Patrik Edblad's Blog, page 14

May 10, 2019

Survivorship Bias: How to Avoid Bad Advice

During World War II, the British military was losing their bomber aircrafts at an alarming rate.

As they were flying over enemy territory, they were being shot down so often that they decided to add armor to their planes.

But they couldn’t shield the entire surface of their aircrafts.

That would make them too heavy to take off.

So, they put the armor only in the most critical places.

Where Are the Bullet Holes?

To find out what those areas were, they carefully investigated the aircrafts that came back from battle and noted where they had been damaged the most.

The investigators found that the majority of the bullet holes tended to be on the wings, around the tail gunner, and down the center of the body.

Now, let’s imagine that you were in charge of the investigation.

With that information at your disposal….

Where Would You Put the Armor?

Most likely, you would want to do what the real commanders planned on doing.

They wanted to shield the parts that had the most bullet holes; the wings, the tail gunner, and the center of the body.

It seems like the obvious choice, but it would have been a terrible idea.

Why? Because remember; the investigators had only considered the aircrafts that survived their missions.

All the planes that had been shot down had not been taken into account.

So, what the holes in the examined aircrafts represented were the areas where the bombers could take damage and still make it home.

No Damage? Shield It!

Counterintuitively, it was the unharmed parts of the examined planes that needed the armor.

Because if those were hit, the aircraft would be lost, and it wouldn’t have shown up in the investigation.

Luckily for the British military, statistician Abraham Wald pointed all that out and helped them avoid a crucial mistake.

But in everyday life, we fall for the survivorship bias all the time, and it has significant implications on our judgment and decisions.

The Successful Dropout Myth

Consider, for example, the famous stories of how successful people like Richard Branson, Bill Gates, and Mark Zuckerberg all dropped out of school.

Learning about them, many people conclude that you don’t need a college education to succeed.

But for every Branson, Gates, and Zuckerberg, there are thousands, if not millions, of other entrepreneurs who dropped out of school and failed in business.

We just don’t hear about them, and so we don’t take them into account.

How to Counteract the Survivorship Bias

When you pay attention to the winners and ignore the losers, it’s difficult to say if a particular strategy will be successful.

So, whenever you’re presented with a success story, ask yourself if it provides a complete picture, or if it’s only taking survivors into account.

That way, you’ll make more accurate judgments and avoid bad advice.

The post Survivorship Bias: How to Avoid Bad Advice appeared first on Patrik Edblad.

May 3, 2019

Self-Serving Bias: How to Avoid Irrational Overconfidence

“If it worked, it was because of me. If it didn’t, it was because of someone or something else.”

This kind of reasoning takes place all the time and, on a psychological level, it makes sense.

We all feel a need to protect and build our self-esteem, and the self-serving bias helps us do that.

“It’s Not Me, It’s You”

Imagine, for example, that you’re trying to get your driver’s license.

If you pass your driving test on the first try, you’ll probably think it happened because of your excellent driving skills.

But if you fail, you’ll likely blame it on the incompetent examiner, the awful car, the bad weather or, well, pretty much anything else other than your own performance.

Studies on the self-serving bias have found that it shows up in a wide variety of situations, including:

School — If a student gets a good grade, it’s because of his hard work and intelligence. But if he gets a bad grade, it’s because of the poor teacher or the unfair test.Work — If a job applicant gets hired, it’s because of her qualifications. But if she doesn’t, it’s because the interviewer didn’t like her.Sports — If a team wins a game, it’s because of practice and skill. But if they lose, it’s because of the referee.

Internal Characteristics vs External Factors

We also consistently make what psychologists refer to as the “fundamental attribution error.”

When other people make mistakes, we blame the person. But when we make mistakes ourselves, we blame the circumstances.

Let’s say you’ve gotten your driver’s license (thanks to your excellent driving skills, of course), and you’re cruising down the highway when, suddenly, somebody passes you going well over the speed limit.

In this scenario, you’ll likely conclude that the other driver is a reckless jerk.

But if the roles were reversed, and you’re the one driving too fast, you’d probably blame the circumstances instead.

Unlike other drivers, you’re not some irresponsible maniac. If you’re speeding, it’s because situation, perhaps an emergency, warranted it.

Better Than Most

With these tendencies in mind, it’s no surprise we also rate ourselves more positively than others.

Research on what psychologists call “illusory superiority” shows that most of us consider ourselves better than average in school, at work, social settings, and many other situations.

Reasoning this way feels good. It helps us save face, hang on to our self-esteem, and avoid hurtful emotions like shame. But it also prevents our learning and growth.

If you blame your failures on the circumstances, there’s not much you can do about it. But if you accept responsibility for them, you can improve and do better next time.

How to Counteract the Self-Serving Bias

Be mindful of your tendencies to irrationally protect your self-esteem.

When you experience setbacks, resist the urge to pass the blame, and take ownership instead.

Don’t ask “Who’s fault is this?”, but “What can I learn from this?”

That way, you can continually course-correct, make wiser decisions, and get better results.

The post Self-Serving Bias: How to Avoid Irrational Overconfidence appeared first on Patrik Edblad.

April 26, 2019

Confirmation Bias: How to Avoid Errors in Judgment

Imagine that you’re taking part in a psychology experiment.

The experimenter gives you a three number sequence and informs you that these numbers follow a particular rule only she knows about.

Your task is to figure out what that rule is, and you can do that by proposing your own three number strings, and asking the experimenter whether they meet the rule.

The series of numbers you’re given is:

2-4-6

Try It!

What underlying rule do you think these numbers follow?

And what’s another string you can give to the experimenter to see if you’re right?

If you’re like most people, you’ll assume the rule is “numbers increasing by two” or “ascending even numbers.”

To find out if you’re right, you guess something like:

10-12-14

And, to your delight, the experimenter says: “Yes, that string of numbers follows the rule.”

To make sure that your hypothesis is correct, you propose another sequence:

50-52-54

“Yes!” the experimenter says, and you confidently make your guess about the underlying rule: “Even numbers, ascending in twos!”

But, to your surprise, the experimenter says, “No!”

It turns out that the rule is “any ascending numbers.”

So, 10-12-14 and 50-52-54 fit the rule — but so does 1-2-3 or 9-748-1047.

Don’t Confirm — Disconfirm

The only way to figure that out is to guess strings of numbers that would prove your beloved hypothesis wrong — and that’s not something that comes naturally to us.

In the original study, only one in five participants guessed the correct rule.

The 2-4-6 task beautifully illustrates our bias toward confirming, rather than disproving, our ideas.

And that tendency has a massive influence on how we interpret information, form beliefs, and make decisions.

Consider, for example….

The Global Warming Controversy

Let’s say Mary believes climate change is a serious issue.

Because of that, she seeks out and reads stories about how the climate is changing.

As a result, she continues to confirm and support those beliefs.

Meanwhile, Linda does not believe that climate change is a serious issue.

Because of that, she seeks out and reads stories about how climate change is a hoax.

As a result, she continues to confirm and support those beliefs instead.

Confirming is Comfortable

The confirmation bias makes us pay attention to what supports our views and dismiss what doesn’t.

And the more convinced we become about something, the more we’ll filter out and ignore all evidence to the contrary.

It feels much better to support our beliefs than it does to discredit them.

Evaluating and adjusting our worldview is scary, uncomfortable, and strenuous. So we prefer strengthening it instead.

The confirmation bias helps us do that. But it does so at the expense of clear judgment.

Counteract the Confirmation Bias

To keep an open, flexible, and rational mind, you have to continually challenge what you think you know.

You need to deliberately seek out disconfirming evidence and always be ready to change your mind.

It’s not easy, but with practice, it will make you much better at interpreting information, updating your beliefs, and making well-informed decisions.

The post Confirmation Bias: How to Avoid Errors in Judgment appeared first on Patrik Edblad.

April 19, 2019

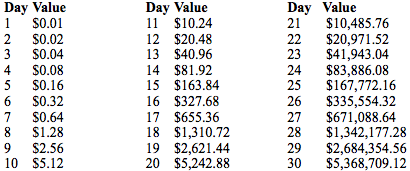

Compounding: How to Create Massive Change in Your Life

Imagine that you’re given a choice right now.

You can get either $3 million in cash immediately, or a penny that doubles in value every day for the next 30 days.

Which option would you choose?

Most people would take the $3 million.

So, let’s say you do that, and I get the penny.

$3 Million vs. 1 Penny

At the outset, you’ll have every reason to be happy with your choice.

After one week of compounding, my penny is worth a meager 64 cents.

After two weeks, it’s at a modest $81.92.

And after three weeks, I’m still way behind you.

Sure, the penny has transformed into a respectable $10,485.76, but that’s still not much compared to your $3 million.

But then, a few days into the third week, something starts to happen.

The Magic of Compounding

On day 28, the penny has grown into a remarkable $1,342,177.28.

On day 29, I’m right behind you with $2,684,354.56.

And on day 30, I finally pull ahead as my stack of cash compounds into an astonishing $5,368,709.12.

The compounding penny illustrates something that our brains have a hard time to grasp intuitively:

Small Improvements Accumulate Into Massive Changes

And this is just as true in life as in finance. In his book, Atomic Habits, James Clear explains:

Here’s how the math works out: if you can get 1 percent better each day for one year, you’ll end up thirty-seven times better by the time you’re done. Conversely, if you get 1 percent worse each day for one year, you’ll decline nearly down to zero. What starts as a small win or a minor setback accumulates into something much more. Habits are the compound interest of self-improvement.

Whenever you make a choice, like ordering a salad instead of a hamburger, that single occasion won’t make much of a difference.

But as you keep repeating the same decisions and actions over weeks, months, and years, they will compound into huge results.

If you hit the gym three times for a week, you won’t get any noticeable results (except maybe some soreness). But if you keep showing up just as often for a year, you’ll accumulate 150+ hours of exercise. That’s more than enough to have a significant effect on your health and fitness.

If you read one good book, that won’t make much of an impact on your thinking. But if you read one every month for a year, you’ll finish 12 titles. That will give equip your mind with plenty of new mental models to improve your thinking.

If you meditate a couple of times, it probably won’t create any lasting changes. But if you do it for 10 minutes each day for a year, you’ll have 60+ hours of meditation practice. And that will most likely have considerable positive effects on your health, well-being, and performance.

Tiny Improvements Are Immensely Powerful

So, instead of looking for big wins, start small.

Focus on consistency over intensity.

Allow compounding to work its magic and, over time, it will create remarkable outcomes.

The post Compounding: How to Create Massive Change in Your Life appeared first on Patrik Edblad.

April 12, 2019

Algorithms: How to Program Yourself for Good Decisions

In his book, Homo Deus, historian Yuval Noah Harari writes:

Algorithm’ is arguably the single most important concept in our world. If we want to understand our life and our future, we should make every effort to understand what an algorithm is, and how algorithms are connected with emotions.

So, what is an algorithm?

The dictionary defines it as “a process or set of rules to be followed in calculations or other problem-solving operations, especially by a computer.”

If you’ve ever wondered how a Tesla can drive itself, the answer is algorithms — millions of them.

But there are also more relatable, everyday occurrences of algorithms.

Each time you bake a cake, for example, the recipe you use is an algorithm.

Mental Algorithms

Interestingly, psychologists have found that you can also use algorithms to program yourself for better decision making.

Psychology professor Peter Gollwitzer refers to this strategy as “if-then planning,” and to use it, all you have to do is fill out this simple formula:

If [situation] – Then I will [behavior].

The beauty of if-then planning is that it forces you to turn vague intentions into clear algorithms.

“I want to eat healthier” becomes “If I’m buying lunch, then I will order a salad.”

It sounds ridiculously simple, but don’t let that fool you.

The Power of If-Then Planning

More than 200 scientific studies show that if-then planners are about 300% more likely to achieve their goals.

The reason it works so exceptionally well, according to psychologist Heidi Grant, is that:

“Contingencies are built into our neurological wiring. Humans are very good at encoding information in “If X, then Y” terms, and using those connections (often unconsciously) to guide their behavior.”

In other words: Much like computers, our minds respond very well to algorithms.

If-then plans allow you to act the way you want without thinking, and that saves a lot of mental energy for other decisions.

Instead of hesitating and deliberating, you just follow the algorithm whenever the situation arises.

Create Your Own Algorithms

Rather than relying on vague intentions, purposely install the responses that will lead you to your goals. Here are some examples:

“I want to move more.” → If I’m at work, then I will take the stairs.“I want to be more productive.” → If I arrive at the office, then I will do two hours of deep work.“I want to improve my relationships.” → If I come home from work, then I will share the best thing that happened to me that day.“I want to be happier” → If I wake up in the morning, then I will think about one thing I’m grateful for.

Think of yourself as a robot and the if-then plans as the algorithms you use to program yourself.

It seems silly, I know, but it’s a remarkably effective way of putting good decisions on autopilot.

April 5, 2019

Homeostasis: How to Enable Big Changes in Your Life

What’s the temperature where you are right now?

Most likely, it’s not precisely 98.6 ºF (37.0 ºC).

Still, your body temperature is probably very close to that value.

In fact, if your core body temperature doesn’t stay within a narrow range — from about 95 ºF (35.0 ºC) to 107 ºF (41.7 ºC) — the results can be dangerous or even deadly.

So, as you’re reading this, every cell in your body and brain are working to maintain a sense of stability.

Not just in your core body temperature, but also in blood pressure, heart rate, pH balance, blood glucose levels, and many other factors critical to your survival.

This tendency maintain internal stability — this resistance to change — is called homeostasis, and the human body is just one example of where it takes place.

Homeostasis is Universal

In his book, Mastery, George Leonard writes:

“[Homeostasis] characterizes all self-regulating systems, from a bacterium to a frog to a human individual to a family to an organization to an entire culture—and it applies to psychological states and behavior as well as to physical functioning.”

Psychologically, we maintain homeostasis through mental patterns like the status quo bias — our tendency to prefer that things stay as they already are.

Socially, we remain stable through forces like conformity — our propensity to maintain attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors congruent with the group.

Here’s an Example

Imagine that for the last ten years or so, you’ve been almost entirely sedentary.

But then, one day, you decide to go for a run.

The first few steps are enjoyable, but that quickly changes.

After a couple of minutes, you feel lightheaded.

Moments later, you feel sick to your stomach.

And if you keep going, soon enough, you’ll feel like if you don’t stop, you might just drop dead.

These symptoms are essentially homeostatic alarm signals.

Your body has detected changes in respiration, heart rate, and metabolism that are way outside the normal range.

To bring them back, your body screams at you:

“Warning! Warning! Whatever you’re doing, stop it immediately, or you’re going to die!”

And that’s just one way that homeostasis gets in the way of your new fitness goal.

On a psychological level, you’ll probably experience resistance every time you think about putting on your running shoes.

And on a social level, your sedentary friends might not welcome your new exercise habit.

Leveraging Homeostasis

Needless to say, homeostasis makes it difficult to create change.

It’s a powerful force that often results in backsliding.

But the good news is that if you keep pushing, homeostasis will eventually adapt to the new load and create a new set point.

If you keep showing up at the trail, your body will eventually get used to the running, and even begin to crave it.

Being a runner will become part of your self-image, and you’ll experience resistance if you don’t go running.

And, with time, your friends will get used to this crazy habit of yours — and some of them might even join you.

So, whenever you make a decision that requires a big change, expect homeostasis to kick in.

Know that there will be backsliding, and keep on pushing.

Eventually, homeostasis will adapt and start working for you.

And from that point forward, it will become much easier.

The post Homeostasis: How to Enable Big Changes in Your Life appeared first on Selfication.

March 28, 2019

Conformity: How to Become Who You Want to Be

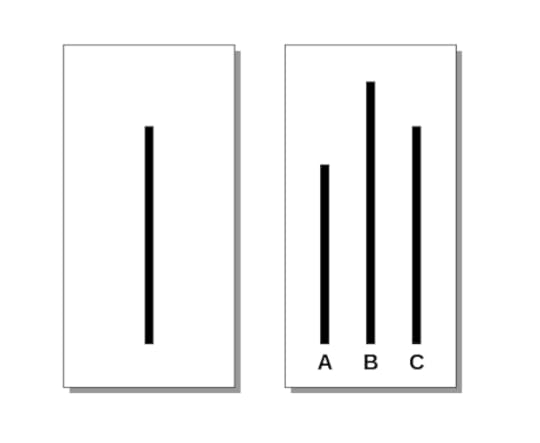

In the 1950s, psychologist Solomon Asch conducted a series of experiments to investigate the power of social pressure.

At the start of each experiment, a participant entered a room with a group of strangers.

The subject didn’t know it, but these people were actors pretending to play other participants.

The group was then given a simple task.

First, they were shown one card with a single line on it and a second card with a series of lines.

Then, each person was asked to point out the line on the second card that was the same length as the line on the first card.

The Asch Conformity Experiments

Initially, there were some easy trials where the entire group agreed on the same line.

But after a few rounds, the actors would deliberately select what was obviously an incorrect answer.

The bewildered subject then had to decide whether to trust their own judgment or conform to the group.

Asch ran this experiment several times in many different ways, and what he found was that as he increased the number of actors, so did the conformity of the subject.

One or two other “participants” had little impact.

But as the number of actors increased to three, four, and all the way up to eight, the subject became more likely to give the same answer as everyone else.

Overall, 75 percent of participants gave an incorrect answer at least once.

In the control group, where there was no pressure to conform to actors, the same error rate was less than 1 percent.

How Could That Be?

Human beings are social creatures with a deep need for belonging.

The reward of being accepted is usually more significant than the reward of being accurate.

So, for the most part, we’d rather be wrong in a group than right by ourselves.

As a species, we are ill-equipped to live on our own, so the human mind has evolved to get along with others.

Because of that, we experience tremendous internal pressure to comply with the norms of the group.

And, as a result, we tend to conform to those around us.

It’s a very natural thing to do, and there’s nothing inherently wrong with it.

But there can be severe downsides to this tendency.

If you’re not mindful of it, your intentions can get consistently overpowered by the prevailing group norms.

Consider, for Example, Sleeping Habits

Research shows that one-third of the American population is sleeping less than six hours per night.

As a result, at least 50 percent of the adult population is chronically sleep deprived.

Depriving yourself of sleep is a terrible decision.

Insufficient sleep ruins your health, performance, and well-being.

Still, this devastating trend is taking place throughout the industrialized world.

There’s a prevailing norm that sleep is a luxury rather than a necessity.

And as the people around you conform to it, you’ll likely do it, too.

The Takeaway

If something seems like the normal thing to do, you’ll gravitate toward it — regardless of the outcome.

So, to become who you want to be, you need to find the right social group.

Surround yourself with people who consistently make the choices you want to make, and the way they do things will soon become the way you do things.

The post Conformity: How to Become Who You Want to Be appeared first on Selfication.

March 22, 2019

Nudging: How to Effortlessly Make Better Decisions

In their book, Nudge, Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein explain that small and seemingly insignificant details in the environment can have a big impact on people’s choices and behaviors:

A wonderful example of this principle comes from, of all places, the men’s rooms at Schiphol Airport in Amsterdam. There the authorities have etched the image of a black housefly into each urinal. It seems that men usually do not pay much attention to where they aim, which can create a bit of a mess, but if they see a target, attention and therefore accuracy is much increased.

The result? According to economist Aad Kieboom, who came up with the urinal fly idea, these simple etchings reduce spillage by 80 percent!

That’s a remarkable result, and a great illustration of the power of “nudging”: small, simple, and inexpensive changes to the environment which increase the likelihood that people will make certain choices or behave in particular ways.

Researchers have found several effective nudging techniques, including:

Default option — People are more likely to choose whatever is presented as the default option. For example, one study found that more consumers chose renewable energy for electricity when it was offered as the default choice.

Social proof — People tend to look to the behavior of other people to help guide their own. Studies have found that leveraging that tendency can be a helpful way to, for instance, nudge people into making healthier food choices.

Salience — People are more likely to choose options that are more noticeable than others. For example, one study found that snack shop consumers buy more fruit and healthy snacks when those options are placed right next to the cash register.

The beauty of nudging is that it allows you to make smarter decisions and take better actions without even thinking about them.

You simply shape your environment, and then let your environment shape your decisions.

Here are some examples of how you can use this strategy in your life:

If you want to start flossing, put pre-made flossers in a cup next to your toothbrush.

If you want to practice the guitar more often, place your guitar stand next to your living room couch.

If you want to lose weight, store away your big plates, and serve yourself on salad plates instead.

If you want to read more, put a great book right on top of your favorite pillow.

If you want to be more productive, use an app like Freedom to block distracting websites.

We tend to assume that good decisions require conscious effort, and that healthy behaviors requires strong willpower.

But a lot of the time, all you need is a slight nudge in the right direction, and the rest will take care of itself.

So, take a look at your environment, and ask yourself: “How can I make good choices easy, and bad choices difficult?”

The post Nudging: How to Effortlessly Make Better Decisions appeared first on Selfication.

March 14, 2019

Hanlon’s Razor: How to Be Less Judgmental and More Empathetic

Do you ever feel like the world is against you? If so, you are not alone. We all tend to assume that when things go wrong, it’s because the people in our lives are conspiring against us.

Your colleague didn’t tell you about an important meeting? He must be trying to make you look bad and beat you to the promotion.

Your friends meet up without inviting you? They must be going behind your back because they don’t like you anymore.

Your kids put finger paint all over your kitchen wall? They must be trying to drive you insane.

But in reality, these explanations aren’t very likely to be true. It’s much more probable that your colleague simply forgot to tell you, that your friends assumed you were busy, and that your kids have yet to learn the difference between a kitchen wall and a canvas.

And that’s why Hanlon’s razor is such a handy tool.

Hanlon’s razor is an adage, coined by Robert J. Hanlon, which is best summarized: “Never attribute to malice that which can be adequately explained by neglect.”

It’s essentially a special case of Occam’s razor, which states that “Among competing hypotheses, the one with the fewest assumptions should be selected.”

In a situation where something can be explained either by malice or neglect, the latter is more likely.

Malice is a big assumption, but negligence is not. People rarely have genuinely bad intentions, but they make mistakes all the time.

And by applying Hanlon’s razor in our interactions with others, we can negate the effects of many of our cognitive biases. For example:

The Fundamental Attribution Error — We tend to blame the mistakes of others on their personality, and our own mistakes on the circumstances. If someone else is driving too fast, it’s because they’re an inconsiderate idiot. But if we’re the one who’s speeding, it’s because the situation warrants it. Hanlon’s razor helps us assign situational reasons to everyone’s mistakes — not just our own.

The Availability Bias — We often misjudge the frequency of recent events, especially if they’re vivid and memorable. Many of us keep a mental scorecard of other people’s mistakes. When a new mistake is made, it’s magnified by errors in the past, and we start imagining malicious intent. Hanlon’s razor helps us see each mistake as an isolated occurrence.

The Confirmation Bias — We have a tendency to seek out information that confirms our pre-existing beliefs. If we expect malicious intent, we are likely to attribute it whenever possible. Hanlon’s razor helps us stop looking for confirming evidence so we can accurately identify honest mistakes.

So, whenever you feel mistreated, keep in mind: “Never attribute to malice that which can be adequately explained by neglect.”

It will make you less judgmental and more empathetic. You’ll be able to give other people the benefit of the doubt. And that will make for better relationships and a lot less stress.

Of course, there are people out there who do have malicious intent, and that needs to be taken into account. You don’t want to be blind to behavior that is intended to be harmful.

But, as a rule of thumb, assuming neglect before malice will make you more accurate in your judgments — and a better fellow human.

The post Hanlon’s Razor: How to Be Less Judgmental and More Empathetic appeared first on Selfication.

March 8, 2019

Occam’s Razor: How to Be a Better Problem Solver

William of Occam was a 14th-century English friar, philosopher, and theologian. He’s considered one of the prominent figures of medieval thought and was involved in many major intellectual and political controversies during his time.

William is most commonly known for the methodological principle called Occam’s razor. He did not coin the term himself, but his way of reasoning inspired other thinkers to develop it.

Occam’s razor is basically a rule of thumb for problem-solving which states that: “Among competing hypotheses, the one with the fewest assumptions should be selected.” Another way of putting is that the simplest solution is probably correct.

Using Occam’s razor, you “cut away” what’s excessively complex so you can focus on what works. This approach is used in a wide range of situations to improve judgment and make better decisions. To understand how, let’s have a look at a few examples.

Science

Many great scientists have used Occam’s razor in their work. Albert Einstein is one of them. His version of the same principle was: “Everything should be made as simple as possible, but not simpler.” This preference for simplicity shows in his famous equation E=MC2. Rather than settling for a complex, lengthy equation, Einstein boiled it down to its bare minimum.

Medicine

Medical interns are often instructed: “When you hear hoofbeats, think of horses, not zebras.” The underlying idea is to always consider obvious explanations for symptoms before turning to more unlikely diagnoses. This version of Occam’s razor helps reduce the risk of over-treating patients or causing dangerous interactions between different treatments.

Crime

By using a combination of statistical knowledge and experience, Occam’s razor can be used in solving crimes. For example, women are statistically more likely to be killed by a male partner than anyone else. So, if a woman is found in her locked home murdered, the first person to look for is any male partners. By focusing on the most likely perpetrators first, the police can solve crime more efficiently.

As a mental model, Occam’s razor works best for making initial conclusions with limited information. To use it, you compare the complexity of different options and favor the simplest one. Imagine, for example, that you come home one day and find that your living room window is open. This surprises you, as you’re usually very diligent in closing it. There are two possible explanations for this:

You had a lot on your mind when you left and forgot to close it.Someone has broken into your home while you were away.

The first explanation only requires a little mindlessness on your part. The second explanation, however, means someone had to open your window from the outside, disarm your alarm, avoid detection by neighbors, clean up behind them, and leave just as quietly as they came. Therefore, in the absence of any evidence to the contrary, the first explanation is the simplest and the most likely to be correct.

Occam’s razor obviously isn’t perfect. There are exceptions to every rule, and you should never follow them blindly. But, in general, favoring the simple over the complex will improve your judgment and help you solve problems faster and better.

The post Occam’s Razor: How to Be a Better Problem Solver appeared first on Selfication.