Steve Hely's Blog, page 43

October 21, 2021

One meal a day

COWEN: To close, two questions about you. You’re famous for eating only one meal a day. Do you still do that?

MCCHRYSTAL: I do.

COWEN: Okay. The question is, what’s the meal?

MCCHRYSTAL: It’s dinner.

COWEN: What do you prefer to eat for the one meal, if you have your way?

MCCHRYSTAL: I’m not a foodie; I’m basic. I like salad, but I like a very basic dinner. I like a lot of chicken. If you take me to a fancy restaurant and you try to serve me fancy food, I’ll eat it because it’s my one meal a day, but the reality is, it’s completely lost on me. I just don’t get any satisfaction. It’s very basic food in significant quantities at night.

intrigued by this diet described by Stanley McChrystal to Tyler Cowen. I believe I heard elsewhere that McChrystal supplements this with dry pretzels.

October 16, 2021

Technical Analysis

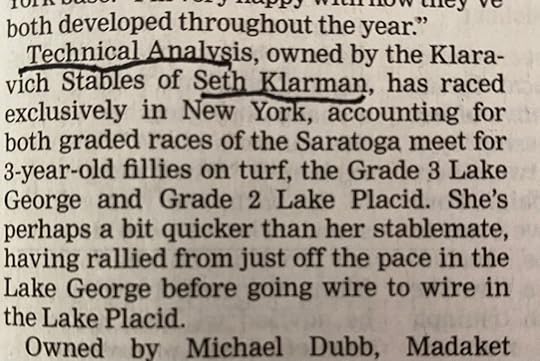

Picking up the morning racing paper like Hemingway, I spot an interesting* item:

* interesting to maybe four or five people? Seth Klarman is a famed value investor and billionaire, author of Margin of Safety, a used copy of which will run you upwards of $800, or you can go to the Central Branch of the LA Public Library and read it for free. Apparently he’s been in the horse game for some time with a not too shabby record.

Asked how much different investing in a thoroughbred is to investing in a stock, mutual fund or company, Klarman said, “In my regular life, I’m a long-term investor, so we make patient, long-term investments on behalf of our clients. This is gambling, this is a risky undertaking. This is not at all like what I do the rest of my life, but it does provide one of the highest levels of excitement that a person can have.”

source for that

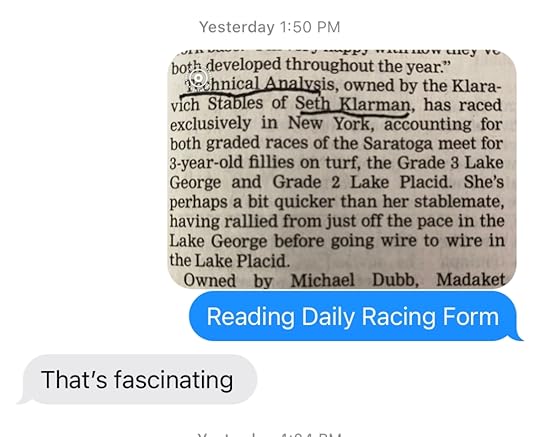

I put out the word to a few people I thought might be interested:

I’ve kept the correspondent here anonymous but trust me when I tell you: I believe he is being genuine!

My examination leads me to believe there is no “margin of safety” wagering on this horse, your safest bet in my opinion might be 10, Closing Remarks, to show, but where’s the fun in that? Analysts seem to think Aidan O’Brien can turn around Empress Josephine after just a week’s race – he’s done it before – but I dunno, I’d be tired!

Update: Technical Analysis came in 2nd, so if you’d made a “margin of safety” place or show bet, you would’ve done well: $2 to place paid $4.20, $2 to show paid $3.80. Seth Klarman, teaching us even through horses!

October 15, 2021

Hemingway at the track

I thought I would go down and buy a morning racing paper. There was no quarter too poor to have at least one copy of a racing paper but you had to buy it early on a day like this. I found one in the rue Descartes at the corner of the Place Contrescarpe. The goats were going down the rue Descartes and I breathed the air in and walked back fast to climb the stairs and get my work done. I had been tempted to stay out and follow the goats down the early morning street. But before I started again I looked at the paper. They were running at Enghien, the small, pretty and larcenous track that was the home of the outsider.

So that day after I had finished work we would go racing. Some money had come from the Toronto paper that I did newspaper work for and we wanted a long shot if we could find one. My wife had a horse one time at Auteuil named Chèvre d’Or that was a hundred and twenty to one and leading by twenty lengths when he fell at the last jump with enough savings on him to —-. We tried never to think to do what. We were ahead on that year but Chèvre d’Or would have —. We didn’t think about Chèvre d’Or.

from “A Moveable Feast.” We see here in Hemingway an example of the psychology that leads to the well–documented “favorite-longshot bias” at the track.

They still run at Enghien:

The next chapter is called “The End of an Avocation”:

We went racing together many more times that year and other years after I had worked in the early mornings, and Hadley enjoyed it and sometimes she loved it. But it was not the climbs in the high mountain meadows above the last forest, nor nights coming home to the chalet, nor was it climbing with Chink, our best friend, over a high pass into a new country. It was not really racing either. It was gambling on horses. But we called it racing.

Racing never came between us, only people could do that; but for a long time it stayed close to us like a demanding friend. That was a generous way to speak of it. I, the one who was so righteous about people and their destructiveness, tolerated this one that was the falsest, most beautiful, most exciting, vicious, and demanding because she could be profitable. To make it profitable was more than a full-time job and I had no time for that. But I justified it to myself because I wrote it. Though in the end, when everything I had written was lost, there was only one racing story that was out in the mails that survived.

It looks like Hemingway wrote a sort of tone poem about the track for the Toronto Star in 1923.

October 5, 2021

If anyone has Bergson’s On Laugher in the original French…

I’d like to know what word translator Cloudesley Brereton rendered as “merry-andrew.”

The book is dense with a lot of references to French plays I don’t know, but two points worth thinking on: Bergson says notice something comic in the mechanical, when a mechanical process overrides how we should react. He gives the example of a man who stumbles in the street.

Perhaps there was a stone on the road. He should have altered his pace or avoided the obstacle. Instead of that, through lack of elasticity, through absentmindedness and a kind of physical obstinacy, as a result, in fact, of rigidity or of momentum, the muscles continued to perform the same movement when the circumstances of the case called fro something else. This is the reason of the man’s fall, and also of the people’s laughter.

Wile E. Coyote still running over the canyon came to mind, although Bergson died before he could see that. If we review comic characters, a misguided rigidity does seem to come up a lot. Consider Sheldon.

Bergson notes our vanity is a common source for comedy, and comedy may serve to correct for vanity.

September 26, 2021

most boring job in the world?

Did The Sopranos glamorise mob life? “If you think that was glamour, you need a psychiatrist! It’s the most boring job in the world — sitting round reading the racing form all day.”

Steven Van Zandt talking to Financial Times. When I first watched Sopranos, I was absolutely drawn to Tony’s lifestyle, of just sort of driving around all day, accepting snacks. Further viewings and a deeper consideration of my character and the burdens make me think I wouldn’t trade gigs with Tony, but still, something appealing.

Also of interest:

Then David Chase approached him to play the lead in The Sopranos. At that stage, “it was a completely different show . . . a live-action Simpsons”, Chase has said. In the end, HBO vetoed someone with no acting experience as protagonist, but Chase incorporated Van Zandt into the show as Dante, a character the guitarist had himself created in a treatment for an earlier project.

FT can’t help but editorialize:

He mixes shrewd political judgment (in April, four months before the fall of Kabul, he tweeted that the US leaving Afghanistan was “a huge mistake”) with left-field ideas (such as mandatory martial-arts training for girls from kindergarten age to reduce sexual assaults).

Left-field doesn’t mean bad, FT!

September 24, 2021

a stupid man

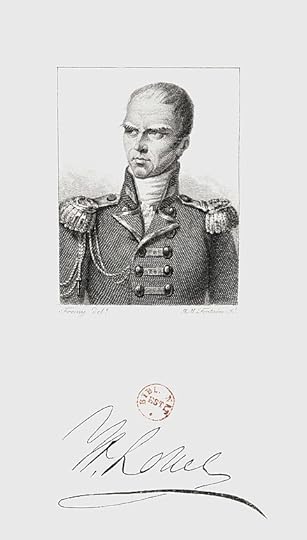

Field Marshal The 1st Duke of Wellington later said that he was “a very bad choice; he was a man wanting in education and judgment. He was a stupid man. He knew nothing at all of the world, and like all men who knew nothing of the world, he was suspicious and jealous.”

that’s re: Hudson Lowe, Napoleon’s jailer on St. Helena. This sketch doesn’t make him appear a delight to be around:

September 23, 2021

Wittgenstein on Dublin architecture

Of Dublin’s Georgian architecture, the streetscapes and squares of the city, he said: “The people who built these houses had the good taste to know that they had nothing very important to say; and therefore they did not attempt to express anything”. One thinks of the final sentence of the Tractatus, “what we cannot speak about we must pass over in silence.”

Got that from “Wittgenstein in Ireland: An Account of His Various Visits from 1934 to 1949” by George Hetherington in Irish University Review. Also of note:

September 21, 2021

Ludwig Wittgenstein

Born in Vienna to a very wealthy family, his father was a friend of Andrew Carnegie and had a near monopoly on steel in the Austro-Hungarian empire. Three of his four brothers would commit suicide, the fourth would lose an arm in World War I but still manage to become a concert pianist using only his left hand. His sister Margaret was a patient of Sigmund Freud’s and would later be painted by Klimt.

Ludwig went to the same elementary school as Adolf Hitler. There’s no clear evidence they met, although they were only two grades apart and it is possible but by no means agreed upon that the two as boys appear in the same school picture.

After studying in Berlin Ludwig worked on designing plane propellers with jet engines, he got a patent on one, but became frustrated. He went to Cambridge in the UK where he pestered Bertrand Russell. John Maynard Keynes invited him to the join the Apostles, the gay-skewing secret society. Ludwig wasn’t that into it.

In 1913 his father died and Ludwig became one of the richest men in Europe. He moved to a remote village in Norway.

(his cabin used to be to the left of this picture, I’m told)

(his cabin used to be to the left of this picture, I’m told)Eventually he found this place too busy.

When the Great War broke out, he volunteered for the Austro-Hungarian army, though he probably could’ve gotten out of it for health reasons. He served on a ship, was wounded in an explosion, became an officer directing artillery from no-man’s land, won several medals for bravery. He was there during the Brusilov offensive, where somewhere between 200,000 and 567,000 of his comrades were killed. He kept notes during the war:

The meaning of life, i.e. the meaning of the world, we can call God.

And connect with this the comparison of God to a father.

To pray is to think about the meaning of life.

In summer 1918 he took leave and went back to Vienna where his family had many house.

It was there in August 1918 that he completed the Tractatus, which he submitted with the title Der Satz (German: proposition, sentence, phrase, set, but also “leap”) to the publishers Jahoda and Siegel.

He went back to the front, this time to Italy, where he was captured and spent nine months in an Italian prison camp. After the war he gave away his huge inheritance to his siblings, and went to train to become an elementary school teacher. He became a teacher in a mountain village in Austria.

In 1921 the Tractatus was published. Here is the first sentence:

Die Welt ist alles, was der Fall ist.

Plug that into Google Translate, or use the standard translation, and you will get:

The world is everything that is the case.

Does that comma matter? Should it be:

The world is everything, that is the case

Or, in the Ogden translation, the first English version, approved by LW? Although he didn’t really speak English at the time?:

The world is all that is the case.

What about “case”? I have no background in German but looking up the word Fall it seems to also have connotations of drop, fall, instance.

That’s as far as I’ve gotten in the Tractatus. It doesn’t get easier from there:

The world is everything that is the case.[1]

1.1 The world is the totality of facts, not of things.

1.11 The world is determined by the facts, and by these being all the facts.

1.12 For the totality of facts determines both what is the case, and also all that is not the case.

1.13 The facts in logical space are the world.

1.2 The world divides into facts.

1.21 Any one can either be the case or not be the case, and everything else remain the same.

The decimal figures as numbers of the separate propositions indicate the logical importance of the propositions, the emphasis laid upon them in my exposition. The propositions n.1, n.2, n.3, etc., are comments on proposition No. n; the propositions n.m1, n.m2, etc., are comments on the proposition

Here’s my source. I have not decompressed all 75 pages.

This book will perhaps only be understood by those who have themselves already thought the thoughts which are expressed in it—or similar thoughts. It is therefore not a text-book. Its object would be attained if there were one person who read it with understanding and to whom it afforded pleasure.

As LW himself says.

After several years as an apparently terrifying rural elementary school teacher Ludwig hit a slow-witted kid on the head so hard he collapsed. In trouble, Ludwig resigned his position. He worked for a while as a gardener at a monastery. He designed a house in Vienna:

(source)

(source)It took him a year to design the door handles, and another to design the radiators

He made some long confessions to friends, about things like white lies. He went back to Cambridge for awhile. He would relax by watching Westerns in the front row of the movie theater. Invited by the President of Ireland, Eamon De Valera, himself a former math teacher, to come over there, he did. He went back to the UK and during World War II he worked in a hospital.

He started working at Guy’s shortly afterwards as a dispensary porter, delivering drugs from the pharmacy to the wards where he apparently advised the patients not to take them.

After the war there was another Irish period, along Killary:

The nearest shop/post office was 10 miles away. He had to do his own housework and saw nobody except Tom Mulkerrins, who brought him his milk and kept him supplied with turf and conversation. He used the kitchen table mostly to work on, writing his aphoristic sentences on slips of paper and taking great pains to arrange them in the correct order. He did little cooking and almost all his food came out of tins. He spent hours watching seabirds and talking to them in German. The Mortimers, who were his next nearest neighbours, thought he was mad, perhaps because he wanted them to shoot their dog, whose barking disturbed him.

(source on that).

Realizing in 2012 I took a walk along Killary Harbour (it’s a fjord) not far from where he was holed up, it looks like this:

You can walk seven miles without seeing a person, easy. It’s along Killary Harbour too that Martin McDonough set The Beauty Queen of Leenane, a masterpiece of comic cruelty. I’d be curious what Wittgenstein thought of that play.

Ludwig took a trip to the USA, he went back to the UK, he was diagnosed with prostrate cancer, he died in 1951.

Just trying to wrap my head around the basic facts of this guy’s deal, prompted by this New Statesman article on the 100th of the Tractatus.

Say what you will, this guy was something!

September 19, 2021

if I ever have to direct a movie of one of Cormac McCarthy’s books

or really any movie with significant horse action, I’m going to try to copy the way the shadows work around 1:22 in last year’s Breeders Cup Turf.

This is an interesting race. The favorite was Magical, shipped from Ireland, trained by Aidan O’Brien. The Irish are great trainers of turf horses, going back long before Stewball. Local Louisville boy Brad Cox had Arklow. Tarnawa, also from Ireland, was a four year old filly* – a girl racing against boys, past the age when females are usually still able to compete with their brothers. Channel Maker had run this race three times, finishing twelfth, eleventh, and seventh and was coming in strong.

*when exactly a filly becomes a mare is not a subject I’m prepared to opine on.

September 15, 2021

Games

When the US Congress put forward a bill in 1969 suggesting that cigarette advertisements be banned from television, people expected American tobacco companies to be furious. After all, this was an industry that had spent over $300 million promoting their products the previous year… So, what did they choose to do? Pretty much nothing.

Far from hurting tobacco companies’ profits, the ban actually worked in the companies’ favor. For years the firms had been trapped in an absurd game. Television advertising had little effect on whether people smoked, which in theory made it a waste of money. If the firms had all got together and stopped their promotions, profits would almost certainly have increased. However, ads did have an impact on which brand people smoked. So, if all the firms stopped their publicity, and one of them started advertising again, that company would steal customers from all the others.

Whatever their competitors did, it was always best for a firm to advertise. By doing so, it would either take market share from companies that didn’t promote their products or avoid losing customers to firms that did. Although everyone would save money by cooperating, each individual firm would always benefit by advertising, which meant all the companies inevitably ended up in the same position, putting out advertisements to hinder the other firms. Economists refer to such a situation – where each person is making the best decision possible given the choices made by others – as a “Nash equilibrium.”

… Congress finally banned tobacco ads from television in January 1971. One year later, the total spent on cigarette advertising had fallen by over 25 percent. Yet tobacco revenues held steady. Thanks to the government, the equilibrium had been broken.

That is from The Perfect Bet: How Science and Math are Taking the Luck Out of Gambling by Adam Kucharski, a very readable book full of insights. It’s mostly about cases of physicists and mathematicians who have “beaten” (more often found slight edges) in roulette, poker, horse race betting, and sports gambling.

Kucharski is Sir Henry Dale Fellow in the Department of Infectious Disease Epidemiology at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine. Now there’s a job!