Kenneth C. Davis's Blog, page 92

September 16, 2013

Who Said It (9/16/2013)

President George Washington,“Farewell Address to the Nation” (September 19, 1796)

I have already intimated to you the danger of parties in the State, with particular reference to the founding of them on geographical discriminations. Let me now take a more comprehensive view, and warn you in the most solemn manner against the baneful effects of the spirit of party generally.

This spirit, unfortunately, is inseparable from our nature, having its root in the strongest passions of the human mind. It exists under different shapes in all governments, more or less stifled, controlled, or repressed; but, in those of the popular form, it is seen in its greatest rankness, and is truly their worst enemy.

The alternate domination of one faction over another, sharpened by the spirit of revenge, natural to party dissension, which in different ages and countries has perpetrated the most horrid enormities, is itself a frightful despotism. But this leads at length to a more formal and permanent despotism. The disorders and miseries which result gradually incline the minds of men to seek security and repose in the absolute power of an individual; and sooner or later the chief of some prevailing faction, more able or more fortunate than his competitors, turns this disposition to the purposes of his own elevation, on the ruins of public liberty.

Without looking forward to an extremity of this kind (which nevertheless ought not to be entirely out of sight), the common and continual mischiefs of the spirit of party are sufficient to make it the interest and duty of a wise people to discourage and restrain it.

Source: Avalon Project-Yale Law School

Published in a newspaper as an open letter to the American people on September 19, 1796, “Washington’s Farewell” was first drafted with the assistance of James Madison near the end of Washington’s first term in office. At the end of his second term, as he decided against a third term, it was redrafted by Alexander Hamilton, the now-disgraced former secretary of the Treasury. It is well-known for its warning againt “foreign entanglements” and the dangers of party factionalism. Although its warnings about party were unambiguous, Hamilton used the text to attack the rival Jeffersonian “Republicans.”

As Ron Chernow noted in his biography of Hamilton, “the Republican reaction was venomous and unwittingly underscored its urgent plea for unity.” (Chernow, Alexander Hamilton, p. 507)

September 9, 2013

Who Said It (9/9/2013)

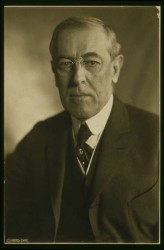

Woodrow Wilson , 1919 (Source: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs digital ID cph.3f06247.)

President Woodrow Wilson “Fourteen Points” address to Congress (January 8, 1918)

What we demand in this war, therefore, is nothing peculiar to ourselves. It is that the world be made fit and safe to live in; and particularly that it be made safe for every peace-loving nation which, like our own, wishes to live its own life, determine its own institutions, be assured of justice and fair dealing by the other peoples of the world as against force and selfish aggression. All the peoples of the world are in effect partners in this interest, and for our own part we see very clearly that unless justice be done to others it will not be done to us. The programme of the world’s peace, therefore, is our programme; and that programme, the only possible programme, as we see it, is this:

Source: Avalon Project-Yale law School

This speech outlining Wilson’s 14 point peace plan, was made after a Paris Peace Conference aimed at ending what would become known as World War I and introduced the idea of a League of Nations. (Point 14)

XIV. A general association of nations must be formed under specific covenants for the purpose of affording mutual guarantees of political independence and territorial integrity to great and small states alike.

The Treaty of Versailles, ending the war, codified these points and would have crested the League. It was rejected by the United States Senate in 1919, shortly after Wilson suffered a debilitating stroke.

For his peace-making efforts, Wilson was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1919.

September 6, 2013

“Study War No More”-Dr. King’s Other Speech

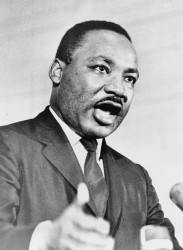

Martin Luther King Jr.Credit: United Press International telephoto,1965 Oct 11. Prints and Photographs Division of the Library of Congress.

What a difference a week makes.

The wave of good feeling that flooded over the nation when President Obama marked the fiftieth anniversary of Martin Luther King, Jr.’s “I Have a Dream Speech” is a fleeting memory. This week, Syria, not Selma, is on the nation’s mind.

But as Congress debates the President’s call for military action against Assad’s Syria over its purported use of chemical weapons, it might be an apt moment to ask, “What would Dr. King say?”

Largely overlooked by the President’s impassioned and reverential remarks, and the nostalgic good feeling that the anniversary engendered, is the great central tenet of the King legacy. Of course Dr. King’s life was devoted to racial justice and economic equality –both duly noted last week. But the other thrust of Dr. King’s mission was his commitment to non-violence and his vocal opposition to the war in Vietnam. And it is that piece of the King legacy that has been missing from the conversation.

Now, with the full-throated debate over an attack on Syria, the President, the nation, and the world would do well to recall another speech Dr. King made in Washington.

Nearly five years after the celebrated 1963 rally, and just days before his death, Dr. King delivered his final Sunday sermon at National Cathedral on March 31, 1968. King’s words that day may not have the familiar ring of “I have a dream.”

Preparing to lead the “Poor People’s Campaign” into Washington later that spring, he addressed three central issues.

He spoke first about racial equality, the glimmers of progress that had been made in five years, and the promises still to be kept. Then he turned to poverty, hunger and inadequate housing in what he called “the richest nation in the world.” This was, after all, going to be the “Poor People’s Campaign.” King knew that economic injustice could be colorblind.

But there was a third piece of Dr. King’s vision. On that day in 1968, as the war in Vietnam raged and American opposition to that war mounted, Dr. King said,

“Anyone who feels, and there are still a lot of people who feel that way, that war can solve the social problems facing mankind is sleeping through a great revolution.”

Text Source: The Martin Luther King, Jr. Research and Education Institute (Retrieved September 2, 2013)

Guided by Thoreau, Gandhi and his own Christianity, King’s belief in nonviolence and the use of civil disobedience were central to his movement’s push for racial justice. But his unflinching opposition to the war in Vietnam tends to be shunted to the sidelines when discussing King’s legacy. Certainly when he first voiced his opposition to the war, his was not a popular stance. Accused of taking the “Commie” line, Dr. King acknowledged that his antiwar views were hurting the movement and his organization.

“There comes a time when one must take the position that is neither safe nor politic nor popular,” he told the thousands who packed the Cathedral. “… I believe today that there is a need for all people of goodwill to come with a massive act of conscience and say in the words of the old Negro spiritual, ‘We ain’t goin’ study war no more.’”

Source: The Martin Luther King, Jr. Research and Education Institute (Retrieved September 2, 2013)

Ironically, King’s “other speech” was overshadowed. Later that evening, President Lyndon B. Johnson announced to a national television audience that he was withdrawing from the presidential race. The weight of the war and the growing opposition to it had combined to force Johnson from his quest for another term. And a few days later, on April 4, 1968, King was assassinated in Memphis.

In his remarks last week, President Obama said,

“The March on Washington teaches us that we are not trapped by the mistakes of history.”

This is a moment to stop and consider whether we confront another of the “mistakes of history” –like the one that trapped Lyndon B. Johnson.

Those who wish to remember Dr. King’s impact and ideas must recall more than a gauzy, feel-good rendition of “We Shall Overcome.” It is mere lip service to trumpet King’s “Dream” without acknowledging the other piece of his call to conscience:

“Simply that we must find an alternative to war and bloodshed.”

(Source: The Martin Luther King, Jr. Research and Education Institute Retrieved September 2, 2013)

September 3, 2013

New Ted-Ed animated video-Labor Day

“Why do Americans and Canadians Celebrate Labor Day?” [image error]

This new Ted-Edd animated video explains the history of the holiday and why it still matters today.

You can also view it on YouTube:

Read more about the period of labor unrest in Don’t Know Much About® History.

Don’t Know Much About History (Revised, Expanded and Updated Edition)

September 2, 2013

Who Said It? (9/2/13)

[image error]

Abraham Lincoln “First Annual Message,” December 3, 1861

Labor is prior to and independent of capital. Capital is only the fruit of labor, and could never have existed if labor had not first existed. Labor is the superior of capital, and deserves much the higher consideration. Capital has its rights, which are as worthy of protection as any other rights. Nor is it denied that there is, and probably always will be, a relation between labor and capital producing mutual benefits. The error is in assuming that the whole labor of community exists within that relation. A few men own capital, and that few avoid labor themselves, and with their capital hire or buy another few to labor for them. A large majority belong to neither class–neither work for others nor have others working for them. In most of the Southern States a majority of the whole people of all colors are neither slaves nor masters, while in the Northern a large majority are neither hirers nor hired. Men, with their families–wives, sons, and daughters–work for themselves on their farms, in their houses, and in their shops, taking the whole product to themselves, and asking no favors of capital on the one hand nor of hired laborers or slaves on the other. It is not forgotten that a considerable number of persons mingle their own labor with capital; that is, they labor with their own hands and also buy or hire others to labor for them; but this is only a mixed and not a distinct class. No principle stated is disturbed by the existence of this mixed class.

Source: Abraham Lincoln: “First Annual Message,” December 3, 1861. Online by Gerhard Peters and John T. Woolley, The American Presidency Project. http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pi....

Here is my brief history of Labor Day from Ted-Ed.

August 30, 2013

War Within a War (A Don’t Know Much About® Minute)

The worst frontier massacre in American history took place 200 years ago on August 30, 1813, when a group of Creek Indians, led by a half-Creek, half-Scot warrior named William Weatherford, or Red Eagle, attacked an outpost known as Fort Mims north of Mobile, Alabama.

Like Pearl Harbor or 9/11, it was an event that shocked the nation. Soon, Red Eagle and his Creek warriors were at war with Andrew Jackson, the Nashville lawyer turned politician, who had no love for the British or Native Americans. You know the name of Andrew Jackson, the future hero of the Battle of New Orleans and future 7th president of the United States., But you don’t know the name William Weatherford. You should. He was a charismatic leader of his people who wanted freedom and to protect his land. Just like “Braveheart,” or William Wallace of Mel Gibson fame.

Only William Weatherford, also known as Red Eagle, wasn’t fighting a cruel King. He was at war with the United States government. And Andrew Jackson.

A NATION RISING (Smithsonian/Harper Collins and Random House Audio)

This video offers a quick overview of Weatherford’s war with Jackson that ultimately led the demise of the Creek nation. You can read more about William Weatherford, Andrew Jackson, and Jackson’s role in American history in A NATION RISING

Andrew Jackson’s life and presidency are also covered in Don’t Know Much About® the American Presidents.

Don’t Know Much About the American Presidents (2012)

(From Hyperion and Random House Audio)

PBS also offers a good look at the different sides of Andrew Jackson.

August 27, 2013

Don’t Know Much About® Lyndon B. Johnson

Lyndon B. Johnson (March 1964)

(Photo: Arnold Newman, White House Press Office)

All I have I would have given gladly not to be standing here today.

Lyndon B. Johnson, in his first address as President to a joint session of Congress (November 27, 1963)

The 36th President, Lyndon B. Johnson, was born on August 27, 1908, in a small farmhouse near Stonewall, Texas on the Pedernales River. Coincidentally, it is also the date on which LBJ accepted the 1964 Democratic nomination for President. (Senator Hubert H. Humphrey was his Vice Presidential nominee.)

In some respects, history and time have been kinder to Lyndon B. Johnson than his tortured Presidency –and certainly the critics of his day—would have possibly suggested. A power broker extraordinaire during his days in Congress, especially during his twelve years in the Senate, Lyndon B. Johnson challenged John F. Kennedy for the Democratic nomination in the 1960 primaries, and then accepted Kennedy’s offer to become his Vice Presidential running mate. Johnson was credited with helping Kennedy win Southern votes and ultimately the election.

On November 22, 1963, history and America changed with Kennedy’s assassination. Johnson became President, taking the oath of office aboard Air Force One with Jacqueline Kennedy, the dead President’s widow standing beside him.

Driven by a rousing sense of social justice, born out of his youth and upbringing in hardscrabble Texas and Depression-era experiences, he had become one of Franklin D. Roosevelt’s most loyal New Dealers. First in a federal job, then in Congress and later as “Master of the Senate.” As President, Johnson set the country on a quest for what he called the “Great Society,” looking for ways to end the great economic injustice and bitter racial disparity that existed in America in 1963. But his vision for a “Great Society” was counterbalanced, and ultimately overshadowed by his doomed course in pursuing the war in Vietnam.

In the midst of the war, recently released White House tapes reveal Johnson confided–

I can’t win and I can’t get out.

Fast Facts-

•Johnson was the first Congressman to enlist for duty after Pearl Harbor.

•Johnson was the fourth president to come into office upon the death of a president by assassination. (The others were Andrew Johnson after Lincoln, Chester A. Arthur after Garfield, and Theodore Roosevelt after McKinley.)

•Johnson appointed the first black Supreme Curt Justice, Thurgood Marshall.

The Johnson Library and Museum is in Austin, Texas. Lyndon B. Johnson died at the age of 67 on January 22, 1973. His New York Times obituary.

Read more about Lyndon B. Johnson, his presidency and the Vietnam War and civil rights movement in Don’t Know Much About® the American Presidents and Don’t Know Much About® History.

Don’t Know Much About History (Revised, Expanded and Updated Edition)

[image error]

Don’t Know Much About the American Presidents

(September 18, 2012-Hyperion Books)

August 26, 2013

J.D. Salinger: Art Director

Two-Bit Culture: The Paperbacking of America by Kenneth C. Davis (1984, Houghton Mifflin (Photo© 2013 Kenneth C. Davis)

Readers of a new biography of J.D. Salinger may find the new book’s plain, all-type cover somewhat recognizable. It is certainly designed with a nod to the Bantam Books’ mass market paperback edition of Salinger’s famous novel – a cover that was familiar to a generation of readers.

But that all-type cover was not Salinger’s first paperback cover. And therein lies a fascinating piece of publishing history: J.D. Salinger as Art Director.

This is a story I recounted in my book Two-Bit Culture: The Paperbacking of America, a history of the American paperback business and especially the “Paperback Revolution” of the Fifties and Sixties. The book was published in 1984 by Houghton Mifflin.

[The following excerpt is from Two-Bit Culture: The Paperbacking of America, Houghton Mifflin, 1984, pages 202-204]

J. D. Salinger was born in New York City in 1919, attended public schools, a military academy and three colleges; he served in the army from 1942 to 1946. Salinger had been writing stories since he was fifteen and was already familiar to New Yorker readers when The Catcher in the Rye was published by Little, Brown in 1951 and became a Book-of-the-Month Club selection. After winning wide –not unanimous— critical acclaim, the novel made it to the best-seller list in The Publishers’ Weekly and stayed there for five months, although not selling well enough to make it as one of the year’s ten top-selling novels. (On the best-seller list along with Salinger’s novel were Herman Wouk’s The Caine Mutiny, Nicholas Monserrat’s The Cruel Sea, James Jones’s From Here to Eternity, and William Styron’s Lie Down in Darkness.) New American Library had purchased paperback rights in advance of publication, as Victor Weybright later recounted:

“One Friday afternoon I had received an advanced copy of J.D. Salinger’s Catcher in the Rye. I read it that evening and went into a cold sweat lest the reprint rights should be seized by a competitor if I waited until Monday morning. I tracked (Little, Brown publisher} Arthur Thornhill down on the telephone, made a deal and discovered later that we had beaten the field, most of whom did not receive their advance copies until (the) Monday or Tuesday following.” [1]

Having propelled Weybright into such a fevered paroxysm, the slim volume about sixteen-year-old Holden Caulfield and his 48-hour quixotic revolt against “phoniness” appeared in a 25-cent Signet edition with a first printing of 350,000 copies in April of 1953. A box on the cover read, “This unusual book may shock you, will make you laugh, and may break your heart—but you will never forget it.” For Signet and thirty years of readers to come,[2] that statement was largely true.

Few people were disappointed or unhappy about the book. Save one: J.D. Salinger.

Marc Jaffe (still an NAL editor at this point), who had been in communication with Salinger, recalled that the writer came to NAL’s offices to discuss the book prior to its paperback appearance.

“He said he would be much happier if the book had no illustrated cover at all. In fact, he would be happier if the book was distributed in mimeographed form. Of course, he had no control over the cover.”

Kurt Enoch, who was then responsible for covers, assigned NAL’s star artist, James Avati, to paint the cover for The Catcher in the Rye. Avati produced a simple but effective illustration that showed Holden, wearing his famous red hunting hat turned backward and carrying his Gladstone bag, walking along a city street. He was passing in front of a nightclub that had some posters of semidressed women out front and Avati was asked to dress them up a bit, even though they were in the background. It was a most inoffensive cover, yet Salinger was dismayed by it. As Jaffe explained,

“The book went on to tremendous success, but even knowing that Salinger was unhappy, NAL never changed that cover. When the license came up for renewal, I was at Bantam and it became known he was unhappy.”

Oscar Dystel, by then the head of Bantam, recalled that Little, Brown’s Arthur Thornhill (who was on the Bantam board of directors) called to tell him of Salinger’s difficulties with NAL.

“He asked me if I might be interested in discussing Salinger. I said, ‘I’ll be on the next airplane.’ I dropped everything, went to Boston, and asked Arthur what he wanted. We shook hands on a two-cent-per-book royalty and Arthur then told me that Salinger had to approve the cover. I said, ‘Anything he wants. We’ll do it on plain brown paper.’ Salinger actually sent us a swatch to show us the color he wanted. He even selected the typeface. The J and the D were set in different types. Bantam still uses that cover.”

(Note: When I quoted Oscar Dystel, Bantam still held the paperback rights to The Catcher in the Rye. They have since reverted to Little, Brown, the original hardcover publisher, which now publishes the paperback edition of the book with its original 1951 hardcover jacket art.)

And by the way, more than 60 years after it appeared in print, The Catcher in the Rye remains among the “Most Banned and Challenged Books,” according to the American Library Association , which tracks attempts to remove books from school and public libraries.

[1] Victor Weybright, The Making of a Publisher (New York: Reynal & Company, 1966, p. 242.

[2] This was written in 1983, a little more than 30 years after the original publication of The Catcher in the Rye.

Who Said It? (8/26/2013)

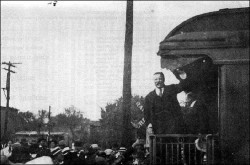

Theodore Roosevelt: Looking northeast on Main street, Osawatomie, from the Missouri Pacific railroad depot. (Source Kansas Historical Society/ Photo courtesy Dike Dickerson.)

Theodore Roosevelt “New Nationalism Speech” (August 31, 1912)

“There can be no effective control of corporations while their political activity remains. To put an end to it will be neither a short nor an easy task, but it can be done.

We must have complete and effective publicity of corporate affairs, so that the people may know beyond peradventure whether the corporations obey the law and whether their management entitles them to the confidence of the public. It is necessary that laws should be passed to prohibit the use of corporate funds directly or indirectly for political purposes; it is still more necessary that such laws should be thoroughly enforced. Corporate expenditures for political purposes, and especially such expenditures by public service corporations, have supplied one of the principal sources of corruption in our political affairs.”

(Source: “Fifty Core Documents” TeachingAmericanHistory.org

Theodore Roosevelt was the former president when he delivered this speech in Osawatomie, Kansas. It came during during the boisterous 1912 presidential campaign in which he challenged incumbent William Howard Taft, his hand-picked successor as president, and Woodrow Wilson, the Democratic candidate. Roosevelt had bolted the Republican Party after Taft was nominated and ran as third-party candidate of the Progressive Party, popularly known as the Bull Moose Party.

The speech was labeled “socialistic,” “communistic,” and “anarchistic,” but was also hailed by progressives throughout the country. In addition to Roosevelt’s sharp attacks on the influence of corporate power on government, he outlined a raft of social reforms including:

•suffrage for women

•an eight-hour-work day

•a securities commission to regulate Wall Street

•a social insurance program (which would eventually become Social Security passed during the administration of Franklin D. Roosevelt)

•primary elections and the direct election of Senators

•a Constitutional amendment that would permit a federal income tax.

Wilson won the election, with Roosevelt finishing second and Taft in third– the two men split the Republican vote and ensuring Wilson’s victory.

Osawatomie was most famous as the site of a battle in August 1856 between anti-slavery forces led by John Brown and pro-slavery raiders during the period of a bloody war to determine the future of slavery in the Kansas territory.

President Obama also delivered an address at Osawatomie on December 6, 2011 in which he repeated a call for reform based on some of Theodore Roosevelt’s ideas.

“Now, just as there was in Teddy Roosevelt’s time, there is a certain crowd in Washington who, for the last few decades, have said, let’s respond to this economic challenge with the same old tune. ‘The market will take care of everything,’ they tell us.”

Read more about Roosevelt, his presidency and the election of 1912 in Don’t Know Much About® the American Presidents and Don’t Know Much About® History.

August 21, 2013

What You Don’t Know Can Be Thrilling!

[image error]

[image error]

BRING KENNETH C. DAVIS and the DON’T KNOW MUCH ABOUT® QUIZ

TO YOUR SCHOOL OR OTHER EVENT

Treat your audience to a

Don’t Know Much About® Quiz

with New York Times bestselling author Kenneth C. Davis

The Don’t Know Much About® Quiz is an audience participation game modeled on TV quiz shows, with wide appeal to students, parents and teachers. Bestselling author Kenneth C. Davis sets the tone for the event by briefly introducing himself and describing the Don’t Know Much About® series of books and audios, which is aimed at making learning fun. Then Davis chooses “contestants” using a variety of easy questions thrown out to the audience. (Example: Name the first 13 states.)

The contestants are then divided into two teams of 3 or 4 players, who stand at tables on which there are lights and buzzers. Like a game-show MC, Davis asks a question and the players must buzz first for the chance to answer the question. The first team to reach five correct answers is the winner. (That number can be adjusted, but works well in order to accommodate as many players as possible.)

The questions are usually drawn from all of Davis’s books and audios. However, they can be tailored to a specific event, holiday, or location.. Some of the questions are straightforward (Who was the first president born in the United States?). But Davis also uses riddles, jokes and puns. Following a correct response, Davis elaborates on the answers to turn the contest into a real teaching session as well as a lively, fast-paced and entertaining game.

Davis has presented this game at the American Museum of Natural History, the Smithsonian Museum and the New-York Historical Society. He has performed in bookstores, science centers, classrooms, school gyms and teacher and librarian meetings. He has done it with groups as small as ten and as large as 200, and he has worked with students from elementary grades through middle school and high school. The reaction is always the same, as excited kids clamor for a chance to be a game show contestant. Adults also love to play and Davis has brought the game show to groups of teachers and parents and book festivals in Boston and Chicago.

The simplicity of the setup and the range of questions that can be drawn from Davis’s many books and audios make this a flexible event suitable for many audiences and venues. For more information, please contact us.

Because what you don’t know can be thrilling!