Stephen H. Provost's Blog, page 7

June 16, 2019

Treasure maps don't inspire me — real people do

If you’re successful, please resist the urge to utter these five words: “You can do it, too!”

You may think they’re encouraging, but what if they have the opposite effect? How many J.K. Rowlings or James Pattersons are there? I can do it, too? Really?

Still, I’ve heard this kind of statement often enough from writers who’ve found success. I’m sure other creative people – visual artists, musicians, poets – have heard it, too. But let’s change it up for a moment. How would it sound coming from a Wall Street executive telling someone in the inner city how to succeed in business? Do the words “presumptuous” or “clueless” come to mind?

But for some reason, it’s considered OK – even “inspiring” – to speak to creative people like that. Kind of like the old saying that anyone can grow up to be president of the United States. Well, no, not just anyone can. Only people who receive millions of dollars in donations, are nominated by a major political party and receive a majority of Electoral College votes can do it. Oh, and you’ve got to be a citizen by birth and at least 35 years of age. If you’re a naturalized citizen or wind up dying before you hit 35, you’re out of luck.

I know this sounds cynical, but I’m not writing this from a cynical perspective. I’m trying to illustrate how people who have “made it” often view the world through the lens of their own narrative ... and then try to apply it to everyone else. Yet how they feel about their own success is informed by their hindsight; they might remember how hard it was to be a poor or struggling artist, but they no longer feel things from that perspective (not would they, I suspect, wish to do so).

Some people do this intentionally, to augment their income. They want to make everything seem “easy peasy” so they can sell you how-to books containing a “sure-fire” formula for success. But the only thing sure-fire about these books – even those that contain helpful advice, and some of them do – is that the author is going to be making money off each sale.

Most successful people, however, do it unintentionally. Some may suffer from impostor syndrome and can’t believe they deserve what they’ve achieved. They see themselves as frauds, and if they can fake their way to stardom, they assume others can do the same. Others look at how far they’ve come and sincerely want to encourage others – to share the “secret to their success.”

But the effect can be just the opposite: Instead of instilling hope, it can encourage people to place expectations on themselves that they have no way of ever fulfilling, because every situation is different, and everyone has a unique story to tell.

I’m not youWhenever I hear someone say, “You can do it, too,” the little voice inside me says, “No, I can’t. Not the way you did it.” I want to tell them not to sell themselves short with false humility, because they have a talent I can’t replicate. Nor would I want to, because I’m not them. I can’t do what they’ve done, because what they’ve done is uniquely amazing and should be recognized as such, not downplayed as some sort of happy accident that can be duplicated by me or anyone else.

That being said, there is luck involved in any success, and I’m just as likely to duplicate a successful person’s luck as I am to match their skill.

What most people probably mean when they say, “You can do it, too,” is that they worked their asses off, and they view their success as the payoff for that hard work. Our nation’s Protestant work ethic has drummed it into us: We believe that hard work is the key to success, as though one automatically follows the other. Of course, it doesn’t. Any more than innate talent or even a single stroke of luck does. It’s just not as simple as that.

A successful person’s story can, indeed, be inspiring. I’m not for a moment suggesting that those who have found success “shut the hell up about it.” On the contrary. Those stories are part of what made them who they are, and they should be told – so we can get to know that person and celebrate their successes along with them.

But to suggest that “you can do it, too” is to cheapen those stories, to make them seem more pedestrian than they really are. I can’t live another person’s life or achieve someone else’s success; I can only live and achieve my own. When all is said and done, it will look different than that of another author who made more or less money, sold more or fewer books, became more or less well-known than I did. That’s not only OK, that’s how it should be.

Even if we don’t write books, each of us has a unique story to tell. It’s not a template for someone else’s story, because we aren’t cookie-cutter clones of some ideal. Each of us is unique, and each of our stories is, too. Someone once compared my writing to Stephen King’s, which is certainly flattering, but I’m not the next Stephen King ... and no one will be the next me.

When we stop trying to follow someone else’s treasure map, we stop trying to adopt their expectations as our own. Then, we’re free to appreciate their story as truly theirs, and learn about what makes them uniquely who they are. That’s authenticity, and it’s how we really get to know one another – not as “role models” but as real people.

And it’s real people who inspire me, whether they’re authors working their asses off, people juggling two jobs to make ends meet, stay-at-home parents or scientific geniuses. I’m encouraged by hearing about their unique life journeys, not by listening to two-dimensional success stories that end with false promises that “you can do this, too.”

I already know I can’t. And that’s part of what makes life beautiful.

May 21, 2019

The crucible of open dialogue and the echo chamber of fear

There’s a school of thought that’s gaining currency. It states that people don’t have a right to an opinion about things that don’t directly affect them.

The argument usually goes something like this: “You can’t possibly know what it’s like to deal with this, because you’ve never gone through it, and you never will. You’re not one of us, so you don’t get a say!”

This is dangerous for more reasons than one.

First, it sets up an adversarial mentality between two “sides” before anyone even gets a chance to express their ideas. It perpetuates the “us vs. them” attitude that has become so pervasive in today’s culture.

Second, it makes identity more important than the substance of what might be said. It assumes that a particular group is unqualified to weigh in, not because of what they might say, but because of who they are. If any member of the “out” group dares to speak, he or she had better parrot the party line – thereby adding nothing to the conversation – or risk public censure/alienation.

When identity is codified into law as the basis for inclusion, things get ugly. People aren’t allowed to vote because of their gender or skin color. This is both bigoted and undemocratic.

Third, depriving a segment – any segment – of the population of a voice makes dialogue impossible and casts the status quo in stone. Conforming to a status quo without question makes growth impossible, because it shuts down the marketplace of ideas. Only through dialogue can we bounce ideas off one another and find better solutions than any of us might have arrived at on our own.

Shutting people down makes greater understanding impossible, too. But when any group that shuts out people who “aren’t like us” isn’t interested in understanding other points of view. Members of such a group think they know everything already, and that other perspectives hold no value moving forward.

Free speechFinally, it violates the spirit of free speech.

In the Skokie case, courts ruled that neo-Nazis were allowed to march through a heavily Jewish community that included a number of Holocaust survivors on the grounds that freedom of speech trumped their feelings. They were, essentially, trying to create a “safe space” for themselves. I, personally, disagree with the court on this. I think speech and events designed to provoke an incendiary response add no value to the public discourse.

But the point is, the court thought so highly of free speech it allowed an event most considered repugnant to go forward.

Now, before someone decides to lecture me about the First Amendment applying to governmental limits on free speech, rest assured, I get that. Shutting people down based on their identity doesn’t violate the letter of that amendment, but it sure as hell undermines the spirit of it. That spirit is founded on the notion that we’re all better off when we feel free to share openly – and when we make the effort to listen. Even – and perhaps especially – when what the other person’s saying might challenge our prejudices.

Most places aren’t Skokie, and most people aren’t neo-Nazis. This essay isn’t about such extremists, or anyone whose views are so clearly worthy of disdain. It’s about ordinary, rational people who are being told to STFU because they belong to a specific group – regardless of what they might say. Not a group like the KKK, but much larger groups, many of which aren’t joined electively and hold no abhorrent or even unified views. Not all (fill in the blank) are alike!

Imagine if someone said sports fans had no right to an opinion on free agency because it only directly affects players and owners. Or if people without children were told they had no right to speak their mind about the condition of our schools. Many people are affected by actions indirectly, and many of those people have ideas about those actions. Do they have as much insight as those with direct experience? Perhaps not. But those outside a situation can bring valuable perspectives that, in some cases, offer ideas based on a more detached view. Pre-emptively dismissing such ideas because of their source rather than their merits is short-sighted and foolish.

The crucibleConclusions and prejudices may turn out to be well founded, but they still need to be challenged. And those challenges need to come from people with different perspectives. Otherwise, how will we know for sure whether they’re valid? We might still believe in a flat Earth, a geocentric model of astronomy, that dinosaurs lived alongside humans and that masturbation leads to blindness. Forming a hypothesis and conducting an experiment are crucial to the scientific method. But how can you form a reasoned hypothesis if you’ve never considered alternatives? And why bother to experiment if you already (think you) know the answer?

When you shut out people you worry might have opposing views based on nothing more than the messenger’s identity and the fear of being offended, you set the table for the kind of insular thinking that spawned Jonestown. An extreme example? Sure. But the principle is the same. And if the principle operates unchallenged for long enough, that’s the kind of thing that ends up happening. The frog will boil.

So, the next time you tell someone they don’t have the right to an opinion because they’re not like you, ask yourself whom you’re hurting. They won’t be the only losers, because it’s not a zero-sum game. Your conclusions might be right. Them might be wrong. Or, just maybe, greater truth and understanding might arise from the crucible of open dialogue.

Without such a crucible, nothing new and beautiful will ever be fashioned. Increasingly, out of fear, we’ve chosen to replace this crucible with an echo chamber.

There are no “safe spaces” when it comes right down to it. The world is a brutal and dangerous place, which is precisely why we need to stop alienating one another. We may not achieve safety, but we can find hope for a better world – not by ostracizing and dismissing others before they even open their mouths; only by engaging.

Like it or not, we’re all in this together.

April 20, 2019

Book reminded me why I admire the "Father of Christian Rock"

I met Larry Norman once, backstage after a concert at a church called Bethel Temple in Fresno, California. It was sometime around 1980, and the encounter was brief, but it stuck in my memory.

Others were gathered around, wanting to greet him, and when my turn came, I asked him a question I’ve long since forgotten. What I do remember was his response – not to the question, but to me personally. He stepped forward, and I must have either taken a step or leaned back. He said something to the effect of, “You value your personal space.”

I was maybe 17 years old at the time, and I’d never even thought about that concept before, but I immediately knew he was right. What I later learned about Larry – and seems apparent, as I look back on it – was that he took pride in being “invasive.” In challenging the status quo. It was one of the things I liked so much about his music.

It’s not an exaggeration to put Larry Norman up there with Dylan, Paul Simon and Lennon as a songwriter. In fact, I consider him the most gifted of the lot. The Great American Novel may be the most literate protest song ever written, all the more so because it straddled two worlds, critiquing secular society and Christian culture with equal candor. That’s something Larry did throughout his career.

Reintroduced in printAfter that single meeting, I never got another chance to talk to Larry or to know him beyond what he revealed in his lyrics. He died of heart failure in 2008 at the age of 60. But recently, I got the chance to know him better via Gregory Alan Thornbury’s superb biography, Why Should the Devil Have All the Good Music?: Larry Norman and the Perils of Christian Rock (Convergent Books, 2018).

Thornbury’s evenhanded approach to Larry’s life stands in contrast with a documentary called Fallen Angel: The Outlaw Larry Norman, released the same year as the musician’s death. One writer described the video as a piece of “postmortem character assassination,” which doesn’t seem far wrong, considering it contains a number of vicious rumors that range from unsubstantiated to provably false. I won’t repeat those here. The video included interviews with an assortment people who had axes to grind against Larry and took the opportunity to do so; after all, the target of their criticisms was no longer around to answer them.

Thornbury, by contrast, didn’t rely on recollections that might have been colored by the passage of time and the deepening of grudges. Instead, he was granted access to Larry’s personal archives – a collection of letters, notes, recordings, news clips, etc. – which contain accounts of events as they happened. The result is a sober picture of a man who was at once blunt and enigmatic, who fought a war for awareness on two fronts, challenging both secular seekers and the Christian establishment to look at themselves in a new light.

Two-front wars are hard to win, as reflected in songs such as Shot Down, his response to “rumors and gossip” from the church establishment that he was “sinful,” “backslidden” and had “left to follow fame.” “They say they don’t understand me, but I’m not surprised, because you can’t see nothin’ when you close your eyes.”

But the secular establishment was no more friendly. They didn’t want to hear songs about Jesus unless they were one-off fluff pieces like Jesus is Just Alright. Larry didn’t write fluff pieces.

An intentional enigmaOn some level, Larry made himself hard to understand on purpose. But was that such a bad thing? It forced people to think for themselves rather than just accepting someone else’s easy answers. Jesus had done the same: In Larry’s words, “he spoke in many parables that few could understand, yet people sat for hours just to listen to this man.” Larry’s provocative lyrics and concert monologues had much the same effect.

That’s one big reason I related to him – and still do. In my own writing, I strive for originality. Repeating “the same old story” holds no appeal. If all I’m doing is reinforcing others’ biases, that’s neither loving nor illuminating. “I am only a ringing gong or a clanging cymbal.” I don’t know whether Larry ever quoted that verse from 1 Corinthians in this context, but he might as well have. He refused to write songs filled with popular Christian catch phrases, and Thornbury relates that he once said, “I believe that clichés are a sin. Maybe not to God, but to the muse of art.”

Larry wrote in one of the letters Thornbury quotes: “Music is powerful language, but most Christian music is not art. It is merely propaganda. It never relies on – in fact it seems to be ignorant of – allegory, symbolism, metaphor, inner-rhyme, play-on-word, surrealism, and many of the other poetry born elements of music that have made it the highly celebrated art form it has become. Propaganda and pamphleteering is (sic) boring and even offensive you already subscribe to the message being pushed ... which is why Christian records only sell to Christians.”

The second album in Larry’s trilogy of albums was pure allegory, focusing on man’s past in the Garden of Eden. It didn’t mention Jesus by name at all, so the Christian audience assumed he’d “gone secular,” finding further “proof” in the album cover, which featured a naked Larry playing the part of Adam. Never mind that he was only shown in a silhouette that was overlain by the image of a lion: You couldn’t even see his skin. What mattered was the self-righteous Christian establishment didn’t want allegory; it didn’t want to think. It wanted its spirituality spoon-fed in black and white, which was something Larry refused to do.

Outsider looking inLarry lived his life as a perpetual outsider who once said, “I don’t feel like belonging to anything or anyone.” The cover of his most acclaimed album shows him scratching his head in bewilderment, and its title proclaimed he was Only Visiting This Planet. Lost behind the obvious Christian message was the sense that he must have felt that way on a personal level, too. Indeed, he once said he felt “like an orphan with a small, isolated voice crying out in a cultural wilderness.”

The cover to Gregory Alan Thornbury’s book.

Perhaps Larry’s childhood helps explain why he apparently felt so out of place. Thornbury writes that Larry grew up in a Christian household, but that he found church boring and street preachers joyless. His conversion at age 5 was personal, “without benefit of clergy.” It wasn’t to please his father, with whom he had a strained relationship, but to fill a void left by the man’s absence during a childhood where bullies outnumbered friends. Jesus became his best friend, and he “didn’t feel so alone after that.”

From then on, Larry knew Jesus was the answer, but he still felt he had to ask the questions, and this is what set him at odds with a church establishment that wanted people to accept its proclamations on faith. But Larry’s faith was in Jesus, not doctrines. Never was this more apparent than in the early ’80s, when his Phydeaux record label issued a T-shirt with the slogan “Curb Your Dogma!” (With Phydeaux being a faux-French spelling of Fido, the dog’s name. More wordplay.)

Larry even questioned “sacred cows” like the church’s knee-jerk condemnation of homosexuality. “Is homosexuality a real issue?” he asked. “Well, (in the church) you can’t talk about it on the grounds that the gay (community) wants to discuss it. They say, ‘We were born this way.’ But we ‘know’ that it’s not natural, that they’re not born that way. But do we know that? Have you thought about it?”

The implicit answer was no, they hadn’t. Congregations were merely parroting the judgments they had been thought, rather than thinking for themselves.

Larry didn’t fit in with either the secular questioners who didn’t like his answer or the religious establishment, which didn’t like his questions.

A time of hopeFor a while, though, his approach appeared to be working. In the heady aftermath of the 1960s, there was a degree of synchronicity between American culture and the type of Christianity that Larry was espousing. He shared the egalitarian goals of the civil rights and anti-war movements, and listeners were at least open to songs about spirituality by mainstream artists such as George Harrison (My Sweet Lord), Blind Faith (Presence of the Lord), Norman Greenbaum (Spirit in the Sky) and Ocean (Put Your Hand in the Hand). The Andrew Lloyd Webber-Tim Rice musical Jesus Christ Superstar made Jesus “cool” and helped open the door to a certain degree of cultural commonality between Christians and non-Christians.

Grassroots movements such as The Vineyard, which started as a Norman-led Bible study, helped make Christianity more accessible to those who didn’t care for the formality or hierarchy of a traditional church. This wasn’t really anything new: The concept of the priesthood of all believers (translated in modern language as “a personal relationship with Jesus”) dated back to Martin Luther’s insurgent campaign against the Catholic Church. The 1970s were the same thing happening all over again.

The upstarts weren’t entirely innocent. There was even some ugly, even vicious anti-Catholic propaganda created by, among others, Keith Green, an incredibly gifted but often very judgmental musician whom Larry had steered toward Christianity. There was plenty of animosity to go around. And just as the Catholic Church had struck back against Protestantism in the Middle Ages, the mainstream church struck back against Larry Norman and others like him, branding them wolves in sheep’s clothing who were willing to “compromise with the world.”

Scapegoat and changeIt didn’t help that egalitarians like Larry had no idea how to take their movement to the next level. They started out as critics of structure and organization, but when they tried to adapt this model to business, it created a series of misunderstandings and bad feelings. As a result, Larry’s vision of a record label built on a community of artists came quickly crashing down.

When one band signed to Larry’s label wanted to jump ship for a secular record deal, Larry was, by Thornbury’s account, willing to eat his own investment. But he said the band would have to keep its agreement to release an already-recorded album because he’d made a commitment to his label’s distributor. This wasn’t good enough for the band, which led Larry to dig in his heels on other points, as well, and although he wound up with nearly everything he fought for, he was subsequently blamed for much of the acrimony that ensued. This happened in part because of a failed business model and in part because the establishment was just itching to blame Larry for everything that went wrong.

Case in point: Thornbury relates that Larry fought to save his first marriage despite his wife’s drug use, visits to the Playboy mansion, multiple alleged affairs and admission that she had cashed thousands of dollars in checks made out to him. Larry was never accused of being unfaithful himself, but when he slept with a woman as a single man after his second marriage collapsed, he was castigated for it. Years later, the woman claimed he had fathered her child. That claim was never definitively proven (or disproven), but just the possibility it might be true confirmed everything the established church wanted to believe about the old thorn in its side – and provided the ammunition it craved to discredit him.

This all happened even as it embraced such “leaders” as Jim Bakker and Tony Alamo, both later convicted of major crimes, and Jimmy Swaggart, who was forced to admit his own infidelity. But however egregious their actions might have been, none of these people committed the ultimate transgression against the Christian establishment: asking too many questions. This was Larry’s cardinal sin, and even though he arrived at the same answer as they did (Jesus), they cared far more about how he got there. And because it was different than the way they’d gotten there, they condemned it.

At the end of the 1970s, Larry Norman appeared at the White House to play for one of his fans. President Jimmy Carter was a socially conscious Christian who shared many of Larry’s views. But when the ’70s ended, a different kind of Christianity rose up on the wings of Jerry Falwell’s Moral Majority. This more judgmental, less inclusive movement ushered in a new establishment that slammed the door shut on egalitarian brand of Christianity that Larry espoused.

No room at the innThere was no room for questioners like Larry Norman in the new world of black-and-white Christianity, and he never again attained the level of popularity or acceptance he had achieved during the 1970s. In the end, he died young and relatively unknown to many, despite being recognized as the “Father of Christian Rock” and the man behind the most critically acclaimed Christian album of all time.

Larry may have engaged in a degree of self-pity at times, but that’s a natural human response to the kind of attacks he faced. Given his immense talent, he could have probably made a fortune as a musician catering to either secular or Christian tastes. But he refused to cater to anyone, and that brought both scorn and frustration from both sides of the fence.

As an artist myself, I can relate. I’ve always insisted on asking the hard questions, refusing to settle for clichés in place of real answers. When it became clear the church didn’t want to listen, I stopped going. Unlike Larry, I didn’t start out with the ultimate answer. When I became a Christian, it was a trial run rather than a leap of faith. I recall saying to myself, “I’ll give this thing a chance. If it works, great. If not, at least I’ll know why.” Ultimately, it didn’t work for me, and what drove me away is the same narrow-minded intransigence Larry encountered all of his life.

The same evidence led us to different conclusions. Larry chose to continued the battle, while I stepped away from the war zone. I couldn’t understand why people who followed a prince of peace felt the need to remain continually at war with those they said they loved – even those who shared their core beliefs. I still can’t. And in the years since I left the church, those wars have only intensified. The conformist Christianity that marginalized Larry’s message during the 1980s has, if anything, gained a firmer foothold. The same people who excused men of dubious character like Jim Bakker and Jimmy Swaggart now place their hope in a similarly corrupt president, sacrificing their principles for the sake of a worldly kingdom no god would ever claim.

Larry Norman, prophetLarry’s lyrics from The Great American Novel turned out to be prophetic": “The politicians all make speeches, while the newsmen all take notes. And they exaggerate the issues as they shove them down our throats.” Such are the times we live in, and we need voices like Larry’s today more than ever – voices that challenge us to be a better version of ourselves. Articulating that challenge was Larry’s greatest gift, and it’s why I still listen to his music today, long after I stopped going to church.

Consider this lyric from the same song: “You kill a black man at midnight just for talking with your daughter. Then you make his wife your mistress and you leave her without water. And the sheet you wear upon your face is the sheet your children sleep on. And with every meal, you say a prayer you don’t believe, but still you keep on.”

Few others had the insight, integrity and guts to write lyrics like that, even at the height of the protest era. I can only imagine how many evangelicals would react to them today, in an era when most congregants admire a president who also enjoys the ardent support of the KKK.

My affinity with Larry stems in part from the fact that I, too, feel like I’m fighting a war on two fronts, with two things at stake: my personal integrity and my artistic vision. I have no desire to be either a religious robot or an embittered existentialist. Like Larry, I feel like a voice in the wilderness fighting an uphill battle. I refuse to conform for the sake of conformity or stop asking questions for the sake of “peace” – not when that peace is really a thinly veiled form of oppression.

I like to think, in some ways, that I’m following in Larry’s footsteps. Whether that’s the case or not, there’s no arguing that he inspired me.

I’m sorry I didn’t get another chance to talk to Larry Norman after that night in 1980, but I’m grateful to Gregory Thornbury for letting him speak to me again.

A prophet has no honor in his own country.

— John 4:44

The church doesn’t think I’m a Christian.

— Larry Norman

April 9, 2019

Writing the biography of a legend: Molly Bolin

Some people read romance novels for pleasure. Others read science fiction. In my youth, I was smitten by the Tolkien bug and went on a binge of epic fantasy, but these days, I have a different guilty pleasure: I read rock star biographies. Sammy Hagar. Freddie Mercury. Zeppelin. All four members of KISS.

For a while, I’ve wanted to write a biography of my own. Not a memoir, and certainly not an autobiography. I’m not in the business of putting people to sleep.

My friend Anne R. Allen, an author one of the premier bloggers on the business of writing, makes some good points in a recent piece on memoirs. The three that stood out to me were:

Tell a page-turning story.

Focus on significant and unique personal experience, especially when tied to a well-known person or event (emphasis mine).

Remember that a memoir, like a novel, is read for entertainment.

The first and the third points are closely related, and all three together are the criteria I use when deciding to read a biography. Plain and simple: I want to find out more than I already know ... about someone I already know about. And I want that “more” to be entertaining.

But as an author, I want my stories to be original. I don’t have much interest in writing yet another biography about Freddie Mercury, no matter how big a fan I may be (and I am). That story’s been told, and no one needs me to tell it yet again. One of my main objectives as an author has always been originality. I wanted to write the definitive history of Fresno in the Baby Boom years in 2015 and of U.S. Highway 99 in 2017, because no one else had done it.

As you might imagine, this quest for originality becomes more challenging in the realm of biography. If you write about a regular, average person, who wants to read that – unless the story is knock-your-socks-off incredible. But most well-known public figures have already been featured in biographies written by better-known authors than I. So, my desire to write a biography has always been unfulfilled as I waited for the “perfect” subject I suspected would never come along.

Then, she did. The result is The Legend of Molly Bolin.

Out of the blueThe irony is that this book came about because of another project that was more a labor of love than anything else. I didn’t write A Whole Different League (AWDL) to be a big seller; I wrote it because I had grown up as a sports fan and had always been fascinated about leagues that didn’t quite make it. I’d spent a decade working as a sportswriter at daily newspapers, yet I’d never written a sports book. I figured it was time to do so.

Writing AWDL, like reading rock star biographies, was something of a guilty pleasure for me – so much so that I wrote it in fits and starts over the course of two years, putting it down to write something I thought would be more marketable before picking it up again between projects. I had the first draft all but done when I remembered the Women’s Basketball League from the late 1970s, which had lasted three years and featured the likes of Ann Meyers, Carol Blazejowski, Nancy Lieberman ... and Molly Bolin.

The odd thing was, I’d never heard of Molly. But what made that even stranger is that she had scored more points than any of them. More points in a season. More points in a game. More points in a playoff game. More points in a half. More points in a career. The fact that the premier scorer in the first women’s pro basketball league had somehow flown under my radar piqued my interest, so I started doing some more research. I found out that she had remarried and was now Molly Kazmer, so I took a flyer and looked her up on social media.

Lo and behold, she answered my request and wound up providing me with some great firsthand information about the WBL for that final chapter. But the more she told me, the more I became convinced that her story alone would make a fascinating book. Had anyone else written one on her? Had she ever considered writing one herself?

By fortuitous happenstance, the answers were “no” and “yes,” respectively. In fact, she had been accumulating a wealth of photos, newspaper clips and other memorabilia to someday document her life and career. I suggested to her that “someday” might be now: Would she consider working with me to tell her story?

Again, the answer was “yes,” and for the next 10 weeks or so, we communicated almost daily as I wove together her life’s story from a combination of her many recollections, media resources and interviews with contemporaries – many of whom had amazing stories of their own to tell. There was Tanya Crevier, the 5-foot-3 ballhandling wizard who played three years of pro ball with Molly and still performs an amazing and inspirational show worthy of the Harlem Globetrotters for people around the world. Then there was Greg Williams, the only person to coach women’s championship teams in three different pro leagues, on top of an impressive Division I college resume. He not only was kind enough to sit for an extensive phone interview, but he agreed to write the foreword.

I couldn’t believe my good fortune.

An amazing storyEven with all that, though, Molly was the star of the show. Not only was she the top scorer in the first women’s pro league, she was the first player to ever sign. She went from a benchwarmer during the first half of her rookie season – to the team’s offensive star, even though she was young enough to have been a junior in college.

She adapted her game from Iowa’s old 6-on-6 rules (three offensive players always in the frontcourt; three defenders confined to the other half of the hardwood). But not only that, she turned it to her advantage by using a quick stop-and-shoot style that presaged the modern jump shot practiced by the likes of Stephen Curry – to whom she’s been compared. Or, perhaps, he’s been compared to her.

She even won a precedent-setting court case and helped pave the way for today’s merchandising boom by pro athletes such as Michael Jordan and LeBron James, when she came up with a marketing strategy that made her basketball’s answer to Farrah Fawcett. Stars like Magic Johnson, Larry Bird, Pete Maravich, Martina Navratilova and Rick Barry play a part in the narrative, too.

I won’t give anything more away (you’ve got to buy the book!), but I will say this: The Legend of Molly Bolin is everything a great biography should be – and not because I wrote it. It was simply a great story waiting to be told, and I had honor of being the one to tell it.

The story isn’t just about Molly. It’s about all the players, coaches and executives who made history by taking part in the WBL and other early women’s leagues. People like Althea Gwyn, Doris Draving, Cardte Hicks, Connie Kunzmann, Robin Tucker, Rita Easterling, Janie Fincher and Tanya Crevier. The league was inducted as a whole into the Women’s Basketball Hall of Fame last year as Trailblazers of the Game, and deservedly so.

But there are at least a few members of the old WBL who deserve to be inducted individually, as players like Meyers, Blazejowski, Lusia Harris and Lieberman have been. After all, if a Stevie Nicks can join the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame as a member of Fleetwood Mac and a solo artist, it only makes sense to bestow the same kind of honor on a Molly Bolin.

Like one of her jump shots, it ought to be a sure thing.

February 15, 2019

A guide to Facebook friendships for authors: 15 dos and don'ts

I don’t attend church these days, but when I did, I noted a constant tension between “outreach” and what the numbers game, and I realized that all too often, the line between them was blurred. Motives were mixed, and sometimes it seemed like a church was advocating outreach to the poor and needy as a means of putting more rear ends in the pews (and, by extension, more money in the offering dish).

If this seems cynical, it isn’t meant to be. I’m just pointing out that pure and not-so-pure motives can work toward the same ends. But when the latter dominate, they tend to undermine the former – or overwhelm them entirely.

You can exhale now. This isn’t a blog about religion. It could just as easily be about elected officials and the tension between public service and political donations. Or corporations, and customer service vs. the bottom line.

It isn’t about those things, but it’s about the same sort of underlying tension, which is becoming more and more common in the world of publishing, often among independent and self-published authors.

Writing is a tough business: Not many are able to make a living at it, and it’s difficult to get noticed, even if you’ve got an agent or publishing house in your corner. Whenever something’s this hard, it’s natural to look for shortcuts. It’s easy to buy “how to” books and enroll in dubious workshops written by people who promise success. But most such people are merely hoping to line their own pockets by capitalizing on your desperation to somehow make things happen.

One of the things these books and workshops often emphasize is networking. Many of us, as authors, aren’t good at this. We aren’t social creatures by nature, preferring to wrap ourselves up in our next story rather than venturing out into the world at large. We’re not experts at self-promotion, by and large, and most of us tend to shy (or run) away from it ... which makes us even more prone to trying shortcuts. When it comes to networking, we don’t like to schmooze or make sales pitches, we stick our toe hesitantly in the water, pull it back out at the first sign of a chill – and, in the process, do more damage to our public image than we would if we’d jumped right in.

Instead of doing the work, we rely on shortcuts, which seem less painful in the short term but seldom accomplish anything in the long run.

One such shortcut is the Facebook friend request, which has become the online equivalent of handing out your business cards to strangers on a street corner. (Show of hands: How many of you keep a business cards someone thrusts into you hand on the sidewalk?) I’ve been getting an increasing number of friend requests from other authors online, which in itself is fine, but that seems to be as far as it goes. Few of these authors bother to follow up by posting on my profile, and some don’t share much of anything on their profile except pitches for their releases.

Repeat after me: That’s not how networking works.

Real networkingNetworking requires engaging with people, and getting to know them as human beings rather than sales marks who “maybe, just maybe, will buy my book” (or review it or share my posts with others). Such friend requests have less in common with actual friendship than they do with childish games like ring-and-run, or with superficial but sometimes guilt-inducing chain messages/emails. Still, this tactic has become so pervasive that I’m more hesitant to accept friend requests from other authors than anyone else except Nigerian princes or porn bots.

Some authors are encouraged to pursue this course because many people will accept their requests simply based on the fact that they’re “fellow authors” and that they have a fair number of friends in common. Then, instead of introducing themselves, they often immediately send you invitations to “like” their Facebook business pages, hoping that this in itself will somehow magically produce more sales. Hint: It won’t.

To return to our church analogy, it’s like passing the offering plate while parishioners are still finding their seats – before the first hymn or chorus is even sung. Or like demanding supporters make cash donations before a politician is even elected ... wait, they do that anyway, but you know how highly people think of politicians, right? ’Nuff said.

Good networking requires a lot more than this, and being a socially awkward author who feels out of his/her element when it comes to marketing will not change this fact, no matter how badly we might wish it.

But the beauty of Facebook is that authors can actually do networking – real networking – without ever leaving their comfort zone. If you’re on Facebook, you don’t have to meet anyone face-to-face (although occasional personal appearances are still a good idea). You can make meaningful contacts without ever leaving the comfort of your home office. If, like me, you’re a lot better at one-on-one interactions than mass marketing, do that! Take Facebook’s friend requests literally and make friends.

This requires, first of all, that you avoid the temptation to send off friend requests willy-nilly to any author who happens to share 50 mutual friends or more. Check to see if you have other interests, a hometown, a favorite band or something else in common – more than just writing in the same genre – before you approach someone. Facebook has tools to help you find these areas of common interest, so make use of them. Then, if someone accepts your request, interact directly. Respond to something on their profile. Engage. And not necessarily about books. About art, philosophy, history, music.

If they buy or review your books, that’s gravy. If not, you’ve done something more valuable: You’ve made a friend. And friends are more likely to read your work because they want to, not out of some sense of duty to a fellow writer.

Dos and don’tsHere, in a nutshell, is my advice for dealing with other authors, and friends in general, on Facebook.

DO send friend requests to people with whom you have something in common in addition to writing.

DO engage with new friends on a personal level. Start conversations that have nothing to do with books and even less to do with selling them: Make pitches the rare exception, rather than the rule.

DO talk about writing as a craft; give your friends insight into how you work and let them share your excitement at your progress ... but because they’re your friends, not because they’re “marks” for a potential sale.

DO stay positive and encourage others to write, regardless of whether they’ve read a single word you’ve written or are ever likely to.

DO have a sense of humor, including about yourself. Post funny stuff.

DO share a variety of types of posts on your profile, from memes and polls to personal insights and photos to music videos and news stories.

DO respond to posts on other people’s profiles, not just your own.

DO let people know what you believe in; talk occasionally about your principles and how they’ve helped shape your life and work, but ...

DON’T spend too much time on partisan politics unless you want to spend a lot of energy fighting off trolls and risk alienating friends who are sick of hearing about it.

DON’T send out friend requests like mass mailers, hoping to put another notch in your gun.

DON’T immediately ask a new friend to “like” your Facebook business page. (Hint: You’ll attract a lot more page followers by actually posting interesting stuff there – imagine that!)

DON’T treat your Facebook profile as nothing more than a sales showroom for your books.

DON’T engage in author wars; no one wins when you presume start telling other authors how to write, and most people outside the author community don’t care.

DON’T spend a lot of space complaining about the industry. We all need to vent sometimes, and friends will understand that, but if you’re too negative too often, people will tune you out.

And, above all, DON’T get so distracted by all this that you stop writing. That is what makes you a writer, after all.

February 4, 2019

New book recalls outlaw leagues, forgotten teams

I’ve always been a sports fan. Well, maybe not always, but at least since I started watching football as a preteen. My father followed all the L.A. teams, so I did, too. I collected baseball cards, followed the box scores in the newspaper and parked myself on the sofa every Saturday and Sunday to watch six hours of football – shouting at the TV every time the ref made a lousy call.

My parents and I attended half a dozen Dodgers games each year, and my dad took me to see a Lakers game and a Rams game. We lived next door to the Dodgers’ left fielder at the time, Bill Buckner, and he got me a ticket to see a game in the 1974 National League Championship Series against the Pittsburgh Pirates, and a World Series game against Oakland that same year.

But I wasn’t just a fan of the major sports. Dad took me to an L.A. Aztecs soccer game at the Rose Bowl, where the 9,000 fans looked lost in a sea of 100,000 seats. I also saw Steve Young play a game for the L.A. Express. I loved the ABA’s 3-point shot and the USFL’s two-point conversion, and I followed the Southern California Sun in the old WFL. I even remember watching Dick Lane announce “World Champion L.A. T-Bird” roller games on syndicated TV. They were more spectacle than sport, but I didn’t know it at the time.

Memories from my childhood tend to find their way into books, as they did with Fresno Growing Up and Highway 99. So it is also with A Whole Different League, my latest release, an extensive look at outlaw leagues, forgotten teams and the players who made them great – or at least interesting – of only for a brief moment in time.

The work covers more than two dozen big (and wannabe big) leagues, most of which receive an entire chapter’s worth of information. Their founders were innovators who broke down racial barriers and ushered in the era of free agency. They gave us the three-point shot, which changed the way basketball is played today. With names like the WHA, AAFC and All-American Girls Pro Baseball League, they fielded teams with names like the Chicago Whales and Philadelphia Bell. They were upstarts and outcasts, playing in rundown arenas and without TV contracts but making the kind of memories you don’t find in prime time.

Writing the bookI started this project a couple of years ago, picked it up again, then put it down before finally finishing it this year. It was one of those ideas that just kept its hooks in me and wouldn’t let go, and I’m glad it didn’t. It’s the first book I’ve published on my own imprint (Dragon Crown Books) that includes photos and statistical tables, and it’s also the first in a larger format: 8 by 10 instead of the standard 6 by 9.

It was an involved process, to say the least. The research involved sifting through more than 400 newspaper articles, magazine pieces, websites and books on everything from the National Bowling League to the Negro Leagues, from the All-America Football Conference to the All-American Girls Baseball League. Even Roller Derby. I thought I’d almost reached the end of it when I remembered the Women’s Basketball League that ran for three seasons starting in the late 1970s.

I got in touch with Molly Bolin (now Kazmer), the league’s all-time leading scorer, who in turn put me in touch with Cardte Hicks, the first woman to dunk in competition. Both were kind enough to share their memories of the WBL, whose members were inducted into the Women’s Basketball Hall of Fame last summer as “trailblazers of the game.” If you’ve never heard of either of these great athletes, that’s part of the reason I wrote this book.

Writing historical nonfiction is not only a trip down memory lane for me, it’s also a journey of new discovery. This book was no exception. If you enjoyed accompanying me on my scavenger hunt of old U.S. Highway 99, chances are you’ll enjoy this work, too. And there’s more where that came from: Forthcoming books will focus on U.S. Highway 101 and the history of American department stores/shopping malls.

InsideA Whole Different League contains stories of:

The high-scoring basketball star who was so volatile an opposing team once hired five boxers to stand guard at courtside – and who disappeared, never to be heard from again, on a trip to Africa.

The Hall of Famer who came out of retirement at age 45 to play alongside his two sons, leading his new team to a championship and winning the MVP Award.

George Steinbrenner’s first big signing: the two-time college basketball player of the year.

The NBA legend whose poor eyesight led to him to design the ABA’s red-white-and-blue basketball.

Miami’s first pro football team, which was almost as bad as the 1972 Dolphins were good.

The man who built Wrigley Field and the team that played there before the Cubs called it home.

The first pro baseball game played under the lights at Wrigley – more than 40 years before the Cubs played their first night game there.

The hard-partying skater who signed the richest contract in pro sports but wound up sleeping on a park bench after he lost it all.

The team owner who warned Donald Trump he'd have "no regrets whatsoever" punching him “right in the mouth.”

The batting champion who hit like Ty Cobb but was banned from baseball. (No, it’s not Shoeless Joe Jackson.)

The team that was supposed to bring NFL football to Los Angeles nine years before the Rams moved west from Cleveland.Jackie Robinson’s professional debut – in football.

The man who set a record for the most points scored in a pro basketball game, even though he averaged fewer than 12 points a game that season.

The man who coached pro teams to championships in three different leagues.

And that’s just the beginning. At 334 pages, it’s the second-longest book I’ve written (behind the two-volume work, The Phoenix Principle). A Whole Different League is available now on Amazon. I had a great time writing it, and I hope you’ll have just as much fun reading it.

December 27, 2018

Movie review: "Bird Box" is what horror should be — and usually isn't

There’s a Geico commercial playing in theaters these days that trots out several badly overused horror movie clichés. A bunch of teenagers are seen hiding from a creepy guy behind a row of chainsaws (!) rather than escaping in a running car, answering their cellphone and, finally, inexplicably, running toward a cemetery.

“If you’re in a horror movie, you make poor decisions. It’s what you do,” the announcer says.

It’s funny because it’s true: A lot of horror movies are bad. Really bad. That’s why I don’t bother with most of them. If I want to laugh at a horror movie, I want it to be intentional (think Young Frankenstein). I don’t want to go in expecting suspense, and instead have to suspend disbelief to avoid laughing out loud.

This brings me to Bird Box, the newly released Netflix film starring Sandra Bullock, Trevante Rhodes and John Malkovich. I’ve written about the book here before, and I enjoyed it, so I went in hoping the movie wouldn’t entirely screw up a great novel (as movies are wont to do: Think Logan’s Run).

Thankfully, it doesn’t.

One reason it succeeds is that it doesn’t have people make inexplicably poor decisions simply to put them in harm’s way. They do make bad choices, but those choices are rational and — more importantly — driven by human compassion. The characters must decide whom to trust based on little or no information: Do they leave a stranger “out there” to die at the hands of a mysterious, ravening predator, or do they expose themselves to potential harm by letting that person through the front door? The tension between compassion and self-preservation plays a key role in the movie, as it does in the book. Contrast this with your typical low-budget horror film, wherein a bad screenwriter conjures up some false motivation that no one in real life would ever share in order to justify the terror. (Or simply forgoes motivation entirely and makes the “heroes” a bunch of idiots.)

Bird Box, the movie, wisely adheres to the same formula that made Josh Malerman’s book a success: focusing on the human response to horror, rather than the horror itself. This, I think, is at the heart of the formula for successful horror. Often, the more graphic the horror is, the more two-dimensional the characters become. They wind up being little more than props to be bludgeoned and butchered in the next big gore scene; mannequins at the mercy of Freddie or Jason (who are the real “stars” of the show). To be blunt, I don’t care whether those mannequins live or die, so why should I care about the movie?

I’ve seen a handful of horror films in the past year, and this has been the dividing line between good and bad in each of them. The Nun was awful, filled with jump scares and clichés that left me yawning and rolling my eyes. (Just because The Exorcist worked, that doesn’t mean filmmakers need to keep recycling the “Catholics vs. the Antichrist” theme from now until the Second Coming). The Halloween update was another by-the-numbers retread, rendered passable only by the presence of Jamie Lee Curtis.

On the positive side was Stephen King’s It, which succeeded for the same reason Stranger Things works as a series: It reintroduced us to a childhood we all remember through vivid characters placed in harm’s way. The “evil clown” trope wouldn’t have worked otherwise (it helps a little that it’s not a real clown). If you doubt me, check out Terrifier, another “evil clown” film that I turned off halfway through because I just wanted to go to sleep.

Also effective was A Quiet Place, which was, in some ways, similar to Bird Box. In both, society is threatened by a mysterious predatory evil that limits humans’ ability to interact normally with one another and their surroundings. In A Quiet Place, the characters must remain silent because the predators hunt by sound; in Bird Box, they can’t look at their enemy without being driven mad to the point of suicide. Both films feature strong characters, and I highly recommend seeing both, although I think the story behind Bird Box is more original. The idea that our greatest enemies are unseen, and that those enemies can drive us to the brink of insanity and beyond, is powerful stuff.

The movie did deviate from the book in a few respects. The birds play a bigger role in the film than they do in the novel, and there’s a romance between two characters that doesn’t exist in print. (I give props to Malerman’s original version, in this respect, for its subtlety and the recognition that a deep bond can form between characters without having them jump in the sack.)

The movie also gives the evil force a power I don’t remember from the book: the ability to play tricks on the mind by mimicking voices of its previous victims. While this does add some heightened suspense at the end of the movie, there’s little or no indication prior to that of any such ability on the part of the unseen enemy. Some foreshadowing would have helped.

As with Curtis’ presence in the new Halloween, Bullock and Malkovich bring considerable acting chops to Bird Box, but unlike Curtis in Halloween, they don’t have to carry the movie. The story does that, as it should.

Capsule review:Bird Box is what a horror movie should be — but hardly ever is: tension, suspense, human frailty and courage in the face of terror. Malerman’s book was still better, but it inspired a film that’s several cuts above for a genre that too often relies on cheap jump scares and tired tropes. Malerman understood that humanity is at the core of a good thriller, and the filmmakers wisely followed his lead. It’s an original story deftly told and a strong cast make this well worth seeing.

October 16, 2018

"Motel California" by Heather M. David (review)

I don’t often write book reviews in this space, in part because I don’t read many books cover-to-cover these days. Motel California was an exception. I’ll admit it’s a “coffee-table book,” so it didn’t take me long to cover its 184 pages, but it’s worth taking your time for the quality of the artwork, the presentation and the nuggets of information you’ll find there.

Heather M. David has created a beautifully illustrated, record of the motel in California that’s a worthy addition to the library of any highway history buff or fan of 20th century Americana. Motel California chronicles the heyday of the motor lodge in the Golden State, offering a glimpse at the kind of man-made scenery that transformed highways into something like an amusement park ride all their own, even if you didn’t stop for the night.

David approaches the motels from an architectural standpoint, briefly spotlighting the architects themselves before embarking on a series of chapters dedicated to various motel themes and styles: Storyland, The Western Frontier, Desert Oasis, Tropical Paradise, Cosmic Voyage, Seaside Escape and Mountain High. (David points out that these distinct themes allowed motels to distinguish themselves from one another and stand out from the pack.)

Other chapters focus on the restaurants/coffee shops adjacent to many of the motels; rooms; pools; and, of course, the neon and plastic signs that lit up the night, beckoning travelers to their destination.

David does a good job covering most of the state, dedicating significant space to the Orange County/Disneyland area, as well as Lake Tahoe. I was pleased to find pages on some of the motels I’m familiar with and a few that I covered in my own book on Highway 99 and my forthcoming work on Highway 101. Those include the Motel Inn – the world’s first “motel” – and the nearby Madonna Inn, both in San Luis Obispo.

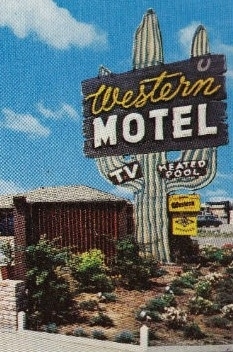

She also includes a vintage picture of the Western Motel in Santa Clara, with its distinctive cactus sign. I took a photo of this one myself for Highway 101, so it’s still there, although (unfortunately) the neon has been removed.

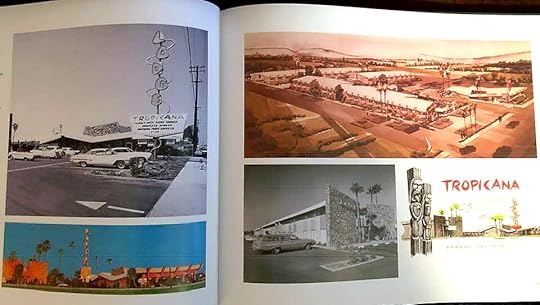

As a native Fresnan and the author of Fresno Growing Up, I also particularly enjoyed the material on Fresno’s old motels, one of which (The Tropicana Lodge) is featured both on the cover as well as inside. I was pleased to see the chapter on signs included both the old Fresno Hacienda sign and the iconic “diving girl” sign from the old Fresno Motel. The picture of the interior of the old Pine Cone Restaurant was a particular treat, as I remember visiting that place as a child and digging into a “treasure chest” for trinkets they gave away to youngsters.

The book is handsomely illustrated with postcards, historic and modern photos, souvenirs and vintage ads, all in vivid color on glossy pages. I was struck by the off-kilter sign on the Jump n’ Jack Motor Hotel (page 28), the camel attraction at the Pyramid Motel in Anaheim (page 60), and the outrigger-style architecture of the Palm Springs Tropics (page 76) and San Diego’s Half-Moon Inn (page 78).

In terms of the text, the book is at its best when it traces the history of the various locations, pinpointing when the motels opened and letting the reader know what happened to them. Something I didn’t know: The Palm Springs Tropics was adjacent to a Sambo’s, which also operated a “Congo Room” cocktail lounge on the site. There’s a cool photo of the interior of the Congo Room, too.

I’ve long been fascinated by once-ubiquitous pieces of our culture that have faded from view over time: old motels, gas stations, shopping malls, department stores, sporting venues, concert halls. For me, buying Motel California was a no-brainer, and I wasn’t disappointed. If your interests run parallel to mine, I’m betting you won’t be, either.

Motel California (184 pages, full color, $45, CalMod Books) is available from the author’s website or via Amazon.

A heroic dragon and a dose of sarcasm: my two latest releases

What happens when you get two book ideas at the same time? Until this fall, I would have worked on one and put the other on the back burner, but when one idea inspires you and you’re facing a self-imposed deadline for the other, you don’t have that option. Besides, when one book is fiction and the other nonfiction, each tends to provide a nice break from the other.

So, over the course of the past six weeks or so, I wrote them both, which explains why I released The Only Dragon and Please Stop Saying That! within a couple of weeks of each other.

The Only Dragon: The Legend of TaraIn point of fact, both ideas inspired me, but under normal circumstances, I probably would have put off The Only Dragon had I not decided I wanted to release it in time for the local Dragon Festival, which was fast approaching. I’d been fascinated by dragons since my parents bought me a stuffed snake (which I insisted was a dragon) as a toddler, and I had wanted to write a dragon story for years.

Finally, I had a good excuse. I would create a fable that explained why the dragon is known the world over, how she – in my book, she’s a girl – came to breathe fire and why the dragon is revered in the east as a symbol of good luck and reviled in the west as a fearsome, demonic creature. I’d throw in a pair of noble wizards, a couple of power-hungry kings, a mysterious goddess-like character and a snarky gray tabby for good measure.

(Coincidentally, I just adopted a gray tabby myself. The vet told me she was male, so I named her Ragnar, only to have the vet reverse herself six weeks later; so, now she’s Khaleesi – Kiki for short.)

Most authors don’t write fables these days, but I love the genre, and it’s something I enjoy writing (see The Way of the Phoenix, Feathercap and some of the stories in Nightmare’s Eve). It offers a poetic way to examine the world around us and what makes us human.

Please Stop Saying That!Please Stop Saying That! is an old idea, as well. It’s a riff on something I did as news editor at The Fresno Bee: I created a local stylebook that included examples of jargon, clichés and buzzwords to avoid when writing stories. It was a serious endeavor, but in the back of my mind, I couldn’t help but laugh at how silly and, sometimes, meaningless they sounded; about how we’d use them without even thinking because they were so deeply ingrained in ourselves and our culture.

Now that I’m no longer a working journalist, I can let some of that sarcasm out, and that’s what PSST! allowed me to do. There’s something in there to offend almost everyone if it’s taken seriously, but it’s not meant to be taken seriously, so please don’t (except for a few jabs at bullying and bigotry, which ought to be condemned whether you’re using humor or not). I toyed with the idea of calling it Think Before You Speak, but I liked PSST! better, in part because it sounded cool as an abbreviation.

Psst. I think you’ll like both these books, the fifth and sixth I’ve released this year. That’s a record for me, and I’m proud of it, but I’m not stopping now. I’ve got plenty of ideas waiting in the wings, and more time than ever before to explore them as a full-time author. This is the life!

August 11, 2018

Facebook friends aren't notches on your "networking" gun

Dear potential online friends: I’m not a target in your networking strategy, and I won't be another notch on your gun. Even if you are authors.

There’s a weird trend going around among authors on social media. They hit up as many fellow writers as possible with friend requests, immediately invite them to “like” their Facebook page ... and never have any other contact with them.

Then, they call it “networking.”

Often, these authors only post about their books, sales milestones and positive reviews; they don’t bother to visit other profiles after their request is accepted, and they don’t manage to post anything much about themselves except for industry stuff.

It reminds me why I never liked cocktail parties, where the whole point of the evening is to make contacts, exchange business cards, and talk about inane subjects everyone is certain to forget five minutes after the party’s over – if not sooner.

I don’t know if the same thing happens in other fields, but I do know I didn’t get a lot of requests from fellow journalists when I was working in newspapers.

Common interestsLook, I like connecting with authors because we have something in common. I also like connecting with Star Trek fans, classic rock connoisseurs, old highway enthusiasts and people who are into mythology. But adding someone to your social media “stable” and then proceeding to ignore them isn’t connecting. It’s putting another notch on that Facebook gun of yours.

I remember going to churches where pastors lamented the need to “grow their flock.” There weren’t enough warm bodies in the pews, and the way they talked about attracting new visitors made it sound like a numbers game. The focus wasn’t on getting to know the people as individuals, it was on adding more “souls” (who could put enough money in the offering plate to keep the church lights on and, of course, pay the pastor’s salary.)

Authors have more of an excuse. It’s difficult to support yourself putting out books, and marketing is as much a part of the job as writing – if not more. When book sales slump, people get desperate and start throwing “publicity” at the wall, hoping something sticks. I know what this desperation feels like: I’m going through just such a slump right now. But I also know it doesn’t work: When people start throwing random ads at me, I tune them out. It also alienates people who might be able to help you if you took a different tack.

Like, maybe, trying to get to know them.

What if you treated social media like a visit to a new neighbor’s home? You wouldn’t go over and knock on the door, wait for it to open, then just stare at the person for a moment and walk away. You’d introduce yourself, give them a bit of background on yourself, tell them it’s nice to meet them and maybe say something complimentary about their home.

Perhaps you find you have something in common; perhaps not. After a couple of minutes, you excuse yourself and leave. Maybe you leave it at that. Or, if you enjoyed the conversation, maybe you ring the person up a couple of days later and invite them out for coffee. Maybe then you start talking a little about your books ... along with other things you have in common. You forge an actual friendship.

One thing you probably shouldn’t do when you go over and introduce yourself is push your way past your new neighbor and into the house without an invitation.

Social protocolsOn social media, that’s what it can feel like if someone immediately sends you a direct message. Somehow, we’ve had a hard time translating the social protocols we’ve developed in the real world to the online environment. Maybe it’s time we started doing so. (When sending naked or half-naked selfies to strangers has become common practice, that’s a pretty good sign we’ve lost our bearings.)

I’m friends with a good number of authors online – because they’ve let me get to know them, and vice versa, not merely because they’re authors. I’m friends with other folks who aren’t writers, too, and I feel more comfortable with some of them than I do with many of my author friends. Because, even though I’m an author, I don’t like to talk about writing all the time. I like to talk about music and history and science and politics and philosophy and a host of other topics, weighty and frivolous.

Lately, I’ve become increasingly more selective about the people whose requests I accept. I’ve become aggressive about weeding out potential spammers and scammers, and I’ve started watching new friends I do accept closely. Do they bother to comment on something I’ve posted? Do they post their own thoughts, or do they just repost links? Are they continually asking their contacts to buy this product, sign this petition or contribute to this cause?

Or are they people, authors or otherwise, who I can feel comfortable being friends with – even if it’s only online? I’m not trying to make people feel paranoid, as though I’ll drop them if I don’t hear from them for a week or a month. I won’t. I just want people whose company I can enjoy without feeling I’ve got a marketing target on my back.

We live in an era when the hard sell has collided head-on with a case of collective amnesia about how to treat others with respect and courtesy. That makes it even more of a challenge do real networking and cultivate real friendships. It also makes it even more imperative that we make the effort to do so. Not because we’re authors, but because we’re ... human.