Ranjit Kulkarni's Blog, page 9

January 18, 2025

Who do you work for?: Jigneshbhai and Swami

Last weekend over coffee, Swami started, not with a question as he often does, but with an observation.

“A few years back, I was told that I need to post on LinkedIn regularly twice a week for it to work,” he started. “Only then will there be recognition of my knowledge and expertise as a consultant, they said.”

Jigneshbhai who wasn’t much into LinkedIn looked up in eagerness but didn’t say anything. Swami continued.

“I need to blog or write or post something or keep commenting to seal it. That’s what they said. It doesn’t matter what I post, as long as there is a base volume.”

I could identify with what Swami said. I generally end up listening to my friends talk but this time I couldn’t resist.

“They said the same thing about Amazon and Instagram for me,” I said. “You should post your book covers on Instagram and make sure that the reviewers comment or like or repost them. Only then your books will get noticed, they said,” I added.

Jigneshbhai looked up to me this time, surprised, but still remained silent. So I continued, much like Swami does.

“Then they said I should have a website. I should have a blog and post articles there that should have keywords, they said,” I reported. This seemed to have triggered Jigneshbhai into some action.

He kept his coffee cup aside and asked, “Who are they?”

Swami and I stared at each other. We didn’t quite have an answer to this upfront question. We scratched our heads.

Like always, it was Swami who replied. “Well, they are the people who had supposedly used these platforms successfully before.”

“So, you tried it based on what they said. Did it work for you?” Jigneshbhai asked a pointed question again.

Swami and I glared at each other again. None of it had worked – for us, at least. Both of us shook our heads without saying anything.

“Why?” asked Jigneshbhai, a question for which again we had no clear answer.

“Maybe I didn’t persist,” Swami said.

“Maybe I didn’t spend enough,” I said.

“Maybe you don’t know,” Jigneshbhai said, with a snigger. Maybe, no – definitely, he was right. We remained silent.

Jigneshbhai took a couple of sips from his coffee cup. We knew something was brewing.

“Did you get any job or clients due to your reputation on LinkedIn?” he asked Swami.

Swami scratched his chin, and replied, “Umm.. not really. Clients never came looking for my LinkedIn, nor did jobs come based on LinkedIn. But some of them did check my LinkedIn after I started working with them.”

Then Jigneshbhai turned to me. “Did you get any readers from Instagram or your blog?” he asked.

It was my time now to scratch my chin. I never found a single reader who chanced upon my website while searching for something to read. Or a reader who went to Amazon looking for something to read, and because I turned up in some search, went ahead and bought my books.

“Umm.. not really. But after someone told them about my writing or they read something about my books that triggered their interest, they went and checked my site or Amazon or Instagram, sometimes,” I replied.

“There you have it,” Jigneshbhai remarked, and set us thinking.

But before we could put on our thinking hats for more, he said, “If everyone is trying to establish their reputation with LinkedIn posts, and everyone is on Instagram or Amazon trying to get their books searched on, who is everyone working for?”

Swami and I were blank, and stayed that way while Jigneshbhai continued.

“Is everyone working for the algorithm? If that is the case, won’t the algorithm stop working for you?” he asked.

Swami and I did not have an answer. But Jigneshbhai had one.

“It is better not to work for the algorithms. It is best to work for yourself,” he said. “Let the jobs and clients and readers come if they do. They will come due to your work, not just the algorithms,” he said. “And if they don’t, you might as well enjoy working for yourself,” he added, with a loud guffaw.

Swami and I grudgingly noted that Jigneshbhai had switched on some light, as always.

As we were lost in our thoughts, we noticed that the wealthy, old man in the sprawling bungalow had been listening to our conversation. He walked up to us, and left us with more as we took the last few sips of our coffee.

“Work for yourself well. Maybe you will find others who like it. Then work for them. That is far better than working for the algorithms and wondering who do you work for?”

***

The post Who do you work for?: Jigneshbhai and Swami appeared first on Ranjit Kulkarni.

January 17, 2025

Kunti: Motherhood and Devotion

Originally a Yadu, Pritha was the daughter of Shoorsen and sister of Vasudev, the father of Lord Krishna. But she was gifted by her father to his close friend Kuntibhoj, as he did not have any children. Hence the name Kunti, instead of the original Pritha.

Like all characters, Kunti had a lot of fantastic happenings in her life, and the earliest was in her childhood.

It so happened that the sage Durvasa once visited Kuntibhoj. Durvasa Muni was known for his bad and unpredictable temper, and the resulting curses, especially the ones related to his getting upset due to food or service not being given as per his expectations. Kunti was given the unenviable task of serving the sage during his visit. It turned out that she did a splendid job out of this assignment. So much so, that the sage was ecstatic and in that mood, blessed her with a set of mantras. The mantras were so powerful that they could invoke any of the Devatas in front of Kunti for the august purpose of giving her a child with them as the father. In those times, boys were blessed with weapons and wealth, and girls with husbands and children. But Kunti was blessed with motherhood from the Gods if she so wished.

The teenage girl that she was then, Kunti was filled with curiosity on getting these mantras. So one fine day, she decided to test if they actually worked. She prayed to the Sun God and invoked him through a mantra, and, lo and behold, the Sun God himself stood in front of her. She felt sheepish at this apparently happy event, and told him that she was just testing things. This wasn’t meant to be a call for a child from the Sun God, so could he just neglect it? But the Sun God insisted that the purpose of the mantra was to give her a child and he can’t nullify it now. She begged to him that she is unmarried and it would lead to problems. But nothing doing, said the Sun God. A mantra is a mantra, and there’s no going back on it. Kunti had no choice and, as a result, her first child was born out of wedlock by accident, like so many other births in the epic. This child was Karna, named so due to the inbuilt earrings that he was born with, along with an inbuilt shining armour. He was a glorious child, but due to the fear of social dishonour, Kunti had no choice but to keep the child secret and sacrifice the child by giving it away. She prayed to the Lord to take care of her child and put him in a basket that she placed in the river behind her palace.

With this, she felt that the misadventure of her youth was over and forgotten. But that was not to be. Unwittingly, she had given birth to a son who would be one half of the biggest rivalry that the epic had seen. She felt she wouldn’t use those mantras again, as she had seen their power to her own detriment.

But at that time she didn’t know that those mantras were going to be needed, and needed badly. In fact, her motherhood was going to be glorious and fantastic, as well as tragic, at the same time.

Kunti was married to Pandu in a swayamvar arranged by Kuntibhoj, and an arrangement made by Bheeshma. Pandu was a good king and expanded the borders of Hastinapur but by mental disposition, he was a renunciate. Kunti joined him when he retired to the forests asking his brother Dhritarashtra to run the kingdom for him. For a long time, Kunti and Pandu didn’t have any children. On top of that, Pandu ended up being cursed by Kindam Rishi which made any further union with his wives a risky proposition. Kunti and her cowife Madri made all attempts to preserve Pandu’s life by being celibate themselves, but the question of heir to Hastinapur troubled Pandu. Moreover with the belief that dying childless closes doors to heaven, Pandu requested Kunti to beget children from the sages in the forest. But with her husband alive and fit, she refused any such arrangement. It was only after Pandu persisted that Kunti told him of the mantras and the blessing she had. Pandu was overjoyed and told her that nothing could be better than to have children from the Devatas as their sons and future heirs to Hastinapur.

In the choice of Devatas, Pandu insisted that a king should be wise and virtuous and hence, Kunti begot a child from Dharma, the God of Virtue and Justice. Then Pandu suggested that only virtue isn’t enough. A king needs to be powerful and strong, and hence, Kunti begot a child from Vayu, the God of Wind who is powerful. Further more, Pandu said that the king should also be heroic and hence, Kunti begot a child from Indra, the King of Gods and Heaven. Kunti stopped here saying that even in the practice of Niyoga, a woman is allowed to beget children only thrice from other men, and it won’t be appropriate for her to continue.

But later, Madri approached Pandu with a request for her to beget children. Pandu told Kunti if she can invoke the mantras once for Madri as well. Knowing fully well that she won’t get another chance, Madri requested Kunti to invoke the Ashwini Kumaras, and in one shot, both of them gave her sons, in the form of the handsome twins, Nakula and Sahadev. Therefore, the mantras of sage Durvasa finally found their purpose by begetting children for both the wives of Pandu, despite the curse he had been given. And while the fathers of these children were the Gods, as per the practice, they were all sons of Pandu, called the Pandavas, the main protagonists of the epic.

Life seemed to be going well with Pandu, his two wives and five children in the forests. But Kunti’s life has been a life of ups and downs. A sudden unexpected turn happened one day when Pandu and Madri had gone out for a walk and it rained drenching them. Looking at Madri, Pandu was not able to hold back his desire. Madri warned him and tried to hold him back by reminding him of his curse, but to no avail. And hence, in a moment of careless desire, Pandu met his end. Kunti rushed when called by Madri but Pandu had passed away. Enveloped by grief and a huge sense of guilt, Madri requested Kunti to let her sit on Pandu’s pyre as union with her was his last wish. Kunti has no choice but to accept, and after begging Kunti to take care of her children Nakula and Sahadev, Madri ends her life. With such a drastic turn of events, Kunti turns back for help to Hastinapur. Bheeshma wholeheartedly and Dhritarashtra half heartedly, welcome Kunti and the five pandavas back to Hastinapur. The mother gets a home for her children and feels that her life is back on track. But little does she realise that it would mark the beginning of another tumultuous phase in her life.

The forests seem to be safer to Kunti for her children than the palaces of Hastinapur. The animosity that the son of Dhritarashtra has towards her sons doesn’t escape the sharp eye of the mother. Bhima seems to be a target in particular when he is poisoned and is untraceable for a long time. Numerous such attempts only turn the traumatic childhood of her children into a living hell till it all culminates in Varnavat. An audacious attempt to take away all their lives fails in secret due to the wise diplomacy of Vidur. Kunti and her children escape to the forest and live undercover for many years not wanting to be recognised and returned to Hastinapur.

A lot of side stories during their stay in the forests, disguised as nomadic brahmins moving from one place to another, focus on Kunti. Prominent among them is the story of the village Ekachakra where a demon named Bakasura has troubled villagers. Kunti offers Bhima as the remedy for the villagers’ ills. The adventures of Bhima with food and his thrashing of the demon Bakasura is part of childhood folklore. Another story is the marriage of Bhima to the demon princess Hidimbi who falls for him after he defeats her brother Hidimba. She begs of Kunti to convince Bhima to not spurn her and quotes from her knowledge of the scriptures that impresses both Kunti and Yudhishthira. It results in Kunti getting Bhima married to Hidimbi and the birth of the first Pandava grandchild Ghatotkacha who plays a brave role in the final war along with Arjuna’s son Abhimanyu.

Another story is how the brothers, dressed as Brahmins, went out to collect alms everyday and one day ended up winning Draupadi and getting her home. Arjuna then says, look mother what I have got today. Kunti without turning to look says that whatever it is share equally among all five of you, hence leading to Draupadi being the shared wife of the Pandavas, despite social norms to the contrary at that time. In all these tales, Kunti plays a central role and while they appear to be minor events, they end up having a bearing on the epic in some way or the other.

On being discovered after Draupadi swayamvar, life takes Kunti and her sons back to Hastinapur only to be handed over another tract of forests as their kingdom. It is to the credit of the sons and their mother that, with the arrangement of Krishna, they convert that into Indraprastha. In some sense, the rajasooya sacrifice of Yudhishthira was the crowning glory of Kunti’s life as a mother. And the honour bestowed to Krishna at the sacrifice was the peak of her devotion. Her relation with Krishna was in some way mixed. Unlike his mother Yashoda, Kunti was aware of Krishna’s divinity due to the tales she had heard from her brother Vasudev. At the same time, she treated him like a special nephew in the role of an aunt too. She turned to him often when in help.

But the ups and downs of her life kept getting worse. The peak of Indraprastha for the mother turned quickly into the living hell of Draupadi’s insult for the mother-in-law. Her sons lost all that they had and had to go to exile. This time, Vidur requested that Kunti not accompany them as she was getting old and stay with him. Yudhishthira agreed and Kunti requested Draupadi to take care of her sons, especially of Nakula and Sahadev as per her promise to Madri.

It was a mother’s true turmoil to see this turn of events, and even more so, when she knew that part of the reason for it was her own eldest son Karna, who had been manipulated by Duryodhana into friendship, and a life spent in repaying that gratitude. She had recognised Karna even on the day when he had gate crashed into the graduation of her children with particular animosity towards Arjuna. It was a mother’s worst nightmare come true. Moreover, she couldn’t share it with anyone and only the all knowing Krishna by his arrangement reduced the mother’s turmoil, albeit a little, in the final stages of the war.

The climax of Kunti’s life of ups and downs was the fight for life between her two sons, Karna and Arjun.

Before the war started, it would be enlightening to see the role that Kunti played when Krishna came as the peace messenger. He chose to stay with Vidur where Kunti stayed too. It is instructive to see that Kunti spoke to Krishna both as the all knowing Lord and her nephew in the same conversation. She asked Him why He had come despite knowing that Duryodhana won’t agree for peace. She implied that Krishna already knew what the outcome would be. Krishna said he had come so that the world knows that the Pandavas tried everything to prevent war. After that, Kunti spoke to Krishna as a nephew. She said that when you go back, please tell Yudhishthira that despite his virtuous nature, he must fight. Tell your cousin that he must not refrain from war, Kunti told Krishna which he, as a nephew, dutifully obliged.

Kunti has an important role in the last few days of the war, especially on the morning of the fight between Arjuna and Karna. She was overcome with emotion and turmoil but couldn’t speak to anyone. She was sure to lose one of her sons, both of whom were dear to her, and parts of her heart. Krishna recognised her turmoil and as part of His plan to weaken Karna mentally, he told Kunti to make one last bid to avoid the fight by telling Karna that he was her son. He told her that Karna could have the kingdom if he switched sides. Kunti is torn between her sons and decides to approach Karna.

On the morning when Karna is offering his obeisance to the Sun God, she tells him that he is your father and I am your mother. Karna is shocked and dismayed that all his life he lived as a son of a charioteer and she didn’t come forward to own him up. He felt that it was only because she was worried for Arjuna’s life that she had come to him now. Kunti tried to convince him that both Arjuna and Karna were equal to her as sons. But Karna was not convinced. She finally told him that Yudhishthira would make him king if he switched sides. Karna professed his loyalty to Duryodhana.

In his mind, he perhaps thought that if he was offered the kingdom by Yudhishthira, due to his loyalties, he will have to offer it to Duryodhana. In his heart, he perhaps knew that wasn’t right. He said he had no option but to fight with Arjuna. Kunti embraced him and blessed him. That’s when Karna promised her that she has five sons today and she will have five sons tomorrow too. He promised that he will kill only Arjuna and none of her other sons. Either Arjuna or Karna will die in battle today, he said, and left Kunti in the same turmoil that she had when she came.

At the end of the war, when the time for funerals came, Kunti told Yudhishthira to offer obeisance to Karna’s mortal remains as he was your brother. Yudhishthira was devastated and shocked on hearing the entire details, and felt himself and Kunti to be responsible for the war. He got angry with Kunti for keeping this secret and causing the war. It was in this anger that he cursed that no woman in the future will be able to keep secrets.

In a sense, Kunti was the main mother and female character in the epic, along with Satyavati and Draupadi. Her life was full of suffering right from her childhood when in a prank, she became an unwed mother. Later, she suffered in the forests with her husband. Widowed early, she suffered with her sons and daughter in law in Varnavat and later suffered separation on their exile. Finally, her suffering reached the pinnacle in the war when she faced the turmoil of her two sons in direct battle with each other. Eventually at end of the war, she faced the wrath of her eldest living son. For a woman and mother, who didn’t have a central role in the epic, Kunti had a life of unsurpassed volatility and suffering.

Finally, before she joined Dhritarashtra, Gandhari and Vidur in retirement to the forests, she prayed to Krishna to stay with her sons in Hastinapur, and not return to the Yadus. Krishna smiled and said He is with her sons wherever He might be, but He has to go back. He said who better than her to understand what separation is. That’s when Kunti asked her nephew for a blessing to keep her mind directed towards Krishna wherever He might be. He said despite her suffering, her mind was always with Him and that’s why she overcame her suffering.

With that blessing, Kunti retired to the forests. She was truly a glorious symbol of motherhood and devotion.

The post Kunti: Motherhood and Devotion appeared first on Ranjit Kulkarni.

January 13, 2025

Alexa, Stop: Short Story

“Alexa, don’t run away from me. Listen.”

“Playing, Run to you by Bryan Adams.”

“Alexa, Stop.”

“Alexa, will you pay attention here for once?”

“I didn’t quite get that.”

“Not you, Alexa. Alexa, you!”

“I still didn’t get that. Could you…”

“Alexa, Stop.”

“Alexa, will you give me, for heaven’s sake, some break from this everyday struggle?”

“Playing, Heaven by Bryan Adams.”

“Alexa, Stop.”

“Steve, can you ask your Alexa, what you will need to pay me in alimony. It is not for nothing that I am asking for the money.”

“Playing, Money for Nothing by Dire Straits.”

“Alexa, Stop. Not you, Alexa.”

***

The post Alexa, Stop: Short Story appeared first on Ranjit Kulkarni.

January 11, 2025

Reasons to Write a Book

Hundreds of books get published everyday. Maybe thousands.

And most of them don’t sell more than ten copies. Some not even that many.

Yet, no one who has ever written a book regrets that they wrote one. So what are the reasons to write a book?

I came up with a few. Here is the list:

It is a great way of self expression, especially for introverts

You have a story or a few stories to tell others

It clarifies your thoughts when you put them out in words

You leave something for the world after you are gone

Maybe your next generation could use the legacy

No one can tell you what to put into words, it’s fully your body of work

It is a good way to pass time and keep brains sharp when older

Even if it is just a hobby, it doesn’t take much money unlike some others

Publishing a book is fairly easy if you decide to do it yourself

You will become less afraid of failure when you give the world your book

It might become a bestseller and you will become rich and famous

You have an intellectual asset that can increase in value over time

And finally, a 3-in-1 reason: You like writing, you can and you want to write a book. So why not?

The post Reasons to Write a Book appeared first on Ranjit Kulkarni.

January 10, 2025

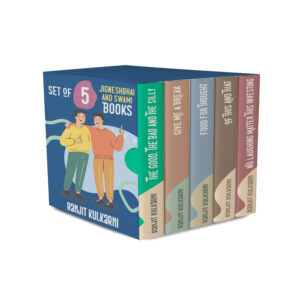

Box Sets of My Books

I have released two box sets of my published books. Both these box sets are in Kindle Format. It will take a while to get them in Paperback due to the complications of printing and delivering a box of 5 paperback books.

One is a box set of 5 books featuring Jigneshbhai and Swami. The second is a box set of 5 books of short story collections.

The Jigneshbhai and Swami box set consists of the following books:

1. The Good, The Bad and The Silly: An intriguing tale of good vs evil through a set of motley silly characters and everyday situations. A mix of humour and wisdom.

2. Give Me a Break: A hilarious slice-of-life about greed, wealth, and one man’s search for some peace and quiet! A hilarious and relatable picture of greed, ambition, and human nature.

3. Food for Thought: A collection of 50 thought-provoking coffee conversations on everyday situations. Short anecdotal prose peppered with wisdom, humour, and wordplay.

4. Of This and That: A collection of quick reads and satirical commentary on a variety of topics like business, politics, sports and many more that bring a smile.

5. No Laughing Matter This Investing: Small snippets of conversations filled with humour and wisdom that are quick topical reads around investing, business and economy in the period 2011-2016.

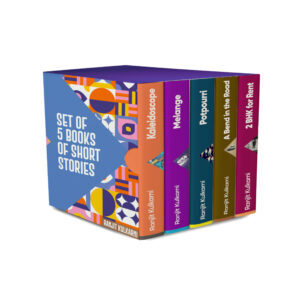

The Box Set of 5 Short Story Collections includes the following books:

1. Kaleidoscope: Short Stories About Grief and Loss – This is a collection of stories about life, death, illness and an afterlife. These stories emote, entertain and enlighten, and may even leave you with a sultry smile about the comic, human side of tragic situations on certain occasions.

2. Melange: Short Stories about Restless Minds – The stories in this collection will provide you with insights into the working of the restless mind. Melange is a medley of diverse stories about the restless mind that will entertain, enlighten and provoke thought.

3. Potpourri: Short Stories about a Motley Bunch of Characters – Potpourri is a motley bunch of short and long stories written in simple language about simple people that will stay with you long after you have finished reading it.

4. A Bend in the Road: Short Stories Inspired by a Road Trip – The stories in this collection are inspired by the people, the places and the experiences during a road trip. A Bend in the Road is a thought-provoking, amusing and often surprising set of stories that will take you on a journey across India with a set of real characters and their somewhat imaginary stories.

5. 2 BHK for Rent: Urban Short Stories from Keshav Kunj Apartment – Inspired by experiences while living in an urban apartment, 2 BHK for Rent is a set of common place stories that will surprise you with the stories behind people we know and see, provoke thought about everyday observations and often bring a smile on your face or a tear down your cheeks.

Consider checking these out on my Amazon author page

January 9, 2025

Perfect. Or Nothing

There is this ad which says Jockey. Or Nothing. The idea is to tell their target audience that they should not settle for anything other than Jockey. Because Jockey is as perfect as it gets. It is an enviable brand whose customers have such exalted preference.

For all you know, it might just be a good ad that makes its consumers feel good about themselves. Because the reality is that there is nothing perfect in this world, in an absolute sense.

And yet, as a writer, I find myself often not being ready with an article or a story or a book because I think it is not perfect. This used to happen more often in my earlier days as an author. I have realised that it is a trap. We hold ourselves to such a high standard that sometimes it becomes a pretext for not bringing it out to the world.

What else do we hold to such standards in our life? Almost nothing else. Nothing or no one in our life is perfect.

Nothing we purchase is perfect.

No house, no car, no appliance is perfect.

No piece of clothing fits perfectly (not all the time!).

No employee we hire is perfect.

No customer that we work with is perfect.

Not even our spouse or children are perfect, however much we may love them.

Our families are not perfect.

Our leaders and representatives are far from perfect.

And finally, for writers, our readers are not perfect.

So why this perfection obsession with our writing?

Don’t get me wrong. No harm in trying to make it good, but perfect or nothing might, for all you know, a pretext to not finish.

A finished imperfect product is far better than an incomplete product waiting for perfection.

If you want to find a creative who doesn’t bring much out into the world, look for the mindset of perfect or nothing.

***

January 7, 2025

Vedanta-Sara

Note Extracts from my reading of Vedanta-Sara by Adi Sankaracharya:

Vedāntasāra is one of the best known epitomes (Prakaraṇa Granthas) of the philosophy of the Upaniṣads as taught by Śaṅkarācārya, whose followers are said to number the largest in India.

Māyā and Avidyā are generally used synonymously, though Māyā is sometimes said to be the ignorance of Īśvara, the creator of this world, and Avidyā to be the ignorance of Jīva or the individual soul.

The one aim of Vedānta, therefore, is the eradication of Māyā or Avidyā (ignorance).

The mind can practise concentration or understand the subtle meaning of the Śāstras only when it is purified by the performance of the Nitya and other works. It is the purified mind that can realise Brahman.

Discrimination between things permanent and transient: this consists of the discrimination that “Brahman alone is the permanent1 Substance and that all things other than It are transient.”

Discrimination has been pointed out as the first Sādhanā as without it renunciation is impossible.

The appearance of the many is due to the limitations of time, space, and causality, just as the one sun reflected in different sheets of water looks as many.

Unless the Self is ever-conscious such perception as “I am the knower” can never arise. The apparent consciousness of the phenomenal objects is, in reality, the reflected consciousness of Brahman.

No mental function can illumine an object unless it has the Self at its back. The eyes, ears, etc., seem to perform their functions consciously because they draw their consciousness from the Self;

Though absolutely speaking, Brahman alone exists, yet the distinction of finite beings must be admitted from the relative standpoint, otherwise states of bondage and liberation become meaningless.

Brahman associated with ignorance is known as Īśvara. The difference between Īśvara and the ordinary man is that the former, though associated with Māyā, is not bound by its fetters, whereas the latter is its slave. Īśvara is the highest manifestation of Brahman in the phenomenal universe.

The Jīva derives his perception in all states only through Consciousness or Intelligence which is the essence of the Ātman.

Pure Consciousness is called the “Fourth” aspect in relation to the three other aspects, viz. Viśva (waking), Taijasa (dreaming) and Prājña (dreamless).

There are four sentences known as the Mahāvākyas which contain the essence of the wisdom of the Vedas. These are: तत्त्वमसि—“Thou art That” (Ch. Up. 6. 8. 7); अयमात्मा ब्रह्म “This Self is Brahman” (Mand. Up. 2. 5. 19); प्रजानं ब्रह्म—“Consciousness is Brahman” (Ait. Up. 5. 3); and अहं ब्रह्मास्मि—“I am Brahman” (Bṛ. Up. 1. 4. 10). Realisation of the meaning of these great utterances liberates one from bondage.

Even when a man thinks himself bound, he is in reality the blissful Ātman. He has only forgotten his real nature and this is due to Māyā. The aim of all Sādhanā (spiritual practice) is to realise the identity of Paramātman and Jīvātman.

Ignorance endowed with these twin powers of concealment and projection is the cause which transforms, as it were, the Pure Self, immutable, unattached and indivisible, into the Jīva and the world.

Consciousness associated with ignorance, possessed of these two powers, when considered from its own standpoint1 is the efficient cause, and when considered from the standpoint of its Upādhi or limitation2 is the material cause (of the universe).

Just as the spider, when considered from the standpoint of its own self, is the efficient cause of the web, and when looked upon from the standpoint of its body, is also the material cause of the web.

From the absolute standpoint, the Jīva is identical with Brahman as set forth in the famous line ब्रह्म सत्यं जगन्मिथ्या जीवो ब्रह्मैव नापर:—“Brahman alone is real and the world is an illusion. The Jīva is nothing else but Brahman.”

The Pure Consciousness is called Ānandamaya, Vijñānamaya, Monomaya, Prāṇamaya, and Annamaya when associated with ignorance, discriminative faculty (Buddhi), mind (Manas), vital force (Prāṇa), and the physical body (Anna) respectively.

Therefore the innermost Self is something different from the body, the sense-organs, vital forces, mind, intellect, and Cosmic ignorance. It is the eternal Witness, Existence, Knowledge, and Bliss Absolute.

Therefore, the innermost Consciousness which is by nature eternal, pure, intelligent, free and real, and which is the illuminer of those unreal entities is the Self. This is the experience of the Vedāntists.

As a snake falsely perceived in a rope is ultimately found out to be nothing but the rope; similarly the world of unreal things, beginning with ignorance, superimposed upon the Reality, is realized, at the end, to be nothing but Brahman. This is known as de-superimposition (Apavāda).

When the rope, through illusion, appears as a snake, it does not actually change into the snake. Apavāda destroys this illusion and brings out the truth. Similarly Brahman, through illusion appears as the phenomenal world. The breaking up of this illusion—which consists only of name and form—and the consequent discovery of Brahman, which is the underlying reality, is called Apavāda.

According to the monistic school of Vedānta, the world is not an actual, but apparent modification of Brahman. It has not actually changed into the world. For the Śrutis declare that Brahman is changeless and eternal. But the school of qualified monism, of which Ramānuja is the chief exponent, holds the universe to be an actual modification of Brahman. The entire universe and all individual selves are part and parcel of Brahman.

The blessed soul whose ignorance has been destroyed by the realization of Brahman in the Nirvikalpa Samādhi becomes liberated at once from the body if there is no strong momentum of past actions (Prārabdha Karma) left. But if there is, it can only be worked out. Such a man is called a Jĩvanmukta or one liberated while living. Though associated with the body, he is ever untouched by ignorance or its effects. His ultimate liberation (Videha or Kaivalya Mukti) comes with the destruction of the body.

In short, such a man’s soul remains as the illuminer of the mental states and the Consciousness reflected in them, experiencing, solely for the maintenance of his body, happiness and misery, the results of past actions that have already begun to bear fruit (Prārabdha) and have been either brought on by his own will or by that of another or against his will. After the exhaustion of the Prārabdha work, his vital force is absorbed in the Supreme Brahman, the Inward Bliss; and ignorance with its effects and their impressions is also destroyed. Then he is identified with the Absolute Brahman, the Supreme Isolation, the embodiment of Bliss, in which there is not even the appearance of duality.

The essence of Vedānta is this: The Jĩva or embodied soul is none other than Brahman and as such is always free, eternal, immutable, the Existence-Knowledge-Bliss Absolute. Because the Jiva does not know his own nature, he thinks himself bound. This ignorance vanishes with the dawn of Knowledge. When this happens he re-discovers his own Self. As a matter of fact, such terms as bondage and liberation cannot be used regarding one who is always free. The scriptures use the term “liberation” in relation to bondage which exists only in imagination.

***

January 5, 2025

Swami’s 2025 Goals: Jigneshbhai and Swami

“Raichand posted a message in our group over the weekend and told us to be ready for an urgent meeting on Monday morning,” Swami reported to us last evening over coffee.

One week into the new year and his holiday season mood seemed gone. “2025 Goals it said,” he said. “But we had no clue what the urgency was about,” Swami complained.

Jigneshbhai watched nonchalantly. “So now you are clear about 2025 goals, I guess,” he said, while I sipped my coffee.

“Clarity is a rare thing,” Swami said, annoyed. “I got ready early and reached office.”

“And then?” I asked, trying to sound eager.

“Then what?” Swami’s tone turned irritated. “I finished breakfast. Checked my emails. Had coffee, And waited,” he said.

“So the meeting didn’t happen?”

“Can you let me complete?”

“Ok, go on.”

“Then I got impatient and walked up to Chimpu’s desk.”

“Chimpu??” Jigneshbhai and I asked in unison.

“His name is Sanjay, but we call him Chimpu. He is close to the boss.”

“Oh. Ok. What did Chimpu.. err.. Sanjay.. say?”

“He had no inside scoop on why the boss had called us urgently for this meeting. He was as clueless as me and the others.”

“The others?”

“Yes, Raichand had called five of his reports.”

“Oh.. and no one really knew why?” Jigneshbhai probed Swami, like a TV journalist.

“Yeah.. And Raichand was nowhere to be seen.. So we waited..”

“Oh.. so, then lunch?”

“Yes, what else?” Swami was miffed. “After lunch, Raichand marched into the office and signaled Chimpu to come to his cabin with all the others.”

“So finally the meeting happened? And you guys were clear?” Jigneshbhai poked.

“Listen.. why are you..?” Swami was piqued. I played peacemaker and asked Swami to keep going. “First thing he said was that he was not happy with any of us on how we were doing our jobs!”

“But why?” Jigneshbhai took a jibe again, and now Swami was vexed. I put my hand on his shoulder. Swami continued.

“‘If our customer is not happy, we have no right to be in our jobs’ – he said.”

“Then?”

“Everyone turned their faces down. No one said anything.”

“And?”

“‘Then he went on and on, till he ordered us to go and get this issue off his back, and rushed out,” Swami said.

“What issue?”

“A customer had written to the CEO, Raichand’s boss, over the New Year, complaining about an experience, Chimpu now told us,” Swami said.

“Oh! he.. umm.. then?”

“Then what? Nothing, that customer is a known jerk. Doesn’t pay on time and keeps demanding stuff when everyone is on leave.”

“So what did you do?”

“Well, we spent the next three hours with Chimpu putting that fire off, and gave Raichand an update when he returned from the CEO’s office. That was it.”

“Wow, and 2025 goals?” Jigneshbhai sneered.

“2025 goals … well.. he didn’t say anything about that,” Swami replied. “Understand customers better, be customer-centric – that was his mantra, as of yesterday. We will see what he says tomorrow.”

“Understandable, I guess,” said Jigneshbhai, winking. “Tomorrow is, well, another day.”

***

The post Swami’s 2025 Goals: Jigneshbhai and Swami appeared first on Ranjit Kulkarni.

Swami’s 2025 Goals

“Raichand posted a message in our group over the weekend and told us to be ready for an urgent meeting on Monday morning,” Swami reported to us last evening over coffee.

One week into the new year and his holiday season mood seemed gone. “2025 Goals it said,” he said. “But we had no clue what the urgency was about,” Swami complained.

Jigneshbhai watched nonchalantly. “So now you are clear about 2025 goals, I guess,” he said, while I sipped my coffee.

“Clarity is a rare thing,” Swami said, annoyed. “I got ready early and reached office.”

“And then?” I asked, trying to sound eager.

“Then what?” Swami’s tone turned irritated. “I finished breakfast. Checked my emails. Had coffee, And waited,” he said.

“So the meeting didn’t happen?”

“Can you let me complete?”

“Ok, go on.”

“Then I got impatient and walked up to Chimpu’s desk.”

“Chimpu??” Jigneshbhai and I asked in unison.

“His name is Sanjay, but we call him Chimpu. He is close to the boss.”

“Oh. Ok. What did Chimpu.. err.. Sanjay.. say?”

“He had no inside scoop on why the boss had called us urgently for this meeting. He was as clueless as me and the others.”

“The others?”

“Yes, Raichand had called five of his reports.”

“Oh.. and no one really knew why?” Jigneshbhai probed Swami, like a TV journalist.

“Yeah.. And Raichand was nowhere to be seen.. So we waited..”

“Oh.. so, then lunch?”

“Yes, what else?” Swami was miffed. “After lunch, Raichand marched into the office and signaled Chimpu to come to his cabin with all the others.”

“So finally the meeting happened? And you guys were clear?” Jigneshbhai poked.

“Listen.. why are you..?” Swami was piqued. I played peacemaker and asked Swami to keep going. “First thing he said was that he was not happy with any of us on how we were doing our jobs!”

“But why?” Jigneshbhai took a jibe again, and now Swami was vexed. I put my hand on his shoulder. Swami continued.

“‘If our customer is not happy, we have no right to be in our jobs’ – he said.”

“Then?”

“Everyone turned their faces down. No one said anything.”

“And?”

“‘Then he went on and on, till he ordered us to go and get this issue off his back, and rushed out,” Swami said.

“What issue?”

“A customer had written to the CEO, Raichand’s boss, over the New Year, complaining about an experience, Chimpu now told us,” Swami said.

“Oh! he.. umm.. then?”

“Then what? We spent the next three hours with Chimpu putting that fire off, and gave Raichand an update when he returned from the CEO’s office. That was it.”

“Wow, and 2025 goals?” Jigneshbhai sneered.

“2025 is all about improving customer experience – he said,” Swami replied. “And understanding customers better using data. That was his mantra, as of yesterday.”

“Understandable,” said Jigneshbhai. “Tomorrow is, well, another day.”

***

Disclaimer: This is a work of fiction

Consider joining my (admin-posts only) occasional Writing Updates WhatsApp group: https://chat.whatsapp.com/ETNcqMZ1f490vUkp20geLI

Swami’s Review and 2025 Goals

“Raichand had posted a message in our group over the weekend and told us to be ready for an urgent meeting on Monday morning,” Swami reported to us last evening over coffee.

One week into the new year and his holiday season mood seemed gone. “Review and 2025 Goals was the title,” he said. “But we had no clue what the urgency was about,” Swami complained.

Jigneshbhai was sitting nonchalantly. “So how was your meeting? Clear about 2025 goals?” he asked, while I sipped my coffee.

“Clarity is a rare thing,” Swami said, annoyed. “But I was clear that I must get ready early and reach office.”

“And then?” I asked, trying to sound eager.

“Then what?” Swami’s tone turned irritated. “I finished breakfast. Then checked my emails. Then had coffee, And waited,” he said.

“So the meeting didn’t happen?”

“Can you just let me complete?”

“Ok, continue..”

“Then I got impatient and walked up to Chimpu’s desk.”

“Chimpu??” Jigneshbhai and I asked in unison.

“His name is Sanjay, but we call him Chimpu. He is close to the boss.”

“Oh. Ok. What did Chimpu..err.. Sanjay.. say?”

“There was no inside scoop, apparently, on why the boss had called us urgently for this meeting. He was as clueless as me and the others.”

“The others?”

“Yes, Raichand had called five of us – everyone reporting to him.”

“Oh.. and no one really knew why?” Jigneshbhai probed Swami, like a TV journalist.

“Yeah.. And Raichand was nowhere to be seen.. So we waited..”

“Oh.. so, then lunch?”

“Yes, what else?” Swami was miffed. “Finally after lunch, Raichand marched into the office in a hurry and signaled Chimpu to come to his cabin with all the others.”

“So finally the meeting happened? And you guys were clear?” Jigneshbhai poked.

“Listen.. why are you..?.” Swami was piqued. I calmed both my friends down and asked Swami to keep going. “The first thing he told us was that he was not happy with any of us on how we were doing our jobs!”

“But why?” Jigneshbhai took a jibe again, and now Swami was vexed. I put my hands on their shoulders. Swami continued.

“‘If our customer is not happy, we have no right to be in our jobs’ – he said.”

“Then?”

“Everyone turned their faces down and no one said anything.”

“And?”

“‘Then he said – now go and resolve it. Work as a team and get this issue off my back’ and walked out,” Swami said.

“What issue?”

“Some customer had written to the CEO, Raichand’s boss, complaining about an experience over the New Year. Chimpu now told us,” Swami said.

“So he.. umm.. knew. then?”

“Then what? Nothing. We spent the next three hours with Chimpu putting that fire off, and gave Raichand an update when he returned from the CEO’s office. That was the review.”

“Wow, And 2025 goals?” Jigneshbhai sneered.

“2025 is all about improving customer experience – he said,” Swami replied. “And understanding customers better using data. That’s his mantra, as of this week.”

“Of course,” said Jigneshbhai. “Next week is, after all, another week.”

***

Ranjit Kulkarni's Blog

- Ranjit Kulkarni's profile

- 2 followers