Michael Roberts's Blog, page 11

August 14, 2024

Bangladesh: the ‘Global South’ debt crisis intensifies

The overthrow of the Sheikh Hasina’s dictatorial government in Bangladesh by students and the populace last week is a startling outcome of the economic nightmare that many so-called developing economies are experiencing now: stagnant trade, rising debt interest costs and severe austerity being imposed by the IMF and private capital in return for ‘financial aid’.

Bangladesh was regarded as an economic success story up to the government’s fall – at least in the Western media and among mainstream economists. The IMF was forecasting that Bangladesh’s GDP would soon exceed that of (tiny) Denmark or Singapore. Its GDP per person was already bigger than neighbouring India’s. The country’s average GDP growth over the past decade, according to government statistics, was around 6.6%. As late as April this year, the World Bank reckoned that Bangladesh would grow by 5.6% this year, led by its highly successful garment industry, which relies on cheap labour sweat shops to gain market share globally. It accounts for more than 80% of the country’s exports. The government was forecasting that by 2025, Bangladeshi factories would produce 10% of the world’s apparel.

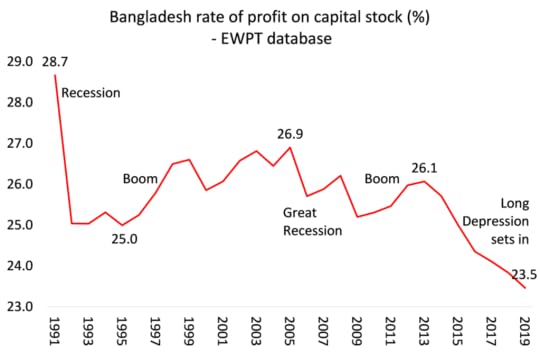

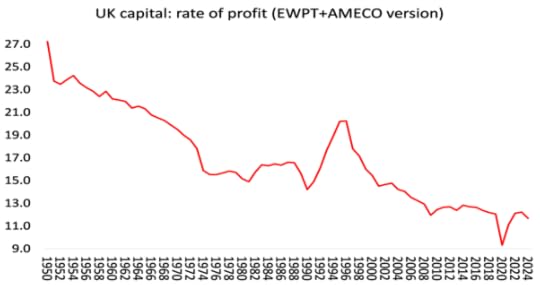

But beneath the surface, the rise of the economy was based on faltering profitability for Bangladesh capital. The relative recovery in profitability after the global Great Recession of 2008-9 began to reverse from 2013, leading up to the pandemic slump in 2020.

The crisis came quickly this year. Within weeks of the World Bank’s’ optimistic April report, the reality emerged: the economy was deteriorating fast. Huge infrastructure projects were failing and eating into resources, riddled as they were by corruption. Rising interest costs on borrowing, higher inflation and falling export demand drove many companies into default with over $20bn in ‘non-performing loans’. The government handed out huge subsidies (billions) to private companies to ensure electricity coverage in the country. The rich shareholders prospered and took the opportunity to siphon their wealth out of the country; while remittances from Bangladeshis working abroad fell back.

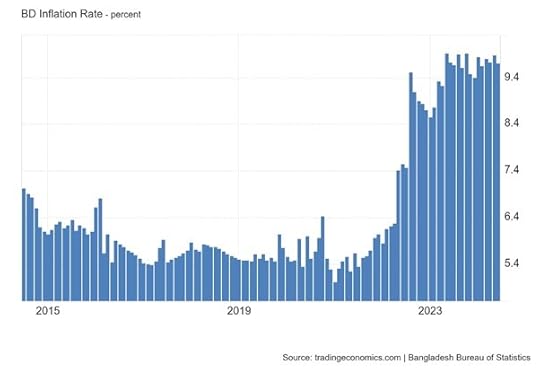

In contrast to the rich, the majority of the country’s 170m people suffered. Most Bangladeshi garment workers are women (50-80%), while the better-paid factory supervisors tend to be men. Most of the women earn just a minimum wage — 8,000 taka, or about $80 per month. With rising food prices, that’s nowhere near enough. “All daily goods like rice, eggs, vegetables — everything is getting more expensive,” said Taslima Akhter, president of Bangladesh Garment Workers Solidarity, a labour group. “Also the price of gas for cooking [at home] and electricity [in factories]. So this is a big problem for workers and the industry.”

A BBS survey conducted in the middle of 2023 revealed that around 37.7 million people experienced moderate to severe food insecurity in the country. More than a quarter of families were taking out loans to cover the cost of daily necessities, including food. A survey by the South Asia Network on Economic Modeling, a think tank, showed that 28% of households resorted to borrowing money to survive. The average amount of loans per household in the country nearly doubled between 2016 to 2022.

Bangladesh had been registering increases in life expectancy for decades. In 2020, it reached 72.8 years, the highest to date. But since then, the pattern of growth has been broken. In 2021, there was a decline to 72.3 years onwards. The mortality rate for children under five years of age, newborns, and children under one year has increased.

There has been a drop in students at the secondary-school level and an increase of NETT (not in employment, education, or training) among the youth population. According to the BSVS-2023, the share of children between five and twenty-four years not in educational institutions has risen since the COVID-19 pandemic. In 2020, at the onset of the pandemic, 28% were out of educational institutions; by 2023, the share reached 41%! Around 40% were neither in school nor in employment, up 10% pts in eight years. The student protests that brought down the government were triggered by the job quota system that reserved 30% of government jobs for families of 1971 war veterans (mainly government families). Protesters demanded the replacement of the quota with a merit-based system.

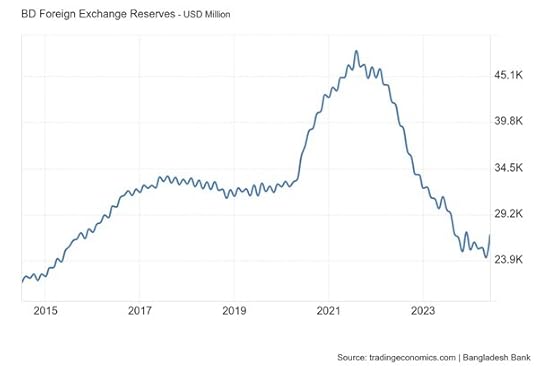

In June 2024, the IMF admitted that “stubbornly high international commodity prices and continued global financial tightening have amplified macroeconomic vulnerabilities” Foreign exchange reserves declined sharply due to interventions to prop up the Bangladesh currency , the taka. FX reserves plummeted from $46bn in 2021 to just $19bn.

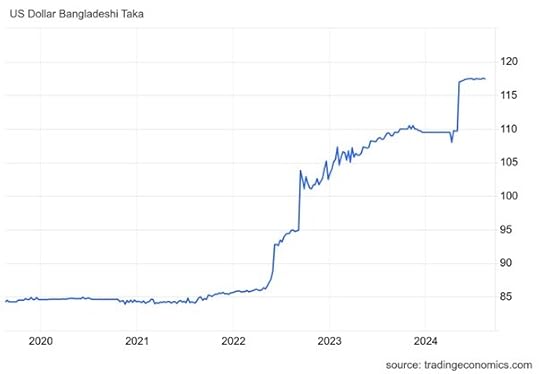

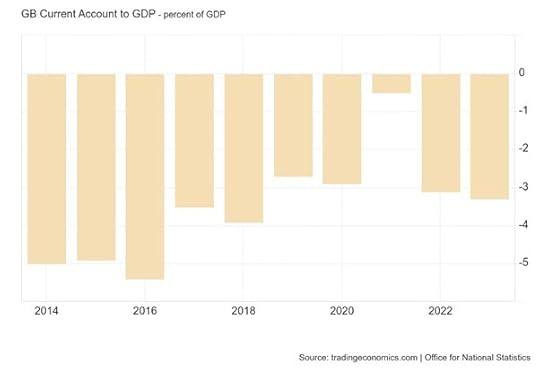

The taka fell over 20% against the US dollar, driving up the costs of servicing foreign debt. The external account went into deficit by up to 4% of GDP a year.

The government was forced to turn to the IMF for ‘relief’. The IMF approved a small package of $3.3bn in early 2023. Then this year that was raised to $4.7bn designed to relieve pressure on the FX. And the IMF handed over $1.1 bn in June.

But now all is in flux. After a brutal attempt to suppress the protests with the army and police killing over 300 people, Hasina finally fled the country. A temporary government has been formed under Nobel Peace Prize winning economist Muhammad Yunus to lead an interim government. But don’t expect any improvement under his administration (read this: https://www.cadtm.org/Bangladesh-Who-is-Muhammad-Yunus-the-new-primer-minister). Yunus will again turn to the IMF for support in return for which the IMF will impose severe austerity measures.

The Bangladesh economic crisis is being repeated across the Global South – in Kenya where riots have ensued to reverse IMF-demanded tax rise; in Pakistan where the government has turned for the seventh time to the IMF for funding; in Egypt which is on the brink of default; and in Nigeria, where hunger rules. And of course, Argentina.

And the IMF surcharges any debtor that fails to pay on time, which only makes loan repayment harder. The number of countries paying surcharges annually has nearly tripled in 5 years, from 8 in 2019 to 23 in 2024. Over the past six years, the IMF charged $7 billion in surcharges.

Through 2033, CEPR estimates that the IMF will charge approximately $13 billion in surcharges. Argentina alone will owe an estimated $6 billion, followed by Ukraine, with a debt of nearly $3 billion. On average, surcharges will represent 26% of all charges and interest levied on surcharge-paying countries. For some borrowers, such as Costa Rica and Ecuador, surcharges will represent even more.

[image error]In my next post, I shall discuss a new report by the World Bank which shows that the Global South is not just failing to ‘catch up’ with the Global North, but instead is falling further behind.

August 10, 2024

Market meltdown – does it mean a recession?

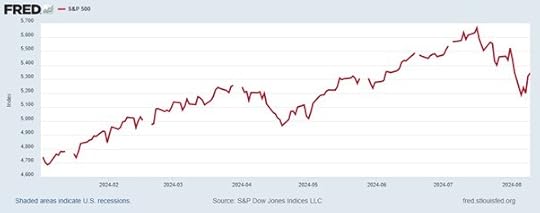

Last week’s meltdown in the stock markets of the major economies, which started in the US, reversed this week. But the fall in the US S&P-500 index of the stock prices of the top 500 American companies is still down from its peak in mid-July and from the start of the ‘meltdown’ at the end of July. So it would appear that the great upswing in US stocks since the beginning of the year, and particularly since May, is over.

What caused this turn downwards and does it herald something more serious for the US economy? Well, this is what I said in April – word for word.

“In Q1 2024, global stock markets recorded their best first-quarter performance in five years, buoyed by hopes of a soft economic landing in the US and enthusiasm about artificial intelligence. A MSCI index of worldwide stocks has gained 7.7% this year, the most since 2019, with stocks outperforming bonds by the biggest margin in any quarter since 2020.

“This global surge has been helped mainly by the US stock index, the S&P 500, which closed at a record high on 22 separate occasions during the last quarter. The AI hype has fuelled the market’s gains, with the major AI chip designer Nvidia adding more than $1tn in market value, equivalent to about one-fifth of the total gain for global stock markets this year! Nvidia’s market capitalisation rose by about $277bn — roughly equivalent to the market value of every listed company in the Philippines, according to HSBC.

“Euphoria in the US stock market is continuing as investors are convinced that any US economic recession is off the agenda, and instead US economic growth will accelerate this year and drive up global corporate profits. Are they right?

“Finance capitalists usually measure the value of a company by the share price divided by annual profits. If you add up all the shares issued by a company and multiply it by the share price, you get the ‘market capitalisation’ of the company — in other words what the market thinks the company is worth. This ‘market cap’ can be ten, 20, 30 or even more times annual earnings. Another way of looking at it is to say that if a company’s market cap is 20 times earnings and you bought its shares, you would have to wait for 20 years of profits to double your investment. And we can get a sort of average price of all the company shares on a stock market by using a basket of share prices from a range of companies and index it. That gives us a stock market index like the S&P-500 index for the top 500 US companies in market capitalization.

“As company stock prices are based on the subjective judgements of financial investors, they can get way out of line with the actual profits made by companies and relative to the value of the assets (machinery, plant, technology etc) that companies own. That’s the current situation.”

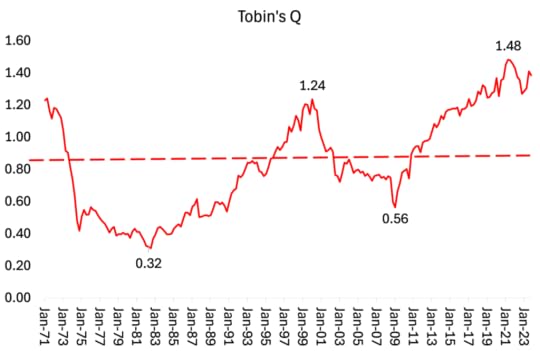

So the US and other stock markets were suspended in mid-air, well above real value. As measured by the ratio of stock price values of the S&P-500 to the book (monetary) value of the assets of the 500 companies, i.e. Tobin’s Q was near a historic record high.

But: “Whatever the fluctuation in stock prices, eventually the value of a company must be judged by investors for its ability to make profits. A company’s stock price can get way out of line with the accumulated value of its stock of real assets or its earnings, but eventually the price will be dragged back into line.” In April, I said: “Fundamentally, if US corporate profit growth slows (and it has been) and interest rates on borrowing stay high, then the squeeze on stock prices will eventually lead to a reversal of the current market boom.”

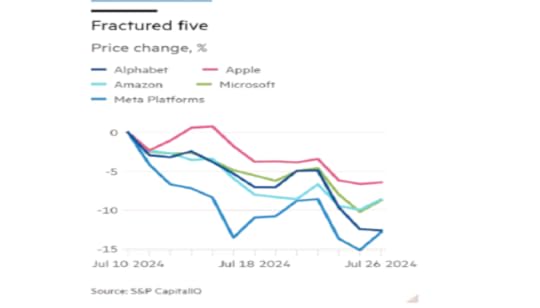

Back then, there were already faultlines appearing in the boom (called a ‘bull market’). The S&P 500 stock index (for the top 500 US companies) was almost totally driven by the seven large social media, tech and chip companies – the so-called Magnificent Seven (Alphabet, Amazon, Apple, Meta, Microsoft, Nvidia and Tesla). The market prices of the other 493 companies in the S&P index had hardly moved relative to earnings. So the whole market index depended on the Magnificent Seven sustaining their profit gains.

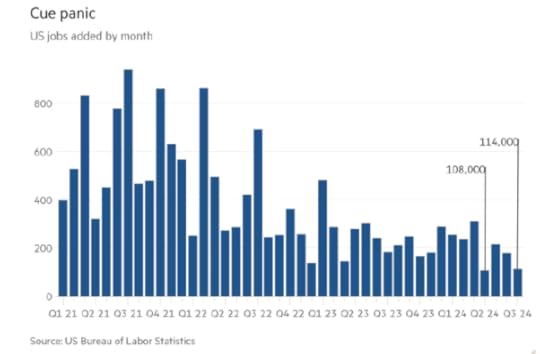

The trigger for the meltdown came when the US Federal Reserve at its end-July meeting decided not to reduce its policy interest rate because it thought inflation remained ‘sticky’. Just days later the US jobs figures for July were announced and they showed very weak growth, with net jobs up only 114k, half the previous 12 months average rise.

And the official unemployment rate rose to 4.3%, triggering the so-called Sahm rule that predicts a recession; and well above its post-pandemic low of 3.4% in April 2023. The Sahm Recession Indicator (named after Claudia Sahm, a former Federal Reserve economist) is a pretty accurate signal for the start of a recession. It is “when the three-month moving average of the national unemployment rate (U3) rises by 0.50 percentage points or more relative to its low during the previous 12 months.” And that was breached.

At the same time, the US manufacturing sector has remained deep in contraction territory according to the latest ISM survey of manufacturing activity, which fell to 46.6 in July from 48.5 in June. (Any score below 50 means contraction.) July’s figure was the sharpest contraction in US factory activity since November 2023 and the 20th decline in activity during the last 21 periods,

Then as the quarterly corporate earnings results came out at the end of July, despite proclaimed good results, investors started to sell as they were worried that the huge capital spending on AI and semi-conductors planned by the Magnificent Seven would not deliver better earnings in the future. These companies have invested billions into their AI infrastructure, but investors now started wonder about the returns on this investment. Equity investor company, Elliot management said AI is “overhyped with many applications not ready for prime time” and that uses are “never going to be cost-efficient, are never going to actually work right, will take up too much energy or will prove to be untrustworthy.” Indeed, surveys show that, so far, only 5% of firms are using AI in their operations, suggesting limited growth, or at least slow growth.

The situation was compounded by the decision of the Bank of Japan to raise its policy interest rate with the aim of boosting the value of the yen against the dollar and to control rising inflation. This weakened what is called ‘the carry trade’ in currency speculation. This is where speculators borrow lots of yen at previously zero interest rates and then buy US dollar assets (such as tech stocks). But the Bank of Japan’s action meant that the cost of borrowing in yen suddenly rose and so speculation in dollar assets fell back.

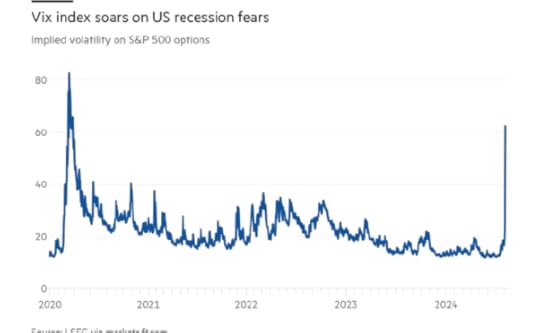

All these factors came to a head last Friday and again on the following ‘Black Monday’ . Investors panicked – as expressed by the so-called Vix index that measures investor ‘fear’.

But does this meltdown mean that the US economy is going into recession? Well, since the meltdown, all the mainstream economists have rushed to assure investors that actually all is well. The FT shouted: “everyone calm down!” Evidence was presented at length that unemployment is still low, inflation will fall further and the US economy as a whole is still growing.

And it’s true that stock markets are not the ‘real’ economy? In essence, what stock market prices express are investor expectations (rational or irrational) about future profits and profitability . It’s profits that eventually call the tune. US corporate profits started to contract this time last year but since then have made a modest recovery.

So maybe this meltdown is just a ‘correction’, taking stock prices down closer to corporate earnings growth. That’s what happened in 1987 when there was an even larger stock market meltdown. Within weeks, the markets recovered to reach new highs.

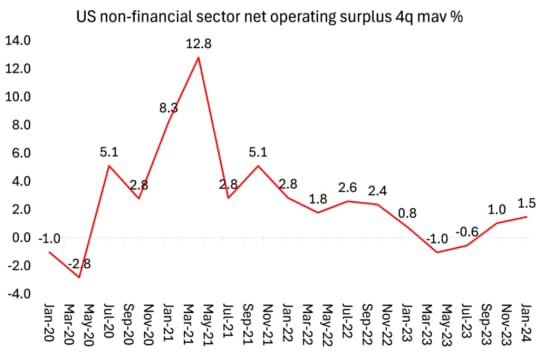

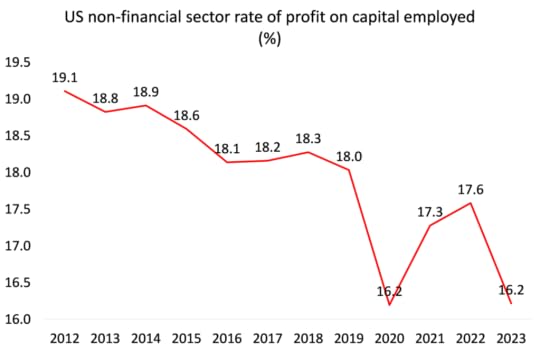

On the other hand, the profitability of non-financial sector capital (not profits as such) is at its lowest since the end of the Great Recession on 2008-9. That spells recession in the future.

It’s not 1929, when the stock market dived and heralded the beginning of the Great Depression. US corporate profitability had already fallen over 13% from 1924. But even if this stock market meltdown does not presage a recession in real output, investment and employment right now, the current trend in profitability suggests a recession will eventually occur before this decade is out.

August 8, 2024

WAPE 2024

Last weekend the 17th Congress of the World Association of Political Economy (WAPE) took place in Athens, Greece. WAPE is a Chinese-run academic economics organisation, linking up with Marxist economists globally. “Even though that might seem like bias, the WAPE forums and journals still provide an important outlet to discuss all the developments in the world capitalist economy from a Marxist perspective. Marxist economists from all over the world are welcome to join WAPE and attend WAPE forums.” (WAPE mission statement).

I covered the 15th Congress in Shanghai watching online panels. Unfortunately, I was unable to attend the 17th Congress and there were no virtual panels. But using the WAPE conference program, I was able to identify some of the presentations and papers.

I can only select a few papers that came into my orbit. But let’s start with the section on technology. Mike Nolan from the Rochester Institute of Technology presented a paper on Revolutionary Technology: The Political Economy of Left-Wing Digital Infrastructure. Nolan argues that the ‘decentralised nature’ of the internet and online social media tends fracture and weaken class politics. What is needed is a “unified digital infrastructure” so that “left-wing organizations can share the costs of maintaining infrastructure and, at the same time, better exert control over the form that infrastructure takes”. Sounds sensible, but the feasibility of establishing such ‘left-wing digital infrastructure’ is not clear.

João Romeiro Hermeto of the Free University of Berlin presented on his book, The Paradox of Intellectual Property in Capitalism, in which he discusses the nature of intellectual property under the capitalist mode of production. In particular, he attempts to explain what knowledge is and how it is produced. He emphasizes how knowledge is turned into ‘intellectual property’ by big pharma and the tech giants. What is at stake is the control over the appropriation of social surplus labour, which in capitalism takes the specific form of surplus-value. This is no doubt true, but I was unsure where the book then took us. You may want to compare Hermeto’s analysis of knowledge in his book with Guglielmo Carchedi’s analysis of knowledge and mental labour in our joint book, Capitalism in the 21st Century (see chapter 5, pp 161-187.)

There was a very important section on the WAPE program called quantitative political economy. Thanos Poulakis and Persefoni Tsaliki from the University of Macedonia revisited their perceptive analysis of purchasing power parity (PPP), the principal way in which the IMF and the World Bank measure GDP in economies. The purpose of the Purchasing Power Parity exchange rate is to convert each country’s local currency into a common baseline currency—usually the US dollar. Thus, economic performance can be compared using a single common currency rather than dozens of national currencies whose market exchange rates can change rapidly.

Poulakis and Tsaliki show that exchange rates are actually determined by real labour costs and if these unit costs were measured carefully, more accurate estimates of PPP would be achieved and more effective foreign exchange rate policies could be designed. Such empirical analysis is not new. See the paper by Francisco Martinez. But Poulakis and Tsaliki have extended previous work now to 163 countries.

An important conclusion from this is that trade surpluses and trade deficits are the direct consequences of the relative competitive positions of nations in terms of real labour costs. So exchange rate devaluations will only have a temporary effect on national competitiveness if the general conditions of production are not improved. As long as the least competitive economies at the international level cannot improve their general technical conditions of production, their national industries will be structurally uncompetitive and as a result, these countries would have permanent trade deficits.

Carlos Alberto Duque Garcia was also there to present on ‘Terms of trade and the rate of profit: a suggested framework and evidence from Latin America’. Carlos Duque from the Autonomous Metropolitan University in Mexico has already done excellent empirical work on waves of profitability in Colombia, entitled Economic Cycles, Investment and Profits in Colombia, 1967-2019. In that paper, Duque found evidence in favour of Marx’s hypothesis that both the rate of profit and the mass of profits determine investment; while on the contrary, there was no evidence that investment determines either the rate of profit or the mass of profits. This was yet another confirmation of Marx’s law of profitability.

Dimitris Paitaridis and Lefteris Tsoulfidis also presented on whether an accurate measure of gross capital stock matters in measuring the rate of profit on capital. This might seem self-evident. But it has become a subject of some debate. Some argue that capital stock cannot be measured using official data because it is based on bogus neoclassical concepts. And it is certainly true that capital stock measures used in official databases (e.g. the EU’s AMECO) are questionable. But the authors have produced a number of excellent papers on capital stock measurements and provide extensive support for the empirical relation between a rising organic composition of capital (capital stock increasing more than variable capital) and a falling rate of profit on capital stock.

Nikolaos Chatzarakis also presented on the nature of long and short cycles in capitalist accumulation. Again, this was further work on cycles that the author and others at the University of Macedonia have conducted before. Their cycle model showed periodicity conditioned by the long-run movement of profitability and behind that, the growth of the rate of surplus value as the regulating variable for cycles. Indeed, the extremely valuable contribution to Marxist economic theory and empirical studies by the Marxist scholars in Macedonia and Greece at large cannot be underestimated. See my review of Tsoulfidis and Tsaliki’s groundbreaking book.

And talking of theory, Marx’s law of value came under scrutinization in Fred Moseley’s new book ‘Marx’s Theory of Value in Chapter 1 of Capital: A Critique of Heinrich’s Value Form Interpretation’. I have reviewed the arguments in this book following a debate between Moseley and German Marxist Michael Heinrich at last year’s Historical Materialism conference. I know which side in that debate I was on (Moseley’s).

Importantly, at WAPE 2024, Christos Balomenos from the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, presented his doctoral thesis: ‘A Theoretical and Archival Investigation of Marx’s Analysis of Interest-Bearing Capital and Credit in the Manuscript of 1864-65 and its editing by Engels.’ In this paper, Balomenos investigated Heinrich’s arguments for the existence of a crucial theoretical shift in Marx’s thought during the 1870s centered around his supposed doubts about the validity of the law of the falling rate of profit. In his investigation, he concludes that “the manuscripts and letters that Heinrich invokes to support his arguments do not substantiate any uncertainty on Marx’s part about the validity of the law of the falling rate of profit nor a shift of his opinion during the 1870s towards the primacy of capitalist circulation, and especially credit, for explaining economic crisis.”

Naturally enough at a conference of this nature, imperialism and China were prominently discussed. But unfortunately, I cannot offer any coverage of these subjects this time. The main plenary at WAPE was on Lenin’s economics, in the 100th year since his premature death from an assassin’s bullet in 1924. There was a battery of leading Marxist economists on the platform. I was invited to speak at this plenary, but, as I said, was unable to make it. However, all is not lost because I shall be online with a special meeting on Lenin’s contribution on 1 September hosted by the UK-based Arise group.

An uneven and inadequate account of this valuable conference – hopefully I can do better next time.

August 1, 2024

The Fed fails

At yesterday’s end July meeting, the US Federal Reserve Bank held back from cutting its policy interest rate from the current high of 5.25-5.5%. This was despite recognizing that the US economy was ‘cooling’, unemployment was starting to rise and economic activity was weakening.

The problem for the Fed was, as always, the balance, on the one hand, between keeping the cost of borrowing high in order to drive down inflation and on the other hand, against the risk of high borrowing costs causing households to reduce spending and businesses to cut back on investment and employment.

The Fed, like other central banks in the major economies, has got an arbitrary (and rather pointless) price inflation rate target of 2% a year; but unlike other central banks, it has a ‘dual mandate’ to try preserve employment and economic growth as well as getting inflation down. Can the Fed achieve this dual mandate? The Fed likes to claim that it will; also the consensus among mainstream economists is that will achieve this ‘Goldilocks scenario’ of low inflation and unemployment alongside moderately solid economic growth.

But if the dual mandate is achieved it won’t be down to the interest-rate policies of the Fed. As I have argued several times before, monetary policy supposedly manages ‘aggregate demand’ in an economy by making it more or less expensive to borrow to spend (whether as consumption or investment). But the experience of the recent inflationary spike since the end of the pandemic slump in 2020 is clear. Inflation went up because of weakened and blocked supply chains and the slow recovery in manufacturing production, not because of ‘excessive demand’ caused by either a government spending binge or ‘excessive’ wage rises or both. And inflation started to subside as soon as the energy and food shortages and prices ebbed, global supply chain blockages were reduced and production began to pick up. Monetary policy had little to do with these movements.

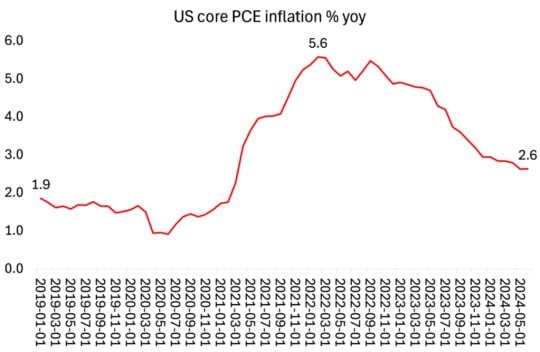

And contrary to the hopes and expectations of Fed chair Jay Powell and all the mainstream economists, there are trends in the US economy that suggest the dual mandate is unlikely to be achieved. First, inflation remains ‘sticky’ i.e. well above the target 2% annual rate. The Fed likes to measure US inflation based on the core personal consumption expenditure (PCE) price index. This is a convoluted measure that excludes production prices and energy and food prices – hardly an accurate measure of price rises for the majority of Americans! Even so, the core PCE currently stands at 2.6%, down from a peak of 5.6% in 2022, but still well above 2% and the rate in 2019.

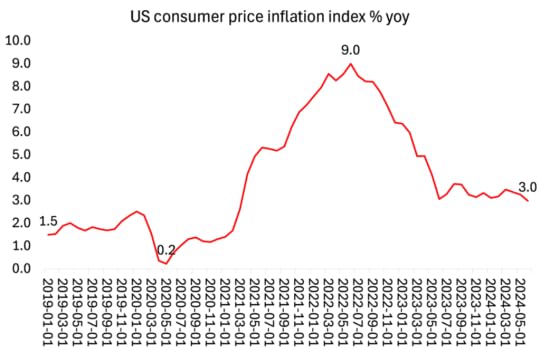

The overall consumer price inflation rate is much higher than the Fed’s measure. It currently stands at 3.0%, down from a peak of 9% in 2002, but still one full percentage point above the Fed’s illusive target and double the rate in 2019.

And as you can see, the CPI rate seems to be sticking around 3% with little sign of a further reduction despite the optimistic talk of the mainstream economists. The reasons are clear to me. First, as I have argued before and above, inflation has been driven not by ‘excessive demand’ but by weak supply ie low productivity growth and high commodity prices. Second, the prices of many products in the US economy have been hiked sharply over the past two years that it appears do not seem to affect the official price measures.

In particular, these include housing costs, health and motor car insurance, which have risen sharply. As a recent FT article admitted: “Both are partly a product of pandemic supply shocks — reduced construction and a shortage of vehicle parts — that are still percolating through the supply chain. Indeed, dearer car insurance now is a product of past cost pressures in vehicles. Demand is not the central problem; there is little high rates can do.”

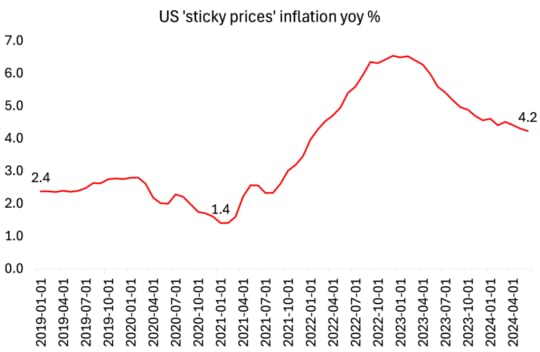

There is also another measure of inflation in the US economy called the Sticky Price Consumer Price Index (SCPI), which is calculated from a subset of goods and services included in the CPI that change price relatively infrequently -so not affected much by changes in demand. This index again shows a much higher rate of inflation, currently at 4.2% yoy, three times higher than in early 2021.

This measure suggests that inflation has become embedded in the economy with firms using any opportunity to hike prices but taking no opportunity to lower them. Don’t forget that American households have suffered an average 20% rise in the prices of goods and services that they buy over the last three years -so all that current slowing inflation means is that prices are still up hugely, but now not rising as fast. This inflation of prices has eaten into the real incomes of most Americans over the last few years so that even if they all have jobs (mostly low-paid services jobs), living standards have got backwards.

So contrary to the Fed’s talk, the ‘war against inflation’ has not been won. As a result, the Fed has still not cut its policy rate. But in not doing so, the Fed’s high policy rate keeps borrowing rates high and so hits the profits of particularly small companies that often must borrow to invest and employ; as well as credit card and mortgage rates for households.

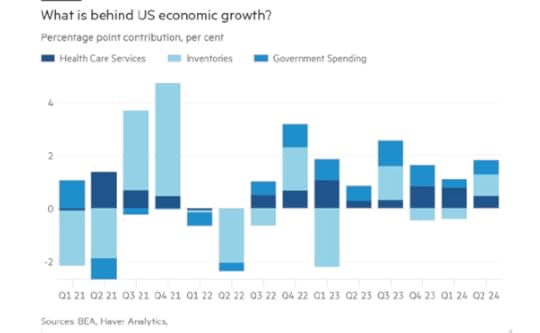

That raises the question of whether the US economy really is motoring along and so will avoid any downturn caused by the squeeze on profits from high interest rates. Much has been made of the recent advanced estimate of US annualized real GDP growth in the second quarter of this year at 2.8%, up from 1.4% in the first quarter. But this headline figure hides a lot of holes.

First, it is an ‘annualised’ rate, meaning that the quarterly increase in real GDP in Q2 was actually only 0.7%. Second, the headline rate includes major contributions from: healthcare services (0.45 percentage point); inventories (0.82 percentage point); and government spending (0.53 percentage point). Healthcare services are really a measure of the rising cost of health insurance not better healthcare and that cost has rocketed in the last three years. Inventories means stocks of goods unsold, in other words, output without sale; and government spending was mainly for arms manufacturing, hardly a productive contribution.

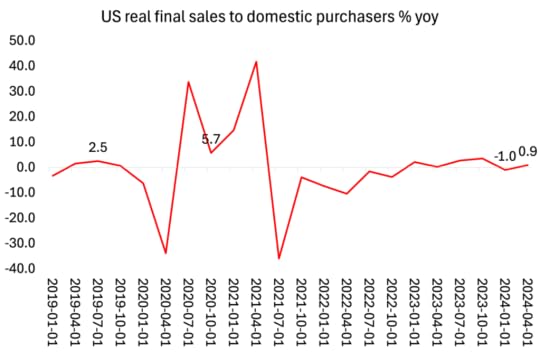

If you strip all these components out and look at what is called ‘real final sales to private domestic purchasers’, a better measure of US economic activity, then there was no improvement over the weak first quarter. Indeed, growth in real final sales in the first half of this year has been zero compared to around 2% over the whole of 2023.

And sales to consumers have been better than real personal income growth. On average, American households, after two years of reductions in real incomes, are reaping only a very small rise now. Real personal disposable income (that’s income going to people after inflation and taxes are taken into account) rose at only a 1% annualised rate, slower than in the first quarter.

No wonder US consumer sentiment fell to its lowest level in eight months. The University of Michigan’s consumer sentiment index registered a final reading of 66.4 in July, the lowest since November. The mainstream economists, believing that consumer spending and incomes are booming, have been puzzled by this, calling it a ‘vibecession’. American households don’t seem to realise that they are doing very well! But “high prices continue to drag down attitudes, particularly for those with lower incomes,” said Joanne Hsu, the Michigan survey’s director.

That’s the consumer front. On the production front, it is not looking much better. The US corporate earnings season has commenced and there has been bad news across the board, particularly with the mega tech and social media companies that dominate the US stock market and take the bulk of profits in the corporate sector.

Four of the so-called Magnificent Seven technology stocks that have powered the US market rally for the past nine months ended the week in ‘correction territory’ for their stock prices, having fallen by more than 10 per cent from recent peaks. Another two — Microsoft and Amazon — are close to the double-digit falls that define a correction. From a Magnificent Seven to a Fractured Five!

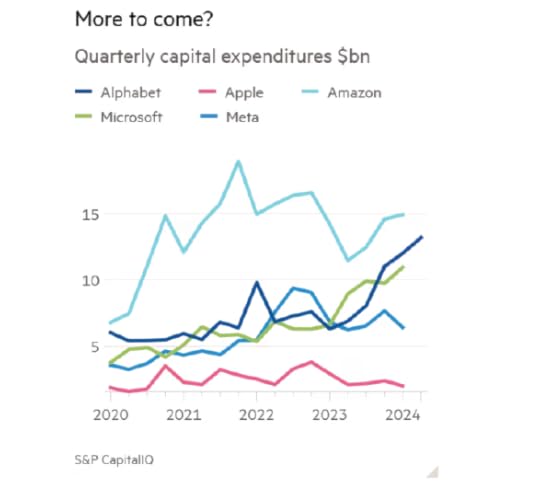

Big Tech has committed its fortunes to expected huge profits from AI. They have launched unprecedented levels of investment, and thus become the main driver of business investment in the US economy. Microsoft has said “we expect capital expenditures to increase materially” this year and that “near-term AI demand is a bit higher than our available capacity”. Amazon says strong demand for cloud services and AI means it will “meaningfully increase” capital expenditures. Meta says AI is driving higher investment both this year and into 2025. But doubts about the quick realisation of higher profits from AI are beginning to emerge and if Big Tech starts reducing its spending than that will reverberate through the corporate economy. There is more talk of ‘tail risk’ for the stock market.

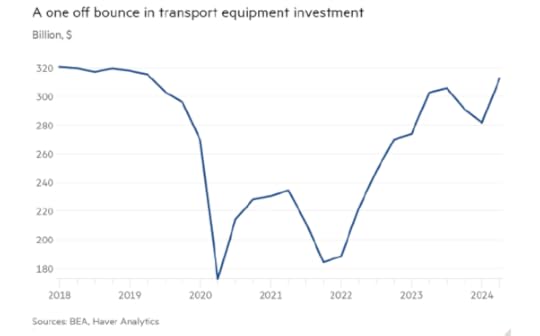

Also share prices in UPS, the delivery company often seen as a bellwether for the broader economy, dropped 12 per cent after UPS scaled back its forecasts for the rest of the year. Since the end of the pandemic there has been a huge rise in investment in transport equipment to handle the increase in global output. But that seems to be coming to an end.

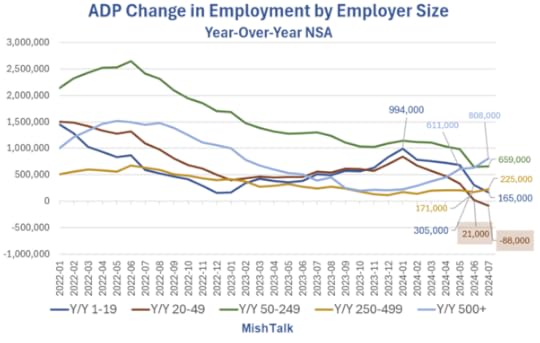

As for employment, again the overall picture is one of weakening employment growth and rising unemployment. ADP data shows year-over-year payroll growth is a negative 88,000 for small corporations employing 20-49 workers. And tends are negative in all but very large corporations.

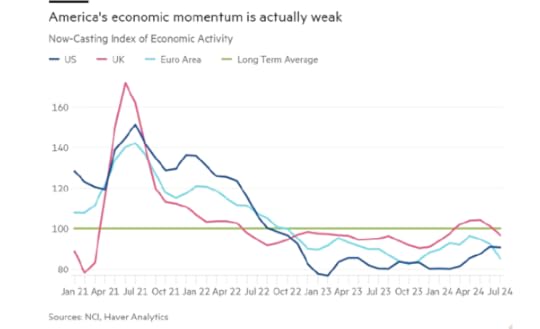

Indeed, the forward momentum in economic activity is weakening.

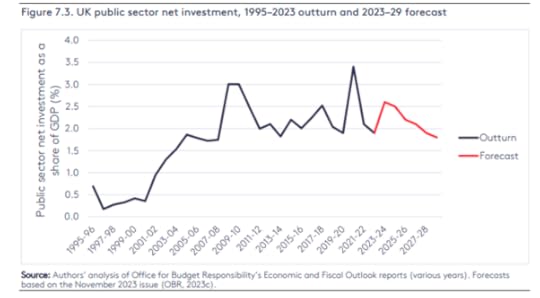

The reality is that the US economy may be the best performing in the top G7 economies, but it is not racing along. Even so, the situation in Europe and Japan is much worse – something I shall return to in a future post. The UK is so bad that the Bank of England has decided to cut its policy rate now. UK headline inflation has fallen sharply to 2%, but only because the UK economy is stagnating.

To sum up. The Federal Reserve will almost certainly start to cut its policy rate at its September meeting – and it has indicated just that. But that’s because it has no choice if it is avoid stagnation or even recession in the economy, like the UK’s Bank of England already faces So the Fed will have to live with failing to achieve its 2% inflation target. And American households will face yet more inflation in the shops and in key services.

July 27, 2024

Venezuela: the end game?

Venezuela has a general election tomorrow. This promises to be a decisive election that could see the end of the so-called Chavista governments, first under Hugo Chávez from 1998-2013 (on his death) and then under Nicolas Maduro for the last eleven years. Maduro is seeking a third six-year term.

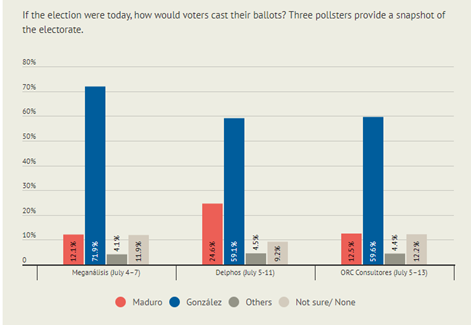

There are more than 21 million registered voters in Venezuela, including about 17 million people currently living in the country. Current opinion polls indicate that Maduro will be defeated by the pro-US, pro-business opposition candidate Edmundo Gonzalez. Gonzalez is standing because the real leader of the opposition, Maria Corina Machado, is banned by the Maduro government from standing. Both sides are drawing large crowds of support in campaigning. But polls suggest that this could be the end of the Maduro presidency.

Over the decades since 1998, many on the left have understandably backed Chavez and Maduro against the unceasing attempts of the economic elite within Venezuela and withot by US imperialism to oust them. But as the Venezuelan economy has been brought to its knees, large sections of working people who fought to defeat several coup attempts against Chavez and Maduro appear to have lost confidence in the government. Venezuela’s population has been depleted (with seven million, mostly skilled better-off citizens, leaving the country in the last two decades). The working class is now divided, with sections even prepared to vote for the opposition in the hope of ‘change’.

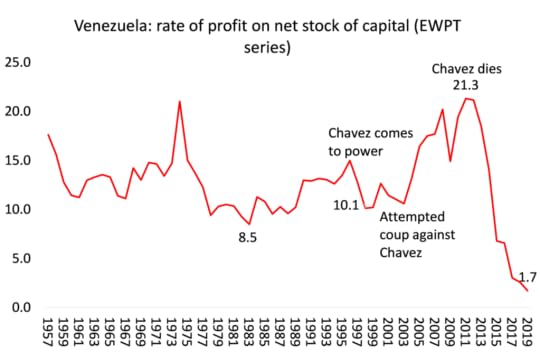

How did the great hopes of Chavez’s government come to this? In my view, there are two main factors: US imperialism and its sanctions, along with the machinations of the Venezuelan elite; but also the failure of Chavez and Maduro to end the economic rule of capital in Venezuela.

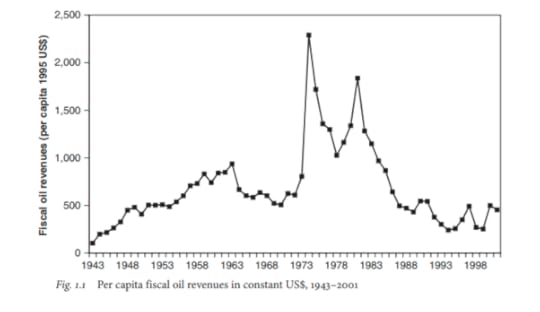

In 1970 Venezuela had become the richest country in the region and one of the 20 richest countries in the world, ahead of countries like Greece, Israel, and Spain. But this wealth was almost entirely based on one commodity, oil; Venezuela has some of the largest proved reserves in the world. Then came the downturn in the world economy during the 1970s. Between 1978 and 2001, Venezuela’s economy went sharply in reverse, with non-oil GDP declining by almost 19 percent and oil GDP by an astonishing 65 percent. Government revenues plummeted.

A succession of corrupt pro-capitalist governments came and went. There was a growing movement to end this nightmare among sections of the military, intelligentsia and the organized working class. This eventually led to Hugo Chavez gaining power and attempting to switch the country’s resources from the rich towards the poor.

To begin with, as oil prices rose, Chávez presided over years of robust and sustained economic growth in Venezuela, averaging 4.5 percent a year from 2005-2013. Chávez reasserted state control over the state oil company, PDVSA, and directed enhanced oil revenues to the poor, with Venezuela’s social spending doubling between 1998 and 2011. The government used price controls, direct state provisioning through newly created missions and subsidies into health care, education, social services, housing, utilities, basic goods and other economic sectors.

This helped bring about major social gains. Poverty was nearly halved between 2003 and 2011, with extreme poverty cut by 71 percent. School enrollments rose and university enrollments more than doubled, with unemployment cut in half. Child malnutrition was cut by nearly 40 percent, and Venezuela’s pension rolls quadrupled. Inequality declined steeply, with Venezuela’s gini coefficient of inequality dropping a full tenth of a point, from 0.5 to 0.4 from the early to late 2000s. By 2012 (and through 2015), Venezuela had become Latin America’s most equal country.

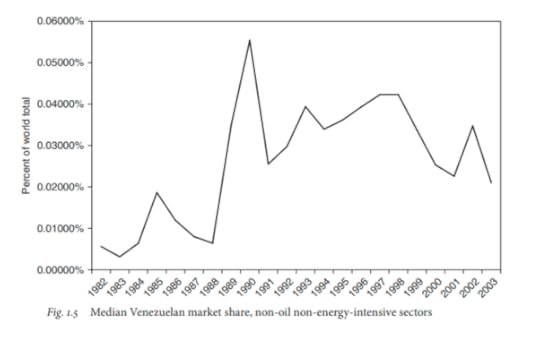

But Chavez’s programme was one of redistribution of the value gained by Venezuela’s non-oil capitalist sector, the oil industry and multi-nationals. The ownership and production of the non-oil sectors was not brought under state control to plan the economy. Víctor Álvarez, an economist who was part of the government under Chávez, notes that private industry actually increased under Chávez, despite the government nationalizing a number of important industries. Most important, Chávez failed to wean Venezuela from oil dependency, with the percentage of government export revenues derived from oil increasing from 67 percent in 1998 to 96 percent in 2016.

This was nothing new. Venezuela was not able either before or after Chavez to change this one-trick pony economy. This was not the case to some extent in other energy-rich economies like Mexico and Indonesia. Their non-oil export sectors grew somewhat to compensate for any decline of oil export revenues, even if those sectors were dominated by multi-nationals from the US and Japan. Venezuela’s growth rate of non-oil exports is just one-sixth that of Mexico and one-fourth that of Indonesia. Venezuela’s participation in non-energy-intensive sectors has not increased since the early 1990s.

Between 1999 and 2012 the state had an income of $383bn from oil, due not only to the improvement in prices, but also to the increase in the oil royalties paid by the transnationals. However, this income was not used transform the productive sectors of the economy. There was no plan for investment and growth. Venezuelan capital was allowed to get on with it – or not as the case may be. Indeed, the share of non-oil industry in GDP fell from 18% of GDP in 1998 to 14% in 2012.

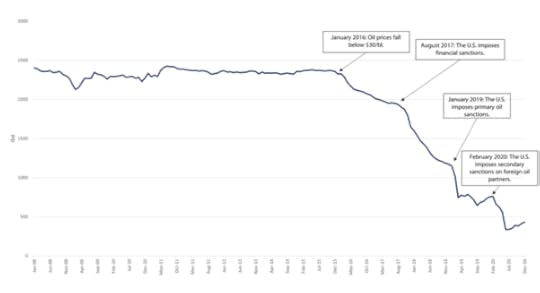

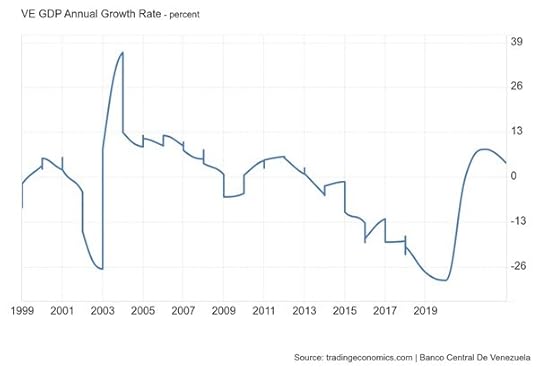

The good years came to an end when oil prices started to fall. Oil exports fell by $2,200 per capita from 2012 to 2016, of which $1,500 was due to the decline in oil prices. This situation worsened just as Maduro took over in 2014 when oil prices declined by nearly 75% in a matter of months. Although oil prices began recovering in 2017 and output stabilized in other oil producers, it did not in Venezuela – because that was the year that sanctions by the US and other countries were imposed.

The coming to power of Chavez had threatened capitalist interests in Venezuela and blocked US multi-national investment, unlike in Mexico. So the US aim was to bring down the Chavista regime. The US barred oil purchases, froze government bank accounts, prohibited the country from issuing new debt, and seized tankers bound for Venezuela. This decimated Venezuela’s oil export and stopped the government from re-investing in oil technology.

The US did not stop there. They decided to ‘recognize’ a so-called interim government in opposition to the Maduro government and transferred to it control over Venezuela’s offshore assets. Doing so blocked Venezuela from accessing its US refineries, or obtaining financing from multilateral organizations, or even using most of its international reserves. Then the US attempted to foment a military coup and tried what turned out to be a tragicomic sea invasion by US mercenaries.

In this period, Venezuela saw a 65 percent decline in the number of correspondent banks that were willing to process international transactions and a 99 percent decline in the value of those transactions between 2011 and 2019. This meant that Venezuela’s private sector was less able to engage in international trade or payments.

In many ways, Venezuela has been in a worse position than Cuba. The attempted destruction of the Cuban economy comes from outside, from the US. But there are no serious opposition forces inside. But Maduro has faced waves of opposition intransigence and violence, often inspired by US agencies. Maduro has responded with repression, directed not only against the elites in the opposition, but often also against the popular sectors that formed Chávez’s core support base.

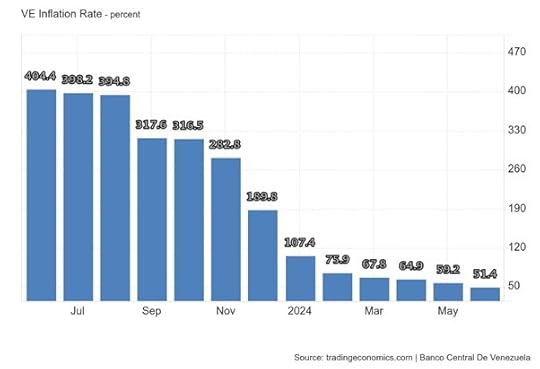

The Maduro government started to rack up huge foreign debts to try and sustain living standards. Venezuela is now the world’s most indebted country. No country has a larger public external debt as a share of GDP or of exports or faces higher debt service as a share of exports. From 2014 to 2021, Venezuela suffered one of the worst economic crises in modern history. The economy contracted by 86 percent. Poverty rose to an estimated 96 percent in 2019. Inflation reached an absurd level of 350,000 percent that same year. In 2018 nearly a third of the population suffered undernourishment. And roughly a quarter of Venezuelans have since fled in an unprecedented migration that now exceeds 7.7 million.

Right-wing pro-capitalist economists tell us that Venezuela shows that ‘socialism’ does not work. But the lesson of the history of Venezuela in the 21st century is not the failure of ‘socialism’, it is the failure to end the control of capital in a weak (an increasingly isolated) capitalist country with apparently only one asset, oil. There was no investment in the people, their skills, no development of new industries and the raising of technology – that was left to the capitalist sector. And there was no involvement of the people through independent organisations from below to check the government’s corruption and direct its policies against US sanctions and the disruption of Venezuela’s elite.

As there was no move to socialist investment in the economy, Venezuelan capitalism was tied only to the profitability of the energy sector, which was in a death spiral after the collapse of oil prices and US sanctions.

The gains for the working class achieved under Chavez have now dissipated. While the majority struggle to survive, many at the top of the Maduro government are as comfortable as the Venezuelan capitalists and their supporters who are trying to bring the government down.

The Maduro government now relies increasingly not on the support of the working class but on the armed forces. And the government looks after them well. The military can buy in exclusive markets (for example, on military bases), have privileged access to loans and purchases of cars and departments, and receive substantial salary increases. They have also won lucrative contracts, exploiting exchange controls and subsidies, for example, selling cheap gasoline purchased in neighbouring countries with huge profits.

Since the end of the COVID pandemic slump and the consequent huge rise in energy prices Venezuela’s economy has improved slightly. The Council on Foreign Relations reports economic growth of 8 percent in 2022, 4 percent in 2023, and estimates that it will be 4.5 percent this year.

And the rise in energy prices after the pandemic prompted the US to offer a deal to Maduro to allow ‘fair’ elections in return for the relative easing of US sanctions. As a result, inflation has dropped to a still very high 55%.

But this small improvement probably comes too late and too little to avoid electoral defeat for Maduro. Maduro currently faces drug trafficking and corruption charges in the US and is under investigation for crimes against humanity by the International Criminal Court. If the opposition does clinch victory, a transition period of six months is likely to include an intense negotiation around amnesty for Maduro and members of his government, which people say he is certain to require ahead of any potential handover.

The election result is still unclear and what happens afterwards even more so. Despite the state of the economy and the conditions for working people, there is still a large body of latent support for the Chavista legacy, but this election could be the end game for that, bringing a return to the direct rule of a neo-liberal pro-capitalist government backed by US imperialism – and all that attains for Venezuela’s distressed people.

July 23, 2024

China’s Third Plenum

The Third Plenum of the Communist Party of China ended last week. The Third Plenum is a meeting of China’s Communist Party Central Committee composed of 364 members which discusses China’s economic policy for the next several years. As China is a one-party state, in effect this sets out the policies of the government and, in particular, that of President Xi.

What did we learn from the Third Plenum about China’s economic policies? Not very much that we did not already know. According to the state media release, the Plenum agreed that economic policy should concentrate on achieving a new round of “scientific and technological revolution and industrial transformation,” Chinese-style. In the next decade, “education, science and technology, and talents are the basic and strategic support for China’s modernization.”

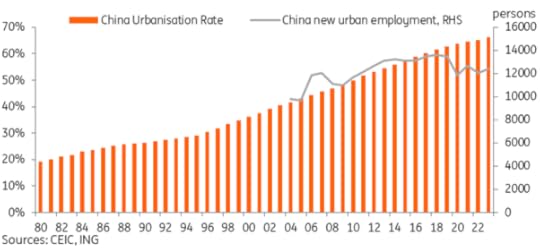

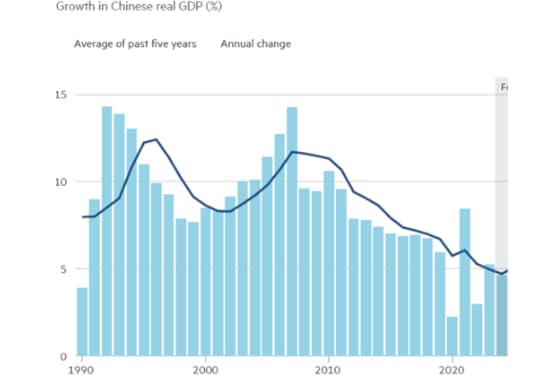

So it appears that the CPC leaders are looking to sustain economic growth and meet all their proclaimed social objectives through what they have called ‘quality growth’. The expansion of the economy mainly through using plentiful labour from the countryside coming into the cities to work in manufacturing, property development and infrastructure is over. It has been over for some time. Urbanisation is slowing.

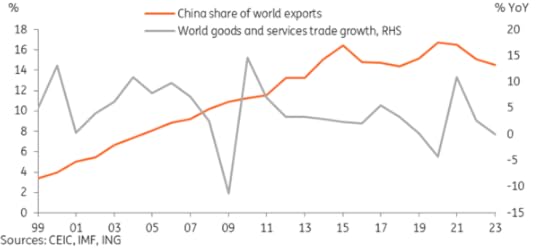

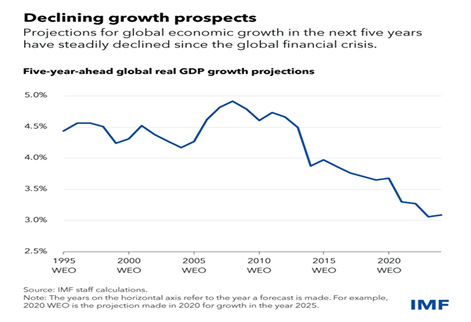

Instead, the Chinese economy has rocketed upwards mainly from a massive increase in productive investment in industry and export-oriented sectors. But that too has reached somewhat of a peak since the Great Recession of 2008-9. The global economic slowdown and stagnation in the major economies since then – what I have called a Long Depression – have also affected the rate of economic growth in China. World trade growth has stagnated and so has China’s share.

China’s real GDP growth has slowed since the Great Recession, although the economy is still expanding at around 5% a year, more than twice as fast as the US economy, the best performing of the top seven capitalist economies.

But other causes of slowing growth include the relative exhaustion of labour from the rural areas and also the expansion of unproductive investment in real estate, which eventually ended in a property bust that is still being managed. As I have argued in many previous posts, this was the result of the huge policy mistake that the Chinese government made back in the 1990s in trying to meet the housing needs of a fast-urbanising population through the private sector: ie. homes to buy, financed by mortgages and built by private developers. This housing model used in the West triggered the global financial crash in 2008 and eventually led to a similar property slump in China.

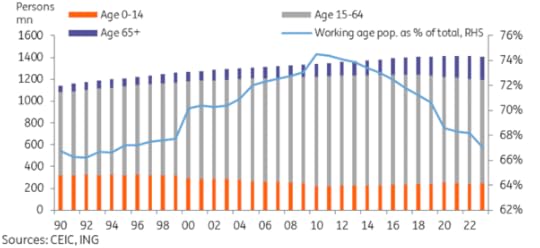

But the key issue for the Third Plenum is the ‘demographic challenge’. China’s population, like many others, is set to fall over the next generation and its working age population will also drop.

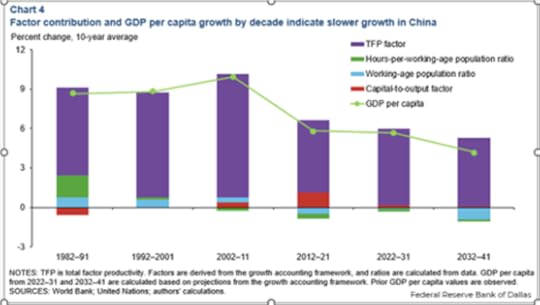

Economic growth and further improvements in living standards will increasingly depend on raising the productivity of the labour force. I have argued in previous posts that this is perfectly possible to achieve.

The Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas shows that China’s ‘total factor productivity’ (which is a crude measure of innovation) is growing at 6% a year, while it has been falling in the US. Slower growth but still much faster than G7 economic growth and based on technological success.

But Western media and mainstream economists continue to argue that China’s economy is in deep trouble. Here is the assessment of the UK’s Financial Times:

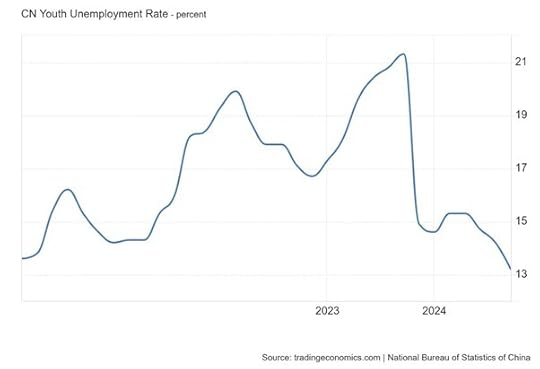

“China’s growth is too slow to provide jobs for legions of unemployed young people. A three-year property slump is hammering personal wealth. Trillions of US dollars in local government debt are choking China’s investment engines. A rapidly ageing society is adding to healthcare and pension burdens. The country has continued to flirt with deflation.”

I could deal with these issues one by one. But I have already done so in many previous posts. Suffice it to say that the size of youth unemployment is a serious challenge. There is a sharp mismatch between young graduate students looking for well-paid high -tech jobs, while available employment is still concentrated in lower-paid less skilled work. This is a problem in many economies, including the advanced capitalist economies. The solution, it seems to me, is in the expansion of high-tech sectors, but also in re-training for other jobs.

2) the property slump has been severe. It is no bad thing, however, for property prices to fall sharply so that housing becomes more affordable. The solution from here must be an expansion of public housing, not more private development.

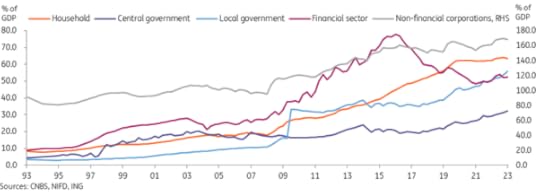

3) as for the debt issue, it’s true that China leverage ratios have surged in past decades, but they are manageable, especially as most of the debt is concentrated in local government sectors and so can be bailed out by central government. And China has a state banking system, state-owned companies and massive FX reserves to cover any losses.

China: debt to GDP

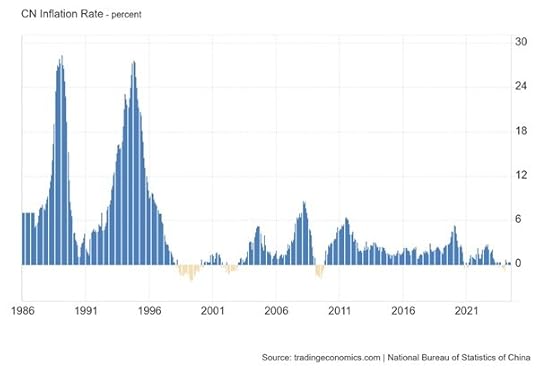

4) Apparently falling consumer prices in China is a bad thing, according to the FT. But is it so bad that basic purchases get cheaper? Is it better to suffer the inflationary spike that consumed Western economies and households in the last two years?

The other critique continually hammered by the likes of the FT and Western economists is that: “Beijing pledged to reorientate its growth model away from an over-reliance on investment and exports towards household consumption. This, western governments have long hoped, would help reduce China’s huge trade surpluses and invigorate global demand.” But “Not only has China failed to deliver on its rebalancing pledges, it has actually regressed.” The FT is upset that “The plenum communique does not pledge to boost consumer spending or rebalance the economy away from investment and exports.”

The FT then goes on to blame China for the US tariff war likely to be accelerated if Donald Trump rewins the presidency in 2025. “Xi and his politburo should realise that China’s trade imbalances are becoming an ever more incendiary issue. Its monthly trade surplus reached an all-time record in June. The resurgence of Donald Trump, who imposed hefty tariffs on Chinese imports during his term as US president, should give real pause for thought.” China is apparently at fault for the trade war, not US government attempts to curb Chinese export success and technology advances.

Once again, the Western media and economists argue for a ‘rebalancing’ by which they mean a switch to a consumer-led, private sector-led economy from the current investment-led, export oriented, state directed one. “The Chinese economy is foundering,” said Eswar Prasad, professor of trade policy at Cornell University and former head of the International Monetary Fund’s China division. “More stimulus to pep up spending and economic overhauls to revive private-sector confidence in China are urgently needed”, he said.

But for me, trying to boost consumer spending and expand the private sector are just not what the Third Plenum should aim for. Actually, the Third Plenum release reminds us that China still has planning, not the centralized one of the Soviet Union, but ‘indicative planning’ with targets set for many sectors. The release said that “We must summarize and evaluate the implementation of the “14th Five-Year Plan” and do a good job in the early planning of the “15th Five-Year Plan”.”

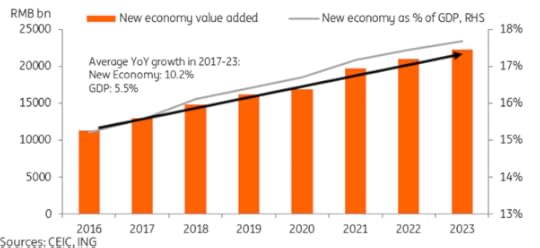

China is fast developing a ‘new economy’ based on high value-added tech sectors. These sectors have significantly outpaced headline GDP growth in recent years. Between 2017 and 2023, the new economy grew by an average of 10.2% per year, far faster than the 5.5% average overall GDP growth.

As a piece in the Asian Times put it: “A common narrative bandied about by the Western business press is that China’s subsidized industries destroy shareholder value because they are not profitable – from residential property to high-speed rail to electric vehicles to solar panels (the subject of the most recent The Economist ‘meltdown’). But what China wants from BYD and Jinko Solar (and the US from Tesla and First Solar) should be affordable EVs and solar panels, not trillion-dollar market-cap stocks. In fact, mega-cap valuations indicate that something has gone seriously awry. Do we really want tech billionaires or do we really want tech? Value is not being destroyed; it’s accruing to consumers ins lower prices, higher quality and/or more innovative products and services.”

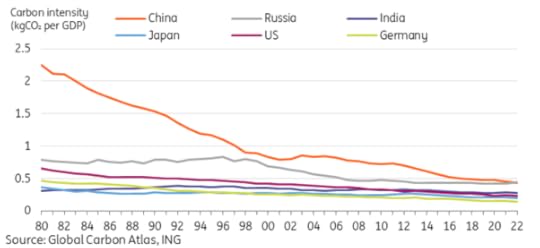

This is very visible in environmental investment. China’s carbon intensity has dropped at an unprecedented pace.

As the Asian Times writer put it: “what is economic success, what is value creation? Maybe, just maybe, it’s the approach that delivers the most tangible improvements in people’s lives, instead of trillion-dollar companies and billionaire CEOs.”

July 21, 2024

Crowd strikes out

The massive tech failure that caused chaos around the world raises important questions about the ownership and control of our digital world. The relatively unknown, cyber-security firm CrowdStrike admitted that the problem was caused by an update to its antivirus software, which was designed to protect Microsoft Windows devices from malicious attacks.

The outage was caused by just a tiny software update from CrowdStrike put into Microsoft programs bringing them down globally My ‘techie’ programmer friends tell me that it looks like two very basic coding errors that should have been spotted and tested before being ‘forced’ onto Microsoft operating systems.

CrowdStrike is a US firm based in Austin, Texas, listed on the US stock exchange and employs 8500 people with 24,000 clients. As a provider of cyber-security services, it tends to get called in to deal with the aftermath of hack attacks. But it also provides protection from viruses and cyber attacks – but not apparently from its own programs.

The failure hit banking and healthcare services badly with over 8.5 million machines using Microsoft. Airlines and airport systems failed, leading to 3300 cancelled flights. Many companies’ payroll systems have been affected, meaning that thousands of employees will not get their monthly wages on time. The outage could cost billions of dollars worldwide and take weeks to resolve because computers will require a manual reboot in ‘safe mode’, causing a massive headache for IT departments everywhere

What this outage reveals is the massive dominance of both Microsoft and CrowdStrike in computer software and cyber security. Microsoft Windows has about 72% of the global market share of operating systems, while CrowdStrike’s market share in the ‘endpoint protection’ security category is 24%. So the world’s information, payments, transport and communications are dependent on the decisions and operations of just a few privately-owned ‘for (massive) profit’ companies. As one campaigner put it: “Today’s massive global Microsoft outage is the result of a software monopoly that has become a single point of failure for too much of the global economy”.

One problem arising from this is that there is no diversification of operating systems. Again, my techie friends reckon that Microsoft Windows is a very poor operating system vulnerable to bugs and other coding errors, unlike other systems, including free ‘open source’ ones. “For decades, Microsoft’s pursuit of a vendor lock-in strategy has prevented the public and private sectors from diversifying their IT capabilities. From airports to hospitals to 911 call centers to financial systems, millions today are feeling the consequences of the greed and ego of one of the most egregious offenders in Big Tech. When just three companies—Microsoft, Amazon, and Google—dominate the market for cloud computing, one minor incident can have global ramifications.”

What is the answer to this? The techies say we need more back-up systems, say at least two independent providers for their core operations, or at least ensure that no single provider accounts for more than about two-thirds of their critical IT infrastructure. Then if one provider has a catastrophic failure, the other can keep things running. But it is one thing to have back-up systems, it is another to diversify into different operating systems that risk being not compatible with each other. Again, my techie friends reckon that many bugs and outages are due to different systems operating in one company. That means there is no one ‘beginning to end’ view. As a result, if things go wrong in one part of the business tech-wise, the tech teams cannot see why from the other end of the business process. Too many cooks have spoilt the broth.

Is more regulation of the big tech companies the answer? I think not. Regulation of capitalist ‘for profit’ companies by government regulatory agencies has been a proven failure in just about every sector: finance, utilities, transport, communications etc. These companies just ride roughshod through regulations, pay their fines if found out,but then carry on ‘business as usual’.

What about breaking up the big tech monopolies? This is a common cry from some: “it is long overdue that Microsoft and other Big Tech monopolies are broken up—for good. Not only are these monopolies too big to care, they’re too big to manage. And despite being too big to fail, they have failed us. Time and time again. Now, it’s time for a reckoning. We can’t continue to let Microsoft’s executives downplay their role in making all of us more vulnerable.”

But anti-trust measures that break up large companies have done little in the past. The major economies are even more dominated by large companies than they were one hundred years ago. Take the US government break-up of Standard Oil in 1911, when it controlled over 90% of the oil sector in the US. Did that break-up lead to the creation of lots of small ‘manageable’ oil companies globally that worked in the interests of society? No, because in many industries economies of scale must operate to raise productivity and for capitalist firms to maximise profitability. Now one hundred years after the Standard Oil break-up, we have even larger multi-national energy companies controlling fossil fuel investment and energy prices.

It’s the same debate with digital banking. Just the day before the CrowdStrike global outage, the Bank of England reported that its banking transactions service CHAPS had broken down, delaying many time-sensitive payments. It seems that the international SWIFT cross-border payments system had an outage for several hours. And indeed, there has been a litany of banking system failures at ATMs and in digital transactions over the last 20 years.

The major banks worldwide spend huge amounts of money on speculating in the stock and bond markets, but do not spend nearly enough to ensure that basic banking services for the public (both households and small companies) work seamlessly. This is sometimes called ‘tech debt’. It has led some to argue that we need to stop full digitilisation of money transactions.

Cash remains a safe fallback when digital payments break down. The UK’s GMB Union said “cash is a vital part of how our communities operate”. When you take cash out of the system, people have nothing to fall back on, impacting on how they do the everyday basics.” Cash, it is argued, also provides more control over people’s money. Martin Quinn, campaign director for the PCA, said using cash allowed for anonymity. “I don’t want my data sold on, and I don’t want banks, credit card companies and even online retailers to know every facet of my life,” he said. Budgeting by using cash is also easier for some”.

And the example of what the Indian government did in 2016 is a lesson on this. The Indian government abruptly wiped out most of the nation’s paper currency in hopes of ending ‘black money’ and curbing corruption. But a November 2017 study of 3,000 regulated agricultural markets for 35 major agricultural commodities, conducted during the three months immediately following demonetization, concluded that eliminating the high-currency notes had reduced the value of domestic agricultural trade by more than 15 percent in the short run, settling at 7 percent reduction three months late. In a largely ‘informal economy’, where the most vulnerable people still have no access to digital payments, this demonetization was a draconian measure that did a lot of damage to the poorest people in India.

But again, it would be wrong to conclude that we must go back to cash. Cash under the mattress may protect against the prying eyes of the authorities, but it would remain an inefficient method of money transactions and, as we know, an attraction to criminality. Of course, violent robbery of personal and corporate cash (as we see in action films) has now been replaced by the silent extraction of people’s savings and company accounts by cyber scams. But that does not mean digitalization of money should be reversed.

The question really centres on who owns and controls our digital world. The high concentration of that digital power is yet another reason for the replacement of capitalist corporations by public companies democratically controlled by popular bodies and the tech workers in them. We need to bring into public ownership the Magnificent Seven of social media and tech companies currently led and controlled by multi-billionaires who decide what to spend and where. Then the huge waste of resources on tech projects designed just to make money and not to deliver useful and safe systems beneficial to people’s lives could be reduced dramatically. Human error would not disappear, but the organisation and control of our increasingly digital world could be directed towards social needs not private profit.

July 17, 2024

Catching up and falling behind

Brazilian Marxist economists Adalmir Antonio Marquetti, Alessandro Miebach and Henrique Morrone have produced an important and insightful book on global capitalist development, with an innovative new way of measuring the progress for the majority of humanity in the so-called Global South in ‘catching up’ on living standards with the ‘Global North’.

In this book Marquetti et al argue that unequal development has been a defining characteristic of capitalism. “Throughout history, countries and regions have exhibited differences in labor productivity growth – a key determinant in poverty reduction and development – and although some nations may catch up with the productivity levels or well-being of developed economies at times, others fall behind.”

They propose a model of economic development based on technical change, profit rate and capital accumulation, on the one hand, and institutional change, on the other. Together these two factors should be combined to explain the dynamics of catching up or falling behind.

They base their development model on what Duncan Foley called the ‘Marx-bias’ and what Paul Krugman has called ‘capital bias’; namely that in capitalist accumulation there will be a rise in the organic composition of capital (rising mechanization compared to labour input) leading to an increase in the productivity of labour, but also a tendency for the profitability of accumulated capital to fall.

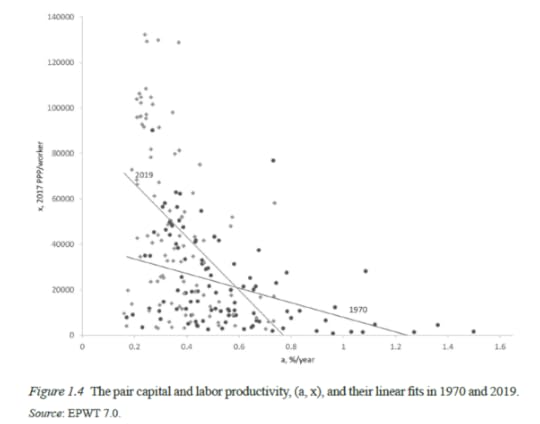

Surprisingly, however, the authors do not use Marx’s specific categories to analyse this development of capitalism globally. They adopt what they call is a model in the ‘classical- Marxian tradition’ (so not actually Marxist), which is composed of two variables: rising labour productivity (defined as output per worker); and falling capital productivity (which is defined as output per unit of capital or fixed assets). The problem with this model is that the Marxist categories of surplus value (s/v) and the organic composition of capital (C/v) are now obscured. Instead, we have labour productivity (v+s)/v) and ‘capital productivity’ (v+s/C)). Cancelling out v+s and we get C/v or Marx’s organic composition of capital.

In Marx’s theory of development, the key variable is the rate of profit. Put in its most general terms, if total assets grow, due to the labour-shedding nature of new technologies, employment grows less (or even falls) than the growth in total assets (C/v rises). Since only labour produces value and surplus value, less surplus value (s/v) is generated relative to total investments. The rate of profit falls and less capital is invested. Thus, the rate of change of the GDP falls.

To me, it seems unnecessary to use their particular measures over Marx’s own categories, which I think provide a clearer picture of capitalist development than this ‘classical-Marxian’ one. At one point, the authors say that “The decrease in capital productivity in the follower country reduces the profit rate and capital accumulation.” But using Marx’s categories should lead you to say the opposite: a falling profit rate will reduce capital accumulation and lower ‘capital productivity’.

Nevertheless, it is these two measures that the authors measure, using the fantastic Extended World Penn Tables that Adalmir Marquetti has perfected over the years from the Penn World Tables. “The dataset we employ is the Extended Penn World Tables version 7.0, EPWT 7.0. It is an extension of the Penn World Tables version 10.0 (Feenstra, Inklaar and Timmer, 2015), associating the variables in the data set with the growth-distribution schedule. The EPWT 7.0 allows us to investigate the relations between economic growth, capital accumulation, income distribution, and technical change in the processes of catching up and falling behind.”

Using these two measures the authors confirm that the ‘Marx-biased’ pattern of technical change of capital-using and labor-saving occurred in 80 countries. The authors then compare their two measures of ‘productivity’ and argue that economies can ‘catch up’ with the leading capitalist economies, with the US at the head, “if accumulation rates are higher in the follower country, leading to a reduction in disparities in labor and capital productivities, the capital-labor ratio, the average real wage, the profit rate, capital accumulation, and social consumption between countries.”

The authors’ model argues that capital productivity will tend to fall as labour productivity rises for all countries. Countries with lower labor productivity tend to exhibit higher capital productivity, while countries with high labor productivity tend to have lower capital productivity.

The ‘follower’ countries (the Global South) will generally have higher profit rates than the ‘leader’ countries (the imperialist Global North) because their capital-labour ratio (in Marxist terminology, the organic composition of capital) is lower. Marx too reckoned that a less developed country has lower ‘labour productivity’ and higher ‘capital productivity’ than the developed one. However, he described it as: “the profitability of capital invested in the colonies … is generally higher there on account of the lower degree of development.”

Not surprisingly, the authors find that the capital-labour ratio and labour productivity have a positive correlation. “For countries with low capital-labor ratios, there exists a concave relationship between these variables. Furthermore, the fitted lines illustrate a movement toward the northeast between 1970 and 2019, indicating that countries have been increasing their capital-labor ratios and labor productivity along the path of economic growth.”

As these countries try to industrialise, the capital-labour ratio will rise and so will the productivity of labour. If the productivity of labour grows faster than in the leader countries, then catching up will take place. However, capital productivity (and more important to me, the profitability of capital accumulation) will tend to decline and this eventually will slow the rise in labour productivity. In a joint work by Guglielmo Carchedi and me, using Marxist categories, we also found that the dominated countries’ profitability starts above that of the imperialist ones because of their lower organic composition of capital BUT also “the dominated countries’ profitability, while persistently higher than in the imperialist countries, falls more than in the imperialist bloc.”

The authors also identify the trajectory of the relative profitability of capital between the leaders and the followers in the process of development and the importance of this in ‘catching up’. “The advantages of lower mechanization in follower countries, implying in smaller labor productivity and higher capital productivity and, therefore a higher profit rate, begin to erode when capital productivity declines more rapidly than labor productivity increases. It indicates that the follower country is gradually losing its backwardness advantage as the disparities in profit rates and incentives for capital accumulation diminish relative to the leading country, potentially jeopardizing the catching-up process.”

What this tells me is that many Global South countries will never ‘bridge the gap’ on labour productivity and thus on living standards because the profitability of capital in the Global South will quickly dissipate compared to the Global North. This is what we found in our study: “Since 1974, the rate of profit of the imperialist (G7) bloc has fallen by 20%, but the higher rate of the dominated bloc has fallen by 32%. This leads to a convergence of the two blocs’ profit rates over time.”

Through their model, the authors were able to analyse the dynamics of the catching up process. They found that “there is no consistent pattern of catching up, about half of the sample fell further behind. The increasing data spread as the labor productivity gap and the distance from the leader expanded suggests that while some countries benefit from their backwardness, others in a similar situation do not take advantage of it. “

Asia was the continent with the highest number of successful countries in catching up, in contrast to Latin America which generally failed to make much progress. Many Eastern European economies also experienced ‘falling behind’ while African countries in general “still suffer from the consequences of decolonization” – or to be more accurate, I think, from previously lengthy and vicious colonization.

What this shows is the importance of institutional factors in the development process – which the authors correctly emphasise. “The interplay between institutional organization, on one side, and how technical change and income distribution affect the profit rates, which is a key determinant of capital accumulation and growth, on the other, is crucial in addressing the fundamental question of how developing countries can initiate and maintain rapid labor productivity growth over time.”

And here we come to an important conclusion in relation to the theory of imperialism in the 21st century. Marx once said that “the country that is more developed industrially only shows to the less developed the image of its own future.” The book’s economic model aligns with Marx’s view that underdeveloped countries should follow the path of technical change set by developed capitalist nations. But as the authors recognize “this trajectory often leads to a decline in the profit rate and, therefore, a decrease in the incentives for investment and capital accumulation. How to circumvent this problem is one of the central issues that a national development plan must face.”

Without strong state intervention, the contradiction between a falling rate of profit and increasing the productivity of labour cannot be overcome. As the authors put it “This issue is observed in many middle-income trap countries. In these cases, state intervention becomes essential, expanding investment even as the profit rate declines, as in China.” Exactly. China’s success in catching up, which so frightens US imperialism now, is down to state-led investment overcoming the impact of falling profitability on capital investment.

In recognizing this, the authors strangely refer to the “Keynesian proposition of socialization of investment, contrasting sharply with the policies pursued by most Latin American countries during neoliberalism, when there was a decline in investments by the state and public enterprises.” Apparently, the authors seem to suggest, if Latin American governments had adopted Keynesian policies, they would not be locked into the so-called ‘middle income trap’ but instead be catching up like China. But China is not a model of Keynesian ‘socialised investment’ (which, by the way, Keynes never promoted in his economic policy prescriptions); instead, it is a model of development based on dominant public ownership of finance and strategic sectors and a national plan for investment and growth (something Keynes vehemently opposed), with capitalist forces relegated to following not controlling.

Indeed, as the authors say: “the aspects discussed above point to the fundamental relevance of state capacities as the primary locus where strategies and conditions for industrialization are conceived and implemented. Unlike the market, which allocates resources primarily to maximize profits without guaranteeing national development, the state remains, in the XXI Century, the political and economic entity capable of intentionally driving industrialization.” And they point out that “China increased its investment rate, even in the face of declining profitability ….. China has demonstrated a capacity to adapt to developmental challenges, suggesting that the labor productivity gap between China and the US, even if at a lower velocity, will continue to decline.”

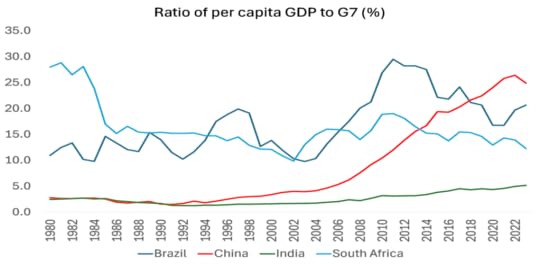

The reality is that in the 21st century, catching up is not happening for nearly all countries and populations of the ‘Global South’. Take the so-called BRICS. Only China is closing the gap on per capita GDP with the imperialist bloc. Over the last 40 years, South Africa has fallen further behind, while Brazil and India have made little progress.

The authors provide us with a startling statistic. In 2019, the average worker in the Central African Republic, one of the poorest countries worldwide, produced 6.8 dollars per day when measured at 2017 purchasing power parity. In India, the average worker produces 50.4 dollars daily, while in the United States, the average worker produces 355.9 dollars. “The rapid expansion of labor productivity is a fundamental step in reducing poverty and improving the well-being of the poor population. However, it has been an enormous challenge for backward nations to achieve high growth rates in labor productivity and catch up with the developed countries.”

July 13, 2024

AHE 2024: value, profit and output

The 2024 conference of the Association of Heterodox Economists (AHE) took place this week in Bristol, England. As its name implies, the AHE brings together economists who consider themselves ‘heterodox’ i.e’ in opposition to the main concepts of mainstream neoclassical economics. Heterodox encompasses Marxian, Post-Keynesian and even Austrian school economics. And this 2024 conference heard keynote speeches and had panel session with speakers from all these sections.

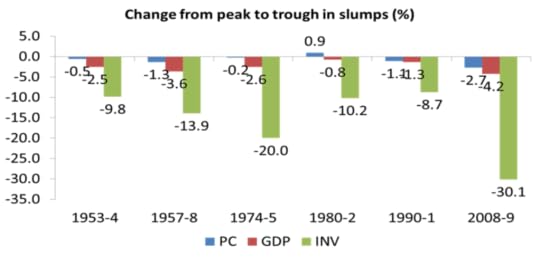

I heard just one of the several keynote sessions, but I’ll come to that later. First, let me cover my own presentation at one of the sessions. The subject of my paper was Profitability and Investment in the 21st century. In the presentation I looked at the basic cause of cycles of boom and slump in modern capitalism, erupting every 8-10 years on average since the early 19th century. I argued that it was changes in capitalist investment or accumulation that was the ‘swing factor’ in booms and slumps, not personal or household consumption, as claimed by mainstream neoclassical and Keynesian economists.

Investment (INV) was the swing factor in slumps (GDP), while consumption hardly changed (PC).

But what causes investment to swing up and down? The post-Keynesian view, as expressed by Michel Kalecki in the 1930s, was that ‘investment calls the tune’, which is correct as far as it goes. Take the macroeconomic identity:

National income = national expenditure

which can be decomposed to:

Wages + profits = investment + consumption

Now simplifying further and assume workers spend all their wages and capitalists invest all their profits, then we end up with:

Profits = Investment

This is the Kalecki equation. But which causal way does this macro identity go? Kalecki argued that investment drives profits (which becomes a residual). The Marxian view is the opposite. Profits come from the exploitation of labour and are used to invest and accumulate. In this case, it’s profits that call the tune. And I presented a batch of empirical studies on the relations between investment and profitability, both from the mainstream and Marxist authors, to support that Marxist causal direction of the Kalecki equation.