Sarah Cypher's Blog, page 11

November 24, 2011

Holiday gratitude giveaway: Win a literary book bundle!

Dear friends, clients, fellow writers, and readers:

In honor of this year's holiday season, I'd like to say thank you for what you add to my life and editing business, The Threepenny Editor. I count myself lucky beyond reason for the chance to work every day with people who are as committed to books, writing, learning, and ideas as you all are.

As a gesture of my appreciation, I am giving away one set of my favorite six books on writing:

The Art of Dramatic Writing , by Lajos Egri

The Art of Fiction , by John Gardner

Bird by Bird , by Anne Lamott

The Elements of Style , by William Strunk and E. B. White

Manuscript Makeover , by Elizabeth Lyon

The Editor's Lexicon , by Sarah Cypher

What do you need to do? Just share in the comments section your answer:

What are the writing accomplishments you're thankful for this year, and your goals for next year?

The contest is running on this blog and my business blog, and at midnight on December 15, I'll combine all the comments from both, and use a random number selection to pick the winner. Good luck!

November 16, 2011

An open question about speculative fiction.

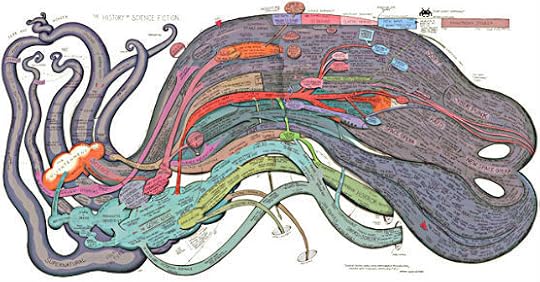

Click for a link to a high-res version of Ward Shelley's brilliant "The History of Science Fiction." I love this image so much that I hung it over my desk.

In an earlier post, I ventured a functional definition of speculative fiction. I said that a manuscript is "speculative" (i.e., fantasy, sci-fi, or anything in between) if it requires the writer to invent a rule or condition for their world that acts as a metaphor for the novel's theme. In other words: If you make something up, that something has to offer the reader a clue to what the book is about. Otherwise it's gratuitous.

Yet as I plan my next novel, I am reminded of Occam's Razor, which says that the simplest explanation for anything is usually the truest one. The problem with my earlier definition is that it doesn't always work; there are lots of books about dragons, fairies, and/or outer space that use speculative elements just for the fun of it. Some readers like to read about dragons, for instance, so a market exists for writers who enjoy telling dragon stories. Simple as that. There is no rule that says all dragon stories must be important social commentary.

So let me try a simpler definition. Where all fiction involves five basic elements–premise, theme, voice, character, plot, and style–speculative fiction also involves a sort of sidecar to premise: the concept.

So, if premise is what the story is about in a few simple sentences, the concept is the invented-but-believable element that separates the story world from reality. The concept could be anything: vampires and why they exist (Interview with a Vampire), a medieval world inhabited by dragons (The Dragonbone Chair), a future America in which fertile women are required to reproduce (The Handmaid's Tale), or a alter-reality in which Irish immigrant spirits are at war with Native American spirits (Forests of the Heart). If your novel uses a concept, then it has a speculative element. Simple as that.

So, here's my question. What is the difference between realist fiction and speculative fiction?

And a bonus question: Where is the line that separates books shelved in a store's "general fiction" section and its "sci-fi and fantasy" section?

November 14, 2011

Sunburned, sore, and satisfied

I said I would never run a marathon. Marathons are long, bad for the knees, unnecessarily strenuous, require a lot of training time I don't have… And as it turns out, they're a healthy way to feel satisfied with one's progress. So I ran one. It hurt. And I'm happy about it.

My father belongs to the school of thought that there is no point in doing anything without tangible benefit to one's family or society. This includes going back to school for the fun of it, running marathons, or having hobbies. I must have inherited some of his sense of productivity, but not the discipline to see it through. If you can't pass your DNA down to your kids, the last resort of human significance tends to be work. Work–and life–are not satisfying unless they allow you to be creative. To be curious and knowledgeable and practical and clever all at once, in a single inventive spark.

Running a marathon is still its own thing. It's usually ugly and smelling and shambly. It has no higher purpose unless you invent one for it. You can stay healthy on far less exercise. There's a study out there somewhere that says exercise reduces your cognitive function to 2 percent of its normal capacity because the rest of your body is screaming for the oxygenated blood normally reserved for your brain. And as a social event, well, as one little girl's sign proclaimed from yesterday's crowd, a marathon is the "Worst Parade Ever."

And yet, you still wake up with the satisfaction of having done something that is somehow good. It is a shared memory with my wife and her family, who ran it with us. It got me out of my chair. For someone in a creative profession, where some much of one's success depends on luck and other people's judgment, it's also nice to set out at 8 a.m. and achieve a pervasive sense of completion by noon of the same day.

And really, best of all, after running for over four hours in the sun and humidity: cold water and fresh bread never tasted so good.

November 7, 2011

To love better.

Flowers from E.

I'm 31 today. Every birthday, I write wishes for the coming year on a slip of paper and then stuff it inside a tiny metal owl on my desk. One of my wishes this year is to love better.

I mean love everything better. Not pick it apart as a corporate conspiracy or a self-replicating cultural mistake. Not rush to find the right word for it. As I research the next novel, I am more aware than ever that knowledge requires words, categories, differences, hierarchies. The problem, however, is that when used without perspective or care in politics, a little bit of knowledge does nothing but underscore the differences between people.

The very best emotion you can bring to the act of acquiring knowledge is curiosity. Any other emotion creates a bias. Art doesn't like bias, either–though there is a fundamental difference between art and knowledge. You can't jump straight from knowledge of a subject to an artistic rendering of it. Art happens when you shut your eyes and smear away the words, and quietly observe what impressions remain. Good art requires knowledge, but the quietness and listening… Those are acts of love. An attitude of love is a gateway to art.

For my birthday this year, my parents gave me a piece of art that I admired at San Antonio's Uptown Art Stroll; I loved that it rendered the image of St. George–beloved from the holy icons of my childhood in the Orthodox Church–in a collage using found art and warm, earthy acrylics. The saintly meets the earthly here, and somehow, it speaks to this same mysterious gateway between mind and spirit.

Art from Mom: St. George by Jorge Garza

This year, I wish for lots of quietness and listening, those two loving midwives of the creative soul. I wish it for everybody. I also wish:

To look at art more often.

To resume Spanish.

To see my family as often, or more so.

To make the trips I have in mind.

To master the art of attitude adjustments. (See above.)

What else? I always wish for writing to go well. Loving better is a means to two ends: a happy day-to-day home life, and a happy year-to-year growth of my writing skills. Last week I spoke to a literary agent about what I can do better, and she advised that I keep asking myself, "Why speculative fiction?" My training is in realism, but my heart lies in the imaginative power of storytelling. This year, I want to get better at finding the gateway between knowledge and art.

In the same vein, here are a few lines from Jane Hirshfield's new collection of poetry.

FRENCH HORN

For a few days only,

the plum tree outside the window

shoulders perfection.

No matter the plums will be small,

eaten only by squirrels and jays.

I feast on the one thing, they on another,

the shoaling bees on a third.

What in this unpleated world isn't someone's seduction?

…

November 2, 2011

A Reader's Paradise: Review of Diana Abu-Jaber's "Birds of Paradise"

Birds of Paradise: A Novel by Diana Abu-Jaber

Birds of Paradise: A Novel by Diana Abu-Jaber

This is one of the most absorbing novels I've read all year; as in, it made a flight pass quickly, and then later, at home, drew me back to my big comfy office chair for another chapter when I really should have been working.

The story is straightforward. In the days leading up to Hurricane Katrina's landfall in Miami, Avis, an artisan baker, is forced to confront her role in her daughter's disappearance almost four years ago. The novels POVs rotate between Avis, her attorney husband, and her daughter, who's living on the Miami streets.

With such strong echoes of Carol Shields's Unless (both hinge on a daughter who runs away from a good home in response to a secret tragedy), I worried that no book could upstage Shields's masterpiece. But it manages to settle into its own space, marrying plot and transcendent writing that expands rather than competes with the theme of fraught relationships between successful mothers and daughters maturing into womanhood.

What I find so fascinating–and so authentic–about Diana Abu-Jaber's writing is her ability to bury the story tension almost out of sight beneath her trademark lyrical prose. The result is tension that runs beneath everything, illuminating even the solitary kitchen scenes like a grid of electric wires. I've read all of her novels, and each one takes her writing down further from its airy, almost magical realist beginnings (think the climactic scene of Arabian Jazz) to the earthy, almost static pace of real life. Yet each somehow serves to tell an even more compelling story, made more powerful by the confident but subtle connections between characters and their big-picture social responsibilities–everything from labor conditions in the Haitian sugarcane industry to urban gentrification and real estate speculation. It reminds me of what worked so well in Jennifer Egan's Look at Me, another of my favorite reads this year.

As a reader, I can't wait for the next novel. As a writer, all I can say is–her students are a lucky bunch.

New blog design launched!

Every good home needs an occasional freshening up. As I twine a garland of autumn leaves around the pillars of front porch and set out pumpkins in anticipation of Thanksgiving, I invite the changing season to bless our house with its lively hand–and likewise, I am just as excited about the spruced-up design of this blog by my literary cohort and web guru, Julia Stoops of Blue Mouse Monkey.

Thank you, Julia!

What's your new novel about?

SHAHIDA is set in the near-future Gaza Strip. It combines the brisk pace of Middle Eastern mysteries such as Zoe Ferraris's City of Veils and Matt Rees's A Grave in Gaza with the intense, interior narration style of Margaret Atwood's The Handmaid's Tale.

Shunned by her family, Rabia, a disgraced young mother, starts class in Gaza City's "women's education program"—a school that trains women as wives, and marries them to graduating men. She needs the marriage to regain custody of her infant daughter, but faces the danger of jail or stoning if she violates the land's strict, unfamiliar laws.

Yet the school has a covert agenda. Because Rabia already has a child, making her an unlikely candidate for marriage, the dean compels her to join a political club for women. In the club, she embarks on a secret double life that puts her in more danger, but offers hope of eventual escape. She discovers that the women in the club are being trained as shahidat, suicide bombers; but once in, Rabia cannot leave lest she be stoned as a collaborator, and leave her daughter motherless.

Her only escape is a fellow student who offers to help her in exchange for favors to an underground organization. The favors become more dangerous—but also lead to Sami, a resister whom she must learn to trust if she is to survive. As the price of her escape, they make a daring effort to expose the school's covert agenda, and start a chain reaction that could forever change the land where veils hide all, and where every personal act is also political.

I write about the Middle East because of man's inhumanity to man. This border crossing exists, and it's hardly the worst.

October 28, 2011

Who's Controlling YOUR Internet?: A Review of the Book You Don't Know You Need to Read

Who Controls the Internet?: Illusions of a Borderless World by Jack L. Goldsmith

Who Controls the Internet?: Illusions of a Borderless World by Jack L. Goldsmith

My rating: 4 of 5 stars

Written accessibly by a Harvard law professor and one from Columbia, this is the kind of "new history" that should probably, soon, become an essential part of our standard education about the world. It explains how the Internet came to be, why it failed as a truly borderless space, and how and why meatspace issues such as censorship, commerce, politics, and even warfare have begun to duplicate themselves in cyberspace.

Although published in 2006, this book is worth talking about now for two reasons. First, it's interesting. I have been studying power and coercion for a while, and these ought to be issues relegated to the physical world, a.k.a., meatspace. The body is the ultimate place of enforcement. Without the threat of pain or imprisonment, there is no ultimate consequence to lend force to a demand. The Internet's early popularity in the late 80s and early 90s was due in part to the recognition that cyberspace was different: there was no such thing as a painful consequence. When people organized themselves there, they did it anarchically, and the system worked because no one could aggregate disproportionate force.

Which brings me to the second reason why the book is important. The Internet's history ought to be taught in classrooms: It has founders, inventors, competing systems of governance, and international drama. For instance, the Internet's early anarchic structure failed when the U.S. government reasserted its rights to the root servers (citing that the Internet's invention in the 60s was funded by a DARPA contract). The reason was money. Capitalism. Now is an opportune time to mention that I believe that history, as a course of study, exists to give us perspective on why we do what we do, and why our environment looks the way it does; as opposed to just acting on guesswork, assumption, and blind tradition. And given this premise, I will also voice a supposition that if this particular history is excluded from public school curricula, the cause is not mere oversight. As long as the Internet is a cornerstone of U.S. commerce, its historical, anarchic roots are a threat to the cultural assumption that unregulated capitalism is the only route to freedom.

As Dave Clark, one of the Internet's founding minds, says: "We reject: kings, presidents, and voting. We believe in: rough consensus and running code." And for over thirty years, this was the Internet's credo. Without it, the Internet would not exist as it does today.

If you're reading this review, I'm guessing you spend a fair chunk of time on the Internet. As long as the Internet is a tool that consumes a great deal of our lives, influences our understanding of the world, and can fail or be forcibly removed from our lives, it is worth understanding–therein lies the ability to judge fair and worthy use from trivial, stupid, or malicious use.

Note: I may change my rating to five stars after finishing the book, but I have not yet finished digesting the authors' premise that the nation-state is in fact essential to the Internet's stability. From a pragmatic standpoint (which is perhaps the only relevant one), they are likely correct. But my bias is toward idealism, and I would yet like to find some possibility for a stable, long-term form of Dave Clark's manifesto on cyberspace.