Joanne Leedom-Ackerman's Blog, page 12

June 11, 2019

PEN Journey 4: Freedom on the Move West to East

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I’ve been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions. With memories stirring and file drawers bulging, I am a bit of a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down memories. I hope this personal PEN journey will be of interest.

I have attended 32 International PEN Congresses as president of a PEN Center, often as a delegate, as Chair of the International Writers in Prison Committee, as International Secretary and now as Vice President. The number surprises me when I count. The Congresses have been held on every continent except Antarctica. Many were grand affairs where heads of State such as Vaclav Havel in Czechoslovakia, Angela Merkel in Germany, Abdoulaye Wade in Senegal greeted PEN members. Some were modest as the improvised Congress in London in 2001 when PEN had to postpone the Congress planned in Macedonia because of war in the Balkans. PEN held its Congress in Ohrid, Macedonia the following year. At these Congresses writers from PEN centers all over the globe attended. Today PEN International has centers in over 100 countries.

Among the more memorable and grand was the 54th PEN Congress in Canada, held in September 1989 when PEN still held two Congresses a year. The Canadian Congress, staged in both Toronto and Montreal by the two Canadian PEN centers, moved delegates and participants between cities on a train. The theme—The Writer: Freedom and Power—signaled hope at a time when freedom was expanding in the world with writers wielding the megaphone.

The literary programs included luminary writers from over 25 countries, including Margaret Atwood (Canada), Chinua Achebe (Nigeria), Anita Desai (India), Tadeusz Konwicki ( Poland), Claribel Alegria (El Salvador), Margaret Drabble (England), Michael Ignatieff (Canada), Ama Ata Aidoo (Ghana), Derek Walcott (St. Lucia), John Ralston Saul (Canada), Duo Duo (China), Harold Pinter (England), Tatyana Tolstaya (USSR), Alice Munro (Canada), Wendy Law-Yone (Burma), Larry McMurtry (USA), Emily Nasrallah (Lebanon), Yehuda Amichai (Israel), Maxine Hong-Kingston (USA), Michael Ondaatje (Canada), Nancy Morejn (Cuba), Jelila Hafsia (Tunisia), Miriam Tlali (South /Africa), and dozens more, and other writers listed in absentia such as Vaclav Havel (Czechoslovakia) and writers from Iran, Turkey, Hungary, South Africa, Morocco and Vietnam. PEN members and delegates attended from at least 57 PEN centers around the world.

The new PEN International President Rene Tavernier, a poet who had been active in the French resistance during World War II, hailed the importance of the writer’s role in upholding freedom of expression around the globe and in confronting central power which restricted individual voices. PEN’s and the writer’s only weapon was the word, he said, and the word must be used in service of “creative intelligence, human rights, lucidity and hope.” Though the twentieth century had seen “the growth of new and atrocious ideologies with their police forces and concentration camps, they could not change the spirit of man, which is what PEN defends,” he said. PEN’s concern was literature and ideas and conversations among writers, who may not always agree.

A goal of the Congress was to expand dialogues among people, especially in Muslim communities in the wake of the fatwa and to expand PEN’s reach into Africa, the Middle East and Latin America. Today PEN centers in those areas have grown exponentially with 33 centers in Africa and the Middle East and 19 centers in Latin America, though participation from these centers in global forums still remains challenging.

Another outcome of the Congress was the formation of the PEN Women’s Network, a precursor to the Women’s Committee established as a standing committee of PEN two years later at the 1991 Vienna Congress. The Canadian Congress organizers had balanced literary panels and discussions among men and women, a response to the growing voice of women in PEN and to the 1986 New York Congress where men dominated the forums. Some opposed a Women’s Committee, including English PEN which voiced concern that it would fragment and divide members when the goal of PEN was to bring people together. English PEN already operated under a guideline that balanced men and women in leadership. PEN International Vice President Nadine Gordimer wrote that she had “more pressing obligations here, at home in South Africa, towards the needs of both women and men who are writers under our difficult and demanding position, beset by censorship, harassment, and lack of educational opportunities common to both sexes.” But she added that she hoped if a committee did form, it would be in touch with all South African writers.

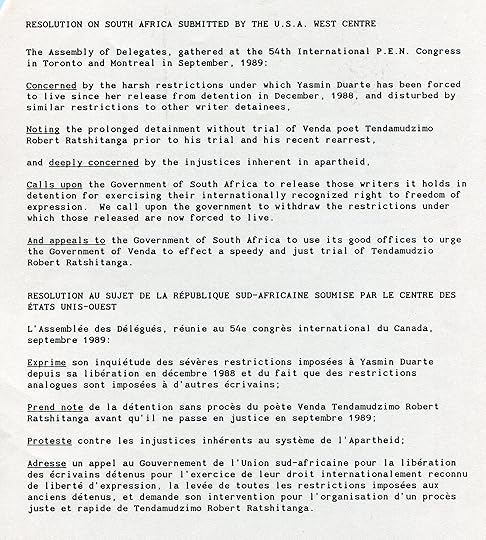

PEN USA West presented a resolution on South Africa at the Congress, protesting the arrest and treatment of a number of writers, including our honorary member. The resolution passed unanimously in the Assembly of Delegates.

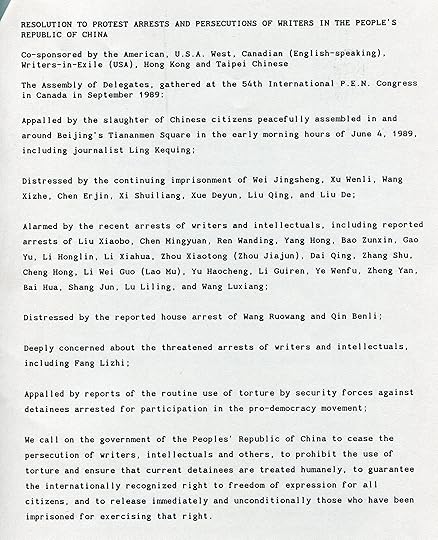

My fellow delegate and I also joined American PEN as well as Canadian PEN, Hong Kong and Taipei PEN in a resolution protesting the “slaughter of Chinese citizens peacefully assembled in and around Beijing’s Tiananmen Square” three months before and the arrest of writers, including Liu Xiaobo and over 20 others. It was feared some of the China PEN members might be under threat. Neither the China Center nor the Shanghai Center were present at the Canadian Congress, but they had been in touch with PEN International. In an official communication the Shanghai Center protested that China was being slandered abroad. Representatives from the two Chinese Centers had demanded an apology from PEN International because poet Bei Dao had been allowed to address the Maastricht Congress (see PEN Journey 3) and they continued to argue that PEN’s main case Wei Jingsheng was not a writer. An apology was not offered, and the resolution protesting the killings and arrests after Tiananmen Square passed with one abstention. Delegates from the China Center and Shanghai Center didn’t return to a PEN Congress for the next two decades, but in the intervening years, individual centers and members such as Japanese writers stayed in touch. In 2001 an Independent Chinese PEN Center (ICPC) formed and gave a place for Chinese writers inside and outside of China to communicate with discussion and debate on freedom of expression and democracy. PEN currently has more than half a dozen centers of Chinese writers, including the China, Shanghai, ICPC, Taipei, Hong Kong, Tibet, Uyghur, and Chinese Writers Abroad centers.

The challenge for PEN has been how best to use its formal resolutions, written in the language of the United Nations. These are passed then directed to the respective governments, to United Nations forums and to embassies and officials in the countries where PEN has centers. The effort begins at the PEN International office and then fans out through the centers. The impact of the resolutions vary according to country and to the direct advocacy efforts. The climate for such resolutions has changed over the years, and it is an ongoing question what is the most impactful method for effecting change.

At the Canadian Congress the situation in Myanmar/Burma was also highlighted. Our center, along with Austrian, Australian (Perth), and Canadian centers presented a resolution protesting the slaughter of Burmese citizens and the wholesale arrests and imprisonment without trial of citizens, including writers, after the imposition of martial law. I met one of these writers—Ma Thida—in London years later after PEN had advocated aggressively for her release. She’d spent almost six years in prison. A physician, writer and editor and an assistant for Aung San Suu Kyi, she remained committed to freedom for her country. It took another 15 years before the Myanmar government eased restrictions and a civilian government took over. When the political situation in Burma/Myanmar began to open, Ma Thida, Nay Phone Latt and other writers, many of whom had been in prison, formed a PEN Myanmar Center which joined PEN’s Assembly at the 2013 Congress in Reykjavik, Iceland. Ma Thida was its first president, and she now serves on the International Board of PEN.

Ma Thida and Joanne Leedom-Ackerman at the PEN Congress in Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan in October 2014

For me, the outward facing Canadian Congress mirrored my own preparation for moving with my family to London three months later in January 1990. It was a fortuitous time to live in Europe as Eastern Europe was opening to the West. Six weeks after the PEN Congress, East Germany announced that its citizens were free to cross into the West, and the Berlin Wall began to crumble figuratively and literally as citizens used hammers and picks to knock down the looming concrete structure. In fall 1990, I took my sons, ages 10 and 12, to East Berlin, and we too climbed up on ladders with metal rods and knocked down the wall, chunks of which we still have.

At the Canadian Congress, PEN International’s Writers in Prison Committee (WiPC) Chair Thomas von Vegesack asked that a sub-committee be formed to assist in fundraising. Eight centers—Australian (Perth), Canadian, Swedish, Norwegian, West German, English, American and USA West agreed to help. Because I was moving to London where PEN International was headquartered, Thomas asked if I would head the effort. I told him I wasn’t able to do so but agreed to take on the interim position and help him find a chair and then agreed to take on the task of getting PEN International charitable tax status. I assumed the latter mission would be fairly straightforward, a matter of finding the right law firm to assist. Little did I know the complications of British charitable tax law. Eventually Graeme Gibson, president of PEN Canada, novelist and partner of Margaret Atwood, agreed to head the development effort.

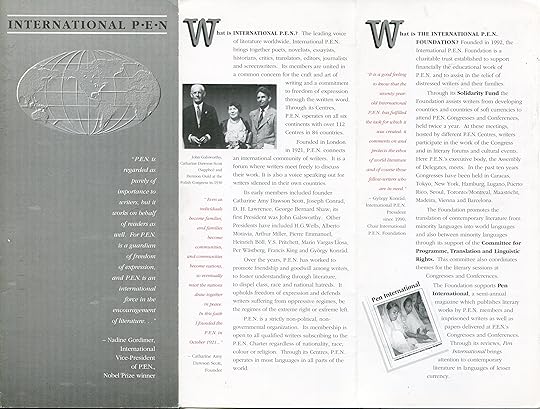

After I arrived in London, I found a law firm. Charitable tax status would relieve PEN of tax bills it found hard to pay and also help with fundraising, but so far PEN had not been able to secure the charitable status. Thomas and I, along with the International Secretary Alexander Blokh, Treasurer Bill Barazetti and Administrative Director Elizabeth Paterson met frequently at the PEN International offices at the top of four (or was it five?) very steep flights of stairs in the Charterhouse Buildings where we worked on what turned out to be a two-year project that included the establishment of the International PEN Foundation. The Foundation was allowed to raise tax-exempt funds for the “charitable” work of PEN which could not include perceived “political” work, but only the “educational” aspects.

It took a young American who didn’t know it was impossible to do what we have not been able to do, Antonia Fraser said to me as she joined the first board of the International PEN Foundation in 1992. In a way she was right for I had no idea the complexity of British tax law, quite different than America’s. I wasn’t prepared for the sets and sets of documents and negotiations, the time required to set up a separate organization; on the other hand, the effort opened up the workings of PEN International to me and introduced me to friends I’ve maintained over the decades who also worked on the project. On the Foundation board with me were a majority of British citizens (and PEN members), including Antonia Fraser, Margaret Drabble, Buchi Emecheta, Andre Schiffrin, Christopher Sinclair-Stevenson and later Ronald Harwood as well as a few other international members, PEN’s International Secretary, Treasurer and the new PEN President Gyorgy Konrad.

Harold Pinter’s play Moonlight premiered as the first fundraising event of the International PEN Foundation on October 12, 1993 at the Almeida Theater. Dramatically, the lights of the theater burnt out just before the performance, and the play had to be performed by candlelight.

First International PEN and PEN Foundation brochure.

Next Installment: PEN, Writers in Prison Committee and the Balkans Wars

The post PEN Journey 4: Freedom on the Move West to East appeared first on Joanne Leedom-Ackerman.

June 3, 2019

PEN Journey 3: Walls About to Fall

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I have been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions, including as Vice President, International Secretary and Chair of International PEN’S Writers in Prison Committee. With memories stirring and file drawers bulging, I am a bit of a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down memories. In digestible portions I will recount moments and hope this personal PEN journey may be of interest.

Our delegation of two from PEN USA West—myself and Digby Diehl, the former president of the Center and former book editor of the Los Angeles Times—arrived in Maastricht, The Netherlands in May 1989 for the 53rd PEN International Congress. We joined delegates from 52 other centers of PEN around the world, including PEN America with its new President, fellow Texan Larry McMurtry and Meredith Tax, founder of what would soon be PEN America’s Women’s Committee and later PEN International’s Women’s Committee. Meredith and I had met at the New York Congress in 1986 where the only picture of the Congress on the front page of The New York Times showed Meredith and me in the background at a table taking down the women’s statement in answer to Norman Mailer’s assertion that there were not more women on the panels because they wanted “writers and intellectuals.” Betty Friedan argued in the foreground.

Front page of the New York Times, 1986. Foreground: left – Karen Kennerly, Executive Director of American PEN Center, right – Betty Friedan, Background: (L to R) Starry Krueger, Joanne Leedom-Ackerman, Meredith Tax.

Over the previous months the two American centers of PEN had operated in concert, mounting protests against the fatwa on Salman Rushdie and bringing to this Congress joint resolutions supporting writers in Czechoslovakia and Vietnam.

The theme of the Maastricht Congress—The End of Ideologies—in large part focused on the stirrings in Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union as the region poised for change no one yet entirely understood. A few weeks earlier, the Hungarian government had ordered the electricity in the barbed-wire fence along the Hungary-Austrian border be turned off. A week before the Congress, border guards began removing sections of the barrier, allowing Hungarian citizens to travel more easily into Austria. In the next months Hungarian citizens would rush through this opening to the West.

At PEN’s Congress delegates from Austria and Hungary sat a few rows apart, separated only by the alphabet among delegates from nine other Eastern bloc countries which had PEN Centers, including East Germany. This was my third Congress, and I was quickly understanding that PEN mirrored global politics where writers were on the front lines of ideas and frequently the first attacked or restricted. Writers also articulated ideas that could bring societies together.

In those days PEN had close ties with UNESCO, and attending a PEN Congress was like visiting a mini U.N. Assembly. Delegates sat at tables with name tags of their countries in front of them. Action was taken by resolutions which were debated and discussed and then sent to the International Secretariat and back to the Centers for implementation. At the time PEN operated with three standing Committees, the largest of which was the Writers in Prison Committee focused on human rights and freedom of expression. The other two were the Translation and Linguistic Rights Committee and the Peace Committee. Soon, in 1991, a fourth—the Women’s Committee—would be added. At parallel and separate sessions to the business of the Assembly of Delegates, literary sessions explored the theme of the Congress.

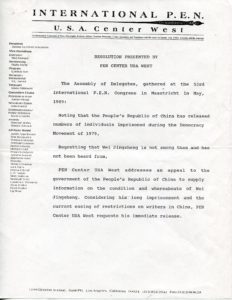

PEN USA West was particularly active in the Writers in Prison Committee (WiPC) where we advocated for our “adopted/honorary” members, most prominent for us at that moment was Wei Jingsheng in China. We had drafted and brought to the Congress a resolution, noting that China had recently released numbers of individuals imprisoned during the Democracy Movement, but Wei Jingsheng had not been among them and had not been heard from. We addressed an appeal to the People’s Republic of China to give information on the condition and whereabouts of Wei Jingsheng and to release him.

Before we spoke to this resolution on the floor of the Assembly, we met with the delegate of the China Center. The origins of this center was a bit of a mystery since it was one of the few centers that defended its government’s actions rather than PEN’s principles. I still recall the delegate with thick black hair, square face, stern visage and black horn-rimmed glasses, though this last detail may be an embellishment. He argued with me that Wei Jingsheng was an electrician, not a writer, that he had simply written graffiti on a wall, but that he had committed a crime by sharing “secrets” with western press.

The Chair of the Writers in Prison Committee Thomas von Vegesack, a Swedish publisher, arranged for the celebrated Chinese poet Bei Dao, a guest of the Congress, to speak in support of the PEN USA West resolution. The delegate from Taipei PEN stood next to Bei Dao and translated his words which contradicted the China delegate. Bei Dao noted that Wei Jingsheng had been in prison ten years already, having been arrested when he was 28-years-old. He had already published his autobiography and 20 articles and for years had been editor of the magazine SEARCH. In his posting on the Democracy Wall and in his essay “The Fifth Modernization,” Wei had suggested that democracy should be added as a fifth modernization to Deng Xiaoping’s four modernizations. “This shows that Wei Jingsheng’s status as a writer can’t be questioned,” Bei Dao said. I still remember that moment of Bei Dao addressing the Assembly and his country man with a Taiwanese writer translating. For me it demonstrated PEN in action.

In Beijing at that time thousands of students and citizens were protesting in Tiananmen Square.

PEN Center USA West’s resolution passed. The China Center and Shanghai Chinese Center refused to accept the resolution. The Maastricht Congress was the last PEN Congress they attended for over twenty years.

In the months preceding the gathering in Maastricht International PEN Secretary Alexander Blokh, International President Francis King and WiPC Chair Thomas von Vegesack had visited Moscow where the groundwork was laid to bring Russian writers into PEN with a Center independent of the Soviet Writers Union.

Twenty-two years before, Arthur Miller, International PEN President, had also traveled to Moscow at the invitation of Soviet writers who wanted to start a PEN center.

In 1967 Miller met with the head of the Writers’ Union and recounted in his autobiography:

At last Surkov said flatly, “Soviet writers want to join PEN….”

“I couldn’t be happier,” I said. “We would welcome you in PEN.”

“We have one problem,” Surkov said, “but it can be resolved easily.”

“What is the problem?”

“The PEN Constitution…”

The PEN Constitution and the PEN Charter obliged members to commit to the principles of freedom of expression and to oppose censorship at home and abroad. Miller concluded that the principles of PEN and those of the Soviet writers were too far apart. For the next twenty years PEN instead defended and assisted dissident Soviet writers.

At the Maastricht Congress Russian writers, including Andrei Bitov and Anatoly Rybakov attended as observers in order to propose a Russian PEN Center. Rybakov (author of Children of the Arbat) told the Assembly that writers had “endured half a century of non-democratic government and had lived in a dehumanized and single-minded state.” He said, “Literature could be influential in the fight against bureaucracy and the promotion of the understanding between nations and cultures. Now Russian writers want to join PEN, the principles and ideals of which they fully shared, and the responsibilities of belonging to which they recognized…and hoped for the sympathy of the members of PEN.”

The delegates unanimously elected Russian PEN to join the Assembly. In the 1990’s and until he passed away in 2007, one of the most outspoken advocates for free expression in Russia was poet and General Secretary of Russian PEN, Alexander Tkachenko. (Working with Sascha, as he was called, will be included in future blog posts.)

Polish PEN was also reinstated at the Maastricht Congress. After seven years of “severe restrictions and false accusations by the Government which had resulted in their becoming dormant,” the Polish delegate said they were finally able to resume normal activity in full harmony with PEN’s Charter. “I must stress here that our victory we owe in great part to the firm and unbending attitude of International P.E.N. and to almost unanimous solidarity of the delegates from countries all over the world.”

At the Congress PEN USA West, American PEN, Canadian PEN and Polish PEN presented a resolution on Czechoslovakia, calling for the government to cease the recent campaign against writers and to release Vaclav Havel and all writers imprisoned. The Assembly recommended that the International PEN President and International Secretary get permission from Czech authorities to visit Vaclav Havel in prison. Two weeks after the Congress Vaclav Havel was released. In December of 1989 Havel was elected President of Czechoslovakia after the collapse of the communist regime. In 1994, President Havel, along with other freed dissident writers, greeted PEN members at the 61st PEN Congress in Prague.

Also at the Maastricht Congress was an election for the new President of International PEN. Noted Nigerian writer Chinua Achebe stood as a candidate, supported by our two American Centers, Scandinavian centers, PEN Canada, English PEN and others, but Achebe was relatively new to PEN, and at the time there were only a limited number of African centers. Achebe lost by a few votes to the French writer Rene Tavernier, who passed away six months later.

Achebe admitted that he was not as familiar with PEN but said that if the organization had wanted him as President he had been persuaded that “it would be exciting.” He noted the world was very large and very complex. He hoped that in the years to come the voices of those other people would be heard more and more in PEN.

Our delegation had the pleasure of having dinner with Achebe in a castle in Maastricht which had a gourmet restaurant that served multiple courses with tiny portions. The small dinner, which also included the East German delegate and I think fellow Nigerian writer Buchi Emecheta and an American PEN member, lasted over three hours. I’m told when Achebe left, he asked his cab driver if he had any bread in his house because he was still hungry. When I saw Achebe a few times in the years following, he always remembered that dinner.

At the Maastricht Congress two new Africa Centers were elected: Nigeria, represented by Achebe, and Guinea. The election of these centers signaled a growing presence of PEN in Africa. Today PEN has 27 African centers.

A few weeks after we returned from the Congress to Los Angeles, tanks entered Tiananmen Square. Hundreds of citizens, including writers, were arrested and killed. One of my first thoughts was, what will happen to Bei Dao, but fortunately he hadn’t yet returned to China. Our small PEN office started receiving faxes from London with dozens of names in Chinese, and we and PEN Centers around the globe began writing and translating those names and mounting a global protest. Among those on the lists I am sure, though I didn’t know him at the time, was Liu Xiaobo, who was instrumental in helping protect the students and in clearing the square.

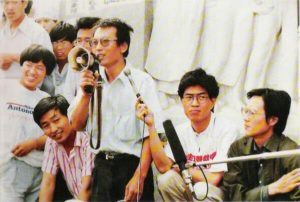

Tiananmen Square. June 4th, 1989. © 1989 Stuart Franklin/MAGNUM

Liu Xiaobo (with megaphone) at the 1989 protests on Tiananmen Square.

Twenty years later Liu Xiaobo would be a founding member and President of the Independent Chinese PEN Center. He would also later help draft and circulate the document Charter 08, patterned after the Czechoslovak writers’ document Charter 77, calling for democratic change in China. In 2009 Liu Xiaobo was again arrested and imprisoned. He won the Nobel Prize for Peace in 2010 and died in prison in 2017.

The opening of the world to democracy and freedom which we glimpsed and hoped for and which seemed imminent in 1989 appears less certain now.

Today, June 3-4, 2019 memorializes the thirtieth anniversary of the tanks rolling into Tiananmen Square. During the years after Tiananmen when Liu Xiaobo and others were in prison I chaired PEN International’s Writers in Prison Committee. But that is a story to come….

Next installment– PEN Journey 4: Freedom on the Move West to East

The post PEN Journey 3: Walls About to Fall appeared first on Joanne Leedom-Ackerman.

May 21, 2019

PEN Journey 2: The Fatwa

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I have been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions, including as Vice President, International Secretary and Chair of International PEN’S Writers in Prison Committee. With memories stirring and file drawers bulging with documents, I am a bit of a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down memories. In digestible portions I will recount moments, though I’m not certain I can contain all these, but I hope this personal PEN journey may be of some interest.]

It was President’s weekend in the US—between Lincoln and Washington’s birthday, coinciding with Valentine’s Day, 1989. I was President of PEN Center USA West and had just hired the Center’s first executive director ten days before. I’d been working hard with PEN and was also finishing a new novel, teaching and shepherding my 8 and 10-year old sons. For the first time in a year and a half my husband and I were going away for a long weekend without our children. He had also been working nonstop and had managed to clear his schedule.

On the plane to Colorado where we planned to ski, I read that Salman Rushdie’s The Satanic Verses had been burned in Birmingham, England. The next day Ayatollah Khomeini issued a fatwa against Rushdie. What was a fatwa? The Supreme Leader of Iran was calling for the murder of Rushdie wherever he was in the world, and he was offering a $6 million reward. As information about the fatwa developed, it also included a call for the death of whoever published The Satanic Verses.

I began making phone calls. This was a time before omnipresent cell phones so I had to find phones and numbers where people could reach me. (Usually our vacation dynamic was that my husband was on the phone.)

That first day I skied and wrote press releases on the ski lift and stopped at lodges on the mountain to use the pay phones to communicate with our new executive director. I’d ski another run then call the office again to answer questions from the press. What exactly was a fatwa, we were still asking? What did this mean for a writer? By the end of the day, I told my husband I had to return to LA.

“Can’t this wait?” he asked.

“No, it can’t,” I said.

Though a fatwa was a new concept, I understood, as did PEN members around the world, that a threshold had been crossed when a head of state issued a death warrant on a writer wherever he was in the world. Our two sons came out to be with my husband, and I returned to LA. Our board went into action as did PEN Centers around the globe to protest the fatwa. We organized a public event at the Los Angeles Times with writers and experts, an event which included readings from Rushdie’s book. Some were frightened by the threat, but most in PEN gathered. We contacted US government officials and began coordinating with global PEN centers, including American PEN in New York to confirm the support of writers for Rushdie and to protest Khomeini’s action.

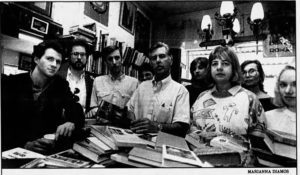

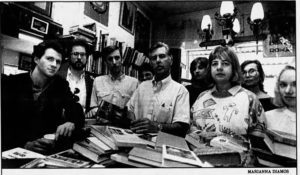

Davis Dutton, center, of Dutton’s Books with some of his employees who voted to ignore the threats from Iran and stock “The Satanic Verses.”

Whatever the controversy over The Satanic Verses and its “insult” to Muslims, PEN was clear that the right of the writer to write without fear of death was primary.

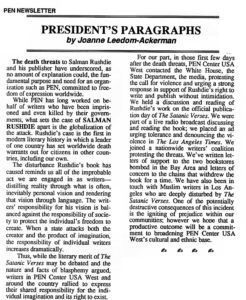

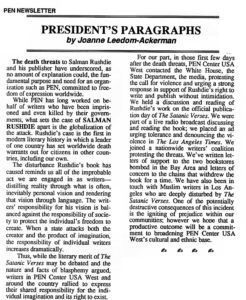

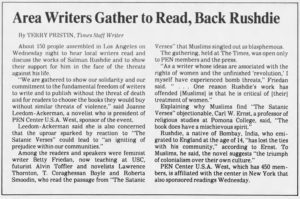

The mobilization included discussions with bookstores to encourage them to keep the book on the shelves for many were quietly removing it. The fuller scope of our PEN’s actions at the time is described in the column below in the PEN Center USA West’s newsletter and in a story in the Los Angeles Times.

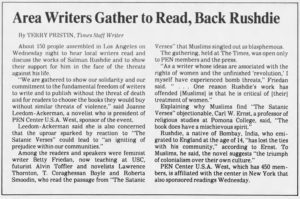

Los Angeles Times, February 23, 1989

Next installment: PEN 1989 at the junction as Eastern Europe opens, Soviet Union begins to crumble and Chinese students and citizens challenge the government in Tiananmen Square.

The post PEN Journey 2: The Fatwa appeared first on Joanne Leedom-Ackerman.

PEN Journey 2

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I have been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions, including as Vice President, International Secretary and Chair of International PEN’S Writers in Prison Committee. With memories stirring and file drawers bulging with documents, I am a bit of a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down memories. In digestible portions I will recount moments, though I’m not certain I can contain all these, but I hope this personal PEN journey may be of some interest.]

It was President’s weekend in the US—between Lincoln and Washington’s birthday, coinciding with Valentine’s Day, 1989. I was President of PEN Center USA West and had just hired the Center’s first executive director ten days before. I’d been working hard with PEN and was also finishing a new novel, teaching and shepherding my 8 and 10-year old sons. For the first time in a year and a half my husband and I were going away for a long weekend without our children. He had also been working nonstop and had managed to clear his schedule.

On the plane to Colorado where we planned to ski, I read that Salman Rushdie’s The Satanic Verses had been burned in Birmingham, England. The next day Ayatollah Khomeini issued a fatwa against Rushdie. What was a fatwa? The Supreme Leader of Iran was calling for the murder of Rushdie wherever he was in the world, and he was offering a $6 million reward. As information about the fatwa developed, it also included a call for the death of whoever published The Satanic Verses.

I began making phone calls. This was a time before omnipresent cell phones so I had to find phones and numbers where people could reach me. (Usually our vacation dynamic was that my husband was on the phone.)

That first day I skied and wrote press releases on the ski lift and stopped at lodges on the mountain to use the pay phones to communicate with our new executive director. I’d ski another run then call the office again to answer questions from the press. What exactly was a fatwa, we were still asking? What did this mean for a writer? By the end of the day, I told my husband I had to return to LA.

“Can’t this wait?” he asked.

“No, it can’t,” I said.

Though a fatwa was a new concept, I understood, as did PEN members around the world, that a threshold had been crossed when a head of state issued a death warrant on a writer wherever he was in the world. Our two sons came out to be with my husband, and I returned to LA. Our board went into action as did PEN Centers around the globe to protest the fatwa. We organized a public event at the Los Angeles Times with writers and experts, an event which included readings from Rushdie’s book. Some were frightened by the threat, but most in PEN gathered. We contacted US government officials and began coordinating with global PEN centers, including American PEN in New York to confirm the support of writers for Rushdie and to protest Khomeini’s action.

Davis Dutton, center, of Dutton’s Books with some of his employees who voted to ignore the threats from Iran and stock “The Satanic Verses.”

Whatever the controversy over The Satanic Verses and its “insult” to Muslims, PEN was clear that the right of the writer to write without fear of death was primary.

The mobilization included discussions with bookstores to encourage them to keep the book on the shelves for many were quietly removing it. The fuller scope of our PEN’s actions at the time is described in the column below in the PEN Center USA West’s newsletter and in a story in the Los Angeles Times.

Los Angeles Times, February 23, 1989

Next installment: PEN 1989 at the junction as Eastern Europe opens, Soviet Union begins to crumble and Chinese students and citizens challenge the government in Tiananmen Square.

The post PEN Journey 2 appeared first on Joanne Leedom-Ackerman.

May 15, 2019

PEN Journey 1: Engagement

[PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. As Vice President Emeritus of PEN International and former International Secretary, former Chair of PEN International’s Writers in Prison Committee, former President of PEN Center USA West, board member and Vice President of PEN America and the PEN/Faulkner Foundation, I have been active in PEN for more than 30 years. With memories stirring and file drawers bulging with documents, I am a bit of a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down some of the memories. I will try in digestible portions to recount moments, though I’m not certain how easily I can contain all these. I hope this personal PEN journey might be of some interest.]

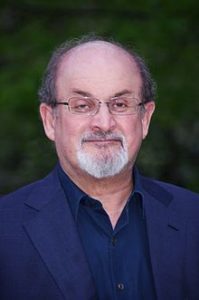

February 13, 1989: I was President of PEN Center USA West and on an airplane when I read that Salman Rushdie’s novel Satanic Verses was being burned in Birmingham. The next day a fatwa was issued on Rushdie. What was a fatwa, we all asked at the time, as we, along with PEN Centers around the world, mobilized to protest that a head of state was ordering the murder of a writer wherever he was in the world.

November 10, 1995: As Chair of PEN International’s Writers in Prison Committee, I was standing vigil with others outside the Nigerian Embassy in Washington, D.C. when word spread that novelist and activist Ken Saro Wiwa had been hanged that morning in Port Harcourt, Nigeria.

October 7, 2006: My phone rang at 7:30 on Saturday morning. I was International Secretary of PEN International, and the International Writers in Prison Program Director was calling to tell me that Anna Politkovskaya had just been shot and killed in Moscow. We all knew Anna—I’d last had coffee with her at an airport in Macedonia. We worked with her on the situation of writers in Russia and Chechnya and had enormous respect for her knowledge and courage.

January 19, 2007: We were about to begin a PEN International board meeting in Vienna when a call came from Istanbul. Hrant Dink had just been shot and killed outside his newspaper office in Istanbul. Dink was an editor of an Armenian paper and a writer whom members of PEN knew well and worked with on freedom of expression issues in Turkey.

Most writers long active in PEN’s freedom-to-write work can tell you where they were when the news broke on each of these cases. They can tell you because the lives of these writers and many others have been critical in the struggle for freedom of expression around the world.

In sharing memories of PEN, I begin with the writers and with the many friends around the globe who work on behalf of writers who don’t have the freedom to write without threat, imprisonment or death. As colleagues, we are bound together by the belief that truthful writing matters, be it journalism, fiction, poetry, drama, essays because stories and witnessing and creative imagination connect, inspire and shape us. Free expression is fundamental to a free society and is worth defending and expanding.

Salman Rushdie Ken Saro Wiwa Anna Politkovskaya Hrant Dink

My own thirty plus years working with PEN began at a dinner meeting in Los Angeles in the early 1980’s. I was a young writer, new mother, former journalist who’d recently moved across the country from New York City where I taught writing at university and had friends and colleagues. I landed in the land of sun and Hollywood, and though I had a new college teaching job, I knew few people and even fewer writers. Like many who first seek out PEN, I came for the community.

My second meeting was at someone’s home where a presentation was made about writers in different parts of the world who were in prison because of their writing. I was introduced to PEN’s Writers in Prison Committee. At that meeting, we wrote postcards urging the Chinese government to release Wei Jingsheng, a writer who was imprisoned for “counterrevolutionary” activities, particularly for his essay “The Fifth Modernization” which he’d posted on the Democracy Wall in Beijing in 1978. His manifesto argued that as China was modernizing with four principles of modernization, it needed to include a fifth modernization–Democracy.

As I learned about Wei Jingsheng and the other writers on whose behalf PEN worked, I became more active in the PEN Center on the West Coast of America called PEN Los Angeles Center. I was elected President in 1988. Shortly after the election, I attended my second PEN International Congress in Seoul, South Korea right before the Olympics there. (The first Congress I attended was in 1986 in New York City, where our Center’s members were registered with the foreign delegates. I was active at that New York Congress in the Women’s revolution and the statement that came from the Congress.)

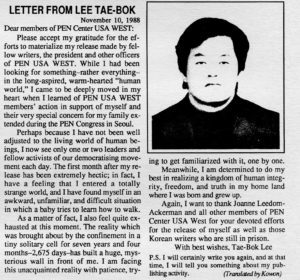

I arrived in Seoul late summer,1988 with our Center’s support for resolutions including one calling for the release of Wei Jingsheng and other writers in China, another resolution addressing writers in prison in South Korea, including our honorary member, publisher Lee Tae-Bok, and a resolution to change the name of PEN Los Angeles Center to PEN Center USA West. The name change had been passed by our center’s previous board but needed approval of the international Assembly of Delegates. It reflected our wider membership in the western part of the United States.

As president of PEN Los Angeles Center, I arrived as a young writer with a small delegation from Southern California, which included the former book editor of The Los Angeles Times and an English professor from UCLA. American PEN, based in New York, the largest of PEN’s more than 60 worldwide centers at the time was headed by Susan Sontag, president. American PEN didn’t want us to change our name and opposed our resolution on the floor of the Congress. While our two centers agreed on the other substantive issues of the Congress, including the problematic situation for writers in South Korea, and though we shared meals, the American PEN delegation, and Susan Sontag in particular, tried to get us to withdraw our name change, including a midnight call to me from Susan. The name change would be confusing, she said, and would take from the national scope of American PEN’s work. In that midnight call I listened to the arguments, then shared our thinking, which included the observation that our membership already came from many states west of the Mississippi, that in a country the size of the United States, PEN allowed more than one center, and for writers 3000 miles from New York, there was value in having more than one center of gravity. In the morning I presented American PEN’s arguments to my delegation, and we decided to go ahead and let our resolution go to the floor of the Assembly.

The representative from East Berlin noted: It would seem the East and West of America get along worse than the East and West of Germany. PEN Los Angeles Center’s resolution for a name change won by a wide margin, and we left the Congress as PEN Center USA West, which years later became PEN USA. I no longer live in Los Angeles but note that only in the past year –2018—did the members of the West Coast PEN decided to merge with PEN America in New York so there is now only one center of PEN in the US.

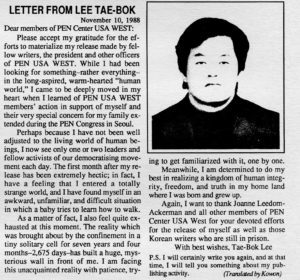

Most memorable and significant from the Seoul Congress was our delegation’s visit with the family of Lee Tae-Bok, our honorary member. “The house of Lee Tae-Bok’s parents is neat and spare, bedrooms with tatami mats on the floor, a living room with a sofa, a chair, a fish tank. There is no excess in the house, one senses out of choice. But there is an absence, not out of choice, for Lee Tae-Bok has been away in prison seven years. His mother worries that she will not see her oldest son out of prison before she dies,” I wrote in our Center’s newsletter. The family said that Lee Tae-Bok was in poor health and held in a cell four by five square meters, allowed out in the fresh air for only twenty minutes a day and wasn’t allowed to write except one letter a month to his family. His mother lamented the “hypocrisy” of the Korean government which had sentenced her son to life in prison because they said he published communist propaganda and yet they were greeting writers and “honored guests” at PEN’s Congress from Communist countries as well as inviting Eastern bloc athletes to Korea for the Olympic Games.

Digby Diehl and Joanne Leedom-Ackerman meet with the family of Lee Tae-Bok at the Lee home in Seoul in 1988.

In addition to our family visit, PEN Congress delegates petitioned the South Korean government on behalf of those in prison. A delegation from PEN International visited two of the writers in prison.

A few weeks after the Congress, notification reached us that Lee Tae-Bok had been released, though not everyone PEN spoke up for was released. I still remember where I was—I was in New York—when I heard the news, and I remember the elation. Many people worked on Lee Tae-Bok’s behalf so we couldn’t and didn’t take the credit, but we could feel some part of our actions, some push at the prison door helped spring it open. Release is not always the outcome for PEN’s work, but often it is. It is one of the goals. Over all my years in PEN, the release of a writer from prison still evokes a burst of hope and a measure of faith.

[Next installments: the watershed year 1988-1989 as the first global fatwa is issued against a writer, and writers and students in Tiananmen Square square off against China.]

The post PEN Journey 1: Engagement appeared first on Joanne Leedom-Ackerman.

PEN Journey 1

[PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. As Vice President Emeritus of PEN International and former International Secretary, former Chair of PEN International’s Writers in Prison Committee, former President of PEN Center USA West, board member and Vice President of PEN America and the PEN/Faulkner Foundation, I have been active in PEN for more than 30 years. With memories stirring and file drawers bulging with documents, I am a bit of a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down some of the memories. I will try in digestible portions to recount moments, though I’m not certain how easily I can contain all these. I hope this personal PEN journey might be of some interest.]

February 13, 1989: I was President of PEN Center USA West and on an airplane when I read that Salman Rushdie’s novel Satanic Verses was being burned in Birmingham. The next day a fatwa was issued on Rushdie. What was a fatwa, we all asked at the time, as we, along with PEN Centers around the world, mobilized to protest that a head of state was ordering the murder of a writer wherever he was in the world.

November 10, 1995: As Chair of PEN International’s Writers in Prison Committee, I was standing vigil with others outside the Nigerian Embassy in Washington, D.C. when word spread that novelist and activist Ken Saro Wiwa had been hanged that morning in Port Harcourt, Nigeria.

October 7, 2006: My phone rang at 7:30 on Saturday morning. I was International Secretary of PEN International, and the International Writers in Prison Program Director was calling to tell me that Anna Politkovskaya had just been shot and killed in Moscow. We all knew Anna—I’d last had coffee with her at an airport in Macedonia. We worked with her on the situation of writers in Russia and Chechnya and had enormous respect for her knowledge and courage.

January 19, 2007: We were about to begin a PEN International board meeting in Vienna when a call came from Istanbul. Hrant Dink had just been shot and killed outside his newspaper office in Istanbul. Dink was an editor of an Armenian paper and a writer whom members of PEN knew well and worked with on freedom of expression issues in Turkey.

Most writers long active in PEN’s freedom-to-write work can tell you where they were when the news broke on each of these cases. They can tell you because the lives of these writers and many others have been critical in the struggle for freedom of expression around the world.

In sharing memories of PEN, I begin with the writers and with the many friends around the globe who work on behalf of writers who don’t have the freedom to write without threat, imprisonment or death. As colleagues, we are bound together by the belief that truthful writing matters, be it journalism, fiction, poetry, drama, essays because stories and witnessing and creative imagination connect, inspire and shape us. Free expression is fundamental to a free society and is worth defending and expanding.

Salman Rushdie Ken Saro Wiwa Anna Politkovskaya Hrant Dink

My own thirty plus years working with PEN began at a dinner meeting in Los Angeles in the early 1980’s. I was a young writer, new mother, former journalist who’d recently moved across the country from New York City where I taught writing at university and had friends and colleagues. I landed in the land of sun and Hollywood, and though I had a new college teaching job, I knew few people and even fewer writers. Like many who first seek out PEN, I came for the community.

My second meeting was at someone’s home where a presentation was made about writers in different parts of the world who were in prison because of their writing. I was introduced to PEN’s Writers in Prison Committee. At that meeting, we wrote postcards urging the Chinese government to release Wei Jingsheng, a writer who was imprisoned for “counterrevolutionary” activities, particularly for his essay “The Fifth Modernization” which he’d posted on the Democracy Wall in Beijing in 1978. His manifesto argued that as China was modernizing with four principles of modernization, it needed to include a fifth modernization–Democracy.

As I learned about Wei Jingsheng and the other writers on whose behalf PEN worked, I became more active in the PEN Center on the West Coast of America called PEN Los Angeles Center. I was elected President in 1988. Shortly after the election, I attended my second PEN International Congress in Seoul, South Korea right before the Olympics there. (The first Congress I attended was in 1986 in New York City, where our Center’s members were registered with the foreign delegates. I was active at that New York Congress in the Women’s revolution and the statement that came from the Congress.)

I arrived in Seoul late summer,1988 with our Center’s support for resolutions including one calling for the release of Wei Jingsheng and other writers in China, another resolution addressing writers in prison in South Korea, including our honorary member, publisher Lee Tae-Bok, and a resolution to change the name of PEN Los Angeles Center to PEN Center USA West. The name change had been passed by our center’s previous board but needed approval of the international Assembly of Delegates. It reflected our wider membership in the western part of the United States.

As president of PEN Los Angeles Center, I arrived as a young writer with a small delegation from Southern California, which included the former book editor of The Los Angeles Times and an English professor from UCLA. American PEN, based in New York, the largest of PEN’s more than 80 worldwide centers at the time was headed by Susan Sontag, president. American PEN didn’t want us to change our name and opposed our resolution on the floor of the Congress. While our two centers agreed on the other substantive issues of the Congress, including the problematic situation for writers in South Korea, and though we shared meals, the American PEN delegation, and Susan Sontag in particular, tried to get us to withdraw our name change, including a midnight call to me from Susan. The name change would be confusing, she said, and would take from the national scope of American PEN’s work. In that midnight call I listened to the arguments, then shared our thinking, which included the observation that our membership already came from many states west of the Mississippi, that in a country the size of the United States, PEN allowed more than one center, and for writers 3000 miles from New York, there was value in having more than once center of gravity. In the morning I presented American PEN’s arguments to my delegation, and we decided to go ahead and let our resolution go to the floor of the Assembly.

The representative from East Berlin noted: It would seem the East and West of America get along worse than the East and West of Germany. PEN Los Angeles Center’s resolution for a name change won by a wide margin, and we left the Congress as PEN Center USA West, which years later became PEN USA. I no longer live in Los Angeles but note that only in the past year –2018—did the members of the West Coast PEN decided to merge with PEN America in New York so there is now only one center of PEN in the US.

Most memorable and significant from the Seoul Congress was our delegation’s visit with the family of Lee Tae-Bok, our honorary member. “The house of Lee Tae-Bok’s parents is neat and spare, bedrooms with tatami mats on the floor, a living room with a sofa, a chair, a fish tank. There is no excess in the house, one senses out of choice. But there is an absence, not out of choice, for Lee Tae-Bok has been away in prison seven years. His mother worries that she will not see her oldest son out of prison before she dies,” I wrote in our Center’s newsletter. The family said that Lee Tae-Bok was in poor health and held in a cell four by five square meters, allowed out in the fresh air for only twenty minutes a day and wasn’t allowed to write except one letter a month to his family. His mother lamented the “hypocrisy” of the Korean government which had sentenced her son to life in prison because they said he published communist propaganda and yet they were greeting writers and “honored guests” at PEN’s Congress from Communist countries as well as inviting Eastern bloc athletes to Korea for the Olympic Games.

Digby Diehl and Joanne Leedom-Ackerman meet with the family of Lee Tae-Bok at the Lee home in Seoul in 1988.

In addition to our family visit, PEN Congress delegates petitioned the South Korean government on behalf of those in prison. A delegation from PEN International visited two of the writers in prison.

A few weeks after the Congress, notification reached us that Lee Tae-Bok had been released, though not everyone PEN spoke up for was released. I still remember where I was—I was in New York—when I heard the news, and I remember the elation. Many people worked on Lee Tae-Bok’s behalf so we couldn’t and didn’t take the credit, but we could feel some part of our actions, some push at the prison door helped spring it open. Release is not always the outcome for PEN’s work, but often it is. It is one of the goals. Over all my years in PEN, the release of a writer from prison still evokes a burst of hope and a measure of faith.

[Next installments: the watershed year 1988-1989 as the first global fatwa is issued against a writer, and writers and students in Tiananmen Square square off against China.]

The post PEN Journey 1 appeared first on Joanne Leedom-Ackerman.

April 25, 2019

Duck for a Day

I passed two ducks strolling down the highway on Easter morning—large mallards waddling and chatting with each other, staying on their side of the white-lined shoulder, yet precariously close to the cars whizzing by. They appeared oblivious to the traffic. I wondered where they were going and where they thought they were. They were several miles from water. On their side of the small highway on the Eastern shore of Maryland sprawled a shopping center with a supermarket, restaurants, movie theater. On the other side spread a bit of green field and beyond that more stores and beyond that woods, and beyond that the water—the Tred Avon River which eventually flows out into the Chesapeake Bay.

I was tempted to turn around and try to get a picture, but by the time I could make the turn and get back, they would likely have flown away. Instead, I carry their picture in my mind. I love ducks.

What kind of creature would you be if you were a creature? I would be a duck. Not a lion or giraffe or bear, not a gazelle or panther. No, I’d choose a duck. They can walk and swim and fly and are good at all three mobilities. They are modest, but much smarter and more ingenious than given credit. They have “a remarkable ability for abstract thought,” and “outperform supposedly ‘smarter’ animal species,” according to the Smithsonian. I am fairly certain walking down the highway, they were not debating the Mueller Report or the 2020 U.S. presidential elections, thus demonstrating already a more transcendent point of view.

I’d choose a mallard with the purple-blue wing feathers, the striking green set of feathers around the head (though that is only the male), stepping gingerly with big webbed feet, then gliding onto the water and when the mood strikes, lifting off the water into flight. I could live practically anywhere I wanted in North America, South America, Africa, Australia, Asia. I don’t have enemies except for humans who want to shoot me, and I have a pleasant disposition most of the time. I watch and listen, cooperate well with a group and have an uncanny sense of direction.

Readers, thank you for indulging this moment of fantasy in an effort to lift above the serious, yet endless and tendentious issues on the ground here in Washington.

What kind of creature would you be, at least for a day?

The post Duck for a Day appeared first on Joanne Leedom-Ackerman.

March 20, 2019

Arc of History Bending Toward Justice?

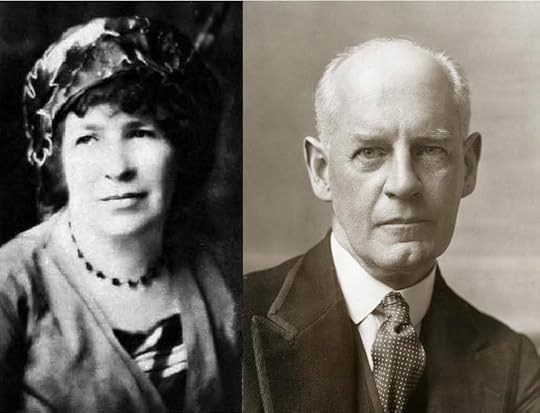

PEN International was started modestly almost 100 years ago in 1921 by English writer Catherine Amy Dawson Scott, who, along with fellow writer John Galsworthy and others conceived that if writers from different countries could meet and be welcomed by each other when traveling, a community of fellowship could develop. The time was after World War I. The ability of writers from different countries, languages and cultures to get to know each other had value and might even help reduce tensions and misperceptions, at least among writers of Europe. Not everyone had grand ambitions for the PEN Club, but writers recognized that ideas fueled wars but also were tools for peace.

Catherine Amy Dawson Scott and John Galsworthy

The idea of PEN spread quickly, and clubs developed in France and throughout Europe, the following year in America, and then in Asia, Africa and South America. John Galsworthy, the popular British novelist, became the first President. Members of PEN began gathering at least once a year in a general meeting. A Charter developed to focus the ideas that bound everyone. In the 1930s with the rise of Hitler, PEN defended the freedom of expression for writers, particularly Jewish writers. In 1961 PEN formed its Writers in Prison Committee to work systematically on individual cases of writers threatened around the world. PEN’s work preceded Amnesty, and the founders of Amnesty came to PEN to learn how it did its work. PEN’s Charter, which developed over a decade, was one of the documents referred to when the Universal Declaration of Human Rights was drafted at the United Nations after World War II.

Today there are over 150 PEN Centers around the world in over 110 countries. At PEN writers gather, share literature, discuss and debate ideas within countries and among countries and defend writers around the globe imprisoned, threatened or killed for their writing. The development of a PEN center has often been a precursor to the opening up of a country to more democratic practices and freedoms as was the case in Russia, other countries in the former Soviet Union and in Myanmar. A PEN center is also a refuge for writers in certain countries.

Unfortunately, the movement towards more democratic forms of government and freedom of expression has been in retreat in the last few years in a number of these same regions, including in Russia and Turkey.

As part of PEN’s Centennial celebrations, Centers and leadership at PEN International have been asked to share archives for a website that will launch in 2021. As I dug through my sizeable files of PEN papers, I came across this speech below which represents for me the aspirations of PEN, the programming it can do and the disappointments it sometimes faces.

At a 2005 conference in Diyarbakir, Turkey, the ancient city in the contentious southwest region, PEN International, Kurdish and Turkish PEN hosted members from around the world. The gathering was the first time Kurdish and Turkish PEN members shared a stage and translated for each other. I had just taken on the position of International Secretary of PEN and joined others at a time of hope that the reduction of violence and tension in Turkey would open a pathway to a more unified society, a direction that unfortunately has reversed.

This talk also references the historic struggle in my own country, the United States, a struggle which is stirring anew. “The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice,” Martin Luther King and others have been quoted as saying. This is the arc PEN has leaned towards in its first century and is counting on in its second.

PEN DIYARBAKIR CONFERENCE

March 2005

When I was younger, I held slabs of ice together with my bare feet as Eliza leapt to freedom in Harriet Beecher Stowe’s UNCLE TOM’S CABIN.

I went underground for a time and lived in a room with a thousand light bulbs, along with Ralph Ellison’s INVISIBLE MAN.

These novels and others sparked my imagination and created for me a bridge to another world and culture. Growing up in the American South in the 1950’s, I lived in my earliest years in a society where races were separated by law. Even after those laws were overturned, custom held, at least for a time, though change eventually did come.

Literature leapt the barriers, however. While society had set up walls, literature built bridges and opened gates. The books beckoned: “Come, sit a while, listen to this story…can you believe…?” And off the imagination went, identifying with the characters, whatever their race, religion, family, or language.

When I was older, I read Yasar Kemal for the first time. I had visited Turkey once, had read history and newspapers and political commentary, but nothing prepared me for the Turkey I got to know by taking the journey into the cotton fields of the Chukurova plain, along with Long Ali, Old Halil, Memidik and the others, worrying about Long Ali’s indefatigable mother, about Memidik’s struggle against the brutal Muhtar Sefer, and longing with the villagers for the return of Tashbash, the saint.

It has been said that the novel is the most democratic of literary forms because everyone has a voice. I’m not sure where poetry stands in this analysis, but the poet, the dramatist, the artistic writer of every sort must yield in the creative process to the imagination, which, at its best, transcends and at the same time reflects individual experience.

In Diyarbakir/Amed this week we have come together to celebrate cultural diversity and to explore the translation of literature from one language to another, especially to and from smaller languages. The seminars will focus on cultural diversity and dialogue, cultural diversity and peace, and language, and translation and the future. This progression implies that as one communicates and shares and translates, understanding may result, peace may become more likely and the future more secure.

Writing itself is often an act of faith and of hope in the future, certainly for writers who have chosen to be members of PEN. PEN members are as diverse as the globe, connected to each other through 141 centers in 99 countries. They share a goal reflected in PEN’s charter which affirms that its members use their influence in favor of understanding and mutual respect between nations, that they work to dispel race, class and national hatreds and champion one world living in peace.

We are here today as a result of the work of PEN’s Kurdish and Turkish centers, along with the municipality of Diyarbakir/Amed. This meeting is itself a testament to progress in the region and to the realization of a dream set out three years ago.

I’d like to end with the story of a child born last week. Just before his birth his mother was researching this area. She is first generation Korean who came to the United States when she was four; his father’s family arrived from Germany generations ago. I received the following message from his father: “The Kurd project was a good one! Baby seemed very interested and has decided to make his entrance. Needless to say, Baby’s interest in the Kurds has stopped [my wife’s] progress on research.”

This child will grow up speaking English and probably Korean and will also have a connection to Diyarbakir/Amed because of the stories that will be told about his birth. We all live with the stories told to us by our parents of our beginnings, of what our parents were doing when we decided to enter the world. For this young man, his mother was reading about Diyarbakir/Amed. Who knows, someday this child who already embodies several cultures and histories, may come and see this ancient city for himself, where his mother’s imagination had taken her the day he was born.

It is said Diyarbakir/Amed is a melting pot because of all the peoples who have come through in its long history. I come from a country also known as a melting pot. Being a melting pot has its challenges, but I would argue that the diversity is its major strength. In the days ahead I hope we scale walls, open gates and build bridges of imagination together. –Joanne Leedom-Ackerman, International Secretary, PEN International

The post Arc of History Bending Toward Justice? appeared first on Joanne Leedom-Ackerman.

February 25, 2019

One More Voice

I thought about ending this blog. The final post: December, 2018—just over ten years, over 100 posts. Informal reflections on a decade. Since February, 2008 when I first attempted this new form and posted, the volume of blogs around the globe has proliferated to an immeasurable dimension. Today with blogs, podcasts, Facebook posts, LinkedIn, Twitter, photos on Instagram and other platforms and apps I don’t even know or use, everyone is talking about everything. My email box is filled with messages and information and notifications I never asked for, with political points of view I can barely consider, polls and surveys I never fill out…except one where I answer NO whenever it appears: “Should Hillary Clinton run for President?” NO. This answer doesn’t represent a political point of view so much as a measuring of time and tides…and consequences. It is time for others.

And yet rather than ending this blog, I write again. Perhaps a politician can’t help running for office.

What is one more blog post launched into the universe? The freedom to express is one I don’t take for granted when that freedom is shrinking around the globe and can have dire consequences in countries like China, Russia, Saudi Arabia, Turkey, Mexico, Venezuela. What is one more blog post launched into the universe? Just that, one more voice, a point of view no else exactly has.

Some writers I know have turned to photography. I understand the turn. Below are photos from a few days south, away from snow and ice storms, a brief visit to sun and the promise of spring. Comment, post yourself, confirm someone is receiving. Happy winter’s end or summer’s end, depending in which hemisphere you live.

The post One More Voice appeared first on Joanne Leedom-Ackerman.

December 23, 2018

Pause…Watch…Listen…See…Hear

As we slide into the holidays and sweep towards the new year, events are in a swirl and spiraling mostly downwards it would appear, at least in Washington, DC, where I live.

Photo Credit: Julia Malone

Stop! A voice insists in my head.

Pause. Watch. Listen.

Turn off the car radio, the tv news, the commentators, the politicians at least for a moment.

Go to the park. Or to the country. Allow space to receive other thoughts.

Hear the wind rustling through a green bush at the edge of the parking lot.

See the wind knocking off the last leaves of a tree.

Watch the flag, still at half mast, saluting the wind.

Remember the three-year-old on stage last night at the community theater, trying to keep up and match steps with the older children.

Enjoy the three dogs—black, blonde and brown retrievers—running across the open field.

Hear the carols: “Sleigh bells ringing…Lovely weather for a sleigh ride together with you…”

No sleighs in Washington, but the carols ring out, and traditions wrap around in old words and sentiments even as new words—”border wall, shutdown, impeachment, resignation, fraud, lies”—fill the public discourse.

Time to get out of town?

Or just time to pause, watch, listen and try to see and hear other harmonies.

Giddy up! Giddy up! Let’s go. Looking for the Wonderland of Snow!

Happy holidays to All!

The post Pause…Watch…Listen…See…Hear appeared first on Joanne Leedom-Ackerman.