Henry Gee's Blog, page 8

December 28, 2022

What I Read In December

Richard Fortey: A Curious Boy It was the author himself who recommended this book to me, as he said — and I hope, if he reads this, he won’t mind my saying so — that aspects of his book reminded him of me. And it did. It was uncanny. The geeky boy who loved nothing better than to roam the countryside; to spend time alone with collections of fossils, or insects, but who loved art, and literature, and music, ideas; was allergic to virtually every sport (Fortey played Tiddlywinks for Cambridge University: I represented the University at Scrabble); and who was drawn, ineluctably, into science. And writing about science. And even the same areas of science. Fortey’s Life: An Unauthorised Biography (perhaps his best known book) plows a furrow adjacent to my own writings. However, I suspect that Fortey and I are less long-lost brothers than exemplars of a type: variants of the same species. There are, to be sure, many people out there who will see themselves in this book, whether or not they became scientists — or, as Fortey nearly did, a historian of science. Or a poet. A joyous read.

Richard Fortey: A Curious Boy It was the author himself who recommended this book to me, as he said — and I hope, if he reads this, he won’t mind my saying so — that aspects of his book reminded him of me. And it did. It was uncanny. The geeky boy who loved nothing better than to roam the countryside; to spend time alone with collections of fossils, or insects, but who loved art, and literature, and music, ideas; was allergic to virtually every sport (Fortey played Tiddlywinks for Cambridge University: I represented the University at Scrabble); and who was drawn, ineluctably, into science. And writing about science. And even the same areas of science. Fortey’s Life: An Unauthorised Biography (perhaps his best known book) plows a furrow adjacent to my own writings. However, I suspect that Fortey and I are less long-lost brothers than exemplars of a type: variants of the same species. There are, to be sure, many people out there who will see themselves in this book, whether or not they became scientists — or, as Fortey nearly did, a historian of science. Or a poet. A joyous read. Edward Gibbon: The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, (vol. 8, Folio Society Edition). In this, the final volume, we see the Byzantine Empire down on its uppers. Reduced to Constantinople and its environs, with a small scattering of Aegean Islands and enclaves, the final conquest was only a matter of time. Quite a lot of time, as it turned out, as the Turks were perpetually distracted by their own internal wrangling; pressures from outside, notably the incursions of Genghis Khan and Tamerlane; and more prosaic matters. For example, the conquests of the Sultan Bajazet were brought up short

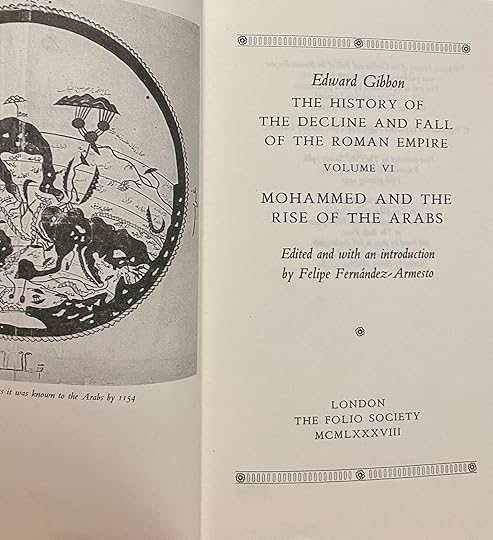

Edward Gibbon: The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, (vol. 8, Folio Society Edition). In this, the final volume, we see the Byzantine Empire down on its uppers. Reduced to Constantinople and its environs, with a small scattering of Aegean Islands and enclaves, the final conquest was only a matter of time. Quite a lot of time, as it turned out, as the Turks were perpetually distracted by their own internal wrangling; pressures from outside, notably the incursions of Genghis Khan and Tamerlane; and more prosaic matters. For example, the conquests of the Sultan Bajazet were brought up short

not by the miraculous interposition of the apostle [St Peter], not by a crusade of the Christian powers, but by a long and painful fit of the gout.

The Byzantines did themselves no favours by ceaseless internal scheming and schism. Slowly, their ability to command resources dwindled. When one Byzantine prince presented to his inamorata a crown of diamonds and pearls, ‘he informed her, with a smile,

that this precious ornament arose from the sale of the eggs of his innumerable poultry.

At times, the relic of the Roman Empire maintained a precarious existence thanks to the munificence of the Turks themselves (to whom they paid tribute); the energies of the Italian maritime republics, particularly Genoa, which maintained a sizeable presence in Constantinople until its fall in 1453; or simply by playing one antagonist off against another. Finally, the Byzantines attempted to save themselves by overtures to the West: that a reunification of their two divergent churches might be backed up by western arms to stay the Turks. Various synods were convened. All ended in failure.

Perhaps the key to the final fall of Constantinople was the invention of gunpowder, for the use of which the Turks created the most immense cannon (reminiscent to news watchers of a certain age of the supposed ‘Supergun’ of the Late Saddam Hussein, despot of Iraq.) Gibbon is not impressed:

If we contrast the rapid progress of this mischievous discovery with the slow and laborious advances of reason, science, and the arts of peace, a philosopher, according to his temper, will laugh or weep at the folly of mankind.

Gibbon’s description of the fall of Constantinople is gripping.

From the lines, the galleys, and the bridge, the Ottoman artillery thundered on all sides; and the camp and city, the Greeks and the Turks, were involved in a cloud of smoke, which could only be dispelled by the final deliverance or destruction of the Roman Empire.

The final chapters form a kind of coda, in which Gibbon examines the state and governance of Rome itself, from the twelfth to the fifteenth centuries. In doing so he comes full circle, considering Rome as a city state, with all its petty wrangles, and with even less of a reach than the infant Roman Republic.

What can one say, finally, about this 2,900-page epic? I found it as stately, well-proportioned and elegant as a Georgian mansion. As someone said of Wagner, it has marvellous moments, and rather tedious quarters of an hour — but the overall effect is spectacular. To be sure, it wouldn’t do for every day. Rather like turning up at the supermarket to do the weekly shop in a chauffeur-driven Rolls. But as a prose stylist, Gibbon is (in my opinion) unmatched.

Chris Beckett: Beneath the World, a Sea ChrisBeckett is one of the most original SF authors writing today. His novel Dark Eden, about a group of people descended from astronauts stranded on an alien planet, was one of the best SF novels I’ve read in years. Beneath the World, a Sea, conjures similar atmospheres, though in a very different setting. Ben Ronson is a detective sent to the Submundo Delta, a strange region of Brazil, cut off from the rest of the world, with an unearthly flora and fauna. He is there to investigate the killings of the duendes, the Submundo’s weird indigenes, which have a disturbing psychic effect on anyone who gets close to them. It’s a bit Heart of Darkness, and asks penetrating questions about our identities as people. Who are we, really, once we have stripped away the learned reactions to the rest of the world, the personae we are forced to adopt in order to get along in society?

Chris Beckett: Beneath the World, a Sea ChrisBeckett is one of the most original SF authors writing today. His novel Dark Eden, about a group of people descended from astronauts stranded on an alien planet, was one of the best SF novels I’ve read in years. Beneath the World, a Sea, conjures similar atmospheres, though in a very different setting. Ben Ronson is a detective sent to the Submundo Delta, a strange region of Brazil, cut off from the rest of the world, with an unearthly flora and fauna. He is there to investigate the killings of the duendes, the Submundo’s weird indigenes, which have a disturbing psychic effect on anyone who gets close to them. It’s a bit Heart of Darkness, and asks penetrating questions about our identities as people. Who are we, really, once we have stripped away the learned reactions to the rest of the world, the personae we are forced to adopt in order to get along in society?

Yuval Noah Harari: Homo Deus I found this book quite infuriating – possibly because the subtitle (‘A Brief History of Tomorrow’) is misleading, and also because I found it thoroughly overwritten. It does say some things about the future, but you have to wade through 400 pages of tendentious moral philosophy to get to it, after which it proposes a kind of new religion called ‘Dataism’ in which information flow is everything and individual humans are redundant. In doing so it proposes a number of axioms, some of which are problematic. The idea, first, that organisms can be reduced to ‘algorithms’ is twenty years out of date. The second, that there really is no individual ‘self’ is plainly wrong. Although the story the brain tells us about the world is incontestably biased and demonstrably inconsistent, it is a story, and no worse for all that. But the most frustrating thing about this book is that it has been written without an editor. Overstuffed and repetitive, it would have been entertaining at a third the length.

Yuval Noah Harari: Homo Deus I found this book quite infuriating – possibly because the subtitle (‘A Brief History of Tomorrow’) is misleading, and also because I found it thoroughly overwritten. It does say some things about the future, but you have to wade through 400 pages of tendentious moral philosophy to get to it, after which it proposes a kind of new religion called ‘Dataism’ in which information flow is everything and individual humans are redundant. In doing so it proposes a number of axioms, some of which are problematic. The idea, first, that organisms can be reduced to ‘algorithms’ is twenty years out of date. The second, that there really is no individual ‘self’ is plainly wrong. Although the story the brain tells us about the world is incontestably biased and demonstrably inconsistent, it is a story, and no worse for all that. But the most frustrating thing about this book is that it has been written without an editor. Overstuffed and repetitive, it would have been entertaining at a third the length.

November 30, 2022

Apotheosis

You’ll both be aware by now that my recent tome was shortlisted for the Royal Society Insight Investment Science Book Prize for 2022. You’ll recall that my book kept some mighty company, so imagine my surprise and delight when, at a ceremony on 29 November, that it was voted the winner. Please head over to the book’s official website for all the hoopla.

You’ll both be aware by now that my recent tome was shortlisted for the Royal Society Insight Investment Science Book Prize for 2022. You’ll recall that my book kept some mighty company, so imagine my surprise and delight when, at a ceremony on 29 November, that it was voted the winner. Please head over to the book’s official website for all the hoopla.

November 28, 2022

What I Read In November

Frans de Waal: Different A salutary and timely corrective to all those engaged in debates about sex and gender that nothing makes sense except in the light of evolution. Humans are animals, and so are our various itches and scratches. The problem, says distinguished primatologist de Waal, is that humans cannot help but put things into binary categories. ‘Sex’ is biological and for reproduction, and ‘gender’ is a cultural overlay. But chimpanzees (the common or perhaps less frequent variety) and bonobos (what used to be called pygmy chimpanzees) are two species, equally closely related to us, neither of which have language, and in whose universe the ideas of sex and reproduction cannot possibly be connected. Chimpanzees are male-dominated (mostly) and violent (sometimes); bonobos are female-dominated and have sex, in various positions, as a way of saying ‘hello’. Because animals have no language, and at the same time no sense that sex and reproduction are connected, there are likewise no simple lines to be drawn between sex for procreation and sex simply as something pleasurable to do, which logically leads to a rather relaxed idea of gender. This should be absolutely required reading for any person in a gender-studies program. The problem is that when they finish it they might realise that they don’t really have a program to go back to, because de Waal has explained everything. And I mean everything. De Waal takes conservatives and progressive attitudes to sex and gender to task with brio, and does so in such a pleasant, well-meaning, enlightened way that no-one could possibly be offended. Could they? Shortlisted for the Royal Society Science Book Prize 2022 (DISCLAIMER: as is one of mine).

Frans de Waal: Different A salutary and timely corrective to all those engaged in debates about sex and gender that nothing makes sense except in the light of evolution. Humans are animals, and so are our various itches and scratches. The problem, says distinguished primatologist de Waal, is that humans cannot help but put things into binary categories. ‘Sex’ is biological and for reproduction, and ‘gender’ is a cultural overlay. But chimpanzees (the common or perhaps less frequent variety) and bonobos (what used to be called pygmy chimpanzees) are two species, equally closely related to us, neither of which have language, and in whose universe the ideas of sex and reproduction cannot possibly be connected. Chimpanzees are male-dominated (mostly) and violent (sometimes); bonobos are female-dominated and have sex, in various positions, as a way of saying ‘hello’. Because animals have no language, and at the same time no sense that sex and reproduction are connected, there are likewise no simple lines to be drawn between sex for procreation and sex simply as something pleasurable to do, which logically leads to a rather relaxed idea of gender. This should be absolutely required reading for any person in a gender-studies program. The problem is that when they finish it they might realise that they don’t really have a program to go back to, because de Waal has explained everything. And I mean everything. De Waal takes conservatives and progressive attitudes to sex and gender to task with brio, and does so in such a pleasant, well-meaning, enlightened way that no-one could possibly be offended. Could they? Shortlisted for the Royal Society Science Book Prize 2022 (DISCLAIMER: as is one of mine).

Richard Osman: The Bullet that Missed by way of temporary respite from the Roman Empire I dived into this, the third in the series of whodunits by That Man On The Telly. It follows directly on from The Man Who Died Twice which in turn follows The Thursday Murder Club, and if you haven’t read any of these you are missing out. The Thursday Murder Club is an unlikely quartet of pensioners living in a retirement village that solves murders. They are not afraid to get their hands dirty themselves. Affectionate, warm, and killingly funny, The Bullet That Missed is the best of the three so far in its gloriously slick, twisty and turny way.

Richard Osman: The Bullet that Missed by way of temporary respite from the Roman Empire I dived into this, the third in the series of whodunits by That Man On The Telly. It follows directly on from The Man Who Died Twice which in turn follows The Thursday Murder Club, and if you haven’t read any of these you are missing out. The Thursday Murder Club is an unlikely quartet of pensioners living in a retirement village that solves murders. They are not afraid to get their hands dirty themselves. Affectionate, warm, and killingly funny, The Bullet That Missed is the best of the three so far in its gloriously slick, twisty and turny way.

Edward Gibbon: The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, vol. 7 (Folio Society Edition) The greatness of Rome has long sunk into obscurity, and the successor, in Constantinople, is going the same way. In this, the penultimate volume, we read how the tide of Islamic expansion reached its highest and began to recede; how new invaders — Normans, Hungarians, Bulgarians — interrupted the course of life in Europe; and, most of all, of the Crusades, a series of events that epitomises heroic failure. Gibbon first wonders at how the seemingly inexorable rise of Islam was finally checked, and concludes that it was the result of its own internal factionalism. Had it stayed together, Islam might have gone much further, a reflection that is the source of one of the most famous quotes from this most quotable of authors:

Edward Gibbon: The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, vol. 7 (Folio Society Edition) The greatness of Rome has long sunk into obscurity, and the successor, in Constantinople, is going the same way. In this, the penultimate volume, we read how the tide of Islamic expansion reached its highest and began to recede; how new invaders — Normans, Hungarians, Bulgarians — interrupted the course of life in Europe; and, most of all, of the Crusades, a series of events that epitomises heroic failure. Gibbon first wonders at how the seemingly inexorable rise of Islam was finally checked, and concludes that it was the result of its own internal factionalism. Had it stayed together, Islam might have gone much further, a reflection that is the source of one of the most famous quotes from this most quotable of authors:

Perhaps the interpretation of the Koran would now be taught in the schools of Oxford, and her pulpits might demonstrate to a circumcised people the sanctity and truth of the revelation of Mohammed.

Despite numerous assaults, Constantinople hung on by the skin of its teeth: but, asks Gibbon, to what end? ‘In the revolution of ten centuries’, he writes,

not a single discovery was made to exalt the dignity or promote the happiness of mankind. Not a single idea has been added to the speculative systems of antiquity, and a succession of patient disciples became in their turn the dogmatic teachers of the next servile generation.

Where the first legions of the Prophet failed, the Seljuk Turks nearly succeeded, and indeed wrested from the Roman orbit, after a millennium, the Levant, including the holy places. At first, lucrative tourism allowed for pilgrimages to be made, but it entered the mind of one Peter the Hermit, a native of Amiens, that the Holy Land should be reclaimed for Christ. He returned from Jerusalem ‘an accomplished fanatic’, and found many willing ears, as ‘he excelled in the popular madness of the times’ — and so the First Crusade was born. Not that the motives of the crusaders were wholly or even partly honourable. Crusaders were granted relief from all their sins, unleashing a tide of licensed yobbery on the peaceful nations of Europe.

At the voice of their pastor, the robber, the incendiary, the homicide, arose by thousands to redeem their souls by repeating on the infidels the same deeds which they had exercised against their Christian brethren; and the terms of atonement were eagerly embraced by offenders of every rank and denomination.

Although some of the crusaders held on to statelets in Syria and Palestine for a few decades, they were ultimately defeated and the result of a great deal of religious fervour, spilled blood, sack, pillage and rapine was – well, bupkes. The ultimate betrayal was the Fourth Crusade in which the impoverished Byzantine Emperor called on the West to push back the Turks from his beleaguered city, resulting in the conquest of Constantinople itself, and its rule for sixty years by a consortium of petty French barons and Venetian merchant princes.

One might have thought, opines Gibbon, wistfully, that a result of this peculiar episode might have had the benefit of the direct infusion of ancient Greek literature and philosophy into Latin, rather than its circuitous route via Arabic. But the crusades ‘appear to me to have checked rather than forwarded the maturity of Europe’, and

if the ninth and tenth centuries were the times of darkness, the thirteenth and fourteenth were the age of absurdity and fable.

It all amounted to a waste of human capital on so monumental a scale that it makes the shame of it quite meaningless. But perhaps one benefit might have been the beginnings of the loosening of the feudal system. If the flower of European chivalry mortgaged their estates only to kill and pillage and bleed and die for Christ in a far-off country, then

The conflagration which destroyed the tall and barren trees of the forest gave air and scope to the vegetation of the smaller and nutritive plants of the soil.

Rose Anne Kenny; Age Proof The world is greying, and rapidly, and in medicine there is perhaps no greater growth area than gerontology – the medical issues facing older people. But as gerontologist Kenny shows in this book, you are as old as you feel, and there are myriad ways to keep youthful, cheerful and in the peak of fun and brio. In truth, this is not really what I was expecting from a science book. Although it does contain a lot of science, it reads much more as a self-help manual. There is no real narrative arc, and one could probably benefit by treating it as one of those old-fashioned health encyclopaedias you’d dip into to discover this and that. It could have been fleshed out with a lot more anecdotes, such as the one about the woman whose heart stopped whenever her son-in-law told her a dirty joke (which reminded me, if not the author, of the famous Monty Python sketch about the joke that’s so funny that people hearing it died laughing). It would also have benefited from a more scrupulous edit, and — call me grumpy — a lot fewer exclamation marks! (Here are a few more!!!) Shortlisted for the Royal Society Science Book Prize 2022 (a contest in which I also have a canine).

Rose Anne Kenny; Age Proof The world is greying, and rapidly, and in medicine there is perhaps no greater growth area than gerontology – the medical issues facing older people. But as gerontologist Kenny shows in this book, you are as old as you feel, and there are myriad ways to keep youthful, cheerful and in the peak of fun and brio. In truth, this is not really what I was expecting from a science book. Although it does contain a lot of science, it reads much more as a self-help manual. There is no real narrative arc, and one could probably benefit by treating it as one of those old-fashioned health encyclopaedias you’d dip into to discover this and that. It could have been fleshed out with a lot more anecdotes, such as the one about the woman whose heart stopped whenever her son-in-law told her a dirty joke (which reminded me, if not the author, of the famous Monty Python sketch about the joke that’s so funny that people hearing it died laughing). It would also have benefited from a more scrupulous edit, and — call me grumpy — a lot fewer exclamation marks! (Here are a few more!!!) Shortlisted for the Royal Society Science Book Prize 2022 (a contest in which I also have a canine).

Peter Stott: Hot Air If ever there was a book too make you think, this is it. But beware – it will also make you angry. Angry at the wicked, selfish, and, it has to be said, evil people and institutions that seek to undermine, traduce, vilify and even criminalise the pursuit of science, for political ends, and in the service of powerful vested interests. Peter Stott comes across as the typical mild-mannered scientist who, in the early 1990s, found himself on the ground floor of the emerging science of climate change. As a scientist at the UK Meteorological Office, he has been at the sharp end of the research that shows, increasingly, and now unquestionably, that the world’s climate is changing, very rapidly, as a direct consequence of human activities. But he has also been at the sharp end of well-funded efforts to undermine the credibility of the science and the scientists themselves, aided at times by cackhanded and ill-informed news editors who wheel out long-discredited climate-change ‘sceptics’ for the sake of what they call ‘balance’. Thankfully the balance has shifted, for now, to embrace the reality of anthropogenic climate change – but for how long? Jair Bolsonaro was bested in Brazil by only a whisker, and if Trump succeeds in becoming US President again, the world might once again switch to the dark side. Shortlisted for the Royal Society Science Book Prize of 2022 (and, as you know by now, I also have a dog in that fight).

Peter Stott: Hot Air If ever there was a book too make you think, this is it. But beware – it will also make you angry. Angry at the wicked, selfish, and, it has to be said, evil people and institutions that seek to undermine, traduce, vilify and even criminalise the pursuit of science, for political ends, and in the service of powerful vested interests. Peter Stott comes across as the typical mild-mannered scientist who, in the early 1990s, found himself on the ground floor of the emerging science of climate change. As a scientist at the UK Meteorological Office, he has been at the sharp end of the research that shows, increasingly, and now unquestionably, that the world’s climate is changing, very rapidly, as a direct consequence of human activities. But he has also been at the sharp end of well-funded efforts to undermine the credibility of the science and the scientists themselves, aided at times by cackhanded and ill-informed news editors who wheel out long-discredited climate-change ‘sceptics’ for the sake of what they call ‘balance’. Thankfully the balance has shifted, for now, to embrace the reality of anthropogenic climate change – but for how long? Jair Bolsonaro was bested in Brazil by only a whisker, and if Trump succeeds in becoming US President again, the world might once again switch to the dark side. Shortlisted for the Royal Society Science Book Prize of 2022 (and, as you know by now, I also have a dog in that fight).

November 20, 2022

Incompletion [2]

I regret to say that today I have had to do something I almost never do, mostly because I really hate doing it – and that’s abandon a book I had been reading. And I had got almost all the way through, too. I know, I know, this is like the person swimming the Channel who abandons the quest just as they get within sight of the further shore. But I really couldn’t muster the force to continue. I appreciate that many others will enjoy the book. Indeed, there were parts I found enjoyable – even instructive – but it seemed so poorly written, so ill-constructed, so flat, so full of error, with neither structure nor cadence, that I found the prospect of continuing just not worth the effort. No, I am not telling you which book it was.

The last time I abandoned a book, the tome in question was 2121, a dystopia by Susan Greenfield, which I gave up on page 19 (though I was sure I’d abandon it on page 12 – I just read a few pages more because I felt I had to make sure) which combined very poor characterisation with a seemingly total disregard for the entire canon of science fiction that the author sought to enter. Since then I have always always always finished what I start.

I fear I might have been spoiled. One book I shall surely finish is Gibbon’s Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire (I am 7/8ths through its 2,900-page extent). I started earlier this year and it has been a revelation. The prose is so lucid; the arguments so well constructed; the tone so measured (yet not without biting humour in places). Sure, it’s no potboiler, and requires concentration, but it is so well-wrought that most other things seem slack and ill-made by comparison. And I am listening to an audiobook version of The Lord of the Rings, narrated by Andy Serkis, on my daily dog walks. Tolkien, a philologist by profession, a poet by avocation, took infinite care over the words he used, because he realised that words have meaning; they have nuance; they have history; they have impact. They deserve respect.

And yet I feel terribly guilty. About not finishing a book, I mean. I think I need to calm down with a collection of SF short stories. Or just stare at the wall.

Incompletion

I regret to say that today I have had to do something I almost never do, mostly because I really hate doing it – and that’s abandon a book I had been reading. And I had got almost all the way through, too. I know, I know, this is like the person swimming the Channel who abandons the quest just as they get within sight of the further shore. But I really couldn’t muster the force to continue. I appreciate that many others will enjoy the book. Indeed, there were parts I found enjoyable – even instructive – but it seemed so poorly written, so ill-constructed, so flat, so full of error, with neither structure nor cadence, that I found the prospect of continuing just not worth the effort. No, I am not telling you which book it was.

The last time I abandoned a book, the tome in question was 2121, a dystopia by Susan Greenfield, which I gave up on page 19 (though I was sure I’d abandon it on page 12 – I just read a few pages more because I felt I had to make sure) which combined very poor characterisation with a seemingly total disregard for the entire canon of science fiction that the author sought to enter. Since then I have always always always finished what I start.

I fear I might have been spoiled. One book I shall surely finish is Gibbon’s Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire (I am 7/8ths through its 2,900-page extent). I started earlier this year and it has been a revelation. The prose is so lucid; the arguments so well constructed; the tone so measured (yet not without biting humour in places). Sure, it’s no potboiler, and requires concentration, but it is so well-wrought that most other things seem slack and ill-made by comparison. And I am listening to an audiobook version of The Lord of the Rings, narrated by Andy Serkis, on my daily dog walks. Tolkien, a philologist by profession, a poet by avocation, took infinite care over the words he used, because he realised that words have meaning; they have nuance; they have history; they have impact. They deserve respect.

And yet I feel terribly guilty. About not finishing a book, I mean. I think I need to calm down with a collection of SF short stories. Or just stare at the wall.

October 31, 2022

In The Air Tonight [6]

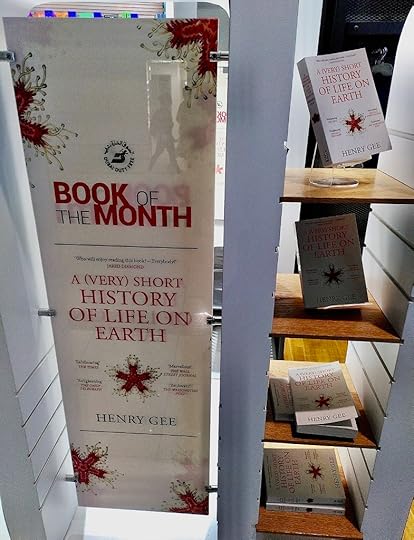

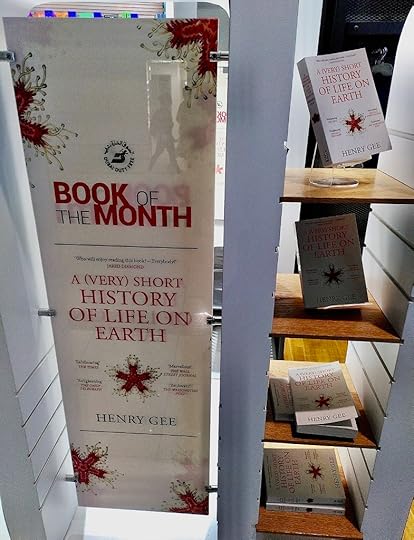

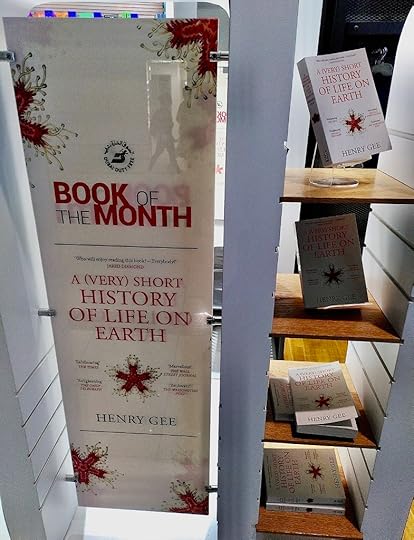

The dream of any author is having their books on sale in the duty-free shops at major airports, alongside the generic thrillers and self-help manuals. Imagine my pleasure therefore at receiving this snap taken by Professor F___ W___ of Copenhagen, who spotted A (Very) Short History of Life on Earth in field conditions, in a duty-free shop at Dubai Airport. Even more amazingly, the store had displayed the book (my book, noch) as its monthly promotional selection. This isn’t just any old airport — it’s a major international hub. And it’s not just shoved on a shelf — it has a big display all to itself. This really has to be the apotheosis of my zenith this week. Now, none of this happens by accident. When you see books displayed prominently in a bookstore window, or at a point of sale, you can be sure that the publisher has paid for the privilege. Clearly my publisher — in concert with the local sales force — felt it worth while. As for me, I can’t help shake the image that in the air tonight, in planes bound for destinations as varied as Perth and Panama, Detroit and Denpasar, people will be up late reading my book, while passengers round about sleep the hours quietly away.

The dream of any author is having their books on sale in the duty-free shops at major airports, alongside the generic thrillers and self-help manuals. Imagine my pleasure therefore at receiving this snap taken by Professor F___ W___ of Copenhagen, who spotted A (Very) Short History of Life on Earth in field conditions, in a duty-free shop at Dubai Airport. Even more amazingly, the store had displayed the book (my book, noch) as its monthly promotional selection. This isn’t just any old airport — it’s a major international hub. And it’s not just shoved on a shelf — it has a big display all to itself. This really has to be the apotheosis of my zenith this week. Now, none of this happens by accident. When you see books displayed prominently in a bookstore window, or at a point of sale, you can be sure that the publisher has paid for the privilege. Clearly my publisher — in concert with the local sales force — felt it worth while. As for me, I can’t help shake the image that in the air tonight, in planes bound for destinations as varied as Perth and Panama, Detroit and Denpasar, people will be up late reading my book, while passengers round about sleep the hours quietly away.

In The Air Tonight [4]

The dream of any author is having their books on sale in the duty-free shops at major airports, alongside the generic thrillers and self-help manuals. Imagine my pleasure therefore at receiving this snap taken by Professor F___ W___ of Copenhagen, who spotted A (Very) Short History of Life on Earth in field conditions, in a duty-free shop at Dubai Airport. Even more amazingly, the store had displayed the book (my book, noch) as its monthly promotional selection. This isn’t just any old airport — it’s a major international hub. And it’s not just shoved on a shelf — it has a big display all to itself. This really has to be the apotheosis of my zenith this week. Now, none of this happens by accident. When you see books displayed prominently in a bookstore window, or at a point of sale, you can be sure that the publisher has paid for the privilege. Clearly my publisher — in concert with the local sales force — felt it worth while. As for me, I can’t help shake the image that in the air tonight, in planes bound for destinations as varied as Perth and Panama, Detroit and Denpasar, people will be up late reading my book, while passengers round about sleep the hours quietly away.

The dream of any author is having their books on sale in the duty-free shops at major airports, alongside the generic thrillers and self-help manuals. Imagine my pleasure therefore at receiving this snap taken by Professor F___ W___ of Copenhagen, who spotted A (Very) Short History of Life on Earth in field conditions, in a duty-free shop at Dubai Airport. Even more amazingly, the store had displayed the book (my book, noch) as its monthly promotional selection. This isn’t just any old airport — it’s a major international hub. And it’s not just shoved on a shelf — it has a big display all to itself. This really has to be the apotheosis of my zenith this week. Now, none of this happens by accident. When you see books displayed prominently in a bookstore window, or at a point of sale, you can be sure that the publisher has paid for the privilege. Clearly my publisher — in concert with the local sales force — felt it worth while. As for me, I can’t help shake the image that in the air tonight, in planes bound for destinations as varied as Perth and Panama, Detroit and Denpasar, people will be up late reading my book, while passengers round about sleep the hours quietly away.

In The Air Tonight

The dream of any author is having their books on sale in the duty-free shops at major airports, alongside the generic thrillers and self-help manuals. Imagine my pleasure therefore at receiving this snap taken by Professor F___ W___, who spotted A (Very) Short History of Life on Earth in field conditions, in a duty-free shop at Dubai Airport. Even more amazingly, the store had displayed the book (my book, noch) as its monthly promotional selection. This really has to be the apotheosis of my zenith this week. Thank you Dubai, and Professor F___ W___!

The dream of any author is having their books on sale in the duty-free shops at major airports, alongside the generic thrillers and self-help manuals. Imagine my pleasure therefore at receiving this snap taken by Professor F___ W___, who spotted A (Very) Short History of Life on Earth in field conditions, in a duty-free shop at Dubai Airport. Even more amazingly, the store had displayed the book (my book, noch) as its monthly promotional selection. This really has to be the apotheosis of my zenith this week. Thank you Dubai, and Professor F___ W___!

October 29, 2022

What I Read In October

Shon Faye: The Transgender Issue I was alerted to this by Stephen: it was something of an eye-opener. From the amount of newsprint and airtime devote to trans people, you’d think they were engaged in a full-scale invasion. Shon Faye shows that they constitute a near-negligible proportion of the population and are oppressed in every way by a majority that would rather they didn’t exist and will go some considerable way to fulfilling that desire. Marginalised, they, like many other minorities, struggle to find employment and are over-represented in the gig economy and sex work. Demonised by the right-leaning press as woke snowflakes that want to shut down free speech: exhibited by the left-leaning press largely as a problem for feminism, the regular person is entitled to ask what’s really going on — and Shon Faye tells us. (Aside: I was brought up by my mother, a WI stalwart, listening to Woman’s Hour on the radio. She hadn’t listened to it for years, she said, as it had been more concerned these days with gender politics than issues that were, to her, of greater interest. I switched on and was immediately pitched into a furious argument between a radical feminist and a trans person. In the old days, I thought, audiences could be titillated by bear-baiting. I switched off). The fact is that nobody wants to be trans as a kind of woke fashion accessory. People transition because they must. What commentators of all political stripes lack is the lived experience, and this is supplied by Shon Faye, though she is at pains to point out that this is not a memoir, rather a survey of how trans people at all stages of life have to negotiate the world. The Transgender Issue is unapologetically left-wing in tone, which is fair enough, but one does get the impression it is preaching to the choir, when it deserves to be read far outside activist or LGBTQ+ circles. When Faye turns from ideology to pragmatic politics, she is absolutely compelling. A section on prisons, for example, articulates why the UK’s current penal system needs reform. Not for ideological reasons, but because prison doesn’t work as a means either of reducing crime or rehabilitating offenders, most of whom shouldn’t be locked up anyway. It is tempting, as a reviewer, to wish for a book the author hadn’t written. There is a lot — necessarily so — on the often fraught relations between the trans community and others in the LGBTQ+ rainbow, and, yes, with feminists. This might give ammunition to those conservatives who wish to find divisions and exploit them (Faye is well aware of this, and gives examples of unholy alliances between religious conservatives and anti-trans feminists) but very little about how gender ideation in our societies is conditioned by religious tradition, and nothing at all about the participation of trans people in sport — another topic of seemingly obsessive interest by legislators, and, therefore, news media. After reading this book, though, I am convinced that the most fundamental human right must be that a person should have absolute autonomy over their own body. Nobody else — not politicians, not priests, not doctors, not psychiatrists — should be able to gainsay a person’s gender identity. In an ideal world, people should be judged by the content of their character, not the content of their underpants. Full disclosure: I identify as a cis heterosexual white male who supports Norwich City FC (pronouns he/ him/ his; adjectives, sleepy/ dopey/ grumpy) and although socially liberal, generally votes conservative. And yet this book derailed my political outlook. In other words, it does what all books attempt but few achieve — it can change peoples’ minds. It might help that I have a son who is trans and who has introduced me to wonderful people in the queer community. But I am also a member of a historically oppressed and ‘othered’ minority and as such I was struck by this passage:

Shon Faye: The Transgender Issue I was alerted to this by Stephen: it was something of an eye-opener. From the amount of newsprint and airtime devote to trans people, you’d think they were engaged in a full-scale invasion. Shon Faye shows that they constitute a near-negligible proportion of the population and are oppressed in every way by a majority that would rather they didn’t exist and will go some considerable way to fulfilling that desire. Marginalised, they, like many other minorities, struggle to find employment and are over-represented in the gig economy and sex work. Demonised by the right-leaning press as woke snowflakes that want to shut down free speech: exhibited by the left-leaning press largely as a problem for feminism, the regular person is entitled to ask what’s really going on — and Shon Faye tells us. (Aside: I was brought up by my mother, a WI stalwart, listening to Woman’s Hour on the radio. She hadn’t listened to it for years, she said, as it had been more concerned these days with gender politics than issues that were, to her, of greater interest. I switched on and was immediately pitched into a furious argument between a radical feminist and a trans person. In the old days, I thought, audiences could be titillated by bear-baiting. I switched off). The fact is that nobody wants to be trans as a kind of woke fashion accessory. People transition because they must. What commentators of all political stripes lack is the lived experience, and this is supplied by Shon Faye, though she is at pains to point out that this is not a memoir, rather a survey of how trans people at all stages of life have to negotiate the world. The Transgender Issue is unapologetically left-wing in tone, which is fair enough, but one does get the impression it is preaching to the choir, when it deserves to be read far outside activist or LGBTQ+ circles. When Faye turns from ideology to pragmatic politics, she is absolutely compelling. A section on prisons, for example, articulates why the UK’s current penal system needs reform. Not for ideological reasons, but because prison doesn’t work as a means either of reducing crime or rehabilitating offenders, most of whom shouldn’t be locked up anyway. It is tempting, as a reviewer, to wish for a book the author hadn’t written. There is a lot — necessarily so — on the often fraught relations between the trans community and others in the LGBTQ+ rainbow, and, yes, with feminists. This might give ammunition to those conservatives who wish to find divisions and exploit them (Faye is well aware of this, and gives examples of unholy alliances between religious conservatives and anti-trans feminists) but very little about how gender ideation in our societies is conditioned by religious tradition, and nothing at all about the participation of trans people in sport — another topic of seemingly obsessive interest by legislators, and, therefore, news media. After reading this book, though, I am convinced that the most fundamental human right must be that a person should have absolute autonomy over their own body. Nobody else — not politicians, not priests, not doctors, not psychiatrists — should be able to gainsay a person’s gender identity. In an ideal world, people should be judged by the content of their character, not the content of their underpants. Full disclosure: I identify as a cis heterosexual white male who supports Norwich City FC (pronouns he/ him/ his; adjectives, sleepy/ dopey/ grumpy) and although socially liberal, generally votes conservative. And yet this book derailed my political outlook. In other words, it does what all books attempt but few achieve — it can change peoples’ minds. It might help that I have a son who is trans and who has introduced me to wonderful people in the queer community. But I am also a member of a historically oppressed and ‘othered’ minority and as such I was struck by this passage:

Moral panics rely on an inherent paradox: that the rights of a small minority of the population wielding little institutional power are in fact a risk to the majority. This is achieved by inciting in the population a mixture of moral disgust and anxiety about contagion.

Sound like anyone you know?

Joe Haldeman: Peace and War Three novels in one here, what the book clubs would call ‘counts as one choice’. The first, The Forever War, published in 1974, is SF as Vietnam aftershock (based on the author’s own Vietnam experience), and rightly hailed as a genre classic. William Mandella is one of Earth’s brightest and best, conscripted to fight the alien Taurans. But constant accelerations to sizeable fractions of light speed means that when his tour is over, relativity ensures that all his friends and family are dead, and even society has changed to the edge of unintelligibility. The only thing he can do is re-enlist. The sequel, Forever Free (1999), follows Mandella and the veterans as they try and fail to settle down on the subarctic planet of Middle Finger, chafing against the homogeneous and authoritarian mass that the human race has become. It’s a bit of a plod, and overcompensates in the final ten pages when it goes a bit loopy. Forever Peace is connected with the first two only thematically, in that the protagonists are reluctant soldiers trying to bring an end to warfare. It’s set in the mid-21st century in which the United States uses remotely controlled soldiers or ‘soldier boys’ to wage a seemingly never-ending war on a hydra-like profusion of rebel groups in the failed states of the global south. Mix in a vast particle physics experiment that has the potential to suck the cosmos into a black hole, with a conspiracy of Christian fundamentalists and white supremacists who’ll stop at nothing to see this happen, and parts of the novel, written in 1997, seem horribly prescient. It’s an enjoyable read, though the author tends to get bogged down in unnecessary details of the characters’ daily lives, a phenomenon known to SF writers as ‘Squid-On-The-Mantelpiece‘ in which the prospect of imminent apocalypse renders as tedious any attempt to dramatise the everyday.

Joe Haldeman: Peace and War Three novels in one here, what the book clubs would call ‘counts as one choice’. The first, The Forever War, published in 1974, is SF as Vietnam aftershock (based on the author’s own Vietnam experience), and rightly hailed as a genre classic. William Mandella is one of Earth’s brightest and best, conscripted to fight the alien Taurans. But constant accelerations to sizeable fractions of light speed means that when his tour is over, relativity ensures that all his friends and family are dead, and even society has changed to the edge of unintelligibility. The only thing he can do is re-enlist. The sequel, Forever Free (1999), follows Mandella and the veterans as they try and fail to settle down on the subarctic planet of Middle Finger, chafing against the homogeneous and authoritarian mass that the human race has become. It’s a bit of a plod, and overcompensates in the final ten pages when it goes a bit loopy. Forever Peace is connected with the first two only thematically, in that the protagonists are reluctant soldiers trying to bring an end to warfare. It’s set in the mid-21st century in which the United States uses remotely controlled soldiers or ‘soldier boys’ to wage a seemingly never-ending war on a hydra-like profusion of rebel groups in the failed states of the global south. Mix in a vast particle physics experiment that has the potential to suck the cosmos into a black hole, with a conspiracy of Christian fundamentalists and white supremacists who’ll stop at nothing to see this happen, and parts of the novel, written in 1997, seem horribly prescient. It’s an enjoyable read, though the author tends to get bogged down in unnecessary details of the characters’ daily lives, a phenomenon known to SF writers as ‘Squid-On-The-Mantelpiece‘ in which the prospect of imminent apocalypse renders as tedious any attempt to dramatise the everyday.

Edward Gibbon: The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire (Folio Society Edition) – Vol 6. This volume is, like Gaul, divided into three parts. The first is an extended essay on the internecine warfare between early Christian sects about the nature of the Incarnation, which, like the earlier arguments about the nature of the Trinity, Gibbon finds as exasperating as we do. So much ink — and blood — spilled over distinctions so fine as to be invisible. Comparing two of the various schismatic sects:

Edward Gibbon: The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire (Folio Society Edition) – Vol 6. This volume is, like Gaul, divided into three parts. The first is an extended essay on the internecine warfare between early Christian sects about the nature of the Incarnation, which, like the earlier arguments about the nature of the Trinity, Gibbon finds as exasperating as we do. So much ink — and blood — spilled over distinctions so fine as to be invisible. Comparing two of the various schismatic sects:

… their intestine divisions are more numerous, and their doctors (as far as I can measure the degrees of nonsense) are more remote from the precincts of reason.

There’s a mess in ‘ere, but no Messiah. And if that wasn’t enough, the Byzantines get themselves embroiled in a furore about whether the adoration of icons counts as idolatry, as if the profusion of saints and martyrs, miracles and relics didn’t already count as some kind of backsliding into polytheism.

In the long night of superstition the Christians had wandered far away from the simplicity of the Gospel: nor was it easy for them to discern the clue, and tread back the mazes of the labyrinth.

The second part is a chronological, one-damned-thing-after-another treatment of the decline of the Byzantine Empire as far as their conquest by the Crusaders, a sixty-monarch, six-hundred-year canter through time compressed into a few pages. Gibbon himself feels it a bit rushed:

In a composition of some days, in a perusal of some hours, six hundred years have rolled away, and the duration of a life or reign is contracted to a fleeting moment: the grave is ever beside the throne; the success of a criminal is almost instantly followed by the loss of his prize; and our immortal reason survives and disdains the sixty phantoms of kings who have passed before our eyes, and faintly dwell on our remembrance.

This telescoped treatment, however, allows Gibbon to reflect on the point of it all, the struggles of the various Michaels and Basils and Leos and Borises and Rishis and Constantines (all of whom are appalling) up the greasy imperial pole:

Was personal happiness the aim and object of their ambition? I shall not descant on the vulgar topics of the misery of kings; but I may surely observe that their condition, of all others, is the most pregnant with fear, and the least susceptible of hope.

Then there is an excursion into the reign of Charlemagne and whether the Frankish Empire was in any sense Holy or Roman. But all this is hors-d’oeuvres to the main dish, an examination of ‘one of the most memorable revolutions which have impressed a new and lasting character on the nations of the globe’ — the sudden emergence and rapid spread of Islam. This appeared from, almost literally, nowhere, and spread from the Indus to the Atlantic in the space of a century. Its success is partly attributable to its emergence at a time when the Roman and Persian Empires were at their weakest.

The birth of Mohammed was fortunately placed in the most degenerate and disorderly period of the Persians, the Romans, and the barbarians of Europe; the empires of Trajan, or even Constantine or Charlemagne, would have repelled the assaults of the naked Saracens, and the torrent of fanaticism might have been obscurely lost in the sands of Arabia.

Part of Islam’s appeal, though, is its simplicity:

‘I believe in one God, and Mohammed is the apostle of God’, is the simple and invariable profession of Islam. The intellectual image of the Deity has never been degraded by any visible idol; the honours of the prophet have never transgressed the measure of human virtue; and his living precepts have restrained the gratitude of his disciples within the bounds of reason and religion.

What a refreshing contrast, Gibbon seems to say, with the sterile complexities of Christian theology:

… the religion of Mohammed might seem less inconsistent with reason than the creed of mystery and superstition which, in the seventh century, disgraced the simplicity of the Gospel.

Jeremy Farrar and Anjana Ahuja: Spike Passionate, polemical and partisan, this is a first-hand account of the first year or so of the Coronavirus pandemic from one at the eye of the storm. Farrar is the Director of the Wellcome Trust, an expert on the spread of epidemics, and was a member of SAGE, the group of scientists advising the UK government on policy — if only the government cared to listen. Ahuja is a journalist who pulled Farrar’s diary of the plague year into the form of something like a thriller. The large cast of characters and the forest of organisational acronyms can be hard to navigate but there’s a helpful glossary and dramatic personae at the end. This is very much a view from the trenches and does not count as a comprehensive history of the pandemic, for much is omitted. There is almost nothing on, say, the efficacy of wearing masks; the studies showing that the virus does not live on surfaces; and the pernicious effects of the anti-vaccination movement. And although the author does like to take political pot shots, his view is selective. He discusses the former (Labour) Prime Minister Gordon Brown (with whom he is on first-name terms) although his role was peripheral, yet nowhere at all does he mention the (Conservative) then-Chancellor Rishi Sunak and his colleagues at the Treasury whose heroic work kept the economy alive during the lockdown. Although it is regrettably true that the Conservative Party is historically very poor at understanding science, balance should not be a casualty of the author’s understandable frustration. Nevertheless, when the history of the pandemic comes to be written, this will be important source material. Shortlisted for the Royal Society Science Book Prize 2022 (DISCLAIMER: I also have a dog in that fight).

Jeremy Farrar and Anjana Ahuja: Spike Passionate, polemical and partisan, this is a first-hand account of the first year or so of the Coronavirus pandemic from one at the eye of the storm. Farrar is the Director of the Wellcome Trust, an expert on the spread of epidemics, and was a member of SAGE, the group of scientists advising the UK government on policy — if only the government cared to listen. Ahuja is a journalist who pulled Farrar’s diary of the plague year into the form of something like a thriller. The large cast of characters and the forest of organisational acronyms can be hard to navigate but there’s a helpful glossary and dramatic personae at the end. This is very much a view from the trenches and does not count as a comprehensive history of the pandemic, for much is omitted. There is almost nothing on, say, the efficacy of wearing masks; the studies showing that the virus does not live on surfaces; and the pernicious effects of the anti-vaccination movement. And although the author does like to take political pot shots, his view is selective. He discusses the former (Labour) Prime Minister Gordon Brown (with whom he is on first-name terms) although his role was peripheral, yet nowhere at all does he mention the (Conservative) then-Chancellor Rishi Sunak and his colleagues at the Treasury whose heroic work kept the economy alive during the lockdown. Although it is regrettably true that the Conservative Party is historically very poor at understanding science, balance should not be a casualty of the author’s understandable frustration. Nevertheless, when the history of the pandemic comes to be written, this will be important source material. Shortlisted for the Royal Society Science Book Prize 2022 (DISCLAIMER: I also have a dog in that fight).

Nick Davidson: The Greywacke Cast your mind back to the early nineteenth century when two titans of geology — the ambitious, social climbing ex-soldier Roderick Murchison and the mild-mannered cleric Adam Sedgwick sought to map the confusing jumble of rocks that was Wales. Back in the day, everything older than the Old Red Sandstone was a muddle called the Greywacke, and this is the story about how it gave up its secrets. In the end, Murchison’s Silurian trumped Sedgwick’s Cambrian, and the two once close colleagues fell out spectacularly. It was only resolved in the next generation when an even more mild-mannered schoolteacher, Charles Lapworth, came along and discovered the Ordovician that sat between them. This is a classic piece of popular history of science (I am reminded of The Cuvier-Geoffroy Debate by Toby Appel, another tale about how two close friends fell out over scientific minutiae). The author — a documentary filmmaker and outdoorsman — has done his work with incredible diligence, not only digging into rarely seen archives but tramping the same fells and rills as his protagonists. This could so easily have been a yarn about dead white blokes bashing rocks. That it is so much more is a testament to the author’s skill. An immensely satisfying read. Shortlisted for the Royal Society Science Book Prize 2022 (DISCLAIMER: I also have a dog in that fight).

Nick Davidson: The Greywacke Cast your mind back to the early nineteenth century when two titans of geology — the ambitious, social climbing ex-soldier Roderick Murchison and the mild-mannered cleric Adam Sedgwick sought to map the confusing jumble of rocks that was Wales. Back in the day, everything older than the Old Red Sandstone was a muddle called the Greywacke, and this is the story about how it gave up its secrets. In the end, Murchison’s Silurian trumped Sedgwick’s Cambrian, and the two once close colleagues fell out spectacularly. It was only resolved in the next generation when an even more mild-mannered schoolteacher, Charles Lapworth, came along and discovered the Ordovician that sat between them. This is a classic piece of popular history of science (I am reminded of The Cuvier-Geoffroy Debate by Toby Appel, another tale about how two close friends fell out over scientific minutiae). The author — a documentary filmmaker and outdoorsman — has done his work with incredible diligence, not only digging into rarely seen archives but tramping the same fells and rills as his protagonists. This could so easily have been a yarn about dead white blokes bashing rocks. That it is so much more is a testament to the author’s skill. An immensely satisfying read. Shortlisted for the Royal Society Science Book Prize 2022 (DISCLAIMER: I also have a dog in that fight).

October 27, 2022

Camp Catastrophic

Back in the early days of the present unpleasantness I was engaged to take part in a literary festival in Hay-on-Wye (no, not that one, a different one). Cognisant that Offspring2 is a keen bibliophile, I thought I could take her along — while I was giving talks and taking part in panels, she could browse the more than thirty bookstores in that remarkable Welsh border town.

But COVID intervened, the festival went online, and Offspring2 didn’t get her promised trip. So, when the Gees acquired a camper van, we pencilled in a trip, and booked a campsite just a few steps away from Hay. Now, this happened a few weeks ago: I’ve only now been able to bring myself to write about the ensuing disaster.

So, Offspring2 and I set off from Cromer, full of joy and anticipation, and listening to the BBC’s hoary old adaptation of The Lord of the Rings on cassette (did I say that the camper is so retro it has a cassette player?)

Well, the clouds gathered just over halfway, on the M42 near Birmingham, when the coolant warning light went on and stayed on, accompanied by a horrible constant buzzing noise. We pulled over and called the AA (no, not that one, a different one). Eventually a tow truck arrived and towed us to a safe place. The driver checked our coolant and topped it up. We decided not to wait for an AA patrolman (this proved to be a mistake) and pressed on … but it wasn’t long before warning lights flashed; the engine temperature indicator went up and down like the Assyrian Empire; but we were nearly there, so just after dark we pulled in to the campsite. It was called Black Mountain View and was a wonderful place, and would have made for a pleasant holiday under different circumstances. Offspring2 settled down to sleep in the van while I pitched the awning, unfolded the camp bed and snuggled down to sleep. Or, at least, I tried. It was a cold and damp night.

What with the worries about the van (the whole interior smelled of burning rubber) and the damp night we decided to abandon our holiday and try to get home. With the help of the campsite owner (a skilled mechanic) we topped up the coolant again and set off.

Ten miles out, not far from Hereford, we finally broke down. Steam was pouring from the engine. We called the AA again. This time the patrolman had a better idea of the problem – we had probably blown the head gasket. Big, big problem, and the van was no longer safe to drive.

There followed a succession of tow trucks that took us from Hereford in easy stages to the Barton Mills service area on the A11, some 68 miles from home. By that time the Sun had set and the Moon had risen — I took this picture from the tow truck of the Moon and Jupiter. But by then, the AA had run out of tow trucks, and they had to get a taxi. We eventually got home 15 hours after our breakdown. I had to leave the keys to the van at the service station. The van was towed home next day; a couple of days later my garage came to take it to their workshop … and that’s where it is now.

There followed a succession of tow trucks that took us from Hereford in easy stages to the Barton Mills service area on the A11, some 68 miles from home. By that time the Sun had set and the Moon had risen — I took this picture from the tow truck of the Moon and Jupiter. But by then, the AA had run out of tow trucks, and they had to get a taxi. We eventually got home 15 hours after our breakdown. I had to leave the keys to the van at the service station. The van was towed home next day; a couple of days later my garage came to take it to their workshop … and that’s where it is now.

If and when the van gets back to us we might have second thoughts about camping, or at least, anywhere far away. However, the night sky in Wales was so lovely that I can imagine my taking the van to dark hilltops for stargazing with my new telescope. So perhaps, even when I am lying in the gutter (and smelling of burning rubber), I can still look up at the stars.