Patrick O'Duffy's Blog, page 21

August 21, 2012

Two the hard way

I got paid last week, and as is my wont I went to see the good fellows at All-Star Comics to drop some dinero on a few trades. Most of them are things to discuss another time – once the series is finished I will do a mega-post about how freaking great Locke & Key is – but two of them are tales of men in tights fighting bad guys, as per this month’s theme, and I’d like to quickly talk about them and why you should read them.

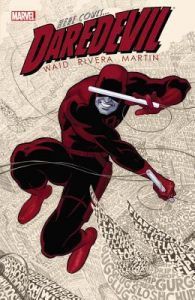

Exhibit A is the first collection of Mark Waid’s run on Daredevil (which is just called Daredevil Vol 1, rather confusingly). Waid took home three Eisners this year, two for this series, and it’s easy to see why because this book is awesome. After years – hell, decades – of being a tormented, tortured character, Waid brings Daredevil back to his swashbuckling superhero roots, portraying Daredevil with a smile on his lips as he pits himself against four-colour villains and some of Marvel’s old-school villainous groups. It’s a major swerve, but it works because it’s grounded in the story, with Matt Murdock deliberately pushing away his sad past before it breaks him – a move that foreshadows consequences and problems ahead.

For all that the writing is strong – and it is, it’s some of Waid’s best – the artwork from Paolo Rivera and Marcos Martin steals your attention away on every page. But again, this plays into the narrative, putting a major focus on Daredevil’s enhanced senses to communicate how he perceives the world, a world of soundscapes and textures and villains/adventures that draw upon Daredevil’s senses as well as his ninja skills. Both artists work wonders with open, energetic whites, snapshot frames and multiple panel, evoking artists like Mazzuchelli and Ditko while having their own unique take on things. It’s glorious, beautiful stuff with a deliberate lightness that never feels trivial.

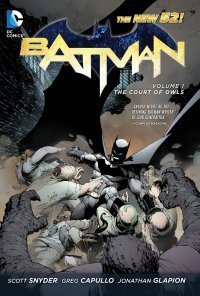

Over at DC, we have Batman: The Court of Owls, the first volume of Scott Snyder’s side of the post-reboot Bat-verse. This collection (I got the HC, but the trade is due soonish) puts Bruce Wayne back into the title role as Gotham’s guardian, a role he’s comfortable and confident in, especially as he’s backed up by new gadgets and techniques. But his confidence begins to erode in hints that an old urban legend – the Court of Owls, Gotham’s secret rulers – are real and coming for him. Snyder has a horror writer’s temperament and imagination, which bleeds through in the tense, terrifying second half of this book, as all of Batman’s strength and courage mean nothing in the face of a more mysterious, more ruthless enemy that puts him through mental and physical hell, leading up to a ball-tearer cliffhanger.

Over at DC, we have Batman: The Court of Owls, the first volume of Scott Snyder’s side of the post-reboot Bat-verse. This collection (I got the HC, but the trade is due soonish) puts Bruce Wayne back into the title role as Gotham’s guardian, a role he’s comfortable and confident in, especially as he’s backed up by new gadgets and techniques. But his confidence begins to erode in hints that an old urban legend – the Court of Owls, Gotham’s secret rulers – are real and coming for him. Snyder has a horror writer’s temperament and imagination, which bleeds through in the tense, terrifying second half of this book, as all of Batman’s strength and courage mean nothing in the face of a more mysterious, more ruthless enemy that puts him through mental and physical hell, leading up to a ball-tearer cliffhanger.

Snyder is backed up by artist Greg Capullo, who’s come a long way since mimicking Todd McFarlane on Spawn. There’s a exaggerated cartoonishness to a lot of Capullo’s work, but it’s powerfully juxtaposed against brooding shadows, bloody action and moments of terrifying grotesquerie. There are multiple flashbacks, perceptual shifts and hallucinatory episodes in this story, and Capullo seamlessly shifts his style and storytelling to fit each time. If he has a flaw, it’s that his characters’ faces are a little too similar – it’s sometimes hard to tell Bruce Wayne from Dick Grayson when they’re talking – but his body shapes and language make up for it to provide a strong differentiation. Plus, his work in the second half is scary as hell.

–

These are two excellent superhero books that kick off ongoing directions and stories for two terrific characters. If I had to pick one over the other… well, damn me for a traitor and take away my Bat-card, but it would have to be Daredevil. The sheer energy and liveliness of this book, along with its intelligence and kinetic artwork, make it an absolute delight. Court of Owls is good, but at times the focus on atmosphere and suspense take away from the forward motion of the narrative; Snyder spends a bit too much time building up Gotham as a character in the first half and not enough on having Batman, well, do stuff. On top of that, Daredevil has something I’m really missing in modern superhero comics – a hero who spends his time actively looking for people in trouble and then helping them. Batman does a lot less of that, instead reacting to threats directed at him rather than protecting innocents. I like heroes who are heroic; the DC Universe is kind of lacking that at the moment.

But that said, I enjoyed the hell out of both books, and if you’re any kind of fan of either character, or of superheroes in general, you should definitely give them a read.

August 19, 2012

Faster than a speeding narrative

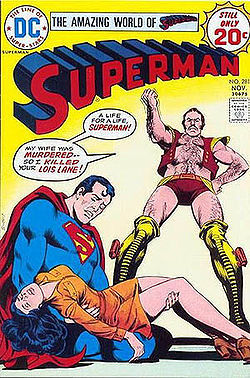

Lately I’ve been thinking a lot about Superman, and specifically thinking about how to write Superman stories.

Which, let me be clear, is not something I tend to do very often. I am Batman-man, after all, and while I’ve always been perfectly happy that Superman exists I’ve rarely been all that interested in reading about him. Good character, but not my favourite.

[image error]

But the last few years have seen Superman appear in many stories that get the character very wrong, and these things irritate me when I read them. Worse, those wrongheaded approaches get enshrined into continuity as ‘definitive’ stories and interpretations, and the stories that follow take their cues from these flawed sources.

And now we have a belligerent, ‘edgy’ Superman who is alienated from humanity, quick to lash out in anger and willing to dismember and decapitate his enemies. Yes, that actually happened in the new Justice League title, because what we’d always wanted to see was the world’s greatest hero tear aliens into bloody shreds. Kids love it!

Everything about this is terrible. EVERYTHING.

So I feel the urge to pontificate on how to write Superman. Which is not difficult, despite what people say – hell, it’s so simple that even a schmuck who has no comics writing experience whatsoever can see it. Because there is an elemental purity to Superman, the first and most important superhero, and that purity shines through like yellow sunlight through green fog.

Many of the changes seem to come from the oft-repeated ‘conventional wisdom’ that Superman is a hard character to write, or to relate to, for two reasons:

His enormous physical power makes it difficult to challenge him

His morality is simplistic and makes him emotionally uninteresting

The interesting thing about these arguments is that they are both stupid – or, more precisely, both backwards. They position the two greatest opportunities in writing the character as problems. They are Bizarro reasons that am make perfect sense me am love eating ground glass.

Here’s the thing about ‘challenging’ characters – that’s not how writing a story works. Writers don’t ‘challenge’ characters, because the setup and the outcome of the story (or scene) are determined by the writer in the first place. There’s no challenge, there’s no uncertainty, there’s no rolling dice to see if the hero or villain win this month. Instead, you need to approach things in terms of conflict.

What are the stakes? What are the conditions? What does the character want? What can/will they do to achieve it? What do they need to overcome? What are the consequences of success and/or failure? These are the fundamental questions a writer needs to consider, and they are the questions that shape stories – and that determine what kind of stories work for a character.

So when someone talks about Superman being ‘too powerful’, that speaks to a problem with the stakes and conditions, not the character itself. A story about Superman catching a car thief isn’t going to work because the stakes and the consequences don’t match the character, not because he’s ‘too powerful’. And anyway, we’ve seen that story before, right?

Instead of a problem, think of Superman’s abilities as an opportunity. Superman’s physical power does not exist to let him overcome conflicts, it exists to allow him to engage in conflicts – the more amazing and over-the-top the better. His power level allows you to open up immense conceptual space and come up with magnificently impossible situations. Suns should be exploding, continents should be liquefying dimensions should be tearing asunder. You have a chance to make up something amazing when you write Superman – do that, rather than, I dunno, have him walk slowly across America while lecturing poor people about how they shouldn’t commit crimes.

The other thing about going balls-out in the imagination stakes is that it means creating antagonists who can also operate on that level. Again, this is something some writers see as a constraint (they really wanted to make that car thief the bad guy) and I see as an opportunity, because it means the power levels cancel out and put the focus on personality. When that playing field is leavened – or, more correctly, equally heightened – what carries the day is not physical power but courage, determination and humanity. Superman doesn’t win because he is strong; he wins because he is brave, kind, inspirational and selfless. He wins because of that simplistic morality that is the other major complaint about the character, because the heart is the most powerful muscle of all.

And here’s the thing about ‘simplistic morality’ – fuck your cynicism, human goodness is real.

Yes, we are flawed, but we can work to overcome those flaws, and we do so every day. I see people striving to help others every day, in whatever way they can – and for most of us those are small ways, sure, but we still try. We can be terrible to each other, but we don’t have to be. And in Superman – in the lightning that Siegel and Shuster captured in 1938 – we can imagine what simple human goodness could do if given the ability to act. Superman does not refute the notion that power corrupts; he refutes the notion that power must corrupt.

Some people think that’s old-fashioned. I think it’s beautiful.

Certainly there is room for that moral strength to be tested – that, in the end, is the most exciting part of any conflict involving Superman, because exploding suns are all well and good but we need something human to connect to. The point is, though, that there’s a difference between it being questioned and being subverted or mocked; between it being a source of conflict or a source of failure. Stories where Superman wonders whether torture can be justified (the animated feature Superman vs the Elite), where Jonathan Kent hires a branding consultant to design the S-shield (Superman: Earth One) or where his power alienates him from humanity and makes him feel superior (Kill Bill, of all things) utterly miss the point of the character. Superman gives us something utterly human to aspire to; he tells us that goodness can come from our genes, our upbringing or our innate character. That humanity is not something to be overcome, despite what Nietzsche said.

–

Alright, enough of my ranting and italics. Where does this get us?

Well, if we work from these principles, we can see that Superman stories should embrace the impossible, putting him at the start into situations no normal person could survive or perhaps even understand. He’s not blase or jaded by the situation, but nor is he cowed. His powers let him engage with those impossible situations, while his moral strength allows him to overcome the conflict facing him – the alchemical wedding of Super and Man.

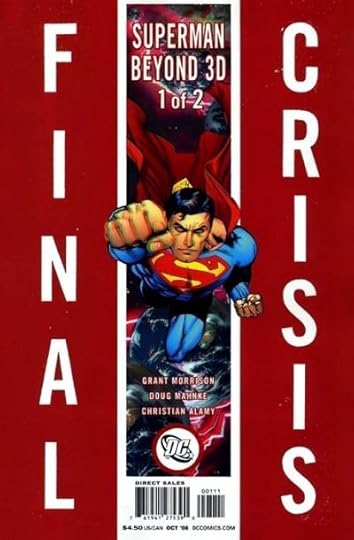

For my money, the perfect Superman story that illustrates all of this is not All-Star Superman, although that is one of the finest Superman stories ever told; it gets everything right, but puts too much of its focus on other characters and situations. Instead, I’d like to nominate another Grant Morrison piece, Superman Beyond, a tie-in to the unfairly maligned Final Crisis.

For my money, the perfect Superman story that illustrates all of this is not All-Star Superman, although that is one of the finest Superman stories ever told; it gets everything right, but puts too much of its focus on other characters and situations. Instead, I’d like to nominate another Grant Morrison piece, Superman Beyond, a tie-in to the unfairly maligned Final Crisis.

In it, Superman is recruited by the interdimensional Monitors of Nil to battle a threat that could end the entire multiverse. But the Monitors’ bleedship crashes in Limbo, a wasteland between realities populated by forgotten superheroes, a place where stories go to die. When Mandrakk, the Dark Monitor, comes to tear Limbo apart and destroy all realities, Superman rallies the forgotten heroes to fight back while he travels outside reality to the Monitors’ home. There he takes control of a giant thought-robot to fight Mandrakk, unleashing the conceptual power of his own story to overcome the metatextual erasure of reality, finally casting the vampire Monitor into the Overvoid before flying back to his own reality with a single drop of infinite energy in his mouth that he uses to save Lois Lane’s life.

That probably all sounds a bit crazy put like that, and it must be said that coherency is not a hallmark of Final Crisis, but the majestic inventiveness and scale of the story make it wonderful. It’s a story where Superman must battle threats not just to humanity or one universe but to the very concept of universes, where he has to accept the idea that his life and everything he knows is on some level fictional but still worth fighting for, where he needs to place faith in alternate universe versions of himself (even in the evil one), and where in the end he is motivated to give it everything he has by his love for his wife.

Also, parts of the story were in 3D, special glasses and all.

Fuck. Yeah.

That’s how you write Superman,

–

Look, I’ve been talking in the specific about Superman here, but in the end this all applies to any powerful or competent character. Actually, strike that – it applies to any character, at least one interesting enough to write about. Because it’s always important to ask the right questions when writing about conflicts, and it’s always important to let the character’s personality be involved in how that conflict plays out. It’s just that it’s easier to expound at length (great, great length) on those points when I have a blue-and-red example to attach to them.

So take three axioms from this:

Any character trait, negative or positive, can be used to shape the parameters of a conflict.

Any character trait, negative or positive, can be used to shape the outcome of a conflict.

You can (and probably should) use completely different traits to shape parameters and outcome.

And those apply to heat vision, intellect, juggling skill or just particularly tight pants.

Or indeed no pants. Let’s see Superman fight that.

August 16, 2012

Legacy in blue

Legacy.

It’s a concept that used to be one of the pillars of the DC Universe – that a mantle of heroic action would be passed from one character to another. The Flash and Green Lantern of World War II inspired the Flash and Green Lantern of the silver age, who were then replaced by the Flash and Green Lantern of the modern age, with the promise of future heroes assuming that title as well… it was a thematic mainstay that propelled dozens of characters and hundreds of stories.

Well, like most good things in the DCU, the theme of legacy was abandoned in the DC Reboot, in which superheroes have only been around for five years, there were no heroes in WWII (there’s a wonderful sentence to contemplate) and characters operate without foundations or any kind of respect for what has gone before. Which is a goddamn shame.

But I’m not here tonight to whinge about the DC Reboot – that comes later in the month. Instead, I want to talk about one of the last, best examples of the treatment of that theme from DC, which also happens to be a fantastic, funny, smart and action-packed comic book.

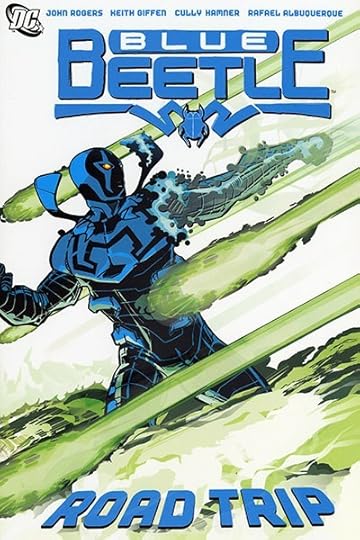

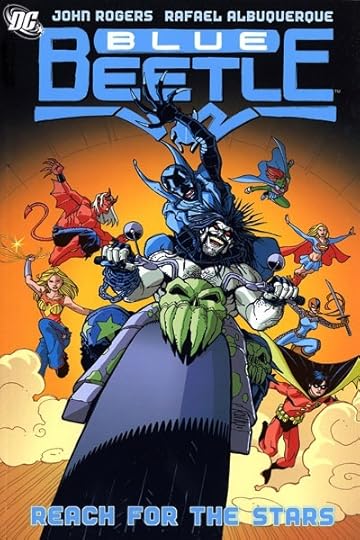

And that comic is Blue Beetle.

So first, some backstory. The original Blue Beetle was a Golden Age character who bounced through a few iterations and publishers. Eventually he was bought and revamped in the 1960s by Charlton Comics as Dan Garrett, an archaeologist who discovered a magical scarab amulet that gave him superpowers (strength, flight, energy blasts, similar generic things). When that version proved unpopular, Charlton didn’t reinvent him, they replaced him – Garret died and passed the scarab on to his former student, inventor Ted Kord. Kord became the new Blue Beetle, but a very different character; he couldn’t make the scarab work, so instead fought crime with gadgets, inventions and intelligence.

Fast forward about 15 years and DC Comics bought the rights to the Charlton stable of characters, where Garrett became a minor WWII superhero and Ted Kord the modern Blue Beetle – keeping the legacy concept going, but stretching out the ages between the characters to fit DC’s timeline. During the late 80s and early 90s Kord was a major DC character and a mainstay of the Justice League, but eventually faded from the limelight to become another perennial C-list character in the background of crossovers.

And then came 2005′s mega-event Infinite Crisis, during which Kord uncovered a conspiracy and was murdered – but not before leaving Garrett’s scarab with the wizard Shazam, who then lost it in an explosion. It fell to Earth in El Paso, Texas, and was found by a teenage called Jaime Reyes, who used it to help Batman defeat… okay, look, this is all a really long story that is often not very fun, so let’s just skip the details and move onto the comic, alright?

So teenage Jaime becomes the new Blue Beetle, as the scarab responds to him by forming into a set of high-tech armour covered in bizarre weapons and manned by an semi-incomprehensible telepathic AI. People start chasing him, he gets into trouble, he tries to find out what’s going on… all of this has the potential to be a decent setup for a decent, unremarkable comic series.

Except that Jaime used Google to find out about Ted Kord.

And except that Blue Beetle was written by John Rogers, scriptwriter, producer and TV showrunner for the show Leverage (which I still haven’t seen but I hear is well worth watching). In his first comics work (he went on to write Dungeons and Dragons, which I’ve raved about before), Rogers stepped up to write like an experienced master of the form, creating a series packed with memorable, likeable characters, punchy stories and exciting revelations (none of which I’ll spoil here).

He was helped in this by artist Cully Hamner, whose blocky, cartoony style I’ve always liked; his lines are blocky and dark but fun and open at the same time, and his design of the Beetle-armour is a terrific departure from the usual metal-and-geegaws style of super-battlesuits. After he left, new artist Rafael Albuquerque also bought a cartoony style, but one with a lighter, scratchier line, less over-the-top and more expressive; it took me a little while to warm to it, but now I think Albuquerque is one of the best artists in comics, and Blue Beetle shows him constantly growing in skill.

But I’m not so much here to review Blue Beetle (here’s a review – it’s great) as to talk about the theme of legacy, which Rogers used as the spine of the series. As I said, Jaime read up on the previous Blue Beetle, trying to understand the connection to his scarab, and what he found inspired him – that Ted Kord, a man with no powers, could stand up for what was right and make a difference. Then he made contact with Dan Garrett’s granddaughter, who gave him more data on the scarab – and on Garrett’s time as a superhero, and the difference he made in the world. He realised that there is a legacy attached to the Blue Beetle, not just the scarab but the name itself, and he decided that he wanted to be part of that.

And a key element, I think, is that Jaime never meets either of the two previous Blue Beetles; they’re both dead before he finds the scarab. Nonetheless, he sees the value in what they did and what they strived for, he sees role models in them – he chooses to be part of their legacy, rather than having that legacy thrust upon him or just making his own way. And as Rogers’ overarching storyline continues, Jaime tries to embody the strength of Garrett and the intelligence of Kord, to take guidance from them while making his own way. To become something more than just a costume or a right cross, but a legend that can live on.

[image error]

Rogers left the series after 24 issues (collected in the first 4 trades), having wrapped up his story. There was an attempt to keep the series going with writer Matthew Sturges, but it didn’t click – his issues weren’t terrible or anything, but they lacked the spark (and the cohesive thematic underpinnings) of Rogers’ – and the series ended after one last storyline.

Blue Beetle continued to play a part in the DCU, joining the Teen Titans, hanging out with Booster Gold and appearing on The Brave and the Bold cartoon, and then the Reboot changed everything. There’s a new Blue Beetle series, but it’s heavy on the stereotypes and pointless fight scenes, light on the legacy (or any other kind of theme) and it’s all a bit sad and pointless now.

But there are four great trades (and one adequate one) of the original series, and they are a thing of joy, and they tell a great story with a great ending. And stories that end well are usually the best kind.

[image error]

One of the powerful, story-generating tensions in the superhero genre is the clash between individualism and collectivism – it’s a genre where a single being can advance above all others and change the world but also seek to serve others and be part of something greater than themselves. The theme of legacy is one of the strongest ways to explore that tension and make a supers story more than just dudes in tights thumping each other. And Blue Beetle was a hell of a lot more than that.

You should read it. You should love it. It’s that good.

August 13, 2012

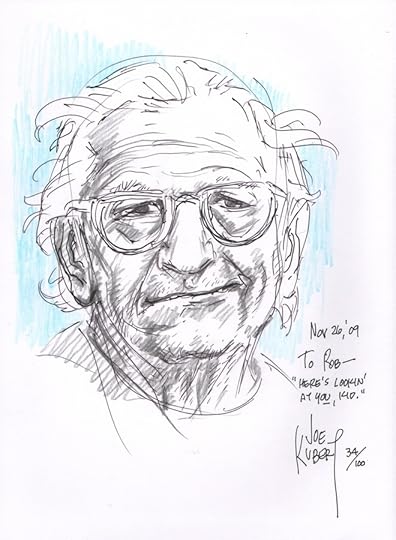

RIP Joe Kubert, 1926-2012

As a comics reader, I have never considered myself a fan of Joe Kubert.

That would be like considering myself a fan of oxygen.

There are things in this world too vital and omnipresent to not need, and as a comics reader the towering, artform-shaping talent of Joe Kubert is one of them. It would be impossible to contemplate a world without him.

But now we have to, because Joe Kubert passed away this morning, age 85, and now we have to learn to live without breathing.

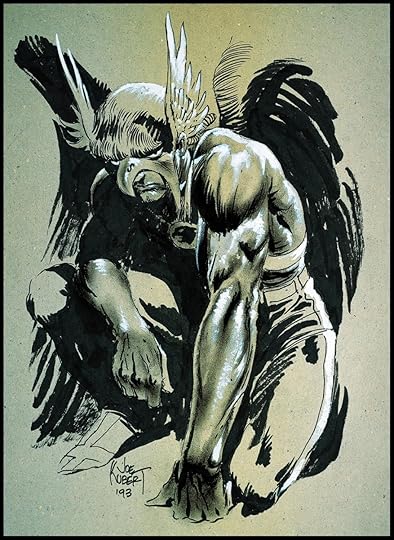

Kubert was an incredible artist whose skills and storytelling power helped define comics since the 1940s. He’ll always be best known for his men of action, soldiers and superheroes and warriors – Hawkman, Sgt Rock, Tarzan, Ragman, Tor. He breathed life into them and made them both mythic and very human. Kubert’s characters had grime, stubble, texture, solidity; the world left its traces on them as they marked it in turn. They could fly with impossible grace or face down vicious enemies to save the day, but they would still need a shower afterwards to wash the sweat off their bodies and the blood off their knuckles.

Kubert was more than just an artist, of course; he was a writer too, one who wrote powerful, tense and often sad stories of adventure and conflict. War stories were his primary oeuvre, but not hollow, jingoistic tales; Kubert wrote about the costs of warfare, about soldiers sacrificing themselves to save others and how stupidity and bad luck could make that sacrifice a fool’s errand. Sgt Joe Rock of Easy Company, perhaps Kubert’s most enduring creation, was a soldier’s soldier, a good man prepared to endure bad consequences for the sake of his men and for what was right. There was nothing easy in Rock or in his stories; they were thrilling but sobering, and no-one came away from them thinking war was anything but hell.

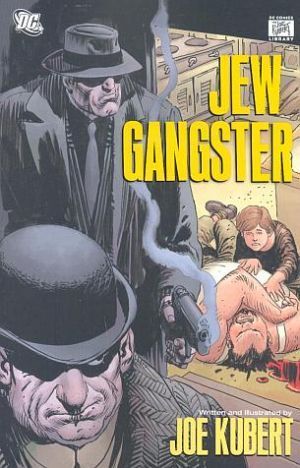

But Kubert was never bound by a single genre. He continued to develop his craft and skills into his 80s, and later realist and semi-autobiographical works like Jew Gangster, Yossel and Fax From Sarajevo were some of his greatest and most thoughtful.

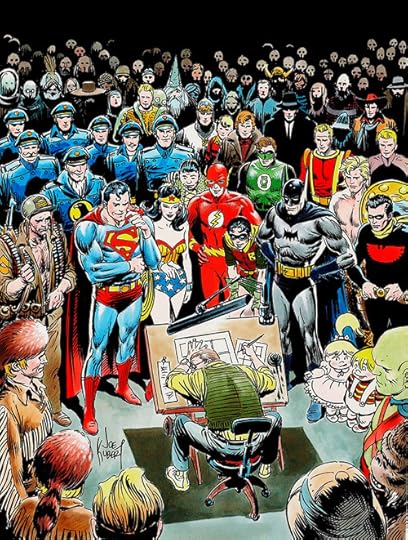

And again, Kubert was more than an artist, more than a writer; he was a teacher too. In the 1970s he established the Kubert School, America’s best-known and best-respected school for comics artists. As a comics reader, I’ve always looked for word of the Kubert School in an artist’s bio. It wouldn’t tell me anything about their artistic style, but it was a rock-solid guarantee that they understood the craft of storytelling, the nuts and bolts of letting images carry a narrative forward one panel at a time. In an era of splash pages, pin-ups and characters without feet, that grounding in craft and narrative meant everything for me – and all of that led back to Joe Kubert.

He never retired. He never stopped writing, drawing, learning, teaching.

…and finally, though I never met him, everyone says he was a hell of a nice guy too.

There are many creative talents in the comics field, writers and artists past and present with incredible skill and inventiveness who have published fantastic works. But there are few transformative talents, creators who utterly change the face of the artform with their work. Eisner was one, Kirby another, and so was Joe Kubert.

We live in the paper universes they defined. And those universes are left flatter, colder and duller than they were yesterday.

Rest in peace, Joe. Thank you for everything.

August 11, 2012

Like unto a thing of iron

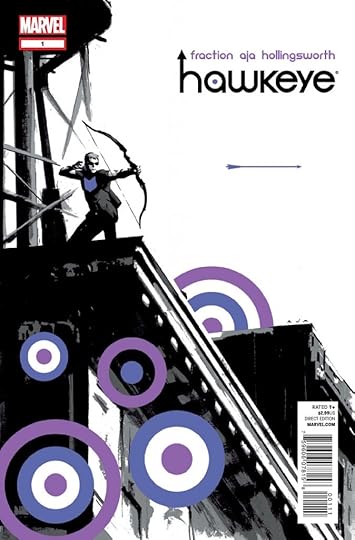

There’s a lot of buzz around right now about Hawkeye, the new Marvel series about the ordinary-guy member of the Avengers. I haven’t read it yet, but I’m very interested in what I hear and I’m certain to buy it when it’s out in trade paperback form.

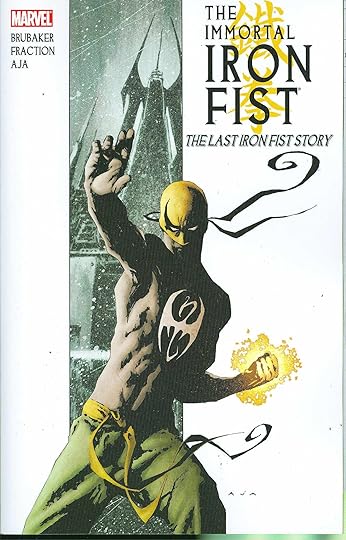

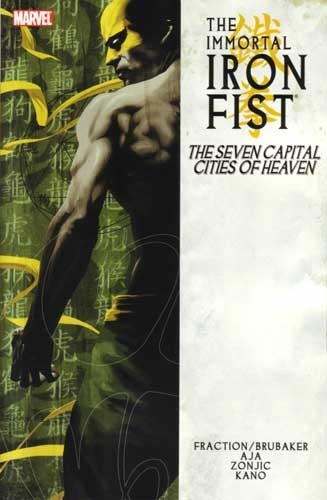

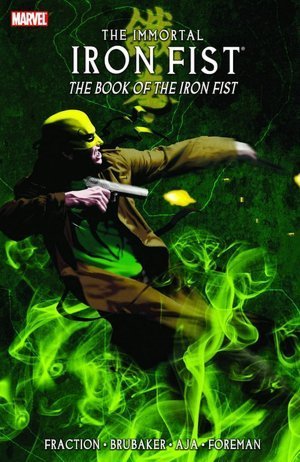

One reason I’m so certain about that is that I’ve read the previous series from the team of Matt Fraction (artist) and David Aja (artist) – 2007′s The Immortal Iron Fist, which remains one of my favourite superhero works of the last ten years. It’s a book for anyone who loves pulp adventure, martial arts and superheroics, and if you haven’t read it by now then I’m going to tell you exactly why you should.

Iron Fist is a Marvel superhero created in the 1970s, a time when Marvel were taking more risks with their characters and trying to tie burgeoning genres like science fiction, blacksploitation and martial arts into their superhero titles. Enter Danny Rand, the Iron Fist (named after a technique in a kung-fu movie Roy Thomas watched) – a young American trained in martial arts in the mystical city of K’un-L’un. Becoming the city’s champion after defeating a dragon (and gaining the power of its chi), Rand comes to New York to confront his father’s killer; eventually he inherits his father’s fortune and becomes a billionaire superhero for hire. Or, more accurately, a B-list character that wandered in and out of back-up features and supporting appearances, along with partner and friend Luke Cage/Power Man, for the next 30 years.

But then Brian Michael Bendis became Marvel’s head writing honcho, and he propelled Luke Cage into a major role with the Avengers. And with like in the limelight, the chance to reinvigorate Iron Fist opened up for a new creative team – Fraction, Aja and co-writer Ed Brubaker.

When approaching an established character, a new team has three main duties – keep what works, throw out what doesn’t, bring in something new. And Immortal Iron Fist does all three. Danny Rand feels penned in by his duties running Rand Industries, preferring to play superhero with his buddy Luke, until someone new smashes into his life – grizzled, pistol-packing pulp adventurer Orson Randall, the Iron Fist of the 1920s! Thrown into action against Hydra, Danny learns that he’s only the most recent champion of K’un-L’un, heir to a legacy of heroes from every era (and pulp adventure genre) – and that he must now fight in a cross-dimensional tournament against other martial arts warriors, the other Immortal Weapons of the Seven Capital Cities of Heaven.

In order to save K’un-L’un – and himself – Danny has to learn entirely new ways to use his chi powers, discover more of the legacy of the Iron Fist, uncover the secret intrigues of the Capital Cities, and beat the crap out of a whole lot of Hydra badguys in an epic storyline that lasts for more than a year of issues.

One reason why the series is so cool is that Brubaker and Fraction said ‘well, this character comes from a different genre, so let’s explore that genre – and what the hell, a bunch of other genres as well, just because it would rock.’ So Immortal Iron Fist largely eschews superhero fights and gets back into crazy kung-fu action against dozens of mooks and evil martial artists. Then the storyline brings in 1920s two-gun pulp heroes, then steam-powered Victorian superscience, high wuxia fantasy, war action, horror, more, more, more! Pretty much every old-school pulp genre gets a look in at some point, with I guess the exception of Buck Rogers-style sci-fi; hell, one issue has Frankenstein and gun-toting Western saloon gals. It’s a kitchen-sink act that could collapse at any point if not supported by a solid foundation of character, a playfully-intelligent energy and the constant genre strand of balls-out kung-fu fantasy.

Danny Rand emerges as an engaging and likeable character, someone called to do the right thing but who still has fun doing it, trying to find a balance between the traditions of K’un-L’un and his streak of American independence – an everyman who just happens to be a kung-fu billionaire with a blacksploitation cyborg girlfriend. Brubaker and Fraction do virtuoso work here, keeping the energy and tension high, exploring their expanded world with light exposition and knowing when to pull back and let the art do the work.

So let’s talk about the art. David Aja leaves after 9 issues, but creates a style and tone that shapes the artists that follow. Aja’s work is gritty without being grungy, with realistic body shapes and movements captured by a soft pencil line and hard black shadows. It’s a complete break from the more open, over-the-top depictions of Iron Fist in the 1990s, and reminiscent of artists like Dave Mazzucchelli or Michael Lark. His breakthrough technique is to zoom in on elements of the action with pop-out panels and circles, showcasing a specific kick, flip or facial expression, like photographs that capture instants and are then scattered across a table.

After he leaves the series a variety of artists carry the torch, most notably Travel Foreman, whose scratchy, distorted pencils bring a touch of grotesquerie and continue to separate the series from traditional superheroics. Other artists are more traditionally four-colour, which isn’t bad but does dilute the visual identity. On the other hand, there are also guest pencils from legends like Russ Heath and Dan Brereton, which are not exactly bad things, and Aja does come back a few times to contribute here and there.

(But we do lose those striking covers with their wonderful use of whitespace. That’s a shame.)

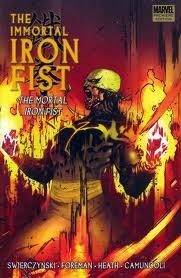

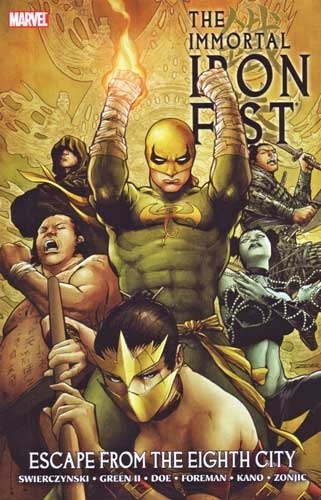

Brubaker and Fraction leave after 16 issues, which take up the first three trade paperbacks. Their successor is crime writer Duane Swierczynski, backed up by Foreman and a number of other artists. His run over the next year isn’t as distinctive or energetic as what came before but is still worth reading. It largely leaves behind the pulp genre play to focus on martial arts fantasy, as Danny battles a creature that preys upon Iron Fists and descends with the rest of the Immortal Weapons into the terrible Eighth City to fight demons and monsters.

Still, the series ended due to low sales, as do most Marvel comics that aren’t about Avengers or X-Men; there was one last mini-series about the various Immortal Weapons, which was fun but nothing spectacular, and it left Iron Fist and his supporting cast with a slightly bigger presence in the Marvel Universe. Which is a bonus.

[image error]

Five years after Immortal Iron Fist, Fraction has risen as one of Marvel’s big-name writers, with a reputation for unconventional story ideas and a willingness to look outside superheroes for tone and voice. The seeds of that are here, in the adventures of Danny Rand, Orson Randall and all the other Iron Fists past and future – adventures that brim with ideas, with energy and with a joyous love of the pulp genres.

It’s a really, really fun comic. You should buy the trades (or the omnibus collections) and read the fuck out of them.

August 10, 2012

Fuck yeah Lego

As an old person, I occasionally hear grumblings that Lego used to be cooler and more fun back in the day. Back when you have a box full of coloured and slightly tooth-pocked bricks you could assemble into anything, rather than sets with clearly defined and circumscribed outputs and special Girl-Lego that was redesigned to be pink and filled with genderfail.

To these protestations I can only make one response:

THEY HAVE BATMAN AND AVENGERS LEGO NOW AND YOUR ARGUMENT IS INVALID

There are video games, there are playsets, there are oversized figures, there are iPhone apps to make stop motion videos, there are Marvel and DC characters and you can put sirens on everyone’s heads.

And if I had travelled back in time and informed 10-year-old me that when he was 40 he could build Lego dioramas where Batman and Captain America teamed up to fight Loki and maybe some dinosaurs, he would have shit his pants in terror because OH FUCK TIME TRAVEL been totally fucking stoked.

Truly this is the best of all possible worlds. There has never been a better time to be a grown-ass man with badly screwed-up priorities.

(I’m not saying there’s not some weird bullshit Lego out there, and creating a ‘Lego Lifestyle’ brand for clothes and backpacks is kind of deeply fucked up, but I can forgive a lot in the name of Lego Iron Man, alright?)

August 7, 2012

Quick recommendation – DECOMPRESSED

Decompressed is a podcast produced by comics writer Kieron Gillen, perhaps best known for his Britpop-fantasy Phonogram and for suddenly graduating to writing a shitload of books for Marvel.

Decompressed is not about his work.

[image error]Instead it’s a comics-creation (mostly writing) craft blog where he interviews creators about their process, their decisions and the development of ideas into a specific single comic. Thus far he’s interviewed Jason Aaron (Wolverine and the X-Men), Kelly Sue deConnick (Captain Marvel), Tim Seeley & Mike Norton (Revival) and Matt Fraction and David Aja (Hawkeye, which I am seriously going to buy the fuck out of when it’s available as a trade).

And it’s really good stuff. Gillen asks the right questions in his soft English accent and I think a lot of that comes from the fact that he’s still relatively new to the industry. This is not an old hand talking about things he knows by rote; this is an excited newcomer still learning his craft asking ‘hey, why did you do that?’ and really wanting to know the answer. And his subjects love what they’re doing too, and the passion and the process ring out and ring true. It’s fucking fascinating.

And it’s really good stuff. Gillen asks the right questions in his soft English accent and I think a lot of that comes from the fact that he’s still relatively new to the industry. This is not an old hand talking about things he knows by rote; this is an excited newcomer still learning his craft asking ‘hey, why did you do that?’ and really wanting to know the answer. And his subjects love what they’re doing too, and the passion and the process ring out and ring true. It’s fucking fascinating.

If you’re not interested in how comics are conceived and written and drawn, this probably ain’t very interesting. But then again, if that were true you probably wouldn’t be sticking around on this blog in August. So go listen and check this fly shit out.

(PS – Decompressed isn’t the only thing on Gillen’s blog, so you may have to scroll a bit to find things. Hopefully he’ll start tagging them more effectively or something in the future.)

August 6, 2012

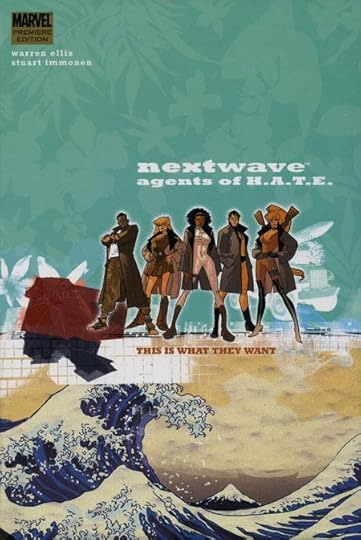

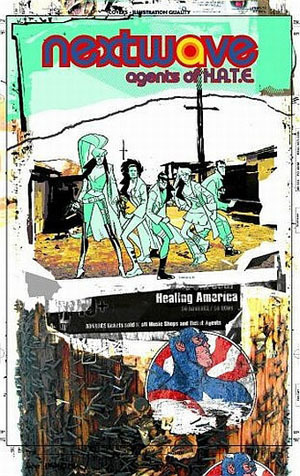

Superhero comics – NEXTWAVE

THIS IS NEXTWAVE

THIS IS VILLAINY

THIS IS NEXTWAVE KICKING VILLAINY IN THE MAN-PARTS

THIS IS THEIR THEME SONG

THESE ARE THE COVERS OF THE COLLECTIONS AND YES THERE ARE ONLY TWO (or a single collection of both)

It’s a twelve-issue pisstake tour of the Marvel Universe from Warren Ellis and Stuart Immonen.

If you don’t like it then we can’t be friends.

NEXTWAVE IS BROUGHT TO YOU BY THE POWER OF CAPSLOCK

HEALING AMERICA BY BEATING PEOPLE UP

[image error]

August 5, 2012

Now with 20% more amazement

I’m working on a big post about superhero writing, but I’m not going to post that tonight after all. Because we just saw Amazing Spider-Man and I feel like writing a spoiler-free review while there’s still time to see it in cinemas.

Which you should do. ‘Cos it’s kind of terrific.

The bulk of that terrific-ness can be chalked up to Andrew Garfield, who is fantastic as Peter Parker. He brings a cheeky and impulsive energy to all his scenes, even the ones where he’s miserable or injured, building up a portrait of a smart, likeable teen who’s nonetheless bottling up a wellspring of hurt. It’s a great departure from Tobey Maguire’s emo nebbish, and it spills naturally into the smart-mouthed momentum of Spider-Man when he puts on the suit.

Emma Stone’s Gwen Stacy is the other major pillar of the film, as much of it focuses on their relationship and how it quickly develops. Stone brings nearly the same energy and charm as Garfield, and there’s a real chemistry to the scenes between them that gives the story emotional weight without being too syrupy (despite the best efforts of the intrusive score/soundtrack, but I always bitch about that). I liked the fact that Gwen is mostly portrayed as smart, independent and capable, rather than someone who has to be protected; I also liked the way they retained a lot of her original 60s-mod fashions but modified them just enough to be current.

(As for the rest of the actors, casting Martin Sheen as Ben Parker was inspired, and he brings an entirely different but equally effective gravitas to the role that he did to Jed Bartlett in The West Wing. Sally Field is a surprising but very good choice for Aunt May, although it’s a smaller role, and Denis Leary is competent enough as Gwen’s police chief father.)

Visually and tonally the film is excellent – more grounded and less stylised than the Raimi trilogy, which tried to evoke the look of the original 1960s comics in a lot of ways. While Amazing doesn’t go Full Nolan in modernising things or abandoning established comics canon, it certainly tries to stake its own territory and make changes where it needs to, whether to Spider-Man’s origin or to the costume, which is pleasingly genuine in its look and construction, down to Peter using sunglasses lenses to make the eye-pieces. The physicality of Spider-Man, his webshooters and his movement is all much better than it was before, thanks to improved CGI that puts motion-capture tech onto real actors and stuntmen rather than ragdoll simulations.

If there’s a problem, it’s with the villain of the piece, Curt Connors/the Lizard. Not with Rhys Ifans’ acting, which is competent, or the look of the character, who is suitable huge and scaly and scary. But the film doesn’t introduce and escalate the threat of the Lizard as strongly as it should, because so much time is instead devoted to Peter’s development. The Lizard doesn’t show up until past the halfway mark and there’s a very abrupt curve from ‘fleeting appearance’ to ‘threatens all of New York’. A better approach might have been to develop the two characters and their storylines in tandem, letting them bounce off each other at multiple points in the movie rather than all at the end – that would have both improved the pacing (the middle part drags a little) and given more breathing room to showcase the Lizard’s plan and powers.

There are some other script and direction issues, but I don’t think I can explore them without getting specific and introducing spoilers. It’s not perfect, and the last third or so has most of the problems – but they’re not so problematic as to damage the movie or undercut the performances.

Was it too early to reboot the series? Did we really need another origin story? Well, maybe not, but the tonal differences in Amazing are strong enough that it would never have gelled with the Raimi series, and a new origin lays strong tracks for a new series that can forge its own, frankly superior identity. I don’t think a 4th Raimi film would have been as strong as this one, and we would have missed out on Garfield redefining Peter Parker and making him his own. If the price of developing a new direction and style is to sit through Spider-Man’s origin story again… well, it’s a pretty cool story, you know? Even if I have seen something like it before.

Was it too early to reboot the series? Did we really need another origin story? Well, maybe not, but the tonal differences in Amazing are strong enough that it would never have gelled with the Raimi series, and a new origin lays strong tracks for a new series that can forge its own, frankly superior identity. I don’t think a 4th Raimi film would have been as strong as this one, and we would have missed out on Garfield redefining Peter Parker and making him his own. If the price of developing a new direction and style is to sit through Spider-Man’s origin story again… well, it’s a pretty cool story, you know? Even if I have seen something like it before.

So yeah. Excellent movie and a great new inclusion into our superhero month; easily on a par with the other Marvel films of the current wave and better than some (ie Thor and Iron Man 2). Go see it before it finishes up in cinemas.

August 3, 2012

What is a superhero anyway?

So okay, if I’m gonna talk about superheroes all month, I should probably define my terms, right?

Superheroes are heroes. Who are just super.

…okay, that’s probably not enough.

The problem with the superhero genre is that it’s broad, and inclusive, and has very fuzzy boundaries. Well, I say ‘problem’, but to be honest it’s more like a positive feature because it means so much cool stuff can be included in there. But it gets confused when the genre reaches out to absorb other genres, such as pulp or ‘weird adventure’. Is Hellboy a superhero? Atomic Robo? The delightful Marineman, which you should check out? They’re all larger-than-life characters that have impossible adventures, but the label seems out of place. And I’ve seen attempts to classify characters like Indiana Jones and Perseus as superheroes, which is definitely stretching things too far.

The problem with the superhero genre is that it’s broad, and inclusive, and has very fuzzy boundaries. Well, I say ‘problem’, but to be honest it’s more like a positive feature because it means so much cool stuff can be included in there. But it gets confused when the genre reaches out to absorb other genres, such as pulp or ‘weird adventure’. Is Hellboy a superhero? Atomic Robo? The delightful Marineman, which you should check out? They’re all larger-than-life characters that have impossible adventures, but the label seems out of place. And I’ve seen attempts to classify characters like Indiana Jones and Perseus as superheroes, which is definitely stretching things too far.

At the same time, some readers want to exclude characters that to me are obviously superheroes. After The Avengers movie came out, I saw a lot of viewers say ‘Hawkeye and Black Widow aren’t superheroes’, which bamboozled me. They wear costumes and have codenames and possess special skills and they’re in the Avengers, so how can they not be superheroes? Usually the logic is ‘they don’t have superpowers’ – which is true, but that’s true of plenty of superheroes. I mean, by that logic Batman isn’t a superhero – and when I said that a few people agreed and then I had to just drink rubbing alcohol until the pain in my head went away.

So it’s not a cut-and-dried thing, and defining it would be hard work for a Saturday morning. So, rather than do the heavy lifting myself, I’m gonna quote someone else who already did the hard yards, comics journalist and Batmanologist Chris Sims at Comics Alliance:

In his very funny Super Villain Handbook – available now at finer bookstores everywhere — War Rocket Ajax’s Matt Wilson does a very nice job of defining what separates a super-villain from an everyday crook. The dividing line there was theatrics, and I think the same holds true for super-heroes. There has to be some kind of sense of grandeur to it.

I do think costumes and codenames are a definite aspect of it, although that doesn’t necessarily mean capes and tights. It means there needs to be a distinctive look for the character…

It’s also pretty crucial that they have abilities far beyond those of a normal person, even if they aren’t outright super-powers. Even characters like Batman and the Punisher, who “don’t have super-powers” are still defined by being way more determined and/or pissed off than any real person could ever sustain, even before you get to stuff like a lifetime of combat training and a family fortune.

And because they have those abilities, they need to be called on to do things that no one else could possibly do. The threats that they face should be on a level that’s somewhere beyond realistic, because the characters themselves have abilities that are beyond realistic…

To me, it’s very important that super-heroes lives up to that title; as obvious as it sounds, they need to be heroic. There has to be an aspect of their character where they’re putting some kind of moral or ideal above themselves, with an element of sacrifice or altruism as the motivation. And that ideal can be as vague or specific as it needs to be…

Thanks, Chris!

I think I’d add something else to that – that superheroes need to be unique but not one-of-a-kind. By that I mean than an individual superhero must have a unique identity, rather then being just Cyborg #17 and there are twenty others running around who are just the same. But at the same time, they shouldn’t be the only super-character in the world; there need to be other unique characters around for them to interact with, whether allies or enemies. I say this because stories about lone super-beings either pull away sharply from the genre, or pull it apart and deconstruct it. I’ve certainly never seen one that remained within the genre and had a central character that remained either ‘super’ or ‘heroic’ by the end.

So those are the points that make the definition for me. In the end, superheroes are like pornography (a quote you should feel free to take out of context): I know what they are when I see them. If a few of them are edge cases, that’s okay; genres have boundaries and some characters sit on or near them, and talking about those characters can be fun. We may not all be on the same page, but at least we’re hopefully all reading from the same book.

A book full of EXPLOSIONS AND SPANDEX.

Which, again, could be confused with porn.