Brett Ann Stanciu's Blog, page 171

March 20, 2016

Maple, Maternal

The granite foundation of a barn I never saw standing once spread across a field not far from our house. The barn burned before I lived on West Woodbury Road, and a number of years ago, the property changed hands. The new owners grazed cows in that field, and someone removed all the old granite blocks. Now, a young Menonnite couple and their two small boys live there. Last spring, they tilled an enormous garden and planted a huge strawberry patch. Those plants should produce this summer.

Over years, my growing daughters and I watched this field change. One summer afternoon, as we sat on the lawn of the long-abandoned farmhouse, I noticed the electrical line stopped at the barn. I’d heard rumored the bachelor who last lived in the farmhouse had no electricity, but I’d never noticed that rural electrification must have brought juice right up to the barn and then stopped. The house was across the road. From when it was built until it was pulled down, electric lights never lit its rooms.

This spring, the young couple with their two merry-eyed boys tapped maples all along the road. Last summer, we saw them – father, mother in her skirts, boys in the bike seats – pedaling along the road in the well-lit evenings. May the sap flow generously for these kind people, from the trunks of these long-enduring, wide-reaching beauties. Today, I lay on the cold ground, staring up at that infinitely blue, March sky, world without end.

Whoever you are, go out into the evening,

leaving your room, of which you know every bit;

your house is the last before the infinite,

whoever you are.

– Rainer Maria Rilke

West Woodbury, Vermont

March 18, 2016

How To Write a Story….

Any writer knows a story can be told a myriad of ways. Today, visiting a school that once hovered near the brink of disintegration, I realized that school’s story could once have been told in numbers that reflected too much poverty, too little resources and not enough skills: too little – and too little again, and again, and maddeningly again – all the way around.

Instead, this is now a story of growing gardens and colorful classes – and thriving children. Who decides when a story needs to be rewritten? For a school? Or for yourself?

I remember Mary Oliver’s line posing the question about what to do with your one wild and precious life. Create at least one or two fine things, I thought. Leave one or two marks for better, and not for worse.

Sometimes I go about pitying myself, and all the while I am being carried across the sky by beautiful clouds.

– Ojibway proverb

Hardwick, Vermont

March 16, 2016

Spring Fever

Since the time change, my ten-year-old daughter cannot sleep. At 10:30 last night, she peered from her bunk bed, cheshire cat-like in the dim room, insisting she couldn’t sleep because she was excited. But I don’t know what I’m excited about!

I reached up and held her slim, warm fingers. It’s spring fever, I told her.

But I don’t have a fever….

All day long, as much as possible, she’s outside, poking a stick in running streams, painting her fort beneath the pine trees, biking up and down with road with her friend. The two of them run into the kitchen, breathlessly excited about spying on her father and his friend in the sugarhouse. Their stories spill out about biking through icy puddles and finding turkey tracks along the road. Beneath our boots, more of the earth reappears in its muddy glory every day, shaking off winter. Spring!

….And does it not seem hard to you,

When all the sky is clear and blue,

And I should like so much to play,

To have to go to bed by day?

– Robert Louis Stevenson, “Bed in Summer”

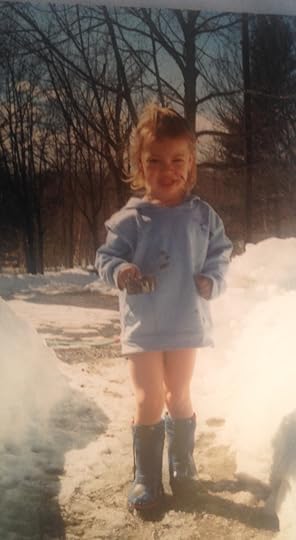

Molly S. Photo/Woodbury, Vermont

March 14, 2016

Martenitsa, or Bulgarian Spring

Years ago, I worked with a Bulgarian family who, every March, made little yarn dolls of red and white wool. Red for the heat of summer, white for winter. We were all friends at that workplace, and everyone wore those little gifts of martenitsa dolls until they frayed. Then, our Bulgarian friends insisted, spring was here.

Spring may come quicker in Bulgaria than it does in Vermont.

With snow falling today, the little girl left her forest fort alone, reading library books by the wood stove and eating popcorn.

Another way, perhaps, to think of martenitsa is as a great leveler: even winter’s savage teeth will yield to the persistence of spring.

But not yet… not quite yet… Vermont’s version of martenitsa is maple sugaring. Fire, sap, sugar: all eventually overtaken by budding.

The value of doing something does not lie in the ease or difficulty, the probability or improbability of its achievement, but in the vision, the plan, the determination and the perseverance, the effort and the struggle which go into the project. Life is enriched by aspiration and effort, rather than by acquisition and accumulation.

– Helen & Scott Nearing, The Good Life

Woodbury, Vermont/Photo by Molly S.

March 13, 2016

A Starlit Night

Last night, my daughters and I walked the neighbor’s child home in the dark. We had been outside for a while, playing a variation of tag with flashlights and laughter, resulting in the older daughter slipping on ice and lying elbows-down in mud. With the flashlights off, we walked along the muddy road beneath the starlight. The night was balmy for mid-March, suffused with the scent of thawing earth: a rich odor so pervasive it was a constant companion. The moon, a white curve, shone a pure, yellow-white light.

On the way home, we saw our house through the bare hardwoods, the strings of little lights the girls nailed along the eaves twinkling. We passed just one house along our road where a single light shone; they must have been gone. It was just the girls and the star-and-moonlight and the mud and I. The peepers are not stirring yet, and none of the woodland creatures called. Beneath our boots, the earth shifted, softening, giving up its winter frost. My older daughter said, I could walk forever, on a night like this.

This morning, watching a single robin tugging at our lawn, I thought of my older daughter, and how, before long, this girl will be on her womanly journey, walking different patches of earth – in boots, or sandals, or heels – beneath this same exquisitely beautiful sky. I opened the window and listened for birdsong, relishing the season we’re in.

What a strange thing! to be alive beneath cherry blossoms.

– Issa

Vermont, Mach 2016

March 11, 2016

The Sweet Spring Season

Signs of spring:

The school busses won’t travel on the backroads due to impassably muddy stretches. The superintendent sends an email: Drop off your kids to meet a bus at the corner barn…

An enormous flock of singing blackbirds in a single maple tree beside the post office.

Steam from the sugarhouse sweetening cold fog; April’s come early, this year.

April is the cruellest month, breeding

Lilacs out of the dead land, mixing

Memory and desire, stirring

Dull roots with spring rain…

In the mountains, there you feel free.

I read, much of the night…

– T.S. Eliot, The Waste Land

Hardwick, Vermont/Photo by Molly S.

March 9, 2016

The Great Wide World

Early this morning, on what promised to be an incredibly balmy Vermont day, I read with intense fascination a few pages my father had emailed me. The pages were from Sherwin Nuland’s How We Die, about a horrific and bizarre murder of a young girl. Having two daughters myself, I read with agony. In this excerpt, Nuland clips in a lengthy written piece by the child’s mother. She described her own sensation of warmth at the murder scene, and a calmness in her dying child’s eyes, as though the actual event of dying had been cosseted – or eased– in some inexplicable way for the child and the mother present at her violent death.

While I have been fortunate beyond measure never to experience that kind of trauma or grief, three times in my life I have had a wholly mystical experience at pivotal junctures.

At the caesarian birth of my second child, lying prone on the table, I had a forceful urge to rise up and leave the room, that I would suffocate imminently if I did not move. With the anesthesia, of course, I couldn’t do more than raise my arms and head, and then abruptly I was external to my body. With a clear understanding that I was drifting towards the ceiling, as if I were a helium balloon, the voices of the operating room lessened, words receding into murmurs. I had a profound sense of calm, and I had no regrets about slipping away. Then I heard an infant crying, a thin, plaintive wail, and I thought (this seems quite odd now), Whose baby is that, crying and alone? I thought how cold it was in that room for a baby. Later, I thought I had pity for that baby, but perhaps, more accurately, it was empathy. Abruptly, I realized that crying baby was mine, and instantaneously I was back in my body in the OR, begging to hold my newborn.

I first met this daughter through sound, not through the flesh of a vaginal birth or a wet and squirming infant laid against my bare breast. Yet the bond between the two of us is impermeable. My impulse to nourish and protect this child – to mother her – is as mighty as any universal law, consistent as gravity pulling falling apples to earth. Repeatedly over the years, I’ve thought of that Shakespearian line There are more things in heaven and earth, Horatio,/Than are dreamt of in your philosophy. Those wonders, certainly, are far more faceted than simple pleasure, in our world filled with such joy and such incredible grief. And yet, reading this morning, again I realized how wide is our universe, infinitely wiser than its players.

As a confirmed skeptic, I am bound by the conviction that we imust not only question all things but be willing to believe that all ithings are possible.

– Sherwin B. Nuland, How We Die

Photo by Molly S./Burlington Airport, Vermont

March 7, 2016

Private v. Public

This morning, after driving through a surprisingly thick snowstorm, I found myself in a tiny room in the radio studio of WDEV in Waterbury. Hester Fuller, the host, had kindly read my book and interviewed me for a bit, then Gary Miller (author of the fine collection Museum of the Americas) came in, too, with Joe Citro on the phone line.

We were literally knee-to-knee in a tiny room, talking about the intimacy of writing. Writing is that curious mixture of intense privacy – literally, the stuff of our own experiences – spun into shared stories. John Steinbeck’s East of Eden wound into my life when I was fifteen, lodging deeply in my blood cells, its influence surfacing in my own writing. Over and over, I have hammered myself against Steinbeck’s anvil that insists on seizing human choice despite the chaotic happenstance of human life. How will I understand my life? The lives of those I dearly love?

Driving home in the dark tonight, I realized my character, Fern, understood her life like this: finding an abandoned sweater in a library’s free box, she washed and then unravelled the yarn, discarding what was ruined beyond repair, saving what she could. Then she knitted, by trial and error, a sweater patterned with trees and mountains and Lady Moon, creating a work of beauty – and practicality.

Only after a writer lets literature shape her can she perhaps shape literature. In working-class France, when an apprentice got hurt, or when he got tired, the experienced workers said, “It is the trade entering his body.” The art must enter the body, too.

– Annie Dillard, The Writing Life

Burlington, Vermont, March 2016

March 5, 2016

The Vermont Season of Pre-Spring

A number of years ago, I conceived an idea that our family’s financial salvation lay in wedding favors. With our maple syrup, colored card stock, a paper cutter, and raffia, I filled tiny bottles with syrup and bow-tied on little cards printed with hopeful things like Julie and Josh, July 8, 2001, Eat, Drink & Be Merry. Or: A sweet beginning. In the long run, my fortune didn’t lie there, but I met interesting people at profoundly pivotal junctures in their lives.

One April, in an intense mud season, a couple unexpectedly drove out to our house. We were deep in the midst of sugaring with a three-year-old. On our back road and driveway – and all around the house where the snowbanks were fiercely melting – lay mud that sucked at our knee-high boots with an audible glop. The winter had been its usual terror, and immense snowbanks mounded all around the house, interspersed by our trodden paths. My gorgeous little girl, with unbrushed hair, walked around shirtless in overalls and mud boots, a yellow plastic sand toy shovel in one hand.

The couple had heard about our wedding favors and had arrived to order in person. He and my husband talked about Ford pickups while I chatted with the woman. She kept looking around, distressed. It’s just so muddy, she kept saying. How do you stand it? Where she cringed from dirt and inconvenience, I saw sunlight so intensely bright it lay like shining gold coins on the shallow dips of water that spread out all around our house, as though we were a ship on a rippling sea. I knew mud as the world’s thrust from winter to spring, the give from one season to another. My heart lightened with joy at the end of a bitter cold season and the imminence of wildflower season. I knew coltsfoot would shortly bloom.

…Soon it will be the sky of early spring, stretching above the stubborn ferns and

violets.

Nothing can be forced to live.

The earth is like a drug now, like a voice from far away,

a lover or master. In the end, you do what the voice tells you.

It says forget, you forget.

It says begin again, you begin again.

– Louise Gluck, from “March”

March 3, 2016

Sunlight and Sweetness

When my daughter was two, I picked up a copy of Jeffrey Lent’s novel In the Fall in Montpelier’s Bear Pond Books and began reading. My child was on my back, and I stood so long she nudged me with her feet, a way she had of prodding me along when the scenery dulled for her. I bought the book and walked down Main Street, the pages open in my hands.

Reading that novel was like nothing else I encountered. I was scraping and painting the kitchen windows that summer, and I abandoned that work, sitting on the porch steps, reading, reading, while my child ate watermelon, strewing gnawed rinds over the grass. Halfway through the novel, the language became incantatory in my mind, rising and singing. When I finished the book, I studied the paperback cover, pondering the beauty and mysteries of this book, the sheer grace of its enormous hard work. The novel’s ending remains one of my most beloved.

Why I write all this is not just to rave about this novelist (if you haven’t read him, how lucky you are – you can read his books for the first time), but for this:

With vivid and richly textured prose, Brett Ann Stanciu offers unsparing portraits of northern New England life well beyond sight of the ski lodges and postcard views. The work the land demands, the blood ties of family to the land and to each other, the profound solitude that such hard-bitten lives thrusts upon the people, are here in true measure. A moving and evocative tale that will stay with you, Hidden View also provides one of the most compelling and honest rural woman’s viewpoint to come along in years. A novel of singular accomplishment.

–– Jeffrey Lent

Very often a writer’s life is plagued with burrowing doubt and uncertainty, laboring in a society that values tax bracket far above art. And then, sometimes, you feel you might just have hit the mark. Infinite gratitude.

March woodpile, Woodbury, Vermont