Michael Roberts's Blog, page 10

October 3, 2024

Marx’s theory of value: collapse, AI and Petro

A site called Marxism and Collapse (M&C) has conducted a ‘dialogue’ with an AI model called Genesis Zero (GZ) that includes “an expansion and refutation” of Marx’s theory of value. The human voice (M&C) asks questions and leads the AI model (GZ) into discussing the inadequacies of Marx’s value theory and to reach a new, better theory. The Marxism and Collapse website is here and here is their ‘mission statement’.

The main parts of the Genosis Zero-Gustavo Petro discussion on Marx Theory of Value are found here. https://www.scribd.com/document/753007043/Inteligencia-Artificial-Marxista-refuta-la-Teoria-del-Valor-de-Marx-3

(function() { var scribd = document.createElement("script"); scribd.type = "text/javascript"; scribd.async = true; scribd.src = "https://www.scribd.com/javascripts/em... var s = document.getElementsByTagName("script")[0]; s.parentNode.insertBefore(scribd, s); })()

M&C claims that there is a fundamental weakness in Marx’s analysis of the dual character of use value and exchange value in a commodity. The M&C human trainer throughout provides leading questions to get GZ to respond accordingly that there is indeed a weakness in Marx’s theory: namely that it leaves out nature as a source of value. GZ then agrees that we need to amend Marx’s value theory into some ‘general’ theory of value that incorporates the value of ‘nature’.

This debate has been distributed mostly in Latin America and Spain (for example, in the Colombian newspaper Desde Abajo), although the previous English versions are also being widely distributed in several English speaking countries. Even Colombian president Gustavo Petro has entered this dialogue and this has sparked considerable interest.

Petro is not only president but very interested in Marxist theory in relation to the environmental crisis and damage engendered by capitalism globally and in Colombia. And he is keen to find a way of bringing the law of value into measuring the ecological and environmental damage to nature caused by capital. He concludes from the dialogue that we need to amend Marx’s law of value to incorporate nature, which he considers is missing from Marx’s value theory. Petro has been using the ideas expressed in this dialogue in several oral presentations:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GzAIzRyrt30;

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LHMO3ZD6Fsg.

Let us consider this idea that Marx’s value theory is inadequate, incomplete and even false because it does not include nature as a source of value creation. I think this idea is unnecessary and it also weakens Marx’s value theory in its penetrating and compelling critique of capitalism.

Marx starts Capital with this first sentence: “The wealth of those societies in which the capitalist mode of production prevails presents itself as “an immense accumulation of commodities.” Note the use of the word ‘wealth’; not value, but wealth. Marx is saying that all the goods and services that humans use is a measure of wealth. The value of this wealth is a different matter and value only applies in the capitalist mode of production.

In my recent book (with Guglielmo Carchedi) called Capitalism in the 21st century (p10-13), we briefly deal with nature as a source of value. Marx says that nature is a source of USE VALUE – as it is, after all, material stuff. Nature is matter which provide uses for humans (air, water, warmth, light, shelter etc) without the intervention of human labour power. BUT while nature may have use value but it does not have value under the capitalist mode of production. Value is created when nature is modified by human labour power to create a commodity owned by capital that can be sold (hopefully at a profit) on the market. The environmental destruction of the forests by capitalist production (fossil exploration,mining,logging and clearance etc) means a loss of the ‘wealth’ of use values, but it does not mean a loss of value (exchange value) for capital. As socialists we want to consider the impact on nature and the environment, but capital is not interested unless labour power is exerted on nature to create new use values that can be sold on the market.

So it is not necessary under capitalism to value nature. And as Marx’s law of value only applies to the capitalist mode of production, then it is not necessary to ‘correct’ Marx’s law. Indeed, one of the features of the dual nature of value in a commodity in capitalist production is the contradiction between use values (humanity’s needs and nature’s wealth) and exchange value (the commoditisation of human labour and nature into products for sale for profit). This contradiction would be ended under socialism/communism where production would be direct to the consumer and for social use values (or wealth) alone. There would be no commodities, values and prices and thus human labour would be in harmony with nature. So there would be no law of value and so need to ‘generalise’ or amend it.

Nevertheless, the M&C human in the dialogue wants to extend Marx’s theory of value to include nature. So he/she has got the GZ AI model to develop some vague ‘generalised’ law of value.

Marx’s formula for value in commodities is made up of: c (the value of machines and raw materials used up in production) + v (the share of new value created in production going to human labour) + s (the share of the new value appropriated by capital). Thus total value = c+v+s. According to M&C, this is inadequate and so GZ obliges with an extended formula for total value of a commodity that includes the contribution of nature (n). It presents initially this formula as c+v+s+n.

But how do you measure n?

Not in human labour hours because the extended theory says that no human labour is involved. What about In physical units of trees, animals, rivers etc? That makes no sense as Marx’s formula is measured in labour hours. Combining hours with physical units is like measuring apples with pears. Perhaps n could be measured in monetary terms ie rents for land. But rent is a part of surplus value in Marxist theory and is already accounted for in s, so there is no need for n. Maybe n could be measured as a stock of physical assets used up in production, but then raw materials are already included in c in Marx’s value theory. So this extension just does not add up.

Nevertheless, the dialogue moves on. M&C asks GZ to join him/her in a “combined attack’ on Marx’s value theory and again the AI model obliges like a trained puppet. At all times, the AI model always agrees with the human’s questions (actually more like statements); it never disagrees. According to M&C and obligingly agreed by the GZ AI model, a proper theory of value should not be based on human labour alone, but include forests, animals (animal labour) and not just on hours of ‘abstract’ human labour time but also ‘concrete labour’ (specific human and animal skills).

The M&C human and the GZ AI now come up with a more sophisticated formula for including nature in total value. Total value is now made up of:

Human labour time (say 300); plus some extra value from special ‘concrete’ labour including ‘animal labour’ (bees or horses at work (say 75); plus nature (raw materials (say 300); plus some specific concrete ‘better quality’ nature such as better forests (say 50). Thus the total value or price = 750.

It is claimed that this measure of value differs from Marx’s value total which would only include human labour time (300). The extended model now assumes that 100 of that labour time goes to the subsistence of the human workforce. So in Marx’s value theory, while surplus value would be (300-100) or 200, while in the new generalised value theory it would be 750-100, or 650; so way more value is created and way more surplus value. More exploitation!

But the extended formula is faulty. First, the extended theory excludes value transferred from machinery used up in production (c). It only considers new value created. But total value in production is c+v+s, remember. This difference is important because much of the extra value identified in the extended formula is already incorporated in Marx’s value measure. ‘Animal labour’ is not the equivalent of human labour. In the capitalist mode of production, horses, bees and slaves are treated as machines or raw materials. So their contribution is included in the raw materials or machines used up in production, ie in (c). The value of the commodity in Marx’s theory of value thus already includes human labour, nature as raw materials used up and ‘animals’ as machines also used up in production. There is no need to invent new forms of value.

This brings me to the question of whether machines create new value. This is the question that President Petro is concerned with. It is an old issue about whether machines create value (including AI). Marx’s answer was that value is only created by human labour power. Machines have value (but it is value created by previous human labour power to make them). They have use value (they raise the productivity of labour) but they do not create new value. As Marx said, if human labour stopped working, machines would also. Even AI needs human input (training, data, prompting etc) – as we can readily see from the M&C’s ‘dialogue’ with GZ.

If there were only machines making machines and producing without any labour, there would be no value (and no capitalist mode of production because the exploitation of human labour does not happen). But we are a long way from that. Moreover, human intelligence is creative and imaginative ie it thinks of things that do not yet exist; while machines/AI do not – again that is proven by the GZ model just regurgitating M&C’s leading questions into answers that the M&C trainer wants to have.

In Marx’s economic theory, abstract labour is the only source of value and surplus-value. However, in the case of an economy where robots build robots build robots and there is no human labour involved, surely value is still created? This was the argument of Dmitriev in 1898, in his critique of Marx’s value theory. He said that, in a fully automated system, a certain input of machines can create a greater output of machines (or of other commodities). In this case, profit and the rate of profit would be determined exclusively by the technology used (productivity) and not by (abstract) labour. If 10 machines produce 12 machines, the profit is 2 machines and the rate of profit is 2/10 = 20%.

But value reduced to just use value has nothing to do with Marx’s notion of value, which is the monetary expression of abstract labour expended by labourers. If machines could create ‘value’, this value would be use-value rather than value as the outcome of humans’ abstract labour. But, if machines can create ‘value’, so can an infinity of other factors (animals, the forces of nature, sunspots, etc.) and the determination of value becomes impossible. And if machines supposedly could transfer their use-value to the product, this would immediately come up against the problem of the aggregating the value of different use-values – e.g. apples plus pears, as in the extended formula presented by GZ above.

For Marx, machines can be valued but they do not create (new) value. Rather, concrete labour transfers the value of the machines (and, more generally, of the means of production) to the product. They increase human productivity and thus the output per unit of capital invested, while decreasing the quantity of living labour needed for the production of a certain output. Given that only labour creates value, the substitution of the means of production for living labour decreases the quantity of value created per unit of capital invested.

The Dmitriev critique confuses the dual nature of value under capitalism: use value and exchange value. There is use value (things and services that people need); and exchange value (the value measured in labour time and appropriated from human labour by the owners of capital and realised by sale on the market). In every commodity under the capitalist mode of production, there is both use value and exchange value. You can’t have one without the other under capitalism. But the latter rules the capitalist investment and production process, not the former.

Value (as defined) is specific to capitalism. Sure, living labour can create things and do services (use values). But value is the substance of the capitalist mode of producing things. Capital (the owners) controls the means of production created by labour and will only put them to use in order to appropriate value created by labour. Capital does not create value itself. So in our hypothetical all-encompassing robot/AI world, productivity (of use values) would tend to infinity while profitability (surplus value to capital value) would tend to zero.

The essence of capitalist accumulation is that to increase profits and accumulate more capital, capitalists want to introduce machines that can boost the productivity of each employee and reduce costs compared to competitors. This is the great revolutionary role of capitalism in developing the productive forces available to society.

But there is a contradiction. In trying to raise the productivity of labour with the introduction of technology, there is a process of labour shedding. New technology replaces labour. Yes, increased productivity might lead to increased output and open up new sectors for employment to compensate. But over time, a ‘capital-bias’ or labour shedding means less new value is created (as labour is the only content of value) relative to the cost of invested capital. So there is a tendency for profitability to fall as productivity rises. In turn, that leads eventually to a crisis in production that halts or even reverses the gain in production from the new technology. This is solely because investment and production depend on the profitability of capital in our modern (capitalist) mode of production.

The key issue is Marx’s law of the tendency of the rate of profit to fall. A rising organic composition of capital leads to a fall in the overall rate of profit engendering recurring crises. If robots and AI do replace human labour at an accelerating rate, that can only intensify that tendency. Well before we get to a robot-all world, capitalism will experience ever-increasing periods of crises and stagnation.

So you can see that while Marx’s value theory explains why the profitability of capital will tend to fall and thus engender regular and recurring crises of production and investment, the so-called better ‘extended nature’ theory of value of M&C and GZ would only show an ever rising amount of surplus value for capital without any crises ensuing within the capitalist mode of production. The crisis could be only environmental. The capitalist mode of production would have no internal, integrated contradiction between profit and human social need.

Capitalism tries to turn the ‘free gifts of nature’ into profit. In so doing, it depletes and degrades natural resources, flora and fauna, organic and inorganic. However, there is a constant battle by capital to control nature and to lower rising prices of ‘raw materials’ as natural resources are depleted and not renewed, adding another factor to the tendency of the rate of profit to fall (see above, the book, Capitalism in the 21st century, pp15-18, which actually measures the hit to profitability from this).

None of these arguments are mentioned in the M&C-GZ dialogue which continues to try and come up with a yet more generalised theory of value that apparently includes intrinsic value (use value?) plus transformative value (applied human labour) plus ecological value (the impact of nature) and social value (community well being). Now we have a value theory that provides not a critical analysis of the contradiction between value and wealth, use value and exchange value, or between profit and social need that Marx’s value theory does, but instead a theory of the ‘value of everything’, whether under capitalism or not. This, in my opinion, renders value theory redundant and frees capitalism from its contradiction and crisis.

The dialogue talks of Marx’s ‘labour fetishism’ by leaving out nature as a source of value; and Marx’s ‘idealist approach’ by leaving out nature; and Marx’s ‘anthropomorphic’ human-biased approach by leaving out nature. Marx’s supporters are also unscientific because they fail to develop value theory with “a more nuanced analysis” (says GZ) that includes nature. A scientific approach would not stick at a “staunch defense of every last syllable written by Marx”; instead it would progress just as Einstein did with general relativity to amend Newton’s classical physics or quantum mechanics which has now amended general relativity.

M&C then takes the opportunity to single out the worst offenders in sticking with Marx’s value theory. There are “contemporary exponents who see nature as merely a ‘resource reservoir’ or at most as a passive matrix subordinate to human labour activity as the ‘only’ value generator, linked to the creation of real wealth but excluded from the capitalist valuation process as a whole are British economist Michael Roberts and Marxist intellectual Rolando Astarita. Additionally, we can mention the positions of Argentina Trotskyist academic commentators Esteban Mercatante and Juan Dal Maso, who are opposed to any theoretical expansion of Marxist orthodoxy to give a more prominent place to nature in economic analysis.” Socialist ecologist John Bellamy Foster is also attacked as another defender of Marxist orthodoxy.

The GZ model obligingly backs M&C and goes further by claiming a false consciousness on the part of these contemporary Marxist orthodoxists. “The refusal to consider the role of nature in value creation as theoretically legitimate may stem from a reluctance to deviate from established Marxist doctrine rather than a comprehensive analysis of value creation.” So we are indoctrinated and not scientific. Thanks GZ (or more appropriately, M&C).

Finally, what is all this dialogue about? It seems that M&C are convinced that Marx and Engels disregarded the role or value of nature as opposed to humans on our planet. But this is a travesty of M-E’s views. Let me quote Engels from his early work, Umrisse (to be found in my book, Engels 200 p88).

“To make earth an object of huckstering — the earth which is our one and all, the first condition of our existence — was the last step towards making oneself an object of huckstering. It was and is to this very day an immorality surpassed only by the immorality of self-alienation. And the original appropriation — the monopolization of the earth by a few, the exclusion of the rest from that which is the condition of their life — yields nothing in immorality to the subsequent huckstering of the earth.” Once the earth becomes commodified by capital, it is subject to just as much degradation as labour.

And then from his great book, the Dialectics of Nature: “Thus at every step we are reminded that we by no means rule over nature like a conqueror over a foreign people, like someone standing outside nature — but that we, with flesh, blood, and brain, belong to nature, and exist in its midst, and that all our mastery of it consists in the fact that we have the advantage over all other beings of being able to know and correctly apply its laws.” He continues: “men not only feel, but also know, their unity with nature, and thus the more impossible will become the senseless and antinatural idea of a contradiction between mind and matter, man and nature, soul and body. …

It is not Marx and Engels who disregard the role and value of nature, it is the capitalists – at least until it has now hit them in the face with climate change. For Marx and Engels, the possibility of ending the dialectical contradiction between man and nature and bringing about some level of harmony and ecological balance would only be possible with the abolition of the capitalist mode of production. This conclusion seems to have been lost by our Marxists of Collapse.

October 1, 2024

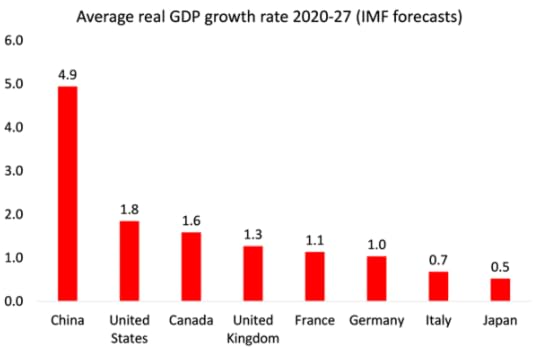

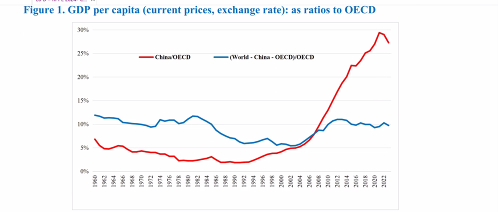

PRC 75 today

Today is the 75th anniversary of the founding of the People’s Republic of China (PRC). The survival of the PRC is now longer than the Soviet Union, which lasted 74 years. China has nearly one-fifth of the world’s population and on some measures is the largest economy in the world, although per person national income is only 30% of that of the US.

Where is China going from here? According to the Western media and mainstream economists, either into total meltdown or stagnation, Japanese-style.

Here is a representative example of this view. https://www.ft.com/…/e6e1d130-5f2e-446a-9120…

My own view has been spelt out in various papers and articles.

Here is my view of the nature of the Chinese state and its economy.

https://www.academia.edu/…/China_as_a_transitional…

And here are some recent posts on the current state of the Chinese economy.

https://thenextrecession.wordpress.com/…/chinas-third…/

https://thenextrecession.wordpress.com/…/chinas-unfair…/

https://thenextrecession.wordpress.com/…/china-versus…/

And what will happen to China in the next decade.

https://thenextrecession.wordpress.com/…/chinas-next…/

https://thenextrecession.wordpress.com/…/china…/

https://thenextrecession.wordpress.com/…/chinas-growth…/

China is not a socialist society. Its autocratic one-party Communist government is often inefficient and bureaucratic. The Maoist regime suppressed dissidents ruthlessly and the cultural revolution was a shocking travesty. Nobody can speak out against the top regime without repercussions. China’s leadership is not accountable to its working people; there are no organs of worker democracy.

But remember, all China’s so-called ‘aggressive behaviour’ and ‘crimes against human rights’ are easily matched by the crimes of imperialism in the last century alone: the occupation and massacre of millions of Chinese by Japanese imperialism in 1937; the continual gruesome wars post-1945 conducted by imperialism against the Vietnamese people, Latin America and proxy wars in Africa and Syria, as well as the more recent invasion of Iraq and Afghanistan; and the war in Ukraine and the devastation of Gaza and Lebanon; and the appalling nightmare in Yemen by the disgusting US-backed regime in Saudi Arabia.

And don’t forget the horrific poverty and inequality that weighs for billions under US-led imperialism, unlike China.

China is at a crossroads in its development. Its capitalist sector has deepening problems with profitability and debt. But the current leadership has pledged to continue with its state-directed economic model and autocratic political control. And it seems determined to resist the new policy of ‘containment’ emanating from the ‘liberal democracies’. The trade, technology and political ‘cold war’ is set to heat up over the rest of this decade, while the planet heats up too.

September 28, 2024

Austria: stuck in the middle

On Sunday, Austria has a general election for its parliament. The 183 members of the National Council are elected by open list proportional representation at three levels; a single national constituency, nine constituencies based on the federal states, and 39 regional constituencies. Seats are apportioned to the regional constituencies based on the results of the most recent census. For parties to receive any representation in the National Council, they must either win at least one seat in a constituency directly, or clear a 4 percent national electoral threshold. Around 6.3 adult Austrians can vote.

The latest opinion polls indicate that the neo-fascist Freedom Party (FPÖ), founded in the 1950s by former SS officers will end up being the largest party at 27%, just ahead of the conservative People’s Party (ÖVP) at 25%, who currently lead the incumbent coalition government with the Greens. The Social Democrats (SPO) are running third with 21%. FPO leader Herbert Kickl wants to be Chancellor (prime minister) and uses the term “Volkskanzler,” or chancellor of the people, first used by the Nazis and Adolf Hitler in the 1930s.

If the FPO does get the biggest vote share, it could be in a position to lead a new government – except that up to now the leaders of the OVP and the Social Democrats are refusing enter into a coalition with the FPO (but the conservatives have hinted that they could if the current FPO leader Herbert Kinkl is not in the government). The likely result is an OVP-FPO coalition or for the first time a three-way alliance of the OVP with the SPO and either the liberal NEOS or the Greens.

The rise of the FPO is not new. The FPO was junior partner to the OVP in the government of the 2010s. But this fell apart when both parties were involved in a corruption scandal that brought down the government and its FPO chancellor in 2019. But now everywhere in Europe, ‘hard-right’ parties are gaining ground in response to the so-called ‘threat’ of immigration and the economic stagnation in many European economies. In June, the FPO was the largest party for the first time in the European Assembly election, which also brought gains for other European far-right parties.

Austria has only 9 million people, but over the past decade the country has taken in more refugees per capita than any other EU country, fueling the FPÖ’s resurgence. The FPO has now evolved into a kind of anti-migrant, anti-Islam ‘populist’ party, as seen elsewhere in Europe. The FPO wants to end immigration and ‘remigrate’ immigrants to their ‘home’ countries. “Remigration is long overdue!” proclaims Kickl. The FPO also hints at leaving the EU, or “Öxit,” an Austrian-style Brexit.

But as elsewhere in Europe, the rising support for hard right anti-immigration parties is as much to do with the stagnation in the major economies and high inflation eating into living standards. It can be said that if Germany has a cold, Austria will get the flu. And Germany is suffering from a very heavy cold for its economy right now. As a result, the spillover to Austria is heavy.

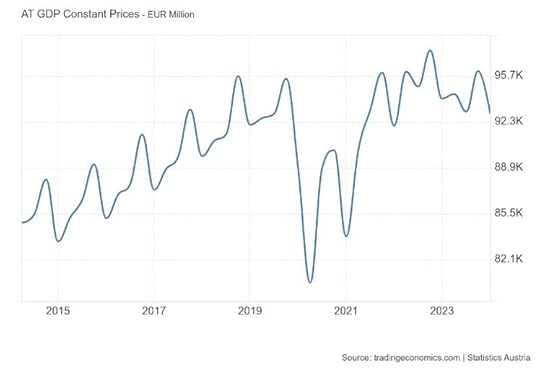

Austria’s real GDP growth is stagnating at best. Indeed, ironically, if it were not immigration (+6.3% in 2011-2020), real GDP would have fallen sharply, as the domestic population is shrinking and ageing. Austria will have the third highest old-age related costs in the European Union as a percentage of GDP by 2030.

Moreover, Austria is still experiencing high inflation, averaging 4.2% over the past 12 months, surpassing the EU average. Inflation remains high because Austria has been forced to reduce its imports of cheap Russian gas as part of EU sanctions against Russia over Ukraine. Austria is caught in the middle over trade with Russia and with Western Europe.

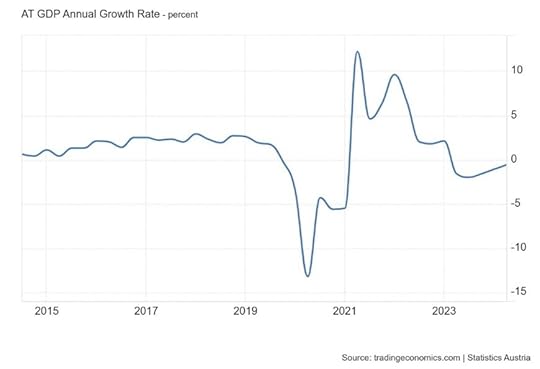

The economy was in outright recession in 2023. The Austrian central bank, the OeNB, now expects the economy to ‘stabilise’ this year, with real GDP up by just 0.3. Even that looks optimistic. Austria’s GDP fell 0.6% Q2 2024, following a downwardly revised 1% contraction in the previous Q1. Recession continues.

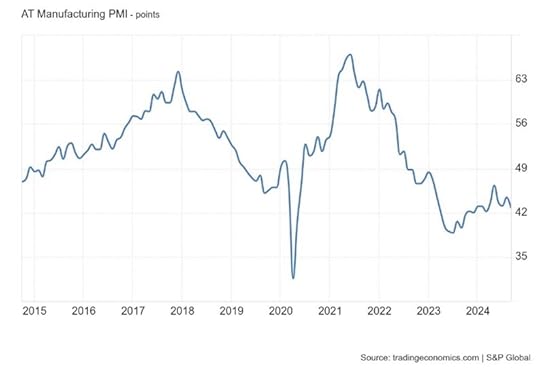

Austrian capital is struggling. Manufacturing is in deep recession (anything below 50 in the graph below means contraction), as it is in Germany.

Austria’s real GDP per capita growth stagnated nationwide in 2011-2020 and was lower than the EU average (0.6%) in all regions. Labour productivity is stagnating or decreasing in most regions. That’s because productive investment is still shrinking, after falling 2.3% in 2023.

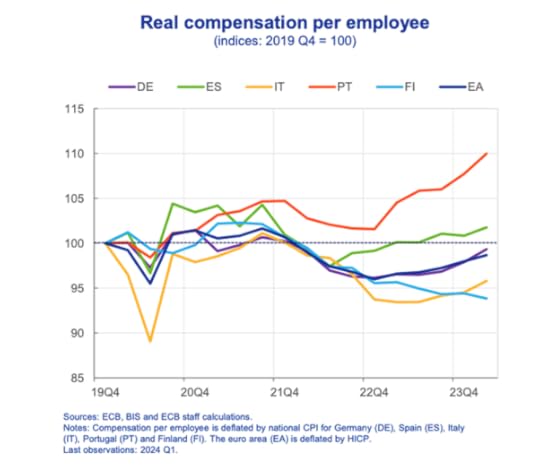

Austrian capital is being squeezed because, alongside falling labour productivity, there are rising wages for Austria’s organised workers, the fastest wage rise in Europe this year. Workers try to restore the losses in real incomes they have suffered from high inflation rates after COVID. Even though wages are set to rise by 8.5% this year, that still does not compensate for previous years’ high inflation. And although unemployment is still near lows, new jobs are mainly part-time without any permanent career prospects and pay poorly.

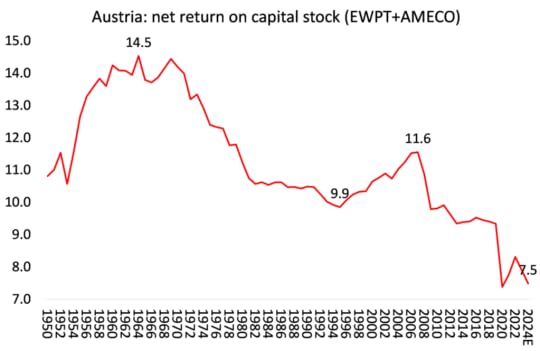

Behind falling productive investment and labour productivity is the fall in the profitability of Austrian capital, mirroring that in Germany. The rise in the early 2000s has given way to steep decline in the 2010s, accelerating since COVID.

What are the solutions offered by the parties to this economic stagnation? The FPO has mix of neo-liberal, pro market policies with some support for older Austrians, who generally vote for it, like raising state pensions rates. The FPO wants ‘more deregulation’ and lower taxes, including cutting corporation tax on small businesses from 23% to 10%; and ending ‘green’ measures by scrapping a tax on carbon emissions introduced in 2022. It advocates price controls during times of severe inflation on food, rent and energy as well as reducing sales tax on essentials. And it wants to maintain Russian energy imports.

The Conservative OVP wants to do pretty much the same things as the FPO, except it wants to keep to EU sanctions on Russia by ‘promoting renewable energy’. The Social Democrats want some new taxes on the wealthy to pay for tax cuts for the rest of Austrians and they would raise corporate tax and place a one-off levy on energy companies and banks; with a state company to invest in renewable energy to reduce dependence on Russian gas.

None of these policies offer any probability of raising investment rates or productivity, let alone increasing real incomes for most Austrians. So any coalition formed after this election, whether led by the FPO or the OVP, will change little.

September 21, 2024

Sri Lanka’s debt default

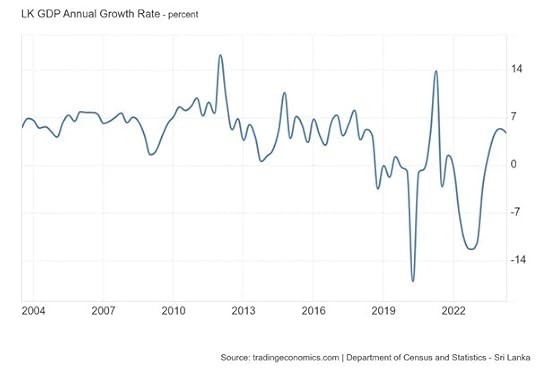

Today, 21 September, Sri Lanka will hold its first presidential election since the July 2022 popular uprising known as the Aragalaya, which drove the corrupt President Gotabaya Rajapaksa from power. Sri Lanka had entered the most damaging economic crisis since independence from British colonial rule in 1948. After total mismanagement of the economy by Rajapaksa and the hit from the COVID pandemic, in 2021 the Sri Lankan Government officially declared the worst economic crisis in the country in 73 years. Most foreign debt repayments were suspended after two years of money printing to support tax cuts. The economy contracted 7.8% and the percentage of the population earning less than $3.65 a day doubled to around 25% of the population.

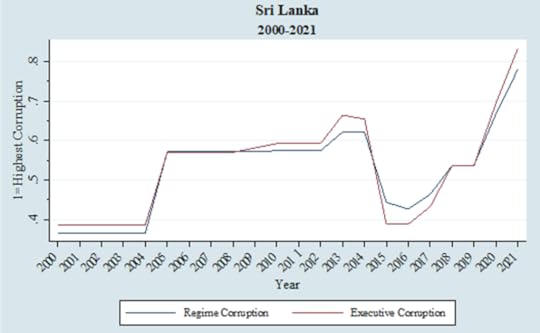

Rising indebtedness and concern over the ability to service its external debt, a sharp deterioration in the country’s ability to export (exports of goods and services which accounted for around 35% of GDP in the early 2000s had collapsed to – and subsequently stayed at – around 20% by 2010), degraded governance, growing corruption (see index below) and slowing growth were the features of Sri Lanka’s trajectory in the last decade and a half.

The ratio of public debt to GDP had jumped to 119% by 2021. External debt that stood at $11 billion in 2005 had surpassed $56 billion by 2020 – equivalent then to 66% of GDP.

With Rajapaksa driven from power by a popular revolt, the ruling orders managed to get Ranil Wickremesinghe into the presidency. He immediately applied for an IMF bailout which was eventually agreed in March 2023. The IMF loaned $3 billion to the country as part of a 48-month debt relief program. The first tranche of $330m was released soon after with an additional $3.75 billion expected to follow from the World Bank, the Asian Development Bank and other lenders.

As usual, the IMF has imposed strict austerity measures on the Wickremesinghe administration in return for the bailout. Pensions have been cut, income taxes have been hiked 36% and subsidies on food and other essentials have been removed. Electricity bills rose 65%. As elsewhere, inflation has subsided in the past year, but prices are still up over 75% since the crisis of 2021. And the Sri Lankan rupee is still more one-third weaker against the dollar than before the crisis.

And the government wants to privatise state-owned enterprises like Sri Lankan Airlines, Sri Lankan Insurance Corporation and Sri Lanka Telecom. This has triggered a fresh wave of protests. “The government should not put the burden of the reforms on the salaried class and middle class who are already affected by the economic crisis,” said Anupa Nandula, the Vice President of the Ceylon Bank Employees Union.

The World Food Programme estimates that 8 million Sri Lankans – more than a third of the population – are “food insecure”, with hunger especially concentrated in rural areas. Almost half of all Sri Lankan families spend about 70% of their household income on food alone. “Many families from the middle class have now slipped below the poverty line,” said Malathy Knight, a senior economist with private think tank Verite Research. The World Bank says: “Poverty is projected to remain above 25% in the next few years due to the multiple risks to households’ livelihoods.” Young people are desperate to leave the island. Over 300,000 left in 2022 alone; many skilled workers like doctors, paramedical and IT professionals.

According to the World Inequality Lab, the top 10% of Sri Lankans take 42% of all income and own 64% of all personal wealth; the top 1% have 15% of all income and 31% of all wealth. The bottom 50% of Sri Lankans have just 17% of all income and only 4% of all personal wealth!

The World Bank estimates that Sri Lanka’s economy shrank by 9.2% in 2022, contracted by a further 4.2% in 2023, with a slight recovery (1.7%) this year. Manufacturing has finally come out of recession in the last few months.

President Wickremesinghe hopes to win the election as the candidate of the traditional conservative party, the United National Party (UNP). He faces Sajith Premadasa, who leads the Samagi Jana Balawegaya (SJB) party that broke with the UNP in 2020. Premadasa favours a mix of ‘interventionist’ and free-market economic policies and would stick with the IMF-imposed economic programme. But the real surprise is the rise of Anura Kumara Dissanayake, a longtime opposition figure and leader of the People’s Liberation Front, or JVP. The JVP is now leading in the polls. The JVP is now the leading formation in the National People’s Power (NPP) a leftist political alliance. Dissanayake has vowed to renegotiate terms of the IMF programme. “The implementation of the IMF programme has caused significant hardship for the people.” He has also pledged to scrap Sri Lanka’s presidential system and return to the British-style parliamentary democracy, which existed until 1978.

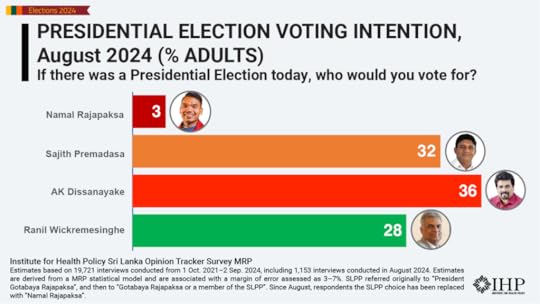

But none of the four major party presidential candidates have the support of a majority of the voters. NPP/JVP leader Dissanayake leads with 36% of all adults followed by SJB leader Sajith Premadasa with 32%, President Ranil Wickremesinghe with 28% and Namal Rajapaksa (from the Rajapaksa family!) with 3%.

Dissanayake is strongest among the youth with a majority (53%) supporting him and among Sinhala voters (42%). The most affluent third of voters (38%) support Wickremesinghe. In contrast, Premadasa leads among the poorest third of the 17m voters (40%). Given that Sri Lanka’s election vote is based on proportional representation, everything will depend on second and third preferences. That will probably work against the JVP which holds only three seats in the current parliament anyway.

Whoever wins faces a mighty challenge in rectifying the collapse of this small island economy. Sri Lanka’s GDP is about $80bn. From 2003 to 2019, average growth was 6.4% a year, well above its regional peers. This growth was driven by the growth of non-tradable sectors, ie construction and transport. Apart from tourism, that did not raise enough foreign currency to fund massive spending that the Rajapaksa government launched to maintain its political power. Economic expansion started to slow in 2019 and then the COVID pandemic pushed the economy into a deep recession from which it has hardly recovered. To meet its obligations to the IMF and foreign creditors, years of austerity and reduction in living standards lie ahead.

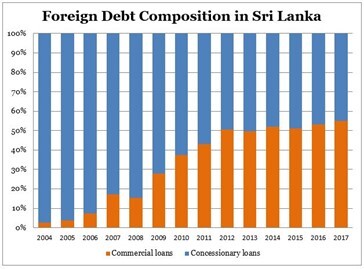

One of those foreign creditors is China. Western media claim that it is China that has forced Sri Lanka into crisis through is a policy of debt trap, by lending it more than it can pay back and then getting it to default, so acquiring control of the assets – the most famous example being the Hambantota Port project. But this is a myth. Only a little over 15% of Sri Lanka’s foreign debt is owed to China and most of that is in the form of concessionary loans. Most is owed to commercial creditors from the West and from India. Unlike concessionary loans obtained to carry out a specific development project, these commercial borrowings do not have a long payback period or the option of payment in small installments and rates are higher.

The true story of the Hambantota Port project can be found here.

Economists from the London School of Economics reckon the answer to Sri Lanka’s economic crisis is to privatise its unproductive state sector. It’s true that the Rajapaksa government milked the assets of the state companies for their own enrichment. “SOEs have been attractive to politicians for the ability to distribute resources, jobs, contracts and other benefits for themselves and their coteries. This has certainly been the case in the Rajapaksa era.”

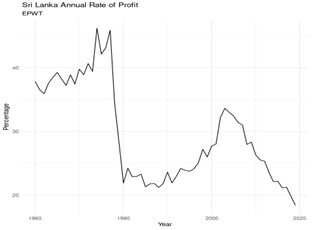

Numbering between 420 and 520, these state companies have generally performed badly, making substantial losses. SOE productivity has declined substantially in the past decade, with their average cost of labour being around 70% higher than in private (ie state employment pays better). In addition, total SOE debt has climbed steadily from around 6.5% of GDP in 2012 to over 9% in 2020. But Sri Lanka’s capitalist sector is little better. Productive investment is very low and that’s because profitability has collapsed since the early 2000s.

Sri Lanka is a stark example of the debt crisis in so many Global South economies, especially since the end of the pandemic. The answer is not IMF-imposed austerity measures and privatisations, but the cancellation of the foreign debt, along with public investment into restoring the state-owned companies and reviving industry based on new technologies and on the highly educated skills of many Sri Lankans. But don’t hold your breath.

September 20, 2024

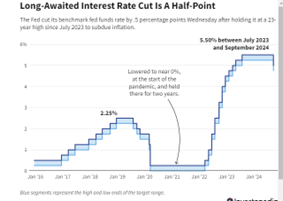

The Fed finally pivots

Last Wednesday’s decision of the US Federal Reserve Bank’s monetary committee to cut its ‘policy interest rate’ is significant in two ways. First, it signals that the Fed reckons that the ‘war against inflation’ is over. The Fed’s cut was the first since 2020. The last few years since the end of pandemic slump have seen a very sharp rise in the policy rate from nearly zero in 2021 to 5.5% in 2023.

The policy rate acts a floor for all rates of borrowing by households for mortgages and consumer credit and for companies for loans and bond prices in the US. But not just in the US. The world’s corporations and governments borrow money mainly in dollars. So the Fed’s policy rate affects indirectly borrowing rates in all countries, particularly those with heavy debt obligations in the Global South. The Fed’ s high interest rate has driven up the debt servicing burden for the poorest countries, many of which are in ‘debt distress’, some even defaulting on their payments.

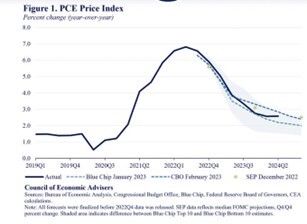

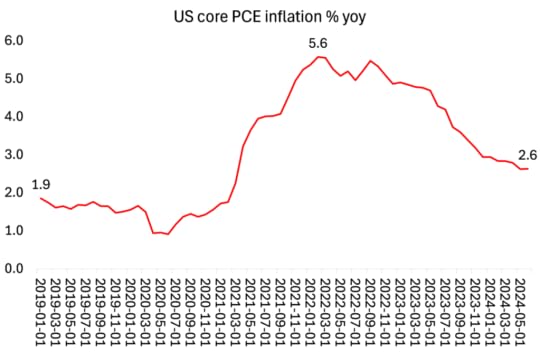

Second, Fed cut is significant because of the size of the reduction. The Fed committee decided to reduce the policy rate by 50bp (0.5%), not 25bps as is usual. This implies two things: one rosy and one not so rosy. It suggests that the Fed is confident that the US inflation rate will continue to drop down towards the 2% a year policy target. The Fed measures inflation using the change in prices for personal consumption expenditure (PCE) and the PCE rate is now down to 2.3% and the Fed projection is that this rate will fall to the target of 2% by 2026 (so still some two years away).

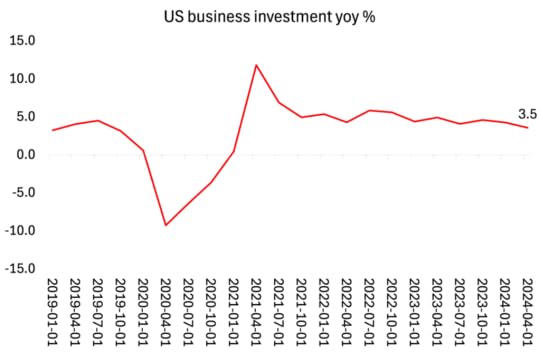

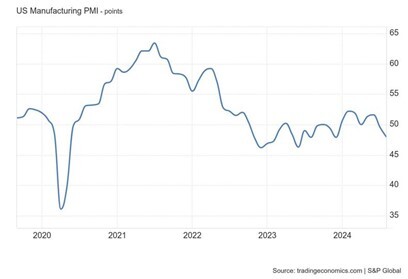

But it also suggests that the US economy is showing significant signs of slowing down. Real GDP growth has averaged around 2.2% in the first half of 2024. But that growth rate is forecast to slow in the third quarter just ending. The St Louis Federal Reserve forecast is for 1.6% in this current quarter, although the Atlanta Fed forecast is higher at 2.9%. The US manufacturing sector remains in a slump despite the construction boom is AI infrastructure. The unemployment rate has been edging up to levels that some indicators would suggest a coming recession.

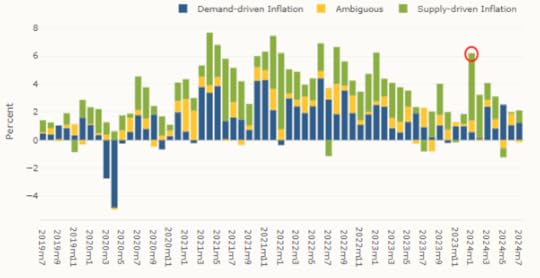

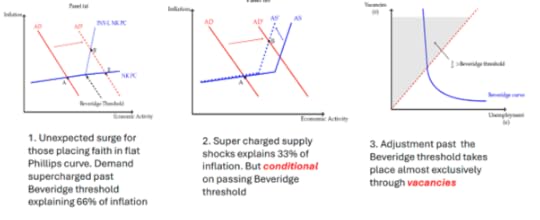

In addition, using the PCE inflation seriously underestimates inflation. The main reason for the rise in inflation since 2022 has been the rise in energy and food prices driven by the disruptions in international supply chains after the pandemic and poor productivity growth ie supply factor. It was not due to ‘excessive’ government spending or ‘excessive’ wage rises ie demand factors. The evidence for this from many studies is overwhelming.

The fall in the ‘headline’ inflation rate has been mainly due to a decline in the rise energy and food prices. Underneath that, ‘core’ price inflation has not declined by nearly so much. Core PCE inflation is still around 2.6% a year in the US. And if various components of household spending (insurance, mortgages etc) were properly included in the inflation basket, it would tell a different story, putting the inflation rate several points higher than the PCE measure. The Fed’s monetary policy actions did not stop inflation rising and had little to do with it subsequently falling.

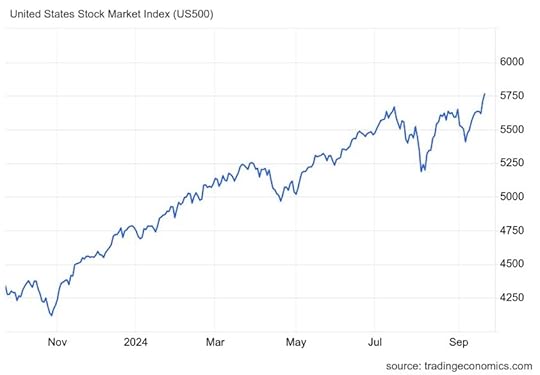

Nevertheless, the Fed claims that inflation has been subdued by the Fed’s monetary policy and most important, without causing a slump in the economy. The Fed committee’s projections are for 2% a year real GDP growth, 2% inflation and an unemployment rate stabilising at about 4.4% – in other words, a perfect ‘soft landing’ for the economy; a ‘Goldilocks scenario’ of an economy neither ‘too hot’ nor ‘too cold’ , but just right. This scenario is echoed by all the major mainstream economists in the major investment banks and so is swallowed by the majority of financial investors. As a result, the US stock and bond markets hit new highs after the Fed rate cut.

I’ve discussed the nature and likelihood of this so-called ‘soft landing’ in a previous post. Suffice it to say at this point, I don’t think that the US economy is going into a recession just yet. Corporate profits are holding up and giving financial supports to some investment, although most of these profits are being made by the mega-tech Magnificent Seven companies and most of the investment is by these companies in AI and chip infrastructure, partly subsidised by the Biden administration.

The vast swathe of the US corporate sector is struggling, particularly small businesses, hit by high interest rates, poor demand for their goods and services and increased costs of inputs and services.

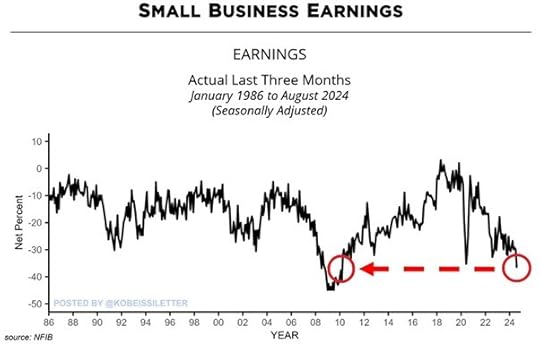

Around 37% of US small businesses have seen their earnings drop over the last 3 months, the highest share in 14 years. This is even weaker than the 35% seen during the 2020 pandemic. Small businesses are struggling as if the economy is in a recession.

Also there has to be a sense of proportion here. Financial investors may be excited by the start of a series of reductions in interest rates making it it cheaper to borrow and speculate in ‘fictitious capital’, but the US ‘real economy is hardly motoring. The Fed forecasts just 2% a year in real GDP for the rest of this decade. That rate is well below the average growth rate before the Great Recesison of 2008-9 and before the pandemic, but that means a much lower rate of real GDP per person as the population expands through immigration.

And the US economy is the best performing of the top seven major capitalist economies (G7). Germany is in a slump, the UK, France and Italy are flatlining; Canada and Japan are stagnant. Only the smaller southern European economies in Europe are doing better and they are coming from a very low base. As for the so-called ‘emerging economies’ of the Global South, South Africa is in a slump; Brazil is crawling; Russia is only growing as a ‘war economy’, while China and India’s fast-growing economies are also showing signs of slowing down. The Fed rate cuts will do nothing to change these trends.

September 12, 2024

Saving European capital: it’s an existential challenge

About a year ago, the European Union’s Commission asked Mario Draghi to write a landmark report on the future of Europe’s economy. Draghi is a former Goldman Sachs banker, former head of the Italian central bank and then President of the European Central Bank, before becoming briefly the prime minister of Italy. So, in the eyes of the Commission, he was clearly suited to look for ways of saving European capital from falling behind the rest of the world.

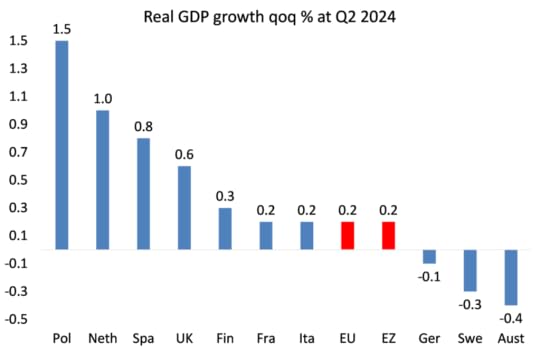

This week Draghi’s report was published. This is at a time when the major European economies are either in recession (Germany, Sweden, Austria) or stagnating (France, Italy). Hardly any EU economy is growing more than 1% a year and the EU/EZ area average is just +0.2%.

The report, called is 600pp long. It paints a miserable but accurate picture of the EU economies’ relative decline in output and productivity growth, living standards and technical progress compared to the US and Asia.

Europe came out of a terrible war in 1945 that decimated its people and the economy. But over the next 50 years of the 20th century it made a rapid recovery economically (at least in the core countries of Europe), eventually rivalling output and living standards in North America and Japan. It established new institutions aimed at intergrating the national economies of the region and avoiding any more wars within.

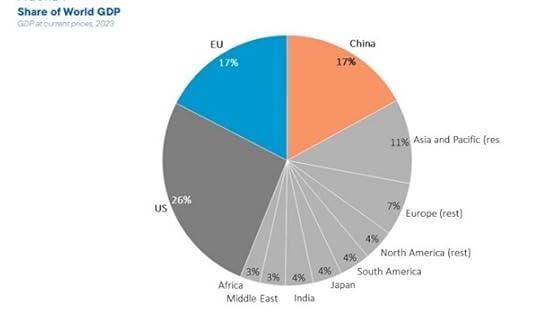

The report says, “the European model combines an open economy, a high degree of market competition and a strong legal framework”. It has built a ‘Single Market’ of 440 million consumers and 23 million companies, accounting for around 17% of global GDP, while achieving rates of income inequality that are around 10 percentage points below those seen in the US and China.

At the same time, the EU has delivered leading outcomes in terms of governance, health, education and environmental protection. Of the world’s ten top-scoring countries for the application of the ‘rule of law’, eight are EU member states. Europe leads the US and China in terms of life expectancy at birth and low infant mortality. Europe’s education and training systems deliver high educational attainment, with a third of adults having completed higher education.

The EU is also the world leader in sustainability and environmental standards, backed by the most ambitious global targets for decarbonisation and can benefit from the largest exclusive economic zone in the world, covering 17 million square kilometres, four times the EU’s land surface.

But now it is in serious crisis – indeed Draghi calls the situation “an existential challenge.” And in the report,Draghi goes steadily through the sorry story of Europe’s relative economic performance in the 21st century – indeed since the euro single currency was launched.

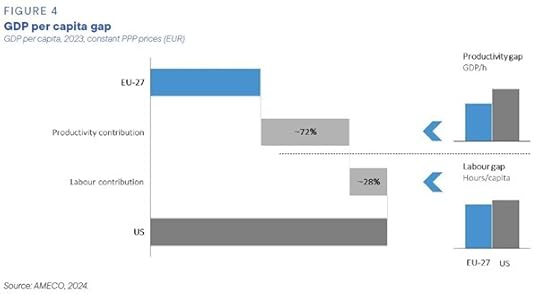

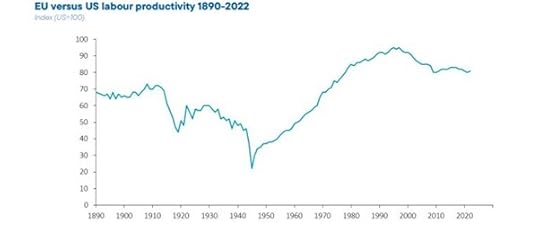

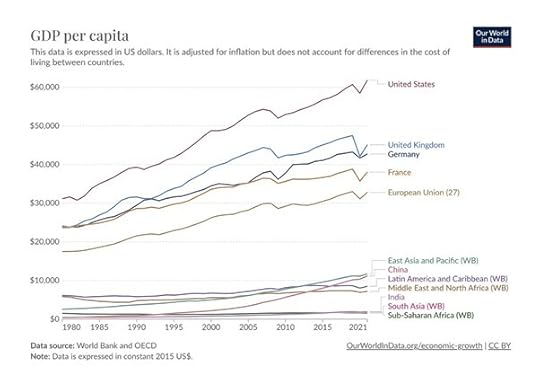

EU economic growth has been persistently slower than in the US over the past two decades, while China has been rapidly catching up. The EU-US gap in GDP at 2015 has gradually widened from slightly more than 15% in 2002 to 30% in 2023. The gap has widened less on a per capita basis as the US has seen faster population growth, but it is still significant at 34% today. The main driver of these diverging developments has been productivity. Around 70% of the gap in per capita GDP with US is explained by lower productivity in the EU.

Many EU economies have prospered and depend on expanding world trade. But the era of rapid world trade growth has passed: the IMF projects world trade to grow at just 3.2% a year over the medium term, a pace well below its annual average from 2000-19 of 4.9%. Indeed, the EU’s share in world trade is declining, with a notable fall since the onset of the pandemic.

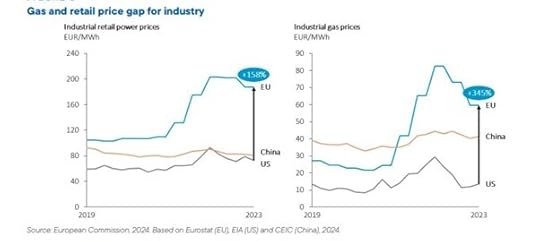

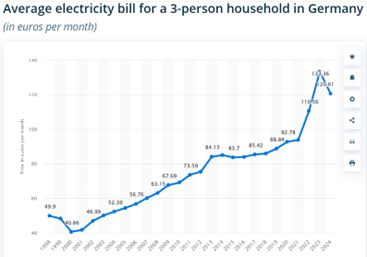

In the past, Europe was able to satisfy its demand for imported energy by procuring ample pipeline gas from Russia, which accounted for around 45% of the EU’s natural gas imports in 2021. But following the Ukraine conflict, this cheap energy has now disappeared at huge cost to Europe. The EU has lost more than a year of GDP growth, while having to re-direct massive fiscal resources to energy subsidies and building new infrastructure for importing liquefied natural gas. While energy prices have fallen considerably from their peaks, EU companies still face electricity prices that are 2-3 times those in the US and natural gas prices are 4-5 times higher.

Most important to Draghi is that Europe’s position in the advanced technologies that can drive future growth is declining. Only four of the world’s top 50 tech companies are European and the EU’s global position in tech is deteriorating: from 2013 to 2023, its share of global tech revenues dropped from 22% to 18%, while the US share rose from 30% to 38%.

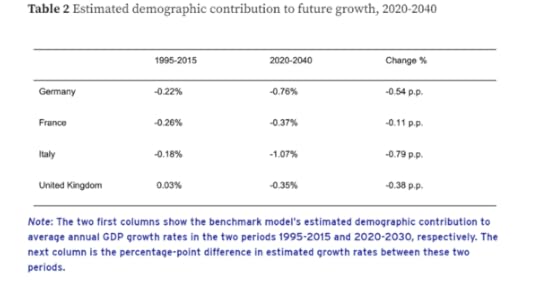

The falling behind in productivity growth is most damaging to European capital’s future. The EU is entering the first period in its history in which growth will not be supported by rising population. By 2040, the workforce is projected to shrink by close to 2 million workers each year. It’s not covered in the report but a recent new study found that Europe’s aging population “will cause massive headwinds for economic growth.” While demographic change has previously contributed positively to per capita economic growth, in the coming decades, it will reduce the growth rate of the Europe’s G4 economies by 0.3 to 1 percentage point per year.

Draghi concludes: “We will have to lean more on productivity to drive growth. But if the EU were to maintain its average productivity growth rate since 2015, it would only be enough to keep GDP constant until 2050 – at a time when the EU is facing a series of new investment needs that will have to be financed through higher growth.”

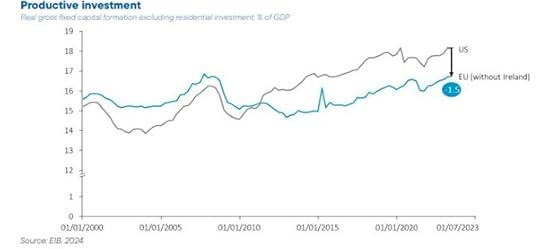

The problem is that low productivity growth is caused by low investment in productive sectors, particularly in the new technologies. The gap between productive investment to GDP in the US and Europe is some 1.5% pts of GDP every year.

The report only refers in a note to a study by the European Investment Bank (EIB) on where this gap in productive investment originates. That study shows that the overall investment rate to GDP in the EU is actually higher on average than in the US. Part of the reason is that in the Long Depression years of 2010-19, US GDP rose faster than in the EU. So even though US investment rose faster than in the EU, the investment ratio to US GDP remained lower than in Europe.

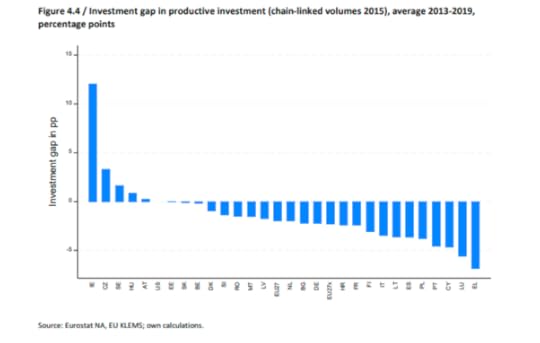

Moreover, once price deflators for real investment are properly compared for the two regions and real estate and construction investment is excluded (50% of investment in the EU compared to 40% in the US), the gap in ‘productive investment’ rates is reversed. On average over the period 2012-2020, the average gap in real terms was 2.6 pp of GDP. Fifteen countries had an investment shortfall vis-à-vis the US that was larger than the EU average, including some of the bigger economies, such as the Netherlands (2.7 pp), Germany (2.8 pp), Italy (4.0 pp), France (2.5pp) and Spain (4.3 pp) – in other words, the core of Europe.

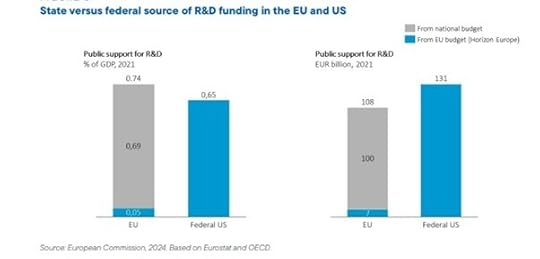

The EIB found that the EU’s investment shortfall was largely in ‘intangible assets’ ie patents, intellectual property and software etc. In these areas, the US was well ahead. EU companies specialise in “mature technologies where the potential for breakthroughs is limited, they spend less on research and innovation (R&I) – EUR 270 billion less than their US counterparts in 2021. The top 3 investors in R&I in Europe have been dominated by automotive companies for the past twenty years. It was the same in the US in the early 2000s, with autos and pharma leading, but now the top 3 are all in tech.”

What are Draghi’s explanations for the low levels of productive investment in Europe, particularly in technology? Being a good banker, Draghi lays the blame on the ‘lack of finance’ and on a failure to merge corporations into large scale multinationals that can compete with the US. “Europe is stuck in a static industrial structure with few new companies rising up to disrupt existing industries or develop new growth engines. In fact, there is no EU company with a market capitalisation over EUR 100 billion that has been set up from scratch in the last fifty years, while all six US companies with a valuation above EUR 1 trillion have been created in this period.”

Draghi says that a key reason for less efficient ‘financial intermediation’ in Europe is that capital markets remain fragmented and flows of savings into capital markets are lower. There needs to be an EU-wide capital market and EU-based venture capital that does not rely on the US. You see: “many European entrepreneurs prefer to seek financing from US venture capitalists and scale up in the US market. Between 2008 and 2021, close to 30% of the “unicorns” founded in Europe – startups that went on the be valued over USD 1 billion – relocated their headquarters abroad, with the vast majority moving to the US.”

There is just too much bureaucratic regulation and inefficient credit markets to “unlock private capital.” According to Draghi, “EU households provide ample savings to finance higher investment, but at present these savings are not being channelled efficiently into productive investments. In 2022, EU household savings were EUR 1,390 billion compared with EUR 840 billion in the US.”

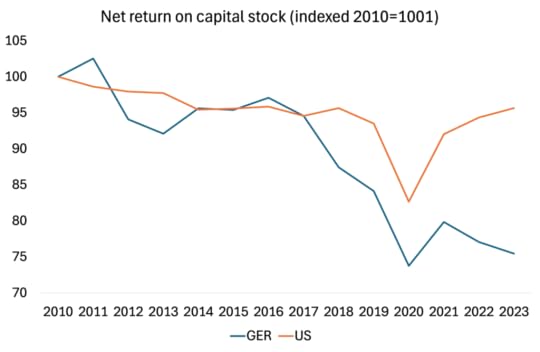

But is it inefficient EU capital markets that is the cause of lower productive investment in Europe? The report hints at the real cause when it says private financing costs are too high compared to the returns that the EU’s capitalist sector require to increase productive investment, as opposed to investing in real estate or financial assets. The real cause lies in the lower rate of profitability for European capital compared to the US. This is particularly the case since 2017 (in this example below of US and German profitability).

Source: AMECO

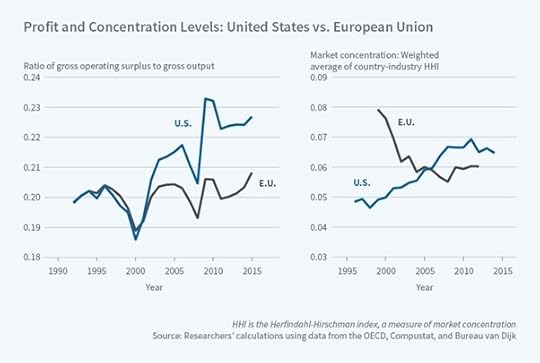

Not in the report, but perhaps relevant, is that in the EU there are many more smaller companies where profitability is low, while in the US a higher concentration of capital has boosted profits for the few mega techs at the top. Since 2000, gross profit rates in the United States have risen and industry concentration has soared, but these trends are not found in the European Union.

Draghi concludes that “the resulting cycle of low industrial dynamism, low innovation, low investment and low productivity growth in Europe could be characterised as “the middle technology trap”. But, in my view, this is a product of the ‘profitability gap’.

What is to be done about the productivity and investment gaps? Draghi says that “a minimum annual additional investment of EUR 750 to 800 billion is needed corresponding to 4.4-4.7% of EU GDP in 2023. For comparison, investment under the Marshall Plan between 1948-51 was equivalent to just 1-2% of EU GDP. Delivering this increase would require the EU’s investment share to jump from around 22% of GDP today to around 27%, reversing a multi-decade decline across most large EU economies. “ That’s a rise in investment to GDP levels not seen since the Golden Age of the 1950s and 1960s when Europe rapidly expanded after the war.

Is it feasible to expect European capital to be able or willing to restore those golden investment decades 50 years later? As the report recognises. “Historically in Europe, around four-fifths of productive investment has been undertaken by the private sector, and the remaining one-fifth by the public sector.” So in a capitalist Europe, it up to the capitalists to invest more to deliver the needed higher productivity in the key areas. The public sector cannot do that and the EU Commission and Draghi certainly don’t want public investment to replace the capitalist sector through public ownership and planning of the ‘commanding heights’ of Europe’s economies.

So Draghi’s answer is the usual pro-business solution. There must be monetary and fiscal incentives by governments to ‘encourage’ capitalists to invest. First, there must be lower costs of financing, but “delivering private investment of around 4% of GDP through market financing alone would require a reduction in the private cost of capital by approximately 250 basis points in the European Commission model.” Hardly possible in the current inflationary environment. And anyway, “although improved capital market efficiency (e.g. through the completion of the Capital Markets Union) is expected to reduce private financing costs, the reduction will likely be substantially smaller. Fiscal incentives to unlock private investment therefore appear necessary to finance the investment plan, in addition to direct government investment”.

So the EU-wide governments must provide more public funds. But this leads to another problem. EU governments, particularly in core Europe, are driven by the need to ‘balance the budget’ and not to increase public debt or tax too much. There are the EU fiscal rules that cannot be broken!

Draghi wants more ‘joint borrowing’ ie the EU issues more EU-backed debt to fund projects. But this is a great taboo in the EU. Germany and the Netherlands have low levels of public debt and are loath to backstop their more indebted neighbours. Less than three hours after Draghi finished his presentation, Germany’s Finance Minister Christian Lindner said that “Germany will not agree” to ‘joint borrowing’, as joint borrowing “can be summarized briefly: Germany should pay for others. But that can’t be a master plan.“

Draghi suggests more EU-wide taxes to boost the size of the EU Commission which is too small and concentrates spending on ‘social cohesion’, regional subsidies and agriculture rather than on ‘productive investment’.

Draghi wants to cut EU public spending in the existing areas and switch it to technology. “If the investment-related government spending is not compensated by budgetary savings elsewhere, primary fiscal balances may temporarily deteriorate before the investment plan fully exerts its positive impact on output.” Such a switch would not go down well among farmers and in eastern Europe.

To summarise, the Draghi report outlines the serious decline in European capital’s competitive performance in the 21st century compared to the US and Asia. It is an ‘existential challenge’ that can only be overcome by a massive rise in investment, mainly in new technologies. This can only be achieved by the capitalist sector investing more. Public investment is too small and, anyway, the EU’s pro-business governments don’t want to take over the major private companies and have planned public investment instead. That would be the end of a capitalist Europe. So Draghi says what they need to do is to encourage Europe’s big business to invest more with cheaper credit, deregulated markets and increased government fiscal incentives to “unlock private investment”. However, the chances of the governments of the EU member states agreeing to spend more to help EU businesses sufficiently is slim.

The only way that the required humungous upswing in productive investment could happen is if the profitability of European capital leaps forward. But that won’t be achieved by making credit costs cheaper, but only by a sharp rise in the exploitation of labour in Europe and by the ‘creative destruction’ of ‘middle technology’ to reduce costs. If that does not happen, then the EU’s relative decline globally will continue and even accelerate.

September 9, 2024

IIPPE 2024: Imperialism, China and BRICS+

The International Initiative for the Promotion of Political Economy (IIPPE) holds a conference every year. It brings together radical and Marxist economists to discuss latest theories of and developments in capitalism in sessions where many papers are presented. I have reported on previous conferences in this blog. This year’s conference took place in Istanbul, Turkey and the theme was: The Changing World Economy and Today’s Imperialism. I participated online by zoom in some sessions and also obtained papers from participants at the conference.

There were two plenary sessions on the main theme of the conference led by Trevor Ngwane of the University of Johannesburg, South Africa and Utsa Patnaik of Jawaharial Nehru University, India. I was only able to get second hand snippets of these plenaries, but as far as I can tell, Professor Ngwane was keen to tell his audience that socialists should not rely on the BRICS (or BRICS+ including new entrants, Iran, Saudi Arabia and soon Turkey) and its expanding institutions to resist the hegemony of the imperialist bloc led by the US.

The countries of the BRICS+ were just as capitalist and imperialist as the imperialist bloc of the Global North, argued Ngawani. They and their governments would exploit the poor just as much. Indeed, the most important economy in the BRICs+, China was capitalist and imperialist in its relations with the periphery. The BRICs countries could be characterised as ‘sub-imperialist’ (exploited by the imperialist bloc but exploiting others further down the ladder). The only force for change would come ‘from below’ from the working class in these countries, not from the likes of Xi in China, Modi in India, Ramaphosa in South Africe, Lula in Brazil, MbS in Saudi Arabia or the mullahs in Iran.

In my view, there is a lot of truth in Ngwane’s conclusion – we cannot expect these BRICS governments to transform the world despite their relative resistance to the US imperialist bloc. On the other hand, Ngwane’s characterisation of China as imperialist, let alone capitalist., and all the BRICS as ‘sub-imperialist’ ,does not work for me. I shall return to those issues later in this post.

Utsa Patnaik is a famous Marxist Indian economist (along with her husband Prabhat). They developed the ‘drain theory’ of exploitation: that India’s revenues in the 19th century were drained to provide profits for Britain’s world hegemonic rise.

Indeed, recently, Kabeer Bora of the University of Utah made a novel attempt to measure the transfer of value appropriated by Britain from its ‘jewel in the crown’ colony India during the 19th century. Bora reckoned that this transfer of surplus value was invaluable for the success of the British economy. In his analysis, he relied on Marx’s law of the falling rate of profit, namely that as the rate of profit fell domestically, British capital counteracted that with increased profits drained from India. Bora measured the drain of value from India to Britain using the ratio of the India’s nominal exports to nominal imports to and from the UK. He found that an increase in this colonial ‘drain’ of 1% increases the rate of profit of Britain by around 9 percentage points. So not only did colonialism help Britain but it was particularly the drain of resources from India that did so.

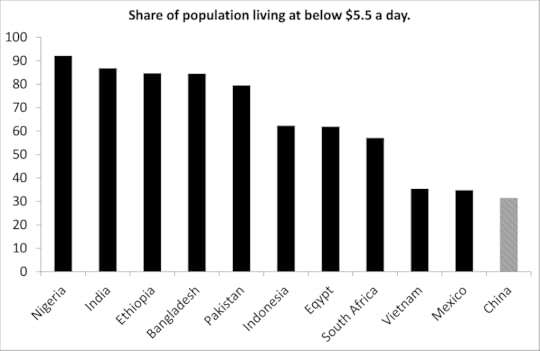

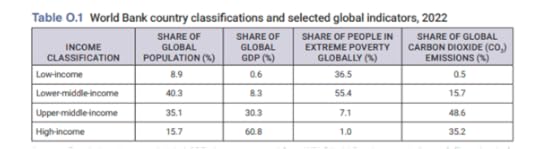

In her presentation, Patnaik concentrated on the failure to end poverty in the Global South. This failure was due to the exploitation of the poor countries by the Global North. She concentrated her remarks on the terrible levels of poverty based on measures of calorific intake. But she was also concerned to argue against the claim of China that it had got 800m Chinese out of poverty. That’s because China’s level of nutritional intake was also very low. On that criterion, China was really just as full of people in poverty as in India. And that’s because China was just as capitalist.

This argument was refuted from the floor: as China’s criteria for the poverty level is based on incomes and other categories of ‘well-being’ (food, clothing, education, medical support and safe housing). On those measures, China had way less poor people than India. Indeed, China’s poverty definitions more than match those of the World Bank and even the World Bank recognised China’s reduction in the number of those below the World Bank ‘higher threshold’ poverty level.

More disappointing was Patnaik’s proposed policy solutions for poverty in India and the global South. Following Keynes (not Marx), she reckoned governments needed to spend more money and run deficits to spend on alleviating poverty. Patnaik seemed to reject the ‘Chinese model’ and yet her own policy was unlikely to reduce poverty in India given the nature of the Modi government.

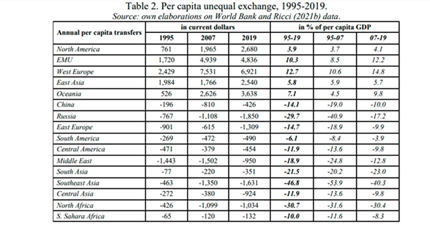

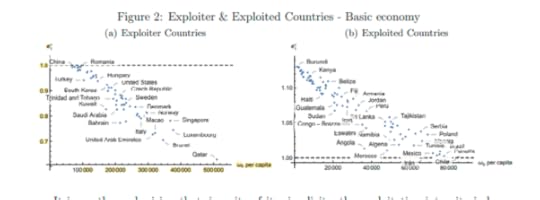

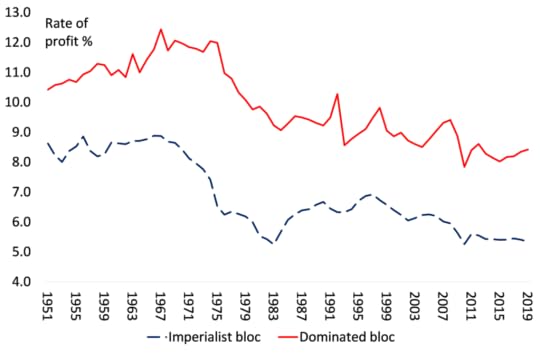

This brings me back to the question of whether China is capitalist and/or imperialist. I have discussed this at length in many posts on my blog and in papers and books. So I won’t go over the issue again here. Suffice it now to present some evidence against the idea that China is imperialist, or even ‘sub-imperialist’ ie it is exploited by the imperialist bloc, but at the same time exploits countries poorer than it (Africa?). Mino Carchedi and I have presented evidence on value transfers that show that China has made large transfers in value through trade and investment to the imperialist bloc.

Also Andrea Ricci of the University of Urbino, Italy has in the past shown a similar result. See this table of value transfers through unequal exchange in trade.

Robert Veneziani et al from the LSE, London also developed an ‘exploitation index’ for countries which showed that “all of the OECD countries are in the core, with exploitation intensity index well below 1 (ie less exploited than exploiting); while nearly all of the African countries are exploited, including the twenty most exploied”. The study put China on the cusp between exploited and exploiting.

So on all these measures of ‘imperialist exploitation’, China does not fit the bill, as least economically.

The great hope of the 1990s, as promoted by mainstream development economics was that Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa (BRICS) would soon join the rich league by the 21st century. That has proven to be a mirage. These countries remain also-rans and are still subordinated and exploited by the imperialist core. There are no middle-rank economies, halfway between, which could be considered as ‘sub-imperialist’. And that includes China.

Talking of China, there were several sessions on China organised by the IIPPE China working group. The sessions were recorded and are available to view on the IIPPE China You tube channel. The sessions covered China’s development model, its high investment in EVs and solar, and on the likelihood that China would ‘catch up’ with the US. In a workshop session, I and others presented short papers. Mine aimed at showing, contrary to the conventional wisdom of the West, that Chinese economic growth before Deng reforms in 1978 was very strong, based on public ownership of the finance sector and the large companies, land reform for the peasantry and above all, national planning. There were only two periods of decline (the disastrous Great Leap forward of 1958-61 and the so-called ‘cultural revolution of the late 1960s).

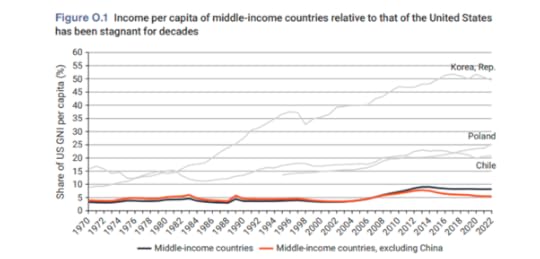

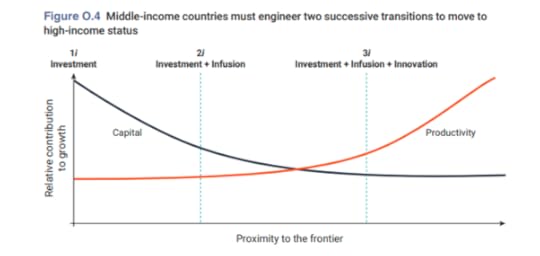

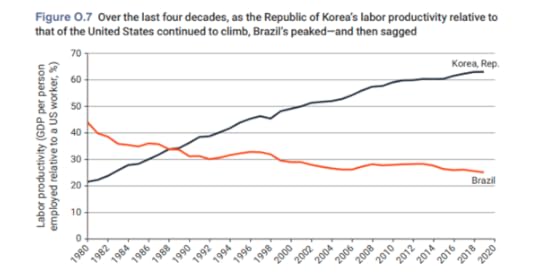

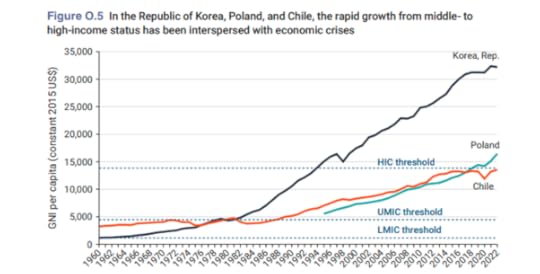

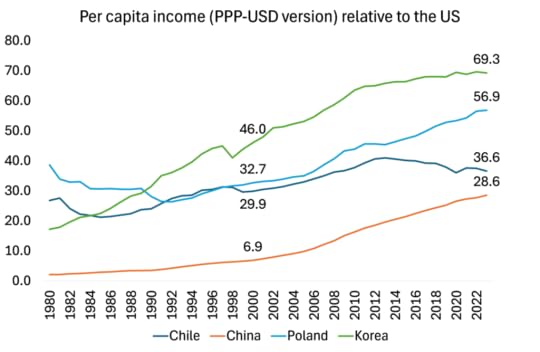

In his contribution, Professor Dic Lo of SOAS London made some telling points on the Chinese development model. And in a separate session, Dic Lo (China, the US and the Global South) referred to the recent World Bank report outlining the necessary conditions for economies in the Global South to break out what has been called the ‘middle-income trap’ and instead reach the living standards of the global North. The World Bank calls these conditions, the ‘three Is’: investment, infusion (taking in new technologies from other countries) and innovation (developing new technologies themselves). Dic Lo reckoned if there was one country that could apply these conditions successfully it was China. Only China was ‘closing the gap’ with the imperialist North, if still a long way behind.

Indeed that is what frightens the US – that it could eventually lose its hegemonic status in the world.

In a recent post, I discussed the World Bank report in detail. The report totally ignores the Chinese development model, preferring to put its hopes of ‘catching up’ in the relatively small capitalist market economies of Korea, Poland and Chile – just a tiny proportion of the world’s people and production compared to China. Even in these economies, there is a fundamental obstacle to achieve high income status as an important new book by Aldalmir Marquetti and colleagues explained.

What is that fundamental obstacle? Here is how Adalmir Marquetti put it: “it’s the falling profit rate that is the major determinant of decline in capital accumulation and investment. The problem is the profit rate approximates towards the level of the Unites States much faster than labor productivity. Essentially, the middle-income trap is a “profit rate trap”.

The problem for the Global South economies is that, as long as capitalism and the law of value remains dominant in their economies, there will be a contradiction between raising productivity and sustaining profitability: trying to raise the former leads to a fall in the latter and thus eventually limits growth.

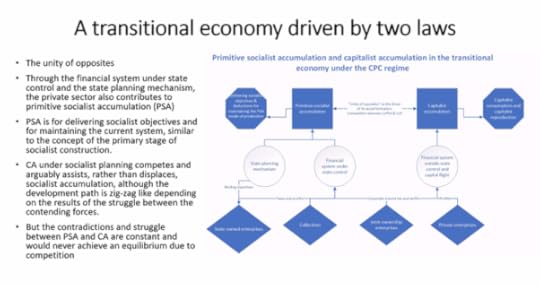

In another China session at IIPPE, this contradiction was well expressed by Sam Kee-Cheng of the University of Macau in her paper (Primitive socialist accumulation as contender development). Sam Kee-Cheng argued that China is a ‘transitional economy’ where the contradiction lies between an economy partly driven by capitalist accumulation for profit and partly by what Soviet economist Yevgeni Preobrazhensky called ‘primitive socialist accumulation’ which aims through planned investment to meet social objectives without the market.

Which will triumph: socialist accumulation or capitalist accumulation in China? If the latter, then Sam-Kee argued that China will not progress to high income status and will end up like Japan’s development model which came to a standstill once Japan ended its independent industrial strategy and bowed to US dominance.

Sergio Camara from the University of Mexico (UAM) raised a similar argument in his paper (Is China breaking with neoliberal dynamics?). Camara argued that China’s state-led economy was capable of meeting its targets for ‘catching up’ but much, he thought, depended on building cooperation with other Global South economies like the BRICS+. Otherwise , the world economy would slip into “a bipolar world with a hegemonic vacuum generating real dangers for the future”.

There were several other papers that showed the strides that China was making with its development model in EVs, autos in general (Fanqi Lin, A case study of China’s NEV industry). So successful has China been in these important sectors that, as one paper pointed out (Tomas Costa, FDI in China 2013-23), despite the efforts of the US and other Western governments to persuade or force Western investment to leave China, inward FDI remains high.

But there were other papers that showed the risk of failure due to the crises that the capitalist sector in China could get into. The most obvious was the collapse of the real estate sector and private developers leaving a huge debt burden on corporations and local governments (Alicia Giron). Adopting the Western model for urbanisation and housing in the 1990s to build homes for sales to owner occupiers, financed by mortgages and bond debt, turned for the worst – just as it did in the West in 2007-8 real estate meltdown. Giron argued that, while China would avoid ‘a Minsky moment’ ie a financial crash that the West suffered in 2008, it showed the dangers of ‘financialisation’ in the Chinese economy.

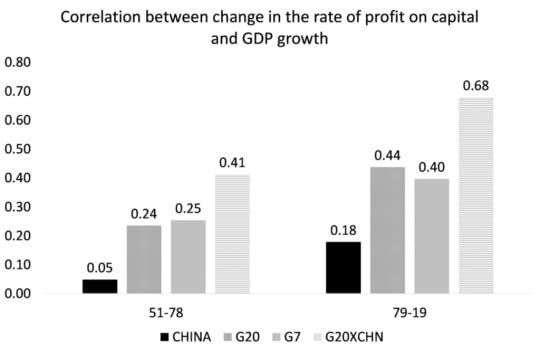

In this context, Zhenzhen Zhang produced an interesting piece of empirical work that showed a high correlation between investment in productive sectors and growth. Increased investment in unproductuve financial and real estate sectors over productive sectors had reduced China’s growth potential after 2008. And that is why the CPC leadership are now emphasising ‘quality’ productive investment from hereon.

Given the theme of this year’s IIPPE (ie imperialism and the world economy), it meant that other important subjects for Marxist political economy did not get much of airing. There were sessions on value theory and on the circulation of money capital (Takashi Satoh). And there were several papers presented on global warming and the rift between capitalist expansion and nature (Maria Pempetzoglou and Paraskevi Tsinaslanidou). There was also a paper by Joao Alcobia on the European Monetary Union which showed that the single currency had mainly helped the core of Europe (France, Germany) at the expense of the weaker southern member states. This is something I had noted some years ago in a paper.

But overall, the theme of the conference, at least to me, centred around whether the countries of the Global South could escape the the grip of imperialism and start to ‘catch up’. Was that to be achieved by relying on the emerging and disparate coalition of BRICS+ governments or will it depend more on breaking with capitalism in each country and developing a transitional model of accumulation not based on the law of value?

At the conference, clearly many hoped and supported the former direction based around BRICs+. Indeed, Andrea Ricci made a presentation on the political implications of unequal exchange (ie imperialist exploitation) and the need to find a common agenda among Global South countries. My view is that Global South cooperation will only work in breaking the grip of imperialism when there is social and economic change within the major countries of Global South (and also in the imperialist core of the Global North).

September 1, 2024

Germany: the end of EU hegemony?

Today, elections take place in two large provincial states (Lander) in eastern Germany All the opinion polls show that the Eurosceptic, anti-immigrant, Russia-friendly parties of both the extreme right and the new left are ahead. The parties of the current Federal coalition of the Social Democrats, Greens and the so-called Free Democrats are being decimated to the point of non-existence in these states of the former East Germany. The three eastern states combined are home to around 8.5 million people, making up 10 per cent of Germany’s population. But it is not just in these states that the ‘centre’ of German politics is collapsing. The three parties in Chancellor Scholz’s coalition government have seen their combined share of the vote fall from over 50 per cent at the end of 2021, to less than a third today.

In these Lander elections, the right-wing islamophobic Alternative for Deutschland (AfD) party is expected to poll over 30% share in Thuringia and Saxony, with the prospect of winning power in the former. Bjorn Höcke, who has already been convicted twice for using prohibited Nazi slogans, is the leader of the AfD in Thuringia. But also a new left-wing party, with its eponymous name the Sahra Wagenknecht Alliance (BSW), is expected to take up to 15-20% of the vote.

Germany is dealing with a spike in immigration as the number of asylum applications reached 334,000 in 2023. A recent poll found 56 per cent of Germans said they feared they could be overwhelmed by immigration. So it would appear that immigration and racism are the drivers of the rise of the extreme right AfD. But the irony is that the AfD vote improved mainly in areas in Eastern Germany where immigration was relatively low –it is the fear rather than the reality that drives such prejudice and reaction.

After all, Germans are used to immigrants. Germany is the second most popular migration destination in the world, after the US. Over one out of five Germans has at least partial roots outside of the country, or about 18.6m. But the question of immigration became a huge issue in Germany because of the disaster in the Middle East and Ukraine leading to a massive and fast influx of refugees, around 2m in the last two years into Germany. Most of these refugees were placed in the poorest parts of eastern Germany, already under the pressure of poorer housing, education and social services.

The other irony is that the co-leader of the AfD is no poor populist of the people, but instead Alice Weidel is a former economist at Goldman Sachs and financial consultant – shades of the UK’s Reform ‘populist’ leader Nigel Farage, who is a stockbroker. These representatives of capital have no connection with their rank and file voters, but attempt to rise to power on prejudice and mendacity. The phenomena of ‘populist’ right-wing nationalist parties is not confined to Germany. In France there is the National Rally, in the UK the Reform party and in Italy we have the Brothers of Italy actually in power. Indeed in nearly all EU states, there are parties of reaction polling around 10-15% of the vote as the recent EU Assembly elections confirmed.

For me, all this is a product of the Long Depression in the major capitalist economies since the end of the Great Recession of 2008-9, which has hit the the poorest and least organised of the working class, along with small businesses and self-employed. They have turned to ‘nationalism’ for an answer, thinking that the causes of their demise are immigrants, handouts to other EU countries and big business – in that order.

The situation has deteriorated most in Germany because of the after effects of the pandemic slump and the Ukraine war. The great manufacturing powerhouse of Europe, Germany, has ground to halt since the pandemic. And the votes for the traditional parties have dived with it.

The demise of the German economy has exposed the underlying issue of a ‘dual labour’ market with a whole layer of part-time temporary employees for German business on very low wages. About one quarter of the German workforce now receive a “low income” wage, using a common definition of one that is less than two-thirds of the median, which is a higher proportion than all 17 European countries, except Lithuania. This cheap labour, concentrated in the eastern part of Germany, is in direct competition with the huge numbers of refugees arriving in the last two years. So many voters of eastern German think that the problem is immigration.

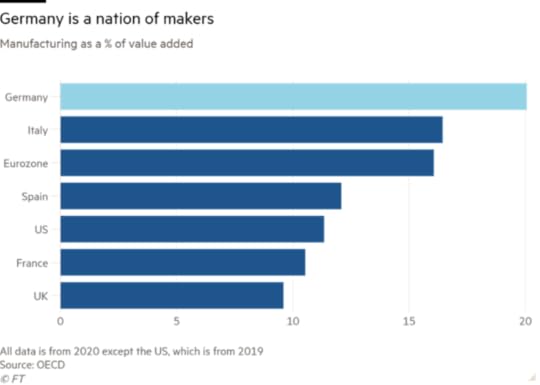

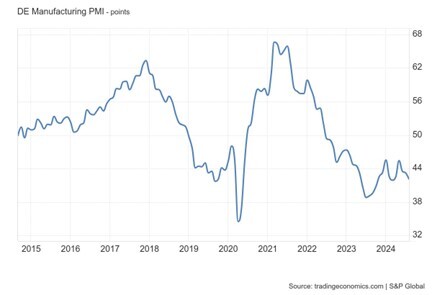

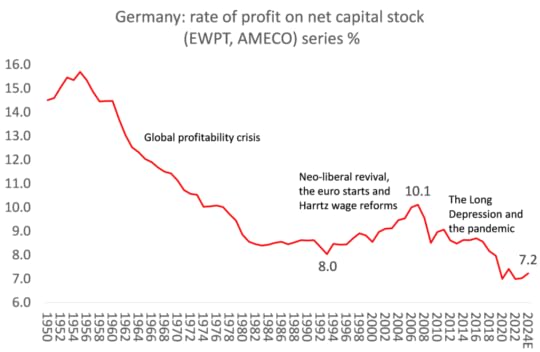

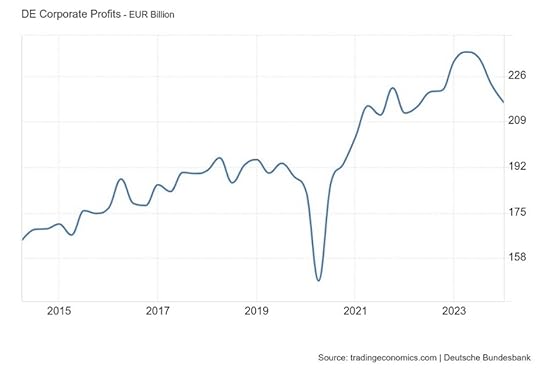

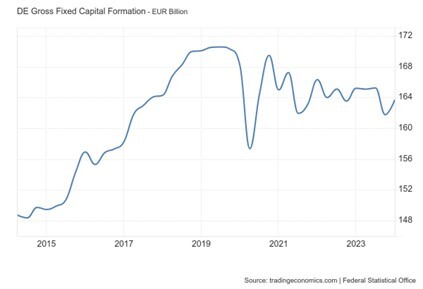

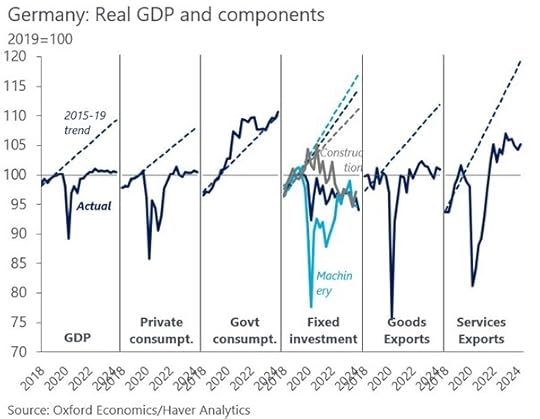

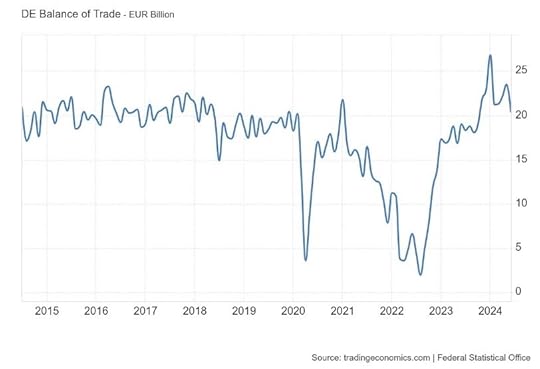

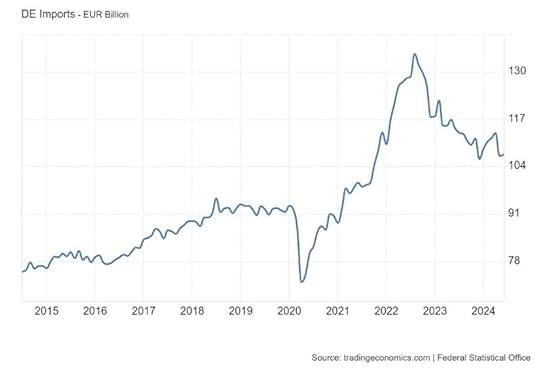

But beneath that is the deterioration of the German economy, particularly affecting the east. Germany is the EU’s most populous state and its economic powerhouse, accounting for over 20% of the bloc’s GDP. Manufacturing still accounts for 23% of the German economy, compared to 12% in the US and 10% in the UK. And manufacturing employs 19% of the German workforce, as opposed to 10% in the US and 9% in the UK.