Andrew Kozma's Blog, page 2

July 10, 2017

Unpulped #16: Earthman’s Burden by Poul Anderson

Sometimes I think I don’t write about a book immediately after reading it so that the bad feelings have time to fade. If I wrote in books, this one would be furiously underlined, bracketed, and starred. I’d be having one-sided arguments in the minuscule margins. There’s be so many highlights, the pages would become beautiful rainbows.

And then sometimes I think I don’t write about a book immediately after reading it because I hope it’ll transform into something beautiful in hindsight, time and memory sanding away the edges until I can see what’s beautiful hiding underneath. The book as sea glass or driftwood.

Instead, we’ve got “The Adventures of the Incredible Hokas” which are not all that incredible, and generally uninspired and somewhat boring IN ADDITION to being sexist, racist, and imperialist. In all of Poul Anderson’s books-made-of-stories so far, I’ve found no stories which are worth reading, that stand out as memorable rather than workmanlike.

(And, yes, this is a collection co-written by Gordon R. Dickson, but I honestly couldn’t tell the difference between this book and the others I’ve read by Anderson. Does that mean his writing is bland? That it easily takes on the color of whoever he’s writing with? Or that Dickson’s writing is also literary mayonnaise? I don’t know, because I’ve never read Dickson outside of this book, and Anderson’s already so grimed in my eye I don’t think I can judge his writing in an unbiased way anymore.)

The Story: Ensign Alexander Braithwaite Jones of the Interstellar Survey Service crashes on Toka far from where he needs to be in order to rejoin Earth society and be rescued. On his way to safety, he encounters alien teddy bears (the Hokas) acting like they are in the Old West (the movie version) because they are simple-hearted mimics and the first humans on the planet showed them Westerns. Anyway, he helps them commit genocide against the other alien race on the planet, and he becomes the official ambassador/liaison to Toka. Hijinks ensue for the next five stories where, in each, the Hoka attach themselves to another genre, from opera (via Don Giovanni) to space patrol stories (a la the Lensman series).

As you might guess from the above, the Hoka are used for comedy and Braithwaite Jones is the straight man in all the comic scenes. Which might be fine, I suppose, if the comedy was funny. (And who knows, maybe it was funnier in days of yore, but I think it more likely the stories came off like not-terrible SNL sketches: okay in the moment, maybe even eliciting a chuckle or at least acknowledgement that was you just read was a “joke,” but not even worth repeating the next day, forgotten instantly.) But the comedy isn’t funny. And it’s not just the naive and inane Hoka played for laughs, but also women (Isn’t it funny when women (professional women with their own jobs) fight over men, and are just working the job angle in order to get married HAHAHAHAHAHA) and alien races (which are basically non-white person equivalents, dominated for monetary purposes by Earth people).

I mean, there’s an alien race called the Pornians. From Pornia.

And it’s not even good writing. Each story starts off with Braithwaite Jones in the same position. The Hoka take on a role, and he is AMAZED and ASTOUNDED that they would behave so strangely, and oh my God, what will he ever do? (Answer: He’ll bumble along and manage to save the day by accident, then take all the credit.) What we’ve got here is the equivalent of an inoffensive sit-com in SFF story form.

Strangely, there is some self-awareness of the imperialist aspect of the stories in one of the interstitial pieces written (I believe) to connect the stories.

But I have been increasingly nagged by a very basic doubt–a doubt of the value, even the rightness, of the Service’s very raison d’etre. Is it possible that our problem of “civilizing backward planets” is only a subtle form of the old, discredited imperialism of Earth’s brutal past? Have I merely been turning my wards into second-rate humans instead of first-rate Hokas? I don’t know. In spite of all our pretentious psychocultural tests, I doubt if anyone really knows.

I know. And Braithwaite Jones knows, despite all his protesting, just like Poul Anderson knows, even if he hides it behind the ignorance of a fictional persona.

I mean, admitting your doing something shitty doesn’t really matter if you continue doing that shitty thing. Like with the depictions of women (even though there’s never a point where Anderson or Braithwaite Jones admits their sexism) which continues wherever women are present in the stories. For example, the final one where Braithwaite Jones’ wife crash lands on a planet and is desperate for rescue only, apparently, because the local food will make her fat.

No, seriously, that’s her main motivation.

“But there’s something in it! High calories or something. I’m putting on kilos and kilos. Alex, you’ve got to come right away!”

Right. No real fear of, you know, having crashed on an alien planet without a way to return home.

You know, I want to be done with Poul Anderson. And I don’t really think I have much more to say about him–each book pretty much repeats all the faults from the previous books without having any redeeming qualities. So I’m skipping out of three of the four Anderson books I have left in my Unpulped stash.

However, there is one book of Anderson’s which was nominated for a Nebula the same year Dune won that award. This is The Star Fox and it’ll be my final foray into Poul Anderson. It was nominated for a Nebula award, so how bad can it be?

I intend to find out.

May 22, 2017

Unpulped #15: Trader to the Stars by Poul Anderson

[image error]

My girlfriend is surprised I finished this book, based on all the times I interrupted her own reading to complain about some passage I’d just read. I’m somewhat surprised, too. But I’ve developed an unhealthy fascination for Poul Anderson’s older works, and I think it’s because I read his novel THREE HEARTS AND THREE LIONS a long time ago (high school?) and liked it, and kept it on my shelf for years. I don’t remember that book being rife with sexism or racism or colonial/imperial biases and I don’t know if that’s because I was younger and more obtuse at the time, or because it wasn’t there.

Based on his books I’ve read recently, I’m guessing young/obtuse wins.

Blond, big-eyed, and thoroughly three-dimensional, Jeri Kofoed curled on a couch within easy reach of him where he sprawled on his lounger.

TRADERS TO THE STARS takes place in his frontier-verse which follows members of the Polesotechnic League—basically an East India Company of the future, prioritizing trade and profit above all else. The stories here and in the other books in this same universe are often re-skinned Westerns or Explorer tales, with alien races standing in for the “uncivilized” natives who deserve to be both bamboozled and enslaved, forcefully brought into a galactic society because that’s clearly what’s good for them, whether they realize it or not. (The aliens are armed with arrows and tomahawks, for god’s sake.)

The women are objects and ineffective, willing (like Kofoed above) to use their sexuality to get what they want, and hitching themselves to the strongest male around, either for protection or for future monetary rewards. Kofoed is attached to Nicholas Van Rijn, Anderson’s “heroic” Dutch Trader/Exploiter, and though she flirts with the captain of Van Rijn’s ship in the opening story of the book, she returns to Van Rijn because he promises her a comfortable life in her own apartment back on Earth.

She sprang to her feet, mutinous. Without rising, he slapped her on the appropriate spot.

That’s how embedded sexism is in this book. The “appropriate spot” doesn’t have to be defined. You don’t have to be convinced that physical abuse to get someone to do what you want is appropriate, because you’re a white male and of course it is.

Jeri came back with two stiff Scotch-and-sodas. His gaze followed her. In a tight blouse and half knee-length skirt, she was worth following.

It’s easy to say that Poul Anderson was just a product of his times. He was born in 1926, and the world changed greatly over his lifetime. Why not just see the dominant POV of his stories as echoing the world in the 50s and 60s? Why blame him?

Because there are other writers who created stories that didn’t have these basic assumptions, that didn’t put women and non-white races (or aliens) in the realm of second-class citizens, who need to be protected and guided by a white male savior.

Van Rijn is also Toxic Masculinity. He constantly sexually harasses any woman he’s around (and in Anderson’s stories, that women usually is “seduced” by this harassment). When the captain of his ship fights him for Kofoed’s affections, Van Rijn knocks him out, then gives him a promotion, explaining how he likes the people who work for him to have fire or some such bullshit. The world is designed for Van Rijn’s pleasure and exploitation, and if you have to kill a few aliens or destroy a culture in order to get them to buy your beads while you take their land, then so be it.

Here’s the plot of the opening story: Van Rijn was investigating a hostile sector of the galaxy for new trade routes and his ship is on the run from enemy ships. They can’t outrun them because the engines were damaged. They end up finding another innocent, neutral ship that fails to respond to their distress calls, so they violently board the ship, enslave the alien crew, and force them to take Van Rijn’s crew back to a safe planet.

“They will cooperate under threats, as prisoners, at first. But on the voyage, we […] get the idea across […] we want to be friends and sell them things.”

In the second story, the main character is a woman scientist from a pacifist planet trying to rebuild a planet’s atmosphere. She’s clearly intelligent and qualified and competent, otherwise she wouldn’t be on the planet. However, Van Rijn, in the middle of a conversation, tells her to make him a sandwich (which she does). He tells her to shut up when he’s thinking.

“Well, hokay, you is a pretty girl with a nice figure and stuff even if you should not cut your hair so short. Waste not, want not. I rescue you, ha?”

(Not to mention that we are far in the future, Van Rijn is a master trader, and he has a thick Dutch accent and speaks broken, malapropistic English. Anderson’s world-building is…lacking.)

“You just leave the philosophizings to me, little girl,” he said smugly. “You only got to cook and look beautiful.”

He pats her knee. He invades her personal space. He belittles her ideas and experience. This is our hero, folks. This is who we should be admiring.

The scientist’s planet was going to build plants to recreate the planet’s dying atmosphere/ecology for free. Van Rijn will take over the building of the plants and sell the materials to the aliens because, primitive as they are, they don’t understand charity, just profit.

Alien planets are unexplored (who cares about the intelligent life forms already living there). They are the darkest continents, the Western frontier, places meant to be invaded and exploited by the more powerful and, therefore, more civilized human galactic empire. The aliens are tribal, live in huts, fight with archaic weapons. And Van Rijn and his group, what are they trading for? What are the invading for?

Furs and spices.

“It’s just waiting for the right man. A whole world, Dad!”

Just waiting for the right “man” because aliens can’t be men, in the general sense of a person. And if someone (or something) isn’t a person, then it isn’t deserving of respect. The final story in the book treats us to aliens that have slaves, and a horrifying and clueless description of them by one of the main characters.

“But Lugals are completely trustworthy,” Per said. “Like dogs. They do the hard, monotonous work. The Yildivans—male and female—are the hunters, artists, magicians, everything that matters. That is, what culture exists is Yildivan.” He scowled into his drink. “Though I’m not sure how meaningful ‘culture’ is in this connection.”

This racism is echoed in the humans themselves. The assumption is that the group presented (they are at a dinner party, telling a story of some of their exploits) is entirely white, except for one Nuevo Mexican who is described this way: “I was unarmed—everybody was except Manuel, you know what Nuevo Mexicans are.”

That “what” is key. Because eventually Van Rijn solves the problem of this exploitation expedition that goes awry by pointing out that the Lugals aren’t slaves, but domesticated animals. Even though they are an intelligent race, clearly used as mass labor by the Yildivans, sold, actually, and in themselves a form of currency. It’s eugenics, plain and simple. And then he says that, opposed to the Lugals, the Yildivans are wild animals. Both animals. Both ruled by instinct and genetics rather than thought and logic.

So, you know, it’s okay to kill them or trick them or exploit them.

I hate this book.

May 15, 2017

Unpulped #14: The Rebel Worlds by Poul Anderson

[image error]

The copy of the book I have has this tag line: “Two men and one woman in a desperate battle to win a galactic empire—or destroy it!”

Though, really, the woman is incidental. Really, she is the focus of a love triangle. Really, she is the cause—almost—for the social awakening of the younger of the two men, except that social awakening never happens, and he returns the galactic empire to the status quo even though that means enslavement and death for countless people. Really, this book is a space-fantasy based on the decline of the Roman Empire that re-establishes the importance of political stability over the good of individual citizens. An imperialist fantasy.

The basic plot: A favorite of the stupid and decadent emperor has carved out his own fiefdom in the farther reaches of imperial space, enslaving planets, killing those who disagree with him, and reaping riches from the bodies of the empire’s citizens. The top admiral in the area, McCormac, revolts against this despot, and Flandry, a young commander, is sent to stop the revolt. Kathryn, McCormac’s wife, is captured by the evil despot, freed by Flandry, and seduced by the same. In the end, Flandry convinces McCormac and co. to leave imperial space, reestablishing peaceful civilization (though not addressing any of the horrible things that the despot instituted—such as crucifixion as punishment). And everybody wins!

By everybody, I mean those who live at the center of the empire, who profit off of all of the worlds incorporated by the empire, who don’t have to worry about what goes on in the outer reaches because it doesn’t matter, as long as business in the center is unaffected.

Women are only useful as love objects. Women who are raped/assaulted are only used at plot points for the male heroes. In fact, the only reason the evil despot (such a cartoon, such a limited presence, he doesn’t even deserve to be named here) is killed by Flandry is because he raped Kathryn. Who cares that he sentenced hundreds or thousands of people to death? What we have here is the heroism of the personal affront over heroism for the public good.

I don’t know if it’s fair for me to criticize the book for using heroic tropes and clichés. It’s not Anderson’s fault I’m reading this book fifty years after he wrote it (though I’ve read books from that time which are infinitely more complicated and aware). It’s not the fault of THE REBEL WORLDS that I’m concerned more about the social effects of heroism and the social good as opposed to the personal, or at least recognition that personal heroism has costs when ignoring the social.

And while it may not be fair, it’s impossible not to call Anderson out. The book is riddled with misogyny and the worst of capitalist and imperialist conceits.

The writing isn’t all that great, either.

May 8, 2017

Unpulped #13: The Trouble Twisters by Poul Anderson

[image error]

When I started writing this Unpulped series, I knew I’d be reading bad books. However, even though Poul Anderson’s The Trouble Twisters is bad, I didn’t think any book I was reading would bother me as much as this one did.

I think it’s because I’ve read Anderson before, and liked him. Liked the books I read enough to keep them around for a while instead of insta-giving them away, which means that I saw something worthwhile there. He has a wealth of historical knowledge which made for a good fantasy (Three Hearts and Three Lions was the book, if I recall correctly) but maybe I just overlooked all the sexism when I read it before? High School and College me wasn’t as aware of things as I am now.

And then there’s the fact that his strength in fantasy—historical knowledge of armor and weapons and cultures—is detrimental to his science-fiction because he has aliens in space with halberds, wearing armor like you’d find on Earth but twisted slightly to fit alien bodies (though, actually, he never discusses those changes, you just have to assume). Anderson comes from the belief (at least in this book) that all intelligent species would go through the same stages of civilization as humanity, and in all aspects. Religion? The same, ending towards the most advanced monotheistic version. Economy? The same, which is why the “hero” of The Trouble Twisters can make his living tricking less-advanced cultures out of all their tradeable goods for little more than space beads.

To be clear, this is a book where the hero not only ignores the Prime Directive, but is willing to destroy a planet’s original culture in order to get one that’s more amenable to interstellar trade. The book is a paean to misogynistic, paternalistic colonialism, and rampant capitalism.

The book is clearly three stories mashed together rather than a novel. That is less an excuse than just the way things were done back in the old pulp fiction days—you publish stories in magazines and expand them into a novel in order to make more money off of your work. And while I’m all for maximizing profit from writing (I’m a writer, so I’m biased), in this case that simply means repetition of theme rather than growth or an arc. The novel keeps slapping you in the face with misogyny and cultural prejudice (i.e., aliens are dumb, humans are the bomb).

Oh, who am I kidding, it’s not the novel: it’s Anderson. There have been lots of books I’ve read before 1963 and from the same time period that don’t have these problems. It’s his choice in writing, just as it was his choice to basically make this novel Cowboys in Space. There’s a point in the first section where the hero has to shoot his alien horses in order to hide behind them for an alien shoot out with alien aggressors (read: Hollywood-style Native Americans, because they even have space bows and space arrows).

Now for some quotes:

“Yes, I daresay this culture is most vulnerable to new ideas,” Mukerji said. “There have been none for so long that the Larsans have no antibodies against them, so to speak, and can easily get feverish…”

[pg. 26, where we’re introduced to the strange Andersonian notion that cultures grow stagnant and dull with no new ideas. Imagine, a planet where no new idea happens. No new art, no new science, no new invention. This is just bad fantasy in a colonial vein, because, of course, who brings the new ideas? Our heroes.]

“Come, come. A dinner without an aperitif is like a—ahem!—a day without sunshine.” He had almost said, “A bed without a girl,” but that might be rushing things.

[pg. 70, as our hero tries to seduce the commander of an alien force simply because she’s a woman and he hasn’t seen a woman in a long time; also, of course, because she’s absolutely gorgeous]

In both the second and third sections, the only ones where love interests are at play, the woman falls for Our Hero after he shows martial superiority and triumphs over her own people and culture. She gladly gives herself to him, ignoring her past and her own agency, her own wants and needs, as long as she can fulfill his desires.

God, this novel is tripe.

May 5, 2017

The Universe of Obligation (The Samizdat experiment poem #4)

This is the fourth poem of mine published on The Samizdat, my Patreon journal-experiment designed to promote political poetry and give to charities at the same time (the money raised divided between the poet and the charity). If you want to join in this experiment, you can do so here: The Samizdat.

Sometimes after the first poem in this experiment was posted, this blog went down and out into the underbelly of the internet, unfindable and unfound. This is why we’ve missed each other all these months since, and why I’ve not been able to meet your for tea and cake. I’m sorry.

This poem will likely not make you feel better, but it is all I have.

The Universe of Obligation

NO DOGS OR MEXICANS ALLOWED, the sign reads,

but sometimes they let the dogs in. What everyone needs

is not just a bill of rights, but a receipt to prove they paid.

We’re alive! We deserve to live! they cry, right before the raid.

And if someone dies in camp, they deserved that, too. Non-persons

obligate no obligations. And if my inaction worsens

their fate, or the state of our state, no guilt

hydras its way into being. This foundation is built

on the backs of the nameless and, therefore, undying.

Every baby born deserves happiness, we say, but we’re lying.

February 20, 2017

Song of the Grave (The Samizdat experiment poem #1)

So, I’ve started my Patreon journal experiment in political poetry/charity. If you want to know all the details re: THE MANIFESTO and THE ACTION PLAN, then direct your attention to this link: The Samizdat. For $1 a poem (up to four a month), you’ll be supporting both poetry and politics–half of the money goes to the poet, half to a charity of their choice.

Since a significant part of this experiment is writing poetry with a political bent, and politics requires action, I will be spreading my poems as far and as wide as I am able (other contributors to The Samizdat will vary in this). And so here is the first result of the experiment, a poem inspired by Solzhenitsyn’s The Gulag Archipelago about the risks of letting others be targeted by the government (or even adjusting the sights of those with the weapons).

I’ve been rereading Solzhenitsyn’s giant history/act-of-recovery/commentary because it epitomizes the fear of what the U.S. might become, while also speaking to my own reluctance to get involved, my own weakness when it comes to standing up. I’ll be writing more about my experience rereading him soon, but for now you just get this poem.

Song of the Grave

(Oh, do not dig a grave for someone else!)

~Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, The Gulag Archipelago

The mouth opens. Worms and roots line its cheeks.

Its teeth are shovel blades. The moisture-blooded soil

refuses to let go, gnawing on boot soles. Skin can be leather, too,

something tough to hold the organs in, something numb to feeling.

We are born into being alone, live alone, die alone, if lucky,

rest alone in our marked graves. If not, we become landscape.

Either way, people say there’s a paradise in that us-shaped space

we’re destined to fill. Since we’re all going to the same place,

does it matter how soon we get there? Only dig the grave

you’re prepared to climb into. Only open the mouth

you’re ready to speak from. The suited men fill their palms with teeth.

They fill the mouths with dirt. They fill the graves with voices.

February 9, 2017

The Samizdat

Hey! My name is Andrew Kozma, and if you are reading this blog post, you probably know who I am, or who I have been, or who I wish to be. Namely, a writer, a poet, a novelist.

Apologies for the forced cheer. Sometimes forced cheer is all you can manage, and forced cheer is better than no cheer. (It is not. -Ed.)

I’m writing this because I’m starting on a scary and exciting new project called The Samizdat, and I want you to come along with me on this journey. The project: A blog/journal/thing of political poems by me and other guest poets, where the money raised (through Patreon) will be split between the poet and charity.

In some ways, I don’t want to be writing this. The horrors that have happened in the country over the past months/year–well, I just want them to go away. I want the Drumpf to stop being Drumpf-like. I want people to be safe, for them to be able to enter and leave the country as they wish, for mothers not to be deported away from their daughters and lovers, for treaties with Native Americans and foreign powers to be honored. I want the country I love to stop descending into madness.

And yet, what I’ve realized is that there are people who have been living in this state of mind for their entire lives. The Standing Rock Sioux and other Native American nations standing with NoDAPL, this struggle is nothing new to them. All of those who started Black Lives Matter did so because of the prejudice and hate they’ve been dealing with for decades. Even if Drumpf and his crew were gone tomorrow, so many struggles would remain and would need to be fought against.

That’s what I want The Samizdat to be: a method of using that art (and the joy/hope/awareness it engenders) to make the world a better place. Below is all the information you’ll find on the Patreon page. There is no poem up yet; since the goal is to use poetry to raise money for both artists and charity, it doesn’t seem to make sense to publish any poem until there’s money to be distributed. So I’m putting out this call and will be publishing the first poem to The Samizdat next Friday. If you want to support artists and political art and various charitable causes (needed even more now that the federal and state governments are cutting funding for arts and social welfare programs), then join me here: The Samizdat.

THE MANIFESTO

All art is political.

In some cultures and in some circumstances, this is more apparent. Writers in China and Saudi Arabia have been imprisoned for their words and, in many cases, for the very act of writing something not approved by the government. In the United States, for example, the McCarthy era destroyed careers for artists who spoke out against the Communist witch hunt of the time.

And it’s possible that we are heading towards such a crisis again.

In the USSR, during the long totalitarian rule of that country, people were born into oppression and died in repression. Anything a citizen said could be and would be used against them. Typewriters were registered and marked each with an individual fingerprint so that the authorities could discover who had written any seditious material. In this climate, writing anything was a risk, and a political act.

Russian writers and philosophers and critics who wanted to flout government censorship wrote their pieces in secret and passed what they’d written to others in secret. Those others took on the obligation of retyping what they’d received or copying it out by hand and sending their new copies onward to other readers. Reading these secretly-shared, non-government-approved, and therefore subversive texts was dangerous. Being in possession of them was a crime.

This is the spirit I’m trying to recreate with The Samizdat, writing and publishing and distributing political poetry that talks to and around and within what is going on in the world today. Poetry is not just food for the soul, it is fuel for revolution. It is a lens that changes the way you perceive the world and your place in it.

THE ACTION PLAN

The Samizdat promises to deliver political poems directly to you, up to four times a month. The first poem of every month will be mine–the other three will be guest poets. The line up so far includes Sasha West and Joshua Gottlieb-Miller.

Because politics is not just about words but also about actions, half of your pledge will go towards a charity of the contributing poet’s choice (the pledge being the total minus Patreon’s fees), the possible charities listed in that poet’s bio. Afterwards, I will post how much money was raised and where it went. My goal here is to be as transparent as possible in supporting poetry and those causes we, as a community, believe in.

The Samizdat has two baselines of support. The first is a one-dollar pledge that gets you the poem and access to any extras posted through the Patreon. The second is a twenty-dollar pledge which will get you a poem directly mailed to you. Because of the way Patreon works, you can change your pledge level at any time so that if you want mailed copies of only those poets you prefer, that will be easy to arrange.

We are entering a world where art and dissent are under attack. Here is your chance to support both.

January 24, 2017

The Women’s March

[image error]

The crowd was unbelievable. And simply because I’m a person limited to a person’s POV (and relatively short, at that) I couldn’t see the end to us, all of the women and men and others gathered in DC to march in protest and solidarity. I’d jump and see an ocean of faces and signs, pussy hats and uncovered heads, of all different colors. Marchers perched in the winter-shorn trees like birds. Stood on buses. Held signs up for all to see until their arms burned. When one voice rose, dozens of others joined around her. Thousands of voices rose.

We rode a bus from Houston, and a bus back from Houston, a day on the bus spent either way. We stopped for fuel of both the body and the bus. We talked to cashiers who said they feared the world was going to be set on fire by Trump. If so, we are the fire. We need to be that fire.

Outside DC, our bus passed other buses. The sidewalks were full of pink hats and wide, brightly-colored signs. A tiding of magpies. A force of women.

The Metro stations were full. Hundreds, thousands, hundreds of thousands funneling through to the center of DC, to spread out and occupy the seat of power of our nation.

Of many nations. Of many states. Of many counties and parishes. Of many cities.

[image error]

The Metro opened earlier than normal. There were more trains added for the day. Our train was full when we entered at the last stop on the Blue Line. Every stop, more pink hats, more signs, more people added. We were pushed in until no more could be pushed, until we were one person. One body moved and the rest swayed. One breathed, and we all breathed. Our hearts pumped. Our hearts beat.

The speaker said, “People.” We chanted, “Power.”

People. Power.

Power. The single voice resounded through the city. The sound was physical. It secured us to the ground, rooted us in the earth. It lifted us up. Our voice could lift up those government buildings around us, open the doings inside to the glare of the sun, and let us in to take our rightful place.

If nothing else, I know because we know that we are not alone because I was there and I saw you and you saw me and we saw each other.

We saw each other.

We were there to march. There were too many people to march. We marched in place. We chanted and held our signs high and moved inches, moved a foot at a time, slowly through the crowd of us. Others found their way to march. A crowd of thousands filled the blocks along Pennsylvania and were turned back by a security gate, but circled, a constant stream of protest and people and songs.

Our signs were our voices when our voices were silent. We strung them into fences and through metal bars so our voices would speak without us. We laid them at the feet of the Trump hotel, a memorial for everyone who was there, a dialogue between those that have power and those elected to represent us.

[image error]

A voice unanswered is still a voice.

A voice answered is still a voice.

16. A voice cannot stop voicing.

December 16, 2016

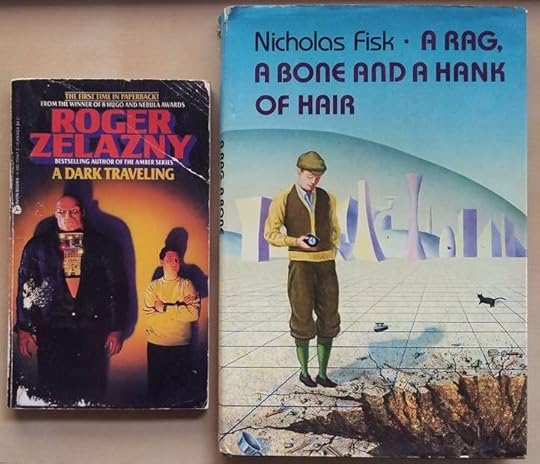

A Nostalgia I Never Had: William Sleator vs. Roger Zelazny and Nicholas Fisk

I really like William Sleator (his books are a nostalgia I had, specifically INTERSTELLAR PIG and THE BOY WHO REVERSED HIMSELF). He has books which are amazing, such as HOUSE OF STAIRS and THE LAST UNIVERSE, and books which are not, like TEST. However, his best books are horrifying and utterly raw, with none of the characters being able to hide behind a lack of self-knowledge. The teens in his novels are presented in a stark light that shows all their strengths and flaws, and he lets them hang themselves with their own thoughts and words.

Once in an article about Sleator, I found him compared to Nicholas Fisk, a British science-fiction who, like Sleator, also mainly wrote for children. So I picked up A RAG, A BONE AND A HANK OF HAIR (a title that conveniently leaves out the Oxford comma, which is ironic? Maybe? Should I be quiet now?). The second book in the photo above is by Roger Zelazny, one of my favorite writers, and an author who I never knew wrote books for children. The closest I’d come before was A NIGHT IN THE LONESOME OCTOBER, which was a light book, more of a romp than an adventure, but still clearly in the adult category.

(Now is the point to say that I’m not sure what that means in reference to myself and my own reading since I’ve been into Zelazny since early High School, if not Intermediate School, and so he was, in effect, my YA.)

I’ll take on Zelazny first because reading this book was like reading Sleator’s TEST, except that I was able to finish it. A DARK TRAVELING reads as a book written to a young audience by a writer who thinks this is what a young audience wants to read. The plot is bare bones thin, the characters uncomplicated, the struggles slight, and the writing–which Zelazny often makes beautiful and haunting–is flat, dead on the page. I can’t even give you a summary of the plot here because it vanished so completely from my mind after I finished. I mean, it involved witches, werewolves, aliens, multiple worlds, mechanical golems, all of it hodgepodged together in a way that provided no coherence, mainly because there was no room to build that coherence. In 151 large-font pages you can’t do much world-building, and Zelazny doesn’t, instead relying on ideas somewhat explored in the AMBER series (i.e., in a multi-verse everything exists somewhere). Zelazny is one of the writers I want to build a complete collection for, but I won’t be adding this to that collection.

It’s disappointing to be disappointed, especially with a writer I know and love (the work, I mean, as I have no idea what Zelazny the man was like). It’s an entirely different experience to be disappointed by a book you have little-to-no expectations for. A RAG, A BONE AND A HANK OF HAIR falls on this line with a boy tasked with infiltrating a group of people recreated from before civilization ended (i.e., now, apparently) who are being studied by scientists for…reasons. The scientists used science to reconstruct these people from organic refuse they found in the ruins, which somehow also recreated the kind of people they were and how they lived at the time.

Which is…whatever. Internal hand-waving aside, I don’t really care much about science in books as long as it’s internally consistent with the story. I’ll take this as science fantasy and be fine with it–and I am fine with it. Like Sleator, Fisk’s story is brutally dark and unapologetic in how it depicts people, especially the main character. To my mind, the world depicted is a little thin, but that makes it more like a dream than a literal accounting, more a nightmare mood piece than a beware-this-could-happen.

For whatever reason, I just didn’t fall for Fisk’s voice here. It’s good writing (unlike, I have to say it, Zelazny’s book) but maybe it’s too clinical for me? One aspect of Sleator’s writing is that he puts you in the head of his characters completely, not thinking their thoughts, but witnessing those thoughts and their actions from inside their bodies and minds, so you can’t help but see them as hopeful, petty, brave, and flawed.

In these books, both Zelazny and Fisk keep the reader at a distance, which means it’s hard to create empathy with the characters as real people. And now, more than ever, we need Sleator’s kind of empathy as practice for the real-life necessity and moral responsibility of seeing other people as real people. Lives depend on it.

*Really, if nothing else, you should read HOUSE OF STAIRS. Here’s a link. Go buy.

October 26, 2016

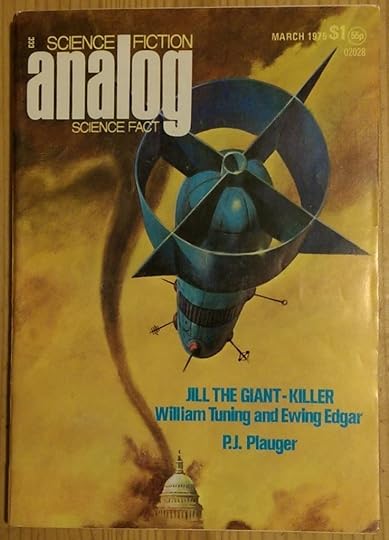

Analog March 1975

This is one of those several months after the facts book reviews, so if it sounds like a dream being recounted in a dream, that’s why.

“Jill the Giant-Killer” by William Tuning and Ewing Edgar: Most noticeable here are the fact of the scientist heroine overcoming sexism both in the larger culture and in scientific circles in particular in order to achieve her dream of stopping tornadoes through using tactical missile strikes delivered by fighter planes. Also noticeable, how simply and acutely boring this story is. It epitomizes all the strikes against Hard SF, especially in the use of technical specifications as though they are innately interesting and flat, nearly dead language.

“Building Block” by Sonya Dorman: This story, compared to the last, is actually quite fascinating even if both are relying on very little action in the story themselves. Here, though, character is key. Arachne is a designer of space homes, expensive but highly desired homes in low orbit around the planet, and she’s suffering a creative block. The story simply follows her as she attempts to overcome that block, and, eventually, almost by accident she does. Despite not much happening in the story, it held my interest because Arachne is fascinating.

“Child of All Ages” by P. J. Plauger: Another fascinating story, which made me feel like I was winning with this issue (as opposed to the others, which provided mostly stories to slog through, up to my ankles in it–then again, “Jill the Giant-Killer” took up a third of this issue and was the slog to beat all slogs, so sloggy I’m still scraping slog off my shoes). Here is a child who is immortal, but is immortal always as a child. She can die. She can be studied by science, and dissected to see what makes her tick, and so she continually needs to find a new family to protect her, to adopt her as their child, until they–as they always do–become scared by the fact that she doesn’t age. It’s a sad story, one embedded with loneliness, but worth the read.

“Lifeboat” (part 2 of 3) by Gordon R. Dickson and Harry Harrison: Spoiler: Our main character did it. He exploded the bomb that destroyed the ship that trapped him and all the survivors on the titular lifeboat. Other than that revelation, the story continues with its sexism and classism and the insistence that we identify with the main character even when he’s a complete tool. I will not, sir. I will not.

“Mail Supremacy” by Hayford Peirce: A joke story using the RETURN TO SENDER response from the post office to kickstart interstellar communication and bring humanity into galactic society. It’s three pages longer than it needs to be, at three pages.