc) and the power of ‘international diplomacy’. But in the paper we focused on the economic aspects, which we argued was the ultimate determining factor driving these other extremely important, but determined traits, like military and political domination, as well as cultural and ideological pre-eminence.

In that paper, we paid particular attention to the quantification of unequal exchange (UE) i.e the transfer of surplus value through international export trade. We used two variables in our analysis of UE: the organic composition of capital and the rate of exploitation, and we measured which of these two variables was more important in contributing to UE transfers.

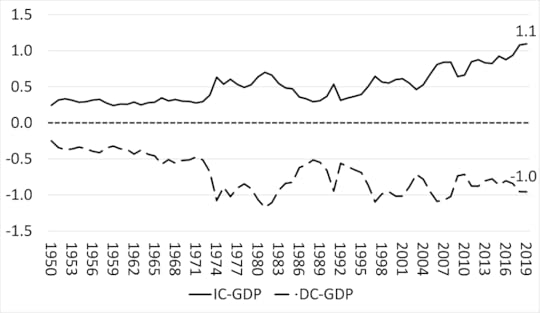

We found that since the end of WW2, the imperialist bloc (IC) annually got around 1% of their GDP through the transfer of surplus value in international trade from the rest of the major ‘developing’ economies (DC) in the G20; while the latter lost about 1% of their GDP in surplus value transferred to the imperialist bloc. And these ratios were rising.

The other large area of transfers of income came from the international flow of profits, interest and rent appropriated by the imperialist bloc from their investment in assets, both tangible and financial, in the periphery. We measured this from the net flows of profits, interest and rent to the imperialist bloc – what the IMF calls net primary credit income – compared to those of the rest of the G20.

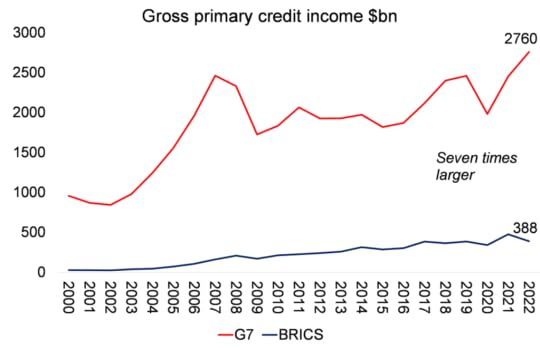

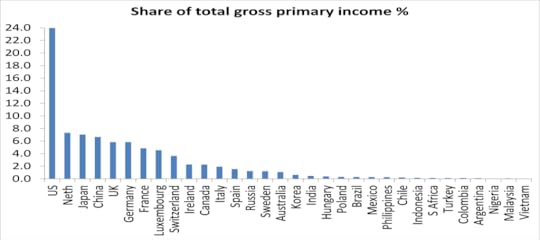

For this post, I decided to update that aspect of economic domination by first comparing the gross primary credit income flows for the G7 and BRICS economies. I just looked at the years of the 21st century. The gross income flows to the G7 are now seven times greater than those received by the BRICS.

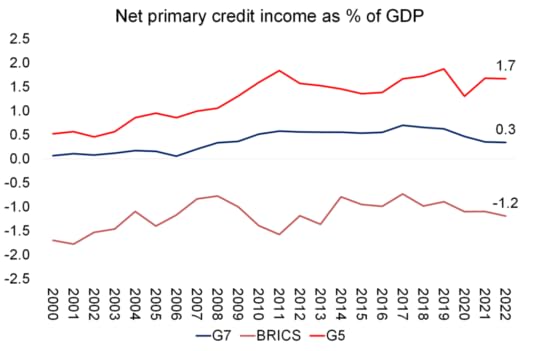

What I also found was that after accounting for the debits ie income flowing out, the NET position was even starker. The annual net flow of income to the G7 economies was around 0.5% of G7 GDP. Indeed, the top five imperialist economies (G5) obtained a staggering 1.7% of their annual GDP from such net inflows. In contrast, the BRICS economies lost 1.2% of their GDP a year in net outflows.

If you look at the net income flows for each G7 and BRICS countries, the biggest gainers over the last two decades have been Japan with its huge foreign asset holdings and the UK, the rentier centre of financial circuitry. Those BRICS countries that have lost the most (as a share of their GDPs) have been South Africa and Russia.

Now, if you add in the 1% of GDP gain/loss in income from international trade described above, then the imperialist bloc benefits by some 2-3% of GDP each year from exploitation of the BRICS, the major economies of the ‘Global South’ – in effect equivalent to their average annual growth in real GDP in the 21st century.

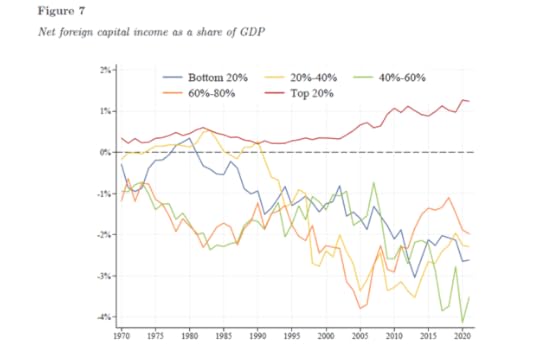

The World Inequality Database (WID), the Paris-based group of ‘inequality’ economists including Thomas Piketty and Daniel Zucman, has just published a deep analysis of what they call the ‘excess yield’ obtained the rich imperialist bloc on assets held abroad. The WID finds that gross foreign assets and liabilities have become larger almost everywhere, but particularly in rich countries, and foreign wealth has reached around twice the size of the global GDP, or a fifth of the global wealth. The imperialist bloc controls most of this external wealth, with the top 20% richest countries capturing more than 90% of total foreign wealth. The WID also included the wealth hidden in tax havens and the capital income accrued from it.

The excess yield is defined as “the gap between returns on foreign assets and returns on foreign liabilities”. The WID finds that this has increased significantly for the top 20% richest countries since 2000. Net income transfers from the poorest to the richest is now equivalent to 1% of the GDP of top 20% countries (and 2% of GDP for top 10% countries), while deteriorating that of the bottom 80% by about 2-3% of their GDP. These results are pretty similar to the results that I got for net credit income flows above.

What was striking to us in our original paper was that the imperialist bloc of countries as we defined it in 2021 was virtually the same as those advanced capitalist economies that Lenin identified as the imperialist grouping in 1915 – around 13 countries or so. There had hardly been any additions to the club – it was closed to new members. Emerging capitalist economies in the last century were condemned to domination by the imperialist bloc. This new study by the WID confirms that conclusion. Over the last 50 years in their survey, the imperialist bloc is unchanged and increasing its extraction of wealth income from the rest -and that includes the likes of China, India, Brazil and Russia. In that sense, these BRIC countries cannot be considered even sub-imperialist, let alone imperialist.

That brings me to a few thoughts on the issue of super-exploitation. Super-exploitation has been defined as where wages are so low that they are below the value of labour power, ie the amount of value necessary to keep workers functioning and reproducing sufficiently to continue to work. Workers with wages and benefit levels below that are paupers in effect. It has been argued that this is the major feature of imperialist exploitation of the Global South. Wages are so low there that they are below the value of labour power. It is super-exploitation that enables the imperialist multi-nationals to make their super profits in trade, invoicing and investment income.

In our original paper, we questioned whether ‘super-exploitation’, which no doubt exists, was necessarily the major driver of surplus value transfer from the poor countries to the rich. In our view, the mechanism of capitalist exploitation and surplus value transfer was doing the job without having to resort to super exploitation as the main cause.

Moreover, international super-exploitation implied that there was some average international wage level that could act as a gauge of the value of labour power globally. But while there are international market prices for export goods and services, there is no international wage. Wages are very much determined by the balance of power between capitalists and workers in each country. Sure, there are international pressures and domestic capitalist companies in the Global South competing in world markets against much more technologically advanced companies in the imperialist bloc can often only survive by driving down wages for their workers. But that means the rate of surplus value or exploitation rises to compensate for the loss of surplus value in international trade with the imperialist companies given their more productive technologies.

Indeed, in our original paper, we found that it was a combination of the two factors: better technology lowering costs per unit for the rich economies; plus a higher rate of exploitation in the poorer countries that contributed to that 1% of GDP annual transfer of profits from the BRICS to the imperialist club. We found that it was about 60:40 for the contribution of more productive technology against higher rates of exploitation in the transfer of surplus value from the poor to rich countries..

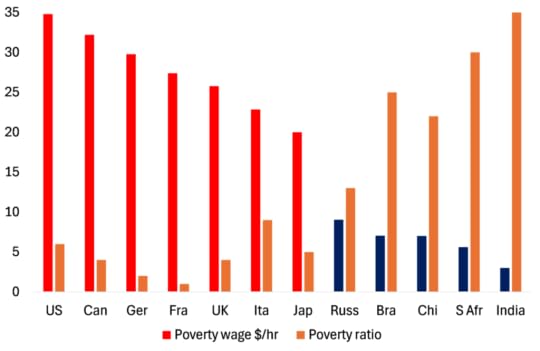

Could we measure whether the transfer of value is due to ‘super-exploitation or not? One way would be to look at national poverty wage levels. They vary sharply across countries and between rich and poor countries. If these levels can be considered the tipping point of wages above or below the value of labour power, then the percentage of workers in both rich and poor countries earning less than these national levels could be considered to be ‘super-exploited’.

The point here is that there are also workers in the imperialist ‘rich’ economies that are ‘super-exploited’ by this criterion. And in turn, there are many workers in the poor countries that are earning above their national poverty wage levels.

Look at the poverty wage levels for the G7 and BRIC economies that I calculated from World Bank sources. Based on the ratio of workers earning less than the poverty wage rate in their respective countries (as provided by the World Bank), I reckon that roughly 5-10% of G7 workers are being ‘super-exploited’, while in the BRICS it’s about 25-30%. But that still means that 70% of workers in the BRICS, while earning way less per hour than G7 workers, are not earning below the value of their labour power on a national basis. Exploitation of workers in the Global South is huge, but super-exploitation as such is not the main cause.

In sum, what these new studies confirm is that imperialism can be quantified in economic terms: it is the persistent transfer of surplus value to the rich countries from the poorest countries of the world through unequal exchange in international trade and through net flows of profits, interest and rent from investments and wealth owned by the rich countries in the poor countries. This process developed some 150 years or so ago and remains.

April 18, 2024

India: Modi and the rise of the billionaire Raj

A general election in India starts today. 970m Indians, more than 10% of the world’s population, will head to the polls in what will be the largest election in history for the Lok Sabha (House of the People) parliamentary elections. The poll will spread across India and take up to 4 June to complete. Opinion polls suggest that Prime Minister Narendra Modi, leader of the Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), and his coalition will win a third successive 5-year term, and win by some distance.

The main challenge to the BJP comes from a coalition of political parties headed by the Indian National Congress, the biggest opposition party. More than two dozen parties have joined to form the Indian National Developmental Inclusive Alliance (“India” for short). Key politicians in this group include Congress president Mallikarjun Kharge, as well as siblings Rahul and Priyanka Gandhi, whose father was the former prime minister Rajiv Gandhi.

The BJP was formed by members of what was basically a Hindu religious fascist party, the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), an organisation modelled on Mussolini’s Black Brigades. Modi was a long-time member of the RSS who then moved seamlessly into the BJP. After winning power in 2014, Modi has cemented his control of government. It is now seen as ‘business-friendly’, but the BJP is still dedicated to turning a multi-ethnic and multi-religious India into a Hindu state, where minorities, particularly Muslims, will be reduced to second-class citizens. With increasing confidence, the Modi government has suppressed any public dissent by liberal democrats and socialists against this trend. Many opposition politicians have been imprisoned on trumped-up charges and prevented from participating in the election and in public debate.

Opinion polls show that the BJP alliance will probably win this election with an increased majority, possibly enough to get a two-thirds majority in parliament, enabling the next government to push through further restrictions and laws against dissent. India’s reputation as the most long standing and largest ‘democracy’ in the Global South is being broken up.

How is it possible for the BJP and Modi to be so popular? First, because of the bulk of the BJP’s political support comes from the rural and more backward areas of this huge country who have not benefited from the strident rise of Indian capitalism in the cities. These areas are bulwarks of Hindu nationalism, incentivised by fear of muslims.

The second reason is the total failure over the decades of the main capitalist party and standard bearer of Indian independence, the Congress party, to deliver better living standards and conditions for the hundreds of millions, not only in the country but in the city slums. Congress appears to millions as the party of the establishment controlled by a family dynasty (the Gandhis), while the BJP appears to many as the populist party of the forgotten people.

The Modi government makes much of its handouts to the poorest. Welfare schemes have been expanded such as providing free grain to 800 million of India’s poorest, and a monthly stipend of 1,250 rupees ($16; £12) to women from low-income families paid into half a billion new bank accounts, along with free gas connection in millions of houses for the poor and over 40 million toilets constructed.

But in reality, the BJP and the Modi government is fully integrated and supportive of Indian capital, especially big capital. PM Modi has made the economy a major part of his election pitch, pledging at a rally last year to lift the country’s economy “to the top position in the world” should he win a third term. The Modi’s government’s key policy is Viksit Bharat 2047—a plan to make India a developed nation by 2047, 100 years after independence, something China is targeting for 2030.

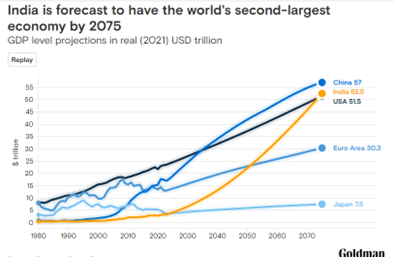

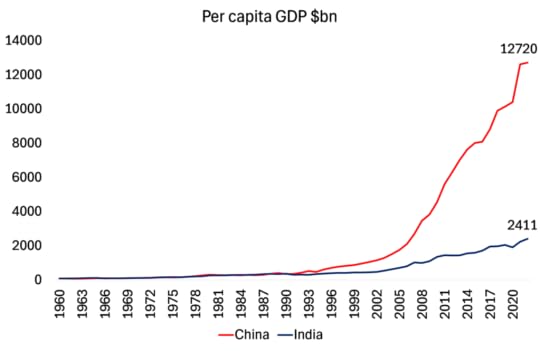

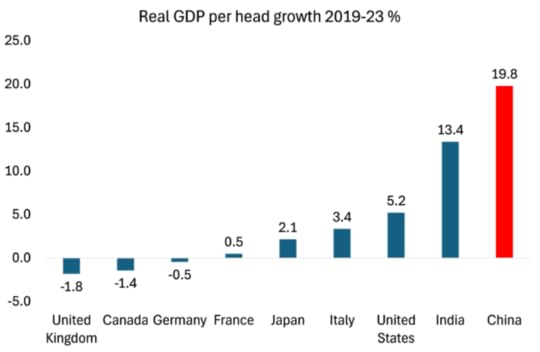

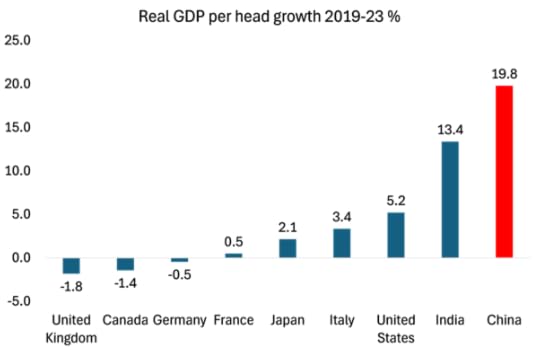

The Indian media and Western economists laud the strong economic growth that India is apparently enjoying under the Modi government. According to the official figures, Indian real GDP grew 8.4% yoy in the last quarter of 2023 and 7.6% over the whole year, up from 7.0% in 2022. So ecstatic are mainstream economists about the success of Indian capitalism under Modi that talk of his neo-fascist past and current repressive measures are ignored. Instead, all the talk is of India ‘catching up’ with China and even surpassing its real GDP soon. For example, Goldman Sachs projects India will have the world’s second-largest economy by 2075.

The forecast is that India will grow even faster while China’s growth slows and soon India will contribute more to global growth than China. India will take over China’s lead in manufacturing and technology and thus prove that a privatized, free market economy can triumph over a state-led planned one that is China. According to Bloomberg Economics, India could become the world’s No. 1 contributor to GDP growth as early as 2028 as India’s economic growth will accelerate to 9% by the end of this decade, while China will slow to 3.5%!

But all this is just hype. Take the growth figures. The perennial cry from Western economists when they get the growth figures for China is that they are faked. But actually, it is India’s national statistics office that is being ‘economical with the truth’. GDP figures contain dubious categories like ‘discrepancies’. These refer to the difference between real GDP growth of about 7.5% a year and real domestic expenditure growth of just 1.5% a year. They should be the same theoretically, but they are not – and the national statistical office ignores the latter. Part of the reason for the ‘discrepancy’ is that India’s government statisticians are ‘deflating’ money GDP into real GDP by a price deflator based on wholesale production prices and not on consumer prices, so that the real GDP growth figure is much higher than the real increase in spending. Also, the GDP figures are not ‘seasonally adjusted’ to take into account any changes in the number of days in a month or quarter or weather etc. Seasonal adjustment would have shown India’s real GDP growth well below the official figures.

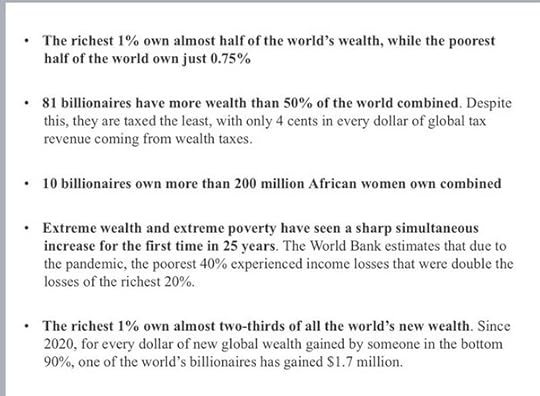

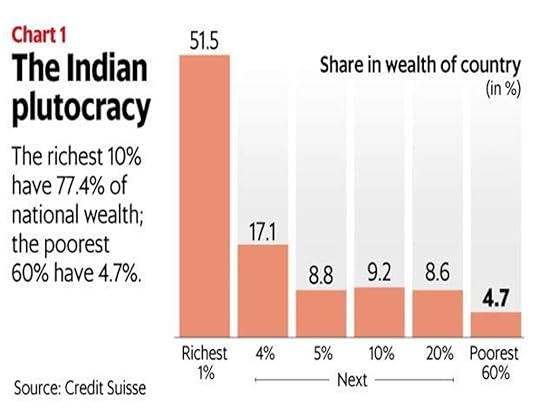

What exposes the unrealistic figures the most is a recent paper on India’s staggeringly extreme inequality of wealth and income. The World Inequality Lab finds that “the present-day golden era of Indian billionaires has produced soaring income inequality in India—now among the highest in the world and starker than in the U.S., Brazil, and South Africa. The gap between India’s rich and poor is now so wide that by some measures, the distribution of income in India was more equitable under British colonial rule than it is now.”

The top 10% of the Indian population now holds 77% of the total national wealth. Between 2018 and 2022, India is estimated to have produced 70 new millionaires every day. Billionaires’ fortunes increased by almost 10 times over the last decade and their total wealth is higher than the entire national budget of India for the fiscal year 2018-19. The current total number of billionaires in India is 271, with 94 new billionaires added in 2023 alone, according to Hurun Research Institute’s 2024 global rich list.. That’s more new billionaires than in any country other than the US, with a collective wealth that amounts to nearly $1 trillion—or 7% of the world’s total wealth. A handful of Indian tycoons, such as Mukesh Ambani, Gautam Adani, and Sajjan Jindal, are now mingling in the same circles as Jeff Bezos and Elon Musk, some of the world’s richest people.

The report also found that the rise in inequality had been particularly pronounced since the BJP first came to power in 2014. Over the last decade, major political and economic reforms have led to “an authoritarian government with centralization of decision-making power, coupled with a growing nexus between big business and government,” the report states. This, they say, was likely to “facilitate disproportionate influence” on society and government.

In contrast, many ordinary Indians are not able to access the health care they need. 63 million of them are pushed into poverty because of healthcare costs every year – almost two people every second. Indeed, it would take 941 years for a minimum wage worker in rural India to earn what the top paid executive at a leading Indian garment company earns in a year. While the country is a top destination for ‘medical tourism’, the poorest Indian states have infant mortality rates higher than those in sub-Saharan Africa. India accounts for 17% of global maternal deaths, and 21% of deaths among children below five years.

Rural distress, stagnation and falling farming incomes have led to a number of protests by farmers. According to Samyukta Kisan Morcha, an umbrella of farm unions, over 100,000 farmers have committed suicide in the last ten years of Modi’s rule. India ranks 111th of the 125 nations in the Global Hunger Index (2023) report. India is home to over a third of the world’s malnourished children, which is not only a health crisis but has a wider impact on the economy. A 2023 joint report by FAO, UNICEF, WHO and WFP, found that 74% of the population cannot afford healthy food.

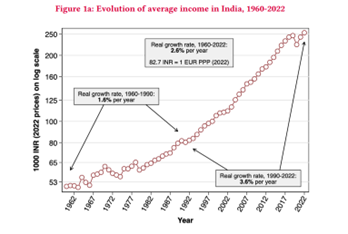

The WID averaged out national income growth between rich and poor. On that measure, growth in incomes in India is nowhere near the hype levels surrounding real GDP growth. Average real income growth in India is around 3.6% a year compared to the 6-8% claimed for real GDP growth.

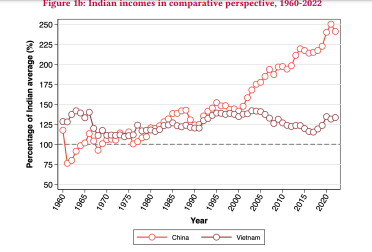

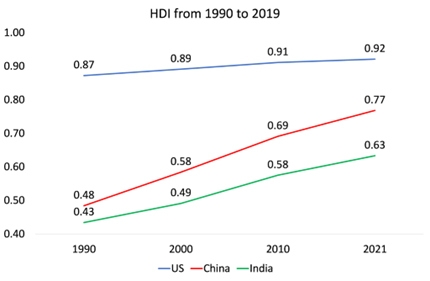

The idea that India is or will close the gap with China is a pipedream. Here the WID paper shows the gap between China’s average income, and that of India and Vietnam. Even Vietnam is holding its advantage over India.

India’s $3.5 trillion economy remains dwarfed by the $17.8 trillion Chinese economy. It would take a lifetime for India to catch up with its shoddy roads, patchy education, red tape and a lack of skilled workers.

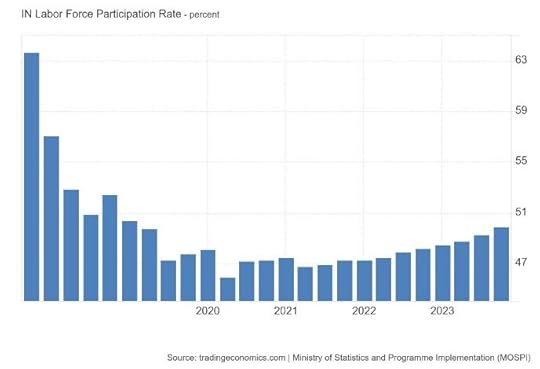

The Indian economy is failing to create jobs, especially those that would support a dignified standard of living. Apart from public administration, the most rapid income growth by far this past quarter (at 12.1%) was in finance and real estate. But this neo-liberal feature of Indian development, now augmented by “fintechs,” generates only a handful of jobs for highly qualified Indians. Among other growth sectors, construction (helped by the government’s infrastructure drive) and low-end services (in trade, transport, and hotels) mostly create financially precarious jobs that leave workers one life event away from severe distress. The labour force participation rate in India has declined over the last 15 years. Under Modi, less than half the adult working population is employed.

Two-thirds of Indian workers are employed in small businesses with less than ten workers, where labour rights are ignored – indeed most are paid on a casual basis and in cash rupees, the so-called ‘informal’ sector that avoids taxes and regulations. India has the largest ‘informal’ sector among the main so-called emerging economies. India’s post-COVID manufacturing performance has been particularly weak. This reflects the country’s chronic inability to compete in international markets for labour-intensive products – a problem made worse by the slowdown in world trade and weak domestic demand for manufactured products.

Overall, government spending on health has fallen and now hovers around an abysmal 1·2% of gross domestic product, out-of-pocket expenditure on health care remains extremely high, and flagship initiatives on primary health care and universal health coverage have so far failed to deliver services to people most in need. Another contentious issue is the lack of credibility of India’s continuing claim that only 0·48 million people died as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, whereas WHO and other estimates are six to eight times larger (including excess deaths, most of which will be due to COVID-19). India is right down at the bottom in terms of government spending. Only South Africa which is in a serious economic situation is lower than India.