Edward Ashton's Blog, page 5

September 25, 2017

The End of Ordinary: A Novel: Edward Ashton: 9780062690326: Amazon.com: Books

If you really wanted to read my new book but thought $3.99 was a bit pricey, here’s your opportunity.

September 19, 2017

Liana’s a good noodle. Give this a peek if you have a chance.

Liana’s a good noodle. Give this a peek if you have a chance.

September 1, 2017

FFP 0226 - Ten Steps to a Successful Apocalypse

So I’ve got a (very) short piece up on the Manawaker Studios podcast this morning. Give it a listen if you have four minutes to kill.

August 30, 2017

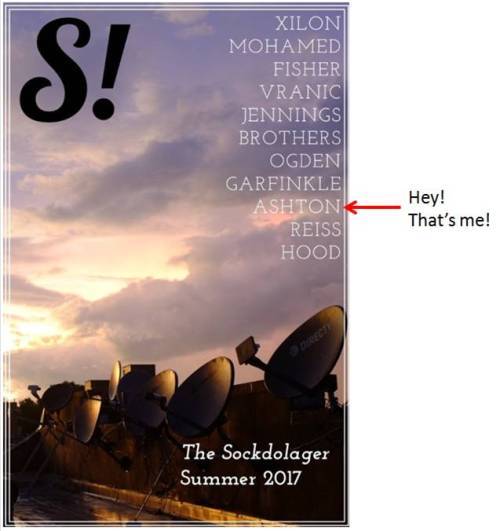

In the Land of Gods and Monsters

I’ve got a new piece out in the Summer 2017 issue of The Sockdolager. Give it a peek if you have a chance.

August 29, 2017

August 25, 2017

EP590: Four Seasons in the Forest of Your Mind : Escape Pod

This is a good one. Starts a little slow, but Caroline Yoachim, as usual, brings it home. Give it a listen if you have a chance.

August 16, 2017

The alt-right wants a “white ethno-state.” Elon Musk wants a Mars colony. Anybody else seeing a...

The alt-right wants a “white ethno-state.” Elon Musk wants a Mars colony. Anybody else seeing a chance for a win-win here?

August 6, 2017

We’ve Got Issues: Humanity’s Drive Toward Reinvention

For as long as humans have been writing things down, we seem to have been plagued by a persistent sense that something about us isn’t quite right. As an example, consider this, from Book XII of The Iliad:

“Hector laid hold of a stone that lay just outside the gates and was thick at one end but pointed at the other; two of the best men in a town, as men now are, could hardly raise it from the ground and put it on to a wagon, but Hector lifted it quite easily by himself,”

In Homer’s telling, and that of many of his contemporaries as well, the men of the past were giants, stronger and wiser and better in every way than those of today. We are a fallen, bedraggled species, sorely in need of aid from the gods if we’re to accomplish anything.

You see some of the same attitudes today, in both pop culture and science fiction. Check your Facebook feed, or the ads that show up on late night TV, and you’ll see an endless stream of ways to improve your skin, your libido, or your memory. Or, for a more entertaining take, check out my books (or those of folks like Greg Bear and David Brin) for some ideas about how genetic manipulation and mechanical augmentation might make us better in the future than we are today.

All of this raises an interesting question: why do we feel this need to fix ourselves? I find it hard to believe that dolphins spend a lot of their time ruminating about how their flukes could be improved, and chimpanzees and bonobos certainly seem to be pretty pleased with themselves. As a species, we’ve managed to overrun every corner of this planet, to an extent never before seen. Why the persistent inferiority complex?

For one possible answer to this question, we need to go back a ways—about ten thousand years, to be precise. This is the point where humanity first made what can be seen, from a certain perspective, as a very serious mistake: we invented agriculture.

“Wait,” I can almost hear you saying. “Isn’t agriculture a good thing? Isn’t that the reason there are so many of us around these days?”

Well, yes. That’s true. In the absence of agriculture, the total carrying capacity of this planet for an omnivorous apex predator like ourselves is probably no more than a hundred million or so, even if we managed to cover all six habitable continents as we have today. However, what is good for the species is not necessarily good for the individuals of that species.

Jared Diamond makes this case in great detail here (http://www.ditext.com/diamond/mistake.html), but the gist is this: our hunter-gatherer ancestors moved around all day, and ate a wide variety of foods, including many different fruits and vegetables, lots of meat, and little to no grain. Their farming descendants, in contrast, ate limited diets, heavy on starches and low on protein, were subject to frequent famines, performed a great deal of stoop labor, and lived in close contact with livestock, which spawned frequent species-hopping plagues. Early farmers were eight to ten inches shorter on average than their forebears, and lived significantly shorter and more unpleasant lives. Modern medicine and sanitation have given us longer lifespans than our ancient ancestors had, and at least in the developed world, comparable body size—but only in the past hundred years. That’s an awfully long time to recover from one bad left turn.

This line of argument raises another interesting question, of course: if hunter-gatherers were so much bigger, stronger and healthier than early agriculturalists, how did the farmers wind up winning out? There are two fairly unpleasant answers here. First, an agricultural lifestyle permits the subjugation of women, and their conversion from the relatively equal status they enjoy with men in most modern hunter-gatherer societies to the role of perpetually pregnant field-hand factories. Second, in conflicts over land and resources, a hundred starving farmers will defeat a dozen healthy hunters every time.

The upshot of all this is that our drive toward self-improvement may actually have a rational basis. On some deep level, we all may carry around a vague suspicion that at some point, something important was stolen from us. Is it so strange to think that we might want it back?

August 3, 2017

Ten Classic Sci-Fi Novels You Should Definitely Read

10. The Sirens of Titan, by Kurt Vonnegut

Is Vonnegut really a science fiction writer? I do not care. This book has a guy named Malachi Constant, a really stupid interplanetary war, a faithful dog, an infundibulum, and an alien who looks like a toilet plunger. What more could you possibly ask?

9. Spaceling, by Doris Piserchia

This is more YA than adult sci-fi, but it’s the book that first pulled me into the genre, so it makes the list. Spaceling provides exactly the mix of funny and heart-wrenching that I try to achieve in my own work. I read it for the first time when I was twelve, and it’s stuck with me ever since.

8. Shakespeare’s Planet, by Clifford D. Simak

This book has a lot of plot points that you could pick apart if you had the inclination, but it also has a sort of eerie wistfulness to it that I find irresistible. The heroes, if you can call them that, are a tentacled, fanged monster named Carnivore and a bumbling, block-headed robot. It also, like many of the books on this list, has the great virtue of being short enough to read in one long afternoon.

7. Dying of the Light, by George R. R. Martin

Long before he got into writing the interminable Song of Fire and Ice, Mr. Martin put out a series of short novels and long stories set in a future universe on the far side of a devastating interstellar war between humanity and a mostly unseen alien race. This book is the best of the bunch.

6. Up the Walls of the World, by James Tiptree Junior

Tiptree, whose real name was Alice B. Sheldon, was an acknowledged master of the genre, and this is one of her finest books. Up the Walls of the World addresses gender roles, the ethics of self-preservation vs. avoiding harm to others, and female genital mutilation, all while telling a gut-clinchingly heartbreaking story.

5. The Forge of God, by Greg Bear

I’m throwing this one on the list because (1) it’s a truly great book; (2) I’m extremely partial to end-of-the-world scenarios; and (3) most importantly, one of the final scenes is set at Taft Point in Yosemite National Park, which is one of the most beautiful places on Earth. That scene was most likely the subconscious genesis of my Hikepocalypse series of short stories, which continues to spawn new entries to this day.

4. City, by Clifford D. Simak

Hate to double up on Simak, but this is another of those books that grabbed me when I was very young and never really let go. It includes talking dogs, which is good, the extinction of humanity, which is okay, and some really obviously stupid Lysenkoism, which is bad. Mix them all together, though, and you wind up with something very special.

3. The Uplift War, by David Brin

This is the third book in Brin’s Uplift series (the first two being Sundiver and Startide Rising) but the way these books are written, you really don’t need to read them in order if you don’t care to. The Uplift War includes some fantastic galaxy-spanning world building, talking chimps and dolphins, a hopeless battle against insurmountable odds, and super scary praying mantis dudes. What’s not to like?

2. Cat’s Cradle, by Kurt Vonnegut

I don’t hate doubling up on Vonnegut at all, because he’s without question my all-time favorite writer. Cat’s Cradle is an incredibly dark but also hilarious examination of free will, religion, and man’s inevitable urge to self-destruction. It also contains one of the most haunting sentences I’ve ever read: “She laughed, and touched her finger to her lips, and died.” Can’t beat that.

1. Definitely not Foundation, Dune, Starship Troopers, or The Man who Fell to Earth

I read all of those books at one time, and ugh, I hated them all. Classics? Meh.

I guess I have to pick an actual number one, though, huh? Okay. Let’s go with… A Deepness in the Sky, by Vernor Vinge. Possibly not old enough to be a classic, but it’s got spaceships, some interesting stellar physics, and a whole planet full of extremely sympathetic giant spiders. Tough to pull that one off. Well done, Mr. Vinge.

July 31, 2017

Using Science in Science Fiction: How Not to Annoy Your Readers, in Three Simple Steps

There was a time, believe it or not, when many of the folks who wrote science fiction were, you know, scientists. Guys like Isaac Asimov, David Brin, and Robert L. Forward didn’t need to worry about getting things ridiculously wrong when they were writing about space travel or alien biology or robotics. They knew their stuff, and if they didn’t, they knew other people who did. If you have a Ph.D. in astrophysics, you probably do too.

What if you don’t, though? What if you’re an MFA grad, or a philosophy major, or just somebody lacking a crazy beard and tweedy jacket? Do you need to forever forego writing stories about alien invasions, post-human cyborg family life, and genetically modified apes? Absolutely not! Everyone deserves to write at least one genetically modified cyborg ape invasion book! It’s good to remember, though, that many of the folks who like to read those types of stories are scientists, or are at least very science savvy—and if you get something glaringly wrong in your writing, your readers are unlikely to be merciful.

With that in mind, here a few simple guidelines for using science in science fiction, no Ph.D. required.

1. If you’re using known technology, do a tiny bit of research and get it right.

A while back, I read a story in one of my favorite semi-pro zines. It was a good story. The characters were fleshed-out, well-rounded people. The plot was fun. The writing was solid. But…

A big chunk of the plot of this story involved things in orbit, and it was clear after two sentences that the author had no idea whatsoever how orbiting something works. To be clear—all I know about how orbiting something works is what I’ve picked up from the zeitgeist over the years. Still, I knew enough to know that the things the author was describing were so far from right that it almost seemed deliberate. I scrolled down to the comments section, and sure enough, nobody was talking about the fun plot or the awesome characters. They were talking about the fact that five minutes of googling could have saved the author from embarrassing himself.

The key point here is that we don’t need to earn a doctorate in astrophysics these days to find out that you don’t strap a big rock to your spaceship in order to give it more thrust. The internet is a wonderful thing. Use it.

2. If you’re writing hard sci-fi, you still need to make it believable.

You’re not writing a journal paper, right? This is fiction. It’s totally okay to make stuff up. However (and this is important) the stuff you make up has to, on some level, make sense. Want to send your characters to Alpha Centauri using an antimatter rocket? You should probably know that those things have a theoretical top speed of about 0.3c, which means that your trip is going to take a minimum of twelve or thirteen years. Want to genetically engineer your post-humans so that they live by photosynthesis and never have to eat? Please be aware that the energy density of sunlight at sea level is about 1.4 kW/m2, your body has a total surface area of less than 2 square meters, the conversion efficiency of photosynthesis is about 5%, and you need about 8.4MJ of energy per day to live. That means that if your photosynthesizing post-human spends twelve hours a day naked and spread-eagled in the desert, she can absorb enough energy to replace one pop tart, give or take. Apparently, there’s a reason that plants don’t move around much.

3. It’s okay to use imaginary future tech, but please keep it internally consistent.

Plenty of classic science fiction uses tech that isn’t just unknown—it’s almost certainly never going to be known. Warp drives and transporter rays and mental telepathy and whatnot are tons of fun, and I’ve read and enjoyed a million books that feature them. The keys to making these things believable are simple. There have to be rules. You have to know what they are. You have to follow them to a T. This is true even if you’re writing about straight-up magic—and yeah, I’m looking at you right now, Mr. Paolini.

The bottom line to all of this is pretty straightforward. Science fiction is all about imagination—but it’s better if your imagination is grounded in some level of truth. Make friends with the googles. Your readers will appreciate it.