Stephen H. Provost's Blog, page 8

July 31, 2018

Highway 99, the Lost Chapter: Trucks and Truck Stops

Sometimes, you can't squeeze everything in. You've done your research and you've found a lot of interesting stuff - too much, in fact, to fit in the pages of the book you're writing. So, something has to go.

Highway 99: The History of California's Main Street originally included a few sections that ultimately failed to make the cut. I had to leave out an entire chapter on big rigs and truck stops that I'd intended to include, but which wound up being sacrificed when the manuscript wound up being longer than I'd intended. So here it is, the "lost" chapter, presented here for the first time with the photos I originally chose to illustrate it. Enjoy!

(If you like what you read here, Highway 99 is available for purchase on Amazon or through the publisher at quilldriverbooks.com)

A big rig passes an old motel sign at Desert Shores along the former U.S. 99, now State Route 86, at the western edge of the Salton Sea. © Stephen H. Provost, 2014.

More Than Four Wheels

You can’t get too far on the highway before seeing a “Divided Highway” sign. In some places, 99 is divided by a center median, often landscaped with oleanders or other shrubs. But there’s one kind of division you’ll find on the highway no matter which stretch you’re traveling: the division between vehicles with four wheels and those with 18 (give or take a few).

It’s hard to miss the big rigs, buses, tractor-trailers and the like that are so common on the highway. For years, 99 has served as the economic backbone of the state, passing through fertile farmland and industrial centers alike. Warehouses, grain silos and distribution centers line the highway. In the days of the federal highway system, it didn’t matter whether you were transporting raisins from Selma or dates from Indio: U.S. 99 was the way to go.

Still, even today, if you’re behind the wheel of a Mercedes or a Mazda, you might not pay much attention to the infrastructure built around the trucking industry. The average motorist might cross the Tehachapis without taking much notice of signs with messages such as “6% grade 2½ miles ahead” and “Trucks use low gears.” Trucks are supposed to observe a lower speed limit and keep to the right, so swifter automobiles can pass. Runaway truck ramps, with their heavy gravel to slow down out-of-control big rigs, are visible on the downslope from Lebec heading north toward Grapevine. You’ll see the first one on your right, a little more than three miles north of Tejon Summit, and the second on your left less than a half-mile later.

In the highway’s early days, without such precautions, accidents were far too common and, often, tragic. The original Ridge Route had more than its share of hairpin turns hugging steep cliff walls; a single mistake, even at 15 miles per hour, could be catastrophic, and the white picket fences that served as guardrails around dangerous turns were hardly sturdy enough to keep heavy truck from lurching over the edge. The 180-degree hairpin called Deadman’s Curve between Lebec and Grapevine was particularly treacherous.

Once the Ridge Route Alternate was built, the straighter highway reduced the danger of missing a turn but raised a new threat: The straighter road meant trucks could build up a head of speed going downhill that made them even more dangerous if their brakes started smoking and failed unexpectedly.

In 1946, The Bakersfield Californian detailed a truck’s “mad plunge” just before midnight one July evening. It went out of control and sideswiped a passenger car, sending it off the highway and leaving the driver shaken but uninjured. The truck careened on toward Grapevine, where it slammed into the rear of a van, propelling it into a row of gasoline pumps and three other cars at the Richfield filling station. The truck, meanwhile, kept going, plowing into yet another car and shoving it to the edge of the embankment, where both vehicles burst into flames. A passenger in the truck was burned to death, its driver suffered a broken leg, and the driver of the final car to be hit was hospitalized with severe burns.

Other news reports told similar stories. Out-of-control trucks became, as one writer put it, “juggernauts of death” on a stretch of highway that was fast becoming known as Bloody 99: the steep grade just south of Grapevine. During one 10-day stretch in 1943, that single section of road bore witness to nine runaway truck accidents.

Engineers added a concrete barrier to keep trucks from swerving into oncoming traffic, and other proposals surfaced as well. One involved requiring trucks to stop at the summit and switch into low gear before descending, though critics argued that this would merely back up traffic and create a new hazard.

The café, garage and 76 station at the bottom of the Grapevine Grade bore witness to numerous crashes, as trucks came barreling down the incline and careened off the roadway. Photo courtesy Ridge Route Communities Historical Society.

The Grapevine Grade wasn’t the only trouble spot. The Five Mile Grade, heading the opposite direction near Castaic, was also the scene of numerous brake failures and truck crashes. A runaway truck ramp, like those above Grapevine, was built in the 1950s to reduce the number of accidents, but it only remained in use until 1970. It was then that a freeway upgrade created a novel alignment: New southbound lanes were added, following a gentler downward slope to the east, while the old southbound route was converted to carry northbound traffic. As a result, drivers traveling over the five-mile stretch between Castaic and Violin Summit progress British-style, on the left of oncoming traffic. (A significant gap separates the two segments of roadway).

The emergency ramps came in handy, not only for truckers, but also for law enforcement. On at least one occasion, one of the ramps Grapevine Grade halted more than a runaway trucker: They stopped an accused runaway kidnapper. In January of 2008, Highway Patrol officers and Los Angeles responded to a report that a man had assaulted his estranged wife and abducted their child, making his escape in a stolen truck. The officers pursued the suspect northbound over more than 70 miles from Highway 101 onto Interstate 5 before the chase finally ended just north of Grapevine. It seems the man mistook one of the runaway truck ramps there for a highway exit and found his vehicle immobilized by the coarse gravel.

He was arrested immediately.

One reason the trucks can be so dangerous on a steep downhill slope is their weight. Big rigs can weigh up to 40 tons, compared to the typical car at only 2½ tons. Once they get going at highway speeds, they can require two-thirds more pavement to stop once the brakes are applied – if the brakes are working. That’s part of the reason California requires trucks rated above a certain weight (currently 11,500 pounds) to stop at scales cleverly designated as “weigh stations.” And it’s no accident that two of the eight or so weigh stations along the historic U.S. 99 route can be found at either side of the Tehachapis, just south of Castaic and slightly north of Grapevine.

The state recognized the need for scales early. In 1938, officials set up a 24-hour truck-checking station at Fort Tejon, near the point where the 99 began the steepest portion of its descent into the San Joaquin Valley. Highway Patrol officers were on hand to make sure loads were within limits defined under state law. “This station,” the California Highways publication declared, “will not only guard against overweight loads, but will also enable the traffic officers to insure that trucks using this mountain route are in good running order, and that all their braking equipment is working properly.”

A small truck scale business operates at the northbound entrance to Highway 99 off Herndon Avenue, north of Fresno. © Stephen H. Provost, 2014.

Private scales operated by companies such as CAT also opened up and down the highway, with nearly two dozen along the old 99 route between Los Angeles and the Oregon border as of 2014. Such private operations help ensure truckers’ loads are below the legal weight limit. CAT, for instance, offered this guarantee on its website: “If a driver receives an overweight fine after weighing legal on a CAT brand scale, CAT Scale Company will either pay the fine or appear in court with the driver as an expert witness in order to get the fine dismissed.”

Scales are far from the only highway business to have emerged in support of the trucking industry. As the nation shifted from the railroad to the highway as its primary means of transporting goods, a new industry sprang up to support the drivers who spent days away from home, driving long hours cross-country. They needed places to spend the night, to clean up, to grab some coffee and get a bite to eat. They also needed a place to buy the kind of fuel their semis ran on, diesel, which wasn’t always available at traditional gas stations.

Truck stops sprang up to fill these needs. Some establishments that catered to travelers and tourists, such as Sandberg’s, refused to serve truck drivers. But other stops along the old Ridge Route and elsewhere offered various combinations of a garage, cheap accommodations and a diner or coffee shop that suited truckers pretty well. As time passed, some roadside establishments started catering specifically to truckers, seating them first at the lunch counter or offering them a place to shower in the back.

When it came to sleeping arrangements, truckers had to make do. During the early years, some stayed at roadside auto camps, and many roughed it by sleeping in their vehicles, whose wooden seats were anything but the epitome of comfort. Anything more elaborate was usually improvised, and not necessarily any more comfortable. One San Joaquin Valley-based company rigged up a couple of ’22 Packards with wooden boxes over the cabs where the relief driver could sleep. The casual observer might have feared an appearance by Dracula at any moment.

By the mid-1930s, however, a few manufacturers had started offering sleepers as part of the package. The wooden boxes gave way to so-called “coffin sleepers,” cramped quarters usually placed directly behind the cab. These compartments might have been 2 feet wide by 3 feet tall, giving the occupant barely enough room to turn over. Drivers with claustrophobic tendencies need not apply.

In the early 1950s, Kenworth offered a CBE model, which stood for “Cab-Beside-Engine.” The CBE design included a sleeping space for the relief driver between the cab and the engine, a configuration that earned it the nickname “suicide sleeper”: Few occupants could expect to survive a crash while they slept right next to the engine.

As trucks gained horsepower and gained load capacity, there was often no longer room for them at the inn. Many early motor courts included carports alongside their cabins, but they were called CARports for a reason: They didn’t provide enough clearance for trucks. Drivers ran into the same problem at some service stations, where canopies built to shield pumps from the elements were often too low to allow larger trucks access.

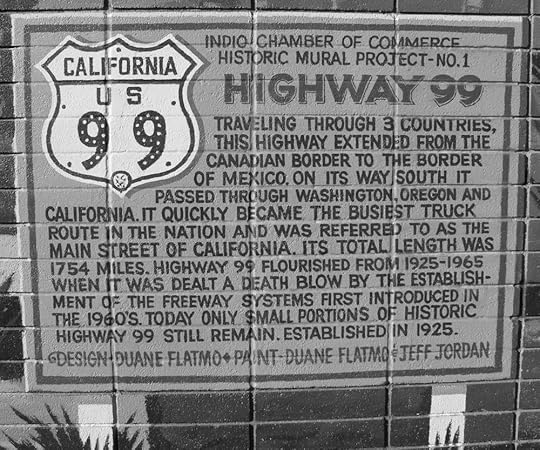

A mural outside Clark’s Truck Stop in Indio celebrates the history of U.S. 99. © Stephen H. Provost, 2015.

Truck stops offered an array of services that establishments catering to the auto traveler did not.

Many of the earliest among them, like the earliest motels and gas stations, were independent operations, but larger companies soon entered the fray once they realized they were missing a large segment of the market. Flying A’s flat-top station in Fresno, with its 110-foot “GAS” tower on the west side of 99, was a prime example of an early truck stop. The canopy was 70 feet high, providing ample room for trucks – which got their own separate entrance. Diesel fuel was available; there was a “completely equipped” truck lube pit, a public scale capable of weighing the largest truck on the road, and free shower rooms for all truckers. The expansive parking lot provided room for truckers to park their rigs and get a few hours’ worth of shuteye.

The station was still there until recently (having been removed to make way for the new high-speed rail line), although it sold Valero gasoline at the end, as does another venerable establishment, Clark’s Travel Center in Indio, offering “everything for the traveler, whether you are an RV’er, trucker, river rat or desert rat.” Amenities include a truck wash, long-term parking, self-service laundry, 24-hour restaurant and car-truck wash. Clark’s, which opened in the 1940s, advertises itself as “the oldest operating truck stop on historic Route 99 from Canada to Mexico.”

Klein’s Truck Stop at Herndon Avenue north of Fresno had a reputation among locals as serving some of the best breakfasts in town. But truckers were the most valued clientele: They were always served first. © Stephen H. Provost, 2014.

The restaurant at Klein’s Truck Stop in the hamlet of Herndon, just north of Fresno, earned a reputation for serving among the best breakfasts around. The restaurant stayed open into the new millennium before finally closing its doors, yielding to a Taco Bell and an am/pm minimart while maintaining a huge parking lot as a place for truckers. One traveler from Los Angeles endorsed it by stating that, no matter how hungry he might be, he always held his appetite in check if he were within 50 miles of Klein’s.

Despite its popularity among the locals, there was no mistaking its target audience: the truck driver traveling the Main Street of California. When a truck driver came in, the hostess would usher him to the head of the line. The waitresses wore beehive hairdos, and each table had its own jukebox, offering up (of course) country music. The cooks made the kind of all-American fare that kept the belly feeling full for hours: hearty portions of chili, barbecue dishes, chicken-fried steak, their famous biscuits and gravy, and “pancakes as big and flat as Fresno.”

As time passed, places like Klein’s were eclipsed by truck palaces called travel plazas or travel centers, giant complexes along 99, I-5 and other major highways that were affiliated with big chains. And as the complexes grew bigger, a funny thing happened: Suddenly, they weren’t just for truckers anymore. Convenience stores served as many travelers as truckers, selling touristy T-shirts and CDs alongside motor oil and citizens band radio accessories.

Flying J, with four locations along the old 99 route, offered such amenities as Subway and Denny’s restaurants, 14 showers, a CAT scale, public laundry, video game arcade and ATMs at its site north of Bakersfield. Pilot, which bought out Flying J and had six locations along the old highway route as of 2014, offered another option, as did Petro Centers (four), Love’s Travel Shops (four) and TA Travel Centers (five).

The Flying J Travel Center at the Frazier Park exit from Interstate 5 is a convenient and popular midway point to gas up and get refreshments between Bakersfield and the San Fernando Valley. © Stephen H. Provost, 2014.

May 24, 2018

Media Meltdown: Blurb for my new book

Here's the blurb for my forthcoming book, "Media Meltdown in the Age of Trump," due out June 1. Pictured above is the full cover:

Some politicians use the media to their advantage. Others reshape it in their image.

Had the political force that is Donald J. Trump met the immovable object that was the American news media in the 20th century, the result would have been predictable. Trump would have vanished without a trace, along with such wannabes and also-rans as Edmund Muskie, Howard Dean, Gary Hart and John Edwards.

Today, however, the once-powerful Fourth Estate might as well be in foreclosure, shattered into a million pieces by cable television, talk radio and the internet. Newspapers, their stranglehold on information broken, are on life support. Gutted by cost-cutting and consolidation, they see the very same digital platforms that crippled them as their last, best hope for salvation. Television news, meanwhile, has descended from Cronkite and Brinkley into a three-ring circus of breaking news and talking (or shouting) heads.

Trump, a carnival barker of a president, has taken for himself the role of ringmaster, using his chaotic style and the power of his office to dominate the spotlight. At once condemning and exploiting the media, he's transformed the presidency into a reality show, complete with multiple scandals and cliffhangers to keep everyone tuned in.

He didn’t arrive out of nowhere. The way for his ascent was paved by the media themselves, hungry for drama to stoke ratings and boost subscriptions. When cable and the internet began siphoning off readers/viewers by targeting their built-in biases, the nation became polarized and the gloves came off. Civility was sidelined, spin became the MVP, and the referees – the mainstream media – were benched.

This is the story of how carnival journalism has supplanted and, in some cases, co-opted what’s left of the mainstream media, and how politicians like Trump have both fueled and profited from the change. Is any of this good for the nation? A game without a referee might be more fun to watch, but is it fair? Media Meltdown provides some of the answers.

February 23, 2018

Nightmare's Eve: About My New Collection

Connoisseurs of the murky and shadowy side of our existence often seem at pains to define the word “horror.” Too often, it brings to mind the B movies unleashed on us every year at Halloween. Or the grainy black-and-white “classics” they used to tuck away at the upper end of the UHF dial on weekends between midnight and 3 a.m. All bloodletting and jump scares and shaky cameras. I’ve never been much for any of that, because (for one thing) it always seemed like a wilted daisy chain of clichés and (for another) it didn’t scare me.

Jump scares startle, they don’t scare. Shaky cameras make me queasy, and blood loses its impact when it spews out all over the place like Old Faithful.

This kind of thing, admittedly, does scare some people. Everyone’s different. But blood and gotcha scenes and monsters don’t add up to horror in my book — which is one reason I never really thought I’d write horror. It’s a bit of a surprise, to be honest.

It may surprise you, too, if you’ve read some of my other material, say the whimsical Feathercap or the uplifting Undefeated. In many ways, Nightmare’s Eve is the antithesis of the latter, which is a series of true stories about people who overcame seemingly impossible odds. The stories in Nightmare’s Eve aren’t true — and thankfully so, because most of them involve odds that really, truly are impossible.

The essence of horrorThat’s where my definition of horror begins. It’s got nothing to do with monsters or gore, specifically. It’s all about what scares you. True horror dawns when you realize that you’re somehow “on the wrong side of things” ... and there’s no realistic way that you’ll ever get over to the right side again.

Horror is being trapped, hopeless, desperate. It’s that sickening feeling that rises up from the pit of your stomach when you recognize there’s no way out. And isn’t that true for all of us, really? You’re stuck there in that body of yours, and you won’t be getting out of there alive now, will you?

But horror is about more than death, it’s about that inexorable journey toward it. Our survival instinct demands that we claw and rage against it, but our very resistance to the inevitable can make it all the more tormenting. In fighting a battle we cannot win, do we merely prolong our agony as we fall apart piece by piece, inexorably? What would be, to you, most terrifying? To lose your freedom? Or your memory? Perhaps a loved one, or your ability to separate reality from illusion. When the things we love, we count on, we take for granted are stripped from us one by one, with no hope of ever recovering them … that is the true, naked aspect of horror.

Horror is the dawning of hopelessness, in that twilight time between waking and sleep when fear and panic mount for we who find no solace in slumber. For those of beset by nightmares that visit us anew each time we close our eyes. We cannot make our eyes remain open forever, yet as we surrender to exhaustion, the Sandman shows no mercy — but throws open the doors of our inner mind to madness.

From The Twilight ZoneThe stories and verse you’ll find in Nightmare’s Eve will strike a familiar cord to those familiar with The Twilight Zone. They’re stories of ordinary people in the present day, extraordinary people from the past and imaginary people from a not-too-distant future that might be. Some hope does manage to seep in, on occasion, a solitary beam of sunlight creeping through the blinds into the dusty, vacant prison that is our soul.

What will it illuminate? A way out of the maze, or another dead end?

And a maze it is, this journey, with twists sometimes ironic, sometimes terrifying ... but always unexpected.

There are tales of the occult; of two renowned and noble saints (one named Nick, the other George); of fate and vampires and space exploration. Of psychic powers and time travel; of malevolent entities and genies and dragons and man’s best friend.

This work began as a small collection of three stories: Turn Left on Dover, Will to Live and A Deal in the Dark. The first of these, also the first written, contains a character for whom I named my cat, Allie (not Alley, as in Alley Cat, as many often suppose). It takes place in a city modeled after my hometown. And if you don’t know where that is, just pick up a copy of a very different book I wrote titled Fresno Growing Up.

The collection expanded gradually over the course of about four months to include 16 tales and 10 poems. I’ll share below the table of contents to whet your appetite for a journey that isn’t for the faint of heart or heavy of foot. You’ll want to have a spring in your step for what lies ahead. Read it before bed if you dare; it’s designed keep you awake at night.

TalesA Deal in the DarkWill to LiveJust the TicketTurn Left on DoverMamaBreaking the CycleVirulentAnatomy of a VampireThe Ends of the EarthThe Howl and the PurrTeethThe Faithful DogLamp Unto My FateNightmare’s Eve (Rotten Robbie's Christmas Comeuppance)Stranger Than FictionGeorge & the Dragon: The Untold StoryVerseCertitudeLost SoliloquyUnwoundUpon ReflectionMerlin's LAmentBleed NotLost at SeaTorrent of TearsA Never-Setting SunThis Vale of DreamsFebruary 10, 2018

Catchphrase fatigue: Why buzzwords lose their sting

“Why are people talking like that?”

I ask that question a lot, especially when I see some new linguistic trend go viral … the way the term “go viral” went viral, for instance.

The answer I get most often is: “Get over it. Language is always evolving.”

Perhaps. But the process has accelerated since the advent of social media, which introduces new mutations to the literary gene pool at a frightening rate.

Buzzwords and catchphrases used to be appear every so often, then fade gradually from our consciousness over the ensuing decades. One generation might say “keen,” another “groovy,” and another “cool” or “awesome.” We’ve always been prone to putting our own stamp on things by creating synonyms, but these days, new words appear, wear out their welcome and vanish at a dizzying pace.

Media in general, and social media in particular, have given us all immediate access to a national (or global) conversation. And this conversation has introduced us to words and phrases that, in the past, might have spread slowly or never caught on at all. Some remained confined to one region or another: Many words and phrases that “go viral” in the 21st century would have been subject to a natural geographic quarantine a few decades ago. “Y’all” has become more than a Southern affectation; and “dude” is no longer confined to the SoCal surfing culture.

Filter removedMaybe that old-fashioned quarantine was a good thing. Widespread access to the internet —and social media in particular — has removed a filter that kept the language relatively stable. Now, it careens all over the place like a pinball. Buzzwords can go rolling down the black hole at the bottom of the table without warning. Or they can get stuck between two bumpers in a frenzy of repetition that tries the patience of the most dedicated arcade aficionado.

It’s not evolution so much as mutation mania. Words and phrases become so pervasive that they can go from innovation to aggravation in a matter of months — or even weeks. That’s one thing about a virus: You get sick of it damn fast.

Are you already sick of hearing words like these: woke, snowflake, (blank)splaining, mindful, bae, GOAT, cuck? I know I am. How about phrases such as “fake news”? Some words seem to have been made up out of whole cloth; others are borrowed from the existing lexicon and reformatted with new or narrower definitions. “Privilege: comes to mind.

New and redefined words appear out of nowhere and leave us scratching our heads, asking ourselves, “What the hell does that mean?” That question soon gives way to a plaintive plea as we’re bombarded with these buzzwords time and again: “Please, make it stop!”

Redundant punditsFurther frustrations stem from the fact that some of these words don’t add anything to the language. We already have words for them. You can find them in any good dictionary. But we’ve put down our dictionaries because we’re too busy creating new entries for our own personal thesaurus. We’ve become redundant pundits.

Woke? Mindful? What’s wrong with just being aware? (“Woke” is particularly galling because it appears to be a bastardization of the perfectly good adjective “awake.”) And you don’t need to talk about ’splaining when you know the meaning of condescension. Are four syllables too many for you? (Yes, I know that last remark was condescending. I’m making a point.) Once upon a time, we called fake news propaganda … or bullshit.

Then there’s "privilege," which has become pervasive in the lexicon as a pejorative term against a person’s status. Once upon a time, we denounced people’s actions and attitudes — bigotry, racism, chauvinism, etc. Now, instead of condemning them for what they do, we berate them for who they are. They’re “privileged.” But isn’t this, ironically, just another form of bigotry? Because the target’s different, it’s supposed to be OK.

Really?

Adapting words like "Nazi" and "retarded" — a la "feminazi," "Grammar Nazi" and "libtard," for example — is distasteful, to say the least.

His jargon conceals, from him, but not from us, the deep, empty hole in his mind.

— Richard Mitchell, Less Than Words Can Say

“Snowflake” implies that it’s bad to be different. I don’t buy that: Conformity for the sake of conformity is downright dangerous. “Cuck” is just rude, and “bae” is … well, I don’t know what it is.

GOAT is a funny one. As an acronym, it’s short for “Greatest Of All Time,” and it’s become pervasive in sports commentary. But once upon a time, it meant virtually the opposite: A goat was someone who made a mistake that cost his team the game. Talk about confusing!

How many of these terms and definitions will still be in use fifty, twenty or even ten years from now? My hunch is that most of them will wear out their welcome and become fading footnotes in the evolution of the English language. That’s how evolution works, if you think about it: The vast majority of mutations aren’t helpful; they’re damaging or, at best, irrelevant.

Keep that in mind the next time someone defends the latest new buzzword on the grounds that “language is always evolving.”

Most mutations backfire. And most of these buzzwords are better off going extinct.

January 12, 2018

Literacy on life support: The decline and fall of written language

Motion pictures didn’t kill writing. Neither did television.

We who love the written word took comfort in the fact that authors such as Stephen King, J.K. Rowling and Dan Brown could still use it to captivate mass audiences. Good writing was alive and well, we thought. Reports of its demise were premature and, we believed, greatly exaggerated.

Or were they?

Death can come suddenly, but far more often, it creeps up on us. It hides in the shadows of our own denial. Lurking there, it bides its time, numbing us to the signs of its looming presence. We barely notice that we’ve embarked upon a long, slow walk toward our demise. Our decline is subtle, our transformation gradual.

One day, we stop running. Farther down the road, we labor to walk … and then to stand. If we notice this regression, we do so reluctantly. Fatigue whispers in one ear and apathy in the other: “Accept it. Ignore it. It’s not really as bad as it seems.” And so forth. We acclimate to a “new normal” and forget what the old normal was, because it’s too painful to remember and even more painful to pursue — until, at last, it eludes our grasp entirely.

Movies weren’t the end of books, and television didn’t kill magazines or newspapers, but the regression from the age of literacy continues apace — indeed, accelerates. This is no seasonal illness; it’s become a chronic condition, and the symptoms are no longer just a few, but myriad.

We favor sound bites over policy proposals.We accept tweets as our favored form of prose and elect their foremost proponent as our president.We shutter bookstores, and we learn about novels only when Hollywood makes them movies; then we don’t bother to read them, because we’ve seen the ending on the big screen.We value “keywords” over complete sentences.When we go online, it isn’t to read; it’s to “game” or to veg out on YouTube.Romantics used to send love letters by parcel post; now players send “dick pics” by email.Editors? Who needs them when we’ve forgotten proper grammar? Who has time for them when we demand our information now.Newspapers? Ink on your hands and waste for the landfill.Magazines? Exiled online, if they survive at all, ghosts in the same machine that slew them.If literacy isn’t dead, it’s on life support. You can’t read if there aren’t any writers, and there won’t be any writers if no one pays them — if they’re too busy marketing, posting and promoting to knock out that sequel you’ve been waiting for. The more time writers spend doing the work of agents and editors, publicists and promoters used to do, the less time they’ll have to actually write. The more rushed and the less robust their stories will be.

How can we create memorable prose when it disappears in the blink of an eye on Snapchat? Will any library preserve the tweets and texts of this impulsive generation?

Readers have it in our power to provide the answers. It is we who create the demand, or refuse to, and the supply increases or dries up in response to our decisions. That’s just the way it works.

Downhill trajectoryIn the world we’re fashioning, we value tweets and memes and Facebook Live. Quality writing? Not so much. You might want to debate that point, but until you’re willing to do so with your pocketbook, it’s all just empty noise. Yes, there are exceptions. Some people still make a living by writing, even a comfortable one. This proves nothing. A patient with a chronic, wasting illness still enjoys occasional “good days” and periodic bursts of energy. They’re no proof that the patient is any less ill, the condition any less serious.

Such “good days” will become less frequent with the passage of time, until at last they’re whittled down from few to none.

Is that what will happen to literacy? Time will tell. It would be cruelly ironic if some hothead’s reckless tweets were to result in a catastrophic war — a war that might reduce our “information superhighway” to cyber-rubble. Such a tragedy would obliterate our carefully crafted virtual world of denial and convenience, and if that were to happen, we might need writing again, just to communicate.

Literacy is a bridge from misery to hope. ... Literacy is, finally, the road to human progress and the means through which every man, woman and child can realize his or her full potential.

— Kofi Annan

This is not to suggest that our only choice lies between a nuclear and literary wasteland. Far from it. With some luck and just a little restraint, the nuclear button will never be pushed, and we can avert a literary apocalypse, as well. There are, after all, alternatives. Most notably, we could celebrate writing again — something we haven’t been doing.

We denigrate reporters as purveyors of “fake news,” dismiss authors as hobbyists and degrade those who instruct us in the language by quipping, “Those who can’t, teach.” Is writing really a marketable skill? Shouldn’t university students be taking practical courses like business, engineering or computer technology?

Such thinking could lead us to a real-life Tower of Babel, that engineering marvel from the realm of lore that remained unfinished because all those talented architects and builders forgot how to communicate ... just as we're doing right now.

But what if, instead of devaluing the written word, we exalted it once more and encouraged those who sought to master it? What if we invested in the authors and reporters and editors and English teachers who have made it their passion? The more we value writing, the more people will aspire to fill these roles; the more accomplished those people will become, and the greater the rewards will be, not only for those who read their work, but for society as a whole.

That’s not fake news. You have my word(s) on it.

December 6, 2017

Why I don't write negative book reviews

I have a simple policy when it comes to reviewing books: If I like them, I give 'em props. If I don't, I keep my mouth (or my keyboard) shut.

There are a couple of reasons for this. First off, reactions to books are largely subjective. Some books are more popular than others, and that can speak to quality, but it also can speak to successful marketing, name recognition and other factors. A few highly praised works have bored me to tears, and some obscure volumes have been, to use my wife's term, "unputdownable."

(This is a great word, even if you won't find it in the dictionary, because it has two meanings: The book's so engaging you can't stop reading it, and it's so enjoyable, you can't find anything to criticize.)

Secondly, I like to support other artists. I know how hard it is to sell a book, and I also know how tough it can be to deal with numbing criticism from strangers who seem to take almost perverse glee in dismantling a work you've spent months or years creating. You put a big part of yourself into it, and it's hard not to take it personally if someone reams you over it. Having been on the receiving end of slow sales and (only occasionally, thank goodness) critical reviews, I know what it's like to feel that sting, so I strive to follow the Golden Rule and spare other authors any scathing rebukes from my pen.

From my close observation of writers... they fall into two groups: 1) those who bleed copiously and visibly at any bad review, and 2) those who bleed copiously and secretly at any bad review.

— Isaac Asimov

The Grammar Hammer

What about more objective issues? What if the book contains a ton of misspelled words, switches tenses in the middle of a chapter or treats subject-verb agreement like it's a temporary truce at best?

As an editor, these things drive me nuts, but what's even more galling is a review that consists largely or solely of grammatical critiques. Such reviews come off as holier-than-thou, and they tell me nothing about the plot or the characters. Reviewers: I want to know what you think of the story. I won't give you a gold star for digging up the most errors in some fanciful literary scavenger hunt.

So, I won't blast an author by name in a public forum for using "it's" as a possessive or "comprise" instead of "compose," even though I may grind my teeth and roll my eyes when it happens. Those things aren't as important to me as the story, and no author can catch every mistake. (In fact, we tend to read right over our own typos, seeing what we think we've written rather than what's actually on the page. That's why we need editors. And it's why I'm more likely to hold an editor accountable for a slew of errors than I am to blame the writer.)

If I have a criticism of a book that I believe is worth sharing with the author, I do so in private, not in a review. I may poke fun at grammatical mistakes on line, but I don't attribute them to particular writers. I like to say, as a professional editor, that I'm not getting paid to do that, but the reality is, I don't find shaming writers to be either fun or noble. I'd much rather encourage them.

Ask yourself: of all the jobs available to literate people, what monster chooses the job of “telling people how bad different books are”? What twisted fetishist chooses such a life?

— Steve Hely, How I Became a Famous Novelist

What makes a good review

So, how do I go about writing a constructive review? Here are a few things I try to include:

What's special about the story? What makes it stand out from the crowd?You'll enjoy this book if you've enjoyed ... (fill in the blank with one or more similar titles you've enjoyed.)Who was your favorite character, and why?What did you like about the writer's style? Did the description stand out; if so, how? Was the dialogue crisp and realistic? Was there a twist you didn't expect?If the book was "unputdownable," say so!If I do include any critical info, I build it on a positive foundation. For example, "I enjoyed this character so much, I would have liked to see more of her. I hope the author considers telling readers more about her in a sequel."

And, of course, no spoilers.

But wait, you may say, "If you never leaves a negative review, how will potential readers know if the book isn't for them?"

That's easy. The descriptions you give might be positive, but if you mention elements of the book that appeal to some readers, these same ingredients might not interest others. If you describe the story as fast-paced, readers who don't like to feel rushed through a story line might pass. If you highlight a passionate relationship between the two main characters, that might flag those who aren't into romance to steer clear. If you label it "dark and brooding," that might not appeal to readers in search of an uplifting tale. And so on.

Believe it or not, eliminating readers who wouldn't be interested in a particular book benefits the author, too. It means that those who do read the work as the result of a review are more likely to enjoy it ... and leave a review of their own.

A bad review is even less important than whether it is raining in Patagonia.

— Iris Murdoch

A lousy review isn't the end of the world, which should come as good news to authors and bad news to self-important critics who think of themselves as king-makers and book-breakers. S. Kelley Harrell calls online review sites "the slushpile of feedback," and Iris Murdoch said, "A bad review is even less important than whether it is raining in Patagonia."

If you're an author with a leaky roof who happens to live in Patagonia, that might be a concern, but otherwise ...

A positive review probably won't make you a bestselling author, either. Still, I love getting them; most authors do. If you don't have time to leave a review, but you like a book, just rate it. That's great, too. It shows that you've read the book and (hopefully) that it kept you interested enough to reach the end.

Speaking of the end, I've gotten there myself. At least for today.

Thanks for reading, and happy reviewing!

November 29, 2017

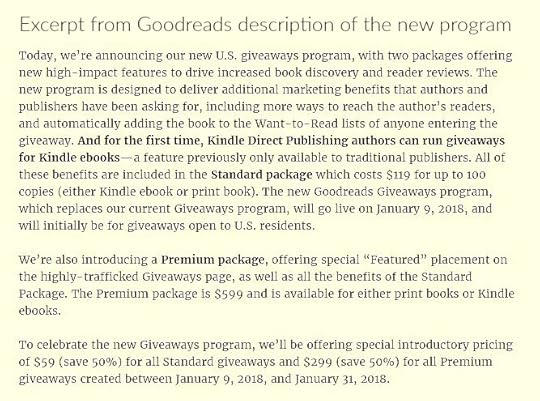

Goodreads to authors: Pay $600 to give away a $10 book

Hey, fellow authors, Jeff Bezos is laughing at you ... all the way to the bank.

Bezos is already the richest man in the world, but that’s not stopping him from making a few extra bucks off the proverbial “starving” authors.

Until now, Goodreads has offered a free service allowing authors to promote their books via giveaways. (They weren’t really free, as the authors were, giving away their books, but Goodreads didn’t make any money off it).

No more.

As an author who’s run Goodreads giveaways in the past, I received an email this morning about a new program that’s being touted as “a more powerful book marketing tool for authors and publishers.” Of course, there’s a catch: This new program will charge authors $119 bucks to run a “standard.” And if that’s not enough money to line Bezos’ (or his shareholders’) gilded pockets, you can run a “premium” giveaway for the bargain basement price of $599 smackeroos.

I call them Goodreads Takeaways.

Bezos, who just became the world’s only $100 billion man, is the founder and CEO of Amazon, which purchased Goodreads back in 2013.

Like he needs the money, right?

Forgive the sarcasm, but when you’re struggling to promote a book that sells for $10, it’s hard to get excited about paying 600 bucks just to give the damn thing away!

Any faint hope that these new packages would be somehow optional upgrades is quashed in the first paragraph of the email, which states that the new program “replaces our current Giveaways program.”

Of course, Amazon … er … Goodreads is touting enhanced features of the new packages. The standard package get “a notification letting them know there’s a giveaway starting.” Oh, goodie! Let me jump up and down a little bit higher.

And if you buy the premium package, you’ll get “premium placement in the Giveaways section.” Translated, this likely means that unless you dish out the $480 extra for the premium package, your giveaway will be buried.

(None of this is really much more than the giveaways offer now.)

I’ve paid to promote my books before. I’ve spent money on gas to drive to book signings. I’ve invested in posters and bookmarks and postcards. But I’ve never paid hundreds of dollars for the “privilege” of giving my books away, and I'm not going to do it now. That’s where I draw the line.

Oh, but the exposure!

I’m sorry, but I get paid to write. I get paid a decent salary to write in my day job, and I don’t value my work as an author any less. I'm not going to pay to do it. I'm not a flippin' vanity press.

As Wil Wheaton said when he was asked to contribute his work to Huffington Post in exchange for exposure, “How about no.”

That’s my answer to the new Goodreads Takeaways, too. They take money away from authors and give them to the richest man in the world.

Not just no. Hell no.

Let Goodreads know what you think: Take the survey here.

August 30, 2017

Why time travel doesn't work

Time travel. Whether you’re reading H.G. Wells or watching Capt. James T. Kirk “slingshot around the sun” in the U.S.S. Enterprise, and it’s always a lot of fun. “What ifs” make for great stories, and time travel opens up a vast trove of possibilities.

Still, it’s just fiction. We can’t actually do it, and here’s why.

I’m no physicist, but I know the difference between an object and a unit of measurement. The first is tangible in a very real way; the second is merely a convention. It’s a human construction, entirely artificial and fully dependent on the thing it’s designed to measure.

We create such constructs all the time. They help us make sense of the world.

The words you’re reading right now represent real things. The word “box” represents a real object, but the word is not that object – and apart from the object it refers to, it would be utterly meaningless. We could have just as easily called that object a Heffalump or a Bandersnatch. Whatever we decide to call it, as long as we all agree that the word in question represents a cube-shaped object with a hollow interior, we’ll understand one another just fine … which is the purpose of communication.

The same is true for numbers. Numbers don’t exist in and of themselves; they measure things that exist. We can use Roman numerals, Arabic numerals (our own system). We can use a base-10 system, a base-5 system or whatever. Our choice. The things we’re numbering remain the same regardless of the labels we place on them, and we can’t count anything unless we have something to count.

Say we’re measuring something in space. We can use inches or centimeters or whatever, but the actual thing we’re measuring – its physical length – doesn’t change, no matter what units we devise to quantify it.

So, how does this apply to time?

Like distance, it’s something we measure, using years, centuries, hours, minutes, etc. We can base our system on a sundial or modify it for daylight savings. We can monkey around with the calendar to create a year of 12 or 13 months if we so choose. For centuries, the Western world used the Julian Calendar, devised by Julius Caesar; these days, we use a calendar promoted by Pope Gregory XIII. But whether we use one or the other has absolutely zero effect on the way Earth rotates on its axis or orbits the sun.

In the same way we talk about “distance” and “volume” to measure length or storage capacity, we use the concept of time to measure a specific aspect of our universe: change.

Without change, there would be no time, because there would be no way to tell the difference between one moment and the next. In fact, there wouldn’t be any moments, per se. The concept of time merely gives us a way to understand and document change; without change, “time” is meaningless, just as the word “box” is meaningless without the thing it describes.

You might argue that it’s still possible to travel forward in time by entering a condition of stasis. This is at least theoretically possible – although the idea of “freezing” and “unfreezing” the human body is problematic in a practical sense and has not been achieved outside of science fiction. But think about it: We’re traveling forward in time anyway, so none of this would really change the nature of the way things work: You’d merely be altering a single physical element – the body – by prolonging its viability. Other than that, change would continue in the very same manner it otherwise would have.

(One could even argue that prolonging average human life span to more than 70 years from just over 30 at the start of the 20th century constitutes a form of forward time travel.)

To “go backward in time,” by contrast, would require far more than simply placing one small element of the universe into stasis. It would mean restoring the entire universe, down to the smallest subatomic particle, to the precise state in which it existed in 1776, 1492, 10 million years BC or whenever you wanted to go. To describe such a task as Herculean would be the biggest understatement of all time (pun intended).

So while it might be great fun to talk about slingshotting your way around the sun and finding yourself back in, say, medieval England or Biblical Judea, it ain’t gonna happen, folks. That’s why they call it science fiction.

It’s also why people like authors and poets, screenwriters, musicians and visual artists are so important. They can take us on journeys beyond the limits of this universe, into the only alternate universe any of us has ever really visited: our imagination.

The trip there and back again is no less a journey of discovery than any other adventure you can …

… imagine.

August 25, 2017

"Bird Box": a thrill ride about ordinary humans in extraordinary crisis

Every now and then, a story is so engaging and deftly told that it overcomes the reader’s own personal difficulties with style and renders the so-called “rules” of writing superfluous. Bird Box was one such book for me. Author Josh Malerman delivers a story that kept me interested from start to finish, which is – in the end – the hallmark of a successful novel.

Although he occasionally falls into a clipped voice (especially in the early going), his quick-hitting style is an asset overall. It’s far better than being sucked into an endless quagmire of unnecessary description, and it fits the story perfectly. It allows the author to build suspense throughout without boring the reader – quite a feat in any novel-length endeavor.

There are a lot of things Malerman doesn’t describe in the book, some of which the reader is probably just itching to know. But the fact that he leaves out these descriptions is a master stroke, because it allows the reader to focus on what’s important: the human story about how people cope (or fail to) and interact in a world overrun by paranoia, false hopes and heroic deeds that sometimes succeed but just as often end in tragedy.

Josh Malerman is an American author and the lead singer for the rock band The High Strung. Malerman currently lives in Ferndale, Michigan.

The premise of Bird Box is ingenious: How do human beings adjust to a world in which opening one’s eyes means near-certain madness? The execution is also first-rate, sometimes in spite of the fact that Malerman breaks the rules - and sometimes because of it.

A writing coach might tell you that Malerman uses variations on the verb “to be” far too much. But it works, and that’s what matters. It amplifies the matter-of-fact narrative, which reflects the crisis situation that pervades the book. This is proof that rules sometimes demand to be broken, when the author does so in service to the book’s mood and plot. It’s to his great credit that Malerman is willing to do so.

The main stylistic problem I had with Bird Box (HarperCollins, 2014) was its reliance on present tense in the two streams of narrative that run through the novel, one present day and the other in the past. For me, it slowed down what was otherwise a tension-filled page-turner of a ride, especially when the writer moved to past tense in the midst of a present-tense section. (None of these moves were wrong, structurally speaking; they just slowed me down a bit.)

Malerman also seems to run short on material for his present-day narrative stream and, as the book goes on, uses it more frequently for flashbacks that aren’t covered in the “past” stream. At times, he does so to provide key information that might not otherwise be available, which is all well and good. In any case, this is a minor quibble and in no way a deal-breaker.

A few questions are left unanswered, such as why some animals go mad and others don't - or why they do so at varying rates, whereas nearly all humans are exposed to the danger that's involved in opening their eyes very early. But this, too, is minor, and not essential to the plot. In fact, Malerman's ability to keep from getting bogged down in the nonessential is part of what makes Bird Box such an engaging read.

In fact, I’m giving this book five stars because it’s so successful in spite of my own personal criticisms. I don’t do that often because, honestly, most authors who use a style I don’t enjoy, such as present-tense narrative, don’t hold my attention beyond the first ten pages. The fact that Malerman was able to hold my interest is testament to his ability as a storyteller and to the success of “Bird Box” as a story about humans in crisis and how they react both to that crisis and one another.

Highly recommended.

Don’t open your eyes.

— Tagline for "Bird Box"

August 6, 2017

Dear pretentious critics: Here's why we don't like you

How do you decide what movies you want to see? Do you read the reviews? If you do, you probably have one of three reactions: You might go to the movie if it gets a good review, you might decide to ignore the review altogether, or you might wind up doing the exact opposite of what the critics recommend.

If you’re in the third group, chances are you’re not acting that way just to be rebellious. You’re doing it because you’ve figured out that the critics’ choices usually don’t jibe with you own.

The same principle holds true for music, literature and any other form of art. Often enough, critics and fans enjoy the same things, but in other cases, their opinions diverge — sometimes sharply.

Critics tend to look down their noses at art they consider derivative or clichéd, saying to themselves, “Hey, I’ve seen this before. Why should I waste my time on seeing it again?”

Just yesterday, I wrote an entry here that touched on the importance (among other things) of originality in writing. I’m not one of those people who’ll see a movie several times or reread a book, no matter how much I enjoyed them. In fact, I’ve never read a novel twice in my life. Been there, done that. Hearing a song too often can turn it from catchy to cloying. Watching a movie repeatedly can put me to sleep.

But, hey, that’s me. There are plenty of people who enjoy hearing the same song over and over, rereading their favorite novels and watching the DVD of their favorite movie time and again. The Wizard of Oz became a yearly tradition on broadcast television in 1959, and the same treatment is given to holiday films such as Miracle on 34th Street and White Christmas during the holidays. So, there’s obviously a big appetite for this.

One thing these movies have in common is they’re accessible: They tell stories in such a way that a lot of people can relate to them.

The problem with many critics is they think accessibility is a bad thing. Bands that put out songs with a lot of hooks are dismissed as banal or simplistic. Meanwhile, their music racks up huge sales and fans flock to their concerts.

When it comes to major awards, they’re seldom, if ever, bestowed upon “genre” movies or novels. Academy Awards for Best Picture aren’t given to science fiction, fantasy, horror or comedy films. It "just isn’t done.” Similarly, you’ll never find Stephen King or J.K. Rowling in the hunt for a Nobel or Pulitzer Prize for literature.

Does this mean their work is unworthy? Millions of readers will tell you otherwise.

This doesn’t seem to matter to the critics. Many of them appear to thrive on the notion that they’re somehow “above” public opinion — and strive to maintain this impression by dismissing certain kinds of storytelling wholesale. The irony of doing so is that they’re judging genres based on stereotype, which is itself a form of cliché.

Clichés and stereotypesWhat many critics have lost sight of is the difference between art that’s derivative and art that’s accessible. I make it a point to write conversationally so my readers can relax and enjoy what I’ve written. I don’t want to make them work too hard. One of the perks of being an adult is that reading gets to be fun, not the kind of textbook chore you had to endure in grade school.

(Sometimes, I think stale textbook authors and self-important critics emerged from the same mysterious protoplasm — that gooey muck that spawned F. Murray Abraham’s character, Professor Crawford, in Finding Forrester.)

Accessible writing isn’t simple-minded. On the contrary, it’s deft. I like to make my readers think. I’ve written books and articles on philosophy, for Pete’s sake. But that doesn’t mean presenting people with such a pretentious, confusing mess that it’s impossible to make heads or tails of it.

Despite what many critics seem to think, art can be accessible and original at the same time. It can be intelligent and fun. A good mystery can make you think and enjoy yourself at the same time. (Not coincidentally, mysteries are another popular genre that’s on the outs when it comes to consideration for major awards.)

Is it any wonder that some people choose to ignore the critics or even use critical disdain as an excuse to check out a book or movie? People don’t like being excluded. When their favorite film or novel is dismissed without a second thought, they don’t like that much, either. The people who do the dismissing will lose their credibility — regardless of their expertise or sense of self-importance.

The word “discriminating” can carry two different definitions: “selective” or “dismissive.” Too often, critics cross the line from the former to the latter, and in doing so render their opinions irrelevant.

That’s my critique. Take it or leave it … but either way, go have fun.