J.K. Ullrich's Blog, page 21

April 21, 2016

How to Write a Novel, Part 3: Narrative Tension

Has a book ever consumed you? Hooked you so completely that you smuggle it to work and read surreptitiously under the desk, and stay up all night devouring chapters to find out what happens? I read Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix in one sitting, curled in my dad’s blue armchair that matched the book’s cover. Years later, I gobbled up Hunger Games trilogy in less than a week. What is this captivating spell stories cast? It’s called narrative tension, and every book lover has (hopefully!) been an enthusiastic victim. Narrative tension is why we turn the page. It’s an essential concept of storytelling: when characters in a story are blocked from getting what they want, they suffer. In a well-crafted novel, the reader hangs in suspense right along with them, turning page after feverish page to find out what happens.

Tension takes readers on a roller coaster ride through the story: up and down with unrelenting momentum as they hurtle towards the final plunge.

How can we work this magic in our own stories? A novel’s events occur in a pattern that puts mounting pressure on the protagonist. Whenever they resolve one crisis, another larger one already looms over them. Harry and Cedric survive the enchanted maze…but the trophy cup whisks them off to a graveyard full of waiting Death Eaters. Katniss orchestrates Peeta’s rescue from a Capitol prison…but the enemy has brainwashed him to kill her. “Breathers” between crises get shorter as the plot accelerates toward the climax. Peaks of tension draw readers through the story like passengers on a roller coaster.

TENSION TRICKS

Some tried-and-true techniques for heightening tension in a story include:

Conflicting Goals. Give the protagonist someone to compete with or put the protagonist at odds with themselves over a goal.

Time Limits. Imposing a time limit or deadline on your protagonist gives a set amount of time for the goal to be reached, generating tensions as the minutes count down. Tick tock!

Take Away Their Toys. Reduce your protagonist’s arsenal of advantages. Steal their magical weapon, kill their mentor, lose their passport: whatever they need (or think they need) to achieve their goal, take it from them.

Realize Threats. Fire a “warning shot”. Make the antagonist’s threat real. This is where the kidnappers send the investigator a finger in a box: they haven’t killed the victim yet, but they’ve demonstrated the seriousness of their intentions. Give the protagonist a taste of what happens if he/she fails.

Reveal a traitor. Introducing a traitor or hidden rival among your protagonist’s companions hinders the protagonist’s progress towards their goal and–better yet, if you like to torment your characters–inflicts psychological damage.

Beat them to the punch. The opposition moves more quickly than the protagonist and gets to something first, spurring your protagonist to act quickly, either to recover what’s been lost or to come from behind. The Nazis seize the Ark before Indiana Jones does, forcing Indy into action.

Make it personal. Keeping the problem or danger close to the protagonist will keep him/her engaged in resolving it. If symptoms of galactic plague suddenly manifest in the protagonist’s beloved child, he or she will be a lot more motivated to find a cure.

Drop a bombshell. Revelations, twists, or sudden new information can ignite your plot, but this technique comes with caveats. Sudden twists must be relevant to the protagonist’s goal, and should be foreshadowed earlier in the story. Don’t show critical information in from left field and think “whoopee, what a twist!” Tease revelations in advance, otherwise they will seem contrived and readers will feel cheated.

Mood Killers

While certain devices augment tension and excitement in a story, others can bring its momentum to a grinding halt. In an era of notoriously short attention spans, many readers will put down a book that can’t keep them engaged. What makes the “most wanted” list for murdering narrative tension?

Backstory, poorly managed, bogs down your story. Most readers won’t still still, literally or figuratively, for history lessons. “Long ago in this land, [insert tedious paragraphs of background here] happened and threw the kingdom into turmoil”. Info-dumps of this nature are, with few exceptions, the hallmark of amateurs. Drop hints to pique interest, then dole out information gradually in an organic, logical way. Only include background details germane to the story.

Telling too much too soon denies readers the suspense and satisfaction of awaiting answers. If you provide the full biography of a character or history of a situation right up front, readers have no incentive to keep turning pages. You’ve already answered all the questions! Don’t give away everything right away. Make readers work for it! Finally, a form of communication where it’s okay to be a tease.

Wasting time with materials that doesn’t move the story forward will prompt many readers to walk away. Devoted Song of Ice and Fire fans will doubtless excoriate me for this, but I struggled with A Dance with Dragons because many of the chapters didn’t seem to advance the story. “Okay, here’s another interlude of Tyrion cruising with the river-folk…drinkin’ ale and tellin’ tales…where is this going, exactly?” Since most of us aren’t George R. R. Martin, we can’t guarantee that people will plow though the tedious bits of our story instead of putting the book aside. Omit scenes that don’t propel the narrative or reveal character, and trim excess from dialogue and descriptions.

Creating a Storyboard

A valuable exercise for evaluating narrative flow is the storyboard. Jot a one-line description of each scene on a sticky note (or an index card, or in a spreadsheet, whatever works for you). Don’t worry about writing them in chronological order, just scribble down every scene you’ve envisioned for your story. If it helps, color-code scenes by subplot. Once you’ve accumulated a good pile, lay them out in a logical sequence of events and evaluate:

Does tension build towards the climax?

Does every scene contribute something towards the story’s momentum? Remove extraneous scenes or devise a way to make them more germane.

Are there any gaps in the plot? If the layout exposes holes, seeing the events on either side can prompt the development of new scenes to connect the dots.

Are major revelations foreshadowed?

If you’re using multiple points of view, which scenes will use each character’s perspective?

Is the story’s internal logic sound? Are all the questions resolved by the end?

Laying out the pieces like this creates a map of the story’s tension flow and allows you to switch pieces around until you find an optimal arrangement. When you’re satisfied, transcribe the storyboard into a scene-by-scene outline. Congratulations! You’ve got a complete working model of your novel. But where should it start? How do you determine the opening chapter, scene, or line of the book? We’ll explore that in next week’s installment.

April 14, 2016

How to Write a Novel, Part 2: Crafting Characters

Last year, a friend told me she had an idea for a story.

“That’s awesome!” I said. “Tell me about your characters.”

“The heroine is kind of a rebel who sees things differently,” she explained. “Then there’s another girl who represents the establishment.”

I stopped her and threw down some emergency novelist knowledge: characters are people, not parables. If you act out a story with animated representations of the abstract, it’s not a novel so much as a medieval morality play. Everyman calls upon the Wisdom, Strength, and Good Deeds to defeat Temptation! Passable entertainment for culturally (and nutritionally) starved serfs, perhaps, but modern readers expect more complexity. This post, part two of the How to Write a Novel series, provides a quick-and-dirty guide to character essentials.

Characters must want something.

Story happens when the protagonist—the main character, the hero or anti-hero, the central figure whose actions drive the story—strives to overcome an antagonist standing between them and their goal. Antagonists come in two flavors: physical (another person or creature, an enemy or rival) and abstract (an opposing force such as illness, poverty, or nature). Most novels also include a cast of supporting characters who help or hinder your protagonist.

Every one of these individuals must want something. And they must want it badly. Why else would they put up with all the torment we authors impose on them? When creating a new character, I start with this foundational trinity:

Motive: a desire, need, or goal. Chasing this object is what drives the plot.

Obstacle(s): something lies between the character and their goal. It can be external (I can’t be with my true love because a snowstorm cancelled my flight to his city) internal (I can’t be with my true love because I’m still so wounded from my last relationship) or both.

Flaws/Gifts: behaviors, attitudes and beliefs that help or inhibit the character’s progress. These traits are two sides of the same coin: a fiercely loyal character could be easily duped by someone they trust; a pigheaded character might be the only one who perseveres in a tough situation.

Grab a piece of paper and jot down the following for each of your characters:

What is this character’s greatest desire in life?

2. What prevents them from attaining their object?

3. What must the character do in order to succeed?

4. What are the consequences if they fail?

Do the same for your antagonist, if you have a physical one. In the words of canadian writer John Rogers, “You don’t really understand an antagonist until you understand why he’s a protagonist in his own version of the world.”

Characters must take action.

We’ve all heard that good characters are dynamic, but what does that mean? Simply put, it means they do stuff. They don’t just sit there while things happen to them; they make decisions and take action. A story’s inciting incident can be an exterior force, but subsequent events should result from protagonists’ own behavior. What are some ways to kick your characters into gear?

Force them to choose. Often in fiction, bad choices = good story. Present a character with two unpleasant options (for example, do they turn in a dear friend who committed a crime, or lie to protect them?) and see which one they pick.

Challenge their pre-existing beliefs about themselves, others, and the world. If it’s something that matters to them, it’ll shake them into action.

Get them in deep trouble and let them find a way out of it.

Give them a taste of failure. Once they glimpse how awful things will be if they don’t attain their goal, they’ll leap to do something about it.

All this activity spurs evolutions. Dynamic characters undergo meaningful change as the story progresses (or sometimes suffer because of their obstinate refusal to change). By the time they reach the story’s end, they’re not the same person we met in chapter one. Like the seven basic plots we discussed last week, there are three common character arcs:

The Change Arc. An unlikely protagonist goes from zero to hero and reached the end of his or her journey a drastically transformed character. Example: Bilbo Baggins in The Hobbit.

The Growth Arc. A variant of the Change arc in which the character overcomes internal obstacles in order to triumph over external ones. Often this manifests as a maturation or an “upgrade” to either abilities or personality. Example: Harry Potter in the Harry Potter series.

The Fall Arc. Through a series of poor choices and misfortunes, a character descends into depravity, insanity, destitution, or other tragic circumstances. Example: Lily Bart in The House of Mirth.

With all this in mind, add the following to your character sheet:

5. A core strength your character possesses.

6. A serious flaw that could inhibit their progress.

7. Something about the character that will probably have to change before they can attain their goal.

Characters must have conflict.

Personality assessments can be useful tools for exploring character traits and how they influence behavior. Popular tests like the Myers–Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI) and Kiersey Temperament Sorter draw from the psychology work of Carl Jung. More recently, the Five Factor Model established five basic personality elements:

Openness to experience (inventive/curious vs. consistent/cautious)

Conscientiousness (efficient/organized vs. easygoing/careless)

Extraversion (outgoing/energetic vs. solitary/reserved)

Agreeableness (friendly/compassionate vs. analytical/detached)

Neuroticism (sensitive/nervous vs. secure/confident)

The irresistible conflicts, complements, and chemistry of many beloved character combinations draw from these opposites. Think of Mulder and Scully; Jeeves and Wooster; Elizabeth Bennet and Mr. Darcy. Where might they fall on these spectrums, and how does that make them a memorable pair? .None of these personality structures should be used to create cookie-cutter characters; however, they’re good for ideas and a deeper understanding of how people interact.

Back to the character sheet. Add the following:

8. What are some personality traits your character embodies?

9. What major event(s) shaped who your character is today?

10. Who are the most important/influential people in your character’s life, and how how do they cooperate or conflict with your character?

A Protagonist Prototype

Look at the ten data points you’ve compiled. Guess what? You’ve got the foundation of a character profile. It’ll take a little more material to flesh them out–a unique voice, some quirks, physical attributes that might influence how they interact with the world–but you’ve constructed their skeleton. Characters need strong bones to bear the weight of a story on their imaginary shoulders!

April 7, 2016

How to Write a Novel, Part 1: Turning an idea into a story

My writing resume identifies me as an author, a blogger, a freelance journalist…and now an instructor! Last night I began teaching my first creative writing class a local college. The course helps participants launch their first novel, from the germ idea through the first chapters. While I don’t claim to be an expert in the discipline—Ernest Hemingway famously said that writing is a craft where no one ever becomes a master—I gained a great deal of practical knowledge in the years it took me to produce my debut novel, Blue Karma. That book took over a decade from inspiration to publication. Why? Because none of my creative writing classes had equipped me with the specific tools for novel-craft.

Being a good writer is not the same as being a good storyteller. They are complementary but discrete skills. Few traditional creative writing classes deal with long-form storytelling in a comprehensive way. The internet brims with advice on novel-craft, but first-timers may find it overwhelming. Story ideas are daunting enough without a thousand disembodied voices telling us how to manage them! So I designed the course I wish I’d had thirteen years ago: a complete guide for developing one’s nebulous story idea into a functional novel-in-progress. If the first session is any indication, other writers appreciate that approach as well. My participants have already delighted me with their rich imaginations, diverse literary exposure, and passion for good stories. I can’t wait to watch their projects grow.

Have you always dreamed of writing a novel? For the next eight weeks, you can follow along with the class on my blog. It’s no substitute for the in-class workshop (or the entertainment of hearing my elaborate vocabulary pronounced in diphthong-riddled mid-Atlantic English) but I’ll post highlights from each session to help you:

evolve your nascent story concept into a complete, executable form;

examine and develop the unique mechanics of novel-craft; and

create a manageable production plan to eliminate excuses and finally write your book.

Ready? Lasso that idea that’s been lurking in your brain for years and let’s get started.

Session 1: Developing An Idea Into A Story

F. Scott Fitzgerald quipped that “character is plot, plot is character.” I agree, but few story ideas start with a fully realized protagonist. Most writers operate on much vaguer beginnings: “I want to write a story about the Oregon Trail,” or “what would life be like on Earth if the air was too polluted to breathe?” Nebulous ideas are wonderful and inspiring, but they are not stories. Not yet. They need a little refinement to reveal their promise. For refining scattered ideas into a viable story starters, I use an exercise I call fiction fractals. It’s based on Randy Ingermanson’s popular “snowflake method,” with some adaptations of my own.

Math and geometry geeks know fractals as simple processes that repeat in patterns of potentially infinite complexity. (Run an image search for fractals; some are stunningly beautiful.) We can approach story development in a similar way. Viewing a novel as small component parts rather than an unwieldy whole makes it much easier to work with, and much less intimidating. Most novels, regardless of genre, contain five key events: inciting incident, point of no return, raising the stakes, climax/crisis, and dénouement. These elements often appear crammed onto a scalene triangle in the notorious “rising action” plot diagram:

While it’s easy to identify those elements in a story you know well, teasing them out of your own vague idea can be daunting. Luckily, you don’t have to write the whole novel right away, or even the whole outline. You only have to write a sentence. Yes, a single sentence.

Summarize your story in one line

Imagine it’s the blurb in the New York Times book section and gently corral that wild idea into a line that captures its essence.

An orphaned boy discovers he possesses magical ability and defeats an evil wizard (Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s/Philosopher’s Stone)

A girl witnesses racial inequality when her lawyer father defends a black client in 1930s Alabama. (To Kill A Mockingbird)

Well, that wasn’t so scary. Now you’ve got a seed crammed with your story’s DNA. You’ve identified your protagonist, antagonist, and the main trajectory of action. Since writing one sentence was pretty easy, let’s write five more.

Expand one sentence into five

Turn that seminal sentence into a quintet, with each line corresponding to one of the five fundamental novel elements:

Orphaned Harry Potter receives a letter of admission to a wizardry school [inciting incident].

Harry gives up “normal” life to embrace his magical heritage and attend Hogwarts [point of no return].

Harry and his new friends investigate events concerning the Sorcerer’s Stone, the evil wizard Voldemort, and Harry’s own past [raising the stakes].

Harry discovers Voldemort wants the Stone to restore himself [climax/crisis].

Harry thwarts Voldemort’s effort to obtain the Stone [denouement].

This five-line “fractal” provides the skeleton of Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone. If you want an even more detailed overview, expand each of those five sentences into a short paragraph. You’ll end up with a one-page narrative snapshot of your novel. Below is an illustration of the entire process, using the movie Shrek.

From one humble sentence, the story branches out in increasing detail.

The fractal Effect

Here’s where my approach differs from Ingermanson’s. While his snowflake analogy encourages writers to keep expanding in granularity, I prefer to keep using the five-point structure to develop different aspects of the story. Combining multiple quintets creates complexity, like the repeating process of a fractal. The Hunger Games, for example, presents readers a concurrent political story and love story:

Each of these storylines has its own independent logic and integrity. Told as a tale of rebellion or as a dedicated romance, the story mechanics of The Hunger Games would still function, but the result would be a very different book. Weaving “fractals” together adds dimension. This is one way to cultivate subplots in your novel idea. After all, subplots are really just side stories, and should follow the same five-point structure as any other story.

are all stories that simple?

“Okay,” you’re probably thinking. “That’s great for straightforward books, but what about more complex ones? My novel involves multiple protagonists and an intricate web of events–there’s no way to distill such an epic into a five-line summary!” Maybe not, but a sequence of them might do the trick. To demonstrate, I tackled Anthony Trollope’s classic satire The Way We Live Now.

Originally printed in serialized form, The Way We Live Now follows the intrigues of about a dozen major characters in the course of almost 350,000 words, parsed into more than one hundred chapters. And guess what? We can distill it into component parts. I created the following chart for just three of the major players: the scheming entrepreneur Augustus Melmotte, his stubborn daughter Marie, and the cad Felix Carbury. Color-coded cells show where characters’ events combine and collide.

Creating multiple character timelines like is also a good way to explore different potential angles for your story. In a few minutes, you can jot down an outline from each character’s perspective and determine which one (or ones) best suit your novel, instead of writing thousands of words before discovering your story is really about someone else. After all, “plot is character”. Once you’ve determined the basic arc of your novel, finding its true protagonist is critical to the story’s success. We’ll talk about this next week, in the workshop on character.

March 31, 2016

Cultivating Plots: How to Grow your Trilogy

After a wild winter here in the mid-Atlantic, spring has finally arrived. Daffodils bob on the highway medians, the famous local cherry trees cast pink carpets under my feet when I run, and my Laddie gulps allergy pills with his morning coffee. I can’t wait to get my hands in the soil, but for the past few weeks I’ve been neglecting my flowerpots (and my blog—I need to get that New Year’s Write-olution back on track!) for a different husbandry project: revising the manuscript of The Darksider pt I.

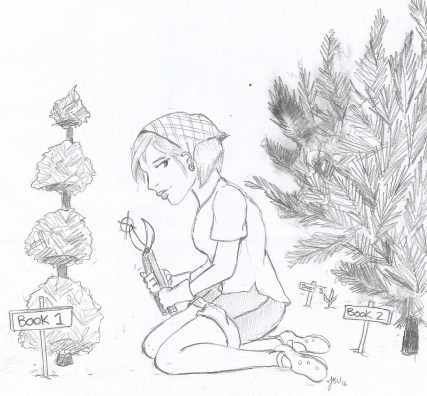

Like an invasive weed spreading across the yard, my re-writes have spread out of control. I’d hoped my lessons from Blue Karma would result in a better first draft, avoiding the kind of overhaul my debut required. Instead I’m fighting my way through a dense, tortuous hedge maze of a manuscript. If I were pruning a plant instead of a story, I’d have dirt under my nails and bloody bramble scratches on my arms. (Actually, Darksider does have a Thorn. And an Ash, and a Hazel, and a Willow…the joke will make sense when you read the book, I promise!)

Why the unexpected challenges? It turns out that trilogies are a different species of story than standalone novels. Although the fundamentals are the same–every story needs characters and tension, just as every plant needs sunlight and water–serial fiction demands some special tending. Here are four “gardening tips” I’ve learned while writing The Darksider:

1. Trilogies are perennials. Facts established in the first book carry through to subsequent installments. If you don’t keep track of how everything fits together, you risk inconsistencies popping up in your story like forgotten tulip bulbs in a vegetable garden. So take the time to get it right. Outline the entire series in detail to ensure the narrative thrives throughout all its seasons.

Master Gardener: Margaret Atwood. The Maddaddam trilogy retells parts of its story from different characters’ perspectives and backtracks to recount events mentioned in earlier installments. Atwood keeps the details straight, although she published the three books several years apart.

2. Plant your seeds deep. Book one is fertile ground for seemingly insignificant details that, later in the series, burst into prominence like crocuses erupting through the last snow. Planning to reveal a character’s past in book two or throw a big plot twist in book three? Tease it early. Story elements with roots in the first book will be sturdier and more satisfying for the reader.

Master Gardener: J.K. Rowling. The Harry Potter series became a decade-long Easter egg hunt for analytical readers like me, who soon learned to consider every scrap of information as a potential clue. Deceptively minor details (Harry spots a tiara among the other junk in the Room of Requirement) later prove critical (the tiara is a Horcrux!) providing rich continuity across the stories. Everything feels deliberate. This, to me, is a true master technique for serial fiction.

3. Fruition takes time. My favorite Thai dragon pepper plant doesn’t produce chillies the moment I plop it in the potting mix, and the same goes for serial fiction. The main arc unfolds more gradually when spread out over three installments. This doesn’t mean it should be boring—far from it—but allow the plot time to mature. Let readers watch it ripen and anticipate the juicy harvest. If you’re impatient like me, adjusting your mental pace can be a challenge. But if you discipline yourself to it, it’s worth the wait.

Master Gardener: George R. R. Martin. Okay, Martin might actually be too patient. A Song of Ice and Fire has become a sprawling cottage garden, with seemingly endless characters and subplots twining around one another. But you can’t deny he’s incredibly patient in cultivating his plot, and fans around the world are salivating for more story.

4. Pruning encourages growth. Multi-part tales should be long and meandering, right? Wrong. Prolix undergrowth can choke out the drama and leave readers fighting through dense thickets of prose in search of the story. Don’t be afraid to transplant and trim. The story will grow stronger, and you might even find some better ideas hiding beneath the dead wood.

Master Gardener: Suzanne Collins. The Hunger Games trilogy features very little extraneous material. The story moves with brisk purpose and keeps readers turning pages. It’s as tight as a topiary, honed and sculpted into a sharp piece of fiction.

Serial fiction can be a challenging variety, but these tools will help your stories flourish!

March 1, 2016

Piece of the Pie Chart: Statistics of Success in Indie Publishing

It’s the cherished fantasy of every aspiring author: your debut novel, beautifully bound with the stamp of a respected publishing house branded on its spine, shiny new copies stacked and gleaming on a bookstore display table like doubloons in a pirate’s hoard. Royalties roll in and, with the handsome advance on your next till, you tell your boss to stick it, quit your day job, and live the bestselling dream.

Unrealistic? Probably, but perhaps not for the reason you think. My recent cyberspace sojourns turned up a report from AuthorEarnings.com, comparing the incomes of new authors who publish through traditional methods and those who choose the indie route. Whether you’re a writer or a statistics geek, it’s well worth reading. Candy-colored graphs and pie charts—who doesn’t love a good pie chart?—reveal startling insights into the mathematical reality of today’s publishing world. At the time the report posted in 2014:

E-book sales accounted for about one third of a traditionally published author’s income.

More new indie authors were making a living from e-books than their traditionally published counterparts, especially writers of genre fiction (like yours truly).

Almost two-thirds of major publishing house profits came from established authors, not newcomers or “debut” authors.

Indie authors might never enjoy massive book launch parties or lines around the block for their next tile, but if you could live comfortably on proceeds from your writing, would you really mind?

All these numbers add up to a surprising conclusion: your chances of becoming a financially successful author are better as an indie.

“Of the 500 or so Big-5 debut authors in 2013, only 245 (fewer than half) are today earning $10,000 or more from their Kindle e-books…By contrast, we see over 700 Indie-published authors who debuted in 2010, 2011, 2012, and 2013 who are today earning more than $25,000/year from their Kindle e-books alone.”

Granted, 700 is still not many. However, the e-book trend has only increased since the time of the AuthorEarnings report, shattering the old publishing paradigm and putting more power in the hands of authors and the readers who support them. The odds may still not be in our favor, literary rebels, but in the arena of book sales, self-publishing gives us a fighting chance at victory.

February 18, 2016

The Cosmic Catwalk: Designing Functional Fashion for Sci-Fi

As New York City wraps up Fashion Week, I’m wrapping up a design challenge of my own. When it comes to haute couture, I can’t tell Givenchy from a grocery bag, but occasionally my stories demand a little costume consideration. This is particularly critical in The Darksider. The characters undertake scavenging expeditions on a ruined planet, so their clothing must protect against elements, predators, and the deadly particulates in the atmosphere. As I wrote a scene involving a malfunction in this equipment, I realized I had only an indistinct idea of what it looked like and how it worked.

Imagined technology must satisfy two criteria: plausibility and functionality. Having a sophisticated, space-colonizing society gives me a little leeway on the first one, but I don’t want technology to overwhelm with the narrative. It should enable the story without distracting from it. Scrolling back to earlier chapters, I realized–with the horror fashionistas must feel at mingling stripes and plaids–that I’d described the uniform inconsistently. This is problematic in itself, but also meant characters were acting in ways that might not be physically possible in their outfits. For example, one scene has two divers get into an altercation: you couldn’t land a punch on someone’s jaw if they were wearing a full-face helmet!

Since this apparel is so integral to how the characters can interact with their environment, and with each other, I had to get it right. So back to the drawing board. Literally. Rather than struggle to keep the details straight in writing, I did a concept sketch. I’m not much of a fashion designer, nor an artist, but this exercise forced me to think critically about the equipment I was creating.

A little web research showed me that sterile garments won’t work for my characters. Proper containment suits require an oxygen supply to maintain negative pressure. My “divers” need to clamor through derelict buildings and outrun predators; they can’t be leashed to air hoses, or waddle along under the weight of a tank. Mobility is paramount. Flexible bodysuits make more sense, but thin, stretchy fabric wouldn’t afford much protection. The compromise? A snug, military-inspired jumpsuit reinforced with joint pads and a light chestplate. I modeled the armor on protective sports gear, like that used in paintball and–I admit–the knee and elbow pads I wore rollerblading as a kid. Dorky? Maybe. But I like the allusion to a playful childhood these teenaged characters don’t get to enjoy.

A little web research showed me that sterile garments won’t work for my characters. Proper containment suits require an oxygen supply to maintain negative pressure. My “divers” need to clamor through derelict buildings and outrun predators; they can’t be leashed to air hoses, or waddle along under the weight of a tank. Mobility is paramount. Flexible bodysuits make more sense, but thin, stretchy fabric wouldn’t afford much protection. The compromise? A snug, military-inspired jumpsuit reinforced with joint pads and a light chestplate. I modeled the armor on protective sports gear, like that used in paintball and–I admit–the knee and elbow pads I wore rollerblading as a kid. Dorky? Maybe. But I like the allusion to a playful childhood these teenaged characters don’t get to enjoy.

The most critical piece of the ensemble is the mask. From a writer’s perspective, this one was tricky. The plot hinges on a deadly airborne contaminant, so the characters need some form of respiratory protection. But making them spend the majority of chapters encased in clunky helmets inhibits character interaction. How could you read a friend’s expression or shout through a deserted building? For the story’s sake, this essential bit of equipment needed a low-profile design. I envisioned something similar to a CPR rescue mask: clear, light, and pliable. This fits the minimalist aesthetic of the uniform and, more importantly, doesn’t inhibit too much activity.

The most critical piece of the ensemble is the mask. From a writer’s perspective, this one was tricky. The plot hinges on a deadly airborne contaminant, so the characters need some form of respiratory protection. But making them spend the majority of chapters encased in clunky helmets inhibits character interaction. How could you read a friend’s expression or shout through a deserted building? For the story’s sake, this essential bit of equipment needed a low-profile design. I envisioned something similar to a CPR rescue mask: clear, light, and pliable. This fits the minimalist aesthetic of the uniform and, more importantly, doesn’t inhibit too much activity.

Hazel–a plucky secondary character and m new favorite child–models the 2016 Darksider spring collection.

The remaining accessories all have a purpose. Heavy goggles protect eyes from ultraviolet and irritants; a gadget strapped to the wrist provides navigational and communication capabilities; the belt carries tools and a holster for the small sonic weapons used for self-defense. Nothing is superfluous. This ensemble is the product of a resource-strapped community that wouldn’t waste a scrap of material on decoration.

Combine all this in a quick lunch-break pencil sketch, and what do we get? The 2016 Darksider spring collection! It’s rough–Hazel here won’t be strutting down the cosmic catwalk anytime soon–but having a reference sketch will keep descriptions consistent throughout the story. (That said, readers, feel free to imagine the outfits however you like when the book comes out this spring!)

February 17, 2016

T5W: Best Suggested Books I Loved

It’s been a while since my last T5W! I almost missed this one, but tweets from a few of my favorite book bloggers inspired/shamed me into last-minute participation.

It’s been a while since my last T5W! I almost missed this one, but tweets from a few of my favorite book bloggers inspired/shamed me into last-minute participation.

Not surprisingly, the people closest to me are devoted bibliophiles. I’ve read many, many books on their recommendations. The following are just a few enduring favorites I’ve discovered through suggestion.

Oryx and Crake , by Margaret Atwood. I think this was the first book my Laddie ever recommended to me, several months after we started dating. The book captivated me, and I knew a man who admired it so greatly must be exceptional as both a reader and a thinker (a year and a half later, I put a ring on it)!

City of Thieves, by David Benioff. This recommendation came from my Dad. He’s a fellow English major and closet writer. (Literally: he used to have a tiny office in his bedroom closet, crammed with books. Hunched at a desk barely large enough to seat his 6’6 frame, and jotted notebooks full of ideas that I’m still nagging him to turn into novels. At least co-author one with me, Dad!) We’ve always had a special connection over books. Of the countless titles he’s recommended to me, this remains one of my favorites.

The Poisonwood Bible, by Barbara Kingsolver. This book gathered dust on my reading list for years until my Mom finally read it, praised it highly, and lent me her copy. How could I have ignored it for so long? The prose, the voices, the keen observations on both nature and humanity are peerless.

Boy’s Life, by Robert McCammon. My Laddie was far, far away from me on a business trip when he finished this book. “You have to read this,” he told me over a long-distance connection. Not only did I love the story and the magnificent writing, it eased the separation a little. Running my eyes over lines he’d just read was the literary equivalent of snuggling.

All Quiet on the Western Front, by Erich Maria Remarque. Another favorite of my Dad’s, I read this around the time I moved out of my parent’s house after college. The young narrator’s experiences in a harsh war environment resonated with my own maturing awareness of the world.

Bonus pick: The Hunger Games, by Suzanne Collins. This wasn’t technically a recommendation. A friend lent me his copy with the caveat “you have to read for yourself how violent and awful this is!” Guess I’m a monster, because I loved it and gobbled up the rest of the trilogy inside a week. This is where it’s useful to know your friends’ tastes: their recommendations can still be useful, just take them in reverse!

Top 5 Wednesday is the creation of Lainey over at Goodreads. Check out the group and join the other “Wednesday-ers“!

February 13, 2016

Groundhog Day: Recurring Draft Doubt and How to Beat It

As if insults on a chocolate foil weren’t enough, now cough drops are attempting psychotherapy. Unwrapping a lozenge yesterday, I found the paper printed with aggressive encouragements:

“You can do it and you know it!”

“Flex your can-do muscle!”

“Fire up those engines!”

It read like a lemon-and-menthol Jillian Michaels. I laughed because just moments earlier I’d berated myself with identical sentiments. Not about being sick—“suck it up” is already central to my wellness mantra—but about finishing The Darksider Pt I.

I’ve almost finished the draft. Another ten thousand words and the story’s bones will be assembled. Then I’ll have to face the inconsistencies, placeholders, and unsatisfactory passages I’ve left behind me in the manuscript. I remember reaching this point with Blue Karma. I know what comes next: Groundhog Day. Every time I near the finish line, a unique species of vermin re-emerges: the Inner Critic.

This plot is flatter than that old beer you tried to serve at your Super Bowl party! the Critic hisses at me. Better kick this cold, because if you sneeze, you’ll blow away those paper-thin characters. You’re really going to follow an award-winning debut with this half-baked, derivative space opera that’s only part of a larger story?

This plot is flatter than that old beer you tried to serve at your Super Bowl party! the Critic hisses at me. Better kick this cold, because if you sneeze, you’ll blow away those paper-thin characters. You’re really going to follow an award-winning debut with this half-baked, derivative space opera that’s only part of a larger story?

The Critic casts a long shadow over projects. Motivation and creativity wither in its shade. With a tantalizing new idea lined up for my next novel, I’m tempted to suspend work on Darksider and escape to a fresh narrative landscape, where no derisive thoughts can burrow in and erode my confidence. But I’ve seen this before. Although I haven’t succeeded in pushing the Critic back underground, surviving this freeze-out once taught me a few things that help me look beyond its umbral influence.

Believe it or not, an indie author platform offers built-in protection against quitting, because you have to generate buzz for your next book long before it publishes. It demands commitment. I’ve been teasing Darksider for months and even referenced it in interviews. To say “just kidding, maybe another time!” would make me feel like a reprehensible flake. Who knew blogging could provide such stability? Traditional authors whinge about deadlines from a demanding publisher, but no literary agent could be as compelling as a promise to one’s readers.

Not only that, I’ve poured a lot of hours into this story since finishing Blue Karma last summer. Giving up now would waste months of work. Moonlight novelists like me can’t be frivolous with our writing time. Fiction doesn’t pay my bills: I schlep to an office every day and scrape up time for stories afterwards, neglecting sleep, chores, friends, and other aspects of normal non-writer life. At more than 40,000 words and counting, Darksider has almost reached a salable length. That’s too much progress for an indie author, who needs titles to build her brand, to just throw away.

But I find my greatest resistance to the Critic is simple recognition. After my first rodeo with Blue Karma, I know this specter is just a stage of the writing process. I know when I finish the draft, I’ll feel relieved at the accomplishment and daunted by the prospect of revision. I’ll obsess over rewrites until I’m thoroughly sick of the story and dump it in my Laddie’s lap for a first read. Stories have cycles. Seasons. The shadow will wane, my doubts will thaw, and my book will finally bloom.

Does your Inner Critic return to cast shadows on your projects? How do you overcome it? Share your experiences in the comments—I’d be glad for some new perspectives!

February 2, 2016

Passion and Possession: Thoughts on Writing from My Former Self

Moving one’s residence is stressful enough without the complications of a historic snowstorm! Between shoveling, packing, and shuttling carloads of stuff down icy roads, I’ve hardly touched my computer all week. However, I did make a discovery that merits sharing.

While boxing up the home office, I found several old journals, including one I kept during my college semester abroad in Ireland. Part travelogue, part personal misadventure—I read some of the funnier excerpts aloud to my Laddie and he thinks I should publish it—the narrative represents a fascinating episode in my own personal development. It’s emotional archaeology, excavating the thoughts and feelings of a bygone part of myself. What struck me most was a passage that has nothing to do with travel:

December 13, 2006

…I’ve just taken a hammer to the plot of my novel-in-progress. Again. For the third time since starting the project, I find myself having to rethink the entire story and restructure the entire plot. It’s that weird, productive pain—you feel kind of good about it, knowing that it’s a positive change, but that doesn’t make it any less excruciating.

…The love of words is a disease, the passion to write a destructive, consuming force. Less passion than possession. The harder you repress the thoughts, the stronger they become, preying on your consciousness and stabbing you awake at night. It’s a condition, one that I’m beginning to accept as lifelong. Sometimes I feel like I’ve only got one foot in this world: the rest of me is off drifting in that liminal space known as la-la-writer-land. Stories, images, and ideas all bubble in my brain, and the steam from the brew sometimes clouds my vision of reality.

…I feel like my brain is scarred from the incessant clawing of ideas. Each word comes out of my fingertips like a needle through skin. Sometimes it leaves me wanting to scream, run my head into the cinderblock wall, and burn every page I’ve ever written into a terrible, glorious blaze. But it’s the only thing that leaves me satisfied.

I can’t remember what story I was working on at the time (it might have been an early ancestor of Blue Karma). But beneath the post-adolescent flair for drama lay a sentiment that haunted me as I read it. I wish I could reach back to my past self and tell her “Don’t quit! In less than a decade, you’ll publish an award-winning novel and find yourself writing with confidence almost every day.” Would twenty-year-old me have believed it? In the most private sanctums of her spirit, I don’t think she ever doubted it, but present realities often occlude hope in positive outcomes. Cloistered in a student dormitory in the dreary Irish winter, discouragement can grow on a young soul like mildew on the cinderblock walls.

Hearing my own voice echo through the years also put my present-day dilemma in perspective. I war with myself constantly over whether I should devote more energy to advancing my “day job” career or keep pursuing my novels. This old journal entry suggests that if I have a “calling”, this is it. Writing stories is coded in my DNA, as irrepressible as my ear for music and immutable my Athena-grey eyes. It took longer than I’d expected to get started, and it will probably take longer than I’d like to achieve commercial viability (if I ever do). But I no longer suffer the agony of the blocked artist. I’ve harnessed the rampant beast of creativity: it’s not fully tamed, but we’ve achieved a productive symbiosis. After almost a decade wrangling with my literary impulses, I finally feel like I’m on the right (write?) path. I hope I feel this much sense of progress when I look back again at this blog post, nine years from now!

January 21, 2016

Gender and Genre: Female Sci-Fi Authors are NOT an Alien Species

Okay. Rant time.

Remember when Blue Karma won some indie publishing awards late last year? One of the granting organizations just published interviews with the winning authors. Awesome, right? Except for one thing:

“[We] recently caught up with author J.K. Ullrich, whose book Blue Karma won the science fiction category. You can click the link below to visit [our] website and read more about his winning book and his writing process.”

Really? Just because I wrote a science fiction novel, they assume I’m a man? The actual interview refers to me correctly as “she”, so someone else must’ve written the intro. Clearly that person didn’t bother to glance at my website, else the photo would’ve answered any question of my gender. My initials, J.K., reveal nothing. So based on no information other than my authorship of a science fiction novel, someone assumed I was male. This irritates the hell out of me for three reasons:

Assuming such basic facts is just sloppy journalism.

I’ve spent almost 30 years fighting chronic misspelling and misreading of my given name that often leads careless people who haven’t actually met me to assume I’m male (every time I get an email addressed to “Mr. Ullrich”, I want to write a snotty response informing the sender that the only Mr. Ullrich is my father). Using my initials as an author was supposed to prevent this nonsense.

It’s 2016, people; time to accept that science fiction is no longer dominated by male authors and fans.

Female authors are historically underrepresented in sci-fi. But thanks to luminary ladies like Margaret Atwood, Octavia Butler, and Ursula LeGuin blazing trails in the genre decades ago, a new generation of women like myself are using fiction to explore new worlds. Anyone who keeps up with literary trends should never assume gender based on genre. I’d bet that if “J.K. Ullrich” was emblazoned on the cover of a bodice-ripping romance novel, no one would be attributing male pronouns to the author.

In an age when pronouns and gender identity are increasingly a matter of personal definition, such assumptions are even more offensive. Earlier this month, the American Dialect Society voted the word “they” as 2015’s word of the year because of its growing popularity as a gender-neutral pronoun option for individuals who choose not to identify with the traditional male/female binary. It’s ironic that while people are enjoying greater freedom in pronouns that occlude their gender (a linguistic evolution I support, despite the slightly problematic grammar) a heterosexual woman has to fight for a boring old female pronoun.

What do I need to do? Replace my book jacket photo with a snapshot of my genitals? Change the “J” in my initials to Jessica or Juliette or something that small minds can easily identify as female? I do know what I will not do: stop writing the genres I like. I’m proud to be a female sci-fi writer, even if some people still consider that an alien species.