Patrick O'Duffy's Blog, page 19

November 1, 2012

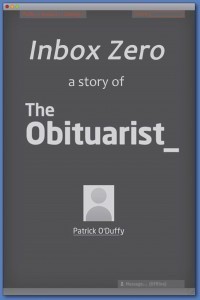

On the turps again

Every now and then I worry that I drink too much, and stay completely sober for a month or so to reassure myself that I’m not an alcoholic.

As such, I stayed dry for the month of October-just-passed, breaking the fast last night when we went to the pub with the Irish poet who’s been staying with us for the past five weeks and has now gone back to Scotland. I figured that was a special occasion worth celebrating, so we had beers and it was good. So very, very good.

More pertinently to this blog, though, is that I didn’t get a whole lot of writing done in October. I tinkered with Raven’s Blood without getting much accomplished, and wrote some blog posts that were probably much too long, and that’s about it. And look, I’m not saying that there’s 100% correlation/causation between me being sober and me not writing, but there’s definitely a link to some degree. Having a drink after work, or at the end of the day, lets me unwind a bit and unpack my creativity from the mental box I keep it in for safety when it’s not being used. Too many drinks and I just slap the keyboard with my forehead, true, but there’s a brief and glorious window in which the words leap from my fingers and the liquor leaps for my tonsils like an excited cheerleader on crystal meth. And without that creative impetus – I like to call it word fuel, because feeding my addiction sounds so clinical – I don’t tend to get into the writing mindset as often or as easily.

So that’s why I’m going to be drunk 24/7 from now on. It’s not for my sake. It’s for my art. It’s for YOU.

Honest.

–

Now, let’s go to the more interesting question, in which I ask you writers of all stripes: what’s your drink?

I am a beer man, and have been for a very long time. I love ales, especially steam ales and pale ales (but not India pale ales, which are too hoppy), and come winter I gravitate towards stouts. I know just enough about beer to know the difference between most types and to nod smugly and stroke my goatee while looking at the labels on various local microbrews and say hmm, hmm before wimping out and buying a sixpack of Mountain Goat.

I am a beer man, and have been for a very long time. I love ales, especially steam ales and pale ales (but not India pale ales, which are too hoppy), and come winter I gravitate towards stouts. I know just enough about beer to know the difference between most types and to nod smugly and stroke my goatee while looking at the labels on various local microbrews and say hmm, hmm before wimping out and buying a sixpack of Mountain Goat.

I am also a bourbon man, and again I know just enough that I love the good brands like Woodford Reserve, Wild Turkey Rare Breed and (on very rare and glorious occasions) Booker’s, but am still perfectly happy with a bottle of Jim Beam and some Coke for mixing. And now that I grow old, I have started to drink whisky (and indeed whiskey) like a gentleman, but I know sweet Fanny Adams about it and usually I just buy the el cheapo shit from Aldi and mix it with ginger ale.

I also make a decent mojito.

How about you? Beer? Red wine? Gin and tonic? Hot chocolate? Essence of toenail? The brown acid? What gets you relaxed and in the creative zone so that your genius can flow unto the page like liquid down your throat?

October 28, 2012

Five things I’ve learned about dialogue

I’m not good at dialogue.

There, I said it. Although not as well as other authors would.

Anyway, I’ve struggled with dialogue ever since I started writing, and because of that I keep writing it, because if I leave it alone I’ll never get better at it. I’m still not great with it, but I have learned something from my mistakes, and in the spirit of sharing, education and group hugging, I’ve got a list of five lessons here for your edification.

Lesson Zero, of course, is never to use the word ‘edification’ in your dialogue. Ahem.

Realistic dialogue isn’t interesting; interesting dialogue isn’t realistic

You know how normal people speak? We errm and ahh and mumble, we pause for breathe at inconvenient times, we repeat ourselves, we start every sentence with ‘Um, actually’, we repeat ourselves… all of these things are genuine and realistic ways of portraying human speech. And they are boring as shit to read. Worse than boring, they’re irritating; they’re like little clusters of birdshit clogging up the page and stopping the reader getting to the part of the dialogue that’s actually entertaining or that carries the story.

My big sin here was starting most of Kendall’s dialogue in The Obituarist with ‘Well,’. I had reasons – sometimes it showed that he’s thinking up what he says as he says it, sometimes it let me negate or undercut what someone else had said, but mostly I did it because that’s how people speak. Okay, that’s how I speak. Fortunately, my editor pulled me up on that and made me take it out, and the book is the stronger for it.

The dialogue that sticks in your memory or powerfully depicts character isn’t the realistic stuff, it’s the dialogue that you wish actual human beings would speak. No-one swears like Chuck Wendig’s Miriam Black or gibbers like Hunter S. Thompson’s Doctor Gonzo, but those characters (and other like them) have a voice that stays with the reader and draws them into the story. Their artificiality is engaging; they remind us that we’re reading fiction and are allowed to stretch our imaginations. Even realistic, character-based narratives benefit from interestingly unrealistic dialogue, because you can use the conceit of the voice as a counterpoint to the groundedness of the characters and story.

The dialogue that sticks in your memory or powerfully depicts character isn’t the realistic stuff, it’s the dialogue that you wish actual human beings would speak. No-one swears like Chuck Wendig’s Miriam Black or gibbers like Hunter S. Thompson’s Doctor Gonzo, but those characters (and other like them) have a voice that stays with the reader and draws them into the story. Their artificiality is engaging; they remind us that we’re reading fiction and are allowed to stretch our imaginations. Even realistic, character-based narratives benefit from interestingly unrealistic dialogue, because you can use the conceit of the voice as a counterpoint to the groundedness of the characters and story.

So cut out the umms and skip the tonal padding; crazy moon-talk puts bums on seats.

Small talk equals bore talk

The other thing real people do is talk about things that don’t matter that much – the weather, what we did on the weekend, the proud/shameful acts of Local Sports Team #7 and so on. This is normal and it serves a purpose; it’s a way of setting up a shared space in which we can then be comfortable talking about more important things. Small talk is a social safety net.

But small talk in a narrative needs to be bludgeoned to death and thrown in a lime pit; it’s boring, and worse than that it doesn’t move the plot along. I’m not saying every single word in your story needs to be 100% vital, but it should play some purpose for the reader; small talk only plays a purpose for the characters, and they don’t need to feel safe because they’re not real. I made this mistake in some of my early Hunter RPG writing, which was presented as in-character material like tape recordings. I used small talk and chit-chat to give context, but the material didn’t need it; again, my editor removed the worst excesses and set me straight.

Along these lines, the best point to come into a dialogue scene is after it’s started, not just after the chit-chat but just as/after someone said the most vital/heinous/meaningful thing. The best place to leave the scene is as soon as possible, just after the important stuff’s been said and people have started reacting to it and someone somewhere is going to throw a punch or have a baby or both at the same time. Jump right in, jump right out, hit it and split it – because you grab the reader at the height of their engagement in what’s happening and then transfer that energy to the next phase of the story. Make them do the work for once. Lazy buggers.

[image error]

Dialogue isn’t action

When you jump in late and out early from a dialogue scene, you bookend the talking with action – and this is important, because talking isn’t action. And I don’t just mean it’s not a fist fight or a car chase, I mean it’s not an avenue by which things happen; dialogue is not the place where things change. It often comes just before that change, of course, and might be the impetus for that change – but the change is still what characters do, not what they say, even in the most internally-focused story.

There are two parts to this lesson. The obvious one is not to make dialogue the resolution of a story or plotline; don’t end the scene with people just talking and then move on. That leaves the reader hanging and wondering what actually happens next, and not in a good way; it’s all windup and no payoff. Even if the aftermath of dialogue is just a person walking out of the room, that can still pack a punch; the words have an effect and the situation/person has changed. So long as the action is tethered to the dialogue in a meaningful way, the transition will be satisfying.

The second part is that, since dialogue isn’t action, you may want to include some action in the scene to keep the energy levels up. Two people sitting and talking can be riveting on stage, but in print it’s just line after line of he said/she said, and visual monotony can creep in. To avoid that, have characters move around and do things – drink wine, kick chairs, shoot ninjas, whatever. You can reinforce talk and action by having them be different aspects of the same thing; alternatively, you can have people do one thing while saying another, arguing about custody rights while operating killer drones on a cyber-battlefield. That contrast builds a dissonant tension if you do it right, and maybe lets you sneak in metaphorical parallels if you’re one of those writers who is smarter than me.

Dialogue is sorta kinda like action

Dialogue is sorta kinda like action

Okay, I lied. There is one way that dialogue is like action, and that’s pacing. Just as an action scene can catch the reader and propel them breathless through the chapter, so too can quick back-and-forth banter. Hell, you don’t even need that; any dialogue that’s reasonably snappy will speed readers through a scene, if only because there are fewer words on the page. That’s the mechanistic element that’s easy to forget; dialogue reads fast, and talking chews up pagecount more than description.

On the flip side, if you want to slow the pace down, you can do that with dialogue too. A slow, thoughtful conversation where characters speak in paragraphs rather than sentences can take up more mental space for the reader than anything else, because we’re less likely to skip through dialogue looking for pertinent information, which we’ll often do with description. That said, this is tricky, because slow, thoughtful conversations are often kind of boring. So maybe don’t do this too often; better to intersperse dialogue with description or (yet again) action for a speed-up-slow-down-push-me-pull-you rhythm.

This also means that if you write a book with no dialogue, minimal dialogue, or that gets away from the quotation mark style of speech to something more abstract – which is what I did with Hotel Flamingo – you lose a major pacing mechanism from your writer’s toolbox. If you’re a good writer, you can make do without it – but be aware of what you’re giving up before you start, lest you get halfway through and realise you need it after all.

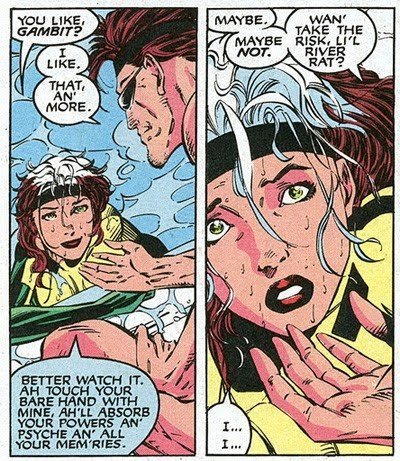

Give major characters a distinctive voice, but not an accent, because accents are bullshit

Some advice manuals say to give every character a distinct voice, but I say that’s not necessary. Sometimes it’s okay for a minor character to sound like another minor character, as long as they’re in separate scenes. Making everyone unique is a) hard, b) unnecessary, c) potentially overwhelming for the reader who has to juggle all these voices in their head.

But for major or recurring characters, it’s really good to give them a signature of some kind, a mannerism or style that tags them in the reader’s memory and reinforces personality. I used a few of these in The Obituarist, such as Samosa’s habit of saying ‘bro’ or Grayson’s snarky politeness, and I think I pulled those off pretty well. A specific inflection, a occasionally-used phrase, a tendency to inflect every statement like a question; little things say a lot and make them memorable.

A little goes a long way, mind you. D-Block’s vocal mannerisms in The Obituarist go too far, and looking back I wish I’d cut them down by about 50%. That would still have given him a unique voice, been less wearying to read, and might have said more about his character by implying that it was a deliberate affectation, rather than just being ‘street’.

Accents, though, are the work of Satan; they are the leavings of Mephistopheles’ slush pile. Unless you are Irvine Welsh and plan to your whole novel in dialect – and if you are Irvine Welsh, mate, thanks a lot for Trainspotting – then accents are just trying too fucking hard and making your character vomit unreadable chains of gibberletters onto the page that the reader has to decipher every damn time until eventually they give up and go back to the TV, where at least the accents might have subtitles.

Comics are so very, very bad for this. We’ve suffered through like thirty years of Chris Claremont sticking an indeterminate Southern accent on Rogue, whose drawl has stretched so far that it’s hard to tell whether she’s just a Foghorn Leghorn caricature of a real Mississippian or whether the poor girl has an acquired brain injury from all those times she got punched in the head by the Juggernaut.

Of course she hooked up with Gambit. It’s like duelling diphthongs down at the Crossroads.

Accents drown out the meaning and the tone of dialogue, overwhelming the flavour like rancid cheese oozing all over a subtle lemon sorbet. They’re cheap, they’re stupid, they’re distracting and they’re clumsy. And if you’re using them to communicate a character’s cultural or ethnic background, well, then they may even be kinda racist. Or not even kinda.

So don’t use ‘em, bro.

–

Folks, this has been a collection of five things I’ve learned as a reader and a writer. I hope you found them useful. If you did, please say so – if enough people enjoyed this I may do another set on a different topic in future. And if you disagree on any point, possibly because you are Chris Claremont – and if so, Chris, what was up with putting all the female X-characters in bondage outfits time after time? – then you should also leave a comment and say so.

We could start a dialogue OH SNAP YOU SEE WHAT I DID THERE

October 22, 2012

The long and short of Goodreads ads

As part of the early marketing of The Obituarist (still just $2.99, available for all devices, oh god please buy a copy), I bought a block of advertising on Goodreads. Well, the campaign has just wrapped up, so I thought it might be useful to look at the details of it all, pull apart my numbers and talk about whether it’s something other writers should consider.

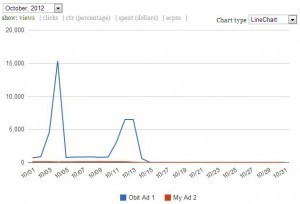

I hope you all like graphs.

Before we start, though – is there any need for me to explain what Goodreads is? Yes? No? Social media site where people list, rate and occasionally review the books they read? Occasional source of INSANE AMOUNTS OF FUCKWIT DRAMA over said reviews, which cause some writers to lose their shit because they didn’t get five stars? Yeah, we all know what it is, and if you don’t, well, it’s worth a look, especially if you’re into genre fiction or like reviews that are mostly series of animated GIFs and the phrase ‘so many feels’.

Anyhoo, GR offer a self-serve ad service – ‘self-serve’ meaning that you create it and they host it, which is fair enough. It’s not a complex ad; just a photo of the cover, a title, a link and a tweet’s worth of text (140 characters). Once it’s all submitted, you then pick a target audience (based on what they already read) and pick a cost-per-click – how much you pay Goodreads whenever someone spots the ad on the right-hand side of their page and clicks on it. That can be as little as 10 cents, and as high as no-seriously-just-hire-a-fucking-billboard – and the higher you go, the more priority Goodreads give to your ad and the more often they’ll show it to target readers. Oh, and you also set a per-day limit on clicks; hit that budget and the ad gets shelved until the next day.

(That’s all pretty cursory; if you want to get more info, here’s the GR advertising page.)

How it worked for me

Back in the second week of June I decided to give Goodreads ads a try. I read through their advice and tried to come up with an appealing tagline for The Obituarist, one that had a ‘call to action’ (i.e. tells the reader to do something):

A social media undertaker gets dragged into a dangerous mystery in this witty crime novella. Click here and add it to your ebook reader!

(Yes, ‘witty’. Come on, it’s a funny book. At times.)

I attached that to the book’s cover and included a link back to its GR page, which I figured would be more useful than its Amazon or Smashwords pages. (Which, yes, makes that ‘call to action’ kinda bullshit.) For the target audience, I went with genre tags - Crime, Ebooks, Fiction, Humor and Comedy, Mystery, Suspense and Thriller. (Humor was a stretch, I admit it.)

Last and most important, I decided to put $60 into the ad campaign – come on, I’m not made of money – with a 50-cent cost-per-click and a 5-click/$2.50 limit per day. I figured that meant the ad would run for 3-4 weeks before running out of money, since obviously I’d be hitting that cap almost every day.

In practice… not so much.

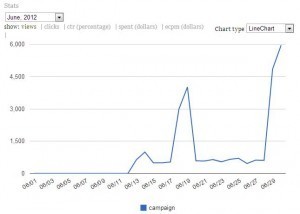

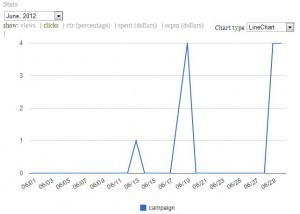

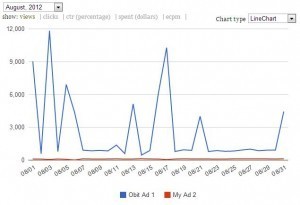

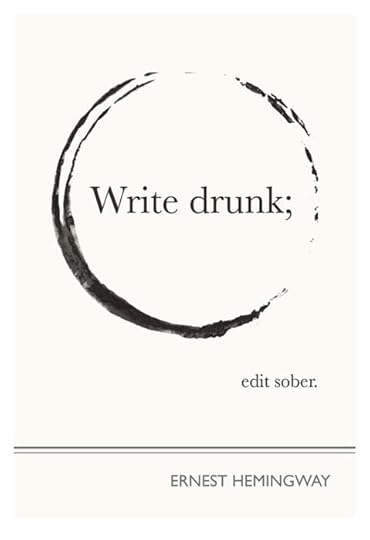

GR provide some nice analytic tools and graphs so that you can watch people ignore your book on a daily basis; here’s how June shook out.

What you can see there (click the graph for a bigger image) is that 50 cents don’t buy you a whole lotta pageviews. For most of the month I was getting about 400-500 views of the ad per day, which in turned prompted zero clicks. It was only when the pageviews spiked to 4000-6000 that I got any clicks on the ad. By the end of June I’d amassed 26 361 views and 15 clicks, taking $7.50 from my $60 budget.

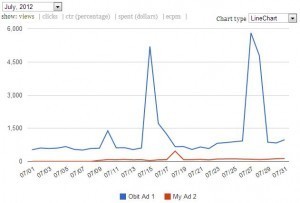

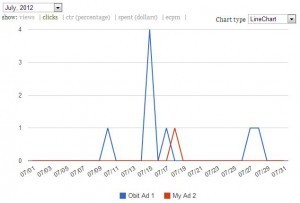

Clearly I needed to change things up. So in early July I added a second ad to the campaign – well, the exact same ad, but this one targeting readers of specific crime authors, mostly those that I liked as well. That didn’t have a huge impact, so towards the end of the month I bumped the cost-per-click to 60 cents. Here are the results:

Once again there’s a low level of baseline activity punctuated by big order-of-magnitude spikes; my best guess is that those are periods when a significant number of higher-paid ad campaigns finish, leaving room for little fish like me to swim around for a short time before getting crowded out again. And, once again, the clicks tend to only come when we break four figures in pageviews. The second big pageview spike is when I upped the cost to 60 cents, but I can’t tell if there’s a definite correlation to the change or if it’s due to external reasons.

We can also see that targeting by author, rather than genre, does pretty much dick. It might be because most readers don’t nominate favourite authors, or because there’s too much overlap with the genre targeting, but the author-focused ad doesn’t even get 100 views most days.

Anyway, July had 39 398 views but only a disappointing 9 clicks, for a total cost of $4.70.

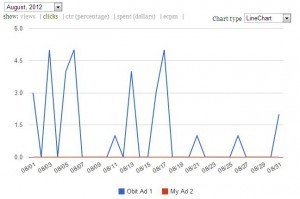

Moving on to August:

Much better! We’ve got more jagged spikes than a pro-wrestler’s teeth here, closer together and higher than before, as are the corresponding clicks. The baseline activity between spiked has also moved up to about 700-900 views per day. (This is also the point where I realised that I hadn’t adjusted the $2.50/day limit on clicks when I upped the per-click cost, so I kinda shot myself in the foot there for the first few days.) It’s also very clear that the author-focused ad isn’t achieving a damn thing; no-one’s seeing it, no-one’s clicking it. Still, it does no harm by existing.

Stats for the month: 83 800 views, 34 clicks and a spend of $18.80.

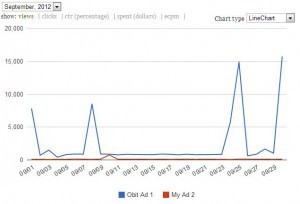

By September I felt that the campaign was dragging, so in an attempt to amp it up I changed the text of the ad to this:

Chandler meets Facebook in this crime e-novella as a social media undertaker is dragged into a dangerous mystery. Available in all formats.

No call to action (or exclamation marks), but it’s a more accurate and (I think) more interesting précis of the book. What kind of effect did it have?

Umm… I think maybe there’s a slight improvement in how many clicks I got on the good days, but that’s just total guesswork. Also, despite not changing the price-per-click, the number of pageview spikes fell right back – confirming, I think, that that’s entirely due to external factors and the number of campaigns competing for eyeballs on a given day.

Also, yay – one author-ad click! Hooray for the cult of personality.

Monthly stats are 78 489 views, 25 clicks and $16.40 spent. Why the extra 40 cents? Because at the end of September I saw that the budget remaining was a multiple of 70 for the first time and decided to bump the cost-per-click again. This time I also remembered to up the daily limit as well.

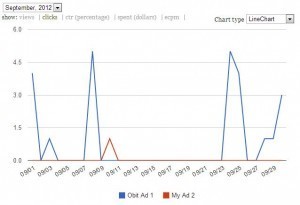

And thus October, where the campaign trundled along before ending about two weeks in.

The graphs pretty much speak for themselves at this point. Stats for the month: 44 335 views, 18 clicks, the last $12.60 gone from the budget.

Was it worth it?

For 60 bucks I got 272 383 page views over four months. That sounds pretty damn baller on the face of it. But that’s only the first data point. More importantly, those views translated into 101 clicks on the ad. Well, okay, a hundred clicks doesn’t suck.

But of course, not every click is a sale, or even more than a flicker of interest. It’s a little difficult to work out exactly what those 101 readers did after clicking – I think the data is there, but I can’t find it in GR’s records right now – but I can see that during the course of the campaign, 37 strangers added The Obituarist to their list of books to (maybe) read. If all of them buy a copy, and assuming a rough and largely inaccurate average of $2 royalty per book (it varies depending on who buys it and from where), then I’m looking at $74, or a total profit of $14. And that’s best case.

Not, um… not the most amazing result.

On the other hand, it’s not a god-awful result either; it’s not like I just pissed the sixty bucks up a wall. Sales-per-click is a crude metric and one that can only disappoint. On a social media site, it’s also about visibility and exposure; it’s about finding readers and then getting them to boost and pass on the signal. This is the start of that, not the end, and as a start I think it’s pretty viable. I may do another round of ads later on, or I might look at Facebook ads instead. Or both.

My recommendations

So if all those graphs didn’t send your brain into vapour lock, and you’re thinking of going the GR route for advertising your own books, here are five quick recommendations based on my experience.

So if all those graphs didn’t send your brain into vapour lock, and you’re thinking of going the GR route for advertising your own books, here are five quick recommendations based on my experience.

Target genres, not authors. It’s really clear from this data that the author-ad was completely useless. Well, maybe not completely; it did garner two clicks, but then again I might have got those clicks from the other ad at some point. Certainly, though, you need to make the primary ad in your campaign a genre-focused one, with an author-focused one only as backup.

Set your cost-per-click above 50 cents. I definitely got more exposure and clicks when I upped the price to 60 cents, and I suspect I would have had more improvement at the 70 cent mark if the campaign hadn’t ended. I think a dollar per click is probably on the high side, though. 60-80 cents would be my mark.

Write a decent ad. This shouldn’t need to be a recommendation, it should be obvious – but I’ve been looking at other people’s GR ads these last few months, and most are completely terrible . Like, ‘incoherent gibberish that doesn’t even tell you the name of the bloody book in question’ terrible. Forget the marketing talk and the ‘call to action’; if you can string together 140 characters that make sense, you’ll have a much better chance of standing out from the trainwrecks.

Back it up with other activity. Goodreads isn’t just an advertising platform; like any social media site, it works because of its communities and their energy. If you become part of those communities, readers are more likely to recognise your name and style and be interested in your work. Just be sure to do so in a genuine way, rather than ramraiding forums to spruick your book and then fucking off again. Be open about how much you love books, talk to other readers and make connections; that gives you a base level of visibility that can be raised by the ads. (This is the bit I have to work on.)

Have realistic expectations. You will probably not become an overnight sales sensation from GR ads. You will probably not blow out your budget in two weeks. You will probably get fuck-all clicks and you won’t be able to meaningfully control the ebb and flow of pageviews. With luck it’ll pay for itself; without luck it won’t lose that much money. It’s just another arrow in your quiver, another frog in your blender; set the ad, let it go, do something else and don’t worry about it.

–

Right, well, there’s 1900-odd words on putting out a 140-character ad. Never let it be said that I can’t talk endlessly about pretty much anything.

Next week – dialogue! I’m not very good at it and now you can be too!

PLEASE STAND BY

WE ARE EXPERIENCING TECHNICAL DIFFICULTIE...

PLEASE STAND BY

WE ARE EXPERIENCING TECHNICAL DIFFICULTIES

IE A BIG FUCKOFF BOX COVERING UP THE WORDPRESS CONTROL PANEL THAT WON’T GO AWAY

ALSO CAPSLOCK

October 18, 2012

Pretty effing great

I’ve been neglecting proper grown-up reading lately in favour of superhero comic collections, largely because the local library system keeps buying more and more of the damned things. (Back onto novels next week, though. Probably.)

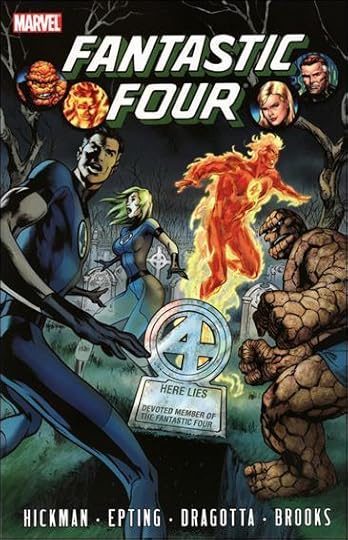

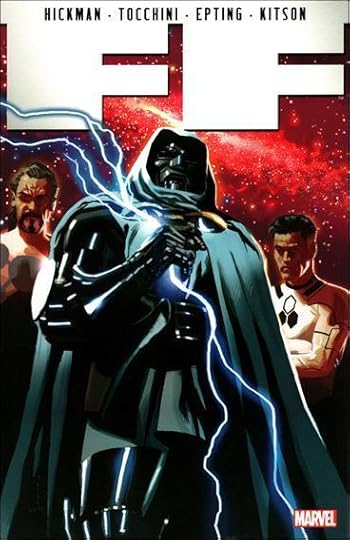

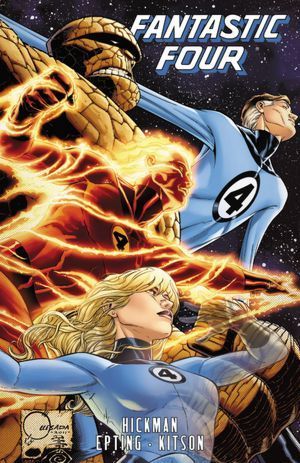

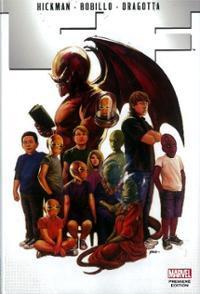

Anyhoo, tonight I want to talk about one particular run of comics that’s well worth a look if you like Really Big Ideas – because it has a lot of them, and pretty neat ones at that. Normally that’s a segue into something by Grant Morrison, but this time I’m speaking of Jonathan Hickman’s run on Fantastic Four.

Now, I’m not a Fantastic Four fan; I’ve always found them the least interesting supergroup in comics and the ‘super-family’ concept has never clicked for me. (Possibly because I struggle with the concept of ‘family’ at the best of times.) Also, Mister Fantastic is boring and a dick. But at the same time, it’s the series where the Stan-and-Jack magic first took shape and revolutionised the whole medium and genre, and the place where Kirby started throwing out that unending series of incredible, impossible ideas – so there’s history there, and precedent, and the best takes on the title are when a writer puts their own spin and direction on that unfettered inventiveness.

And that’s just what Hickman does, putting together a massive, multi-volume storyline that explodes with mad inspiration. I don’t want to spoil anything, so let me just rattle off a few elements – an interdimensional council of Reed Richardses, time travel, a Negative Zone cult, giant mad space gods, the Kree, the Inhumans, even more Inhumans, Galactus, time dilation, cities full of alien life, Nu-Earth on the far side of the galaxy, Reed’s time-travelling father Nathaniel, interdimensional battles, super-intelligent children, even more super-intelligent children, alliances with the Four’s worst enemies against a greater threat and Doctor Doom being a stone motherfucker, all combining and building into one uber-conflict. Along with this come themes of sacrifice, loss, catastrophe and destiny, plus Hickman’s exceptional gift for character development, dialogue and conflict (plus occasional, very clever comedy).

Once the series hits the death of Johnny Storm – that got reported in the mainstream media, so I don’t think I’m spoiling anything – it changes both direction and title, becoming The Future Foundation, or FF, counterbalancing superheroics with teaching a group of super-genius kids (and a giant robot dragon-man). This is also the point where they get new costumes and Spider-Man joins the team, because both those things sell comics. And they’re still bloody good comics.

(Also, Spider-Man is a more interesting character than the Human Torch. That’s right, I went there.)

After a year or so of FF issues (two collections), the old title and numbering comes back but FF remains, splitting the focus into two different comics as things build to a payoff. And a pretty awesome payoff it is. Hickman is still writing both series, but the last arc of each is denouement, aftermath and wind-down; they’ve yet to be collected into trades, but you don’t need them right now; you can knock over all eight trades currently available – like I did in a rush this week – and be very satisfied with the ending you get.

[image error]

Which is not to say it’s perfect. The series stumbles badly in the second Fantastic Four collection, which introduces the four cities/groups that become hubs of the coming uber-conflict. These four issues are both heavy on exposition and light on conflict/action; they all involve some/all of the Four going to one of the cities and then standing around doing nothing while things get foreshadowed for later. The foreshadowing is necessary, true, but it could have been done with a lot more energy and a lot less blatancy. Things pick up after that, and there’s lots of payoff from that slowdown, but pacing problems recur for the rest of the run.

That passivity also comes back at times, and I think that’s an ongoing issue for Hickman; in many of his books, protagonists seem to be overwhelmed mentally or emotionally by events, and take a backseat or spectator role while things happen and/or other characters manipulate things. Throughout the series, control over events falls or is taken from the hands of the Four and is taken up by others, especially Valeria or Nathaniel Richards. They’re interesting characters, yes, and I can see the kind of story Hickman is aiming for – one about destiny and immensity, and the payoff of good and bad decisions against that context – but it’s not always satisfying.

Oh, and the artwork is pretty variable and inconsistent, but it’s never so bad as to be unacceptable and we’re here to talk about writing.

But in the end these problems don’t detract from the strengths of the series – the imagination and impossibility that is the hallmark of pure comics, married to sci-fi visions and a willingness to put characters through an emotional wringer to get a better story. And it is a pretty goddamn amazeballs story.

So get out there and read these comics. They’re neat.

And now, back to proper novels. Well, once I read Hickman’s new series The Manhattan Projects. Oh, and I grabbed Brian K. Vaughan’s Saga; really looking forward to that. And there’s a new volume of Scalped at the library ah fuck it I ain’t never reading stories without pictures no more.

October 14, 2012

Character goals – a COMPilation of elements

‘Strong characters need strong goals’

This is one of those truisms of writing that sounds sensible and useful until you actually scratch at it a bit, and realise that it doesn’t actually tell you what a strong goal is or how to come up with one that makes sense for your character.

(Things that are true are not always useful; things that are useful are not always true.)

But I was thinking this week about characters and goals (mostly ‘cos I was thinking about World of Darkness roleplaying, but it applies to writing as well), and I’ve maybe come up with a trio of idea that combine to making a powerful goal for a character, one that can drive stories and inspire authors.

So what, then, makes for a good character goal? Well, I call it my compilation of elements, because all three start with ‘comp’. Cheesy, yes, but easy to remember!

Compelling

The goal must be something urgent, something that compels the character to work towards it actively and right away. Part of this is having the goal be something that emotionally yanks at the character, so that ignoring it to do something else is unthinkable. Revenge is a good example of this, as is a burning need to seek justice (they’re not quite the same thing). But the time element is also important; a good goal can’t be shelved indefinitely. Perhaps it has to be completed before the opportunity is lost (the murderer must be caught before he escapes the country), or perhaps the goal just won’t mean anything to the character if it’s not achieved right away. There’s room for a goal that can be put aside for a brief period – particularly if the delay gives the character a much-needed advantage, such as an ally or information – but it has to draw the character back even harder after the break.

Complicated

A goal that is easy to achieve is a boring one, and one that doesn’t drive a narrative. A good goal takes work to achieve, and not simple work at that. There needs to be obstacles in the way, conflicts to overcome, multiple stages that need to be achieved. All of this complication requires the character to work hard at things and to approach things from multiple angles – a goal that is difficult, but is achieved simply by killing lots and lots and lots of dudes, is a goal that won’t keep readers’ interest. (The best narrative video games understand this – they stretch player skill in multiple areas at different times to progress towards the end.) Complications allow you to bring in other story elements, like additional characters and plotlines – and most importantly, complications give you lots of ways to introduce different kinds of conflict. Because, as we all know, stories run on conflict.

[image error]

You can kill dudes, Ezio, but now you must BAKE!

Completable

And in the end, the goal has to be something the character can achieve – they can get to a point where they think ‘yes, I’ve done it, I can stop now.’ (That doesn’t mean that they have to achieve the goal – tragedy and anticlimax are wonderful things – but it has to be something they could have achieved if things hadn’t gone wrong.) There need to be milestones along the way to keep the character’s momentum going, and there needs to be a concrete, definable end state. Vague, open-ended goals like ‘gain power and wealth’ don’t keep propelling the narrative and maintain reader attention; eventually they lose momentum and peter out. Similarly, the emotional power behind a compelling goal slowly evaporates if the goal isn’t achievable; it loses meaning, and the ability to care goes with it. Paint a target on your story, point your character at it, and let it explode when he/she hits the bullseye.

(Many thanks to Jeb Darsh for suggesting ‘completable’ rather than ‘concrete’ when I was trialling these ideas on Twitter.)

–

Now, you may look at that list and think ‘well, hang on, I can think of some strong characters that aren’t driven by goals that match that.’

Well, of course you can, because this list ain’t the perfect be-all end-all ULTIMATE SECRET of writing; if I could come up with that, I’d be injecting liquid money into my eye sockets rather than writing blog posts. There are certainly other ways to come up with good character goals; this is one pattern, but every writer finds their own way.

It’s also important to remember, though, that not every strong character needs a strong goal. Goals are important in stories that are driven by character choices and actions, but that’s only one kind of story. Event-driven stories often feature reactive characters, who respond to external needs rather than internal forces, and those stories are just as interesting and powerful. Characters with weaker, vaguer goals are also better suited to open-ended narratives, such as ongoing serials. Comics are a great example; Batman has a goal (to avenge his parent’s deaths and fight crime in Gotham), but it’s not an achievable one or one that must utterly consume him, if only because he has to stop every now and then to help the Justice League fight Starro or something.

But even in these narratives, you can include smaller subgoals, and in turn give the reactive character a more active role for a time. ‘Fight crime’ is too vague and too unachievable; ‘uncover and defeat the Court of Owls’ is a lot more solid and puts Batman into the driver’s seat of a specific storyline. And again, including all three elements – compelling, complicated, completable – makes that subgoal engaging and exciting for the period in which it drives the larger narrative.

–

So that’s my guide to the basics of a strong character-goal. Work out those three elements at the start of your story and you should have enough steam in the engine to power you all the way to the end.

Do you have a different approach? Let’s talk about it in the comments! Come on, people, let’s share.

October 10, 2012

A soft reboot (with a chewy centre)

Folks, it’s time for a bit of a change. Spring is here (along with its cursed handmaiden daylight savings), the sky in Melbourne is a perpetual battle between gloom and glare, comics companies are releasing exciting new titles and I’m starting to think that my blog sucks.

Well, okay, that’s maybe overstating things (and trolling for compliments). Better to say that I’m not super happy with my posts over the last few months, particularly the weekend ones. Too many of them are rambly, waffly things about the theory of narrative, or the subtext of reading, or the veal parmigiana of Kindle or some other thing that only makes sense to me – and maybe not even than. I look back at some recent posts and think ‘I have no idea what I was trying to get at there.’

This is what crack cocaine does to you, friends. Take it as an object lesson.

Anyhoo, I think that this blog has lost its direction – or, perhaps more accurately, that it never really had one in the first place, other than as a place for me to talk about myself and how awesome I am. And I still want to do that – believe me, I never get tired of talking about myself – but I want to be clearer on how I go about that and to write posts that are more engaging/less boring for you, my faithful audience.

So in the spirit of the New 52 (but less shithouse) and Marvel NOW! (but less exclamationy), I’m doing a bit of a reboot of this here blog. Or at the very least a change in creative approach and supporting cast.

Things I want to focus on:

The craft of writing: More than anything else, this is the stuff I love thinking about and talking about. I’m not egotistical enough to think that there’s much I can teach anyone, but I think there’s value in putting up something practical and seeing if it resonates with people, or spurs discussion that can do the same.

Original fiction: More flash fiction pieces and downloadable short stories. I’ve just finished a run of those, but there’ll be more by the end of the year.

My own writing and ebooks: Like, duh. This probably goes without saying.

My publishing experiences: Again, I’m not saying I have any special insight. But I work in publishing by day and put out my own ebooks on weekends, so I’m in the thick of this pretty much all the time, and if nothing else I can warn y’all not to make the same mistakes I do.

Grammar and language: On the other hand, this is where I can maybe actually teach people things they didn’t know. Or at least rant about comma misuse SERIOUSLY PEOPLE THEY’RE NOT THE SAME AS SEMICOLONS DON’T JUST USE THEM LIKE SENTENCE GLUE.

Interviews: I’ve only done a few of these, but they’ve been fun and I think I should do more.

Cool stuff that people should know about: Links, reviews, heads-up about upcoming things… you know, stuff like that. Probably this will mostly be the fodder of midweek posts.

Batman: Let’s face it, folks, I ain’t never gonna stop talking about Batman.

Things I don’t want to focus on… eh, I’m not gonna bother calling them out. Boring stuff. Meaningless gibberish. Lemmings. All that sorta thing.

In the end, I want this blog to be useful, interesting and entertaining, both for long-time readers (both of you) and anyone else that stumbles across it and might pony up three bucks for an ebook find value in it. And when an idea for a post doesn’t meet those criteria, or is a jumble of ideas that doesn’t have a solid core, I’m gonna put to one side while I work out something else to say.

The new era starts this Sunday! Smell the excitement!

October 7, 2012

Dramatic licentiousness

So ‘Inbox Zero’ was released into the wilds last Sunday and since then has racked up a measly 20 downloads. That’s not as many as I would like, given that it’s a free story and that I’ve sold more than 100 copies of The Obituarist and if you LOVED me you’d READ it and DISSEMINATE it and I wouldn’t have to BEG you to do YOUR PART in making this RELATIONSHIP work.

But I’m not going to get into that. Readers will find it, in their own time and own way, without any whining on my part. I’ve moved on.

Instead, I would like to talk a bit tonight about what ‘Inbox Zero’ might (or might not) mean for the ongoing development of the Obituarist concept. Because as a result of this story, I find myself starting to think of Kendall Barber as someone who has… adventures.

And I don’t really want that. Or at least, I don’t want to acknowledge it.

–

But to make sense of this, let’s first talk about dramatic license.

What do we mean by ‘dramatic license’? I think that, in simplest terms, it’s about choosing the interesting over the realistic; it’s making a decision that the world of the story would be better served by not making it line up with the world of the reader. That’s not the same thing as just including things in the story that don’t exist in reality, like dragons or faster-than-light travel; you can have those things and still write a story that cleaves to reality – it’s just a reality with extra stuff in it.

[image error]No, dramatic license is about making choices about how the elements of the story (real or imaginary, and let’s face it, they’re all imaginary) behave and develop, and why they go in that direction. To make the facts serve the story, rather than have the story serve the facts. Or at the very least, making up your own facts to replace the inconvenient ones of reality.

Some genre fiction is pretty forgiving to dramatic license, especially fantasy and science fiction. Crime fiction is much less so, because the best crime stories give the impression that they could have really happened, and hewing as close as possible to the real helps immeasurably with that. (Horror stories swap between realism and unrealism depending on what makes a story scarier or more emotionally unsettling, which is why horror is so much fun to write.)

Sometimes license is about physics and medical procedures and the physical doodads of a story, but more often it’s about character – about the decisions and actions characters take and the way the world reacts to those. On that character level, dramatic license usually boils down to ‘things don’t change’ – because logical consequences aren’t always the consequences you want to explore, and a bad guy that followed all the pointers on those interminable ‘If I Was an Evil Overlord’ lists would bring your story to an early, not-very enjoyable halt. Vampires stay hidden behind the scenes despite investigators learning of their existence. The Dark Lord overlooks that one thing that allows a plucky young adventurer to find his weakness and cast him down. A superhero’s amazing inventions don’t transform the world, and he doesn’t have brain damage or post-traumatic stress disorder despite being punched in the skull by Bane every couple of days.

(You can write a cool story exploring what happens when you don’t take those dramatic liberties, of course. But those stories tend to deconstruct their genres, rather than celebrating them, and sometimes you want to read Justice League (Morrison-era, obviously) rather than Watchmen.)

–

So to bring this back to The Obituarist, I’ve set up a base in the novella that Kendall Barber is not a detective, and that he doesn’t go around solving crimes all the time – his job is unusual but mundane, his life deliberately ordinary, and when a crime falls into his lap he reluctantly gets involved mostly due to poor decision-making. That’s the setup for a stand-alone crime story, something with boundaries – you pass through, go out the other side and get back to reality.

But now here’s ‘Inbox Zero’, another situation where Kendall gets involved with a crime. I’m also planning a proper sequel, a longer story where – you guessed it – Kendall gets involved with a crime. There’ll probably be 2-4 more stories, long and short, in which our regular guy has to play Sherlock Holmes.

And the logical, real-world effect of this would be that the character does start to think of himself as a detective, as do the people around him, and that he attracts attention due to that; that his world and his personality change to reflect what he does. Which would mean that I wouldn’t be able to write the stories that I want to write – i.e. ones without that change.

So can I fall back on dramatic license and handwave away that logical development in tone and character while staying in the grounded genre of crime fiction?

I sure as hell can, ‘cos I’m gonna play the Murder, She Wrote defence.

How many crimes does your average homicide detective solve in a lifetime? Ten, fifteen, maybe more, maybe less, maybe depends what you mean by ‘solved’, and all that over the course of a 20-30 year career. Jessica Fletcher, a retired teacher turned crime writer, solved 268 murders in 12 years – and no-one said shit about it. No-one went ‘holy crap, that’s impossible’; no-one went ‘holy crap, she must be a serial killer’; the FBI didn’t hire her or lock her up. Within the confines of the narrative, no-one pointed out the sheer crazy fucking impossibility of Jessica Fletcher, and dealing with 268 murders didn’t drive her to drink, heroin or Chippendale shagging.

That’s the big dramatic conceit of ongoing crime fiction – that you can right a wrong and not be changed by it, and not have the world see you differently. That you can do it again, and again, and still be who you were at the start.

And that suits me fine at this point. Don’t get me wrong, I have changes and consequences in mind for Kendall Barber; I have shit planned that will turn you white. But I want to keep him in the Jessica Fletcher zone while I do so, and have him say ‘I’m just an IT undertaker, not a detective’ and not have anyone in the story – and hopefully none of you – call bullshit on him (or me).

Come on. You let Angel of Death Fletcher get away with it, and she’s seen more bodies than Larry Flynt.

–

After all of that waffle about what I want to do with my writing, let’s flip it around – what should you do with yours?

Well, whatever you want. Duh.

If you want to do painstaking research and hew as close to the real as possible, with little or no bending of physics, psychology or logic, then that’s great – many awesome books do exactly that, and their grounding in reality makes them feel genuine and engaging. And if you don’t want to do any of that, if you want to do whatever makes sense for your story even if it doesn’t outside its pages, then that’s fine too, and more than fine. Because being a writer is a license to make shit up in service to the narrative, and you’re the one who gets to decide when to keep it real and when to dump logic and realism in a sack and set them on fire.

Write what you know, sure – use the real world as your foundation and your font of ideas. Keep your readers engaged with tiny details, make them feel that your world and characters are genuine and not just amorphous blobs.

Write what you know, sure – use the real world as your foundation and your font of ideas. Keep your readers engaged with tiny details, make them feel that your world and characters are genuine and not just amorphous blobs.

But stories have their own logic. Drama has its own needs. Characters will do as they must, even if it only makes sense to them (and you). And when the needs of the narrative demand that rivers flow upstream from the sea, then turn your boat around and paddle up a waterfall.

Because if you do it well, if you write it powerfully, your readers will pick up their oars and row right behind you. Reality be damned.

September 30, 2012

The Obituarist – Inbox Zero

One short story this month wasn’t enough.

Two short stories this month wasn’t enough.

No, this is a THREE-STORY MONTH – and what better way to hit the trifecta than with a sequel to The Obituarist?

‘Inbox Zero’ is a short story set a while after The Obituarist, in which social media undertaker Kendall Barber is working for a new client, a publisher of customised Bibles. When settling accounts for his recently deceased client, Kendall comes across a Deathswitch email – a message the dead man wanted sent to his family after he passed away. What’s in the email – and why is Kendall’s client so eager to see it?

‘Inbox Zero’ is available for download right now at Smashwords, and it’s completely free – which, unfortunately, means I can’t offer it through Amazon. But it’s available in Kindle-friendly MOBI format, as well as EPUB and PDF, and I’ll be offering a slightly nicer PDF through my Downloads page a bit later in the week (once I find the time to put one together). It should also propagate out to other stores, such as Barnes & Noble and the iBookstore, over the next few weeks.

For those readers who’ve been clamouring over the last few months for an Obituarist sequel, ‘Inbox Zero’ is not it. I mean, it is a sequel, but it’s not the sequel; Obituarist 2 (Electric Boogaloo) is on my to-do list and will probably come out in about six months. This story is more of a quick diversion, a stand-alone story that doesn’t require you to have read The Obituarist already (although it couldn’t hurt) and that will hopefully tide you over until the real deal is ready.

A key element of this story is Deathswitch, a real service that lets you set up an email to be sent after your death. The folks there were kind enough to read my first draft and check the accuracy of the piece, which was very kind of them. As part of my research I set up an account for myself, then failed to respond to my emails, and soon got my email to notify me that I was dead. That was… well, a little odd, but I do whatever is necessary for the verisimilitude of my work.

Because this story is free, I highly recommend sharing the absolute shit out of it. Email it to everyone you know! Put it on torrent sites! Read it aloud on public transport! If it can find some readers and drive them back to The Obituarist, I’ll be happy. Heck, I’ll be happy even if it doesn’t. I have lots to be happy about. Although if you want to make me extra happy, you could leave a comment to tell me you liked the story. And/or a review on Smashwords.

And with that, I’m done with short fiction for a bit. Time to get my head back into YA fantasy and Raven’s Blood.

(And maybe Assassin’s Creed: Brotherhood. Just a little.)

September 27, 2012

Dateline: WRITING

Hi folks,

Just a very quick, very half-arsed update tonight. Why? Because I am hard at work WRITING.

Specifically, I am writing a new Kendall Barber/The Obituarist short story, ‘Inbox Zero’, with an eye towards having it finished and up online for completely free download this Sunday night. That’s right, you heard it here first; refocus your browser onto this site in just three nights to read a cracking 2500-odd words about death and the internet featuring everyone’s favourite social media undertaker.

But that won’t happen if I don’t finish this first draft tonight and then shop it around my alpha readers for feedback. So, you know, no time for love, Doctor Jones.

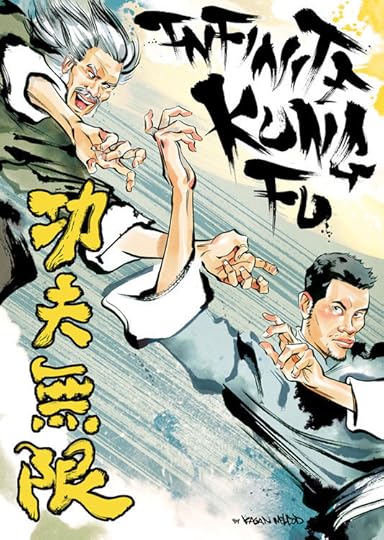

Well, okay, time for one bit of love – love for the amazing graphic novel Infinite Kung Fu, written and drawn by Kagan McLeod and published by Top Shelf. I read this last week, and it is incredible. It doesn’t just have some kung fu. It doesn’t even have a lot of kung fu. It has INFINITY kung fu. And if your heart is so dead that you cannot take joy in seeing a P-Funk grandmaster pull off his own arms in order to execute flawless kata against the legions of the undead, then what the hell are you doing reading my blog?

Well, okay, time for one bit of love – love for the amazing graphic novel Infinite Kung Fu, written and drawn by Kagan McLeod and published by Top Shelf. I read this last week, and it is incredible. It doesn’t just have some kung fu. It doesn’t even have a lot of kung fu. It has INFINITY kung fu. And if your heart is so dead that you cannot take joy in seeing a P-Funk grandmaster pull off his own arms in order to execute flawless kata against the legions of the undead, then what the hell are you doing reading my blog?

Honestly. Some people.

Anyway, Infinite Kung Fu is more than 400 pages long, it costs like 25 bucks (maybe $35 in Australia) and it is MADE OF WIN. You should read it.

And now, back to work.