Kathy McCoy's Blog, page 4

May 10, 2018

From Summer to Autumn, Sunrise, Sunset

I'll never forget my introduction to the Kennedy Center in Washington, D.C. It was a lovely, crisp autumn night in the early summer of my adulthood.

I was in Washington on an assignment for a national magazine. I had just had a wonderful dinner at the Alexandria, VA home of Tim Schellhardt, my best friend from college, his gracious wife Barbe and their beautiful baby daughter Laura. Tim was White House correspondent for The Wall Street Journal, the job of his dreams. Life was incredibly good.

As he drove me back to my hotel, Tim said "Oh, wait! I want to show you something!" We stopped at the Kennedy Center and walked around the place, marveling at its beauty and at the artistic wonders offered on its fall schedule. We talked and laughed and Tim exuberantly raced a total stranger up the down escalator there. Life was filled with youthful energy and promise that lovely night when we were barely 30 years old.

Those were heady times -- with our careers on the ascent, so much of our lives ahead.

Tim and Barbe would have more children -- with Mary Kate, Eliza and Stephen arriving in the next seven years.

I would marry Bob Stover two years after our Kennedy Center adventure and write my first book -- an award winning best seller -- two years after that.

Bob would become a Big Brothers volunteer for 22 years and his third Little Brother, 9-year-old Ryan Grady, who called himself our "surrogate son", would become a pivotal part of our lives. He and Bob spent many hours together -- exploring, arguing, laughing, teaching each other so many things. As a teenager, Ryan helped me to study for my oral licensing exam to become a psychotherapist and, in the process, declared that he wanted to do this, too, one day.

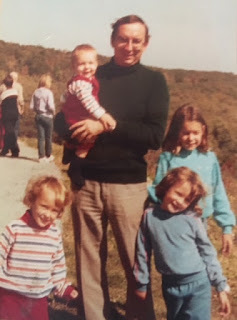

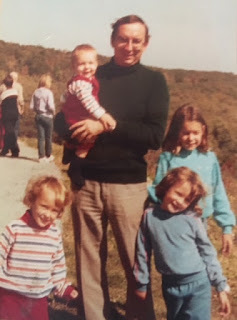

Tim back in the day with (clockwise) Laura, Mary Kate, Eliza and baby Stephen

Tim back in the day with (clockwise) Laura, Mary Kate, Eliza and baby Stephen

Bob and I never had children, thus no grandchildren, though my brother Mike's late-in-life kids with his wife Jinjuta -- Maggie, 8, and Henry, 5 -- are a wonderful substitute. It's fascinating to see them grow and develop into quite distinct individuals. I look at Maggie's face and catch fleeting glimpses of the strong, socially adept, beautiful woman she will be someday. I see fierce intelligence and wry humor in Henry that are far beyond his chronological years and a fascinating look at the man he will grow up to be.

Henry and Maggie near their home in Bangkok, Thailand

Henry and Maggie near their home in Bangkok, Thailand

For a long time, with all of the younger generation, we would seek such glimpses into the future. But now, increasingly, the future is here. Oh, Tim and I are still writing. We did a lot of talking and laughing as we visited during our 50th college reunion last fall. Bob still enjoys long talks and recreational arguments with Ryan. He was Ryan's Best Man at his wedding last summer.

Bob, far right, as Best Man at Ryan's wedding

Bob, far right, as Best Man at Ryan's wedding

But something has changed.

The babies of our youth are in the sweet summer of their own adult lives, with careers on the ascent and growing families and strong shoulders and patient listening ears for....us?

When did that happen? When did we start depending emotionally on them? When did we first seek out their advice? When did we start stepping back to admire their career and life accomplishments which have slowly, but steadily, begun to eclipse our own? And how could we have guessed what a joy that would be?

It's fascinating to watch another person grow from helpless infancy to competent adulthood. One can always remember the full life span -- seeing a glimpse of the dimpled toddler in the woman, the loquacious child in the man. And, even while still basking in the sunshine of one's own life, the chill of autumn is unmistakable. Our steps are slower, more cautious. Our futures don't stretch endlessly, luxuriously, through decades. We entertain less engaging "What if's" as we plan the rest of our lives with Power of Attorney documents and Living Wills and trusts. We deal with the nagging physical limitations of time. We watch dear friends die and become a bit more reconciled to our own mortality. And so much of the focus has turned away from ourselves and onto the triumphs and wisdom of the young people we love.

My friend Mary Breiner, whose husband John passed away recently, enjoys the company, comfort and counsel of their three adult children Matt, Liz and Katie, their loving spouses Patti, Nigel and Josh and the grandchildren who are growing up so quickly and wonderfully. Two days after John's death, just before Christmas, Mary's beloved niece Monica Fulton appeared at her door with a little Christmas tree, hugs and words of love. Mary's children and grandchildren, nieces and nephews love and worry and advise and reach out to her, to support her through the grief and her transition to a new and very different life.

Mary Breiner and her niece Monica Fulton, who brought her love and Christmas cheer.

Mary Breiner and her niece Monica Fulton, who brought her love and Christmas cheer.

And when we faced an unsettling family crisis not long ago, Bob turned to me and said "We need to call Ryan and get his advice. He'll know what to do...."

And it was true: Ryan did fulfill that long ago dream to become a psychotherapist, too. He is a licensed clinical social worker in L.A. and is director of a social service agency. Was it only a few years ago that he and Bob would argue about job interview logistics and management practices? Now Bob marvels at his competence and vision. And, after an hour on the phone with him, discussing our distress over my sister's medical and financial crises, he gave wise, practical and spot-on advice -- and once again, expressed his love and support.

Ryan Grady, all grown up and source of comfort and wisdom

Ryan Grady, all grown up and source of comfort and wisdom

And I marvel, too, at my friendship with Tim's daughter Mary Kate, a film and television actress in Los Angeles. Whenever I'm in town, we have long lunches and delightful visits together, talking about our lives, advising each other, laughing like old friends. She talks about her joy in being able to help her parents in little ways -- assisting her mother after knee surgery, taking her father to the beach for some serious de-stressing. And we talk about her love for her very special siblings -- Eliza, a gifted musician who is happily married and the mother of two lovely and thriving little daughters with a third on the way; Stephen, who has a wonderful marriage and a busy career as an actor/singer/director/choreographer in Chicago and who also teaches musical theatre at Northwestern University where Tim and I met and became lifelong friends more than 50 years ago. And Stephen is not the only Schellhardt on the NU faculty. Laura, an award-winning playwright, heads the undergraduate playwriting department at Northwestern, is happily married and the mother of a delightful four-year-old son. She and her husband just bought their first home in suburban Chicago.

Mary Kate Schellhardt, a treasured friend

Mary Kate Schellhardt, a treasured friend

Stephen Schellhardt with dad Tim, all grown up and excelling

Stephen Schellhardt with dad Tim, all grown up and excelling

Life is incredibly good.

Tim recently returned to the Kennedy Center. He no longer lives and works in the Washington area. He is a public relations executive in Chicago and just beginning, at age 73, to imagine retirement. But something special drew him back to Washington recently: the debut of one of Laura's plays, the first of two that will be produced this year -- at the Kennedy Center.

Tim at Kennedy Center between posters for two of his daughter Laura's plays

Tim at Kennedy Center between posters for two of his daughter Laura's plays

Summer into autumn...feeling the aches and pains of age, the limitations of time...but who knew how warmed we would feel against that chill as we marvel at the talent and love and wisdom of those who follow us.

I was in Washington on an assignment for a national magazine. I had just had a wonderful dinner at the Alexandria, VA home of Tim Schellhardt, my best friend from college, his gracious wife Barbe and their beautiful baby daughter Laura. Tim was White House correspondent for The Wall Street Journal, the job of his dreams. Life was incredibly good.

As he drove me back to my hotel, Tim said "Oh, wait! I want to show you something!" We stopped at the Kennedy Center and walked around the place, marveling at its beauty and at the artistic wonders offered on its fall schedule. We talked and laughed and Tim exuberantly raced a total stranger up the down escalator there. Life was filled with youthful energy and promise that lovely night when we were barely 30 years old.

Those were heady times -- with our careers on the ascent, so much of our lives ahead.

Tim and Barbe would have more children -- with Mary Kate, Eliza and Stephen arriving in the next seven years.

I would marry Bob Stover two years after our Kennedy Center adventure and write my first book -- an award winning best seller -- two years after that.

Bob would become a Big Brothers volunteer for 22 years and his third Little Brother, 9-year-old Ryan Grady, who called himself our "surrogate son", would become a pivotal part of our lives. He and Bob spent many hours together -- exploring, arguing, laughing, teaching each other so many things. As a teenager, Ryan helped me to study for my oral licensing exam to become a psychotherapist and, in the process, declared that he wanted to do this, too, one day.

Tim back in the day with (clockwise) Laura, Mary Kate, Eliza and baby Stephen

Tim back in the day with (clockwise) Laura, Mary Kate, Eliza and baby StephenBob and I never had children, thus no grandchildren, though my brother Mike's late-in-life kids with his wife Jinjuta -- Maggie, 8, and Henry, 5 -- are a wonderful substitute. It's fascinating to see them grow and develop into quite distinct individuals. I look at Maggie's face and catch fleeting glimpses of the strong, socially adept, beautiful woman she will be someday. I see fierce intelligence and wry humor in Henry that are far beyond his chronological years and a fascinating look at the man he will grow up to be.

Henry and Maggie near their home in Bangkok, Thailand

Henry and Maggie near their home in Bangkok, ThailandFor a long time, with all of the younger generation, we would seek such glimpses into the future. But now, increasingly, the future is here. Oh, Tim and I are still writing. We did a lot of talking and laughing as we visited during our 50th college reunion last fall. Bob still enjoys long talks and recreational arguments with Ryan. He was Ryan's Best Man at his wedding last summer.

Bob, far right, as Best Man at Ryan's wedding

Bob, far right, as Best Man at Ryan's weddingBut something has changed.

The babies of our youth are in the sweet summer of their own adult lives, with careers on the ascent and growing families and strong shoulders and patient listening ears for....us?

When did that happen? When did we start depending emotionally on them? When did we first seek out their advice? When did we start stepping back to admire their career and life accomplishments which have slowly, but steadily, begun to eclipse our own? And how could we have guessed what a joy that would be?

It's fascinating to watch another person grow from helpless infancy to competent adulthood. One can always remember the full life span -- seeing a glimpse of the dimpled toddler in the woman, the loquacious child in the man. And, even while still basking in the sunshine of one's own life, the chill of autumn is unmistakable. Our steps are slower, more cautious. Our futures don't stretch endlessly, luxuriously, through decades. We entertain less engaging "What if's" as we plan the rest of our lives with Power of Attorney documents and Living Wills and trusts. We deal with the nagging physical limitations of time. We watch dear friends die and become a bit more reconciled to our own mortality. And so much of the focus has turned away from ourselves and onto the triumphs and wisdom of the young people we love.

My friend Mary Breiner, whose husband John passed away recently, enjoys the company, comfort and counsel of their three adult children Matt, Liz and Katie, their loving spouses Patti, Nigel and Josh and the grandchildren who are growing up so quickly and wonderfully. Two days after John's death, just before Christmas, Mary's beloved niece Monica Fulton appeared at her door with a little Christmas tree, hugs and words of love. Mary's children and grandchildren, nieces and nephews love and worry and advise and reach out to her, to support her through the grief and her transition to a new and very different life.

Mary Breiner and her niece Monica Fulton, who brought her love and Christmas cheer.

Mary Breiner and her niece Monica Fulton, who brought her love and Christmas cheer.And when we faced an unsettling family crisis not long ago, Bob turned to me and said "We need to call Ryan and get his advice. He'll know what to do...."

And it was true: Ryan did fulfill that long ago dream to become a psychotherapist, too. He is a licensed clinical social worker in L.A. and is director of a social service agency. Was it only a few years ago that he and Bob would argue about job interview logistics and management practices? Now Bob marvels at his competence and vision. And, after an hour on the phone with him, discussing our distress over my sister's medical and financial crises, he gave wise, practical and spot-on advice -- and once again, expressed his love and support.

Ryan Grady, all grown up and source of comfort and wisdom

Ryan Grady, all grown up and source of comfort and wisdom And I marvel, too, at my friendship with Tim's daughter Mary Kate, a film and television actress in Los Angeles. Whenever I'm in town, we have long lunches and delightful visits together, talking about our lives, advising each other, laughing like old friends. She talks about her joy in being able to help her parents in little ways -- assisting her mother after knee surgery, taking her father to the beach for some serious de-stressing. And we talk about her love for her very special siblings -- Eliza, a gifted musician who is happily married and the mother of two lovely and thriving little daughters with a third on the way; Stephen, who has a wonderful marriage and a busy career as an actor/singer/director/choreographer in Chicago and who also teaches musical theatre at Northwestern University where Tim and I met and became lifelong friends more than 50 years ago. And Stephen is not the only Schellhardt on the NU faculty. Laura, an award-winning playwright, heads the undergraduate playwriting department at Northwestern, is happily married and the mother of a delightful four-year-old son. She and her husband just bought their first home in suburban Chicago.

Mary Kate Schellhardt, a treasured friend

Mary Kate Schellhardt, a treasured friend

Stephen Schellhardt with dad Tim, all grown up and excelling

Stephen Schellhardt with dad Tim, all grown up and excellingLife is incredibly good.

Tim recently returned to the Kennedy Center. He no longer lives and works in the Washington area. He is a public relations executive in Chicago and just beginning, at age 73, to imagine retirement. But something special drew him back to Washington recently: the debut of one of Laura's plays, the first of two that will be produced this year -- at the Kennedy Center.

Tim at Kennedy Center between posters for two of his daughter Laura's plays

Tim at Kennedy Center between posters for two of his daughter Laura's plays Summer into autumn...feeling the aches and pains of age, the limitations of time...but who knew how warmed we would feel against that chill as we marvel at the talent and love and wisdom of those who follow us.

Published on May 10, 2018 10:04

May 1, 2018

Saying Goodbye to Someone Special

"This isn't an easy time of life, is it?" wrote my friend Roxanne Camron, former editor of 'TEEN Magazine, where we worked together for nearly a decade in our youth. She was writing in the wake of two recent deaths -- that of our 'TEEN colleague Jay Cole, so eternally active and youthful until his recent medical decline, who had died three weeks ago and that of my former long-time literary agent Susan Ann Protter, a genuine force of nature, who passed away on April 26.

No, it isn't an easy time. It's hard enough to say "Goodbye" to our parents, aunts, uncles and older friends. But there is something particularly poignant about the loss of a peer -- something that is happening with increasing frequency these days. And there are times when the death of a special peer takes not only a beloved friend but also a piece of one's own history.

Susan Ann Protter 1939-2018

Susan Ann Protter 1939-2018

That's very much the case with the death of Susan Ann Protter. She was my literary agent for more than 30 years and, not so incidentally, a dear friend with an amazing array of talents, strengths, quirks and eccentricities that made time with her so special -- and for great stories as well. All of her friends and clients had tales of her fits over the small stuff (a bad hair day, a botched manicure that, as one friend said recently, "could send her into a tizzy"). But there was so much more. She could be blunt with her feedback on proposals and manuscripts, a trait I came to appreciate greatly. She was tender in her support of a client in crisis and fierce in her defense of a client and/or treasured friend. There were times, over the decades, when we had impassioned differences -- to the extent that I left her agency twice for brief periods only to return to a warm welcome each time. Susan's clients were like family to her. With the passage of time and with greater wisdom, I realized that whenever we disagreed, Susan was almost always right. And she had the grace never to say "I told you so!"

Our history together dates back to late 1976. I was a young editor at 'TEEN Magazine, eager to break into writing books. I had been asked by a New York psychologist/author, whom I had met the year before while he was in L.A. promoting a book he had done with another writer, to be his co-author on a book of advice for teenagers. Our long-distance work with each other on the book proposal was fraught. We didn't agree on some core issues and made some uneasy compromises in our proposal. And he kept losing literary agents, about one a month, but kept writing me letters putting a positive spin on it, insisting that THIS new agent would be the one to make our proposed book a big hit. The sixth agent in as many months was someone I had never heard of: Susan Ann Protter. I was outraged. I sat down and wrote the psychologist an angry letter telling him how tired I was of the high agent turnover, how I wanted this agent's feedback on our proposal and wanted more information on her professional credentials. He had the presence of mind to show this letter, meant for his eyes only, to Susan.

She called me immediately. I asked what she thought of our proposal.

"Your proposal?" she bellowed. "It sucks! Bury it! Burn it! And while you're at it, forget about this partnership. The good doctor is bad news. Would you believe that he offered to get me dates with five eligible New York bachelors if I sold your proposal? So insulting! I was ready to wash my hands of both of you, but he just brought me your angry letter and it's a revelation: you really CAN write! So do you have any ideas for another book, either alone or with someone else?"

Actually, I did. But it wasn't as easy as just saying "Yes!"

For several years, Dr. Charles Wibbelsman, 'TEEN's "Dear Doctor" columnist (as well as a pediatrician with a specialty in adolescent medicine), and I had talked about collaborating on a health and sexuality book for teens. We envisioned a kind of adolescent "Our Bodies Ourselves." But now there was a problem. In the course of our work together at 'TEEN, Chuck and I had fallen in love. We had talked of marriage, a family and a lifetime of writing books together. Then, at age thirty, he came to the painful conclusion that he was gay. He had met a special man and they moved to San Francisco to begin a new life together. Our parting had been devastating for me, heart-breaking and tempestuous for both of us. We were barely speaking at that point. Yet here was a chance to make at least one of our shared dreams come true. I called him.

We wrote the proposal within a few weeks and sent it to Susan. She took it directly to Simon and Schuster/Pocket Books where it sold immediately. We had a year to write it. It wasn't an easy year for either of us or for Bob Stover, the book's illustrator, whom I married during that memorable time. But the result was "The Teenage Body Book", an award-winning, critically acclaimed best seller when it came out in 1979. It has been continuously in print with seven U.S. editions, the latest in 2016, and five foreign editions. It established my career as an author, gave a boost to Chuck's career as a medical expert on adolescents, rescued our loving friendship and started us on our journey of hard work, friendship and laughter through the years with our agent Susan. Chuck and I wrote three other books together as well as the seven editions of "The Teenage Body Book." I also wrote a number of books on my own. And Susan was a huge part of all of that history.

She visited us in California. We saw her often in New York. She offered me a place to stay at her apartment on Central Park West when, in the early days, I would come to New York to meet with magazine editors for assignments and publishers to discuss new book projects. We would talk for hours into the night in those years and I loved getting to know her history. She was the only child of devoted but unusual parents. They had been committed Communists when Susan was growing up. Her father was a highly successful labor lawyer, her mother a political activist. She sometimes bemoaned growing up in a house filled with secrets due to her parents' political leanings, but she treasured who they were. And they loved her unconditionally -- in all her outrageousness.

Once, I joined Susan and her parents at the parents' home in Long Island for a Passover dinner. As was her wont, Susan criticized everything about the food -- from the brisket to the gefilte fish. Her mother rolled her eyes and turned to her father. "Ah, Marcy," she said. "How did we spawn this...?" And all three threw back their heads and brayed with laughter. It was a wonderful evening.

Political activism was in Susan's blood and she honored that to the end -- attending a student-led demonstration against guns a little over a month before her death. She was in a wheelchair and with her live-in medical aide, but she was there. She was fully engaged with her life passions -- from opera and classical music to travel and sampling exotic cuisines -- to the end of her life, attending a New York Philharmonic performance only a few days before her death. She had majored in French at Syracuse, earning a Master's degree and teaching briefly before heading into a career in publishing. She was one of the first independent agents in New York and it was the perfect niche for her. She was a terrific agent: nurturing, assertive, and fearless.

Susan at dinner in Scottsdale, AZ in 2011

Susan at dinner in Scottsdale, AZ in 2011

I always admired her singular courage -- so evident in her traveling to Cuba through Canada back in the day or taking on a problematic publisher. Friends observed that while she was the queen of kvetching about the small stuff -- from tables at restaurants (she would change tables 3 or 4 times typically) to food (which she always always sent back) to small annoyances, she was incredibly brave as she faced her snowballing health problems during the last decade of her life. She had a rare blood cancer, cardiac issues and back problems requiring many surgeries and grueling medical procedures. By 2011, ill health forced her into retirement and she closed her agency. That same year, she visited Bob and me at our new home in Arizona when she came to the Mayo Clinic in Scottsdale for consultations about her blood cancer.

Susan and I at the Mayo Clinic in 2011

Susan and I at the Mayo Clinic in 2011

A few years later, she had a stroke that left her legally blind. She had increasing trouble walking and was confined to a wheelchair during the past few years. I never admired Susan's courage more than I did during this time of declining health. She was always amazingly nonchalant about the big challenges in her life and lived with gusto through all of it, even while continuing to complain only about the small stuff.

I talked with her on the phone regularly, but the last time I saw her was in June 2015. I was in New York for a speaking engagement and to meet with my wonderful new agent, Stephany Evans, to whom Susan had introduced me. Chuck joined me in New York just for fun, in celebration of my 70th birthday. He bought tickets for us to several Broadway shows I had been eager to see. He arranged for Susan to join us for dinner one of those nights and to go with us to see "Fun Home." The three of us had a wonderful time that night -- talking, arguing, kvetching, laughing. For old times sake, I teased her about her distinctive New York accent, imitating some of its more salient features, and she did the same with my California accent. We reveled in our silliness. And we talked seriously of new realities. Susan was frail. She was legally blind and carried a white, red-tipped cane. She was close to needing a wheelchair and leaned heavily on both of us for support as we walked to the theater. But she was as fun, outspoken and exuberant as ever. Chuck and I both treasure the memory of that lovely summer evening.

Susan, Chuck and I in New York, June 2015

Susan, Chuck and I in New York, June 2015

We reminisced about that evening and about our long history with Susan on the phone yesterday as we consoled each other. "Susan was such a bright, sophisticated, cosmopolitan lady who always told it like it was," he said. "I will miss her so much -- that deep chortle of hers, that great New York accent -- just...her. There was such caring...a special kind of love..."

We talked of our gratitude for and to Susan -- for her role in making our books possible, for giving boosts to both our careers, for her caring friendship, for her part in bringing us back together, out of heartbreak and into a loving, lifelong friendship.

Chuck sighed. "This is the end of another chapter of our lives," he said at last. "And it's a reminder to live our lives as fully and joyously as Susan did, every day we have left...."

Susan Ann Protter was so much more than a terrific agent or even a dear friend: she was a vital part of our shared history -- and of our hearts.

No, it isn't an easy time. It's hard enough to say "Goodbye" to our parents, aunts, uncles and older friends. But there is something particularly poignant about the loss of a peer -- something that is happening with increasing frequency these days. And there are times when the death of a special peer takes not only a beloved friend but also a piece of one's own history.

Susan Ann Protter 1939-2018

Susan Ann Protter 1939-2018That's very much the case with the death of Susan Ann Protter. She was my literary agent for more than 30 years and, not so incidentally, a dear friend with an amazing array of talents, strengths, quirks and eccentricities that made time with her so special -- and for great stories as well. All of her friends and clients had tales of her fits over the small stuff (a bad hair day, a botched manicure that, as one friend said recently, "could send her into a tizzy"). But there was so much more. She could be blunt with her feedback on proposals and manuscripts, a trait I came to appreciate greatly. She was tender in her support of a client in crisis and fierce in her defense of a client and/or treasured friend. There were times, over the decades, when we had impassioned differences -- to the extent that I left her agency twice for brief periods only to return to a warm welcome each time. Susan's clients were like family to her. With the passage of time and with greater wisdom, I realized that whenever we disagreed, Susan was almost always right. And she had the grace never to say "I told you so!"

Our history together dates back to late 1976. I was a young editor at 'TEEN Magazine, eager to break into writing books. I had been asked by a New York psychologist/author, whom I had met the year before while he was in L.A. promoting a book he had done with another writer, to be his co-author on a book of advice for teenagers. Our long-distance work with each other on the book proposal was fraught. We didn't agree on some core issues and made some uneasy compromises in our proposal. And he kept losing literary agents, about one a month, but kept writing me letters putting a positive spin on it, insisting that THIS new agent would be the one to make our proposed book a big hit. The sixth agent in as many months was someone I had never heard of: Susan Ann Protter. I was outraged. I sat down and wrote the psychologist an angry letter telling him how tired I was of the high agent turnover, how I wanted this agent's feedback on our proposal and wanted more information on her professional credentials. He had the presence of mind to show this letter, meant for his eyes only, to Susan.

She called me immediately. I asked what she thought of our proposal.

"Your proposal?" she bellowed. "It sucks! Bury it! Burn it! And while you're at it, forget about this partnership. The good doctor is bad news. Would you believe that he offered to get me dates with five eligible New York bachelors if I sold your proposal? So insulting! I was ready to wash my hands of both of you, but he just brought me your angry letter and it's a revelation: you really CAN write! So do you have any ideas for another book, either alone or with someone else?"

Actually, I did. But it wasn't as easy as just saying "Yes!"

For several years, Dr. Charles Wibbelsman, 'TEEN's "Dear Doctor" columnist (as well as a pediatrician with a specialty in adolescent medicine), and I had talked about collaborating on a health and sexuality book for teens. We envisioned a kind of adolescent "Our Bodies Ourselves." But now there was a problem. In the course of our work together at 'TEEN, Chuck and I had fallen in love. We had talked of marriage, a family and a lifetime of writing books together. Then, at age thirty, he came to the painful conclusion that he was gay. He had met a special man and they moved to San Francisco to begin a new life together. Our parting had been devastating for me, heart-breaking and tempestuous for both of us. We were barely speaking at that point. Yet here was a chance to make at least one of our shared dreams come true. I called him.

We wrote the proposal within a few weeks and sent it to Susan. She took it directly to Simon and Schuster/Pocket Books where it sold immediately. We had a year to write it. It wasn't an easy year for either of us or for Bob Stover, the book's illustrator, whom I married during that memorable time. But the result was "The Teenage Body Book", an award-winning, critically acclaimed best seller when it came out in 1979. It has been continuously in print with seven U.S. editions, the latest in 2016, and five foreign editions. It established my career as an author, gave a boost to Chuck's career as a medical expert on adolescents, rescued our loving friendship and started us on our journey of hard work, friendship and laughter through the years with our agent Susan. Chuck and I wrote three other books together as well as the seven editions of "The Teenage Body Book." I also wrote a number of books on my own. And Susan was a huge part of all of that history.

She visited us in California. We saw her often in New York. She offered me a place to stay at her apartment on Central Park West when, in the early days, I would come to New York to meet with magazine editors for assignments and publishers to discuss new book projects. We would talk for hours into the night in those years and I loved getting to know her history. She was the only child of devoted but unusual parents. They had been committed Communists when Susan was growing up. Her father was a highly successful labor lawyer, her mother a political activist. She sometimes bemoaned growing up in a house filled with secrets due to her parents' political leanings, but she treasured who they were. And they loved her unconditionally -- in all her outrageousness.

Once, I joined Susan and her parents at the parents' home in Long Island for a Passover dinner. As was her wont, Susan criticized everything about the food -- from the brisket to the gefilte fish. Her mother rolled her eyes and turned to her father. "Ah, Marcy," she said. "How did we spawn this...?" And all three threw back their heads and brayed with laughter. It was a wonderful evening.

Political activism was in Susan's blood and she honored that to the end -- attending a student-led demonstration against guns a little over a month before her death. She was in a wheelchair and with her live-in medical aide, but she was there. She was fully engaged with her life passions -- from opera and classical music to travel and sampling exotic cuisines -- to the end of her life, attending a New York Philharmonic performance only a few days before her death. She had majored in French at Syracuse, earning a Master's degree and teaching briefly before heading into a career in publishing. She was one of the first independent agents in New York and it was the perfect niche for her. She was a terrific agent: nurturing, assertive, and fearless.

Susan at dinner in Scottsdale, AZ in 2011

Susan at dinner in Scottsdale, AZ in 2011I always admired her singular courage -- so evident in her traveling to Cuba through Canada back in the day or taking on a problematic publisher. Friends observed that while she was the queen of kvetching about the small stuff -- from tables at restaurants (she would change tables 3 or 4 times typically) to food (which she always always sent back) to small annoyances, she was incredibly brave as she faced her snowballing health problems during the last decade of her life. She had a rare blood cancer, cardiac issues and back problems requiring many surgeries and grueling medical procedures. By 2011, ill health forced her into retirement and she closed her agency. That same year, she visited Bob and me at our new home in Arizona when she came to the Mayo Clinic in Scottsdale for consultations about her blood cancer.

Susan and I at the Mayo Clinic in 2011

Susan and I at the Mayo Clinic in 2011A few years later, she had a stroke that left her legally blind. She had increasing trouble walking and was confined to a wheelchair during the past few years. I never admired Susan's courage more than I did during this time of declining health. She was always amazingly nonchalant about the big challenges in her life and lived with gusto through all of it, even while continuing to complain only about the small stuff.

I talked with her on the phone regularly, but the last time I saw her was in June 2015. I was in New York for a speaking engagement and to meet with my wonderful new agent, Stephany Evans, to whom Susan had introduced me. Chuck joined me in New York just for fun, in celebration of my 70th birthday. He bought tickets for us to several Broadway shows I had been eager to see. He arranged for Susan to join us for dinner one of those nights and to go with us to see "Fun Home." The three of us had a wonderful time that night -- talking, arguing, kvetching, laughing. For old times sake, I teased her about her distinctive New York accent, imitating some of its more salient features, and she did the same with my California accent. We reveled in our silliness. And we talked seriously of new realities. Susan was frail. She was legally blind and carried a white, red-tipped cane. She was close to needing a wheelchair and leaned heavily on both of us for support as we walked to the theater. But she was as fun, outspoken and exuberant as ever. Chuck and I both treasure the memory of that lovely summer evening.

Susan, Chuck and I in New York, June 2015

Susan, Chuck and I in New York, June 2015We reminisced about that evening and about our long history with Susan on the phone yesterday as we consoled each other. "Susan was such a bright, sophisticated, cosmopolitan lady who always told it like it was," he said. "I will miss her so much -- that deep chortle of hers, that great New York accent -- just...her. There was such caring...a special kind of love..."

We talked of our gratitude for and to Susan -- for her role in making our books possible, for giving boosts to both our careers, for her caring friendship, for her part in bringing us back together, out of heartbreak and into a loving, lifelong friendship.

Chuck sighed. "This is the end of another chapter of our lives," he said at last. "And it's a reminder to live our lives as fully and joyously as Susan did, every day we have left...."

Susan Ann Protter was so much more than a terrific agent or even a dear friend: she was a vital part of our shared history -- and of our hearts.

Published on May 01, 2018 18:13

April 15, 2018

Convent Mysteries and Memories

For Catholic girls growing up in the 50's, nuns were mysterious and oddly glamorous -- with the long flowing habits, wimples and veils that hid all traces of womanhood and set them apart as special spiritual beings.

From early childhood, some of us dreamed of joining their ranks. When we were in grade school, my friend Pat and I would play for hours, dressed in our makeshift nun's habits. (My brother borrowed mine one Halloween to wear trick or treating and got a candy bonanza and lots of hugs when he showed up at the door of the local convent. The nuns had no idea who was wearing that habit! But that's another story...)

In my early teens, in singular style of teenage rebellion against my non-believing parents, I used to attend daily Mass, pray in the back yard at sunset with my arms outstretched to the heavens and terrorize my parents by sending away for literature about entering a faraway monastery at 14, garnering enthusiastic replies like "Our next entrance date is September 8. Wouldn't it be wonderful if you could join us on that day?" While other parents stressed about keeping their daughters chaste, in school and off drugs, mine strove to keep me from running away to a monastery.

Those attending Catholic high schools got the clear and frequent message that there was no higher calling than dedicating one's life to Christ. Many of us admired our nun teachers greatly and wanted to be like them. And when a schoolmate would enter the convent, it was a major event. When my classmate Sue prepared to become a Dominican sister, I went with her to buy her required orthopedic oxfords, something as exciting in its own way as trying on bridal gowns or a ballet student getting her first pair of pointe shoes.

It all seems to very long ago, lost in the mists of changing times and traditions. But for those of us who lived through the pre-Vatican II era in Catholic schools, there are lingering memories of the mysterious wonder of nuns' lives.

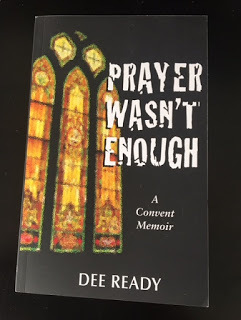

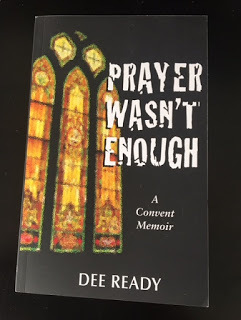

In her new memoir Prayer Wasn't Enough: A Convent Memoir, Dee Ready dispels some of these mysteries, exploring the motivations, the process and the challenges of becoming a nun in the late 1950's and answering some lingering questions.

Why does a young woman, fresh from college and with a lifetime of choices and possibilities ahead, decide to enter the convent?

What process transforms an idealistic young woman into a nun?

What is life like in a religious community?

And what of those who make the painful choice to leave after months or years of striving for spiritual growth and perfection? How does faith continue to grow and thrive after a young woman realizes that the religious life is not her calling after all?

Unlike some of us, entering the convent had not been Dee Ready's dream while growing up in the Midwest. The yearning for perfection evolved during her college years and a transcendent spiritual moment sparked her desire to pursue a path to love and oneness with God and the universe and led to her becoming a Benedictine nun after graduation.

It's a fascinating story of faith and hope, the transformation of youthful idealism and the loss of self taking her down a frightening path of doubt, indecision, anguish and, eventually, mental illness. She doesn't blame the Church or her fellow Sisters. From the perspective of time, healing and emotional growth, the author pinpoints her own crippling hunger for perfection, her flawed misconception of sanctity and her emotional immaturity as primary factors in her struggles.

In many ways, this is a story with which all can identify -- youthful idealism and a search for meaning that collides with the realities of life, whatever path we might have chosen in our lives. But this excellent memoir also offers a glimpse into the mysteries of convent life -- the expectations, the rituals, the daily experiences -- of nuns in those bygone times.

Prayer Wasn't Enough is a compelling, harrowing, ultimately triumphant tale of hope and despair, pivotal, sometimes wrenching, decisions and unexpected new beginnings. It's impossible to put down -- or to forget.

Prayer Wasn't Enough: A Convent Memoir by Dee Ready is available as an e-book or as a print book at Amazon.com.

From early childhood, some of us dreamed of joining their ranks. When we were in grade school, my friend Pat and I would play for hours, dressed in our makeshift nun's habits. (My brother borrowed mine one Halloween to wear trick or treating and got a candy bonanza and lots of hugs when he showed up at the door of the local convent. The nuns had no idea who was wearing that habit! But that's another story...)

In my early teens, in singular style of teenage rebellion against my non-believing parents, I used to attend daily Mass, pray in the back yard at sunset with my arms outstretched to the heavens and terrorize my parents by sending away for literature about entering a faraway monastery at 14, garnering enthusiastic replies like "Our next entrance date is September 8. Wouldn't it be wonderful if you could join us on that day?" While other parents stressed about keeping their daughters chaste, in school and off drugs, mine strove to keep me from running away to a monastery.

Those attending Catholic high schools got the clear and frequent message that there was no higher calling than dedicating one's life to Christ. Many of us admired our nun teachers greatly and wanted to be like them. And when a schoolmate would enter the convent, it was a major event. When my classmate Sue prepared to become a Dominican sister, I went with her to buy her required orthopedic oxfords, something as exciting in its own way as trying on bridal gowns or a ballet student getting her first pair of pointe shoes.

It all seems to very long ago, lost in the mists of changing times and traditions. But for those of us who lived through the pre-Vatican II era in Catholic schools, there are lingering memories of the mysterious wonder of nuns' lives.

In her new memoir Prayer Wasn't Enough: A Convent Memoir, Dee Ready dispels some of these mysteries, exploring the motivations, the process and the challenges of becoming a nun in the late 1950's and answering some lingering questions.

Why does a young woman, fresh from college and with a lifetime of choices and possibilities ahead, decide to enter the convent?

What process transforms an idealistic young woman into a nun?

What is life like in a religious community?

And what of those who make the painful choice to leave after months or years of striving for spiritual growth and perfection? How does faith continue to grow and thrive after a young woman realizes that the religious life is not her calling after all?

Unlike some of us, entering the convent had not been Dee Ready's dream while growing up in the Midwest. The yearning for perfection evolved during her college years and a transcendent spiritual moment sparked her desire to pursue a path to love and oneness with God and the universe and led to her becoming a Benedictine nun after graduation.

It's a fascinating story of faith and hope, the transformation of youthful idealism and the loss of self taking her down a frightening path of doubt, indecision, anguish and, eventually, mental illness. She doesn't blame the Church or her fellow Sisters. From the perspective of time, healing and emotional growth, the author pinpoints her own crippling hunger for perfection, her flawed misconception of sanctity and her emotional immaturity as primary factors in her struggles.

In many ways, this is a story with which all can identify -- youthful idealism and a search for meaning that collides with the realities of life, whatever path we might have chosen in our lives. But this excellent memoir also offers a glimpse into the mysteries of convent life -- the expectations, the rituals, the daily experiences -- of nuns in those bygone times.

Prayer Wasn't Enough is a compelling, harrowing, ultimately triumphant tale of hope and despair, pivotal, sometimes wrenching, decisions and unexpected new beginnings. It's impossible to put down -- or to forget.

Prayer Wasn't Enough: A Convent Memoir by Dee Ready is available as an e-book or as a print book at Amazon.com.

Published on April 15, 2018 12:06

April 9, 2018

Eight Years and Counting

It was eight years ago today that I walked out of my office at UCLA Medical Center for the last time. I was officially retired.

But it quickly became evident that we all have our own, very different, retirement dreams. Though my husband Bob and I left the stress of Los Angeles traffic, selling our home of 29 years and moving to an active adult community in rural Arizona, we settled in to very different retirements. He happily slipped into his dream routine: working out, playing music, reading, doing crosswords and jigsaw puzzles. After taking a six month breather to relax, swim, socialize and indulge in recreational reading, I took another direction: getting back to my original career -- writing. This blog was the first step in my new direction.

What have I learned about retirement in the past eight years?

1. We all have different -- and valid -- visions for retirement. While I revel in the fact that I no longer have to get up before dawn for a hellish commute, I find great joy in work that I love. In the past eight years, I've written three books for major publishers, many blogs and podcasts, and am now writing regularly for PsychologyToday.com. And I'm happy -- even when deadlines loom. I'm not suited for full-time retirement. I'm not cut out for card games and other common pastimes of retirement communities. That doesn't mean that I think my way is the better one. I've come to see the value of engaging in activities one loves -- whether it's golf or MahJong or crafts or volunteering -- without snarky comparisons. Some people want to spend their retirement days enjoying and caring for their grandchildren. Some people have moved to this remote location to put some distance between them, their adult children and daily babysitting duties with the grands. It all works. We all delight in doing exactly what we want.

2. Frugality, within reason, is a good idea. We bought a brand new home with the fantasy that repairs would be minimal for a long time. All those budget projections we made pre-retirement didn't account for the fact that water heaters and appliances in Arizona have dramatically shorter lives than their counterparts in California. The harshness of the water here took out our water heater, in rather spectacular fashion in the middle of the night, after only four years. We've already replaced a refrigerator and a washing machine. Not to mention our complete air conditioning system. Last summer, Bob's car needed thousands of dollars worth of work. Just before Christmas, both of our cars needed new tires. Someday soon, I'll need another dental implant. It's always something. Even when you've planned carefully, even when you're truly okay financially, there can be jolting surprises and some unanticipated adjustments to your budget.

3. Whoever you were before, you'll be in retirement. When Bob and I used to fantasize about retirement, we imagined ourselves in a social whirl in our new community -- active in all manner of classes and events, socializing with neighbors and living a life quiet different from the one we had as two working, commuting, exhausted, mostly solitary people in suburban Los Angeles. And at first, it seemed we were on-track with our fantasy personas. We had parties and outings with neighbors. We worked out at the gym every morning -- with a group of gym buddies -- and spent long, languid afternoons in the outdoor, recreational community pool, talking with friends. But gradually, our daily routine became more familiar: I spent more time working. Bob craved time alone to read. We took fewer classes over time until we weren't enrolled in any. I found that the exercise classes that I had envisioned attending regularly clashed with my writing schedule, especially when I was on a deadline for a book. I found that I preferred working out -- often swimming laps -- in the evenings. As the years have sped by, we seem more and more like our old selves: semi-reclusive, engaged in largely solitary pursuits. Bob occasionally visits our neighbor Wally for an afternoon of talking and laughing. I do the same with my friend Marsha, with whom I have breakfast every Saturday. But usually we're alone -- he in the house, reading, and I in our casita, writing. And it suits us. Just as it suits many of our neighbors to go to parties and dances and group trips.

4. As time goes by, one lets go of one's previous working life and becomes more engaged in cheering on the younger generation. Generatively grows in these years as you celebrate the triumphs of the younger generation. And there are moments of new painful realizations that some of the knowledge or power you once had may be gone forever. I may never again have the level of success or earning power that I enjoyed as a writer in my younger years. Bob still has dreams about work from time to time. But recently, he was shocked to find -- dreaming about giving a seminar once again on hydrologic technology -- that some of his technical knowledge was no longer there. "I'm no longer The Pump God," he told me with a hint of sadness yesterday. "I don't remember...so much. I guess now I'm only The Pump Prince -- or The Pump Jester." At the same time, we both feel tremendous pleasure in seeing the career success and wonderful personal growth of our "surrogate son" Ryan Grady, who is nearly 35 and a licensed clinical social worker and administrator in Los Angeles, with a happy marriage and a lovely new home. It's such a joy to see his successes and also those of the adult children of our friends and to celebrate every one of them.

5. We realize, more than ever, the importance of cherishing each day. Eight years ago, we and our neighbors were healthy and active. Now we've watched, often with a combination of sadness and horror, as lives change irrevocably with illness and growing disability or end, either abruptly or with long suffering. Too many friends have died in recent months and years. And many others will soon follow. Just this morning, Bob got a call from his high school friend Stan, who lives in California, to tell him the bad news he just got from his doctor -- that his congestive heart failure is at the end stage and that there is nothing further they can do for him. Bob himself has had his challenges the past few months: sudden blindness that one doctor diagnosed as dry macular degeneration with a prognosis of lifelong central blindness. A second opinion was more optimistic: the second doctor correctly diagnosed PCO, a common side effect of cataract surgery that is curable with a quick laser procedure. Bob can now see again -- and doesn't take his good fortune for granted for a minute.

We take nothing for granted. We've been very fortunate these eight years. Today, we're still healthy and active. Today, we're solvent and have a home we both love. Today, we can each live our retirement dream. We realize, with new clarity, how quickly everything can change. So each day of health and vigor and discovery is a treasure.

But it quickly became evident that we all have our own, very different, retirement dreams. Though my husband Bob and I left the stress of Los Angeles traffic, selling our home of 29 years and moving to an active adult community in rural Arizona, we settled in to very different retirements. He happily slipped into his dream routine: working out, playing music, reading, doing crosswords and jigsaw puzzles. After taking a six month breather to relax, swim, socialize and indulge in recreational reading, I took another direction: getting back to my original career -- writing. This blog was the first step in my new direction.

What have I learned about retirement in the past eight years?

1. We all have different -- and valid -- visions for retirement. While I revel in the fact that I no longer have to get up before dawn for a hellish commute, I find great joy in work that I love. In the past eight years, I've written three books for major publishers, many blogs and podcasts, and am now writing regularly for PsychologyToday.com. And I'm happy -- even when deadlines loom. I'm not suited for full-time retirement. I'm not cut out for card games and other common pastimes of retirement communities. That doesn't mean that I think my way is the better one. I've come to see the value of engaging in activities one loves -- whether it's golf or MahJong or crafts or volunteering -- without snarky comparisons. Some people want to spend their retirement days enjoying and caring for their grandchildren. Some people have moved to this remote location to put some distance between them, their adult children and daily babysitting duties with the grands. It all works. We all delight in doing exactly what we want.

2. Frugality, within reason, is a good idea. We bought a brand new home with the fantasy that repairs would be minimal for a long time. All those budget projections we made pre-retirement didn't account for the fact that water heaters and appliances in Arizona have dramatically shorter lives than their counterparts in California. The harshness of the water here took out our water heater, in rather spectacular fashion in the middle of the night, after only four years. We've already replaced a refrigerator and a washing machine. Not to mention our complete air conditioning system. Last summer, Bob's car needed thousands of dollars worth of work. Just before Christmas, both of our cars needed new tires. Someday soon, I'll need another dental implant. It's always something. Even when you've planned carefully, even when you're truly okay financially, there can be jolting surprises and some unanticipated adjustments to your budget.

3. Whoever you were before, you'll be in retirement. When Bob and I used to fantasize about retirement, we imagined ourselves in a social whirl in our new community -- active in all manner of classes and events, socializing with neighbors and living a life quiet different from the one we had as two working, commuting, exhausted, mostly solitary people in suburban Los Angeles. And at first, it seemed we were on-track with our fantasy personas. We had parties and outings with neighbors. We worked out at the gym every morning -- with a group of gym buddies -- and spent long, languid afternoons in the outdoor, recreational community pool, talking with friends. But gradually, our daily routine became more familiar: I spent more time working. Bob craved time alone to read. We took fewer classes over time until we weren't enrolled in any. I found that the exercise classes that I had envisioned attending regularly clashed with my writing schedule, especially when I was on a deadline for a book. I found that I preferred working out -- often swimming laps -- in the evenings. As the years have sped by, we seem more and more like our old selves: semi-reclusive, engaged in largely solitary pursuits. Bob occasionally visits our neighbor Wally for an afternoon of talking and laughing. I do the same with my friend Marsha, with whom I have breakfast every Saturday. But usually we're alone -- he in the house, reading, and I in our casita, writing. And it suits us. Just as it suits many of our neighbors to go to parties and dances and group trips.

4. As time goes by, one lets go of one's previous working life and becomes more engaged in cheering on the younger generation. Generatively grows in these years as you celebrate the triumphs of the younger generation. And there are moments of new painful realizations that some of the knowledge or power you once had may be gone forever. I may never again have the level of success or earning power that I enjoyed as a writer in my younger years. Bob still has dreams about work from time to time. But recently, he was shocked to find -- dreaming about giving a seminar once again on hydrologic technology -- that some of his technical knowledge was no longer there. "I'm no longer The Pump God," he told me with a hint of sadness yesterday. "I don't remember...so much. I guess now I'm only The Pump Prince -- or The Pump Jester." At the same time, we both feel tremendous pleasure in seeing the career success and wonderful personal growth of our "surrogate son" Ryan Grady, who is nearly 35 and a licensed clinical social worker and administrator in Los Angeles, with a happy marriage and a lovely new home. It's such a joy to see his successes and also those of the adult children of our friends and to celebrate every one of them.

5. We realize, more than ever, the importance of cherishing each day. Eight years ago, we and our neighbors were healthy and active. Now we've watched, often with a combination of sadness and horror, as lives change irrevocably with illness and growing disability or end, either abruptly or with long suffering. Too many friends have died in recent months and years. And many others will soon follow. Just this morning, Bob got a call from his high school friend Stan, who lives in California, to tell him the bad news he just got from his doctor -- that his congestive heart failure is at the end stage and that there is nothing further they can do for him. Bob himself has had his challenges the past few months: sudden blindness that one doctor diagnosed as dry macular degeneration with a prognosis of lifelong central blindness. A second opinion was more optimistic: the second doctor correctly diagnosed PCO, a common side effect of cataract surgery that is curable with a quick laser procedure. Bob can now see again -- and doesn't take his good fortune for granted for a minute.

We take nothing for granted. We've been very fortunate these eight years. Today, we're still healthy and active. Today, we're solvent and have a home we both love. Today, we can each live our retirement dream. We realize, with new clarity, how quickly everything can change. So each day of health and vigor and discovery is a treasure.

Published on April 09, 2018 15:56

March 23, 2018

Casting Call: A Chance to Help and Be Helped

The casting team at the production company for "Star-Crossed Lovers" sent me the flyer above yesterday, hopeful that among my therapy clients, readers, blogging friends and others, there might be some who are willing to share their experience with differences in a love relationship that are sparking some family disagreements.

They are calling this show "a documentary series", not reality television. The point of the series is not exploitation of conflict and misery but, ideally, resolution or steps toward resolution for couples troubled by family disapproval as they talk with experts about their relationship, their families and the concerns that divide them. Casting director Alex Shaw assured me that the couples chosen for the series will be treated with respect and discretion and that they will also receive good compensation.

Their ideal candidates? While the casting team is open to all types of differences and family disputes, they do hope that those applying will be, above all, genuine and real. You don't have to be young and gorgeous. In fact, those looking for t.v. stardom need not apply. The casting team wants real couples with genuine concerns and a desire, not only to work on their own family divides, but also to help others by sharing their stories and their progress.

There are some requirements:

Since the first season of "Star-Crossed Lovers" will focus on the southeastern U.S., you need to live in either Tennessee or Florida (or perhaps a state adjacent to those two states). You need to be dating and in love but not yet married You should, ideally, be in your thirties or forties, though there is some flexibility with age, especially as the team searches for a couple whose age differences have become a family issue. You need to be available during the shooting months of July and August, though every effort will be made to accommodate work schedules, with much of the shooting done evenings and weekends.

If you, or someone you know, might be interested in being considered for the documentary series, you can contact the casting team at the address at the bottom of the flyer.

They're looking for special people -- and that could well be you and your beloved. It's a chance to get help in working toward your own resolution and family peace while, at the same time, helping more people who are hurting -- and watching -- than you may ever know.

Published on March 23, 2018 15:09

March 16, 2018

The Ghosts That Linger

It doesn't take much to conjure up those long-ago desperate days after my father lost his job -- never to get another one. He was let go from his engineering management position on my thirteenth birthday. With a modest, fully paid for home in an upscale community, we slid into a kind of genteel poverty. On the outside, at least for a time, everything looked as it always had. Inside, there was quiet panic.

"Baby," my father would say, handing me the Sunday L.A. Times classified ads. "Please look and see if there are any jobs. We all have to get jobs. I don't know where our next meal is coming from."

My stomach would tighten as I looked through the ads. There were no jobs listed for females -- the ads were segregated by gender then-- who were younger than 18. I wondered how far babysitting earnings could be stretched to feed a family of five. I loathed babysitting, but longed to make a difference. And I wondered if it could be true that we were in danger of quietly starving to death in a community of abundance.

My brother Mike, then nine years old, seemed to worry less because he saw more options. He quickly got a paper route -- available only to boys in those days -- and that kept expanding. He switched to a larger newspaper with an even bigger route. He earned enough to help out and to start his own savings account -- savings that have only grown over time -- through his years as a paperboy, an Air Force pilot and then as a physician and administrator at major medical centers in the U.S. and abroad. He paid his own way through medical school at Stanford. He owns several homes. He has been prudent and productive, amassing healthy savings. And yet....

"I've always worried about being destitute," Mike told me recently. "From our childhood on. Did it come from Father telling us at a tender age that we all needed to get jobs? My whole life I've never felt safe -- there's always the fear. Actually, it's worse than a fear. It feels more like a knowledge that it's all going to end up badly some day. That's what keeps me working all the time even now."

I nodded. The same ghosts of the past have haunted me. The old destitution terrors have heightened anew as our sister struggles through a dire financial situation, a crisis that seems to embody all of the fears we three have carried through the years.

And it leads me to a truth that is hard to face at times: we may rise above troubled pasts, but pieces of who we've been and what we experienced in times long past do linger into adulthood, into future relationships and on into older age.

It may mean:

Feeling like a perpetual outsider: I had several reasons to feel like an outsider while growing up.

I was in and out of my parochial school in the early grades, battling polio and a subsequent life-threatening respiratory problem. Groups and alliances formed in my absence. I struggled to fit in, particularly when I returned to school full time already in the throes of puberty when I was nine years old. My family's fall into quiet poverty when I was in middle school only added to my feelings of being different.

But all outsiders have their reasons for not fitting in -- maybe shyness, maybe a vulnerability that causes bullies to zero in, being a newcomer to a small town where families have known each other for generations. There are so many reasons triggering feelings of being an outsider in childhood and sometimes for life.

Playing a family role for life. Who were you in your family? The beauty? The clown? The good child? The scapegoat child? The responsible one? A parental confidante and caretaker when you were far too young to take care of yourself, let alone an adult? Who you were then can have a big impact on who you are now.

It may mean that you neglect your own needs while serving others. It may mean that you have unrealistic expectations of others that too often leads to chronic disappointment. It may mean that you try to defuse difficult discussions with jokes or silence, blocking communication with those closest to you. It may mean echoing a long-dead parent's voice with your own children, cringing as soon as the words leave your mouth.

It may also mean conflict as you reflexively fall into a role long outgrown or rendered obsolete by the growth of others. For example, you may still be falling into the role of take-charge (or bossy) older sister or brother with your resentful or dismissive middle-aged siblings.

Carrying a legacy of abuse, whether physical, emotional or sexual. The legacy of abuse is complicated with shame, buried or overt anger, emotional withdrawal, lingering trauma, isolation and defensiveness. At worst, this can immobilize you with depression and fear or cause you to lash out at your loved ones with the violent words or actions that have scarred your life. Or it can lead to a lifetime of dodging commitments because being close to another simply feels too dangerous. Or shame and an inability to forgive yourself for being a victim can impair your ability to reach out to others or to recognize and accept love from another.

Feeling limited by parental expectations or long ago social mores. The voices of our parents can linger and haunt us into our later years -- voices that tell us that we're not measuring up, not good enough, not pretty enough, not smart enough.

My mother found me disappointing in two ways: I wasn't pretty and I wasn't popular with boys in my teen years. She would study my face appraisingly. "You have a nicely shaped face," she would say. "But you need to get a nose job. You need to fix yourself up. Maybe someday you'll grow into a kind of attractiveness." But I could see the doubt in her eyes. She attributed my lack of social life to the fact that "you're socially awkward and you always say the wrong thing." The latter would make me wince, even then. I thought I was quite good at conversations and connecting. I had deep and lasting friendships. It was true that guys weren't asking me out. But they were confiding in me ("How do I get Patty to like me??"). They saw me as a buddy, just not as a potential date. Over time, I began to see that my fierce ambition -- which matched or exceeded theirs -- might have been a factor in my dearth of youthful romance. But the legacy of my mother's voice lingered for a long time in my angst and insecurity with romantic relationships.

The social mores of the time we came of age can also linger.

In some cultures and some families, daughters weren't valued as much as sons and/or sons were expected to measure up to often unattainable achievement or macho ideals.

A dear male friend of mine talks about the pain of growing up sensitive and artistic in a family of men who loved hunting and sports.

An older female cousin talks with a twinge of regret about measuring her worth by her attractiveness to men when she was young, never realizing or valuing the keen intelligence that became evident in later life when she excelled at college courses she took for fun after her children were grown.

A long-time gay male friend looks at younger gays and lesbians with wonder at the fact that so many come to terms with their sexuality at a very young age and are reaching adulthood at a time when marriage is an option. My friend didn't come out to himself until he was thirty, after a failed heterosexual marriage and numerous relationships with women, all with unhappy outcomes. He didn't come out in a larger sense until many years later. And while he found love and his life's companion while in his mid-thirties, they were together for 35 years before being able to marry. And he still struggles with discomfort at casual public affection, like holding hands, after so many years of secrecy and social disapproval.

How do we overcome or learn to live with these ghosts from the past?

Take responsibility for your life -- past and present. It can sound like a tall order when so much happened back then. It may be true that others caused you pain when you were too young or too powerless to defend yourself. It may be that criticism or neglect or abuse defined your relationship with a parent. But now that you're neither young nor powerless, you do have a choice. You can choose to simmer in that pain from the past, caught up in resentment, convinced that your life has been permanently damaged, even ruined, by what happened long ago. Or you can refuse to be a victim any longer and choose to live life on your own terms. Be aware of your feelings -- from long ago and today. When you allow your feelings to happen, rather than avoiding or repressing them, there can be pain and there can be growth. Long ago, you may have felt powerless and fearful. You may have despaired about life ever being different. It's important to cry those unshed tears, to comfort that child within you and to reassure the adult you are that you're no longer powerless or without options.Forgive what you can't forget. Forgiveness does not mean saying what happened then was okay or denying that a significant person hurt you. Forgiveness means letting go, freeing yourself from the bonds of resentment and a desire for vengeance, freeing yourself from a pattern of anger and blame. Forgiving another can mean letting go of the need to look back and revisit the anguish. It's also important to forgive yourself. Many people find themselves caught in a pattern of self-blame and recrimination for being a victim, for not being stronger or able to make a difference then. Forgive yourself for what you weren't able to do. Forgive yourself for poor choices or decisions that make you cringe as you look back. Tell yourself that you did the best you could at the time -- even if it was far from optimal. What really matters is what you choose to do now.Focus on what was positive then and now. Very few of us grew up in total misery. Life may have been challenging to be sure, but think of those times in between. You may have had one friend who understood. Or a teacher who cared. Or an activity or interest shared with an otherwise difficult parent or sibling. Or a family tradition that brought a smile to your face -- maybe once or maybe many times. Maybe the ghost that lingers is not from your childhood but from a relationship or marriage that went sour and that lingers painfully into your present as you find yourself reluctant to risk loving again. Thinking back to the good times instead of dwelling on what was painful and awful can help to balance your view of what was. It can also empower you to recognize and emphasize the positives in your life now, appreciating the present -- however imperfect or complicated. Embracing the positive in your life right now can free you from those ties to pain and powerlessness, free you to take the risk of making your life even better. Seek help in sorting through the past. This may mean seeking professional help with a psychotherapist to explore what happened then, how it all affected you and how to begin to make a difference in your own life. Or it may mean talking with a sibling or trusted long-time friend or other family member to sort out your memories and feelings, to find positives from the past, to share tears or laughter over old times and to express hope for the future.

My cousin Caron spent several summers with my family when we were young, before my father lost his job. She remembers only the charming side of my father, his humor and generosity. She recalls lively conversations, fun family walks in the evening and my father's enthusiastic encouragement of my early writing efforts. Her memories help to balance my own.

Talking with my brother Mike has helped me to see how beliefs carried from past to present can be irrational and yet enduring. We remember that our father predicted his downfall and our slide into poverty long before it became a reality. It was part of a life script that fit his self-image as a victim of circumstance rather than the master of his own life. His alcoholism and his fears of not measuring up -- fears fueled by his own irrational and critical mother who put him to work as family breadwinner when he was only nine years old -- led, at least in part, to his midlife unemployment and descent into madness. He always felt like a victim and his failures, in his eyes, were always someone else's fault. Mike and I grieve and laugh and comfort each other as we remember it all -- the creative and intellectual stimulation, the fun, the terrible fear that permeated our home from our earliest days, the abuse, the craziness and chaos. And we forgive our parents and ourselves, vowing to take total responsibility for our own lives -- for our failures as well as our successes.

Mike quietly vows that life will be quite different for his two young children. He wants to give them love, gentle guidance, and the inspiration to find joy in living. He wants them to grow up feeling both loved and empowered.

For me, a uniquely healing look back came from a conversation with Sister Ramona, my high school journalism teacher and a lifelong friend. Not long before her death two years ago, Ramona and I were having dinner together and discussing a troubled mutual friend who had been a high school classmate of mine. "Your home situation when you were growing up was so much worse than hers -- or so it always seemed to me," Ramona said. "But lately I've been thinking about it. Your parents had their issues -- okay, they were seriously dysfunctional at times -- but they cared. They were very engaged in your life. They showed up for every school play, for every parent-teacher conference. They were so proud of you. And they loved you so very much. What a difference that makes...."

Indeed. One may wish away those ghosts that linger, but that might take away too much else that made a wonderful difference in my life.

Not long ago, Mike asked if, were it in my power, would I choose to go back and grow up in a different family? I answered instantly and definitively "No!"

He smiled. "Neither would I," he said quietly.

Our ghosts are manageable, instructive, and an intrinsic part of the joyous, imperfect and loving individuals we've grown up to be.

"Baby," my father would say, handing me the Sunday L.A. Times classified ads. "Please look and see if there are any jobs. We all have to get jobs. I don't know where our next meal is coming from."

My stomach would tighten as I looked through the ads. There were no jobs listed for females -- the ads were segregated by gender then-- who were younger than 18. I wondered how far babysitting earnings could be stretched to feed a family of five. I loathed babysitting, but longed to make a difference. And I wondered if it could be true that we were in danger of quietly starving to death in a community of abundance.

My brother Mike, then nine years old, seemed to worry less because he saw more options. He quickly got a paper route -- available only to boys in those days -- and that kept expanding. He switched to a larger newspaper with an even bigger route. He earned enough to help out and to start his own savings account -- savings that have only grown over time -- through his years as a paperboy, an Air Force pilot and then as a physician and administrator at major medical centers in the U.S. and abroad. He paid his own way through medical school at Stanford. He owns several homes. He has been prudent and productive, amassing healthy savings. And yet....

"I've always worried about being destitute," Mike told me recently. "From our childhood on. Did it come from Father telling us at a tender age that we all needed to get jobs? My whole life I've never felt safe -- there's always the fear. Actually, it's worse than a fear. It feels more like a knowledge that it's all going to end up badly some day. That's what keeps me working all the time even now."

I nodded. The same ghosts of the past have haunted me. The old destitution terrors have heightened anew as our sister struggles through a dire financial situation, a crisis that seems to embody all of the fears we three have carried through the years.

And it leads me to a truth that is hard to face at times: we may rise above troubled pasts, but pieces of who we've been and what we experienced in times long past do linger into adulthood, into future relationships and on into older age.

It may mean: