Geraldine DeRuiter's Blog, page 5

February 9, 2021

I Spent a Year Reading Women Authors.

TW: This post makes brief, passing mention to accounts of rape and assault in some of the books I read.

I decided to spend 2020 reading only women authors. It shouldn’t have been a revolutionary act, but somehow, by the end, it started to feel like one. There’s a clear gender bias in publishing (male authors are published more often than women, have their books submitted for more awards, and are highlighted in publications more frequently). When much of the world is already written by men – not just books, but history itself – it felt like this was some small way in which I could try to tip the scales.

It wasn’t a strict rule, nothing set in stone, and I even made the occasional exception (including my friend Mike’s fantastic graphic novel, Flamer, which he published last summer). My goal for the year wasn’t a limitation or a constraint, but a focus – to seek out women writers in a way I hadn’t before.

Beyond this commonality, there was no shared theme between the books I read, and I kept no comprehensive list – it felt like doing so might somehow rob me of the magic of it, might end up imposing order when all I wanted to do was meander. I went from non-fiction memoirs to young adult to literary fiction. I loved a few, hated none, left no book unfinished. And even though not every story was joyous, I found that there was something beautiful in them, in surrounding myself with the words of women. A patchwork quilt of experiences, woven together by this facet of our identity.

Not once was I irritated with how women were portrayed, and while I was often angered or upset by how the world treated them, it never felt gratuitous. Their pain was real, and it was theirs, and they shared it with me. There was something strangely comforting in that – these complex and imperfect women existing in a vicious and stupid and unforgiving world, and knowing that none of us were alone. It had been a long time since I’d found a friend in a book. I thought I’d outgrown it. But maybe you never do.

And god, they were so gloriously, beautifully human. They had acne and mastectomies and unpleasant voices and long noses and were too tall or too fat. They were irritable and unkind and wore the same sweatshirt too many days in a row and drank too much or not at all. They befriended dragons and defeated monsters and fell in love and were hurt or raped or murdered and these things were significant not because of the men they were related to or the ones they loved but because it happened to them. These stories belonged to women. Both the characters and the authors.

(There were zero descriptions of pert breasts or erect nipples.)

When the new year started, I picked up a book by a male author in a genre I hope to one day write in. I had heard of his work, and this latest novel had gotten rave reviews.

There were things that I took issue with, and somehow I thought these things were just my problem. The teenager in a sexual relationship with someone seven years older than her; the classic depiction of a beautiful woman who ends up being a betrayer; the woman who is fragile because of her mental illness. The book and the author were so beloved that I figured it was my inability to just be cool, another example of me being a humorless bitch because that’s what feminism does to you.

It was like all the lessons of the last year just vanished.

About halfway through the book, seemingly out of nowhere, there was a graphic and horrific rape scene. I read it late at night, and found I couldn’t sleep afterwards. The act of violence was between two men. I don’t know if that makes it less of a problem. I find sexual violence against women is terrifying for a lot of women to read. And sexual violence against men is also terrifying for a lot of women to read.

Because it’s sexual violence. And a lot of us have personally experienced that.

Men have a right to tell those stories, too, of course. We all do. But we have to do it responsibly. Especially if you wield a bigger audience, and you come to the conversation with a great deal of privilege, as men so often do.

I put down the book. Over the next few days, I went through a strange mental exercise that I’ve been through before – wondering what I did wrong, wondering if I should have been more careful (should I have read more reviews? Looked up triggers for this book?), wondering again if the problem was with me. I felt betrayed, somehow.

I read a few more chapters, wondering if the assault would be addressed, if the character’s own trauma would be discussed (it wasn’t, except his attacker threatening to do it again). From a plot perspective, it wasn’t even relevant. I tried to figure out the purpose it served, other than to be homophobic and terrifying. I read spoilers for the book, hoping someone would make sense of the scene. No one did, or could. In the middle of the glowing reviews, a few people commented on how horrific it was, how blindsided they were, how it was never talked about again.

I’ve read stories of rape last year, written by women, some of which were autobiographical. It felt like they were holding my hand and leading me through the pain, and then out of it. Their assaults were not the heart of their story.

They were the heart of the story.

I told myself to keep going – that I could get through this damn book. I am a completist, after all. It was words on the page. Then I got to another chapter, where a woman with a disability was being tortured.

And I decided that I was done.

But enough about that book. Let’s not shift the spotlight away from where it should be. That happens enough already. I don’t need to do it in this post, as well.

Instead, let’s go back to the books I loved last year.

It’s still far from a perfect collection. I had hoped to read more poetry and more plays, I wish that I had sought out more women authors who remain underrepresented in publishing: trans women and indigenous women, and women with disabilities. But I remind myself that nothing ended when the clock hit midnight. My reading list is a work in progress, something malleable and alive. It goes on and on. And I keep adding to it, every damn day. There are some men on the list, of course.

And a hell of a lot of women.

Here are some of my favorites from last year:

Clap When You Land by Elizabeth Acevedo (TW sexual assault, plane crashes, death. This is YA, and it’s handled very delicately but still.) A story about two sisters – one in the Dominican Republic, one in New York, who deal with the aftermath of their father’s death, and discover that he was living a dual life, with, yes, two families in two different countries. It’s heartbreaking but ultimately beautiful and redemptive and it’s written in verse.

Circe by Madeline Miller (TW sexual assault, violence, murder. Honestly, this one was the easiest to handle for some reason.) Okay, it’s not like you haven’t heard of this one, right? It was on everyone’s list. But, damn. It’s so, so good. Told from the perspective of Homer’s witch, she is given life and agency, and it’ll leave you feeling like everyone who got turned into a pig maybe had it coming.

Fleishman is In Trouble by Taffy Brodesser-Akner (TW, mental breakdowns, divorce, child bullying and abandonment) Admittedly, I slept on this one, too, and was probably the last person I knew who read it. But it’s such a fantastic exploration of a marriage (and people) falling apart, done with precision and vivid writing, and it unravels like a mystery.

An Unkindness of Ghosts by Rivers Solomon (TW sexual assault – alluded to, violence, racism, child endangerment and murder). An afro-futuristic tale of a genderqueer doctor/scientist struggling against a racist, oppressive system on a spaceship. Simply one of the most unique and captivating books I’ve read. It’s a tough read, emotionally, but so, so good, and Rivers Solomon’s voice is unlike anyone else’s out there.

A Heart In the Body in the World by Deb Caletti (TW gun violence, murder, stalking) A young woman tries to grapple with an act of violence by (literally) running across the country. It’s so sad, but also redemptive and sweet (it takes place partially in Seattle, and the family at the heart of it is Italian, which hit close for me for a lot of reasons.)

My To Be Read (TBR) list includes Culture Warlords by Talia Lavin (where she goes undercover and infiltrates white supremacist groups online), Wow, No Thank You – Samantha Irby’s book of essays (another book I’ve been sleeping on), and Mikki Kendall’s Hood Feminism. I also just bought Madeline Miller’s The Song of Achilles, and I’m planning on picking up Rumaan Alam’s Leave the World Behind. If there is something you want to recommend, please do so in the comments. (My book buying attitude over the last few years has basically been this.)

February 1, 2021

To Everyone Traveling Right Now: Stop It.

It’s February.

This was the month that Seattle started to shut down, a year ago. It’s the last month that I ate inside a restaurant. We were scheduled to go to Italy that March, just as Covid was starting to take hold there. Those few weeks before we were set to leave were fraught – were we cancelling out of paranoia? Would we look back and think, “Well, that was silly. It all turned out to be nothing?”

It didn’t, of course. We cancelled Italy along with a half dozen other trips I no longer remember now.

In some ways, I suppose it’s not that unusual – staying at home for a year. But I hadn’t done it in well over a decade. It’s part of how Rand and I engineered our lives: no kids, no pets, only a few neglected houseplants that I’m probably overwatering as of late, because, well – I’m around. Travel is simply what we do. Or rather, it’s what we did. At the apex of it, we’d spend a third of the year on the road.

I have been home for a year. But others in that world I used to inhabit have not. I see Instagram photos of someone proudly standing at a podium, receiving a travel writing award for glowing coverage of a state where the governor has adamantly refused to take any preventative measures to curb the spread of the virus (the governor is in the photo, maskless, applauding him). They never once mention that they’re in a Covid hotspot, with one of the highest death rates in the country.

In another travel community thread, a woman said that because she’s tested negative, she had every right to keep traveling. That she’s “not endangering anyone.” Someone tried to tell her that negative tests do not mean that one is immune. That you can still be a vector for spreading a disease. The woman doubled down. She’s not going to let Covid stop her, she said – as though she was somehow Joan of Arc facing the fire.

But there’s no nobility in it. As my friend Naomi notes, it comes down to the same thing as always – the concept encapsulated in that old Buzzfeed News Headline: “I Don’t Know How to Tell You That You Should Care About Other People.”

The proclamation that something is safe rattles her.

“Safe for who, exactly?” she asks.

I see snapshots from airports, heading to the few countries that will still let us in, or to Hawaii, because “People forget it’s part of America!” They ignore the fact that schools in Hawaii remain closed. That my friends with family on the islands are terrified for their well-being, because of the influx of tourists. Yes, there is a lot of shit that you can still do right now. You can still go to Disneyworld. You can eat indoors. You can attend a rally mashed up next to people who think that pandemics are fake and baby-eating lizard people are real. But that doesn’t mean that you should.

“These places are struggling,” I hear people say. “They need our money.”

I take a deep breath to stop the blood vessels in my eyes from bursting with rage.

Look, Hilton Hotels and United Airlines and the other titans of travel and hospitality? They are going to be just fine. They’re not going to collapse because you didn’t buy a $99/day super saver weekend getaway to Las Vegas. You are not going to single-handedly save the travel industry with your money. You might kill someone who’s working the front desk, though.

“BUT WHAT ABOUT THE SMALL INDIE HOTELS AND RESTAURANTS. I MUST HELP THEM.”

Buy a goddamn gift card. Or, hey, support your local restaurants with take-out, or order something from a local independent shop. They need you, too. Or if this is such a charitable effort on your part, why not just send them money? You can donate to organizations that are helping small businesses survive during this time (OH LOOK, THE U.S. CHAMBER OF COMMERCE HAS A WHOLE GODDAMN LIST.)

*unclenches jaw and fists*

“BUT I HAVE DONE EVERYTHING RIGHT AND I SHOULD GET TO SAFELY HAVE A GETAWAY.”

Sigh. To refute this, I’m just going to borrow some phrases of rage from my friend Pam.

“To be clear, I understand there are safe scenarios — drive to a cabin! Bring all your groceries! Okay! And that the burden on close families is hard! Wear a mask, quarantine for two weeks upon arrival, do the same when you get home! THAT is doing everything right. Also, SHUT UP. Your performative “traveling safely” makes it look like it’s okay for any clown to “travel safely” and we live in a world of science deniers. SHUT UP. Take your trip and SHUT UP.”

Look, there’s a lot of privilege wrapped up in being a travel writer. Some of it is inherent. It requires a (semi-expendable) income, flexibility with work, valid passports, and bodies that are easily moved from one spot to another. But there’s an obligation in it, too. Travel is not a singular, solitary action. It is not something that exists in a vacuum. We interact with our environments, with the community and cultures that we find ourselves in. If we travel during a pandemic, we aren’t simply assuming risk for ourselves. We’re endangering everyone around us. We could spread a disease to fellow passengers, to airline and airport and hospitality employees. We could eventually be hospitalized in healthcare system that is unprepared for an influx of travelers, diverting resources from locals.

And if we are travel writers, we are leading by example. If we travel, we risk spreading the misconception that all travel is safe. As Pam notes, the world is full of science deniers. They do not see the differences between our actions and theirs. They do not understand the precautions that we’ve taken. They simply see it as an endorsement – from travel professionals – that it is okay to see the world right now.

And it’s not.

Look, this sucks. Being a travel writer who doesn’t travel messes with your sense of self. I miss my family. I miss my friends. I miss my job.

I even miss the haze of landing in Europe first thing in the morning after a trans-Atlantic flight and having pancakes with this barely-conscious cutie.

But the thing, pandemics aren’t supposed to be fun. Global catastrophes aren’t supposed to be convenient, or enjoyable. They turn your world upside down, by design. It’s fucking awful. People are dying. I haven’t hugged my mom in a year. My nephew doesn’t know me. I am literally a stranger to him. My aunt and uncle are in their 80s, and my husband is terrified – absolutely terrified – that something will happen to them and we won’t get to say goodbye, in the same way we didn’t get to say goodbye to his grandmother.

There’s this longing for things to go back to how they were – I feel it so desperately, in my bones, while at the same realizing that it doesn’t get to happen for so many people. I think of everyone I know who has lost someone to Covid, and about how once vaccines are available and the world opens back up, their lives doesn’t go back to how they were. If you stretch an elastic band far enough, sometimes it stays like that, stretched out and brittle. Sometimes it just breaks.

I miss ferry rides. I miss the feel of smushing my face next to my beloved’s while we breath in sea air.

I want this to be over. And it fucking would be, if people just stayed at home. I’m asking you to do that, not just for yourself but for all of us. And if you decide to ignore not just your own well being, but everyone else’s … well, at least have the decency to be quiet about it.

December 31, 2020

The Only Thing I Want to Remember About 2020 Is Hilaria Baldwin.

It is December 31st, the last day of 2020 – a year that has been supersaturated with so much shit and grief that it’s almost bordered the absurd. I have been to a Zoom wedding and a Zoom baby shower and a Zoom funeral, experiencing the spectrum of human existence in halting pixilation. I try to remember what it feels like to hug my mother, as she sits eight feet away from me in the frigid cold of my backyard, shouting that I should have a merry Christmas. (I did not, but it wasn’t for want of trying.)

I wonder what the universe will try to squeeze in at the end of this miserable year, if a massive fault line will be discovered right under my home, or a portal to hell found in my toilet. I am glued to my phone, to endless headlines of awful, and I read them aloud to my husband like the newsreel of some parallel universe where everything has gone to shit.

In the midst of all of this, one story has floated up to the top, a bit of inconsequential flotsam in a sea of miserable news, something for me to cling to in this storm of a year.

“Have you seen the Hilaria Baldwin story?” I ask him. I might, as these words escape my lips, be frothing at the mouth. My eyes are wide, and I’m feeling a sort of giddy frenzy at this, the crumbling of a curated social media facade. My husband, to his credit, does not look at my wild expression and dismiss me as a madwoman. He does not whisper “My love, you are shouting,” as he sometimes does because I often am. Instead, he looks at me with the patience that you would expect from someone who has made a relationship work for twenty years, where you pretend very much to care about the things your partner cares about, even if it’s only as long as it will take for them to explain that thing to you.

“Who is she?” he asks. This question is a gift.

Most people know by now, thanks to the osmosis of social media, but my husband did not, so I describe her as though I am unmasking a Shakespearean villain. I tell him how she is from Boston, how she put on a fake Spanish accent and professed to be from Mallorca. I describe the time she pretended to forget the English word for cucumber on television. How she gave her children Spanish names. She was a social media influencer/yoga instructor whose prided herself on authenticity, I say. I liken it to Marcus Brutus’ betrayal of Caesar.

My husband does not ask (for he is an obliging soul who has to cohabitate a space with his wife during a pandemic), but so many others have: why on earth do we care? Why am I, a reasonably intelligent person who didn’t even know that Alec Baldwin was remarried, so obsessed with this story when there are so many bigger things to worry about?

And perhaps that’s where the appeal lies – in the absurdity, the absolute madcap set-up, the fact that it has nothing to do with death or illness or pandemics. In a world that has become a dystopian apocalypse film, this storyline is a sit-com plot gone awry. When did Alec find out? Did she tell him at some point? Did she keep up the accent all the time? Like, all the time? What about her family? Was anyone, at any point, like, “Hey, Hillary, you know we’re from Massachusetts, right?”

Was there an evening where she was double-booked as both Hilaria and Hillary, and she had to scamper from one event to the other?

I NEED TO KNOW.

I mean, look: it’s been a rough goddamn year. So many of us are barely holding it together. But as we change from our day pajamas to our night pajamas, brushing crumbs from our breasts as we silently judges ourselves for being shadows of who we once were, we can find comfort in this: we never spent a decade of our life creating an elaborate, culturally-appropriating alter-ego which then became our undoing.

I am wearing pajamas. It is after noon. Hilaria Baldwin’s story is fading from the headlines, as stories do – I once again find myself reading about Americans starving and dying and the government failing to pass stimulus packages. But in this year of awfulness, watching her story play out like a pop culture Greek tragedy has been a welcome distraction. One I want to hold on to for just a little while longer.

December 24, 2020

Merry Christmas. It’s Not Too Late to Stay Home.

(Above – every holiday with my family ends with people dancing in the kitchen. I don’t know why. This was a few years ago. Yes, there is box wine. And yes, my mother, at left, is a knock-out.)

It’s Christmas Eve, and I am at home. I can’t remember the last time this has been true. It’s been more than a decade, and probably closer to two. I’m usually down in California at this time of year, listening to the seasonal screams of my family while opening incomprehensible gifts from my mother. But nothing this year has been normal, and the holidays are no exception.

Recently, a dear friend told me that he was going to visit his family for the holidays. He’d been isolating, but they hadn’t been nearly as careful. They were planning an indoor dinner, and he was going to attend. There was an aging relative he wanted to see. Keeping my voice as steady as I could, I told him that it was his decision, but I didn’t think it was a wise one.

“It might be our last holiday together,” he said. I was only half-paying attention. Mostly, I was trying not to sputter like a coffee pot. The force of my own anger blindsided me. This holiday season has been the busiest stretch of travel since the pandemic began. Airports are packed with people.

Rand and I flying to see family for the holidays last year.

What if this is my last holiday with them? I’ve heard this refrain countless times this season – every time someone flouts CDC recommendations in order to visit family members. It’s a hard sell for me. I never spent a single holiday with my father, nor a birthday that I know of (if they did happen, I was too small to remember them). The closest we ever came is that one year, around 2005, that I went to Oktoberfest with him and my mother. (I realize that this is a very niche piece of travel advice, especially given that my father has been dead for four years, but still I offer it to you: do not go to Oktoberfest with my parents.) I’ve written a lot about my dad – how I struggled to accept him within the confines of who he was, the scarcity of the time we spent together. I have memories of him, and I pull them out on occasion when I want to sit in that space, in the cold, efficient, reliable austerity of who he was. I know that memory is a malleable thing, so I try not to do this often. What I remember of him sits on periphery of my mind, because I know if I look at it head on, it’ll change, or worse still, vanish altogether.

It’s strange to look like someone. To just to go around in the world with features you got from them.

The last time I saw him was years ago in a hospital room in Germany. It was not a holiday. It was not anyone’s birthday. I don’t even remember the exact date – I only know that I wondered if it would be the last time I saw him, because I wondered that every time I saw him. That was the nature of our relationship – so much time spanned between our visits that it was completely reasonable to assume that one of us might expire before we saw the other again. Despite this, I clearly didn’t say anything memorable or poignant. Those moments are impossible to engineer. Even when you try to make a goodbye meaningful, the last time you see someone is never, ever going to be enough. Even when you expect it or plan for it or know its coming, you’re never really ready to lose someone.

I remember the last words my dad said to me. They were wholly inconsequential.

All this is to say that when you tell me you need to have another holiday with your relative, when that act might actually be the thing that kills them or you or someone else, I am unpersuaded and honestly, a little hurt. When you say it is your decision, and that you are accepting the risk for yourself, I want to draw you a diagram of how diseases spread and then I want to roll up that diagram and smack you with it. When you argue it might be your last Christmas together, I wonder, truly, what makes you so goddamn special. For those of us who have already had our last Christmas with the people we love, or never had one at all, these words sting in a way I can’t describe.

My brother and Dad at Christmas, before I was born.

I went a lifetime without seeing my father for the holidays, and I can tell you: you will survive it. But losing someone when they are far away, and being unable to go to their funeral is a far worse thing, and one that I don’t recommend. No one deserves that. Not you, not your loved ones, and not some random stranger who sat too close to you on a flight or a bus. I want you to do everything you can to avoid that.

I know you’re fed up. We’ve all given up so much of our “before” lives in this pandemic, already. To have this taken from us, too – knowing that we might not get another one with our families, is enough to make you rebel. No, no, fuck this. I’m hopping on a plane, I’m getting in the car, I’m seeing people, because that is, like, the fundamental thing that makes us human.

My aunt and I laughing about something at Christmas last year. I can’t remember why.

It feels so strange for me to tell you not to do this. Me, who clings to the people in my life like a bead of water on the hood of a car – the kind that you wipe away with your finger only to have it instantly reappear. I want the world to return to normal just as much as you do. When this pandemic ends, I promise we will celebrate every single holiday and celebration we missed – possibly all at once. We will run in the streets and scream and dance and hug strangers. It will be Christmas and New Year’s and Halloween and your birthday and mine. It will be every special day you ever missed. It will be every holiday I never had with my father.

I want us all to be there, together. And for that to happen, we have to stay home this year, and have a quiet, lonely Christmas. With any luck, it’ll be the last one.

November 24, 2020

Happy Thanksgiving. Stay the F*ck Home.

Ah, Thanksgiving! A holiday we celebrate by playing a game with our families that I like to call “And that’s how you’ve decided to live your life then?” Like Pictionary, you just keep at it until someone cries.

Or – hear me out – you could just stay home for the holidays, closing the curtains and doing your best impression of tranquilized zoo animal. because the CDC has actually said that you do not need to see your family this holiday season! You don’t need to host anyone. Are you hearing this? A governmental organization dedicated to making sure people don’t die is telling you to sit on your ass and have a Nic Cage marathon instead of listening to your family members recall that one time you peed your pants in the grocery store at the ripe old age of 9. THIS IS A GIFT, PEOPLE.

Call your family (if you haven’t already) and tell them you aren’t coming over. (Sorry!) You can tell your friends that – ugh – you aren’t hosting. Yeah, I know it’s last minute. And they’re going to be so disappointed. *Insert shrug.* But this is for everyone’s safety, and also, you’ve never seen National Treasure.

Some of you might still be contemplating hopping on a plane or jumping into your car and dipping your hands in a big old communal pot of stuffing. Millions of people are traveling even though the CDC has asked us not to, and I am going to lovingly scream that you not do that (through a mask, because guess what? Screaming is dangerous.) If you want, you can go over to your loved ones house and wave at them from a distance of at least six feet.

YES, I KNOW THAT SOUNDS AWFUL AND STUPID. WE’RE TRYING TO SURVIVE A PANDEMIC WITHOUT ANY FEDERAL OVERSIGHT OR SUPPORT. IT IS DESIGNED TO BE AWFUL AND STUPID.

We’ve been at this shit since early March. The last time I hugged my mother was February. I haven’t seen my nephews in a year. The little one now walks and talks. I missed all his round-faced, dimpled-elbow babyhood. Last month my husband’s grandmother died, and her final months were spent away from her family, wearing a mask, absolutely done with all of this. We had her memorial over Zoom.

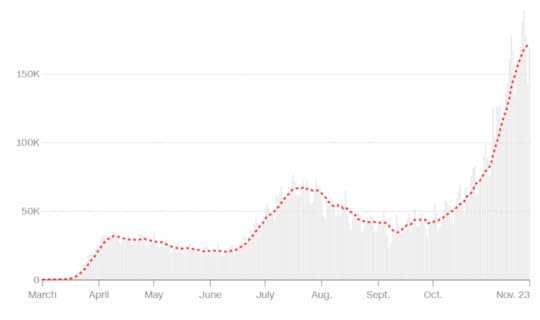

But just because we’ve had all that we can take doesn’t mean this is over. El Paso Texas just ran out of morgue space. Reno, NV is planning on turning a parking garage into a Covid unit. Mississippi has essentially run out of ICU beds. We had 180,000 new cases of Covid on Friday which is basically the population of Salt Lake City, Utah, and that’s just people we know about. The chart of new infections looks like something someone in a marketing meeting would pull up because they were gunning for a raise.

A quarter of a million people are dead, and the current administration is acting like a bunch of high school seniors with two months of school left. They do not give a fuck, because pretty soon they’re going to be out of here and taking a permanent gap year in a country without extradition treaties. They are just leaving us to fend for ourselves during a pandemic. So I am asking you, please, please, please stay home and fend for yourself during this pandemic.

I know that many of you are thinking that this might be your last holiday season with your relatives. I get that. IT FUCKING SUCKS. You are talking to someone who never spent a single holiday or special occasion or birthday with her own dad, and who didn’t even get to go to his funeral. It is not great, but also I can assure you, it’s not the end of the world. I have a lot of great memories that don’t happen to fall on specific dates.

And if you insist on seeing your relatives because you’re worried this holiday season might be their last, you might actually ensure that this holiday season is their last.

You may think that traveling is simply your decision and this is about your health and your autonomy but it is not. You are a vector. You are someone who could infect dozens of people around you without even knowing it. Who could endanger cab drivers and essential workers and healthcare professionals and your entire family.

One of the things that we agreed to when we decided to live in a society is that we take care of one another. It’s like the ONLY thing that old dead philosophers agree on – if you decide to live in a community, you don’t get to kill your neighbors or your grandma, and you don’t get to break that rule because it’s the fourth Thursday in November. For some damn reason individual liberty in America has become synonymous with “I get to endanger and kill anyone I want” and we need to rethink that immediately.

I promise, when this is over, we’ll celebrate every single special day we missed, possibly simultaneously. I’m going to stand in the middle of my street pelting people with Halloween candy while screaming Mariah Carey’s “All I Want For Christmas Is You,” regardless of what time of year it is. But that cannot happen now.

My career literally consisted of making out with my husband on planes. I am just as determined to get back to normal as you are

That doesn’t mean you shouldn’t be angry – damn it, you should be pissed. We have been left in the goddamn lurch by the people elected to protect us. We are the only country where things are this bad, and it’s because our leadership literally doesn’t care if we live or die. That should make you incensed. We should be fighting against that every single day.

That is where our rage should lie – not at the ordinances and the rules and the scientists and doctors trying to keep us safe, but at the government who took our safety and holidays and our loved ones from us in the first place. The ones who didn’t take this issue seriously when they could have stopped it, and who have access to better health care than we will ever get.

I am not asking you to not be angry. I am just asking you to be angry at home. Sit down in the butt groove on the couch that you have so bravely been working on for the last nine months. Turn on the television. And if anyone tries to guilt you for not showing up this holiday season, remind yourself that this selfless act is the embodiment of your love for them. You, sitting alone, missing them with all your heart.

November 10, 2020

I Do Not Have The Emotional Bandwidth For A Coup Right Now.

Dear GOP,

Look, here’s the thing: I’ve got a lot going on right now.

I mean, not technically. Technically, I walk around the house nursing a stash of Halloween candy while occasionally changing from “day pajamas” to “night pajamas” (the sartorial differences are subtle but significant). Today I cried while watching a tiktok video, a medium which I only vaguely grasp. I’m like Miss Havisham if she were dumped on a weekday when she thought she maybe had the flu and decided to just stay in bed.

What I mean is, I have a lot going on, emotionally.

It’s just been a really long hoax pandemic, you know? With a lot of people getting hoax-sick and hoax-dying, including the loved ones of my friends. And this hoax lockdown has led to what my therapist refers to as “very real depression” (but honestly, probably a hoax). And then my husband’s grandmother died last month but so many other people died (hoaxly, I should add) that we can’t inter her yet. We had to have her memorial over Zoom (cough, cough, hoax, cough), because what’s the point in grieving without someone repeatedly shouting “YOU NEED TO UNMUTE YOURSELF” in the background?

What I mean to say is – I don’t think anyone has the emotional bandwidth for this coup.

Look, I get it. Despite numerous attempts to burn ballots, purge voting rolls, intimidate voters, and even destroy the U.S. postal service as a means of decimating the mail-in vote (seriously, gents, Bravo, that was some unforeseen shit), Trump still lost the election. I mean, that’s just embarrassing. Clearly, the only way to save face is for the government – in a sudden, striking, potentially violent move – to flagrantly overthrow the will of the people and crumble what is left of our fragile democracy by declaring that Trump should still be president. Who among us has not lost a game of Pictionary and thought, “I will destroy all democratic and governmental norms and create a constitutional crisis that will have devastating ramifications for generations?” ALL OF US, THAT’S WHO.

But listen, my dear aspiring totalitarian dipshits: I am so, so tired. I’m emotionally spent, and I can’t give this blatant violation of all of our constitutional rights the attention it deserves. You deserve pithy signs! And chants! Honestly the best thing I could come up with is “TIRED OF BEING COUP-ED UP” and I don’t even know that that means. I just want to go back to my usual life of never leaving my house since February and watching my mental health dissolve like an Alka-Seltzer in the rain. Honestly, this is just not a good time for me, and next week is looking terrible, too, and then we’re in the holiday season, and you know how that gets. It makes you just want to shout “FUCK CHRISTMAS!”

Plus, think of how much better a coup will be when we have hope again! Rescheduling for like, year two of a Biden administration will hit way harder.

Look, the point is, I think you are just going to have to accept the terrifying truth – that Americans just democratically elected a new leader who won both the electoral college and the popular vote, while you will (probably) maintain power in the Senate. I know, I know – it’s scary. But it’ll be okay. Really. If it’s any solace, we can remember all of those Republican Presidents who took office with fewer people voting for them. And hey, you still have gerrymandering and voter suppression! That’ll ease the sting of this injustice.

Anyway, I hope you’ll consider letting this election slide by a weensy margin of 76 electoral votes and 7 million legally cast ballots. Or maybe delay this whole coup until later? If you’re going to overthrown a democratically-elected leader, it’s not like it has to happen now, right? Why not give us all some time to recharge and give this thing our full attention? Because honestly, you deserve that. Get some rest. You’re looking a little hoax-feverish. And, holy hell, am I tired.

October 31, 2020

My Grief Chyron Is Really Long Right Now.

Grief is weird when the world is normal. Everyone just goes about with their day, walking around, and sometimes the sun even has to audacity to shine, and when you are grieving, all of it feels like an insult. I told Rand once that I wished that human beings had chyrons – those little scrolling bars that run underneath your photo like you see on the news – and you could let people know what was going on in your life. It could be subtle things, like, “Please don’t flip me off in traffic, I just got laid off” or “I’m in the middle of a divorce, please don’t judge me for crying on the subway.” Easy, helpful messages like that.

But now the world isn’t normal, and I don’t know if that helps with grief or not.

Rand’s grandmother died two weeks ago. I think it was two weeks ago. It might have been three weeks ago, or maybe yesterday, or last month. Time is infinitely malleable when your heart hurts and you aren’t allowed to go anywhere. It’s always Tuesday, and it’s always 3pm, and then it’s midnight, and we aren’t sleeping, and how has another week passed, and my god, it’s already almost November but simultaneously still March.

I haven’t written about Rand’s grandmother because … well, it feels like starting another fire when there’s already a blaze I can’t control. I was just barely dealing with everything, just like everyone else. There’s no need to add to the pyre.

Besides, it’s hard to know where to place this grief. She wasn’t my grandmother. She wasn’t even remotely like my grandmother, who was utterly domestic and spent her life in the kitchen, because her love language was feeding people. Rand’s grandmother went to Broadway shows and museums and the running gag about what she made for dinner was “reservations.”

Honestly, what an absolute legend.

And while my grandmother adored me to a degree that became part of family lore, Rand’s grandmother and I had a more complicated relationship. His grandmother always let me know what she thought of me. It was not always good. But sometimes it was. Either way, I knew where I stood – there was no ambiguity with her, ever. She was tough and direct and her eyes lit up when she was happy, which was every single time she saw Rand, and sometimes when she saw me, too.

She didn’t die of Covid, but the pandemic darkened her final months – we couldn’t see her, and had to wave at her through a window. As she neared the end of her life, we were allowed in-person visits. The last time I saw her, she wasn’t able to say or even move all that much, but she pulled me down to her and kissed me, which she wasn’t supposed to do.

Our relationship didn’t simply happen. It was earned. She made me realize how valuable something is when you have to work so hard for it. I spent half my life trying to make her proud. And now that she’s gone, there’s this weird hollow spot in my chest and I honestly don’t know what to do. I can’t really write or function all that well lately (I can eat just fine, thank you very much.) But mostly, I just keep looking around and asking, “Now, what?”

Really. Now, what?

There was no funeral. The memorial was over Zoom, which, *gestures broadly* is what it is. It’s not what I wanted for her, or what she deserved. She deserved scores of people wearing tasteful black clothing and giving emotional (but not too emotional) speeches that were entirely absent of sarcasm. I’ve almost come to terms with the fact that the last year has been about not being able to celebrate the good times, or to live life the way we’d like … but to not be able to even grieve or die in the ways in which we want to … that feels like a particular type of cruelty.

I guess there’s solace in knowing that when I curl up and tell people that I just have had enough, they all seem to understand. That if I stand on a corner in my neighborhood and break down in tears, and anyone spots my sobs from behind my glasses and mask, they simply nod. Because the one thing we all seem to understand right now is what it means to miss people, and the way the things used to be. I’m mostly just trying to get through, in whatever way I can. I still hear her voice, clear as a bell, asking me what I’ve done to my hair, and wondering when, exactly, I’m going to be done with my next book.

The answer is always the same. “I don’t know. But I hope you like it.”

August 10, 2020

I Had Mail.

Six months into an interminable lockdown, I find myself missing the long dead. The throughline feels like a logical one – it’s a pandemic. Of course I’m thinking about death.

Death and the post office.

That took me slightly by surprise, even in a year where nothing has been what I’d imagined. I didn’t think we’d be arguing whether or not we, as a country, should be able to send and receive mail. Then again, I didn’t think we’d be debating on whether germ theory is real or not, either.

A few people have told me that those of us defending the United States Postal Service don’t care about the institution, but I have always regarded it with a level of fondness that one does not normally attribute to governmental institutions. It’s like finding yourself waxing poetic about the passport office or the IRS. They shouldn’t elicit an emotion other than a bit of ennui, perhaps a cold feeling of dread.

But the United States Post Office is the reason I knew my father.

To understand the role it played in our relationship, you’d have to understand a few things about my father, and me. We never lived together. I never once shared an address with him, or even a home continent. My father lived in Germany for my entire life, and I lived in America. He never had an email address, even after they became popular. He was not a huge fan of phone conversations, either.

The main way in which my father and I communicated was through letters. He would write me, regularly, beginning when I was so young that my mother had to read them to me, until a few years before his death. Thick envelopes would arrive, and he’d number the pages in order to keep them straight.

My father did not alter his message for his audience. As a very small child, I received sheet after sheet written in cursive that I could not yet decipher. Complaints about his work, detailed accounts of the weather in Munich, mentions of friends of his that he’d known for decades who I had never met. He signed every letter the same way.

“Your father, Paul.”

He was generally annoyed with everyone, mostly wanting to be left alone. Letters were the only way anyone could really be with him without having to actually spend time with him – which is how he preferred things.

I tried to test the waters, calling him “Daddy” once or twice, as I’d seen my peers do with their own fathers, but when I said it, it read as sarcastic. My father was not a sentimental person. He was not warm. He did not enjoy children. When I was young, I resented his coldness, and seldom wrote. He was not happy about this. (He let me know via letter.)

I saw my father once between the ages of ten and fifteen. Again when I was 16, once more when I was 19. But his letters arrived monthly. He was retired military, but maintained a post office box at the base, which meant I didn’t need to pay international postage rates. It cost as much to reach my father as it did to reach someone in the next county. This always baffled me as a child. It took me a long time to realize it was a service for U.S. military personnel, but also, that the post office was a governmental institution, not a business. It existed not to make money. It existed because we needed it to exist.

He rarely sent photos, though I occasionally did, especially as I entered my high school years. I’d splurge for double-prints, and send a few to him.

“This is what I look like now,” I’d write.

Years passed. The pile of letters from my father grew larger. I sorted them into neat boxes, arranged by date. I understood that he would not change. He would not be warmer. He would not kiss me or hug me. He would not sign his missives “Love, Dad.” But there was an immutable consistency in his letters. They arrived like clockwork, describing the weather in Munich in 1989, in 1995, in 2002. He sent my mother child support, sent me checks to cover tuition. He was as reliable as the mail.

Sometimes, my father would send me stamps, and I would marvel at the tiny little images from far off places. It was strangely recursive, self-referential, stamps inside a letter. I wasn’t even sure if I liked collecting them; they were so brittle, best left alone. Now, four years after his death, I have a box of them. I can’t look at them without breaking down.

I could not go to my father’s funeral. It was the week of Christmas in rural Bavaria. My stepmother gave us five days notice. By then he had already been cremated. I didn’t have the chance to say goodbye, because that sort of ceremony is reserved for people who do not live on separate continents from their fathers. Those are the sorts of things that you cannot say in letters.

A return trip ticket with less than a weeks notice would cost me ten thousand dollars. I asked my stepmother if it was possible to move the funeral. She doesn’t speak English, so her daughter yelled at me on her behalf via Facebook Messenger. The date would not be moved.

I didn’t go.

By the time I was able to make it out to Germany, after the holidays, my stepmother had cleaned out my father’s possessions. His workshop was empty, his model planes were gone. She gave me a box of old photos. I left cradling them to my chest. None of the pictures I’d sent him over the years were inside. I don’t know what happened to the letters I wrote him.

This is the part where, as a good essayist, I tell you that it is okay. That I have every letter that my father ever wrote me. That I look at them and trace our relationship back to before I can remember.

Instead I will tell you the truth: that I tried retrieving those letters from my mother’s house, but she told me that she had moved them and didn’t know where they were. Two weeks later, a kitchen fire tore through my mother’s home. No one was hurt, but my letters were gone. My father was again reduced to ashes.

Losing someone, especially someone you could never quite get a grasp on in the first place, is a strange thing. You find yourself crying at the oddest moments, over the strangest things. I hold on to a scrap of paper with my father’s handwriting on it. I cradle a toy car, pilfered from his house, on days when I need to feel something concrete. Not something warm or affectionate, because that is not who he was, but something meticulous and precise, a tiny little metal Mercedes that feels heavy in my hand.

When I told my father I loved him, he would always respond “Fine,” his annoyance stretching out the syllables.

I still send letters when I can. I write thank you notes on occasion. I mail bills that could just as easily have been paid online, because I like placing the stamp in the corner of the envelope. I like doing things that remind me of my father.

I didn’t think I’d have to work so hard to remember him. I had so much documentation of our relationship, tucked into envelope after envelope. I try to remember the loops of his handwriting, how he wrote his name. I wonder what the weather is like in Munich. I think of the Post Office, and I find myself crying, because it is more thing that I didn’t think I would lose.

May 26, 2020

Just Wear a Goddamn Mask Already.

Last week, my kitchen sink collapsed. It fell from the bolts that held it, as though in protest, as though it, too, had had enough of the endless dishes and cooking. I managed to catch the edge of it, sharp even through my yellow latex gloves, and held it up with my fingers and the edges of my knees while I screamed for my husband, who did not hear me. I eventually managed to wedge a stool underneath and emailed our handyman, asking if he was comfortable working during this time. I explained to him that Rand and I had been social distancing for three months.

“I’ll be by tomorrow,” he said. I made sure I was out of the house when he said he’d arrive, but he’d texted me to say that he was delayed. I went home, and made myself a bowl of cereal, ready to dart out again before his new arrival time, but he got to the house earlier than he’d said. He walked through the door (I told him that it would be unlocked since I planned on being out), greeted me cheerfully and walked passed me into my kitchen.

He was not wearing a mask, and did not offer to put one on.

I haven’t stepped foot inside a grocery store since March. I’ve been to the pharmacy twice since lock-down started, to pick up my prescriptions. And so when our handyman walked into my home without making this one simple precautionary measure, I was stunned.

When he started to make idle chit-chat, I thought I was losing my mind.

“Are you two traveling?” he asked, knowing that we were often on the road.

“What? No. No, of course not. We’re not going anywhere.” I said, and he laughed. Our trips have been cancelled. International travel isn’t even possible during this time, and only necessary travel has been allowed by the governor. Passports aren’t even being renewed right now, and my husband’s expires at the end of the year, something which has been causing us both a measure of anxiety (“Jews don’t like it when we don’t have active passports,” Rand jokes.)

Seeing him without a mask, at ease, I assumed that he must have been socially isolating as well. That he and his family were on lockdown. Instead, he told me how he hadn’t stopped working, how he was still going to job sites and Home Depot, same as always. As he spoke, I thought of a video I saw of how breath travels, imagined tiny droplets spreading out of his mouth and across my kitchen. I tried to remember where my own mask was. It was next to the door. Because I hadn’t planned on being home when he got here.

I backed into the other room, putting a wall between us, and he laughed.

Me, literally every time I go out now.

He told me how he’d just flown back from Texas yesterday (“I was visiting my mom.”) and how the flight attendant was “a black lady who wasn’t having anything to do with masks, either.” I remember reading that you shouldn’t include someone’s race or ethnicity in a story unless it’s pertinent to the plot. I wondered why he felt necessary to include that detail, if her resistance to wearing a mask was his watered down version of “I have a black friend.” I found myself thinking about the disproportionate number of people of color who die from this illness.

When I told him that my mom’s country of Italy has been decimated by Coronavirus, he said, “Well, don’t they have a large Chinese population?”

“Yes,” I said, confused. And? He didn’t reply, and it hits me, slower than it should. The President has been calling coronavirus the “Chinese virus”, an expression that stokes xenophobia and implies, somehow, that your whiteness can protect you from the disease. I wondered how many microaggressions I’d missed from our handyman over the years, how many things I hadn’t noticed, hadn’t needed to notice – because my own whiteness had allowed me to ignore them right up until my own well-being was at stake.

Privilege is a hell of a drug, I’ll you that much. Unsure of what to do, I walked out of the room, went upstairs and cried.

He shouted at me from the bottom of the stairs, that the sink wasn’t quite done – but he fixed it enough to last for the time being, and said I could call him again to finish the job when I wasn’t “too afraid to have people in the house.” I could hear his eyes rolling from the other room. I wanted to yell at him. I should have yelled at him. I should have screamed at him that Chinese people aren’t more likely to get Coronavirus than anyone else. That masks work. That he should have fucking told me before he barged into my house without one. That when I said we’d been socially isolating, I was trying to reassure him that my home was safe, but also stating my values: I believe in science.

And if he didn’t, he had an obligation to tell me that instead of just walking in.

Instead, I stammered. I broke down into tears.

The entire time, I’d been so concerned about his own comfort, but he hadn’t once worried about mine. I asked if he’d be comfortable coming to my house during a pandemic, assuming he was just as concerned about it as I was. I’d made plans to leave the house entirely. I’d sanitized all the surfaces he was going to come in contact with. He didn’t even send me a text telling me to leave the house because he couldn’t be bothered with a mask.

After he left, I spent three hours cleaning my kitchen, wiping down cabinets and handles with bleach, scrubbing the floors. Lady MacBeth if she listened to NPR so she could pretend she was woke, but was too afraid to speak up when it actually came down to it. Our cutlery drawer was left slightly ajar, and that was enough for me to empty the contents of it into the dishwasher. I even threw out the dishwashing gloves that were sitting out when he arrived. I imagined him laughing at me. I didn’t care. I kept cleaning.

The dishes I did by hand.

Rand tells me that the CDC says it’s almost impossible to catch Coronavirus from surfaces. I nod. It’s not about that.

I’m so angry at this man who walked into our home. I’m so angry with myself. I wonder why I didn’t ask him to leave immediately. I wonder why I didn’t scream at him.

“He’s someone who always seemed to care about other people’s safety,” Rand said, noting all the precautions he’d taken with his work in the past. “It’s so disappointing that he wouldn’t care in this instance.”

But the President’s refusal to wear a mask has turned yet another public health issue into a political one. People try entering stores without them, claiming that masks are an infringement of their freedoms. I watch viral videos of people coughing on essential workers when they are refused admission, and feel my blood pressure rise.

If 80% of people wore masks, we could essentially eliminate the spread of Coronavirus.

Some are going to argue that masks don’t keep you safe – and the thing is, they’re right. They don’t. Masks keep other people safe. They’re the ultimate act of empathy. They’re a kindness we do for others – like coughing into our elbows or not tweeting out movie spoilers even weeks after something’s been released. We do it because it makes the world a better place.

Refusing to wear a mask means that your own convenience is more important than anyone else’s life. And refusing to take a virus seriously because you think the only people who are dying are ones who don’t look like you … well, that means you are a bigoted asshole.

I feel like this should be easy. Wear a mask. Don’t be racist. In short: care about other people.

After he leaves, I scrub my floors and counters with bleach until my nostrils burn. I realize I’m not just angry that I let him into my house without a mask. I’m angry that I let him into my house at all.

May 13, 2020

Seeing Through The Fog.

I’ve been staring at my computer a lot. If I do manage to type something, I will usually delete or loathe it by the day’s end.

Writer’s block doesn’t really cover what I’m feeling, because it’s not really a block. A block implies something complete and impenetrable, and this isn’t. Someone recently said that writer’s fog is a better way of describing it. Just a cloud that you are stuck in, everything hazy and unclear. On a good day, I can make out a shape or two.

I will invariably hate the shapes I make out.

“Everything I write is trash,” I tell Rand with a sort of self-indulgent loathing that surprises both of us. I had always thought you had to be confident to be this insufferable.

“It’s not trash.”

“I’m not good at this.”

“Maybe take a break,” he says gently. And I wonder how one can take a break from nothing.

—–

The last time I blogged, I wrote about how all of these feelings were okay. How it’s okay if we just can’t right now – and it’s okay if we can’t write right now. All of those things that used to come so easily, the bare minimum achievements of being a functional person, are now the things that we congratulate ourselves for doing. Getting up, brushing our teeth, putting on pants. (The last one being increasingly optional in a world where most people only see us on video from the waist up.)

I have a small checklist of these achievements that I go through each day, like I’m a houseplant on the verge of dying. I make sure I get enough water. I try to expose myself to a bit of sunlight. I make sure that I’m neither too hot nor too cold. The world is falling apart, but I am, at least, well hydrated.

Somehow, in the midst of all of this, I genuinely thought that I’d be able to get work done. I thought that the rules didn’t apply to me, that the last blog post I wrote would be a talisman against the encroaching fog. If I wrote about not being able to write during a pandemic, then, suddenly, I would be able to.

When my uncle died, more than a decade and a half ago, after a long and unforgiving illness, I remember quietly spiraling in, cocooning into a blanket and seeing no one. I blipped off the radar, though I was courteous enough to let people know before I did. My reaction was strange not simply because it was out of character (I am, above all else, an extrovert) but because it wasn’t a reaction. That is to say, it didn’t feel like I was responding to an external stimulus. It felt like it was just who I was now, emanating from within, wholly independent from what was going on. My uncle died. I was going to live in a blanket fort. I saw these things as unrelated.

One of the people I was closest to during this time sent me a barrage of texts and calls regarding my absence from our social scene. I finally gave in after six weeks of increasingly aggressive messages and met her for lunch, my first outing in a month and a half. I dreaded it, knowing I was in for a scolding. Sure enough, the first words out of her mouth were how angry she was that I hadn’t contacted her.

“I haven’t seen any of my friends,” I said.

“I’m not like your other friends,” she snapped.

Our friendship didn’t last long after that. I was tired of being yelled at by someone who didn’t understand what I was going through, even if I barely understood it myself.

Staring at my computer, aimlessly pecking at keys, I realize I can’t bully myself into writing any more than she could bully me into friendship.

I tell myself that the fog I’m in is unrelated to what’s going on in the world. And maybe it is (it’s hard to A/B test right now). It’s been going on for a very long time. If I squint, I can almost see when it started, but then everything gets blurry. It’s hard to know, really. Sometimes the world falls apart, and you go hide in a blanket fort. I see these things as unrelated, but who knows.

I’m trying to remember that I’m not immune to any of this. That telling others it’s okay to feel awful doesn’t somehow safeguard me from feeling awful. I can’t brute force my way into writing something beautiful. I can’t bully myself into creating a book during a pandemic. When doing simple things like going to the store or giving someone I love a hug are impossible, maybe the already-difficult-when-we-aren’t-in-a-global-catastrophe task of writing isn’t that easy, either.

“Maybe spend today doing research or outlining instead,” Rand says gently.

“Yeah.”

I stack up some papers, I close a few open documents. I stare at my wall of notes and squint, trying to see something through the fog. I can’t make out anything but a few shapes. I try not to beat myself up over it.