Will Buckingham's Blog, page 12

May 19, 2015

The Descent of the Lyre: Free on Kindle!

“Gripping and highly original” — Louis de Bernières

“Masterful storytelling” — Historical Novel Review

“Unique, timeless and enjoyable” — Left Lion Magazine

“A highly memorable tale, told simply” — Vulpes Libris

“Really thrilling” — Radio Bulgaria

“Lyrical and well-written” — The Bookseller

See the link here: http://www.amazon.com/Descent-Lyre-Wi...

The Descent of the Lyre – Free Kindle Edition

I’m very pleased to announce that—to celebrate the recent launch of the paperback edition—the ebook of my novel The Descent of the Lyre is available between Monday and Friday this week as an entirely free download from Amazon. The Descent of the Lyre is a story of music and myth, violence and religion, set between Bulgaria and Paris in the 19th century. The novel was selected as a Bookseller Recommended read when it appeared in hardback. Click the button below to order a copy:

And here are a few reviews:

“Gripping and highly original” — Louis de Bernières

“Masterful storytelling” — Historical Novel Review

“Unique, timeless and enjoyable” — Left Lion Magazine

“A highly memorable tale, told simply” — Vulpes Libris

“Really thrilling” — Radio Bulgaria

“Lyrical and well-written” — The Bookseller

May 13, 2015

Creative Writing in Sofia

A very quick post this, from Sofia University. It’s my first time back in Bulgaria since the launch of the Bulgarian edition of The Descent of the Lyre in 2014 (incidentally, the original language version is now available in very handsome paperback — and if you haven’t bought the book yet, then get yourself a copy!). It is also my first time at the university since a philosophy conference I attended way back in 2006. It’s good to be here again.

I’m here thanks to the Erasmus programme, making connections with colleagues in the English and American Studies department, talking about possibilities for working together, and teaching a few classes. As a part of all this, I’ll be giving a public lecture tomorrow evening on the subject of creative writing (see the link here). I’m particularly pleased to be doing this lecture, as for I long time I’ve wanted the opportunity to step back and think about creative writing as an academic discipline. Being under pressure to say something relatively coherent in public about this has given me the excuse to put some thoughts into order. After all, despite seven or so years teaching creative writing in universities (and many more years elsewhere), I still find it a strange and puzzling business.

What I’m hoping to do in my lecture is to indulge in a bit of utopian thinking, imagining what the discipline could be, why it might be something worth doing, and generally rethinking things a bit. One of my main contentions is going to be that the hitching of creative writing to the discipline of English literature—which is common to must universities in the English speaking world—limits the subject’s scope both in terms of how we think about the pedagogy of creative writing, and how we think about the intellectual content of the discipline. Another of my contentions is going to be that fine artists have more fun.

Anyway, I’ll see how it goes. It’s going to be a fairly substantial talk, as the Bulgarians have much more stamina than my fellow countrymen (most public lectures are ninety minutes, I have been told, but as a foreigner-of-little-stamina I can get away with sixty). And I’m looking forward to seeing what discussions the lecture prompts.

April 24, 2015

More on those four great mysteries…

When I was in Suzhou a few weeks ago, I gave a talk about my Sixty-Four Chance Pieces at the wonderful Bookworm bookshop, called ‘Four Great Mysteries’ (see the blog post here). In preparation for the talk, I scrawled the following notes, and although the talk itself diverged occasionally wildly from what I’ve written here (the wine helped, as did the fun of working with two exceptional interpreters), I thought that I’d share the text for anyone who might be interested.

~O~

Introduction

I’m delighted to be here in Suzhou to talk about my new book, Sixty-Four Chance Pieces, a novel of sorts based upon the Yijing, or the Chinese Book of Changes. And I’m very grateful to the Bookworm for generously hosting this event. What a beautiful place Suzhou is, and what a lovely place the Bookworm here in Suzhou is! It’s really a pleasure to be here.

I’m here because, several years ago, I decided to write a kind of novel based upon the Yijing. Now, if there is anything that almost everybody knows about the Yijing, it is that it is a very mysterious book. So what I’m going to talk about today are what I am going to call Four Great Mysteries related to the Yijing, and to my own book that is based upon the Yijing, Sixty-Four Chance Pieces. So I’ll talk a little bit about these Four Great Mysteries, and then I’ll read a story from the book, to give you a flavour of the what I’m doing. Then we can open the floor up to questions.

So what are these Four Great Mysteries that I want to talk about? Let me put them down as briefly as I can.

Mystery number one: What the hell is the Yijing?

Mystery number two: What the hell does the Yijing mean? What is it for? What is its purpose?

Mystery number three: How the hell did a foolish and ignorant laowai like me come to get involved in all this stuff?

Mystery number four: What the hell is Sixty-Four Chance Pieces, this book I ended up writing as a result? Is it travel-writing? Is it fiction? Is it non-fiction? Is it philosophy? Is it an unholy mess? Or is it all of these, or none of these?

~O~

Mystery Number One: What the hell is the Yijing?

Several years ago, I watched a TV show in which a reporter went down to Wangfujing in Beijing and asked people what they knew about the Yijing. The reporter interviewed a lot of people, and the answer from all of them seemed to be the same. What they knew was, firstly, that Yijing was a very deep, very profound and very meaningful book. And secondly, they knew that they had know idea what this very deep, very profound and very meaningful book actually meant.

The Yijing has a reputation as a very difficult book, even though one way of translating the name of the book might be “The Easy Classic”. It is a bit puzzle, a mystery, or a conundrum.

Nevertheless, there are a few things that we can say about it for certain.

Firstly, the oldest part of the book, the Zhouyi, has its roots in traditions of divination that go back as far as the Shang dynasty. Scholars in the 20th and 21st centuries have done a lot of work in attempting to reconstruct the origins of the text. And these early origins seem to really not be particularly philosophical. Instead, they seem to be more rooted in Bronze Age traditions of divination that are concerned with things like warfare, dealing with one’s enemies, and so on. There is something curiously philosophical about the structure of the text in the earliest stages, but to the extent that there is philosophy here, it is different from the kind of philosophy that came on the scene later.

Secondly, the Zhouyi is supplemented by a series of commentaries called the ‘ten wings’, commentaries that put a philosophical gloss upon the text, and which set the scene for it becoming considered a philosophical classic.

Thirdly, the book as a whole, now known as the Yijing, became woven into a subtle philosophical framework, a vast system of correlations, that was in place by the Han dynasty, and which involves the ‘five phases’ or wuxing, the eight trigrams or bagua, yin and yang, the mystical diagrams known as the luoshu or Luo River Book, and the hetu, or River Map, and so on.

But fourthly, the Yijing became known in the West, thanks at first to the Jesuit missionaries, and the philosopher Leibniz. Over the past couple of hundred years, the Yijing has had its own complex history in the West, and it has influenced huge numbers of people from Carl Jung to Bob Dylan to John Cage.

~O~

Mystery Number Two: What the hell does the Yijing mean?

Mystery number two, however, is a bit more complicated. We can trace the historical origins of the Yijing, but it is much harder to say what it means. And this is partly because it is such a long history. At first I set out aiming to understand the Yijing. But as time went on, I realised that this was going to be impossible. This was not just because it was so very deep and so very profound, but also because I began to wonder if the idea of understanding the Yijing was itself based upon a misunderstanding of the Yijing. Of course, it is perfectly possible to understand a good deal about the Yijing. You can understand its origins, its influence, its precursors and the role of divination in the Shang dynasty, or the place that it has had in the work of contemporary musicians in the West. But understanding the Yijing itself is a rather different matter.

In fact, the more I looked at the Yijing, the more I began to realise that there’s a long tradition in China that calls into question this very idea of understanding the Yijing. A couple of examples here will suffice. The first is Yang Wanli 楊萬里, the 12th century philosopher, who in his commentary on the Yijing said that the purpose of the text was not to provide certainty, but greater doubt. The second is his contemporary, the neo-Confucian philosopher Zhu Xi 朱熹, who said that it is because the Yijing has no principle or meaning of its own that it can give rise to all possible principles or meanings. Moving from the Confucians to the Daoists, sometimes I like to think that the Yijing is like the empty space at the centre of the wheel that Laozi tells us is necessary for the wheel to turn at all. Perhaps, in other words, it means nothing. And perhaps it is because of this that it has become so very useful to so many people through the centuries.

As I have made my way through multiple attempts to understand the Yijing, and through multiple misunderstandings, I have taken comfort from the fact that most people in China claim to not understand the book. So after a few years of struggling to understand the Yijing itself, I set out instead to do two things: firstly to understand as much as I could about the text; and secondly to misunderstand the text in interesting ways, even if the ways that I was misunderstanding it or failing to understand it were not the ways that a Chinese reader would misunderstand it or fail to understand it.

~O~

Mystery Number Three: What the hell is an ignorant laowai like me doing getting involved in all this stuff anyway?

The third mystery is that of what I was doing getting mixed up in all of this business. After all, when I started out, I knew nothing about the Yijing. Absolutely nothing at all. Not only this, but I knew next to nothing about China. And I knew no Chinese. My ignorance was astounding. So why the Yijing? What was I thinking? What was I up to?

My first answer to this question is that my original intention was not really to explore the Yijing, but instead to try out an experiment when it came to writing. I was fed up with traditional novels. And my favourite novel of all time—Italo Calvino’s book Invisible Cities—was as far from a traditional novel as it was possible to get. What I wanted to do in my writing was to play with ideas and with thoughts. I wanted to muck around on the boundaries of fact and fiction, to see how randomness and chance could play a part in writing, to conduct a multitude of little experiments in writing differently. And I thought that the Yijing might be a good laboratory for carrying these experiments. So that is all I was interested in at the very start. But as time went on, I realised that I was getting sucked in, that I wasn’t fully in control of the direction of this series of little experiments. I realised that that in playing with the Yijing, the Yijing was playing with me.

What I mean by this is that the Yijing started to have an influence on me. It started to change me. It started to influence how I thought about things. It opened doors to new ways of thinking. And the more I became sucked in to this strange world, the more I realised that I could not let this be just some little, controlled experiment. I needed to let the project take me over. It was two years into the project before I realised that I should really start learning Chinese. It was another year before I enrolled in a Chinese language class. Time passed, and I became drawn in more and more deeply. I started to read about Chinese philosophy, history and literature. I continued to study. In 2010, I made my first ever official trip to China (I’d actually, technically, been to China twenty years before, for about ten minutes, but that is another story…). And now I find myself here, fully immersed in all this stuff, in a way that I had never expected or anticipated. It is strange how these things happens.

Of course, I’m still both foolish and ignorant. But now I’m foolish and ignorant and up to my neck in all this stuff. And I’m grateful for it.

~O~

Mystery Number Four: What the hell is this book, this Sixty-Four Chance Pieces that I’ve written?

I call this a mystery not because I want to convince you that the book I’ve written is somehow dark and mysterious. I call it a mystery because I genuinely don’t know what this book is. My publisher said to me, when he agreed to publish this book, ‘I’m willing to go ahead and publish it on one condition.’ I asked him what this condition was. He said that he would publish it if I understood that it was all my fault, if I accepted that he wouldn’t take any blame for the book.

Why did he say this? Partly because this is a book that doesn’t really fit any category. I call it a ‘novel of sorts’, because I like to hope that it has some novelty in it. But I don’t really know. Some of the book is travel writing. Some of it is philosophy. Some of it consists of jokes (and some of the jokes are about philosophy). Some of it is made of short stories. Some of it is additional apparatus—appendices, footnotes, an index, and other things that have no place in a novel.

This is not to say the book is just a free-for all. There is several organising principles at work. Each chapter has a clear structure: it begins with the image of one hexagram from the Yijing, and a brief introduction. This is followed by a story related in some way or other to this hexagram. At the end of each chapter, there are notes that expand upon the text in all kinds of ways. And this basic pattern is one which reflects that of the Yijing. But when I step back and look at the whole, I’m not quite sure what this book is. ‘It is what it is,’ my publisher said. Then he confessed, more or less, ’but it’s anybody’s guess what that is…’

Now I’ve got to the end, I realise that I didn’t exactly plan to write the book in this way. But it is not surprising that this is how it has taken shape. After all, the Yijing is a strange hybrid of a book. It was certainly not my job to try and tidy up the Yijing and impose some kind of order onto it, or to give a nice, neat interpretation. Instead, I saw it as my job to trace the Yijing‘s many complexities, and to write something that felt like it reflected or echoed these complexities. When you are writing a book about a strange book, and when you are trying to remain faithful to that book’s strangeness, then you are going to find that the strangeness seeps through a bit.

~O~

Easy and difficult books

If all this sounds daunting, I should end by saying that I don’t think that my Sixty-Four Chance Pieces is a difficult book. It may be strange, misshapen, odd or unusual. But it is not difficult. Somebody in Beijing said to me “I thought it might be like reading Ulysses, but it’s actually a really easy read”. I certainly hope so. After all, the “Yi” of Yi-jing, the scholars say, has three meanings. Firstly, it can mean “changing'”. So I wanted this to be a book of many changes. Secondly, it can mean “unchanging”. So I wanted the book to have a sense of something constant running through it. And finally, it can mean “easy” (remember that the Yijing is “The Easy Classic”). So, finally, I wanted to write a book that might provide pleasure, enjoyment, ease, richness and a dose of good fun.

If my Sixty-Four Chance Pieces have done this, even if I’m not sure what kind of a book this is, I will feel content with how the project, after all these years, has turned out.

Find out More

Sixty-Four Chance Pieces is now available in Kindle format:

For news on the paperback, go here.

April 20, 2015

Five Chance Questions About the I Ching

Now that my I Ching-based book, Sixty-Four Chance Pieces is out (see the page here for how to get hold of a copy), I thought I’d post this quick interview that I did recently about the book. So here are five chance questions about my sixty-four chance pieces about the I Ching.

Why did you write Sixty-Four Chance Pieces?

It started out as a whim. I wanted to write sixty-four intriguing stories, using the I Ching simply as a means to this end. But then the I Ching got the better of me. If you mess with a book that has survived for three thousand years, it is going to get the better of you. So I found myself getting sucked in. The project was supposed to take a couple of years. But in the end—what with learning Chinese, doing the research and all that—it took almost a decade.

What has an old Chinese book got to do with global 21st century people?

Old books are not to be underestimated. The I Ching has had a huge influence on China and, increasingly, on the rest of the world. Whilst writing this book, I was surprised by how many people confessed to me that they used the I Ching in their daily life. One student I met in Suzhou asked me whether it could be trusted when it came to fashion advice. I’m still not sure about this. I am not the person to ask about fashion advice.

Do you believe in fate? Do you think the I Ching reflects some higher power?

I don’t believe in fate. The world seems to me to be too messy and chaotic for things to be preordained. So one of the reasons that I like the I Ching is that it encourages me to think about change, uncertainty and mess. One of the biggest problems, perhaps, is that we suffer from too much certainty. The I Ching sows confusion in a very useful fashion. As for other powers, whilst I don’t think that the I Ching reflects a higher power, I think that it is a curiously cunning book. You have to be cunning (or else very stubborn) to survive that long.

How do the stories link to the I Ching?

Sometimes the links are very direct, sometimes they are more oblique and obscure. I wanted all the stories to be linked organically to the hexagrams of the I Ching, rather than being imposed upon them. Some stories came quickly, some I had to wait for a year, two years, or five years before they started to work.

What do I get as a reader from reading this?

Because I’m interested in uncertainty, I hope that readers will get things out of the book that I hadn’t even anticipated. When I was writing the book, I wanted it to be entertaining and intriguing. I take the I Ching seriously, but I don’t think seriousness is opposed to lightness and playfulness. So I didn’t want to write a heavy book. One of my early readers said to me that they were afraid that the book would be like Ulysses, but when she read it, she found herself laughing out loud. This was encouraging.

April 12, 2015

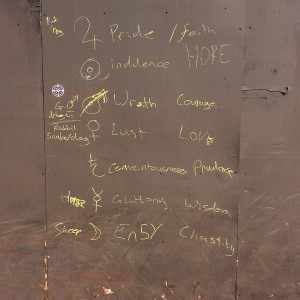

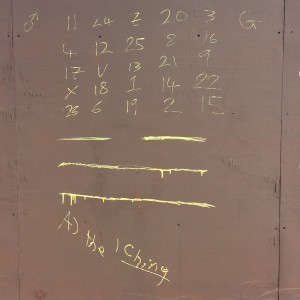

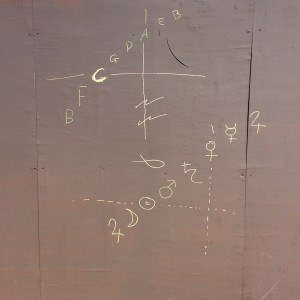

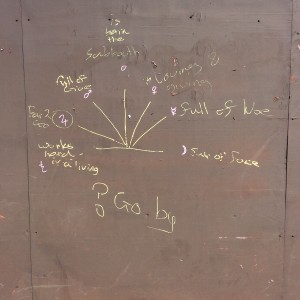

Graffiti and Numerology in Leicester

The I Ching, it seems, gets everywhere. This morning, as I was walking into town here in Leicester, I spotted some strange symbols painted onto a building-site hoarding outside Tesco, just by the park. The first thing that caught my eye was an image of the trigram dui (兌) ☱, or ‘lake’.

In case of any ambiguity, next door was written the word ‘lake’, as follows…

Then there was some strange correlation going on with the notes of the musical scale, as in the following diagram (reading the bottom B as a B♭), correlated with astrological symbols…

The astrological symbols reappeared, correlated in their turn with a popular rhyme about days of the week…

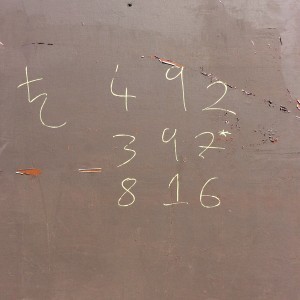

And there’s more. A couple of panels contained magic squares, like this 3×3 square (the figure that looks like a 9 at the centre should be a 5, and then it works perfectly, and is in fact equivalent to the Luoshu 洛書 of I Ching numerology — and is associated in Western numerology with Saturn).

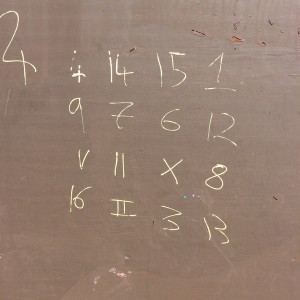

There was also a 4×4 magic square (read the letters as roman numerals), associated with Jupiter…

There were several more panels, one relating all of this to the seven deadly sins and the cardinal and theological virtues of the Middle Ages, further correlated with the animals of the Chinese zodiac.

And then there were several other astrological diagrams (I don’t think that the word in the background reading ‘popsox’—which may refer to comedian Bill Bailey’s spoof Swiss Europop band—has anything to do with this).

Anyway, just as I was wondering what all of this meant, I looked at the end hoarding, which provided the following answer…

It is hard to tell what all of this numerological speculation is doing. On a building-site hoarding. In Leicester. Outside Tesco. I felt a bit as if I was in the opening pages of a novel by Russell Hoban or Umberto Eco. But whatever it all means, it was intriguing to see.

March 23, 2015

Four Great Mysteries

Before coming to China, a lot of friends said, “I look forward to reading your blog posts.” But as it has been so very busy here — fourteen events in as many days — I have simply not had time to write very much. Anyway, I’m now in Suzhou for part three of my mini book tour, and it’s a lovely city to spend time in. The air quality feels better here, and you can actually see the sky.

Tonight I’m doing a talk at the Bookworm. The talk is going to be called “Four Great Mysteries.” The mysteries are these:

What is the I Ching?

What does the I Ching mean? What is it for?

How does a foolish and ignorant laowai end up getting mixed up in all this stuff?

What kind of a freakish book is this Sixty-Four Chance Pieces anyway? Fiction? Non-fiction? Philosophy? Travel-writing? An unholy mess? None of the above? All of the above?

I’m going to be making notes on all of these deep mysteries on the train to Shanghai this morning. In Shanghai I’m having a swift lunch with my publisher before I head back here (sorry, Shanghai friends — I’ll have to catch up wtih you another time…) for tonight’s event. Come along if you are in Suzhou.

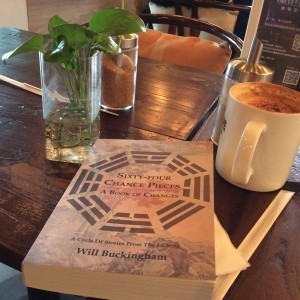

March 18, 2015

Making Books, Making Ourselves

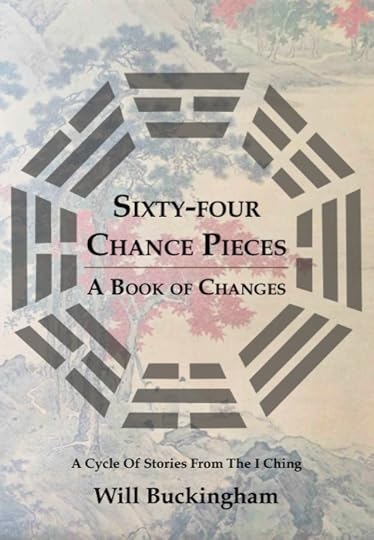

A couple of days ago I arrived in Beijing, and I hit the ground running, with two events yesterday — a school visit and a novel-writing workshop – and three events today. So there’s not much time in between the blog. But I thought I’d post this picture of my new book, Sixty-Four Chance Pieces: it’s hugely exciting to see get my hands on a real, physical copy.

The book is so hot off the press that I haven’t got my author copies yet. This one is borrowed from the people at the Beijing Bookworm Literature Festival, where I’m launching the book later this evening (the launch is just next door at iQiYi cafe, where I’m writing this). So it’s not yet generally available, although if you are in Beijing, come to the Bookworm and buy yourself a copy. For the rest of the world, it may be a couple of weeks before it filters through to distributors.

Writing books is strange. Before I started on this project, I hadn’t planned to get involved in all of this thinking about China and Chinese thought. I had never been to China. I didn’t speak a word of Chinese. But as readers and writers, the books we get involved with shape us. And for me, it has never been more true than in the case of this particular book. We make things. And in making things, these things in turn make and remake us.

Anyway, come along to the launch tonight if you are in Beijing. And if not, I’ll post again on this blog when the book is available on general release.

March 9, 2015

Sixty-Four Chance Pieces: the China Book Tour

I’m currently busy with packing my bags for China, and heading back to Beijing after an unforgivably long period (almost five years!), to take part in the Bookworm Literary Festival / 老书虫文学节 (see http://bookwormfestival.com). I’ve got a pretty busy schedule: something like fourteen events in as many days, in Beijing, Chengdu, Suzhou and Ningbo. It’s taken some organisational ingenuity to get there, but now everything is fixed, and I’m looking forward to being back in China again.

In particular, I’m immensely excited to be launching my novel-of-sorts, Sixty-Four Chance Pieces, published by Earnshaw Books, in Beijing on the 18th March at iQiyi cafe. This has been a project that is a long time in the making, and I’m not only delighted it has found a home with the excellent Earnshaw books, but also tremendously excited that it’s first launch will be over in Beijing.

There’s a full list of events on my events page, or on the Bookworm’s website (other than the Ningbo events, which are being hosted by the University of Nottingham in Ningbo), so if you are in town, then please do come along and say hello.

I’ll update this blog as I go along, to let you know how I get on with the tour. But between now and then, there’s a lot of last-minute organising to be done (not to mention our closer-to-home States of Independence festival for small and independent press publishing).

February 26, 2015

Sixty-Four Chance Pieces… coming soon

Another sneak preview of my book Sixty-Four Chance Pieces, this time of the rather lovely cover… I’ll give a shout when the book is available on general release.

Will Buckingham's Blog

- Will Buckingham's profile

- 181 followers