Steve Hely's Blog, page 35

May 19, 2022

Austin and Houston, Part Two

(working out the history on these two, here is part one)

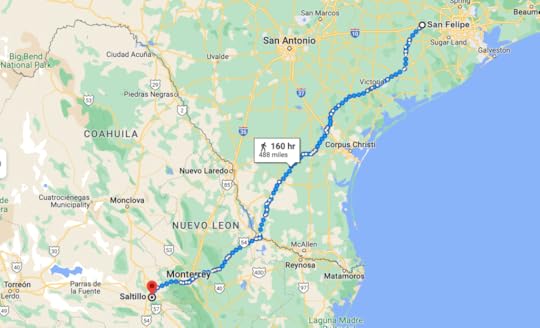

Sam Houston moved from Virginia to Tennessee with his widowed mother when he was thirteen, in 1806. Imagine what Virginia was like, let alone Tennessee, in 1806. At sixteen, Sam ran away and lived with the Cherokee Indians. He learned to speak their language, hunted with them in the woods. At age twenty he fought with the US Army in the War of 1812. Fighting Creek Indians under Andrew Jackson, he was wounded three times, and got his commander’s attention.

As part of Jackson’s political machine slash semi-dictatorship of Tennessee, Houston served two terms in Congress, then became governor. However, when his wife, Eliza Allen, left him after two months, Sam resigned as governor, went to live with the Cherokee again, took a Cherokee wife, got malaria, and become such an alcoholic mess that the Cherokee nicknamed him something like “Big Drunk” (or maybe it was like “Drunk Clown,” would love to hear from any Cherokee speakers/translators.)

On a mission to Washington for the Cherokee, Sam Houston beat up an Ohio congressman and was put on trial and convicted. (Francis Scott Key was his lawyer). The whole incident turned out to be good for Houston’s reputation, at least around Andrew Jackson’s crew, a rowdy bunch. Jackson welcomed Houston back into his circle.

Andrew Jackson hated the British. As a boy, Jackson had been captured by the British. The British had killed two of his brothers, and contributed to the death of his mother. He was worried his enemy Britain might get their hands on Texas from the newly independent nation of Mexico. The US had tried and failed to buy Texas from Mexico, and were left unsatisified.

Jackson decided to send Sam Houston down to Texas. “Stir up a rebellion, create opportunities for the US take this territory,” might’ve been the instruction. I don’t know, I wasn’t there.

Down in Mexico City, the capitol of newly free Mexico, there had been instability. Coups, counter-coups. During the uncertainty, the American settlers of Texas had pulled together two conventions, with the idea of trying to separate from the state of Coahuilla. To get Texas as its own (Mexican) state. The Texans felt underrepresented in the state legislature, plus the capital in Saltillo was too far away.

The conventions agreed to petition for statehood. The man appointed to take the results down to Mexico City was Stephen Austin.

Sam Houston, meanwhile, had arrived in Texas.

Part three to come.

(source on that photo, most of my info here coming from James L. Haley’s Passionate Nation: The Epic History of Texas).

May 11, 2022

should we all have done same?

May 8, 2022

Falklands anniversary

The Falklands War emphasized an important lesson of all international affairs: There is no one universal reality. Every nation has its own narrative, as we are witnessing yet again today, in the conduct toward Ukraine of Russian President Vladimir Putin.

Max Hastings writing in Bloomberg:

Nonetheless, given the excellence of the Argentine air force, Thatcher took a huge gamble by dispatching her fleet. Very little would have needed to go wrong for the British, and right for the junta, for an aircraft carrier to be sunk by Exocets, almost certainly with catastrophic consequences for the whole naval operation.

May 6, 2022

Austin and Houston

Stephen Austin’s father Moses, who knew something about lead mining, got a contract to roof the Virginia legislature building with lead. But he lost money on the deal and ended up almost broke.

The Austin family wandered into what was then Spanish territory in what’s now Missouri. Spanish and French claims in this area went back and forth during Napoleonic tumult in Europe. While the Austins were there, Napoleon ended up with it, but he needed money to fund various losses, including slaves taking over what’s now Haiti, so Napoleon sold these lands to Thomas Jefferson in the Louisiana Purchase, and the Austins became US citizens again.

Young Stephen was sent to boarding school in Connecticut and then college in Kentucky.

During his lonely years in boarding school, which he loathed, every letter from his father, which he tore open in a search for encouragement and affection, badgered him about how to become a great man.*

Meanwhile Moses Austin went broke again. His education complete, Stephen Austin left the family and became a judge in Arkansas.

Moses got the idea to head down to Texas, in what was then Spanish Mexico. He’d once been a Spanish citizen after all. Moses went to visit his son Stephen, who, though he was struggling himself, lent his dad fifty dollars, a horse, and a slave named Richmond.

A few years later, Stephen was in New Orleans. He wasn’t prospering. His dad wrote to him from Texas, and Stephen decided to go join him. By the time he got to the town of San Antonio, Stephen learned Mexico had become independent. He was no longer in Spanish territory but in the Mexican state of Coahuilla-Tejas.

Stephen Austin got an idea for a real estate scheme. He would become a developer. He would get land and give it to Americans who would move there. Stephen taught himself Spanish out of a book and went down to Mexico City to work out a contract. He got an amazing deal: he was offered 783,757 acres to distribute to 300 families. The head of each family would get 4,428 acres for ranching and 177 acres from farming.

The native Karankawa people had no say in any of this. Austin claimed these people were cannibals and should be killed on sight. He hired ten seasoned fighters and made them a company that would ride the range. This unit is sometimes considered the first version of the Texas Rangers.

At first Austin could sort of control who came to his colony. But it soon got out of hand. The area between the Sabine River and the Neches, “the Neutral Ground,” had never been under the control of any government. It had become a lawless wilderness zone and notorious hideout for murderers, convicts, and desperados of all types. Some of that element came into Austin’s zone. So too did the desperate or the ambitious from Tennessee, Louisiana, elsewhere. The word on Texas was out. “Going to Texas” became kind of a mania in the United States.

The government of Mexico tried to get a grip of the situation. They passed the Law of April 6, 1830, which banned any new American immigration into Mexican territory, including what’s now California and Texas. The law also banned the importing of slaves into Mexico. Austin, who had good relationships in Mexico City, managed to get an exemption on this one.

It was around this time that Sam Houston showed up.

Part two to follow.

* source for that quote and much of this info James L. Haley’s Passionate Nation: The Epic History Of Texas

April 29, 2022

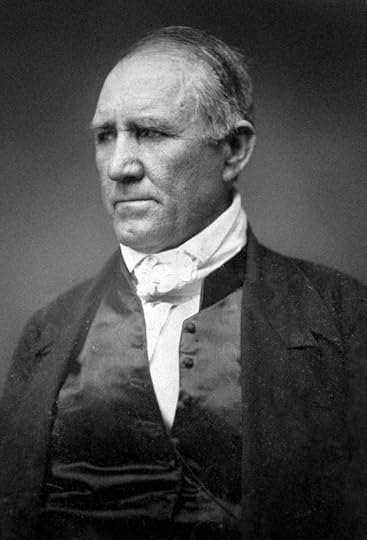

A Pirate Looks At Fifty by Jimmy Buffett

How many of Jimmy Buffett’s Big Eight (now the Big Ten) could you name? A few weeks ago I could’ve gotten two for sure, maybe three, I’m no Parrothead. When I thought of “Jimmy Buffett,” I thought of MW’s story of listening to his greatest hits on cassette on their way to family vacation, with his mom reaching over to frantically fast forward whenever “Why Don’t We Get Drunk and Screw” came around.

In Mile Marker Zero I loved the origin story of Jimmy Buffett: down on his luck in Nashville, goes to Miami for a gig, only to find either he or the club owner got the dates wrong. Stuck, he calls his friend Jerry Jeff Walker, whose girlfriend suggests they take the unexpected week and go down to Key West. When Jimmy Buffett sees the lifestyle there he knows he’s in the right place and never turns back.

The Margaritaville retirement community was profiled in The New Yorker. How many of the singer-songwriters of the ’70s have a retirement community based on their worldview? John Prine? Kris Kristofferson? Only one. At the Berkshire Hathaway annual meeting they sold a Jimmy Buffett boat. The man is a phenomenon. Why?

On a warm spring morning driving from Chapel HIll to Wilmington, NC in a rented Ford Escape armed with Sirius Satellite XM, I put on Parrothead Radio. They were playing a live concert from March 2001. “Before 9/11,” I thought. The contagious fun of this man came through, and the joy of the audience. It’s strange since, can you even really picture Jimmy Buffett? You can picture what kind of shirt he wears.

He’s in that kinda shirt on the cover of the mass market paperback of A Pirate Looks at Fifty. On a sunny beach obviously. Behind him is an enormous Albatross seaplane, the Hemisphere II.

This is a travel book, and a great one. I’d rank it up there with Bruce Chatwin’s The Songlines, which it references a few times. I bet more of A Pirate Looks at Fifty is true. I saved this book to read on the beach in Malibu – perfect setting. The book, leisurely, describes a trip around the Caribbean Sea to commemorate his fiftieth birthday, with stops in Grand Cayman, Costa Rica, Cartagena, St. Barts. A treasure map opens the book, you can follow the voyage. Along the way, Buffett tells of his rise and his adventures. He desired to be a Serious Southern Writer, but that wasn’t him. As a boy he was struck by a parade at Mobile Mardi Gras of Folly chasing Death. That was him. Catholicism plays a bigger role than you may suspect, with St. Louis Cathedral in New Orleans his home church, but plenty of bad behavior to balance the ledger. A friend at Auburn teaches him the D and C chords on a guitar. He busks on the corner of Chartres and Conti in New Orleans.

My talent came in working an audience.

Buffett begins the book with four hundred words summing up his life to present. An excerpt:

I signed a record deal, got married, moved to Nashville, had my guitars stolen, bought a Mercedes, worked at Billboard magazine, put out my first album, went broke, met Jerry Jeff Walker, wrecked the Mercedes, got divorced, and moved to Key West. I sang and worked on a fishing boat, went totally crazy, did a lot of dope, met the right girl, made another record, had a hit, bought a bought, and sailed away to the Caribbean.

Having brought us up to speed, he gets going. This is a memoir more of flying and fishing than of music. Buffett is a pilot, and recounts many adventures in the air, usually flying somewhere to fish or surf.

In looking back, I see there wasn’t that much difference between Jimi Hendrix playing “The Star-Spangled Banner at dawn at Woodstock and Jimmy Stewart playing Charles Lindbergh in “The Spirit of St. Louis.”

Memorable meals are described: cucumber and tomato sandwiches at the brassiere on the Trocadero in Paris for example. And bars: Buck Forty Nine, New Orleans; Trade Winds, St. Augustine; The Hub Pub Club, Boone NC; Big Pine Inn; The Hangout, Gulf Shores; The Vapors, Biloxi; Le Select, St. Barts.

Of a visit to paintings of Winslow Homer and Frederick Edward Church:

I can’t put the feeling into words; the closest I can come is to say that the sights and sounds of such things may enter the body through the senses but they find their way to the heart, and that is what art is really about.

Buffett says:

Anyone bellying up to a bar with a few shots of tequila swimming around the bloodstream can tell a story. The challenge is to wake up the next day and carve through the hangover minefield and a million other excuses and be able to cohesively get it down on paper.

Mission accomplished.

April 21, 2022

How To Be Rich by J. Paul Getty

Couldn’t resist purchasing this handsome volume in the bookstore of the Getty Center (cheers to MLo for the invitation). I like that the title isn’t “How To Get Rich” but “How to BE Rich.”

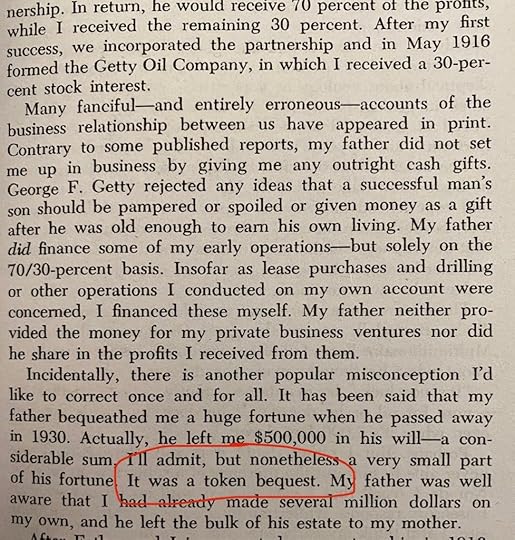

On page 2 he gives away one of the formulas: have a rich dad!

I’ll report back when I finish the volume. First: Jimmy Buffett’s autobiography.

April 20, 2022

More on sugar ruination

Reading up on the Pintupi Nine, a band of Australian Aboriginal people who walked out of the desert and encountered white people and their creations for the first time in 1984. More evidence on the power of sugar over the human mind:

McMahon did not want to put the group under any pressure to join the community, but he witnessed the moment they were persuaded. “It was unthinkable that they would stay out there because the modern world was so seductive. One of the fellows suggested, ‘Give them a taste of the sugar and they’ll be in for sure.'”

Indeed, the taste of sugar had a big impact on the Pintupi Nine and it is this aspect of their story which now animates them most. “I tasted the sugar, we didn’t know what it was, but it was so sweet. I tasted the sugar and it tasted so sweet – like the Kulun Kulun flower. My mother tasted it and it was so sweet. It was good,” says Warlimpirrnga.

That was that for bush life.

April 18, 2022

I am in a game

the game is very very easy if you have the right lessons in your mind.

Buffett says that to succeed at the game you need an IQ of about 120, but more than that is a hinderance.

Nothing shocking in Warren Buffett’s interview with Charlie Rose if you are a Buffett student. He drinks a Coke. That this interview exists is perhaps the most interesting thing: Charlie Rose is back? In this form? It’s not shot like Charlie’s PBS show.

Could this room be more generic?

Warren:

I think about what the company’s gonna be worth in 10-12 years.

and:

most of them [Berkshire investors] give it away when they get through

What does “get through” mean here? Die?

Buffett mentions pitching some doctors at a place called The Hilltop House in Omaha. Sadly it no longer exists, I find this photo of it on the post “I Wish I Could Have Gone To: Hilltop House” on MyOmahaObsession and I share the sentiment.

April 17, 2022

Confederate Surrender Day

Everybody knows about Appomattox, Lee and Grant, that whole story. But the larger Confederate surrender began on April 17, 1865, when Joseph Johnston met William Tecumseh Sherman near Durham, North Carolina. They met at the Bennett farmhouse, and after a few days of negotiation, 89,270 or so Confederate soldiers surrendered.

Some years later, John Sergeant Wise, a former Confederate officer whose father had been a Confederate general, went with a friend to visit Johnston.

One cold winter night about 1880, Captain Edwin Harvie, of General Johnston’s staff, invited me to join him in a call upon the general, who was then living in Richmond. Harvie was one of his pets, and we were promptly admitted to his presence. He sat in an armchair in his library, dressed in a flannel wrapper, and was suffering from an influenza. By his side, upon a low stool, stood a tray with whiskey, glasses, spoons, sugar, lemon, spice, and eggs. At the grate a footman held a brass teakettle of boiling water. Mrs. Johnston was preparing hot Tom-and-Jerry for the old gentleman, and he took it from time to time with no sign of objection or resistance. It was snowing outside, and the scene within was very cosy. As I had seen him in public, General Johnston was a stiff, uncommunicative man, punctilious and peppery, as little fellows like him are apt to be. He reminded minded me of a cock sparrow, full of self- consciousness, and rather enjoying a peck at his neighbor.

Johnston told Wise and his friend an anecdote about the surrendering, which Wise recorded in his book, The End of an Era.

Johnston had known Sherman well in the United States army. Their first interview near Greensboro resulted in an engagement to meet for further discussion the following day. As they were parting, Johnston remarked: “By the way, Cumps, Breckinridge, our Secretary of War, is with me. He is a very able fellow, and a better lawyer than any of us. If there is no objection, I will fetch him along to-morrow.”

Sherman didn’t like that idea, not recognizing any rebel “Secretary of War,” but agreed to allow Breckinridge to come in his capacity as a Confederate general.

The next day, General Johnston, accompanied by Major-General Breckinridge and others, was at the rendezvous before Sherman.

“You know how fond of his liquor Breckinridge was?” added General Johnston, as he went on with his story. “Well, nearly everything to drink had been absorbed. For several days, Breckinridge had found it difficult, if not impossible, to procure liquor. He showed the effect of his enforced abstinence. He was rather dull and heavy that morning. Somebody in Danville had given him a plug of very fine chewing tobacco, and he chewed vigorously while we were awaiting Sherman’s coming. After a while, the latter arrived. He bustled in with a pair of saddlebags over his arm, and apologized for being late. He placed the saddlebags carefully upon a chair. Introductions followed, and for a while General Sherman made himself exceedingly agreeable. Finally, some one suggested that we had better take up the matter in hand.

” ‘Yes,’ said Sherman; ‘but, gentlemen, it occurred to me that perhaps you were not overstocked with liquor, and I procured some medical stores on my way over. Will you join me before we begin work?'”

General Johnston said he watched the expression of Breckinridge at this announcement, and it was beatific. Tossing his quid into the fire, he rinsed his mouth, and when the bottle and the glass were passed to him, he poured out a tremendous drink, which he swallowed with great satisfaction. With an air of content, he stroked his mustache and took a fresh chew of tobacco.

Then they settled down to business, and Breckinridge never shone more brilliantly than he did in the discussions which followed. He seemed to have at his tongue’s end every rule and maxim of international and constitutional law, and of the laws of war, – international wars, civil wars, and wars of rebellion. In fact, he was so resourceful, cogent, persuasive, learned, that, at one stage of the proceedings, General Sherman, when confronted by the authority, but not convinced by the eloquence or learning of Breckinridge, pushed back his chair and exclaimed: “See here, gentlemen, who is doing this surrendering anyhow? If this thing goes on, you’ll have me sending a letter of apology to Jeff Davis.”

Afterward, when they were nearing the close of the conference, Sherman sat for some time absorbed in deep thought. Then he arose, went to the saddlebags, and fumbled for the bottle. Breckinridge saw the movement. Again he took his quid from his mouth and tossed it into the fireplace. His eye brightened, and he gave every evidence of intense interest in what Sherman seemed about to do.

The latter, preoccupied, perhaps unconscious of his action, poured out some liquor, shoved the bottle back into the saddle- pocket, walked to the window, and stood there, looking out abstractedly, while he sipped his grog.

From pleasant hope and expectation the expression on Breckinridge’s face changed successively to uncertainty, disgust, and deep depression. At last his hand sought the plug of tobacco, and, with an injured, sorrowful look, he cut off another chew. Upon this he ruminated during the remainder of the interview, taking little part in what was said.

After silent reflections at the window, General Sherman bustled back, gathered up his papers, and said: “These terms are too generous, but I must hurry away before you make me sign a capitulation. I will submit them to the authorities at Washington, and let you hear how they are received.” With that he bade the assembled officers adieu, took his saddlebags upon his arm, and went off as he had come.

General Johnston took occasion, as they left the house and were drawing on their gloves, to ask General Breckinridge how he had been impressed by Sherman.

“Sherman is a bright man, and a man of great force,” replied Breckinridge, speaking with deliberation, “but,” raising his voice and with a look of great intensity, “General Johnston, General Sherman is a hog. Yes, sir, a hog. Did you see him take that drink by himself?”

General Johnston tried to assure General Breckinridge that General Sherman was a royal good fellow, but the most absent- minded man in the world. He told him that the failure to offer him a drink was the highest compliment that could have been paid to the masterly arguments with which he had pressed the Union commander to that state of abstraction.

“Ah!” protested the big Kentuckian, half sighing, half grieving, “no Kentucky gentleman would ever have taken away that bottle. He knew we needed it, and needed it badly.”

Wise had the opportunity to tell that story to Sherman later:

On one occasion, being intimate with General Sherman, I repeated it to him. Laughing heartily, he said: “I don’t remember it. But if Joe Johnston told it, it’s so. Those fellows hustled me so that day, I was sorry for the drink I did give them,” and with that sally he broke out into fresh laughter.

(wikipedia user Specious took that photo of the reconstructed Bennett Place)

April 13, 2022

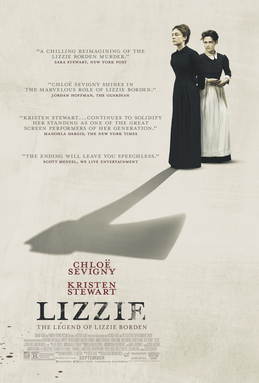

Lizzie (2018)

We were talking about ax* murders after a visit to the Villisca ax murder house in Villisca, Iowa. Someone asked me if I’d ever been to the Lizzie Borden house in Fall River, MA. I had to sheepishly admit I never had. Massachusetts is blessed with more cultural and natural attractions than southwestern Iowa, thus we didn’t have to fixate on one century-plus-old ax murder site, so I never made the pilgrimage.

Uncle-in-law Tony mentioned that there was a movie starring Kristen Stewart and Chloë Whatsername about the case. I was stunned, how could such a movie have passed me by?

Back home, I watched it immediately. I wouldn’t exactly race to see it, it’s a bit stylish and slow at times, but Kristen Stewart and Chloë Sevigny are fantastic in it. These are incredible actresses doing stunning work. The version of the case presented in the film (spoiler) seems somewhat plausible to me as a non-student: that Lizzie (Sevigny) and Irish housemaid Bridget Sullivan (Stewart) had a sexual relationship. Lizzie took the lead on the murdering, and Sullivan covered for her.

In Popular Crime, Bill James posits that Lizzie was innocent, or at least that she shouldn’t’ve been convicted, citing some timeline discrepancies. Lizzie had no blood splatter on her clothes. James dismisses the idea (presented vividly in the film) that she might’ve done the murders in the nude.

Again, this seems to be virtually impossible. First, for a Victorian Sunday school teacher, the idea of running around an occupied house naked in the middle of the day is almost more inconceivable than committing a couple of hatchet murders. Second, the only running water in the house was a spigot in the basement. If she had committed the murders in the nude, it is likely that there would have been bloody footprints leading to the basement – and there is no time to have cleaned them up.

I dunno, I think Victorians – should that term even apply in the USA? – were weirder and nudier than we may realize. And maybe there wouldn’t be bloody footprints, I’m no expert on blood splatterings and footprint cleanings. In my own life I’ve found you can clean up even a big mess in a hurry if you’re motivated. Even James concedes that it does seem Lizzie burned a dress in the days after the murders. This doesn’t worry him though and he refuses to charge it against Lizzie. He proposes no alternate solution to the case.

The famous rhyme is pretty strong propaganda. If you’re ever accused of a notorious murder, you’d be wise to hire the local jump rope kids to immediately put out a rhyme blaming one of the other suspects. It may have been too late in Lizzie’s case, but here’s what I might’ve tried:

A random peddler walking by,

Chopped the Bordens, don’t know why

or

Johnny Morse killed his brother-in-law,

Used an ax instead of a saw.

When he saw what he could do

He killed his brother-in-law’s wife too.

These are not as catchy. On the second one for instance you may need to add a footnote that Morse was brother to Andrew Borden’s deceased first wife, Lizzie’s mom.

True crime has never been a passion of mine, but I can see the appeal. You’re dealing with a certain set of known information which you can weight as you see fit, balanced with aspects that are epistemically (?) unknowable. In that way it’s a puzzle not unlike handicapping a horse race.

I’m reading Bill James (with Rachel McCarthy James) The Man from the Train now, centered on the Villisca murders. It’s very compelling. James is such an appealing writer, and he’s on to a good one here. One way or another, there was a staggering number of entire families murdered with an ax between 1890 and 1912. Something like 14-25 events with 59-94 victims. That is wild. In these ax murders, by the way, we’re talking about the blunt end of the ax. Lizzie or whoever did the Fall River murders as I understand it used the sharp side.

The people I spoke with in Villisca seemed more focused on possible local solutions, the Kelly and Jones theories in particular. Maybe they don’t want to admit that their crime, which did make their town famous, was just part of a horrible series, rather than a special and unique case. The Man From The Train put me in mind of the book Wisconsin Death Trip, which is nothing more than a compiling of psycho events from Wisconsin newspapers from about 1890-1900, awful suicides, burnings, poisonings, fits of insanity, etc., plus a collection of eerie photographs from that time and place. The thesis is that the US Midwest was having something like a collective mental breakdown during the late 19th century.

Anyway, if you like creepy lesbian psychodramas, Lizzie might be for you! The sound design is good on the creaks of an old wooden house.

* I’m using the spelling ax that is used on the Villisca house signage, although axe is more common in the USA