J.K. Ullrich's Blog, page 20

May 28, 2016

Recent Reads: Subversive, by A. Deen

May 26, 2016

How to Write a Novel, Part 8: Publishing

May 25, 2016

“Blue Karma” Birthday Book Bargain!

May 19, 2016

How to Write a Novel, Part 7: Revision and Editing

May 17, 2016

The Invisible Woman: Sexual Segregation in Sci-Fi

May 16, 2016

This Thursday: live Twitter chat with me and Self-E!

May 12, 2016

How to Write a Novel, Part 6: World of Wordcraft

Words are more than just a vehicle for our stories. They’re a writer’s medium. We paint with prose and sculpt with sentences. Language is like some ancient, malleable magic we channel into an infinite number of spells. It sets scenes, establishes character, and conveys action. But a true mage goes beyond these essential functions. The right words can evoke sensory experiences, create striking images, and play irresistible melodies in reader’s ears. How can you harness the wizardry of words in your writing?

Sense and Sensibility

Readers have many senses; engage all of them! There’s the classic five—sight, sound, touch, taste, smell—but don’t stop there. Emotions often manifest as physical sensations. There’s proprioception (the sense of one’s own body parts and movement) and chemical feelings like breathlessness or an adrenaline rush. Use your writer’s sensibilities to determine which sensory details give the best impression of a scene, character, or experience.

Rich sensory detail immerses the reader in your story, turning printed words into a vicarious experience. The imaginary world emerges as a place readers can hear and touch. A scene set in an amusement park needs observances like the shriek of roller coaster riders and the sweet, oily aroma of funnel cake to bring readers to that familiar place. If they’ve never had the experience you described, let them live it vicariously through your story. Make it real. Capture small, unique details to convey the essence of an experience.

Details add more than appearance. The right details allow readers to infer things. For example, I could tell you my room contains a sofa, a lamp, and a desk. It’s a list of furniture, nothing unique about it. But if I say “the tattered arm of the sofa elbowed the leg of the desk,” you might picture a cramped, shabby space. “Light from the single bare bulb revealed socks lurking under the furniture like skittish mice” suggests the occupant isn’t much of a housekeeper. Which description evokes a more interesting image?

Choose Striking Words

Summon words that strike like lightning. Or giant war hammers, whatever works.

“The difference between the right word and the almost right word is the difference between lightning and a lightning bug,” according to Mark Twain apocrypha. Thanks to ruthless pillaging of other languages, English offers marvelous diversity. Mine this hoard for all its riches and choose the most precise word available:

Is that “boat” a yacht, aircraft carrier, cruise liner, barque, or caravel?

Is its “red” flag scarlet, crimson, ruby, auburn, or vermillion?

Each word carries a far more specific meaning than its generic root. Evaluate the connotations of similar words: “glitter” is cold like diamonds, while “glow” is warm like a candle flame. Selecting one or two striking adjectives also eliminates heavy clusters of description that can weigh down your prose.

Word choice is especially critical with verbs. “She walked down the street” conveys action, but “she marched/lumbered/skipped/strutted down the street” offers a dynamic visual packed with extra meaning about the character and her mood. Adverbs may not be pavers on the road to hell, as Stephen King famously suggested, but they’re red flags that indicate weak verb choices. Instead of “he ran quickly,” tell us he sprinted, dashed, galloped, or tore.

S&M (Simile and Metaphor)

Similes and metaphors create opportunities for inventive imagery. It’s easy to tell the difference between the two:

Similes use “like” or “as” to make a direct comparison between two things. Vladmir Nabokov described “elderly American ladies leaning on their canes listed toward me like towers of Pisa.”

Metaphors imply comparison between disparate things, such as “the curtain of night” or T.S. Eliot’s personification of fog as a cat: “The yellow smoke that rubs its muzzle on the window-panes/Licked its tongue into the corners of the evening….”

These devices can bring freshness and depth to writing. With deft handling, they even add layers of symbolism. But they’re also dangerous territory for clichés.

The word cliché sends cold dread dripping down most writer’s backs. These phrases are so overused, they’ve effectively lost meaning. (Fun fact for your next trivia night: the word cliché comes from the French term for the sound of a printing plate that stamps out canned text.) We can divide the cliché family into several sub-species:

Idiomatic expressions: scared to death, cold shoulder, fish out of water.

Stale similes: white as a sheet, brave as a lion, dead as a doornail.

Dull descriptions: lapping waves, rustling leaves, a gnarled oak

These pernicious verbal shortcuts infest our daily speech and can creep into our prose. Nothing says “lazy writing” and turns off readers more quickly than a page full of such unoriginal language. Check out this most wanted list of more than 600 clichés, and be vigilant if they try to sneak into your story. With all the marvelous words out there, why limit yourself to prepackaged ideas?

Feel the Rhythm

Words have music. Writers are conductors, presiding over an orchestra of sounds and blending syllables into symphonies. Short, monosyllabic words create a staccato rhythm. They speed up the tempo, providing an ideal pace for action scenes. Longer words and sentences flow, sweeping readers along like an elegant musical passage. Tuning your ear to these cadences will help put an irresistible beat in your prose.

When you write all your sentences the same way, your prose becomes flat. The pattern lacks variation, making a dull drone of your story. Readers might fall asleep, lulled by the soporific cadence. You’re writing a novel, not a repetitive commercial jingle. If you want to write well, you’ll have to change the tempo. (Notice something strange about this paragraph?)

So hit hard. Keep them alert. When you vary sentence lengths, readers have to pay attention. Make every line a surprise. Long, mellifluous sentences can convey things, too, and you should accord them appropriate space in the narrative. But balance them out. Vary the rhythm of sentences. Play your words like a set of bongos, tapping out different rhythms that tantalize the ear. (Isn’t that more interesting?)

Go forth and write!

As English historian Edward Gibbon observed, “the style of an author should be the image of his mind, but the choice and command of language is the fruit of exercise.” Word wizardry takes practice. Most of the techniques discussed here apply to revision more than drafting, but the more sensitive you become to the magic of language, the stronger your powers become. Keep working, and soon you’ll rule the world of Wordcraft!

May 11, 2016

Top 5 Wednesday: Characters Most Like Me

I thought this T5W topic would be easy. I’ve always identified strongly with fictional characters, and over the years I’ve allied myself with almost every gutsy heroine whoever butt-kicked her way through a novel. But upon considering the subtleties of this week’s challenge, I realized that few of those characters are comprehensively similar to me. Katniss Everdeen reflects my aggressiveness, but she doesn’t have much sense of humor. Eowyn of Rohan shares my restless nature, but she’s melancholy where I’m spunky. Come on, I can’t be that weird! Where my fictional ENTP ladies at? Seriously, can we write some more? (I considered male characters, too, but none exhibited my alchemical blend of cold logic and volcanic attitude.)

I thought this T5W topic would be easy. I’ve always identified strongly with fictional characters, and over the years I’ve allied myself with almost every gutsy heroine whoever butt-kicked her way through a novel. But upon considering the subtleties of this week’s challenge, I realized that few of those characters are comprehensively similar to me. Katniss Everdeen reflects my aggressiveness, but she doesn’t have much sense of humor. Eowyn of Rohan shares my restless nature, but she’s melancholy where I’m spunky. Come on, I can’t be that weird! Where my fictional ENTP ladies at? Seriously, can we write some more? (I considered male characters, too, but none exhibited my alchemical blend of cold logic and volcanic attitude.)

So, in typically analytical form, I established selection criteria. Characters had to embody five hallmark aspects of my personality: cleverness, candor, feistiness, verve, and defiance of traditional female gender expectations. It’s a rarer combination than I expected (If you know of any other books with characters that meet this description, please let me know in the comments; I’d love to read them)! Still, this small sorority has some truly badass members.

Elizabeth Bennett (Pride and Prejudice)

“There is a stubbornness about me that never can bear to be frightened at the will of others. My courage always rises at every attempt to intimidate me.”

About three years ago, a “Which Jane Austen Heroine Are You?” quiz identified me as Miss Bennett by an overwhelming margin. Internet personality tests are usually as accurate as a Magic-8 ball, but I think this one nailed the assessment. Both Lizzy and I are witty and ebullient. We may not be the most beautiful girls in the room, but our personalities sparkle more brightly than Lady Catherine de Bourgh’s jewels.

Our winning extroversion allows us to indulge ourselves as parlor anthropologists, observing and analyzing the absurd behavior of others. We share this study, and a special intellectual bond, with our book-loving fathers. Dad enables our non-conformity to feminine cultural expectations, perhaps because he has no sons of his own. He’s one of the “few people whom I really love, and still fewer of whom I think well.”

There’s one other person on that shortlist. Who’d believe it’s aloof, laconic hero brooding in the corner? But vivacity and solemnity make an excellent match. Last summer I finally got my Laddie to watch the five-hour miniseries of Pride and Prejudice. Halfway through he commented “I don’t know why everyone is so down on Mr. Darcy. I think he’s pretty awesome.” I cracked up laughing. “That’s because he’s you!” Leave it to a story nerd like me to mirror, unintentionally, one of literature’s greatest romances.

Zarine ni Bashere t’Aybara (The Wheel of TIme Series)

“I’ll not have you bleeding to death on me. That would be just like you, to die and leave me the work of burying you. You have no consideration.”

Fantasy isn’t my preferred genre, but this series includes some of the most incredibly complex, strong, and believable female characters I’ve ever encountered. One of them is fiery Zarine, who adopts the nickname “Faile”, or falcon. We’re both adventurous, spirited, and slightly crazy by most people’s estimation. Blades are our preferred weapon class: she fights with knives and I was a champion fencer in college. Even our physical descriptions align: tall and slim with aquiline noses. (Can we please have more heroines with big, bold noses to match our big, bold personalities? I get tired of reading about all these girls with small, straight schnozes.)

But resemblance goes deeper the skeletal structure. We’re both prone to jealously, impulsiveness, and a touch of Machiavellianism. Although fiercely devoted to our husbands (both inherently quiet men who sometimes find our passion bewildering) but don’t hesitate to call him out or pursue our objectives alone when necessary. “Falcon” is an apt alias for us: swift, sharp predators who strike before you know what hit you.

Hermione Granger (The Harry Potter series)

“The truth is that you don’t think a girl would have been clever enough!”

Who is that girl in the front row, her hand rocketing into the air every time the teacher asks a question? She shatters grade curves, hauls way too many books around with her, and has nightmares about failing a class. It’s…me, in university? Like Hermione, I loved school and obsessed over getting top marks. I started attending college at age 15, a dually enrolled high school student, and on my very first exam scored the highest grade in class. The “brightest witch of her age”? Perhaps. I always strove for perfection. To this day, it irritates me that one professor gave me an A- and ruined my virgin GPA. I’ll wear that the scarlet number 3.98 on my heart forever.

While many girls conceal their brains for fear of losing appeal among boys (sadly, this pernicious habit carries from the classroom into the boardroom; I’ve seen it in professional circles as well) Hermione and I proudly share our knowledge and devour more at every opportunity. Some people admire our cleverness, some people resent it. The haters can label us however they like–bossy, overachiever, “insufferable know-it-all”– but it’s not our problem, and we don’t apologize for making everyone else look like the slackers they are. People who oppose us quickly learn there’s a temper under our scholarly facade. With the cleverness to back up our arguments, debates often escalate into “blazing rows”.

Sometimes we take on too much and turn into anxious stress monsters. We tend towards over-reliance on facts, so when our formidable research skills don’t reveal a firm answer to a question, we get agitated. Trusting our hearts rather than our heads doesn’t come easily to us. Luckily, we’re brave Gryffindors. We don’t shy away from adventure or challenges. But what tries our courage most is to admit fallibility and say “I don’t know”.

Beatrice (Much Ado About Nothing)

“He that is less than man, I am not for him.”

“Truly, lady, you have a merry heart,” people tell us. By my troth, so we do! It matches our wicked sense of humor and bantering tongue. Suitors may prefersweet and docile girls like Cousin Hero, but we speak our minds, heedless of interrupting conversation. Our scathing retorts delight the company. Clever and sarcastic, we like to get the last word (and usually do). Occasionally our jokes reveal private bitterness–careless men have burned us once or twice before–but opening ourselves to love with someone who embraces our liveliness brings out the warmth in our fiery spirit.

Skye (The Darksider trilogy)

“What do you think? Am I everything you feared?”

No, it’s not (just) a shameless plug for my upcoming book. I couldn’t think of many existing characters that met my criteria, but my heroines always contain a bit of their creator. Amaya of Blue Karma drew from teenaged me, all anger and lofty vocabulary words. Skye, although younger in age, reflects more of my adult mindset.

We’re inventors–of ideas as well as material things–but we prefer conceptualization to execution, lacking follow-through. If you hear us talking to ourselves, it’s not because we’re loony. We just have more ideas than our heads can hold, and we’re exploring them aloud. And yeah, sometimes we just want someone to talk to. We hate being alone.

Life is a big, complex game to us, and we’re forever at work on the winning strategy. Empathy is not our strong suit: we have an unfortunate habit of viewing people as subjects and sometimes bait them to see how they react. Despite this rather clinical approach, we find humor in almost every situation and share our jokes to lighten the mood. Not everyone gets them. Not everyone gets us, at least not right away. It takes a little stamina to get to know us, but once you do, you’ll never be bored again. But judge that for yourself when you meet Skye this summer in the first installment of The Darksider Trilogy.

Top 5 Wednesday is the creation of Lainey over at Goodreads. Check out the group and join the other “Wednesday-ers“!

May 5, 2016

How to Write a Novel, Part 5: Dynamic Dialogue

Admit it. You eavesdrop. It’s all right, everyone does. Some anthropologists even assert that humans evolved to gossip, because exchanging information about others informs our social bonds and behavior. In novel-writing, dialogue plays an even more important role: it’s a critical storytelling tool. But fictional conversations differ from those in real life. Novel dialogue must move the story forward. It does this through the twin purpose of revealing character and advancing the plot.

CHARACTER THROUGH DIALOGUE

Dialogue tells us a lot about the speakers and the relationship between them. The way I speak with my Laddie differs from the way I speak with my mother, or my supervisor at work, or my three-year-old niece. But each of these interactions reveals something about me: my snark, my candor, or my willingness to sing Sesame Street ditties in public. We learn characters’ personalities by observing how they converse with one another

Since players in a novel all think and act in different ways, their speech should reflect this. Words are an extension of personality. Vocabulary, tempo, and slang all inform our perception of character. Just be judicious in their use. Too many colloquialisms or non-standard spellings to convey an accent can make text hard to read, or result in offensive stereotypes. Occasional dialect is enough to give impression of voice.

Characteristic doesn’t mean completely realistic. Verbal litter such as “um”, “uh,” “like”, and “y’know” pollutes most people’s speech. We exchange empty pleasantries, asking how someone’s been when we don’t care and automatically responding “fine, thanks” even if it’s a lie. Fiction spares us such tedium. Keep dialogue brisk, clean, and purposeful.

PLOT THROUGH DIALOGUE

When I studied screenwriting in college, I learned how to craft a story comprised almost exclusively of dialogue. With the visual component stripped away, characters’ speech becomes the backbone of the plot. A two-hour film or a 44-minute television episode doesn’t allow time for flaccid conversations. Go read a script or screenplay: you won’t find many extraneous lines. Every word must must convey meaning. Apply this pragmatism to the dialogue in your novel.

If each conversation is a movie scene, it must advance the reel. Most real-life conversations leave us in the same place we began. We might decide what to cook for dinner or update the state of family affairs, but our circumstances remain largely unchanged. In novels, every exchange should move the protagonist closer to (or farther from) their objective. A character might learn something advantageous, receive news that weakens their resolve, or raise more questions to pique the reader’s interest. Dialogue can alter the way characters see a situation, another character, or themselves. It can build suspense and conflict.

Building plot through dialogue doesn’t mean using it as a vehicle for raw exposition. We’ve all seen at least one cheesy sci-fi show where an expendable crew member announces something like this: “Captain, the reactor core is overheating! If it reaches one thousand degrees, the whole ship will explode!” Any captain would know perfectly well the consequences of an overheated reactor core. The explanation exists for the audience’s benefit, and forcing it into a character’s mouth makes the dialogue feel fake.

People don’t tell each other things they already know. A husband wouldn’t tell his wife that “Peggy, my twin sister, had to take our mother, Florence, to the hospital again because of her chronic illness.” She would already know who Peggy is, and that her mother-in-law suffers from poor health. The husband would say simply: “Peggy had to take Mom to the hospital again.” Will this confuse the reader? On the contrary. It prompts questions, and the reader will keep turning pages for answers.

Staging Dialogue

Are these faceless Teletubbies floating through a cloud? Maybe a tangible environment would help fill in those speech bubbles.

Conversations don’t happen in vacuum. People talk in the context of action: drinking coffee, doing chores, driving down the highway. Rooting dialogue in a physical environment makes the story feel more authentic and adds nuance to the scene. Actions and descriptions control the pace of dialogue, and even reveal character. For example:

A nervous person might pick threads off their suit during a job interview.

Someone arguing while they cook dinner might chop an onion with vehemence.

People sitting in a ballpark might converse amid the crack of bats and the holler or beer.

Weaving behavior and backdrop into dialogue avoids the ping-pong effect of characters throwing sentences back and forth out of context. It also affords space for the most powerful statement of all: silence. What characters don’t say can reveal more than words. Silence can communicate discomfort, disagreement, anger, satisfaction, apathy, and more, depending on how it’s framed. While one character talks, their conversational partner might stare at the floor, fiddle with jewelry, or indicate their emotions in some other way.

DIalogue ATTRIBUTION

In my teenage years, I believed that writing “he/she said” lacked imagination, so I replaced every dialogue attribution with a verb. My characters growled, barked, and hissed like a pack of zoo animals, but never “said” a word. While verbs offer a lavish palette of vocal expression, overuse dilutes their power. “Said” functions like the word “the”, an essential and unobtrusive part of sentence mechanics. Readers don’t even notice it as they follow a conversation. Upon this invisible foundation, verbs stand out bold and clear when the speakers truly have reason to grumble, shout, whisper. Use attribution verbs as “seasoning” when the scene calls for more dramatic forms of expression.

Treat adverbs with even greater restraint. On occasion, it’s all right for a character to say something softly or slowly (“hold me closer, tiny dancer…” oops, got the wrong keyboard under my fingers for that one!). But adverbs, in attribution or anywhere else in writing, can indicate a weak verb choice. Instead of describing a character’s emotion through adverbs, pair dialogue with behavior and paint a vivid picture for the reader:

“Sure,” he said cheerfully. / “Sure,” he said with a grin.

“Sure,” he said angrily. / “Sure.” He slammed the door shut.

“Sure,” he said nervously. / “Sure,” he said, fiddling with his cuffs and not meeting her eyes.

We’ll discuss handling of adverbs in more detail next week, when we discuss prose style.

Inner Monologue

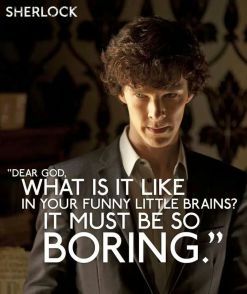

Not your most brilliant deduction, Sherlock: getting inside those “funny little brains” is exactly why many people read fiction.

In an age where we carry streaming video in our pockets, why does anyone still read novels? Perhaps it’s the opportunity to hear character’s thoughts. With a few exceptions, inner monologue is still unique to written fiction. It’s a terrific storytelling device, offering insight into motivations and opinions characters they might not share in dialogue. It can be an aside for humorous commentary, or highlight conflict between a character’s thoughts and actions. Employing it with success, however, can be a little tricky:

Don’t overdo it. Include only a few lines at a time. If you find the story demands a lot of inner monologue, perhaps the novel would fare better with a first-person perspective.

Don’t play “musical minds”! Reveal only one character’s thoughts per scene/chapter (in correlation with perspective).

Don’t use inner monologue for forced exposition.

Drafting Dialogue

Dialogue can even help get your rough draft on paper. If you’re stuck on a scene, type up the essential exchanges like a script, with no supporting text, and see what unfolds. Often it reveals the heart of the scene, and makes it easier to fill in the rest. If the dialogue itself it giving you trouble, change the setting and see how it changes the conversation. You can even try changing the players involved. Just think of how a character’s confession of guilt would differ if delivered to his best friend, his sister, his lover, his local news anchor, his therapist, or his dog.

When you first write a scene, let the dialogue flow. Capture everything you hear the characters saying, without stifling them or cutting them short. Listen to their voices. Dialogue is like a rosebush: let it grow lush and full before pruning it to topiary perfection. At editing time, read the dialogue aloud. Taste the words and hear the cadence of speech. If it sounds good in your ears, you’re on your way to crafting dynamic dialogue!

April 28, 2016

How to Write a Novel, Part 4: Opening Lines and First Chapters

Years ago, I read a fantasy novel my sister recommended. Although I wasn’t a huge fan of the genre, I thought it would be fun for us to follow a series together, so I tackled the dense paperback. The first few pages didn’t grip me. Neither did the first few chapters.

“It starts slow, but gets really good once the monsters attack the village,” my sister assured me. I kept going, chapter after tedious chapter, waiting for the dang monsters to make their promised appearance and gnaw the complacent characters into doing something interesting. At last, the fanged horde arrived…a quarter of the way through the 700+ page book.

In fairness to my sister, the story did prove enjoyable after that point. But if she hadn’t insisted, I would have set book aside after chapter two. I didn’t have patience to slog through a novella’s worth of drivel to get to the good stuff. In this case, however, the reward went beyond sharing book gossip with my sister. That ponderous first installment also taught me a valuable lesson in storycraft. Ever since, I’ve tried to begin my own stories right at the inciting action. No matter how brilliant your novel’s concept, characters, or plot, a poor opening can dissuade readers before they ever get into the story. In an era of notoriously short attention spans, an author must capture the reader’s interest from the get-go.

First Lines

The first opportunity to arrest a reader’s attention is the story’s opening line. That first sentence is a portal into the story’s world. It can hook the reader right away and keep them turning pages. For writers, it serves as a springboard for the rest of the story. A sharp opening might:

Inspire questions.

Immerse the reader in a sensory experience.

Foreshadow the remainder of chapter (or entire book).

Establish narrative voice/tone.

Imply intriguing information about the story

Good first lines can deliver a lot of information without seeming to do so, provoking subconscious curiosity. Take a look at the first line of One Hundred Years of Solitude:

“Many years later, as he faced the firing squad, Colonel Aureliano Buendía was to remember that distant afternoon when his father took him to discover ice.”

Immediately, we know some misfortune must befall the Colonel for him to wind up in front of a firing squad. There’s surely an exciting story there! What does he mean, “discover ice”? Any why is he thinking of it now, looking down the business end of a rifle? With just one line, Marquez makes us hungry to hear his tale.

Strong voices also shine in opening lines. Like a Santana guitar solo, we know right away to whom we’re listening, and we want to hear more. Catcher in the Rye displays this technique with virtuosity. The first words we hear from Holden Caulfield are snarky, disaffected, and entrancing. His distinct voice provides an instant, intimate gateway into the story:

“If you really want to hear about it, the first thing you’ll probably want to know is where I was born, and what my lousy childhood was like, and how my parents were occupied and all before they had me, and all that David Copperfield kind of crap, but I don’t feel like going into it, if you want to know the truth.”

A novel’s first line can also set tone. One of my favorite novel openers comes from William Gibson’s Neuromancer:

“The sky above the port was the color of television, tuned to a dead channel.”

There’s a haiku quality to this line. It goes beyond describing a grey sky and evokes something deeper about the technology-saturated society where the story takes place. The color of television is a highly modern analogy. A dead channel conjures static, a sense of being disconnected or unplugged. All these subtleties reflect the book’s larger themes.

Opening lines are an art unto themselves. Stephen King expounded upon their importance in an excellent piece The Atlantic ran in 2013. According to King, “an opening line should invite the reader to begin the story. It should say: Listen. Come in here. You want to know about this.”

First Chapters

If the opening line is the bait, the first chapter is the hook. That piece of story bears a lot of responsibility. It has the unenviable task of delivering on all the first line’s seductive promises. From a functional perspective, the first chapter should:

Introduce the protagonist

Identify the protagonist’s problem/goal

Introduce (or at least reference) the antagonist/obstacles

Set tone/theme

Establish setting

Create conflict

Set reader expectations

Chapter one provides the foundation of the entire story to come. Most of them reflect one of two common structures:

The three-act opening. We start with a glimpse of the central character’s everyday life, then something disrupts the status quo and drives the character to action, kicking off the narrative. Blue Karma begins this way. We meet Logan waiting in line for his family’s water ration, which introduces us to his water-starved world. When he learns rations will again fall short, he decides to try something drastic to get more water. Trouble—and the rest of the story—ensures.

In medias res. This Latin phrase, meaning “in the middle of things,” is shorthand for plunking the reader down amidst an already-unfolding crisis. For example, Lord of the Flies opens with boys shipwrecked on a beach. Golding could have begun on the boat before the storm, but how much of that would have been germane to the story? It’s bolder and more exciting to start among the wreckage. Well-executed, in medias res can draw readers into a scene and keep them there.

Prologues and Cons

But wait! you might think. Not all books begin with chapter one. What about prologues? Prologues are tricky little hobgoblins. Employed with skill, they can engage the reader while providing critical information.

One effective use is “framing” the larger narrative with a separate-but-related incident. Ever read a mystery that starts with a prologue from the murderer’s or victim’s point of view? It gives the readers an intriguing glimpse of the criminal they, and the investigator whom they accompany, will pursue for the rest of the book. In a thriller, the prologue might show villains plotting against a target or a scientist losing control of her volatile creation before the protagonist begins tackling the problem in chapter one. This device advances the narrative in a more interesting way than, say, having a side character tell the reader what happened.

Prologues are also useful for witnessing a past incident that’s crucial to the story’s start. I began Blue Karma with a prologue because the scene takes place a year or two before the main narrative. I felt that such a temporal leap between chapters one and two would disorient the reader. Instead, I set that scene apart in the prologue.

But prologues can also sabotage your novel. They can enable lazy storycraft, offering shortcuts for shoddy plot structure or serving as landfills for unincorporated backstory. A dull, rambling prologue can cause readers to put book the aside before the story truly begins. If you’re wondering whether a prologue is the right device for your novel, ask yourself these questions:

A honed opening line, followed by a dynamic first chapter, can entrance readers from the start and keep them turning pages.