Patrick O'Duffy's Blog, page 17

March 17, 2013

Nothing but the tooth

So I had a plan for the week that’s just ended. It was to go to New Zealand on Tuesday morning, spend the next three days conducting day-job-related meetings, spend the evenings working on Raven’s Blood in my hotel room and then to fly back on Saturday afternoon.

Instead, this happened:

Yes, my skull turned blue and transparent and a red light flashed in my jaw.

No, wait, I mean I got a toothache. A REALLY FUCKING BAD TOOTHACHE, YOU GUYS. So bad that I couldn’t sleep or focus on writing; so bad I had to cut the trip short and come back on Thursday night. Fortunately my doctor was able to fit me in on Friday morning and I got a root canal. Which are not very much fun, but better than losing your mind due to constant pain.

Ah well. Life goes on.

But this is a writing blog, not LiveJournal, so how can this experience be used in a story? Well, the obvious answer is a story about toothache, but BORING AND ALSO OUCH. I’m more interested in the derailing aspect – the idea of a story cruising along as intended until some outside influence comes into the narrative.

I mean, sure, you could just write it that way – a sudden interruption and then you return to the plot – but that’s not the way to go. As a reader and editor, I don’t like extraneous material in a story; if an event or character or situation doesn’t meaningfully contribute to the story, it doesn’t belong there. Real life has stuff that just happens, but the whole point of fiction is that it’s not real life, even when it pretends to be.

So what are some ways to make something like this work to improve the story?

Let’s say that you’re writing an urban fantasy story in which Con Johnstantine, Greek occult investigator, is looking into a case of crotch goblins manifesting in people’s pants.

…hmm. Possibly the painkillers are still fucking with me. But let’s roll with it.

Okay, so there are crotch goblins and Con is on the case, but in chapter 6 he gets a massive goddamn toothache and needs a root canal. Here are five ways to work that kind of left-field event into the story and make it feel not only relevant but meaningful to the overall narrative.

Delaying tactic

Con is on the case and close to a break-through, but then the toothache knocks him for a loop for three days/pages. When he recovers, it’s too late, and Shit Has Got Real – the crotch goblins are rampaging across the entire city! External distractions and problems can be good obstacles to put in a protagonist’s path to slow them down and raise the tension. They’re especially useful because they don’t damage the character’s perceived competence – Con didn’t let things escalate because he’s a bad occult detective, he just got sidelined by something that could happen to anyone.

Subplot

Con goes to see the dentist, putting the case safely on hold for a while. He strikes up a friendship with a dental technician, and perhaps will learn to love again, but then she gets possessed by the crotch goblins and the tragedy renews his determination to rid the world’s underpants of evil. To be honest, I don’t love subplots – unless you’re working in a strongly compartmentalised milieu like TV or comics, I generally find them distracting. Stay focused on the core story, rather than noodling around the edges! But an exemption can be made for subplots that illustrate points of character or personality, or let them develop in ways that the main plot probably wouldn’t allow.

Key subplot

Better yet, have the subplot lead into plot points that directly impact the core storyline. Even dulled by anaesthetic, Con realises that novocaine would be a useful weapon against the crotch goblins. He grabs a case of it from the dentist’s after chatting up the dental technician and uses it to take out most of the goblins before fighting their king, David Bowie. This is more satisfying because the diversion means something concrete; on the other hand, you shouldn’t make the subplot an absolutely vital part of the story’s outcome. A secondary plot should help overcome a secondary obstacle, not the primary obstacle.

Better yet, have the subplot lead into plot points that directly impact the core storyline. Even dulled by anaesthetic, Con realises that novocaine would be a useful weapon against the crotch goblins. He grabs a case of it from the dentist’s after chatting up the dental technician and uses it to take out most of the goblins before fighting their king, David Bowie. This is more satisfying because the diversion means something concrete; on the other hand, you shouldn’t make the subplot an absolutely vital part of the story’s outcome. A secondary plot should help overcome a secondary obstacle, not the primary obstacle.

Parallel plot

Con thought crotch goblins and toothache were problems enough – until he realised that the dental technician was in fact the Tooth Fairy, hidden in witness protection and being hunted by the Toothpaste Mafia! Now he has to protect his new love and the city while manoeuvring his two enemies into wiping each other out in a riot of mouthwash and underwear. This is the classic A-plot/B-plot structure used in many a book (including The Obituarist) and it’s a great way of adding depth to a story without muddying the waters of a single narrative. Swap from one to the other, using the moves to control pace and tension, and then bring them together at the end.

Swerve

Hah! You thought this book was about crotch goblins! But no, it’s all about Con and the Tooth Fairy fighting King Colgate and his army of floss demons, ready to crack open the dentures of all reality! The goblins were just a fake-out, and Con can clean them up with a holy water douche in the denouement or epilogue or something. This kind of bait-and-switch can piss off readers who get invested in the fake-out early, but if you’re careful with it you can use it as a form of world-building; it gives the strong impression that there are many equally valid concerns in the world that the protagonist must deal with, rather than just one cah-RAZY problem.

So whether your story’s about crotch goblins or academic intrigues or just too many hot dudes wanting the protagonist’s number, there are ways to throw a wrench into the works and still make it feel organic and meaningful, rather than tacked on.

Just be sure not to hit me in the face when you throw that wrench. My gums are still pretty tender.

–

In other news, I turned 42 yesterday. Whoo! It was a somewhat muted celebration, as I’m still not in great shape from the root canal, but I’m having a proper party next weekend.

If you feel like giving me a present, consider the gift that keeps on giving – a positive review of one of my ebooks over on Amazon, Goodreads, Smashwords or anywhere else that people might see it. Come on, folks, this dental work isn’t going to pay for itself!

…man, what if dental work could pay for itself somehow? There’s a story in that. A squicky one.

March 9, 2013

Ignore me

Hola folks,

My peoples and I have gone down to a property outside Ballarat for the long weekend.

It’s fucking hot, internet access is intermittent and I’m spending most of the time drunk, so it’s not the best environment for writing a good blog post.

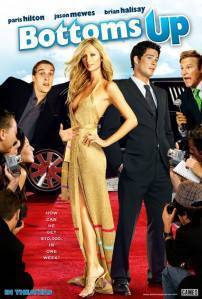

So here’s a picture of some random meme crap, and a promise to come back next Sunday with something more interesting and coherent.

Now if y’all will excuse me, there’s a hammock with my name on it.

March 3, 2013

So what’s up with you?

I do a lot of talking on this thing sometimes.

But tonight I sat down at the computer and couldn’t think of anything to talk about. I’ve said my piece about worldbuilding for the moment, I put out Nine Flash Nine, I don’t have any appearances or conventions to spruik and there’s not much I can say about Raven’s Blood right now than that I’m busily writing it.

So I thought it might be interesting to turn things around for once and ask you guys a few questions – about this site, about what you’re doing, about whether I still look dead sexy despite turning 42 in a couple of weeks.

No need to answer that one. I know I look good, as this recent photo will attend.

But my slightly-sunburned features aside, here are a few things I’m wondering about. This would be a great time for any of y’all to leave a comment or two, ‘cos lord knows I don’t get enough people weighing in on things after I’ve left one of my usual walls o’ text.

What kind of posts on here have you found interesting?

Little self-aggrandizing, I know, but it’d be good to know what entries have really clicked with people. I know the Oxford comma and costs-of-publishing posts got a lot of feedback. Were there others that maybe flew under the radar?

What sort of thing would you like me to write about in future?

Sort of the same question as before, but in the other direction. Are there topics worth revisiting? Should I write more about grammar, or put up more flash fiction? Are there new topics that you cannot wait to read me dropping some ‘wisdom’ (ahem) upon?

What’s happening with your own writing?

Okay, enough about me. What have you been doing? What can you share with the class? Have any of you been working through my 2013 to do list?

What’s your opinion of book trailers?

Does anyone watch these? Are they useful? What do they need to include to make you want to read the book? I’m kinda dubious on them, but people make ‘em and watch ‘em, so I should probably think about ‘em some more.

Do you use any book/library social media sites?

I’m on Goodreads, which I use a wee bit as a writer (including my experiment with ads) but probably more as a reader, and even then I only use bits of it. What about you? Goodreads? LibraryThing? Something else? Do you find those sites useful, and if so, how?

Have you tried reading ebooks on different devices?

I have a Kindle (although not a sexy PaperWhite) and I like reading on it just fine, but occasionally I wonder whether a Nook or a tablet would provide a superior experience. Have any of you done the comparison? What did you find?

Where do you go for book reviews?

I really don’t know where to look for reviews these days – there are so many sites and so many voices that it’s hard to know who to listen do. So where do you go? Who do you rely on? Do you bother with reviews at all?

What books are you excited about right now?

There’s gotta be something lighting a fire in your head right now, either because you’ve just started it and it’s great or because you know it’s coming and you can’t freakin’ wait for it to arrive. So what’s it called, and why is it awesome?

Drop me a line, peoples. Throw them answers out there and get me to work.

February 25, 2013

East and west – the people of Crosswater

Now, where was I before I went off on a tangent about my hot new collection of flash fiction (oh go on buy one it’s really cheap papa needs a new pair of shoes)?

That’s right, worldbuilding. (Still.)

Two weeks ago I talked about how people are the most important part of worldbuilding, the thing that connects most strongly with readers, and gave a few rough tips on developing cultural elements and ideas. So here’s a post to sketch out the two main cultural groups in Crosswater, the town that is the setting of Raven’s Blood, and how I’ve applied those ideas in this case.

(Wow. I wrote that like I was some kind of expert, rather than someone half-arsedly fumbling through ideas he’s only just had and still can’t fully articulate. Go me.)

The Westrons

The Westrons are native to Crosswater and the lands to the west. They tend to have dark skin (ranging from olive to almond in complexion) and straight hair. Originally a loose collection of towns and city-states, Westron society gathered together over the last few centuries into a cohesive kingdom. Originally Crosswater was the seat of the kingdom, but after the War Against the Host the royal family relocated to another city further inland. Still, Crosswater remains the mercantile hub of the kingdom and a centre of trade, travel and intrigue.

I based Westron society on Elizabethan England – originally just because I loved the image of masked heroes in ruffs and surcoats, but I soon realised that that this also gave me a lot of other story options. Technologically, it let me include cannons, pistols, the printing press and other such devices without needing to justify their presence too much, letting me focus on magical anachronisms like golem-armour and grappling-hook guns. Patterning Crosswater after London gave me plays and culture, but also narrow alleys and bunched-together houses perfect for parkour scenes. And it gave me a society founded on business and trade but also with a strong military bent. I could have made all of things up whole cloth, but the shorthand of ‘it’s like Elizabethan England’ lets me get it across quickly so I can spend more words on action and explosions.

I based Westron society on Elizabethan England – originally just because I loved the image of masked heroes in ruffs and surcoats, but I soon realised that that this also gave me a lot of other story options. Technologically, it let me include cannons, pistols, the printing press and other such devices without needing to justify their presence too much, letting me focus on magical anachronisms like golem-armour and grappling-hook guns. Patterning Crosswater after London gave me plays and culture, but also narrow alleys and bunched-together houses perfect for parkour scenes. And it gave me a society founded on business and trade but also with a strong military bent. I could have made all of things up whole cloth, but the shorthand of ‘it’s like Elizabethan England’ lets me get it across quickly so I can spend more words on action and explosions.

The stereotypes of Westrons align with their mercantile society – they care about money and business more than family, they see outsiders as opportunities (or threats) rather than as people, they always look for the profit or power in an interaction and they’re very concerned about status and wealth. Those stereotypes also tie back to the theme of Westron magic, that everything has a price. They’re a people who expect to pay for everything they get, and look at gifts with suspicion. The flip side is also a willingness to suffer losses to get ahead – most of the victories in the War Against the Host came from soldiers sacrificing themselves (or their subordinates) in order to make gains. That readiness to sacrifice can be a nobility in some Westrons and a callous ruthlessness in others.

The Easterlings

Easterlings tend to have pale skin (ranging from light pink to almost white in complexion) and curly hair. Hailing from far-off lands, their society has suffered radical changes in a short time. Like the Westrons, they were originally a collection of independent states, ones more inclined towards sorcerous war than trade. But sorcery proved their undoing, as it brought the Host to the mortal plane, and those 27 evil angels conquered the Eastern states and made them into an empire, corrupting the lands in the process. The Easterlings lived as slaves to their blazing gods for three hundred years, until the Host were cast down in the war against the Westron armies. Twenty years later, the Easterlings in Crosswater (and other Western lands) bereft of roots and separated from the blighted lands their fathers called home.

[image error]Easterling society is a shaky mash-up of ancient Greece and ancient Egypt – almost as if the first abruptly morphed into the second, Zeus and the gods becoming manifest and demanding not just worship but utter servitude. It’s not a stable kind of change, but it’s not meant to be; it’s a reflection of the theme of Easterling magic, that change begets change. Pushed through worship into slavery and then out into an uncertain, penniless freedom in a land that doesn’t want them, Easterling society is shell-shocked and on the defensive, ready to change again if the situation allows it. (Greece and Egypt also inform Easterling aesthetics and technology, but not so much as with the Elizabethans/Westrons.)

The stereotypes of Easterlings in Crosswater are generally not pleasant – they’re a poor, untrusted underclass for the most part, sometimes derided as ‘worms’ due to their pale skin. Many Westrons assume that Easterlings still worship the Host and would continue their holy war against the West if given the opportunity. The truth is more complex. Some older Easterlings do venerate the memory of the Host on some level, but it’s a reverence born of fear (and a little Stockholm syndrome) rather than love. Younger Easterlings are generally glad to be free, but chafe against the social and political restrictions the Westrons impose on them. But where can they go? Their lands are gone, so they have to leave in the hot, hostile West – and more and more of them are ready to fight for what they need.

–

As you can see, the stereotypes are stronger on the Westron side, mostly because they’re more solidly anchored in real-world history and the context it brings with it. I have to do more work to make the Easterlings real, but at the same time they’re so strongly defined by recent events that I don’t have to look back too far to find (i.e. make up) inspiration and context for how characters act.

And when you get these two groups together - say in a city where Easterling resentment is rising and where there are rumours that the Host have returned – then conflict is inevitable. And conflict is where the story happens.

–

That’s probably enough about worldbuilding for a while, and indeed Raven’s Blood. Time to focus on writing the book, rather than about the book.

Come back next week! No idea what I’ll be discussing then!

February 19, 2013

Now on sale – NINE FLASH NINE

Hiya folks.

Say, remember how whenever I’d put up a flash fiction piece over the last year or so, I said that one day I’d collect a bunch of them and put them into a cheap e-anthology called (for some bizarre reason) Nine Flash Nine?

(That day was meant to be like two days ago, but I got distracted and then I left the USB behind and look never mind.)

Nine Flash Nine is a collection of nine flash fiction stories for ninety-nine cents, hence the rather odd title. Regular readers will have seen some or most of these before, but not all, and anyone discovering this for the first time will marvel at the variety of ideas, themes, swear words and abrupt endings!

The table of contents goes like this:

For Sale, Baby Heads, Never Worn

Murder, She Rocked

Boy

Dear Penthouse Forum: I Fucked Godzilla

Black Veil and Gloves

Got the Horn

Ghost (Moustache) Story

High School Methical

Giant Spiders Cannot Exist

There’s some silly stuff, there’s some weird stuff, there’s at least one story I find a bit emotionally confronting and there are a bunch where I say ‘fuck’ a lot. It’s a pretty fun, very cheap little collection and I hope people dig it.

Nine Flash Nine can be purchased as a 99 cent ebook from the following sites:

The Amazon Kindle Store has the Kindle version (well, it will have soon, once they vet it)

Smashwords has ePub, Kindle, PDF, HTML and Word versions

Other sites (Barnes and Noble, iBooks etc) will have it eventually, and I’ll update as the links go live

All sites should have a sample of the anthology that you can read for free.

As usual, I’ve added a specific page to the site for the book, so if you want to tell your friends to check out Nine Flash Nine, link to this page here.

I’ll probably do some relentless spamming marketing and promotion for this in the upcoming weeks and months, but not too much – this is a mostly-for-fun book, and it didn’t cost me anything to publish except my ‘valuable’ time. Let’s see how well it can do.

And finally, a big thanks to Chuck Wendig, whose semi-regular Flash Fiction Challenges over at Terrible Minds were the spur that got me to write most of these stories. If you like them, that’s on him; if you hate them, well, that’s probably my fault. But fuck it, blame Chuck too. He’s a big man, he can take it.

–

One of the reasons I finally got Nine Flash Nine out the door is because I was starting to feel restless – I haven’t published an ebook (aside from some free short stories) since releasing The Obituarist back in May 2012. I had originally planned to have Raven’s Blood out by now, but that’s not going to happen for two reasons, and so I wanted to put out just a little something to remind all y’all that I exist.

What are those two reasons? Well, first is that it’s taking longer to write than expected, and that’s mostly because it’s become a larger, longer story than I had originally planned. I was going to write another novella (about 30k words), which I think is a form that really suits ebooks. But as I go further into Kember’s adventures, I’ve realised that this needs to be a full-length novel of 50-55k words. So it’s not just longer to write, but it also needs a rethink of the pacing and prose style.

The second reason is… well, hey, if it’s going to be a full-length book, then why not try to get it onto bookshelves? I think this story has a good shot at finding a hardcopy publisher and I’m going to try exploring that route. I’ve no idea how at this stage, but the first step is getting more of the book done. Once I’m close to finishing a final draft, I’ll start talking to people – I don’t have many industry contacts but I do have some, and hopefully they can point me in the right direction.

And hey, maybe that way I can write some blog posts about the search for publishing fame! Come on, I gotta find something to write about here every week. You people are killing me.

I’ll keep you guys posted. For now, enjoy the book with the Godzilla-fucking.

February 10, 2013

Culture wars and pieces

So I was in Shanghai last week. And you know what the defining feature of Shanghai is?

If you said history, high population, international business activity or shitloads of skyscrapers – no. Well, yes, but no. Those are traits that could also be applied to New York, Los Angeles or London. The defining feature of Shanghai is this:

It’s full of Chinese people.

What I am trying to get at, in case you think I’ve suddenly turned into Obliquely Racist Guy, is that what really defines a city or country to us – what makes us connect with it in a personal, meaningful way as a real place – is people. History, geography and architecture are important, of course, and fascinating to many of us (I’m always taking pictures of buildings), but it’s people, both as individuals and a broader culture, that truly give a place personality and meaning, that drive the events and experiences that we remember once we go back home.

It’s the same when it comes to worldbuilding – hell, even more so. History requires exposition and architecture requires description, and in prose those are both passive processes, stretches of words where the reader just takes information in. Interaction with characters is active, placing the reader within an immediate POV and letting them experience the protagonist and their world in real time. Well, as real-time as reading gets, anyway.

So when you’re building a world for your story, put the cultures of the setting in the forefront. They don’t have to be super-detailed or staggeringly unique, but if the people of your setting feel distinctive and engaging, your world will too.

How to do that? Here are a few ideas, based partially on how I found myself describing my impression of Shanghai and its inhabitants to folks back home and partially on the usual theorywank I engage in when I’m not wasting my life playing Guild Wars 2.

Stereotypes are your friend

When we talk about a culture we talk in stereotypes – the French like gourmet food, the British like Neighbours, Australians are always drunk and our reality TV shows are all mean-spirited, blah blah blah. According to my experience, Chinese people smoke a lot, haggle on prices and don’t indicate when turning. Are those stereotypes universal truths? Of course not. But they serve as useful broadstrokes for describing a culture; they let you set a baseline for the minor characters of your story. That also lets you define your major characters in how they don’t conform to the stereotype, or at least not to every aspect, and that makes them stand out more when they take the stage.

Obviously I’m not talking about embracing offensive stereotypes. Well, hang on – maybe think about those too. What are the racist slurs and stereotypes that are used within your story? How does culture X demonise culture Y and cast them as The Other in your setting? Stereotypes can be what most people in your culture are like, or what other people perceive them to be – and that tells the reader a lot about the intercultural dynamics of your story. It also gives you another characterisation tool for describing an antagonist – because hey, everyone loves to hate racists. They’re douches.

Steal from the real

Fantasy and SF worldbuilding gives you a chance to be incredibly imaginative and original, but originality can be a lot of work for not that much return. There’s nothing wrong with taking a real-world culture as the basis for your fantasy one – there’s a vast variety of them and they’re all different but still geuninely human. These are all ways we have collectively made sense of the world in the past, so anything mirroring that foundation is going to have a headstart in believability. That doesn’t mean you should just dump Shanghai onto Mars, of course, or have a fantasy culture called the Shinese who live in Shina. But you’re not going to do that; you’re going to take the core concepts and traits and then build something new with them.

And you can also pick and choose what you use, not just from one source but from many. Take a chunk of Chinese society and mix in some English customs, some French cuisine, some American beer, some Japanese pop culture and you can make something that feels entirely fresh and new. Or that feels just like Shanghai, which is an amazing mash-up of a city.

Tie it back to your themes

I’m going to keep harping on this until everyone finally gets sick to death of it – everything in your story should have a purpose. Details that are included just to develop the world don’t feel meaningful if they don’t also develop the narrative; they may provide verisimilitude but they won’t be interesting. The societies of your world are as much a component of the narrative as anything else, and they need to underpin the themes and motifs of your story. Which is actually a useful storytelling shortcut, rather than a cumbersome editorial edict.

If you want to tell a story about freedom and authority, you can create a society that embodies that struggle on a macro level as a thematic mirror for a character’s micro-scale struggle. If Fairyland’s people live in a whimsical culture, that helps you tell a whimsical story – and if that whimsy masks a more dangerous capriciousness, then your characters can help you tell a story that has that dark edge of uncertainty.

Remember, the flipside of ‘everything must have a purpose in the story’ is that everything in the story can be used to help you tell the story. It’s a good thing.

–

So anyway, those are (some of) the principles I’d apply to my fictional cultures. And I’ll put my money where my mouth is next time by looking at the cultures of Raven’s Blood through that lens.

…actually, no I won’t. Because the next blog post is going to be about something TOTALLY DIFFERENT.

Stay tuned. It’s exciting.

Honest.

February 2, 2013

Hi/bye/Shanghai

And he’s back!

In the last seven days I’ve flown to Shanghai, ridden a maglev train at over 400 kph, drank lacklustre cocktails in a bar with an incredible view, wandered through street markets, gotten lost, saw a cute baby nearly cause a riot in a department store, bought a bespoke suit and additional clothing items for practically nothing, witnessed a marriage proposal on the bullet train to Beijing, was turned back after entering the Forbidden City (ironic), nearly froze to death in Tienanmen Square, ate duck, walked on the Great Wall of freakin’ China in subzero temperatures and surrounded by impenetrable fog, read and then deleted a whole pile of ebook samples on my Kindle, explored the alleyways of the French Concession, paid my respects at the Jade Buddha Temple, got dressed up to drink better cocktails in a bar with a lesser view, sailed the MoonBoat, went to the world’s most amazingly shithouse chocolate-based theme park (complete with Harry Potter’s Murder Room I SHIT YOU NOT), walked out of a goddamn terrible restaurant, bought a friend a Godzilla onsie and flew the redeye for 10 hours back to Australia.

What have you been up to?

–

Me being me, I also spent some time thinking about what I could draw from the experience to use in my writing, most of which came back to my current theme of worldbuilding.

And I’ll make some posts about that, but not tonight. Because I’m tired.

So wǎnān, peeps – I’ll start throwing around the thinkwords again this time next week. Tonight I’m off to bed.

January 21, 2013

The magic of Raven’s Blood (part 2)

I don’t know about you, but I spent my Sunday afternoon running through a warehouse shooting zombies with a laser carbine – all as part of the IRL Shooter / Patient Zero project, which turned out to be excellent fun. As a result, though, I’m pretty freakin’ tired, as I’ve squandered all my adrenaline by lugging around a 4kg gun while screaming ‘contacts!’ every few moments. So as a result, I was too weary last night to finish this post, and that’s why it’s a day later than usual.

Now, where were we? Oh yes – talking about magic in the world of Raven’s Blood. Last week I talked about the magic of the Easterling lands; tonight’s it’s the turn of the Westrons.

The magic of the West

As before, there is a core principle behind Westron magic – everything comes with a price. In order to gain magical power or control over the world, or to channel that power through something else, one must make sacrifices and give up something in return. Minor or limited power may only require a small sacrifice, a cost in time or resources – but true power only comes after you give up the thing that matters most to you, perhaps the thing that made you seek power in the first place.

Story function: ’Will this character succeed?’ really isn’t that engaging a question in fiction, because the answer is generally always yes – and if it’s no, then you usually have fair warning of what kind of downbeat sadface stuff you’re reading. ‘How much will this character sacrifice for victory?’ and ‘Is this character willing to lose in order to win?’ are much more interesting questions, and that’s what I’m hoping to emphasise with the principle of Westron magic.

Thaumaturgy

The esoteric, gross form of Western magic is thaumaturgy – bargaining with the spirits of the higher planes for power. Specifically, thaumaturges use rituals to call and then bargain with the 27 Lords of the Lunar Court, which are governed by the Queen of Night and Regret. These spirits have great power and can lend that power to mortals, but it always comes with a price. That price is always something that matters on a personal level to the thaumaturge, for the Lords are beings of fate and meaning, and it’s fate and meaning that they rework to fulfil the bargain. A thaumaturge might give up the chance of ever knowing true love, or the ability to know joy, or of ever sleeping without nightmares again.

The esoteric, gross form of Western magic is thaumaturgy – bargaining with the spirits of the higher planes for power. Specifically, thaumaturges use rituals to call and then bargain with the 27 Lords of the Lunar Court, which are governed by the Queen of Night and Regret. These spirits have great power and can lend that power to mortals, but it always comes with a price. That price is always something that matters on a personal level to the thaumaturge, for the Lords are beings of fate and meaning, and it’s fate and meaning that they rework to fulfil the bargain. A thaumaturge might give up the chance of ever knowing true love, or the ability to know joy, or of ever sleeping without nightmares again.

In exchange, the Lords grant power, whether power over the self, over others or over the world. A thaumaturge may become strong enough to kick through a wall or fully recover from a wound within days. She might control flames or winds, cloud the minds of others to become invisible or coax obedient life into stone or wood. The extent of the bargain is up to the whim of the Lords and the nature of the sacrifice. Thaumaturgy is not a common art, and its practitioners are seen as forbidding, dangerous people, but not feared as much as monstrous ichor-sorcerers.

Story function: While sorcery gives me flashy, overt and scary superhumans, thaumaturgy allows for more subtle characters in the style of Captain America, Black Widow, Spider-Man or any of the Bat-family. These are the characters that seem normal until they reveal their secret side, for good or ill. Thematically, the nature of the bargain reflects a core motif of superhero comics, especially Marvel comics – power has an innate tragedy to it. Characters lose what matters to them, and as the story progresses, they have to consider whether the loss was worth the gain.

Artifice

The mundane, subtle form of Western magic is artifice – building tools and devices and then imbuing them with unusual or supernatural power. Artifice is a complex art that requires great study, but a skilled artificer can craft objects that are almost miraculous. The more powerful the item or its magic, the rarer and more valuable the materials needed to create it. In order to fund their projects and pay for their materials, many artificers sell their services and their creations; the most powerful are also the most wealthy – and the most in need of more wealth.

Story function: More toys, of course – magic swords, golems and crystal balls, but also exo-skeletons, rocket packs and lightning guns. Raven’s Blood is a gleeful mash-up of fantasy and supers, and awesome gadgets are a mainstay of both genres, so I knew I had to have some way of bringing those on board. I don’t have an Iron Man or Tony Stark character in mind yet, but you never know.

Story function: More toys, of course – magic swords, golems and crystal balls, but also exo-skeletons, rocket packs and lightning guns. Raven’s Blood is a gleeful mash-up of fantasy and supers, and awesome gadgets are a mainstay of both genres, so I knew I had to have some way of bringing those on board. I don’t have an Iron Man or Tony Stark character in mind yet, but you never know.

Artifice also gives me a more socially palatable alternative for Westrons to look up to. Everyone knows that thaumaturgy exists, and the rituals to call the Lords are simple to learn and perform, but the cost is high, too high for most people to bear. Artifice is a more difficult, more technical form of magic, but all it costs is time, effort and materials, and artificers are respected artisans. Well, until they decide to steal all the orichalcum in the city to create an army of robots…

–

(As an aside – I reserve the right to change the names of characters, ethnicities, magic systems and pretty much everything else as the book progresses.)

–

East meets West

It’s easy to see similarities between the two forms of magic, both on a narrative and a conceptual level. That’s deliberate. I like developing a structure and then seeing how it can be filled, so breaking each set of ideas down in the same way – core principle, esoteric form, mundane form – is conceptually satisfying to me and lets me think about ways to apply that approach to different ideas in the future. If I did a sequel and wanted to involve necromancy or dwarven iron-lore (oh yeah, the dwarves, forgot to mention them), then I have a framework to start developing those and drawing out core themes.

I also like drawing parallels between things, which is another reason why the structure is repeated along with some core narrative elements. Why are there 27 Hosts and 27 Lords of the Lunar Court? What’s the connection there? Do people in the setting see the similarity? Those are questions I want readers to ask, and they’re questions I will probably address at some point. Once I work out the answers.

Themes aside, the two forms also interact narratively within the story in various ways. Artifice and alchemy pair up nicely, and it’s possible to learn both skills and draw on both disciplines – the creation of pistols and rifles after the war was just such a project, packing explosive burn-salt into hand-crafted iron tubes and stocks. It also means our heroes can (and do) happily use both smoke bombs and magic swords at the same time. Sorcery and thuamaturgy, on the other hand, are completely incompatible – the use of one forever precludes the other. Is that a physical incompatibility or a supernatural one? That’s a good question, and again the kind of thing I want readers (and characters) to ask.

–

Okay, that’s enough on the subject of magic. Hopefully it’s got you intrigued as to how I develop those ideas and use them to evoke kick-arse scenes and drive interesting stories; if not, well, we probably both could have found better uses of our time than this blog post.

I for one do have better things to do next weekend – I’ll be flying off to Shanghai for a week, along with my lovely wife! We’ll be hanging out with friends and celebrating a 40th birthday by exploring the Paris of the East (and taking a bullet train to Beijing and back). As a result of this, and because I’m going deliberately internetless for the duration, there’ll be no PODcom update next weekend – and depending how late we get back, maybe not the weekend after. We shall see.

It’s okay to tell me you’ll miss me. You’re among friends here. Just try to soldier on while I’m gone.

January 13, 2013

The magic of Raven’s Blood (part 1)

Chekhov’s Law is generally couched as “if one shows a loaded gun on stage in the first act of a play, it should be fired in a later act”.

Here’s my corollary law for fantasy: if your wizard character casts an ice spell in chapter 5, they should have to freeze a lake solid to save the day before the end of the book. The fact that Merlin-9000 uses ice magic needs to matter, and it needs to create a meaningfully different story than if he used fire magic or forcibly converted all his enemies to Mormonism.

Or, more succinctly – magic needs to shape and be shaped by the narrative.

Yes, this is one of those places where my theories on worldbuilding bubble up and make me massively fucking annoying to talk to at parties.

In keeping with my bottom-up approach to worldbuilding, my primary thought as I’ve come up with the magical bits of Raven’s Blood is not ‘what kind of magic would make sense in this world?’ but ‘what kind of magic would best reflect the themes and tropes of the story I want to tell?’ To develop that, I’ve thought a lot about what those themes are, what kind of principles could support narratively interesting cores, and what might engage a YA audience without replicating stuff they’ve seen before. Most of all – what kind of magic makes for an exciting fantasy superhero story?

So tonight, here’s a look at one of the two schools/fields of magic in the world of Raven’s Blood – what they are, what principle drives them, and how they feed into the story I want to tell. Hope you find it interesting.

The magic of the East

The magical traditions of the Eastern lands all rest on a single principle – change begets change. When a person, object or substance undergoes physical changes, they may mentally or supernaturally change in turn, and that change may foster and force more changes to follow.

Story function: The Easterlings and the Host were the enemies of the West, but that was 20 years ago; now the two cultures live in relative harmony in Crosswater. But invasions bring change in their aftermath, whether physical or social, and one theme of Raven’s Blood is looking at those changes and seeing how stable and/or how genuine they truly are. Basing Easterling magic on change – often degenerative, uncontrollable change – underlines that theme and pushes characters to think about their reactions to change and the Other.

Plus, hey, this is a YA story – the way I see it, such stories should always be about change in some way.

Sorcery

The esoteric, gross form of Eastern magic is sorcery – the direct channeling of otherworldly power through a human agent. Sorcerers deliberately induce changes in their bodies (or their minds, in some rare instances) in order to change their natures, opening themselves up to the powers of the Otherworld. There are various techniques for this, all risky, painful and difficult, but if they succeed then the sorcerer permanently gains a number of magical abilities. The process can also change the world around the sorcerer, bleeding into the land, mutating wildlife or weakening the fabric of reality – which is how the 27 members of the Host were able to enter from the Otherworld 300 years ago and enslave the Easterlings. The Host are masters of sorcery, agents of change that alter and corrupt the world just by existing, and the ichor in their veins is the most powerful of mutagens. Those changed by ichor – especially those changed involuntarily, perhaps due to being wounded by the Hosts’ powers or ichor-stained weapons – are called the blight-touched.

The esoteric, gross form of Eastern magic is sorcery – the direct channeling of otherworldly power through a human agent. Sorcerers deliberately induce changes in their bodies (or their minds, in some rare instances) in order to change their natures, opening themselves up to the powers of the Otherworld. There are various techniques for this, all risky, painful and difficult, but if they succeed then the sorcerer permanently gains a number of magical abilities. The process can also change the world around the sorcerer, bleeding into the land, mutating wildlife or weakening the fabric of reality – which is how the 27 members of the Host were able to enter from the Otherworld 300 years ago and enslave the Easterlings. The Host are masters of sorcery, agents of change that alter and corrupt the world just by existing, and the ichor in their veins is the most powerful of mutagens. Those changed by ichor – especially those changed involuntarily, perhaps due to being wounded by the Hosts’ powers or ichor-stained weapons – are called the blight-touched.

Sorcery is not a flexible form of magic – a sorcerer may manifest a handful of magical abilities that can only be used in a few ways. But it is powerful, especially when ichor is the mutagen that changes the sorcerer’s body – a blight-touched warrior might be totally impervious to blades, strong enough to toss a horse across a river or able to vomit clouds of gas strong and large enough to poison a regiment. In order to channel and contain that power, though, the warrior is changed – he might be nine feet tall, bulging with muscle, constantly streaming noxious vapours from his mouth and eyes or (of course) totally mad from constant pain or from the corrosive, inhuman influence of the ichor in his system. And that influence may warp him even further in future.

Story function: Sorcery gives me a way to include bizarre, twisted superhuman characters in Raven’s Blood, the kind that make for great villains. Brutes like Killer Croc or the Hulk are obvious options, but so are Poison Ivy, the Red Skull, Two-Face, the Human Torch, the Silver Swan, the Parasite… pretty much anyone that wears their power on their sleeve and doesn’t just look like a normal person. The corrosive effects of gaining power also let me include monsters, blighted lands and other unnatural phenomena, and I can tie it all back to the Host, the terrible reverse-Ringwraiths that are my spooky-as-hell boss monsters.

Sorcery also allows me to add a note of horror into the story (which I always have to do) thanks to both the grotesqueness of the blight-touched and the contagious nature of their powers. A character like Jack Twist the Scavenger Prince isn’t just disturbing because he can manifest a nest of whips around his mutilated left fist, glowing and writhing with ichor-blight, but because even if you survive the touch of his whips you may end up blight-touched in the process. That horror of involuntary change will, I hope, speak to the YA audience as much as it speaks to my YA protagonist.

Alchemy

The mundane, subtle form of Eastern magic is alchemy – altering the properties of normal substances in order to create new effects. In its simplest, stablest form, alchemy simply creates stable and mundane substances with unusual uses, like curative poultices smoke-powder or the burn-salt the Easterlings used to make explosives. More unusual alchemical substances are harder to make but can have limited supernatural effects, like oils that briefly render metal transparent or drugs that send you into a clairvoyant trance. The most powerful of these substances cause permanent changes when taken or used, opening the body to receive sorcerous power – and so, of course, they are forbidden.

The mundane, subtle form of Eastern magic is alchemy – altering the properties of normal substances in order to create new effects. In its simplest, stablest form, alchemy simply creates stable and mundane substances with unusual uses, like curative poultices smoke-powder or the burn-salt the Easterlings used to make explosives. More unusual alchemical substances are harder to make but can have limited supernatural effects, like oils that briefly render metal transparent or drugs that send you into a clairvoyant trance. The most powerful of these substances cause permanent changes when taken or used, opening the body to receive sorcerous power – and so, of course, they are forbidden.

Story function: Smoke bombs, baby, smoke bombs all the way. You can’t have fantasy Batman without smoke bombs and grenades and knockout gas and all those other wonderful toys. Alchemical tricks are a good way to give non- or lower-powered characters an advantage when dealing with their enemies, allowing me to write scenes where a careful, smart hero overcomes a monstrous, blight-touched villain and have those feel believable.

Alchemy also lets me present a more socially-acceptable, less terrifying facet of Eastern magic, in turn giving me story options for portraying the role of Easterlings in Crosswater society. They can be doctors, engineers, apothecaries and sages, capable of small miracles – but because alchemy can be directed into the service of sorcery, they still aren’t liked or trusted. And that distrust propels the social tension and fear that springs up when the threat of sorcery returns to the city…

–

Huh. That was wordier than expected. These things are so simple and straightforward in my head; it’s only when trying to explain them that they become long and complicated.

Anyhoo, tune in next week for a discussion of Westron magic and its story functions, as well as a bit of compare-and-contrast between the two world of magic and some thoughts on where else I could take things.

As always, comments are greatly appreciated so that I know I’m not just mumbling into an empty room after all the punters have gone home HELLO HELLO IS THIS THING ON

January 6, 2013

Head down, bum up, build a world

I hate worldbuilding.

Well, okay, ‘hate’ is too strong a word. ‘Don’t enjoy or care about’ is probably more accurate. As I’ve mentioned before, my taste in fantasy runs less to Tolkien and more to Borges, who emphasised the ability to create ‘poetic faith’ in the reader rather than convince them that anything they were reading was or pretended to be ‘real’. Fiction is all about making things up, and I like to acknowledge that.

And that’s all well and good in theory, but I’m writing a fantasy novel right now, and worldbuilding isn’t optional. I get that – fantasy is based on things are not as you know, and any kind of consistent narrative has to position the reader in a space where the impossible, magical turns feel not just believable but justified. Events are supported by the setting, and the setting is in turn defined by events. Also, fantasy readers really, really care about worldbuilding, and I’d like them to buy read my book. So Raven’s Blood is making me confront my antipathy towards worldbuilding and work to overcome it, and that’s something I’d like to talk about – not just tonight, but for maybe the next half-dozen posts, assuming y’all don’t get bored.

To begin, let’s talk about what worldbuilding actually means and how you (and by you I mean me) go about it.

Look anywhere online and you’ll see that worldbuilding can be approached from two directions – top down and bottom up, both of which sound slightly homoerotic. (And there’s nothing wrong with that.) But in truth they’re less about manlove than about direction and priority.

If you’ve never heard of these two approaches, well, Wikipedia has a pretty good article on them and you should read that. But in summary, top-down means starting on the large macro scale – city, country, world, ENTIRE UNIVERSE OMG – and determining its parameters, then drilling down through the implications to detail things on an ever-smaller level until you reach the boundaries of your story. Going bottom-up means starting on the local level and filling in the details as you go, building upwards and adding on detail as the story or focus moves. Both approaches have value, and they have more in common than some people think – because let’s face it, in both cases you’re just making things up. On the whole, though, it seems like most fantasy authors like the top-down approach – to start with the world writ large and then pushing through to see the way that world shapes the story within.

I, of course, have to be different. I’m bottom up all the way AND STOP SNIGGERING UP THE BACK THERE.

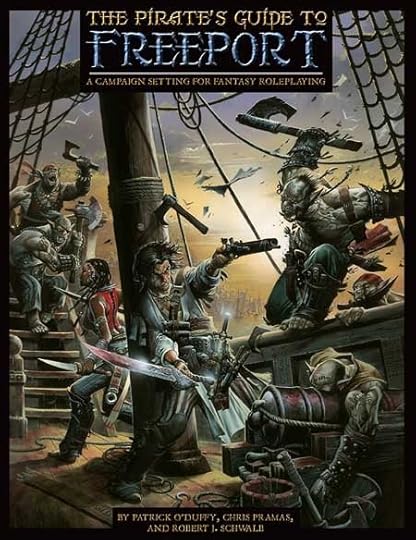

I’ve done top-down world design before, though – as part of my freelance RPG writing days. I’m thinking of the World of Darkness but even more of Freeport, which were created from day one to support a range of possible stories. Because that’s the way top-down approaches go – you make a world (or a country, or city etc) and then find or develop stories within that platform, and that’s what you need in an RPG setting, a platform and toolkit for making your own stories. In fact, I’d probably go so far as to say that commercial RPG worldbuilding has to be top-down – it’s what the market wants and it’s the only way to make a setting sourcebook broadly useful. On the other hand, I think most RPG campaigns tend to be bottom-up on some level, because in actual play you start fleshing out and exploring a core narrative thread and building new details around it.

–

Incidentally, I just want to mention that I’m totally goddamn stoked by the news today that Evil Hat and Green Ronin are teaming up for a Fate Core Companion for Freeport! Well, they will team up for one if the Fate Core Kickstarter reaches its next stretch goal, and I really hope it does. It’s a great, flexible game system, and I remain incredibly proud of the work I did on the Pirate’s Guide to Freeport, perhaps the single best bit of game writing I ever did.

Incidentally, I just want to mention that I’m totally goddamn stoked by the news today that Evil Hat and Green Ronin are teaming up for a Fate Core Companion for Freeport! Well, they will team up for one if the Fate Core Kickstarter reaches its next stretch goal, and I really hope it does. It’s a great, flexible game system, and I remain incredibly proud of the work I did on the Pirate’s Guide to Freeport, perhaps the single best bit of game writing I ever did.

So if either of those things appeal to you, you should put ten bucks into the Kickstarter. You’ll get a whole lot of gaming for bugger-all cash.

Now, back to the meandering.

–

From my POV, worldbuilding is always about invention. Sometimes it’s about exploring implications, sure, but it’s exploring the implications of things you decide to include in the first place. So top-down versus bottom-up is less about scale and scope and more about workload and direction. It’s about whether you make them up before or as you need them, and whether you start with the things that should be in there and then move to the things you want to be in there or vice versa. Neither is better than the other.

But I struggle with top-down creation, as both a writer and reader, because of the implication that the story presented at the end is a story that can be told in that world, not the story that must be told. I can’t shake that niggling lack of urgency that comes with knowing that the world is a bigger canvas than this one painting; the choice to focus on this particular narrative feels spurious on some level, and I find it harder to connect with what’s going on. I have the same problem sometimes with RPGs, although there it manifests as dithering and paralysis as I try to justify a specific choice of ideas to myself – why this, rather that that? And so I have to cut down the setting info I take in or acknowledge until I reach a point where the options are curtailed and a specific narrative thread seems not just logical but unavoidable.

Yeah. It’s weird. I know.

So in building the world of Raven’s Blood, I’m going bottoms-up all the way.

I started with what I knew I wanted – a story about a brave girl, a weary hero and a terrible threat. And I’ve let the story and the character dictate the world around – well, the city around them (Crosswater) to be exact, with the world behind that sketched in as lightly as I could get away with. I knew I wanted a story about the aftermath of conflict, so Crosswater still bears the scars of war. I knew I wanted an inhuman enemy and human faces for it, so that war was against the burning Host and their mortal servants – and that in turn led me to sketching a world with dawn-lands and dusk-lands and different societies and spirits in the East and West. I knew I wanted parkour and stunts and weird magic and superheroic action, and I knew I wanted everything to feed back and reinforce the themes I wanted to explore in the story.

And once I knew that, filling in the details was easy. Everything came from what I wanted to write about, rather than what I felt I should include for the sake of verisimilitude. And that may not make a world that feels ‘real’ enough for some readers, but hopefully it makes for a world that feels interesting.

And I for one prefer interesting to real. That’s the whole point of fiction.

–

The point of all this waffle, of course, is not to say ‘this is the right/best way to write’, because as always there are no best or right ways to write – there are just the ways that work. This works for me. So what works for you? C’mon, leave a comment and tell me you totally disagree with me. That would make me so happy.

(It really would.)

–

Next week, I’m heading further down the world-building path with the first of two posts about the magic of Crosswater and Raven’s Blood, as well as talking about the point of magic in fantasy stories. Yes, once again I’m defining a whole genre and telling other writers that they’re DOING IT WRONG. I hope you’ll join me.