Jamie Parsley's Blog, page 36

November 3, 2019

All Saints Sunday

November 3, 2019

November 3, 2019

Ephesians 1.11-23

+ This past Friday was a very important day in the Church. Capital C. The wider, universal Church. And for all of us.

It was one of the really important feast days. November 1 was All Saints Day. It is the day in which we commemorate all the saints who now dwell with Christ in heaven. It is a beautiful feast.

On this Feast, we celebrate the saints—those who are both well-known saints and those saints who might only be known to a few. And when anyone from St. Stephen’s dies, or when anyone close to someone at St. Stephen’s dies, you will always receive an email with a request for prayer. And the request for prayer will usually begin with these words:

“The prayers of St. Stephen’s are requested for the repose of the soul of …so-and-so.”

Occasionally, someone will ask me about that prayer request. Someone will ask, Why do we pray for the dead?

Why do we pray for the repose of their souls?

After all, they’ve lived their lives in this world and wherever they’re going, they’re there long before a prayer request goes out.

The fact is, we DO pray for our dead. We always have—as Anglicans and as Episcopalians. You will hear us as Episcopalians make their petition for prayer when someone dies that you won’t hear in the Lutheran Church, or the Methodist Church or the Presbyterian Church.

Praying in such a way for people who have passed has always been a part of our Anglican tradition, and will continue to be a part of our tradition. And I can tell you, I like that idea of praying for those who have died.

But, I want to stress, that although we and Roman Catholics both pray for our dead, we don’t pray for people have died for the same reasons Roman Catholics do. In other words, we don’t pray to free them from purgatory, as though our prayers could somehow change God’s mind.

Rather, we pray for our deceased loved ones in the same way we pray for our living loved ones. We pray for them to connect, through God, with them. We pray to remember them and to wish them peace.

Still, that might not be good enough answer for some (and that’s all right). So…let’s hear what the Book of Common Prayer says about it. And, yes, the Book of Common Prayer does address this very issue directly. I am going to have you pick up your Prayer Books and look in the back, to the trusty old Catechism.

There, on page 862 you get the very important question:Why do we pray for the dead?

The answer (and it’s very good answer): “We pray for them, because we still hold them in our love, and because we trust that in God's presence those who have chosen to serve [God] will grow in [God’s] love, until they see [God] as [God] is.”

That is a great answer!

We pray that those who have chosen to serve God will grow in God’s love. So, essentially, just because we die, it does not seem to mean that we stop growing in God’s love and presence. I think that is wonderful and beautiful. And certainly worthy of our prayers.

But even more so than this definition, I think that, because we are uncertain of exactly what happens to us when we die, there is nothing wrong with praying for those who have crossed into that mystery we call “the nearer Presence of God.” After all, they are still our family and friends. They are still part of who we are. This morning we are commemorating and remembering those people in our lives who have helped us, in various way, to know God. As you probably have guessed from the week-long commemoration we have made here at St. Stephen’s regarding the Feast of All Saints, I really do love this feast. With the death of many of my own loved ones in these last few years, this Feast has taken on particular significance for me.

What this feast shows me is what you have heard me preach in many funeral sermons again and again.

I truly, without a doubt, believe that what separates those of us who are alive here on earth, from those who are now in the “nearer presence of God” is truly a very thin one. And to commemorate them and to remember them is a good thing for all us.

I do want us to think long and hard about the saints we have known in our lives. And we have all known saints in our lives.

We have known those people who have shown us, by their example, by their goodness, that God works through us. And I want us to at least realize that God still works through us even after we have departed from this mortal coil. Ministry in one form or the other, can continue, even following our deaths. Hopefully, we can still, even after our deaths, do good and work toward furthering the Kingdom of God by the example we have left behind.

For me, the saints—those people who have gone before us—aren’t gone. They haven’t just disappeared. They haven’t just floated away and dissipated like clouds out of our midst. No, rather they are here with us, still.

They join with us, just as the angels do, when we celebrate the Eucharist. For, especially in the Eucharist, we find that “veil” lifted for a moment. In this Eucharist that we celebrate together at this altar, we find the divisions that separate us are gone. We see how thin that veil truly is. We see that death truly does not have ultimate power over us. We see that the God of Life is ultimately victorious!

I can’t tell you how many times over the years I have heard stories from one priest or layperson or the other who have said they have experienced, especially during the Eucharist, the presence, of the multitude of saints, gathered together to worship. And there have been moments during our own liturgies here, even fairly recently, when I have felt the presence of our departed members.

Every time we worship, we worship with those who are now worshiping in the Presence of Christ. And so, when we worship here, it does feel sometimes like people we loved and worshiped with are here with us still.

It is like all those we have known in this life are still with us, still here, in that one holy, thin moment when the veil between here and there is parted for a moment. And I am very grateful for that holy moment. I am grateful to know they are still with us in some holy and beautiful way.

That is the way Holy Communion should be. It’s not just us, gathered here at the altar. It’s the Communion of all the saints.

In fact, before we sing that glorious hymn, “Holy, Holy Holy” during the Eucharistic rite, you hear me say, “with angels and saints and all the company of heaven we sing this hymn of praise.”

That isn’t just sweet, poetic language. It’s what we believe and hope in.

In these last few years, after losing so many people in my family and among close friends, I think I have felt their presence most keenly, at times, here at this altar when we are gathered together for the Eucharist then at any other time. In fact, on the day my mother died, as I was at the altar, I felt her presence in a strange and unique way. It was at that moment, I found out later, that she was departing from this world. And yet, she was there with me in a very powerful and very real way! And in those moments, know in ways I never have before, how thin that veil is between us and “them.”

You can see why I love this feast. It not only gives us consolation in this moment, separated as we are from our loved ones, but it also gives us hope.

We know, in moments like this, where we are headed. We know what awaits us. No, we don’t know it in detail. We’re not saying there are streets paved in gold or puffy white clouds with chubby little baby angels floating around. We don’t have a clear vision of that place.

But we do sense it. We do feel it. We know it’s there, just beyond our vision, just out of reach and out of focus. And “they” are all there, waiting for us. They—all the angels, all the saints, all our departed loved ones.

So, this morning—and always—we should rejoice in this fellowship we have with them. We should rejoice as the saints we are and we should rejoice with the saints that have gone before us.

In our collect this morning, we prayed that “we may come to those ineffably joys that you have prepared for those who truly love you.”

Those ineffably joys await us. They are there, just on the other side of that thin veil. And if we are only patient, we too, as Paul tells us in his letter to the Ephesians this morning, will obtain that inheritance that they have gained. We too will live with them in that place of unimaginable and ineffable joy and light. And that is a reason to rejoice this morning.

Published on November 03, 2019 14:01

October 27, 2019

20 Pentecost

October 27, 2019

October 27, 2019Luke 18.9-14

+ Since I’ve been your priest here at St., Stephen’s of quite some time now, you have gotten to known some of my pet peeves. Let’s open it up. What are some of my pet peeves?

Well, certainly only one of the big ones as a priest is none other than: triangulation. If you want to set me off like a rocket, try to nudge me into that fun catch-22.

Here’s essentially what triangulation is: Sometimes people come to me as a priest and, because they have some issue with another parishioner, they want me to go to that other person and deal with the situation this other person is having on their behalf.

The excuse here is that, since it is a church issue, the “church guy” should take care of this issue for them. After all, I must be on their side of this issue, right?

Now, to be clear, THEY don’t want to confront the person. But they seem to think it’s somehow the priest’s job to confront that person for them and for this particular issue that they themselves see as something that needs to be confronted.

Before we go on from here I just want to be clear: It is NOT the priest’s job to do this. Nowhere in my contract does it say I am to do this kind of a job. What this triangulation does is it puts the priest not in their rightful position as priest, but only puts them in an awkward situation in which they can’t win. Stuck right in the middle.

One of the things I have been very proactive about in my ministry is avoiding that ugly situation of triangulation. Triangulation, as you can guess, is one of the quickest “clergy killers” out there. You want your priest out, all of you have to do is try to draw them into an ugly triangle like this.

Actually, I luckily, have not really had to deal with triangulation much here at St. Stephen’s very often. And those times when it has come up, I have reacted pretty strongly against it. One of the great aspects of St. Stephen’s has been the self-reliance of the parishioners. But, in other congregations, let me tell you, they do attempt to resort to triangulation quite often. And…I hear many fellow clergy share stories in which they have found themselves trapped in the middle of those situations.

In the past, when I have found myself being nudged into such a situation, I finally have had to ask a question. I, of course, tell the person: you need to talk to this person if you have an issue with them. You’re talking to them will probably be much more successful than my talking to them on your behalf.

But, if that doesn’t work—and it usually doesn’t work—I ask those people: “have you tried praying for them?” And I’m not saying, praying for them to change, for them to be more like what you expect them to be. Have you just prayed for them, as they are? Because when we do that, we find that maybe nothing in that other person changes—ultimately we can’t control how other people act or do things—but rather weare the ones who change. We are the ones who find ourselves changing our attitude about that person, or seeing that person from another perspective.

However it works, prayer like this can be disconcerting and frightening. Let me tell you. I have done it. I’ll be honest: I have had issues with people who do not meet my own personal expectations.

But I do find that as I pray for them, as I struggle before God about them, sometimes nothing in that other person changes. (God also does not allow God’s self to be triangulated) But I often find myself changing my attitude about them, even when I don’t want to.

Prayer, often, is the key. But not controlling prayer. Rather, prayer that allows us to surrender to God’s will. That’s essentially what’s happening in today’s Gospel reading.

In our story we find the Pharisee. A Pharisee was a very righteous person. They belonged to an ultra-orthodox sect of Judaism that placed utmost importance on a strict observance of the Law of Moses—the Torah.

The Pharisee is not praying for any change in himself. He arrogantly brags to God about how wonderful and great he is in comparison to others.

The tax collector—someone who was ritually unclean according the Law of Moses— however, prays that wonderful, pure prayer

“God, be merciful to me, a sinner!”

It’s not eloquent. It’s not fancy. But it’s honest. And it cuts right to heart of it all.

To me, in my humble opinion, that is the most perfect prayer any of us can pray.

“God, be merciful to me, a sinner!”

It’s a prayer I have held very, very dear for so long. And it is a prayer that had never let me down once. Prayers for mercy are probably one of the purest and most honest prayers we can make. And what I love even more about this parable is the fact that the prayer of the Pharisee isn’t even necessarily a bad prayer in and of itself. I mean, there’s an honesty in it as well.

The Pharisee is the religious one, after all. He is the one who is doing right according to organized religion. He is doing what Pharisees do; he is doing the “right” thing; he is filling his prayer with thanksgiving to God.

In fact, every morning, the Pharisee, like all orthodox Jewish men even to this day, pray a series of “morning blessings.” These morning blessings include petitions like

“Blessed are you, Lord God, King of the Universe, who made me a son of Israel.”

“Blessed are you, Lord God, King of the Universe, who did not make me a slave.”

And this petition:

“Blessed are you, Lord God, King of the Universe, who did not make me a woman.”

So, this prayer we hear the Pharisee pray in our story this morning is very much in line with the prayers he would’ve prayed each morning.

Again, we should be clear: we should all thank God for all the good things God grants us. The problem arises in the fact that the prayer is so horribly self-righteous and self-indulgent that it manages to cancel out the rightness of the prayer. The arrogance of the prayer essentially renders it null and void.

The tax collector’s prayer however is so pure. It is simple and straight-to-the-point. This is the kind of prayer Jesus again and again holds up as an ideal form of prayer. But what gives it its punch is that is a prayer of absolute humility.

And humility is the key here. It gives the prayer just that extra touch. There is no doubt in our minds as we hear this parable that God hears—and grants—this prayer, even though it is being prayed by someone considered to be the exact opposite of the Pharisee.

Whereas the Pharisee is the religious one, the righteous one, the tax collector, handling all that pagan unclean money of the conquerors, is unclean. He is an outcast.

Humility really is the key. And it is one of the things, speaking only for myself here, that I am sometimes lacking in my own spiritual life.

But, humility is important. It is essential to us as followers of Jesus.

St. Teresa of Avila, the great Carmelite saint, once said, “Humility, humility. In this way we let our Lord conquer, so that [God] hears our prayer.”

I think we’re all a bit guilty of lacking humility in our own lives, certainly in our spiritual lives and in being self-righteous when it comes to sin. We all occasionally find ourselves wishing we could control and correct the shortcomings and failures of others. When a person fails miserably, or is caught in a scandal, find myself saying: “Thank God it’s them and not me.” Which is terrible of me! And maybe that’s also an honest prayer to make. Because what we also say in that prayer is that we, too, are capable of being just that guilty.

We all have a shadow side. And maybe that’s what we’re seeing in those people we want to correct. There’s no way around the fact that we do have shadow sides. But the fact is, the only sins we’re responsible for ultimately—the only people who can ultimately control—are our own sins—not the sins of others.

We can’t pay the price of other’s sins—only Jesus can and has done that—nor should we delight in the failings or shortcomings of others. All we can do as Christians, sometimes, is humble ourselves. Again and again.

Sometimes all we can do is let God deal with a situation, or a person who drives us crazy.

God, have mercy on me, a sinner

We must learn to overlook what others are doing sometimes. Doing so, exhausts me. And so I don’t know why I would want to deal with other’s issues if my own issues exhaust me.

There are too many self-righteous Christians in the world. We know them. They frustrate us. And they irritate us. We don’t need anymore.

What we need are more humble, contrite Christians. We need to be Christians who don’t see anyone as inferior to us—as charity cases to whom we can share our wealth and privileges and whom we wish to control and make just like us.

Rather, to paraphrase the great St. Therese of Lisieux: we should sit down with sinners, not as their benefactors but as the “most wretched of them all.”

That is true humility. In our own eyes, if we carry true humility within us, if we are our own stiffest and most objective judges, then we know that we are the most wretched of them all and that we are in no place to condemn others. In dealing with others, we have no other options than just simply to love those people—fully and completely, even when they drive us crazy.

Sin or no sin, we must simply love them and hate our own sins. That is what it means to be a true follower of Jesus. It is essential if we are going to truly love those we are called by Jesus to love and it is essential to our sense of honesty before God.

So, let us steer clear of such self-righteousness. But, in being humble, let us also not beat ourselves up and be self-deprecating. Rather, let us work to overcome our own shortcomings and rise above them. Let us look at others with pure eyes—with eyes of love. Let us not see the shortcomings and failures of others, but let us see the light and love of God permeating through them, no matter who they are. And with this perception, let us realize that all of us who have been humbled will be lifted up by God and exalted in ways so wonderful we cannot even begin to fathom them in this moment.

Published on October 27, 2019 16:14

October 20, 2019

19 Pentecost

October 20, 2019

October 20, 2019Genesis 32.22-31; 2 Timothy 3.14-4.5; Luke 18.1-8

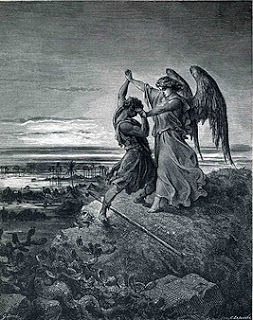

+ In our reading from the Hebrew scriptures today, we get this very famous, very visual story of Jacob wrestling with the angel. It is a story that really grabs us. It captures our imagination.

We can actually picture this momentous event. Maybe we do because most of us think instantly when we hear this story of that famous Gustav Dore illustration, of Jacob

and the Angel locked in battle, pushing against each other, the angel’s wings raised above the scene.

and the Angel locked in battle, pushing against each other, the angel’s wings raised above the scene. And I know, we often like to personalize this story. I know we tend to look at this battle between ourselves and God.

But I once heard a preacher share how in her opinion this could very much be an analogy for our own struggled with the Word of God or scripture. I love that analogy. Because, that also is true. Oftentimes, our struggle with scripture feels like we’re wrestling with an angel.

You’ve heard me reference scripture as a potentially dangerous two-edged sword. An often unwieldy two-edged sword, especially for those who use it as a weapon.

And we’ve all known those people who use the Bible as a weapon.

You’ve heard me say, again and again, that if our intention is to cut people down with the sword of scripture, just be prepared… It too will in turn cut the one wielding the sword. And I believe that. That is what scripture does when we misuse it.

However, if we use scripture as it meant to be used—as an object of love, as a way in which God can speak to us—then it is also two-edged. If we use it as way to open the channels of God’s love to others, then the channels of God’s love will be opened to us as well.

Now, I am very firm on this point. When it comes to people using scripture in a negative way, wildly waving that sword around, I love crack the knuckles. Because, I truly do love the Bible.

We all should crack our knuckles whenever we see or hear people misusing the scriptures in such a way.

After all, we are followers of Jesus, and as followers of Jesus we hold the scriptures in the same esteem as Jesus did. OK. “Esteem” isn’t the right word. We, as followers of Jesus are steeped and saturated with scripture just as Jesus was seeped and saturated with scripture.

Why?

Well, let’s just take a book in our Prayer Book. If we look in our Prayer Book, as we do on a very regular basis, back in that place I like to direct us to go sometimes—the Catechism—we find a little expansion on this thinking. On page 853, you will find this question:

“Why do we call the Holy Scriptures the Word of God?”

The answer:

“We call the Holy Scriptures the Word of God because God inspired their human authors and because God still speaks through the Bible.”

I think that is a wonderfully down-to-earth, practical and rational explanation. Still, that doesn’t mean that we can use and misuse it by taking it out of context. And let’s face it; there are scriptures that we don’t like hearing.

But none of gets to edit the Bible. We don’t get to cross out those things we don’t like. We have to confront those difficult and uncomfortable scriptures and meet them face-on. And we have to wrestle with them, as Jacob wrestled with that angel, and in wrestling with them we must use a good dose of reason, and a good dose of tradition, as good catholic-minded Anglicans do. And if we do that, we come away from those difficult scriptures with a new sense of what they say to us.

For example, I personally might not like what the Apostle Paul says sometimes—I might not even agree with it—but, good or bad, it isn’t up to me. Or any of one of us. It’s up to the Church, of which we, as individuals, are one part and parcel.

For us Episcopalians, we don’t have to despair over those things Paul says that might offend our delicate 21st century ears. We just need to remind ourselves that our beliefs about Scripture are based on a rational approach tempered with the tradition of the Church.

In fact, if we continue reading on page 853 in the Catechism, we will find this answer to the question, “How do we understand the meaning of the Bible?”

The answer:

“We understand the meaning of the Bible by the help of the Holy Spirit, who guides the Church in the true interpretation of Scripture.”

There you see a very solid approach to understanding Scripture. Reason (in this sense the inspiration of the Holy Spirit), along with the Church (or Tradition) helps us in interpreting Scripture.

Very Anglican. Think of Richard Hooker’s 3-legged stool of Scripture, tradition and reason.

Such thinking prevents us from falling into that awful muck of fundamentalist heresy. Such thinking steers us clear of this misconception that that the Scriptures are without flaw. Such thinking also steers clear of throwing the baby out with the bathwater, with regard to Scripture as well. Sometimes, if we use too much reason in our approach to Scripture, we find ourselves reasoning it all away and it becomes nothing but a quaint book of myths, morals and legends.

Yes, the Scriptures are not without flaws. As God-inspired as they might be, they were written by fallible human beings. Pre-scientific human beings, writing in a language that has been translated and retranslated over and over again.

I hate to break the news to you, but God didn’t set down a perfectly formed Bible, writ in stone and perfect King James English in our midst.

And human beings have been notorious—even in Scripture—of not always being able to get everything perfect, no matter how God-inspired they are. Not even Scripture expects us to be perfect.

But, the second part our explanation of the question from the Catechism of why we call Holy Scripture the Word of God is even more important to me.

“God still speaks to us through scripture.”

I love the idea that God does still speak to us through these God-inspired writings by flawed human beings. And what God speaks to us through Scriptures is, again and again, a message of love and justice, even in the midst of some of the more violent, or fantastic stories we read in Scripture.

Our Gospel reading is a prime example of that. What does the widow in Jesus’ parable pray?

“Grant me justice against my opponent,” she prays.

This also a truly interesting story.

This widow, who would not take no for an answer, persisted. This widow, who, in that time and place without a man in her life was in bad shape, was demanded to be heard.

This widow who had been taken advantage of (someone cheated her of her rightful inheritance) did not let discouragement stop her. This widow prayed day and night.

And what happened? God heard her. And turned the hearts of the unjust.

That, definitely, speaks to us right now. That is what we should be praying for right now in this country.

See, God is definitely speaking loudly here to us through this scripture. We are to pray for justice, not only against our opponents. But we should be praying for justice in this country and this world.

Please, God, turn the hearts of the unjust! And grant us justice!

The scriptural definition of “justice” is “to make right.” So, to seek justice from God means that something went wrong in the process, and we long for “rightness.” We too need to be praying hard, over and over again, for justice.

God also seems to be speaking loud and clear through Paul, himself a very flawed human being, in his letter to Timothy.

“All scripture is inspired by God,” Paul instructs, “and is useful for teaching, for reproof, for correction, and for training in righteousness, so that everyone who belongs to God may be proficient, equipped for every good work.”

I love that. That is some rational, solid thinking, if you ask me. Scripture here is intended not to condemn, not bash, not to hurt, but to build up and equip us for “every good work.”

“Proclaim the message, “ he tells Timothy (and us), “be persistent whether the time is favorable or unfavorable; convince, rebuke, and encourage, with the utmost patience in teaching.”

For any of us who have been teachers, those words strike home. But, if you notice, nowhere does Paul say we must condemn or pound down, or coerce others using Scripture.

Scripture must build up and encourage and teach us to serve and to love. And Scripture must be a conduit through which God continues to speak to us.

Yes, our encounter with God in scripture sometimes is very much like Jacob wrestling with angel. If scripture doesn’t do things for us sometimes, if we only go to scripture to feel good about ourselves, to prove ourselves right about things, and not be challenged, then we are using scripture incorrectly and it may, in fact, come back to cut us.

So, let us embrace this balanced and reasonable and very Anglican approach to Scripture. Let us listen to Scripture and hear the Word of God speaking to us through it. Let us continue to place the Scriptures at the center of our lives and let us allow them to guide us into a pathway of love and service. And, most importantly, let us use it, again and again, as an instrument of love rather than a weapon of war and hatred. When we do, we will find that the two-edged sword of that instrument of love, will open the doors of God’s love to us as well.

Published on October 20, 2019 19:35

October 13, 2019

18 Pentecost

October 13, 2019

October 13, 2019Luke 17:11-19

+ As a poet, I find myself obsessing over words on occasion. There are certain words I find myself examining. Often there are words I find myself examining like a little jewel, turning it around and weighing it and considering it like it’s a brand new word.

One of those words I’ve recently enjoyed re-examining is the word “Mercy.” It’s a beautiful word! And I love the fact that, in French, the word for “Thank you” is “merci.”

Mercy is something we tend to overlook. Certainly in regard to others.

But let me tell you, it is not something we overlook when it comes to us. To be on the receiving end of mercy is a wonderful thing! Mercy is like a fresh wonderful breeze on our face, especially if it is something we are being granted after a hardship in our lives. Mercy is not something we think of too often in our lives, certainly not on a daily basis.

But for Jesus and those Jewish people of his time, mercy was an important part of their understanding of the world and their relationship with God.

Tonight, at sundown, the Jewish feast of Sukkot begins Sukkot is an important feast in Judaism. It is also called “The feast of Booths,” which refers to the tents the Israelites lived in during their 40 years in the desert. In fact, in some Jewish homes, a tent is often set up during this high holy day as a commemoration of the feast.

On the Feast of Sukkot, the “Great Hallel” is prayed. Hallel means “praise,” and refers to the group of psalms recited at the time of the new moon, as well on feasts like Sukkot, which commemorates the period of time the Tribe of Israel spent in the desert on their way to the Promised Land. “Hallel” is the refrain from Psalm 136 that celebrates the fact that God’s mercy endures forever. It is believed that Jesus himself would have sang the Great Hallael with his disciples when they went to the Mount of Olives after the Last Supper on the night before his death.

Now, mercy in this context means more than just forgiveness or some kind of reprieve Mercy also means, in a Jewish understanding of the word, such things as God’s enduring love for Israel and the mercy that goes with that love. Mercy also means, in this context, behaving in a particular way. It means being ethical and being faithful to God’s will.

Mercy.

It really is an incredible word. And it is so packed with meaning and substance! And it’s one that I think sums up so many of the prayers we pray. Certainly, the prayers I pray. In those moments in which I am overwhelmed or exhausted or simply don’t know what to pray, I often find myself just praying, Please God, have mercy on me, or on the person for whom I’m praying.

Today, in our Gospel reading, we find that word, Mercy, in a very prevalent place. In fact the petition the leper makes to Jesus is a powerful one.

“Jesus, Master, have mercy on me!”

And what does Jesus do? He does just that. He has mercy on him. And, by doing so, Jesus sets the tone for us as well.

Just as Jesus showed mercy, so should we show mercy again and again in our own lives. We see, in our Gospel reading today, mercy in action. And it is a truly wonderful thing! These lepers are healed.

But, before we lose track of this story, let’s take a little deeper look at what is exactly happening. Now, first of all, we need to be clear about who lepers were in that day. Lepers, as we all know, were unclean. But they were worse than that. They were contagiously unclean. And their disease was considered a very severe punishment for something. Sin of course. But whose sin? Their own sin? Or the sins of their parents? Or grandparents?

So, to even engage these lepers was a huge deal. It meant that to engage them meant to engage their sin in some way.

But, the real interesting aspect of this story is what you might not have noticed. The lepers themselves are interesting. There are, of course, ten of them. Nine lepers who were, it seems, children of Israel. And one Samaritan leper.

Now a Samaritan, for good Jews like Jesus, would have been a double curse. It was bad enough being a leper. But to be a Samaritan leper was much worse. Samaritans, as also know, were also unclean and enemies. They didn’t worship God in the same way that good, orthodox Jews worshipped God. They had turned away from the Temple in Jerusalem. And they didn’t follow the Judaic Law that Jews of Jesus’ time strived to follow.

But the lepers, knowing who they are and what they are, do the “right” thing (according to Judaic law). Again and again, throughout the story they do the right thing.

They first of all stand far off from Jesus and the others. That’s what contagious (unclean) people do.

And when they are healed, the nine again do the right thing. They heed Jesus’ words and, like good Jews, they head off to the priest to be declared clean. According to the Law, it was the priest who would examine them and declare them “clean” by Judaic Law.

But they do one “wrong” thing before they do so. Did you notice what thing they didn’t do? Before heading off to the priest, they don’t first thank Jesus.

Only the Samaritan stays. And the reason he stays is because, as a Samaritan, he wouldn’t need to approach the Jewish priest. So, he turns back. And he engages this Jesus who healed him. He bows down before Jesus and thanks him. But Jesus does not care about this homage. He is irritated by the fact the others did not come back.

Still, despite his irritation, if you notice, his mercy remained. Those ungrateful lepers—along with the Samaritan—remain healed. Despite their ingratitude, they are still healed.

That is how mercy works.

The interesting thing for us is, we are not always so good at mercy. We are good as being vindictive, especially to those who have wronged us. We are very good as seeking to make others’ lives as miserable as our lives are at times.

If someone wrongs us, what do we want to do? We want to get revenge. We want to “show them.” After all, THAT is what they deserve, we rationalize.

But, that is not the way of Jesus. If we follow Jesus, revenge and vindictive behavior is not the way to act. If we are followers of Jesus, the only option we have toward those who have wronged us is…mercy.

Still, even then, we are not so good at mercy, especially mercy to those who have turned away from us and walked away after we have done something good for them. It hurts when someone is an ingrate to us. It hurts when people snub us or ignore us or return our goodness with indifference. In those cases, the last thing in the world we are thinking of is mercy for them.

Sadly, none of us are Jesus. Because Jesus was—and is—a master at mercy. And because he is, we, as followers of Jesus, are challenged.

If the one we follow shows mercy, we know it is our job to do so as well. No matter what. No matter if those to whom we show mercy ignore us and walk away from us. No matter if they show no gratitude to us. No matter if they snub us or turn their backs to us or ignore us.

Our job is not to concern ourselves with such things. Our job, as followers of Jesus, is simply to show mercy again and again and again. And to seek mercy again and again and again.

Have mercy on me, we should pray to God on a regular basis.

God, have mercy on me.

Please, God, have mercy on me.

Please, God, have mercy on my loved ones.

Please, God, have mercy on St. Stephen’s.

Please, God, have mercy on our country.

This is our deepest prayer. This is the prayer of our heart. This is prayer we pray when our voices and minds no longer function perfectly. This is the prayer that keeps on praying with every heartbeat within us.

And by praying this prayer, by living this prayer, by reflecting this prayer to others, we will know. We will know—beyond a shadow of doubt—that we too can get up and go our way. We too can know that, yes, our faith has made us well.

Published on October 13, 2019 12:55

October 6, 2019

17 Pentecost

17 Pentecost

17 Pentecost

October 6, 2019

Luke 17.5-10

+ This past week I was working on updating some of the wording on our website. (Make sure to take a perusal through our website www.ststephensfargo.org ).

And as I sought to find different ways to describe who we are here and what we are, I have to say, we are truly are a spiritual powerhouse. An eclectic spiritual powerhouse. And, as I was thinking about it, I realized that when we say we are truly welcoming and inclusive, we really are a welcoming and inclusive congregation.

We welcome everyone and we include everyone, even people who might not believe the same things about certain issues.

People who have different political views.

People who have different spiritual views.

As is posted on the Welcome page of our website we are:

An Inclusive Congregation of the Episcopal Churchin the progressive Anglo-Catholic Tradition

Yet, despite that description, there truly is a wide spectrum of belief here at St. Stephen’s. We encompass many people and beliefs here. And I love that! And, as I’ve said, even people who don’t believe, or don’t know what they believe, are always welcome here. And included.

That includes even atheists.

I love atheists, as many of you know. And I don’t mean, by saying that, that I love them because of some intent to convert them.

No.

My love for atheists has simply to do with the fact that I “get” them. I understand them. I appreciate them. And I have lots of atheists in my life!

Agnostics and atheists have always intrigued me. In fact, as many of you know, I was an agnostic, verging on atheism, once a long time ago in my life.

Now to be clear, agnosticism and atheism are two similar though different aspects of belief or disbelief.

An agnostic—gnostic meaning knowledge, an “a” in front of it negates that word, so no knowledge of God—is simply someone who doesn’t know if God exists or not.

An atheist—a theist is a person who believes in a god, an “a” in front of it negates it, so a person who does not believe a god—in someone who simply does not or cannot believe.

You have heard me say often that we are all agnostics, to some extent. There are things about our faith we simply—and honestly—don’t know. That’s not a bad thing.

It’s actually a very good thing. Our agnosticism keeps us on our toes. I think agnosticism is an honest response.

But atheism is interesting and certainly honest too, in this sense. Whenever I ask

an atheist what kind of God they don’t believe in, and they tell me, I, quite honestly, have to agree. When atheists tell me they don’t believe in some white-bearded man seated on a throne in some far-off, cloud filled kingdom like some cut-out, some magic man living in the sky from Monte Python’s Search for the Holy Grail, then, I have to say, “I don’t believe in that God either.”

an atheist what kind of God they don’t believe in, and they tell me, I, quite honestly, have to agree. When atheists tell me they don’t believe in some white-bearded man seated on a throne in some far-off, cloud filled kingdom like some cut-out, some magic man living in the sky from Monte Python’s Search for the Holy Grail, then, I have to say, “I don’t believe in that God either.”I am an atheist in regard to that God—that idolatrous god made in our own image. If that’s what an atheist is, then count me in.

But the God I do believe in—the God of mystery, the God of wonder and faith and love—now, that God is a God I can serve and worship. And this God of mystery and love that I serve has, I believe, reaches out to us, here in the muck of our lives. Certainly that is not some distant, strange, human-made God. Rather that is a close, loving, God, a God who knows us and is with us.

But there are issues with such a belief. Believing in a God of mystery means we now have work cut out for us in cultivating our faith in that God of mystery.

“Increase our faith!” the apostles petition Jesus in today’s Gospel.

And two thousand years later, we—Jesus’ disciples now—are still asking him to essentially do that for us as well.

It’s an honest prayer. We want our faith increased. We want to believe more fully than we do. We want to believe in a way that will eliminate doubt, because doubt is so…uncertain. Doubt is a sometimes frightening place to explore.

And we are afraid that with little faith and a lot of doubt, doubt will win out.

We are crying out—like those first apostles—for more than we have.

But Jesus—in that way that Jesus does—turns it all back on us. He tells us that we shouldn’t be worrying about increasing our faith.

We should rather be concerned about the mustard seed of faith that we have right now.

Think of that for a moment. Think of what a mustard seed really is. It’s one of the smallest things we can see. It’s a minuscule thing. It’s the side of a period at the end of a sentence or a dot on a lower-case I (12 point font).

. = (the actual size of a mustard seed)

It’s just that small.

Jesus tells us that with that little bit of faith—that small amount of real faith—we can tell a mulberry tree, “be uprooted and planted in the sea.” In other words, those of us who are afraid that a whole lot of doubt can overwhelm that little bit of faith have nothing to worry about. Because even a little bit of faith—even a mustard seed of faith—is more powerful than an ocean of doubt. A little seed of faith is the most powerful thing in the world, because that tiny amount of faith will drive us and push us and motivate us to do incredible things. And doing those things, spurred on and nourished by that little bit of faith, does make a difference in the world.

Even if we have 99% doubt and 1% faith, that 1% wins out over the rest, again and again.

We are going to doubt. We are going to sometimes gaze into that void and have a hard time seeing, for certain—without any doubt—that God truly is there.

We all doubt. And that’s all right to do.

But if we still go on loving, if we still go on serving, if we still go on trying to bring the sacred and holy into our midst and into this world even in the face of that 99% of doubt, that is our mustard seed of faith at work.

That is what it means to be a Christian. That is what loving God and loving our neighbor as ourselves does.

It furthers the Kingdom of God in our midst, even when we might be doubting that there is even a Kingdom of God.

Now, yes, I understand that it’s weird to hear a priest get up here and say that atheists and agnostics and other doubters can teach us lessons about faith. But they can. I think God does work in that way sometimes.

I have no doubt that God can increase our faith by any means necessary, even despite our doubts. I have no doubt that God can work even in the mustard-sized faith found deep within someone who is an atheist or agnostic. And if God can do that in the life and example of an atheist, imagine what God can do in our lives—in us, who are committed Christians who stand up every Sunday in church and profess our faiths in the Creed we are about to recite together.

So, let us cultivate that mustard-sized faith inside us. Let’s not fret over how small it is. Let’s not worry about weighing it on the scale against the doubt in our lives. Let’s not despair over how miniscule it is. Let’s not fear doubt. Let us not be scared of our natural agnosticism.

Rather, let us realize that even that mustard seed of faith within us can do incredible things in our lives and in the lives of those around us. And in doing those small things, we all arebringing the Kingdom of God into our midst.

Published on October 06, 2019 16:54

September 29, 2019

16 Pentecost

September 29, 2019

September 29, 2019Luke 16.19-31

+ I know this might reveal my bizarre side. (We all have a bizarre side, after all) But…I love the parable we heard today. I think I might be one of the very few people who do actually love it. For some, it’s just so weird and…well, bizarre. And it is. But…there’s just so much good stuff, right under the surface of it.

In it, we find Lazarus. Now, if you notice, it’s the only time in Jesus’ parables that we find someone given a name—and the name, nonetheless, of one of Jesus’ dearest friends. In most of Jesus’ parables, the main character is simply referred to as the Good Samaritan or the Prodigal Son. But here we have Lazarus. And the name actually carries some meaning. It means “God has helped me.”

Now the “rich man” in this story is not given a name by Jesus, but tradition has given him the name Dives, or “Rich Man”

Between these two characters we see such a juxtaposition. We have the worldly man who loves his possessions and is defined by what we owns. And we have Lazarus, who seems to get sicker and is hungry all the time.

In fact, his name almost seems like a cruel joke. It doesn’t seem like God has helped Lazarus at all.

The Rich Man sees Lazarus, is aware of Lazarus, but despite his wealth, despite all he has, despite, even his apparent happiness in his life, he can not even deign to give to poor Lazarus a scrap of food from all that he has.

Traditionally of course, we have seen them as a very fat Rich Man, in fine clothing and a haughty look and a skinny, wasted Lazarus, covered in sores, which I think must be fairly accurate to what Jesus hoped to convey. They are opposite, mirror images of each other.

But there are some subtle undercurrents to this story. Lazarus is not without friends or mercy in his life. In fact, it seems that maybe God really IS helping him. He is not quite the destitute person we think he is.

First of all, we find him laid out by the Rich Man’s gate. Someone must’ve put him there, in hopes that Rich Man would help him. Someone cared for Lazarus, and that’s important to remember.

Second of all, we find these dogs who came to lick his sores. The presence of dogs is an interesting one. Are they just wild dogs that roam the streets, or are they the Rich Man’s watch dogs? New Testament theologian Kenneth Bailey has mentioned that dog saliva was believed by people at this time to have curative powers. (We now know that is definitely NOT the case) So, even the dogs are not necessarily a curse upon Lazarus but a possible blessing in disguise.

Finally, when Lazarus dies, God receives him into paradise. In fact, as we hear, “angels carried him to be with Abraham.”

The Rich Man dies and goes to Hades—or the underworld. Lazarus goes up, Dives goes down.

While in paradise, while the Rich Man, in the throes of his torment, cries out to him, Lazarus, if you notice, doesn’t ignore him or turn his back on him, despite the fact that the Rich Man did just that to Lazarus.

Lazarus does not even scold him. It almost seems that Lazarus might almost be willing to go back and tell the Rich Man’s friends if only the gulf between them was not so wide.

There really is a beauty to this story and a lesson for us that is more than just the bad man gets punished while the good man gets rewarded.

But even more so, what we find is that, by the world’s standards, by the standards of those who are defined by the material aspects of this life, Lazarus was the loser before he died and the Rich Man was the winner, even despite his callousness.

And the same could be said of us as well. It might seem, at moments, as though we are being punished by the things that happen to us. It is too easy to pound our chests and throw dirt and ashes in the air and to cry out in despair and curse God when bad things happen.

It is much harder to recognize that while we are there, at the gate outside the Rich Man’s house, lying in the dirt, covered in sores, that there are people who care, that there are gentle, soothing signs of affection, even from dogs. And it is hard sometimes to see that God too cares.

To return for a moment to the beginning of our sermon and my bizarreness. Last Sunday our very own Jessica and John Anderson went out to visit the newly dedicated Fargo National Cemetery near Harwood. Well, right next door to the new VA Cemetery is Maple Sheyenne Lutheran Cemetery. As many of you know, my family plot is in that cemetery, and it is there that my parents’ ashes lie buried.

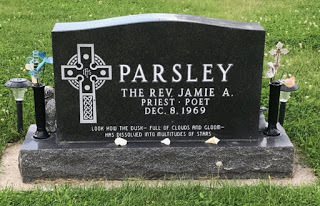

Jessica sent me a photo of my own grave while she was there. Yes, as many of you

know, I do have my gravestone made up. It’s actually the backside of my parents’ gravestone. And it even has a Celtic cross on it. I’m kind of proud of the fact that among all those Swedish Lutherans, there is a Celtic cross on my stone.

know, I do have my gravestone made up. It’s actually the backside of my parents’ gravestone. And it even has a Celtic cross on it. I’m kind of proud of the fact that among all those Swedish Lutherans, there is a Celtic cross on my stone. But what people who see my gravestone take note of is the epitaph I chose for myself. It’s actually the final line of a poem I wrote toward the end of my “cancer experience” which felt to me very much like a Lazarus experience.

The poem was written as my father and I were driving to Minot on a particularly cold night in October 2002 shortly after the first snow fall of the year. We were driving up there for my final interview with the Commission on Ministry before I was ordained to the Diaconate. As we neared the city and came up over a hill, I could see the city laid out below us. Above us, the sky had cleared after a particularly gray and gloomy day. When the clouds had cleared, we could see the stars, which, on that cold night, looked especially crisp and clear. And in that moment, after all that I had went through with my cancer, I suddenly knew for the first time, that, somehow, everything was going to be fine. At the end of that poem, I wrote what would become the epitaph on my stone. I wrote in that poem, “Dusk” (I’m not going to inflict the whole poem on you, but it’s in my book, Just Once, which I’m giving away for free):

“…I look up into the skyand see it—a transformationso subtle I almost didn’t notice itas I sit there tremblingbehind the tinted windshield.I say to myself‘Look! Just look!

Look how the dusk—full of clouds and gloom—has dissolved intomultitudes of stars!’”

My epitaph is just that:

Look how the dusk—full of clouds and gloom—has dissolved intomultitudes of stars!’”

To some extent, that’s what it’s like to be a Christian. To some extent, that’s what it’s like: when we think the darkness and the gloom has encroached and has won out, we can look up and see those bright sparks of light and know, somehow, that it’s all going to be all right.

Paradise awaits us.

It is there, just beyond those stars.

That place to which Lazarus was taken by angels awaits us and, for those of us striving and struggling through this life, we can truly cling to that hope.

For those of us still struggling, we can set our eyes on the prize, so to speak and move forward. We can work toward that place, rather than “diving” like Dives himself, into the pit of destruction he essentially created for himself.

In a real sense, the Rich Man was weighed down by his wealth, especially when he refused to share it, and he ended up wallowing in the mire of his own close-mindedness and self-centeredness.

What happens to this Rich Man? Well, the chickens came home to roost. The rich man, full of hubris and pride, full of arrogance and selfishness and self-centeredness. The rich man, who did not care for the poor, who ignored the needy, who cared only for himself, The rich man who boasted and blew smoke and walked around with his puffed-out chest, The rich man fell, as all such people we find will fall.

Scripture again and again tells us such people will fall. History again and again tells us such people will fall.

The chickens ALWAYS come home to roost.

Let us not be like the rich man. Let us not follow that slippery, dangerous slope to destruction.

But for those of us who, in the midst of our struggles, can still find those glimmers of light in the midst of the gloom, we are not weighed down. We are freed in ways we never knew we could be. We are lifted up and given true freedom.

We are Lazarus.

God truly has helped us.

And we see it most when we recognize those multitudes of light shining brightly in the occasional gloom of our lives.

Published on September 29, 2019 14:30

September 22, 2019

15 Pentecost

September 22, 2019

September 22, 2019Amos 8.4-7;1 Timothy 2.1-7; Luke 16.1-13

+ Today of course is one of those wonderful days. We get to celebrate. We celebrate our new bell tower. We celebrate our new bell—Hildegard. And we get to celebrate Hildegard too.

Here she is—this is her icon, which belongs to Sandy Holbrook. First, about our bell.

Over the past several months, we have heard a lot about our bell. A LOT. Maybe too much (but that’s all right). After all, this is not some frivolous thing we are adding to our church. It is not decoration or some “busy” thing. It is not. Nor is our altar. Not are our stations. Nor is anything else we use for sacred worship. To term these as “busy” is to demean authentic and traditional ways of giving glory to God.

A bell in a church is a truly holy and beautiful addition. This bell will be rung joyfully before out Masses and our worship services. It will be rung in celebration after marriages here. It will be tolled solemnly at the burial of our loved ones. And us.

In the Eastern Orthodox church bells are consider “aural (as in audible) ikons.” I like that image very much. What the icon, like this one of St. Hildegard, is to our eyes, so the bell is to our hearing. So, in a sense, the bell is a singing icon. It is allows us to glimpse in a very clear and tangible way the holy and mysterious that exists just on the other side of the veil that separates us from God and those who dwell with God.

And it is no coincidence that the service we just did of blessing, anointing and naming the bell is very similar to the baptismal service. That, also, is a very Orthodox tradition.

I recently read this account of bells in Russia.

“Up until the Soviet period Moscow was famous for its thousands of bells whose sounds reverberated across the city and far into the country. The Soviets were quite serious in their destruction of church bells and bell ringing was forbidden by law. Thousands of tons of sanctified and chrismated…church bells were destroyed and melted into industrial materials including weapons of war, the reverse of turning swords into plough shears.”http://www.pravmir.com/bells-as-an-orthodox-experience/

Whenever we are tempted to roll our eyes at the ringing of our bell, or whenever we forget the importance of bells in the church and the sound of bells before worship, remember the Christians in Russia for whom these very same issues were seen as threatening to those in authority. May we acknowledge our “singing icon” this bell, Hildegard, is a defiant force in the often defiant presence that is St. Stephen’s.

Just as St. Hildegard herself was a defiant force.

Now, as you read in the newsletter and have heard me talk about incessantly since, it has long been a Christian tradition to name a bell after a saint. In England, they have named bells after saints since early Christianity. And it very much an Anglican tradition to do. As my seminary, Nashotah House, the bell in the middle of campus which rings the Angelus and calls to prayer is called “Michael” after St. Michael the Archangel.

Well, our new bell, given to us graciously by Dinah Stephens in memory of her children Jada and Scott and her mother Marian, is named, very appropriately Hildegard, after the great St. Hildegard of Bingen. (Or, as Michael Eklund said, “Hildegard of Ringin’”)

St. Hildegard was a German Benedictine nun, a mystic. She was also a great musician, which is also another reason why she is the namesake for our bell.

But the real reasons she was chosen as the patron saint of our bell is because she was quite the force to be reckoned with. And let me tell you, St. Hildegard would’ve loved St. Stephen’s and all it stands for. She would fit in very well here. Though, to be honest, we probably would’ve gotten a bit frustrated with her at times.

At a time when women were not expected to speak out, to challenge, to stand up—well, Hildegard most definitely did that. She was an Abbess, she was in charge of a large monastery of women, and as such she held a lot of authority. An abbess essentially had as much authority in her monastery as a Bishop had in his diocese. She even was able to have a crosier—the curved shepherd’s crook—that is normally reserved for a bishop.

And she definitely put Bishops and kings in their place. There is a very famous story that when the emperor, Fredrick Barbarossa supported three of the anti-popes who were ruling in Avignon at that time, she wrote him a letter.

My dear Emperor,

You must take care of how you act.I see you are acting like a child!!You live an insane, absurd life before God.There is still time, before your judgment comes.

Yours truly,Hildegard.

That is quite the amazing thing for a woman to have done in her day. Even more amazing is that the emperor heeded her letter. And as a result of that letter, she was invited by the Emperor to hold court in his palace.

By “judgement” here, Hildegard is making one thing clear in her letter. There are consequences to our actions. And God is paying attention.

For us, we could say it in a different way. If you know me for any period of time, you will hear me say one phrase over and over again, at least regarding our actions. That phrase is

“The chickens always come home to roost.”

And it’s true.

One of the things so many of us have had to deal with in our lives are people who have not treated us well, who have been horrible to us, who have betrayed us and turned against us. It’s happened to me, and I know it’s happened to many of you. It is one of the hardest things to have to deal with, especially when it is someone we cared for or loved or respected. In those instances, let’s face it, sometimes it’s very true.

“The chickens do come home to roost.”

Or at least, we hope they do.

Essentially what this means is that what goes around, comes around.

We reap what we sow.

There are consequences to our actions.

And I believe that to be very true.

And not just for others, who do those things to us. But for us, as well. When we do something bad, when we treat others badly, when gossip about people, or trash people behind their backs, who disrespect people in any way, we think those things don’t hurt anything. And maybe that’s true. Maybe it will never hurt them. Maybe it will never get back to them.

But, we realize, it always, always hurts us. And when we throw negative things out there, we often have to deal with the unpleasant consequences of those actions. I know because I’ve been there. I’ve done it.

But there is also a flip side to that. And there is a kind of weird, cosmic justice at work.

Now, for us followers of Jesus, such concepts of “karma” might not make as much sense. But today, we get a sense, in our scriptures readings, of a kind of, dare I say, Christian karma.

Jesus’ comments in today’s Gospel are very difficult for us to wrap our minds around. But probably the words that speak most clearly to us are those words,

“Whoever is faithful in a very little is faithful in much.”

Essentially, Jesus is telling us this simple fact: what you do matters. There are consequences to our actions. There are consequences in this world. And there are consequences in our relation to God.

How we treat each other as followers of Jesus and how we treat others who might not be followers of Jesus. How we treat people who might not have the same color skin as we do, or who are a different gender than us, or how we treat someone who are a different sexual orientation from our own. What we do to those people who are different than us matters.

It matters to them. And, let me tell you, it definitely matters to God.

We have few options, as followers of Jesus, when it comes to being faithful.

We must be faithful. Faithful yes in a little way that brings about great faithfulness. So, logic would tell us, any increase of faithfulness will bring about even greater faithfulness.

Faithfulness in this sense means being righteous. And righteousness means being right before God.

Jesus is saying to us that the consequences are the same if we choose the right path or the wrong path. A little bit of right, will reap much right. But a little bit of wrong, reaps much wrong.

Jesus is not walking that wrong path, and if we are his followers, then we are not following him when we step onto that wrong path. Wrongfulness is not our purpose as followers of Jesus. We cannot follow Jesus and willfully—mindfully—practice wrongfulness. If we do, let me tell you, the chickens come home to roost.

We must strive—again and again—in being faithful.

Faithful to God.

Faithful to one another.

Faithful to those who need us.

Faithful to those who need someone.

Being faithful takes work.

When we see wrong—and we all do see wrong—we see it around us all the time—our job in cultivating faithfulness means counteracting wrongfulness. If there are actions and reactions to things, our reaction to wrongfulness should be faithfulness and righteousness.

Now that seems hard. And, you know what, it is. But it is NOT impossible. What we do, does matter. It matters to us. And it matters to God. We must strive to be good.

Look, Hildegard is waving her finger at us. She is saying to us, “Do good! God is watching!”

Those good actions are actions each of us as followers of Jesus are also called to cultivate and live into.

As Christians, we are called to not only to ignore or avoid wrongfulness. We are called to confront it and to counter it. Hildegard did it when she wrote Emperor Frederick Barbarossa. And we too should do it. We are called to offer faithfulness in the face of wrongfulness.

So, let us do just that in all aspects of our lives.

Let us be, like our bell, Hildegard, an “aural icon,” a loud, noisy icon, drowning out the forces of wrongfulness in this world.

Let us offer kindness and generosity and hope and truth and forgiveness and joy and love and goodness, again and again and again whenever we are confronted with all those forces of wrongfulness.

Let us offer light in the face of darkness.

Let us strive, again and again, to do good, even in small ways.

For in doing so, we will be faithful in much.

“For surely I will not forget any of their deeds,” God says in our reading from Amos today.

What we do matters. God does not forget the good we do in this world. We should rejoice in that fact.

God does not forget the good we do. What we do makes a difference in our lives and in the lives of those around us.

So let us, as faithful followers of Jesus, strive, always to truly “lead a…peaceable life in all godliness and dignity.”

Published on September 22, 2019 18:31

September 15, 2019

14 Pentecost

Sept. 15, 2019

Sept. 15, 2019Luke 15.1-10

+ As most of you know, we have a Wednesday night Mass here at St. Stephen’s at 6:00 pm. For most of those Masses, we usually commemorate a particular saint, or some Christian personage or event.

We especially commemorate saints of the Episcopal Church. (Yes, there are saints in the Episcopal Church.)

One of those of events we sometimes commemorate is a particular year. And this morning, we are going to go back to one of those momentous years. We are going back 56 years. We are going to back to 1963.

1963 was a very momentous year. Many, many life-altering events happened in the 1963.

In June of that year, there was the death of Pope John XXIII, who was, of course, very much a pioneer in advocating ecumenical relationships between different Christian denominations.

On August 27, 1963 the Rev. Martin Luther King delivered his “I Have a Dream” speech.

And today was also a very important day in 1963. In 1963, September 15 was also a Sunday.

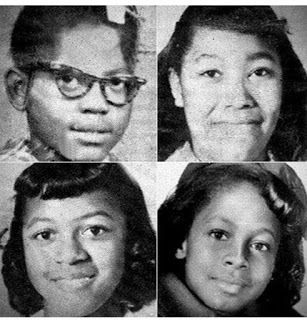

On that Sunday morning, at 10:22 am, 26 Sunday School students were filing down to the basement assembly room of the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama, to hear a sermon entitled “The Love That Forgives.”

In a dressing of the same basement, four girls--Addie Mae Collins, Carole Robertson and Cynthia Wesley, all aged 14 and Denise McNair, aged 11,were changing into their choir robes. At that moment—10:22 a.m.— a box of dynamite with a time delay planted under the steps of the church, near the basement, by four Ku Klux Klan members, exploded. Twenty-two people were injured. And those four girls in the dressing room were killed when the basement wall fell on them.

Every window in the church was blown out by the blast except one—a stained glass window of Jesus welcoming the little children.

I think it also especially appropriate that yesterday we commemorated the Feast of the Holy Cross. On that day we commemorate the actual Cross on which Jesus died.

As many of you know, it was nine years ago yesterday that my father died, very suddenly, very expectantly. Many of you have walked with me through these nine very difficult years. And I am very thankful for the support and the care during that time.

Events like these—like the events of 56 years, like the event for me nine years ago— drive home for me the fact that the cross is ultimately a symbol of victory.

Yes, for it to be a symbol of victory, there has to be, sadly, some sense of defeat. There has to be some sense that something was lost. And that in the face of defeat, in the face of loss, in the face of ruin, in the ace of failure, in the face even of death, a victory can still be won.

For us, as followers of Jesus, we are people of the Cross. There’s no way around that fact. We are people of the Cross. We are people who were not promised a sweet, burden-free lives.

Nowhere in scripture, in our liturgies, in our prayer book, are we promised a life without pain, without trouble, without sorrow. Nowhere are we told we do not have to take up our crosses. But what we are promised consistently, as followers of Jesus, is ultimate victory.

What we are promised again and again is that suffering and pain and death and tears will all one day end. One day, even the Cross will be defeated.

But life—life in our God of life and love—will never end. And that even in the face of what seems like defeat and loss, there really is ultimately victory. For those people affected by that bombing fifty-six years ago this morning, there seemed no victory.

Four little girls lost to hatred and fear seemed like ultimate defeat. But fifty-six years later, we can say that those lives were not lost in vain. Yes, fifty-six years later, we are still dealing with the KKK again, we are still dealing with white supremacists and Nazis and fascists, but we are also here, remembering those girls and we can realize now that those deaths changed things.

People who never really thought about what was happening in this country, in the South, starting thinking about those issues. And people started working to change things. The following July—on July 2, 1964—President Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act of 1964, ensuring equal rights of African Americans.

For those who followed Jesus, who betrayed him and saw him killed on that cross, they no doubt saw that death as the ultimate defeat. But here we are, followers of Jesus, today, this morning, giving thanks for the life he has given to all of us on the other side of that cross.

In our Gospel reading for this morning, we find the Pharisees and the scribes thinking Jesus and his followers were foolish. Drinking and eating with sinners seemed like folly. It seemed demeaning and uncouth.

But, by doing so, Jesus showed that sin was not a reason to despair, to beat ourselves up. Even what seems like defeat—a sinner lost to sin—can be a victory when sin is defeated, when wrongs are made right and relationships are restored.

Our lives as followers of Jesus are a series of failure and victories. We stumble, we fall, we get up and we go forward. That is what our Christian journey is. Our lives as Christians are filled with moments when it seems that the darkest night will never give way to the dawn.

But Jesus shows us that this dawn is the reality; this is what is real. That there can be no ultimate defeats in him. Not even death—probably the thing we all fear the most—not even death has ultimate victory over us.

I can tell you that on this morning, when I am still feeling emotionally raw now still nine years after my father’s death, this belief, this reality that Jesus promises us of an end to death (which my father believed), is my ultimate joy. It upholds me and keeps me going. And it should for all of us as well.

Bad things happen. Horrible, terrible things happen. Yes, there are the KKK and white supremacists and Nazis and hate-mongers marching proudly lately in a way they haven’t in a long time. But this is not defeat. This is not the end. This is not the period to the sentence of our lives.

As students of history, we know how their stories will end. We know that the KKK and Nazis and fascists and hate-mongers are on the wrong side of history, and the wrong side of God.

As followers of Jesus, we are told, again and again, rejoice. Rejoice in the face of failure and defeat.

To rejoice in the face of defeat is a defiant act. It is an act of rebellion against those dark forces. It is an act of rebellion against white supremacists and Nazis and fascists and hate-mongers. It is an act of rebellion against the power of failure, of loss, of pain.

So, let us do just that. Let us rejoice. Let us stand up against those moments in which we have been driven to ground and are left weak and beaten. Let us stand up from them, defiant, confident in the One we follow. Let us stand, when our legs are weak from pain and loss, when our hearts are heavy within us, when we are bleeding in pain and our eyes are filled with tears. Let us stand up when the forces of evil and hatred and death seemed to have won out. And when we do, when we rise from those ashes, when we rise above that darkness and stand in that brilliant light, it is then—in that glorious moment—when we will truly and fully live.

Published on September 15, 2019 23:30

September 8, 2019

Dedication Sunday

September 8, 2019

September 8, 20191 Kings 8:22-23,27b-30;

+ This past week, has been an exciting week for us here at St. Stephen’s. Yes, the tower arrived! And, yes, it looks great! See. I told you it would.

Also, today, we are celebrating our Dedication Sunday. We are commemorating 63 years of service to God and others.

We are starting up Children’s Chapel again.

We are blessing backpacks.

And we are blessing this new set of new green paraments and vestments that Jean Sando made.

It’s all very exciting.

And I especially love our scripture readings for today. I love all this talk of a building being God’s house. I think we sometimes forget that fact.

We forget that this is God’s house. God, in a very unique ways, dwells with us here. But this is Sunday is more than all these physical things. It is about more than just a building, and walls, and a steel tower and vestments and paraments.

It about us being the House of God. It is about us being the tabernacles in which God dwells. It is about us and our service to God and others.

And you know what it’s really all about. It is about LOVE. Yup, it’s gonna be another love sermon.

Years ago, I read an amazing biography of the American poet Denise Levertov, I came across this wonderful quote, from another poet, St. John the Cross:

“In the evening of our lives, we will be judged on love alone.”

Later I heard a friend of mine comment on that quote by saying

“we will be judged BY love alone.”

I love that! That quote has been haunting me for years. And it certainly has been striking me to my core in these days leading up to our Dedication Sunday celebration.

If this congregation could have a motto for itself, it would be this.

“In the evening of our lives, we will be judged by love alone.”

Because this, throughout all of our 63 year history, is what we are known for at St. Stephen’s.

Love.

We are known for the fact that we know, by our words, by our actions, by our faith in God and one another, that it is love that makes the difference. And by love we will, ultimately, be judged. That’s what the Church—that larger Church—capital “C” Church— should be. But sometimes we forget what the Church should be.

This morning, there are many people here who have been wounded by that Church—the larger Church. I stand before you, having been hurt be the larger Church on more than one occasion. And for those of us who are here, with our wounds still bleeding, it is not an easy thing to keep coming back to church sometimes.

It is not any easy thing to be a part of that Church again. It is not an easy thing to call one’s self a Christian again, especially now when it seems so many people have essentially high jacked that name and made it into something ugly and terrible. And, speaking for myself, it’s not easy to be a priest—a uniform-wearing representative of that human-run organization that so often forgets about love being its main purpose.

But, we, here at St. Stephen’s, are obviously doing something right, to make better the wrongs that may have been done on a larger scale. We, at St. Stephen’s, (I hope) have done a good job I think over these last 63 years of striving to be a positive example of the wider Church and of service to Christ who, according to Peter’s letter this morning, truly is a “living stone”—the solid foundation from which we grow. We have truly become a place of love, of radical acceptance. As God intends the Church to be.

In these last 63 years, this congregation has done some amazing things. It has been first and foremost in the acceptance of women in leadership, when women weren’t in leadership.

It was first and foremost in the acceptance of LGBTQ people, when few churches would acknowledge them, much less welcome them and fully include them.

Certainly in the last few years, certainly St. Stephen’s has done something not many Episcopal Churches are doing.

It has grown. A LOT! And that alone is something we should be very grateful to God for on this Dedication Sunday.

On October 1, I will be commemorating eleven years as your priest here at St. Stephen’s. I can tell you, they have been the most incredible eleven years of my life. Personally, they have been, of course, some very, very hard years. As a priest, they have been years in which I have seen God at work in ways I never have before.

Seeing all this we need to give the credit where the credit is truly due:

The Holy Spirit.

Here.

Among us.

Growth of this kind can truly be a cause for us to celebrate that Spirit’s Presence among us. It can help us to realize that this is truly the place in which God’s dwells.

In our reading from First Kings today, we hear Solomon echoing God’s words,

“My name shall be there.”

God’s Name dwells here.

As we look around, we too realize that this is truly the home of O God. We too are able to exclaim, God’s name dwells here!

And, as I said at the beginning of my sermon, by “the home of God” I don’t mean just this building. After all—God is truly here, with us, in all that we do together. The name of God is proclaimed in the ministries we do here. In the outreach we do. In the witness we make in the community of Farg0-Moorhead and in the wider Church.

God is here, with us. God is working through us and in us. Sometimes, when we are in the midst of it all, when we are doing the work, we sometimes miss that perspective.

We miss that sense of holiness and renewal and life that comes bubbling up from a healthy and vital congregation working together. We miss the fact that God truly is here.

So, it is good to stop and listen for a moment.

It is good to reorient ourselves.

It is good to refocus and see what ways we can move forward together.

It is good to look around and see how God is working through us.

In a few moments, we will recognize and give thanks for now only our new members but for all our members and the many ministries of this church. Many of the ministries that happen here at St. Stephen’s go on clandestinely. They go on behind the scenes, in ways most of us (with exception of God) don’t even see and recognize. But that is how God works as well. God works oftentimes clandestinely, through us and around us.

This morning, however, we are seeing very clearly the ways in which God works not so clandestinely.

We see it in the growth of St. Stephen’s.

We see it in the vitality here.

We see it in the love here.

We see it in the tangible things, in our altar, in the bread and wine of the Eucharist, in our scripture readings, in our windows, in the smell of incense in the air, in our service toward each other. In US.

But behind all these incredible things happening now, God has also worked slowly and deliberately and seemingly clandestinely throughout the years. And for all of this—the past, the present and the future—we are truly thankful.

God truly is in this place. This is truly the house of God.

WE truly are the house of God.

This is the place in which love is proclaimed and acted out.

So, let us rejoice. Let us rejoice in where we have been. Let us rejoice in where we are. Let us rejoice in where we are going.