Patrick O'Duffy's Blog, page 25

March 12, 2012

A Q-and-A with Louise Cusack

In another lifetime, and another city, I used to be a shelf-monkey at Borders. (I think the technical term was 'store associate', but 'shelf-monkey' is more accurate.) Given different duties over time as more staff quit and the store's resources were stretched thinner and thinner, I started off by being in charge (ie the cleaner and sorter) of both the fantasy and romance sections, which were right next to each other. That made me realise that there were a lot of books on one set of shelves that could just as comfortably sit on the other (and vice versa), and a lot of overlap between the readers of those two genres.

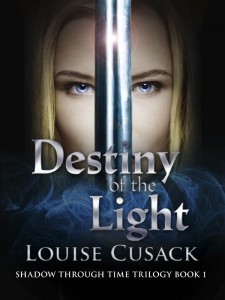

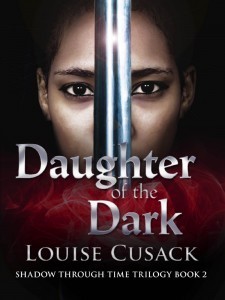

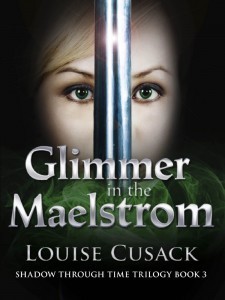

One of the writers working in that overlap is Louise Cusack, author of the 'romantic fantasy' trilogy The Shadow Through Time. Louise jumped into the Australian fantasy scene in the early 2000s, at a time when the genre was getting a lot more attention in this country than usual (a high we've fallen back from, unfortunately), with novels of intrigue, erotica and fantasy adventure that spanned generations and worlds.

One of the writers working in that overlap is Louise Cusack, author of the 'romantic fantasy' trilogy The Shadow Through Time. Louise jumped into the Australian fantasy scene in the early 2000s, at a time when the genre was getting a lot more attention in this country than usual (a high we've fallen back from, unfortunately), with novels of intrigue, erotica and fantasy adventure that spanned generations and worlds.

Recently the Shadow Through Time trilogy has been rereleased by Macmillan, this time as ebooks on their Momentum imprint, giving Louise a chance to reach an entirely new market outside Australia. That seemed like a good opportunity to ask her some questions about ebooks, fantastic romance and John Carter of Mars.

I always like to start with the big one. Why writing? Why do this rather than some other creative outlet, or indeed some kind of regular job that pays better?

I remember being in primary school and telling other kids that one day they'd see a book with my name on the cover. I was always good at English, but high school and dating distracted me. It was only after I was married and my first child was born that I remembered the writing. I took a couple of TAFE courses and entered short story competitions but I always knew I'd be a novelist. I don't think I really considered the idea that I might never succeed. I was convinced that I just had to persist, and after eight years of full-time writing I finally got a three book publishing deal with Simon & Schuster Australia.

I never really wanted to do anything else. I'm not crafty or domestic. It's all about story for me – books and movies. I can't bear lifestyle shows because they don't have a beginning, a middle and an end. I think I was just born with some storytelling gene, and I was lucky enough to have been in a situation where I could give it room to flourish. I don't ever want another career. For better or for worse I've defined myself as a novelist. I think there are worse things to be!

What exactly is 'romantic fantasy'? How is that different from, well, non-romantic fantasy?

'Romantic fantasy' is written mostly by women for women. It's a fantasy that has a strong love story as one of its plot threads. There's less focus on the 'boy's own adventure' aspects of fantasy like interminable questing and battles for the sake of bloodshed. But the adventure aspects are still important. It's a delicate balance, but there's definitely more focus on characterisation than straight fantasy novels.

It's almost like the difference between erotica and pornography. There's a greater focus on the sensuality, the senses, and how the action makes the characters feel emotionally as well as physically.

What is it that attracts you to romantic fantasy? Is it the same thing that attracts you to regular fantasy?

What is it that attracts you to romantic fantasy? Is it the same thing that attracts you to regular fantasy?

I love a good love story, no matter the genre, and most of the great books do have some form of love story in them. But my career focus as a writer is the 'stranger in a strange land' theme. It most readily lends itself to fantasy – someone going from our world into a fantasy world, like John Carter to Barsoom or Jake Sully to Pandora in the movie Avatar. I grew up reading sci fi, mostly the classics (in fact my first big crush was Capt James T Kirk!), and they were all about man meeting the unknown. My favourite SF novels were Robert Heinlein's Stranger in a Strange Land, Ursula Le Guin's Left Hand of Darkness, Frank Herbert's Dune and Edgar Rice Burroughs John Carter series. Add to which, my all-time favourite book is Alice in Wonderland which I must have read a hundred times, at least!

I've also had a lifelong fascinating with Leonardo da Vinci, whose perception of the world around him was unique. It was almost as if he was a stranger in our world observing things from a fresh perspective. I think there's something to learn from that, and I try to bring that to my own work, seeing the world I'm writing about through completely fresh eyes, taking nothing for granted. It's a personal belief of mine that the world's problems can only be solved by people looking at the situation with fresh eyes, so anything I can do inspire that is time well spent.

You've blogged recently about the effect Edgar Rice Burroughs' work, especially his John Carter of Mars novels, had upon you when younger. But my recollection of those books (and I read them like 20 years ago, so I could be completely wrong) is that they don't have much of a romantic component. Am I wrong? In what ways did those books inspire you to write something like Shadow Through Time ?

The John Carter novels were incredibly romantic! How could you have forgotten! I remember my rapture on first reading these books, how I thrilled to Carter's inherent bravery, and the fact that he'd rather kill a warring opponent than a 'brute beast' (I think that was the vegetarian in me coming out). He had a pet Martian dog, and was a true action adventure hero, a man's man, yet when he met the princess and fell in love with her he was endearingly hopeless.

Early in their romance he inadvertently insulted her, being unaware of their customs, and when she wouldn't speak to him he was gutted. In his narrative he said:

…my foolish pride kept me from making any advances. I verily believe that a man's way with women is in inverse ratio to his prowess among men. The weakling and saphead have often great ability to charm the fair sex, while the fighting man who can face a thousand real dangers unafraid, sits hiding in the shadows like some frightened child.

He knew he was putty in her small, fragile hands, and for the first time (in the eighties) I was reading a male viewpoint in what was for all intents and purposes a romance novel, and finally getting to understand why men act like idiots when they're in love! Mills and Boon novels at the time were all from a female viewpoint, and in any case I craved fantasy worlds and adventures. So these books gave me everything I loved, along with insights into the male psyche beyond battle and bloodshed. That male perspective on falling in love is something I've brought to my own Shadow Through Time trilogy, alongside the adventure that makes fantasy stories so thrilling.

What kind of process do you follow when you're writing? What's a typical day like when you're at work on a book?

What kind of process do you follow when you're writing? What's a typical day like when you're at work on a book?

I find the first draft the most challenging part of the process, and I usually can't do more than about 6 hours a day before I'm emotionally wrung out. I try to write my first draft in one uninterrupted run. When it's flowing I can write 10 000 words a week, so theoretically I can finish the book in three months. Sometimes life intervenes, but I try to offset what I can until after the draft is done. Editing is more like creative bookkeeping to me so I can do longer hours and be interrupted more often.

My first draft is character driven and I write that 'seat of the pants', sometimes stopping to look at goal/motivation/conflict if I get stuck. When I'm finished I do detailed spreadsheets to pull apart my plot and subplots and restructure it to make it tight and interlocking. I have readers who help me with my structural and line edits before I send the manuscript to my agent for feedback and possibly more editing. Then it's submitted to publishers.

Is there an aim for you in your writing – something you want to achieve through your work, over and above creating good stories that people want to read?

My main aim is to entertain. Bringing people pleasure shouldn't be underestimated. It's a worthy goal. Secondary to that is the hope that my character's experiences will inspire readers to look at their own world with fresh eyes. It's also a by-product of the writing that it empties my head of conflict and makes my life tranquil. When I can get all the story out, I'm in my calm centre. When I'm blocked because of circumstance, I'm not as happy. I want to be able to write every day so I'll be happy.

Macmillan have republished the Shadow Through Time trilogy as ebooks, which is very exciting. How do you feel about ebooks and epublishing?

I love ebooks! I bought my first Kindle last year and I adore it. As a completely impatient person I find it miraculous that a whim or internet link allows me to find and download a book in seconds. No more going to the bookstore, maybe finding it out of stock, having to wait until it's ordered in. Then there's the price of ebooks. Most are under $10; my Shadow Through Time series sells for AUD $4.99 an ebook. I can now feed my voracious appetite for books without guilt.

What are you currently working on?

What are you currently working on?

I've been developing an untitled young adult series I've been calling the Medici books and I'm close to handing in the first one. It's based on a lost world discovered by Florentines in the time of the Italian Renaissance. I did a research trip to Rome and Florence in 2010 to help me imagine what sort of culture they would have created in the five hundred years since then. I'm really excited about that story. I've also written an Arabian fantasy in first draft. That has to be edited. Then there's a very, very scary fantasy that I wrote an opening for and need to get back to now that I've had time to work out what the characters want.

–

You can find more of Louise's writing at her blog, which also has full details on her books and the Shadow Through Time trilogy. All three novels in the series are available as ebooks from the Kindle Store, Barnes and Noble and iTunes.

You can also follow her on Twitter as @Louise_Cusack.

In closing, Louise sent me a link to the trailer for the new John Carter movie, which I wanted to share but I can't work out how to embed it in the blog. So much for 'idiot-proof' interfaces! In any case, most of the reviews from people whose opinions I value say it's a lot of fun. Hopefully I can get off my butt in time to see it in cinemas!

March 3, 2012

Flash fiction – Boy

For lunch most days, Hatetooth the Ogre demanded a sandwich, and today was no exception.

'BOY!', he thundered in a voice that could (and did) crack stone, 'MAKE ME A SANDWICH!'

Boy (he had had a proper name once, but it was long since forgotten) crawled out from his tiny pen inside the ogre's throne of skulls. 'Yes, master', he said, voice soft, eyes cast down. 'What would you like on it?'

'WOLF MEAT! POISON IVY! FINGERNAILS! BLOOD JELLY! FEED ME, I'M HUNGRY!'

'At once, master,' said Boy, and backed out of Hatetooth's terrible throne room, littered with bones and the rusty weapons of dead adventurers.

The throne room was at one end of a grisly corridor – called, in fact, the Grisly Corridor – and Boy scurried past the dead gaze of heads lined on spikes along either side. The rusty grating of the floor left stains on his dirty feet, and oily water frothed beneath as he carefully hopped and jumped across the frequent gaps torn open by Hatetooth's gnarled hooves. All was silent except for the gurgle of the water, the hiss of hand-sized spiders as they watched Boy from their vast webs overhead, and somewhere, far away in the caverns below Hatetooth's dreadful castle, the quiet sob of a child who would never go home again.

The sobbing used to be the worst part. But Boy got used to it, just as he got used to a lot of terrible things.

Red light oozed through portcullis bars as Boy made his way through the castle, passing through the Perilous Gorge, the Cave of Stakes, the Blood-Red Tunnels and all the oubliettes, torture chambers and stinking middens that Hatetooth had installed in his fortress. There were dangers aplenty there, and many little horrors and sad adventures to be found along the way, but Boy had been doing this for a long time, so it took only a little pain and a little terror before he arrived at last at the ogre's Grim Larder.

First was bread, or what Hatetooth called bread, which was a block of bone meal mixed with sawdust and bull's blood. Boy hacked off two pieces with a broken sword and laid them flat upon a stone. Then wolf meat, and Boy was just glad that he didn't have to carve the flesh off the old, diseased wolf that Hatetooth kept penned up in the Larder. The ogre had done that himself, and the beast's leg lay rotting on a plate while the maimed animal growled and whined in its cage.

'I'm sorry, Wolf,' Boy said, 'but we're all maimed in here.' And he carved off some slices from the gamey leg and slapped them onto the bread.

The fingernails were the worst part, because they were still attached to the fingers, all severed and dumped in a hessian sack. The ogre liked fingers boiled slowly, so that the skin went soft and jelly dribbled out, and he would suck on them while watching crows fight over scraps on the killing floor of the castle. But he also liked the fingernails, and Boy started pulling them off and chopping them into little bits.

And then a quiet voice said 'Hey,' and Boy turned from the Grim Larder to see Scott from his class looking through the kitchen window.

'Oh. Hey,' Boy said, and closed the fridge door.

'I was wondering if… some of us are going down to the football field to play some soccer for a while. Did you want to come?'

'I, um. That, that sounds like fun.' It did. It really did.

'BOY!' yelled a rough voice from the back of the house, cracked at the end by a smoker's cough. 'WHERE'S MY FUCKING LUNCH?'

Boy turned back to the window. 'But I can't, sorry. My dad, he…'

Scott nodded. 'Yeah, okay. I just thought… okay. Another day, then.'

'Yeah. Maybe. That'd be good.'

Scott looked off into any direction except at Boy's black eye. 'Everyone knows about your dad. Everyone in town knows what he's like.'

'I know. But they don't do anything about it.'

'That sucks.'

'Uh-huh. Look, you better go.' Or you could do something and help me, Boy thought.

But Scott just nodded and said 'Okay', and then he was gone.

'BOY! HURRY THE FUCK UP!'

'Coming, dad,' Boy called, and got back to the ogre's ham sandwich while the three-legged dog whimpered at his feet. He finished chopping up the onions and then found some brownish lettuce in a bag. But he wasn't done yet.

On the shelf next to the fridge was a shallow bowl full of loose change. Boy reached behind the bowl to find the bottle of sleeping pills that his father took on the infrequent nights

He took a pill – no, it was nightshade, deadly nightshade, that was better – and crushed it into powder between two spoons. Masked by a couple of squirts of Tabasco sauce and mixed into the relish, the poison would get into Hatetooth's stomach and join the other doses that Boy kept slipping into his food.

And one day the ogre would keel over dead or unconscious and Boy would fly out the door, onto his bike or maybe a horse, and he would ride into the night and freedom and everything would be better and stories would have happy endings.

Maybe next week. Maybe tomorrow. Maybe today.

Maybe today.

But probably not.

–

Once again you have Chuck Wendig and his regular Flash Fiction Challenge to thank for this story. A few weeks ago he asked readers to come up with a story that was just about making a sandwich but that was nonetheless filled with drama and conflict. As usual, I didn't have time to get something done during the challenge period, but I liked the idea and wanted to get something done when I had the chance. And here it is. It doesn't have much conflict, to tell the truth, but I think it has a fair amount of drama.

Once again you have Chuck Wendig and his regular Flash Fiction Challenge to thank for this story. A few weeks ago he asked readers to come up with a story that was just about making a sandwich but that was nonetheless filled with drama and conflict. As usual, I didn't have time to get something done during the challenge period, but I liked the idea and wanted to get something done when I had the chance. And here it is. It doesn't have much conflict, to tell the truth, but I think it has a fair amount of drama.

Originally this was just going to be a fantasy story about an ogre and a boy, but then the shocking twist suggested itself to me and it became a lot more interesting to write (and hopefully to read). And, to be honest, a bit more emotionally challenging to write; there are parts of this story that, while not exactly autobiographical, are still drawn from personal experience. But pretty much every story draws from personal experience in some way, so no need to make a big deal about it.

This story also gets added to my in-progress anthology Nine Flash Nine, which will have nine flash fiction stories for 99 cents. I'm past the halfway mark on that, and should be able to finalise it by… oh, let's say a month or so after The Obituarist is published. Which will probably be early April, about a month after I had originally planned to get it out, but that's what happens when you spend all of February writing giant fucking posts about book costings.

But anyway, that's in the future, and 'Boy' is today. If you liked it, great! If you didn't, blame Chuck.

February 26, 2012

Big Numbers part 3: Costing the zeroes and ones

So far this month we've mostly been talking about the costs of developing and printing physical books, whether textbooks or novels, using the costing numbers and estimates I work with in my day job. Some of it's been hard and fast, some of it's been a bit squishy around the edges, none of it's been universally applicable but all of it's been honest.

Is everyone still with me? Because now we sail off into the land of conjecture and guesswork – which is a lot like Narnia but with fewer talking mice and feline Jesuses – to talk about the work and considerations that might (emphasis on might) go into making an ebook and how that affects the final cost.

But before we go on, let's split the discussion in half, because when we say 'produce an ebook' we're talking about two different things – making an ebook version of an existing print book and creating an ebook from scratch (a manuscript). There are other options beyond those two, of course, but let's keep this simple.

The ebook version

Let's say that we have our bestselling novel My Dinner With Batman already produced and published, as per last week's post. It's costed to be profitable, the books are in the warehouse, all the production fees have been paid… it's done. So does that mean that it costs nothing to turn the pre-press files into an ebook, that any ebook sales are just a bonus, and that we should just charge 99 cents for the e-version?

…long-time readers probably realise that the answers to my rhetorical questions are almost always 'no'.

For a start, it's going to take some work to turn the pre-press file of the novel (probably a PDF) into a MOBI or EPUB file. You can't just push a button and have a computer do all the work; you can push a button and have a computer do most of the work, but you still need someone to check it, fine-tune it and make sure it displays well on all the potential readers. But having said that, this could potentially be an internal cost for the publisher, and we've been handwaving those away so far, so let's do the same here.

More pertinent is that the ebook sales aren't just free money, because they potentially reduce sales of the print book. Obviously it's not a zero-sum game, and there's a market that just wants physical books and a market that just wants ebooks – but there's also a market that will be happy with either, and the cheaper the ebook the more likely the readers in that market will buy it instead. You've already spent $19 607 printing books with the expectation of selling 4818 of them at $22.95 and making $68 271 in revenue – and of paying the author $8192 in royalties – and the last thing you want is to reduce your bottom line (and short-change the author) by pricing the ebook too low and cannibalising your print sales.

So what do you charge? Well, this is where the hard numbers aren't much help any more. We can use things like our target gross margin (59%), our expected revenue, the unit cost of the physical books (each book cost $3.38 to develop, print and ship) and the rest of our data to give us some ideas, but what we can't really estimate is the size of the overlap between the print and ebook markets and how it will respond to different price points. All we can really do is work on instinct and occasional math.

Well, we know one thing for a start – whatever we charge, we'll only get 70% of it, because Amazon will take a 30% cut. That's assuming we do all our sales through the Kindle Store, which is obviously untrue, but that's probably a solid averaging of the cut the various e-distributors receive. It'd be great to sell direct, and you can do that, but right now you need the various digital bookstores. (This also assumes that you're selling all your books into countries where you get the full 70% from Amazon; sell an ebook to an Australian reader and you only get 35%, which is something that's great for Aussie authors like me with mostly Aussie readers. Just great.) Then we'll also need to pay the author a 12% royalty from our 70% share, so that in the end we only get 61.6% of our asking price per sale.

Well, we know one thing for a start – whatever we charge, we'll only get 70% of it, because Amazon will take a 30% cut. That's assuming we do all our sales through the Kindle Store, which is obviously untrue, but that's probably a solid averaging of the cut the various e-distributors receive. It'd be great to sell direct, and you can do that, but right now you need the various digital bookstores. (This also assumes that you're selling all your books into countries where you get the full 70% from Amazon; sell an ebook to an Australian reader and you only get 35%, which is something that's great for Aussie authors like me with mostly Aussie readers. Just great.) Then we'll also need to pay the author a 12% royalty from our 70% share, so that in the end we only get 61.6% of our asking price per sale.

I mentioned that unit cost of $3.38 per book above. Well, we probably don't want to make less than that for each ebook sale, because if the e-sales do end up cannibalising print sales, we don't want to actually lose money on each sale, right? That would mean – and stand back, I'm going to use algebra – that 61.6% of our asking price should be $3.38 or higher:

.616x = 3.38

x = 3.38 / .616

=$5.48

So we could charge $5.48 – or $5.99 for convenience – for our ebook version? Is that 'fair'? Well, probably not, because that assumes that the ebook sales entirely cannibalise the market for print sales, rather than cannibalising some of it but also creating a new market, and we know by now that that's not the case. It could be cheaper and still make money without damaging print sales too much. If 20% of buyers only ever want ebooks, we could then tailor the price to cover the 80% of sales that risk cannibalising print sales, so that's $5.99 * 0.8 = $4.79, which we can again round up to $4.99. And that's not an unusual price for an ebook.

But at the same time, it could be more expensive and still be fair; we've number-crunched a lower boundary where we don't lose money on the ebook, but we'd actually like to make some worthwhile profits and give the author a decent royalty. Looking on Amazon, it seems like many of the books that would retail offline for around the $20-$25 mark (US, but whatever) have Kindle editions coming in around eight dollars or so. (That's from a skim, and I'm sure there are many exceptions, but let's just go with it.) That suggests that we could go a few dollars higher – let's say $6.99 – and still be pricing our book in a market-appropriate fashion. While we only get $4.30 for each sale (and the author gets just 59 cents), we can hope that the sales volume will make up for it and that we still end up selling all the print copies we had planned to over the three-year sales period.

…or not. It's guesswork. But it's guesswork that publishers have to make to create non-hypothetical ebooks, and everyone's going to come to a different answer. It's going to depend on the costs of the print book, the market you're selling to, the additional resources required to produce and market the ebook, the danger of cannibalising print sales, the potential of long-term sales long after the physical books are all sold… Dump some numbers in a hat and pull one out. Or look at the numbers other publishers have pulled from the hat and do the same thing. Or charge two bucks and go all in. Let it ride.

But still. Maybe we can look at this and say when a publisher charges $4.99 for the ebook version of a $22.95 novel, it may not be from greed or lack of awareness of the market; it may be because that's what the spreadsheet demands. For now.

Original ebooks

And finally let's talk about independent, author-created ebooks. This is a very different ballgame because we step away from the requirements and costs of a publishing company and a print book, but we also step away from the production infrastructure and larger budgets to DIY it. But we can still look at the costs from the previous examples and see what's applicable. And hell, I've made a couple of these, so I can share the fruits of my minimal experience.

Let's assume we're going to produce a novel of about 200 pages – well, no, because ebooks repaginate themselves based on the device and the user's preference. We're probably better off thinking in terms of wordcount. Let's say this new book… You know what? Let's actually talk about my novella-in-progress, The Obituarist, and use it as an example here; if nothing else it'll help me work out how much to charge for it when it's done.

My target for The Obituarist is 20 000 words; it won't be exactly that, but it's close enough for disco. So if we think back to last time, what are my costs?

Manufacturing costs - zero. That was easy. It means my mother will never read the book, but I can live with that.

Editing - page rates aren't appropriate, so we're either paying by the hour or by the word. Looking online, I can see rates of around 2-4 cents a word being offered by editors. While I could get something at the low-end without much trouble, let's assume I pay the middle rate of 3 cents a word, which would cost me $600.

Proofreading - a page rate is again hard to calculate. It's also difficult in a situation like this to distinguish cleanly between an editor's role and a proofreader's role. Probably the simplest thing is to bump up the page rate for the editor so that it covers proofreading as well; another half-cent a page will cost $100. In a perfect world it'd be good to have a separate proofreader to catch mistakes the editor misses, but little is perfect on this bastard planet.

Typesetting - none, because we're not laying out final pre-press files in a stable format; we're taking a text/Word file and converting it to EPUB or MOBI. Which in theory is pushing a button, but like I said above, it'll probably require tweaking and fine-tuning. If I was going to pay someone to do it for me, I'd expect it to take about an hour, so I'd probably pay that person (which would probably be the editor) $50; since it's not difficult, so I'll do it myself for nothing.

Text design – there almost isn't such a thing with ebooks, although you still want to start the process with an idea of how things will look at the other end. Still, fonts and layouts are morphable things and mostly up to the reader, not the writer. We can fold this into the typesetting cost, which is nothing.

Cover design – this is the place where a lot of ebook authors try to save money and do it themselves. Stuff that. I think that a strong, professional cover is pretty much your third priority when making an ebook, after writing a damn good book and making sure it's been edited. It doesn't have to be spectacular, it doesn't have to be 100% original, but it needs to be polished and it needs to show readers that you take this shit seriously. The covers of Hotel Flamingo and Godheads were created by a Melbourne designer (Design Junkies, who are great) and cost me about $220 each. I might not use the same design concept for The Obituarist, or indeed the same designer – it's good to mix things up occasionally – but I figure that I'll pay something similar. Let's call it $250.

Cover design – this is the place where a lot of ebook authors try to save money and do it themselves. Stuff that. I think that a strong, professional cover is pretty much your third priority when making an ebook, after writing a damn good book and making sure it's been edited. It doesn't have to be spectacular, it doesn't have to be 100% original, but it needs to be polished and it needs to show readers that you take this shit seriously. The covers of Hotel Flamingo and Godheads were created by a Melbourne designer (Design Junkies, who are great) and cost me about $220 each. I might not use the same design concept for The Obituarist, or indeed the same designer – it's good to mix things up occasionally – but I figure that I'll pay something similar. Let's call it $250.

Other costs – no, not really.

So there's a total cost of $950, which is a lot for a dude like me to fork out. In practice, I'll probably be able to get the editing and proofreading done by friends in return for doing the same for them in the future, or as payback for help I've already given them. I'm lucky there in that I have friends who are writers and editors and who can help me out. But if they can't, then I'll have to wear that cost.

So what should I charge for the novella?

Well, if it's more than 99 cents, I can demand the full 70% royalty from Amazon – but as pointed out above, I'll only get 35% for Australian sales, which will be most of them. I'll get a more consistent royalty from Smashwords (between 66% and 75% for direct sales, less about 15% for affiliate sales) but generally expect fewer sales from them. Without really good stats about who's buying and from where, all I can really do is assume the median value, which is going to be around 55%.

Let's say I charge $2.99 for The Obituarist, which is what I was charging for my other, shorter ebooks before I pulled them down to 99 cents at the start of 2012. That means I can expect about an average of $1.65 for each sale. So if I can make a deal-in-kind on the editing and proofreading, I only need to pay the $250 for the cover, which I'll do after selling 152 books. If I have to pay the entire $950, I'll need to sell 576 books just to break even, and previous experience tells me that that is not very likely. If I charged $3.99, I'd get $2.20 per book and would break even after 114/432 sales. Better, but the market isn't likely to respond positively to that price for an indie book. And if I go lower than $2.99 I'm cutting my own throat, because the royalty rate would also drop; at $1.99 I'd probably only get around 45% and it would take more than 220 sales just to make up for the cover costs.

So is $2.99 a fair price for a novella like The Obituarist? I don't know if that's the right question, because 'fair' is going to have a different meaning for the reader than it does for me. What I can say is that, assuming that I can work out the editing costs in trade and pay with my time rather than my money, and assuming that I can devote more time to promoting and marketing the book in useful places, and assuming that I can maintain that price for a decent period without the need to discount, I've got a pretty good chance of paying off my costs eventually, or at least defraying them to the point where I don't feel like I've pissed $250 up against a wall. Which is not exactly comforting, but the game is what it is.

But I'm not really trying to justify charging whatever I eventually charge for a book I haven't finished writing yet. What I'm hopefully doing is showing you, the reader of this here post, that even the humblest DIY ebook operation has costs, and that it's worth working those out ahead of time so that you're not surprised by them or left shocked by how much work is still required to make it all come together. Because what I've learned in my day job is the value of planning and costing a project ahead of time – and, sometimes, to look at the poor projections and say fuck it, let's do it anyway.

Don Quixote is my spirit animal.

–

2500 words on this today, and I could keep going. But I think the point has been made by now about what it might cost to make a book, physical or otherwise, and if it hasn't then I probably can't make it even with another 2500 words. So let's call it a night.

In the aftermath of these three posts I'm going to be a bit quieter on PODcom through March, because I want to finish The Obituarist – and get it edited, and pay for a cover, and etc – and publish it online before the start of April. And time spent writing mammoth blog posts is time not spent writing about Kendall Barber getting beaten up by bikers.

Which doesn't mean I'm closing up shop. I'm still aiming for 1-2 posts a week, and will be offering up some flash fiction next week as a relief from all the number crunching. But they'll be shorter, faster posts that don't require sitting in a hot office for four hours to get them done.

Until next time, true believers.

February 19, 2012

Big numbers part 2: My Dinner With Batman

So last week we looked at the cost breakdowns and predictions for a secondary school textbook, using a real costing for a real textbook published by my real day job.

But textbooks are something of an outlier in publishing, with specific and potentially expensive requirements such as image permissions and complex text design and layout. A standard novel doesn't have those same requirements, and some of the costs it has will be lower. So we can't just extrapolate from textbook costs to say that a novel will cost x dollars; we need a different set of numbers.

Which, yet again, I have.

But first, a few quick caveats and qualifiers.

1 – I forgot to mention it last week, but part of the business of publishing is that you rarely sell directly to the reader/audience; you sell to a bookseller or distributor for a percentage of the cover price, who then sells it to their customers. The bookseller gets about a 33% discount, so the publisher's revenue is roughly 67% of the price. That's factored into the final figure I quoted, but not stated in the working to get there. Sorry. Oh, and you have to calculate for GST somehow.

2 – Just to repeat last week's disclaimer, these are real numbers but they aren't universal numbers. I'm certain that other companies in other areas of publishing would have different costs and maybe a very different balance between those costs. I'm not trying to say this is how it always is, just this is how it is for some operations. I hope this real data is educational, but that's all it's meant to be.

3 – The aim of this exercise isn't to prove that ebooks should be more expensive, although I can see how the preamble to the last post may have given that impression. All I want to do is get people on the same page and share some information about what goes into making a book, whether physical or electronic. I don't have an agenda; I just want to show off how clever I am spread some knowledge.

So anyway, tonight I'd like to calculate and project the cost of producing a novel. Now, we don't publish novels where I work, so I can't give perfectly accurate numbers this time. I did, however, publish a number of anthologies in the last couple of years, which combined short fiction with writing/comprehension exercises. Those books had much more 'traditional' editing/typesetting/design costs, so we can use those details to extrapolate a composite book that has largely accurate ideas of costs.

What should we call this imaginary novel? Well, in keeping with the usual themes and motifs of this blog, I'd like a semi-literary, semi-genre work that's heavy on metatext. How about… an 204-page novel about a meeting with a fictional character and the subsequent discussions about purpose, heroism and intellectual property rights.

I call it My Dinner With Batman.

This is why you need a cover designer

Development costs

Editing – Last time was about $40 a page; this time we'll drop down to $30 a page, for a total of $6120 (you quote based on total page count, even if some are blank). That's pretty reasonable, given that the standard fee of a freelance editor is $50 an hour. The editor will be copyediting to fix grammar and sentence construction, but also doing a substantive edit to make the writing and the story better.

Proofreading – A dollar a page is probably fine, for a total of $200 (we'll round this one down to a convenient sum).

Typesetting – $2496. That's about $12.24 a page, which is much lower than the $33/page cost we had for Cooking with Graeme. Typesetting is much simpler for a novel than a textbook, but it still requires attention, care and a couple of passes through page proofs to fix mistakes.

Text design – $800. Yep, that's exactly the same as it is for the textbook. Part of that is because it's a basic cost that designers don't vary much, and part of it is that novels require text design too – font choices, layout styles, design elements that make it more than just plain text. Anything that sees print is going to need more than just a dude plugging it into Word and exporting to PDF or InDesign, and $800 is a small price to pay for My Dinner With Batman to be not just professional-looking but simply readable.

Cover design – $850. A bit cheaper than the textbook, mostly because it's simpler, but not much cheaper. And this is just for designing the concept and layout of the cover; it doesn't cover the cost of artwork. That comes under…

Illustrations – $650, which is for the cover. We're assuming no internal illustrations for the book, which isn't going to be the case all the time; lots of Very Serious Novels still have the odd illo inside to break up sections. But not this one.

Permissions – Nothing this time round, because this is a 100% original work that involves no photos, text extracts or agreements that allow us to use Warner Brothers' trademarked characters. Which means we're gonna get sued, but hey, so it goes.

Software development, image scans, some other stuff – look, let's not worry about any of that, okay?

Miscellaneous and contingency – $336. Hey, I don't make these numbers up, I just report them.

So our total development costs for this first print run – remember, there are two – is $11 452. This is quite a bit cheaper than the book I'm using as my model, because it had a big permissions budget, but we're primarily extrapolating this time around.

Manufacturing costs

Just two costs to worry about here for our initial print run, which is going to be 3000 copies.

[image error]Printing and binding – $3990. Now this is for a two-colour book that uses a second colour (e.g. the midnight blue of Batman's cape) to give the pages more visual pop. A true black-and-white print run would be even cheaper, but this is still costing just over a dollar a book to print.

Freight – $415 to ship 3000 books from China to Australia. That's even cheaper than it was for the textbook because the books have a smaller page size.

Total manufacturing costs – $4405.

Second print run

Let's just extend this out for another run of 2000 copies, which will give us three year's worth of books and projected sales.

Development costs – just $154 budgeted for contingencies.

Manufacturing costs – $3320 for printing and $276 for shipping, for a total of $3596.

So let's stick it all together for a total cost – to edit, develop and print 5000 books over two runs – of $19 607. Which straight away tells you that novels can be a lot cheaper to produce than textbooks.

Financial voodoo

We've printed 5000 books but we only plan to sell 4818; the rest go towards marketing, archiving, author copies and the like (mostly marketing). The author's royalty is 12% and the target gross margin is a minimum of 55% (same as usual). So how much do we charge for this book?

Well, the anthology I'm using as the basis for this sold for $29.95, which was enough to bring in a projected $89 203 in sales (meaning $10 704 in royalties, which doesn't suck) and a margin of 58%. But that book cost about $7000 more to make than this one, so we'd expect a higher margin. And if we crunch the numbers for the same receipts, we in fact come to a final cost (including royalties) of $30 311, meaning the final margin is 66%.

Wow, that's good. Too good, probably; as the publisher, I could easily bring that $29.95 price down and still make my 55% cutoff. A lower price means less profit and lower royalties for the author, but it also means the book is perhaps more likely to sell – and that the price is fairer to the customer. Which matters, believe it or not.

Lemme play with the numbers a bit and spit some totals at you, which I'm working out on the back of a piece of paper because I'm honestly not very good with spreadsheets. If we assume the same sales (4818, giving up 32% to the bookseller):

$27.95 retail – $83 303 in sales, $9996 in royalties, $ 53 700 in profits, 64% gross margin

$24.95 retail – $74 293 in sales, $8915 in royalties, $45 771 in profits, 62% gross margin

$22.95 retail – $68 271 in sales, $8192 in royalties, $40 472 in profits, 59% gross margin

$19.95 retail – $59 414 in sales, $7129 in royalties, $32 678 in profits, 55% gross margin

Okay, so $19.95 is as low as I can go for a 204-page book and still make it worthwhile to produce. To be honest, I'd probably for the $22.95 price point instead; it's still a fair price, it means the author gets another thousand bucks in royalties for his hard, wildly illegal work, and the extra profits help pay a bigger chunk of my wage. I got bills, girlfriend.

In closing…

[image error]What do these numbers mean? Look, not as much as I might like. They're pretty accurate (except when they're just guesswork), but they're predicated on a certain set of margins and expected costs and for a print run/sales target that some publishers would find wildly optimistic and some wouldn't bother getting out of bed for.

But still, the numbers tell a story. A story that's not just about Batman, but about what might go into making a printed novel you can find at your local bookseller, assuming it wasn't Borders.

What about ebooks? What happens when there's no physical product and very different design/typesetting needs and costs? Well, then we venture into the crazy world of Educated Guesswork. Come back next weekend to explore that world with me.

Bring a pith helmet. Things just plummet from the sky all the goddamn time in the Land of Educated Guesswork.

February 16, 2012

Amundsen or Mawson?

Hey, just a quick mid-week update, as I've been busy clearing my study so that housepainters can come by tomorrow and make it the same colour as the rest of the house. Whatever that is. Some sort of cream.

Anyway, on the weekend my wife (!) and I went to Hobart for a friend's wedding, which was fun. (And occasionally a little weird, but still fun.) I only took the one book with me, Alan Bissett's Death of a Ladies Man, which I sadly abandoned on Saturday morning. The writing style was very interesting, but the narrative itself wasn't anything new and it wasn't going anywhere. I'd like to read more of Bissett's work, but that book ain't for me.

Which brings up an interesting question, one inspired in part by the statues and markers around Hobart concerning Antarctic expeditions. When it comes to reading, are you Roald Amundsen, someone who'll keep going despite disaster and privation and really bad writing to reach the end of a book once you start it, whether or not you're enjoying it, just because you can't give up? Or are you a Douglas Mawson who turns back once someone dies and the supplies run out and the clichés just get too much to endure?

CLOSURE OR DEATH

I'm a Mawson, always have been. Life's too short and there are too many good books out there to keep enduring with bad ones, or even lacklustre ones. If a book doesn't hook me in the first chapter or two – hell, sometimes in the first half-dozen pages – I'll chuck it aside and move onto the next one. And I know that that means I've missed out on many good books that take a while to build up steam, but such is life; there are other good books that can grip me by the nutsack in minutes, and enough of them that I'm not going to run out of reading material or inappropriate groin-based metaphors any time soon.

But that's me. What about you? Do you stick with a book until the bloody end, and if so, why? Alternatively, if you're ready to abandon the expedition once the porters are eaten by wolves and turgid first acts, do you ever regret that?

Come on, leave comments. Comment leavers get all the loving.

(PS: I'm fully aware that I may have it completely wrong on Mawson versus Amundsen. DETAILS!)

February 13, 2012

Big numbers part 1: Anatomy of a textbook

A few weeks ago I was cruising the Australian users thread on the Kindle forums, looking for opportunities to plug my ebooks insight into how Aussies are reading and buying ebooks. One of the recurring themes I noted from skimming that huge thread (with hundreds of new posts every day) was that physical books were too expensive, and that ebooks should be much, much cheaper – after all, the main costs involved in making a book are printing, shipping and storing, and there's none of that with an ebook, so they should be a fraction of the cost.

I found that interesting because I'm in a position to know that it's completely wrong.

See, when I'm not writing blog posts full of insight or playing video games in place of working on my novel/novella, I work as a commissioning editor for a major international educational publishing company that I prefer not to name. (It's not a secret or anything, but I like to compartmentalise things.) I edit and publish textbooks, mostly maths textbooks, and as part of that process I help crunch the numbers that lets us work out how much a book will cost, how much to charge for it and whether it's worth publishing in the first place. And that costing process paints a very different picture of how it all works.

So I thought it might be fun – and even better, useful – to pull up a set of costings for a fairly typical secondary textbook and go through them with you. They're not universal numbers, of course, but they're real numbers rather than something made up for an argument. And while these only apply to a textbook, which has specific needs and features other books don't have, they can serve as the starting point from which to extrapolate further – which I figure we can do next weekend, since this is going to be a pretty long post. (Correction: it's a really fucking long post.)

Before making this post, I checked with my boss that it was okay to draw on real data, and she was fine with that. Still, in the interest of protecting my source, the numbers are accurate but the names have been changed. So let's pull apart the costings for Cooking With Graeme, a 212-page Home Economics text in which everyone's favourite cat teaches 14-year-olds about the nutritional value of raw mince and his secret turkey ice-cream recipe.

[image error]

Why am I always the example?

Development costs

Before there is a book, there is a manuscript, written by a team of authors dreaming of fame, credibility and a decent royalty payment. Let's say you have that. That's not a book; that's not even the idea of a book. That's your raw material, and a lot has to be done before it can go to print.

Editing – $8672, which is roughly $40 per page. That's a combination of copyediting (finding and fixing grammar and spelling errors), substantive editing (improving the text to make it more effective), fact checking, tweaking the layout, matching text to images and a bunch of other things, repeated through several iterations of layouts (or 'proofs') to get things right. It's a skill that goes above and beyond simple proofreading – in fact, there's a separate proofreading budget and that's just $200, or about a dollar per page. Editing costs, but it's utterly vital; even the best manuscript will have errors and problems, and even the best typesetter will make mistakes and misinterpret instructions.

Typesetting – $7072, which is about $33 per page, although it's not just based on page count. Typesetters take the edited manuscript, all marked up with the editor's instructions as to what goes where, and lay it out onto what will be the finished page that the reader reads. Again, it's a technical skill, not just a matter of dumping everything into InDesign, that requires attention to fonts, kerning, page size, paragraph/page/section/chapter breaks, styles, flowing text around images and a bunch of other things. Textbooks are some of the most finicky and complicated books for layout (as are RPG sourcebooks, for much the same reasons).

Typesetting – $7072, which is about $33 per page, although it's not just based on page count. Typesetters take the edited manuscript, all marked up with the editor's instructions as to what goes where, and lay it out onto what will be the finished page that the reader reads. Again, it's a technical skill, not just a matter of dumping everything into InDesign, that requires attention to fonts, kerning, page size, paragraph/page/section/chapter breaks, styles, flowing text around images and a bunch of other things. Textbooks are some of the most finicky and complicated books for layout (as are RPG sourcebooks, for much the same reasons).

Text design – $800. Not very much, but it still costs something for a designer to give your book its distinctive look – to choose fonts and colours, styles of headings and sections, page trim and visual elements and everything that makes the book more than plain black text. In fact, books that are plain black text still need some degree of text design.

Cover design – $1000. That's front cover, back cover and spine; it's choosing images, designing the title and subtitle(s), fitting the blurb and other information onto the back in a useful and appealing way, making sure the spine is exactly wide enough for the pages and so on and so forth.

Illustrations – $1000. Cartoons, complex diagrams, maps, artwork and anything else the typesetter can't do themselves. $1000 might buy anything from five to 50 illustrations, depending on type.

Permissions – $2000 to purchase the right to print/reprint other people's copyrighted material. For a textbook that usually means photographs, but it also covers text extracts from primary sources and other books. $2000 isn't much, and means this book will primarily use general images from stock libraries and collections, rather than highly specific images that carry a high price tag.

Software development – $500. This goes towards any digital material, such as extra material on CD-ROM. Often this money doesn't get used up, especially as publishers move towards putting that material onto a single proprietary website with a standardised interface, but you budget for it anyway. Anything more complicated probably gets costed as a separate product.

Miscellaneous and contingency – $391 on this specific book. Yeah, it's a weird little number, usually a small percentage of the other costs, just there in case a freelancer goes mad and eats the manuscript and we have to pay to get her stomach pumped.

Other costs – none on this example, but other projects might require non-royalty-based author fees, manuscript development fees, indexing (which ain't cheap) and a number of other costs. They all have to be costed beforehand.

Manufacturing costs

The above costs all go into getting the content into shape. You don't have a book yet; you just have the extensively-developed plan for a book. To actually make a physical product, you have two (occasionally three) more costs.

Printing and binding – $7400. That's enough to print, in this case, 2000 full-colour books. Printing more would bring the per-book price down – 3000, for instance, would only cost $700 more – but you work out the print-run based on sales projections and don't print books you can't sell just because the ones you can sell will be a little cheaper.

Printing and binding – $7400. That's enough to print, in this case, 2000 full-colour books. Printing more would bring the per-book price down – 3000, for instance, would only cost $700 more – but you work out the print-run based on sales projections and don't print books you can't sell just because the ones you can sell will be a little cheaper.

Freight – $534 to bring 2000 books over from China to Australia. Not much, really, but that's because they're on a boat with a couple thousand tonnes of other stuff. Not every publisher prints in China, of course, but it's the best option for publishers in this country creating full-colour material; printing locally would cost much, more more.

CD duplication and packaging – $1018. This book comes with a CD, which only has a PDF of the book. Those are pretty much history now as publishers move onto online models, but I'm including it for the sake of accuracy.

And that's it. Developing the book before printing cost $21 635; creating 2000 physical books cost only $8952. Less than a third of the overall cost.

Setting the price

So you know you're spending $30 587 to make 2000 books. Now how much do you charge for it? Well, 30 857 ÷ 2000 = 15.42 – so about $16, right?

Um, no. Not if you want to publish any more books in future.

There are two main considerations you take into account to set the price.

Royalty – oh yeah, that's right, you have to pay the writer. Royalties are a percentage, so you have to calculate them off expected sales and after you set the price point of the book. In this case, we're paying a 12% royalty (which is decent) on expected sales of 1841 copies of Cooking With Graeme (the other 159 are channelled into sales/marketing activities), and we can backtrack to estimate out how much that actually is once we set a price and work out expected sales.

Don't ever just image search for the word 'gross'

Gross margin – this is the big one. It's not enough to break even, and it's not enough to make a profit – you have to make enough profit to make the whole activity worthwhile. You particularly have to make enough profit to pay the salaries (or part of the salaries) of the in-house staff who worked on it – the publisher and project editor who oversaw it, the production staff who coordinated the printing, the sales and marketing teams that get people to buy it and several others. And on top of that, you need to make enough profit to keep the business going to make more books that people want. Not every book will make a squillion bucks – it's pretty much only the maths textbooks – but every book needs to provide a decent return on investment.

So you aim for a minimum gross margin – which, if you're not familiar with the term (I wasn't because money confuses me), is the percentage of sales income that is profit – of 55%, or maybe some other number, but that's the usual we work with. Slightly more than half of your price needs to be profit. And to be honest, you're better off aiming higher than that, because otherwise you should have just given up and made another book about trigonometry instead of adorable cats.

The bottom line

In the end, these considerations go into a blender (or more accurately a spreadsheet) and after some back-and-forth and rending of garments it spits out a price of $49.95 per book. Which, in turn, adds $5685 in royalties to the costs, which the spreadsheet somehow manages to take into account, so it costs $36 271 to make 2000 books, which we expect to bring in $56 847 in receipts.

If you have a calculator, you can work out that that's only a 36% gross margin, which seems to belie everything I've just said. But the above figures apply to a single print run, while in actuality you usually plan and cost two print runs that cover 2-3 years worth of sales. Planning is everything, and the second print run is often the one that actually makes the money. That first printing has all the development costs beforehand; the second print run doesn't have any (hopefully), just printing and shipping costs, which drive the gross margin for that run way down, and you clump them together to make that target of 55%.

See, I can handle maths. But this is accounting, and it makes my head bleed.

Anyway, our second print run of Cooking With Graeme is 3000 copies; we put aside $296 for development contingencies, just in case, then spend another $10 943 for printing and shipping the larger print run. Expected income is $92 573, and expected royalties are$9257; the book really starts to pay off for the author in that second year. Gross margin for the run is a whopping 78%, proving that books would be much more profitable if you didn't have to spend time and effort making them readable.

So our total investment is $56 768, our income is $149 420, out actual profit is $92 653, and our gross margin is 62%. If Cooking With Graeme does as expected – and remember, these calculations are made before a single word is written, much less a single book is sold – then it's been a worthwhile publishing project. We could have maybe dropped the price by $5 and still hit the 55% target, but that's about it; no possibility of selling it for $20 and still staying in business.

Now what?

So that's how a textbook gets created and how much it costs. In next week's blog post, I continue acting like a lecturer at the world's least-respected accounting college and talk about how we can extrapolate those number to understand how much regular ol' novels cost to make and what costs still apply to ebooks.

Sounds exciting, no?

February 8, 2012

Where the bloody hell are you?

When the internet first broke through the egg and pecked the datagoo from its downy wings, a lot of people (well, me at least) thought that the Web would be like a series of big rooms at a party. You'd put all your stuff in one room and play with it, and other people would come by with drinks in hand because they wanted to see and play with your stuff, and you'd have fun and get drunk and maybe accidentally sleep together, and when you wanted to check out their stuff you'd go to their room and hang out and maybe accidentally sleep with them and soon the party would be pumping and every room would be a comprehensive storehouse of one person's presence and there would probably be fucking.

As you can see, this metaphor does not work. Although the internet is full of rooting, that much is true.

As you can see, this metaphor does not work. Although the internet is full of rooting, that much is true.

Instead the internet has become more like a network of swingers' parties, where you leave a set of your keys in bowls across your suburb and okay fine I'll stop with the inappropriate metaphors, spoilsports.

But yeah, the notion of the one-stop portal or the one site where you have your presence and that everyone comes to is pretty much cactus these days. Instead our presence is balkanised, divided up into manageable, focused portions that do a specific thing and hopefully do it well. When I set up this site, I wanted it to be the hub of that online presence, and it's serving pretty well as that, but I can also be found in a bunch of other social media/commentary sites, in case you wanted to stalk me. And you know, I'm okay with that, so long as you're the kind of stalker who buys their target a beer rather than cuts their feet off.

Please don't cut my feet off.

So anyway, I've been thinking a lot about the way we spread ourselves over the internet as I work on The Obituarist, and decided to do a run-down of the various places I've left a notable footprint. This is where I am:

Here. Duh.

LiveJournal - I blog as artbroken over there, and back in the day I used to blog a lot. Like once a day minimum since 2002. But the old grey mare she ain't what she used to be; LJ started to fall apart under the weight of mismanagement and ugg boot spam, everyone pissed off to Facebook and I stopped being so goddamn angry all the goddamn time. Now I post something there about once a month, usually about gaming, negativity or why I don't post much to LiveJournal any more.

Facebook – Of course I'm on Facebook. Everyone's on Facebook. It's practically mandatory. These days I mostly use it to help coordinate social events, pimp blog posts, check in with what my wife and a few friends are doing and post the very occasional cool link. I keep feeling like I'm doing something wrong, and it could be so much more if I let it. But stuff that.

Google + – I was a fairly early adopter, and like some early adopters I keep wondering if I should go back to the orphanage and see if they have a smarter kid lying around. G+ seems to be a Facebook alternative without the depth of social tools or significant audience, and all I ever post there is links back to posts I make here. Maybe one day it'll shed its cocoon and become a beautiful butterfly.

Twitter - Man, I fucking love Twitter. I dragged my feet over getting onto it for the longest time, and since then I've racked up like 6500 tweets in two years. It's a great place to explore brevity, for one thing; it's about communicating effectively in a small space, stripping out detail to develop nearly glyphic forms of text. Or to dump links and make smartarse comments about politicians.

Amazon - I have an author page there, which has information on Hotel Flamingo, Godheads and a bunch of RPGs that don't provide me with any royalties. But I can't find it in my heart to let them go. The Amazon page is barebones, but if people leave positive reviews on things, that might bulk it out. Hint freakin' hint.

Smashwords - I have an author page here too, with links for the ebooks and the various free stories up there. It doesn't compare visually to the Amazon page, but there's more of my own stuff to read.

Goodreads – Aaaaand I got an author page here too. Although I don't sell any stuff through the site, so it's mostly just a feed from this blog and a general request to please god help a brother out with some reviews and recommendations, pretty please man I need this homes.

– I really don't know why I'm on here. I've never done anything through the site, and mostly get contacted by people I barely know who seem to just want to professionally network for the sale of professional networking, rather than because they genuinely want to forge business/editing connections. But hey, maybe one day it'll pay off.

Flickr - I have some photos here. They're pretty old.

RPGnet – I go there to talk about roleplaying. Which I used to do a lot, back when I was writing RPGs and had more spare time and was generally much grumpier. Now I just pop up occasionally to say something semi-constructive and then vanish again, leaving only the links in my signature block.

Obsidian Portal – Ooh, such a spooky name! This is where I write about my D&D game. If that doesn't interest you much, I understand. If it does, go check it out. We have session writeups and a pretty detailed wiki.

That's about it, I think, other than the various banks and online stores that make posthumously cleaning up someone's online identity traces such a chore. If Kendall Barber was obituarising me I think it'd be fairly straightforward. And a bit freaking meta.

How about you? How thinly is your identity butter spread across the crispy toast of the internets? Where do you pitch your tent online? And do you have any stories about good ways to use LinkedIn or G+? 'Cos I'm struggling with them, I really am.

February 5, 2012

Stuff and nonsense

So I had a really, really good plan for a blog post tonight, one where I had facts and figures and could talk with authority about practical matters.

But I left all my notes at work.

So this is not the best blog post in the world. This is just a tribute.

[image error]Or, to be more accurate, just me talking quickly about a few good things, much like I keep meaning to do with those Thursday night posts. Which are going to become Wednesday night posts, because people keep asking me to hang out and do stuff on Thursdays.

–

Music

I saw My Chemical Romance this week. Good gig! Less theatrical than I had expected from the band that gave us Danger Days and Welcome to the Black Parade; no costumes, no pyro, no crazy lighting displays. Just guys playing rock and roll, which is cool. I like gigs like that. And most of the kids in the pit were actually dancing, rather than just standing there filming the show on their iPhones, which made it an improvement over, say, Muse last year.

I've also been listening a lot lately to Sleigh Bells and Childish Gambino, both of which (whom?) I should have been listening to long before now.

–

Comics

My wife got a stack of BPRD trades for Christmas, so I've been catching up on those and on Hellboy. BPRD is a really intriguing series in the way it counterbalances high-stakes action-horror, like giant Cthulhuesque monsters rampaging across America, with more street-level material drawing from a variety of real-world sources and then partially gonzofied. It's really clever stuff, and the art at this point in the series is by Guy Davis, so of course it looks amazing. (One of the high points of my game-writing career was having my words on the same page as Davis's art. A-MAZE-ING.)

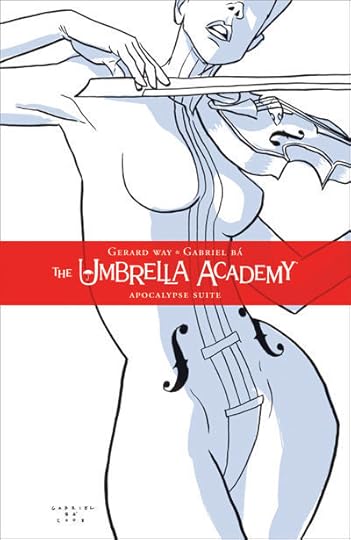

In celebration of the MCR gig, I also reread Gerard Way's two Umbrella Academy collections, which are surreal and occasionally disturbing superhero comics that drench pop art in Grand Guignol and outright silliness. I hope he eventually does a third series, or alternatively makes good on his promise to write a Danger Days title.

In celebration of the MCR gig, I also reread Gerard Way's two Umbrella Academy collections, which are surreal and occasionally disturbing superhero comics that drench pop art in Grand Guignol and outright silliness. I hope he eventually does a third series, or alternatively makes good on his promise to write a Danger Days title.

And then there was the news of DC Comics doing a bunch of Watchmen prequels. But we're only talking about good stuff here.

–

Games

2012 is shaping up to be a big nerdy year for me, with my D&D game back on schedule as of today (it was cah-razy) and joining another campaign being run by the excellent Mister Kevin Powe. The news that yet another bloody edition of D&D is in the pipeline has made me appreciate the kinetic, cinematic fun of 4th Ed even more, and I'm looking forward to playing the hell out of it and not bothering with the new shinyness.

I also just finished Dragon Age II yesterday, which was a disappointment but not a crushing disappointment. From a weak start it eventually starting raising stakes and exploring themes, and the gameplay was generally fun, but still, riddled with problems. Much like my post on Arkham City, I think I could write an essay on DA2's plotting problems, specifically talking about the consequences of actions (or lack thereof) and the need to build a cohesive narrative rather than just a patchwork quilt of events. Maybe another time.

More importantly, I have the videogame monkey off my back again, and can devote more of my time and imagination to writing. Which I'll do. Scout's honour.

(Fun fact: I was kicked out of the Scouts.)

–

Books

One thing I'm excited about right now is the news that Louise Cooper's Shadow Through Time trilogy, published in the early 2000s, is coming out in ebook form. This was a really solid romantic fantasy series that deserved better exposure than it received, coming at a time when Australian fantasy was experiencing a high point in local publishing and sales but still not making headway into international markets. The ebook format will hopefully change that (although Australian ebooks still have to work hard to find UK/US readers, which is something worth talking about sometime in the future).

One thing I'm excited about right now is the news that Louise Cooper's Shadow Through Time trilogy, published in the early 2000s, is coming out in ebook form. This was a really solid romantic fantasy series that deserved better exposure than it received, coming at a time when Australian fantasy was experiencing a high point in local publishing and sales but still not making headway into international markets. The ebook format will hopefully change that (although Australian ebooks still have to work hard to find UK/US readers, which is something worth talking about sometime in the future).

Plus, hey, great new covers.

So anyway, if you'd like romantic fantasy that's a cross between Alice in Wonderland and Excalibur, you should definitely check these out.

Right now I'm reading Alan Bissett's Death of a Ladies Man, and struggling with it a bit. The writing style is fascinating – fragmented, poetic and playful – but the pace is slow and I'm finding it more difficult than I expected to sympathise with the main character. But damn, the style is really intriguing.

After that, my to-read list includes Jeffrey Eugenides' The Marriage Plot, Lev Grossman's The Magician King, Duane Swierczynski's The Blonde and Guy Adams' The World House on my table. (I don't know anything about that last one, but I wanted to check out the sort of thing Angry Robot Books is publishing.) If you want to know when I get around to them and what I think of 'em when I finish, you could follow me on Goodreads. Would that be interesting? I'm still not sure what Goodreads is really for, but hey, if you're on there, you could do worse than follow me.

–

Graeme Riley, Ace of Cats

He's doing better, thanks for asking!

[image error]

–

Okay, that's enough chitchat for one night. Back to more focused topics next time.

And now, sleep.

January 30, 2012

The Triumvirate

All writers have influences, whether those are other writers, artists, musicians and creators or sources closer to home like friends, family or the next-door neighbour whose ideas we steal at night using our radio poison devices. Some of them are sources we know about and examine; others are unconscious influences we don't realise or admit even to ourselves, much less the crazy paranoid next door who glues tinfoil to his forehead to block you once and for all.

I mean, seriously, if his ideas are so precious, maybe he shouldn't leave them lying around pinned to stolen undergarments. It's just asking for trouble.

Anyway, this week I've been thinking about my influences, and I thought it would be fun to narrow them down to an arbitrary Top Three and talk about how fucking awesome they are. Or were, since they're all old dead white dudes.

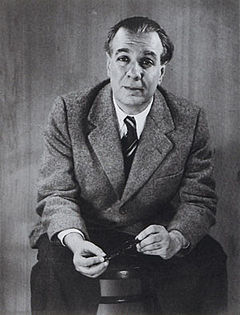

Jorge Luis Borges

Despite never being sure how to pronounce his name (Bor-jez or Bor-hez?), I've loved Borges' work ever since stumbling across 'The Library of Babel' in some anthology or other back in my university days. Then I read 'Tlon, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius' and I was utterly hooked; he's been my favourite fantasist ever since. You can keep your Tolkeins and your Martins; they have their place and I like their stuff, but the true phantasmagoria has a different power and one that speaks more clearly to me.

Despite never being sure how to pronounce his name (Bor-jez or Bor-hez?), I've loved Borges' work ever since stumbling across 'The Library of Babel' in some anthology or other back in my university days. Then I read 'Tlon, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius' and I was utterly hooked; he's been my favourite fantasist ever since. You can keep your Tolkeins and your Martins; they have their place and I like their stuff, but the true phantasmagoria has a different power and one that speaks more clearly to me.

Borges' work has the resonance of myth, dream and parable. His stories pick a single concept, like an infinite library, a fictional reality replacing a real one or a writer attempting to recreate a classic novel from scratch, and play with it like a beautiful toy. A Borges piece doesn't try to imply that it's a snapshot of a wider world that could be further explored; each story is a thing onto itself, bound in a nutshell, a jewel that shines alone without any need to be socketed into an over-detailed crown. Even his ostensibly 'realistic' early work, like 'Man on Pink Corner', has this quality; a petty criminal is stabbed, and there's no need to work out where he came from or what happens after the event, because all that matters is the sadness of the event and the tango happening in the background.

To quote biographer Edwin Williamson: "His basic contention was that fiction did not depend on the illusion of reality; what mattered ultimately was an author's ability to generate 'poetic faith' in his reader." And that approach to storytelling, to work inside a tight set of conceptual bounds' and focus on wild fancy rather than prosaic underpinnings, is very much the way I come at stories, especially fantasy stories. I don't care much about how the story could have come about or how it could fit into a greater context; I just like to focus on the what and the why of what's happening now, in this narrative right here, and to go as far and fast into that idea as I can without stopping to get my bearings. That's very much the ethos of Hotel Flamingo, to name the most obvious example, and that's why getting called a 'skittish Borges' by one reviewer is pretty much the highpoint of my writing career.

Raymond Chandler

If Borges showed me where to go, it was Raymond Chandler – that prissy, irascible, homophobic, despicable genius – who showed me how to get there. When I first read The Big Sleep it was a thunderbolt, a revelation of a lean, muscular but also refined and intellectual prose style that could portray both action and pathos without dropping a beat.

If Borges showed me where to go, it was Raymond Chandler – that prissy, irascible, homophobic, despicable genius – who showed me how to get there. When I first read The Big Sleep it was a thunderbolt, a revelation of a lean, muscular but also refined and intellectual prose style that could portray both action and pathos without dropping a beat.

Chandler's work is unconcerned with fine detail, preferring to give readers short but incredibly rich cues that let them paint their own vision of his characters and their world. His punchy similes and metaphors do more in ten words than most writers could accomplish in three hundred. A description like "It was a blonde. A blonde to make a bishop kick a hole in a stained glass window" tells you everything you need to know about both the hot number being described and the attitude towards women on the part of the narrator. His work is finely crafted without being artificial, lyrical without being schmaltzly; his pulp thrillers gloss over the process of crime and punishment to reflect themes and questions of honour, courage, betrayal and the cost of doing the right thing.

Do I write like Chandler? Um, I'd like to say that I do, but I know I can't measure up to that standard. I try my damnedest to write to the same general principles, though – to suggest rather than describe, to sum things up with a core metaphor rather than explicit detail, to put the emotional meat of conflict in the centre of the plate and let the vegetables take care of themselves. The Obituarist is my own attempt to come at Chandler's sort of story and character, not as pastiche but through genuine inspiration, even if the trappings are totally different and the gender politics are a whole lot more enlightened. But I think you can see that ethos in the rest of my work, too – and it's fun to apply that approach to other genres than crime, too. We could do with a lot more Chandler in our fantasy.

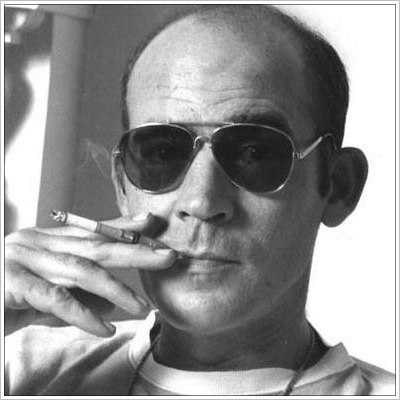

Hunter S. Thompson

I like to swear.

I like to swear.

Okay, that's the obvious thing everyone takes from Thompson, along with stories of ludicrous drug-fuelled rampages. It's the easy hook and it's a powerful one. Thompson wasn't the first or even the best author to throw out that concept of the writer-as-celebrity, as a larger-than-life figure who didn't just write stories but lived them and shaped them and brought them into being with the force of his own genius and excess – but he's the one who got his claws into me, who made me consider the need not just to come up with stories but to wrestle them into submission. And yeah, I gave the life of heroic excess the old college try for a few years, but let it go before my knees, kidneys and neurons suffered too much permanent damage.